?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

What and how students learn depend largely on how they think they will be assessed. This study aimed to explore medical students’ perception of the value of assessment and feedback on their learning, and how this relates to their examination performance. A mixed methods research design was adopted in which a questionnaire was developed and administered to the students to gain their perceptions of assessments. Perceptions were further explored in focus group discussions. Survey findings were correlated with students’ performance data and academic coordinators’ perceptions. Students’ perceptions of the level of difficulty of different assessments mirrored their performance in examinations, with an improvement observed in clinical assessments as students progressed through their degree. Students recognised that feedback is important to allow improvements and seek more timely, better quality and personalised feedback. Academic coordinators identified that some of the students’ suggestions are more realistic than others. Students had a positive attitude towards assessment, but emphasised the need for educators to highlight the relevance of assessment to clinical practice.

Introduction

Effective assessment in medical education requires tasks that assess cognitive, psychomotor and communication skills while also assessing professionalism attributes. In 2010, a consensus framework for good assessment was developed at the Ottawa Conference (Norcini et al., Citation2011). The framework for single assessments identifies construct validity, reproducibility, equivalence, acceptability, feasibility, educational benefit and timely feedback as key elements. This approach motivates learners and provides educators with the opportunity to drive learning through assessment (Norcini et al., Citation2018). However, single methods of assessment alone are unable to assess all the attributes required to become a competent health professional. A systems-based framework has been suggested to blend single assessments in order to achieve the most benefit for all stakeholders (Norcini et al., Citation2018).

With increasing awareness that assessment should include elements of this framework, medical educators are encouraged to engage in an integrated approach to the teaching, learning and assessment process. This fosters the involvement of students as active and informed participants, and the development of assessment tasks, which are authentic, meaningful and engaging (Boud and Falchikov Citation2006; Biggs and Tang Citation2007; Rust Citation2007). The context and purpose of assessment influence the importance of the individual elements identified in the framework. The elements of the framework are also not weighted equally by students and educators for the same assessment task (Norcini et al., Citation2018). Consequently, the assessment challenge is to use appropriate methods from the perspective of impact on learning (Fry, Ketteridge and Marshall, Citation2009). In deciding the assessment task, it is necessary to judge the extent to which they embody the target performance of understanding, and how well they lend themselves to evaluating individual student performances (Biggs and Tang, Citation2007). It is generally acknowledged that assessment drives learning; however, assessment can have both intended and unintended consequences (Schuwirth and Van der Vleuten, Citation2004). Students study more thoughtfully when they anticipate certain examination formats, and changes in the format can shift their focus to clinical rather than theoretical issues (Epstein, Citation2007).

The role of assessment in learning in higher education has been questioned (James et al. Citation2002; Lizzo et al. 2002; Al-Kadri et al. Citation2012). What and how students learn depends largely on how they think they will be assessed; hence, assessment should become a strategic tool for enhancing teaching and learning in higher education (Pereira et al. Citation2015). Assessment practices must send the right cues to students about what and how they should be learning. More often than not, wrong signals are sent to students (Duffield and Spencer Citation2002); thus, it is important to examine students’ perceptions of the purposes of assessment, the relationship between assessment and the assumed nature of what is being assessed, and how different assessment formats impact on learning. In addition to evaluating students’ perceptions of assessment, it is important to also consider the educators’ perceptions as well as direct measures of learning, such as students’ examination scores and assessment rubrics, to ensure accurate evaluation of the learning process (Poirier et al. Citation2009).

This paper focuses on exploring medical students’ perceptions of their assessment load as well as the quality and impact of assessment and feedback on their learning in the context of an integrated undergraduate medical course at a regional Australian university. The study also examined the congruence between students’ perceptions of assessment experience and their actual performance in examinations. Students’ perceptions for each year group were also discussed with their respective academic coordinators. This approach was utilised to ensure valid measurement of impact of learning as evidenced by multiple sources. The strengths and limitations of the various assessment instruments were also outlined, the appropriateness of the instruments relative to the outcomes were discussed and modifications proffered.

Organisational Context

The MBBS course at James Cook University (JCU) is an integrated undergraduate 6 year programme which is delivered with some clinical exposure from year one and focuses on social accountability and rural, remote, Indigenous and tropical health. The first three years of the course provide a systems-based introduction to the foundations of medicine, with early experiences in rural placements. The final three years of the programme comprise community teaching practices and small regional and rural hospital-based rotations with the sixth year specifically designated as the pre-intern year. Students are enrolled in two/three chained subjects (these are interrelated subjects that require sequential enrolment) for each academic year. The assessment formats used in the course vary from subject to subject, including written examinations such as multiple choice questions (MCQ), extended matching questions (EMQ), short answer questions (SAQ), essay questions, portfolio, mini clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX), practical/case reports and clinical examinations - multi-station assessment tasks (MSAT) and objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE). Details of the suite of assessment instruments used are presented in .

Table 1: Assessment Formats and their Descriptors

Methodology

Study design

A mixed methods sequential explanatory design utilising quantitative and qualitative data collection methods was adopted for this study (Cresswell and Clark 2007). Quantitative data collected through a paper-based questionnaire and examination performance data were further explored using focus group discussions with medical students from all years of study. The focus group discussion approach was an effective way to collectively explore shared experiences and confront taken for granted assumptions (Breen Citation2006; Barbour Citation2013). Furthermore, focus group discussions were more practical and cost-effective than individual interviews. The opinions of the academic co-ordinators about the validity of the findings from the focus group discussions with the students were sought individually.

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted over two years (2016-2017) among consenting Years 1-6 medical students at JCU. Four focus group discussions were held with year 2, 3, 4 and 5/6 students. Some year 1 students consented to participate in the study but they did not turn up. The focus group discussions were facilitated by academic staff members who had background knowledge in student assessment. Subsequently, summary findings from the focus group discussions were discussed with the academic coordinators who are charged with developing and deploying the curriculum and assessment that the students commented on. The academic co-ordinators were contacted individually.

Study instruments

The questionnaire was developed through an extensive review of literature and the questions were divided into two sections. The first section included questions about participants’ demographic characteristics (year of study, enrolment status and sex). The second section contained six different questions that related to participants’ perceptions of assessment. The first of these questions assessed students’ perception of the level of accuracy of each of the current suite of assessment tools in reflecting the effort they put into learning. Students’ perceptions about the accuracy of the assessment tool in reflecting effort put into learning and knowledge of content material were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not applicable, 1 = least, 2 = moderate and 3 = most). A 5-point Likert scale was used to assess assessment load rating (very light = 1 to very heavy = 5) and the usefulness of on-course assessment (not at useful = 1 to very useful = 5). Participants were also required to select the best descriptor (1 out of 3) of their perception of assessment. With the last question, participants were asked to provide free-text comments on the one thing about assessment that they would want to change. Details of the questionnaire content are presented in .

Table 2. Survey on Perceptions of Assessment

The survey questions were divided into two sections.

Section A: The first section included questions about participants’ demographic characteristics (year of study, enrolment status and gender).

Section B: The second section contained six different questions which related to participants’ perceptions of assessment.

Semi structured interviews were used for the focus group discussions. The questions focused on the key elements identified by Norcini et al. (Citation2018) in their framework for good assessment. Four major themes were used to facilitate in-depth exploration of the findings from the questionnaires. The themes included (a) broad concepts on assessment (b) assessment structure specific to the course (c) impact of assessment and (d) feedback.

Ethical considerations

Approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Human Ethics Review Committee (H6921).

Data Collection

The quantitative data comprised students’ self-reported perceptions of assessment, which were collected through paper-based questionnaires and their 5-year (2013 to 2017 inclusive) examination performance data across five year levels of the medical program. The sixth year is pre-intern year with total focus on placements; therefore, their assessment data were excluded from the analysis. Congruence between the survey and performance data were assessed. Qualitative data collection included focus group discussions with the participants. Findings from the focus group discussions with students were subsequently discussed with the academic coordinators. Individual discussions with the academic coordinators were structured around the validity of the students’ perceptions of assessment as well as the appropriateness and feasibility of the students’ suggestions for change.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were cleaned and analyzed using SPSS (version 23). The reliability of the questionnaire was tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Descriptive statistics were used to compute frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. One-way analysis of variance was used to examine mean performance score between the different year groups for each assessment tool. The qualitative data was transcribed verbatim and QRS NVivo 11 was used to store, organise and analyse the data. Initial themes were developed and finalised through constant comparison. Both deductive (coding schema from questions and quantitative results) and inductive coding was undertaken. Negative cases/outliers were investigated. Themes were further developed and refined through discussion among the research team and verification from the literature.

Following a sequential mixed methods design, through deductive coding of the qualitative data, themes that further explored the findings from the quantitative data analysis were identified. Furthermore, through inductive coding additional themes emerged from the focus group discussions.

Results

Quantitative

Cronbach’s alpha was 0.816, indicating that the survey instrument had high reliability and internal consistency. Five hundred and fifty students (response rate = 51%) participated in the survey: 23.6% of the participants were year 1 students, 62.2% were females and 85.8% were domestic students. Details of demographic characteristics of survey participants are illustrated in and the figures are similar to the whole cohort profile and therefore considered to be representative of the population.

Table 3: Demographics of participants (quantitative survey)

Twenty four students participated in four focus group discussions, organised by year group. (). General characteristics are presented to ensure anonymity.

Table 4. Demographics of participants (qualitative focus group discussions)

The major findings from the survey that also emerged in the qualitative data were perceptions of the different assessment instruments, role of on-course and formative assessment, and impact of assessment on learning. New themes that emerged from the focus group discussions included quality of feedback, standardisation of marking, relevance of assessment tasks and professional readiness.

Perceptions of the different assessment instruments

As shown in , KFP, SAQ and MSAT were perceived as the most accurate tools in reflecting effort put into learning by 50.8%, 46.2% and 31.6% of the students, while reflective writing (6.5%), essay (8.2%) and mini-CEX (8.4%) were rated as least accurate. Similarly, in relation to knowledge of content material, KFP (48.3%) was rated as the most accurate assessment method that reflected knowledge of content material, followed by SAQ (46.2%) and MCQ (30.4%). Reflective writing (3.5%), essay (5%) and case report (7.5%) were regarded as the least accurate assessment methods that reflect knowledge of content material.

Table 5. Accuracy of different assessment tools in reflecting effort put into learning and knowledge of content materialTable Footnote*

In the focus group discussions, students indicated that they appreciated the variety of assessment types offered during the course and acknowledged that such variety was important to suit different learning styles and the needs of different learners: “I think if you only have one type of assessment you'd be missing out on some really valuable people that maybe aren't good at that particular type of assessment” (female 5, year 2).

The students felt MCQs better reflected their study efforts while SAQs were a more accurate reflection of what they had learnt:” but short answer really does reflect what I know, I think” (female 2, year 2).The key feature paper (KFP) was perceived as an avenue to showcase the capacity to apply acquired knowledge to a clinical scenario, and many students commented that this assessment type was crucial for clinical practice. However, students felt that the weightings of assignments did not always reflect the time and effort put into these assessment pieces. Furthermore, pre-clinical students wanted more practice on SAQs. Students in the clinical years also reported on the mini-CEX, indicating that the experience was variable depending on the discipline; “would be more useful if the clinician had scheduled the time and got the patient for the student, but this was often the exception rather than the rule” (male 1 year 6).

Students’ performance on the different assessment types

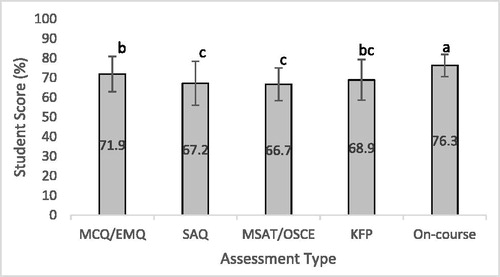

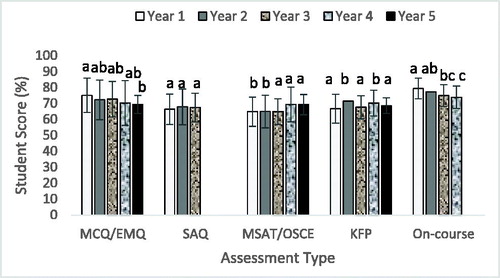

depicts overall students’ average performance scores over a 5-year period (2013 to 2017). Mean scores ranged from 66.7% to 76.3%, with students’ scores in on-course assessment being significantly higher than other assessment types. MCQ examination scores were significantly different to SAQ, KFP and MSAT/OSCE. This trend was similar for all year groups with junior students having significantly higher scores than senior students in MCQs (F = 4.105, df = 4, p = 0.014) and on-course assessments (F = 7.213, df = 3, p = 0.003). By contrast, the senior students had higher scores (F = 3.90, df = 4, p =0.017) in MSAT/OSCE ().

Figure 1. Students' performance in the different assessments

Medical students' mean performance scores in various on-course and end of semester assessment items from 2013 to 2017. Bars bearing different letter(s) are significantly different. Students’ scores in on-course assessment were significantly different to their scores on all other assessments P < 0.05 (a). MCQs scores were significantly different to SAQ (short answer questions) and MSAT/OSCE (multi-station assessment task/objective structured clinical exam) scores P < 0.01 (b), but not different to KFP scores. No significant difference was noted between SAQ, MSAT/OSCE and KFP.

Figure 2. Performance Scores by Year of study

First to fifth year medical students' performance scores in various on-course and end of semester assessment items from 2013 to 2017. Bars within same assessment type that bear different letter(s) are significantly different. Junior students had significantly higher performance scores in their MCQ (multiple-choice questions) and on-course assessments than the seniors p < 0.05, while the senior students had higher scores in their MSAT/OSCE (multi-station assessment task/objective structured clinical exam) p < 0.05.

These results indicate congruence between students’ perceptions of the difficulty level of the different assessment instruments and their actual performance in the examinations. The focus group participants reported that the SAQs were the most difficult and they always do better in MCQs: “most difficult is short answer for me. I always do better in MCQs but I feel like they're a little bit easier” (female 5, year 2). Additionally, analysis of the examination scores showed that students got lower mean scores in MCQs and higher mean scores in KFP, MSAT and OSCEs as they progressed through the course, indicating improved performance in the clinical assessment, and this was confirmed in the focus group discussions, with participants reporting more confidence as they progressed: “I've had a lot more growth as a clinician just this year than almost any other year. More than any other year, for sure” (male 1, year 6). Interestingly, although students complained about reflective writing they performed well in this assessment task with an average of 73.2 ± 6.4. This implies that performance may not be an indication of perceived relevance of an assessment tool to learning.

Role of on-course assessment and assessment load

As shown in , students generally felt that on-course assessment was very useful in driving their learning (3.67 0.94), with significantly higher ratings (p < 0.000) from the first year students in comparison to the seniors. Similarly, female and international students gave higher ratings in comparison to their respective counterparts but the differences were not significant. Furthermore, students indicated that the assessment load was relatively heavy (3.67 ± 0.77), with higher, though non-significant, ratings by year 4 students, males and domestic students than their respective counterparts. In the focus group discussions, the year 6 students felt it would be good to keep the examination load low in sixth year, as less pressure gives students time to consolidate knowledge and prepare for professional practice.

Table 6. Perceptions of on-course assessment and assessment load (MeanSD)

Students were in favour of more frequent on-line formative quizzes. They indicated that ungraded weekly quizzes would serve as a good resource to guide preparation for examinations and for the identification of knowledge gaps: “I would like to be assessed in a way which sort of improves how I go on semester… You could see how you were going and then improve, and the feedback was really helpful in making it” (female 2 year 3). One student also felt that quizzes would help students understand “the level of knowledge” that they needed as they felt that they could” overestimate or underestimate the level that… [lecturers] want” (female 1 year 2).

Impact of assessment on learning

A large percentage of the participants (55.1%) perceived that assessment is an avenue to quantify their level of knowledge and/or competence, while 35.3% believed that assessment assists them to recognise current gaps that may exist in their learning and only 13.1% of the respondents felt that assessment enables them to address gaps in their learning.

When discussing attitudes towards assessments, student felt that, overall, medical students enjoy being assessed because they are a competitive “bunch of perfectionists who have achieved 99% [in all subjects] at school” (male 1, year 4), who strive for excellence and enjoy “seeing a mark or seeing an achievement from what kind of work they put in” (female 2, year 2).

Despite this positive attitude towards assessment, students mostly discussed assessments for their “summative” functions, such as verifying that students acquire, understand and apply new knowledge, and assuring that students “move forward” in their learning. Ultimately, assessment helped students meet standards for clinical practice: “Just as a marker for how you're going with the course content. Otherwise, how would you really know whether or not somebody's reaching or ticking off all the minimum requirements” (male 3, year 6). Although the students acknowledged the value of formative assessment in addressing knowledge gaps, providing motivation for students to work hard, and informing future learning, they felt this type of assessment was not emphasised enough. These results align with the findings that emerged from the open-text survey comments, as students wanted more frequent on-line formative quizzes to guide preparation for examinations and for the identification of knowledge gaps.

Quality and Timeliness of feedback

Discussions on feedback highlighted different areas for improvement. Often feedback was deemed to be too generalised and of poor quality: “in general, I haven't received any in-depth feedback about any of my assignments so far. I've always just had, say, a line” (female 3, Year 2); “[For one essay], when I got feedback, just had ticks all the way through and then ‘good work’ at the end” (male 1, year 4).

Students also pointed out that the turnaround time for feedback was “unacceptable”. Personalised feedback was preferred when feasible, so that students could actually use the comments to improve their performance. However, participants understood that with large student numbers, this might be difficult to achieve. Students recommended the provision of generalised group feedback, indicating that this would be better than having no feedback.

Standardisation of marking

Marking was perceived as inconsistent between different markers or too harsh. Students often found the marking rubrics too vague, not tailored to the assignment and open to various interpretations. They recommended that marking rubrics should be detailed, clearer and better linked with feedback: “I am sure that this university has really capable markers but I think the rubrics let them down and that's why they'll have such great variation, because they [the rubrics] are really vague” (female 1, year 3).

Relevance of assessment tasks

Students indicated that most assessments were relevant to professional practice. The few assessment pieces that were not popular with students were mainly because they could not appreciate the relevance to their learning or to clinical practice. If assessments are deemed relevant and important, students will put more effort into completing the tasks: “If you think it's relevant then you're happy to do it because you realise the importance of it” (male 2, year 5); “If we realise the importance, we might put a lot more effort into it” (female 1, year 6).

At the beginning of each study period, year 1-3 students complete an individual learning plan (ILP) that outlines their study goals, study style, how they need to adapt for university study and their study-life-work balance. Students discuss their ILP with a dedicated tutor. Generally, participants were not in favour of doing ILPs every study period in the pre-clinical years. They acknowledged that ILPs are relatively useful in the first year in terms of setting academic goals and designing action plans. However, the assessment piece becomes “a waste of time” and “excessive” (female 3, year 2) in later years as “nobody does it properly after first year, students only copy the answers [from last years’ ILP]” (female 3, year 3).

Similarly, the academic value of reflective writing was not appreciated as the majority of students did not see the link between this form of assessment and professional practice. Moreover, the marking of reflective writing pieces was also perceived as unfair, with students being marked for “content” rather than for their capacity to “reflect”: “We're often told you should write about what you think, what you feel, and sometimes what we feel doesn't match up with what the medical school's expectations of that assessment piece is” (male 1, year 6).

Given the subjectivity of reflection, the students felt that reflective pieces should be hurdles rather than summative assessment pieces. This was a view shared by all year groups as they indicated that completing reflective pieces every year was excessive, unnecessary and boring.

There were some participants who acknowledged the value of assessment tasks that required reflective writing. A second year student appreciated that there was a direct link with reflection and professional practice as a doctor:

“A doctor needs to be reflective. You have to be judging your behaviour… you might be experiencing someone's death or someone's diagnosis… So you have to be constantly reflecting on those sorts of things. So they're just teaching us - most of us are pretty young and maybe haven't had that much experience with reflecting on some really big issues. So as much as I know that we hate them [reflective pieces] and they seem like a bit of a joke because they're not deep and sciency and difficult, it is difficult to reflect on your own emotions about things”. (Female 5, year 2)

A second student agreed and acknowledged the learning value of reflection for medical students. She acknowledged that an assignment which required reflection on “gossip” provided her with a platform for transformative learning as it brought about some behavioural changes in her.

“I have a similar opinion. Sure, it's very boring when you're doing the reflective assignments, to be honest, but by the time you're at the end of it, you actually have learned something. I just have learned something. For example… the gossip essay… I have never thought of what I'm doing when I've said something. But now I actually think about it when I say something. I kind of changed my thinking to when I listen to someone say something about someone. So, I think it does help but I think it's - how boring it gets when you're writing something so dry sometimes”. (Female 2, year 2)

However, a year 6 student felt that the use of group reflection or workshop sessions would be more valuable and relevant, particularly if this involved reflecting on students’ own clinical experiences:

“idea of having a group reflective session, I think that would work much better, because we're required to do written reflective … But if we did it in a group setting, and there was a facilitator who asked specific questions that they were trying to get us to think about, I think that would be a useful way to get us to reflect on our clinical experiences” (male 1, year 6).

Academic Coordinators’ Perspective

From the perspective of the academic staff who are charged with developing and deploying the curriculum and assessment that the students commented on, there are some common themes when considering the appropriateness of student suggestions for change. Through the lens of what is educationally sound and practically appropriate for the specific curriculum, the following categories were identified: realistic/possible ideas, approaches that have been tried in the past and abandoned, and inaccurate/inappropriate. The majority of the suggestions/comments from the students (across all year groups) could be described as ‘realistic’. Examples of the ‘realistic’ category include suggestions for more detailed rubrics to improve feedback, graded weekly quizzes to measure learning and reduce marks on main examinations, and setting assignment deadlines at appropriate intervals from other items of work.

The number of approaches that had been previously abandoned or suggestions that were inappropriate/inaccurate were significantly fewer. Examples include the introduction of a mid-year practical examination (MSAT, for the pre-clinical years). This was done previously for a number of years, and was subsequently abandoned, in part as a response to student feedback on its value in balance with practical considerations of running large, complex examinations multiple times in an academic year. Similarly, a request for the provision of exemplars reflects where a practice was introduced and subsequently abandoned due to students not engaging with the exemplars in an appropriate manner (plagiarism, copying of formatting in contradiction to updated instructions).

Examples of inappropriate student suggestions included one that posited that students be provided with a ‘choice’ of which questions to answer on examination papers to suit their interests, knowledge and skills. Inaccurate statements include errors of fact regarding the timing, length or opportunities for feedback on particular items. Of these themes, it is important to note that the senior students’ suggestions were more realistic. The highest numbers of non-realistic categories were found in 2nd year responses, while all of the 5th and 6th year student’s suggestions could be considered realistic/possible.

Discussion

This study has highlighted the experiences and perceptions of medical students regarding assessment. The students acknowledged the distinctiveness of the JCU medical curriculum, which allows for rural placements and electives, and wished JCU would continue to maintain such distinctiveness. Overall, our findings corroborate previous research as they indicate that the effort and time put into learning is highly influenced by the type and relevance of assessment (Gibbs Citation2006; Norcini et al. Citation2011; Al-Kadri et al. Citation2012). The students identified many issues related to the quality of assessment and feedback. Other issues identified included relevance of assessment tasks, grading discrepancies and poor standardisation of marking.

Timeliness and consistency of assessment and feedback

Feedback is not only a key component of student learning but is also a surrogate for teaching quality (Aguis and Wilkinson, Citation2014). Overall, students were unhappy with the lack of timeliness, consistency and poor quality of the feedback they received across all the years. This has been documented by other studies both nationally and internationally (Cockett and Jackson, Citation2018). With regards to timeliness, students felt the turnover time was too long for written assignments. There was also mention of lack of feedback on examinations and guided learning tasks. The need for immediate feedback has been validated in a literature review by Aguis and Wilkinson (Citation2014). While timeliness of feedback is a recurring theme in the literature, students expect this as it provides them an opportunity to improve in subsequent assessment tasks (Poulos and Mahony, Citation2008) and also as a form of reassurance (Robinson, Pope, and Holyoak., 2013). Addressing slow turnaround times is difficult and is driven by availability of resources and student numbers. Suggested strategies include providing exemplars, peer feedback and additional emotional support to improve student expectations with timeliness of feedback (Robinson, Pope and Holyoak, Citation2013; Aguis and Wilkinson, Citation2014). Students in this study expressed similar views for both formative and summative assessments. However, this is worth investigating further.

The majority of students across the years felt that written feedback was of poor quality, very brief or included a series of “ticks” with very little or no comment on how to improve. This appears to be an ongoing issue across undergraduate medical institutions worldwide (Bartlett, Crossley and Mckinley, Citation2017). Students also hoped for constructive, personalised feedback. It has been well documented in the literature that personalised, constructive, specific and detailed feedback leads to increased engagement and student learning (Parboteeah and Anwar Citation2009). Students valued feedback when it included focused suggestions on improvement either in the form of written comments, including examples and explanations in case of written assessment pieces or immediate verbal feedback when clinical examination tasks were performed (Aguis and Wilkinson Citation2014). Poulos and Mahony (Citation2008) noted that this was essential for health care students to improve not only their grades but also future clinical practice. This was echoed by the study participants, especially those in the final years of the course. However, providing written feedback alone may not make a difference. Students need to have the skills to interpret and reflect on the feedback provided (Weaver Citation2006; Burke Citation2009).

Assessment rubrics have been implemented by universities as a way of standardising feedback and providing consistency thereby improving the quality of feedback (Reddy and Andrade Citation2010; Cockett and Jackson Citation2018). Despite criticism in the literature about the usefulness of rubrics from a staff perspective (Reddy and Andrade Citation2010), students were in favour of using rubrics as a good learning tool (Tractenberg and Fitzgerald Citation2012; Cockett and Jackson Citation2018). Comments by students on vague marking criteria using subjective terms and unrealistic expectations were recurring themes in this study. The use of explicit marking criteria, knowledge and familiarity of the rubric, creating rubrics in consultation with students can improve academic performance and enhance students’ satisfaction with feedback (Cockett and Jackson Citation2018). Students need to be educated on how to use and interpret the rubric if it is to have an impact on their learning. It is also important for markers to be trained in the development and use of rubrics for it to be a reliable feedback tool (Reddy and Andrade Citation2010).

Relevance - From learning for examinations to learning to be a doctor

Overall, the students expressed satisfaction with the clinical skills learnt and felt the course prepared them well for professional practice. They particularly valued assessments that were relevant to professional practice, built on their skill set, involved an element of choice and were associated with a balanced workload. The students also wanted more explicit explanations on the rationale for the different types of assessments, course structure and subjects, and to be given – where possible – the chance to follow their own interests when addressing an assignment like a reflective piece. This validates Keppell and Carless’ (Citation2006) assertion that assessments should develop real world skills in students. Craddock and Mathias (Citation2009) similarly found that choice had a positive effect on student grades.

Analysis of the 5-year examination results indicated good alignment between students’ perceptions of the difficulty level of the different assessment instruments and their actual performance in the examinations. Although KFPs and SAQs were rated higher in terms of accuracy in reflecting effort put into learning and knowledge of content materials, the students had higher performance scores in MCQs compared to KFPs and SAQs. This could have mainly been because MCQ is typically the most common assessment format. The 5-year aggregated examination results showed improved performance in clinically-based assessments as students progressed through the year levels/course, possibly due to them becoming more accustomed to these assessment formats over time, with increasing confidence and adoption of better techniques to handle these forms of assessment during examinations. Combining evidence from direct measures of student learning (performance scores) and students’ perceptions as proposed by Poirier et al. (Citation2009) and DiPiro (Citation2010) have provided a balanced and accurate evaluation of assessment quality in this study.

The students’ perception of the assessment workload is consistent with previous research. In the literature, medical students stated that the assessment and course workload were extensive and were identified as common sources of stress and examination anxiety (Hashmat et al. 2008). Despite the perception of the assessment load, the students’ considered assessments as useful in driving learning. According to Wormald et al. (Citation2009), the assessment weighting of a subject improved the students’ motivation to learn the subject.

The appropriateness of student’s suggestions for change appear to on balance be mostly realistic and can be seen to be in agreement with what academic staff view as being appropriate. This congruence becomes even more pronounced as the students become more senior. This suggests that the length of time in the course may coincide with an increasing level of insight and understanding from students of the intended learning outcomes and design considerations of the assessment items they undertake. This would be in keeping with Lynam and Cachia’s (Citation2017) findings that student engagement with assessment was positively aligned with increasing academic maturity. It is also a likely reflection of the increasing ‘authenticity’ of assessment as the curriculum moves into the clinically focused years by allowing more practical and clinically applied tasks to be set, in contrast to testing scientific knowledge and generic skill development in the junior years (Gulikers et al. Citation2004).

Reflection as a professional skill

Reflection enables students to actively learn from their experiences (Chambers, Brosnan and Hassell, Citation2011) and assess a range of knowledge, skills and competencies including: professionalism (Stark et al. Citation2006; Hulsman, Harmsen and Fabriek, Citation2009; Moniz et al. Citation2015), self-care (Saunders et al. Citation2007; Rakel and Hedgecock Citation2008; Braun et al. Citation2013), empathy, communication, collaboration, clinical reasoning (Moniz et al. Citation2015) and the social determinants of health (van den Heuvel et al. Citation2014). Medical students’ ability to reflect is critical for their professional identify formation (Hoffman et al. Citation2016) and ability to work in complex settings (Koole et al. Citation2012). However, in this study, most students did not appreciate the value of reflection and the link with professional practice. Studies have demonstrated that students can “play the game” following a “recipe” in order to pass but have little understanding of the reasons for assessment (Chambers et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, students can suffer from “reflection fatigue” (Shemtob Citation2016; Trumbo Citation2017). Reflective assessments can be enhanced by ensuring early exposure to facilitate engagement (Kanthan and Senger Citation2011) and using reflection as part of “meaningful encounters and teachable moments” (Branch and Paranjape Citation2002, 1187) in clinical settings. Furthermore, students and assessors need to appreciate that reflection is a complex meta-cognitive process that involves recognition of students’ own cognitive functioning (Sobral Citation2005).

Recommendations and Future Research

Students valued feedback that is more detailed and see it as essential to improve their learning. Immediate and constructive feedback may be helpful especially when offered in specific and explicit form. Additionally, tutors should be provided with training on the assessment process and how to give feedback.

Students were concerned about different assessment protocols, vagueness of marking rubrics and associated standards of grading. Engagement and shared information between students and tutors, with clear instructions on expectations and criteria for grading may help clarify these standards. Marking rubrics also need to be made more explicit.

Spreading assessment tasks across the semester may alleviate the feeling of been choked up with assessment timelines. Provision of more authentic assessments will also help students value the learning process.

Educators need to engage in deliberate collaborative design of reflective tasks with students to foster engagement.

Future research could assess the factors that determine students’ insight into the role of assessment and how this insight affects their learning.

Strengths and Limitations of the study

The main strength of this study is the use of mixed methods to triangulate data and provide contextual and deep understanding of the data findings. Additionally, there was no researcher bias and the participants were free to express their candid opinions because the academics who conducted the study were external to the discipline though they had knowledge of teaching and assessment. A major limitation of this study is the large number of participants in some of the focus group discussions with a few dominant voices. However, some focus groups were small (three participants). There were also the added dynamics of older and younger year students. In addition, this study may not be generalizable to other settings with different teaching and assessment methods.

Conclusion

It is key to develop assessment tasks that fulfil the framework for good assessment. This includes both individual assessments and systems assessment. Emerging issues for students include transparency, relevance, fairness and meaningful and timely feedback of assessment tasks. Students as important stakeholders should actively seek information and feedback to support their learning. Educators need to utilise the assessment framework effectively in the development of assessment tasks in order to encourage learning and keep students engaged. Understanding student perceptions of the various assessment tasks and the impact this has on their learning will help educators and institutions develop assessment tasks, which address student needs, while at the same time fulfilling the context and purpose of assessment in medical education.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of all the medical students and academics who participated in this study. Research assistance provided by Faith Alele and Mary Adu is greatly appreciated.

References

- Aguis, N. M., and A. Wilkinson. 2014. “Students’ and Teachers’ Views of Written Feedback at Undergraduate Level: A Literature Review.” Nurse Education Today 34: 552–559 doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.005.

- Al-Kadri, H. M., M. S. Al-Moamary, H. Al-Takroni, C. Roberts, and C. P. van der Vleuten. 2012. “Self-assessment and Students' Study Strategies in a Community of Clinical Practice: A Qualitative Study.” Medical Education Online 17 (1): 11204. doi:10.3402/meo.v17i0.11204.

- Barbour R. 2013. “Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student’s Guide.” London: Sage Publications.

- Bartlett, M., J. Crossley, and R. McKinley. 2017. “Improving the Quality of Written Feedback using Written Feedback.” Education for Primary Care 28: (1): 16–22. doi:10.1080/14739879.2016.1217171.

- Biggs, J., and C. Tang. 2007. “Teaching for Quality Learning at University” (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill, Maidenhead.

- Boud, D. and N. Falchikov. 2006. “Aligning Assessment with Long-term Learning.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 31: 399–413. doi:10.1080/02602930600679050.

- Branch, W. T. J., and A. Paranjape. 2002. “Feedback and Reflection: Teaching Methods for Clinical Settings.” Academic Medicine 77 (12): 1185–1188. doi:10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005.

- Braun, U. K., A. C. Gill., C. R. Teal, and L. J. Morrison. 2013. “The Utility of Reflective Writing after a Palliative Care Experience: Can We Assess Medical Students' Professionalism?” Journal of Palliative Medicine 16 (11): 1342–1349. doi:10.1089/jpm.2012.0462.

- Breen, R. L. 2006. A Practical Guide to Focus-group Research. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30(3): 463–475. doi:10.1080/03098260600927575.

- Burke, D., 2009. Strategies for using Feedback Students bring to Higher Education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 34 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1080/02602930801895711.

- Chambers, S., C. Brosnan, and A. Hassell. 2011. “Introducing Medical Students to Reflective Practice.” Education for Primary Care 22 (2): 100–105. doi:10.1080/14739879.2011.11493975.

- Cockett, A. and C. Jackson. 2018. “The Use of Assessment Rubrics to Enhance Feedback in Higher Education: An Integrative Literature Review.” Nurse Education Today 69: 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2018.06.022.

- Craddock, D., and H. Mathias. 2009. “Assessment Options in Higher Education.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 34: 127–140. doi:10.1080/02602930801956026.

- Creswell, J.W., and V.L.P. Clark. 2007. “Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research.” Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage.

- DiPiro, J. T. 2010. “Student Learning: Perception versus Reality.” American Journal of Pharmacy Education 74 (4): Article 63. doi:10.5688/aj740463.

- Duffield, K. E. and J. A. Spencer. 2002. “A Survey of Medical Students’ Views about the Purposes and Fairness of Assessment”. Medical Education, 36(9): 879–886. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01291.x.

- Epstein, R. M. 2007. “Assessment in Medical Education.” The New England Journal of Medicine 356: 387–396. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054784.

- Fry, H., S. Ketteridge. and S. Marshall. 2009. “A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.” (3rd ed.) London: Routledge.

- Gibbs, G. 2006. “How Assessment Frames Student Learning.” In Innovative Assessment in Higher Education, edited by C. Bryan & K. Clegg, 23–36. London: Routledge.

- Gulikers, J. T. M., T. J. Bastiaens, and P. A. Kirschner. 2004. “A Five-dimensional Framework for Authentic Assessment.” Educational Technology Research and Development 52: 67. doi:10.1007/BF02504676.

- Hashimat, S., M. Hashimat, F. Amanullah. and S. Aziz. 2008. “Factors causing Exam Anxiety in Medical Students.” Journal of Pakistan Medical Association 58: 167–70.

- Hoffman, L. A., R. L. Shew, T. R. Vu, J. J. Brokaw, and R. M. Frankel. 2016. “Is Reflective Ability Associated With Professionalism Lapses During Medical School?” Academic Medicine 91 (6): 853–857. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001094.

- Hulsman, R. L., A. B. Harmsen, and M. Fabriek. 2009. “Reflective Teaching of Medical Communication Skills with DiViDU: Assessing the Level of Student Reflection on Recorded Consultations with Simulated Patients.” Patient Education and Counselling 74 (2): 142–149. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.009.

- James, R., C. McInnis, and M. Devlin. 2002. “Assessing Learning in Australian Universities.” Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher Education. Retrieved November 8, 2018, http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au.

- Kanthan, R., and J. L. Senger. 2011. “An Appraisal of Students' Awareness of Self-reflection in a First-year Pathology Course of Undergraduate Medical/Dental Education.” BMC Medical Education 11: 67.

- Keppell, M., and D. Carless. 2006. “Learning‐oriented Assessment: A Technology‐Based Case Study.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 13 (2): 179–191. doi:10.1080/09695940600703944.

- Koole, S., T. Dornan, L. Aper, B. De Wever, A. Scherpbier, M. Valcke, … A. Derese. 2012. “Using video-cases to assess student reflection: development and validation of an instrument.” BMC Medical Education 12: 22.

- Lizzio, A., K. Wilson, and R. Simons. 2002. “University Students’ Perceptions of the Learning Environment and Academic Outcomes: Implications for Theory and Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 27 (1): 27–52. – doi:10.1080/03075070120099359.

- Lynam, S., and M. Cachia. 2017. “Students’ Perceptions of the Role of Assessments at Higher Education.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 23 (2):223–234. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1329928.

- McLachlan, J.C. 2006. “The Relationship between Assessment and Learning.” Medical Education 40: 716–717. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02518.x.

- Moniz, T., S. Arntfield, K. Miller, L. Lingard, C. Watling, and G. Regehr. 2015. “Considerations in the use of Reflective Writing for Student Assessment: Issues of Reliability and Validity.” Medical Education 49 (9): 901–908. doi:10.1111/medu.12771.

- Norcini, J., B. Anderson, V. Bollela, V.Burch, M. J. Costa, R. Duvivier, R. Galbraith, R. Hays, A. Kent, V. Perrott, and T. Roberts. 2011. “Criteria for Good Assessment: Consensus Statement and Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference.” Medical Teacher 33 (3): 206–214. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.551559.

- Norcini, J., B. Anderson, V. Bollela, V. Burch, M. J. Costa, R. Duvivier, R. Hays, M. F. P. Mackay, T. Roberts, and D. Swanson. 2018. “2018 Consensus Framework for Good Assessment.” Medical Teacher 40 (11): 1102–1109. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016.

- Parboteeah, S., and M. Anwar. 2009. “Thematic Analysis of Written Assignment Feedback: Implications for Nurse Education.” Nurse Education Today 29: 753–757. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2009.02.017.

- Pereira, D., A. M. Flores, and L. Niklasson. 2015. “Assessment Revisited: A Review of Research in Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (7): 1008–1032. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1055233.

- Poirier, T., M. Crouch, G. MacKinnon, R. Mehvar, and M. Monk-Tutor. 2009. “Updated Guidelines for Manuscripts Describing Instructional Design and Assessment: The IDEAS Format.” American Journal of Pharmacy Education 73 (3): Article 55. doi:10.5688/aj680492.

- Poulos, A and M. J. Mahony. 2008. “Effectiveness of Feedback: The Students’ Perspective.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 33: (2): 143–154. doi:10.1080/02602930601127869.

- Rakel, D. P., and J. Hedgecock. 2008. “Healing the Healer: A Tool to encourage Student Reflection towards Health.” Medical Teacher 30 (6): 633–635. doi:10.1080/01421590802206754.

- Reddy, Y. M., and H. Andrade. 2010. “A Review of Rubric use in Higher Education.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (4): 435–448. doi:10.1080/02602930902862859.

- Robinson, S., D. Pope, and L. Holyoak. 2013. “Can we meet their Expectations? Experiences and Perceptions of Feedback in First Year Undergraduate Students.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 38 3: 260–272. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.629291.

- Rust, C. 2007. “Towards a Scholarship of Assessment.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 32 (2): 29–37.

- Saunders, P. A., Tractenberg, R. E., Chaterji, R., Amri, H., Harazduk, N., Gordon, J. S., … Haramati, A. 2007. “Promoting Self-awareness and Reflection through an Experiential Mind-body Skills Course for First Year Medical Students.” Medical Teacher 29 (8): 778–784. doi:10.1080/01421590701509647.

- Schuwirth, L. W., and C. P. van der Vleuten. 2004. “Merging Views on Assessment.” Medical Education 38: 1208–1210. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02055.x.

- Shemtob, L. 2016. “Reflecting on Reflection: A Medical Student’s Perspective.” Academic Medicine 91 (9): 1190–1191. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001303.

- Sobral, D. T. 2005. “Medical Students' Mindset for Reflective Learning: A Revalidation Study of the Reflection-in-Learning Scale.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 10 (4): 303–314. doi:10.1007/s10459-005-8239-0.

- Stark, P., C. Roberts, D. Newble, and N. Bax. 2006. “Discovering Professionalism through Guided Reflection.” Medical Teacher 28 (1): e25–31. doi:10.1080/01421590600568520.

- Tractenberg, R. E., and K. T. FitzGerald. 2012. “A Mastery Rubric for the Design and Evaluation of an Institutional Curriculum in the Responsible Conduct of Research.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (8): 1003–1021. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.596923.

- Trumbo, S. P. 2017. “Reflection Fatigue among Medical Students.” Academic Medicine 92 (4): 433–434. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001609.

- van den Heuvel, M., H. Au, L. Levin, S. Bernstein, E. Ford-Jones, and M. A. Martimianakis. 2014. “Evaluation of a Social Pediatrics Elective: Transforming Students' Perspective through Reflection.” Clinical Pediatrics 53(6), 549–555. doi:10.1177/0009922814526974.

- Weaver, M.R. 2006. “Do Students Value Feedback? Student Perceptions of Tutors’ Written Response.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 31 3: 379–394. doi:10.1080/02602930500353061.

- Wormald, BW., S. Schoeman, A. Somasunderam, and M. Penn. 2009. “Assessment Drives Learning: an Unavoidable Truth?” Anatomical Sciences Education 2: 199–204. doi:10.1002/ase.102.