ABSTRACT

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of an online short course in improving the knowledge and confidence of coaching and support staff when working with female athletes. A mixed-methods survey design was used, where participants completed surveys pre-, post-, and 6 months following an 8-week online course. Qualitative responses were analysed inductively using thematic analysis based on two pre-identified themes. Of the 92 participants who completed both pre- and post-course surveys, 72% (n = 66) were female and 67% (n = 62) were from team sports. Perceived knowledge and confidence improved following the course (p < 0.001) and were above pre-course values 6-months post (p < 0.001). A-priori theme Course Expectations generated two sub-themes: ’Empowering [me] to empower and support [them]’, and “Sharing knowledge and experiences”. A-priori theme Changes in Practice had subthemes of “Relaxing into it” and “Embedding support structures”. Participants indicated that they enjoyed learning from a variety of content experts as well as other participants in an online format. Future courses aimed at coaching/support staff should design and deliver accessible programs aligned with the learning preferences of these individuals. When delivering specific education regarding supporting female athletes, targeting and encouraging men to participate may be beneficial.

Introduction

In the last twenty years, there has been a substantial increase in female participation in sport at all levels, supported by increasing access to competitions, prize money, and regular income for female athletes (Sherry & Taylor, Citation2019). At the same time, there has been a growing interest in the specific physiology and psychology of female athletes, and how to optimise training and coaching strategies for this unique sporting cohort. However, the existing research on female athletes is limited in both its quality and practical applicability (Elliott-Sale et al., Citation2020), making it difficult for coaches and support staff to interpret key findings and implement them in their practice with female athletes. Indeed, research indicates that the topic which male coaches most want to improve their knowledge on is training and performance management (e.g., menstrual cycle monitoring) for their female athletes, followed by medical and dietary information (Clarke et al., Citation2021). While that study was specific to male coaches, coaches of all genders are considered to benefit from female athlete-specific education (Brown & Knight, Citation2022).

While athlete knowledge specific to the menstrual cycle appears to be relatively poor (Larsen et al., Citation2020), poor knowledge of the coach (actual, or as perceived by the athlete) can be a key barrier to whether athletes choose to communicate their menstrual-related concerns (Höök et al., Citation2021). For example, if an athlete perceives a coach to not be interested or thinks they will ignore their concerns, then an athlete is unlikely to voice this with their coach. As such, researchers have identified the need for more formal or structured education programs to educate coaches on how to support their female athletes, in both health and performance aspects (Forsyth et al., Citation2022; von Rosen et al., Citation2022). While formal coaching courses remain a reliable source of specific knowledge and skills, there still exists a preference from coaches for informal, self-directed learning, especially that which permits social interaction (Morley et al., Citation2022; Stoszkowski & Collins, Citation2016). As such, a balance of formal education and informal coaching interactions can enhance personal development and promote reflection (Mallett et al., Citation2009), while also providing up-to-date education with a foundation in empirical evidence (Stoszkowski & Collins, Citation2016).

With this in mind, a short educational course on supporting female athletes was developed, aiming to increase coaches’ knowledge in the areas of training, nutrition, and psychology, using both formal and informal learning methods. As this is one of the first short courses of its kind, it is important to assess its effectiveness in improving coaches’ knowledge, as well as evaluate the course structure and delivery. This information can then be used to improve the course for future iterations, and provide guidance for those aiming to develop further resources to address the identified needs of coaches and support staff in this area (Kellaghan et al., Citation2000). We have approached this study from a constructivist approach, with an understanding that knowledge is constructed based on one’s own experiences and reflections, with new information integrated within the context of one’s own existing knowledge, perceptions and understanding of the world. It is therefore important to capture the individual perspectives of participants to gain further insight into their experiences and take-aways from the course. Hence, the aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of an online course aimed at improving the knowledge of coaching and support staff working with female athletes, and to use participant feedback to create recommendations for future courses.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study used a mixed-methods survey design, where participants completed three instances of an online survey (pre-course, post-course, and 6 months post-course) hosted on QuestionPro (QuestionPro, Austin; USA). Questions required both quantitative (numeric) and qualitative (textual) responses related to their current coaching practices and knowledge (perceived and content-specific) of considerations when working with female athletes. Institutional ethics approval was obtained (approval number: HEC21266) and participants provided informed consent before they commenced the first survey. A mixed-methods approach was chosen to provide a more comprehensive understanding of participants’ experiences within the course.

Participants

The educational online short course was available to coaches and support staff currently working with female athletes in any sport and at any participation level. While the course was not limited by location, based on course advertising methods, over 90% of participants were based in Australia. Participants were recruited for the course on a voluntary basis following advertising through social media and promotion by various state and national sporting organisations. Following enrolment in the course, participants were recruited for this study via email, with 93 participants completing pre- and post-course surveys, and 37 of these individuals providing further survey responses 6 months post completion of the course.

Intervention

The online short course was eight weeks in duration and involved two phases. The first phase involved four modules of video content which were pre-recorded and delivered by content experts (academics and practitioners). Supplementary sessions with coaches and/or athletes (e.g., pre-recorded Q&A-style sessions) were also available within each module as well as a weekly discussion board. Modules delivered included: medical and dietary considerations, training and performance, communication and psychology, and, strength and conditioning and injury prevention (). These modules have been adapted from previous research that identified a recommended coach education framework for this topic (Clarke et al., Citation2021). Each module included approximately 1.5 hours of content. The second phase was a four-week self-guided applied practice block which encouraged participants to apply some of their newly acquired knowledge to their practice working with female athletes, with synchronous participant discussions around their goals, experiences, and reflections throughout the process.

Procedure

Participants were asked to complete three instances of an anonymous online survey that was distributed by email to enrolled short course participants. The first page of the survey contained an explanation of the study aims and information about confidentiality and anonymity, and a prompt to continue the survey and therefore provide consent for data collection. Participants were advised that because their answers were anonymous, they could not be withdrawn once submitted. For each survey, participants were asked to use a unique identifier code so that survey responses across time points could be matched.

The survey comprised of 3 sections and 28 items, which were slightly modified in terminology or layout for each iteration of the survey (pre-course, post-course, and 6 months post-course). Section one was designed to elicit answers about the current coaching practices of participants and where they obtain information regarding female athlete-specific practices (open-ended), and used likert scales (1–5) to capture participants levels of confidence and perceived knowledge in this area (i.e., “How do you rate your confidence in being able to appropriately manage and monitor female athletes for health and performance?”, and “How do you rate your current knowledge on training female athletes and the menstrual cycle?”). Section two assessed their content knowledge and was consistent across all three surveys, comprising a mix of short response and multiple-choice questions on the menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptives, derived from a similar questionnaire in Larsen et al. (Citation2020), scored as a value out of 10 (Supplementary file S1). Section three included open-ended questions for participants to identify what they hope to get out of the course (pre), whether it changed their practice (post, 6-months post), and general course feedback (post). The pre-course survey also contained an additional section to provide demographic information, including gender, sport, and coaching experience.

Analysis methods

Categorical data on participant demographics are presented as summed numbers. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to compare pre- and post-intervention measures of perceived knowledge, perceived confidence, as well as content knowledge from the 10 questions in Section two. A Kruskal-Wallis analysis was used to determine differences in the same measures for a sub-sample, comparing across three time points (pre, post, 6-months post) (n = 37), with a Wilcoxon signed-rank post hoc test to determine pairwise differences between time points. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Open-ended survey questions were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun et al., Citation2021). Specifically, the free-text responses were used to explore two a priori themes of “Course expectations” and “Changes in practice”, which were determined in alignment with the aims of the research. Data were initially coded deductively by AC, with statements sorted into the theme within which they best fit. It is worth emphasising that while direct questions about these themes were posed during the questionnaires (e.g., “What do you hope to get out of the course, beyond specific content knowledge?”), data were analysed as a full corpus and not linked to specific questions. That is, responses to “feedback” questions were sorted into both themes as deemed appropriate by the authors, as were all other open-ended questions. Next, the corpus was analysed inductively, with coding occurring within themes. The collation of these codes resulted in the creation of subthemes where appropriate. Throughout the analysis, coding and subtheme creation were performed by the first author (AC), with another author (AR) acting as an external auditor or “critical friend” for the process. Finally, overall course feedback was analysed deductively to provide guidance for future course delivery.

Results

Participant demographics

Two individuals did not provide demographic information. Of the 92 participants who completed both pre- and post- surveys, 72% (n = 66) were female and 67% (n = 62) were from a team sport (e.g., softball, soccer, netball, Australian football). The ratio of gender and sport involvement for the participants who responded to the survey were comparable to the total participant make-up of the short course. The majority (53%, n = 49) of participants were coaches, however, numerous other roles were also involved including strength and conditioning coaches/sport scientists (12%, n = 11), physiotherapists (10%, n = 9), and administrators/volunteers (9%, n = 8). Participants had been working with female athletes for 7 ± 7 years, with 28% (n = 26) having worked with female athletes for one year or less and 27% (n = 25) having worked with female athletes for 10 years or more. A total of 37 participants completed the survey 6-months following the completion of the course, who could be matched with previous responses at the post survey timepoint. Mean duration to complete each survey was 11–16 min.

There were four main areas from which participants reported obtaining their “female athlete specific” information: specialists (~12% respondents, e.g., sports doctor, sport/exercise scientist, physiotherapist), personal network (~40%, e.g., other coaches, partner/wife, daughters, colleagues, personal experience), published resources (~49%, e.g., by National sporting organisations or institutes, university degree, online courses, peer-reviewed research, webinars/podcasts), and popular media (~17%, e.g., newspaper, Google, social media).

Course evaluation

On a 1–10 Likert Scale, the median rating of the course was 9, with 100% of respondents stating they would recommend it to others. Over 80% (n = 75) believed the course has changed the way that they work with female athletes (unsure: 12%; no: 5%).

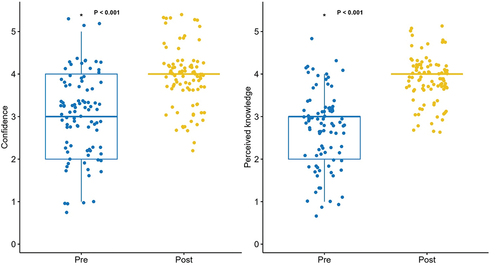

Perceived knowledge and confidence of participants improved following the course (, p < 0.001). Median perceived knowledge and confidence ratings both increased from 3/5 pre-course to 4/5 post-course. For those who had matched responses for 6-months post (n = 37), perceived knowledge and confidence were still above pre-course values (confidence = 4/5; perceived knowledge 4/5, median value at 6-months, p < 0.001).

Knowledge (assessed via section two of survey)

Content knowledge improved following the course (pre 5/10; post 6/10, median values, p = 0.004). Non-significant differences across the three timepoints were found for the subset of 37 participants (median values 5/10, 6/10, 6/10 for pre-, post-, and 6-months post, respectively).

Thematic analysis

Theme 1: Course expectations

Empowering [me] to empower and support [them].

A key driver for participants when enrolling in the course was to increase their confidence and capacity to better support female athletes, through increasing their knowledge of the menstrual cycle and its impacts on female athletic performance. Participants wanted to improve their ability to support, empower, and mentor female athletes, and were seeking education on the “creat[ion] of a developmental environment that supports the specific needs of our female athletes” and to “empower the athlete through understanding of how their body works”. Participants anticipated using the knowledge from the course to have more understanding of and empathy for the experiences of female athletes, beyond just training and performance. Some female participants identified the course as an opportunity to learn more about themselves, seeing the course as an opportunity “also to try and improve on my own performance as an athlete”. For male coaches, many indicated that they were seeking “strategies for having conversations with female athletes and their parents about the menstrual cycle, training, and overall health”, in addition to the content-specific information delivered within the course. They further expressed that they wanted to be able to “empathise” with their athletes about “the challenges involved with the hormonal cycle”.

Participants also expected the course to provide practical and applicable examples, resources, and implementation suggestions. Ahead of the course, a coach stated that they wanted “practical examples of things I can easily implement with my athletes”. Being able to directly apply information was important for participants, who indicated that they were wanting a “more comprehensive understanding of how to best plan for and support high level female athletes”. Post-course, coaches demonstrated an intention towards future knowledge seeking and implementation, requesting “access or direction to … further reading” and seeking resources such as infographics to use within their training environments.

Sharing knowledge and experiences

Participants expressed a strong desire to use this course to meet and learn from others working with female athletes. Networking with peers and interacting with industry professionals were common ideas, in particular the goal of “sharing different experiences with others”. In addition to establishing new networks, participants indicated that they planned to share the information gained from the course with their existing organisational networks, including coaches, athletes, parents, and stakeholders.

Theme 2: Changes in practice

Relaxing into it

Participants described having a greater awareness of factors relevant to female athletes, which had made them more confident in having conversations with athletes following the course. One participant reported that the course “made me more confident that my approach was right, and to relax into it a bit more”. This confidence has made respondents “more likely to engage in dialogue with players” and feel “far more collaborative, planned … empathetic and structured with greater flexibility”. Participants indicated that they have created more open communication around the menstrual cycle. Participants are now “more likely to engage in dialogue with players” and are “more confident to ask questions [of] athletes [about] how they are feeling that day”. Another component of participants’ increased comfort may be in that they are “thinking more about the language used in the training environment”. Participants noted that they are “being more mindful” of language, particularly in relation to food and bodies, and are paying more attention to word choices made by and around athletes, coaches, parents and colleagues.

Embedding support structures

The course supported participants to embed information and education within their training environments. Participants described education they have provided to various stakeholders since completing the course. They spoke about having the knowledge to “point [athletes, parents, coaches] in the right direction for continued support”. Several participants were able to implement or better integrate menstrual cycle tracking within their existing athlete monitoring systems and commented that there has been “more consideration and planning given for our female/young athletes”.

Course feedback

Participants provided feedback on both the subject content and delivery format. They appreciated the “variety and quality of presenters” across a range of subject matters relating to female athletes. Participants also enjoyed the blend of research and applied practice presentations and that “speakers could offer advice … from their experience (and not just rely on research findings)”. The online environment was considered accessible, however, challenges with balancing the timing and structure of synchronous sessions were apparent. Timing within the competitive season or access to athletes also limited some participants in relation to the applied practice block. Many participants enjoyed the synchronous sessions, highlighting that the “peer interaction was the most valuable thing” with requests for more synchronous or face-to-face opportunities to connect with the other participants to be made available. Participants expressed a desire for more “take-home” resources to have been made available, requesting “infographics or resources that could be sent out to organisations or athletes”. They also demonstrated a desire for the opportunity to “deep dive” on more topics, stating that further reading “would have helped deepen my understanding”.

Discussion

The current study investigated the effectiveness of an online short course designed to improve the knowledge of coaching and support staff on female athletes. Overall, the eight week online short course improved the perceived knowledge and confidence as well as observed knowledge of participants. Further, from the sub-set of participants who also completed the follow-up survey six months following the completion of the course, this perceived confidence and knowledge was retained above pre-course levels. Combined, this suggests the short course was successful in educating coaching and support staff of female athletes and improving their confidence in delivering this knowledge where applicable. Further assessment of the open-ended responses also provides greater detail regarding what and how coaches and support staff wish to learn and engage in this topic around supporting female athletes. In particular, the strength of conducting the course in an online environment was emphasised, but the desire and preference for peer connections is also an important consideration.

The development of the short course deliberately incorporated both nonformal (content modules) and informal (applied practice block; peer interactions) learning opportunities. Nonformal and informal education are known to be effective methods of coach development, and coaches demonstrate a clear preference for informal-type learning (Nelson et al., Citation2006; Van Woezik et al., Citation2022). This preference can be observed in participants’ responses to what they hoped to gain from the course in terms of peer networking and plans to further develop their own network. Based on course feedback, it is also recommended that any future coach education course provide some element of shared discussion between participants, and/or create a community of practice during or following the completion of the course. Specific to the content delivered in this course, where there is a substantial gap in the literature available (Elliott-Sale et al., Citation2020) to provide best practice guidelines for training and working with female athletes, this community of practice may assist in bridging the gap while high-quality research in this field is still lacking.

Time and cost are reported barriers to more formal coach education, and there is also a preference for more unstructured learning environments (Van Woezik et al., Citation2022). As the current short course was conducted in an online environment, participants were able to complete the content modules at a time and place that suited them, which was generally agreeable for most participants. Similarly, the reason that people were unable to participate in the synchronous sessions was often due to a clash in scheduling that limited their accessibility to take part. While the accessibility of the asynchronous online environment does make it easier for coaches to acquire this information when it suits them, it can mean that they miss out on interacting with other coaches, and so limits the depth and consolidation of their learning. As such, it is encouraged that when online learning environments are created, sufficient options to connect with other participants (virtually or otherwise) are given. Future education programs could also evaluate the potential of a hybrid model that involves both online and in-person learning environments.

Over time, while still significantly better than pre-course, participants did lose some of their confidence and perceived knowledge six months following the completion of the course. This is similar to previous education courses in the area of concussion (Conaghan et al. 2021). Potentially, their daily environment (e.g., their role, proximity to athletes, ability to initiate change, or experiences/interactions they’ve had) may influence whether these elements can be maintained for longer periods of time (i.e., “use it or lose it”). Even within the initial six months post-course, a number of participants did identify that they had been unable to put into practice any elements from this course (due to time of season, or role they were currently in), impeding their ability to apply and consolidate their learning. Indeed, one limitation of the course was the difficulty in being able to accurately capture whether any specific change in practice occurred as a result of the course, despite improvements in perceived confidence and knowledge. Similarly, due to the timing of surveys, we were unable to determine whether the change in knowledge and confidence during the initial 8-week course was a result of the course content or more related to the synchronous discussions. Further evaluation of the breakdown of course content would help to identify the most effective methods to change practice in this group. Further, the establishment of an ongoing community of practice may help to maintain their confidence and continue to share new knowledge in this area for participants or other coaches, e.g., as a mentor (McQuade & Nash, Citation2015). It is important to recognise, particularly in this growing area of research around appropriate support for the female athlete, that knowledge in this area is not static. In this way, this online short course may act as a catalyst for participants to actively seek new and relevant information related to female athletes, such as engaging with communities of practice or subsequent refresher courses. This is supported by the participants’ request for further resources, demonstrating their desire for further information.

Previous reports have highlighted that there are more males than females working in coaching and support roles within women’s sport globally (Eime et al., Citation2021; Leabeater et al., Citation2023; Norman, Citation2014; Roberts et al., Citation2022). Thus, it could be expected that more men might participate in this course in order to develop or upskill their knowledge around female athletes. However, there was a greater uptake of the course from female participants (72%) rather than male (28%). Potentially, women in coaching/support roles may be more aware that they are lacking knowledge in this area and actively seek out this information in order to adequately meet the needs of their athletes. Male coaches, on the other hand, may adopt a “one size fits all” coaching practice that is not adapted to gender differences (Norman, Citation2016), and in turn, may be less likely to seek out gender-specific coaching education. With this in mind, targeted engagement with male coaching and support staff is required to promote the benefits of learning about female athlete-specific considerations for their coaching practice. This may require a more nuanced approach to encourage male practitioners of female athletes/teams to complete similar education programs in the future.

Overall, the eight week online short course was found to improve the perceived knowledge and confidence of coaching and support staff who work with female athletes. Participants enjoyed the breadth of topics covered, the range of experts and coach/athlete voices, and the accessible nature of the online format of the course. It is important to remember though that improving knowledge does not always translate to changing applied practice and coaching behaviour. While improving the confidence of coaches hopefully assists in this move to adopting new practices, evaluating educational programs specific to their ability to change practice would be important moving forward. Future educational courses aimed at coaching and support staff are encouraged to apply our learnings to design and deliver programs in a way that is accessible and aligned with the learning styles and preferences of these individuals. When delivering specific education regarding supporting female athletes, directly targeting and encouraging men to participate may also be beneficial.

Supplementary File 1.pdf

Download PDF (128.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2024.2360839

Additional information

Funding

References

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2021). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

- Brown, N., & Knight, C. J. (2022). Understanding female coaches’ and practitioners’ experience and support provision in relation to the menstrual cycle. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 17(2), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541211058579

- Clarke, A., Govus, A., & Donaldson, A. (2021). What male coaches want to know about the menstrual cycle in women’s team sports: Performance, health, and communication. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 16(3), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954121989237

- Eime, R., Charity, M., Foley, B. C., Fowlie, J., & Reece, L. J. (2021). Gender inclusive sporting environments: The proportion of women in non-player roles over recent years. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 13(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-021-00290-4

- Elliott-Sale, K. J., McNulty, K. L., Ansdell, P., Goodall, S., Hicks, K. M., Thomas, K., Swinton, P. A., & Dolan, E. (2020). The effects of oral contraceptives on exercise performance in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(10), 1785–1812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01317-5

- Forsyth, J. J., Sams, L., Blackett, A. D., Ellis, N., & Abouna, M. S. (2022). Menstrual cycle, hormonal contraception and pregnancy in women’s football: Perceptions of players, coaches and managers. Sport in Society, 26(7), 1280–1295. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2022.2125385

- Höök, M., Bergström, M., Sæther, S. A., & McGawley, K. (2021). Do elite sport first, get your period back later. Are barriers to communication hindering female athletes? International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 18(22), 12075.

- Kellaghan, T., Madaus, G. F., & Stufflebeam, D. L. (2000). Evaluation models: Viewpoints on educational and human services evaluation (2nd ed.). Springer

- Larsen, B., Morris, K., Quinn, K., Osborne, M., & Minahan, C. (2020). Practice does not make perfect: A brief view of athletes’ knowledge on the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptives. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(8), 690–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.02.003

- Leabeater, A., Clarke, A., Roberts, A., & MacMahon, C. (2023). The field includes the office: The six pillars of women in sport. Sport in Society, 26(9), 1602–1610. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2023.2170228

- Mallett, C. J., Trudel, P., Lyle, J., & Rynne, S. B. (2009). Formal vs informal coach education. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 4(3), 325–364. https://doi.org/10.1260/174795409789623883

- McQuade, S., & Nash, C. (2015). The role of the coach developer in supporting and guiding coach learning. International Sport Coaching Journal, 2(3), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2015-0059

- Morley, D., Turner, G., Roberts, A., Lidums, M., Melvin, I., Nicholson, M., & Donaldson, A. (2022). What do coaches want to know about identifying, developing, supporting and progressing athletes through a national performance pathway? Sports Coaching Review, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2022.2142409

- Nelson, L. J., Cushion, C. J., & Potrac, P. (2006). Formal, nonformal and informal coach learning: A holistic conceptualisation. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 1(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1260/174795406778604627

- Norman, L. (2014). Gender and coaching report card: London 2012 Olympics. Paper presented at the 6th IWG World Conference on Women and Sport, Helsinki.

- Norman, L. (2016). Is there a need for coaches to Be more gender responsive? A review of the evidence. International Sport Coaching Journal, 3(2), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2016-0032

- Roberts, A., Clarke, A., Fox-Harding, C., Askew, G., MacMahon, C., & Nimphius, S. (2022). She’ll Be ‘right… but are they? An Australian perspective on women in high performance sport coaching. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.848735

- Sherry, E., & Taylor, C. (2019). Professional women’s sport in Australia. In N. Lough, & A. N. Geurin (eds.), Routledge handbook of the business of women’s sport (pp. 124–133). Routledge.

- Stoszkowski, J., & Collins, D. (2016). Sources, topics and use of knowledge by coaches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(9), 794–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2015.1072279

- Van Woezik, R. A., McLaren, C. D., Côté, J., Erickson, K., Law, B., Lafrance Horning, D., Callary, B., & Bruner, M. W. (2022). Real versus ideal: Understanding how coaches gain knowledge. International Sport Coaching Journal, 9(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2021-0010

- von Rosen, P., Ekenros, L., Solli, G. S., Sandbakk, Ø., Holmberg, H. C., Hirschberg, A. L., & Fridén, C. (2022). Offered support and knowledge about the menstrual cycle in the athletic community: A cross-sectional study of 1086 female athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911932