ABSTRACT

Since the end of the Cold War, Germany has been considered a largely safe country. But increasing terrorism, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and national flood disasters with serious consequences have led to growing attention to civil protection issues in politics and society. Thereby the reduction of possible risks is closely linked to rescue forces being well trained and the population being adequately informed about how to behave during disasters. Thus, adult learning is central to reducing risks associated with disasters. This paper, therefore, examines what works are available from adult and continuing education research on disaster protection in Germany after the 2nd World War. The results of this first comprehensive scoping review in this field show that pedagogical issues in disaster risk reduction are addressed by various disciplines. Most of these are practice-oriented and aim for the development of pedagogical concepts. High-quality scientific works that are empirically based or oriented towards the development of theoretical foundations, are hardly to be found. Overall, this in-depth research thus reveals a large research gap in the field of adult pedagogical research on the area of disaster education in Germany.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

The purpose of civil protection is to prepare for crises and disasters, avoid them as far as possible, or minimise their consequences. On the one hand, civil protection can be understood as a bundle of strategies and related measures of governmental or other organisations, which are aimed at the protection of the own population in case of disasters and war impacts. This can be both preventive and aimed at protecting against acute disasters. On the other hand, preventive disaster protection includes also measures for self-protection of the population, which can be actively taken by everyone. This requires knowledge of how to prepare for and behave properly during crises and disasters. The acquisition of the necessary knowledge can be achieved both through further training and informally through the use of a wide range of information sources.

Disasters and crises are not solely a problem in developing countries, even if they face particular challenges in these cases due to a lack of resources, such as professional and necessary equipment for disaster relief. A good example of this is Germany. With the reunification of the two German states in the early 1990s and the end of the Cold War, civil protection became a secondary issue on the political agenda in Germany. It was only with the increase in Islamist-motivated terrorist attacks in Europe (Nesser, Citation2018) and Germany (Rees, Citation2018), various natural disasters such as the major floods in the Ahr Valley (Fekete & Sandholz, Citation2021), the COVID-19 pandemic, and ultimately the war in Ukraine and the associated energy crisis and threat scenario of a blackout that civil protection has once again become a top issue on Germany’s political agenda.

According to a study conducted by the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance (germ. Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe – BBK), knowledge on how to prepare well for crises and disasters is poor among the German population (BBK, Citation2019, p. 4). This situation can be seen as a need to inform the population about self-protection in the event of crises and disasters, and to provide suitable educational opportunities. Additionally, disaster managers must be prepared for their tasks and constantly expand their knowledge in line with new and changing threat levels. As the target groups are primarily adults, this addresses the central issues of adult education (see Section 2).

The question thus arises as to what findings about adult and continuing education research on disaster management are available, and what research gaps exist. In the absence of a systematic account of this, both nationally and internationally, this review aims to provide a basic overview of the research literature on civil protection from an adult and continuing education perspective. Due to the varying historical relevance of civil protection and disaster prevention as well as different structures of civil protection as well as research tradition and structure of adult education research in countries, the focus was placed on Germany. The country represents a special case in that it demonstrates the increasing importance of civil protection and disaster management even for highly industrialised countries and has a large research community in the field of adult education. This leads to the following research question: How does research on adult and continuing education contribute to civil protection in Germany?

2. Civil protection and adult education in Germany

2.1. Structures and terms of civil protection in Germany

Disasters and crises are often divided into categories: natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and droughts; and human-made crises, such as war and internal conflicts (Obura, Citation2003). Political responsibilities in Germany differ depending on the category. Basically, Germany is a federal state divided into states (germ. Bundesländer). States have a certain degree of autonomy and are responsible for certain areas of administration, such as education and infrastructure. The federal government, the ‘Bund’, on the other hand, is responsible for issues that affect Germany as a whole. This system of federalism ‘establishes a constitutionally specified division of powers between different levels of government’ (Bulmer, Citation2017, p. 3).

The protection of the population against disasters is discussed in Germany under civil protection (germ. Bevölkerungsschutz). Civil protection tasks are assigned to different levels of government and are associated with different terms: civil defence (germ. Zivilschutz) was used in Germany mainly during the Cold War and is now understood as part of the national defence policy (Abad et al., Citation2018, p. 5). According to the Basic Law (germ. Grundgesetz), the federal government is responsible for this (Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection, Citation2022, Article 73, § 1). According to the Civil Defence and Disaster Relief Act (germ. Zivilschutz- und Katastrophenhilfegesetz – ZSKG), civil defence includes non-military measures that serve to protect the civilian population, their homes and workplaces, vital or defensible civilian offices, businesses, facilities, and installations, as well as cultural property from the effects of war, and to eliminate or mitigate their consequences (BMI, Citation2020, Article 1, § 1). In addition to wartime conflicts, the federal government also acts in disaster situations of national significance, especially when state resources are insufficient to cope with disasters (BBK, Citationn.d..). In this context, support lines are referred to as disaster assistance (germ. Katastrophenhilfe). The term disaster prevention (germ. Katastrophenschutz) is used to describe actions during a disaster as well as the associated emergency response forces, such as fire departments (Fekete, Citation2012, p. 68). The term civil protection refers to all tasks and measures of disaster assistance, disaster prevention, and civil defence.

Civil protection and its associated disaster management, preparedness, response, and recovery are considered ‘decentralised and localised, in large part due to the federal system of government’ (Chadderton, Citation2015, p. 600) in Germany. Civil protection builds on a local culture in which civil defence and disaster assistance are primarily reserved for trained experts, most of whom are volunteers, for example, in volunteer fire departments or the Federal Agency for Technical Relief (germ. Technisches Hilfswerk, THW) (Chadderton, Citation2015). Politically, however, grounded in national laws and international agreements, one focus of civil defence is on increasing society’s self-protection, preparedness, and resilience.

2.2. Adult and disaster education in Germany

In educational research, there are different perspectives on disasters and crises. On one hand, research focus is on the question of whether the education sector is part of critical infrastructure and how education can be realised under the conditions of crises and disasters or what possible preventive measures exist to avoid crises and disasters through education (e.g. disaster, peace, and democracy education). Internationally, the debate is mostly centred on schools or extracurricular education for children and adolescents (Subarno & Dewi, Citation2022). However, it must be considered, that in industrialised countries such as Germany, a large part of the population is over the age of 18 (Germany: 83.3%). At the same time, qualifications for working in disaster protection and management are almost exclusively aimed at adults, which is why adult education is particularly important for disaster management issues.

Adult education in Germany is organised on a subsidiary and federal basis. The promotion of adult and continuing education is a statutory task for the federal states. State and municipal funding for continuing education is limited to the area of public welfare-oriented continuing education, such as that provided by adult education centres (germ. Volkshochschule) or denominational institutions. They have the mission to cover the general needs of the population for adult education. In doing so, they pursue the objective of offering education to all strata of the population. In addition, there are universities, state vocational training institutions and many private actors that offer further education and training. Statistical surveys consider approximately 60,000 providers of continuing education. In addition, it is assumed that approximately 3,600,000 people in Germany work in adult education. Of these, about 670,000 are salaried employees and civil servants, about 2,610,000 are honorary employees, and about 322,000 do voluntary work (Schrader & Martin, Citation2021).

Parallel to the professionalisation of adult education practice, adult education has also been established as a research discipline since the 1970s. Currently, there are approximately 80 professorships in the narrow field of adult and continuing education. In addition, the Section for Adult Education of the German Society for Educational Science, which represents the interests of adult and continuing education research, currently consists of approximately 500 scientists. Thus, there is a large community of adult educational researchers in Germany.Footnote1

According to the research memorandum for adult and continuing education (Arnold et al., Citation2000), there are five central research areas in adult education:

Adult Learning: Examines how adult learning shapes personal and professional opportunities.

Knowledge Structures and Skill Needs: Focuses on identifying and addressing adult learning goals as needs.

Professional conduct: Addresses issues regarding what is required of individuals working in adult education and how the skills needed to do so are (or can be) acquired.

Institutionalisation: Deals with the characteristics of adult educational institutions and providers.

System and Politics: Investigates the relationship between adult education, society, and politics (ibid.).

Disaster education cannot be assigned explicitly to any of these areas. Rather, relevant questions regarding disaster pedagogy can be found in all the areas. These include preparation for disasters, learning in and from disasters, and the significance of the institutions of adult and continuing education in these phases. If a broader perspective is chosen, the first approaches to disaster pedagogy appear, which can be illuminated regarding their relevance to adult education. For example, the description of civil protection education (germ. Bevölkerungsschutzpädagogik) formulated by the BBK (Karutz & Mitschke, Citation2018). It makes an explicit reference to the role of adult education, considering both organised and informal learning contexts. Civil protection education is described as a cross-disciplinary field that addresses the entire lifespan, as well as different educational domains, in addition to adult education. As reference disciplines, psychology and sociology, as well as other educational subdisciplines such as medical education, are mentioned (ibid.). Another approach is emergency education (germ. Notfallpädagogik) (Karutz, Citation2011). It involves developing theories, concepts, and methods for emergency-related education and training, with the goal of achieving emergency-related maturity and is also known as emergency-related educational science (ibid., p. 16). In this regard it is also a cross-sectional approach for different age groups and educational areas but with a close relationship to psychological and medical issues. Nevertheless, there are no connections to international approaches (see below) as well as a theoretical foundation and systematic reference to adult education to provide a basis for adult education research and practice in the field of civil protection.

Internationally, the approaches to disaster education (Preston & Preston, Citation2012; Shaw et al., Citation2011) and emergency education (Burde et al., Citation2016; Kagawa, Citation2005) are the most well-known. In addition, there are a number of other terms, such as disaster risk education (Baytiyeh, Citation2018), disaster prevention education (Tsai et al., Citation2020), civil defence pedagogy (Chadderton, Citation2015; Preston, Citation2008), and civil defence education (Wirthová & Barták, Citation2022), which are sometimes used synonymously or in close relation (cf. Kitagawa, Citation2021). The educational foundations of these different terms and approaches can also be described as rudimentary, but they serve as a first orientation towards the topic. In general, these are research fields that have various reference disciplines besides educational science (e.g. medicine, engineering, social sciences, psychology).

For educational research, the topic of disasters is relatively new, which is why it is not a sub-discipline, but rather a research field (such as environmental education) that deals with a social problem situation or a field of practice. As is typical, this is a cross-sectional pedagogical field that covers different sub-disciplines of educational science (e.g. school pedagogy, vocational education, and adult education). Even though the goals of individual pedagogical approaches in the context of crisis, disaster, and emergency pedagogy can certainly be considered in the context of lifelong learning, the focus is often on the age range of children and adolescents in the area of elementary education and school, respectively (Subarno & Dewi, Citation2022). The reason for this may be that, among other things, a corresponding pedagogy focuses primarily on vulnerable groups, as has also been shown in the context of the emergency education of the COVID-19 pandemic (Czerniewicz et al., Citation2020). However, adults were not excluded.

An initial review of the research in this area shows, that there are no dedicated contributions to disaster or emergency education in adult and continuing education handbooks (e.g. Kasworm et al., Citation2010; Rocco et al., Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2008; Wilson & Hayes, Citation2000), indicating that this is not a main field of research of the discipline. Nevertheless, critical situations are the subject of adult education, for example, in an individual, biographical dimension (Eschenbacher & Fleming, Citation2021), or as effects of crises on educational offers as well as organisations and structures of adult education (Käpplinger & Lichte, Citation2020). In its self-conception, adult education is closely linked to the management of individual and societal problems in that it can, on the one hand, foster changes as a driver of transformation by reflectively addressing socially relevant issues (e.g. inequality, digitalisation, environment) or, on the other hand, contribute to the solution of these challenges through continuing education.

The relevance of the discipline of adult education in Germany was justified in the early years, primarily because it made a significant contribution to solving societal problems. These include a shortage of skilled workers, the need to raise the general level of education, and the integration of immigrants. Although most people have had little experience with disasters, they have become much more present in their lives. Security at risk is also a threat to people’s freedom and leads to an increasing ‘ratio of prevention’ in society, as well as in pedagogy (Wischmann, Citation2019). Therefore, adult education can be assigned the social task of contributing to effective individual prevention through educational offers. In this context, privatisation tendencies can be observed, i.e. the passing of responsibility on to the individual. These can be found, for example, in relation to the approaches of resilience and preparedness education, which are critically discussed as neoliberal self-optimisation (Joseph, Citation2013). At the same time, there is increasing scepticism about the protective function of the state and also the much-vaunted ‘German Angst’ (Biess, Citation2020), which is understood as a mixture of fear of the future and an extreme need for security. Thus, prevention is increasingly becoming an individual task, also in connection with catastrophes. The prepper community is a good example (Barker, Citation2020).

To date, however, there have only been a few formal training programmes, which is why information from the Internet has been used to a large extent. This includes materials from disaster prevention agencies and organisations, as well as a variety of privately created content shared via social media. From a pedagogical perspective, this can be characterised as informal learning or public pedagogy, although both terms are characterised by great definitional ambiguity (Kitagawa, Citation2017; Werquin, Citation2016). While informal learning focuses on the individual perspective of self-directed learning outside of institutions, public pedagogy emphasises intentional education directed towards the public (Biesta, Citation2014). Thereby, ‘A pedagogy for the public is the most visible and conventional form of public pedagogy in the field of disaster preparedness’. (Kitagawa, Citation2017, p. 7).

While disaster education usually focuses on the preparation of the population, from an adult education perspective, there are other subject areas. These include, from a temporal perspective, learning in and after disasters, as well as the further education of the disaster prevention workers, the professionalisation of the trainers in disaster prevention, as well as the questions on the development of offers, the structure and management of the further education organisations, the governance of the educational offers at a national level, etc.

In summary, coping with emergencies, disasters, and crises is a central theme in adult education, yet it does not seem to be a subject of continuing education research. Therefore, it is of interest to take a closer look at the scientific findings from adult education that are available in the field of emergency and disaster education.

3. Methodology

3.1. Scoping review

To answer the research question, this study has two objectives: first, a review of the entire research literature on adult education in the field of civil protection in Germany. On the other hand, the contributions that originate from the discipline of adult and continuing education should be examined more closely in qualitative terms. A scoping review lends itself to an appropriate method of epistemological interest. Grant and Booth (Citation2009, p. 101) define a scoping review as an initial assessment of available research literature, aiming to determine its size, scope, and ongoing research: ‘Scoping reviews serve multiple purposes: examining research activity, assessing the need for a comprehensive review, summarising findings, and identifying gaps in the literature’ (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005, p. 21). In particular, when the research field has not been extensively studied, scoping reviews have the potential to be ‘stand-alone projects in their own right’ (Mays et al., Citation2001, p. 194). Given the stated objective of this study, a scoping review is an appropriate method. This allows for an overview of the state of (research) literature, the nature and scope of research findings, and the identification and description of phenomena and concepts used in the research field of adult learning and civil protection. Additionally, research gaps have been identified (Munn et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, it can capture how aspects of the research question have been explored in the literature over time (Peters et al., Citation2021, p. 5).

One criticism of scoping reviews is that the studies included in the scoping review are not assessed for their quality, and consequently, this is not outlined in the scoping review (Daudt et al., Citation2013). This is because unlike traditional systematic reviews, a scoping review does not require a critique of the methodological quality of the included studies (Peterson et al., Citation2017, p. 14). Moreover, there is no uniform definition or methodological approach for scoping reviews (ibid.). However, a guideline exists from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (Peters et al., Citation2020), which was substantiated by a group of experts and tested in a Delphi study with experts (Tricco et al., Citation2018, p. 468). The structure of the protocol and reporting of the procedure and results according to PRISMA-ScR (PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews) (ibid.) guide the following presentation of the methodological procedure and results of this research. Thus, the requirement for scoping reviews ‘to be rigorously conducted, transparent, and trustworthy’ (Peters et al., Citation2021, p. 4) can be met.

3.2. Inclusion criteria and search strategy

The inclusion criteria provided the basis for the sources included in the scoping review (Peters et al., Citation2020). Based on the research question, with a focus on Germany based on the PCC framework by Tricco et al. (Citation2018), the population is adult citizens, the concept is civil protection, and the context is adult and continuing education research, using the Research Memorandum for Adult and Continuing Education (see Section 2) as a guide.

In the context of the scoping review, four databases were searched from 5th to 10thDecember 2022: First, the literature database ‘FIS Bildung’,Footnote2 which offers literature references on all sub-areas of education and currently comprises over 1 million records. The literature database was compiled using Specialized Information System Education (germ. Fachinformationssystem Bildung) with its almost 30 cooperation partners from Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The second literature database searched was ‘pollux’.Footnote3 This political science database sustainably optimises the literature supply and information infrastructure in the field of political science in Germany. The third literature database is the DIE Library (germ. DIE-Bibliothek) .Footnote4 This is the largest specialised scientific library for adult education in the German-speaking world. The database is operated by the German Institute for Adult Education (germ. Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung). Finally, the BKK Library (germ. BBK-Mediathek) Footnote5 was searched. This literature database for civil protection originates from the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance.

Based on the PCC framework, (synonymous) search terms and keywords from the fields of civil protection and adult and continuing education were defined. They were exclusively German, as the focus of the research was on Germany. provides an overview of search terms and their combinations. All databases were searched using the following combinations:

Table 1. Overview of the search terms and the search combinations.

After the database search, the literature was reviewed based on the search limitations, and the inclusion criteria are listed in .

Table 2. Overview of the inclusion criteria.

provides an overview of the literature search and result review process based on PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., Citation2018) The steps described were implemented using the Citavi 6Footnote6 literature management programme. Exclusion based on the title, abstract, and title was performed by two reviewers, that is with the dual control principle, which allowed for a detailed assessment of the sources and discussion of discrepancies (Peters et al., Citation2021).

4. Results

Based on the guiding research question ‘What contribution does adult and continuing education research make to civil protection in Germany?’ the following presentation of the results first considers the entire corpus of literature (including grey literature) with the aim of providing a basic overview. Second, a differentiated consideration of the scientific literature is undertaken to generate findings on adult and continuing education research.

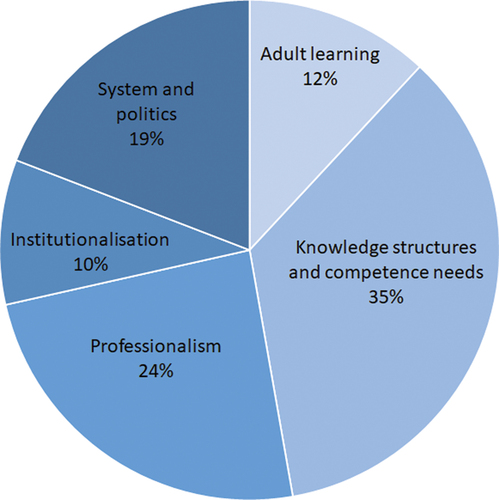

Looking at the entire corpus of literature (n = 234), illustrates that all areas of adult education research were addressed within the scope of the publications. Approximately 2/3 of the publications are thematically in the areas of ‘professional action’ (24%) and ‘knowledge structures and competence needs’ (35%) (see Section 2).

After excluding grey literature (n = 58), theoretical papers were predominant in the area of scientific publications (n = 176), with 82.3% (n = 148). Only 14.9% (n = 28) represented empirical work. The analysis of methodological approaches showed that qualitative approaches predominated with 46% (n = 13) compared to mixed methods (29%, n = 8), as well as quantitative approaches (25%, n = 7).

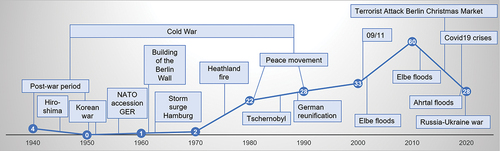

As a further step, the temporal course of the publications as well as the thematic emphases over time were analysed. shows the number of publications by decade, as well as some events relevant to civil protection (cf. Chadderton, Citation2015).

Figure 3. Timeline of the number of publications with presentation of events relevant to civil protection in Germany.

While publications from 1940 to 1950 were primarily concerned with war processing, no or only isolated publications could be identified from 1950 to 1970. Publications from 1980 to 2000 focused not only on nuclear and terrorist threats but also on the further training of professionals in civil protection and on education in voluntary work. This topic is of special relevance because civil protection in Germany is largely based on voluntary work. Thus, further education of professionals in civil protection as well as learning in volunteerism were also found in the years 2000 to 2010; terrorist threats were also addressed within the identified literature in this period. These themes continue from 2010 to 2020, with blackouts appearing as another threat situation, with the use of digital media in teaching and approaches to population protection pedagogy being focused on in the publications. Publications from 2020 onwards additionally address the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

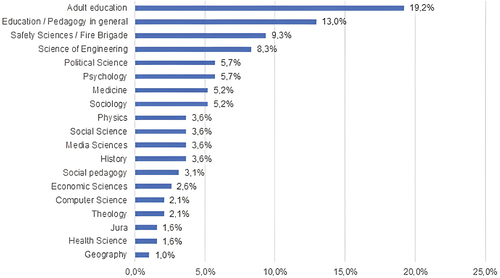

When analysing the disciplinary origin of the authors, it becomes clear that the research field of adult education in civil protection is very interdisciplinary. provides an overview of the disciplines and their percentages in the literature.

Although the disciplines of adult education and educational science are dominant disciplines within the publications, they account for only about one-third of all publications in total. Additionally, many other scientific disciplines have dealt with adult education topics.

In the following analysis, we will take a closer look at the contributions of further education research to civil protection. For this purpose, the research memorandum on adult education served as a structure (see Section 2). provides an overview of the categorisation of the publications found. It was possible to identify 34 publications that can most frequently be assigned to the research field ‘Adult Learning’ (n = 13) and ‘Knowledge Structures and Skill Needs’ (n = 16). In contrast, the research fields ‘Professional conduct’ (n = 2), ‘Institutionalisation’ (n = 2), and ‘System and Politics’ (n = 1) were addressed much less frequently. All contributions were assigned only to the research field that was in focus.

Table 3. Allocation of research literature to research fields in adult education (cf. Arnold et al., Citation2000.).

Some research fields and their subcategories are only sporadically researched or not at all researched, although relevant starting points could definitely be identified from the perspective of adult education research. Furthermore, despite legal and international efforts, little scientific research in the field of self-protection can be seen, with approximately 17% (n = 30 of n = 176). The implications of this for adult and continuing education in civil protection, and the extent to which the findings of the German case study can be informative for other countries, are discussed in the following section.

5. Discussion

Looking at the contributions of adult education research to civil protection in Germany, it is fundamentally apparent that there is little research and publication in the field. The identified literature can be characterised as primarily practice-oriented and conceptual. Thus, there is also a gap with respect to peer-reviewed publications, developing theory and empirical research. Overall, it can be concluded that there is little high-quality research and only a rudimentary scientific discussion on adult education and civil protection in Germany.

One explanation is rooted in the history of civil protection and adult education in Germany (cf. ). After the Second World War, civil protection had even greater significance, which continued through the Cuban Missile Crisis in the 1960s and the Cold War period as a whole. Germany had a special role in this due to the ties between the two German states and the two opposing superpowers and can be seen as a central area of confrontation. However, adult education was not yet well developed as a field of research at that time, especially in the GDR. As the discipline expanded from the 1980s, however, the relevance of civil protection also declined and finally lost its importance altogether with the reunification of the two German states in 1990. One possible cause could be found in this opposing development.

Since the 2000s, there has been a noticeable increase in natural disasters, terrorism, and security threats, which has also led to an increase in publications on civil protection and adult and continuing education. As a result of these developments, growing interest in civil protection can also be expected in politics and society. This presents an opportunity, especially in view of the ‘vulnerability paradox’ (T’Hart, Citation1997), to impart relevant knowledge and competencies of civil protection at all political and societal levels. In accordance with Prior et al. (Citation2016), modern threats and risks, such as those posed by digitisation and globalisation, have led to increased vulnerability regarding the failure of critical infrastructure (CSI), affecting both national and international transportation, electricity, telecommunications, and water supply systems (p. 8). Knowledge of the interdependence of the sector needs to be conveyed to professionals in this field, such as CSI managers, while the European Union also requires cross-border coordination and sharing of civil protection resources, as well as coordination between traditionally separate national civil protection and emergency management organisations (ibid., p. 9). Thus, professional-level competencies need to be supported by appropriate continuing education measures to achieve successful coordination and cooperation. Simultaneously, the population is affected by its dependence on CSI. On the one hand, they must be prepared in the case of CSI failure. On the other hand, they must also develop an awareness of the new form of ‘hybrid warfare’ which, as seen in the Ukraine conflict, involves the use of subversive, economic, information, and diplomatic means, as well as military force (Clark, Citation2020, p. 8). Adult education can support the population in developing the competencies necessary for appropriate behaviour in such situations.

Furthermore, decision makers and professionals in civil protection are also affected by these threats and must be facilitated by appropriate educational strategies at all levels to ensure effective protection of the population. This is particularly important in view of the high proportion of volunteers in the German civil protection institutions. Thereby crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate the effects of globalisation, with national actions having international repercussions. This is also relevant for the promotion of preparedness and resilience, which is grounded in international agreements, such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNISDR, Citation2015), to which Germany has committed itself as a member of the UN. Resilience-conditioning preparedness for disasters is composed of ‘self-help, mutual-help and public-help’ (Oikawa, Citation2014a, p. 165). Thus, education for disaster risk reduction should find its way into formal education through appropriate curricula and especially into non-formal education as ‘the entry point of education for […] disaster risk reduction’ (Shaw, Citation2014, p. 7). This is also reinforced by the fact that international agreements ‘reducing disaster risks and their impact has become an important development issue in its own right’ (ibid.). Special attention is paid to climate change, which is one of the “’creeping’ emergencies” (Kagawa, Citation2005) and can result in various disasters. Consequently, closely related to this disaster risk reduction is Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). ESD also requires a lifelong learning process and is thus tangentially related to the field of adult education and pursues the goals: ‘Learning to know: recognising the challenge; learning to do: acting with determination; learning to be: invisibility of human dignity’ (Shaw, Citation2014, p. 2). Due to different environmental crises, such as global warming, desertification, biodiversity crises, and the destruction of the rainforest, educational processes to increase public awareness, basic education, and training programmes for all sectors are required (Oikawa, Citation2014b, p. 16). Germany has a double role here: On the one hand, the country itself is affected by the consequences of climate change (see section 1), on the other hand, the country also has a responsibility, fixed in the international agreements outlined, to support developing countries or countries with many crises and thus prevent disasters. Consequently, developing and testing appropriate concepts of education for disaster risk reduction and ESD on a supra-regional and science-based basis would represent an important step towards achieving the goals of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNISDR, Citation2015) and strengthening the resilience of nations and communities internationally. The competencies needed for self-protection, preparedness, and resilience are fundamental, and therefore, transferable to a large extent internationally. In addition, Germany’s international cooperation in civil protection makes it possible to implement these concepts in low- and middle-income countries, and in countries affected by many conflicts. This is also relevant because of the effects of globalisation described above and the fact that disasters have no regional boundaries and can therefore cause neighbouring regions of different countries to have to support each other, making competent action and corresponding knowledge even more important for disaster management (cf. Klein et al., Citation2022). This concerns political decision makers, professionals in civil protection, volunteers, and the general population.

Adult education can play a crucial role in citizens acquiring the competencies necessary for coping with the threats and impacts of disasters, including climate change, because these challenges can be seen as opportunities for transformative learning processes, associated with a change in frame of reference, i.e. knowledge, beliefs, behaviours and attitudes (Mezirow, Citation2009; Sharpe, Citation2016, p. 218). This is also shown in empirical studies. For example, Dahl and Millora (Citation2016) examined the influence of natural disasters on lifelong learning, focusing on the experiences of university leaders in the Philippines following a typhoon. This study integrated the concepts of transformative learning by Mezirow (Citation2009), critical educational theory by Freire (Citation1973), and the psychosocial theory of group processes by Lewin (Citation1966). The findings indicate that learning processes after natural disasters can be transformative, particularly when they give rise to a disorienting dilemma that depends on individual experiences with disasters (Dahl & Millora, Citation2016). Social groups play a significant role in facilitating reflection and learning through their group dynamics (ibid.). Consequently, reflection on such events often occurs within social spaces, and can lead to concrete actions and policy changes (ibid.). It is emphasised that learning encompasses not only cognitive aspects, but also internal emotions and personal significance (ibid.). Adult education can support these learning processes that can lead to increased disaster preparedness by creating a space for transformative and reflexive learning (ibid.). Choudhury et al. (Citation2021) also emphasised the importance of individual-level learning processes in influencing community-level change and resilience. They highlight the complex relationship between transformative learning and resilience building, involving various social, cultural, and structural factors (ibid.). These factors include beliefs, values, power structures, practical considerations and cognitive aspects (ibid.). The authors emphasise that resilience cannot be enhanced through learning alone unless it is translated into concrete measures (ibid.). Therefore, it is the responsibility of adult education to facilitate the overcoming of cognitive barriers through educational opportunities, thereby promoting reflection and agency to strengthen community resilience to disaster shocks. This entails creating flexible learning experiences that are adaptable to complex disaster risks, enabling individuals to reflect upon and evaluate their cultural contexts (Sharpe, Citation2016). In addition to fundamental research on the design of adult education, which has already been explained in this article, it also requires the creation of corresponding political conditions.

In this regard, the present research is helpful in that research gaps can be identified, and evidence for (supra-)regional research can be presented so that the discipline of adult and continuing education can strengthen education for disaster risk reduction and ESD. In this regard, a basic conceptual pedagogy in the form of a ‘public pedagogy’ (Kitagawa, Citation2017) is also called for in order to be able to develop diverse approaches, ground them theoretically, and entrench them in the learning processes of all actors involved. Public pedagogy aims to engage and educate the public, promoting critical thinking, social awareness, and active citizenship (Kitagawa, Citation2018). It emphasises the role of education in shaping public discourse, fostering democratic participation, and addressing social issues (ibid.). Kitagawa (Citation2021) highlights the importance of ‘public pedagogy’ as a framework for disaster education (DE), emphasising the difference between authority-led DE, which involves teaching and instruction, and public-led DE, which focuses on participation, engagement, and influencing decision-making processes (Kitagawa, Citation2021). Public pedagogy therefore offers a more democratic and inclusive approach to DE, empowering the public to actively shape and contribute to disaster risk reduction efforts (ibid.).

In this context, possible inequalities in the education system can and must also be critically discussed, which also lead to different preconditions with crises, emergencies and disasters in the field of education. This concerns the special consideration of vulnerable and disadvantaged target groups in the context of disaster pedagogy, e.g. for people with disabilities or low reading skills. In general, it is important to note that individuals or groups of individuals, because of their historical-structural marginalisation, must be given special attention so that they are not affected by crises and disasters to a greater extent than other groups (Erman et al., Citation2021; Reid, Citation2013). This raises the question of the perspective from which approaches to preparing for crises and disasters are developed and how one-sided views can be overcome (Kragt, Citation2021). To this end, e.g. the training courses must be designed methodically and in terms of content in such a way that they meet the special requirements for the (self-)protection of these target groups. In addition, trainers in disaster management must be trained in such a way that they take special account of these target groups. Overall, it is necessary to move away from the previous concepts of a partly elitist, because very presuppositional precaution, to solidary approaches, which are oriented towards mutual support in disaster situations.

Regarding the research fields of adult and continuing education, it is clear that adult education research in Germany focuses on the field of adult learning in crises and disasters. Other research fields are (partly) considered in publications, but scientific discourse often takes place in other disciplines. This is particularly evident in the research field of professional action, where, although a relatively large number of publications could be identified in the literature corpus (n = 174) with 51 scientific publications, only a small number of these (n = 2) originated from the discipline of adult education. This indicates that professional expertise is not combined with the necessary perspectives on adult education in disaster prevention and management. In other words, professionalisation seems to be an important topic for civil protection, but is mainly addressed from a technical perspective.

Another challenge is that the activities require high professionalism under high psychological pressure. In contrast, a large part of the people working in this field are volunteers. This raises the question of how high-quality education and training can be realised under these conditions. This includes both the necessary structures and the training of teachers who are also volunteer staff. For this purpose, basic research is also necessary to grasp the requirements of adult educators in civil protection and to support the planning of offers in terms of adult education. The importance of knowledge about learning processes in volunteer work is also illustrated by the thematic focus of the publications (cf. Section 4). Here, adult education research should tie in with the findings of the discipline in order to be able to promote the learning processes and competencies of professionals.

In the field of institutionalisation, it is necessary to first analyse the heterogeneous providers in this field. In addition to the central support institutions, private providers are also becoming more prevalent. In addition, the amount of content on civil protection on the internet is growing. Informal communities are emerging, such as the preppers, who deal with questions of preparedness (Luke, Citation2021). On the one hand, it is interesting to analyse these informal learning processes in order to gain insights into the education of the population as a whole. On the other hand, dangerous connections to conspiracy theories and behaviour that endangers the state are revealed, which can and must be prevented by appropriate interventions of a political adult education. A better understanding of the structures of formal training as well as informal learning processes in civil protection is therefore urgently needed.

Potential avenues of adult education research and civil protection become apparent with regard to the identification of research gaps and their elimination from an international perspective, the cooperation of different disciplines to be able to communicate the complex subject contents of civil protection to the heterogeneous target group of the population or professionals and political decision makers, as well as the necessity of a research-based institutionalisation of education in civil protection. Only this way can international goals such as those of the SFDRR or Sustainable Development Goals (UN, Citationn.d..) be achieved. As explained, there are already international concepts for education on crises and disasters (cf. Section 2.2). However, it is still stated that ‘“Disaster education” has been studied in various disciplines such as disaster risk management and environmental studies. However, disaster education is a relatively “new enquiry” in the field of education’ (Kitagawa, Citation2021), highlighting the need for empirical research and conceptualisations in this area at an international level. Thus, the discipline of adult education research is challenged to close the research gap through high-quality basic theoretical and empirical research work, and to develop concepts that strengthen civil protection through individual and social learning processes, promotion of professional action for national but also international issues.

6. Conclusion and limitations

In summary, this research highlighted two aspects: On the one hand, that the topic of civil protection is relevant to the discipline of adult education research and should be researched; on the other hand, in Germany, research in this field to date has been conducted primarily outside of the relevant discipline and largely without connection to its expertise. Simultaneously, there is a strong focus on a few research areas and a lack of theoretical and empirical research in the field of adult and continuing education in civil protection in Germany.

The reason for this can be seen in the in the opposing development of a decreasing historical endangerment and the growth of adult education in in Germany till the 2000er. The relevance of this field has increased with the natural disasters, as well as security and terrorist threats of the last centuries. The term ‘Zeitenwende’ (an epochal tectonic shift), used by the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz (Kluth, Citation2022), illustrates the current paradigm shift and the associated growing importance of civil protection. In this respect, as well as with regard to the international agreements to which Germany has committed itself, an intensification of German adult education research with regard to civil protection is necessary. Only this way can the international ‘paradigm shift’ (Fekete, Citation2021, p. 21), from the pure consideration of crisis and disaster phenomena per se to ‘impacts, vulnerabilities, and resilience’ (ibid.) be undertaken so that appropriate preparation and learning can also occur.

The focus of the article on Germany illustrates the increased relevance of the topic for industrialised countries as well as for adult education. It becomes clear that country-specific characteristics have a great influence on the research of education in civil protection. At the same time, the analysis of the research areas of adult education also reveals gaps that have not been addressed or have only been addressed to a very limited extent. This in-depth analysis was only possible through a comprehensive country-specific review of the literature and will also open up the possibility of country-specific comparisons in the future. At the same time, the international interdependencies in civil protection show that national developments cannot be considered independently of global challenges. Thus, the insight provided here is also an important basis for educational research in civil protection in other countries.

Despite a justified restriction to Germany, the central limitation of this study lies precisely in its focus. An additional analysis of the state of research on adult and continuing education in other countries could make valuable contributions to the development of adult education research in Germany. Furthermore, by including the literature on civil protection in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) before 1989, further valuable insights can be expected, as civil protection was more important here than in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). In addition, the development of further practice-related literature (e.g. professional societies, associations, and political actors) on civil protection can be used to obtain a comprehensive picture of adult education in civil protection. This would provide a basis for establishing adult education research in the field of civil protection and disaster management, thus addressing an important gap in preparing for disasters and reducing the associated risks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

References

- Abad, J., Booth, L. M., Marx, S., Ettinger, S., & Gérard, F. (2018). Comparison of national strategies in France, Germany and Switzerland for DRR and cross-border crisis management. Procedia Engineering, 212, 879–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.113

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arnold, R., Faulstich, P., Mader, W., Nuissl von Rein, E., & Schlutz, E. (2000). Forschungsmemorandum für die Erwachsenen- und Weiterbildung. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung: https://d-nb.info/969942753/34.

- Barker, K. (2020). How to survive the end ft he future: Preppers, pathology, and the everyday crisis of insecurity. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(2), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12362

- Baytiyeh, H. (2018). Can disaster risk education reduce the impacts of recurring disasters on developing societies? Education and Urban Society, 50(3), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124517713111

- BBK. (2019). Rahmenkonzept Ausbildung in Erster Hilfe mit Selbstschutzinhalten: Selbstschutzausbildung mit kompetenzorientiertem Ansatz. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.bbk.bund.de/DE/Themen/Akademie-BABZ/BABZ-Angebot/Studium-Ausbildung-im-BeVS/EHSH/_documents/Rahmenkonzept.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1.

- BBK. (n.d.). Wie funktioniert der deutsche Bevölkerungsschutz? Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://www.bbk.bund.de/DE/Das-BBK/Das-BBK-stellt-sich-vor/Das-deutsche-Bevoelkerungsschutzsystem/das-deutsche-bevoelkerungsschutzsystem.

- Biess, F. (2020). German angst: Fear and democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany. Oxford University Press.

- Biesta, G. (2014). Making pedagogy public. For the public, of the public, or in the interest of Publicness? In J. Burdick, J. A. Sandlin, & M. P. O’Malley (Eds.), Problematizing public pedagogy (pp. 15–25). Routledge.

- BMI. (2020). Gesetz über den Zivilschutz und die Katastrophenhilfe des Bundes (Zivilschutz- und Katastrophenhilfegesetz – ZSKG) [Civil Defense and Disaster Relief Act – ZSKG]. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from https://www.bbk.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Rechtsgrundlagen/zskg.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=8.

- Bulmer, E. (2017). Federalism: International IDEA constitution-building primer 12 (Andra upplagan). International IDEA. https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2018.29

- Burde, D., Kapit, A., Wahl, R. L., Guven, O., & Skarpeteig, M. I. (2016). Education in emergencies: A review of theory and research. Review of Educational Research, 87(3), 619–658. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316671594

- Chadderton, C. (2015). Civil defence pedagogies and narratives of democracy: Disaster education in Germany. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 34(5), 589–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2015.1073186

- Choudhury, M.-U.-I., Haque, C. E., & Hostetler, G. (2021). Transformative learning and community resilience to cyclones and storm surges: The case of coastal communities in Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 55, 102063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102063

- Clark, M. (2020). Russian hybrid warfare: Military learning and the future of war series. Institute for the Study of War.

- Czerniewicz, L., Agherdien, N., Badenhorst, J., Belluigi, D., Chambers, T., Chili, M. (2020). A wake-up call: Equity, inequality and covid-19 emergency remote teaching and learning. Postdigital Science & Education, 2(3), 946–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00187-4

- Dahl, K. K. B., & Millora, C. M. (2016). Lifelong learning from natural disasters: Transformative group-based learning at Philippine universities. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 35(6), 648–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2016.1209587

- Daudt, H. M. L., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Erman, A., De Vries Robbé, S. A., Thies, S. F., Kabir, K., & Maruo, M. (2021). Gender dimensions of disaster risk and resilience. World Bank Group. https://doi.org/10.1596/35202

- Eschenbacher, S., & Fleming, T. (2021). Toward a critical pedagogy of crisis. European Journal for Research on the Education & Learning of Adults, 12(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.3384/rela.2000-7426.3337

- Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection. (2022). Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/.

- Fekete, A. (2012). Safety and security target levels: Opportunities and challenges for risk management and risk communication. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.09.001

- Fekete, A. (2021). Motivation, satisfaction, and risks of operational forces and helpers regarding the 2021 and 2013 flood operations in Germany. Sustainability, 13(22), 12587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212587

- Fekete, A., & Sandholz, S. (2021). Here comes the flood, but not failure? Lessons to learn after the heavy rain and pluvial floods in Germany 2021. Water, 13(21), 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13213016

- Franke, D. (2008). Ein Haus im Wandel der Zeit. In B. für Bevölkerungsschutz & Katastrophenhilfe (Eds.), 50 Jahre Zivil- und Bevölkerungsschutz in Deutschland (pp. 10–29). Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe.

- Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. Seabury.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Joseph, J. (2013). Resilience as embedded neoliberalism: A governmentality approach. International Policies, Practices and Discourses, 1(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2013.765741

- Kagawa, F. (2005). Emergency education: A critical review of the field. Comparative Education, 41(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060500317620

- Käpplinger, B., & Lichte, N. (2020). “The lockdown of physical co-operation touches the heart of adult education”: A delphi study on immediate and expected effects of COVID-19. International Review of Education, 66(5–6), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09871-w

- Karutz, H. (2011). Notfallpädagogik. Stumpf und Kossendey.

- Karutz, H., & Mitschke, T. (2018). Pädagogik und Bildungsverständnis im Bevölkerungsschutz. Bevölkerungsschutz, (4), 2–7.

- Kasworm, C. E., Rose, A. D., & Ross-Gordon, J. M. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of adult and continuing education. Sage.

- Kitagawa, K. (2017). Situating preparedness education within public pedagogy. Pedagogy Culture & Society, 25(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1200660

- Kitagawa, K. (2018). Questioning ‘integrated’ disaster risk reduction and ‘all of society’ engagement: Can ‘preparedness pedagogy’ help? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(6), 851–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1464385

- Kitagawa, K. (2021). Conceptualising ‘disaster education’. Education Sciences, 11(5), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050233

- Klein, M., Wiens, M., & Schultmann, F. (2022). Borderland resilience, willingness to help and trust–an empirical study of the French-German border area. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 99, 101898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2022.101898

- Kluth, A. (2022). This is the dawning of the age of Zeitenwende. Retrieved January 19, 2023, from https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-12-23/zeitenwende-could-be-the-name-of-our-era-as-germany-s-olaf-scholz-declared.

- Kragt, A. (2021). Critical perspectives on education in emergencies. University of Amsterdam.

- Lewin, K. (1966). Group decision and social change. In E. E. Maccoby, T. M. Newcomb, & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology (3rd ed., pp. 197–211). Holt, Rinehart and & Winston.

- Luke, T. (2021). Beyond prepper culture as right-wing extremism: Selling preparedness to everyday consumers as how to survive the end of the World on a budget. Fast Capitalism, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.32855/fcapital.202101.005

- Mays, N., Roberts, E., & Popay, J. (2001). Synthesising research evidence. In N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, & N. Black (Eds.), Studying the organization and delivery of health services. Research methods (pp. 188–220). Routledge.

- Mezirow, J. (2009). An overview on transformative learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning. Learning theorists … in their own words (pp. S. 90–105). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nesser, P. (5 December. 2018). “Europe hasn’t won the war on terror”. Politico. Retrieved December 9, 2018, from https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-hasnt-won-the-war-on-terror/.

- Obura, A. (2003). Never again: Educational reconstruction in Rwanda. International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Oikawa, Y. (2014a). City level response: Linking ESD and DRR in Kesennuma. In R. Shaw & Y. Oikawa (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction, methods, approaches and practices. Education for sustainable development and disaster risk reduction (pp. 155–176). Springer Japan.

- Oikawa, Y. (2014b). Education for Sustainable development: Trends and practices. In R. Shaw & Y. Oikawa (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction, methods, approaches and practices. Education for sustainable development and disaster risk reduction (pp. 15–35). Springer Japan.

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIRM-20-01.

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277

- Peterson, J., Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., & Langford, C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12380

- Preston, J. (2008). Protect and survive: ‘whiteness’ and the middle‐class family in civil defence pedagogies. Journal of Education Policy, 23(5), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802054412

- Preston, J., & Preston, J. (2012). Disaster education. ‘Race’, equity and pedagogy. SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-873-5

- Prior, T., Herzog, M., Kaderli, T., & Roth, F. (2016). International civil protection Adapting to new challenges, risk and resilience report. Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich.

- Rees, D. A. (2018). Weak but Good? German Counterterrorism Strategy Since 2015. American Intelligence Journal, 35(2), 74–82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26566568

- Reid, M. (2013). Disasters and social inequalities. Sociology Compass, 7(11), 984–997. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12080

- Rocco, T. S., Smith, M. C., Mizzi, R. C., Merriweather, L. R., & Hawley, J. D. (2021). The Handbook of Adult and continuing education. Stylus.

- Schrader, J., & Martin, A. (2021). Weiterbildungsanbieter in Deutschland: Befunde aus dem DIE-Weiterbildungskataster. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 44(3), 333–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-021-00198-z

- Sharpe, J. (2016). Understanding and unlocking transformative learning as a method for enabling behaviour change for adaptation and resilience to disaster threats. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 17, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.04.014

- Shaw, R. (2014). Overview of concepts: Education for Sustainable development and disaster risk reduction. In R. Shaw & Y. Oikawa (Eds.), Disaster risk reduction, methods, approaches and practices. Education for sustainable development and disaster risk reduction (pp. 1–13). Springer Japan.

- Shaw, R., Shiwaku, K., & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.). (2011). Community, environment and disaster risk management. Disaster education. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Smith, M. C., DeFrates-Densch, N., Smith, M. C., & DeFrates-Densch, A. E. (2008). Handbook of research on adult learning and development. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203887882

- Subarno, A., & Dewi, A. S. (2022). A systematic review of the shape of disaster education. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 986(1), 12011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/986/1/012011

- T’Hart, P. (1997). Preparing policy makers for crisis management: The role of simulations. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 5(4), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.00058

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tsai, M.-H., Chang, Y.-L., Shiau, J.-S., & Wang, S.-M. (2020). Exploring the effects of a serious game-based learning package for disaster prevention education: The case of battle of flooding protection. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 43, 101393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101393

- UN. (n.d.). THE 17 GOALS. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- UNISDR. (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 - 2030. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.

- Werquin, P. (2016). International perspectives on the definition of informal learning. In M. Rohs (Ed.), Handbuch Informelles Lernen (pp. 39–64). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-05953-8_4

- Wilson, A. L., & Hayes, E. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of adult and continuing education (New Edition ed.). Wiley.

- Wirthová, J., & Barták, T. (2022). Civil defence education: (non)specific dangers and destabilisation of actorship in education. Human Affairs, 32(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/humaff-2022-0014

- Wischmann, A. (2019). Prävention – Preparedness – Resilienz.: Strategien einer neoliberalen Public Pedagogy. In A. Czejkowska & S. Spieker (Eds.), Jahrbuch für Pädagogik 2019 (pp. 185–198). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/jp012019k_185