Abstract

This paper explores institutional leaders’ perceptions of learning and teaching involved in facilitating and assessing Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) survey instruments across Australian regional universities. It focuses on how they understand the function of SET, strategies used to mitigate bias, and potential residual harm. Through adopting a combination of inductive and deductive research processes and a thematic analysis through the ethical lens of nonmaleficence (first, do no harm), we report that leaders in learning and teaching perceive SET as a form of surveillance and Quality Assurance ‘performance’, recognise inherent biases inhabited in SET reports, and identify how these biases negatively impact academics through a lack of systematic harm mitigation strategies. The paper’s critical – and novel – contributions include an increased understanding of how SET inflicts harm towards women and other marginalised academic groups through systematic and authorised microaggressions and how SET contravenes universities’ duty of care to employees. It recommends an expansion of the principle of nonmaleficence beyond potential harm to research subjects, including those who undertake research or evaluation (such as academics), particularly if these impact them.

Introduction

Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) is the most widely used assessment instrument for collecting and interpreting higher education student feedback to inform course and teaching improvement, staff tenure and promotion, and recruitment processes. University administrators use SET in higher education to make academic retention, pay increases, tenure, and promotion decisions. However, like all survey instruments, SET ‘are not impervious to subjective factors and biases (both explicit and implicit) that students may possess’ (Cone et al. Citation2022, 1085) and which articulate into evaluative responses. Students may hold socially constructed assumptions about what constitutes effective teaching and maintain certain gendered stereotypes of male and female faculty (Khazan et al. Citation2019). Consequently, student perception of the course and teaching quality may be influenced by the gender (and/or other personal or cultural features) of the academic convening the course or unit. It is important to pause here and note that we understand male and female are biological terms that are imbued with socially constructed connotation. We try not to use ‘female’ as it implies that all females are women, and all women are female. However, we lean on scholarship and survey instruments that often use these terms. We recognise the complexity of gendered terminology and positionalities and hope that our work supports people who also live outside of gendered binaries.

When students’ expectations remain unfulfilled, they may respond with critical and, at times, hostile reactions, which place some teachers at a disadvantage by influencing perceptions of their teaching effectiveness (Cunningham et al. Citation2023; Heffernan Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2023). Yet, despite the increasing recognition of the volume and impact of biased and, at times, abusive feedback in SET surveys, minimal research pays attention to the emotional trauma and psychological harm they pose to academic staff (Cunningham et al. Citation2023; Heffernan Citation2023), or which considers the ethical implications of SET (McCormack Citation2005), or more specifically the ethical implications of the impacts and implications of administering SET more generally.

This paper addresses these research gaps by exploring the perceptions and experiences of leaders of learning and teaching involved in facilitating and assessing SET assessment instruments across Australian regional universities, focusing mainly on how they understand the function of SET and strategies to mitigate bias and any residual harm it may cause. We contextualise the study by first offering an overview of scholarship concerned with the recent history of SET, its main functionality, and how it has been received/perceived by academics. We also consider literature that explores biases made manifest within student responses and the effect of stereotyping. The paper then provides an overview of the research methodology employed in this study, which combines inductive and deductive analytical approaches overlayed with the principle of nonmaleficence (first, do no harm), before presenting a summary and thematic analysis of the research findings.

The critical contribution of this research includes an increased understanding of how SET operates as a surveillance mechanism that inflicts harm towards women and other marginalised academic groups – such as those from non-white racial groups, culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, older academics, and academics with diverse genders and sexualities – through systematic and authorised microaggressions. We also consider the ethical implications of administering SET and universities’ duty of care to its employees. The paper recommends an expansion of the principle of nonmaleficence beyond potential harm to research subjects to include the people undertaking research – particularly if the research or evaluation directly impacts them.

Literature review

Recent history of SET

In the 1970s, the SET instrument became the primary method for formative assessment to improve the quality of courses and measure the capability/competence of teachers and teaching practice (Kayas, Assimakopoulos, and Hines Citation2022). Over the years, SET has evolved into a summative evaluation tool, the primary performance management tool, and an indicator for the promotion and tenure of academic staff (see Heffernan Citation2018). Estimates suggest that over 16,000 higher education institutions’ teaching staff collect SET results at the end of each teaching period (Cunningham-Nelson, Baktashmotlagh, and Boles Citation2019). In many cases, SET is used as the sole performance indicator of teaching competence (Spooren, Brockx, and Mortelmans Citation2013).

Adopting the SET tool became popular because of the potential perceived benefits for stakeholders – university administrators/managers, students, and academics. SET provides managers with insights to validate new programs; provides academics/instructors with feedback to enhance courses and improve individual teaching practice, leading to promotion and tenure (Johnson Citation2000); empowers students with a source of information to aid their choice of where and what to study (Collini Citation2012), and a voice for their student experience. However, Heffernan (Citation2018) raised concerns over six years ago about the current use of SET, including critiques of how student biases are embedded within SET responses.

Gender bias and the effect of stereotyping

One of the critical issues emerging within the literature is the presence and impact of gender bias on SET results. According to social psychological theory, gender biases in SET assessment may occur because of a lack of fit between gender stereotypes and individuals’ professional roles, leading to negative evaluations (Kwok and Potter Citation2022). This position supports Khazan et al. (Citation2019) investigation into the relationship between bias, prejudice, and gender in student evaluations of an extensive, asynchronous online course. The research argues women faculty in male-dominated disciplines ‘face prejudice like that experienced by women leaders, resulting in similar consequences. The incongruity of these perceived roles can result in fewer women entering male-dominated disciplines, and women who do enter these disciplines receive poorer performance evaluations’ (Khazan et al. Citation2019, 423).

As far back as the 1980s, research indicated the presence and impact of gender bias in student evaluations of teaching responses (Bennett Citation1982) – a trend that continues. A more contemporary examination of the literature on bias in student evaluations by Kreitzer and Sweet-Cushman (Citation2021) produced a novel dataset of over 100 articles, providing a nuanced review of this broad but established literature. The review indicated researchers and scholars, using different data and methodologies, routinely identify that women faculty and those from other marginalised groups face significant biases and are thus disadvantaged in SET responses.

Student comments, language, the volume, and impact of abusive and malicious responses

Mitchell and Martin (Citation2018) identified students appropriated different language to evaluate men’s and women’s academic performance in their qualitative comments. They applied more subjective criteria when considering women than their male counterparts. Students frequently commented about women academics’ personalities and appearance, referring to them as ‘teachers’. In contrast, other comments referred to male instructors as ‘professors’ and focused on their professional objectives, such as intelligence (Mitchell and Martin Citation2018).

Other studies are concerned with the use of negative student comments in SET assessment by highlighting the use of offensive, unprofessional, abusive, and malicious language, exhibiting gender bias, homophobic prejudice, sexism, and racism in Australian universities (see Cunningham et al. Citation2023; Heffernan Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2023). Moreover, Heffernan (Citation2022b) found that student evaluations ‘openly prejudiced against the sector’s most underrepresented academics … contribute to further marginalising the same groups universities declare to protect and value and aim to increase their workforces’ (199).

Heffernan’s (Citation2023) ongoing research on the volume, type, and impact of anonymous student comments on 674 academics highlights the amount and type of abusive comments academics receive. The research outlines how women and marginalised groups received the highest volume, most derogatory, and most threatening abuse. Equally troubling is that the research underestimates the magnitude and severity of abusive comments academics receive. Related research by Cunningham et al. (Citation2023) documented a machine-learning approach to screening 100,000 student comments in one institution in 2021. This project prevented 100 abusive comments (within one institution only) from reaching academic staff members. While some might dismiss the small percentage of unacceptable comments made by students as minimal and thus insignificant (statistically), Cunningham et al. (Citation2023) recommend capturing inappropriate comments to ensure students know when their comments are unacceptable to the university.

The growing body of research focusing on using SET is welcomed. Yet, there is a lack of understanding of how the leaders of learning and teaching within universities perceive SET and mitigate any biases inherent within survey responses. Accordingly, negligible research exists on the impact of SET on the mental health and wellness of academic staff about whom SET responses are based.

Research methodology

We explore perceptions of academics and learning and teaching leaders who facilitate or lead SET in regional universities, considered through the lens of ethical practice, particularly the principle of ‘first, do no harm’. While healthcare practices and research often employ nonmaleficence, they rarely engage in educational research (Buchanan and Warwick Citation2021). Additionally, when applied to the planning and evaluating of a research project within the Human Ethics application processes, consideration is usually limited to the wellbeing of research participants without concern for the people (or the work of people) who are the focus of research or evaluation. We thus expand the frame of reference to include a consideration of ‘first, do no harm’ to the people who undertake evaluations or research (particularly teachers through the SET process) and to whom research, or evaluation reports are presented. This novel methodological approach is informed by the scholarship summarised above, which suggests SET practices inhabit biases that can harm academics, particularly women academics and those from other marginalised groups.

The methodology incorporates elements of both inductive and deductive research processes. Our initial literature review provides a map of the central discourses within and around SET, which sensitised us to the possibility that participants may perceive SET as biased and unfair. Yet, while we were aware of current discourses, we attempted to review the research data without prejudice by adopting a deductive approach.

Methods

Survey

Upon obtaining ethical clearance (Ethics Number: de-identified) between November 2022 and June 2023, the research team invited directors and senior staff of learning and teaching units across the Regional Universities Network to complete and distribute an online survey amongst their relevant staff. Regional universities in Australia are typically located in non-metropolitan areas, often serving cities and towns that are distant from the major urban centres. These locations are typically categorized as regional, rural, or remote based on various classification systems such as the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) remoteness areas. Regional Universities Network/RUN is a network of universities primarily from regional Australia. Open questions were designed to garner participants’ understanding of the role of SET, the relationship between student evaluation and teaching quality, and if and how they undertake measures to optimise the completion. of SET and mitigate bias in the SET process. The survey was designed to garner responses that would be thematically analysed.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a versatile qualitative research method to explore and analyse relevant patterns, meanings, and themes within textual/interview data rooted in various theoretical frameworks (Braun and Clarke Citation2023). The approach allows researchers to strategically explore and understand the lived experiences, perspectives, and meanings attributed by participants to those experiences (see Braun and Clarke Citation2023).

Results and findings

Survey outcomes

A total of 55 leaders in learning and teaching completed the survey. The results are tabled below ().

Table 1. Leaders in learning and teaching responses.

From the data, 12 survey respondents identified as men and 42 as women, with the remainder preferring not to disclose. A total of 46 respondents identified as white, five as non-specified other racial identity, one as Asian, and one as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Of the respondents, 40 identified they did not have a disability or long-term condition, 13 identified that they did, and four preferred not to disclose. To ensure participant anonymity, we have not linked these demographic features to the positions or roles held by the participants.

The number of respondents did not allow for statistically significant quantitative findings or generalisable claims to be made. Instead, we present the demographic breakdown of participants to contextualise the following overview of the qualitative data from the survey instrument. As the richest data was provided through qualitative comments, we focus this paper on the thematic analysis of the qualitative responses provided within the survey instrument.

Thematic analysis

The thematic analysis process we undertook, post-initial read and identification of broad themes, was layered by a lens of nonmaleficence. We maintained a concern for how leaders of learning and teaching perceive the function of SET, potential risks associated with SET and harm mitigation strategy. These were not used as hard and fast categories but were considerations that coloured our close reading of the results.

Dominant themes identified in the survey responses include how leaders in learning and teaching perceive SET to operate as a form of surveillance and Quality Assurance ‘performance’. Respondents also recognised inherent biases in SET reports, detailing how these biases impact academics’ mental and emotional health and result in career impacts. Despite some individualised risk mitigation strategies, it was perceived that the systematic harm mitigation strategy was not consistently employed and that the current use of SET contravenes universities’ ‘duty of care’ to their employees.

Surveillance

Through a thematic analysis of open-text survey responses, respondents perceived SET predominantly as a form of managerial surveillance and subsequently as a ‘punitive measure’ to rank and punish academics considered underperforming. Survey responders specifically described the deployment of SET as ‘a surveillance mechanism’ or ‘blunt instrument’ used to ‘monitor of staff by management’ [with] potential for the data to be used as a ‘big stick’’. These themes were repeated across several responses (n = 15), which included descriptions of SET as employed ‘to reprimand faculty for bad teaching’ and ‘used against academics in performance reviews or promotion applications.’ Respondents also indicated that despite SET responses generally being too low to represent the student body, management used the results to assess academics’ learning and teaching quality with potential impacts on their employment and career success. Relatedly, managerialism was similarly inherent in the second theme of the results – Quality Assurance performance.

Performativity of quality assurance

Several respondents (n = 6) indicated they perceived SET as a ‘compliance measure’, while others perceived SET as a disingenuous approach to the quality assurance process: ‘[SET is] required to demonstrate accountability’, so ‘universities can be seen to be looking after and valuing the paying customer’ and a ‘performance management mechanism rather than as a continuous improvement mechanism’.

Of note is that the results did not provide significant commentary relating to the benefits of SET to the quality assurance of learning and teaching; instead, they focused on perceived performativity.

In the interest of nonmaleficence, please note the following section of survey results contains references to various biases communicated via SET and to the psycho-emotional harms they can create. To protect yourself from vicarious trauma, you may wish to bypass this section of text and move to the ‘Discussion’ section below.

Inherent bias

The significant impact of perceived biases embedded within SET responses was explained in terms of a small sample size of responses and student anonymity inherent in the survey design. Examples include:

‘They can be biased because only a few students complete them’; ‘A small, biased sample of students complete the SET. This sample is not representative of the population’; ‘The feedback from such a small, unrepresentative sample should not be used to determine the strengths or limitations of a course’; ‘The fact that it is anonymous means that students can say what they like and get away with things they could never say if they were identifiable and accountable’; ‘[biases are] fostered through the anonymity of the instrument’.

Students use these as opportunities to discriminate and speak rudely and derogatory about the staff - especially women staff and bias against women with other marginalised status: ‘Student bias - especially against women and people of colour’; ‘If you are female, international, Indigenous, old, etc., etc. then chances are your SET scores will be lower’; ‘I have seen comments which speak negatively about academic staff based on race, gender and perceived sexual identity.’

‘I have personally received comments that my disability made me “incompetent”’; that culturally and linguistically diverse academics were evaluated less favourably than white, western counterparts: ‘Other colleagues from cultural and linguistically diverse backgrounds regularly receive negatively biased data and discriminatory comments… comments that they were less intelligent than other staff… about their accents and needing to take ‘speech therapy’, and that age discrimination informed some SET responses: ‘I have experienced age-related bias on a few occasions’.

Impacts on mental health

When asked what impact SET might have on course/unit coordinators, the most common response related to adverse effects on mental health (n = 29), including comments that:

‘it ends up being harmful to staff well-being’, ‘it is a major stressor for academic staff that undermines their wellbeing’, ‘staff have been psychologically affected by student comments’, and SET are ‘psychologically harmful’.

‘academics feeling helpless and disheartened’, ‘paranoia’, ‘feeling sick’, ‘makes you feel inadequate’, ‘undue stress and emotional trauma’, and ‘distress, rumination, anxiety, and worry that the evaluation will impact future opportunities’.

‘can be devastating to a teacher’, ‘The impact on the teacher can be catastrophic’ …, ‘Trauma to the Course Convenor/teaching staff’, ‘It severely damages staff mental health’.

Career impacts

In addition to the harm SET comments can inflict upon academics, respondents indicated that low SET scores might negatively impact opportunities for tenure, academic promotion, and academic self-efficacy. Four respondents identified that harmful SET comments prompted academics to leave the profession. For example:

‘A professor I had as an undergrad who was amazing and so supportive … has quit academia because she was sick of the negative comments in SET… such a loss to the discipline’; ‘two older and very good lecturers that I know have left [the profession] because of the unwarranted abuse via SET’; and a ‘female academic is now leaving’.

Risk mitigation

The final theme emerging from thematic data analysis focused on the university strategy employed to mitigate the risk of SET associated harm. While most respondents could not identify a harm mitigation strategy, when described, it was often presented as haphazard and individually facilitated rather than systematically employed. A total of 14 leaders in learning and teaching described filtering:

‘out the insults before showing the feedback to colleagues’, or ‘review[ing] data, remov[ing] comments that may be discriminatory’, or scanning ‘for expletives and other ‘flagged’ phrases’, and ‘modifying’ inappropriate comments’.

‘None that I am aware of. Sporadically, we have been asked to nominate the SET data/responses for individual courses that we feel the Head of School should review before releasing them to the academic responsible… But this is patchy and does not always happen’.

SET contravene universities’ duty of care

Ten survey responses reflected that the implementation of SET transgresses universities’ ethical due diligence and harm mitigation, including descriptions of SET as:

‘bordering on bullying’, a ‘workplace psychosocial hazard’, and that ‘if SET were given a risk assessment or had to pass ethics, it would fail the do no harm test because some students use it as a means to personally harass academic staff through vindictive scoring and comments when they have done poorly in the course’.

‘no psychological safety’, advising that there ‘should have been a trigger warning or a help number’ and that the release of SET results require care-full scheduling and support, A BIG [sic] problem last year was that SET report was released to staff on a Friday at 6:00 pm.

Discussion

The role of SET as a means of top-down surveillance, with significant implications for academics’ career opportunities and navigation, emerged as a central theme within the data. This concern aligns with Kayas’ et al. (Citation2022) research, which found that top-down vertical surveillance, imbued with disciplinary procedures, involved university managers scrutinising academics through SET surveys. They further propose that management utilise the panopticon of power ‘to capture the knowledge of employee performance under a totalising instrumental rationalism that marginalises dissent and resistance’ (Kayas, Assimakopoulos, and Hines Citation2022, 2). This theorising is salient to our study, as external surveillance, when inhabited, can transform into internal surveillance, where people come to self-regulate themselves in response to perceived scrutiny and judgement by others and accept individual responsibility and self-remonstration even for systematic or external failings (Selwyn and Grant Citation2019). Evidence of such self-surveillance in several responses was made manifest in reports of individualised mental health impacts, with some academics choosing to leave the profession rather than withstand the further personal and emotional assault. In comparison, others took personal responsibility for mitigating the harm (to others) created by SET (by removing biases or comments that might cause harm). Yet, when systematic protections are not generally identified, self-surveillance and individualising harm mitigation processes might inadvertently invisibilise and propagate the harmful SET process.

Surveillance is often co-opted as using power to regulate, define, and control people to maintain the existing social order (Nakamura Citation2015). Yet, maintenance of the status quo is ethically problematic when the current order (and structure) of higher education is highly gendered, raced, and ableist. It appears, therefore, that SET, as a means of surveillance, serves to reproduce rather than diversify the structures and the actors of higher education. For example, structural and cultural factors negatively impact academic women’s career progression across all nations and disciplines, race significantly affects academic careers (Tsouroufli Citation2023), and people with disabilities experience persistent ableism, social exclusion, non-accommodating environments, and a lack of opportunities, leading to their significant under-representation within faculty (Lindsay and Fuentes Citation2022). Therefore, SET, with an inherent surveillance functionality (that seeks to maintain the existing social order of the institution), undermines universities’ cl/aims to support diversity and inclusion.

Furthermore, academic practice is not simply institutionally managed but increasingly state-mandated and controlled. Additionally, Lloyd and Wright-Brough (Citation2023) indicate the university/higher education sector employs SET, as evidenced in national and international awards within and beyond individual institutions, where comparisons are frequently made between institutions. It is perhaps unsurprising within this context that several research participants noted how SET operated as a performativity of Quality Assurance. Key phrases, such as ‘seen to be looking after and valuing the paying customer’ and ‘a compliance measure’, reflect the cynical perspective that the purpose of SET is ‘institutional peacocking’ (Yarrow and Johnston Citation2022) rather than ensuring quality learning and teaching.

Similarly, Sachs (Citation1994, 22) posited that notions of quality in higher education have dichotomised into ‘two distinct categories: quality assurance (QA) and quality improvement (QI)’ where ‘a tension has arisen … between quality as a measure for accountability and quality as a means for transformation and improvement’ (Rowlands Citation2012, 99). This discourse raises concerns about whether SET is employed to fulfil a public-facing governance agenda or functions to assess and actively improve learning and teaching. The concern is of significant ethical value as the academy must question whether SET's potential risks outweigh perceived benefits. Thus, higher education institutions must identify and actively mitigate all identified potential risks and harms, even if this means ceasing the administration of traditional SETs.

The findings also relate to the harmful role of SET that appears to operationalise microaggressions. Initially coined by Pierce et al. (Citation1977) to describe derogatory representations of Black Americans, the concept of microaggression has since expanded to encompass other marginalised groups, including women (Sue Citation2010). Microaggressions are subtle, commonplace, verbal and non-verbal actions that communicate negative messages toward a targeted group or person (Sue Citation2010). According to Sue (Citation2010), microaggressions can be categorised into microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations. Microassaults are categorised as explicit, conscious discrimination, which includes name-calling; microinsults exclude, negate, or nullify the thoughts or experiential reality of a person using subtle but persistent demeaning and disrespectful comments and behaviours, reflecting unconscious bias (Sue Citation2010) and microinvalidation occurs when participants’ experience or expertise is not acknowledged (Sue Citation2010).

SET can function to insult women academics and/or Black academics (of Colour) and/or those with a disability or who are older. It does so by having their learning and teaching design and facilitation deemed less valuable and legitimate in the academy than learning and teaching designed and delivered by white, male, able-bodied, and younger academics. The SET processes, which provide no recourse or opportunity for academics to respond to SET comments, essentially render marginalised academics without voice or contribution function as microinsults. In addition, denying an academic voice and ownership of their learning and teaching practice invalidates them by authorising academics to be spoken of and about but not with, thereby constituting microinvalidations.

Moreover, when evaluation outcomes impact marginalised academics’ career opportunities, SET-related microinvalidation is a matter of epistemic justice because when marginalised and minority peoples are excluded from or considered lesser in the academy, ‘the research questions they would raise are not asked, and the corresponding research is not undertaken’ (West Citation2006, 5). The silencing of marginalised academics within the SET process creates barriers to individuals’ career progress and might limit the development of new knowledge and ways of knowing. Therefore, the risk of harm from traditional SET processes is personal, epistemic, ubiquitous, and manifold.

Within this context, we posit that ethical considerations, using the lens of nonmaleficence (first, do no harm), are required when administering SET processes. We recognise a lack of consensus when describing what constitutes harm and anticipating risks, with harm usually referring to physically, morally, socially, or mentally injuring a person. The British Psychological Society (Citation2014) defines risk as the potential physical or psychological harm, discomfort, or stress to human participants, including risk to someone’s social status, values, beliefs, and relationships.

More specifically, the potential emotional, psychological, economic, and social risks and harms that SET processes inflict upon women and academics from other marginalised groups have been known for over 20 years, and as Ray (Citation2018) observes, ‘Usually when social scientists discover that a research instrument is biased, it is discontinued in favor of a more effective mechanism [sic]’ (139). Moreover, Ross (Citation2023) warns that although aggrieved academics could not take legal action against students for discriminatory comments, they could act against their employers for allowing them to affect their careers. Related to this, student scores or the numerical value attributed to academics and their courses (provided by the students who make abusive, personal, and biased evaluative comments, which are often removed) are not removed along with the comments. Yet, tenure and promotion decisions are usually made based on these scores. The (ad hoc) removal of abusive/biased comments might protect the academic from immediate harm. However, the process fails to mitigate the impact of the biased perception of students on academics’ career standing and opportunities. The removal of comments might, therefore, serve to protect the institution from litigation more than protecting academics from bearing witness to offensive comments that have the potential to harm them psychologically or emotionally.

It is seemingly paradoxical that SET continues to be administered by central university learning and teaching units at the behest and/or explicit permission of senior university executives, especially when the leaders of learning and teaching we surveyed both identified known concerns with SET evaluation instruments and processes employed and deployed strategy to mediate some of their potential harm. We provide below, therefore, a brief theorisation on the complex context and position of learning and teaching leadership within universities before recommending a framework that they, and all those involved in developing or administering SET, can use to adopt an ethical approach to assessment and evaluation of learning and teaching.

Universities operate within an era of neoliberalism, which is inextricably linked to resource constraints and free market principles, with a focus on measurement and reporting. Financial resource constraints, for example, are reflected in Australia, where there was growth in student enrolment from 138,666 in 1985 to 1,192,657 in 2011, followed by a decline of 28% in public funding per student within higher education between 1995 and 2005 (Rea Citation2012). Additionally, while there is no consensus on what constitutes learning and teaching excellence or how it can be facilitated or measured, most international higher education institutions must assess and report on student outcomes and experience (Chalmers and Tucker Citation2018). In Australia, for example, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) evaluates higher education institutions against the Higher Education Standards Framework (HESF) to ensure all students have opportunities to provide feedback on their educational experiences; that all teachers and supervisors have opportunities to review feedback on their teaching and are supported in enhancing these activities; and that the results of regular student feedback are used to mitigate future risks to the quality of the education (TEQSA (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency) Citation2021). Thus, within financial constraints, the requirement to meet an institution’s academic obligations SET is often employed because of its advantage of speed (in administration), anonymity and/or confidentiality (of response), and standardisation (for purposes of comparison between cohorts) to fulfil the institution’s reporting requirements (De-identified 2024).

Tensions for leaders of learning and teaching

Notwithstanding external imperatives that result in the continued deployment of SET, many leaders of learning and teaching experience tension between what they are required to administer and to support their colleagues. As Maistry (Citation2016) noted, academic leadership tensions occur between senior management and the academics who carry out the day-to-day work. This space ‘straddles the supervisor/foreman-like role of operationalising university policy and engaging “upward”’ with university structures (515). They continue that the tension becomes pronounced when there is a disjuncture between the belief systems of academic leaders and the ideology of the policies they must implement (Maistry Citation2016). In response, those required to operationalise strategies determined by senior executives are commonly referred to as ‘umbrella carriers’, a role that seeks to ‘protect colleagues from seemingly unnecessary and/or damaging initiatives and information from top management’ (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020, 124).

Similarly, Sims (Citation2003) uses the term ‘sandwiched middle’ to describe how leaders in higher education institutions are vulnerable to attacks from both above and below. Finally, Gjerde and Alvesson (Citation2020) found that the umbrella carrier regularly fends off the ‘shit’ coming from top management to protect the academics from being bombarded with excrement (132). Thus, a more productive understanding of the role of middle management in higher education institutions requires abandoning the managerialism/collegiate duality in favour of a dialectic where managerialism co-exists in tension with collegiality (Clegg and McAuley Citation2005).

The leaders’ position as ‘umbrella carriers’ (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020) appears to align with the survey data. The respondents identified their concern for SETs capacity to inflict harm, their ad hoc removal of abusive/biased comments, and recommendations of support provisions for academics, including when and how SET results are shared, are congruent with the analogy protecting academics from ‘being bombarded with excrement’ (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020, 132). It thus appears that the leaders required to administer and review set also seek to protect academics from potential harm caused by SET.

A proposed strategy to enhance SET processes

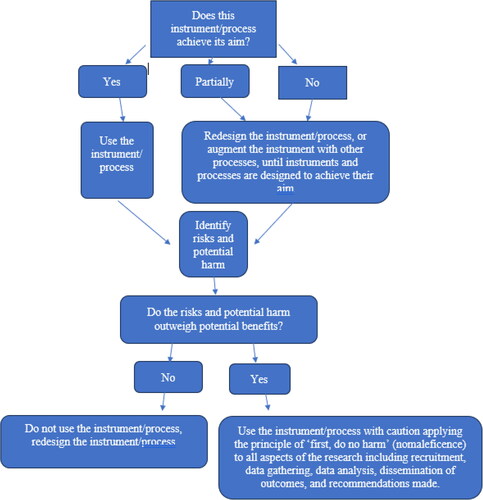

Within these ethical and potentially litigious contexts, and to provide a framework for leaders of learning and teaching to employ systematically, we recommend that universities radically reassess the use of SET beyond minor and ad hoc (and individualised) changes. Yet, this reassessment should not be limited to SET practice, as nonmaleficence is a fundamental principle upon which all processes and interactions should be based. To support such an evaluation, we have developed a decision-making tool (see ) to gauge the efficacy of all instruments and processes and assess the quality of learning, teaching design, and facilitation.

We posit that the decision-making tool could either dissuade universities from engaging in SET (requiring them to employ other processes or tools) or encourage them to use the SET instrument/process cautiously. This approach would mean applying the principle of ‘first, do no harm’ (nonmaleficence) to all aspects of the evaluative process, including recruitment, data gathering, data analysis, dissemination of outcomes, and recommendations.

Conclusion

SET processes aim to improve course quality, but research reveals bias and abuse in feedback. Despite this, the ethical implications of their emotional, psychological, and social impacts are understudied. In response, this paper reported on a research project which employed the ethical framework of nonmaleficence (‘first, do no harm’) to learn how leaders in learning and teaching perceive the function of SET and strategies to mitigate inherent biases within SET data.

The findings revealed learning and teaching leaders recognise SET's surveillance role, the presence of biases (gender, racial, cultural, ableism, ageism), and the emotional and career impacts on academics. Mitigation strategies were ad-hoc, failing to systematically address biases, causing significant harm, particularly to marginalised groups, resulting in stress, anxiety, and trauma. Participants explicitly noted that SET ‘can be devastating to a teacher’. While these findings confirm those from previous studies, new findings emerged within this study, signalling that implementing SET transgresses universities’ ethical due diligence and duty of care to employees.

Analysis showed that SET-induced external surveillance transforms into self-surveillance, causing mental health impacts and some academics to leave. Individual harm mitigation hides systemic issues, perpetuating harmful SET processes. SET often operationalises microaggressions, undermining universities’ diversity and inclusion claims. In response, we recommend universities radically reassess SET use by employing nonmaleficence as a fundamental principle upon which all university assessment processes and interactions ought to be based. We devised a decision-making tool for evaluating learning and teaching in higher education () to support academics in gauging the efficacy of all instruments and processes to assess the quality of learning, teaching design, and facilitation and to support the application of the principle of ‘first, do no harm’ (nonmaleficence) to all aspects of the evaluative process. Traditional ethics often prioritise participant wellbeing over the subjects of research or evaluation. The decision-making tool addresses this by incorporating concern for the subjects, including teaching academics evaluated through SET. Using this tool could transform SET administration and its significance in universities.

Future research

While not all student feedback is abusive, it is essential to note online trolling, cyber hate, and harassment, what Jane (Citation2006) calls ‘e-bile’, are on the rise, commonplace and almost expected in some other areas of mediated networked society. Thus, in keeping with the Zeitgeist, higher education institutions must remain cognisant of the severity of these issues that particularly frequently target marginalised groups. Accordingly, higher education institutions need to take this issue seriously and provide greater protection to keep up with this phenomenon that has bled into many aspects of everyday life. Thus, investigating any increase in online and anonymous abuse in SET and its relation to other types of cyberbullying – and any associated e-safety practices and protection of employees in different industries and sectors – is worthy of future research consideration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following co-researchers for their commitment and contributions to the project: Dr Melissa Sullivan, University of the Sunshine Coast; Professor Graham K. Brown, Charles Sturt University; Professor Janelle Wheat, Charles Sturt University; Associate Professor David Smith, Charles Sturt University; Dr Carol Quadrelli, University of Southern Queensland; Professor Kate Ames, Central Queensland University; Professor Steven Warburton, University of Newcastle; Professor Ruth Greenaway, Southern Cross University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bennett, S. K. 1982. “Student Perceptions of and Expectations for Male and Female Instructors: Evidence Relating to the Question of Gender Bias in Teaching Evaluation.” Journal of Educational Psychology 74 (2): 170–179. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.74.2.170.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2023. “Thematic Analysis.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by K. D. Norman, S. L. Yvonna, D. G. Michael, and S. C. Gaile, 385–402. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publishing.

- British Psychological Society. 2014. Association of Social Anthropologists. 2011. “Ethical Guidelines for Good Research Practice,” https://www.theasa.org/ downloads/ASA%20ethics%20guidelines%202011.pdf

- Buchanan, D., and I. Warwick. 2021. “First, Do No Harm: Using ‘Ethical Triage’ to Minimise Causing Harm When Undertaking Educational Research among Vulnerable Participants.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 45 (8): 1090–1103. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2021.1890702.

- Chalmers, D., and B. Tucker. 2018. “A National Strategy for Teaching Excellence – One University at a Time.” In Global Perspectives on Teaching Excellence: A New Era for Higher Education, edited by C. Broughan, G. Steventon and L. Clouder, 93–105. London: Rutledge. doi:10.4324/9781315211251-7.

- Clegg, S., and J. McAuley. 2005. “Conceptualising Middle Management in Higher Education: A Multifaceted Discourse.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 27 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1080/13600800500045786.

- Collini, S. 2012. What Are Universities for? London, UK: Penguin.

- Cone, C., L. M. Fox, M. Frankart, E. Kreys, D. R. Malcom, M. Mielczarek, and L. Lebovitz. 2022. “A Multicenter Study of Gender Bias in Student Evaluations of Teaching in Pharmacy Programs.” Currents in Pharmacy Teaching & Learning 14 (9): 1085–1090. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1877129722002003. doi:10.1016/j.cptl.2022.07.031.

- Cunningham, Samuel, Melinda Laundon, Abby Cathcart, Md Abul Bashar, and Richi Nayak. 2023. “First, Do No Harm’: Automated Detection of Abusive Comments in Student Evaluation of Teaching Surveys.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (3): 377–389. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2081668.

- Cunningham-Nelson, S., M. Baktashmotlagh, and W. Boles. 2019. “Visualizing Student Opinions through Text Analysis.” IEEE Transactions on Education 62 (4): 305–311. doi:10.1109/TE.2019.2924385.

- Gjerde, S., and M. Alvesson. 2020. “Sandwiched: Exploring Role and Identity of Middle Managers in the Genuine Middle.” Human Relations 73 (1): 124–151. doi:10.1177/0018726718823243.

- Heffernan, T. A. 2018. “Approaches to Career Development and Support for Sessional Academics in Higher Education.” International Journal for Academic Development 23 (4): 312–323. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2018.1510406.

- Heffernan, T. A. 2022a. “Sexism, Racism, Prejudice, and Bias: A Literature Review and Synthesis of Research Surrounding Student Evaluations of Courses and Teaching.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (1): 144–154. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1888075.

- Heffernan, T. A. 2022b. Bourdieu and Higher Education: Life in the Modern University. New York: Springer.

- Heffernan, T. A. 2023. “Abusive Comments in Student Evaluations of Courses and Teaching: The Attacks Women and Marginalised Academics Endure.” Higher Education 85 (1): 225–239. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00831-x.

- Jane, E. 2006. Misogyny Online: A Short (and Brutish) History. London: Sage.

- Johnson, R. 2000. “The Authority of the Student Evaluation Questionnaire.” Teaching in Higher Education 5 (4): 419–434. doi:10.1080/713699176.

- Kayas, O. J., C. Assimakopoulos, and T. Hines. 2022. “Student Evaluations of Teaching: Emerging Surveillance and Resistance.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1725875.

- Khazan, E., J. Borden, S. Johnson, and L. Greenshaw. 2019. “Examining Gender Bias in Student Evaluations of Teaching for Graduate Teaching Assistants.” NACTA Journal 64: 422–427.

- Kreitzer, R. J., and J. Sweet-Cushman. 2021. “Evaluating Student Evaluations of Teaching: A Review of Measurement and Equity Bias in SETs and Recommendations for Ethical Reform.” Journal of Academic Ethics 20 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1007/s10805-021-09400-w.

- Kwok, K., and J. Potter. 2022. “Gender Stereotyping in Student Perceptions of Teaching Excellence: Applying the Shifting Standards Theory.” Higher Education Research & Development 41 (7): 2201–2214. doi:10.1080/07294360.2021.2014411.

- Lindsay, S., and K. Fuentes. 2022. “It is Time to Address Ableism in Academia: A Systematic Review of the Experiences and Impact of Ableism among Faculty and Staff.” Disabilities 2 (2): 178–203. doi:10.3390/disabilities2020014.

- Lloyd, M., and F. Wright-Brough. 2023. “Setting out SET: A Situational Mapping of Student Evaluation of Teaching in Australian Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (6): 790–805. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2130169.

- Maistry, S. M. 2016. “Confronting the Neo-Liberal Brute: Reflections of a Higher Education Middle-Level Manager.” South African Journal of Higher Education 26 (3): 515–528. doi:10.20853/26-3-184.

- McCormack, C. 2005. “Reconceptualizing Student Evaluation of Teaching: An Ethical Framework for Changing Times.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 30 (5): 463–476. doi:10.1080/02602930500186925.

- Mitchell, K.,. M. W., and J. Martin. 2018. “Gender Bias in Student Evaluations.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51 (03): 648–652. doi:10.1017/S104909651800001X.

- Nakamura, L. 2015. “Afterword. Blaming, Shaming and the Feminization of Social Media.” In Feminist Surveillance Studies, edited by E. D. Rachel, and M. S. Amelia. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Pierce, C. M., J. V. Carew, D. Pierce-Gonzalez, and D. Wills. 1977. “An Experiment in Racism: TV Commercials.” Education and Urban Society 10 (1): 61–87. doi:10.1177/001312457701000105.

- Ray, V. 2018. “Is Gender Bias an Intended Feature of Teaching Evaluations?” Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2018/ 02/09/teaching-evaluations-are-often-used-confirm-worst-stereotypes-about-women-faculty

- Rea, J. 2012. “National Tertiary Education Union Written Submission to the Independent Inquiry to Insecure Work. http://www.nteu.org.au/library/view/id/2186

- Ross, J. 2023. “‘Universities Could Face Prosecution’ Over Student Evaluations: Psychosocial Harm Clauses in Workplace Safety Laws Elevate Administrators’ Mental Health Obligations, Expert Warns.” Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/universities-could-face-prosecution-over-student-evaluations

- Rowlands, J. 2012. “Accountability, Quality Assurance and Performativity: The Changing Role of the Academic Board.” Quality in Higher Education 18 (1): 97–110. doi:10.1080/13538322.2012.663551.

- Sachs, J. 1994. “Strange yet Compatible Bedfellows: Quality Assurance and Quality Improvement.” Australian Universities Review 37 (1): 22–25.

- Selwyn, J., and A. M. Grant. 2019. “Self-Regulation and Solution-Focused Thinking Mediate the Relationship between Self-Insight and Subjective Well-Being within a Goal-Focused Context: An Exploratory Study.” Cogent Psychology 6 (1): 1695413. doi:10.1080/23311908.2019.1695413.

- Sims, D. 2003. “Between the Milestones: A Narrative account of the Vulnerability of Middle Managers’ Storytelling.” Human Relations 56 (10): 1195–1211. doi:10.1177/00187267035610002.

- Spooren, P., B. Brockx, and D. Mortelmans. 2013. “On the Validity of Student Evaluation of Teaching: The State of the Art.” Review of Educational Research 83 (4): 598–642. doi:10.3102/0034654313496870.

- Sue, D., W. 2010. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- TEQSA (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency). 2021. Higher Education Framework Standards 2021. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/higher-education-standards-framework-2021

- Tsouroufli, M. 2023. “Migrant Academic/Sister Outsider? Feminist Solidarity Unsettled and Intersectional Politics Interrogated.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 25 (1): 1–14. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol25/iss1/2/.

- West, M., S. 2006. “AAUP Faculty Gender Equity Indicators.” American Association of University, 4–84. http://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/63396944-44BE-4ABA-9815-5792D93856F1/0/AAUPGenderEquityIndicators2006.pdf

- Yarrow, E., and K. Johnston. 2022. “Athena SWAN: “Institutional Peacocking” in the Neoliberal University.” Gender, Work & Organization 30 (3): 757–772. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/gwao.12941. doi:10.1111/gwao.12941.