ABSTRACT

This paper brings together two areas of importance to social work education, professional identity and professional writing; identity is often viewed as central to social work practice and education, whilst writing as marginal. However, given that social work is a ‘writing intensive’ profession, writing is a key site of the enactment of professional identity and practice, meriting significant attention. Using the notion of ‘voice’ this paper explores professional identity in writing by analyzing two datasets: 1) a corpus of 1 million words of professional social work writing, exploring the use of I and my perspectival phrases; 2) interviews with 71 social workers exploring perspectives on professional voice in written discourse. Textual analysis indicates six key functions of the social worker I, with an emphasis on the professional voice as reporter, rather than evaluator or analyst. Thematic interview analysis offers insights into the complexity of voice, indicating the contested positioning of the social worker I. We call for critical attention to be paid to voicing in written discourse in social work education and ongoing professional development, indicating ways in which findings and data from this article could be used as resources for pedagogy and debate.

Introduction

This paper aims to bring together two areas of concern in social work studies and education: professional identity and professional writing. The former, professional identity, is an established ‘matter of concern’ (Latour, Citation2004), the latter, professional writing, is a more recent concern (Healy & Drayton, Citation2022), and tends to be treated as marginal to, rather than fundamentally connected with, issues of professional identity. Definitions of ‘professional identity’ in general (e.g. Paquette, Citation2016) and social work professional identity in particular have long since been debated (e.g. Healy & Link, Citation2011), with varying emphases in the latter according to the specific focus and theoretical approach adopted: the characteristics and values of the social work profession (e.g. Banks, Citation2020), the formation of professional identity (e.g. Hamilton, Citation2019; Moorhead et al., Citation2019), the shifting and complex nature of social worker identity (e.g. Almeida et al., Citation2019; Dominelli, Citation2017), the politics of professional subject positioning (Forenza & Eckert, Citation2018; Gordon & Dunworth, Citation2017). Whilst there are ongoing debates around the definitions and theorizations of‘professional social work identity (for useful overview see Webb, Citation2017), core to all studies is the notion that professional identity is “how a social worker thinks of her or himself [sic] as a social worker” (Webb, Citation2016, p. 355). This sense of self involves an interdependence between the individual—life histories with different experiences and markers of identity such as ethnicity, class, gender, as well as specific concerns and interests—and social context, the historically situated legal, organisational, political and cultural norms governing social work practice (for useful discussion, see Fearnley, Citation2022). Understanding the many ways in which a social worker’s evolving (Wiles, Citation2013) sense of self as a social worker is implicated in social work practice is important in social workers’ education and ongoing development. This paper is specifically concerned with social workers’ sense of self with regard to a key aspect of their professional practice, writing.

Professional social work writing is a far less prominent albeit growing ‘matter of concern’ within social work studies. By professional writing, we mean the writing that social workers carry out as part of their everyday professional responsibilities involving a wide range of distinct functions—administration, applications for services, assessments, communication with others, contracts, diagrams and mapping, documents mediating meetings with service users and other professionals, reports, training and supervision documents. Key genres are case notes, assessment reports of many different types and e-mails (for full description based on empirical tracking see Lillis et al., Citation2017). Whilst guidelines on writing (professional, student, and academic) abound in hard and digital formats (a Google search on ‘social work writing’ generates 3,260,000,000 results, October 2023), prior to the WiSP (Writing in Professional Social Work) study on which this paper is based, only a small number of studies had taken professional social work writing as the primary object of investigation, with even fewer including authentic texts written by social workers as empirical data. These include one case of written records in Children’s Services (Hall et al., Citation2006); a diary, text and interview-based study with five social workers (Lillis and Rai, Citation2012; Rai & Lillis Citation2013); and an ethnographically-framed study on case recording in Adult Services (Lillis, Citation2017). Some studies have focused on social workers’ perspectives on writing (e.g. Roesch-Marsh, Citation2016; Roets et al., Citation2017) and a small number of works have centered on dimensions clearly linked to the production of the written record, such as IT and organizational systems (White et al., Citation2010), and the ways in which information about ‘clients’ is filtered in interaction (Huuskonen & Vakkari, Citation2015).

It is important also to note that the historical invisibility of professional writing, both as a focus of research and of social work education, has been accompanied by a highly visible deficit orientation toward social workers’ writing. In UK media and official reports negative evaluations dominate, for example, ‘poor recording’ (e.g. Department of Education, Citation2011; Health and Care Professions Council [HCPC], Citation2018), ‘poor—records management’ (e.g. Care Quality Commission, Citation2017, p. 35, 41) and ‘poorly written’ (Ofsted, Citation2019). Criticisms of social work writing (often under the label of ‘recording’ and more broadly ‘communication’) are frequently central to public inquiries which hit headline news when a case of extreme abuse or death occurs (Balkow and Lillis, Citation2019). A deficit orientation toward the ‘language’ of social workers is also strongly evident, often criticized, as ‘jargon’ (Community Care, Citation2018a; Ofsted, Citation2019), or for being ‘euphemistic’ or ‘sanitised’ (SCIE, Citation2016) and for illegitimate uses of specialist or ‘expert’ discourse (Community Care, Citation2018b).

The aim of this paper is to take social work writing out of this invisibilised yet deficit framing and put writing firmly within the purview of the more complex and nuanced debates about what it means to be a professional social worker in contemporary society. The paper begins with a heuristic for exploring ‘voice’ in professional writing which is used as an organizing concept to articulate the relationship between professional identity and professional written discourse. This is followed by an overview of the larger study on which this paper is a part and an outline of the specific study, questions and methodology of the present paper. The main part of the paper centres on the analysis of two datasets: a corpus of social work writing involving an analysis of key markers of voice, the first person singular, I, and my perspectival phrases; and interviews with social workers exploring their perspectives on professional voice in their writing. Key findings from both datasets are brought together in the Discussion, followed by a summary of the ways in which findings and data from this article could be used as resources for pedagogy and debate.

Theoretical framework: a heuristic for exploring social worker voice in written discourse

The notion of ‘voice’ is used in social work studies, and the social sciences more widely, to signal a cluster of specific ideological, epistemological and methodological orientations (Lillis, Citation2013), core to which is the importance of paying attention to people’s everyday accounts and practices in order to understand the meanings they make of their lives (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007; Lillis, Citation2023).

With regard to social work studies, attention to voice is most strongly represented in the focus on ‘service user’ experiences, as a corrective to institutionally dominant practices and towards engaging more holistically with service user concerns and desires (e.g. Cree, Citation2013). Less attention has been paid to social worker voices which are often marginalized compared with other more powerful voices about social work, e.g. the media, inspectors, judges (Amas & Fox, Citation2023). This paper seeks to contribute towards making social workers’ ‘presence and positioning’ (Gordon, Citation2018, p. 1336) a more sustained focus in social work education, focusing specifically on such positioning in professional writing.

Our aim is to foreground in particular the discoursal dimension of voice. Where attention has been paid to voice in social work research, there is a tendency to foreground the what of people’s accounts, which can be described as voice as experience/perspective, as well as who they feel they are enabled/constrained to be, which can be described as voice as agency/positioning. Far less attention has been paid to the written how of voice which we refer to as voice as language/discourse, although specific attention to social worker written language use is signaled in some studies, at a broad rhetorical level, in studies exploring the impact of ICT systems (e.g. White et al., Citation2010), and, less so, at a the linguistic level, of specific use of phrases (e.g. reported speech in Amas & Fox, Citation2023, p. 7).

In exploring social work writing, the approach adopted in the WiSP project and this paper is one which sees writing as a socio-historically situated discursive practice (Blommaert, Citation2005). Within this approach, the core semiotic how of voice, language, is not viewed as abstracted from context but as a complex heteroglossic resource for meaning and identity making, bound up with individual and social histories of use and therefore always challenging to take control over:

Language is not a neutral medium that passes freely and easily into the private property of the speaker’s intentions; it is populated – overpopulated – with the intentions of others. Expropriating it, forcing it to submit to one’s own intentions and accents, is a difficult and complicated process. (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 294)

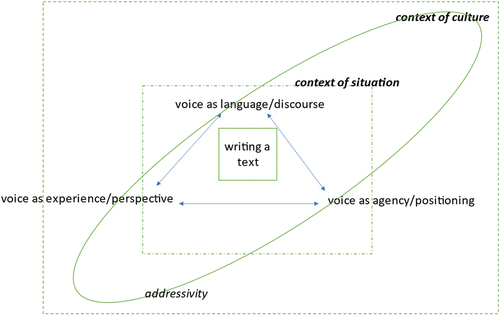

Within this framing the three dimensions of voice cannot be separated (see ): what you (can/not) say/write (voice as experience/perspective) is bound up with who you (can/not) consider yourself to be (voice as agency/positioning) and reflected and enacted in how you (can/not) say/write, the specific language used, (voice as language/discourse). Furthermore, within this framing, voice is not solely the result of individual production of meaning, but is bound up with addressivity, that is, responding to and addressing a real and/or imagined other(s):

Figure 1. A heuristic for exploring voice in professional social work writing (after Lillis, Citation2001).

A constitutive marker of the utterance is its quality of being addressed to someone, its addressivity—the utterance has both an author—and an addressee. Both the composition and, particularly the style, of the utterance depend on those to whom the utterance is addressed, how the — writer senses and imagines his [sic] addressee, and the force of their effect on the utterance. (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 95)

*utterance refers to any use of language, spoken or written and at any level e.g. a word, a phrase, an argument

An example of addressivity at a more immediate context of situation is a social worker envisaging a particular service user or manager reading her report, and at broader context of culture (Fairclough, Citation1992, after Malinowski), implicitly orienting to more abstract entities, such as the ‘local authority’, the ‘courts, the ‘media’.

This paper aims to make visible key aspects of social worker voice in professional writing, viewing each instance of writing—crafting an utterance—as an attempt to take control over a complex resource, powerfully shaped by contexts of situation and culture. Taking greater control over this resource is central to learning to become, and, making choices about, being a social worker.

The larger study: research questions, methodology, data of the WiSP project

The larger ESRC-funded research WiSP project, of which the study reported in this paper is a part, involved five local authorities in England, with participating social workers from Children’s and Adults’ Care.Footnote1 Given the lack of empirical research on professional social work writing, the objective of the project was to explore four fundamental questions: 1. What are the institutional writing demands in contemporary social work? 2. What are the writing practices and perspectives of professional social workers? 3. What are the challenges faced and solutions found? 4. How are writing demands and practices shaping the nature of professional social work? Epistemologically, the WiSP study is ethnographic, seeking to develop a ‘thick description’ (Geertz, Citation1973) of writing and the contexts in which writing is produced, including the meanings attached to such writing by social workers. Methodologically, the study involves mixed methods combining tools from ethnography, qualitative discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to explore the nature and significance of social work writing.Core datasets include interviews with 71 social workers, 10 weeks of researcher observations, 481 days of social worker logs and 4608 written texts constituting a one-million-word corpus. Ethics and governance procedures were followed in compliance with the formal requirements of the university and all agencies involved, as well as additional anonymization agreements made with participating social workers (for discussion of ethics see Lillis et al, Citation2023; full details of the methodological tools and the data generated are available open access at the U.K. Data Service ReShare repository, http://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/853522).

The present study: questions, data, methodology

This paper focuses on voice in professional social work writing involving two research questions:

How is social worker voice represented in professional written discourse, focusing specifically on the first person I and my perspectival phrases?

What are social workers' perspectives on professional voice in writing?

Written texts produced by social workers as part of their everyday work were used as data to explore the first question, and interviews with social workers from Children’s and Adults’ Care to explore the second.

Why focus on the use of the first person?

The textual focus in this study is the use of the first person - I and my perspectival phrases- for several reasons:

The inclusion of the first person is the most explicit expression of a writer’s voice and therefore an important focus for exploring a social worker’s textual self or presence.

Whilst in regulations and guidelines the use of the first person is often proscribed in formal writing of all kinds in favor of impersonal expressions and the use of the third person, research in many different national contexts has underlined the ethical and epistemological interrelationship between voice and the use of the first person. This is particularly evident in the substantial research on academic writing, of students and of academics internationally (eg. Horner & Lu, Citation1999; Ivanič, Citation1998; Lillis & Curry, Citation2010; Thesen & van Pletzen, Citation2006; Tuck, Citation2018; Zavala, Citation2011) but has also surfaced in the limited studies on social work writing, which have included discussions of: the effect of the use of the first as compared with the third person in reporting events and cases (e.g. Taylor 2008); the tensions and challenges experienced by newly qualified social workers in making decisions about the use of the first and third person for different genres (Lillis & Rai, Citation2012; Rai & Lillis, Citation2013); managers’ concerns about the lack of explicit expression of social worker voice in records (Lillis, Citation2017);

Social workers’ desires to use the first person, whilst at the same time feeling restricted from doing so, are often expressed in professional training sessions (see Lillis, Citation2017) and is currently an important topic of debate in a current multiagency project in response to the Independent Care Review in Scotland (https://thepromise.scot/; see WRAM, Citation2023).

Text data and analysis

The text analysis in this paper involves a 1 million-word corpus of 4,608 social worker texts consisting of three main categories: case notes (2,624), e-mails (1,587) and reports (244; this term refers to the many kinds of assessment reports that social workers produce, e.g. Assessment of Needs, Assessment of Parenting, Assessment of Risks, for more details see Lillis et al., Citation2017). Together, these three text categories constitute 94% of the WiSP corpus with the remaining 6% (143) comprising miscellaneous text types such as letters, administration forms and finance requests.

Instances of I were calculated using the methodology of corpus linguistics which enables searching across large collections of digitized data. The LancsBox software tools (Brezina et al., Citation2021) were used to identify instances of I as a personal pronoun. The resulting concordance lines (exemplified in ) were exported to Excel for easier sorting and classifying with follow-up searching employing WordSmith Tools (Scott, Citation2022). In line with corpus linguistics methodology, a random sample of 200 lines from each social work text type were categorized for both writer (who), and function (purpose). Categorisation of the writer (‘who’) was based on identifying the voice of the I, e.g. the social worker, the adult service user, the child. A further search using the same corpus linguistic tools was used to search for ‘my perspectival phrases’. The generation and categorization of the concordance lines involved two researchers in an iterative process of checking across categories in order to reach a consistent set of classifications (for discussion of ethics and corpus buiding, see Leedham et al., Citation2020).

Interview data and analysis

The interviews with 71 social workers in Children’s and Adult Care included one explicit question about professional voice/view in relation to case notes which opened up discussion about professional voice/view in writing in general (for full details of participants including selection and interview schedule see U.K. Data Service ReShare repository, http://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/853522). This specific question and the decision to phrase the interview discussion using the terms professional ‘voice’ and ‘view’ were based on an earlier project (Lillis et al., Citation2012; Lillis, Citation2017) where both terms were used by social workers to discuss the ways in which they positioned themselves in their writing.

Two interrelated forms of analysis of the interview data were carried out: one researcher iteratively read and annotated transcriptions of individual social worker interviews, generating a list of core provisional headline notes about each individual’s perspective; two researchers read across the complete interview dataset and using Atlas.Ti generated 42 codes relating to comments explicitly or implicitly signaling voice. In generating the four overarching thematic categories discussed below, one researcher moved between the two sets of headline notes and codings.Footnote2

Findings from the text analysis: the prevalence, functions and voicing of I/my perspectival phrases

The I voice

The total number of the first person singular I in the 1 million-word WiSP corpus is 10,931, giving a rate of 10.9 occurrences per 1000 words which is similar to the rate of 9.9 found by Baker (Citation2023) in a corpus of current British written English (press, general prose, academic writing and fiction). The figure at first glance suggests a strong presence and visibility of social worker voice in written texts. However, when different text types are considered, the range of usage by social workers is more complex ().

Table 1. I in case notes, e-mails and reports.

Prevalence for the purposes of this paper is calculated as instances per 1000 words, with 5 signaling low prevalence, in reports, and 26 high, in e-mails. The high prevalence of I in e-mails is perhaps unsurprising as these texts are written directly from one individual to another specific addressee(s).

Based on analysis of those instances where the I was in the voice of the social worker, six key function categories were identified, across the text types, outlined in .

Of course, some discourse signals several functions: for example, reflection and emotion may both be being signaled in the phrase, ‘I feel that’. Given that the purpose of the analysis here is to make visible the range of dimensions signaled explicitly in written discourse, we have categorized discourse according to the most literal or referential meaning which in the case of ‘feel’ is categorized as ‘emotion’.

Analysis of sets of 200 randomized examples of the writer (who) and function (purpose) of the I voice across two of the three main text types, case notes and e-mails, is summarized in .

Table 2. The who and function of I in case notes and e-mails.

* We have not included examples of service user I voicing in this Table.

In both e-mails and case notes, the overwhelming I voice is that of the social worker.There were only three instances (in case notes) of the I in another’s voice: these were in the voice of a service user, an issue we briefly return to below. The primary function of the I social worker voice in case notes is to report action and communication, constituting 159 of the 197 instances, with other functions covered in the remaining 38. E-mails in contrast include a wider-range spread of the 6 identified functions, and with a much higher proportion of instances of reflection.

The I voice in children’s and adults’ care

With regard to the third text type, reports, action and communication functions are similarly foregrounded. However, significant differential patterns emerge once we compare the I voicing in reports written by social workers in Children’s and Adults’ Care. There is a much higher use of I in texts written by social workers in Adults’ rather than in Children’s Care (see ).

Table 3. I in reports in children and adults’ care.

However, the higher prevalence in texts written in adult services does not equate to a stronger presence of the social worker I voice. As indicates, in fact far fewer Is are in the social worker I voice in Adult Services than in Children’s Services.

Table 4. The who and function of I in reports in adults’ and children’s care.

The large number of instances of I in writing in adult services are in the voice of the service user as exemplified in . This practice seems to be in response to what is often referred to as a ‘person-centred approach’ or ‘personalisation’ (see for discussion Lymbery, Citation2012), where the individual user/citizen is positioned at the center of social work practice, and inscribed in the templates of the many documents social workers write into. For example, templated section headings include ‘About me’, ‘About my health conditions’. We return to this issue in the following section.

The my perspectival voice in children’s and adults’ care reports

What is noticeable from the social worker I analysis across all texts and domains is the lack of explicit statement of professional evaluation or analysis. We therefore also searched across adult and children’s reports for what we are referring to as ‘my perspectival phrases’, that is phrases which explicitly represent a social worker view (see ). There are two points to note: there is a higher raw number of such instances in reports written about children—the only instances (6) in adults were by one social worker; there is a wider range of my perspectival phrases in reports written about children. However, overall, the prevalence of such phrases is very low, at below 0.3 per 1000 words for each domain.

Table 5. My perspectival phrases in reports (children’s 162 adults 82).

We now turn to consider social worker perspectives on voicing in their writing and discuss findings and implications from both text and interview analysis in the following sections.

Findings from the interview analysis: social worker perspectives

The aim of this section is to make visible the range of meanings and orientations toward professional voice that are circulating in social worker practice, as reflected in the WiSP study. Perspectives are organized under key thematic headings.

Professional voice as factual and analytic

In discussions of professional voice/view in writing, a cluster of terms and phrases were used by social workers with a clear positive connotation. These were ‘factual’, ‘objective’, ‘analysis’:Footnote3

I just need to be factual. This happened, that happened, that happened (SWC 64)

I hope I write what is factual (SWA69)

You’ve got to be completely objective in what you write (SWA48)

We have to make sure it’s objective (SWA46)

Being factual and/or objective was often aligned with ‘analysis’:

We have to analyse everything. It is all factual. But at the end of the day that’s your role to do that, so we summarise and analyse. (SWC57)

And there was consensus that this factual analysis should always appear in particular types of writing, notably reports.

You know there’s never going to be a report without any analysis (SWC33)

The assessments is where we record our professional view. That’s an analysis of all of the information that we’ve collected. (SWC6)

Professional view as being factual, and often aligned with analysis, was considered essential in report writing, but there were different views as to whether ‘view’ should be in other texts. Some social workers considered the inclusion of view essential in all texts, including case notes:

I think you should put your view in each case note. (SWC64)

However, others did not see a place for professional view in case notes, foregrounding rather the recording of events and actions:

[in case notes] we tend to just put on what’s happened— We tend to only put our opinions and you know, judgements and stuff into our reports. (SWC5)

I don’t tend to put professional opinion in case notes. (SWC68)

For many, the function of case notes was to provide evidence of social worker actions

[in case notes] it’s more about evidencing that you’re doing what you should be doing, or that you’ve had a communication with somebody or things like that (SWC34)

The contested position of professional voice-as-opinion

In contrast to a cluster of terms that were used to align positively with professional view/voice– factual, analysis, objective, evidence, judgement– opinion is largely a negatively connoted term, along with personal and subjective. When voicing is construed as ‘opinion,’ or ‘personal’ rather than ‘factual’ or ‘analysis’, it is often viewed negatively, whether in case notes

You’ve got to be clear case noting not let anything personal in (SWA51)

and in writing more generally

Somebody might give an opinion, I don’t, but somebody might give an opinion — and I’m thinking well that’s not, that’s not right, you know that’s not on, don’t put your opinions (SWA54)

I try to avoid writing opinion (SWA56)

Criticism is made by some of other social workers’ writing that they consider to be ‘subjective’ which is contrasted with being ‘objective’:

I’ve seen lots and lots of very subjective records from the past —some really judgmental harsh comments and then you think well I hope we’re different now you know. (SWC41)

That’s where I think the responsibility in recording comes in, that it is objective (SWC37)

and reference is made to the need to make writing ‘less subjective’ (SWC4.)

However, including ‘opinion’ was considered to be a potentially legitimate dimension of professional voice by some, albeit, as one social worker remarked, ‘tricky’ to do (SWC7). The need to be cautious and also to explicitly mark professional opinion was stressed:

You do have to be careful because I think the main thing is —make clear that it’s your sort of opinion (SWA70)

Several social workers seemed ambivalent about the inclusion of professional opinion:

I don’t see why that would hurt, it’s an opinion it doesn’t mean to say that people are going to do what you think (SWA51)

I don’t know because, I don’t know, because I think I just had a negative experience of that so I’m not so sure at the minute (SWC57)

The ‘negative experience’ was a statement made by another social worker about the father of a young woman she was supporting who had made allegations of sexual abuse against him:

It said, ‘It is our professional opinion, that the dad was plausible. He was able to articulate himself and we believe that the young person was fabricating everything that was being said’. (SWC57)

The first social worker considered that the second social worker’s explicit inclusion of ‘professional opinion’ here was unjustified and represented a risk to the safety of the young person.

The absence of professional voice

Absence of the social worker’s voice was stressed by two social workers with team-leading responsibilities:

I’m constantly again getting people to, workers to put their own, put themselves into the — reports, and owning information better. Because I find that people shy away from that—, so ‘what do you think?’ Quite often reports will say ‘Fred says da, de, de’—. But after getting to know this person, after spending hours and hours with them, ‘What is your opinion?’ You can have whole assessments without any of that, I find. (SWC1)

Some are happier to give an opinion than others. I mean we’ve got somebody who is a qualified experienced social worker but is incredibly reluctant to ever give an opinion, on anything. —Sometimes we have to push the person, say for goodness sake just say, you know, very reluctant to say anything. But social workers are called upon constantly to make professional judgements, like whether somebody has mental capacity or not. (SWC30)

The team leader and manager here use a cluster of terms – opinion, professional judgement. owning information – to signal a professional voice that they consider to be essential but often missing in writing. In contrast to the negative, cautious or ambiguous connotations attached to ‘opinion’ in many interviews, here they construe ‘give an opinion’ positively as something the social workers should be doing.

Several possible reasons for this apparent absence of the explicitly stated social worker view are signaled in some social worker comments. Firstly, it may be that that professional view/voice is considered by writers to be implicit in everything that they write:

Professional view, of course. That’s the whole point why we’re here, isn’t it? (SWC4)

There’s always judgement (SWC20)

[even when describing] —we are writing in a way, using our professional judgment to say what that person needs to do to keep them safe and well (SWA53)

The assumption here seems to be that the reader will recognize the implicit professional voice underpinning everything that is written, and therefore the little need to make this voice explicit.

A second reason for the apparent absence of a professional voice as opinion or analysis is that it is happening, but not in writing. Some social workers indicated that it is part of ongoing individual thinking and reflection:

Usually when you’re doing case notes you’re just bashing it out so that you’ve got it done and there is no time to put your analysis in, your analysis stays in your head —You might be reflecting when you go home (SWC33)

Or, as indicated by some comments, professional voice is generated in interaction with others:

It’s [professional opinion] usually through informal conversation with managers (SWC25)

A third reason for the apparent absence of professional voice in writing may be ‘defensive recording’ (Lillis et al., Citation2012; Lillis, Citation2017). Some comments reflect social workers’ fear of explicitly stating their voice:

There’s been incidents where people get scared to put their own views and their own opinions in, and they feel they may get, scrutinised or criticised—wouldn’t stand up in a criminal court–. (SWC2)

I used to be scared to put my views in. I used to be really scared to put my views thinking, well I don’t know what I thought, I just thought I just need to be factual. This happened, that happened, that happened. I didn’t used to put my view. But now I put my opinion because it’s your professional judgement. (SWC64)

I think the difficult [thing] is the vulnerability that that puts you in as a worker, in committing yourself to a view — I could well be caught up on the stand at some point, -I feel quite vulnerable. It’s much safer, easier to record what you saw (SWC44)

Comments indicate the risks of explicitly stating a professional view—‘scared’, ‘vulnerable’– with the impact of institutional addressivity on social worker voicing, at the levels of contexts of culture signaled—‘the court’ (SWC2),‘on the stand’ (SW44). The impact of addressivity on professional voice at the level of context of situation is also signaled, through reference to the impact of specific managers:

I can see why some people don’t feel like they have a voice, a professional voice. I’ve known people in the past who’ve been told off for saying certain things —and so then they’ve kind of shut down a bit and, felt, hold back, basically hold back to what they really feel but more do it towards how managers feel (SWC7)

The reluctance to voice here seems to be aligned with suppressing an emotional dimension in writing, ‘hold back to what they really feel’, which contrasts with what is considered to be the more legitimate aligning of voice with factual and analysis exemplified above. The suppression of the expression of social worker feelings was viewed by one social worker as an important way of avoiding misrepresentation of a person or situation:

If I put, ‘it made me feel really scared, she really, really worried me’, then what if another worker goes out in three days and then they’re automatically worried when she might not be like that— if I then put my feelings into it, I [might] make it sound a whole lot worse (SWC65)

A fourth reason for the potential absence of voice in writing may be linked to social workers’ sense of a lack of a legitimately recognized expertise, evident in the social worker's repeated comment below, ‘we can’t’:

I guess —we’re not seen as an expert in any particular theoretical model—. We can’t say this is a secure attachment because we’re not trained in it and we don’t, we can’t assess that. We have to talk about relationships. But we’re still using attachment theory all the time— We just can’t say that we’re using it. (SWC6)

The impact of envisaged others, addressivity at the level of context of culture, is foregrounded implicitly by SWC6, ‘we’re not seen’, indicating society in general. This lack of socially recognized expert knowledge-discourse in terms of theory and research in professional writing is linked, for one social worker, with the overall low status attached to social work, signalled in the reference to 'they':

I like the writing where I can use my social work skills— so recently I’ve had to, I disagreed with the mental health team about what constitutes a mental disorder—I quoted my knowledge base so I kind of do like doing that sort of writing—but it’s very rare—. And I think because they think anyone can do the job then you don’t really need a social work opinion (SWA55)

One social worker however indicates why the explicit statement of theories may be unhelpful in relation to addressivity at the level of context of situation, thinking about the family she is currently working with:

And I think that it’s always useful in social work to think about the theories that you’re using that underpin the practice, but in the actual recording of assessments it’s rarely used. I’ve seen some social workers that have used it but I tend to find that you can slip yourself up a lot from using it… I’ve had a family and they’ve read it and been like who’s this person?who’s this?—it baffles them. (SWC60)

Explicit marking of professional voice in the first person

Where social workers felt it was appropriate to express what they considered to be professional opinion, some stated they would explicitly mark this through use of a my perspectival phrase, e.g. ‘in my opinion’, or in a separate part of a text, often at the end of a document:

In my professional opinion—but it needs writing and I think it does need clarifying which is fact and which is opinion (SWA51)

So I try and be quite explicit, and be explicit what is fact and what is opinion, and I try and do it in different paragraphs. So the factual thing of what happened and then use quite overt language like, it seems to me, or in my professional view or it is my assessment that or, just to make it quite clear what I’m saying is my opinion, to differentiate it from fact. (SWC11)

Social workers talked of marking opinion from factual description by textual positioning or layout: placing opinion at the end of a text (SWC26, SWA27), or using square brackets around opinion (SWC15, SWC21).

However, some stated they did not use the first person to voice their professional view:

I don’t actually write in the first person but —some of my colleagues do. (SWA46)

I don’t write in the first person. I tend to keep it in the third person—I don’t often need to put myself into it and I tend to keep it quite factual really. If there’s an observation to make about how somebody appears I’ll say ‘they appear to be this way’ (SWC41)

Writing in the third person is often construed as more factual and as sounding more professional although this is challenged by others:

Often people are told, I think wrongly, to write in the third person— I always wrote my court reports in first person, but other people would be adamant that it needs to be third person, so I guess again it depends on what advice you’ve had (SWC1)

Where there seems to be clear guidance to use the first person I is in Adult Care, but not in the first person of the social worker but in the first person of service users, as mentioned above. This was referred to as an issue of some debate:

We have many a discussion [about writing in voice of service user] in the office (SWA46)

I’ve heard from other, from other social workers and that, that theirs get sent back if they’re not written in ‘I’ form, first person format. (SWA49)

with the same social workers expressing some unease, for example:

I think the guidance has been we should try to write in the first person but it’s not something I feel comfortable with, so I don’t—because I think you can still be person centred without using I or me and that sort of thing. (SWA46)

echoed by others who question the ethics of such practice:

What can happen is you’ll find someone who isn’t able to communicate their own needs and wishes —and an assessment is done and rather than putting the social worker’s perspective, ‘such a person needs this’—they’ll put in ‘I have this disability, I want this to happen, I need this’. And I don’t think that’s appropriate, because you’re essentially putting words in somebody’s mouth (SWA48)

Discussion

The WiSP study, the first nationally funded England-based study to explore professional social work writing and on which this paper is based, seeks to redress the lack of research attention on professional social work writing and the deficit orientation often evident in public media and official reports. A key finding from the larger project is that social work is de facto a ‘writing intensive’ profession (Lillis et al., Citation2017), in terms of time spent on writing and its centrality to everyday practice. Writing is therefore not marginal, but rather a key site of the enactment of professional identity and professional practice and, as such, an important topic of concern for social work education and ongoing professional development. The specific questions, analysis and findings reported in this paper are intended as a first step contribution toward understandings about the ways in which a social worker’s professional identity—their sense of self as a social worker—is enacted and implicated in written discourse: the robust descriptions presented in this article, based on the identification and quantification of specific key textual features, and the qualitative thematic analysis of interviews, constitute baseline findings which we hope will lead to further research.

From the textual analysis, six key functions of the social worker I voice emerged, centering on action, communication, reflection, emotion, presence and state of affairs. Overwhelmingly the social worker I voice is that of a reporter of actions and communications—between social worker and others, and between others. Such reporting amounts to the social worker providing an account of practice but also constitutes an account for their practice, as emphasized in interview comments about the need to evidence actions and be recognized as legitimate by institutional addressees, notably managers and courts, supporting findings by Hall et al. (Citation2006). Far less visible is the social worker voice as expresser of emotions, or as reflective practitioner, although these are strongly present in e-mails. The extent to which the expression of emotion or explicit subjective engagement should be present across genres is an issue of ongoing debate (e.g Lillis and Rai, Citation2012; Rai and Lillis, Citation2013).

Largely absent from all texts and domains is the social worker voice as explicit evaluator or analyst, either as I or in my perspectival phrases. This low explicit presence of social worker as analyst or evaluator provides some textual evidence for concerns expressed by team leaders, emerging from interview data, about some social workers being ‘very reluctant’ to say anything, echoing existing findings from a previous study documenting similar concerns by managers (Lillis, Citation2017). The team leaders’ expectation that social workers should ‘put themselves into’ writing signals their desire to see the social worker voice as one which is explicitly implicated in writing through the explicit taking up of a position, rather than as reporter-observer. In contrast, findings from the interview analysis with social workers provide a range of possible reasons for any such absence: the belief that explicit view is not appropriate in all texts, the limited time available to include analysis, the suggestion that social workers are not recognized as experts in any field of knowledge and therefore cannot legitimately claim a specific voice. The impact of the specific social context in which social workers practice and write is evident in comments signaling the impact of addressivity on voice, at the levels of context of situation (e.g. a specific manager) and context of culture (e.g.courts, society) and can be used to explain why in some instances social workers, as one person said, ‘shut down a bit and—hold back’.

Whilst the text data and analysis can enable us to identify patterns in what is written, thematic interview analysis sheds some light on why texts are written as they are. Interview analysis indicates that there is both consensus and disagreement about the meanings and discourses attached to ‘professional voice’. There is strong consensus that the professional voice as ‘factual’ is a legitimate social worker voice, with ‘factual’ often aligned with ‘analysis’, although the explicit analytic voice seems largely absent in texts. A cluster of binary terms are used to signal the kind of social worker voice that is considered legitimate, as compared with what is not: objective rather than subjective, factual rather than opinion. The factual orientation emphasized in interviews may account for the overall low incidence of the social worker I voice within written texts (other than e-mails) and within these, the high incidence of the I voice as a reporter of action (in contrast to expression of analysis, reflection or emotion).

However, it is also clear from the interview data that the often-used binaries factual/opinion, objective/subjective are contested rather than stable notions, with ‘opinion’ being used both negatively and positively to signal the inclusion of social worker voice, echoing the contrasting views on whether or not to use the first person. The different views around the explicit expression of social worker voice underscore the tensions surrounding what it means to enact an ‘authentic’ self in professional writing (McDonald et al., Citation2015): whilst authenticity may be seen as a core ethical value, it remains to be debated how such authenticity can be legitimately expressed in social work writing. Such tensions also lend support for the need to rethink the objective-subjective dichotomy commonly used in social work, which requires social workers to be empathetic in their engagement with people but to remove themselves in writing reports (Munro & Hardie, Citation2019, p. 412).

Whilst the focus in this paper has been on the social worker voice as I, the representation of other voices as I has also emerged as a problematic practice: in adult care social workers are often advised to write in the first person of the adult but some feel this is inappropriate and is simply ‘putting words in somebody’s mouth’. The representation and expression of multiple voices in social worker writing is increasingly of concern to practitioners (see for example Lillis et al., Citation2023, pp 17–18) and merits further research and critical practitioner engagement.

Together, the textual and interview data in this paper provide a window onto points of consensus and debate about professional voice in writing. Of course there is considerably more research still to be done, not least to explore the perspectives of the multiple addressees of social work writing – including the people who the writing is about and their friends, families and advocates; colleagues from social work and other services such as health; magistrates and panel members – and the specific voices that different writers and addressees would like to see represented in written texts. We hope this paper will constitute a contribution to a larger discussion around what it means to be- and enact in writing- a social worker, in contemporary practice.

Implications for social work education

There is an increasingly acknowledged widespread lack of attention to professional writing within social work education programmes and ongoing professional development (Healy & Drayton, Citation2022); where writing does figure it is often treated as an underpinning, procedural skill, rather than as a complex enactment of professional identity and, thus, of professional social work practice (Paré & Le Maistre, Citation2006; Lillis & Rai, Citation2012). Yet how social workers position themselves in their writing has profound consequences for themselves as professionals, signaling the extent and ways in which they claim (or not) understanding, authority, knowledge and legitimacy. Social worker explicit positioning in writing also has consequences for the people they are working with in at least two ways: 1) at a more immediate practical level, the explicit positioning (or invisibility) of the social worker view in writing may impact on decisions about resource allocation and support; 2) at an ethical-relational level, specific kinds of explicit social worker positioning constitute particular representations between self and others, notably relationships of care, an area of recording that is receiving considerable criticism, with calls for greater textual evidence of emotional engagement (evident in works such as Sissay, Citation2020; and the focus of ongoing policy and practice, see for example; TACT, Citation2019).

Our hope is that findings from this study may contribute to positioning writing as a fundamental but complex dimension to social work practice which demands critical engagement in social work education and across social worker professional trajectories. Specifically, we consider that the data, findings and analysis in this paper might be used as resources for learning in the following three ways:

To make visible the ways in which the social worker I and my perspectival voice are currently used in professional written discourse. Key points to discuss would be whether the six key functions identified here are those which (prospective) social workers should, or want to, use or whether for example, other functions might be more meaningful for both social workers and service users. These might include more categorical voicing of analysis and evaluations, and/or of emotions and personal engagement with people, across a wide range of texts. Opening up debate about explicit social worker positioning in writing contributes to the larger discussion about the ‘use of self’ (Gordon & Dunworth, Citation2017) in social work education and practice.

To make visible points of consensus and contestation amongst social workers about their positioning within written texts. This would include discussion around the range of views on the I in writing, and the value of using I in representing another’s voice (such as that of the person being cared for); deeper exploration of what it means to express or to silence a professional opinion; the usefulness or not of commonly used binaries when conceptualizing voice, such as subjective/objective, opinion/factual, and whether these mask and/or facilitate choices and decisions to be made by individual social workers in their writing.

To encourage and facilitate explicit discussion about the meanings and consequences of voice in written discourse. The heuristic in could be used to generate discussion about social worker presence and positioning in written texts asking specific questions such as: why use this word/phrase here? how is such wording perceived by different readers, and why? (see for example young people's perspectives, TACT, Citation2019; or judges' perspectives, Community Care, Citation2018b); to what extent is specific voicing shaped by personal experience and histories, as well as institutional practice? whose voices are/should be included or excluded and why?; what is the impact of real and imagined addressees and the specific ways these impinge on social work voicing and why?. And a fundamental question- who am I as I write?

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Preregistered. The materials are openly accessible at http://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/853522/.

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Preregistered. The materials are openly accessible at http://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/853522/.

Acknowledgments

The WiSP research project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The research was carried out by Theresa Lillis, Maria Leedham and Alison Twiner. We would like to thank the participating local authorities and the social workers who so generously took part in the project but who have to remain anonymous for confidentiality reasons. We would also like to thank Dana Therova for support in carrying out the corpus analysis and Hannah Lineham for support in carrying out a literature review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The WiSP study explored writing in three domains of care: children's, adults, and adult mental health. For the purposes of this paper we have combined figures for adult generic and adult mental health care, in order to provide a contrast between texts written about children and adults.

2. Interviews were transcribed using broad transcription conventions, using standard punctuation and orthography, and square brackets for inaudible talk and extended pauses.

3. Social workers are identified as working in Children’s -C, or Adults’ Care-A. Boldings are used by us to emphasise key wordings. Dashes indicate text removed in order to maximise number of extracts to be included given limits on article word length.

References

- Almeida, R., Werkmeister Rozas, L. M., Cross-Denny, B., Kyeunghae Lee, K., & Yamada, A. (2019). Coloniality and intersectionality in social work education and practice. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 30(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428232.2019.1574195

- Amas, D., & Fox, J. (2023). Telling stories of practice in the neo-liberal context of English social work. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(6), 3289–3304. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad096

- Baker, P. (2023 online access). A year to remember? Introducing the BE21 corpus and exploring recent part of speech tag change in British English. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 28(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.22007.bak

- Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination ( C. Emerson, & M. Holquist, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays ( V. W. McGee, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Balkow, M. & Lillis, T.(2019). Social Work Writing and bureaucracy a tale in two voices. A discussion paper from the centre for welfare reform, www.citizen-network.org

- Banks, S. (2020). Ethics and values in social work. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse. CUP.

- Brezina, V., Weill-Tessier, P., & McEnery, A. (2021). #LancsBox V. 6.X. Software.

- Care Quality Commission. (2017). The state of adult social care services 2014-2017. Findings from CQC initial programme of comprehemsive inspections in adult social care. https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/major-report/state-adult-social-care-services-2014-2017

- Community Care. (2018a). Retrieved June 6, 2023, from https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2018/05/10/divisivedemeaning-devoid-feeling-social-work-jargon-causes-problems-families/

- Community Care. (2018b). Retrieved June 6, 2023, from https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2018/06/28/social-workersshouldnt-use-attachment-records-reports/

- Cree, V. E. (2013). Becoming a social worker: Global narratives. Routledge.

- Department of Education. (2011) . The Munro review of child protection. HMSO.

- Dominelli, L. (2017). Feminist social work theory and practice. Bloomsbury.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

- Fearnley, B. (2022). Becoming a reflexive and reflective practice educator: Considering theoretical constructs of Bronfenbrenner and Bourdieu for social work student field placements. Social Work Education, 41(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1796954

- Forenza, B., & Eckert, C. (2018). Social worker identity: A profession in context. Social Work, 63(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx052

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

- Gordon, J. (2018). The voice of the social worker: A narrative literature review. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(5), 1333–1350. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx108

- Gordon, J., & Dunworth, M. (2017). The fall and rise of “use of self? An exploration of the positioning of use of self in social work education. Social Work Education, 36(5), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2016.1267722

- Hall, C., Slembrouck, S., & Sarangi, S. (2006). Language practices in social work: Categorisation and accountability in child welfare. Routledge.

- Hamilton, R. (2019). Work-based learning in social work education: The challenges and opportunities for the identities of work-based learners on university-based programs. Social Work Education, 38(6), 766–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1557631

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice. Routledge.

- HCPC Health and Care Professions Council. (2018). Fitness to practice annual report 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from https://www.hcpc-uk.org/resources/reports/2018/fitness-to-practise-annual-report

- Healy, K., & Drayton, J. (2022). Mind the gap: Incorporating writing skills into practice simulations. Social Work Education, 41(8), 1802–1820. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1962270

- Healy, L. M., & Link, R. J. (Eds). (2011). Handbook of international social work: Human rights, development, and the global profession. Oxford University Press.

- Horner, B., & Lu, M. (Eds.). (1999). Representing the “other”: Basic writers and the teaching of basic writing. National Council of Teachers of English.

- Huuskonen, S., & Vakkari, P. (2015). Selective clients’ trajectories in case files: Filtering out information in the recording process in child protection. British Journal of Social Work, 45(3), 792–808. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct160

- Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity. The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Latour, B. (2004). Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern. Critical Inquiry, 30(2), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/421123

- Leedham, M., Lillis, T. & Twiner, A. (2020). Exploring the core preoccupation of social work writing: A corpus-assisted discourse study. Journal of Corpora and Discourse Studies, 2(1), 1–30.

- Lillis, T. (2001). Student writing: Access, regulation, desire. Routledge.

- Lillis, T. (2013). The sociolinguistics of writing. EUP.

- Lillis, T. (2017). Imagined, prescribed and actual text trajectories: The ‘problem’ with case notes in contemporary social work. Text & Talk, 37(4), 485–508.

- Lillis, T. (2023). Professional written voice “in flux”: The case of social work. Applied Linguistics Review, 14(3), 615–641. https://libezproxy.open.ac.uk/101515/applirev-2021-0055

- Lillis, T. & Curry, M. J. (2010). Academic writing in a global context. Routledge.

- Lillis, T., Leedham, M. & Twiner, A. (2017). If it’s not written down it didn’t happen’: Contemporary social work as a writing-intensive profession. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 14(1), 29–52.

- Lillis, T. & Rai, L. (2012). Quelle relation entre l’écrit académique et l’écrit professionnel? Une étude de cas dans le domaine du travail social. Pratiques, 153/154, 51–70.

- Lillis, T. Rai, L. & Garcia-Maza, G.(2012) Action research project on case notes recording. Internal report for a local authority in partnership with the Open University.

- Lillis, T., Twiner, A., Balkow, M., Lucas, G., Smith, M. & Leedham, M. (2023). Reflections on the procedural and practical ethics in researching professional social work writing. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 17,2. https://doi.org/10.1558/jalpp.20014

- Lymbery, M. (2012). Social work and personalisation. British Journal of Social Work, 42(4), 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs027

- McDonald, D., Boddy, J., O’Callaghan, K. & Chester, P. (2015). Ethical professional writing in social work and human services. Ethics and Social Welfare, 9(4), 359–374.

- Moorhead, B., Bell, K., Jones-Mutton, H., & Bailey, R. (2019). Preparation for practice: Embedding the development of professional identity within social work curriculum. Social Work Education, 38(8), 983–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1595570

- Munro, E., & Hardie, J. (2019). Why we should stop talking about objectivity and subjectivity in social work. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(2), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy054

- Ofsted. (2019). Retrieved June 4, 2023, from https://socialcareinspection.blog.gov.uk/2019/07/24/what-makes-an-effective-case-record/

- Paquette, J. (2016). Cultural policy, work and identity. The creation, renewal and negotiation of professional subjectivities. Routledge.

- Paré, A., & Cathrine Le Maistre, C. (2006). Active learning in the workplace: Transforming individuals and institutions. Journal of Education & Work, 19(4), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080600867141

- Rai, L. & Lillis, T. (2013). “Getting it write” in social work: Exploring the value of writing in academia to writing for professional practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(4), 352–364.

- Roesch-Marsh, A. (2016). Professional relationships and decision making in social work: Lessons from a Scottish case study of secure accommodation decision making. Qualitative Social Work, 17(3), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325016680285

- Roets, G., Roose, R., De Wilde, L., & Vanobbergen, B. (2017). Framing the ‘child at risk’ in social work reports: Truth-telling or storytelling? Journal of Social Work, 17(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316644864

- SCIE. (2016). Practice issues from serious case reviews 13. Euphemistic language in reports and written records. Retrieved June 7, 2023, from https://www.scie.org.uk/children/safeguarding/case-reviews/learningfrom-case-reviews/13.asp

- Scott, M., (2022) WordSmith tools version 8 ( 64 bit version) Lexical Analysis Software.

- Sissay, L. (2020). My name is why. Canongate.

- TACT. (2019). https://www.tactcare.org.uk/content/uploads/2019/11/Language-That-Cares

- Thesen, L., & van Pletzen, E. (Eds.). (2006). Academic literacy and the languages of change. Continuum.

- Tuck, J. (2018). Academics engaging with student writing: Working at the higher education textface. Routledge.

- Webb, S. (Ed). (2017). Professional identity and social work. Routledge.

- Webb, S. A. (2016). Professional identity and social work. In S. Webb (Ed.), The Routledge companion to the professions and professionalism (pp. 355–370). Routledge.

- White, S., Wastell, D., Broadhurst, K., & Hall, C. (2010). When policy o’erleaps itself: The “tragic tale” of the integrated children’s system. Critical Social Policy, 30(3), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018310367675

- Wiles, F. [email protected]. (2013). Not easily put into a box’: Constructing professional identity. Social Work Education, 32(7), 854–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.705273

- WRAM (Write right about me). (2023) https://www.aberdeencity.gov.uk/Aberdeen-Protects/improving-childrens-futures/write-right-about-me

- Zavala, V. (2011). La escritura académica y la agencia de los sujetos. Cuadernos Comillas, 1, 52–66.

![Figure 3. I voices in adults’ reports [concordance lines].](/cms/asset/74df90b6-996f-4f7c-a917-a9d0d7348326/cswe_a_2314608_f0003_b.gif)