ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to report the development and implementation of a STEM teacher attraction intervention based on person-environment (and person-vocation) fit theory. Study 1 reports the administration of a 'realistic job preview' (RJP) intervention requiring participant responses, followed by experienced teacher feedback and a tailored fit message to 111 university students in STEM-related fields. Results showed a significant relationship between RJP performance and interest in a teaching career, even after controlling for prior career intentions. Study 2 reports the results from individual interviews with 14 university students studying STEM-related subjects on the factors contributing to career-decision making, especially regarding teaching as a career. The 16 codes were distilled into three themes: the role of personal reflection, critical influences on career decisions, and patterns of change. We conclude with suggestions for implementation of RJPs as a supplement to current attraction and recruitment approaches.

Introduction

Recruiting high quality teachers is an international problem, with shortages especially acute in STEM-related subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics; See and Gorard Citation2019). Teacher attraction strategies typically involve an appeal to one of two motivations to enter the profession: (a) they emphasise the personal utility of pursuing a teaching career by offering grants and bursaries for training, higher salaries, improved working conditions, and/or (b) they emphasise the social utility of teaching by highlighting how a teaching career can make a social contribution in terms of improving the lives of children and advancing positive social change (e.g. the UK Department for Education’s [DfE] Every Lesson Shapes a Life campaign). However, attraction and recruitment strategies based on ‘seduction’ approaches have a downside: although they may attract applicants in the short term, they may lead to unrealistically high expectations, lower job satisfaction, and increases in quitting intentions (Baur et al. Citation2014). One generally unexplored avenue to building teacher recruitment strategies is using a ‘person-environment fit’ approach, in which prospective teachers are identified and recruited based on the compatibility between individual characteristics and the work environment. In this article, we present a mixed-methods study demonstrating how a proof-of-concept person-environment fit approach using ‘realistic job previews’ (RJPs) could provide an additional method used to recruit teachers in hard-to-staff fields.

Teacher recruitment landscape

Many countries are currently facing significant teacher shortages. In 2016 UNESCO predicted that there was a global shortfall of nearly 70 million teachers, with acute shortages for both primary and secondary teachers. A recent OECD reported that 37.6% of school leaders in England reported teacher shortage levels serious enough to hinder educational effectiveness, with levels surpassed only by a handful of countries internationally, i.e. Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Italy, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Vietnam. Attempts to remedy the shortages are usually addressed through financial incentives, and although these financial attractants may be successful for initial recruitment, their impact tends to dissipate or disappear when the incentive is removed (See et al. Citation2020). The current COVID-19 crisis may increase the pace of teacher recruitment, and teacher shortages may be temporarily remedied through the current crisis and coming recession, as recent graduates find it more difficult to find vacancies in businesses that may reduce their intake of new employees due to economic constriction. Evidence from the 2008 financial crisis showed that occupations such as teaching are more ‘recession proof’ than many other fields, with improvements seen in teacher recruitment, although the effects tend to fade over time (Fullard Citation2020). However, the pandemic may also increase the rate of attrition of current teachers who are experiencing higher levels of anxiety and workload due to budget shortfalls, changes in workload, and health challenges (Darling-Hammond and Hyler Citation2020). There is a current and projected shortage of teachers in many subjects and locations, but the problem may be especially acute in certain subjects, including STEM subjects.

Attracting and recruiting STEM teachers

In many countries, there is an acute shortage of teachers in certain fields, especially STEM, modern languages, and information and technology (e.g. Heinz Citation2015; Naylor, Jones, and Boateng Citation2019; Podolsky et al. Citation2019). In the UK, the shortage of teachers in STEM-related fields is particularly concerning, with mathematics and science teachers consistently under-recruited since at least 2011–2012, and with growing shortfalls predicted (Foster, Citation2019). Focused attempts have been made to recruit university STEM students into science teaching, because, in many cases, potential STEM teachers have more career opportunities than teachers in other fields (Kunz et al. Citation2020). In a qualitative cross-case analysis study, Borgerding (Citation2015) trialled a science education summer internship intervention in the US with science undergraduates and found some impact on interest in teaching, but the number of participants was very small (n = 5). Offering alternative certification pathways to undergraduates may initially attract STEM teachers, but these pathways tend may lead to high attrition rates (in some cases very high attrition rates – up to 90% after the third year in the case of Teach for America, Kane, Rockoff, and Staiger Citation2008). Student loan forgiveness programmes and other financial incentives can be effective when the financial incentive is substantial enough, and, ironically, when the interest in teaching is already high (Podolsky et al. Citation2019). Many of the programmes designed to attract and recruit STEM students into teaching have been cumbersome and expensive, and supported by only modest evidence (e.g. Borgerding, Citation2015; Podolsky et al. Citation2019). A common theme in teacher recruitment efforts is that external factors that initially increase the flow of graduates into teaching (financial incentives or global economic uncertainty) may not make a lasting impact if the fit between applicant and job is not adequately considered.

Theories relevant to attraction and recruitment

Person-environment fit

Person-environment fit is one of the major theories in psychology, and describes how people who are well matched to an environment, for example their workplace, demonstrate positive psychological adjustment and performance (Barrick and Parks-Leduc Citation2019). In education settings, recent studies have shown that teachers who believed their abilities and attitudes closely matched the demands of teaching were less likely to leave the profession (De Cooman et al. Citation2009; Player et al. Citation2017). Most of the work on PE fit has been conducted in organisational psychology, where fit has been studied at various levels, including fit with the organisation (person-organisation fit), the particular job (person-job fit), and with choice of vocation (person-vocation fit), which is the focus of this article. There is considerable overlap between the levels of person-environment fit constructs, but they are conceptually different: an employee can fit well with a general occupation (high person-vocation fit) but finds herself ill-suited to a particular organisation (low person-organisation fit). Vogel and Feldman (Citation2009) found a strong association between person-vocation fit and workplace attitudes (job satisfaction, commitment, perceptions of career success, and retention), and workplace performance. A large-scale meta-analysis that explored predictors of applicant attraction (Uggerslev, Fassina, and Kraichy Citation2012) showed that perceived fit was the strongest relative and unique variance predictor of applicant attraction across multiple stages of the recruitment process, with a large effect size (R = .55), suggesting that perceived fit plays a key role in career decision-making. In this study, the focus is on the fit between the person and teaching (person-vocation fit).

FIT-choice theory

Building on person-environment fit and expectancy-value theories, Watt and Richardson’s FIT-Choice motivation theory provides another framework for understanding why people enter the teaching profession (e.g. Watt & Richardson, Citation2007), with application to teacher recruitment. The FIT-Choice framework defines expectancies as a form of competence and self-efficacy beliefs (How well could I do in this profession?) which interact with interest and beliefs about the utility or value of a career choice. Self-efficacy is enhanced when positive verbal messages about capabilities are provided (such as through fit messages), and through observation of successful models (such as through feedback from experienced professionals). Bandura (Citation1997) suggests that self-efficacy beliefs can be enhanced through observation of successful others and through verbal messages, such as are provided through feedback and fit messages.

Utility values can be broken down into personal utility (How do I benefit from this career choice?) and social utility (How could this career help me make a social contribution?). When making career decisions, individuals perform an implicit calculation based on these three factors: perceived competence, personal utility, and the social utility of their potential career choice. However, in education settings, the vast majority of teacher recruitment efforts have been based on promoting the personal utility of teaching (through financial incentives, workload reductions) and the social utility of teaching (e.g. Every lesson shapes a life, DfE Citation2020), often at considerable cost to taxpayers (e.g. Carr Citation2020). Broad messages to promote personal and social utility of teaching are possibly effective in attracting applicants, but less effective in retaining teachers in the long term (e.g. See et al. Citation2020). Little attention in education has been paid to developing recruitment strategies that use a person-environment fit framework, where fit messages are provided to candidates to help them evaluate the match between their personal characteristics and those required for success in teaching.

Feedback and fit messages

From a social cognitive theory perspective, being in the receipt of feedback and fit messages delivered by experts can form two sources of self-efficacy: verbal persuasion and vicarious experience (Bandura Citation1997). Uggerslev, Fassina, and Kraichy (Citation2012) concluded that recruitment processes could be improved with the inclusion of fit messages to applicants before and during the recruitment process. However, determining fit is not straightforward: fit can be viewed from the perspective of the applicant and from the organisation. For an organisation, person-vocation fit is the focus of the selection process, and is evaluated through screening and interviewing to assess cognitive and non-cognitive attributes and relevant background experiences (e.g. Klassen et al. Citation2021). From the applicant’s perspective, their own fit is determined through a self-assessment of personal characteristics (e.g. cognitive and non-cognitive attributes) measured against the perception of the attributes needed for success in a particular vocation. When considering a teaching career, this self-assessment of fit interacts with perceptions of personal and social utility of the profession, and by the messages delivered by the organisation through recruitment messaging, such as through advertisements in social and traditional media.

When receiving feedback and fit messages, a candidate will ask herself three questions, the first two corresponding to personal utility (personal benefits) and social utility (social contribution), and the third about person-vocation fit: Do my knowledge, skills, and attributes fit with those demanded by the profession? Each potential candidate will weigh these three factors using a different calculus, but each of these factors play a part in making career decisions.

Although recruitment messages about the personal and social utility are an important part of an overall recruitment strategy, a higher degree of specificity in recruitment messages is preferable, because specific fit messages produce more favourable applicant perceptions and reactions (Roberson, Collins, and Oreg Citation2005). Meaningful feedback on fit demands some form of interaction between an organisation and potential candidates as part of a long-term recruitment process, something that can be expensive and time consuming in practice. In the UK, the DfE references the Discover Teaching programme in its recent recruitment strategy (DfE, Citation2020), providing opportunity for teaching internships, school taster days, and a virtual reality classroom experience. However, these programmes are difficult and expensive to scale up to reach the large numbers of potential candidates needed to maintain the teaching pipeline. In other fields, a scalable recruitment approach using realistic job previews provides a way of providing potential applicants with valuable data regarding their fit with the profession.

Realistic Job Previews (RJPs)

Realistic job previews (RJPs) are a recruitment method where potential applicants are presented with a realistic view of situations they can expect from a job. Research on RJPs has been conducted for over a half-century, with results showing that RJPs delivered before training or employment can promote early integration into a new field, leading to better retention rates and job success (Baur et al. Citation2014). The integration of RJPs into the recruitment process affords three benefits: (a) they communicate an honest and believable portrayal of a job, leading to higher levels of trust for potential applicants (the ‘air of honesty’ hypothesis), (b) they lower initial expectations so that new trainees are prepared for the inevitable ups and downs encountered in the job (the ‘met expectations’ hypothesis), and (c) they lead to appropriate self-selection where applicants will self-select out if the job is not a good fit (the ‘self-selection’ hypothesis). Combining RJPs with explicit person-vocation fit feedback builds on the self-selection hypothesis: the combination of RJP + feedback attracts potential candidates who receive positive fit feedback, and deters those who receive a message that they may not be well-suited to a particular vocation (Earnest, Allen, and Landis Citation2011; Roberson, Collins, and Oreg Citation2005).

RJPs can be delivered through a range of materials (written or video presentations) that provide applicants with balanced (positive and negative) information about the potential job. The accuracy and specificity of recruitment messages is associated with enhanced person-vocation fit, meaning that applicants for training or employment can make more informed decisions about entering training or employment, resulting in better perceived fit and increased intentions to apply (Roberson, Collins, and Oreg Citation2005). Feedback messages related to person-vocation fit can form a component of the RJP, similar to the approach taken in situational judgement tests (SJTs), a scenario-based method frequently used for selection in medical education, and increasingly, in teacher education (e.g. Klassen et al. Citation2020b). In both applications of these two scenario-based methods, applicants are (a) exposed to a realistic scenario, (b) answer questions about appropriate courses of action, and (c) are provided with a fit message based on the accuracy of their responses (as compared to subject matter experts). For teacher recruitment, the advantage of delivering fit messages to potential candidates using an RJP approach is that applicants who may not have considered teaching as a career can be provided with authentic, detailed, and believable portrayals of the workplace environment and receive an indication of how their decision-making fits with professionals in the field.

Current study

In this article, we explore how an RJP intervention with fit messages grounded in social cognitive and PE fit theories might be used to attract prospective teachers to the profession. In Study 1, we measure the effects of an RJP intervention on 111 university students’ interest in teaching as a career, self-efficacy for teaching, the perceived match between personal attributes and those attributes required to be a teacher. In Study 2, we interviewed 14 university students from STEM-related disciplines (economics, physics, mathematics, and engineering) to gain an understanding of the factors that influence their decisions to consider teaching as a career. The primary research questions (and corresponding hypotheses) were:

(Study 1) Is there an association between person-vocation fit as measured in a brief RJP intervention and university students’ teaching self-efficacy, interest in teaching as a career, and perceived match between personal attributes and those attributes necessary for teaching? We propose three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: We expect that person-vocation fit will be positively associated with self-efficacy (based on social cognitive and expectancy-value theories)

Hypothesis 2: Person-vocation fit will be positively associated with interest in teaching as a career (based on FIT-Choice theory)

Hypothesis 3: Person-vocation fit will be positively associated with perceived match between personal attributes and the attributes necessary for teaching (based on person-environment fit and social cognitive theories).

(Study 2) What do university students in STEM-related disciplines say about the influences on their career decision-making?

Study 1 method

Participants and procedure

The sample for the current study was recruited via regular newsletters sent out to undergraduate students in STEM or STEM-related fields through careers advisors who had agreed to disseminate our email invitation to their students. We initially contacted departments of Biology, Chemistry, Economics (a source of maths applicants to PGCE programmes), Electrical Engineering, Mathematics, and Physics, and received responses from careers advisors in Economics, Physics, Mathematics, and Electrical Engineering. A total of 118 students started the online questionnaire. Data from seven participants were deleted as they quit the survey without responding to any questions or with only responding to a few questions asking for socio-demographic characteristics. The sample analysed in this study thus consisted of 111 participants. The participants were on average 22.99 years old (SD = 2.62) and 34.2% identified as female. The participants were enrolled in the following degree programmes: Economics (45.9%), Physics (20.7%), Mathematics (12.6%), and Electrical Engineering (9.9%), with the remaining participants (10.8%) enrolled in cross-degree programmes with a STEM component.

The online questionnaire started with questions regarding key sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age). After that, participants were asked to rate whether they planned to pursue a career in different fields (e.g. research, health profession etc.). One of these items referred to a career in teaching, and was included in order to be able to control for prior intentions to pursue a teaching career in the analyses. After that, the participants worked on the realistic job preview task (with follow-up questions) and then filled out the questionnaire (scales assessing self-efficacy, interest in exploring teaching as a career, and the match between own skills and skills required to be a teacher). Each participant who participated in the study received a shopping voucher (£6).

Measures

Realistic job previews

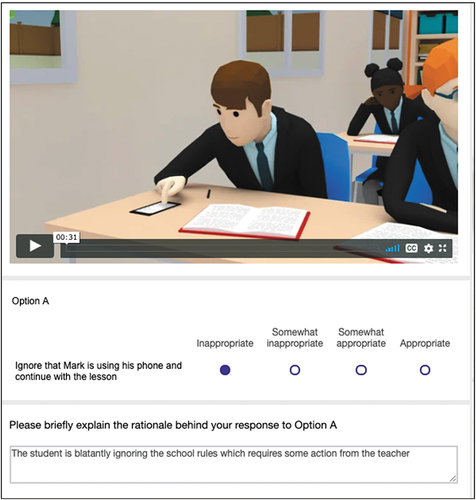

The RJP intervention consisted of four animated classroom scenarios delivered to participants’ phone, tablet, or computer. The RJPs were initially developed for use in situational judgement tests for selection into initial teacher education programmes (see Klassen et al. Citation2020b).

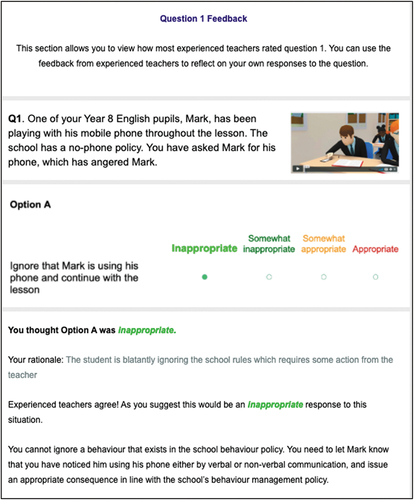

provides an example screenshot of one of the scenarios with participant options and provides an example of the teacher feedback. For each scenario, participants:

Viewed a brief classroom scenario with audio narration that presented a dilemma

Rated the appropriateness of three possible responses to the dilemma posed in the scenario using a (1) Inappropriate to (4) Appropriate scale

Wrote a reflective rationale for their response

Received real-time feedback on the alignment between their own ratings and the ratings from experienced teachers

Were provided with a rationale from experienced teachers for appropriate responses to the dilemma

The scoring key for the RJPs had been established based upon concordance panels with subject matter experts in the field by adopting a consensus approach (see Bergman et al. Citation2006 for details). A panel of experienced teachers developed the initial scoring key which was then adapted based upon level of expert consensus, item difficulty, item-total correlations, and applicant (teacher education candidates) scoring patterns. The scoring was based on the scoring system described by Klassen et al., (Citation2020). Points were allocated based on the extent to which participants’ responses align with the established scoring key; for example, student teachers were allocated three points if their response was in direct alignment with the scoring key, two points if their answer was one position away, one point if their answer was two positions away, and no points if three positions away.

After completing all scenarios, the total score (i.e. the sum of the scores of all scenarios) was shown to the participants and they received a ‘fit’-message: Depending on their scores, one of four messages was shown to them: (1) ‘Excellent fit (You think like a teacher! Your judgement matches closely with that of experienced teachers)’ for those with very high scores (i.e. 29–36), (2) Very good fit (You think like a teacher! Your judgement matches quite closely with that of experienced teachers), for those with scores between 21 and 28, (3) ‘Quite good fit (Some experienced teachers think differently than you about these situations. But you have the capability to improve)’ for participants with scores between 13 and 20, and (4) ‘Some areas of fit (Most experienced teachers think differently than you about these situations)’ for those with 12 or less).Footnote1

It should be noted that the different scenarios were not meant to measure a unidimensional construct and instead captured distinct complex classroom situations. The different single scenarios were all statistically significantly correlated with the total score (rs ranging between .429 and .639, all ps < .01), but they were not significantly correlated with each other (rs ranging between −.132 and .175, all ps > .05). In addition, due to their multi-dimensional nature, situational judgement tests and their measurement properties cannot be compared with ‘classical’ self-report questionnaires assessing e.g. self-efficacy. SJTs are usually constructed to cover multiple domains (although see Tiffin et al. Citation2020 on construct-driven SJTs) and typically show lower internal consistency (but higher predictive validity) than single construct measures; conventional internal consistency indices (i.e. alpha) are not considered as appropriate to assess SJT reliability when item heterogeneity is high, with test-retest reliability recommended (Catano, Brochu, and Lamerson Citation2012).

Self-efficacy

We measured self-efficacy with three items adapted from the Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES, Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy Citation2001). The response format ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The three items used in this study have shown satisfactory reliability and validity as a short form in previous studies (e.g. Klassen and Durksen Citation2014). In this study, the three-item scale (e.g. ‘I am confident that I could create a positive classroom atmosphere’) showed a Cronbach’s α of .850.

Interest in exploring a teaching career

Three items adapted from Hackett et al.’s occupational commitment scale (Hackett, Lapierre, and Hausdorf Citation2001) were employed to assess participants’ interest in exploring teaching as a career. Following the question: ‘Compared to how you felt before completing the activity, how much did your views change on the following items?’, the participants rated the extent to which their views had changed on a with 7 response categories (−3 = Less interested, 0 = no change, 3 = more interested, sample item: ‘I am interested in exploring teaching as a career’, α = .891). It should be noted that we re-coded the responses in accordance with the response format of the other scales (i.e. 1–7 instead of −3 to 3) prior to the analyses.

Attribute match

Three items adapted from Chang et al. (Chang, Shen, & Judge, Citation2016) were used to measure the perceived match between participants’ own attributes and the attributes required for a teaching career (sample item: ‘There is a close match between my skills, knowledge, and abilities and those required for a teaching career’, α = .745). The response format ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Control variables

One item adapted from Hackett, Lapierre, and Hausdorf (Citation2001) was used to measure participants’ career intentions prior to working on the scenario-based task (‘After I graduate, I am interested in exploring a career as a teacher’). Participants indicated their level of agreement with the statement on a response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In addition, we included gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and age as further control variables.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted with Mplus Version 8.2 using the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR). In order to investigate whether higher scenario-scores and thus, a stronger ‘fit’-message predicted higher levels of self-efficacy and interest, and a higher perceived match between own skills and skills required to be a teacher, we ran a regression using scenario scores as predictor for the three outcomes (Model 1). As a next step, we included the control variable (item asking the participants to indicate if they considered exploring teaching as a career that was assessed before they worked on the scenarios), re-ran the analyses while controlling for the effects of the control variable on the outcomes. To provide comprehensive information, we also estimated the effect of the control variable on scenario scores (Model 2). Building on Model 2, we included key socio-demographic variables (gender, age) as further control variables and re-estimated all effects (Model 3). In addition to the effects of gender and age on the outcomes, we also report effects on scenario scores and prior interest in exploring teaching as a career. There was no missing data on the scenario scores, self-efficacy, interest, the perceived match between own skills and skills required to be a teacher, and the item assessing whether participants considered exploring teaching as a career. Information on age was missing for one participant and information on gender was missing for five participants. For the effects of gender and age (Model 3), the participants with missing information were excluded from the analyses. All analyses were conducted relying on manifest variables and not latent variables due to the relatively small sample size. We report standardised and unstandardised regression coefficients. The standardised estimates can be interpreted according to Cohen’s guidelines (1988) guidelines with values above .10 indicating small effects, values above .30 indicating moderate effects, and values above .50 indicating large effects. All significance testing was performed at the .05 level.

Study 1 results

shows descriptive information and correlations among all variables. On the RJP task, most participants scored in the ‘excellent fit’ or ‘very good fit’ range, with a mean of 28.30 (SD = 2.59) out of a possible 36 points. In total, 51/105 participants scored in the ‘excellent fit’ range, 53 participants scoring in the ‘very good fit’ range, and 1 participant scoring in the ‘quite good fit’ range. Scores on the self-efficacy measure ranged from 1–7, with a mean of 4.91 (SD = 1.41). Scores on the interest measure had a mean of 4.14 (SD = 1.03), and scores on the ‘match’ measure were 4.67 (SD = 1.28).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, and bivariate correlations among all variables.

Bivariate correlations in show a significant association between RJP scores and interest in a teaching career, but not between RJP scores and self-efficacy, or attribute match. presents the regression model predicting self-efficacy, interest, and match with scores on the scenario task. In Model 1, when estimating all relations without controlling for prior career intentions, we did not obtain a statistically significant effect for self-efficacy (β = −0.078, p > .05). Similarly, scenario scores did not statistically significantly predict the match between own attributes and the attributes required to be a teacher (β = 0.058, p > .05). However, scenario scores significantly predicted interest in exploring a teacher career (β = 0.256, p < .01).

Table 2. Results from the regression model 1 predicting self-efficacy, interest in teaching, and match between own skills and skills required to be a good teacher with scores on the scenario-based task, results from regression model 2 additionally controlling for prior career intentions to explore teaching as a career assessed before working on the scenario-based task, and results from regression model 3 additionally controlling for gender and age.

The findings were robust after including the control variable prior career intentions: In Model 2 with the control variable, the effects for self-efficacy and for the perceived match between own attributes and the attributes required to be a teacher remained not statistically significant (β = −0.113, p > .05, and β = 0.006, p > .05, respectively). Scenario scores still statistically significantly predicted interest (β = 0.205, p < .01). The control variable prior career intentions statistically significantly predicted self-efficacy (β = 0.328, p < .01), match (β = 0.487, p < .01), and interest (β = 0.475, p < .01), but not scenario scores (β = 0.107, p > .05).

We additionally included gender and age as further control variables (Model 3). The same pattern of findings emerged: the effects for self-efficacy and for the perceived match between own attributes and the attributes required to be a teacher were not statistically significant (β = −0.097, p > .05, and β = 0.013, p > .05, respectively). Scenario scores statistically significantly predicted interest (β = 0.215, p < .01). The control variable prior career intentions statistically significantly predicted self-efficacy (β = 0.309, p < .01), match (β = 0.499, p < .01), and interest (β = 0.486, p < .01), but not scenario scores (β = 0.107, p > .05).

The findings confirmed Hypothesis 2, that person-vocation fit would be positively associated with interest in teaching, even when controlling for prior career intentions. However, the results did not support Hypothesis 1 (association with self-efficacy) or Hypothesis 3 (association with perceived match) regardless of the inclusion of the control variable of prior career intentions.

No statistically significant effect was found for the control variable age (for self-efficacy: β = 0.075, p > .05, for match: β = 0.056, p > .05; for interest: β = 0.013, p > .05, for scenario scores: β = 0.014, p > .05). Gender statistically significantly predicted self-efficacy, with higher scores for males than for females (β = −0.442, p < .05), whereas no statistically significant effects were obtained for all other variables (for match: β = 0.069, p > .05, for interest: β = −0.245, p > .05, for scenario scores: β = 0.228, p > .05).

Study 1 brief discussion

In Study 1 we found that scores from an RJP intervention were significantly associated with interest in exploring a teaching career, with a small-to-medium effect size, even after controlling for prior career interests and key socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender). The results suggest that objective person-vocation fit measured using an RJP intervention is related to interest in a teaching career among university students studying STEM-related subjects. To follow up on this finding, we conducted interviews with students who had completed the RJP intervention in order to understand their attitudes towards teaching as a career, other attraction methods, and in particular, their reactions to completing the RJP intervention.

Study 2 method

Participants

Participants who completed the initial online survey were invited to be interviewed for Study 2. Of the original 111 respondents, 39 indicated that they would be willing to be interviewed. From this group of 39, 17 participants were selected based on subject representation and from responses in Study 1 that indicated an openness to a range of career paths (i.e. we did not select participants who indicated strongly fixed career paths in a non-education field). Three participants did not respond to further prompting for interviews. The final sample for Study 2 included 14 students (13 undergraduates; 1 Masters) representing Economics and Finance (5) Physics (3), Engineering (4), Maths (2). The mean age of participants was 22.3 years (55.6% female).

Procedure

The participants were invited to an interview to take place via video-conference or telephone, and for which they would be offered an additional £6 Amazon voucher. The interviewer used a structured interview protocol to conduct the interview. The interviewer opened with an introduction and then posed general questions about participants’ academic background and general career choices in order to establish rapport (e.g. ‘What kind of careers are you considering after your degree?’ ‘How will you make this decision?’). The interview then moved to questions about attraction and recruitment methods:

Have you considered teaching as a career? (If yes) What triggered your interest? (If no) Why do you think you have not considered it?

What kinds of information would persuade you to explore teaching?

You recently completed … (RJPs). Do you remember your results on this activity? What were your thoughts? Did it change your mind about teaching as a career?

Analysis

Data from the interviews were analysed using a constant comparative approach (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) in which we categorised and compared code segments through the use of a code map built on deductive and inductive code categories. We began with a set of a priori start codes that reflected the key variables from Study 1 (e.g. teaching self-efficacy, interest, person-vocation fit) and collectively developed a set of further codes that emerged through multiple readings of the interview data. The reliability of the coding process was established by having two authors independently reviewing the transcripts and collaboratively discussing the coding decisions. Next, the two coders independently coded sections of the interviews and resolved coding disagreements through consensus. A code map was used to organise the themes and to identify the overarching themes. Due to the multiple relationships between codes and themes, we allowed themes to share codes; that is, a single code could be applied to multiple overarching themes.

Study 2 results

A total of 16 codes were identified, subsequently categorised into 3 themes that provide an inductively-derived representation of the codes and the key research questions: Role of Personal Reflection, Critical Influences on Career Decisions, and Patterns of Change. A code map representing the relations between codes and themes can be viewed in . The supporting quotes from participants are identified with participant number and gender (e.g. 10 m is participant 10, male).

Role of personal reflection

Participants in the interviews considered their own personal characteristics and experiences, and weighed their own strengths and weaknesses against the perceived demands of a teaching career. This theme included codes covering diversity of skill-set required, cognitive and non-cognitive attributes, expectations for teaching, interest, fit between personal characteristics and the profession, observation of models, and impact of the intervention.

The impact of the intervention was noted by several of the participants, especially in comparison to other forms of advertising/persuasion, e.g. ‘The biggest thing is that it (the RJP activity) stuck in my mind, I’ve thought about it since … it’s not like a conversation that you just forget’ (4 F). The personal reflection theme included a comparative element, whereby the feedback from practicing teachers brought about an analysis of fit: The activity showed that I had similar ideology as a teacher so made me think that maybe I would be suitable; it really helped me think about how teachers think (3 m). Not all of the reflections on teaching fit were positive, e.g. I realise that I’m just not patient enough (6 m), and The scenarios made me think about the struggles of teaching (4 f).

The RJP intervention brought about reflection on personal characteristics perceived to be key for teaching success. One of the key non-cognitive attributes reflected on by participants vis-à-vis the RJP activity was confidence (self-efficacy), especially associated with the feedback provided, e.g. The feedback made me more confident (10 m), Before this I felt confident that I would have the characteristics and now I feel even more reassured (13 f).

Critical influences on career decisions

This theme captured codes relating to the factors that attracted, and deterred, participants from pursuing a teaching career, including references to the current intervention, advertisements for teaching (e.g. Every lesson shapes a life), career progression, sources of information, observation of models (positive and negative), and personal and social utility. Interviewees reported viewing recruitment advertisements from Teach First and the Department for Education (DfE) on social media (Instagram, Facebook), on television, and on public transport. Views were mixed about the persuasiveness of the advertisements, e.g. They don’t really have an impact, 11 m, and I’m sceptical as to whether adverts should be used to promote teaching (11 m). Three of the participants suggested that more explicit information about the career path progression available in a teaching career would be beneficial, e.g. Career progression should be advertised; what is teacher training a stepping stone to? (4 f). In terms of personal utility, several of the participants noted that the tax-free grant for training seemed generous and appealing. Influences on career decision-making included parents and especially past teachers, e.g. I had a very inspirational physics teacher who was very passionate about physics and … who clearly enjoyed what he did (3 m).

The RJP intervention was noted as a potential source of information for career decision-making, I found this quite exciting! Made me think that there are more aspects to school life that make teaching more fun (8 f), although not all agreed: I thought the scenarios were an over-simplification of the role, and not particularly influential (5 f), and You should show candidates what they gain from teaching. If the scenarios included success stories it might be more motivating (1 m).

Patterns of change

In this theme, participants noted how their thinking about pursuing teaching as a career has changed, due to a range of experiences and activities, including the RJP intervention. Codes in this theme included, role clarity based on experiences, observation of models, attitude change, fit with the profession, interest, and impact of the intervention. In terms of change associated with the intervention, several participants noted changes in the way of viewing the profession after the RJP, for example, Actually after this activity I looked up more information. I feel my career interests have broadened after this survey (8 f), and It (the RJP) has made me think about it more (13 f), and It did make me feel more positive about a career in teaching. It is not a closed door (2 m). The authenticity of the intervention was noted by several participants, It felt like having a go at being a teacher (13 f), although not all were unequivocally positive about a potential career: (After completing the RJP activity) I thought ‘oh this is something I could do, perhaps it’s not all that bad’ (7 f).

In general, patterns of change were influenced by past models, especially successful teachers (parents, influential teachers), from experiences such as mentoring or volunteering in school-related experiences, and less so by recollections of advertisements published by DfE and Teach First. Participants rated the RJP activity as an intervention that was authentic, valued, and generally a positive influence that in some cases evoked consideration of change in career intentions.

Study 2 brief discussion

The results from Study 2 showed three themes derived from the 16 codes applied to the interview data. Participants were generally positive about the impact of the RJP intervention, and noted its influence on fostering personal reflection, career decision-making, and change related to their career choices. Of particular interest were the reports that the RJP increased interest in the profession and activated behavioural changes (I looked up more information [about teaching]) in contrast to the general consensus that social media campaigns (for example from DfE) had modest impact on career decision-making.

General discussion

High levels of teacher shortages have been noted internationally (OECD Citation2019), with shortages in specific subject areas – including STEM subjects – particularly acute. Teacher recruitment practices and policies have tended to emphasise the personal and social utility of the profession, often at high cost and with uncertain effectiveness (Podolsky et al. Citation2019). University STEM students may have more career options than students in some other fields (Kunz et al. Citation2020), but offering financial incentives (loan forgiveness or bursaries) to persuade STEM students to enrol in teacher training programmes may only temporarily address teacher shortages. Perceived fit is one of the strongest predictors of attraction to a job or vocation (Uggerslev, Fassina, and Kraichy Citation2012), yet recruitment strategies and methods using a person-vocation fit approach have rarely been used in education. The two studies in this article provide insight into possible new approaches to attract and recruit applicants into teacher education by providing exposure to realistic teaching situations and by delivering detailed and tailored fit messages about applicants’ fit to teaching. Building on research from organisational psychology and grounded in theory, realistic job previews (RJPs) have the potential for use as a tool in the teacher attraction and recruitment process.

We posed two primary research questions, the first question including three hypotheses about the relations between an RJP intervention and self-efficacy (H1), career interest(H2), and attribute match (H3), and the second about the internal and external influences on career decision-making for university students in STEM-related disciplines. We found that scores on a brief (15–20) minute intervention were associated with career interest, even after controlling for prior interest in teaching, but not significantly associated with teaching self-efficacy or perceptions of attribute match. In response to research question 2, we found that potential applicants were aware of, but generally unpersuaded by, current advertisements designed to promote teaching as a career. Most of the participants in the Study 2 interviews reported a flexibility to their career plans and noted that the RJPs had the potential to change the ways that they viewed the teaching profession. Changes in career intentions were also influenced by influential examples and models, as proposed in self-efficacy theory (Bandura Citation1997), especially previous teachers and in some cases, parents. Short-term changes were associated with the RJP intervention, although further work is needed to understand the robustness of these changes, as we did not measure longer-term changes in attitudes and behaviours.

Subjective and objective person-vocation fit

The fit between a potential applicant and a teaching career is influenced by beliefs about the personal and social utility of teaching, but also by the perception of fit with the attributes required for success in the profession (Watt & Richardson, Citation2007). Self-assessment of this fit might be gained through relevant experiences, for example, through getting feedback from volunteering in a school, or from delivering informal teaching in a community club. However, subjective person-vocation fit may be inaccurate due to insufficient information; beliefs about potential teaching competence may be mis-guided if relevant experiences are limited or if messages from important others are either not forthcoming or are not convincing. The scenarios in RJPs deliver a believable snapshot of the workplace that can enhance the impact of recruitment messaging, but they can also be developed, as is the case in the intervention in this article, to provide relatively ‘objective’ feedback about fit. The alignment with experienced teachers is the kind of objective feedback that is valuable but rarely experienced in the recruitment phase (Uggerslev, Fassina, and Kraichy Citation2012). Although the results in Study 1 did not show a significant link between the RJP and teaching self-efficacy or attribute match, it may be that the intervention was insufficiently powered to effect change in these two areas.

How ‘realistic’ should realistic job previews be?

One problem with a recruitment strategy built on the promotion of social utility (e.g. the DfE’s Every lesson shapes a life campaign), is that some teacher trainees will hold unrealistic expectations when the inevitable challenges of teaching crop up, resulting in high levels of attrition in training and at the early career stage (Baur et al. Citation2014). In order to reduce attrition, potential applicants considering entering the teaching profession should consider the rewards and the typical challenges to be faced in the career. Realistic job previews are designed, by definition, to be authentic, and in order to be believable, RJPs should not offer an unqualified positive portrayal of the day-to-day challenges faced by teachers. We know from previous research that negative information lowers applicant attraction to an organisation (Bretz and Judge Citation1998); however, the right balance between realism and positive/negative content to maximise authenticity is not known. Further work is clearly needed to test the impact of message valence on both recruitment success and on retention rates post-recruitment.

Limitations

The study relies on a volunteer sample which may not represent students in STEM-related subjects generally, with no representation from large-enrolment STEM subjects such as Biology and Chemistry. In addition, our sample for the Study 1 and Study 2 were relatively small, restricting the analyses we could perform (e.g. latent variable analyses for Study 1). We therefore recommend that future studies replicating our findings should be carried out with larger samples sizes. Such studies with larger samples could then also use latent variable modelling, which we did not consider appropriate for the current study due to sample size constraints. The scores on the RJPs were not normally distributed, with almost all participants receiving a message of ‘excellent fit’ or ‘very good fit’. Future iterations of RJP interventions for teacher recruitment purposes could (a) manipulate the fit message to test which elements of the intervention (scenarios, fit message, feedback from experienced teachers) have an effect on career interest, (b) develop RJPs that elicit a more normally distributed scoring range, and (c) test the effects of RJPs on longer-term attitude and behavioural change. Some measurement issues need to be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First of all, the RJP intervention used an SJT format that is not well-suited to the use of conventional reliability metrics, with Catano, Brochu, and Lamerson (Citation2012) recommending test-retest for multi-dimensional SJT measures. In addition, the teachers’ self-efficacy measure was not originally designed to measure the confidence of university students who may never have seriously considered teaching as a career. However, there is a plausible argument based in self-efficacy theory that successful experiences (i.e. performance on an RJP task), coupled with verbal persuasion (real-time feedback from teachers), and vicarious experience (modelling in the form of a rationale from experienced teachers for appropriate responses) has the potential to raise confidence in teaching capabilities. We did not see that effect in this study, but the question remains open to further inquiry.

Conclusions and implications

This article contributes to our knowledge of teacher attraction and recruitment methods, with Study 1 (Is there an association between person-vocation fit and teaching self-efficacy, interest, and perceived match?) findings showing that a brief, scalable, online RJP intervention was associated with interest in a teaching career (supporting Hypothesis 2), but not teaching self-efficacy (Hypothesis 1) or perceived match between personal attributes and teaching attributes (Hypothesis 3). Study 2 addressed research question 2 (What do STEM students say about influences on career decision-making?) and showed that the RJP intervention increased interest and activated behavioural change, in contrast with existing social media campaigns. The findings provide insight into the potential role that person-vocation fit might play in teacher attraction and recruitment strategies in the future. In a time of teacher shortages, the article also highlights the need to study the effectiveness of current recruitment policies, and how relevant theory and research can contribute to improving the effectiveness of recruitment policies and methods.

Implications for practice and policy

Online RJPs provide a cost-effective and highly scalable approach to deliver a research-supported recruitment intervention. Consistent with person-environment fit and social cognitive theories (Bandura Citation1997; Uggerslev, Fassina, and Kraichy Citation2012) theories, providing tailored real-time feedback to potential applicants enhances organisational attractiveness (Hu et al., Citation2007). Recruitment strategies can be designed to feature multiple messages, with a person-vocation fit message delivered alongside messages centred around the personal and social utility of a teaching career. Recruitment websites could feature RJPs with personally tailored feedback designed to offer potential applicants a taste of the classroom, and preliminary feedback on the fit between their judgement and that of experienced professionals. However, the likelihood of STEM students accessing a teacher recruitment website may be low without incentives. One alternative might be to directly send recruitment messages to students in shortage subjects through university career advisory services, possibly with low-value financial incentives (for example, shopping voucher) provided for completion of the RJP. Such an approach, although incorporating some costs, would likely be far less expensive than the estimated £400-per-recruit spent on current advertising (Carr Citation2020).

The current study was set in England, where applicants to teacher training have been, until the COVID-19 crisis, in short supply, particularly in STEM subjects, modern foreign languages, and information technology. Shortages in teacher training applicants are not limited to the UK, with similar or higher (pre-COVID) levels in countries in Europe, Asia, and South America. In their recent cross-national report on teachers and school leaders, the OECD (Citation2019) urged countries to design effective recruitment campaigns that ‘praise the rewarding aspects’ (p. 49) of the profession such as intellectual and social fulfilment, job security, financial packages, and the opportunity to balance personal and professional life. We suggest that recruitment campaigns also explore the implementation of intervention approaches such as RJPs, that offer opportunities for enhanced personal reflection and consideration of fit with the profession.

Implications for research

More research is needed to understand how recruitment messages differentially influence decision-making of university students. Our results from Study 2 suggest that current recruitment advertising in the UK may not be effective, but the sample was small and self-selected. A more rigorous test of the effectiveness of advertising messages would be useful, especially using a longitudinal design that measures not only interest when entering a training programme (the anticipated outcome of personal and social utility messages), but also retention in the early years of the profession. We know from person-vocation fit theory that tailored and specific fit messages produce more positive applicant perceptions (Roberson, Collins, and Oreg Citation2005); however, it is possible that an RJP intervention will not increase the total number of applicants applying for ITE, but the hypothesis should be tested that RJPs increase the number of good applicants who are more likely to stay in the profession due to realistic expectations about career challenges and rewards. For example, some evidence of self-selection out of considering a teaching career was seen in the comments from participants in Study 2, e.g. I realise that I’m not patient enough (6 m) and The scenarios made me think about the struggles of teaching (4 f). Research that evaluates the longer-term impact of recruitment efforts would be highly valued: in short, evaluating only the change in number of applicants after an intervention is implemented (e.g. offering financial incentives) tells only half the story. What is needed is a research programme that evaluates the effects of recruitment messages on decisions at entry to a professional programme coupled with information about retention in a programme and into professional practice.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert M. Klassen

Robert M. Klassen is Professor and Chair of the Psychology in Education Research Centre at the University of York. His work focuses on teacher recruitment and development.

Helen Granger

Helen Granger is a former Maths teacher and currently a Lecturer in the Department of Education at the University of York.

Lisa Bardach

Lisa Bardach is an Assistant Professor at the Hector Research Institute of Education Sciences and Psychology in Germany. Her research focuses on the adaptive development and motivation of students and teachers.

Notes

1. No participant in the present study had a score of 12 or lower.

References

- Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman.

- Barrick, M. R., and L. Parks-Leduc. 2019. “Selection for Fit.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 6 (1): 13.1–13.23. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015028.

- Baur, J. E., M. R. Buckley, Z. Bagdasarov, and A. S. Dharmasiri. 2014. “A Historical Approach to Realistic Job Previews: An Exploration into Their Origins, Evolution, and Recommendations for the Future.” Journal of Management History 20 (2): 200–223. doi:10.1108/JMH-06-2012-0046.

- Bergman, M. E., F. Drasgow, M. A. Donovan, J. B. Henning, and S. E. Juraska. 2006. “Scoring Situational Judgment Tests: Once You Get the Data, Your Troubles Begin.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment 14 (3): 223–235. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00345.x.

- Borgerding, L. A. 2015. “Recruitment of Early STEM Majors into Possible Secondary Science Teaching Careers: The Role of Science Education Summer Internships.” International Journal of Environmental and Science Education 10: 247–270.

- Bretz, R. D., and T. A. Judge. 1998. “Realistic Job Previews: A Test of the Adverse Self-selection Hypothesis.” Journal of Applied Psychology 83 (2): 330–337. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.330.

- Carr, J. (2020). “Is the DfE’s Teaching Ad Spend Paying Off?” Schools Week. Retrieved from https://schoolsweek.co.uk/is-the-dfes-teaching-ad-spend-paying-off/

- Catano, V. M., A. Brochu, and C. D. Lamerson. 2012. “Assessing the Reliability of Situational Judgment Tests Used in High-stakes Situations.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment 20 (3): 334–346. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2389.2012.00604.x.

- Chuang, A., C. Shen, and T. A. Judge. 2016. “Development of a Multidimensional Instrument of Person-environment Fit: The Perceived Person-environment Fit Scale (PPEFS).” Applied Psychology: An International Review 65 (1): 66–98. doi:10.1111/apps.12036.

- Darling-Hammond, L., and M. E. Hyler. 2020. “Preparing Educators for the Time of COVID … and Beyond.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (4): 457–465. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1816961.

- De Cooman, R., S. De Gieter, R. Pepermans, S. Hermans, C. Du Bois, R. Caers, and M. Jegers. 2009. “Person–organization Fit: Testing Socialization and Attraction–selection–attrition Hypotheses.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 74 (1): 102–107. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.10.010.

- Department, F. 2020. Teacher recruitment and retention strategy. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/786856/DFE_Teacher_Retention_Strategy_Report.pdf

- Earnest, D. R., D. G. Allen, and R. S. Landis. 2011. “Mechanisms Linking Realistic Job Previews with Turnover: A Meta-analytic Path Analysis.” Personnel Psychology 64 (4): 865–897. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01230.x.

- Foster, D. 2019. “Initial Teacher Training in England.” House of Commons Briefing Paper 6710.

- Fullard, J. (2020). “Teacher Supply and Covid-19.” Education Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/teacher-supply-and-covid-19/

- Hackett, R. D., L. M. Lapierre, and P. A. Hausdorf. 2001. “Understanding the Links between Work Commitment Constructs.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 58 (3): 392–413. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1776.

- Heinz, M. 2015. “Why Choose Teaching? an International Review of Empirical Studies Exploring Student Teachers’ Career Motivations and Levels of Commitment to Teaching.” Educational Research and Evaluation 21 (3): 258–297. doi:10.1080/13803611.2015.1018278.

- Hu, Changya, Hsiao-Chiao Su, and Chang-I. Bonnie Chen. 2007. “The effect of person–organization fit feedback via recruitment web sites on applicant attraction.” Computers in Human Behavior 23, no. 5: 2509–2523.

- Kane, T. J., J. E. Rockoff, and D. O. Staiger. 2008. “What Does Certification Tell Us about Teacher Effectiveness? Evidence from New York City.” Economics of Education Review 27 (6): 615–631. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.05.005.

- Klassen, R., L. Bardach, J. Rushby, and T. L. Durksen. 2021. “Examining Teacher Recruitment Strategies in England.” Journal of Education for Teaching 47 (2): 163–185. doi:10.1080/02607476.2021.1876501.

- Klassen, R. M., L. E. Kim, J. Rushby, and L. Bardach. 2020. “Can We Improve How We Screen Applicants for Initial Teacher Education?” Teaching and Teacher Education 87: 102949. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.102949.

- Klassen, R. M., and T. L. Durksen. 2014. “Weekly Self-efficacy and Work Stress during the Final Teaching Practicum: A Mixed Methods Study.” Learning and Instruction 33: 158–169. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.05.003.

- Kunz, J., K. Hubbard, L. Beverly, M. Cloyd, and A. Bancroft. 2020. “What Motivates STEM Students to Try Teacher Recruiting Programs?” Kappa Delta Pi Record 56 (4): 154–159. doi:10.1080/00228958.2020.1813507.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Naylor, R., C. Jones, and P. Boateng. 2019. Strengthening the Education Workforce. New York: Education Commission.

- OECD. 2019. Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Paris: OECD.

- Player, D., P. Youngs, F. Perrone, and E. Grogan. 2017. “How Principal Leadership and Person-job Fit are Associated with Teacher Mobility and Attrition.” Teaching and Teacher Education 67: 330–339. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.017.

- Podolsky, A., T. Kini, L. Darling-Hammond, and J. Bishop. 2019. “Strategies for Attracting and Retaining Educators: What Does the Evidence Say?” Education Policy Analysis Archives 27: 38. doi:10.14507/epaa.27.3722.

- Roberson, Q. M., C. J. Collins, and S. Oreg. 2005. “The Effects of Recruitment Message Specificity on Applicant Attraction to Organizations.” Journal of Business and Psychology 19 (3): 319–339. doi:10.1007/s10869-004-2231-1.

- See, B. H., R. Morris, S. Gorard, and N. El Soufi. 2020. “What Works in Attracting and Retaining Teachers in Challenging Schools and Areas?” Oxford Review of Education 46 (6): 678–697. doi:10.1080/03054985.2020.1775566.

- See, B. H., and S. Gorard. 2019. “Why Don’t We Have Enough Teachers? A Reconsideration of the Available Evidence.” Research Papers in Education. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1568535.

- Tiffin, P. A., L. W. Paton, D. O’Mara, C. MacCann, J. Lang, and F. Lievens. 2020. “Situational Judgement Tests for Selection: Traditional Vs Construct-driven Approaches.” Medical Education 54 (2): 105–115. doi:10.1111/medu.14011.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., and A. Woolfolk Hoy. 2001. “Teacher Efficacy: Capturing an Elusive Construct.” Teaching and Teacher Education 17 (7): 783–805. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1.

- Uggerslev, K. L., N. E. Fassina, and D. Kraichy. 2012. “Recruiting through the Stages: A Meta-analytic Test of Predictors of Applicant Attraction at Different Stages of the Recruiting Process.” Personnel Psychology 65: 597–660.

- UNESCO (2016). The world needs almost 69 million new teachers to reach the 2030 education goals. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246124

- Vogel, R. M., & Feldman, D. C. 2009. “Integrating the levels of person-environment fit: The roles of vocational fit and group fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75, 68–81

- Watt, H. M., and P. W. Richardson. 2007. “Motivational Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice: Development and Validation of the FIT-Choice Scale.” The Journal of Experimental Education 75 (3): 167–202. doi:10.3200/JEXE.75.3.167-202.