ABSTRACT

Assessment plays an important role in higher education, both guiding student learning and judging student success. However, assessment that treats all students the same is inequitable, since it ignores differences in students’ past and present circumstances. A shift to assessment for inclusion is advocated to promote student equity; one that incorporates diverse students’ perspectives on and experiences of assessment. A students-as-partners approach was taken to explore diverse students’ experiences of assessment, and their suggestions to make assessment more inclusive. A team of six staff and five student partners undertook a co-research project, facilitating workshops with 52 students from diverse backgrounds to understand their assessment experiences. While assessment goals varied, students reported assessment was an emotional experience, citing challenges with assessment design, process and broader university support. These findings can be aligned and incorporated within a previously developed assessment design framework, demonstrating that students can make nuanced judgements about the quality of assessment design in relation to inclusion. Future work on assessment design which seeks to be inclusive can and should therefore routinely involve students.

Introduction

Assessment is a crucial part of higher education. It is the basis upon which students are judged and guides their learning to that which is important (Boud Citation1995). Ideally, in an inclusive higher education system, assessment will afford all students equitable opportunities to succeed and demonstrate strengths relevant to their studies. Assessment that treats all students the same is by definition inequitable, because it ignores differences in students’ past and present circumstances. Despite ongoing research and efforts to promote equitable assessment processes, not all students have equitable assessment experiences (Leathwood Citation2005; Lawrie et al. Citation2017; Grimes et al. Citation2021; Tai, Ajjawi, and Umarova Citation2021).

The inclusion of diverse students in higher education has been supported through individual access plans which provide accommodations (also known as adjustments) for students with disabilities, especially in relation to assessment (Lawrie et al. Citation2017). This accommodations-based approach is problematic, given the massification of higher education and diversification of the student population (Koshy Citation2019), since it responds specifically to individuals’ circumstances with a narrow range of options that are not always effective (Kurth and Mellard Citation2006), and are also unlikely to be sustainable at scale. Students from non-traditional backgrounds (e.g. low-socioeconomic status background, regional location, studying at a distance) also do not graduate at the same rate, nor attain the same post-graduation benefits of employment as traditional students (Department of Education, Skills and Employment 2020; Tenorio-Rodríguez, González-Monteagudo, and Padilla-Carmona Citation2021). Focussing on particular equity groups can also neglect the multiple dimensions of student diversity, especially when these dimensions are not obvious or fall into particular categories of protected characteristics (Willems Citation2010; Grimes et al. Citation2019). Individual accommodations also frame the individual student as the problem, rather than seeking to understand what might be problematic about present assessment practices in higher education, and the ways in which they might unintentionally prevent certain students from progressing (Butcher et al. Citation2010).

Though there have been efforts to support assessment design in general, for example, the Assessment Design Decisions framework (Bearman et al. Citation2016), there is a pressing need for the sector to develop more inclusive assessment practices. In this paper, we provide an overview of the literature on inclusive assessment. Through a student partnership project, we describe equity students’ perceptions and experiences of assessment practices, and how they are or are not inclusive. Finally, we consider how these are similar to and different from contemporary assessment design principles.

Shifting from diversity to inclusion

In Australia, and many other countries, formal statistics about the diversity of student cohorts in higher education are routinely collected, yet limited to several broad, overarching categories: including students from low socioeconomic background, regional or rural, women in non-traditional areas, and/or Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (Department of Education, Skills and Employment 2020). Not only do these categorisations not cover the full spectrum of diversity (e.g. first in family: see O’Shea Citation2016), but many students have membership of multiple groups. A more nuanced understanding of how students’ intersectional identities impact their educational experiences is required to work against marginalisation (Crenshaw Citation1991; Willems Citation2010). While diversity may include characteristics such as disability, ethnicity, socio-economic status, gender, sexuality, previous education and/or location, this is not an exhaustive list.

Rather than considering student diversity, which often equates to blunt descriptions of characteristics at a population level, equity can be framed through the lens of inclusion. While notions of inclusion in education are broad-ranging, they relate to the involvement and participation of diverse student populations, to avoid stigmatisation of difference and ensuring a range of needs are covered (Stentiford and Koutsouris Citation2021). In the case of assessment, a more proactive approach to participation and success is required, rather than only being reactive to one group’s specific issues or concerns, which is likely to exclude others (Nieminen Citation2022; Tai, Ajjawi, Bearman, Boud, et al. Citation2022). Therefore, shifting to inclusion in assessment moves past responding to the needs of a single equity group, or a reactive stance where diversity is reduced to a narrow set of categories, to creating assessments that are accessible for a wide range of students.

Diverse students’ experiences of assessment

Much of the research to date on diverse students’ experiences of assessment has focussed on a specific group of students, leaving it difficult to holistically understand how practices could be inclusive across various student cohorts. A literature review from 2000 onwards found that of 13 papers which implemented an assessment that was intended to be more inclusive, six included students with disabilities, four included international students, two included linguistically diverse students, and one did not outline a particular grouping (Tai, Ajjawi, and Umarova Citation2021). While choice in assessment type was valued across these groups, students with disabilities reported difficulties in obtaining accommodations in their assessments (Stampoltzis et al. Citation2015; Majoko Citation2018). Students with learning differences and disabilities have reported that they require additional time to complete assessment tasks, especially during periods of significant workload which can be stressful and fatiguing (Fuller et al. Citation2004; Grimes et al. Citation2021; Tobbell et al. Citation2021). Students have also reported preferring a variety of assessment formats (e.g. multiple choice, written assignments, end of term examinations) according to their strengths and capabilities (Griful-Freixenet et al. Citation2017; Tobbell et al. Citation2021).

Even when accommodations are provided, these can result in students being treated differently. Shpigelman et al. (Citation2021) describe a student with multiple disabilities feeling shame about sitting his examination in a different location from the rest of his friends. Not wanting to be treated differently, and not wanting to be perceived as having any kind of advantage, are common reasons for students to not disclose their situation or condition, and therefore not receive any accommodations (Lightner et al. Citation2012; Grimes et al. Citation2019). However, students with and without disability can also face similar challenges in assessment (Madriaga et al. Citation2010): this may mean that changes which improve the inclusivity of assessment may benefit all students.

Mainstream assessment design has not explicitly focussed on inclusion as a key aspect (Bearman et al. Citation2016; Bryan and Clegg Citation2019), even though recommendations to improve the inclusivity of assessment have existed for many years. Guidance has centred around providing alternative tasks to examinations, ensuring appropriate accommodations, and ensuring that the assessment materials themselves are accessible to students (Waterfield and West Citation2006; Hockings Citation2010; Ketterlin-Geller, Johnstone, and Thurlow Citation2015). Studies which included students’ experiences and perspectives on assessment have predominantly focussed on disability (Waterfield and West Citation2006; Morris, Milton, and Goldstone Citation2019; O’Neill and Maguire Citation2019). Ensuring diverse students have equitable assessment experiences is important, since assessment must certify students’ achievements and serve as learning opportunities (Boud and Soler Citation2016). To make inclusive assessment part of business-as-usual assessment design rather than a niche concern, we contend that it is important to take a more holistic approach and consider a broader range of students’ assessment experiences.

In this paper, we seek to answer two research questions:

How do diverse students experience assessment?

What strategies could improve the inclusivity of assessment?

Methods

A students-as-partners approach to inclusion

Students as partners has been defined as a ‘collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualisation, decision-making, implementation, investigation, or analysis’ (Cook-Sather, Bovill, and Felten Citation2014, 6–7). Research in assessment and feedback has begun to advocate for students as partners as a way to mitigate inherent power imbalances and move towards more egalitarian assessment systems (Matthews et al. Citation2021; Nieminen Citation2022). However, projects seldom involve students as co-investigators, as we have done in this study.

To assemble the team of student and staff researchers, the lead researchers (JT & MD) sought co-researchers who had experience and interest in the topic. Staff researchers were approached who had expertise in assessment, learning design and/or inclusion. An advertisement for student co-researchers was placed on the university’s student jobs electronic noticeboard. Applicants were asked to provide a short statement about how their experiences and expertise as diverse students who have navigated assessment at the university could contribute to the project. Five student partners were then selected and employed as casual research assistants on the project. Student partners represented various diverse cohorts including neurodiverse, students with a chronic illness and first-in-family. Ethical approval was obtained for the project from Deakin University, reference HAE-21-104, and all researchers were named on the application.

Data collection procedure development

CoLabs are participatory design workshops that use scaffolded activities (e.g. storyboards, mind maps) to support problem solving and idea generation (Dollinger and Vanderlelie Citation2021). Student and staff co-researchers developed a set of workshop activities based on the research questions, which the student researchers felt that other students could contribute to meaningfully. The activities included asking students to express their feelings, experiences and goals with assessment so far, and asking students to design ways to support diverse students navigating university assessment. Two workshop protocols were developed to explore the research questions through different activities (). Students contributed individually to a shared online space before having a facilitated discussion about their responses.

Table 1. Student workshop activities.

Participants and data collection

CoLab participants were recruited through the university’s student-facing blog, which is used to communicate news and events to all students. The advertisement invited students from diverse backgrounds, with various experiences of assessment, to participate in a 60-minute workshop to share their perspectives and advice and provide feedback on their university assessments to improve future assessment processes.

A total of 82 students expressed interest and were invited to the workshops. Six CoLabs occurred over three weeks, with 52 students attending. While participants were not required to disclose their situation or condition in the recruitment process, most students responded to a question about their background characteristics. Workshop participant characteristics are outlined in to illustrate diversity rather than compare experiences across groups. Many additionally described their personal circumstances during the workshops to provide context to the discussion. Workshops were hosted online via Zoom, using Mentimeter word cloud and Padlet to support activities. In the workshops, student partners acted as facilitators of the activities, with three to four student participants in each breakout room, while staff supported the online software usage and took notes on information that was not captured through the software (e.g. verbal elaborations on students’ input into the activities). The workshops were not audio/video recorded to create a safe environment for participants to discuss their experiences.

Table 2. Workshop participants’ self-identification of diversity during recruitment.

Data analysis

Data from the online platforms were exported for analysis and included alongside the typed staff notes to form the dataset for the project. To establish a shared understanding of the coding process, all team members attended a coding meeting where one document was discussed and coded collaboratively. The research team then split up the remaining data, which was coded in pairs (one student partner and one staff member) to develop the initial themes. Team members then reviewed each other’s coded documents, and subsequently met together as a group to refine the major themes that were identified across the entire dataset. The themes were then arranged and refined in response to the research questions.

Findings

The student context

University classrooms are increasingly diverse environments, and students reported a range of expectations, goals and preferences in relation to assessment. We first contextualise diverse students’ experiences in assessment through describing their goals in assessment, and emotional responses to assessment.

Students have varying goals in assessment

When student participants were asked about their goals in completing assessment some spoke about their desired mark, while others judged success by the time it took to complete the assignment or whether it had informed their understanding of the topic. Others reflected on their personal circumstances: ‘mature age students – come back not to pass, but to prove something to ourselves’. Some students took a more strategic approach to their assessment goals; for example, one identified their grades as an intermediate goal towards further education: ‘I am aiming to do Masters, so I am aiming for…70%’.

Assessment is emotional

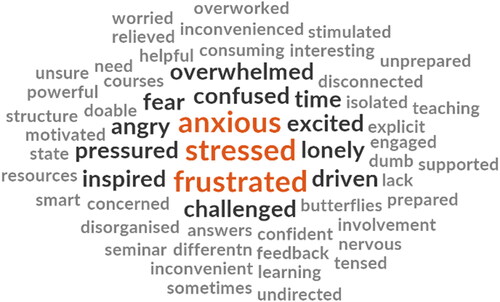

Accompanying these goals were a range of assessment-related emotions. For some assessment was exciting or motivating because it helped them to monitor their learning progress. For others, assessment could be an anxiety-ridden, stressful or frustrating ().

Figure 1. Word cloud of student responses to "How have assessments made you feel? What word comes to mind?".

Students elaborated that many of these feelings were compounded by factors such as the availability and accessibility of assessment information, and when multiple assessments were due at the same time. This was worsened for some by external factors outside of the university; for example, managing full time work, juggling several jobs, or having family care responsibilities contributed to the stress and pressure of completing assessments. COVID-19 also exacerbated negative emotions since changes in personal living situations and the transition to emergency online teaching disrupted how students could take part in assessment. Assessment design, assessment processes and the broader university support structures were all areas which students suggested could be improved.

Assessment design

Assessment could be more relevant to work and authentic situations

Students recognised that examinations are not always authentic or relevant to what they had learned or how performance is measured in the world outside of university. In particular, students recognised the potential for examination environments to disadvantage diverse students/equity cohorts, because they do not reflect realistic work environments or how they might perform in those. Some suggested that a ‘no examinations’ model would reduce stress and more accurately reflect their capabilities. Others suggested that take home or open book examinations were superior to traditional formats, preferring opportunities to demonstrate their understanding and application of what they had learnt, rather than just recalling facts.

‘A person’s exam performance can be compromised by extraneous elements which are not eligible for special consideration, such as fatigue, anxiety or illness (e.g. a cold); all these elements are mitigated through the adoption and implementation of flexible take-home exams.’

‘Take-home exams do a significantly better job of preparing students for the real world compared to in-person paper exams, nowhere in the real world will a person be shut away from information and be made to write down as much as they can recall’.

Beyond examinations, students suggested several ways in which assessment could better support diverse students to learn and demonstrate their capabilities. Students had divergent suggestions about the relative weighting and sequencing of assessments. While some students found that having one large task was easier as they could then focus on one thing and just get it done, others preferred smaller tasks with lower weightings because these helped them to apportion time across the trimester. In alignment with this, it was emphasised that marks should be proportionate to the workload required. Flexible choices – or even two different assessment options – were seen to be the best strategy to support this variation in preferences. This included choice over how and when to complete the assessment, and opportunity to select a particular focus or format. Students also suggested that assessment should be reduced where feasible; for example, some suggested that it is not necessary to assess the same learning outcome several times.

Opportunities for learning

Feedback was frequently the subject of strategies needing improvement. Many students wished they had ‘more ability to clarify feedback’ and emphasised that feedback should be specific rather than ambiguous and include suggestions for improvement. To be most effective, students pointed out that they needed the feedback process to occur prior to the submission of linked assessments, so they could implement the suggestions in their subsequent work. Examinations were also mentioned as a specific area where some information about performance could be provided: ‘You get your exam mark back and you go “okay? What did I do well? where can I improve?”’

Students reflected positively on opportunities to practice tasks aligned with their assessment. Some pointed out that assessment itself should be a learning opportunity, not just a testing opportunity, and noted that formative worksheets, practice quizzes, and exemplars could be made available to help them to prepare for assessment.

‘Unit where the professor gave two questions at the end of every class that were similar to the assignment questions, this allowed the teacher to guide the class to resources which were also relevant to the assignment, this gave the class more time to do research, instead of having to do it in a short assignment duration, allowed more time and focus on learning.’

Assessment processes

Students identified many avenues for the improvement of assessment processes. This included scheduling assessment tasks to avoid or reduce overlap, greater consistency in instructions, providing opportunities to practice tasks, and refining the logistics of feedback to ensure timeliness.

Assessment timing needs to support all students to complete tasks

Discussion relevant to this theme included releasing assessment guidelines early to maximise flexibility and students’ ability to plan, especially when multiple assessments are due at once. The specific due time and date was also seen to disadvantage students who had differing commitments.

‘The assessment deadline is often 8 pm. That doesn’t work for me, because I work in the afternoon.’

‘I definitely do like the ones where you have an extended window of time – e.g. a quiz opens for four days, a window rather than just due. It would still mean there is a deadline date.’

This was particularly important for students who had caring responsibilities, differing work schedules or fluctuating conditions which impacted their ability to consistently study, all of whom may use their time differently. Having information released in a drip-feed manner did not help students plan ahead, and assessments were often due close to each other, leading to difficulties in completing all tasks on time.

‘They should consider the time it takes to do an assessment. It can be very hard to have many assessments due at the same time from different classes.’

‘Hard to manage with work around and look after step kids. Hard when you can’t see them at the beginning and plan accordingly.’

‘Releasing all unit learning resources at the beginning of the unit will especially benefit Cloud [online] students, as well as students working full-time in addition to their studies.’

Assessment instructions and information need to be accessible, consistent and clear

Access to assessment instructions and information was important, as without clear and early access, there was a risk that students, especially those with differing time commitments, would not be able to complete assessment tasks to the best of their ability. Though all units used the online learning management system to organise assessment information, students appreciated a consistent approach to the presentation/organisation of these assessment resources. There was also reported inconsistency in instructions, criteria and/or rubrics that were intended to support assessment tasks. This was confusing to students.

‘Frustrated because there’s inconsistent instructions and rubrics, every [instruction] is different.’

‘You end up trying to collate seven sets of instructions which don’t always align… So lots of time spent/wasted working out what they want.’

To combat inconsistencies in information, students reported that discussion boards were promoted as the way to clarify questions about assessment, and that this was helpful. However, often this meant that many students were posting questions, and there was little ability to access the most relevant information quickly and easily. Reading through individual comments was seen as inefficient and some students reported difficulties with accessibility when they used a screen reader.

‘In one unit there is reliance on posting to the discussion board, but I am not able to do that with the technology I used. I was supposed to submit a discussion point by week four to pass that assessment, but had trouble getting in touch with the unit chair. Using images in unit and assessment resources can also be problematic. I understand why that is done, because people can be visual learners, but it would help to include alternative text so that it is explained to people who are visually impaired.’

While this was particularly significant for a student with visual impairment, other students with learning differences also reported difficulties in interpreting assessment instructions where they were only published in a single format. Students pointed out that inclusion and access might look different for different types of students, so this multiplicity needs to be catered for while maintaining consistency of information.

Students valued opportunities for clarification, especially where there was variability in instructions. They noted that some students might be less confident to ask questions of their lecturers directly, and some online subjects might have fewer opportunities for synchronous interaction/discussion sessions, so the scheduling and recording of question-and-answer sessions was important.

‘They often have a drop-in session 1 week before hand… Needs to happen earlier for direction and [then] one before for final things. Should be recorded so everyone has access to it.’

Assessment accommodations

Special consideration, or time extensions on assessments, were also a common point of discussion. Many students indicated that the process to receive extra time or other accommodations was challenging, with confusion over what documentation was required or timelines. Some students were hesitant to engage in processes even when they met the criteria for special consideration. They reported feeling ashamed or unworthy about needing accommodations in comparison to their peers, and were also unsure if their teachers would view them differently. More awareness of the need for and the straightforward implementation of accommodations was an important aspect for students with access plans.

‘I have a learning access plan so I am always a bit worried about the learning considerations I will get through Deakin and managing my health.’

Broader university support for diverse students

Equitable access to resources

Considering the bigger picture of assessment in context, students described the diverse circumstances that students experienced, and highlighted the need for free or low-cost resources (e.g. electronic textbooks, internet, computing equipment) so that all students could be supported to learn and participate in assessment in an equitable manner.

‘University textbooks are expensive, and university students are known to not possess a lot of money; such a policy would help reduce costs, thereby ensuring that cost is no burden to a quality education. A lot of assessments may be dependent on access to unit textbooks, and an inability to access them may severely disadvantage the students in question.’

In an assessment scenario which required a student to complete a compulsory full-time placement, student responses highlighted the need for bursaries or scholarships, and/or support to undertake the placement in a different configuration (e.g. over a longer period of time for fewer days a week, recognising a greater variety of placement sites) so that all students had the opportunity to complete the placement successfully.

‘Financial support – I work and live by myself (need to work or can’t live and pay my bills) there is no other support. [The university] needs to understand that when asking mature aged people (who have careers) there must be financial assistance and alternatives.’

Interactions between staff and students can support inclusion

Students also suggested broader strategies including information technology support, learning and language advisors, peer mentors, as well as speaking directly to course and placement co-ordinators about their circumstances. Regardless of role, it was important that staff were empathetic to the student’s situation. While many students suggested that the university services should reach out to particular groups of students to ensure they were aware of the help available, some also acknowledged that students should make use of those services:

‘In a perfect world, it would be great to contact everyone who drops off the radar but important for individuals to take responsibility. We are all adults. As long as services are available and advertised, then student also needs to utilise the services.’

Peer support was also seen as a possible way to improve inclusion around assessment. Students emphasised the importance of the social aspects of learning in the lead up to completing assessment tasks. This was particularly crucial for mental health and wellbeing.

‘Support from peers – all my units we have messenger groups and FB [Facebook] – we are all online we have to the option to communicate – really important to have the networking capacity.’

‘With the mentor/mentee relationships as well – they can be valuable – it’s not your unit chair, but you can still have that support from someone who is third or fourth year.’

However, in identifying peer support as an important aspect of inclusive assessment, students also identified the contradictions between supporting collaboration and the significant messages and cautioning around plagiarism. While students supported the need for academic integrity training, they also found that this stymied efforts to work together in group tasks, and supporting each other more generally in their assessment experiences, as they were worried that any interaction might be viewed as collusion. They also suggested that some students might not realise that it was possible to ask a lecturer or tutor for help in clarifying the assessment task: ‘It’s not cheating to want to know more about feedback and assessment’.

Discussion

The breadth of challenges and solutions that students shared, and their sometimes divergent or contradictory nature, illustrates that inclusive and accessible assessment is a complex challenge. A one-size-fits-all approach to assessment is unlikely to be successful (Tai, Ajjawi, Bearman, Dargusch, et al. Citation2022), and so holistic framing of equity in the classroom is important to supporting diverse cohorts. Students themselves acknowledged the need for variable approaches to assessment depending on student characteristics, capabilities and goals. Principles of Universal Design for Learning will no doubt help support equitable assessment and learning, and help to shift the responsibility from the student to staff (CAST. Citation2018). However, the transition to equitable assessment requires ongoing dialogue.

Many of our findings about the difficulties and challenges students experience in relation to assessment align with previous studies of equity group students, such as barriers to obtaining and the implementation of accommodations, and the emotional impact of assessment (Grimes et al. Citation2021; Tobbell et al. Citation2021). However, our study also identifies strategies that might improve assessment, both at a design level, and across broader university processes. Student contributions in this study likely represent only a sample of a longer list of challenges, and thus should be seen to be the beginning of a conversation rather than a definitive solution to inclusive assessment.

How can assessment design explicitly focus on inclusion, since it may be that inclusive assessment design bears a strong resemblance to good assessment design (Tai, Ajjawi, Bearman, Boud, et al. Citation2022)? Findings around the need to improve the clarity of instructions and criteria, the realistic nature of the task, and the need to take into account students’ abilities and align assessment tasks to support work readiness, are similar to those reported in a recent investigation of students’ preferences for assessment (Garvey, Hodgson, and Tighe Citation2022). This echoes older research which found that disabled and non-disabled students reported similar assessment challenges (Madriaga et al. Citation2010). The impacts of design, however, are likely to be greater in diverse students’ assessment experiences and success: indeed, diverse students have previously reported choosing or changing courses depending on the types of assessment they know they will encounter (Morris, Milton, and Goldstone Citation2019).

To understand the overlaps and dissonances between inclusive assessment and good assessment design, we compare our findings against an assessment design decision (ADD) framework (Bearman et al. Citation2016) in . The ADD framework was designed to support the assessment designer to consider what they should prioritise within their own context. We suggest the incorporation of diverse students’ nuanced perspectives on inclusive assessment can contribute to mainstreaming inclusion as an explicit consideration in assessment design in the following ways.

Table 3. Alignment of findings with the assessment design decisions framework.

When considering inclusion, it may be fruitful to focus on the contexts of assessment, since this is where learner characteristics are primarily considered. Students’ suggestions around choice and flexibility and realistic tasks mirror previous studies where students also favoured choice in assessment (O’Neill Citation2017; Morris, Milton, and Goldstone Citation2019; Jopp and Cohen Citation2020), albeit choice that was sufficiently bounded and aligned with intended learning outcomes. Resources traditionally considered beyond assessment (such as study materials, access to technology, financial support) should also be considered when designing assessment requirements.

Feedback processes could be a significant opportunity to improve inclusion for students who may not be as confident or familiar with expectations of university assessment tasks. While feedback is commonly linked to assessment, Winstone and Boud (Citation2022) argue that it may be beneficial to disentangle feedback from assessment to improve its impact, suggesting dissociating grades from qualitative comments, and providing for feedback opportunities earlier in the learning cycle. Considering students’ reported experiences, including the stress incurred from assessment tasks – especially where students find that, across the subjects they are studying, there are multiple assessments due at once – and the need to clarify or seek elaboration about feedback comments, an initial step would be to refine the feedback processes that already exist (both in timelines and opportunities for feedback dialogue) before implementing further opportunities such as the practice tasks that students suggested.

One finding outside the ADD framework was the unintended impacts of academic integrity education for diverse students. Educating students about plagiarism and other forms of cheating is a common strategy to promote academic integrity (Sefcik, Striepe, and Yorke Citation2020). However, in this study students reported this also prevented some students from seeking the help they are able to obtain from student study support services and academic staff. This may be more significant for students who have had little interaction with university culture previously; for example, students who are first in family to study at university, or international students who have previously experienced a different university culture and expectations. A closer relationship between orientation to specific assessment tasks and the introduction of academic integrity requirements may also contribute to inclusion.

Strengths and limitations

This work has several strengths: staff and students worked together to design a research method that would collect fit-for-purpose data around diverse students’ assessment experiences and strategies for making assessment more inclusive. The workshop design facilitated rich data collection from a wide range of student participants. Student partners on the project were able to draw on their expertise of being students, and staff researchers also brought expertise from a variety of backgrounds (assessment researchers, learning design, student partnership and disability practitioners), all of which helped to make sense of the data, which reinforces pre-existing advice regarding good assessment design. Given this study was conducted at a single (albeit large) university, with 52 workshop participants over six workshops, it may be possible that a larger study with refined workshop activities involving multiple universities may generate further insights. This project also demonstrates that students do make nuanced judgements about assessment and inclusion, and so can offer relevant advice if staff work with students as part of regular curriculum review. Further embedding students as partners approaches into the practice of assessment and feedback design may be key to understanding what modifications or new approaches could be embedded to have a significant impact on inclusion. How to adopt these processes within the resource-constrained environments of standard quality assurance cycles should be explored, since it is likely that wide-spread improvement may only be realised when inclusion is made to be part of business-as-usual (Tai, Ajjawi, Bearman, Dargusch, et al. Citation2022). We also only canvassed student perspectives on what inclusive assessment might look like: the views of academics, learning designers and accessibility staff are also likely to add further depth and nuance to our understanding of what inclusive assessment might be.

Conclusion

The student perspective is crucial in designing assessment for inclusion. Diverse students report significant challenges in participating in assessment, but also identify solutions relating to assessment design and process which are similar to those proposed in the assessment literature. Inclusion should be an explicit concern in assessment design to account for diverse student cohorts.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Merrin McCracken and the other team members who contributed to the design and execution of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributor

Joanna Tai is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE) at Deakin University. Her research interests include inclusive assessment practices, student experiences of learning and assessment from university to the workplace, peer learning, and developing capacity for evaluative judgement.

Mollie Dollinger is a Senior Lecturer in Deakin’s Learning Futures (DLF) team and a member at Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE). Her research explores student voice, student equity and inclusion, learning analytics, and work-integrated learning.

Rola Ajjawi is an Associate Professor in Educational Research at the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE) at Deakin University. Her programme of research has centred on work-integrated learning with an interest in inclusion, assessment, failure and persistence, and feedback in the workplace.

Trina Jorre de St Jorre is Student Experience Portfolio Manager at the University of New England, and holds an honorary appointment at the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE) at Deakin University. She is focused on strategies for enhancing student achievement and graduate employability. She is interested in the use of student perspectives and partnerships to improve curriculum design.

Shannon Ng Krattli is an international student undertaking Honours of Nutrition Science at Deakin University, Australia. Her research interests are biochemical metabolism and chronic diseases. She previously co-wrote a paper with Cancer Council Victoria that is to be published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.

Danni McCarthy is a Lecturer in Inclusive Education at Deakin University. She provides evidence-based leadership towards the development of inclusive education environments that are intentionally designed and capable of maximising the participation and achievement of all learners.

Daniella Prezioso is a student partner, studying Bachelor of Nutrition Science (Dietetics Pathway) at Deakin University, Australia, who also graduated from 2020 Deakin Accelerate Program in Disability, Diversity, and Inclusion with distinctions. She endeavours to advocate and create positive change within tertiary education systems, to facilitate equitable opportunities for diverse students.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bearman, M., P. Dawson, D. Boud, S. Bennett, M. Hall, and E. Molloy. 2016. “Support for Assessment Practice: Developing the Assessment Design Decisions Framework.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (5): 545–556. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1160217.

- Boud, D. 1995. “Assessment and Learning: Contradictory or Complementary?” In Assessment for Learning in Higher Education, edited by Peter Knight, 35–48. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203062074-8.

- Boud, D., and R. Soler. 2016. “Sustainable Assessment Revisited.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (3): 400–413. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133.

- Bryan, C., and K. Clegg, eds. 2019. Innovative Assessment in Higher Education. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. | “[First edition published by Routledge 2006]”—T.p. verso.: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429506857.

- Butcher, J., P. Sedgwick, L. Lazard, and J. Hey. 2010. “How Might Inclusive Approaches to Assessment Enhance Student Learning in HE?” Enhancing the Learner Experience in Higher Education 2 (1): 25. doi:10.14234/elehe.v2i1.14.

- CAST. 2018. “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2.” http://udlguidelines.cast.org.

- Cook-Sather, A. C. Bovill, and P. Felten. 2014. Engaging Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching: A Guide for Faculty. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1300. doi:10.2307/1229039.

- Department of Education Skills and Employment. 2020. “2019 Section 11 Equity Groups.” https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2019-section-11-equity-groups.

- Dollinger, M., and J. Vanderlelie. 2021. “Closing the Loop: Co-Designing with Students for Greater Market Orientation.” Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 31 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1080/08841241.2020.1757557.

- Fuller, M., M. Healey, A. Bradley, and T. Hall. 2004. “Barriers to Learning: A Systematic Study of the Experience of Disabled Students in One University.” Studies in Higher Education 29 (3): 303–318. doi:10.1080/03075070410001682592.

- Garvey, L., Y. Hodgson, and J. Tighe. 2022. “A Mixed Method Exploration of Student Perceptions of Assessment in Nursing and Biomedicine.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 46 (1): 128–141. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2021.1892608.

- Griful-Freixenet, J., K. Struyven, M. Verstichele, and C. Andries. 2017. “Higher Education Students with Disabilities Speaking Out: Perceived Barriers and Opportunities of the Universal Design for Learning Framework.” Disability & Society 32 (10): 1627–1649. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1365695.

- Grimes, S., E. Southgate, J. Scevak, and R. Buchanan. 2019. “University Student Perspectives on Institutional Non-Disclosure of Disability and Learning Challenges: Reasons for Staying Invisible.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (6): 639–655. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1442507.

- Grimes, S., E. Southgate, J. Scevak, and R. Buchanan. 2021. “Learning Impacts Reported by Students Living with Learning Challenges/Disability.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (6): 1146–1158. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1661986.

- Hockings, C. 2010. “Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: A Synthesis of Research.” EvidenceNet, Higher Education Academy. www.heacademy.ac.uk/evidencenet.

- Jopp, R., and J. Cohen. 2020. “Choose Your Own Assessment–Assessment Choice for Students in Online Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education: 1–18. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1742680.

- Ketterlin-Geller, L. R. C. J. Johnstone, and M. L. Thurlow. 2015. “Universal Design of Assessment.” In Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice. 2nd ed., edited by Sheryl Burgstahler, 163–175. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Koshy, P. 2019. Equity Student Participation in Australian Higher Education: 2013–2018. Perth: Curtin University. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NCSEHE-Equity-Student-Briefing-Note_2013-18_Accessible_Final_V2.pdf.

- Kurth, N., and D. Mellard. 2006. “Student Perceptions of the Accommodation Process in Postsecondary Education.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 19 (1): 71–84. http://ahead.org/publications/jped/vol_19.

- Lawrie, G., E. Marquis, E. Fuller, T. Newman, M. Qiu, M. Nomikoudis, F. Roelofs, and L. van Dam. 2017. “Moving towards Inclusive Learning and Teaching: A Synthesis of Recent Literature.” Teaching and Learning Inquiry 5 (1): 9–21. doi:10.20343/teachlearninqu.5.1.3.

- Leathwood, C. 2005. “Assessment Policy and Practice in Higher Education: Purpose, Standards and Equity.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (3): 307–324. doi:10.1080/02602930500063876.

- Lightner, K. L., D. Kipps-Vaughan, T. Schulte, and A. D. Trice. 2012. “Reasons University Students with a Learning Disability Wait to Seek Disability Services.” Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 25 (2): 145–159.

- Madriaga, M., K. Hanson, C. Heaton, H. Kay, S. Newitt, and A. Walker. 2010. “Confronting Similar Challenges? Disabled and Non-Disabled Students’ Learning and Assessment Experiences.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (6): 647–658. doi:10.1080/03075070903222633.

- Majoko, T. 2018. “Participation in Higher Education: Voices of Students with Disabilities.” Cogent Education 5 (1): 1542761–1542717. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2018.1542761.

- Matthews, K. E., J. Tai, E. Enright, D. Carless, C. Rafferty, and N. Winstone. 2021. “Transgressing the Boundaries of ‘Students as Partners’ and ‘Feedback’ Discourse Communities to Advance Democratic Education.” Teaching in Higher Education: 1–15, April. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1903854.

- Morris, C., E. Milton, and R. Goldstone. 2019. “Case Study: Suggesting Choice: Inclusive Assessment Processes.” Higher Education Pedagogies 4 (1): 435–447. doi:10.1080/23752696.2019.1669479.

- Nieminen, J. H. 2022. “Assessment for Inclusion: Rethinking Inclusive Assessment in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 1–19, January. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.2021395.

- O’Neill, G. 2017. “It’s Not Fair! Students and Staff Views on the Equity of the Procedures and Outcomes of Students’ Choice of Assessment Methods.” Irish Educational Studies 36 (2): 221–236. doi:10.1080/03323315.2017.1324805.

- O’Neill, G., and T. Maguire. 2019. “Developing Assessment and Feedback Approaches to Empower and Engage Students.” In Transforming Higher Education through Universal Design for Learning, edited by Seán Bracken and Katie Novak, 277–294. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351132077-17.

- O’Shea, S. 2016. “First-in-Family Learners and Higher Education: Negotiating the ‘Silences ‘ of University Transition and Participation.” HERDSA Review of Higher Education 3: 5–23.

- Sefcik, L., M. Striepe, and J. Yorke. 2020. “Mapping the Landscape of Academic Integrity Education Programs: What Approaches Are Effective?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (1): 30–43. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1604942.

- Shpigelman, C., S. Mor, D. Sachs, and N. Schreuer. 2021. “Studies in Higher Education Supporting the Development of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education: Access, Stigma, Identity, and Power.” Studies in Higher Education: 1–16. doi:10.1080/03075079.2021.1960303.

- Stampoltzis, A., E. Tsitsou, H. Plesti, and R. Kalouri. 2015. “The Learning Experiences of Students with Dyslexia in a Greek Higher Education Institution.” International Journal of Special Education 30 (2): 157–170.

- Stentiford, L., and G. Koutsouris. 2021. “What Are Inclusive Pedagogies in Higher Education? A Systematic Scoping Review.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (11): 2245–2261. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1716322.

- Tai, J., R. Ajjawi, M. Bearman, D. Boud, P. Dawson, and T. Jorre de St Jorre. 2022. “Assessment for Inclusion: Rethinking Contemporary Strategies in Assessment Design.” Higher Education Research and Development, in Press doi:10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451.

- Tai, J., R. Ajjawi, and A. Umarova. 2021. “How Do Students Experience Inclusive Assessment? A Critical Review of Contemporary Literature.” International Journal of Inclusive Education: 1–18, December. doi:10.1080/13603116.2021.2011441.

- Tai, J. R. Ajjawi, M. Bearman, J. Dargusch, M. Dracup, L. Harris, and P. Mahoney. 2022. Re-Imagining Exams: How Do Assessment Adjustments Impact on Inclusion? Perth. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/exams-assessment-adjustments-inclusion/.

- Tenorio-Rodríguez, M. A., J. González-Monteagudo, and T. Padilla-Carmona. 2021. “Employability and Inclusion of Non-Traditional University Students: Limitations and Challenges.” IAFOR Journal of Education 9 (1): 133–151. doi:10.22492/ije.9.1.08.

- Tobbell, J., R. Burton, A. Gaynor, B. Golding, K. Greenhough, C. Rhodes, and S. White. 2021. “Inclusion in Higher Education: An Exploration of the Subjective Experiences of Students.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 45 (2): 284–295. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2020.1753180.

- Waterfield, J., and B. West. 2006. Inclusive Assessment in Higher Education: A Resource for Change. Plymouth: University of Plymouth. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315045009.

- Willems, J. 2010. “The Equity Raw-Score Matrix - a Multi-Dimensional Indicator of Potential Disadvantage in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 29 (6): 603–621. doi:10.1080/07294361003592058.

- Winstone, N. E., and D. Boud. 2022. “The Need to Disentangle Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (3): 656–667. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1779687.