ABSTRACT

There is a conspicuous silence about the role of religion and spirituality in social work in Uganda, yet they are critical components in the lives of social workers and their clients. The authors’ collective experience of social work education in Uganda, South Africa, Sweden, the UK, and Australia affirmed to an absence of content on religion and spirituality in social work education. Most universities in Uganda incorporate little content on spirituality resulting in graduates ill-equipped to handle spiritually-related issues with their clients and communities. Authors conducted a content analysis of the narratives in their PhD theses to explore the inextricable connection between spirituality and social work practice in Uganda. From the common findings, the authors conceptualise an African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory and a reflective tool for social workers in education and practice. The paper draws on lessons from research arguing for the incorporation of indigenous knowledge and African spirituality to inform the social work curriculum in Uganda.

Introduction

There has been continuing discourse on the role of spirituality and religion in social work with successive African scholars making a case for spiritually sensitive practice and the inclusion of spirituality in the social work curriculum (Bhagwan, Citation2010; Ebimgbo et al., Citation2017; Mabvurira & Nyanguru, Citation2013). We concur with Gray’s (Citation2008) analysis of where the contemporary interest in spirituality is stemming from:

The failures of modernity and its depersonalising and alienating effects through the detraditionalisation and secularisation of society; the rise of science, rationality, the professions, and industrial and technological progress; and the decline in religion. Social work mirrors this process in that it has worked vigorously to shake off its religious, moralistic beginnings, and to embrace the secular trappings of professionalism in the process increasingly embracing highly individualistic values and scientific explanations of reality (p. 192).

Indeed, calls for spiritually sensitive social work education and practice fit Gray’s (Citation2008) conceptualisation of secular social work. Given the secular nature of Western social work imported to Africa and the slow progress of indigenisation, the curriculum rarely includes content on religion and spirituality, spiritual functioning and assessment, and spiritual care plans (Bhagwan, Citation2010; Ebimgbo et al., Citation2017; Mabvurira & Nyanguru, Citation2013; Twikirize, Citation2014). Bhagwan’s (Citation2010) study of South African universities found social work students, who described themselves as religious or spiritual, expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of content on spirituality in the social work curriculum. The gap the authors seek to address is related to the lack of indigenous theories, concepts, and models generated from local experiences and voices to inform what may constitute a culturally appropriate and spiritually sensitive social work education and practice (Mabvurira, Citation2020; Twikirize, Citation2014). Spirituality in social work remains an under-researched area and the very limited empirical work to avoid repetition of research in Uganda suggests little integration of religion and spirituality in social work even in Christian universities teaching social work (Owor, Citation2004). The academic amnesia around spirituality in African social work has resulted in very limited information about the topic accessible for academic and practice use yet spirituality remains an important part of people’s lives (Mabvurira & Nyanguru, Citation2013).

This paper brings issues relating to religion and spirituality in Ugandan social work to the fore, drawing on three PhD studies. It begins with a discussion of religion and spirituality and the impact of colonisation. We then introduce the individually conducted PhD studies examining religion and spirituality for male survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, older women in self-organised collective care groups, and caregivers and stakeholders in aged-care provision in rural Uganda. We examine arising common themes around religion and spirituality that we theorise into what may constitute an African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory and reflective tool for social workers for inclusion in social work education and practice. This paper does not go in-depth into the pre-colonisation foundations of African Traditional Religion as scholars Doyle (Citation2007), Chepkwony (Citation2007) have covered this topic extensively.

Difference between religion and spirituality

Religion and spirituality concern human relationship with a transcendent higher power or Supreme Being. They offer purpose, moral codes, and explanations of ultimate reality. However, spirituality differs from religion when uncoupled from institutionalised religious denominations. A person can be spiritual without being religious (Knoetze, Citation2019). For Canda et al. (Citation2019) religion is a social institution. Furman et al. (Citation2004) noted a movement from religion to spirituality reflected people’s desire to release their spiritual narratives from controlling religious structures and authorities because spirituality is linked more to the search for connection and meaning. The spirituality movement combined an eclectic mix of beliefs and practices from diverse sources, including Western and Eastern religions. Modernist dualist boundaries have been challenged for example, Esoteric New Age spirituality, combined with ecofeminism, goddess worship, have been identified in esoteric faith traditions like Taoism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism (Levin, Citation2021).

As Van Niekerk (Citation2018) explained:

In contrast to … forms of religious organisation, the ‘new’ spirituality is not institutionalised and can therefore appear to be disorganised, though it does have its own inner logic. Separated from the constraints of religion, it takes on a much wider meaning, to the extent that it eventually becomes a very broad and loose concept that is difficult to define. Religion, on the contrary, becomes more narrowly conceived, while spirituality is seen to relate to the sacred aspects of life and the universe, freed from the constraints of compulsory practice and physical location (pp. 6-7).

Gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, religious or spiritual perspectives, and socioeconomic status are among other factors shaping people’s diverse spiritual experiences (Canda et al., Citation2019). In fact, spirituality transcends religion and for some, spirituality is a way of life as seen in African spirituality. Knoetze (Citation2019) defined African spirituality as ‘a holistic concept that stemmed from the historical, cultural and religious heritage of Africa, and includes among others, folktales, beliefs, rituals and culture’ (p. 1). It encompasses proverbs, names of people and places, sacred places, customs, festivals, ceremonies, norms and values passed across generations. Expressed as Obuntu in Uganda or Ubuntu in Southern Africa, it encompasses African philosophical beliefs and values surrounding the interconnectedness between people and the natural environment, collectiveness, community, and caring (Mugumbate & Chereni, Citation2019; Tusasiirwe, Citation2020, Citation2021). These values exert a strong influence on African people’s identity, view of the world, and interactions with others and their environment. African spiritual beliefs shape the way people dress, their life decisions, such as marriage choices and close relationships. They translate into rituals and cultural practices around health, sickness, death, inheritance, and gender role distribution. African spirituality involves ancestor remembrance of the interconnectedness between the living and the dead (Masango, Citation2006). People consult and honour them through prayers and ceremonies. Spiritual cleansing and prayer are healing practices that promote harmony with ancestors. The principles of holism and non-dualism in African spirituality emphasise the interconnections between the physical and spiritual, visible and invisible, and the living and the dead (Knoetze, Citation2019). The family is central in African spirituality and distributes reciprocal duties, tasks, and responsibilities according to positional status in the kinship system. While older people are revered sources of wisdom in African culture, they are also among the most vulnerable groups in African society, due to the weakening of the traditional extended family system. Following the influence of modernisation, some Africans adopted the colonisers’ lens through which they regarded African spiritual practices, like traditional healing, as barbaric and a violation of human rights (Masango, Citation2006).

Colonisation, religion, and spirituality in Uganda

Pre-colonisation, the supreme God was named differently in various cultures. The Jopadhola of Eastern Uganda refer to the omnipotent God as Were. In Western Uganda, the Cwezi-kubandwa religion was most prominent in Bunyoro Kingdom (Doyle, Citation2007). In Central Uganda, the Baganda refer to the supreme creator as Katonda – the father of gods. There are various gods (balubaale) who are perceived to be guardians of nature. For example, Musisi is responsible for earthquakes, Mukasa for the lake, Kibuuka is the god of war, Walumbe is for sickness and death, Nagaddya for marriage and harvest, Nabuzaana for obstetrics. Each god has a shrine and a priestess who communicates with the Guardian spirit. Spirituality was also characterised by the African cosmology, where people recognised the presence of local spirits in every local scenery like the lakes, forests, rocks, mountains, plants and natural occurrences like rainfall, drought, earthquakes (Chepkwony, Citation2007). There was and is a belief in life and death and the communication to ancestors through omens, divination and dreams. Other sacred religious objects included drums, spears, baskets, and attires.

The colonial era between 1894 and 1962 witnessed the imposition of Western religious beliefs, social structures, and political institutions on Ugandan societies (Okoth, Citation1992). The arrival of Christian and Muslim missionaries also undermined traditional rulers by granting missionaries considerable power to establish Uganda as a British protectorate (White, Citation1999). This forced traditional rulers to align with Protestantism, Catholicism, or Islam to maintain their political and cultural influence and relevance (Rubongoya, Citation2007). The harmony between western Christianity and ATR to the present was tactfully knitted by the association of ATR rituals with the bible, for example, harvest thanksgiving, music, tithing, and the common values of peace, love, and brotherhood. Moreover, the elements of prophecy, temples (places of worship), singing, initiation and dancing are evident in both religions. The Kabakas (kings) of Buganda donated strategic land on the seven hills in Kampala city to the Anglican, Catholic and Islam faiths. This is the land that has traditional religious and cultural significance under the management of the kingdom (Mande, Citation1996). This era witnessed the religions of Christianity and Islam gaining more prominence over the traditional religions which were considered pagan worship, although people did not completely abandon or withdraw from their African tradition. Post colonialism, between 1973 and 1977, the president of Uganda banned all religious affiliations except Catholic and Orthodox Christian churches (Isiko, Citation2019; Pirouet, Citation1980). In 1986, the National Resistance Movement (NRM) propagated the Pentecostal-charismatic churches and born-again movement that remains a key driving force in shaping religion and spirituality in Uganda. The latest National Population Housing Census in 2014 found the Catholic Church was the largest religious institution (40%), followed by Protestants (32%), and Moslems (14%) (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016). Smaller religious affiliations were Traditional (0.1%), Orthodox Christian (0.1%), Baptist (0.3%), Seventh-day Adventist (1.7%), and non-religious (0.2%). Other grouped dominations (1.4%) included the Salvation Army, Baha’i, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Presbyterians, Hindus, Mammon, Jews, and Buddhists (UBOS, Citation2016). These statistics showed the diversity of religious beliefs in Uganda.

While some dismiss African Traditional religion as pagan worship, there are also scenarios of harmony between African spirituality and western Christianity. These are evident for example in the continued naming of both traditional and English/religious names where the first name is associated with Christian or Islam religions and the last name is traditional-related to a god, cultural practice or prophecy, or phenomenon. On the contrary, some people still strongly oppose western religious identities by having two or more indigenous names. Yet still, their indigenous names can have spiritual meanings attached to them. Nevertheless, African spirituality exerts a strong influence in contemporary Ugandan society attesting to its enduring importance, despite Western colonisation (Masango, Citation2006; Mokhoathi, Citation2017). African spirituality challenges monotheism. Traditional healers perform divination, rituals, cleansing, and exorcising demons (Gumisiriza et al., Citation2021). People associate illnesses and social issues with spirits, ancestors, gods, inheritance, and witchcraft. Hence holistic treatments combine Western medicine with traditional remedies (Mokgobi, Citation2014). Uganda’s National Culture Policy recognises the 10,000 registered traditional health practitioners (Ministry of Gender, Labour & Social Development [MGLSD], Citation2019). In social work practice, very limited research so far shows that in mental health social work, spiritual healing and professional care were simultaneously provided and spiritual interventions, such as prayer and traditional healing, enhanced patients’ hope for recovery (Twesigye, Citation2014). This paper seeks to add to the scanty literature on the centrality of religion and spirituality in social work in Uganda by presenting findings from the authors’ PhD studies.

Method: content analysis

The authors conducted their independent studies for their PhD projects at separate institutions in Australia. They then conducted a content analysis of the PhD research work and found that religion and spirituality were reported as a common theme in the three studies. The authors searched for text referring to spirituality, spiritual, religion, faith, rituals, holy, sacred, heaven, spiritual cleansing in their PhD theses and participants’ transcripts. The text that included these concepts was extracted for analysis to explore how they are used by participants in each study and their implications for social work practice and education. The quotations included in this paper are the voices of various service users and practitioners as identified from the analysis. Pseudonyms are used to maintain anonymity. In the following section, the authors discuss their respective PhD studies, reporting on findings relating to religion and spirituality that inform the common themes explored to conceptualise an African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory (ASSP) and the reflective tool.

Author 1 findings: Sharlotte Tusasiirwe

“We are our own social workers”: older women and the role of self-organised collective caring groups

Among other groups of participants, my PhD research (Tusasiirwe, Citation2019) involved conversations with older women (n = 10) in South-Western Uganda. I asked older women about their good and bad experiences ageing in a rural area and what coping mechanisms they were using to address the challenges they experienced. Older women also answered questions about the community initiatives they were part of that collectively supported older people in their community. One unexpected finding was about older women speaking of spirituality and religion as central to the communal helping they were engaged in serving their rural communities. The older women self-organised collective caring groups through which they pooled resources and supported one another and the community. These caring groups were church-based and were instrumental in meeting the spiritual, emotional, material, and practical needs of people in their communities, particularly orphans, couples seeking advice, and those experiencing domestic violence. Given the limited presence of professional social workers in these rural communities, these groups offered a vital ‘social work’ service. The older women were well known, respected, and within reach of the community. They provided their service with love, care, and respect in keeping with their Obuntu values and the teachings of their Christian religions. Julie and Isabel’s stories show how the older women drew on their religious faith and spirituality to help themselves and others in the community. Julie was a 50-year-old woman, a born-again Christian, and chairperson of a church group supporting orphans and older women in the community. Working as a collective, this group of older women mobilised money and provided material and spiritual support:

We save UGX500 and then we look at these older women of like 60 years, we invite them and when we count and find out that we have some reasonable amount of money in our bag, like UGX100,000, then we buy for each older woman soap, salt; an orphan who does not have anyone looking after them if they are at school, we try and send them something. Then after we have saved, we also inform the church of how much we have saved (Julie, 50)

The church group also sometimes appealed to the general congregation on Sundays to supplement their savings:

There are times when we say in church that this offertory, we have collected is going towards supporting orphans, widows, so a person whom God has touched to give support to the orphans and widows, can give … (Julie, 50).

Support also included prayer and encouragement. The women provided emotional support, hope, and to community members and sustained them to get through hardship.

Isabel (55 years, Catholic) provided support through the Abanyihe (soldiers of Christ) group. She had joined the Abanyangabo group as a young girl and transitioned to Abanyihe group when she got married. The group helped their community by mobilising and providing holistic care and support for their members, mentoring, advising, counselling young couples, and mediating in marital and community conflicts. The group members visited people to nourish their physical, spiritual, emotional, and practical needs:

This group of Abanyihe really helps us. When you are a member of Abanyihe and you fall sick, they come and visit you, pray for you. They look after you very well and if you have some work that is still undone like digging, they help you out. They relieve you a lot. Even you when another person falls sick, you are supposed to reciprocate (Isabel, 55).

The group adheres to the Obuntu value of reciprocity and mutual obligation. Being human (omuntu) obligates members to help others because, at a certain point, they too might need help. Obuntu involves taking care of the most vulnerable:

We also help those who are elderly. We help those who are like me whose husband passed on and have orphans. When you get sick, they will get you money from their group savings and take you to the hospital, buy medications for you. When you don’t have home supplies like salt, the group uses the group savings to buy you the basics (Isabel, 55).

In the absence of government services or NGO support, these long-standing informal groups performed a vital role:

This is a very old group that I found already operating when I was born and it is really helpful because recently my roof was faulty and the group members came together and helped me to fix it. I would not have managed because I lost my husband and I am in this house alone with a little boy (Isabel, 55).

The group demonstrates collective caring for young couples through mentoring, advice, and conflict mediation. Abanyihe members listen and support young couples so that they do not have to experience the issues in isolation. The older women found increasing marital conflict and domestic violence overwhelming given the number of couples seeking their help. They try at all times to respect confidentiality and provide help founded in love:

In this group, the most important thing that is in this group is our love for each other and helping each other out but also keeping the couples’ issues and secrets confidential. For instance, if couples tell you about their family struggles and secrets, you have to keep them at your heart. It has to stay between the two or three of you (Isabel, 55).

The group epitomised the emphasis on community and the role of elders in African spirituality (Knoetze, Citation2019; Masango, Citation2006). The older people are well-known elders in the community and are a valued resource providing spiritual, emotional, material, and practical support. In return, the women find resilience and meaning from being helpful to people struggling in their communities.

Author 2 findings: Diana Nabbumba

Spiritual influences on formal rural aged-care provision

Nabbumba (Citation2021) interviewed 21 stakeholders and 40 caregivers for her PhD research exploring aged care responsibility and provision for older people in rural Uganda. I asked caregivers to tell me about what circumstances or driving factors led them to take on a caring responsibility for older people. In interviews with stakeholders, I asked them to tell me about the social care services they provided to older people in Uganda. Beyond the aims of the PhD study, what stood out was the manifestation and connection of spirituality and religion in why and how stakeholders and caregivers take on responsibilities in social care service provision. Religious leaders and service providers from faith-based organisations played key roles in improving the welfare of older people through a major focus on spiritual care, among others. Stakeholders and caregivers attested to the role of spirituality in shaping the care given and received by older people and in improving their wellbeing. Pastoral care and counselling were key services that included spiritual support through prayer for older people and their caregivers, and spiritual advice and counselling. One pastor said, ‘I advise those who are taking care of them to do so in a good manner. I pray for them’. Religious stakeholders accommodated spiritual diversity when meeting older people’s spiritual needs. A Sister/nun in charge of a care home noted:

As for spiritual nourishment, we care for them as well. We do not convert anyone from their religions. The Catholics go to church and pray. For other religions, if people of the same faith come, they fellowship with them. Socially, they visit each other. We have different wards, two for women and two for men. They could pray together or watch TV together or just sit outside and make conversations.

Some faith-based service providers and organisations expected the beneficiaries to participate in spiritual activities, like fellowships and fasting, and complete bible study sessions before receiving community care. A manager of a Christian organisation noted:

We organize … support meetings or fellowships where they come together, they read a bible because we are a Christian organization, and we look at improving their spiritual life regardless of their faith and they regain hope so in these workshops … If we need 3000 vulnerable people in a village, we approach the local and religious leaders of all denominations. This is because the Catholic or Anglican leaders know their people who will benefit from our services and they … become our ambassadors in the communities.

FBO service providers worked with local church leaders to identify beneficiaries. Their collegial partnership highlighted religious leaders’ key role in shaping care services and spiritual interventions at a macro level.

Spiritual influences on informal rural aged care provision

At a micro level, caregivers paid more attention to caring and improving older people’s wellbeing based on expected blessings as spiritual rewards for caregiving. As one participant’s 20-year-old grandson said, ‘we are caring for them because we want their advice and blessings that can help us in the future’ (Apio, 20). A 30-year-old male caregiver, motivated by community sanction, said:

[I] have received love and favour from within the community. Everyone in the community praises me for what I am doing, and I feel good about it because I have received blessings already due to those positive tongues talked about me (Ofono, 30).

Others noted the reciprocal spiritual guidance they received from older people, as a female caregiver of multiple recipients asserted:

I am thankful that I can experience fellowship with them and talk about God. And they also offer me spiritual guidance; they know historical trends and tell me through stories. When they are have conversations, they speak only good about me, making me happy knowing that they are thankful (Auma, 43).

Conflicting religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs

While spiritual expectations fostered improved support and shaped family care dynamics, conflicting religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs caused tension. Christian beliefs sometimes contradicted Baganda cultural practices embedded in African Traditional Religion. Caregivers battled with adhering to longstanding norms, taboos, and cultural expectations regarding who should engage in a specific task and how it should be undertaken. For example, a 46-year-old female caregiver in central Uganda caring for her father, Nakazzi, said:

You cannot let your parent die because no one can take care of him [due to cultural prohibitions]. I brought him [father] close to my marital home, and my husband built him a small house close by. I do everything for him, bathe and feed him. He is my father; he also took care of me. Even if there is buko [palsy], I cannot let him die just because the culture prohibits that. But, for me, as a born-again, no cultural rituals should be performed on him or me when he dies, the blood of Jesus washes me. At first, he used to refuse, but I encouraged him that I was his only hope and caregiver … now he got used to it (Nakazzi, 46).

Traditional norms position caring roles according to gender, age, and relational status, with Obuntu the yardstick of how well caregivers fulfilled role expectations. Research participants perceived that not adhering to cultural norms like caring for your older parents resulted in negative consequences that they tried to avoid. But Nakazzi also revealed a concern that seeing her father’s nakedness could result in palsy, a medical condition involving paralysis and involuntary tremors and, consequently, they would need to perform certain rituals during the burial. Thus, despite fears of developing palsy, the absence of other relatives propelled her to take care of her father’s personal hygiene needs. While other participants saw this decision as conflicting with traditional norms, this caregiver perceived that her Christian beliefs provided clear guidelines. Although cultural and Christian beliefs promoted care, areas of divergence were evident in caring rituals and healing practices. While Ugandans’ cultural identities existed alongside their religious ones, Nakazzi struggled with finding a compromise between her cultural and religious identities, the identity of being a daughter from a tribe in Buganda requiring her to follow her ancestors’ doctrines and the Christian identity of being born again in a global fellowship of Christian believers. A Ugandan Christian care community acknowledged this struggle as Christians identified themselves as ‘being in the world but not of the world’ (Wardell, Citation2018, p. 179). Therefore, refusing to follow the cultural traditions constituted a rejection of conformity to the standards of this world.

Author 3 findings: Peninah Kansiime

Religion and spirituality for traumatised male survivors of CRSV

My PhD research (Kansiime, Citation2021) involved interviews with 22 purposively sampled social workers in Central, Western, and Northern Uganda working with male survivors of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). The main aim of the study was to explore the experiences of social work practitioners in Uganda working with male survivors of CRSV and their intervention methods. I asked the social workers to tell me about the intervention methods they used and some of the best practices behind effective social work intervention with male survivors of CRSV. From the thematic analysis done, all the social workers talked of the best practice theme of spiritual and cultural sensitivity guiding their practice. They all emphasised the role of religion and spirituality in their work. First, the social workers talked about the diverse spiritual needs of clients seeking their help and the need to identify and address them rather than ignore or silence them. Male survivors and their families regularly consulted religious and spiritual leaders in the community to provide prayer, counselling, and cleansing. Social workers, too, worked with religious and spiritual leaders to hold community memorial prayers for those massacred. A female social worker, Jackie, recalled the ethical and moral dilemmas male survivors experienced, especially since the Bible described male-on-male sexual relations as an abomination. She shared an experience of her client, a Pastor, who preached against sodomy. Following his experience of sexual violence, his Christian faith helped him cope:

He was so guilty and suicidal at the same time. You know a believer, so I kept using the part of faith telling him you know bad things happen to good people but there is always a way out and we shall manage together. And for me, of course, what I came to realise is there are so many aspects of this person that get affected … And I think when you are a social worker, you get to a place where experience teaches you. Like I came to learn religion has a very big role it plays with peoples’ suffering. You know when you are, at times, in these organisations, they don’t even want you to mention that part of religion … but you would still see again there is another component you need to deal with (Jackie, 42)

Jackie’s practice wisdom helped her interpret and make meaning out of male survivors’ suffering. She saw how conflicting beliefs led to mental distress and poor mental health. Confronting these issues involved exploring and responding to their spiritual needs and providing spiritual counselling. Some participants who worked in faith-based organisations had referred their clients to religious leaders within their professional networks. Koire, a 39-year-old male social worker, who worked for a Catholic organisation that welcomed all faiths and creeds, said clients were free to use their chapel, where a Catholic priest offered spiritual counseling:

Sometimes there is a mass for those who feel they are of Catholic representation and they would like to pray, they have the opportunity but there also those of other faith they are free to do so if they want to pray and so on they have the space always (Koire, 49)

However, addressing religious beliefs and spiritual needs in dealing with CRSV went beyond prayer and spiritual counselling to influencing public opinion on sexual violence against men to reduce stigma and encourage survivors to seek professional help. Ken, a 38-year-old male social worker in Northern Uganda, where communities endured over 20 years of civil war under the Lord’s Resistance Army led by the infamous Joseph Kony, said that his organisation worked closely with non-elected religious and spiritual leaders:

These are … opinion leaders; people who are respected in the community because of their age and any other thing … [They] are people who have been helpful in working with survivors of sexual violence, especially male survivors. We have achieved a lot because of them, most especially in Northern Uganda … This is not something connected to any education somewhere but because they are … respected within the community and people think they are the right people (Ken, 38).

In former massacre sites in Northern Uganda, communities held annual memorial prayers and ceremonies for the souls of victims and traumatised survivors living with the consequences of these atrocities. Social workers noted that, besides religious solace, survivors sought spiritual solutions from their cultures; healing required cultural cleansing. A 33-year-old female social worker recalled a client, who had returned from abduction, and was not responding to counselling and medication. On exploring this further, the client enlightened her that ‘I am not going to get healed … because I am not cleansed’ (Anna, 33). One social worker talked about ritual cleansing at massacre sites because the residents in the community believed the areas were haunted:

It was a massacre; people were put in pits, people were raped, rights were violated in that area. Can we be able to link up with traditional institutions, like the Acholi cultural institution, so that, if they say that we need to do some cleansing ceremony, can they be able to do that ceremony? We know the church has gone and made prayers in those areas … But it is not enough, due to the belief of the people in the society. The religious bit is doing their side and the people are saying, when they walk here at night, they get lost because they believe there is some bad spirit, these are symbolic issues. Yeah, it is not bringing a witchdoctor; it is just bringing their traditional leaders do the cleansing the same way they do the Mato Oput [traditional justice] process. Those models they do in Acholi culture that people can believe in and it works for them (Akena, 42).

These stories have demonstrated the complementary role that religion and spirituality played in responding holistically to client needs. Respecting client self-determination, and pursuing healing and recovery, social workers worked with religious and traditional leaders and healers and their spiritual practices like cleansing, memorials, and prayer to provide help to individual survivors.

Common themes: an African spiritually-sensitive practice-theory for social work practice and education

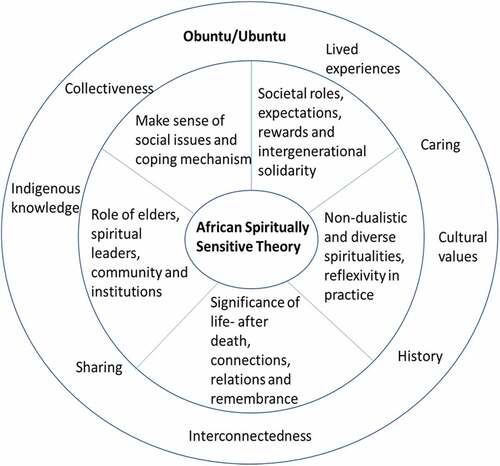

From the findings of these three independent studies, the authors have devised five core themes that comprise what they are terming an African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory, illustrated in a model to aid practice and education. The core themes and concepts of the theory are the extracted common findings around religion and spirituality from the three independent studies. The theory contributes to filling the gap in conceptualising social work theories and models constructed based on local, indigenous experiences and voices (Mabvurira & Nyanguru, Citation2013; Twikirize, Citation2014). This theory and core themes illustrated in can be used in practice contexts in Uganda to understand clients’ behaviour and social concerns around religion and spirituality. In education, the theory can be used in teaching students about religion and spirituality in social work from an African perspective. illustrates these core themes which include recognising:

Life-after-death connections, relations, and remembrance

Societal role distribution, expectations, rewards, and intergenerational solidarity

Role of elders, spiritual and religious leaders, community and institutions

Spirituality as a mechanism for making sense of and coping with social issues

Non-dualistic diverse spiritualities and reflexivity in practice.

The overarching African philosophy of Obuntu or Ubuntu encapsulated these core themes elaborated below and linked to social work education and practice.

Life-After-Death connections, relations, and remembrance

Life-after-death connections, ancestral influence, and remembrance featured prominently in the narratives and literature on African spirituality (Mabvurira, Citation2020; Mutambara & Sodi, Citation2018). Life does not end at death and those who have died continue to influence the living, their families and communities, as seen for example through practices like memorial prayers and ceremonies on death anniversaries organised by surviving families and religious and traditional healers working with social workers in Uganda. African spiritually sensitive social work interventions included support for those living and those who have departed, through memorial prayers, rituals, and ceremonies for surviving families and communities. Social work practitioners recognised the influence and significance of memorial activities and ancestor honour to support families to maintain their connectedness with their departed. Organising honour activities or memorial prayers can be an intervention to helping, individuals, families, and communities cope with trauma, grief, bereavement, loss, and distress (Mutambara & Sodi, Citation2018; Park, Citation2017). This core theme of African social work focused on both the living and dead is related to what Park (Citation2017) terms memorial social work. It is an indigenised alternative social work to the current secular model that predominantly focuses social work as “a ‘worldly’ activity that focuses mainly on ‘living’ service-users, while paying less attention to the people who have died and their ongoing influence on descendants” (Park, Citation2017, p. 368).

Traditional role distribution, expectations, rewards, intergenerational solidarity

From the narratives and existing literature (Knoetze, Citation2019; Masango, Citation2006), we note that African tradition allocates roles based on age, gender, seniority, and negative and positive rewards associated with fulfilling the roles and sociocultural expectations. The young, for example, care for the old as the African proverb goes that when a rabbit grows old, it sucks the breasts of its children. The older generation, in turn, nurture, advise, mentor, and pass on their cultural values and knowledge to the younger generation. As custodians of indigenous knowledge, older people share stories and lessons from lived experiences in a relational way. This African spirituality demonstrated the intergenerational interdependence and solidarity between the young and old, shown in the narratives of older women and caregivers shared earlier. Obuntu values of care and respect for older people frame and shape reciprocal human relationships. Older people are to be revered and respected and failure to care for older people can ruin an individual’s reputation. Reputation and its corollary shaming are crucial because people live as communal beings, nurtured and shaped through their relational connections. People who have done good in the community are revered and remembered, as ancestors when they die (Masango, Citation2006). Even after death, younger generations emulate the actions of ancestors, including caring for older people. People also believe that bad luck or curses would accrue if they neglected to care for their older parents or showed disrespect to older people in general. Through Obuntu caring values, people find meaning in caring for older people in their communities and homes, respecting their dignity and worth in society. However, with increasing Westernisation, where values of individualism and breaking away from extended family are increasingly being embraced by some African people, coupled with increasing poverty, older people are experiencing neglect, abuse and ageism, among others (Tusasiirwe, Citation2019). Thus, African spiritually sensitive social work recognises the importance of caring and respecting older people and social workers’ roles remain to encourage and restore such threatened Obuntu values that respect older people and promote intergenerational solidarity.

Role of elders, spiritual and religious leaders and institutions

The role of elders, and spiritual and religious leaders have been amplified in the narratives by older women, caregivers and social workers. Also, the role that churches and other faith-based organisations and NGOs play in meeting the spiritual, emotional, material, and practical needs of clients and communities have been highlighted. Thus, superfluous ASSP? when did this relate from a theory to a practice model? practice recognises elders and community leaders as a resource with accumulated wisdom, knowledge, and respect in the community. Elders are the people who have reached a great age and maturity in life and have accumulated rich experiences that they can share to guide and advise others in the community, including the younger generation (Masango, Citation2006). People consult elders about managing different stages of life, including child upbringing, marriage for younger couples, domestic violence, or other conflicts in the community, as demonstrated by the participants. In practice, practitioners can partner with spiritual and religious leaders to address issues affecting individuals and communities. These leaders model social work and care provision based on love and respect and long-standing genuine relationships, central ethical principles to social work practice.

Spirituality is a mechanism for making sense of, and coping with, difficulties

In African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory, spirituality provides a lens for understanding how people find meaning in, and cope with, adverse social circumstances, such as trauma arising from rape, war, gender discrimination, and natural disasters (Currier & Eriksson, Citation2017; Mutambara & Sodi, Citation2018). The findings show that spiritual solutions are as important as medical, psychological, and other forms of support, especially for people coping with trauma, loss, and distress. African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory recognizes and speaks clients’ spiritual language and does not dismiss spiritual explanations of client problems (Mabvurira, Citation2020). It is evident that people’s spiritual beliefs provide hope, optimism, resilience, perseverance, and strengths, while religious practices like prayer and communal worship provide a sense that ‘we are not alone and together we can find our way through our personal and communal problems’.

Non-Dualistic diverse spiritualities and reflective practice

Findings reveal that a non-dualistic, diverse spirituality and reflexivity in practice are essential and have implications for social work students and practitioners. African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory acknowledges that non-dualistic diverse spiritualities including indigenous and religious belief systems, strongly influence people’s lives. In Africa, religion (Western and African) coexists (complementing or in tension) with traditional sociocultural beliefs and practices, as the narratives of social workers, male survivors, and older people in this paper attested. Social workers need to understand and respond to their clients’ spiritual needs and strengths. Spiritual assessment protocols developed by social work scholars like Canda and Furman (Citation2010) and Fook and Gardner (Citation2007) indicated the need for critically reflective practice yet did not offer further guidance on how this works in African contexts. Therefore, we offer a reflective tool to guide social workers in understanding their clients’ spirituality and support them respectfully, in a non-judgmental manner, while also not losing sight of their own spiritual identity. The notion of reflexivity in spiritually sensitive practice calls for social workers’ intentional, cautious, self-directed analysis of spiritual and religious beliefs and their impact on practice (Gardner, Citation2016). Practices like meditation, journaling, mindfulness, music, dance, and art, are among the practices that improve self-awareness. Reflexivity in African Spiritually Sensitive Practice-Theory calls for reflection on how social workers might improve their communication on issues related to spirituality, engagement, and empowering clients to reach their spiritual potential to address problems in coping. Reflexivity is a step beyond self-awareness to practice improvement through spiritually sensitive interventions. Completing the reflective tool () can assist social workers in making appropriate adjustments and responses to spirituality-related issues raised by clients.

The tool () lays the ground for critical reflection to enhance awareness of personal beliefs and assumptions and their influence on practice, especially in relation to client spirituality. Reflection helps social workers in situating their spiritual beliefs within a broader organisational context and draw on support structures, policies, and colleagues to acquire feedback, advice, and mentoring. Social workers could use the tool alongside spiritual assessment, spiritual life maps, and genograms (Mokgobi, Citation2014).

Implications for social work education

Given the centrality of religion and spirituality in the participants’ narratives, supported by literature (Mabvurira, Citation2020; Masango, Citation2006; Mutambara & Sodi, Citation2018; Twesigye, Citation2014), we propose that social work students need to take general foundational courses on religion and spirituality that include local constructs and practices of spirituality and religion in relation to social work. Foundational topics of spirituality can be introduced in first-year courses, as well as later in courses on human behaviour and social environment. A short 3-6 months course can be introduced for educators and professional development courses offered to enhance spiritually sensitive social work to practitioners and the National Association of Social Workers in Uganda can take leadership in ensuring this professional development. We have conceptualised an African Spirituality Sensitive Practice-Theory and a reflective tool that can be a starting point for social work educators and practitioners to use, expand, and critique.

Given the importance of reflective practice, for social workers to implement this practice, knowledge must be imparted to social work students. Hence it is important to incorporate the reflective tool into the social work curriculum. Discussing and answering questions in the reflective tool can help social work educators teach students how to engage clients in discussions of their spiritual wellbeing or the role of spirituality in their lives. Educators could also use the tool to facilitate student awareness of religion and spirituality as a core part of human social functioning and personal identity and teach them how to use spiritual assessments in practice. Educators could teach these practical considerations using local case studies and role-plays in the classroom or in the field. This reflective tool can be incorporated and adopted by students during fieldwork placements to enhance spiritual sensitivity assessment.

Students can be assessed on the reflective tool and their engagement with religious and traditional elders when interviewing about issues on spirituality that can yield to better communication of spiritual issues and spiritual wellbeing for clients. This paper has shown that spirituality drives service provision and that community, traditional and religious leaders play social work roles. Therefore, social workers must look out for them in the community and work alongside them in their education and practice by capitalising on the indigenous knowledges towards problem-solving to address issues affecting individuals and communities. In social work education, religious and traditional leaders can be invited as guest speakers to advance discussions on spirituality within the classroom. Field study tours can also be carried out to introduce students to the communities within which spirituality impacts social work, hence getting first-hand information and experiences to enrich their indigenous knowledge towards application in social work education. The elders can serve on ethical committees for social work research and on committees that design and review the curriculum to ensure that indigenous African knowledge is centred.

Conclusion

In Uganda, Western and African religion coexists as complementary or in tension with traditional sociocultural beliefs and practices, as the narratives of social workers, male survivors, and older people in this paper attested. The paper demonstrated how vulnerable groups in Uganda drew on religion and spirituality. Although this paper is limited by the analysis of PhD research that adopted small sample sizes and cannot be generalised, it offers vital contributions to the global theme of spirituality and religion in social work education and practice in Africa. It suggested an ASSP model and reflective tool to guide social workers in meeting clients’ spiritual needs. It proposed that the inclusion of spirituality in social work education would make educators and students more comfortable and familiar with diverse spiritualities beyond their own. As Carroll (Citation1998) observed, ‘to address the spirituality of our clients is not to practice religion but is to affirm the wholeness of their being’ (p. 11).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge the research funding from their universities: Western Sydney University, La Trobe University and University of Newcastle. The authors also acknowledge Prof. Mel Gray for her in put in structuring and thorough editing of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Bhagwan, R. (2010). Spirituality in social work: A survey of students at South African universities. Social Work Education, 29(2), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470902912235

- Canda, E. R., & Furman, L. D. (2010). Spiritual diversity in social work practice: The heart of helping. Oxford University Press.

- Canda, E. R., Furman, L. D., & Canda, H. J. (2019). Spiritual diversity in social work practice: The heart of helping. Oxford University Press.

- Carroll, M. M. (1998). Social work’s conceptualization of spirituality. Social Thought, 18(2), 1–13. doi:10.1080/15426432.1998.9960223.

- Chepkwony, A. K. A. (2007). African traditional medicine: Healing and spirituality. Science, Religion, and Society, 2, 642–648.

- Currier, J. M., & Eriksson, C. B. (2017). Trauma and spirituality: Empirical advances in an understudied area of community experience. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 45(4), 231–237. doi:10.1080/10852352.2016.1197755.

- Doyle, S. (2007). The Cwezi-kubandwa debate: Gender, hegemony and pre-colonial religion in Bunyoro, western Uganda. Africa, 77(4), 559–581. doi:10.3366/afr.2007.77.4.559.

- Ebimgbo, S., Agwu, P., & Okoye, U. (2017). Spirituality and religion in social work. In U. Okoye, N. Chukwu, & P. Agwu (Eds.), Social work in Nigeria (pp. 93–103). University of Nigeria Press Ltd.

- Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2007). Practising critical reflection: A resource handbook: A handbook. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Furman, L. D., Benson, P. W., Grimwood, C., & Canda, E. (2004). Religion and spirituality in social work education and direct practice at the millennium: A survey of UK social workers. British Journal of Social Work, 34(6), 767–792. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23720509

- Gardner, F. (2016). Critical spirituality in holistic practice. Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 6(2), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/20440243.2016.1235185

- Gray, M. (2008). Viewing spirituality in social work through the lens of contemporary social theory. British Journal of Social Work, 38(1), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl078

- Gumisiriza, H., Sesaazi, C. D., Olet, E. A., Kembabazi, O., & Birungi, G. (2021). Medicinal plants used to treat“African” diseases by the local communities of Bwambara sub-county in Rukungiri district, western Uganda. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 268(113578), 113578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.113578

- Isiko, A. P. (2019). State regulation of religion in Uganda: Fears and dilemmas of born-again churches. Journal of African Studies and Development, 11(6), 99–117. doi:10.5897/JASD2019.0551.

- Kansiime, P. (2021). Social work with male survivors of conflict-related sexual violence: the experiences of practitioners and intervention methods [Doctoral thesis]. University of Newcastle.

- Knoetze, J. J. (2019). African spiritual phenomena and the probable influence on African families. Die Skriflig/in Luce Verbi, 53(4), 1–8. doi:10.4102/ids.v53i4.2505.

- Levin, J. (2021). Western esoteric healing I: Conceptual background and therapeutic knowledge. Explore, 17(2), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2019.10.008

- Mabvurira, V., & Nyanguru, A. (2013). Spiritually sensitive social work: A missing link in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Social Work, 3(1), 65–81. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajsw/article/view/127541

- Mabvurira, V. (2020). Making sense of African thought in social work practice in Zimbabwe: towards professional decolonisation. International Social Work, 63(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872818797997

- Mande, W. M. (1996). An ethics for leadership power and the Anglican church in Buganda. University of Aberdeen (United Kingdom).

- Masango, M. (2006). African spirituality that shapes the concept of Ubuntu. Verbum Et Ecclesia, 27(3), 930–943. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v27i3.195

- Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development. (2019). Uganda National Culture Policy. Kampala, Uganda. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/qpr/uganda_national_culture_policy_reviewed_2019_0.pdf

- Mokgobi, M. G. (2014). Understanding traditional African healing. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 20(2), 24–34.

- Mokhoathi, J. (2017). Imperialism and its effects on the African traditional religion: Towards the liberty of African spirituality. Pharos Journal of Theology, 98(1), 1–15. http//:www.pharosjot.com

- Mugumbate, J., & Chereni, A. (2019). Now, the theory of Ubuntu has its space in social work. African Journal of Social Work, 10(1). https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajsw/article/view/195112

- Mutambara, J., & Sodi, T. (2018). Exploring the role of spirituality in coping with war trauma among war veterans in Zimbabwe. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017750433

- Nabbumba, E. D. (2021). Examining responsibility allocation within the social care system in rural Uganda: An ecological systems approach [Doctoral thesis]. La Trobe University.

- Okoth, P. G. (1992). Africa’s development nightmare: Uganda’s case. Journal of Eastern African Research & Development, 132–149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24326232

- Owor, J. (2004). Faith and learning: The impact of Uganda Christian university programmes on the spiritual development of its students. The 20th Annual Conference of the Christian Business Faculty Association, Gunter Hotel, San Antonio, Texas.

- Park, H.-J. (2017). Lessons from filial piety: Do we need ‘memorial social work’ for the dead and their families? Qualitative Social Work, 16(3), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325015616289

- Pirouet, M. L. (1980). Religion in Uganda under Amin. Journal of Religion in Africa, 11(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-01101003

- Rubongoya, J. (2007). Regime hegemony in Museveni’s Uganda pax Musevenica (1st ed. 2007. ed.). Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Tusasiirwe, S. (2019). Stories from the margins to the centre: Decolonising social work based on experiences of older women and social workers in Uganda [Doctoral thesis]. Western Sydney University.

- Tusasiirwe, S. (2020). Decolonising social work through learning from experiences of older women and social policy makers in Uganda. In S. Tascon & J. Ife (Eds.), Disrupting whiteness in social work (pp. 74–90). Routledge.

- Tusasiirwe, S. (2021). Social workers navigating a colonial bureaucratic system while also re-kindling obuntu-led relational social work in Uganda. In J. Boulet & L. Hawkins (Eds.), Practical and political approaches to recontextualising social work (pp. 175–191). IGI Global.

- Twesigye, J. (2014). Explanatory models for the care of outpatients with mood disorders in Uganda : An exploratory study. StellenBosch University.

- Twikirize, M. J. (2014). Indigenisation of social work in Africa: Debates, prospects and challenges. In H. Spitzer, M. J. Twikirize, & G. G. Wairire (Eds.), Professional social work in East Africa: Towards social development, poverty reduction and gender equality (pp. 75–90). Fountain publishers.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2016). The national population and housing census 2014 – main report.

- Van Niekerk, B. (2018). Religion and spirituality: What are the fundamental differences? HTS: Theological Studies, 74(3), 1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i3.4933

- Wardell, S. (2018). A stranger in the name of Jesus’: Exploring cosmopolitan ethics in a Ugandan Christian care community. Sites: A Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.11157/sites-id404

- White, S. L. (1999). Colonial-Era missionaries’ understanding of the African idea of god as seen in their memoirs. Anglican and Episcopal History, 68(3), 397–414. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42612039