Abstract

Despite the increasing popularity of formative assessment as an instructional tool, teachers find it difficult to implement formative assessment strategies in their practice. To address this we developed a training programme based on formative assessment and scaffolding literature. A quasi-experimental design was utilised to examine the programme’s usefulness; 8 teachers in higher education received the training and eight teachers did not. A questionnaire (N = 260) was administered before and after the training to determine students’ perceptions of their teachers’ adaptive behaviour. The trained teachers also participated in an interview about the usefulness of the training. Although no significant interaction effects between time and group were found, results over time reveal that both trained and untrained teachers showed more adaptive behaviour by providing more challenge when needed. Both groups of teachers also showed more non-adaptive behaviour since they gave more support and challenge than needed and became less supportive when students needed support. Results between groups indicate that trained teachers showed more adaptive behaviour than untrained teachers. Interview results indicate that teachers reviewed the training positively and reported scaffolding theory as a useful addition. Teachers requested more time and support to implement newly learned strategies in daily practice.

Introduction

Formative assessment has become a well-known and important concept in education and research (Black and Wiliam Citation2018; Schildkamp et al. Citation2020). Formative assessment is defined as a process of constant interaction between students and teacher (Black and Wiliam Citation2012), and should be viewed as an integral part of teaching and learning (Leenknecht et al. Citation2021). However, formative assessment approaches are not regularly adopted in classroom practice (Robinson et al. Citation2014; Boud et al. Citation2018). Teachers appear to have trouble implementing formative assessment approaches in their daily practice (Schildkamp et al. Citation2020). They have insufficient knowledge of what formative assessment is (Robinson et al. Citation2014), and lack practical examples of formative assessment approaches (Box, Skoog, and Dabbs Citation2015). In this study, we designed a training programme aimed at improving university teachers’ capabilities to use formative assessment approaches in the classroom. To provide the practical examples teachers need, this study makes use of teachers’ support strategies described in scaffolding literature (Van de Pol et al. Citation2014).

Formative assessment’s cyclical nature

Formative assessment is defined as a process (Black and Wiliam Citation2012). Most daily educational practices tend to focus on if students have learned, while it seems more logical to also focus on what students have learned to improve both teaching and learning (Pryor and Crossouard Citation2008). A focus on what students have learned provides insight into what students know or do not know yet, and helps to determine which steps should be taken for future teaching and learning. The process of formative assessment can therefore be seen as ‘a cyclical programme of high and low-stake tasks in which students are actively involved (as assessee and/or assessor)’ (Leenknecht et al. Citation2021, 237), in order to provide opportunities to apply the obtained insights for future teaching and learning.

Several authors underline the cyclical nature of formative assessment and its subdivision in several iterative, consecutive phases (e.g. Ruiz-Primo and Furtak Citation2007; Antoniou and James Citation2014). In most cyclical programmes, eliciting students’ responses and interpreting those responses in relation to the learning objectives plays a central role. For example, Antoniou and James (Citation2014) emphasise the importance of sharing the learning objectives with students at the start of a formative assessment task. At the end of the task, the achievement information gained from the task can be used by the teacher through providing feedback and regulating learning by providing instruction or help.

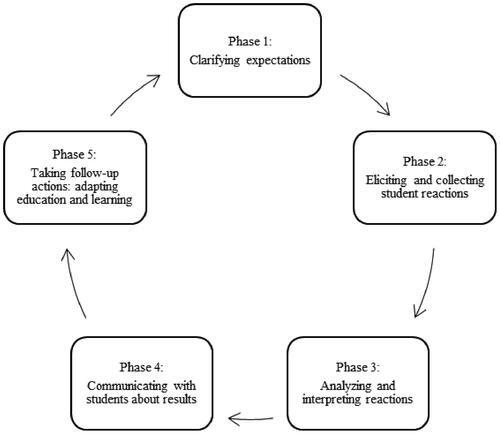

Gulikers and Baartman (Citation2017) reviewed several formative assessment programmes aimed at developing a more generic formative assessment cycle (see ). This generic cycle consists of five phases, in which both students and teachers are actively involved. In the first phase, the expectations (e.g. the learning goals) should be stated and discussed. In the second phase, information is gathered on where students stand with respect to accomplishing those learning goals. In phase three, the gathered information is analysed to verify whether it is sufficient to gain insight into what the student has already accomplished and where there is room for improvement. The fourth phase focuses on providing adaptive feedback and discussing this with the student. The fifth phase is about adjusting teaching behaviour in order to properly adapt it to the needs of the student, but also about adjusting student learning behaviour so it fits better with the demands of the learning tasks.

Figure 1. The formative assessment cycle (Gulikers and Baartman Citation2017).

Whereas in the model of Antoniou and James (Citation2014) providing feedback and teaching adaptively are presented as one-or-the-other options, Gulikers and Baartman (Citation2017) explicitly combine both options in their generic formative assessment cycle. With phase five of the cycle, Gulikers and Baartman place formative assessment in a broader educational context. According to Boud et al. (Citation2018), this is exactly what is needed to stimulate students’ active involvement in and responsibility for their learning. Far too often, the consequences of assessment for teaching and learning are not considered beyond the act of assessment itself (Winstone and Boud Citation2020). For example, feedback is not transferred to new tasks, or only the instruction of the formative task is adjusted and not the instruction of successive tasks.

Embedding formative assessment in teaching with help of scaffolding

Gulikers and Baartman (Citation2017) indicated that teaching in an adaptive manner is the most difficult phase of the formative assessment cycle for teachers to implement. Most of the reviewed studies reported a lack of follow-up actions and teacher adaptivity, or only stated that teachers implement follow-up actions but not how they do this (e.g. Suurtamm, Koch, and Arden Citation2010). Teachers’ intentions to implement formative assessment are predicted by several factors. These factors can be contextual factors in the classroom or school environment, but also personal factors like self-efficacy (Sach Citation2015; Yan and Cheng Citation2015; Schütze et al. Citation2017). This self-efficacy can be supported by formal training (Schütze et al. Citation2017). Unfortunately, current professional development programmes and pre-service education initiatives on formative assessment are often not a remedy for teachers’ feelings of insecurity (Gearhart and Osmundson Citation2009; Buck et al. Citation2010). While teachers are looking for practical examples of and guidelines for formative assessment programmes (Box, Skoog, and Dabbs Citation2015), the examples in the literature on how to take evidence-based follow-up actions appear to be very scarce (Forbes, Sabel, and Biggers Citation2015).

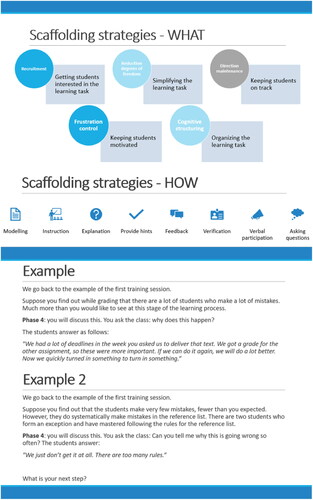

Where the literature on formative assessment seems to fall short, inspiration can be drawn from the literature on scaffolding. Scaffolding and formative assessment theories appear to be closely related (Shepard Citation2005) but not well integrated (Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2012). Scaffolding is a form of teacher support to help students in reaching their potential performance level (Van de Pol et al. Citation2014). Both scaffolding and formative assessment stress the importance of active interaction between students and teachers. In contrast to formative assessment, the scaffolding literature does provide concrete suggestions for teachers on how to exhibit adaptive teaching behaviour. That is, it offers a more thorough description of and practical guidelines for adaptive teaching behaviour by describing several scaffolding strategies (e.g. Silliman et al. Citation2000; Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2010). These strategies can provide the practical examples and guidelines teachers need for adjusting their teaching behaviour and provide valuable improvement for current formative assessment training programmes. In the strategies, a distinction is made between what should be scaffolded (i.e. intention) and how the scaffolding should take place (i.e. means). Through distinguishing between means and intentions in a scaffolding strategy, the rationale for a specific type of adaptive teaching behaviour can be substantiated and reflected upon. In the literature on scaffolding (e.g. Many Citation2002; Silliman et al. Citation2000; Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2010) five scaffolding intentions are identified:

recruitment (getting students interested in the task);

reduction of the degrees of freedom (simplifying the task);

direction maintenance (keeping the learner on track to their specific target);

contingency management/frustration control (rewarding and punishing for student performance and keeping students motivated); and

student performance and keeping students motivated); and

cognitive structuring (providing explanations to organise a learning task).

To support these scaffolding intentions, a teacher can use different scaffolding means. These means can be diverse, e.g. modelling (showing how to do something), instruction (on what to do), explaining (how to do a task in more detail), providing hints (explaining only parts of the task), providing feedback (suggestions for improvement), verification (clarifying or confirming information of the student), verbal participation (i.e. having a student interact in a discussion), and asking a student questions (Pata, Lehtinen, and Sarapuu Citation2006; Postholm Citation2006; Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2010).

Although the identification of intentions and use of means may be helpful for teachers, this usefulness strongly depends on the teacher’s capability to align the scaffolding strategy properly with a student’s current achievement level (Wittwer and Renkl Citation2008; Van de Pol et al. Citation2014). To use scaffolding strategies effectively, it is therefore important for teachers to be aware of their students’ current mastery level. For teachers to achieve this awareness and increase their adaptive classroom behaviour, it is not only important for them to make use of scaffolding strategies but also to make use of all phases of the generic formative assessment cycle.

Research aim

To address teachers’ experienced difficulties when exhibiting adaptive behaviour in their classroom, a teacher training - based on literature on formative assessment and scaffolding - was developed and implemented. In the training, teachers followed the phases of the generic formative assessment cycle and concrete suggestions were provided in phase five to support teachers in exhibiting their scaffolding intentions and associated means in their classrooms. The research aim was twofold, examining the effectiveness of the training in terms of: a) students’ perceptions of their teachers’ (non-) adaptive behaviour and b) teachers’ perceived usefulness of the training.

Prior research on scaffolding has shown that teachers who apply scaffolding strategies are perceived as more adaptive compared to teachers that do not make use of these strategies (Van de Pol et al. Citation2021). Since the training aimed to support teachers to communicate learning objectives, elicit and interpret students’ ideas, provide feedback on those ideas, and consequently adapt their teaching behaviour based on the previous steps, we hypothesised the training would have a positive effect on students’ perceptions of adaptive teacher behaviour (Hypothesis 1). It was also expected that the training with a special focus on scaffolding strategies would provide concrete guidelines. The lack of these guidelines made teachers experience difficulties with applying formative assessment strategies and exhibiting adaptive teaching behaviour before the intervention (Box, Skoog, and Dabbs Citation2015, Heitink et al. Citation2016). It was thus hypothesised that the teachers would perceive the training as useful (Hypothesis 2).

Method

Design

A quasi-experimental pre- post-test design was utilised to examine the perceived usefulness of the training. Teachers and students from two Dutch universities of applied sciences participated in the study. Eight teachers received the training (training group) and eight did not (non-training group). Within each university, allocation to the groups took place based on a representative distribution between groups and teachers’ availability during the fixed training timeslots. The training sessions were organised separately per university, but all associated teachers took part simultaneously within their own university so they could learn from the joint discussions and each other’s experiences. Student perception data regarding their teachers’ exhibited (non-) adaptive behaviour was measured within both groups 2 weeks before the first training session (i.e. pre-test) and 2 weeks after the second training session (i.e. post-test). Teachers’ perceived usefulness of the training was examined through semi-structured interviews within 2 weeks after they completed the training. Teachers in the non-training group received the training after data collection was completed.

Participants

In total, 16 teachers (six female and 10 male), from two Dutch universities of applied sciences voluntarily participated in this study. The subject matter taught by the teachers varied over different kinds of domains, such as maritime technology and social work. The teachers were able to sign up for the training programme through the university website.

Teachers were allocated to either the training (four teachers from each university) or the non-training group (two and six teachers from respectively university 1 and 2). For each teacher, students from one specific class participated in the study. Class sizes were relatively small, averaging around 20 students. In total, 260 students (about 80%) provided data regarding the perceived adaptive teaching behaviour. The training group consisted of 128 students (Mage = 22 years, age range: 17-51 years, including 48 female students), and 132 students were part of the non-training group (Mage = 23 years, age range: 17-55 years, including 40 female students).

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the first and third authors’ organisation. All teachers and students were informed about the research (data collection, data processing, data storage and reporting). They were ensured that the participation was voluntary and all data would be treated confidentially. All participants provided active consent.

Materials

Training programme

The first (university teacher) and second author (advisor and researcher at a university of applied sciences) developed and implemented the training programme. Both have expertise in formative assessment and are well connected in the field of higher education. The goal of the training programme was twofold, namely: a) getting a more thorough understanding of the generic formative assessment cycle and b) implementing the scaffolding strategies (phase 5: adjusting education) in classrooms. This might remedy teachers’: a) knowledge gap about formative assessment (e.g. Robinson et al. Citation2014) and b) experienced difficulties with transferring their knowledge to educational practices (e.g. Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2010; Gulikers and Baartman Citation2017).

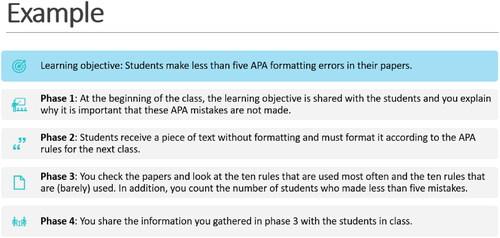

The training programme consisted of two sessions of 90 min and was provided in Dutch. Session one focussed on increasing teachers’ insight into the whole generic formative assessment cycle. It is important that teachers grasp the overall meaning of the cycle and familiarise themselves with the first phases before they start with the actual adjustment of their teaching behaviour. During the first session, we used several online materials from the Dutch national platform ‘Learning from Assessments’ (https://www.lerenvantoetsen.nl/toolkit-formatief-toetsen). For example, the teachers filled in a scan of their formative assessment activities used in class. They received an example of a possible class situation and descriptions of actions a teacher could take during the first three phases of the formative assessment cycle (see ). At the end of the session, teachers got the assignment to practice using the first three phases in the classroom they selected to participate in this study. By doing so the teachers were expected to gain more insight into the specifics of and the interplay between the different phases. To make sure their ideas were as concrete as possible, they filled in their personal ‘action plan’ stating what they were planning on doing, how they wanted to do this, and when.

The second session focussed specifically on how scaffolding strategies could be implemented in teachers’ daily practices (phase five formative assessment cycle). First, the theory on using scaffolding intentions and means was explained. After this, the example from the first session was repeated to practice the implementation of the explained theory. The trainers provided an example of a student’s response, upon which teachers were asked to determine a suitable next step with the use of scaffolding intentions and means (see ). Next, the teachers used what they had learned to determine what direction the next lesson of the teachers should take. Again, they wrote down an action plan to make sure ideas were as concrete as possible. Teachers were asked to implement their ideas in class after the second session. Upon request, the training materials can be made available by the first author.

Perceived Adaptivity Questionnaire

To examine the usefulness of the training programme, data about how students perceived their teachers’ adaptive teaching behaviour was collected. An adapted version of the Perceived Adaptivity Questionnaire (PAQ; Van de Pol et al. Citation2021) was administered to students participating in the training and non-training groups. Since the PAQ was originally developed for secondary education students, small adjustments were made to increase suitability for the higher education context. The focus on individual tasks was changed to a focus on group work through the use of ‘we’ instead of ‘I’. The questionnaire was translated to English for international students and the Dutch word for a secondary education student (leerling) was changed to university student (student).

The PAQ consisted of 27 items that were targeted at measuring teachers’ adaptive as well as non-adaptive behaviour. Similar to Van de Pol et al. (Citation2021), we used six subscales to distinguish between the type of (non-)adaptive behaviour a teacher can show (see ). The questions were formulated in terms of how teachers regulated student learning based on the diagnosis of their current mastery level of the subject matter (i.e. providing more or less content-related support or challenging tasks). shows six example questions, one for each subscale. A five-point Likert-scale from (1) incorrect to (5) correct was used for answering the 27 questions.

Table 1. Constructs measured with the Perceived Adaptivity Questionnaire.

To examine whether construct validity could be ensured we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using R’s Lavaan package (version 3.6.2, see R Core Team Citation2013). shows the fit statistics for a one, two (i.e. adaptive versus non-adaptive) and six-factor model. Since the six-factor model revealed the best fit and moderate fit indices (Hu and Bentler Citation1999) for both pre-test and post-test measurements we decided to continue with six scales.

Table 2. Goodness-of-fit indicators of models for perceived adaptivity (n = 173).

The internal consistency of the six scales was examined with R’s CTT package. Since the commonly used Cronbach’s alpha has several disadvantages (e.g. no internal structure measure, underestimation of reliability; see Sijtsma Citation2009) the suggestion to use the Omega coefficient made by others (e.g. Cho and Kim Citation2015; Deng and Chan Citation2017) was followed. The obtained coefficients ranged between .85 and .95, which can be qualified as very good when making statements about individual persons (Oosterwijk, van der Ark, and Sijtsma Citation2019).

Interviews

The first author conducted semi-structured interviews with six teachers who participated in the training group (four teachers from university 1, and two teachers from university 2). The teachers were asked to openly reflect on the usefulness of the training. Since the aim was to close the knowledge gap on formative assessment (Robinson et al. Citation2014) and address the need for practical examples (Box, Skoog, and Dabbs Citation2015), more specific questions followed about the:

content (both positive and negative, e.g. ‘What elements of the training programme did you consider as valuable?’);

practicality of the training (both positive and negative, e.g. ‘What elements of the training programme did not help you in your practice towards becoming more adaptive?’).

Analysis

To test Hypothesis 1, a repeated measures MANOVA was run in SPSS (version 25) with the six adaptivity scales as six separate dependent variables, time as the within-subjects factor (pre- and post-test) and group as the between-subjects factor (training versus non-training). Pre-test and post-test scores from 173 of the 260 participating students (n = 80 non-training group; n = 93 training group) were analysed, since only these students provided all the required questionnaire data. The results from the interviews were used to test Hypothesis 2. All data from the interviews were first summarised. These summaries were member-checked with the participants for approval; based on the check no further adjustments were made. After this check, the data was segmented and coded, based on the five main topics, by the first author.

Results

Hypothesis 1: perceived adaptive teaching behaviour

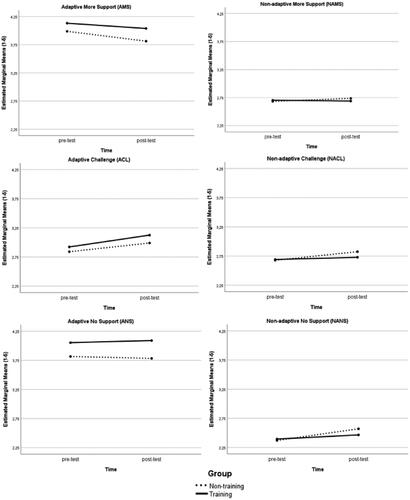

The average perceived adaptivity scores (means and standard deviations) are presented per group in . At first glance, the descriptive statistics show several variations in adaptivity scores over time and between groups. Specific increases and decreases in adaptive (e.g. more support, challenge), as well as non-adaptive teaching behaviour (e.g. challenge, no support), are displayed.

Table 3. Average adaptivity pre-test and post-test scores for the non-training, training group, and total (n = 173).

The results of the repeated measures analyses indicated several statistically significant differences over time (F (6, 166) = 4.71, Pillai’s Trace = 0.15, p < .001, partial η2 = .15) and between groups (F (6, 166) = 3.10, Pillai’s Trace = 0.10, p = .007, partial η2 = .10). No significant interaction effects between the two groups over time were found for any of the adaptivity scales (F (6, 166) = .45, Pillai’s Trace = 0.02, p = .842, partial η2 = .02). The main differences over time and between groups are summarised per adaptivity scale in .

Table 4. MANOVA results over time and across groups (n = 173).

When zooming in on the effects over time, the results indicate that - regardless of group - there were statistically significant differences between the pre-test and post-test scores for four of the adaptivity scales (see and ). Students reported that teachers improved (2.88 to 3.06) their ability to give more challenge to students when this is needed (adaptive behaviour). The results on the other three scales with significant time-effects indicate a decrease in perceived adaptivity. Students reported less adaptivity of their teacher in providing more support, meaning that students reported a decrease from pre-test (4.06) to post-test (3.93) in teachers’ ability to give more support when support is needed. On the non-adaptive scales, students reported an increase (2.68 to 2.78) in their teachers’ tendency to provide more challenge when this is not needed and an increase (2.38 to 2.52) in teachers’ tendency to provide no support when support is actually needed.

When zooming in on the effects between groups, statistically significant differences were found between the non-training and training groups for teachers’ adaptive behaviour. Students in the training group reported higher scores on teachers’ provision of more support when this is needed (4.08), and no support when students do not need the support (4.07), than students in the control group (3.90 and 3.80 respectively; see and ). These results indicate that, according to the students, teachers in the training group were showing more adaptive behaviour than the teachers in the non-training group. Since there is no interaction effect, the found difference in adaptive behaviour cannot be attributed to the training programme.

shows the profile plots of all six scales, illustrating the change in adaptivity scores for both groups separately. The plots show that students in the training group reported higher adaptivity scores for their teachers compared to the non-training group, consistent with the group effects found. When looking at the differences between the groups over time, the plots show that the differences between the adaptivity scores of the training and non-training group increase slightly from pre-test to post-test (albeit not statistically significant). Compared to the training group, teachers in the non-training group showed a smaller increase of adaptive behaviour over time on the challenge scale and a (bigger) decrease of adaptive behaviour on the no support and more support scales. For the scales that showed non-adaptive behaviour, teachers in the non-training group showed a slight increase in non-adaptive behaviour across all three scales. These results are robust across all adaptivity scales (i.e. perceptions in the non-training group develop less positively), indicating that the time differences found are mostly due to changes in perceptions of students in the non-training group.

Hypothesis 2: teachers’ experiences

Teachers generally reported being positive about the training programme. They perceived it as ‘useful’ (Teacher 2), ‘interesting’ (Teacher 6) and ‘an eye-opener’ (Teacher 1). The teachers concretised this during the interviews in relation to their practice:

It was useful because you get an awareness of the existence of those different phases. You also start checking: what do you do when the goal of your lesson is not reached? You measure during the lesson and adjust accordingly. (Teacher 2)

Immediately after the first training session, I saw leads for the lesson I had the next day... To say that I can now apply this universally in all types of lessons? No, but the awareness of what is behind all this - the didactics - do help me. I also saw an effect. (Teacher 3)

Teachers 1, 3, 4 and five also reported that the theory on scaffolding was a valuable addition to the training programme. Teacher 4 said: ‘I found the second part on scaffolding to be much more practical, I liked that. In a number of areas it made things more concrete, despite the fact that it was very short’. Teachers reported that the theory on scaffolding could help them in becoming more adaptive: ‘You start asking questions as to why someone is not keeping up’ (Teacher 3).

Even though the general tone about scaffolding and its use is positive, almost all of the teachers mentioned that they had not yet applied what they had learned in the second part of the training programme: ‘I have not really done anything with scaffolding yet’ (Teacher 5). Mostly this had to do with time and planning. After the first part of the training programme, teachers were left with the explicit task of putting to practice what they had learned. After the second part this was also the case, but there was no formal gathering to check and discuss the results. This resulted in teachers who got caught back up in the issues of the day:

It still seems like quite the puzzle to put this in your lesson plan. I notice now that we are too busy for this. For next years’ course, there is a new chance to look at it from that perspective. (Teacher 5)

Almost all teachers responded to these implementation problems by suggesting the addition of one extra part to the current two-part training programme: ‘In that regard, you should actually have at least three parts, in which you also apply what you say in the second part and then provide feedback and evaluation. That is important because it is the most difficult part’ (Teacher 3). Another one said: ‘The advantage of having three moments is that you have the third moment to reflect together instead of alone. Then you do not have to organise it yourself but you can still take a moment to do that’ (Teacher 5). Teacher 4 mentioned that more time and steps were needed to routinise what was learned: ‘I do not benefit from one bucket at the time, I benefit from one decilitre at the time’.

Some teachers recognise the problem that time is scarce and a longer training programme does not solve everything: ‘If we want to do something with this we also have to figure out for ourselves how to continue the work. We should not leave it here’ (Teacher 1). Besides this, the timing of the training programme was not always ideal. Some teachers only saw their class once during the entire programme, which meant they were not able to apply a lot of what they had learned in class: ‘For us, this programme would have fitted better if it came two weeks later or four weeks sooner’ (Teacher 4).

Discussion

This study aimed to support teachers in overcoming the difficulties in the formative assessment cycle when formulating and applying adequate follow-up actions based on students’ responses (e.g. Suurtamm, Koch, and Arden Citation2010; Schildkamp et al. Citation2020). In the training programme we designed, we incorporated scaffolding literature to provide teachers with the practical guidelines they are looking for (Box, Skoog, and Dabbs Citation2015). Interview data support the usefulness of scaffolding literature for this purpose: teachers valued the training programme and theory and guidelines from scaffolding literature. Teachers mentioned that the insights gained from scaffolding literature supported them in working on their adaptive teaching behaviour. While examples of concrete follow-up actions are rarely described in formative assessment literature (Forbes, Sabel, and Biggers Citation2015), scaffolding literature seems to provide useful insights by distinguishing scaffolding intentions and means (Many Citation2002; Silliman et al. Citation2000; Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2010).

Despite teachers’ positive reactions to the training programme, we did not find statistically significant effects of the training on students’ perceptions of their teachers’ adaptivity. No interaction effects between time and group were found. Results between the training and non-training groups indicated that teachers who did not take part in the training programme were perceived as less adaptive than teachers who received training (in providing more support when needed and withdrawing support when possible). Teachers’ perceived adaptivity in both groups generally seemed to decrease over time (with three of the adaptivity scales indicating less adaptive behaviour and one scale indicating more adaptive behaviour). Students of the untrained teachers reported a bigger but non-significant decrease in adaptivity compared to students of the trained teachers.

The reported decreases in teacher adaptivity for both the training and non-training groups could be explained by the presence of response-shift bias (Howard Citation1980). Drennan and Hyde (Citation2008) argue that a pre-test post-test design might lead to an underreporting of any change that occurs since students’ perceptions of the construct have changed. The presence of this bias would mean that students’ perceived teacher adaptivity in the post-test deviated from the pre-test because of the knowledge these students gained about the construct measured. Therefore students might have evaluated their teachers’ adaptive behaviour more critically in the post-test, explaining the decrease in reported adaptive teaching behaviour.

Another possible explanation is that students have not recognised the changes in their teacher’s teaching approach. In case teachers (slightly) adjusted their adaptive teaching behaviour, this adjustment might not have been clear or sufficient enough for the students to change their perceptions. This explanation aligns with the findings of Schütze et al. (Citation2017), who used a questionnaire to capture the changes in teachers’ behaviours in the context of feedback training. They concluded that questionnaires might not be sensitive enough to capture (small) behavioural changes.

Implementing scaffolding strategies

Teachers valued the training programme and expressed the intention to adopt a more adaptive teaching approach in the near future. Previous research reported teachers’ feelings of insecurity regarding formative assessment (Gearhart and Osmundson Citation2009; Buck et al. Citation2010), which influences teachers’ intentions to implement formative assessment strategies in practice (Yan and Cheng Citation2015). In our study, teachers conveyed confidence in their ability to implement the newly taught scaffolding strategies in practice, indicating a high level of self-efficacy. These findings confirm findings of previous studies, which state that teachers’ intentions as well as their confidence or self-efficacy to implement formative assessment can be supported by formal training (e.g. Schütze et al. Citation2017).

Despite teachers’ reported confidence regarding the use of scaffolding strategies, some contextual barriers for implementation remained. In our study teachers voluntarily applied for the training programme but were not able to spend a lot of time on their professional development, since time spent on other teaching tasks could not be reduced. This may have prevented them from turning intentions into action. Contextual factors play an important role in the implementation of formative assessment strategies in class (Yan and Cheng Citation2015). Yan et al. (Citation2021) conducted a systematic review on factors that affect teachers’ intentions and implementation of formative assessment. They mention the importance of a positive school environment, strong internal school support, supportive working conditions and encouraging external policies. Although the universities did encourage teachers to take part in the training program, the working conditions did not seem to provide teachers with enough time to change their teaching practice.

In line with previous research (e.g. Sach Citation2015; Yan and Cheng Citation2015), we conclude that teacher attendance in a training programme does not necessarily lead to changes in practice that are observable to students. Although the programme did seem to increase teachers’ self-efficacy regarding the implementation of formative assessment practices, contextual factors played an important role in the practical implementation of these practices.

Limitations and suggestions for improvement

When generalising this study’s results to future research and educational practice, it is advisable to take its limitations into mind. First, our study focussed on two universities of applied sciences in the Netherlands and relied on the voluntary participation of teachers. Although voluntary participation in this study had the advantage of attracting teachers who had some affinity and experience with formative assessment practices, the participating teachers are not a representative reflection of the whole university staff. The specific context and small sample of this study should be taken into account when generalising the findings to other contexts.

Second, we used students’ perceptions to measure teacher adaptivity. Student evaluations are commonly used in teacher education and professionalisation practices (e.g. Wubbels et al. Citation2012; Van der Lans, van de Grift, and van Veen Citation2015) but are also criticised. For example, the psychometric quality of student evaluation instruments is a topic of debate (Wolbring and Treischl Citation2015; Goos and Salomons Citation2017). The main point of criticism is that students’ perceptions of their teacher may reflect more aspects (e.g. personal traits, attractiveness, gender) than solely their perception of teaching behaviour (or a specific aspect of it). To, at least partly, account for any confounding factors we took several measures. First, the PAQ contains questions that focus mainly on observable behaviour instead of opinions or feelings (see also ). With the use of a Likert scale, the measurement was based on a relative (i.e. 1 = incorrect to 5 = correct) instead of an absolute (i.e. agree/disagree) measure for which the effect of a potential bias may be less severe. The CFA for the pre-test and post-test resulted in the same factor structure, so if any confounding factors were measured this affected both tests similarly and, therefore, had a minor impact on the time-related comparisons within and between groups. Last, we collected two types of data (student perceptions and teacher interviews) to gather insights on the effectiveness of the training programme. Since the findings of both sources complement each other (interviews: teachers could not yet fully apply what they learned; questionnaire: minimal changes in teaching behaviour) it seems that confounding factors only played a minor role. To get an even better picture, we recommend using additional data about teaching behaviour in future research. For example, lesson observations appear to provide reliable results for measuring teaching strategies (Van de Grift, 2014). By using more data sources, more insight into teaching behaviour can be provided and used to place the results into a broader perspective.

Third, teachers indicated the need to discuss their ideas on formative assessment strategies after the second training session. The training programme did not provide a possibility for this. In the development of the training programme, we actively intended to find a balance between effectivity and efficiency, keeping the programme as short as possible but still useful. Teachers indicated they liked the duration of the programme, but also noted that more time needs to be devoted to the implementation of phase five of the formative assessment cycle. To this end, they suggested adding a third session in which teachers can further reflect and act upon their application of adaptive teaching based on the insights from the second session. Since the activities in this fifth phase are vital for exhibiting more adaptive teaching behaviour (Gulikers and Baartman Citation2017), we recommend extending the programme with an additional session. To establish whether this additional investment beneficially affects students’ perception of the adaptive teaching behaviour we also recommend conducting a post-test survey a few months after the training programme to better understand the long-term effects of the programme.

Implications for research and educational practice

This study combined formative assessment and scaffolding literature with the purpose to support teachers in implementing formative assessment programmes in their classrooms. By doing so, it aimed at providing suggestions for advancing the theoretical development as well as the quality of teacher training programmes. Based on our results, it seems feasible to further act upon the suggestion provided by others (Shepard Citation2005; Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2012) to combine the literature from both fields. The scaffolding literature provides the concrete guidelines (i.e. interventions and means) that are lacking in the formative assessment literature (Heitink et al. Citation2016; Gulikers and Baartman Citation2017). Since the trained teachers generally valued the training it seems fruitful to develop and implement training programmes that combine the best of both worlds.

Research on formative assessment practices could benefit from measuring adaptive as well as non-adaptive teaching behaviour to gather more insight into the possible (in)effectiveness of formative assessment strategies. The gathered data can also help teachers to gain more insight into their specific strengths and areas for improvement regarding the application of phase five of the formative assessment cycle. The theoretical background and practical use of the PAQ might offer a valuable starting point for gathering this data.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that using scaffolding strategies has the potential to further concretise applying formative assessment strategies in practice. While in cyclical models of formative assessment (e.g. Ruiz-Primo and Furtak Citation2007; Gulikers and Baartman Citation2017) taking follow-up actions is considered a crucial final step, scaffolding literature provides practical insights in how to take those effective follow-up actions (Silliman et al. Citation2000; Van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen Citation2010). Although more research is needed, considering scaffolding intentions and means can provide the concrete starting point teachers need to focus and steer follow-up actions in education, completing the formative assessment process.

Notes on contributors

Stephanie M. A. Kruiper (MSc) is a teacher in Educational Science at the department of Education at Utrecht University. Her research interests concern formative assessment and feedback literacy, focusing on the application of research findings in teaching practice.

Martijn J. M. Leenknecht (PhD) is educational researcher and policy advisor at HZ University of Applied Sciences and coordinator of the Dutch National Platform Learning from Assessment. His current themes of research include motivational teaching approaches, formative assessment, and feedback seeking behaviour of students in higher education.

Bert Slof is an educational researcher and lecturer. He holds a PhD in educational sciences from Utrecht University. His research is aimed at studying the effects of methods (e.g., feedback and visualizations) fostering collaborative problem solving (task-related and interpersonal behavior) and the professionalization of (pre-service) teachers at their workplace. His specialties are: Problem-based learning, Computer Supported Collaborative Learning, External Representations, Instructional Design, Professional Development of Teachers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Antoniou, P., and M. James. 2014. “Developing a Framework of Actions and Strategies.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 26 (2): 153–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9188-4.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 2012. “Developing a Theory of Formative Assessment.” In Assessment and Learning, edited by J. Gardner, 2nd ed., 11–32. London: SAGE Publications. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 2018. “Classroom Assessment and Pedagogy.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 25 (6): 551–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2018.1441807.

- Boud, D., P. Dawson, M. Bearman, S. Bennett, G. Joughin, and E. Molloy. 2018. “Reframing Assessment Research: Through a Practice Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (7): 1107–1118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1202913.

- Box, C., G. Skoog, and J. M. Dabbs. 2015. “A Case Study of Teacher Personal Practice Assessment Theories and Complexities of Implementing Formative Assessment.” American Educational Research Journal 52 (5): 956–983. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831215587754.

- Buck, G. A., A. Trauth‐Nare, and J. Kaftan. 2010. “ Making Formative Assessment Discernable to Pre‐Service Teachers of Science.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 47 (4): 402–421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20344.

- Cho, E., and S. Kim. 2015. “Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha: Well Known but Poorly Understood.” Organizational Research Methods 18 (2): 207–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114555994.

- Deng, L., and W. Chan. 2017. “Testing the Difference between Reliability Coefficients Alfa and Omega.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 77 (2): 185–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164416658325.

- Drennan, J., and A. Hyde. 2008. “Controlling Response Shift Bias: The Use of the Retrospective Pre-Test Design in the Evaluation of a Master’s Programme.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 33 (6): 699–709. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930701773026.

- Forbes, C. T., J. L. Sabel, and M. Biggers. 2015. “Elementary Teachers’ Use of Formative Assessment to Support Students’ Learning about Interactions between the Hydrosphere and Geosphere.” Journal of Geoscience Education 63 (3): 210–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.5408/14-063.1.

- Gearhart, M., and E. Osmundson. 2009. “Assessment Portfolios as Opportunities for Teacher Learning.” Educational Assessment 14 (1): 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10627190902816108.

- Goos, M., and Salomons, A. (2017). Measuring teaching quality in higher education: Assessing selection bias in course evaluations. Research in Higher Education58: 341–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9429-8.

- Gulikers, J. T. M., and L. K. J. Baartman. 2017. Doelgericht professionaliseren. Formatieve toetspraktijken met effect! Wat doet de docent in de klas? (405-15-722). https://edepot.wur.nl/440065

- Heitink, M. C., F. M. van der Kleij, B. P. Veldkamp, K. Schildkamp, and W. B. Kippers. 2016. “A Systematic Review of Prerequisites for Implementing Assessment for Learning in Classroom Practice.” Educational Research Review 17: 50–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.002.

- Howard, G. 1980. “Response-Shift Bias: A Problem in Evaluating Interventions with Pre/Post Self Reports.” Evaluation Review 4 (1): 93–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X8000400105.

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Leenknecht, M., L. Wijnia, M. Köhlen, L. Fryer, R. Rikers, and S. Loyens. 2021. “Formative Assessment as Practice: The Role of Students’ Motivation.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (2): 236–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1765228.

- Many, J. E. 2002. “An Exhibition and Analysis of Verbal Tapestries: Understanding How Scaffolding Is Woven into the Fabric of Instructional Conversations.” Reading Research Quarterly 37 (4): 376–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.37.4.3.

- Oosterwijk, P. R., L. A. van der Ark, and K. Sijtsma. 2019. “Using Confidence Intervals for Assessing Reliability of Real Tests.” Assessment 26 (7): 1207–1216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191117737375.

- Pata, K., E. Lehtinen, and T. Sarapuu. 2006. “Inter-Relations of Tutor’s and Peers’ Scaffolding and Descision-Making Discourse Acts.” Instructional Science 34 (4): 313–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-005-3406-5.

- Postholm, M. B. 2006. “The Teacher’s Role When Pupils Work on Task Using ICT in Project Work.” Educational Research 48 (2): 155–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880600732256.

- Pryor, J., and B. Crossouard. 2008. “A Socio-Cultural Theorisation of Formative Assessment.” Oxford Review of Education 34 (1): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980701476386.

- R Core Team. 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Robinson, J., S. Myran, R. Strauss, and W. Reed. 2014. “The Impact of an Alternative Professional Development Model on Teacher Practices in Formative Assessment and Student Learning.” Teacher Development 18 (2): 141–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2014.900516.

- Ruiz-Primo, M. A., and E. M. Furtak. 2007. “Exploring Teachers’ Informal Formative Assessment Practices and Students’ Understanding in the Context of Scientific Inquiry.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 44 (1): 57–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20163.

- Sach, E. 2015. “An Exploration of Teachers’ Narratives: What Are the Facilitators and Constraints Which Promote or Inhibit ‘Good’ Formative Assessment Practices in Schools?” Education 43 (3): 3–13. .

- Schildkamp, K., F. M. Van der Kleij, M. C. Heitink, W. B. Kippers, and B. P. Veldkamp. 2020. “Formative Assessment: A Systematic Review of Critical Teacher Prerequisites for Classroom Practice.” International Journal of Educational Research 103: 101602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101602.

- Schütze, B., K. Rakoczy, E. Klieme, M. Besser, and D. Leiss. 2017. “Training Effects on Teachers’ Feedback Practice: The Mediating Function of Feedback Knowledge and the Moderating Role of Self-Efficacy.” ZDM 49 (3): 475–489. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0855-7.

- Shepard, L. 2005. “Linking Formative Assessment to Scaffolding.” Educational Leadership 63 (3): 66–70.

- Sijtsma, K. 2009. “On the Use, the Misuse, and the Very Limited Usefulness of Cronbach’s Alpha.” Psychometrika 74 (1): 107–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0.

- Silliman, E. R., R. Bahr, J. Beasman, and L. Wilkinson. 2000. “Scaffolds for Learning to Read in an Inclusion Classroom.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 31 (3): 265–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461.3103.265.

- Suurtamm, C., M. Koch, and A. Arden. 2010. “Teachers’ Assessment Practices in Mathematics: Classrooms in the Context of Reform.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 17 (4): 399–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2010.497469.

- Van de Grift, W. 2014. “Measuring Teaching Quality in Several European Countries.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 25 (3): 295–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2013.794845.

- Van der Lans, R., W. van de Grift, and K. van Veen. (2015). “Developing a Teacher Evaluation Instrument to Provide Formative Feedback using Student Ratings of Teaching Acts.” Educational Measurement 34 (3): 18–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12078.

- Van de Pol, J., N. de Vries, A. Poorthuis, and T. Mainhard. 2021. The Reliability and Validity of Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Adaptive Support during Seatwork: The Perceived Adaptivity Questionnaire [Manuscript in preparation]. Department of Education, Utrecht University.

- Van de Pol, J., M. Volman, and J. Beishuizen. 2010. “Scaffolding in Teacher-Student Interaction: A Decade of Research.” Educational Psychology Review 22 (3): 271–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9127-6.

- Van de Pol, J., M. Volman, and J. Beishuizen. 2012. “Promoting Teacher Scaffolding in Small-Group Work: A Contingency Perspective.” Teaching and Teacher Education 28 (2): 193–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.09.009.

- Van de Pol, J., M. Volman, F. Oort, and J. Beishuizen. 2014. “Teacher Scaffolding in Small-Group Work: An Intervention Study.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 23 (4): 600–650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2013.805300.

- Winstone, N. E., and D. Boud. 2020. “The Need to Disentangle Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687.

- Wittwer, J., and A. Renkl. 2008. “Why Instructional Explanations Often Do Not Work: A Framework for Understanding the Effectiveness of Instructional Explanations.” Educational Psychologist 43 (1): 49–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701756420.

- Wolbring, T., and E. Treischl. 2015. “Selection Bias in Students’ Evaluation of Teaching.” Research in Higher Education 57: 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9378-7.

- Wubbels, T., M. Brekelmans, P. J. den Brok, J. Levy, M. T. Mainhard, and J. W. F. van Tartwijk. 2012. “Let’s Make Things Better: Developments in Research on Interpersonal Relationships in Education.” In Interpersonal Relationships in Education: An Overview of Contemporary Research, edited by T. Wubbels, P. J. den Brok, J. W. F. van Tartwijk, and J Levy, 225–249, 256 p. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Yan, Z., and E. C. K. Cheng. 2015. “Primary Teachers’ Attitudes, Intentions and Practices Regarding Formative Assessment.” Teaching and Teacher Education45: 128–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.10.002.

- Yan, Z., Z. Li, E. Panadero, M. Yang, L. Yang, and H. Lao. 2021. “A Systematic Review on Factors Influencing Teachers’ Intentions and Implementations regarding Formative Assessment.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 1–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2021.1884042.