ABSTRACT

In line with the digital turn in service provision, social work students should acquire relevant knowledge and skills, preparing them for work within digitalized welfare services. In Norway, these expectations are articulated in a national learning outcome (LOC) that addresses digital competence and the ability to assist in developing and using technology. Previous research has revealed digital knowledge gaps between education and practice . Here, we explore how social work educators perceive of and engage with digital competence as expressed in the LOC. Through focus group interviews with social work educators in Norway, we discovered that the knowledge gap is linked to five key findings: (a) uncertainty about the content of the LOC, (b) unfamiliar technical language, (c) the rapid development of digitalization, (d) the distribution of responsibility and (e) critical reflection. Critical reflection is expressed as a solution to the challenges. We argue that there must be knowledge about the subject matter (digital competency) that provides a foundation for such critical reflection (digital literacy). More conceptual clarity is needed regarding the LOC and what digitalization means in an educational context, in order for both digital competency and digital literacy to take their natural place in education.

Introduction

Digital developments have changed society and welfare services at a rapid pace and will continue to do so. Norway’s ambition is to be at the forefront internationally in using new technologies in public health and social welfare services (Meld. St. 27, Citation2015–2016; Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, Citation2019). The main objective is to offer accessible services through digital interaction with the country’s citizens, and to improve welfare sectors’ efficiency, accountability and monitoring (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022, p. 823). The European Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp) offers ‘a tool to improve citizens’ digital competence’. The framework states five core competence areas for European citizens: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety and problem solving (Carretero et al., Citation2017).

However, it is not only citizens who are affected by digitalization in society. The introduction of information and communication technology (ICT) in welfare services represents a substantial shift from a traditional government to an e-government, with consequences for the role of the street-level bureaucrat (Bovens & Zouridis, Citation2002; Buffat, Citation2015; Lipsky, Citation1980). Traditionally, social workers were perceived as street-level bureaucrats implementing welfare policy in front-line services, such as the Norwegian Child Welfare Services (Barnevernet) and the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV), where they provided social work services to their clients in their offices, face to face. Today, digital competences are a requirement for frontline social workers, as ICT is increasingly used in the field for service delivery, case management, administration, collaboration and communication with clients (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022). In line with the increased use of digital media, the expectations of both service recipients and professionals within social work are changing (Kvakic et al., Citation2021).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic reminded us of the urgency to keep up with technological developments (Taylor-Beswick, Citation2022; Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023). Social workers witnessed the impacts of the pandemic, especially for vulnerable groups, and experienced increased pressure to transform their practice and implement digitalized services (Heinsch et al., Citation2023). Today, social workers provide services to clients by using technology, such as videoconferencing, chat-based digital platforms, mobile apps and text messages (García-Castilla et al., Citation2018). Transitioning from face-to-face to digital care is a complex process. Employees in the welfare services must continuously improve their digital competence to be commensurate with technological developments in society, enhance service quality and support digital interaction with their clients (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022).

This rapid technological development places great responsibility on social work education to equip future social workers for work in a digitized workplace and to meet modern society’s needs (Taylor, Citation2017; Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023). According to Castillo de Mesa and Jacinto (Citation2022), social work—both as a discipline and a profession—must ‘embrace digital transformation and consider it an opportunity’ and, consequently, ‘social work training programmes must include new methodologies, content and competences’ (p. 222). Internationally, social work education is regulated by the Updated Global Standards (Commission International Association of Schools of Social Work and International Federation of Social Workers- Interim Education, Citation2020; Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023), in which digital competences are defined as one of the essential competences in lifelong learning. Norwegian social work education is further regulated by a set of national guidelines (Forskrift om felles rammeplan for helse- og sosialfagutdanninger, Citation2019), with the aim of securing the expected learning outcomes considered particularly significant for social workers. The regulations state that the candidate should be able to ‘master digital tools, including knowledge of digital security, and can assist in the development of and use suitable technology, and is familiar with their opportunities and limitations in social work’ (Chapter 3: § 8, n)—and, moreover, should have ‘insight into the importance of digital communication in professional practice and interaction’ (Chapter 3: § 9, e).

The aim is to offer education that is relevant to and in line with the digital development of the services. However, there has been scant inclusion of digital competence in social work education (Taylor-Beswick, Citation2022; Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023). While the use of technology in social work practice has increased, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains a widespread gap in social work education and training on how to use digital technologies effectively and ethically (Heinsch et al., Citation2023). This highlights an urgent need for further insights into social worker education, in order to adequately prepare social work students for the realities of digital service provision (Heinsch et al., Citation2023; Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023).

In this context, teachers’ perceptions of what digital competences entail for their pedagogical practices are important. We thus ask the following question: How do educators in Norwegian social work education perceive of and engage with digital competence as expressed within the national guidelines?

Digital competence in social work and social work education

Several attempts have been made to formulate a unifying definition of the term ‘digital competence’ (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022). Although no consensus yet exists, digital competence indicates that ‘the digital’ must be understood broadly, and as a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes that all citizens need to be able to use digital media in a knowledge society (European Commission, Citation2019b). Since 2006, the European Union (EU) Policy Agenda has declared that digital competence is one of the eight key competences for lifelong learning for all European citizens (European Commission, Citation2006), describing it as the confident, critical and responsible use of, and engagement with, digital technologies for different purposes (European Commission, Citation2019a). The Norwegian government’s definition, in accordance with the EU, describes digital competence as ‘the ability to relate to and use digital tools and media in a safe, critical and creative way’ (Government.no, 2012, p. 18). They both indicate a two-fold approach.

On the one hand, digital competence refers to basic technical knowledge and skills, as well as the ability to use a given technology (Wolf & Goldkind, Citation2016). Mastering elementary ICT skills involves the ability to (a) use appropriate software for problem solving and (b) navigate to find relevant information on the internet (Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023). In our survey, this was thematized through a delimitation of the division of responsibility between the educational institutions and the field of practice. On the other hand, digital competence also involve a digital mind-set (Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023). Wolf and Goldkind (Citation2016) refer to this as ‘ICT literacy’: ‘the ability to access, manage, integrate, evaluate, and create information’ (p. 102). ICT literacy includes communicative competence, source criticism, interpretation and digital judgment. Digital literacy entails being able to navigate safely and constructively in a digital everyday life, independently and reflectively, and being able to participate on the internet as a public space, where attitudes are important. Competency and literacy are both necessary pedagogical goals in training social workers. Although competency allows a practitioner to make use of a specific technology, literacy ensures the ability to interrogate its congruence with ethical practice (Wolf & Goldkind, Citation2016).

We adopt this general understanding in this article. However, with our participants, we aimed to maintain an open attitude toward their perceptions of digital competence, as well as how they understand and meet the new requirements for digitalization competence in education. It was the informants’ own understandings of digital competence that were expressed in the interviews, and which form the basis of our analysis. After all, ideas about digital competence depend, among many other things, on how one defines digital competence—around which no general consensus yet exists.

Previous research

Although research finds that recent developments in digital service provision require new skills (Fugletveit & Lofthus, Citation2021), few studies have examined what knowledge and skills social workers must possess in order to work within the digitized welfare society of today and of the future (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022). Many studies, however, are concerned with how digitalization affects social work practice. Some are concerned with client groups’ knowledge of digitalization or their lack of digital competence (Fugletveit & Lofthus, Citation2021), others with how digitalization affects practices and service provision (Aasback, Citation2022; Bovens & Zouridis, Citation2002; Buffat, Citation2015; Busch-Jensen & Kondrup, Citation2015; Mishna et al., Citation2012), and still others with whether digitalization will replace digital discretion (Busch & Henriksen, Citation2018).

Research on child welfare services in the United Kingdom has revealed that ICT may contain latent conditions for error which impede rather than enhance service provision (see, e.g. Broadhurst et al., Citation2010; Peckover et al., Citation2008; Pithouse et al., Citation2009). However, other research shows that the use of ICT can relocate power from the bureaucracy to the clients (Gillingham, Citation2011; Svensson & Larsson, Citation2018), thus increasing the availability and transparency of online information and reducing the asymmetry of information between clients and social workers, giving clients ‘powerful action resources’ (Buffat, Citation2015, p. 157). The use of social media actualizes privacy issues and dilemmas concerning confidentiality, transparency, consent, user participation and trust. Accordingly, several studies have raised ethical questions regarding child protection workers’ use of social media information (Cooner et al., Citation2020; Kvakic & Wærdahl, Citation2022). This research has important implications for pre- and post-qualifying social work education, which must meet society’s needs in line with digital developments: Social workers must develop digital competences and be prepared to operate in a socially networked society (Cooner et al., Citation2020; Zemaitaityte et al., Citation2023).

Nevertheless, there is a lack of research related to digitalization in social work education. Some studies emphasize that education programmes are responsible for developing a digital ‘mindset’, or digital literacy, as the use of ICT raises ethical and legal issues. They remind us that social workers should be able to consider the risks, benefits and conditions associated with using ICT (Aasback, Citation2022; Mattison, Citation2018; Reamer, Citation2018), to ensure that their practice complies with ethical standards. According to Aasback (Citation2022), ‘social work, both as a practice field and as a research field, needs to be aware of how the socio-technical assemblages in these platforms have political impacts and influence practices in unintended ways’ (p. 361).

Two more recent studies are of particular interest to our research. Taylor-Beswick (Citation2022) asked students who have completed a social work education programme ‘how digital development was experienced throughout the course of their professional training’ (p. 10). She found extensive digital knowledge and skills gaps among study participants and that digital development still lags across the profession. She concludes that ‘the need to understand how social work education is preparing students of social work to engage with a digitally saturated world continues to feel urgent’ (Taylor-Beswick, Citation2022, pp. 2–4). Zhu and Andersen (Citation2022) used a multi-methodological approach that included semi-structured interviews with social work educators at a university in Norway. They, too, were concerned with the gap between education and practice and inquired into how local social work education can better facilitate students’ digital competence in line with the European Commission’s requirements and the reality of front-line practice. The authors found that, although attention to digitalization has increased over the last five years, digital competence still lacks a prominent position in the curricula, and that ‘integrating digital competence knowledge areas into Norwegian social work education is still limited’ (p. 835). They conclude that digital competence needs to be better integrated into social work programmes so that students can meet the requirements of society (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022).

In summary, research highlights a gap between the competence provided through social work education and the expectations in the practice field. This implies a need to modify and adjust training schemes for social work students (García-Castilla et al., Citation2018).

Material and methods

As part of a different research project, a survey was carried out among course coordinators in social work and child welfare education programmes at universities and university colleges in Norway. The intention was to gain a broad overview of how knowledge about digital competences has been implemented at the bachelor’s level in social work. The respondents indicated a gap between the national guidelines and the educational practices due to lack of knowledge about digitalization. Unfortunately, further exploration of this part of the survey was not possible at that time. As part of a new research project—this time based on a qualitative methodology (i.e. focus group interviews)—we explored the topic further, to gain a deeper understanding of how educators relate to demands for digitalization-related teaching. Focus group interviews have the advantage that they can capture opinions and meanings in informants’ interaction (Tjora, Citation2021). This suited our project well, as it is our belief that communication between the group participants can bring out more breadth and nuance in the discussions of the topics that are introduced.

A total of three focus group interviews were conducted with educators at three different universities in Norway. The universities were selected based on two simple criteria for selection: First, the universities had to offer education in both social work and child welfare at the BA level. Second, they had to be located in the south of Norway. As it is not advantageous to conduct focus group interviews online, the selection was limited to universities within reasonable travel distance. Five universities met these criteria, and three of them agreed to participate. The criteria for selecting focus group participants were that they were teaching relevant courses at the social work and child welfare programmes. Using the snowball sampling method, they were recruited through key individuals in the research groups’ network, who then invited colleagues at their workplace to participate. In total, 18 course coordinators participated, all of whom are teachers in social work or child welfare education.

As we sought the participants’ intuitive reflections and opinions, a semi-structured interview guide consisting of key topics was developed. The first topic was whether the digitalization of the welfare services had become important for the development of the new programme plans. Was it, for instance, reflected in the subjects’ learning outcomes or in the curriculum? The second topic concerned the participants’ reflections on when, during the education programme—and associated with which subjects and pedagogical methods—they thought teaching about digitization would be relevant (as the incorporation of the learning outcome (LOC) may vary across the educational institutions). We then wanted them to discuss what digital competence entailed for them. This topic also included their thoughts on teaching students the ability to reflect critically, followed by an investigation into how students can acquire digital and critical competences. Finally, we asked: Given that the adaptation of the LOC remains incomplete or haphazard, what is needed for the LOC of digital competence to be strengthened in the education programme?

The focus group interviews were led by two moderators (members of the research group) and lasted approximately one and a half hours. After a brief introduction, the moderators introduced the key topics and invited the groups to freely discuss their opinions related to the topics. This provided the groups with ample opportunity to discuss issues close at heart, with little interruption on our part. However, the moderators actively steered the discussion ‘back on track’ when necessary and secured all informants’ involvement, as advised by Tjora (Citation2021). We also asked follow-up questions when we wanted to explore certain topics more in-depth. Each interview was transcribed by a research assistant and analyzed by two research group members using manual coding and NVivo qualitative research software. The first coding cycle was based on a close reading of the material to find logical patterns in the transcripts and to define the preliminary codes. It resulted in the following keywords: digital skills, knowledge, competences, barriers, social work practice, digital security, digital judgment, digital tools, software, ethics and digitalization. We then read and re-read the transcripts to identify relationships and patterns between them and synthesize the keywords into code groups/themes. The results of the second coding cycle formed the basis of the findings and the five main topics relating to the knowledge gap theme.

Ethical considerations

We do not consider social work educators to be a particularly vulnerable group, nor did any participant express that the topic was emotionally or in any other way uncomfortably challenging for them to discuss. On the contrary, the participants stated that it was important for them to have time to discuss this topic together. It raised awareness and inspired them to continue the work with colleagues afterward. To protect the informants’ anonymity, there is no link to name, gender, age or workplace. The Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research approved the data collection process.

Findings

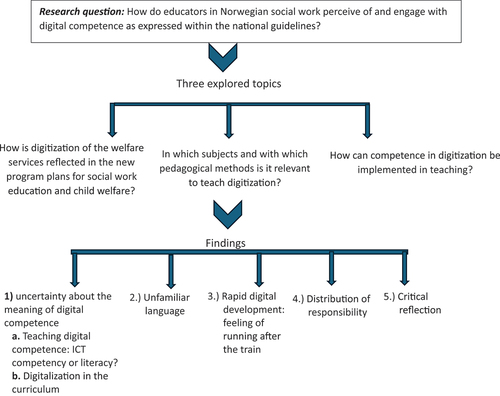

As earlier research on digitalization in social work education has established, a major topic related to digitalization is the experience of a knowledge gap. A knowledge gap, in this context, is understood as a discrepancy between a social work educator’s actual digital knowledge and what they need to know to teach the topic of digital competence. This is in accordance with Zhu and Andersen (Citation2022), who identified a gap between what has been addressed in education and what is expected in the front-line practice at NAV. The educators in our material related this gap to five themes: (a) uncertainty about the content of the LOC, (b) the unfamiliar technical language, (c) the rapid development of digitalization, (d) the distribution of responsibility and (e) critical reflection, as illustrated in . Each topic is closely interrelated, but will be discussed separately in more detail in the following analysis.

Figure 1. Overview of research question, topics and findings.

Uncertainty about the meaning of digital competence

Uncertainty related to the meaning of the concept ‘digital competence’, as formulated in the LOC, was a significant issue that came to the foreground in all the focus group sessions. What is meant by digitalization and digital competence in social work and education? How can we reach an understanding about digital competence? All participants expressed a need for more clarity with regards to understanding the relevant concepts and how to teach digital competence: ‘It’s about a lot of things on many different levels… So I feel I am missing the basics so that we have a common understanding of what we are talking about when we talk about what digital competence is within social work’ (I-3).

Despite the uncertainty from lacking a common understanding, the informants were all concerned with the possible effects of digitalization. Their concerns were based on what we consider to be an implicit understanding of digitalization as a challenge. This concern was raised from a professional perspective and a client perspective, with an emphasis on service delivery.

From a professional perspective, the groups discussed the challenges social workers face when interaction with clients is transferred to digital platforms. We interpret this as a concern related to doing the social and relational work and the ethical base of social work: how to safeguard clients’ interests when they are not meeting face to face. From a client perspective, one of the topics discussed was the effect on social work clients, as digitalization leads to an increased standardization of welfare services. They further expressed a concern that digital skills are unevenly distributed in the client group and that many cannot use digital tools, and thus reflected upon ‘how it is for their users to be in contact through digital tools: the understanding for the devices and what it means to be on such arenas and in the digital world’ (I-3). Some of the groups were concerned that direct client contact would be replaced with digital communication, which challenges the very core of social work: namely, relational work, in which face-to-face communication is of crucial importance.

Teaching digital competence: ICT competency or literacy?

Considerable uncertainty related to the LOC and its meaning thus came to the surface and permeated the different teaching situations participants described, both classroom teaching and skills training at the university and during field placement. Without using the specific terms, the focus group discussions also concerned the distinction between ICT competences and literacy, which revealed various possible interpretations of the LOC; one participant would emphasize teaching students’ ICT competency (e.g. specific digital skills, using specific platforms), while another would highlight teaching an ICT literacy/mind-set (e.g. how digitalization influences discretion). Yet another interpretation was ‘Does teaching digitalization involve knowledge about the consequences of service delivery through digital platforms?’ An additional perspective considered whether teaching digitalization should encompass knowledge about the effects of delivering services through digital platforms. These different perspectives highlight the need for a balanced approach when teaching digital competence, integrating both practical skills and critical understanding, to prepare students for social work in the digital age.

Digitalization in the curriculum

The uncertainty associated with the LOC and how to implement knowledge on digitalization and digital competences in teaching further extended into the discussions about its inclusion in the curriculum and the ‘need to start choosing syllabus texts that deal with digital competences’ (I-3). However, according to some of the informants, the lack of texts about digitalization did not necessarily mirror what actually took place in the classroom:

It is a topic when teaching, however, not part of the syllabus texts. It is related to research methods and the significance of language when designing surveys. (I-2)

I think that it has been thematized, but we have not managed to anchor it in theory and the syllabus and such … . I have the feeling that many people have thematized it. (I-2)

Now it turns out that quite a lot of digital competence is taught to the students without us naming it as such. (I-3)

These quotations all comment on the fact that, while digitalization is thematized to some degree in the classrooms, it is presented as somewhat fragmented or random. The first two quotations see digitalization as lacking in the curriculum but nevertheless taught in the courses in more or less explicit ways, while the final quote supports this but believes it is not articulated as such—i.e. as teaching digitalization. Thus, teaching about digitalization remains underprioritized and unclear. These statements align with the research conducted by Zhu and Andersen (Citation2022) and Taylor-Beswick (Citation2022). Although the programme descriptions do not significantly address specific areas, educators have tried to include the relevant topics in lectures and seminars in the actual teaching of their courses (Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022). However, it also suggests that digital competence is mainly addressed unsystematically and haphazardly. For instance, the teaching of traditional tasks, like case management, is not necessarily incorporated and interpreted as digital competence, even though these tasks are now performed digitally.

Unfamiliar language

In the focus groups, the knowledge—practice gap was not only connected to the LOC itself, but also to terminology that was perceived as technical and unfamiliar: ‘[T]his is another way of communicating; there are other skills we need to practice and be aware of the language’ (I-2). When invited to participate in the focus group sessions, one participant discovered that the LOC had disappeared from the curriculum, despite being implemented in the initial phase: ‘So, when it disappeared from the curriculum, the learning outcome … the technical and the digital, technical security, it is another language, another competence’ (I-1). That they did not discover this earlier indicates that few in the teaching community felt competent in or responsible for including digitalization in the education programme.

Although welfare services are increasingly digitalized, technological concepts, terminology and expressions were experienced by informants as less adaptable and to some degree as incompatible with terminology used in social work. The technical language might thus be positioned outside of their professional language. This could contribute to further widening the gap between the digital development in society and teaching digital competence in social work education. This is not only a language question, as discourses are essential for professional actions (Edwards, Citation2010; Foucault & Neumann, Citation2002; Kleppe, Citation2015; Laclau & Mouffe, Citation2001). Therefore, a demand remains for clarification around and a basic common understanding of what the LOC concerning digital competence in social work education involves—and how to articulate it within the frames of social work.

Social work is no stranger to this type of articulation challenge. Throughout history, social workers have found it challenging to articulate the discipline’s knowledge base (see, for instance, Ambrose-Miller & Ashcroft, Citation2016; Fjeldheim et al., Citation2015; Hoel & Rønnild, Citation2011). Social work has a tradition of reluctance toward implementing technological innovations which extends as far back as the social work pioneer Mary Richmond’s (1861–1928) time. Richmond recommended that social workers exploit the technological innovation of the time, the telephone, to better serve clients. This proposal was met with skepticism and opposition among social workers. Today, technology is still not sufficiently included into social work curricula (Wolf & Goldkind, Citation2016). This indicates that it is a challenging task for social work education to contribute to students’ articulation of their key knowledge, not only in the area of digitization, and that this should be a concern for further research and education.

Rapid digital development: a feeling of running after the train

The development of technology and digitalization in society progresses at such speed that professionals in many fields may feel they are falling behind. Digital knowledge proliferates the welfare services at a speed that makes it difficult for universities and their staff to keep up. This might reinforce the gap between the knowledge taught at universities and the skills needed in society. As one informant articulated, ‘Our problem might be … . how can we keep up, because the speed is so high and so much is happening’ (I-1). Several informants expressed concerns about lacking digital knowledge on a personal level, but also more generally within social work, to stay in step with developments in the welfare services. While the digital train speeds ahead, social work falls further behind and must continue running to catch up. Participants conveyed an urgency, in that the profession needs to ‘get on the train’ to ensure that the newly educated social workers acquire competitive and updated knowledge and skills.

Recent developments are further challenging the qualification processes. An example is that service providers, such as NAV and Barnevernet, are developing digital systems that are then integrated into professional work, challenging traditional working methods. The speed of knowledge development and the diverse number of actors involved challenge the universities’ position as the main provider of knowledge (Nerland & Hermansen, Citation2017). This, in turn, raises the question of who bears responsibility for teaching students the needed digital competences and skills. Who should be responsible for bridging the knowledge gap?

Distribution of responsibility for digitalization knowledge

In the focus group interviews, discussions concerned who is responsible for bridging the knowledge gap related to using digital technology in practice. Is it the field of practice or the educational institutions? A vast majority of the informants agreed that developing digital competency—learning to use different digital platforms—should be the responsibility of the workplace and should be learned in the practice field at work:

I remember we paid close attention to the distinction between what is part of the curriculum and what is part of the employer’s responsibility … . Tools, for instance, the work and welfare administration, have an employer responsibility … we teach them an understanding of what digital competence is, how we communicate in client work and how we make decisions – those are the essentials. (I-3)

The systems that are used in childcare services are tied to the practical work, so it is quite difficult to take the technical parts and teach this separately. Because it is so inextricably connected to the work itself. (I-1)

Although most informants agreed to this distinction between responsibilities, they also believed that the universities’ responsibilities needed to be clarified:

So, while I have insisted that it cannot be our responsibility as a university to teach them programmes like Marte or Familia or whatever they are called, it has to happen ‘out there’. However, they need to know that these tools exist … . And it is also about … we must try to teach them the limitations of the digital platforms. (I-3)

Such an understanding is in line with professional qualification theories, underlining the limitations of formal education. Acquiring all the necessary knowledge and skills during an educational programme is impossible. Some scholars argue that education is primarily about fundamental key knowledge for any member of the professional groups (Collins 1979 in Mausethagen & Smeby, Citation2017). They remind us that newly educated professionals are still novices (Benner, Citation1982), and essential aspects of learning specific and workplace-oriented knowledge must take place at the workplace (Collins 1979 in Mausethagen & Smeby, Citation2017). While the responsibility for teaching digital competency, such as the use of digital programmes and platforms, belonged to workplace, the participants also agreed that a key component in the university’s responsibilities is critical reflection.

Critical reflection

Critical reflection is regarded as crucial to professional and ethical social work practice and essential in social work education. It is also stated as a core competence by the Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge (Citation2019), which stipulates that students should be trained in critical reflection and be able to reflect upon their own profession and professionality. It is unsurprising, then, that critical reflection was elevated in our groups as fundamental knowledge that universities should provide to their students. Almost all the informants emphasized the importance of critical thinking and reflection related to the university’s responsibility:

No, what we teach, that we are very concerned with, is the critical reflection. (I-1)

While the most important job, probably, is to keep the sense of what this is all about, and the critical reflection related to what is it good for and what are the critical dimensions. (I-1)

According to the informants, this held true for digitalization as well; students should be able to reflect critically on digital knowledge and practice in social work in the digital era:

We are expected to teach our students … to reflect critically related to categories, taken for granted ideas, and perhaps we should also remember to include the digital when teaching to reflect critically about how the digital influence our work and thinking. (I-3)

How do I approach this in a way that allows me to analytically see the different dimensions of an issue or a case? This is what they are supposed to be good at, regardless of if it is a human being, software or a case presentation. And that is what I miss the most – even more practice on the systematic approaches to critical reflection. (I-1)

However, none of the groups elaborated on what they meant by ‘critical reflection’ and what it means to reflect critically upon digital competence. It was more or less stated as a taken-for-granted method or skill.

As an element within learning digital literacy, critical reflection is central, representing different traditions of thinking critically about a problem or a situation. Critical reflection requires an introspective analysis of where practitioners position themselves concerning the experiences of the people they will help (Harms & Connolly, Citation2019). Transferred to digitalization, students are expected to learn how to reflect critically when working with clients in a digitalized social work context. Through critical reflection, social workers can better understand the complex issues facing their clients around the digitalization of the social work process and challenge both their own and their clients’ assumptions and biases.

As an extension of the discussions about critical reflection, one of the focus groups talked about the importance of digital judgment as a suitable concept when teaching digitalization:

[S]omething related to having digital judgment or having a digital awareness, that is also a component – a concept one might use, right? That would concern knowing something or adopting an attitude and knowing when to intervene or let the machines do the work. (I-3)

Digital judgment concerns ethics regarding norms, social aspects and laws related to the development and use of digital media (Engen et al., Citation2021). It is not to be considered as new ethics, but an adjustment of existing ethical standards to new situations in digital media (Engen et al., Citation2021; Lee & Chan, Citation2008). Digital judgment in relation to the use of social media was thematized by two of the groups. As one participant emphasized, ‘If you have digital judgment, at least you will have some tools to assess the use of it [social media]’. (I-3)

The ability to critically reflect on both the risks and opportunities of using social media when working with children and young people was discussed. Other topics related to critical judgment included teaching students to reflect upon what is personal and what is professional in social media situations, in addition to privacy settings and digital security—all of which can be understood as developing digital judgment.

Discussion

In this study, and in line with previous research, we have identified an experienced knowledge gap between the digital development in society, the welfare services and social work education (Taylor, Citation2017; Zhu & Andersen, Citation2022). Our informants express a need for more clarity on what constitutes digital competence in social work. This uncertainty extends to how digital competence should be integrated into teaching. In our groups, this gap is expressed in terms of a lack of knowledge—regarding both digital competency and digital literacy—that makes it challenging to keep up with the digital developments in society in general and the social work practice field specifically. This is reinforced by the unfamiliar language used when talking about digitalization. The technical jargon related to digitalization is perceived as alien and incompatible with the professional language of social work, contributing to a widening gap between digital advancements and social work education. The rapid development of digitalization presents a challenge for educators to stay current and relevant in their teaching, leading to a sense of always ‘running after the train’. Furthermore, discussions about narrowing the knowledge gap demonstrate gray areas of shared responsibilities between the practice field and the universities. However, teaching critical reflection is elevated as an essential task for universities in preparing students for practice.

Critical reflection—bridging the gap?

Despite significant uncertainty among the staff about digitalization in social work, it seems that the solution is critical reflection: critical reflection about how digitalization impacts relations to clients, how communication is altered and how people are taken care of within a digital frame. Our findings indicate that critical reflection is understood as a significant skill in social work, in terms of taking a critical standpoint on digitalization. Students should be able to reflect upon how digitalization might be problematic in relational work.

There are several reasons for the popularity of critical reflection in social work. Most importantly, critical reflection mirrors many of social work’s core values. It is a way for social workers to pose critical questions regarding their professionality and understanding of knowledge. Critical reflection is thus meant to give new understanding and insights into one’s practice that contribute to knowledge development and change at an individual and collective level. An overarching aim is contributing to a professional conscious and ethical practice (Kojan & Storhaug in Ellingsen et al., Citation2015); as such, critical reflection is described to conceptualize the relationship between science, intervention and practice in social work (Kojan & Storhaug in Ellingsen et al., Citation2015). Therefore, theoretical knowledge, practice experience, tacit/intuitive knowledge and values are considered equally important and sought to be integrated into critical reflection. In this way, critical reflection might be perceived as a way to bridge the gap between the high-speed development of digitalization in society and the teaching of social work at universities.

There is a danger, however, that critical reflection will become the default answer to ‘everything’. Being a key component in social work education and practice, the concept of critical reflection is often used in a generic way, which makes it difficult to grasp how it relates to specific contexts. Often, critical reflection seems to be the answer, even if it is not clear what the question is. Although critical reflection might be a necessary component within digital literacy, there must be knowledge about the subject matter (digital competency) that forms the basis of such critical reflection (digital literacy). As our research indicates, there is considerable uncertainty associated with teaching digitalization and how digitalization should be understood. As the language is experienced as technical and foreign, it becomes difficult to put into words what digital competence is. To include digitalization in teaching, it is a precondition that the knowledge can be articulated and made relevant in a social work context. In the current context, teaching critical reflection on digitalization as an answer to the ‘knowledge gap’ becomes problematic. There is a danger that both teachers and students will continue falling behind the digital developments.

Concluding remarks

Teaching staff must be equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to allow them to teach their students digital competence and to fully utilize the range of new teaching tools (Lillejord et al., Citation2018). More conceptual clarity is needed regarding the LOC and what digitalization means in an educational context, so that both digital competency and digital literacy gets its natural place in education. Digital competency is a precondition for digital literacy, as the two competences are interdependent: One is not possible without the other.

The discourses of social work and social work theory need to be expanded to include the digital turn in society in general and in social work specifically. Without available language and concepts, many social workers may be unable to both grasp the phenomenon and act according to their understanding. Without concepts that contextualize social work within a digitalized society, social workers might fail to safeguard their clients. An expanded discourse would contribute to clarifying the gray areas of responsibility between education and fields of practice and might lead to better learning outcomes for students during their education.

The sample size is a limitation of this study. Consequently, any conclusions drawn from this research should take this constraint into account. Further research is needed within social work on how to develop social work education within the digital era. Such research should include knowledge about how and where digital knowledge and skills are taught in social work education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aasback, A. W. (2022). Platform social work—A case study of a digital activity plan in the Norwegian welfare and labor administration. Nordic Social Work Research, 12(3), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2022.2045212

- Ambrose-Miller, W., & Ashcroft, R. (2016). Challenges faced by social workers as members of interprofessional collaborative health care teams. Health & Social Work, 41(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw006

- Benner, P. (1982). From novice to expert. The American Journal of Nursing, 82(3), 402–407. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3462928

- Bovens, M., & Zouridis, S. (2002). From street-level to system-level bureaucracies: How information and communication technology is transforming administrative discretion and constitutional control. Public Administration Review, 62(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00168

- Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., Wastell, D., White, S., & Pithouse, A. (2010). Risk, instrumentalism and the humane project in social work: Identifying the “informal” logics of risk management in children’s statutory services. British Journal of Social Work, 40(4), 1046–1064. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq011

- Buffat, A. (2015). Street-level bureaucracy and e-government. Public Management Review, 17(1), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.771699

- Busch, P. A., & Henriksen, H. Z. (2018). Digital discretion: A systematic literature review of ICT and street-level discretion. Information Polity, 23(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-170050

- Busch-Jensen, P., & Kondrup, S. (2015). Velfærdsteknologisk dannelse i arbejdet som lærer og socialrådgiver. In K. K. Eriksen, M. Hansbøl, N. H. Helms, & M. Vestbo (Eds.), Velfærd, teknologi og læring i et professionsperspektiv (pp. 65–86). UCSJ Forlag.

- Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp 2.1: The digital competence framework for citizens: With eight proficiency levels and examples of use (EUR 28558 EN). Publications Office of the European Union.

- Castillo de Mesa, J., & Jacinto, L. G. (2022). Digital competences and skills as key factors between connectedness and tolerance to diversity on social networking sites: Case study of social work graduates on Facebook. Current Sociology, 70(2), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120983341

- Commission International Association of Schools of Social Work and International Federation of Social Workers- Interim Education. (2020). Global standards for social work education and training. https://www.iassw-aiets.org//wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IASSW-Global_Standards_Final.pdf

- Commission of the European Communities. (2006). Global Europe: Competing in the world. A contribution to the EU’s growth and jobs strategy. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2006:0567:FIN:en:PDF

- Cooner, T. S., Beddoe, L., Ferguson, H., & Joy, E. (2020). The use of Facebook in social work practice with children and families: Exploring complexity in an emerging practice. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 38(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1680335

- Edwards, A. (2010). Being an expert professional practitioner: The relational turn in expertise. Springer Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3969-9

- Ellingsen, I. T., Kleppe, L. C., Levin, I., & Berg, B. (Eds.). (2015). Sosialt arbeid: en grunnbok. Universitetsforlaget.

- Engen, B. K., Giæver, T. H., & Mifsud, L. (2021). Om å utøve digital dømmekraft. In B. K. Engen, T. H. Giæver, & L. Mifsud (Eds.), Digital dømmekraft (2nd ed., pp. 17–29). Gyldendal.

- European Commission. (2019a). A Europe fit for the digital age: Empowering people with a new generation of technologies. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age_en

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. (2019b). Key competences for lifelong learning Publications Office. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- Fjeldheim, S., Levin, I., & Engebretsen, E. (2015). The theoretical foundation of social casework. Nordic Social Work Research, 5(sup1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2015.1067900

- Forskrift om felles rammeplan for helse- og sosialfagutdanninger. (2019). (FOR-2019-11-01-1459). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2017-09-06-1353

- Forskrift om nasjonal retningslinje for sosionomutdanning. (2019). (FOR-2005-12-01-1378). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2019-03-15-409

- Foucault, M., & Neumann, I. B. (2002). Forelesninger om regjering og styringskunst. Cappelen Akademisk.

- Fugletveit, R., & Lofthus, A.-M. (2021). From the desk to the cyborg’s faceless interaction in the Norwegian labour and welfare administration. Nordisk välfärdsforskning | Nordic Welfare Research, 6(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2464-4161-2021-02-01

- García-Castilla, J. F., De Juanas Oliva, Á., Vírseda-Sanz, E., & Gallego, J. P. (2018). Educational potential of e-social work: Social work training in Spain. European Journal of Social Work, 22(6), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1476327

- Gillingham, P. (2011). Computer-based information systems and human service organisations: Emerging problems and future possibilities. Australian Social Work, 64(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2010.524705

- Harms, L., & Connolly, M. (2019). Social work: From theory to practice (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Heinsch, M., Cliff, K., Tickner, C., & Betts, D. (2023). Social work virtual: Preparing social work students for a digital future. Social Work Education, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2023.2254796

- Hoel, K. C., & Rønnild, T. C. (2011). Tause selvfølgeliggjøringsprosesser—prosesser innen sosialt arbeids kunnskap. Tidsskriftet Norges barnevern, 88(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-1838-2011-02-03

- Kleppe, L. C. (2015). Making sense of the whole person: A multiple case study exploring the normative expectation of a holistic view of the service users [ PhD thesis]. University of Oslo. http://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-53826

- Kvakic, M., Fineide, M. J., & Hansen, H. A. (2021). Navigering med ustø kurs: Om bruk av digitale og sosiale medier i barnevernet. Tidsskriftet Norges barnevern, 98(3), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-1838-2021-03-02

- Kvakic, M., & Wærdahl, R. (2022). Trust and power in the space between visibility and invisibility: Exploring digital and social media practices in Norwegian child welfare services. European Journal of Social Work, 27(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2022.2099350

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

- Lee, W., & Chan, A. (2008, December 11–12). Computer ethics: An argument for rethinking business ethics [ Paper presentation]. The 2nd World Business Ethics Forum: Rethinking the Value of Business Ethics, Hong Kong Baptist University.

- Lillejord, S., Børte, K., Nesje, K., & Ruud, E. (2018). Learning and teaching with technology in higher education—A systematic review. Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, Knowledge Centre for Education.

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Saga Foundation.

- Mattison, M. (2018). Informed consent agreements: Standards of care for digital social work practices. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1404529

- Mausethagen, S., & Smeby, J.-C. (Eds.). (2017). Kvalifisering til profesjonell yrkesutøvelse. Universitetsforlaget.

- Meld. St. 27. (2015–2016). Digital agenda for Norge—IKT for en enklere hverdag og økt produktivitet. Ministry of Local Government and Districts. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-27-20152016/id2483795/

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation. (2019). One digital public sector—Digital strategy for the public sector, 2019–2025. One digital public sector - regjeringen.no.

- Mishna, F., Bogo, M., Root, J., Sawyer, J.-L., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2012). “It just crept in”: The digital age and implications for social work practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 40(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-012-0383-4

- Nerland, M., & Hermansen, H. (2017). Sosiomaterielle perspektiver på profesjonskvalifisering: kunnskapsressursenes betydning. In S. Mausethagen & J.-C. Smeby (Eds.), Kvalifisering til profesjonell yrkesutøvelse (pp. 167–179). Universitetsforlaget.

- Peckover, S., White, S., & Hall, C. (2008). Making and managing electronic children: E-assessment in child welfare. Information, Communication & Society, 11(3), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180802025574

- Peláez, A. L., Erro-Garcés, A., & Gómez-Ciriano, E. J. (2020). Young people, social workers and social work education: The role of digital skills. Social Work Education, 39(6), 825–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1795110

- Pithouse, A., Hall, C., Peckover, S., & White, S. (2009). A tale of two CAFs: The impact of the electronic common assessment framework. British Journal of Social Work, 39(4), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp020

- Reamer, F. G. (2018). Ethical standards for social workers’ use of technology: Emerging consensus. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 15(2), 71.

- Svensson, L., & Larsson, S. (2018). Digitalisering av kommunal socialtjänst. En empirisk studie av en organisation och profession i förändring. FoU Helsingborg.

- Taylor, A. (2017). Social work and digitalisation: Bridging the knowledge gaps. Social Work Education, 36(8), 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1361924

- Taylor-Beswick, A. (2022). Digitalizing social work education: Preparing students to engage with twenty-first century practice need. Social Work Education, 42(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2049225

- Tjora, A. (2021). Kvalitativ forskning i praksis. Gyldendal.

- Wolf, L., & Goldkind, L. (2016). Digital native meet friendly visitor: A flexner-inspired call to digital action. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(sup1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1174643

- Zemaitaityte, I., Bardauskiene, R., Pivoriene, J., & Katkonienė, A. (2023). Digital competencies of future social workers: The art of education in uncertain times. Social Work Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2164269

- Zhu, H., & Andersen, T. A. (2022). Digital competence in social work practice and education: Experiences from Norway. Nordic Social Work Research, 12(5), 823–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2021.1899967