ABSTRACT

In this study, we worked with both Turkish and U.S. samples to reveal how cultural influences might manifest themselves in the context of child-teacher relationships from children’s perspectives. There were 243 preschoolers and 26 classrooms included in the U.S. sample. In the Turkish sample, 211 preschool children from 41 classrooms participated. Data were obtained via interviews and analyzed based on thematic analysis method. Three main categories were identified as positive, negative, and neutral relationship perception. In the Turkish sample, the frequency of the negative relationship perception of children toward their teachers was found to be much higher than positive and neutral relationship perceptions. In the U.S. sample, the positive relationship perception of children was found to be higher than negative and neutral relationship perceptions. Neutral relationship perception was found to be more frequently expressed by children in the U.S. sample. This is one of the leading studies giving an opportunity to hear children’s voices about their relationship perceptions with their teachers, specifically with a cross-cultural viewpoint.

Social changes, changes in welfare level, and lifestyle influence social values, beliefs, traditions, and norms (Griph, Citation2015; Hortaçsu, Citation1997, Citation2003; Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2010). These changes in socio-economic and cultural dynamics seem to be reflected on family interaction patterns and childrearing attitudes and needs. Intercountry comparative studies conducted in different social strata by Kağıtçıbaşı (Citation2010) indicate how change in family systems leads to systematic changes in the values and expectations attributed to children. It is an inevitable result that these changes will cause differences in the education process as well (Bałachowicz et al., Citation2017; Griph, Citation2015). As a reflection of changes in the world, there is a dynamic process related to general attitudes and approaches in school settings and a reciprocal change influencing teacher-child, child-child, and teacher-parent interaction (Bałachowicz et al., Citation2017; Goodwin, Citation2017; Griph, Citation2015; Jorde, Citation1986; Lareau, Citation1987; Newman, Citation2000).

Mutual relationships are influenced by each individual within the relationship context, along with other systems they are attached to (see Hortaçsu, Citation2003; Pianta, Citation1999; Stevenson-Hinde, Citation1990). In that sense, the interactions between children and parents as well as the relationships between children and teachers are shaped by the infuences of those systems (Fredriksen & Rhodes, Citation2004; Myers & Pianta, Citation2008; Pianta, Citation1999). In regard to this, school and family contexts are parts of microsystems. Since children are raised dominantly within these under the influence of other overlapping sytems, such as culture, the link between those sytems should be functioning well, which is considered critical in supporting child development as a whole (see Griph, Citation2015).

It is known that interactions are reciprocal, and culture has a crucial part; culture shapes the child, and the child also contributes to culture and leads to social change (Löfdahl & Hägglund, Citation2012). Children have impact on school via many influences such as temperament, behaviors, or additional needs and teachers also can be one of the critical actors influencing this process (Griph, Citation2015). Besides this, school practices, teaching style, and beliefs on teaching and interactional patterns between teachers and children depend on cultural influences of the existing society, as culture has characterized how teaching can be done or how interactions can be managed under these cultural influences (Eberly et al., Citation2007). For instance, in individualistic cultures, like the main U.S. culture as we examined in the current study, autonomy is seen as the dominant aspect (Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2010); therefore, the experiences of individuals are considered as crucial factors in designing classroom activities. Teachers are usually expected to respect each child, with the idea in mind that each individual contributes to the whole community while representing her/his own identity as a separate entity (Hofstede, Citation2001, p. 235). On the other hand, in collectivistic cultures, as in the main Turkish culture, group influence and relationships are regarded as the most critical aspects of social life (Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2010). In societies with a collectivist nature, power usually has an important function among individuals, which might lead to distance in the formation of relationships and a structure in which the teacher becomes the center of communication rather than a reciprocal relationship (Hofstede, Citation2001, p. 235). Furthermore, when we consider the effect of technology, media, immigration, war, economy, and politics, we cannot ignore how the impact of global influences on the lives of children and families has been reflected in the school environment. Although there is a tendency to stregthen cultural roots in different societies, there also has been a transition to approach cultural diversity in a more welcoming manner as this is important for more harmonious society (Lefringhausen et al., Citation2021)

Because of the aformentioned factors, cultural diversity has become more evident in schools across different countries. Considering that the number of students from different racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds is increasing in many countries in Europe, and specifically in the United States, education in diverse classrooms emerges as a crucial need (Choi & Dobbs-Oates, Citation2015; Su, Citation2005). Although we cannot assume culture reflects overall practices within a particular society, a sufficient level of understanding about different cultures/subcultures and their practices might have considerable influences on creating a more acceptable school/classroom environment for children (Griph, Citation2015). It doesn’t have to be a full intercultural competency, but awareness of and knowledge about various cultures might be helpful for creating more flexible atmospheres for children with a view that they are all unique but might display similar developmental pathways across cultures (House et al., Citation2019).

It is clear that teachers need to be flexible enough regarding teaching and classroom practices and to be able to create culturally sensitive classroom environments in order to respond to the needs of children from culturally diverse backgrounds (Goodwin, Citation2017). At this point, effective communication between teachers and children would be crucial as they are most significant partners in the classroom environment. From the early years on, open, warm, and supportive relationships between children and teachers based on understanding and acceptance are extremely important in supporting multicultural learning environments (Thijs et al., Citation2012). As Hofstede (Citation2001) stated, the concept of multiculturalism is of particular importance not only for the development of the child, but also for the well-being of society as a whole. Therefore, intercultural comparative studies in the field of early childhood education regarding early relationships and the recognition of cultural practices are important for supporting the notion of multicultural teaching and classroom management. Moreover, these studies can strengthen intercultural ties and enable multidimensional cooperation (Hofstede, Citation2001; Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2010). From this point of view, the main focus of our work is to compare relationship perceptions of children with their teachers between Turkish and U.S. samples. It is going to be one of the rare studies in this field reflecting children’s voices via their own experiences. It is also expected that this work will contribute to better understanding of communication, which is a baseline for effective multicultural education and expanding healthier and more dynamic relationships in educational settings.

Cultural experiences, educational settings, and relationships in classroom context

As children’s relationship patterns with their caregivers are shaped via various experiences, they can reflect those patterns into any kind of relationships established in school environment (Pianta, Citation1999). In that sense, teachers play a crucial role in shaping children’s developmental pathways by means of positive relationships. They need to demonstrate a clear understanding of particular skills to form relationships with children (Lippard et al., Citation2017; Pianta, Citation1999). Within this process, educators may have various opportunities through supportive relationships to address potential harm caused by children’s negative past experiences. Since this is a bidirectional relationship, as previously discussed, teachers also express themselves within that communication through their own relationship patterns, past experiences, beliefs, existing emotional states, and professional competencies (Martin et al., Citation1999; Stormont et al., Citation2014; Sutton et al., Citation2009; Swartz & McElwain, Citation2012), while trying to create environments for promoting children’s social-emotional development, mental health, cognitive competence, and academic readiness (Ası et al., Citation2018; Palermo et al., Citation2007; Torres et al., Citation2015; Vandenbroucke et al., Citation2017). Besides professional training, teachers’ own culture-specific behavior repertoires are critical in shaping their values and beliefs regarding classroom management practices and relationship patterns (Bałachowicz et al., Citation2017; Öztürk & Gangal, Citation2016). Therefore, teachers should be able to understand children’s cultural backgrounds, as well as their own cultural interpretations, to implement more effective strategies by covering various cultural characteristics, habits, and practices in classrooms (Gay, Citation2002). Recognizing cultural diversity and supporting classroom engagement of children with diverse backgrounds would be an important asset for an early childhood educator (Allison & Rehm, Citation2006; Mevorach, Citation2008). With this idea in mind, cultural variations should be integrated into curriculum to achieve the best representation of every child (family) in the program, and communication with children from diverse cultural backgrounds should be established based on this understanding. A study in Sweden supporting this idea reveals that cultural diversity in preschool curriculum promotes positive social identity formation and provides an opportunity for children to recognize and understand other cultures better (Löfdahl & Hägglund, Citation2012). Therefore, it would be crucial for teachers to blend cultures of children with characteristics of his/her own culture and reflect this combination into the classroom environment, with the aim of improving sensitivity to children’s needs (Clarke & Drudy, Citation2006).

Behavior management and relationships in contemporary classes

In multicultural classrooms, teacher competence is particularly important in establishing effective teaching, behavior management, and positive student-teacher relationships (Wubbels et al., Citation2006). Rapid changes in both national and global areas, besides cultural influences, have led to an ongoing discussion about how well traditional disciplinary methods and management strategies function within classrooms (Arslan & Eraslan, Citation2003; Bałachowicz et al., Citation2017). Implementing supportive and proactive behavior management strategies (Dunlop et al., Citation2015; Emmer & Stough, Citation2001; Pianta, Citation1999; Tillery et al., Citation2010) would provide more opportunities to achieve harmonious communication in classrooms (Evertson et al., Citation2003; Howes et al., Citation2013). It is obvious that teachers can contribute to the development of positive relationships in supporting positive classroom climate, via sensitive, flexible, and caring approaches; it is thus possible to open a path to children’s emotional world and facilitate children’s involvement and engagement for further exploration (Westman & Bergmark, Citation2014).

A classroom management model, whether it is systemic, prosocial, student-centered, or eclectic, is significant in terms of supporting cultural diversity and enriching classroom practices (Emmer & Sabornie, Citation2014; Freiberg, Citation2006). Today, there is a need for classroom management approaches that allow secure, healthy relationship formation in responding needs of both teachers and children (Canter, Citation2010; Wubbels et al., Citation2006). For this reason, it is essential for teachers to improve themselves, both professionally and personally, in line with most recent developments related to classroom management and relationship skills, as well as reflective pedagogical competencies (see Freiberg, Citation2006).

Child-teacher relationships in early years

Children and teachers are the most important contributors in their own relationships; therefore, how they perceive communication influences their behavior patterns. The feedback provided for children through relationships can be a useful guidance for them, as this offers an invaluable perspective about the nature of the relationships in school context (Birch & Ladd, Citation1997). In order to consider children’s best interests, we need to undertand each party’s viewpoint to enable an effective communication pathway between children and teachers (Skivenes & Strandbu, Citation2006). Different sources should be consulted in order to be able to understand the nature of the aforementioned relations, to take preventive actions, and to contribute to the improvement of the quality. To sustain positive and effective relationships, it is also critical to see the quality of relationships through children’s eyes. When relevant literature is considered, it is clearly seen that the research has mainly focused on adults, such as teachers’ feedback on the relationships or observations of teacher behaviors within interactions (Akgün et al., Citation2011; Beyazkurk & Kesner, Citation2005; Martin et al., Citation1999; Merrett & Whelldall, Citation1993; Ritz et al., Citation2014; Uysal et al., Citation2010). The views of children would offer insightful evidence to understand dynamics of such relationships.

Cross-cultural studies considering interactions between children and teachers have received particular attention recently (Beyazkurk & Kesner, Citation2005; Verschueren & Koomen, Citation2012). There is a need to understand cultural variations in child care practices by conducting cross-cultural studies so that the findings can be integrated into teaching degree programs and alternative professional training programs across various countries (Beyazkurk & Kesner, Citation2005). Besides historical ethnic diversity in Turkey, there is also an increase in the number of refugees and immigrants from Syria and other nations; therefore, the classrooms have become more diverse than ever before (The United Nations Refugee Agency, Citation2015). Although there are some influential programs being implemented as a part of ongoing curriculum to support multicultural classrooms, children’s social, emotional, and mental well-being should be the most critical aspect of such practices (Sarmini et al., Citation2020). Through our research experience in different countries and many exchanges between our colleagues from different cultural contexts, we have been inspired to focus on children’s relationship perceptions. Although there is a clear agreement on why children’s voices should be included in research to support their participator role in decision-making processes (Darbyshire et al., Citation2005; O’Kane, Citation2008), still more research should include children’s voices in any idea related to their own lives. We believed that this study would provide some hints about how to manage effective classroom communication by comparing a Turkish sample with a collectivistic nature and a U.S. sample identified with more individualistic characteristics.

Purpose and hypotheses of research

We carried out a comparative study with the aim of revealing how cultural influences show themselves within the context of relationships in terms of children’s viewpoints. We believe that children’s participation is an important aspect of this study, as encouraging children’s participatory role in today’s society rather than only researching about them based on adult reports has merit (Darbyshire et al., Citation2005; O’Kane, Citation2008). We have specifically worked with preschool children because of the important contribution of a positive child-teacher relationship established from the early ages. We examine attitudes and approaches displayed by teachers from the children’s perspective by revealing how children perceive relationships with their teachers (positive and sensitive; punitive and negative; distant or neutral) in two different samples. More specifically, our goal was to reveal to what extent cultural aspects can be linked to teachers’ approaches in relationships from children’s perspectives. In this way, we aimed to compare and discuss the viewpoints of children in order to realize how cultural charactersictics might influence those relationships.

For this purpose, findings from samples of two cultures, from Turkey and the United States, have been compared. Although there are various subcultures in both samples that might influence characteristics of the main culture and have impact on children’s reports, we basically focused on children’s reports to see potential differences and/or similarities in their answers. We are aware that variations are evident within and between these two samples. On the other hand, it is known that relationships are more crucial to surviving within societal life compared to more autonomous societies. However, there may be some similarities due to global interactions. It is assumed that such comparison between children’s perceptions in two different cultures might provide an opportunity to discuss both similarities that may arise from global interactions as well as differences arising from cultural contexts. In this research, it was expected that teachers in the Turkish sample would be in a more close but demanding, oppressive, compulsive, and authoritarian position in the cycle of the relationship because of cultural expectations and socio-economical factors. Whereas it was thought that teachers in the U.S. sample would be more likely to adopt an approach encouraging children to act independently and self-sufficiently. In other words, it is assumed that teachers in the U.S. sample would be involved in a relationship motivating children to be more independent while managing their own worlds. The patterns of intimacy, conflict, and dependency that children perceive within the relationships they formed with their teachers were expected to differ between the two cultures. Within this framework, we tried to consider to what extent there would be similarities and differences in relationship perception of preschool children in Turkish and U.S. samples.

Method

Participants

In this study, we conducted qualitative research enriched by quantitative aspects in order to understand how children perceive their lived experiences with their teachers (Merriam, Citation2002). We focused on the meaning of child-teacher relationships in terms of young children’s viewpoint. Therefore, we obtained the data based on children’s descriptions. We used convenient sampling method to access participants easily and compared perceptions of preschool children in Turkish and U.S. samples. In both countries, random assignment of schools was not possible, as we were limited to schools where the legal permissions were released. All ethical issues have been considered, including all permissions and institutional review board (IRB) in the United States and ethical committee review at the university in Turkey. Children were recruited based on consent forms approved by their parents. After we obtained parental consent, we asked children for their verbal consent to answer the questions we would ask. The preschools in the United States were located in the cities of State College and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Those schools were either half day or whole day depending on their status, like charter preschools, church schools, child care center in the university, and private schools. We asked 18 schools at the initial phase; half of them (9 schools) agreed to participate. After gaining agreement from principals and teachers for their participation, parent consent forms were sent to all families whose children were attending those 26 classrooms. We sent 384 consent forms to parents and eventually worked with 243 preschoolers (5 and 6 years old), because some parents did not give consent, some children did not speak English as their primary language, and/or some had speech problems.

The preschools in Turkey were located in Izmir, which is the third biggest city of Turkey on the west coast. We chose to work with four preschools (university and public preschools) since directors and teachers in those schools showed willigness to participate in the study and they were also easily accessible. In those schools, national curriculum appointed by Ministry of Education has been implemented and they offer half- and full-day programs for children. Furthermore, socio-economic status of the families was assumed to be similar in those preschools, which were situated in the central districts of Izmir. In the Turkish sample, 211 preschool children (5 and 6 years old) without any developmental delays and/or disabilities participated in the study.

Turkish preschools are usually more homogenous compared to preschools in United States, and that was the case in our study. The data, in both samples, were collected from children attending various classrooms. There are usually two teachers in U.S. preschool classrooms; on the other hand, there is usually one teacher in each Turkish preschool classroom. We don’t have clear data about the cultural, ethnic backgrounds of teachers, which might be a factor to consider while interpreting the results. On the other hand, our main focus was children’s perspectives. When the number of children was considered in each sample, we believed that the data would provide valuable information regarding our aim.

Instrument

The Semi-Structured Play Interview (SSPI; Pianta & Hamre, Citation2001) is a form consisting of eight story stems that are formed based on semi-structured interview technique. Each story stem is read to the child and the child is expected to complete the rest of the story. For example, the interviewer says, “One of the children in the class doesn’t follow teacher’s advice, even if the teacher wants them to be silent.” The interviewer then asks the child, “I wonder what happens next?” At this point, the aim is to reveal how the child perceives the relationship he/she established with the teacher. The interviewer also assesses whether the child has taken the teacher’s point of view via questions such as, “In that case, how would the teacher feel or think?” At points where children have difficulty in answering the questions, the interviewer encourages the child to respond and uses probing to get more detailed information if necessary.

During the SSPI, the interviewer takes notes about what the child says, and any other sounds and gestures made during the whole interview. The predictive validity of the SSPI developed by Pianta and Hamre (Citation2001) with a U.S. sample was tested with the Turkish sample by using a relationship-based intervention program, Banking Time (Beyazkurk, Citation2005). In the Turkish study, the average total score of SSPI in the control group was found to be significantly different from children in the intervention group, which means that those two groups perceived their relationships differently. This finding suggested that SSPI distinguishes between intervention and control groups, which provides valid evidence for the instrument’s predictive validity (Ası, Citation2019; Beyazkurk, Citation2005). The Turkish adaptation of the instrument was also processed to neutralize potential cultural and contextual influences. To achieve this, all items were validated based on the feedback of professionals in the field and language specialists who are competent in both languages. As a result of this process, some items were revised to meet the contextual and cultural requirements of Turkish preschool settings (Sahin & Anliak, Citation2008).

Procedure

For this study, we worked with children whose parents gave consent for their participation in the study. After consent forms were received via classroom teachers, we conducted interviews with children individually by using the SSPI to reveal children’s mental representations of their relationships with teachers (Pianta, Citation1999). Each interview took approximately 20–25 minutes. Interviewers were introduced to the children via classroom teachers. The children were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and their right to leave anytime they wanted. Interviews were conducted in a seperate room at school for most of the cases; sometimes, however, we had to interview children in a quiet place in the classroom because a separate room was not available.

Analysis

As a data analysis method, we used a qualitative approach to interpret the findings in a more proper and understandable way. Therefore, we used thematic analysis to extract themes and subthemes, and to create main categories covering those themes. Besides thematic analysis, we supported our presentation via frequencies to demonstrate a clearer picture about how frequently themes and subthemes were repeated by children. In that sense, our qualitative approach has been enriched via quantitative aspects of the dataset.

In our study, each semi-structured play interview protocol was transcribed into a detailed verbatim document so that thematic analysis of the data set could be performed. To enable the analysis, the children’s answers were reviewed to identify relevant categories to be coded. First of all, we prepared answer lists for each question. Based on those lists, we decided on the themes and checked against potential overlaps between different themes. In the final phase, we agreed on three basic categories – negative, positive, and neutral – to be associated with the identified themes and sub-themes.

Each protocol was carefully examined in detail by the researchers and experts in early childhood education field. The U.S. data were examined by two Turkish researchers (preschool education specialists, one who completed her doctorate in clinical psychology and the other who completed her doctorate in developmental psychology) and two U.S. researchers (a research coordinator and a doctoral student in the department of Human Development and Family Studies). The Turkish data were examined by four Turkish researchers (one who completed her doctorate in the field of clinical psychology, another who completed her doctorate in developmental psychology, a preschool education specialist, and an education specialist). In this process, experts from two cultures have made it possible to evaluate both cultures in a way that considered cultural and contextual characteristics. For example, the U.S. preschool education system emphasizes that children should try to solve conflicts on their own before they ask for help. If he/she cannot find a solution to the conflict, then he/she is supposed to ask for help from his/her peers. The teacher should be the last alternative to get help. On the contrary, in Turkey, seeking help from teacher comes first when dealing with conflicts. The importance of cooperation in social life is interpreted as the same by the coders for both Turkish and U.S. samples. However, how cooperation is assessed may differ in relation to when, how, and why it is displayed. According to the individualistic viewpoint, trying to help a group while working on a task might be interpreted as an intervention in that person’s rights. Whereas in the collectivistic approach, the same situation is perceived as a step for establishing or strengthening interpersonal relationships. Therefore, including the different perspectives of coders allowed us to represent various viewpoints, which provided an extensive experience regarding children’s answers while trying to synthesize contextual information. The way we interpreted the data and negotiation across the transcribed documents has been used to support best representation of the data. We believe that this has provided an insightful contribution to our reflexive practice of research as well (Berger, Citation2013). Thus, in this study, the inclusion of coders from both cultures for the thematic analysis supported the validity of data we analyzed. With this idea in mind, we also calculated inter-coder reliability and reached 86% agreement between the coders.

Findings

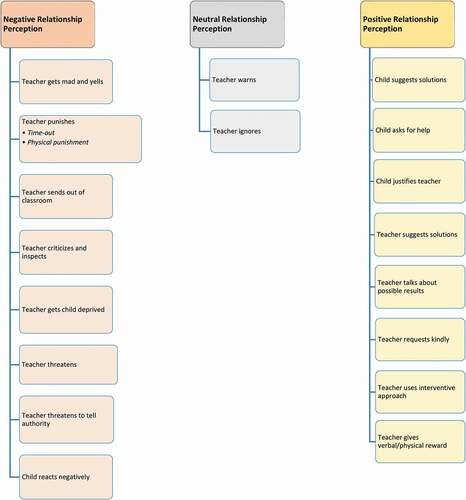

In this section, the themes and sub-themes summarized under three categories concerning children’s relationship perceptions are presented in a comparative manner. Based on the responses of children to eight story stems, we have identified three basic categories: negative relationship perception, neutral relationship perception, and positive relationship perception. Themes and subthemes are presented, including quotes based on children’s reports. To support themes (and subthemes), we also reported frequencies for each to demonstrate how frequently the ideas representing the themes and sub-themes were repeated by children. All categories, themes, and sub-themes are summarized in .

Basic categories: Positive, negative, and neutral relationship perception

Turkish preschoolers described their relationships with teachers negatively more often (f = 1,755) compared to positive (f = 763) and neutral (f = 127) relationship perceptions. In the U.S. sample, although children’s positive and negative relationship perceptions were expressed as close to each other, positive relationship perception (f = 532) was more frequently expressed by children (see ). We will present details within the following sections, as themes and subthemes are the main components of data we have collated and analyzed.

Table 1. Basic categories of relationship perception in Turkish and U.S. samples

Category 1: Negative relationship perception

The themes falling under negative relationship perception category are presented in . The theme “Teacher gets mad/yells” has the highest frequency in both groups (Turkish and U.S.). However, there is a difference in how much it was repeated between two samples; it was repeated 265 times in the U.S. sample and 931 times in the Turkish sample. The other themes most frequently repeated in the Turkish sample were “Teacher punishes” (f = 234) and “Teacher sends out of classroom” (f = 147). However, in the U.S. sample, the theme “Teacher sends out of classroom” was not repeated much (f = 19); no direct statements were identified containing punishment either. We described two sub-themes under the “Teacher punishes” theme. The first one was time-out, such as “The child turns his/her back, sits by himself/herself; The child will sit in such a place not to allow him seeing his/her friends.” The second one was related to physical punishment, which was expressed in children’s answers like “If the child still continues, the teacher beats and hurts him/her.” When we look at the frequencies, time-out was repeated 94 times by Turkish preschoolers and 74 times by U.S. preschoolers. The only punishment perception expressed by children in the U.S. sample was related to the subtheme we called “the time-out.” Apart from this, statements containing punishment description were not used by U.S. prechoolers, as can be observed in . The subtheme of physical punishment was only used by Turkish preschoolers and the statements related to this subtheme were repeated 34 times. In both samples, “Teacher threatens to tell authority” was found as the least repeated theme. The theme “Child reacts negatively” appeared only in the Turkish sample with statements such as “The child gets sad, angry, gets angry with the teacher; The child beats the teacher; Child will hit teacher” and was repeated 26 times by children.

Table 2. Themes related to negative relationship perception

Category 2: Neutral relationship perception

Under this category, we have identified two themes: “Teacher warns” and “Teacher ignores.” Regarding the theme “Teacher warns,” children expressed their ideas in the following way: “Teacher warns him/her; Teacher tells him/her to be quiet.” For the theme called “Teacher ignores,” children reported that “Teacher carries out the activity without noticing the child; Nothing, the child will continue on the task.” The frequencies regarding these themes have been included in . When both countries were evaluated in terms of the “Teacher warns” theme, it was seen that children in the U.S. sample (f = 253) repeated this theme more frequently than the children in the Turkish sample (98). The theme “Teacher ignores” was repeated 29 times in the Turkish sample and 6 times in the U.S. sample.

Table 3. Themes related to neutral relationship perception

Category 3: Positive relationship perception

Eight themes were identified under the positive relationship perception category (see ). The first one is “Child suggests solutions,” which was expressed like “I would say I have a book, a book with a princess. I would bring it and my teacher won’t say anything to that.” The second theme is called “Child asks for help” and identified with the ideas like “I’ll tell my teacher; My teacher helps; My teacher repairs the toy.” The third theme was “Child justifies teacher,” including ideas such as “Because the child doesn’t keep quiet; Teacher feels bad because child doesn’t listen; Child should obey (the rules).” The other theme, called “Teacher suggests solutions,” was identified by ideas as follows: “I’ll ask for help from the teacher; Teacher will help a little; Teacher will say, ‘You can do something else if you like.’ ” In another theme, “Teacher talks about possible results,” the ideas expressed are: “Teacher says, ‘Come on, eat faster, we already have started; your friends ate really fast so they’re ready for the lesson, but you aren’t, because you are eating very slowly.’ ” Under the theme “Teacher requests kindly,” children explained such ideas as “Teacher says, ‘Help yourself please,’ and child replies, ‘OK teacher.’ ” The theme called “Teacher uses interventive approach” indicated ideas like “Child asks the teacher, ‘Why am I staying inside?’ and the teacher says, ‘Because there is ADSD program (intervention), that’s why you’re going to stay inside’; When the teacher comes back to class, he/she talks to the child and asks, ‘Do you know why I did not let you out?’ and the child replies, ‘Because I was naughty, but I won’t misbehave again’ and the teacher doesn’t get mad at him/her anymore and allows child to play.” The last theme under this category was “Teacher gives verbal/physical reward,” in which children expressed such ideas: “When the child behaves well, the teacher will say, ‘Well done,’ and kisses the child.”

Table 4. Themes related to positive relationship perception category

When is examined, in the Turkish sample, the frequencies of “Child suggests solutions” (f = 243), “Child asks for help” (f = 173), “Child justifies teacher” (f = 152), “Teacher suggests solutions” (f = 104), and “Teacher talks about possible results” (f = 45) themes were found to be higher than the U.S. sample. Whereas in the U.S. sample, the repetition frequency of “Teacher requests kindly” (f = 97), “Teacher uses interventive approach” (f = 66), and “Teacher gives verbal/physical reward” (f = 22) themes appeared to be higher than that of the Turkish sample.

Discussion

In our study, we obtained some interesting results besides similarities and differences parallel to our predictions. When the children’s relationship perceptions about their teachers were evaluated in both samples, the highest frequency was found to be in the negative relationship category for Turkish sample, whereas the positive relationship category included highly repeated answers for the U.S. sample. Although the negative relationship perception was higher in the Turkish sample, the frequency of expressions related to positive relationship perception was also high, at a level that cannot be underestimated. The category with the lowest frequency between the two samples was the perception of neutral relationship. We have seen that children in the U.S. sample used themes that indicate a higher rate of neutral perception than children in the Turkish sample.

As we have observed the most interesting results in negative relationship perception category, it would be better to focus on this issue first. When we look at the most repeated themes regarding negative relationship perception, “Teacher gets mad/yells” appeared as the top theme in both samples. The theme “Teacher punishes” was ranked second, but only in the Turkish sample. This is a finding that needs to be addressed and discussed further. Considering the Turkish sample, it is thought that any approach of the teacher the restricts or hurts children via “getting mad/yelling,” “punishing,” sending to “time-out,” and even “imposing physical punishment” may cause children to react against the teacher. Even if “time-out” can be used as a behavior management strategy, adults should be careful as there are some cases, as shown by our findings, when it might turn out to be a part of negative behavior management style (Dadds & Tully, Citation2019). As mentioned earlier, relationships are mutually reflected, and the negative relationship cycle can lead to dissatisfaction in the relationship, and this pattern can persist over and over again, potentially worsening over time (Allen, Citation2010; Mayer, Citation2000). Furthermore, the actions of individual members of the class (children, teachers, assistant teachers, etc.) can influence everyone’s behavior in the surrounding environment, which might affect the classroom climate (Allen, Citation2010).

In Turkey, specifically, studies conducted about classroom and behavior management have reported similar findings as what we obtained for the negative relationship perception category (Sadık, Citation2008; Uğurlu et al., Citation2014). Those studies revealed that teachers often have adopted a reactive management model, such as verbal warning, yelling, punishment, and ignorance, when encountering a misbehavior displayed by children. It was reported that teachers try to stop misbehavior via strategies that include either immediate reactions or strict approaches, such as punishment, rather than using preventive strategies before that behavior appears. In another study, with a Turkish sample, evaluating both teachers’ and children’s perspectives about classroom rules and how well those rules function in the classroom, authors reported differences between the perceptions of teachers and children (Karabay & Ası, Citation2015). According to those results, teachers’ reports showed that they would have positive attitudes toward children only if the rules are followed by them. In the same study, children’s perspectives have been considered as well. According to preschoolers, teachers might get mad very often and/or sometimes prefer punishment if the child misbehaves. Teachers could say “shut up!” or they may “send the child who is misbehaving to another class” or take the “child out of classroom.” The divergence between the reports of children (or classroom observations) and teachers can be found in other studies (Ası, Citation2019; Oztemir & Ası, Citation2019; White, Citation2016). On the other hand, in one of the recent studies conducted with a Greek sample (Gregoriadis et al., Citation2020), similarities (small to moderate convergence) were found between the perceptions of children and teachers regarding their reciprocal relationships. Rearding this point, more research on this issue might be helpful to understand particular dynamics influencing interpretations of children and teachers.

Although the approaches that teachers use, such as punishing, warning, threatening, and pushing for certain behaviors, would harm child-teacher interactions, it is understood that such approaches are widely used as part of a traditional attitude. However, we know that those attitudes are more likely to produce some short-term effects and do not contribute to the development of adaptive behavior (Akgün et al., Citation2011; Uysal et al., Citation2010). At this point, it would be better to address some potential influences that might lead to those kinds of approaches. For instance, schools might not have proper infrastructure and resources to be used; smaller classrooms, shortage of resources, or class size can have an impact while communicating with children. Specifically, in the Turkish cultural contexts, people tend to speak loudly; therefore, this attitude is reflected in children’s communication, which, in turn, can create pressure on teachers while trying to manage a group of preschoolers. When teachers speak loudly to children, the children might misinterpret those signals and it can turn out to be a negativity associated with teacher’s behavior. It is obvious that getting mad/yelling and punishing would hinder internalization of participatory, supportive, and interactive teacher-child relationships. According to Cartleoge and Kourea (Citation2008), the extreme use of punishment has potentially devastating role on children, leaving a very strong influence on them psychologically. However, using supportive approaches, including multidimensional preventive intervention programs, helps to increase children’s positive school experiences (Gregory et al., Citation2010). Considering our findings in the current study, children’s negative reflections could be shifted when positive, calm, and harmonious interaction styles become a part of typical relationship patterns within classroom environment.

Cultural variables, such as child rearing practices where teachers grow up, may lead to attitudinal differences regarding relationships formed with children (Neal et al., Citation2001). A teacher who was raised within a cultural approach that prioritizes control, obedience, and dependence rather than autonomy in child rearing, can display a strict reaction to children’s behaviors because of the effect of his/her cultural dispositions. Correspondingly, children might have similar perception regarding the role of adults in their lives as a reflection of their cultural background. In a study conducted in the United States (Wright et al., Citation2017), researchers found that similarities in cultural practices and expectations (including both children and teachers) would help to reduce externalizing behavior problems of children within communication. On the other hand, given their responsible adult role, teacher’s positive, encouraging, and supportive relationship style as well as proactive behavior management strategies would contribute more to strengthen child-teacher and child-child relationships (Emmer & Stough, Citation2001; Greenberg et al., Citation2018; Güzeldere Aydın & Ocak Karabay, Citation2020). Research has also focused on how student-centered learning practices reduce misbehaviors and promote supportive, respectful relationships, compared to teacher-dominated classroom environments (Freiberg, Citation2006; Garrett, Citation2008). Teachers enhancing the quality of relationships with a tolerant, loving, sensitive approach to support positive school climate can enter into children’s emotional world and increase children’s participation (Westman & Bergmark, Citation2014). Additionally, as positive reflections of child-teacher relationships become apparent in children’s behaviors, this will also lead to improvements in the behavioral cycle of the wider classroom climate (O’Connor et al., Citation2011). Otherwise, negative relationship patterns in those relationships might lead to escalation of mutual frustration and aggression, which might harm the professional relationship (Allen, Citation2010). Essentially, in the current study, the statements children use, such as “The child gets sad and angry with the teacher,” in Turkish sample, can be considered as an important reflection of the negative relationship perception of children.

All themes of neutral relationship perception were expressed by both samples. When the frequency values were examined, it was seen that “Teacher warns” as a theme was repeated more frequently (25%) in the U.S. sample. In other words, in the U.S. sample, teachers were more likely to use verbal communication with children, more specifically “warning.” Ritz et al. (Citation2014) reported that the most typical and most widely used teacher approaches involving less intervention are warning, offering choices, guidance for adaptative behavior, and using indirect praise. When verbal warnings are used correctly and appropriately, they can turn into an effective approach. It is claimed that these attitudes allow children to manage their own behaviors, thus contributing to children’s self-regulation skills.

When the contents of the themes under the positive relationship perception category and frequencies were evaluated, “Child suggests solutions,” “Child asks for help,” “Child justifies teacher,” “Teacher suggests solutions,” and “Teacher talks about possible results” were found to be more frequently repeated themes in the Turkish sample. In the U.S. sample, “Child asks for help,” “Teacher requests kindly,” “Child suggests solutions,” and “Teacher suggests solutions” were among the most reported themes by the preschool children. In both samples, the frequencies of the themes emerging under the positive relationship perception category draw a similar picture. This finding indicates that, specifically in the preschool period, teachers are seen as significant resources in establishing positive relationships with children; therefore, they play a role beyond teaching task (Howes & Hamilton, Citation1992; Lippard et al., Citation2017). According to Birch and Ladd (Citation1997), the underlying reason for children’s need to be close to and dependent on the teacher might result from their need for reliable guidance to overcome potential difficulties associated with communication with other adults or peers during this period. In the school setting, teachers can play an important role as a safe haven to help children meet their social communication needs, which can be difficult to manage at times. Therefore, the teacher can become a critical person who comforts the child, just like a parent might do. Kurki et al. (Citation2017) reported that when teachers were involved in the communication, children were found to be more adaptive and more likely to regulate their behaviors. Therfeore, in our research, the frequent repetition of the “Child asks for help” theme in both cultures can be interpreted as a positive feedback in terms of the teacher’s function in a child’s life.

While in some cultures, the importance of self-discipline and autonomy are both supported characteristics, in another culture this perspective may not be appreciated; instead, adult-initiated disciplinary measures can be prominent factors in terms of child-rearing practices. Thus, these variances in cultural attributions can lead to differences in the interpretation of the same behavior. For instance, it is quite usual to observe that a parenting behavior labeled as intrusive in a particular cultural context (mostly in individualistic cultures) can be regarded as sensitive parenting attitude in another culture, as it combines control with love (Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2010). It is also possible to see some evolving attitudes in child rearing practices across time and subcultures within the main culture. In an earlier study (cited in Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2007), it was reported that religious aspects can be linked to authoritarian parenting styles in Turkey; however, she also found no difference between Turkish and U.S. adolescents in terms of perceived parental warmth despite Turkish adolescents reporting more parental control (1970, as cited in Kağıtçıbaşı, Citation2005). In a later study, regarding the value of the child in Turkey, the self was found to be associated with autonomy in high SES urban groups more than rural groups (Kağıtçıbaşı & Ataca, Citation2005). This also has been interpreted as a reflection of an urban and modern pattern of the family model in Turkish society.

In general, the fact that children in the Turkish sample consider their teachers as both angry and threathening while at the same time making positive references to their relationships established with teachers reveals an existing structure within the Turkish culture (Oztemir & Ası, Citation2019). Children’s two-sided perspective provides a general view of the relationship cycle that involves trust and conflict simultaneously. This is important because it also can reflect children’s perceptions of whether they are emotionally safe or not. At this point, it is crucial to understand how relational needs and relationship patterns function may vary according to social codes and cultural variables in different countries. Researchers suggest that in these cases teachers might benefit from professional development programs where they would be asked to confront their own cultural biases about “good” child-rearing practices (Eberly et al., Citation2007).

In this study, children’s relationship perceptions helped us capture a general viewpoint regarding the classroom atmosphere as well as classroom management strategies that teachers use in both cultures. However, in comparing the findings obtained from both samples, it is necessary to consider the differences of two countries related to context and to take into account unique cultural characteristics. There are many studies in which teachers’ approaches and expectations concerning children with different cultural backgrounds (McKown & Weistein, Citation2008), yet more studies are needed, especially those that reflect children’s viewpoints. Additionally, making a comparison between the relationship perceptions of children and teachers between two samples also might add great value for our research.

In order for children to be supported effectively in the classroom environment and for the positive classroom atmosphere to be promoted, prejudices must be overcome and cultural elements should be recognized clearly. Teacher support is one the most crucial ones; when the perceived teacher support is high, children might perceive less prejudice than when they feel they are not supported well by their teachers (Miklikowska et al., Citation2019). However, in one of the recent comparative studies, teachers reported that cultural diversity is a difficult concept that needs further clarification and teaching in a multicultural classroom and they need additional skills (Herzog-Punzenberger et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it was suggested that a school policy on diversity might help teachers to better adapt culturally responsive practices in the classroom. As creating a culturally responsive practice can be supported via experiences and perspectives of children as well as their families (Gay, Citation2002), parents/carers would be important contributors for creating such a classroom/school environment. We believe that our work will provide a perspective and contribution in that sense. On the other hand, while interpreting the findings of the current study, it should be noticed that it was a small-scale investigation and the results cannot be generalized overall. For this reason, large-scale research designs and comparisons, including multiple countries, are necesseary to reach more generalizable and comprehensive outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akgün, E., Yarar, M., & Dinçer, Ç. (2011). Okul öncesi öğretmenlerin sınıf içi etkinliklerde kullandıkları sınıf yönetimi stratejilerinin incelenmesi. Pegem Egitim ve Ögretim Dergisi, 1(3), 1–9. https://pegem.net/dosyalar/dokuman/125894-20111014105346-akgun-yarar.pdf https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14527/C1S3M1

- Allen, K. P. (2010). Classroom management, bullying, and teacher practices. The Professional Education, 34(1), 1–11. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ988197.pdf

- Allison, B. N., & Rehm, M. L. (2006). Meeting the needs of culturally diverse learners in family and consumer sciences middle school classrooms. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 24(1), 50–63. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/meeting-the-needs-of-culturally-diverse-learners-in-Allison-Rehm/23f48cec81c0463553bc32fb033ede9c1adad584

- Arslan, M. M., & Eraslan, L. (2003). Yeni eğitim paradigması ve Türk eğitim sisteminde dönüşüm gerekliliği. Milli Egitim Dergisi, 160. http://dhgm.meb.gov.tr/yayimlar/dergiler/Milli_Egitim_Dergisi/160/arslan-eraslan.htm

- Ası, D. Ş. (2019). How banking time intervention works in Turkish preschool classrooms for enhancing student-teacher relationships. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 13(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-019-0059-4

- Ası, D. Ş., Aydın, D. G., & Karabay, O. Ş. (2018). How preschool teachers handle problem situations: Discussing some indicators of emotional issues. Journal of the European Teacher Education Network, 13, 126135. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1C9h2hki2Y3OMOwPqAt64G6cTLpxzortj/view

- Bałachowicz, J., Nowak-Fabrykowski, K., & Zbróg, Z. (2017). International trends in preparation of early childhood teachers in a changing world. Wydawnictwo Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalnej Warszawa. http://www.aps.edu.pl/media/883482/international_trends_e-book.pdf

- Berger, R. (2013). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Beyazkurk, D. (2005). Biriktirilmiş olumlu deneyimler (banking time) müdahale programının okulöncesi öğrenci-öğretmen ilişkileri üzerindeki etkisi [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Ege Üniversitesi.

- Beyazkurk, D., & Kesner, J. E. (2005). Teacher-child relationships in Turkish and United States schools: A cross-cultural study. International Education Journal, 6(5), 547–554. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ855008.pdf

- Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). The teacher-child reletionship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 61–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-4405(96)00029-5

- Canter, L. (2010). Lee Canter’s assertive discipline: Positive behavior management for today’s classroom (4th ed.). Solution Tree Press. https://books.google.lu/books/about/Lee_Canter_s_Assertive_Discipline.html?id=gWi8QAAACAAJ&redir_esc=y#:~:text=Assertive%20Discipline%C2%AE%3A%20Positive%20Behavior,students%20will%20receive%20consistently%20for

- Cartleoge, G., & Kourea, L. (2008). Culturally responsive classrooms for culturally diverse students with and at risk for disabilities. Exceptional Children, 74(3), 351–371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290807400305

- Choi, J. Y., & Dobbs-Oates, J. (2015). Teacher-child relationships: Contribution of teacher and child characteristics. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2015.1105331

- Clarke, M., & Drudy, S. (2006). Teaching for diversity, social justice and global awareness. European Journal of Teacher Education, 29(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760600795239

- Dadds, M. R., & Tully, L. A. (2019). What is it to discipline a child: What should it be? A reanalysis of time-out from the perspective of child mental health, attachment, and trauma. American Psychologist, 74(7), 794–808. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000449

- Darbyshire, P., MacDougall, C., & Schiller, W. (2005). Multiple methods in qualitative research with children: More insight or just more? Qualitative Research, 5(4), 417–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794105056921

- Dunlop, G., Lee, J. K., Joseph, J. D., & Strain, P. (2015). A model for increasing the fidelity and effectiveness of interventions for challenging behaviors. Infants and Young Children, 28(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/iyc.0000000000000027

- Eberly, J. L., Joshi, A., & Konzal, J. (2007). Communicating with families across cultures: An investigation of teacher perceptions and practices. The School Community Journal, 17(2), 7–27. https://www.adi.org/journal/fw07/eberlyjoshikonzalfall2007.pdf

- Emmer, E. T., & Sabornie, E. J. (2014). Introduction to the second edition. In E. T. Emmer & E. J. Sabornie Eds., Handbook of classroom management (2nd ed., pp. 3–8). Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203074114

- Emmer, E. T., & Stough, L. M. (2001). Classroom management: A critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. Educational Psychologist, 36(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3602_5

- Evertson, C. M., Emmer, E. T., & Worsham, M. E. (2003). Classroom management for elementary teachers (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Fredriksen, K., & Rhodes, J. (2004). The role of teacher-student relationships in the lives of students. New Directions for Youth Development, 103(103), 45–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.90

- Freiberg, H. J. (2006). Classroom management and student achievement. In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management (pp. 228–230). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Garrett, T. (2008). Student-centered and teacher-centered classroom management: A case study of three elementary teachers. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 43(1), 34–47. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ829018

- Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053002003

- Goodwin, A. L. (2017). Who is in the classroom now? Teacher preparation and the education of immigrant children. Educational Studies, 53(5), 433–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2016.1261028

- Greenberg, M., Domitrovich, C., Ocak Karabay, S., Tuncdemir, A., & Gest, S. (2018). Focusing on teacher-children relationship perception and children’s social emotional behaviors - the PATHS Preschool Program. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 3(1), 8–20. https://www.ijere.com/article/focusing-on-teacher-children-relationship-perception-and-childrens-social-emotional-behaviors-the-paths-preschool-program

- Gregoriadis, A., Grammatikopoulos, V., Tsigilis, N., & Verschueren, K. (2020). Teachers’ and children’s perceptions about their relationships: Examining the construct of dependency in the Greek sociocultural context. Attachment & Human Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1751990

- Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09357621

- Griph, V. (2015). The role of cultural background in a parentteacher relationship: The case of Russian immigrant parents and Swedish elementary school teachers [ Master of Science Thesis]. University of Gothenburg. (Publication No. 2015:049). https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/40678/1/gupea_2077_40678_1.pdf

- Güzeldere Aydın, D., & Ocak Karabay, Ş. (2020). Improvement of classroom management skills of teachers leads to creating positive classroom climate. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 5(1), 10–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24331/ijere.646832

- Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Altrichter, H., Brown, M., Burns, D., Nortvedt, G. A., Skedsmo, G., Wiese, E., Nayir, F., Fellner, M., McNamara, G., & O’Hara, J. (2020). Teachers responding to cultural diversity: Case studies on assessment practices, challenges and experiences in secondary schools in Austria, Ireland, Norway and Turkey. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32(3), 395–424. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09330-y

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hortaçsu, N. (1997). İnsan ilişkileri (2nd ed.). Imge.

- Hortaçsu, N. (2003). Çocuklukta ilişkiler, ana baba, kardeş ve arkadaşlar. İmge.

- House, B. R., Kanngiesser, P., Barrett, H. C., Broesch, T., Cebioglu, S., Crittenden, A. N., Erut, A., Lew-Levy, S., Sebastian-Enesco, C., Smith, A. M., Yilmaz, S., & Silk, J. B. (2019). Universal norm psychology leads to societal diversity in prosocial behaviour and development. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 36–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0734-z

- Howes, C., Fuligni, A. S., Hong, S. S., Huang, Y. D., & Cinisomo, S. L. (2013). The preschool instructional context and child-teacher relationships. Early Education and Development, 24(3), 273–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2011.649664

- Howes, C., & Hamilton, C. E. (1992). Children’s relationships with caregivers: Mothers and child care teachers. Child Development, 63(4), 859–866. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01666.x

- Jorde, P. (1986). Early childhood education: Issues and trends. The Educational Forum, 50(2), 171–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131728609335749

- Kağıtçıbaşı, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275959

- Kağıtçıbaşı, C. (2007). Family, self and human development across cultures: Theory and applications. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315205281

- Kağıtçıbaşı, C. (2010). Benlik, aile ve insan gelişimi: Kültürel psikolojide kuram ve uygulamalar. Koç Universitesi.

- Kağıtçıbaşı, C., & Ataca, B. (2005). Value of children and family change: A three-decade portrait of from Turkey. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54(3), 137–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00213.x

- Karabay, S. O., & Ası, D. Ş. (2015). Classroom rules used by preschool teachers and children’s levels of awareness relating to rules. Inönü Üniversitesi Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 16(3), 69–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17679/iuefd.16331426

- Kurki, K., Järvenoja, H., Järvelä, S., & Mykkänen, A. (2017). Young children’s use of emotion and behaviour regulation strategies in socio-emotionally challenging day-care situations. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 41, 50–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.06.002

- Lareau, A. (1987). Social class differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital. Sociology of Education, 60(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2112583

- Lefringhausen, K., Ferenczi, N., Marshall, T. C., & Kunst, J. R. (2021). A new route towards more harmonious intergroup relationships in England? Majority members’ proximal-acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 82, 56–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.03.006

- Lippard, C. N., La Paro, K. M., Rouse, H. L., & Crosby, D. A. (2017). A closer look at teacher-child relationships and classroom emotional context in preschool. Child & Youth Care Forum, 47(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-017-9414-1

- Löfdahl, A., & Hägglund, S. (2012). Diversity in preschool: Defusing and maintaining differences. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 37(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911203700114

- Martin, A. J., Linfoot, K., & Stephenson, J. (1999). How teachers respond to concerns about misbehavior in their classroom. Psychology in the Schools, 36(4), 347–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199907)36:4<347::AID-PITS7>3.0.CO;2-G

- Mayer, G. R. (2000). Classroom management: A California resource guide for teachers and administrators of elementary and secondary schools. The Los Angeles County Office of Education. https://docplayer.net/283935-Classroom-management-a-california-resource-guide.html

- McKown, C., & Weistein, R. S. (2008). Teacher expectations, classroom context, and the achievement gap. Journal of School Psychology, 46(3), 235–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.001

- Merrett, F., & Whelldall, K. (1993). How do teachers learn to manage classroom behaviour? A study of teachers’ opinions about their initial training with special reference to classroom behaviour management. Educational Studies, 19(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569930190106

- Merriam, S. B. (2002). Introduction to qualitative research. In S. B. Merriam & R. S. Grenier (Eds.), Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis (pp. 33–86). Jossey-Bass.

- Mevorach, M. (2008). Do preschool teachers perceive young children from immigrant families differently? Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 29(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10901020802059508

- Miklikowska, M., Thijs, J., & Hjerm, M. (2019). The impact of perceived teacher support on anti-immigrant attitudes from early to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(6), 1175–1189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00990-8

- Myers, S. S., & Pianta, R. C. (2008). Developmental commentary: Individual and contextual influences on student-teacher relationships and children’s early problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 600–608. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802148160

- Neal, L. V. I., McCray, A. D., & Webb-Johnson, G. (2001). Teachers’ reactions to African American students’ movement styles. Intervention in School and Clinic, 36(3), 168–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/105345120103600306

- Newman, R. S. (2000). Social influences on the development of children’s adaptive help seeking: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Developmental Review, 20(3), 350–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1999.0502

- O’Connor, E. E., Dearing, E., & Collins, B. A. (2011). Teacher-child relationship and behavior problem trajectories in elementary school. American Educational Research Journal, 48(1), 120–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210365008

- O’Kane, C. (2008). The development of participatory techniques; facilitating children’s views about decisions which affect them. In P. Christensen & A. James (Eds.), Research with children: Perspectives and practices (pp. 125–155). Routledge. https://www.scirp.org/(S(lz5mqp453edsnp55rrgjct55))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1908488

- Oztemir, M. T., & Ası, D. S. (2019). How preschoolers and preschool teachers perceive their mutual relationships: Reflections on observed behaviours. Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 48(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2019.1609059

- Öztürk, Y., & Gangal, M. (2016). Okul öncesi eğitim öğretmenlerinin disiplin, sınıf yönetimi ve istenmeyen davranışlar hakkındaki inançları. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.16986/huje.2016015869

- Palermo, F., Hanish, L. D., Martin, C. L., Fabes, R. A., & Reiser, M. (2007). Preschoolers’ academic readiness: What role does the teacher-child relationship play? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.04.002

- Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/10314-000

- Pianta, R. C., & Hamre, B. K. (2001). Students, teachers, and relationship support: Consultant’s manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Ritz, M., Noltemeyer, A., Davis, D., & Green, J. (2014). Behavior management in preschool classrooms: Insights revealed through systematic observation and interview. Psychology in the Schools, 51(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21744

- Sadık, F. (2008). The investigation of strategies to cope with students’ misbehaviors according to teachers and students’ perspectives. Ilkögretim Online, 7(2), 225–232. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Investigation-of-Strategies-to-Cope-with-to-and-Sadik/d3aa1069e65aa106a9a9ba95757e9e3447675926

- Sahin, D., & Anliak, S. (2008). Okul öncesi çocuklarının öğretmenleriyle kurdukları ilişkiyi algılama biçimleri. Egitim Bilimleri ve Uygulama, 7(14), 215–230.

- Sarmini, I., Topçu, E., & Scharbrodt, O. (2020). Integrating Syrian refugee children in Turkey: The role of Turkish language skills (a case study in Gaziantep). International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100007. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100007

- Skivenes, M., & Strandbu, A. (2006). A child perspective and children’s participation. Children, Youth and Environments, 16(2), 10–27. https://munin.uit.no/bitstream/handle/10037/1568/Artikkel3AS.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Stevenson-Hinde, J. (1990). Attachment within family systems: An overview. Infant Mental Health Journal, 11(3), 218–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0355(199023)11:3<218::AID-IMHJ2280110304>3.0.CO;2-1

- Stormont, M., Reinke, W. M., Newcomer, L., Marchese, D., & Lewis, C. (2014). Coaching teachers’ use of social behavior interventions to improve children’s outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(2), 69–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300714550657

- Su, Y. L. (2005). Understanding teachers’ experiences working with young children from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Sutton, R. E., Mudrey-Camino, R., & Knight, C. C. (2009). Teacher’s emotion regulation and classroom management. Theory Into Practice, 48(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840902776418

- Swartz, R. A., & McElwain, N. L. (2012). Preservice teachers’ emotion-related regulation and cognition: Associations with teachers’ responses to children’s emotions in early childhood classrooms. Early Education and Development, 23(2), 202–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2012.619392

- Thijs, J., Westhof, S., & Koomen, H. (2012). Ethnic incongruence and the student-teacher relationship: The perspective of ethnic majority teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 50(2), 257–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.09.004

- Tillery, A. D., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Collins, A. S. (2010). General education teachers’ perceptions of behavior managements and ıntervention strategies. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12(2), 86–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300708330879

- The United Nations Refugee Agency. (2015). Evaluation of UNHCR’s emergency response to the influx of Syrian refugees into Turkey. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/research/evalreports/58a6bbca7/evaluation-unhcrs-emergency-response-influx-syrian-refugees-turkey-full.html?query=turkey

- Torres, M. M., Domitrovich, C. E., & Bierman, K. L. (2015). Preschool interpersonal relationships predict kindergarten achievement: Mediated by gains in emotion knowledge. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 39, 44–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.04.008

- Uğurlu, C. T., Doğan, S., Şöförtakımcı, G., Ay, D., & Zorlu, H. (2014). Öğretmenlerin sınıf ortamında karşılaştıkları istenmeyen davranışlar ve bu davranışlarla baş etme stratejileri. Electronic Turkish Studies, 9(2), 577–602. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.6175

- Uysal, H., Altun., S. A., & Akgün, E. (2010). Okul öncesi öğretmenlerinin çocukların istenmeyen davranışları karşısında uyguladıkları stratejiler. Elementary Education Online, 9(3), 971–979. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/90728

- Vandenbroucke, L., Spilt, J., Verschueren, K., Piccinin, C., & Baeyens, D. (2017). The classroom as a developmental context for cognitive development: A meta-analysis on the importance of teacher-student interactions for children’s executive functions. Review of Educational Research, 88(1), 125–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317743200

- Verschueren, K., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2012). Teacher-child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 205–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

- Westman, S., & Bergmark, V. (2014). A strengthened teaching mission in preschool: Teachers’ experiences, beliefs and strategies. International Journal of Early Years Education, 22(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2013.809653

- White, K. M. (2016). “My teacher helps me”: Assessing teacher-child relationships from the child’s perspective. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2015.1105333

- Wright, A., Gottfried, M. A., & Le, V.-N. (2017). A kindergarten teacher like me: The role of student-teacher race in social-emotional development. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1_suppl), 78–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216635733

- Wubbels, T., Den Brok, P., Veldman, I., & Van Tartwijk, J. (2006). Teacher interpersonal competence for Dutch secondary multicultural classrooms. Teachers and Teaching, 12(4), 407–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13450600600644269