ABSTRACT

A teacher supervising the school practice of student teachers is regarded as an expert who sets an example of good teaching to future teachers and chooses teaching practices that support pupils’ cognitive and social development. This study examines the implementation of teaching practices and the interpretation of these practices by school-based teacher educators who supervise school practice of student teachers at universities’ innovation schools. Teaching practices were examined using observation and video-stimulated recall interviews. The school-based teacher educators widely used and described in detail individual teaching practices that supported pupils’ cognitive development. However, observations indicated a more limited use of collaborative teaching practices that promote pupils’ social and cognitive development. Setting a good example of teaching gives school-based teacher educators the opportunity to develop both student teachers’ and their own teaching competence.

Introduction

In several countries, including Estonia, schools’ responsibilities with respect to preparing student teachers for their future work have increased over the last decade (Pedaste et al. Citation2014; Sandvik et al. Citation2019). Teachers who supervise student teachers’ school practice, i.e. school-based teacher educators (SBTEs), are expected to set an example of how to teach pupils and use appropriate teaching practices (Cohen, Hoz, and Kaplan Citation2013). They are also expected to be capable of choosing practices that achieve several goals and to connect student teachers’ theoretical concepts with practical training (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen Citation2014). However, not all teachers are sufficiently prepared to supervise (Butler and Cuenca Citation2012; Jaspers et al. Citation2014; White, Dickerson, and Weston Citation2015), and many do not appreciate the importance of their role in training future teachers (Mason Citation2013). During the instructional process, SBTEs may focus mainly on supporting pupils, neglecting the development of student teachers (Jaspers et al. Citation2014).

To cultivate teaching competencies in student teachers, SBTEs themselves should have full command over the purposeful use of various teaching practices. Teaching practices can be defined as sets of instructional methods and strategies employed in teacher–pupil interaction in the classroom (Khader Citation2012). These practices should seek to enhance the various cognitive and social skills of pupils (Ferguson Citation2002; James and Pollard Citation2011; Kuzborska Citation2011). Some studies show that, in supporting pupils’ cognitive development, teachers prefer to use teaching practices focused on memorising and applying previously learned knowledge, leaving the development of pupils’ social skills in the background (Brackett et al. Citation2012; Uibu and Kikas Citation2014). Teachers may also be too oriented to preparing pupils to succeed in academic tests (Fraser Citation2010), even though national teaching standards and curriculum suppose more versatile promotion of pupils’ cognitive competencies, e.g. analytical, critical and creative thinking (Bietenbeck Citation2014; Estonian Government Citation2011/2014).

However, social skills are considered a main factor in resolving problems and coping within the society (Buchanan et al. Citation2009; Huitt and Dawson Citation2011). To support pupils’ social development, teachers should apply teaching practices that encourage cooperation and develop communication skills (Gillies and Boyle Citation2010; Muijs and Reynolds Citation2010). Following the contemporary concept of learning, teachers’ choices of teaching practices (e.g. inter-pupil discussions, real-life applications) should form a system that supports pupils’ cognitive and social development (Jennings and DiPrete Citation2010).

Previous studies show that the practices teachers apply in their lessons may differ from those they claim to use (Fraser Citation2010; Teague et al. Citation2012). However, little is known internationally about the teaching practices used by SBTEs, who perform two roles: first, teaching pupils, and second, supervising and setting an example of good teaching for student teachers during their school practice (Ambrosetti Citation2014; Sandvik et al. Citation2019). The aim of this study is to determine which teaching practices SBTEs apply in their instruction and how they explain the use of these practices in relation to their teaching goals and their supervision of student teachers.

Teaching practices for supporting pupils’ development

Teaching practices are considered essential to a teacher’s work regimen, as they are used to develop pupils’ knowledge and skills (Den Brok et al. Citation2004). Teachers’ choice of teaching practices in the classroom is associated with the goals they set (Brophy Citation2001; Vaughn Citation2014) and can change according to pupils’ development (Den Brok et al. Citation2004; Uibu and Kikas Citation2014). Thus, teachers should apply a variety of individual and collaborative teaching practices to promote pupils’ cognitive and social skills (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007). According to the National Curriculum for Basic School (Estonian Government Citation2011/2014), teachers in Estonia are expected to apply practices that will enhance pupils’ age-appropriate cognitive and social development and model real-world situations from the surrounding environment.

Cognitive development has been defined as the construction of thinking processes from childhood through adolescence to adulthood (Richland, Frausel, and Begolli Citation2016). Supporting pupils’ cognitive development does not mean that teachers focus on the rote memorisation of isolated facts. Nevertheless, research conducted in Estonia showed that to transmit knowledge, teachers rely on teaching practices that allow individual or routine activities and encourage mechanical learning through the completion of worksheets and the learning and repetition of facts (Uibu and Kikas Citation2014). Over time, pupils become more capable of generating inferences that connect units larger than individual events and facts (Cain Citation2010; Currie and Cain Citation2015). They are more able to connect not only concrete associations but also abstract ones (Van Den Broek, Rapp, and Kendeou Citation2005). Teachers must choose individual teaching practices that correspond to pupils’ cognitive development stage, promoting information recall and coding, as well as processing and decision-making skills (Opdenakker and Van Damme Citation2006). It is also necessary to give pupils practical tasks, teach them how to use knowledge in everyday life, and develop problem-solving and decision-making skills (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007; Richland, Frausel, and Begolli Citation2016).

Discussions with peers through collaborative teaching (Gillies and Boyle Citation2010) allow pupils to explain what they have learnt in their own words and to compare different opinions and solutions (Good, Wiley, and Florez Citation2009). When pupils become more competent, teachers can use more complicated tasks to support their critical thinking and reasoning (James and Pollard Citation2011). Older pupils have been found to apply their pre- and background knowledge more widely and are able to generalise at higher cognitive levels (De Groot-reuvekamp, Ros, and Van Boxtel Citation2019). For this reason, teachers must use more collaborative teaching practices to engage students in dialogues, teaching them to argue, express their opinions and ask questions (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007).

In addition to cognitive competencies, teachers should enhance pupils’ social development (Buchanan et al. Citation2009). Pupils are expected to learn appropriate behaviour, knowledge about their own and others’ emotions, effective communication, stable relationships, cooperation with others and the capacity to resolve conflicts (Huitt and Dawson Citation2011). Here, teaching practices that encourage collaboration should be applied. For example, work in pairs and groups has been found to help pupils assess their knowledge, develop communication skills, consider peers’ opinions, and take responsibility for their own actions (Gillies and Boyle Citation2010; Muijs and Reynolds Citation2010). Some activities, such as role-playing and board games, are also suitable for social skill development because they teach children to cope in everyday situations (Haney and Bissonnette Citation2011).

In general, a diverse combination of individual and collaborative classroom teaching practices yields a more favourable context for developing a wide range of competencies in children (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007). However, teachers do not always use teaching practices that help achieve teaching goals because they lack sufficient knowledge about the compatibility of their teaching goals with available teaching practices (Forslund-Frykedal and Chiriac Citation2014).

Teaching practices for providing examples for student teachers

Prior to conducting their own classes, student teachers observe and analyse SBTEs’ lessons in real teaching situations (Cohen, Hoz, and Kaplan Citation2013). SBTEs provide examples of good teaching that student teachers can follow in their future work. It is particularly important that SBTEs select teaching practices and associated instructional goals (see Uibu et al. Citation2017) that are in the best interest of their pupils. Student teachers rely on previous experiences, examples, and recommendations from their supervisors (Sayeski and Paulsen Citation2012). However, when planning their lessons and teaching pupils, SBTEs are not always aware that they are also setting an example of teaching and, thereby, influencing how student teachers will teach in the future (Nilsson and Van Driel Citation2010).

There are several reasons SBTEs fail to comprehend the full scope of their influence. Firstly, not all SBTEs have received sufficient training to supervise student teachers’ school practice (Ambrosetti Citation2014; Salo et al. Citation2019), and some lack the time needed to supervise (Mason Citation2013). Secondly, teachers prioritise their pupils’ academic progress over supporting student teachers in the instructional process (Jaspers et al. Citation2014). Thirdly, it is difficult for SBTEs to perform these two tasks simultaneously (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen Citation2014; Cohen, Hoz, and Kaplan Citation2013).

SBTEs demonstrate various aspects and good examples of instruction in observation lessons (e.g. how to use different teaching methods and techniques, how to create an effective learning environment). The observation is a part of teacher training and comprises three stages (TU Pedagogicum Citation2019). Before observation student teachers acquire the main principles of teaching theory and/or subject didactics (Nilsson and Van Driel Citation2010). During the lesson, they observe instruction, conducted by SBTEs, and take notes. After observation, the instruction is analysed in groups or individually in oral or written form. However, studies have shown that, in observation lessons, SBTEs try to show students as diverse a selection of teaching practices as possible (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen Citation2014; Salo et al. Citation2019). While variation in teaching practices is useful, it is also important to choose the practices that rely on the theoretical foundation of children’s development (Jaspers et al. Citation2014). Student teachers presume that, even in observation lessons, SBTEs use practices in which the acquisition and association of knowledge is paramount (Sayeski and Paulsen Citation2012). Since pupils’ academic success is evaluated above all else, SBTEs may be more inclined to enhance pupils’ cognitive rather than social development (Uibu and Kikas Citation2014).

The practices used in lessons should be thoroughly pre-planned (Butler and Cuenca Citation2012; Sayeski and Paulsen Citation2012) and structured to create a learning-oriented environment (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen Citation2014). SBTEs are expected to analyse observation lessons with student teachers and explain what was done and why. SBTEs are usually aware of which teaching practice is required for each lesson and to what extent, but they are not always focused on able to explaining the scope of their choices (Salo et al. Citation2019). However, student teachers might not be able to identify these choices based solely on what they see. Awareness of lesson preparation and the analysis of teaching practices following a lesson are necessary to both the student teacher and the SBTE (Nilsson and Van Driel Citation2010; Van Velzen and Volman Citation2009), enabling them to assess their knowledge of teaching and increase their confidence (Anspal, Leijen, and Löfström, Citation2019).

The present study

The role of SBTEs in teacher training in Estonia

Depending on the type of educational institution there are different qualification conditions for becoming a teacher in Estonia. For example, kindergarten and vocational school teachers are educated at bachelor’s level for three years, primary school teachers and subject teachers can be educated at the master’s level for five years. However, regardless of the structure of the teacher education curriculum, teacher training includes different types of teaching practice at both university and school levels (TU Pedagogicum Citation2019). In the first stage, the student teachers conduct mini-lessons with fellow students under the guidance of subject didactics teachers in university instructing sessions. In the second stage student teachers observe lessons of SBTEs and conduct trial lessons at innovation schools (Anspal et al., Citation2019; TU Pedagogicum Citation2019). In the third stage, student teachers teach full-time lessons under the guidance of SBTEs and university supervisors. In the fourth and final stage student teachers’ professional development is supported by offering them the opportunities to combine theory studied in university and practice experienced in schools (TU Pedagogicum Citation2019). In the primary school teacher curriculum school practice is carried out over the whole period of teacher training, during which student teachers perform different types of teaching practice at innovation schools (Anspal, Leijen, and Löfström Citation2019). In this process, STBEs become intermediaries between schools and universities (Lunenberg Citation2010), ready to supervise student teachers and prepare them for their future work by setting a good example of how to teach pupils (Anspal, Leijen, and Löfström Citation2019).

In 2013, a network of innovation schools was established in Estonia to involve SBTEs more directly in the development of teacher education (Pedaste et al. Citation2014). The universities expect SBTEs to conduct observation lessons at the beginning of teacher training. In the third and fourth stage of teacher training, SBTEs are expected to help student teachers plan teaching practices and select those most relevant to their teaching goals, in addition to providing feedback on their teaching (TU Pedagogicum Citation2019). Thus, SBTEs assume different responsibilities in the supervision process: they observe the activities of student teachers without direct intervention, they supervise student teachers during the teaching process, and they make student teachers aware of their own actions (Salo et al. Citation2019; see also Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen Citation2014). To ensure success across all these activities, SBTEs must establish a good rapport with their pupils and consider their development needs in their specific learning–teaching context.

Aims and research questions

This study provides insight into the implementation of teaching practices by teachers who teach pupils while simultaneously supervising the school practice of student teachers (i.e. SBTEs). The aim was to detect which teaching practices SBTEs use in their instruction and how they explain the use of these practices in relation to teaching goals and the supervision of student teachers. Building on earlier studies (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007; Salo et al. Citation2019; Uibu et al. Citation2017), three research questions were established:

Which different teaching practices are implemented by SBTEs to support pupils’ cognitive and social development?

How do SBTEs explain and clarify their use of different teaching practices?

What do SBTEs expect student teachers to learn from their teaching, when SBTEs perform their supervisor’s role?

Method

Participants

The study was conducted as a part of research focused on the assessment of SBTEs’ teaching and supervising competence. The purposefully composed sample included 11 teachers (10 women and 1 man) from previous studies. The choice of teachers was based on three criteria. First, all teachers had attended courses at universities focused on supervising student teachers’ school practice. Second, all teachers had supervision experience with student teachers (M = 17, min = 1 year, max = 36 years). Third, teachers taught various subjects (e.g. Estonian language, science, maths) in grades 1 to 6 (pupils aged 7 to 13) at universities’ innovation schools. Their average age was 53 years (min = 43, max = 63), and their average teaching experience was 24 years (min = 21, max = 40). All teachers participated voluntarily in the study two years after completion of the courses for supervisors at universities. They were fully informed about the nature of the research and about the right to withdraw from the study for any or no reason and at any time. For the purpose of their confidentiality, specific codes (e.g. T4, T11) are used to identify them when presenting the excerpts from the stimulated recall interviews.

Data collection

Data were collected by observation and stimulated recall interviews (SRIs) to determine the kinds of teaching practices SBTEs were implementing and the reasons these teaching practices were appropriate. Participant explained their teaching practices to help researcher to understand and interpret their actions (Vesterinen, Toom, and Patrikainen Citation2010). SBTEs were informed about the purpose of the study and were assured that their opinions would be anonymous (Lyle Citation2003). The data collection process consisted of three stages.

Stage 1: observational records

Suitable times were arranged for video recordings and interviews and parents’ permission was secured to record lessons. First, the SBTE and the Author 2 explained the procedure to pupils. Then, teachers were recorded in two successive lessons that the student teachers did not attend. Over 22 lessons taught by SBTEs were recorded, altogether duration of 16.5 hours. In compiling the observation checklist, the Authors 1 and 2 relied on observation sheets used in previous studies (Danielson Citation2013; Walpole et al. Citation2010). Authors piloted observation checklist with two teachers not involved in this sample. The checklist contained descriptions of 18 individual and collaborative teaching practices: 12 aimed at pupils’ cognitive development and 6 aimed at their social development (see also Uibu et al. Citation2017). All the practices teachers used during the introduction, body and end of lessons were noted in the checklist. The observation criteria included individual and collaborative practice according to pupils’ cognitive and social development (see Appendix A). The checklist was fulfilled by Authors 1 and 2. The background information on the SBTEs (e.g. age and teaching and supervising experience) and the lessons (e.g. subject, class, number of students) were also collected.

Stage 2: selection of recorded situations for SRIs

To conduct interviews with the SBTEs, the Author 2 chose two episodes (varying from 5 to 20 minutes each) from each teacher’s lessons. They were chosen so that one contained teaching practices supporting pupils’ cognitive development and the other included examples of social development. Both situations were selected to be comprehensive and to help the SBTE relive what happened in the lesson (Lyle Citation2003).

Stage 3: SRIs

The SRIs were based on the teachers’ video-recorded lessons and focused on stimulating class situations. The delay between recording and real action was minimised to improve the accuracy of teachers’ explanations of their experiences (Lyle Citation2003; Vesterinen, Toom, and Patrikainen Citation2010). Whilst watching the videos with Author 2, the teachers explained the classroom circumstances and expressed their thoughts concerning their teaching practices. The SRIs included 12 questions covering topics related to the recorded situations and the teachers’ goals in supervising student teachers. Teachers were encouraged to explain their teaching practices (e.g. Please explain why you decided to use this practice?) and to analyse them in relation to supervising student teachers (How could this practice be useful to him/her?). When a teacher was ready to make a comment, the Author 2 stopped the video and began to ask the interviewee questions about the situation. Altogether, nearly 8 hours of interview recordings were collected from 11 SBTEs, varying from 29 minutes and 35 seconds to 74 minutes and 12 seconds. On average, two situations of SRIs took 43 minutes.

Data analysis

To achieve a comprehensive overview, both quantitative and qualitative research methods were applied. The data table was compiled based on observation records. The frequency of use of various teaching practices by each teacher was determined between all authors using the following scoring guidelines: 2 – used several times, 1 – used only once, and 0 – not used at all (see Appendix A). Double-coding was used to ensure study credibility (Adler and Adler Citation1987). Inter-coder reliability coefficient Cohen’s kappa was calculated for teaching practices of supporting students’ cognitive and social development (k ranged from 0.74 to 1.00). Then, the Authors 1 and 2 drew up a data table grouping the frequencies according to whether the teaching practices supported pupils’ cognitive and/or social development and whether they were individual or collaborative. The frequencies of occurred teaching practices were within each of the participants in two groups – practices for supporting students’ cognitive development (max = 10; min = 7) and social development (max = 7; min = 3). Next, observed practices of all the teachers were added up. Summarising the results of the observed teaching practices enabled the authors to conclude which practices the SBTEs, as a group, applied more often (max = 17) and which less often (min = 2).

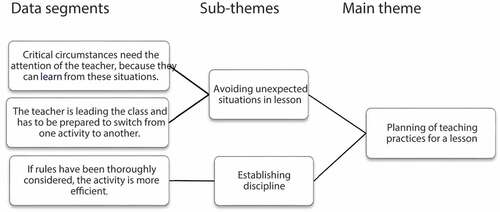

The data collected through the SRIs were analysed by the second and third research questions. Using an inductive approach, the systematic coding process was elaborated, and sub-themes and themes were identified, reviewed and refined (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Afterwards, a data table was drafted with the codes grouped into sub-themes under the main themes and structured in relation to the research questions (see ).

To ensure credible results, triangulation of authors was used (Patton Citation2002). The interview transcripts were independently coded by Authors 1 and 2, who obtained similar results (Bazeley Citation2013). Re-coding, in which the Author 2 re-coded the interviews after one month, was also used to increase the reliability of the study. The results of the re-coding matched the first coding; however, some changes were made in the names of sub-themes.

Results

The results are presented in three sections proceeding from the research questions. The first section describes which different teaching practices were implemented by teachers to support pupils’ cognitive and social development. The second section details how SBTEs explained and clarified their use of teaching practices in different parts of lessons. The third section describes what SBTEs expect student teachers to learn from their teaching, when SBTEs perform their supervisor’s role. In the second and third sections, the results of the thematic analysis are reported according to the main themes, and they include excerpts of the class situations and the SBTEs’ explanations.

Application of teaching practices

In the observed lessons, SBTEs implemented several teaching practices to support pupils’ individual and collaborative learning. Individual teaching practices were used to promote pupils’ cognitive and social development, though the amount of practice devoted to each of these purposes differed (see ).

The frequency of occurrences (f) of teaching practices demonstrates that SBTEs used individual teaching practices more intensively to support pupils’ cognitive development (e.g. for application of knowledge, development of analysis, and enhancement of topic comprehension). In contrast, independent work and practices developing pupils’ memorisation were observed less frequently (respectively, f = 4 and f = 2). Furthermore, some individual teaching practices were aimed at enhancing pupils’ social development, with a particular focus on encouraging them to listen to one another (f = 19). Practices aiming to enhance pupils’ self-expression and appropriate behaviour patterns were observed to a lesser extent.

Compared to individual teaching practices, the variety of collaborative practices for promoting pupils’ cognitive and social development was more restricted. The frequencies of occurrences of collaborative teaching practices are presented in .

Based on observations, the teachers initiated discussions more than other practices in order to enhance pupils’ cognitive development. To promote the pupils’ social development, they implemented several types of group work and encouraged pupils to express their opinions and ask for assistance from their classmates in solving tasks.

SBTEs’ explanations about their teaching practices

The investigation of how SBTEs explained and clarified their application of teaching practices in different parts of lessons identified two main themes: supporting pupils’ individual learning and enhancing pupils’ collaborative learning.

Teaching practices supporting pupils’ individual learning

SBTEs emphasised the importance of promoting pupils’ cognitive development and stressed that teaching practices offer opportunities to use previous knowledge. When pupils perform tasks independently, they associate them with background knowledge and experiences that make it easier to comprehend new information. Teachers considered individual teaching practices essential to the knowledge acquisition process and to training pupils’ memorisation skills. The following excerpt illustrates that reading texts independently and answering teachers’ questions were considered the effective ways to acquire new information and to promote children’s understanding of their own knowledge.

Generally, SBTEs indicated that the use of teaching practices supporting pupils’ cognitive development was justified, as it considered each pupil’s individuality.

SBTEs’ opinions about individual practices promoting pupils’ social performance skills were more restrained. They considered it is important to ask different types of questions, e.g. factual question (What does this word mean?) or inferential and evaluative questions (What thoughts did this story arouse in you?). Teachers said that asking open questions meant monitoring pupils’ self-expression skills. Questioning of pupils increased their ability to focus on a topic, as pupils had to constantly keep track of what the teacher wanted to know and be prepared to formulate their answers. In the next excerpt, by asking questions, the teacher observed how well pupils were listening. According to the teacher, it contributes to the acquisition of knowledge.

In some cases, when developing pupils’ self-expression skills, teachers paid more attention to the breadth of pupils’ vocabulary than to their comprehension and answer correctness. For example, if a task required a pupil to use the text to tell about a lion, the teacher also allowed speaking about other animals.

Teaching practices enhancing collaborative learning among pupils

Collaborative teaching practices, such as pair or group work, were mainly associated with promoting pupils’ communication skills. SBTEs highly valued working in pairs because this enhances pupils’ skill in establishing contacts. They also self-critically acknowledged the need to encourage pupils to listen to one another and pay more attention to pupils’ interaction skills. The following excerpt demonstrates the SBTE’s concern about students who do not collaborate with others.

With respect to collaborative practices, teaching pupils how to cope in different situations was important to SBTEs, but they enabled the pupils to decide how to work within teams. SBTEs attempted to help pupils practice taking more active roles, assuming that this would enhance pupils’ acceptance of different people’s opinions.

When tasks became more difficult, they were analysed together in the classroom. According to SBTEs, cooperation between a teacher and pupils is an efficient way of enhancing thinking skills, as the teacher can offer appropriate examples of how to fulfil tasks. SBTEs concluded that collaborative practices need to be adapted to help the less able pupils improve their communication skills.

Teaching practices as an example to student teachers

The analysis of what SBTEs expect student teachers to learn from their teaching, when SBTEs perform their supervisor’s role, revealed two main themes: First, planning teaching practices for lessons, and second, setting examples of good teaching practices.

Planning of teaching practices

SBTEs present observation lessons for student teachers, when they supervise school practice. Some SBTEs mentioned the importance of student teachers taking notes during these lessons and analysing them together to explain the reasons for success and failure. The SBTEs usually advised student teachers to use the teaching practices they implemented in their own classrooms. Through analysing the observation lessons, student teachers learned how to prevent problems, establish discipline and make better choices to enhance pupils’ development. This type of analysis could help student teachers plan their own lessons. Nevertheless, as shown in the next excerpt, SBTEs acknowledged that the teaching process had not always proceeded as planned.

Thus, unexpected situations arising from SBTEs’ lessons might also cause problems for student teachers if trial lessons are not analysed. To ensure that student teachers implement teaching practices correctly, SBTEs encourage them to use these practices in student teachers’ trial lessons.

SBTEs confirmed that lesson planning might be very time-consuming for student teachers for several reasons. Firstly, if the aim is to support the development of all pupils, student teachers cannot rely solely on existing study materials, such as textbooks and worksheets. Secondly, student teachers should be able to assess what knowledge and skills the planned teaching practices require of them. When student teachers do not have enough teaching experience, problems may occur in lessons. Therefore, it is important for student teachers to plan teaching practices that are easy to implement (e.g. reading and writing tasks). SBTEs assumed that collaborative activities might sometimes cause difficulties for student teachers (e.g. due to pupils’ disruptive behaviour), but that such activities are essential for engaging all pupils.

Setting an example of good teaching practices

SBTEs recognised that student teachers should focus on supporting pupils’ cognitive development with the aim of promoting knowledge acquisition. Student teachers could practise asking children to present their views on different issues and justify their reasons. The SBTEs considered whole-class and group discussions, in which pupils analyse and add details to their peers’ answers, in addition to rephrasing and justifying their own, to be useful in checking what pupils have learned.

Working in pairs was deemed appropriate for developing pupils’ social skills, as SBTEs reported that peers’ explanations could be more understandable than those given by a teacher. The next excerpt offers an insight on how pair work is a straightforward way of engaging all pupils in the learning process and enhancing their self-expression skills.

The SBTEs also emphasised the importance of establishing and explaining rules for student teachers to facilitate the application of different practices. SBTEs expect student teachers to realise that rules can help create the school culture and develop pupils’ ability to consider other people. According to SBTEs, it is essential to demonstrate to student teachers how classroom rules are consistently followed and justified. The following example sheds light on SBTS’s intention and explanations.

In conclusion, SBTEs claimed applying the same practices they had used in the observed lessons would benefit the student teachers’ theoretical preparation. In setting an example, SBTEs want to show student teachers that they should plan the purpose and method of using a specific teaching practice.

Discussion

SBTEs are expected to teach pupils as well as establish examples for student teachers by applying teaching practices that support pupils’ comprehensive development. When the interviewed SBTEs described their teaching practices, they prioritised individual teaching practices that support the pupils’ cognitive development, although observations of the lessons showed that teachers used a more diverse range of teaching practices. The SBTEs expected student teachers to use individual teaching practices in trial lessons. They sought to support student teachers by planning and applying relevant teaching practices.

Observed and interpreted teaching practices of SBTEs

The observation of the individual and collaborative practices the SBTEs used to support pupils’ cognitive and social development yielded several insights. The SBTEs largely focused on developing the pupils’ application and analytical skills, foregoing individual practices aimed at memorising facts and definitions and performing individual tasks. On the one hand, teachers generally apply age-appropriate practices in their teaching. On the other hand, if teachers confront difficulties in integrating teaching practises, they might focus on a specific measurable aspect of the pupils’ development (Vaughn Citation2014). This could be the reason why teachers use single activities that are easily applied (Muijs and Reynolds Citation2010).

Previous studies have shown that teachers implement to lesser extent teaching practices aimed at enhancing pupils’ social development (Brackett et al. Citation2012; Uibu and Kikas Citation2014). The present study revealed that teachers used individual teaching practices that enhance also pupils’ social development, paying special attention to their listening skills. According to teachers, the development of listening skills contributes to the maintenance of discipline in the classroom and supports the development of pupils’ cooperation skills (Salo et al. Citation2019). The enhancement of pupils’ listening skills also supports the development of analytical skills and helps to participate more effectively in discussions (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007). The less frequent use of practices that support pupils’ collaboration could be also explained by the nature of the observed lessons (Jaspers et al. Citation2014).

Although SBTEs used both individual and collaborative teaching practices, they did not sometimes pay equal attention to the promotion of pupils’ comprehensive development. Based on observations, the use of teaching practices for promoting pupils’ cognitive development was more versatile than in case of social development. According to Jennings and DiPrete (Citation2010), teachers consider varying teaching practices during lessons to be important for actively involving pupils in the instructional process, since using a variety of teaching practices better considers pupils’ individual needs (Fraser Citation2010). The diversity of teaching practices observed in this study may have also stemmed from the SBTEs’ desire to provide richer substance for the analysis of their activities (White, Dickerson, and Weston Citation2015).

The second research question examined how SBTEs explain and clarify their choice of different teaching practices in lessons. It appeared that, with respect to the teaching practices enhancing pupils’ cognitive development, teachers were aimed at training memory and association of knowledge, which are necessary for the acquisition of basic knowledge and to achieve success in school (James and Pollard Citation2011). Although the teachers emphasised the importance of memorisation skills, they felt that teaching practices that support cognitive development enable pupils to perform tasks by applying previously acquired knowledge and experience (cf. De Groot-reuvekamp, Ros, and Van Boxtel Citation2019). Creating connections with everyday life and personal experiences has been found to support pupils’ comprehension (Good, Wiley, and Florez Citation2009) and individual development (Perry, Donohue, and Weinstein Citation2007).

SBTEs’ explanations of teaching practices enhancing pupils’ social development in this study were somewhat restricted. One reason could be the fact that national teaching standards and curriculum emphasise more the development of pupils’ cognitive skills (see Bietenbeck Citation2014; Estonian Government Citation2011/2014). Although teachers have a basic theoretical knowledge of teaching, their ability to purposefully plan and implement teaching practices tend to be restrained (Fraser Citation2010). They may doubt whether they have enough knowledge about how to improve pupils’ development at different cognitive levels (Teague et al. Citation2012). Teachers may become aware of new fruitful teaching methods, however, they may be slow to adopt different teaching practices.

Regarding pupils’ cognitive and social development, SBTEs highlighted a number of interaction-based collaborative activities (e.g. work in pairs, analysis with the whole class). They considered it important for pupils to learn to listen, to find different solutions through analysis, and to learn to make acceptance of classmates’ opinions. Collaborative practices ensure a student-supportive learning environment (Muijs and Reynolds Citation2010). A comparison of the individual teaching practices and teaching activities requiring cooperation revealed that the SBTEs did not emphasise collaborative practices as highly as individual practices. Teachers noted that pupils have problems with self-expression and that some have difficulties communicating with peers. Group work could be complex, as the pupils in the lower age groups (7 to 13 years) are still developing their social skills (see also Jaspers et al. Citation2014).

In conclusion, the spectrum of teaching practices observed was much broader and more diverse than the SBTEs’ explanations of their practices in the interviews. Teachers were willing to use teaching practices that supported pupils’ social development, but hardly mentioned these practices in their descriptions about what they had seen on the videos. The observations and the SBTEs’ explanations show that they focused more on pupils’ cognitive development and favoured more teaching practices that allowed pupils to apply and analyse their knowledge. The SBTEs emphasised knowledge implementation and self-expression more in the interviews than when these practices were observed in videos. Thus, the study revealed a disparity between what teachers did and what they discussed and communicated in their explanations (see also Fraser Citation2010; Teague et al. Citation2012).

Setting an example of teaching to student teachers

Next, the findings showed what the SBTEs expect student teachers to learn from their teaching, when SBTEs perform their supervisor’s role. According to the SBTEs, the planning of teaching practices and the setting of examples of teaching in the classroom are equally important. It is vital to consider what teaching practices are and how they are used. Since student teachers do not have prior teaching experience, planning teaching practices support their performance in the classroom (Sayeski and Paulsen Citation2012). The SBTEs also expected student teachers to analyse, based on notes taken in SBTEs’ observation lessons, targets for the use of teaching practices. The SBTEs’ explanations showed that they tended to use teaching practices that enhanced pupils’ cognitive development, which they believed makes independent teaching easier for student teachers (see also Sayeski and Paulsen Citation2012). The SBTEs may have wanted to ensure that the student teachers’ first teaching experiences were positive. In other words, SBTEs may have tried to direct student teachers to use ‘safer’ teaching practices to prevent the types of problems that could arise with collaborative teaching practices (Gillies and Boyle Citation2010).

This study revealed that, although SBTEs sought to give student teachers examples of which teaching practices to use and how, they might have done it in a somewhat restrained way. The reason may be that, while supervising student teachers, SBTEs focus more on the development of the pupils and are unclear about what they should be teaching to student teachers (Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen Citation2014; Sandvik et al. Citation2019). SBTEs help student teachers select the most relevant teaching practices, cope with different tasks and develop confidence in teaching (Anspal, Leijen, and Löfström Citation2019; TU Pedagogicum Citation2019). They should also be capable of explaining their theoretical principles and how to integrate theory into practice (Sandvik et al. Citation2019). In this way, the teaching practices demonstrated by SBTEs can be fruitful for student teachers when they start independent teaching.

Limitations and conclusions

This study had some limitations related to the methodology. Firstly, every teacher’s teaching practices were observed and video-recorded in two successive lessons. More observations would have provided a more consistent overview. Further, the one author selected from the video recordings the situations that coincided with the aims of the study. To support the professional development of SBTEs, the SBTEs themselves should be offered the opportunity to choose which lessons should be analysed. Secondly, the study sample was homogeneous, involving teachers from universities’ innovation schools who had significant experience supervising students. It is possible that the involvement of teachers with little or no supervision experience would have provided more diverse results. Furthermore, the study did not include the student teachers. Stimulated recall interviews with the student and novice teachers based on observation records would have provided more insight into how they comprehended the use of teaching practices. Thirdly, all participants had graduated SBTE preparation courses, which focus on supervising student teachers’ school practice. The SBTEs knew that they were being observed by the author who had interviewed them in the previous stages of the study. Therefore, they could implement practices encouraged by the programme for supervisors.

Despite these limitations, SBTEs were studied in their natural working conditions by observing and analysing their activities, and they had the opportunity to explain the use of their teaching practices, both of which are strengths of the study. The triangulation of data collection methods, in which observations were combined with stimulated recall interviews, produced more credible results regarding teaching practices than would have been possible using a single research method. Further, the SBTEs’ practices were analysed from two perspectives: as teachers of pupils and as supervisors of student teachers. As there was disparity between what the SBTEs did and how they interpreted what they did, the systemic analysis of SBTEs practices by university supervisors should be part of SBTEs’ preparation. Moreover, it is important to discuss with future and acting SBTEs when and how to demonstrate different teaching practices and how to reflect on observed lessons with student teachers, as well as how to plan student teachers’ own lessons both under the guidance of SBTEs and individually. The results of the study could be useful to researchers in the teacher education field as well as to developers of educational policy, and in addition, contribute to those responsible for teacher education at universities.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by European Social Fund, project 2014-2020.1.02.18-0645 (Enhancement of Research and Development Capability of Teacher Education Competence Centre Pedagogicum).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Krista Uibu

Krista Uibu is a professor of primary education in the Institute of Education at University of Tartu (Estonia). The wider fields of her research are teachers’ teaching practices and their dynamics, teaching styles and instructional approaches; relationships between primary school teachers’ teaching practices and their pupils’ language competence. She has a long-standing involvement in large research projects and is a member of the senior research staff.

Age Salo

Age Salo (PhD) is a school-based teacher educator of the University of Tartu and a teacher of Estonian language and literature in the Hugo Treffner Gymnasium (Estonia). Her main research interests are teachers’ beliefs, effective teaching practices, teachers’ professional development.

Aino Ugaste

Aino Ugaste is a professor in the Institute of Educational Sciences at Tallinn University (Estonia). The field of her research is connected with teachers’ professional development, early childhood education and parenting educational values. She has participated in several international research projects whose aim is to analyse children’s learning, teachers’ teaching practices.

Helena Rasku-Puttonen

Helena Rasku-Puttonen is a professor emerita at the Department of Teacher Education, University of Jyväskylä (Finland). Her areas of interest in research include learning communities, collaboration and social interaction at school and working life contexts.

References

- Adler, P. A., and P. Adler. 1987. Roles in Field Research: Vol. 6. Qualitative Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ambrosetti, A. 2014. “Are You Ready to Be a Mentor? Preparing Teachers for Mentoring Pre-Service Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39 (6): 30–42. doi:10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.2.

- Anspal, T., Ä. Leijen, and E. Löfström. 2019. “Tensions and the Teacher’s Role in Student Teacher Identity Development in Primary and Subject Teacher Curricula.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 63 (5): 679–695.

- Bazeley, P. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies. London: Sage Publications.

- Bietenbeck, J. 2014. “Teaching Practices and Cognitive Skills.” Labour Economics 30 (C): 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2014.03.002.

- Brackett, M. A., M. R. Reyes, S. E. Rivers, N. A. Elbertson, and P. Salovey. 2012. “Assessing Teachers’ Beliefs about Social and Emotional Learning.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 30 (3): 219–236. doi:10.1177/0734282911424879.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brophy, J. 2001. Motivating Students to Learn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Buchanan, R., B. A. Gueldner, O. K. Tran, and K. W. Merrell. 2009. “Social and Emotional Learning in Classrooms: A Survey of Teachers’ Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices.” Journal of Applied School Psychology 25 (2): 187–203. doi:10.1080/15377900802487078.

- Butler, B. M., and A. Cuenca. 2012. “Conceptualizing the Roles of Mentor Teachers in Student Teaching.” Action in Teacher Education 34 (4): 296–308. doi:10.1080/01626620.2012.717012.

- Cain, K. 2010. Reading Development and Difficulties. Oxford: Wiley–Blackwell.

- Clarke, A., V. Triggs, and W. Nielsen. 2014. “Cooperating Teacher Participation in Teacher Education: A Review of the Literature.” Review of Educational Research 84 (2): 163–202. doi:10.3102/0034654313499618.

- Cohen, E., R. Hoz, and H. Kaplan. 2013. “The Practicum in Preservice Teacher Education: A Review of Empirical Studies.” Teaching Education 24 (4): 345–380. doi:10.1080/10476210.2012.711815.

- Currie, N. K., and K. Cain. 2015. “Children’s Inference Generation: The Role of Vocabulary and Working Memory.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 137: 57–75. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2015.03.005.

- Danielson, C. 2013. The Framework for Teaching: Evaluation Instrument. Princeton, NJ: Danielson Group.

- De Groot-reuvekamp, M., A. Ros, and C. Van Boxtel. 2019. “ʽeverything Was Black and White … ’: Primary School Pupils’ Naive Reasoning while Situating Historical Phenomena in Time.” Education 3−13 47 (1): 18–33.

- Den Brok, P., T. Bergen, R. J. Stahl, and M. Brekelmans. 2004. “Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Control Behaviours.” Learning and Instruction 14 (4): 425–443. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.01.004.

- Estonian Government. 2011/2014. “National Curriculum for Basic Schools.” Riigi Teataja. https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/est_basic_school_nat_cur_2014_general_part_1.pdf

- Ferguson, C. 2002. “Using the Revised Taxonomy to Plan and Deliver Team-Taught, Integrated, Thematic Units.” Theory into Practice 41 (4): 238–243. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4104_6.

- Forslund-Frykedal, K., and E. H. Chiriac. 2014. “Group Work Management in the Classroom.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 58 (2): 222–234. doi:10.1080/00313831.2012.725098.

- Fraser, C. A. 2010. “Continuing Professional Development and Learning in Primary Science Classrooms.” Teacher Development 14 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1080/13664531003696626.

- Gillies, R. M., and M. Boyle. 2010. “Teachers‘ Reflections on Cooperative Learning: Issues of Implementation.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (4): 933–940. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.034.

- Good, T. L., C. R. Wiley, and I. R. Florez. 2009. “Effective Teaching: An Emerging Synthesis.” In International Handbook of Research on Teachers and Teaching, Edited by L. J. Saha and A. G. Dworkin, 803–816. Boston: MA: Springer.

- Haney, M., and V. Bissonnette. 2011. “Teachers’ Perceptions about the Use of Play to Facilitate Development and Teach Prosocial Skills.” Creative Education 2 (1): 41–46. doi:10.4236/ce.2011.21006.

- Huitt, W., and C. Dawson. 2011. “Social Development: Why It Is Important and How to Impact It.” Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/socdev.pdf

- James, M., and A. Pollard. 2011. “TLRP’s Ten Principles for Effective Pedagogy: Rationale, Development, Evidence, Argument and Impact.” Research Papers in Education 26 (3): 275–328. doi:10.1080/02671522.2011.590007.

- Jaspers, W. M., P. C. Meijer, F. Prins, and T. Wubbels. 2014. “Mentor Teachers: Their Perceived Possibilities and Challenges as Mentor and Teacher.” Teaching and Teacher Education 44: 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.08.005.

- Jennings, J. L., and T. A. DiPrete. 2010. “Teacher Effects on Social and Behavioral Skills in Early Elementary School.” Sociology of Education 83 (2): 135–159. doi:10.1177/0038040710368011.

- Khader, F. R. 2012. “Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs and Actual Classroom Practices in Social Studies Instruction.” American International Journal of Contemporary Research 2 (1): 73–92.

- Kuzborska, I. 2011. “Links between Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices and Research on Reading.” Reading in a Foreign Language 23 (1): 102–128.

- Lunenberg, M. 2010. “Characteristics, Scholarship and Research of Teacher Educators.” In International Encyclopaedia of Education, 3rd. ed. 7 vols. edited by E. Baker, B. McGaw, and P. Peterson, 676–680. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

- Lyle, J. 2003. “Stimulated Recall: A Report on Its Use in Naturalistic Research.” British Educational Research Journal 29 (6): 861–878. doi:10.1080/0141192032000137349.

- Mason, K. O. 2013. “Teacher Involvement in Pre-Service Teacher Education.” Teachers and Teaching 19 (5): 559–574. doi:10.1080/13540602.2013.827366.

- Muijs, D., and D. Reynolds. 2010. Effective Teaching: Evidence and Practice. London: Sage.

- Nilsson, P., and J. Van Driel. 2010. “Teaching Together and Learning Together–Primary Science Student Teachers’ and Their Mentors’ Joint Teaching and Learning in the Primary Classroom.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (6): 1309–1318. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.03.009.

- Opdenakker, M.-C., and J. Van Damme. 2006. “Teacher Characteristics and Teaching Styles as Effectiveness Enhancing Factors of Classroom Practice.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.008.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. “Two Decades of Developments in Qualitative Inquiry: A Personal, Experiential Perspective.” Qualitative Social Work 1 (3): 261–283. doi:10.1177/1473325002001003636.

- Pedagogicum, T. U. 2019. “Tartu Ülikooli Pedagoogilise Praktika Üldjuhend.” [General Guides to Pedagogical Practice]. https://www.pedagogicum.ut.ee/et/opetajakoolitus/leping-juhend-praktikaasutustele

- Pedaste, M., K. Pedaste, K. Lukk, P. Villems, and R. Allas. 2014. “A Model of Innovation Schools: Estonian Case-Study.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 112: 418–427. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1184.

- Perry, K. E., K. M. Donohue, and R. S. Weinstein. 2007. “Teaching Practices and the Promotion of Achievement and Adjustment in First Grade.” Journal of School Psychology 45 (3): 269–292. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2007.02.005.

- Richland, L. E., R. Frausel, and K. Begolli. 2016. “Cognitive Development.” In The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Theory in Psychology, edited by H. L. Miller, 1–6. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, .

- Salo, A., K. Uibu, A. Ugaste, and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2019. “The Challenge for School-based Teacher Educators: Establishing Teaching and Supervision Goals.” Teacher Development 23 (5): 609–626. doi:10.1080/13664530.2019.1680426.

- Sandvik, L. V., T. Solhaug, E. Lejonberg, E. Elstad, and K. A. Christophersen. 2019. “Predictions of School Mentors’ Effort in Teacher Education Programmes.” European Journal of Teacher Education 42 (5): 574–590. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1652902.

- Sayeski, K. L., and K. J. Paulsen. 2012. “Student Teacher Evaluations of Cooperating Teachers as Indices of Effective Mentoring.” Teacher Education Quarterly 39 (2): 117–130.

- Teague, G. M., V. A. Anfara Jr, N. L. Wilson, C. B. Gaines, and J. L. Beavers. 2012. “Instructional Practices in the Middle Grades: A Mixed Methods Case Study.” NASSP Bulletin 96 (3): 203–227. doi:10.1177/0192636512458451.

- Uibu, K., A. Salo, A. Ugaste, and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2017. “Beliefs about Teaching Held by Student Teachers and School-based Teacher Educators.” Teaching and Teacher Education 63: 396–404. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.016.

- Uibu, K., and E. Kikas. 2014. “Authoritative and Authoritarian-inconsistent Teachers’ Preferences for Teaching Methods and Instructional Goals.” Education 3–13 42 (1): 5–22.

- Van Den Broek, P., D. N. Rapp, and P. Kendeou. 2005. “Integrating Memory-based and Constructionist Approaches in Accounts of Reading Comprehension.” Discourse Processes 39 (2–3): 299–316. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2005.9651685.

- Van Velzen, C., and M. Volman. 2009. “The Activities of A School-based Teacher Educator: A Theoretical and Empirical Exploration.” European Journal of Teacher Education 32 (4): 345–367. doi:10.1080/02619760903005831.

- Vaughn, M. 2014. “Aligning Visions: Striking a Balance between Personal Convictions for Teaching and Instructional Goals.” The Educational Forum 78 (3): 305–313. doi:10.1080/00131725.2014.912369.

- Vesterinen, O., A. Toom, and S. Patrikainen. 2010. “The Stimulated Recall Method and ICTs in Research on the Reasoning of Teachers.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 33 (2): 183–197. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2010.484605.

- Walpole, S., M. C. McKenna, X. Uribe-Zarain, and D. Lamitina. 2010. “The Relationships between Coaching and Instruction in the Primary Grades: Evidence from High-poverty Schools.” The Elementary School Journal 111 (1): 115–140. doi:10.1086/653472.

- White, E., C. Dickerson, and K. Weston. 2015. “Developing an Appreciation of What it Means to Be a School-based Teacher Educator.” European Journal of Teacher Education 38 (4): 445–459. doi:10.1080/02619768.2015.1077514.