Abstract

This paper discusses the role of formative feedback in teaching academic writing for a large class of first-year business students. The paper contributes to our knowledge on how to design an effective formative feedback process for a class in excess of 300 students. Based on survey data from 2018 the paper addresses how the students respond to being taught academic writing in two different feedback modalities: face-to-face interaction and electronic annotations. Our findings indicate that there are no significant differences between the two modalities and that the students are relatively satisfied with the feedback they received. The majority of the students report that feedback has helped them accomplish their learning goals, they pay attention to feedback, and feedback motivates them in their studies. Even with these positive responses from the students, we question whether our approach is sustainable in the long run. Unless smarter and more efficient ways of providing personalised feedback are developed for large student groups, the transition to the new paradigm for feedback, where the emphasis is placed on dialogic interaction, will not be practicable.

Introduction

While Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) argue that feedback can be one of the most powerful influences on student learning, the question of how to provide effective formative feedback remains. The feedback process is complex (Carless Citation2006), and the practice of feedback varies greatly. Reviewing research on feedback, Hounsell et al. (Citation2008, 56) write: “The quantity of feedback provided by tutors, and its helpfulness to students, appeared to range widely, and could give rise to uncertainty and confusion, as requirements for assigned work seemed to fluctuate from course unit to course unit, and from one tutor to another”. At the same time, feedback is one of the things that students most want (Winstone and Carless Citation2020) and which students often report in surveys as poorly done (Dawson et al. Citation2019).

This also applies to Norway. Two separate national student surveys report dissatisfaction with feedback. In the Student Health and Wellbeing Survey (Knapstad, Heradstveit and Sivertsen Citation2018), only 29% of the students reported that they were satisfied with the feedback, and less than half (44%) were satisfied with the supervision they received. In the study barometer, which measures Norwegian students’ satisfaction with the quality of their study programme, feedback is the dimension which the students in the 2018 survey are least satisfied with (Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education Citation2018).

There are several guiding principles on how to provide effective feedback in higher education. According to Bloxham and Boyd (Citation2007, 104) a key principle of feedback is “that it will usefully inform the student of ways to improve their performance”. Weaver (Citation2006, 379), in her study of written feedback given to students in business and arts and design, found four main themes of feedback which are unhelpful for students in their learning process: “comments which were too general or vague, lacked guidance, focused on the negative, or were unrelated to assessment criteria”. To move forward in our understanding of the role and importance of feedback it may be useful to take the approach suggested by Winstone and Carless (Citation2020, 6), where “feedback is conceptualized as a process whereby students are proactive in seeking, making sense of, and using comments on their performance or their approaches to learning”. A key point in this ‘new paradigm for feedback’, is feedback as dialogic interaction (Carless Citation2015, 207; Winstone and Carless Citation2020, 97). According to Carless et al. (Citation2011, 397) dialogic feedback can be defined as interactive exchanges related to the quality of student work in which interpretations are shared, meanings negotiated and expectations clarified.

Despite a large academic literature on feedback, there are two challenges which are not often addressed explicitly and can both be understood as different versions of the feedback conundrum, i.e. how to develop effective feedback processes within the constraints of time and resources (Carless Citation2015, 17). The first challenge is large classes. Increased class size is a growing phenomenon in higher education, including business schools. Nicol (Citation2010) has reflected on how dialogue and individuality in feedback is being compromised by a mass higher education system. This again raises several new questions: are there limits to providing personalized feedback and if so, what are the obstacles when dealing with large student numbers? May a solution be found in scaling up the input resources, or is it more a question of the teacher’s mindset and willingness to develop new forms of feedback, as suggested by Winstone and Carless (Citation2020, 172)?

The second challenge is related to first-year students. Freshmen need to be introduced to academia’s rules of communication, the role of theory, the academic argument, critical thinking, and not least to develop an academic identity. According to Fisher, Cavanagh and Bowles (Citation2011), engendering a climate where students can actively participate in learning may ease the issues involved in transition to university. However, this requires additional support from academic staff in the early weeks of their university life. Bovill, Bulley and Morss (Citation2011) argue that there is increasing value being placed on engaging and empowering first-year students in order to ensure early enculturation into successful learning at university. With reference to a review of the literature, they found that active learning, timely feedback, relevance and challenge were key characteristics for ensuring this. Krause (Citation2001, 147) pinpoints the importance of the first major assignment for effective transition to university, while Cramp (Citation2011) focuses on the importance of developing a positive learning relationship between student and personal tutor in order to co-construct knowledge, as well as bestowing upon the student a sense of achievement and success at a time when learners may feel most vulnerable to low self-esteem. Not only may this be essential for developing student academic identity, it may also be valuable as part of an institution’s retention strategy.

Picking up on this latter point, feedback may serve yet another purpose: social interaction. According to Statistics Norway every fourth student who started a degree program in 2012 had a sectoral dropout, i.e. absence from higher education for a year or more, and half of these students dropped out during the first year of study (Andresen, Howard, and Lervåg Citation2022, 5). These dropout rates are somewhat higher than in other countries with available data: OECD-average for dropout from the first year in bachelor programmes is 12 percent (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2022, 203). Although a recent Norwegian review of research on dropout from higher education is inconclusive (Hovdhaugen Citation2019), the report suggests that how students are introduced to university, not only outside of the classroom but also within the bounds of teaching, is seen as an important determinant for retention. Many students report that the transition from classroom-teaching to lectures in large auditoriums is difficult, where social exclusion and not being ‘seen’ by their teachers were issues.

Enhancing formative feedback: the case of business students

Our interest in formative feedback stems from the course we teach, an introductory course in ethics and corporate social responsibility at a business school. The feedback conundrum referred to is one of our major challenges: This a first semester course with 350–400 students. From the Norwegian study barometer, we note that business students are amongst the student groups who are least satisfied with feedback in their study programmes, outranked only by four other disciplines. This survey from 2018 is based on 31,256 student respondents from 38 disciplines, of which 4415 were business students.

A further challenge we faced when assigned the course in 2014 was the mismatch between the learning goals and the learning environment. One of the most important learning goals is the ability to critically reflect over how ethics and corporate social responsibility is understood and practiced in the business community. With plenary lectures in the university’s largest auditorium, we struggled with engaging the students in discussions, exchange of thought and critical reflection. We delivered monologues while the students passively listened (or at least were present). Hence, the teaching design was not fostering critical reflection, nor was the design conducive to interacting with the students at an individual level. With this as our starting point, we set out to redesign the course, where formative feedback gradually took centre stage.

In our attempt to engage the students we initially flipped the classroom to create more space for smaller seminars, but the flipped classroom was soon replaced by blended learning. During continuous revisions of the course, we listened closely to student evaluations. While the seminars were designed to enhance exchange of thought, we also introduced writing as a thinking tool to stimulate critical thought. Often students only think of writing as a communication tool where their focus is on the final product. Experienced writers, however, typically think of writing as a process where the main objective is to think, learn and develop arguments (Young Citation2006). In most cases, writing for thinking is more frustrating and challenging, demanding that the writer must defend a particular view. This is especially true for students, as noted by Bean: “The student longs for a ‘right answer’, resisting the frightening prospect of having to make meanings and defend them. Good writing assignments produce exactly this kind of discomfort: the need to join, in a reasoned way, a conversation of differing voices” (2011, 23, our emphasis).

It should also be noted that teaching staff may have their own personal motives for placing more emphasis on writing skills in the feedback process. When the students’ have little or no training in academic writing, the first hurdles can be painful for more than just the students. Providing feedback to texts where the basics are missing is frustrating and time-consuming for teaching staff. ‘You can’t see the forest for all the trees’ is an appropriate saying to sum up how providing feedback can be experienced. It is challenging to provide high quality feedback on content when poor writing skills get in the way. By removing some of the discord, the text becomes more readily available for constructive feedback, i.e., making it possible to focus on the subject matter and improve the feedback quality. In our case, a separate module dedicated to academic writing was thus introduced in 2018 in an attempt to remove some of the discord in the feedback process.

Academic writing serves further purposes at university level. It is a required skill for participating in the academic discourse (Hyland Citation2009), and writing clearly and persuasively is a key characteristic of a liberally educated citizen (Cronon Citation1998). Mastering literacy in a subject is also an important part of socializing the student into a profession (Duff and May Citation2017). Although every academic discipline acknowledges the importance of academic writing, it is not entirely clear how it is incorporated into the curriculum. Zhu reports comments from business faculty that even if writing was considered important at the policy level, and efforts were made to integrate writing into the curriculum, “the success of policy implementation may not always be known” (2004, 35).

With this backdrop, we have actively sought to design a course where academic writing and effective formative feedback are integrated in the course, along with mapping how satisfied the students are with the design and how they relate their learning outcome to the design. In the following sections we will first present the course design as it was in 2018, followed by data from a student survey the same year.

The redesign

In 2018 the course was redesigned to incorporate academic writing as a separate module alongside two other modules dedicated to the subject matter. Academic writing comprised three plenary lectures at the outset of the semester on the why’s and how’s of academic writing (six hours in total), followed by writing practice and formative feedback throughout the semester (integrated in the two other modules). Two different feedback modalities were utilised: the first we refer to as dialogical feedback, while the second is mainly written feedback. The aim of the feedback is not only to increase the students’ proficiency in academic writing and, of course, the subject matter, but also to engage the students in an activity where the return to the student is personalised feedback and the opportunity to be ‘seen’ by, and engage with, the academic staff. This could counterbalance what the students described as unhelpful in their learning process, i.e. comments which were too general or vague and the lack of guidance (Weaver Citation2006, 379).

The teaching design is complex, in that the students must grasp a multitude of instructions with varying content across three different modules and from multiple teachers, all in the space of a few months and at a time when everything about university life is new. The course embraces plenary and video lectures, seminars and extensive group work. With a well-planned and informative learning platform, the students are guided step-by-step and managed to work the ropes regarding the when’s and what’s of class work.

Modality 1: dialogic feedback

Parallel with the introductory lectures in academic writing, the students attended lectures in ethics. At the end of the third week, the students were asked to combine what they had learned in ethics with academic writing, and by the end of week four each student had to hand in an essay. To motivate the students, this first essay constituted a draft, which they after feedback had the option to revise before handing in as the first of two examination papers. A key point with providing the students with detailed feedback on their writing is to encourage them to revise their papers. Revision is an important tool in developing ideas and arguments, and it makes writing clear and persuasive. Learning to see the arguments from the reader’s perspective is essential.

The feedback the students received at this early stage of the course (weeks 5–7) was given in a tutorial where teaching staff sat face-to-face with students in small groups of three to four and engaged in dialogical feedback. Each tutorial lasted 45 min allowing for approximately 10–15 minutes for each essay to be commented upon and discussed. Before commenting on specific essays, the teacher would give a brief introduction and comment on the given case. This general introduction would then be followed by more detailed and personalised comments to each student. The specific feedback was given in writing (teacher’s comments on paper; handwritten or digital) and orally in the form of a discussion where the teacher engages in a conversation with the students. The students who were not the author of the essay in question would listen in on the dialogue, enabling them to also learn from the feedback given to other students. After the tutorial, the students could revise their essay, and hand it in as their first examination paper, constituting 50% of the final grade.

Modality 2: written feedback

The second half of the course aimed to further embed academic writing as a generic skill by reinforcing what the students had learned in the first part. The number of assignments (writing volume) therefore increased. However, the students were asked to write in groups of three to five persons for capacity reasons. The available teaching staff could not read and comment on near 400 assignments every week for three consecutive weeks. The student groups had the option of writing three short essays, whereof two had to be approved before they could sit part two of the final examination.

In the first plenary lecture in the second half of the course exemplars of excellent, good and poor examination papers were discussed. The exemplars were loaded up on the teaching platform before the lecture, and the students were encouraged to read them and reflect over which grade they had attained in an attempt to activate them in recognizing and evaluating a good text.

In addition to two plenary lectures in the final module, the students were offered video lectures and seminars (blended learning). One of the aims of the seminars was to break up the large student group into a series of seminars restricted to 60 students. This would allow the teaching staff to interact with the students more. Following the seminars, the students were asked to write a short essay based on the case discussed during the seminar. The written assignment was uploaded on a digital learning platform, and teaching staff provided feedback by way of electronic annotations (i.e. typed comments in a word or pdf-document). The commented essay was then returned to the students within approximately one week. These essays were not resubmitted, only ‘approved’ or ‘not-approved’. The second part of the course culminated in a 48-h group-based home examination (constituting fifty per cent of the grade), where the student group had to write an essay based on a new case.

Commonalities and differences

The type of written assignment found in business schools may vary, but in general, business writing is complex since most of the assignments emphasize problem-solving (Zhu Citation2004). As noted by Stewart “[r]eplicating real-world problems means reproducing the messiness—the vagueness, ambiguity, and uncertainty—with which a problem first presents itself” (Stewart Citation1991, 122). In our course we challenge the first-year students with the messiness of real life. All the written assignments are based on real-life cases from the business community. The students are asked to apply theory from their curriculum to discuss and reflect on the case in question.

Although the types of written assignments are similar, the mode of providing formative feedback differs. While dialogical feedback allows the student to interact face-to-face with teaching staff, the written feedback mode is not designed for this purpose. Since the same cohort of students is introduced to two different feedback modalities within the same course, it is possible to compare how the students rate different feedback designs offered at the same stage in their university development. We conducted a survey to explore how the students assess the two feedback modalities.

The survey

Our survey is inspired by Dawson et al. (Citation2019). However, due to the extensiveness of this survey, we have utilised an abbreviated version. Students were asked to complete the survey in their last lecture in November 2018. The collection and storage of personal data is done in accordance with the Norwegian Data Protection Act and with the University as the data controller. The data is collected through voluntary action by the students and the students are anonymous. SurveyXact was used to collect data, which was transferred to and analysed in SPSS. At the time of data collection 337 students were registered as eligible to sit part two of the final examination. 171 students fully completed the questionnaire, while 21 partially completed it: i.e., the response rate for fully completed questionnaires is 50.7, while the response rate for partially completed questionnaires is 57. Both these response rates are acceptable.

Most of the respondents were young, new to a university setting, and had little or no previous experience with academic writing: 71% were 21 years or younger, 79% stated that they were in their first semester at a university, and 87% had never previously taken a course in academic writing.

Results

Almost all the student respondents (93%) were satisfied with the six hours of plenary lectures in academic writing. Furthermore, a large majority (84%) agreed that these lectures gave them the information and skills they needed to complete the first course assignment.

Dialogical feedback

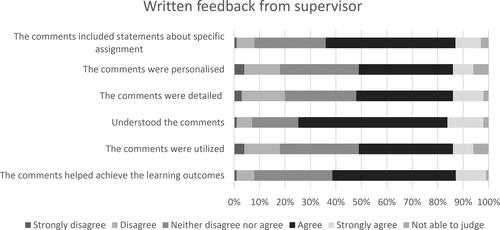

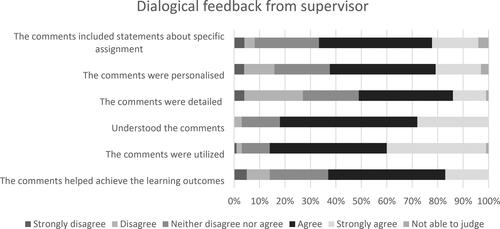

The students were asked how satisfied they were with the supervision, academic counselling, guidance and tutoring they received in the ethics part of the course: 38% reported that they were very satisfied, 51% were somewhat satisfied, while 11% were not satisfied. The students were also asked to assess the feedback by stating their degree of agreement with six statements. The results are given in . Approximately 60% agree that the feedback was personalised and specific to their assignment. Even though only half of the respondents agreed that the feedback was detailed, a large majority (82%) either strongly agree or agree that they understood the comments, while 85% agree that the comments were utilized. The majority (63%) also agreed that the comments helped them achieve the learning outcomes for the course, while 23% neither disagreed nor agreed to this latter statement.

Figure 1. Degree of agreement regarding feedback from supervisor in the ethics part of the course where dialog was utilized. Percent.

In sum, tells us that the students have valued the feedback provided by teaching staff in the ethics part of the course where dialogical feedback was utilised. The students report that they understood and utilized the comments, although many would have preferred even more detail in the feedback.

Written feedback

In the corporate social responsibility part of the course, the students primarily received written feedback through electronic annotations: i.e. typed comments in a word or pdf-document. Again, the students were relatively satisfied, but to a lesser degree compared to the dialogical feedback: 20% were very satisfied, 65% were somewhat satisfied, while 15% of the students were not satisfied with the feedback they had received.

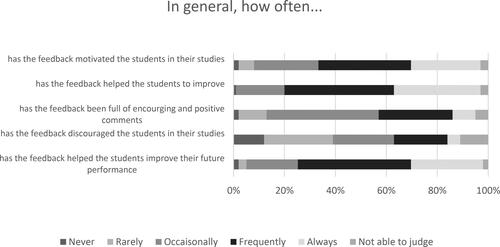

illustrates how students assess the feedback in this module. The majority (61%) agree that the comments were specific to their assignment, but not as many agree that the comments were personalised (45%). Half of the respondents agreed that the comments were detailed, and a clear majority (72%) understood the comments. However, compared to the feedback they received in the ethics module, not as many stated that the feedback was utilized (45% against 85%). Nevertheless, 61% agree that the feedback/comments helped them achieve the learning goals, a score which only slightly differs from the ethics module (63%).

Feedback in general

In addition to the specificities of feedback pertaining to the two modules in our course, the students were also asked to assess the value of feedback at university in general. The students were asked how often the feedback had an impact on a variety of questions. From we can see that feedback has frequently or always impacted improvement. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents (64%) report that the feedback has frequently or always motivated them in their studies. Even though the feedback has not always been full of encouraging and positive comments, it has to a lesser extent discouraged them in their studies.

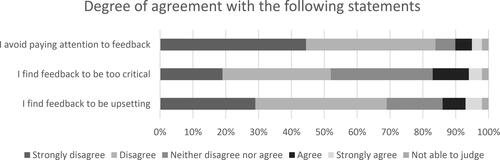

As a follow-up to the data in , the students were also asked more specifically to comment on three statements that focused on their behaviour and emotions concerning feedback. The responses are given in . The great majority (83%) pay attention to the feedback they receive. Over half of the respondents (52%) disagree that the feedback is too critical, while over two-thirds (69%) disagree that the feedback is upsetting. When correlating the three variables in with the background variables, only one statistically significant relationship is found, i.e. age and finding the feedback to be upsetting (significance level 0.05). The youngest students (18–21 years) most often found the feedback to be upsetting.

Students’ feedback preferences

Since different feedback modes have been utilised on the same group of students, we were eager to see what mode of feedback the students preferred in the future. The question put to the students was: How would you prefer to receive comments on assignments? You may choose more than one answer. The results are given in . The students prefer the two modes of feedback they were familiar with in the course, i.e. face-to-face feedback and electronic annotations.

Table 1. Students’ preferences for feedback: ranked in order of highest preference.

When we correlate the variables in with the background variables, we find a statistically significant correlation at 0.01-level between age and the preference to receive comments through hand-written comments on a hard copy document. Again, it is the youngest students (18–21-year-olds) who prefer this alternative: Almost half (49.3%) of this age group state this preference.

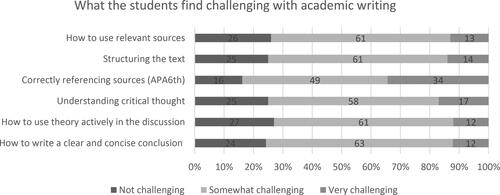

Challenges in academic writing

So far, the focus in this article has been on feedback, i.e. how the students experienced and assessed the feedback. The survey also includes a question of what the students found challenging with academic writing. From we can see that correctly referencing sources was the task the students found most challenging: 34% found this task very challenging.

Discussion

All in all the students seem appreciative, answering that the feedback has helped them improve their work, achieve their learning outcomes, and motivated them in their studies. Although not completely comparable, our data indicates that our students are more satisfied with the feedback and supervision they received compared to the students in the national student health and wellbeing survey, where only 29% of the students were satisfied with the feedback they had received (Knapstad, Heradstveit and Sivertsen Citation2018).

Given Cramp’s (Citation2011, 113) conclusion that developing positive learning relationships with personal tutors at the point of assessment feedback can encourage a sense of achievement and success at a time when learners may feel most vulnerable to low self-esteem, we had expected to find greater variance in how the students viewed the two modalities we tested, one with and one without personal tutoring. Although Cramp focuses on assessment feedback, the same argument could be made for feedback in general. Hence, we expected the students to prefer face-to-face feedback. We were therefore somewhat surprised when the students responded so similarly to the two modalities, particularly with regards to learning outcome. While 63% of the students agreed that the comments arrived at through dialogical feedback helped them achieve the learning outcomes, 61% of the students replied the same with regards to solely written comments. When further asked what type of feedback they would prefer in the future (), the students’ response to the two modalities is quite similar, confirming the impression that they were more or less equally satisfied with the two modalities.

Although most of the students were generally satisfied with the feedback they received, some differences between the two modalities may be noted. When asked about the dialogical feedback the students were slightly more satisfied compared to the solely written feedback. Only along one dimension did the written feedback score higher of the two, namely that the comments were detailed. Due to the large number of students, two tutors were engaged in providing the dialogical feedback, a task which engaged the tutors five days a week for three consecutive weeks. In addition, the time allocated to the face-to-face tutorial was no more than 15 min per student. The combination of a heavy workload with restricted time to write extensive comments on each essay, as well as limited time in the face-to-face meeting, may explain the response. A further explanation may lie in a lack of alignment between the tutors regarding how detailed the feedback should be, i.e. how and what comments to give. From their study of large classes, Whisenhunt et al. (Citation2019, 125) suggest that individual instructor variables may be as important as class size in influencing students’ perceptions of the course. This may also be the case in our study, but this is a facet which we have not measured.

Another difference that may be noted is that the students were clearer in their stance when it came to the dialogical feedback. If we look at all the six responses in and , we can see that the feedback provided in the module where a face-to-face tutorial was utilized spurred more agreement and more disagreement, compared to the feedback in the module where electronic annotations were used. The larger degree of indifference in the latter module may be explained by several factors. Firstly, the feedback which was solely given in writing was feedback on a group assignment. Group assignments allow for more unequal distribution of tasks and responsibilities: while some group members take more responsibility, others take less, and some take none (free-riders). Students who put little, if no, effort into an assignment may also be more indifferent to the feedback comments. Another explanation may lie in the face-to-face interaction which characterizes the dialogical feedback. A personal meeting may be experienced as a greater commitment to the task at hand. A personal meeting may also rouse more emotions, and for some the experience may be intimidating, especially when young and insecure. These emotional aspects may trigger the students to be more opinionated, which again may be reflected in the answers.

The students were asked if they found the feedback to be too critical or upsetting (). Some (15.2%) found the feedback too critical, but fewer (12.3%) found it upsetting. It is, however, the youngest students (aged 18–21) who found the feedback to be upsetting. Unfortunately, this data is not linked directly to the two modalities, but we know from the analysis of the students’ future preferences that the same age group prefer electronic annotations, i.e. not face-to-face interaction with the tutor. This may indicate that the youngest students experience the personal tutorial as more intimidating than the more mature students. As noted earlier, first-year students may find transition to university challenging, requiring additional support from academic staff in the early weeks of their university lives (Bovill, Bulley and Morss Citation2011). Our data suggests that this may be particularly true for the youngest students. In 2021, the University Board decided that all faculties must implement first-semester initiatives by 2026 in order to ease transition to university life. So far, the initiatives have been sparse, focusing mainly on student–student relations in the first two weeks, and less on student–tutor relations where academic writing, active learning and timely feedback is emphasized.

More generally, all the respondents were asked what they found challenging with academic writing. We were once again surprised by the answers. Judging from the feedback process and the final examination, we had expected the students to answer understanding critical thought or how to use theory actively in a discussion. However, the students found correctly referencing sources as the most challenging: 34% found it very challenging, while 49% found it somewhat challenging, cf. . This response may indicate that the teaching staff put too much effort in commenting on how to reference, to the detriment of understanding critical thought or using theory.

To sum up, in providing the feedback two different modalities were used. Although both feedback modalities sought to provide personalised feedback, the feedback following the individual essay was face-to-face in a tutorial, while the feedback following the group assignments was written annotations only. The course has a two-part examination, but both parts align with what the students have practiced, i.e. writing essays based on real-life cases from the business community.

The overall picture is encouraging, with marginal differences between the two tested modalities. However, these results give us no guidance as to future choices. Neither modalities stand out as superior to the other, and both have flaws. The room for individual face-to-face dialogue and interaction between academic staff and the students was limited in both modalities. In the ethics module the tutorials were limited to one session with 15 minutes per student with two to three other students present, while in the corporate social responsibility module the face-to-face interaction took place in seminars with 60 students present. It is not difficult to argue that the development of a positive learning relationship between student and personal tutor with the aim of co-constructing knowledge (Cramp Citation2011), or interactive exchanges where interpretations are shared, meanings negotiated and expectations clarified (Carless et al. Citation2011), was not adequately facilitated for in our two modalities. The resources allocated to each student were limited, the face-to-face interaction was insufficient, and perhaps too intimidating for some to achieve the interactive exchanges described above.

So where does this leave us? Is it a question of scaling up input resources or a matter of the teachers’ mindset and willingness to develop new forms of feedback, as Winstone and Carless (Citation2020) suggest? According to Winstone and Carless (19) the “old paradigm feedback approaches do not work with large classes because it is often impossible to provide detailed teacher comments to numerous students within stipulated turnaround times”. This we can partly agree on. Only partly because the students report back that their learning is enhanced by the feedback they were provided, albeit it is not the co-construction of knowledge as outlined by Cramp (Citation2011).

What is certain is that we are not in a position to scale up further, for example by allocating more time to each student in a tutorial or providing more tutorials. The course already demands resources beyond what is normally estimated for a course of this size, and no other first-year course at the business school is allocated the same amount of resources. This is the flagship. If we were to scale up further, the trade-off would have to be fewer students. That brings us back to the question of the limitations of providing dialogue and individuality in feedback when dealing with large student groups (Nicol Citation2010).

Conclusion

The course we teach embraces many of the major challenges faced by university teachers: a very large number of students, a subject content the students initially do not see the relevance of and hence do not experience as highly motivating to learn, and first semester students new to the rigours of academic standards. To meet these challenges, we designed a first semester course where academic writing and formative feedback play major roles in enhancing student learning and developing academic identity. A crash course in academic writing was motivated by the need to align the students’ abilities to the standards of academia. Further to this, exemplars of poor, good and excellent examination papers were utilized to enhance the learning process, and after just a few weeks into the first semester, the students received their first formative feedback.

Winstone and Carless (Citation2020, 19) state that large classes require a different way of thinking, including features such as pre-assessment guidance rather than post-task comments; the skillful use of exemplars embedded within the curriculum, and supporting students in developing an active role in self-monitoring their work in progress. Although most of the feedback we provided was of the post-task type, we did utilize exemplars prior to the assignments. However, a dimension we yet have to explore is activating the students in self-monitoring their work. This dimension demands further thought and careful consideration before adding to what is expected of students in their initiation to university life. Far from all the students are academically committed students who have a deep approach to learning, reflect over the personal significance of learning, and need little help from teachers (Biggs Citation1999, 57). It therefore remains to be seen whether aligning a large class of students to self-monitoring their work is both realistic and time wisely spent.

We will continue to be inspired, re-evaluate and revise. Our mind is not set when it comes to finding new and perhaps better ways to teach. However, we question whether our present approach is sustainable in the long run. Although our students have achieved a basic understanding of academic writing requirements, this knowledge is not utilized in many of their remaining courses. To succeed we believe that the teaching of generic skills and how to translate the importance of feedback into tenable action is not something that should be left to individual teachers but should be integrated into the whole programme. For this we need a new programme strategy which encapsulates to a larger extent generic skills in addition to discipline skills.

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Andresen, S., M. Howard, and M.-L. Lervåg. 2022. “Frafall Og Bytter i Universitets-Og Høgskoleutdanning. Kartlegging Av Frafall Og Bytte Av Studieprogram Eller Institusjon Blant De Som Startet På En Gradsutdanning i 2012.” [Dropouts and transfers in higher education. Mapping dropout and transfers in study programmes or institutions amongst students who started a degree program in 2012]. Report 2022/6. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

- Bean, J. C. 2011. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. San Francisco: Wiley.

- Biggs, J. 1999. “What the Student Does: Teaching for Enhanced Learning.” Higher Education Research & Development 18 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1080/0729436990180105.

- Bloxham, S., and P. Boyd. 2007. Developing Effective Assessment in Higher Education: A Practical Guide. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bovill, C., C. J. Bulley, and K. Morss. 2011. “Engaging and Empowering First-Year Students Through Curriculum Design: Perspectives from the Literature.” Teaching in Higher Education 16 (2): 197–209. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.515024.

- Carless, D. 2006. “Differing Perceptions in the Feedback Process.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1080/03075070600572132.

- Carless, D. 2015. Excellence in University Assessment: Learning from Award-Winning Practice. London: Routledge.

- Carless, D., D. Salter, M. Yang, and J. Lam. 2011. “Developing Sustainable Feedback Practices.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (4):395–407. doi:10.1080/03075071003642449.

- Cramp, A. 2011. “Developing First-Year Engagement with Written Feedback.” Active Learning in Higher Education 12 (2): 113–124. doi:10.1177/1469787411402484.

- Cronon, W. 1998. “Only Connect…’ The Goals of a Liberal Education.” The American Scholar 67 (4): 73–80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41200203.

- Dawson, P., M. Henderson, P. Mahoney, M. Phillips, T. Ryan, D. Boud, and E. Molloy. 2019. “What Makes for Effective Feedback: Staff and Student Perspectives.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (1): 25–36. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877.

- Duff, P. A., and S. May (Eds.). 2017. Language Socialization (3rd ed.). Cham: Springer.

- Fisher, R., J. Cavanagh, and A. Bowles. 2011. “Assisting Transition to University: Using Assessment as a Formative Learning Tool.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (2): 225–237. doi:10.1080/02602930903308241.

- Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77 (1): 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Hounsell, D., V. McCune, J. Hounsell, and J. Litjens. 2008. “The Quality of Guidance and Feedback to Students.” Higher Education Research & Development 27 (1): 55–67. doi:10.1080/07294360701658765.

- Hovdhaugen, E. 2019. “Reasons for Dropping out of Higher Education: A Research Summary of Studies Based on Norwegian Data.” NIFU Working Paper 2019:3. Oslo: The Nordic Institute for Studies of Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU).

- Hyland, K. 2009. Academic Discourse: English in a Global Context. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Knapstad, M., O. Heradstveit, and B. Sivertsen. 2018. Studentenes Helse-Og Trivselsundersøkelse 2018 [Students’ Health and Wellbeing Survey 2018]. Oslo: Studentsamskipnaden i Oslo og Akershus.

- Krause, K.-L. 2001. “The University Essay Writing Experience: A Pathway for Academic Integration During Transition.” Higher Education Research & Development 20 (2): 147–168. doi:10.1080/07294360123586.

- Nicol, D. 2010. “From Monologue to Dialogue: Improving Written Feedback Processes in Mass Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (5): 501–517. doi:10.1080/02602931003786559.

- Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT). 2018. Studiebarometeret 2018: Tilbakemelding og veiledning. [The Study Barometer 2018: Feedback and Tutoring.] https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/studiebarometeret/2019/tilbakemelding-og-veiledning-studiebarometeret-2018.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2022. Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/3197152b-en.

- Stewart, A. H. 1991. “The Role of Narrative Structure in the Transfer Ideas: The Case Study and Management Theory.” In Textual Dynamics of the Professions. Historical and Contemporary Studies of Writing in Professional Communities, edited by Charles Bazerman and James Paradis (Eds.), 120–144. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Weaver, M. R. 2006. “Do Students Value Feedback? Student Perceptions of Tutors’ Written Responses.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 31 (3): 379–394. doi:10.1080/02602930500353061.

- Whisenhunt, B. L., C. Cathey, M. E. Visio, D. L. Hudson, C. F. Shoptaugh, and A. D. Rost. 2019. “Strategies to Address Challenges with Large Classes: Can We Exceed Student Expections for Large Class Experiences?” Scholarship of Teaching & Learning in Psychology 5 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1037/stl0000135.

- Winstone, N., and D. Carless. 2020. Designing Effective Feedback Processes in Higher Education. A Learning-Focused Approach. London: Routledge

- Young, A. 2006. Teaching Writing Across the Curriculum (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Prentice Hall Resources for Writing.

- Zhu, W. 2004. “Faculty Views on the Importance of Writing, the Nature of Academic Writing, and Teaching and Responding to Writing in the Disciplines.” Journal of Second Language Writing 13 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2004.04.004.