Abstract

Feedback is a key factor for learning success and has therefore been widely studied in higher education. As feedback is a highly contextualized practice serving various learner needs, researchers have utilized a plethora of feedback designs in their intervention studies. This diversity in feedback conceptualizations and pedagogical designs often results in considerable variability of effect sizes in reviews and meta-analyses and thus reduces their explanatory power. To explore the breadth of possible design variants and contribute to a greater conceptual clarity in empirical studies, we conducted a scoping review of feedback interventions in higher education (n = 135). The scoping process revealed a rich variety of feedback practices and underscored the need to precisely describe feedback designs in primary studies. Moreover, the supplemental qualitative content analysis resulted in a comprehensive category system, consisting of seven main dimensions and 247 subcategories. With its hierarchical structure and guiding questions, this feedback taxonomy can serve as a valuable tool for researchers and educators when exploring and implementing different design options. Despite its comprehensive scope, the taxonomy exhibits gaps, notably with respect to emerging digital feedback practices. It should therefore be considered as a dynamic resource worth of further investigation.

Introduction

The central importance of feedback in higher education is reflected in the large number of studies about feedback. With an increasing number of primary studies, reviews and meta-analyses on the topic of feedback are becoming increasingly important (see e.g. van der Kleij, Adie, and Cumming Citation2019; Wisniewski, Zierer, and Hattie Citation2020; Alqassab et al. Citation2023; Chong and Lin Citation2024). The latter intend to provide researchers with an overview of the current state of research. However, the meta-analyses and reviews repeatedly show that the results of primary studies are by no means consistent, but rather exhibit large variances in effect sizes. One reason for this is seen in the different understandings of feedback in the individual studies, which are often not considered in depth (see e.g. Ruiz-Primo and Li Citation2013; Wisniewski, Zierer, and Hattie Citation2020). Crucially, though, this conceptual vagueness affects the comparability of the studies and the explanatory power of reviews. The present paper therefore undertakes a qualitative content-analytical scoping review to determine the conceptual diversity in pedagogical feedback designs that are utilized in intervention studies within higher education. It seeks to explore the breadth of possible design variants, to identify their central components and contribute to a greater conceptual clarity in the description of feedback practices in empirical studies.

Reviews and dimensions of pedagogical feedback designs

Given the complexity of the feedback construct, previous studies and reviews have mostly focused on selected facets of this complex phenomenon. For example, they dealt with the characteristics of the feedback message (Haughney, Wakeman, and Hart Citation2020), the required competences on the part of the learners (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Zhan Citation2022; Little et al. Citation2024) and teachers (Boud and Dawson Citation2023) as well as with interpersonal (Gravett and Carless Citation2024) and sociomaterial factors (Chong Citation2021, Citation2022; Gravett Citation2022). Lipnevich and Panadero (Citation2021) as well as Panadero and Lipnevich (Citation2022) acknowledged this complexity and attempted to merge previous feedback models in their so-called MISCA model. MISCA stands for the characteristics of the feedback message (M), the implementation (I), the characteristics of the learner or student (S), contextual variables (C) and the actions and interactions of the agents involved in the feedback process (A). However, these dimensions still need to be verified empirically (Panadero and Lipnevich Citation2022). Also, they require further details since each dimension can comprise numerous variants. To exemplify, even though Alqassab et al. (Citation2023) concentrated on one specific variant only, i.e. peer assessment design elements, they uncovered a wide range of design options. At the same time, the authors observed and criticized that the description of the didactic designs in the reviewed studies was often vague, which also hinders their replication.

To give another example, the SAGE taxonomy by Winstone et al. (Citation2017) focused on feedback recipience processes only. SAGE therein stands for self-appraisal (S), assessment literacy (A), goal-setting and self-regulation (G), as well as engagement and motivation (E). By contrast, Bearman et al.’s (Citation2014) ‘Assessment Design Framework’ takes a wider look and provides recommendations and resources for good assessment design (see also their website at www.assessmentdecisions.org). They distinguish between six dimensions, which are (1) purposes of assessment, (2) contexts of assessment, (3) learner outcomes, (4) tasks, (5) feedback processes and (6) interactions. In this framework, feedback is seen as one component of the assessment design. Several important principles are addressed, such as granting multiple, staged and iterative feedback opportunities and considering the modes and contents of feedback. However, these principles might be too general for those who seek explicit advice about pedagogical feedback designs.

In a more recent paper, Kaya-Capocci, O’Leary, and Costello (Citation2022) specifically looked at digital formative assessment in higher education, i.e. they set a focus on digital aspects and left out considerations about summative assessment. Altogether, they concentrated on the following formative assessment strategies: (1) clarifying and sharing learning outcomes and success criteria, (2) classroom discussion, questioning, and learning tasks, (3) feedback, (4) peer and self-assessment (Kaya-Capocci, O’Leary, and Costello Citation2022, 6). Their framework thus also includes other digital assessment strategies, not just digital feedback (Kaya-Capocci, O’Leary, and Costello Citation2022, 2). They organized these four strategies in a matrix that addressed three major functions of digital technologies: (a) sending and displaying, (b) processing and analyzing, (c) interactive environment (Kaya-Capocci, O’Leary, and Costello Citation2022, 6). However, they also acknowledged that their framework was not exhaustive and could be too reduced to represent ‘the complexity of the classroom’ (Kaya-Capocci, O’Leary, and Costello Citation2022, 10). Moreover, their framework partly appeared to replicate an outdated transmission paradigm of feedback sender and receiver, which has to be inspected critically from a contemporary perspective.

This brief literature synopsis demonstrates that most prior studies and reviews focused primarily on individual aspects of feedback designs. By contrast, there is a lack of studies that analyze the wide range of pedagogical feedback practices. We therefore intend to conduct a qualitative content-analytical scoping review to identify the breadth of pedagogical feedback interventions in the empirical literature while paying nuanced attention to concrete design features. The aim is to create a category system that facilitates a systematic and differentiated description of pedagogical feedback designs and could likewise inspire future research studies and teaching practices.

Research question and aims

The review is guided by the research question: ‘What characteristics of pedagogical feedback designs are described in intervention studies conducted in higher education?’. The aim is to obtain a comprehensive overview and more nuanced understanding of pedagogical feedback designs. Alongside this, we strive to identify frequently used design features and to uncover gaps to be addressed by future work.

Method

Scoping review

Scoping reviews are a suitable method for mapping the research landscape (Grant and Booth Citation2009, 101) and revealing the different conceptual understandings behind terms (Anderson et al. Citation2008, 7–8). In the rapidly evolving field of education, scoping reviews have therefore gained in popularity to elucidate the breadth and diversity of feedback conceptualizations. For instance, two recent ones concentrated on interventions to foster students’ feedback literacy (Little et al. Citation2024) and on teachers’ digital assessment literacy (Estaji, Banitalebi, and Brown Citation2024). However, no scoping review to date has identified the breadth of pedagogical feedback designs in existing research.

According to von Elm, Schreiber, and Haupt (Citation2019, 1), scoping reviews are suitable when the literature presents a very heterogeneous set of problems. In that respect, scoping reviews typically pursue exploratory questions to map the breadth of available research and identify key characteristics of a concept as well as potential gaps in the literature (Munn et al. Citation2022). These criteria apply to our research project. However, our aim is not to provide an evidence-based review of the current state of research; rather, we are interested in a qualitative insight into the respective feedback designs. Therefore, a qualitative content analysis (Gläser and Laudel Citation2010; Kuckartz Citation2016) was added to the ‘classic’ approach of scoping reviews (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005, 21; Anderson et al. Citation2008, 3) in order to capture the complexity and diversity of the feedback designs and subsequently map them into a taxonomy. This can help to provide an overview of feedback designs that have already been utilized in prior studies and those that deserve further examination. In essence, the content-analytical scoping review was based on the five steps of scoping reviews from Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005, 22), but step 4 ‘charting the data’ was expanded to include a qualitative content analysis:

Defining the research question

Identifying relevant studies

Selecting studies for review

Conducting a content analysis (coding of data material)

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

Article selection and analysis

In the scoping review, all studies were included that were peer-reviewed, published between January 2018 and July 2022 in English, freely accessible in the ERIC database, and that reported on empirical research about feedback in higher education settings.

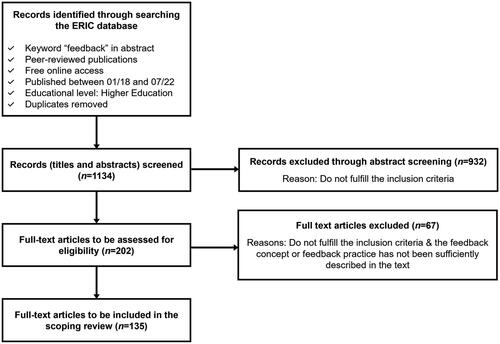

As shown in , 1,134 publications were obtained from the ERIC database. Their abstracts were screened in a next step to determine their actual relevance and fit to the inclusion criteria. This resulted in a substantial reduction to 202 studies. The methodological sections of these remaining articles were read in detail, which led to an additional criterion for exclusion: Articles in which the feedback practices were not sufficiently described had to be excluded. Overall, then 135 studies remained and were coded manually in the software program MAXQDA 2022, following the five steps of qualitative content analysis (based on Kuckartz Citation2016, 101–15, enriched with elements from Gläser and Laudel Citation2010):

Initial text work and extraction of relevant text passages

Development of main thematic categories

Coding of the main categories

Inductive determination of subcategories on the material

Coding of the overall material according to the differentiated category system

A coding unit was understood as a ‘meaning unit’, i.e. the text passage had to be self-contained and related to one of the main thematic categories (Mayring Citation2014, 51). A text passage could be coded several times if it addressed different dimensions (Kuckartz Citation2016, 41, 102–104). Both researchers were equally involved in all steps of study selection and analysis. They screened and coded 50% of the studies each and additionally conducted intercoder checks (5% of the studies, 98% agreement) as well as held regular research meetings to discuss their codings and agree on them consensually (Mayring Citation2014, 83; Kuckartz and Rädiker Citation2019, 268–69). The codes were then structured into different dimensions of feedback designs. In this process, a few deductively derived opposites were added to increase consistency and comprehensiveness. For instance, while the subcategory ‘trained’ appeared in the data for feedback recipients, its contrasting case ‘not trained’ did not, but would be needed by analogy and logic (Schreier Citation2012, 41, 84–86).

To identify common patterns, an additional descriptive-statistical analysis was carried out that resonates with a mixed-methods approach to qualitative content analysis. This allowed us to draw conclusions about the frequency distribution of the different (sub)categories (Mayring Citation2014, 41; Kuckartz and Rädiker Citation2019, 123–34).

Findings

The variety of pedagogical feedback designs that emerged from the qualitative content analysis can be divided into a total of seven main categories and 247 subcategories of different orders. This sheer number impressively illustrates the remarkable diversity of the feedback designs that was detected in the 135 studies. The most important results are presented below (see the online supplements for a detailed overview and list of studiesFootnote1).

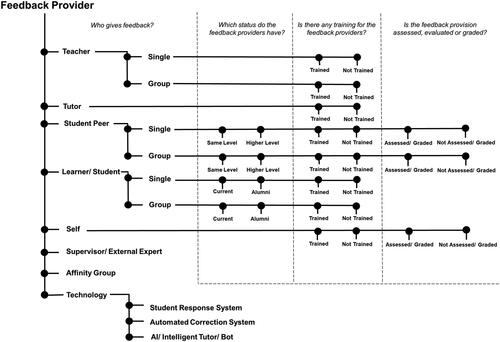

Who gives feedback (feedback providerFootnote2)?

The content analysis of the primary studies revealed a total of 8 different types of feedback providers (see first column in ): In more than half of the 135 analyzed studies, the feedback was given by the lecturerFootnote3 (n = 70; 52%). In 24% of the studies, feedback was provided by a peer group (n = 33) and in 18% by a single peer (n = 24). While self-feedback was practiced in 14% of the studies (n = 19), technologies such as student response systems (e.g. S45; S98), autocorrection programs (e.g. S84; S94; S113) or intelligent tutoring systems/AI bots (S109) served as feedback providers in 12% (n = 16) of the studies. In addition, feedback was also provided by learners (n = 8, 6%), tutors (n = 7; 5%), supervisors or external experts (n = 6; 4%), a lecturer group (n = 4; 3%), a student group (n = 1; 1%) or an affinity group (‘their target customers’ in S65) (n = 1; 1%).

The qualitative analysis of the papers revealed a rich diversity of pedagogical practices for each of these categories, which is not immediately evident from the terms themselves. For example, in peer scenarios, the feedback providers can have the ‘same’ (e.g. S41; S49) or a ‘higher’ level (e.g. S9; S50) with regard to study semester, knowledge, language proficiency or strategy use. Moreover, the feedback-providing students could be ‘current’ ones (e.g. S29; S75) or ‘alumni’ (e.g. S48; S54). Furthermore, feedback providers might have been ‘trained’ (e.g. S27; S100) or not (e.g. S25; S74). Notably, the training can be of various types and intensity, e.g. via screencast videos (e.g. S57), detailed guidelines and instructions (e.g. S54) or intensive training phases (e.g. S93). Another factor that is potentially very influential on the processes and outcomes of peer feedback is whether the students will be ‘assessed/graded’ (e.g. S30; S52) or ‘not assessed/graded’ (e.g. S106) for providing feedback. This list is certainly not complete, but it already shows the heterogeneity of feedback providers described in the literature.

In total, 8 subcategories of first order and 39 subcategories of lower orders emerged in relation to the main category feedback provider.

Who receives feedback (feedback receiver)?

Overall, 10 different types of feedback recipients were detected in the analyzed research literature: The most frequently named feedback receiver was the student or learner with 69% (n = 93), followed by the student peer (n = 40; 30%) and the self (n = 18; 13%). Less frequently, the student peer group (n = 13; 10%), learner groups (n = 9; 7%), the teacher (n = 6; 4%), a fictional person (n = 2; 1%), a teacher group (n = 1; 1%), external experts (n = 1; 1%) or study program organizers (n = 1; 1%) were the receivers of the feedback. In contrast to the feedback providers, the feedback recipients were often not further characterized. Even though many further characterizations are conceivable, several studies did not explicitly provide details. For example, while some studies refer to ‘training’ for feedback recipients (e.g. S11; S127), others do not explicitly address this issue. This vagueness points to the difficulty and necessity of clearly defining the characteristics of the feedback recipient. Accordingly, only 8 subdimensions were identified in the data for the 10 types of feedback recipients.

What is the feedback about (feedback content)?

In the analyzed literature, feedback related to three different objects: 77% of the feedback was concerned with products (n = 104), while only 8% focused on processes (n = 11) and 7% on course/university experiences (n = 9). In the remaining 8% of the studies, no conclusions could be drawn about the feedback object.

Deeper analysis showed that products can be divided into several subcategories. Firstly, they can be ‘written’, for example in the form of essays (e.g. S51; S64), translations (e.g. S90) or other written assignments (e.g. S120). Secondly, there can be various ‘multimedia’ products. These comprise, for instance, video-recorded speeches (e.g. S38), presentations (e.g. S95; S112) or e-portfolios (e.g. S96; S122). Thirdly, products can be ‘verbal’ contributions, such as oral presentations (e.g. S8) or oral interaction tasks (e.g. S20). Lastly, we classified ‘tests/quizzes’ as a separate subcategory for products, since they can appear in different modalities (written, verbal, multimodal etc.) (e.g. S36; S82).

Moreover, we identified a wide variety of assessment criteria or areas for which product feedback can be provided. These include ‘originality/creativity’ (e.g. S61; S65), ‘content’ (e.g. S91; S124), ‘language and style’ (e.g. S80; S88), ‘structure’ (e.g. S58; S66), ‘formalities’ (e.g. S57; S77) and ‘development’ (e.g. S96, who analyzed oral language development in e-portfolios).

Processes, in turn, can be ‘individual learning processes/task solving processes’ (e.g. S49), ‘teamwork processes’ (e.g. S6), or ‘classroom interactions’ (e.g. S75; S132). Individual processes can be assessed according to ‘attitudes/views (self-reflection)’ (e.g. S49), ‘learning activities/learning participation’ (e.g. S56; S76), and the ‘progress in learning’ (e.g. S76). To exemplify, teamwork processes can be analyzed based on a person’s ‘ability to work in a team’ and their ‘performance’ (for both see S6).

Lastly, feedback related to courses/university experience is subcategorized into ‘learning environment’ (e.g. S17; S135), ‘learning content’ (e.g. S17), ‘course design’ (e.g. S12; S33), ‘assessment/grading’ (e.g. S17; S54), and ‘communication and interaction/course management’ (e.g. S33; S135).

The analysis of the feedback content consequently led to three central dimensions, which were further differentiated into 37 subcategories.

What is the purpose of the feedback (feedback purpose)?

In terms of the objectives of the feedback processes, the analysis resulted in 11 different purposes: In 52% of the reviewed studies, the feedback aimed at correction (n = 70). In 46%, feedback was primarily intended to support learning (n = 62). Further objectives of the feedback processes were the promotion of feedback competencies (n = 14; 10%), the improvement of teaching/teaching skills (n = 12; 9%), motivation (n = 11; 8%), activation (n = 9; 7%), improvement of the (feedback) methodology/training (n = 7; 5%), increase of transparency/assessment (n = 4; 3%) or collection of information (n = 3; 2%), promotion of multiperspectivity (n = 3; 2%) and evaluation/accreditation of a degree program (n = 1, 1%). Sometimes, only one purpose was primary, but often several objectives were pursued.

Some of the major feedback purposes can be further subdivided into specific aims or intended outcomes. Correction, for example, can be done by ‘pointing out the wrong/correct answers’ (e.g. S1; S101), to ‘display misconceptions/promote error awareness’ (e.g. S54; S117), and to ‘increase quality/improve performance’ (e.g. S118; S130).

‘Support in problem solving and revision process’ (e.g. S120; S128), ‘promotion of learning success/comprehension’ (e.g. S2; S29), ‘learning from (your own or others’) mistakes’ (e.g. S7; S22), ‘promotion of self-regulation/learning behavior’ (e.g. S42; S102), ‘promotion of reflexivity/self-evaluation’ (e.g. S96; S99), and ‘gathering practical experience’ (e.g. S106) can be given as examples of learning support.

Subgoals of motivation or encouragement are ‘promotion of attitude/perception’ (e.g. S95), ‘promotion of motivation/encouragement’ (e.g. S56; S105), and ‘promotion of self-confidence’ (e.g. S37; S81). Furthermore, activation unfolds into ‘promotion of participation’ (e.g. S33; S53) or ‘promotion of student interaction’ (e.g. S19; S119). Lastly, the collection of information can be ‘about attitudes and motivations’ (e.g. S44), ‘about learners (strengths, weaknesses, strategies)’ (e.g. S53), and ‘for the joint construction of knowledge’ (e.g. S19).

All in all, the analysis of the objectives pursued with the feedback resulted in 11 first-order and 17 second-order subcategories.

In what way(s) and how is the feedback exchanged (feedback medium and mode)?

Overall, three main types of how feedback was exchanged were identified: 82% of all studies integrated written/visual feedback (n = 111), 37% used audio-visual/multimodal ways to give feedback (n = 50), whereas oral/audio feedback was practiced in only 7% of the analyzed studies (n = 9). These categories again unfold into several subcategories.

For instance, written/visual feedback can be given in a ‘paper-based’ manner on the task solution/document (e.g. S63; S91) or via a separate document/rubric (e.g. S100; S132), but it can also be distributed ‘electronically’ via email (e.g. S31; S92) or in form of (web-based) electronic file (e.g. S61; S107). Other kinds of written feedback are ‘quizzes/surveys’ (electronic (e.g. S45; S69) or paper-based (e.g. S36; S62)), ‘postings/comments’ on social media (e.g. S52), in blogs/e-portfolios (e.g. S38; S96) or in online forums (e.g. S2; S22). Additionally, ‘specialized software’ has been utilized, such as autocorrection programs (e.g. S4; S94), evaluation/assessment software (e.g. S34; S85) or tutoring software (e.g. S11).

In the analyzed studies, oral/auditory feedback was mainly given via ‘voice mail/audio recordings’ on a learning platform (e.g. S2; S99), in an instant messenger (e.g. S92; S116) or as an e-mail attachment (e.g. S102). In one study, feedback was given via ‘bug-in-ear technology’ to provide in-process feedback during teaching performance (e.g. S47).

Audio-visual/multimodal feedback could be exchanged in real-time in a ‘physical meeting’ in form of personal (e.g. S46; S78) or group conversations (e.g. S19; S57). An alternative is a (asynchronous) ‘recorded video message’ (e.g. S60; S80).

Typically, the different feedback media correlate with a certain manner of feedback provision, especially regarding the feedback timing, i.e. whether it occurs ‘asynchronously’ (e.g. S23; S79) and/or ‘synchronously’ (e.g. S69; S98). However, we also found design dimensions that can be arranged by the educator, for example whether the feedback exchange is conducted in an ‘anonymous’ (e.g. S27; S29) or ‘non-anonymous’ way (e.g. S38; S57). Moreover, the feedback provision can be ‘personalized’ (e.g. S54; S122) or ‘standardized’ (e.g. S83; S108) to different degrees. The personalized or standardized feedback exchange might be performed within a ‘private space’ (e.g. S80; S130), an ‘extended private space’ (with the teacher or mentor monitoring and/or directing the feedback exchange in peer groups) (e.g. S16; S106), or they might occur in a ‘public sphere’, e.g. when feedback is communicated within the entire classroom or even a wider public (e.g. S18; S119).

Furthermore, the manner of feedback provision includes two additional subdimensions. One is whether the feedback is ‘criteria-focused’ (e.g. S51; S116) or ‘not criteria-focused’ (e.g. S39; S106). The other one is whether the feedback is communicated in an ‘implicit/indirect’ (e.g. S64; S83) or ‘explicit/direct’ way (e.g. S46; S62).

Altogether, the 52 subdimensions for the three main forms of feedback show how diverse the feedback media and feedback modes can be in practice.

When and how often is feedback exchanged (feedback timing and frequency)?

In terms of feedback timing, two main dimensions can be distinguished: In 81% of the analyzed studies, the feedback was exchanged in a formative manner (n = 109), while 17% utilized summative feedback (n = 23). In 7% (n = 10) of the studies, a categorization as formative or summative was not possible due to a lack of detail provided. For both options, finer distinctions can be made, though. Basically, feedback could be given ‘simultaneously’ during a task or test (e.g. S47), ‘immediately afterwards’ (e.g. S69) or in a ‘delayed’ manner (e.g. S101). As a gradable phenomenon, the categorizations can be imagined as being placed on a scale, especially with regard to the enactment of ‘delayed’ feedback: Delayed feedback can be given, e.g. a few days later (e.g. S47: 3 days), a few weeks later (e.g. S29: 2 weeks) or even much later (e.g. S6: mid-semester).

Moreover, each of these feedback practices can happen once or several times. While in 21% of the studies feedback was only given once, 21% exchanged feedback more than five times (see ).

Table 1. Feedback frequency.

In sum, the analysis showed that the two main subcategories can be split into 42 further dimensions.

What roles does the feedback recipient play in the process (feedback interactions)?

This category plays a decisive role in the pedagogical planning of feedback processes. It is about the feedback interactions that precede the feedback exchange or occur afterwards. In 26% of the studies (n = 35), no conclusions could be drawn about the role of the feedback recipient (see above). In the other studies (n = 100), the role was specified with at least one feature. In that regard, three different feedback interaction phases were identified.

First, in the initiation step, in 7% of the studies, feedback was given without prior request, so the feedback recipient played a ‘passive’ role (n = 9) (e.g. S120; S134). In 4% of the analyzed studies, recipients adopted a ‘proactive’ role, actively asking for feedback (n = 6) (e.g. S17; S23). Finally, in three studies, the feedback recipient was allowed to ignore it or sign out, which is understood as a ‘passive-active’ situation (2%) (e.g. S51; S63).

Second, in the communication phase, there were several options for interactions between feedback providers and recipients. In 4% of the studies, there was no communication about the feedback (‘unidirectional’, n = 6; e.g. S119). If feedback providers had the chance to give an explanation about their produced feedback, this was called ‘statement’ in the feedback taxonomy (e.g. S32; S114). If the feedback recipients were required to (or voluntarily) provide(d) a reflection or comment about the received feedback, the ‘reflection’ dimension was coded (e.g. S90; S107). As we see, the aspect of voluntariness and volition should be considered in this phase as well. Moreover, the possibilities for further interactions between the participants varied. For example, ‘follow-up questions or queries’ were sometimes allowed (e.g. S54; S115), ‘subsequent discussions of the feedback’ were described (e.g. S48; S53), and in some studies, ‘feedback on the feedback’ was given (e.g. S54; S113).

Third, as related to the revision phase, a feedback-based revision was ‘obligatory/required’ in 26% of the studies (n = 25), while it occurred on a ‘voluntary’ basis in 17% (n = 23). Only 2% of the studies precluded the option of revision (n = 3).

In terms of feedback interaction, three central subcategories were thus identified, which can be broken down into 12 further dimensions.

Follow-up analysis: frequent feedback design patterns

The top ranked subcategories from above might already hint at common patterns in the data. To investigate their actual co-occurrences in the studies, we utilized MAXQDA’s code relations and code map functions. Most frequently (n = 67), feedback was provided by an individual teacher to a single student on their written products (n = 40) in a criteria-focused manner (n = 29) to enhance learning success (n = 27) and improve performance (n = 21). Feedback on language (n = 22) and content (n = 15) were typically focused on in these scenarios, and revisions were often required (n = 30). However, peer feedback was additionally included in n = 17 cases, and self-feedback in n = 8 cases. In n = 14 of these studies, there also was a personal discussion of the feedback, with learners being allowed to ask questions about the received feedback (n = 11) and/or to discuss it in a bi-/multidirectional manner (n = 9). Interestingly, teacher-to-student feedback was still most commonly paper-based (n = 25), either on the task sheet (n = 19) or a separate document (n = 6). Also, the feedback frequencies varied, with only one feedback event in n = 12 cases, but more than five in n = 17 others. Beyond this, a rich diversity of feedback designs with differing frequencies became obvious, as will be discussed further below.

Discussion

Response to research question

Research on feedback is flourishing and has led to an increasing diversity of pedagogical designs that are used in teaching practice and in intervention studies. Our aim was to describe the characteristics of pedagogical feedback designs as comprehensively as possible based on a scoping review of intervention studies that were conducted in higher education and published between 2018 and 2022. Through a qualitative content analysis of 135 studies, we arrived at seven major dimensions that appear to be crucial for the design of feedback scenarios: (1) feedback provider, (2) feedback recipient, (3) feedback content, (4) feedback purpose, (5) feedback medium/mode, (6) feedback timing/frequency, (7) feedback interactions/roles.

These unfolded into 247 subcategories, which illustrates the tremendous variety of pedagogical designs that is often hidden behind the umbrella term ‘feedback’. At the same time, this elucidates the importance of presenting one’s own understanding of feedback and the resultant feedback practices in a nuanced manner. However, several of the reviewed studies did not provide details about the pedagogical design for the seven main categories that we identified in our analysis. This information would be crucial, though, to heighten the methodological transparency, comparability, and replicability of the single studies. Likewise, differences in pedagogical design, e.g. in terms of prior feedback training and the exact peer feedback procedures (cf. Alqassab et al. Citation2023), have implications on the outcomes of the studies, on systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The same applies to potential discrepancies in students’, teachers’ and researchers’ understanding of ‘feedback’, which can vary greatly and affect feedback processes and empirical findings substantially (Little et al. Citation2024, 48). Moreover, it should be noted that several interventional studies resorted to multiple pedagogical feedback designs, leading to further complexity when researchers try to isolate the effects of different variables.

Through the additional frequency analyses that we performed, we observed a predominance of traditional feedback scenarios in which feedback was unidirectionally provided by a teacher to a student on a written product, often without further interactions. While pedagogical practice is foregrounding dialogic feedback models and proactive learner roles (see e.g. the review by van der Kleij, Adie, and Cumming Citation2019), interventional studies in higher education do not yet seem to fully mirror this shift in feedback conceptualizations (e.g. only 16 studies met the inclusion criteria for interventional studies that foster student feedback literacy in the review by Little et al. Citation2024). Implications for pedagogical practice and research will therefore be discussed below, following a brief methodological reflection.

Methodological reflection

Despite the comprehensive scope of our review, our detailed analysis of the main categories and subcategories revealed that not all existing forms of feedback were covered. One example is feedback in videoconferences, which was almost non-existent in the analyzed studies (only as a basis for analyzing corrective feedback in S75). This probably emanates from the limited time frame of the surveyed studies, as the popularity of videoconferences for feedback purposes has increased in the recent past, not the least since the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g. Brück-Hübner Citation2022, Citation2023). Similarly, feedback in virtual and augmented reality contexts and via generative AI were not yet a prominent part of the reviewed studies, but their growing relevance is clearly discernible (see e.g. the advance online publications in the journal Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education in 2024). Moreover, papers published in databases other than ERIC were omitted from the present review. Therefore, despite its comprehensive scope, this review does not claim to be exhaustive (for a more detailed methodological reflection see Brück-Hübner and Schluer Citation2023).

In addition, it should be noted that many feedback designs cannot be clearly or exclusively assigned to one category. For example, there are studies in which both lecturers and peers give feedback to students (e.g. S41) or where feedback is provided for different purposes (e.g. S87). In several studies, this resulted in multiple codings of individual categories. For each category, we therefore calculated the percentages separately based on the overall number of studies (n = 135).

Implications for empirical research and pedagogical practice

The category system and its guiding questions can assist researchers in composing precise descriptions of the pedagogical feedback designs that they intend to adopt in their interventional studies (cf. Brück-Hübner and Schluer Citation2023, 146–47). Moreover, it can serve as a source of inspiration for teachers and teacher educators to explore and implement a greater variety of feedback practices in a pedagogically driven manner. To this end, we created an interactive website based on the feedback design features that we identified in this scoping review of empirical research (Schluer Citation2024). The resultant feedback map or taxonomy is to be understood as a continually evolving resource and also incorporates the gaps found in the surveyed research (e.g. videoconference feedback and AI feedback). It is currently utilized in curriculum planning courses and workshops in higher education to foster pre- and in-service teachers’ feedback literacy (cf. Boud and Dawson Citation2023). The ongoing discussion of feedback designs with practitioners is an important, albeit optional, step of scoping reviews according to Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). It likewise resonates with models of dynamic feedback literacies and continuous professional development. For example, the tentative model by Schluer (Citation2022, 238–50) outlines the knowledge, attitudes and skills that are needed to adapt teaching and learning practices in light of new developments. Crucially, it includes an element of critical reflection as a central catalyst for adjusting or redesigning feedback processes. The model thus addresses several meta-competencies that are essential for continuously reconsidering existing practices and reflecting on innovations. In that respect, the feedback taxonomy derived from our scoping review helps to navigate the diversity of feedback designs.

Conclusion

Our findings clearly illustrate the wide variety of feedback practices and understandings that can be found in the research literature. Despite our comprehensive review, there are gaps in the developed category system. These could be closed, for example, through the additional integration of further studies, reviews and meta-analyses, or dialogues with practitioners. However, due to the constant further development of feedback designs (e.g. the increasing importance of AI), it can be assumed that a complete review of all pedagogical feedback designs is impossible. Every taxonomy of feedback designs should therefore be considered as open-ended, dynamic and in need of constant critical re-examination. In any case, this scoping review illustrates how important it is to precisely describe the underlying conceptualization of feedback in empirical studies and to also address and reflect on the implications that these differences in feedback designs have on systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In that respect, the resultant feedback taxonomy can assist researchers in investigating feedback as a situated practice while paying close attention to the multifaceted factors inherent in any pedagogical design (see e.g. Chong Citation2021 and Gravett Citation2022 on feedback as sociomaterial practice). Finally, it can inspire and guide teachers to explore a variety of pedagogical options and incorporate feedback processes more systematically into their curriculum planning and task design.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (59.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (50.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Please note that the reviewed studies are numbered in the results section (e.g. S18; S45), while the full reference details can be found in the online supplement.

2 The subcategories of the feedback providers were named based on the respective relationship with the feedback recipient (e.g. ‘lecturer’ feedback is feedback given from lecturers to students, or ‘single peer feedback’ is feedback given by a single student to another student).

3 Subcategories of first order are italicized, whereas subcategories of lower orders are placed within quotation marks.

References

- Alqassab, M., J.-W. Strijbos, E. Panadero, J. Fernández Ruiz, M. Warrens, and J. To. 2023. “A Systematic Review of Peer Assessment Design Elements.” Educational Psychology Review 35 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1007/s10648-023-09723-7.

- Anderson, S., P. Allen, S. Peckham, and N. Goodwin. 2008. “Asking the Right Questions: Scoping Studies in the Commissioning of Research on the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services.” Health Research Policy and Systems 6 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-6-7.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Bearman, M., P. Dawson, D. Boud, M. Hall, S. Bennett, E. Molloy, and G. Joughin. 2014. “Guide to the Assessment Design Decisions Framework.” Accessed July 4, 2024. http://www.assessmentdecisions.org/guide.

- Boud, D., and P. Dawson. 2023. “What Feedback Literate Teachers Do: An Empirically-Derived Competency Framework.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (2): 158–171. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1910928.

- Brück-Hübner, A. 2022. “Feedback digital: Besonderheiten und Herausforderungen von digitalen Feedbackprozessen in der Hochschullehre.” Paper presented at the Junges Forum für Medien und Hochschulentwicklung (JFMH), Philipps Universität Marburg.

- Brück-Hübner, A. 2023. “Was kennzeichnet ‘gutes’ digitales Feedback? Eine empirische Studie zu den Gelingensbedingungen digitaler Feedbackprozesse in der Hochschullehre aus Studierendenperspektive.” In Kompetenzen im Digitalen Lehr- und Lernraum an Hochschulen, edited by H. Rundnagel and K. Hombach, 103–119. Bielefeld: WBV.

- Brück-Hübner, A., and J. Schluer. 2023. “Was meinst du eigentlich, wenn du von ‘Feedback’ sprichst? Chancen und Grenzen qualitativ-inhaltsanalytischer Scope-Reviews zur Herausarbeitung von Taxonomien zur Beschreibung didaktischer Szenarien am Beispiel ‘Feedback’.” MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung 54: 125–166. doi:10.21240/mpaed/54/2023.11.29.X.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Chong, S. W. 2021. “Reconsidering Student Feedback Literacy from an Ecological Perspective.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1730765.

- Chong, S. W. 2022. “The Role of Feedback Literacy in Written Corrective Feedback Research: From Feedback Information to Feedback Ecology.” Cogent Education 9 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2022.2082120.

- Chong, S. W., and T. Lin. 2024. “Feedback Practices in Journal Peer-Review: A Systematic Literature Review.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 49 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2164757.

- Estaji, M., Z. Banitalebi, and G. T. L. Brown. 2024. “The Key Competencies and Components of Teacher Assessment Literacy in Digital Environments: A Scoping Review.” Teaching and Teacher Education 141: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2024.104497.

- Gläser, J., and G. Laudel. 2010. Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente rekonstruierender Untersuchungen. 4th ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Gravett, K. 2022. “Feedback Literacies as Sociomaterial Practice.” Critical Studies in Education 63 (2): 261–274. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1747099.

- Gravett, K., and D. Carless. 2024. “Feedback Literacy-as-Event: Relationality, Space and Temporality in Feedback Encounters.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 49 (2): 142–153. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2189162.

- Haughney, K., S. Wakeman, and L. Hart. 2020. “Quality of Feedback in Higher Education: A Review of Literature.” Education Sciences 10 (3): 1–15. doi:10.3390/educsci10030060.

- Kaya-Capocci, S., M. O’Leary, and E. Costello. 2022. “Towards a Framework to Support the Implementation of Digital Formative Assessment in Higher Education.” Education Sciences 12 (11): 1–12. doi:10.3390/educsci12110823.

- Kuckartz, U. 2016. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. 3rd ed. Weinheim, Basel: Juventa.

- Kuckartz, U., and S. Rädiker. 2019. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Lipnevich, A. A., and E. Panadero. 2021. “A Review of Feedback Models and Theories: Descriptions, Definitions, and Conclusions.” Frontiers in Education 6: 1–29. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.720195.

- Little, T., P. Dawson, D. Boud, and J. Tai. 2024. “Can Students’ Feedback Literacy Be Improved? A Scoping Review of Interventions.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 49 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2177613.

- Mayring, P. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173.

- Munn, Z., D. Pollock, H. Khalil, L. Alexander, P. Mclnerney, C. M. Godfrey, M. Peters, and A. C. Tricco. 2022. “What Are Scoping Reviews? Providing a Formal Definition of Scoping Reviews as a Type of Evidence Synthesis.” JBI Evidence Synthesis 20 (4): 950–952. doi:10.11124/JBIES-21-00483.

- Panadero, E., and A. A. Lipnevich. 2022. “A Review of Feedback Models and Typologies: Towards an Integrative Model of Feedback Elements.” Educational Research Review 35: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100416.

- Ruiz-Primo, M. A., and M. Li. 2013. “Examining Formative Feedback in the Classroom Context: New Research Perspectives.” In SAGE Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, edited by James McMillan, 215–232. California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Schluer, J. 2022. Digital Feedback Methods. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto.

- Schluer, J. 2024. “Feedback Taxonomy (Interactive Web Version).” Accessed July 4, 2024. https://tinyurl.com/FeedbackTaxonomyEN/.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. London: Sage.

- van der Kleij, F. M., L. E. Adie, and J. J. Cumming. 2019. “A Meta-Review of the Student Role in Feedback.” International Journal of Educational Research 98: 303–323. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2019.09.005.

- von Elm, E., G. Schreiber, and C. Haupt. 2019. “Methodische Anleitung für Scoping Reviews (JBI-Methodologie).” Zeitschrift Für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 143: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.zefq.2019.05.004.

- Winstone, N., R. A. Nash, M. Parker, and J. Rowntree. 2017. “Supporting Learners’ Agentic Engagement with Feedback: A Systematic Review and a Taxonomy of Recipience Processes.” Educational Psychologist 52 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1080/00461520.2016.1207538.

- Wisniewski, B., K. Zierer, and J. Hattie. 2020. “The Power of Feedback Revisited: A Meta-Analysis of Educational Feedback Research.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1–14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087.

- Zhan, Y. 2022. “Developing and Validating a Student Feedback Literacy Scale.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (7): 1087–1100. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.2001430.