ABSTRACT

This study tested multiple constructs of authenticity (i.e. true-to-ideal, true-to-fact, and true-to-self) and examined the structural relationships among authenticity perception, perceived value, positive emotions, and revisit intentions. Gilmore and Pine’s authenticity model suggests that authenticity is strongly related to customers’ trust. Customers tend to perceive chain restaurants as more credible than independent restaurants. Thus, this model contradicts the widespread argument that independent organizations reflect authenticity. Further investigation is needed to verify the relationship between restaurant ownership type and authenticity perception. Data were collected from 491 Chinese ethnic diners and analyzed using a structural modeling analysis. All three authenticity dimensions significantly influence overall authenticity perceptions. Furthermore, individuals’ authenticity perceptions affect revisit intentions through perceived value and positive emotions. Additionally, the ownership type of ethnic restaurants moderates the effects of the three authenticity dimensions on overall authentic dining experiences. Thus, ethnic restaurateurs should emphasize different authenticity dimensions of uniquely positioned restaurants.

摘要

本文旨在测试真实性的多维度(即:理想真实、事实真实和自我真实),并检验真实性感知、感知价值、积极情绪和重访意向之间的结构关系。 Gilmore 和 Pine 的真实性模型显示,真实性与顾客的信任密切相关,而顾客认为连锁餐厅比独立餐厅更可信。因此,现有模型与普遍认为的独立餐厅真实性高的论点相矛盾。在此基础上,餐厅所有权类型与真实性感知之间的关系需要进一步研究。本文调查了 491 名近期在韩国餐厅用餐的中国消费者,并使用结构方程模型进行分析。结果显示:三个真实性维度均影响整体真实性感知,个人的真实性感知通过感知价值和积极情绪影响重访意向。此外,韩国餐厅的所有权类型调节三个真实性维度对整体真实用餐体验的影响。因此,餐饮经营者应该根据不同真实性维度进行餐厅的市场定位。

1. Introduction

Conveying authenticity represents a business challenge as consumers are increasingly interested in purchasing authentic items from genuine sellers rather than false items from disingenuous sellers (Gilmore & Pine, Citation2007). This managerial challenge is manifested in ethnic restaurants, where customers consume a unique culture and/or cultural products; therefore, authenticity is critically important for appealing to target customers (Kim & Song, Citation2020). Researchers have defined authenticity as the degree to which businesses’ attributes (e.g. product category, marketing communication, and motivations) are perceived to be true and genuine (Moulard et al., Citation2021). Thus, to effectively convey a feeling of authenticity, authenticity examinations should consider various elements of an ethnic restaurant. However, the majority of the extant authenticity literature is limited to focusing on increasing customers’ perceptions of the other, such as perceiving the other to be unique (Le et al., Citation2019). Unfortunately, such a limited focus cannot cover all aspects of authenticity perception. An example of this problem appears in the controversy regarding the effect of restaurant ownership type on the delivery of authentic dining experiences.

The extant literature categorizes restaurant ownership type as independent or chain. Independent restaurants are independently owned and small (Lee et al., Citation2016) and often have a unique appearance and menu (Harris et al., Citation2014). In contrast, chain restaurants are multiunit enterprises owned or operated by a single company (Kim & Song, Citation2020). A large body of literature asserts that customers perceive independent restaurants as more highly authentic than their chain counterparts (Kovács et al., Citation2014; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006). This line of thought can be supported by the characteristics of authenticity that emphasize the uniqueness and/or scarcity of a product (Robinson & Clifford, Citation2012). For example, Robinson and Clifford (Citation2012) noted that small businesses often utilize simple and natural production methods, leading individuals to consider independent businesses genuine or unique. Similarly, Steiner and Reisinger (Citation2006) noted that the standardization of products destroys the sense of authenticity; therefore, chain organizations are often perceived as inauthentic. However, other researchers have argued that chain restaurants can also provide highly authentic dining experiences (De Vries & Go, Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2020). For example, Kim et al. (Citation2020) found that chain restaurants deliver stronger authentic feelings than independent restaurants.

The above inconsistency suggests that there are determinants of authenticity perceptions other than uniqueness and/or scarcity. Thus, the restaurant service literature must identify the multiple dimensions of authentic dining experiences and provide a comprehensive conceptual framework of authentic dining experiences. Accordingly, Le et al. (Citation2019) called for research to identify the various authenticity dimensions in dining experiences and test these dimensions using empirical data. Recently, Moulard et al. (Citation2021) proposed a three-dimensional authenticity model that included the constructs of true-to-ideal, true-to-self, and true-to-fact. However, to the best of our knowledge, no empirical studies have tested this model.

Another gap in the authenticity literature is the lack of studies examining the mediating factors explaining the mechanism by which ethnic diners’ authenticity perceptions affect their dining behaviors. The extant authenticity literature has mainly examined the direct influence of authenticity on dining intention (e.g. Kim & Baker, Citation2017; Wang & Mattila, Citation2015; Youn & Kim, Citation2017). Thus, researchers have called for more recognition of mediating factors in authenticity research. For example, Kim et al. (Citation2020) urged future research to identify potential mechanisms explaining the effects of authenticity perception on consumer behavior.

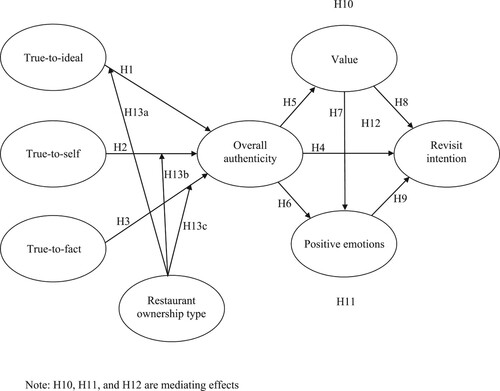

Therefore, this study focuses on the following three research questions: (1) How do ethnic diners develop authenticity perceptions? (2) Do ethnic diners develop authenticity differently in restaurants with different ownership types? (3) How do ethnic diners’ authenticity perceptions influence their consumer behaviors? To answer these research questions, this study employed Moulard et al.’s (Citation2021) multiple-dimensional authenticity model and examined the influence of various authenticity dimensions on overall perceived authenticity (i.e. formative constructs). Furthermore, this study utilized S-O-R theory as a foundation for developing the research model. S-O-R theory suggests that stimuli elicit emotional responses, which, in turn, determine consumer behaviors, such as revisit intention (Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974). This theory mainly focuses on individuals’ emotional responses to stimuli; however, researchers have argued that individuals develop both cognitive and emotional responses to exposed stimuli (Kim et al., Citation2017; Kim & Moon, Citation2009). Thus, this study extends the authentic dining experience model by integrating an extended S-O-R theory to explain the mechanism by which individuals’ authenticity perceptions (S) affect their revisit intentions (R) through perceived value (O1) and positive emotions (O2). Furthermore, this study examines ethnic diners’ perceived authenticity of both chain and independent ethnic restaurants to clarify the inconsistency in the literature. depicts the theoretical framework developed for the current study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Authentic dining experience dimensions

Researchers have claimed that customers might seek the following three different types of authenticity: objective, constructive, and existential (Wang, Citation1999). Objective authenticity depends on the objective information of an object (Grayson & Martinec, Citation2004). The second type, constructive authenticity, involves individuals’ construction of authenticity based on their social beliefs, expectations, preferences and perceptions (Peterson, Citation2005). Existential authenticity is related not to proving the attributes of objects but to achieving a personal and intersubjective state of the authentic self (Wang, Citation1999).

Although these three types of authenticity can to some extent be applied to the context of ethnic restaurants, researchers have emphasized constructive viewpoints in studying customers’ perceived authenticity (Kim & Jang, Citation2016). Scholars have argued that regardless of whether an object is authentic, customers can have authentic experiences based on the image they create of the object (Grayson & Martinec, Citation2004). However, the extant hospitality literature lacks a discussion of the various attributes that form authentic dining experiences. Specifically, previous authentic food studies mainly focused on the role of unique or unfamiliar characteristics in authenticity (Lu et al., Citation2015). For example, researchers have utilized unfamiliar food names and ingredients (Kim et al., Citation2017) and unfamiliar tastes (Kim & Jang, Citation2016) as authenticity cues and examined their influences on customers’ authenticity perceptions.

However, researchers have argued that multiple authenticity dimensions constitute authentic dining experiences (Kim, Citation2021; Le et al., Citation2021). Thus, a comprehensive study exploring the dimensions of authentic experiences and examining their comparative influences on overall authenticity perceptions and consumer behavior is needed. As an initial effort in this regard, Moulard et al. (Citation2021) recently proposed a conceptual model involving three types of authenticity. Therefore, this study utilizes Moulard et al.’s authenticity model to investigate each authenticity dimension’s influence on ethnic diners’ overall perceived authenticity and revisit intentions. The following subsections discuss the authenticity dimensions examined in the current study.

2.1.1. True-to-ideal

Moulard et al. (Citation2021) defined true-to-ideal authenticity as the extent to which customers perceive that the attributes of a product or service correspond to socially determined standards. In line with this definition, researchers have claimed that authentic products or services conform to customers’ images, beliefs, and expectations of a product or service (Grayson & Martinec, Citation2004; Peterson, Citation2005). Accordingly, customers are likely to develop a true-to-ideal authenticity judgment if a business represents the product or service category exemplar (i.e. ideals or common standards) established in a society. For example, an ethnic Korean restaurant decorated with cultural items serving Korean dishes that correspond to ethnic diners’ ideals of Korean food and the image of Korea could provide the impression that customers are visiting a little Korea (Kim & Jang, Citation2016).

2.1.2. True-to-fact

True-to-fact authenticity mainly focuses on a comparison between marketing communication content and the actual quality of products/brands (Moulard et al., Citation2021). Currently, customers can assess the true-to-fact authenticity of a brand/corporation based on brand marketing and communication campaigns, even without a real consumption experience (DiPietro & Levitt, Citation2019). For example, an ethnic restaurant may publicly claim restaurant authenticity, and customers might rely on the claim to judge whether the restaurant is credible or honest (Kim & Song, Citation2020). Additionally, customers can determine whether a brand/corporation is honest or credible based on real experiences with the brand/corporation (Kim, Citation2021). If the real products are the same as the advertised products, customers are more likely to develop true-to-fact authenticity perceptions (Kim, Citation2021). Using Korean restaurants in China as an example, if the real experiences are the same as the advertised restaurant experiences, customers are more likely to believe that the restaurant is honest and reliable; thus, customers are likely to develop true-to-fact authenticity perceptions toward the restaurant.

2.1.3. True-to-self

True-to-self-authenticity occurs when the brand/corporation is committed to its intrinsic values rather than being externally driven only by commercial values or profits (Moulard et al., Citation2021). Focusing on intrinsic motivations to conduct business, a brand/corporation follows its true self (Hicks et al., Citation2019), values and principles (Kim et al., Citation2021) and is passionate about and committed to conducting business (Lehman et al., Citation2019). Using the restaurant context as an example, high true-to-self-authenticity is related to a restaurant’s dedication to improving a unique dietary and culinary culture (Kim, Citation2021). In contrast, a restaurant with low true-to-self-authenticity is extrinsically motivated (e.g. profits and brand names) and, thus, is overly commercialized (Kim, Citation2021).

2.2. Guiding theoretical framework

The current research model is grounded in S-O-R theory. This theory suggests that environmental stimuli provoke individuals’ emotions, which, in turn, affect their behavior regardless of whether they approach or avoid the environment (Mehrabian & Russell, Citation1974). Thus, utilizing S-O-R theory, hospitality researchers have examined the influence of various environmental factors on individuals’ future behavioral intentions through the mechanism of emotions (Kim & Moon, Citation2009). However, individuals respond to not only environmental stimuli but also other types of stimuli, including authenticity (Liu et al., Citation2018; Rodriguez-Lopez et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, researchers have noted that stimuli can cause both emotional and cognitive reactions, such as attitude (Arora et al., Citation2020) and perceived quality (Kim & Moon, Citation2009). Thus, to examine the effect of various authenticity dimensions on customer responses, this study utilizes S-O-R theory as a theoretical background. Accordingly, this study posits that individuals’ authenticity perceptions are stimuli, the cognitive (i.e. perceived value) and emotional (i.e. positive emotions) states caused by stimuli are organisms and customers’ revisit intentions are a behavioral response.

Furthermore, Gilmore and Pine (Citation2007) discussed the following two dimensions to classify (in)authentic business offerings: 1. being true to oneself, which is a self-reflexive criterion, and 2. being true to others, which is a relational criterion. This discussion shows that the authenticity judgment is strongly related to producers’ trust and information disclosures to their markets. Thus, chain restaurants that stay true to their essential identity across their service offerings are more likely to be recognized and preferred by the market (Keiningham, He, Hillebrand, Jang, Suess, & Wu, Citation2019). Therefore, as chain restaurants have higher awareness in the market and are more exposed to public scrutiny than independent restaurants, customers generally perceive chain restaurants to be more credible (Kim & Song, Citation2020). Additionally, as the information provided by chain restaurants is more verifiable, customers are likely to trust the public announcements/advertisements made by chain restaurants. Accordingly, some researchers have noted that chain restaurants can deliver high authentic feelings to their customers (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2020).

However, others argue that authenticity is also related to the uniqueness and/or scarcity of a product (Robinson & Clifford, Citation2012). Thus, chain restaurants adopting standardization and mass production methods have limited ability to provide authentic dining experiences (Kovács et al., Citation2014; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006). Thus, by utilizing a multiple-dimensional authenticity model, this study examines the moderating effect of the type of restaurant ownership on authenticity perceptions.

2.3. Hypothesis development

Utilizing Moulard et al.’s (2021) authenticity model, this study proposes that authenticity is a three-dimensional construct and that overall authenticity serves as a stimulus to influence ethnic diners’ response (i.e. revisit intention) through both cognitive (i.e. value) and emotional (i.e. positive emotions) mechanisms. Furthermore, this study assumes that the relationship between authenticity dimensions and overall authenticity varies depending on the restaurant ownership type. The following sections present a discussion leading to the development of the research hypotheses.

2.3.1. The effect of authenticity dimensions on overall perceived authenticity

Scholars have indicated that various authenticity dimensions contribute to customers’ overall authenticity perceptions (Chen et al., Citation2020; Kim, Citation2021). For example, when an ethnic restaurant’s offerings and service environment are congruent with customers’ expectations and knowledge of the culture or food of ethnic origin (i.e. true-to-ideal), customers are likely to form a high overall authenticity perception toward the restaurant (Kim & Jang, Citation2016). Accordingly, De Vries and Go (Citation2017) argued that restaurants should carefully design both tangible and intangible elements to conform to the authentic image that customers have.

Furthermore, customers evaluate restaurants as authentic when they perceive them to deliver products and services that are consistent with their promises (i.e. true-to-fact) (Kim, Citation2021). Similarly, Taheri et al. (Citation2020) identified that visitors’ perceived trust plays an important role in determining authenticity perceptions toward cultural heritage sites. Corroborating this finding, researchers in brand management have noted that credibility and integrity are important elements of customers’ perceived authenticity (Moulard et al., Citation2016).

Additionally, researchers have emphasized true-to-self as an important antecedent of authenticity perceptions (De Vries & Go, Citation2017; Gilmore & Pine, Citation2007). For example, in discussing strategies to deliver authentic experiences, Gilmore and Pine (Citation2007) emphasized that businesses and their product offerings should be true to themselves. Grounded in self-determination theory, researchers have suggested that intrinsically motivated behavior that involves dedication and passion is essential for authenticity (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Thus, when a restaurant follows its true passion and dedication in conducting its business (i.e. true-to-self), customers are likely to form positive overall authenticity perceptions (Lehman et al., Citation2019). In line with the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. The authenticity dimension of true-to-ideal is positively associated with overall.

authenticity perception.

H2. The authenticity dimension of true-to-self is positively associated with overall.

authenticity perception.

H3. The authenticity dimension of true-to-fact is positively associated with overall.

authenticity perception.

2.3.2. The effect of perceived authenticity on revisit intention

Previous research has reported that customers’ perceived authenticity positively contributes to their behavioral intentions (Song & Kim, Citation2021). For example, customers prefer to visit (revisit) businesses with a high level of authenticity over businesses with a low level of authenticity (Youn & Kim, Citation2017). This positive relationship has been confirmed in multiple contexts, such as tourism destinations (Lin & Liu, Citation2018), restaurant businesses (Youn & Kim, Citation2017), food purchases (Latiff et al., Citation2020), and wine consumption (Pelet et al., Citation2020). In line with previous research findings, it is hypothesized that Chinese customers are likely to visit (revisit) a restaurant if they view the restaurant as having a high level of overall authenticity. Specifically, we develop the following hypothesis:

H4. Overall authenticity perception is positively associated with revisit intention.

2.3.3. The effect of perceived authenticity on value perception

erceived value is an assessment of the gap between what is provided by a business and what is received by its customers (Hernandez-Fernandez & Lewis, Citation2019). The extant literature has reported that customers’ authenticity perceptions toward purchased products/services enhance the value of transactions. For example, focusing on the value ratings given on online review platforms, Kovács et al. (Citation2014) found that customers gave authentic restaurants higher value ratings than less authentic restaurants. Furthermore, researchers have revealed that customers are willing to pay a premium price for brands/restaurants with a high level of authenticity (Hernandez-Fernandez & Lewis, Citation2019; O’Connor et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, we hypothesized that Chinese customers view a Korean restaurant as worth the money if it offers a highly authentic experience. Specifically, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5. Overall authenticity perception is positively associated with customers’ perceived value.

2.3.4. The effect of perceived authenticity on positive emotions

The authenticity literature has consistently reported that customers’ perceived authenticity arouses positive emotions (Kim et al., Citation2020). For example, Jang and Ha (Citation2015) found that ethnic diners’ perceived authenticity significantly increases their positive emotions. Furthermore, Kim et al. (Citation2017) discussed authentic dining experience cues, such as unique food names and ingredients, that arouse ethnic diners’ positive emotions. In a traditional restaurant context, Kim et al. (Citation2020) also identified that Chinese customers who develop highly authentic perceptions are more likely to have positive emotions toward restaurants. Based on these previous findings, we develop the following hypothesis:

H6. Overall authenticity perceptions are positively associated with customers’ positive emotions.

2.3.5. The effect of customer value on positive emotions

Researchers have reported that individuals’ cognitive evaluations are necessary for eliciting emotional responses (i.e. cognitive appraisal theory, Lazarus, Citation1991). For example, Lazarus (Citation1991) suggested that individuals’ subjective evaluations and judgments of an event or object generate certain emotional states. Accordingly, this study posits that customers’ perceived value is an antecedent of emotions. The extant literature has reported the influence of perceived value on positive emotions (Song & Qu, Citation2017; Zielke, Citation2014). For example, Zielke (Citation2014) identified that customers’ value perceptions positively influence enjoyment. Additionally, Song and Qu (Citation2017) found that ethnic diners with high value perceptions of dining experiences are likely to feel positive emotions. In line with the discussion above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7. Customers’ perceived value is positively associated with positive emotions.

2.3.6. The effect of customers’ perceived value on their revisit intentions

Previous studies have consistently acknowledged the significant role of perceived value in driving consumer behavior (Amirtha & Sivakumar, Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2021). More specifically, the higher the value that customers perceive a restaurant to have, the greater the likelihood that they will revisit the restaurant (Chen et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Kuo et al. (Citation2009) confirmed that customers’ perceived value positively influences their postpurchase intentions to patronize a service. In line with these previous findings, it is expected that customers are likely to form a higher revisit intention if they perceive the restaurant to be of good value. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H8. Customers’ perceived value is positively associated with revisit intentions.

2.3.7. The effect of positive emotions on revisit intention

The extant literature has consistently reported the significant influence of positive emotions on consumer behavior (Vitezić & Perić, Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2021). For example, focusing on Chinese ethnic food, Kim et al. (Citation2017) found that customers’ positive emotions aroused from exposure to authentic experience cues significantly increased their purchase intentions. Furthermore, in a traditional restaurant context, Kim (Citation2021) and Kim et al. (Citation2020) found that customers’ perceived authenticity impacted their behavioral intentions through positive emotions. Consistent with these previous findings, we propose the following hypothesis:

H9. Positive emotions are positively associated with revisit intention.

2.3.8. The mediating effects of customer value and positive emotions

As discussed above, the extant literature indicates that customers’ authenticity perceptions influence consumer behavior not only directly but also indirectly through customers’ perceived value (Hernandez-Fernandez & Lewis, Citation2019; O’Connor et al., Citation2017) and positive emotions (Kim, Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2020). However, in the extant authenticity literature, limited effort has been devoted to understanding the mediating factors explaining the mechanism by which customers’ authenticity perceptions influence their consumer behaviors. To fill this gap, the current study proposes a more comprehensive authentic dining experience model by positing customers’ perceived value and positive emotions as mediators in the relationship between overall authenticity perception and revisit intention.

The mediating roles of customer value and emotions in the relationship between authenticity perception and revisit intention correspond to S-O-R theory. This theory suggests that a stimulus triggers individuals’ emotional responses, which, in turn, determine their behaviors. Subsequent research has extended the original S-O-R theory by examining various types of stimuli and individuals’ cognitive responses. Accordingly, this study proposes overall authenticity perceptions as the stimuli, perceived value and positive emotions as organisms, and customers’ revisit intentions as the behavioral response. Specifically, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H10. Customers’ perceived value mediates the relationship between overall authenticity perception and revisit intention.

H11. Positive emotions mediate the relationship between overall authenticity perception and revisit intention.

H12. Both customers’ perceived value and positive emotions mediate the relationship between overall authenticity perception and revisit intention.

2.3.9. The moderating effect of restaurant ownership type on authenticity perceptions

There are two major restaurant ownership types as follows: independent and chain restaurants (Kim et al., Citation2020). On the one hand, independent restaurants are single units with a comparatively small scale (Lee et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, chain restaurants are multiunit enterprises owned or operated by a single company (Harris et al., Citation2014). Controversy exists in the literature regarding the relationship between restaurant ownership type and authenticity perceptions. For example, some researchers indicate that customers perceive chain restaurants as inauthentic (Kovács et al., Citation2014; Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006), whereas others argue that chain restaurants convey stronger authentic experiences than their independent counterparts (De Vries & Go, Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2020).

This controversy could result from researchers’ limited focus on the authenticity dimensions. Previous research suggests that the operation methods can influence customers’ authenticity perceptions (O’Connor et al., Citation2017; Spiggle et al., Citation2012). For example, independent restaurants often demonstrate uniqueness through their unique menus, unique décor and customized services (Harris et al., Citation2014). Additionally, small organizations can achieve a high level of authenticity due to the feeling that brand exploitation is avoided (Spiggle et al., Citation2012).

Standardization and mass production are the key characteristics of chain organizations, and these features promote similarity and reduce uniqueness (Carroll & Wheaton, Citation2009). For example, chain restaurants offer a similar menu; formatted décor; standardized services, even in different countries (Harris et al., Citation2014); and centralized marketing and operations in a given region/country (Carroll & Wheaton, Citation2009). The process of standardization helps chain-affiliated restaurants create a clear brand and corporate image, facilitating the expansion of business (Koh et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, ethnic chain restaurants often create an image in customers’ minds that they are the product category (type) ideal of a specific ethnic cuisine, such as Korean cuisine, through business expansion and positive brand reputation (O’Connor et al., Citation2017). Researchers have also found that consumers are more likely to trust claims made by chain restaurants than those made by independent restaurants (Kim & Song, Citation2020). Based on the above discussion, these restaurant ownership types could serve as a moderator differentially affecting consumers’ authenticity perceptions. Specifically, we propose the following hypotheses:

H13a. Restaurant ownership type moderates the relationship between the true-to-ideal authenticity dimension and overall authenticity perception. More specifically, the effect of true-to-ideal authenticity on overall authenticity perception is stronger among chain restaurant customers than among independent restaurant customers.

H13b. Restaurant ownership type moderates the relationship between the true-to-self-authenticity dimension and overall authenticity perception. More specifically, the effect of true-to-self-authenticity on overall authenticity is stronger among independent restaurant customers than among chain restaurant customers.

H13c. Restaurant ownership type moderates the relationship between the true-to-fact authenticity dimensions and overall authenticity perception. More specifically, the effect of true-to-fact authenticity on overall authenticity is stronger among chain restaurant customers than among independent restaurant customers.

3. Methods

3.1. Measures

The survey questionnaire included measures of the following three authenticity dimensions: overall perceived authenticity, value, and revisit intention. First, Moulard et al. (Citation2021) proposed a conceptual model of authenticity (i.e. true-to-ideal, true-to-self, and true-to-fact). However, there are no scale instruments to measure each authenticity dimension included in Moulard et al.’s model. Thus, we developed measures corresponding to their proposed authenticity dimensions in line with Moulard et al.’s (2021) conceptual discussion and the relevant previous literature (Kim, Citation2021; Kim & Song, Citation2020; Spiggle et al., Citation2012).

For example, the following three items were developed to measure true-to-ideal authenticity: ‘This restaurant seems to embody the essence of Korean ethnic restaurants’, ‘This restaurant preserves what Korean ethnic restaurants mean to me’, and ‘The key associations that I have with Korean ethnic restaurants are present in this restaurant’. The following five items were developed to assess true-to-self authenticity: ‘This restaurant seems to have a true passion for its business’, ‘This restaurant seems to do its best in providing its food and service’, ‘This restaurant seems devoted to what it does’, ‘This restaurant seems to show a strong dedication to the ethnic restaurant business’, and ‘Committed is a word that I would use to describe this restaurant’. The following five items were developed to measure true-to-fact authenticity: ‘I think that this restaurant is credible’, ‘I think that this restaurant has integrity’, ‘Any claims made by this restaurant are trustworthy’, ‘I think that this restaurant tells the truth about the restaurant (e.g. ingredients) to the public’, and ‘I think that this restaurant is honest about its products’.

Overall authenticity was measured using the following three items adapted from Lu et al. (Citation2015) and Guèvremont (Citation2018): ‘I think that this is an authentic Korean restaurant’, ‘I think that this is a genuine Korean ethnic restaurant’, and ‘I think that this is a real Korean ethnic restaurant’. Value was measured using the following three items adopted from Kim et al. (Citation2013): ‘The dining experience at this Korean restaurant is worth the money’, ‘It is a good deal to dine at this Korean restaurant compared to others’, and ‘The overall value of dining at this Korean restaurant is high’. Positive emotions were measured using the following three items adopted from Song et al. (Citation2021): The dining experience at this Korean restaurant was ‘happy’, ‘pleasant’, and ‘joyful’. Revisit intention was assessed using the following three items adapted from Hong and Ahn (Citation2021): ‘I plan to revisit this restaurant’, ‘I will try to revisit this restaurant in the near future’, and ‘I intend to revisit this restaurant’. All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1, representing ‘strongly disagree’, to 7, representing ‘strongly agree’. The survey questionnaire also included questions regarding the ownership type of the restaurant where the participants consumed Korean foods and their sociodemographic characteristics (i.e. gender, age, and education level).

We utilized both methodological and statistical tools to account for common method bias. (CMB). For example, the survey questionnaire included only 25 items. Thus, the questionnaire was sufficiently short to avoid fatigue and confusion, which might have negatively influenced the participants’ cognitive efforts to answer the questions accurately. Furthermore, the items’ language was specific, simple, and concise. Additionally, the adequacy of the scale items was verified by two experts and pretested (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Finally, Harman’s single factor analysis was conducted to identify CMB issues in the data.

3.2. Pilot study

We conducted a pilot test to identify the underlying dimensionality of perceived authenticity. We utilized a Chinese panel data service called Wenjuanxing (www.wjx.cn). Wenjuanxing is similar to other existing panel data collection firms, such as Qualtrics and Amazon Mechanical Turk. For example, there are more than 2.5 million active users from all regions of China in the panel data database, which serves as a source for random sampling data collection. Accordingly, researchers have widely used this valid platform to collect panel data (e.g. Ma et al., Citation2021). For example, more than 2000 studies have utilized samples recruited from Wenjuanxing (Zheng and Zheng, 2014). Therefore, this panel data company is familiar with various academic research methods and processes.

We included a screening question (i.e. Have you dined in a Korean restaurant in the previous six months?) to recruit respondents who could discuss their perceptions of restaurants that they had recently patronized. The developed survey questionnaire was sent to Chinese consumers randomly chosen from the company’s database. Qualified participants were then asked to recall their most recent dining experience at a Korean restaurant and complete the survey questionnaire. In total, 135 valid questionnaires were collected. Most participants (68.8%) were aged between 20 and 30 years. Women (51.1%) outnumbered men (48.9%), 56.3% of the participants had a bachelor’s degree, and 37.8% of the participants were college students. Most participants (63.0%) earned 5000 RMB or less (approximately US$783) per month. Slightly more respondents dined at an independently owned restaurant (50.4%) than at a chain restaurant (49.6%).

Following the recommended procedures to develop a multiple-item scale (Parasuraman et al., Citation2005), we performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the authenticity measurement using varimax rotation. The results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity (938.6, p < .001) and the Kaiser-Myer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (.87) indicated that the factor analysis was appropriate. One item with a low factor loading (<.5) and another item with high cross loadings (>.3) were removed. Consistent with Moulard et al.’s (2021) conceptual model, a three-dimensional authenticity factor structure was identified and explained 68.85% of the total variance. Factor 1 focused on items assessing true-to-fact authenticity (e.g. ‘I think that this restaurant is honest about its products’), factor 2 contained items measuring true-to-self authenticity (e.g. ‘This restaurant seems to have a true passion for its business’), and factor 3 involved items measuring true-to-ideal authenticity (e.g. ‘The key associations I have with Korean ethnic restaurants are presented in this restaurant’). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .83 to .88, indicating satisfactory internal consistency across the construct items (>.70).

3.3. Procedures

Following the same procedures employed in the pilot study, the main data collection was performed with Chinese ethnic diners who had dined at a Korean restaurant. In total, 500 qualified respondents were recruited from a Chinese panel data service company. The collected data were subjected to data screening before the data analyses were conducted.

3.4. Data screening

For the returned questionnaires, we performed data screening to eliminate invalid responses. For example, we scanned the time that each respondent spent completing the survey. If s/he took less than our anticipated required time (i.e. three minutes) to complete the survey, we discarded the response. Furthermore, we checked the data to detect missing responses (>10%, Hair et al., Citation2014) and patterned answers. Throughout this process, we discarded 9 cases, and in total, 491 valid questionnaires were retained for further data analyses. The participant-to-item ratio was 19.6:1, which is significantly higher than the recommended minimum (5:1; Gorsuch, Citation1974).

4. Results

4.1. Participants

The sample included more women than men (n = 252, 51.3% vs. n = 239, 48.7%). The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 56 years (M: 27.0, SD: 7.15), with a median age of 25 years. Regarding the education level, 61.9% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (n = 304), 18.9% held a postgraduate degree (n = 93), 12.6% had technical training (n = 62), and 6.5% were high school graduates or below (n = 32). In terms of occupation, 35.4% of the respondents were students (n = 174), 15.3% were white collar workers (n = 75), 14.1% were salespersons (n = 69), 9.6% were self-employed (n = 47), 7.7% were private business owners (n = 38), 7.1% were professionals (n = 35), 4.3% were unemployed (n = 21), 4.1% were government officers (n = 20), 1.0% were entrepreneurs (n = 5), 0.8% were retirees (n = 4), and 0.6% were homemakers (n = 3). These sample characteristics generally conform to those of ethnic diners who prefer to eat Korean foods. According to a Chinese food market report, Korean foods are the most popular among female customers aged between 18 and 30 years (Bai, Citation2021).

4.2. Normality test

Subsequently, the normal distribution of the data was examined using SPSS software (version 25). The skewness values ranged between −.53 and −.04, and the kurtosis values ranged between −.28 and.46. Thus, the data were normally distributed (Hair et al., Citation2014). These results provided support for utilizing the maximum likelihood estimation method.

4.3. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Prior to performing the CFA, we conducted tests to identify CMB and multicollinearity issues. First, Harman’s single-factor test, which is one of the most widely utilized techniques for testing for CMB (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), was conducted. The results showed that the total variance in a single factor was less than the threshold of 50%, indicating that CMB did not affect the data or results. We also examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of all constructs. The results showed that the values ranged from 1.00–2.30, indicating a very good degree of robustness facing the threshold value of 3 (Belsley et al., Citation1980). Therefore, there were no serious multicollinearity issues in the data.

Then, following Anderson and Gerbing’s (Citation1988) recommendations, the reliability and validity of each construct were examined prior to testing the structural model. Both the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (ranging from .83 to .91) and the composite reliability (ranging from .84 to .91) of all constructs were greater than .70, indicating good internal consistency. A CFA was conducted using AMOS (version 25) to examine the convergent and discriminant validity. The results showed that the overall model fit was satisfactory as follows: χ2/df = 1.78 (χ2 = 438.24, df = 246), CFI = .98, IFI = .98, NFI = .95, TLI = .97, and RMSEA = .04. All scale items were properly loaded on the a priori determined factors. For example, as reported in , the standardized factor loadings of all scale items (ranging from .75 to .92) were greater than .70. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct (ranging from .59 to .78) exceeded .50. Accordingly, convergent validity was supported. Additionally, the square root of the AVEs exceeded the coefficients of the correlations between pairs of corresponding constructs, further confirming the discriminant validity (see ). Following researchers who noted that the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations has high power in diagnosing the discriminant validity (Henseler et al., Citation2015), we also examined the HTMT values using SmartPLS (version 3.3.3). The results showed that all HTMT values (ranging from .49 to .81) were less than the threshold of .85, suggesting sufficient discriminant validity.

Table 1. CFA results.

Table 2. Construct intercorrelations.

4.4. Structural equation model

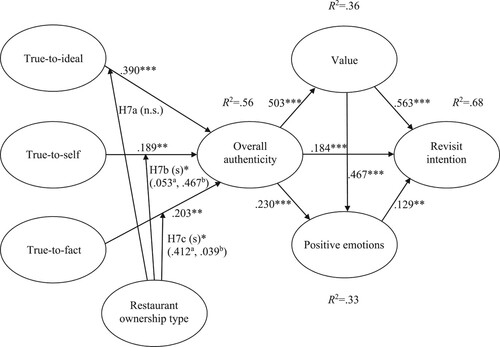

The proposed structural model was then analyzed using AMOS software (version 25). The results indicated a good model fit as follows: χ2/df = 2.26 (χ2 = 574.67, df = 254), CFI = .96, IFI = .96, NFI = .94, TLI = .96 and RMSEA = .05. and present the path coefficients of the causal relationships in the proposed structural model and the R2 of the endogenous variables. Regarding the total variance explained, the three authenticity dimensions explained 56% of the overall perceived authenticity. Overall perceived authenticity accounted for 36% of the variance in value. Authenticity and value perceptions explained 33% of positive emotions. All study variables explained 68% of the variance in revisit intention.

Table 3. Results of the hypothesis testing.

As shown in , all authenticity dimensions (true-to-ideal: β = .390, t = 8.531, p < .001; true-to-self: β = .189, t = 2.887, p < .01; true-to-fact: β = .203, t = 3.179, p < .01) significantly influenced overall authenticity. Thus, H1, H2, and H3 were supported. These results suggest that the more strongly that the participants felt a Korean ethnic restaurant was true-to-ideal, true-to-self, and true-to-fact, the more strongly they perceived the restaurant to be authentic. The larger β value of the causal path between true-to-ideal and overall authenticity indicates that the true-to-ideal dimension is more influential than the other authenticity dimensions in terms of increasing overall perceived authenticity.

Furthermore, consistent with H4, the respondents’ overall authenticity perceptions (β = .184, t = 4.580, p < .001) significantly influenced revisit intention. This result suggests that the more strongly that a respondent perceives authenticity in a Korean ethnic restaurant, the stronger his or her intention to revisit the restaurant. H5 predicted that overall perceived authenticity would increase one’s perceived value of the dining experience. The results showed a significant path from overall perceived authenticity to value perception (β = .503, t = 11.896, p < .001). Thus, H5 was supported. Therefore, the greater a respondent’s perceived authenticity of a Korean restaurant, the greater his or her perceived value of the dining experience.

In support of H6, the results showed that overall authenticity perception significantly affects positive emotions (β = .230, t = 5.092, p < .001). Thus, the more strongly that a respondent perceives authenticity, the greater his or her positive emotions toward the restaurant. Additionally, perceived value was found to significantly increase positive emotions (β = .467, t = 10.272, p < .001) and revisit intentions (β = .563, t = 14.534, p < .001). Thus, H7 and H8 were supported. These results suggest that the more that a respondent perceives the value of dining experiences, the stronger his or her positive emotions toward the restaurant and intention to revisit. H9 posited that positive emotions affect revisit intentions. The results showed a significant path from positive emotions to revisit intention (β = .129, t = 2.691, p < .01). Thus, H9 is supported.

This study also examined the effect sizes (f2) of the causal relationships between the variables reported in . Based on Cohen’s (Citation1988) discussion (i.e. values ranging from 0.02–0.15, 0.15–0.35, and 0.35 or greater indicate weak, medium, and large effects, respectively), the results showed adequate statistical power. Then, we examined the indirect effect of overall authenticity perception on revisit intentions. The results confirmed that perceived value mediates the relationship between overall authenticity perception and revisit intention (β = .283, t = 9.590, p < .001), supporting H10. Furthermore, consistent with H11, positive emotions mediate the relationship between overall perceived authenticity and revisit intention (β = .030, t = 2.423, p < .05). Additionally, the relationship between overall authenticity perception and revisit intention is mediated by perceived value and positive emotions (β = .030, t = 2.545, p < .05), supporting H12. Regarding the magnitude of the mediation paths, the pathway through perceived value has a greater effect (β = .283) than the other two pathways of positive emotions (β = .030) and perceived value and positive emotions combined (β = .030).

4.5. Moderating effect of ownership type

This study conducted a multiple-group analysis to test the moderating effect of the ownership type of restaurants. The samples were divided into chain restaurants (n = 242) and independent restaurants (n = 249) based on the participants’ responses. Then, we examined the chi-square difference between the constrained and unconstrained models with regard to the difference in degrees of freedom to test the differential effect of ownership type (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988).

As reported in , the results showed that the restaurant ownership type had a significant effect on the relationships between true-to-self and overall perceived authenticity (Δχ2(df = 1) = 4.00, p < .05) and between true-to-fact and overall perceived authenticity (Δχ2(df = 1) = 5.90, p < .05). In support of H13b, the influence of true-to-self on overall perceived authenticity was greater among customers who dined in an independently owned restaurant than among those who dined in a chain restaurant. Furthermore, consistent with H13c, the influence of true-to-fact on overall perceived authenticity was more profound among customers who patronized an independent restaurant than among those who patronized a chain restaurant. However, a nonsignificant group difference between customers who patronized an independent restaurant and those who patronized a chain restaurant was identified between true-to-ideal and overall perceived authenticity (Δχ2(df = 1) = .01, n.s.). This result suggests that the authenticity dimension of true-to-ideal equally influenced the participants’ overall perceived authenticity regardless of the ownership type of the restaurant that they patronized.

Table 4. Results of the moderating effects.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical discussion

This study offers several important theoretical contributions to the ethnic restaurant literature. First, the current study responds to calls by researchers to study the multiple dimensions of authentic dining experiences (Le et al., Citation2021). In the hospitality literature, research examining authenticity has been preoccupied with a single dimension of authenticity, such as the authenticity of the other (Le et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by focusing on the multiple dimensions of authenticity and testing their influences on consumer behavior.

The study results support Moulard et al.’s (Citation2021) conceptual model and previous researchers who discussed the influence of various factors on perceived authenticity. For example, researchers have found that congruence between the attributes of purchased products and customers’ perceived image of the products conveys a feeling of authenticity (Kim & Jang, Citation2016). Corroborating this finding, we found that true-to-ideal authenticity significantly influences overall authenticity perception (H1). We also found that true-to-fact authenticity (e.g. credibility of a restaurant’s marketing communication) significantly impacts customers’ overall authenticity perceptions (H2). This result is consistent with previous research that identified a significant influence of customers’ perceived credibility/honesty toward a business on authenticity perception (Kim, Citation2021). Furthermore, in support of previous findings (Spiggle et al., Citation2012), this study identified a significant influence of a restaurant’s passion and dedication toward conducting its business (i.e. true-to-self-authenticity) on authenticity perception (H3).

Another interesting finding of this study is the comparative influence of the authenticity dimension on customers’ overall perceived authenticity. Among the three authenticity dimensions, true-to-ideal authenticity is the most significant determinant of overall perceived authenticity. Consistent with previous research findings that authenticity plays a key role in determining consumer behavior (De Vries & Go, Citation2017; Latiff et al., Citation2020; Taheri et al., Citation2020; Youn & Kim, Citation2017), this study found a direct influence of perceived authenticity on revisit intention (H4).

Researchers have noted that customers’ perceived authenticity of a product increases their perceived economic value of the transaction (Hernandez-Fernandez & Lewis, Citation2019; Kovács et al., Citation2014) and positive emotions (Jang & Ha, Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2020). Corroborating these findings, this study found that overall authenticity evaluation of a Korean restaurant significantly impacted customers’ value perceptions (H5) and positive emotions (H6). Furthermore, this study identified that perceived value significantly influences positive emotions (H7). This result provides support for previous findings that customers’ value perceptions increase their positive emotions (Song & Qu, Citation2017; Zielke, Citation2014). The study results also showed that Chinese ethnic diners’ perceived value and positive emotions are antecedents of revisit intention (H8 and H9). These findings corroborate those of researchers suggesting that personal values (Chen et al., Citation2020; Kuo et al., Citation2009) and positive emotions (Kim, Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2017) affect consumer behavior.

Another important theoretical contribution of this study is that this study is among the few studies examining the mechanism by which authenticity perception influences consumer behavior. Previous authenticity research has mainly examined the direct influence of authenticity on consumer behavior (Kim & Baker, Citation2017; Wang & Mattila, Citation2015; Youn & Kim, Citation2017). Grounded in an extended S-O-R theory, this study extends research concerning the perceived authenticity effect by examining its indirect effects on revisit intention. In support of the current theorization and previous researchers, this study observed the significant indirect effects of authenticity perception through the mechanism variables of perceived value and positive emotions on revisit intention. In summary, the following relationships were established: overall authenticity→ perceived value→ revisit intention (H10); overall authenticity→ positive emotions→ revisit intention (H11); and overall authenticity→ perceived value→ positive emotions→ revisit intention (H12). These results show that the indirect effects of authenticity perception on revision intention are recognized via the mediating effects of customers’ perceived value and positive emotions. Furthermore, the results demonstrate that the direct effect of overall authenticity perception (β = .184) is smaller than its indirect effect through perceived value (β = .283). These findings provide theoretical implications that could help us better understand how authenticity perception influences ethnic diners’ revisit intentions.

Finally, this study makes an important contribution to the literature by identifying the moderating effect of restaurant ownership type on the relationship between authenticity dimensions and customers’ overall authenticity perceptions. The hospitality literature has drawn inconsistent conclusions regarding the effect of restaurant ownership type on customers’ authenticity perceptions. For example, some researchers have reported that the standardization of products decreases customers’ authenticity perceptions, indicating that chain restaurants are perceived as inauthentic (e.g. Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006). However, others have argued that chain organizations can also provide highly authentic dining experiences (Kim et al., Citation2020; Kim & Song, Citation2020). The results showed that both chain and independent restaurants can deliver authentic dining experiences. Utilizing a three-dimensional authenticity model, this study further illuminates the various mechanisms by which restaurants with different ownership types affect perceived authenticity (H13a, H13b, and H13c). For example, chain restaurants generate perceived authenticity through true-to-ideal and true-to-fact authenticity, whereas independent restaurants generate perceived authenticity by conveying true-to-ideal and true-to-self-authenticity.

5.2. Practical implications

We provide several practical suggestions to ethnic restaurant operators, including Korean restaurants in China, based on the study results. This study confirmed the antecedents (i.e. true-to-ideal, true-to-self, and true-to-fact authenticity) and consequences (i.e. value perception, positive emotions, and revisit intention) of customers’ overall authenticity perceptions. Accordingly, the results suggest that ethnic restauranteurs should improve customer experience design and marketing communication to enrich all three types of authenticity.

First, ethnic restaurants might achieve high true-to-ideal authenticity if they well represent their product offerings and service environments, conforming to customers’ images and expectations of the cultural theme of the restaurant. Thus, all efforts to develop authenticity cues should be carefully developed from the customer perspective. For example, ethnic restauranteurs should develop their menus by including iconic or symbolic dishes that customers can easily associate with the theme of ethnic cuisine, such as Tom yum kung in Thai restaurants, tandoori chicken in Indian restaurants, and Kimchi jjigae in Korean restaurants. Furthermore, other ethnic cues expressing the ethnic theme of a restaurant, such as flatware cutlery sets, décor, and service style, should be designed, aligning to the ideals or common standards established in the target market. The results show that the effects of true-to-ideal authenticity on the overall authenticity perception are similar between chain and independent restaurants. Thus, both restaurant types should convey true-to-ideal authenticity to their customers.

Second, high true-to-self-authenticity can be showcased through a true passion, commitment and enthusiasm for the products, service, and business. Since the effect of true-to-self-authenticity for independent restaurant customers is stronger than that for chain restaurant customers, independent restaurants should particularly focus on enhancing true-to-self-authenticity. Independent restaurants can communicate to customers that they are not keen on expanding business but are focused on the excellence and quality of products to provide unique dining experiences. For instance, the extensive manual work involved in preparing dishes (e.g. handmade noodles) and the artisanal standards that limit the quantities of production could give the impression that the business is passionate about producing foods and is motivated primarily by its love of the business rather than financial rewards. Other business practices could include the development of a seasonal dish following the culinary culture of ethnic origin. For example, a Korean restaurant could serve tteokguk, rice cake soup on New Year’s Day and samgyetang, ginseng chicken soup during the summer.

Third, the results show that true-to-fact authenticity also significantly affects ethnic diners’ overall authenticity perceptions. Thus, if a marketing promotion truly reflects the product and service quality, customers are likely to form a high true-to-fact authenticity of the restaurant (e.g. the claims are reliable and honest), which, in turn, contributes to customers’ high overall authenticity perceptions. Accordingly, ethnic restauranteurs should provide the same food products as described in advertisements. For example, if a Korean restaurant advertised that the key ingredients are delivered from Korea, cooking and dipping sauces are made in Korea, and dishes are made by Korean chefs, the business must keep these promises. Any inconsistency between the real product offerings and advertised content provides the impression of lying or deception, which damages true-to-fact authenticity. Since the effect of true-to-fact authenticity is stronger among chain restaurant customers than independent restaurant customers, Korean chain restaurants in China must pay particular attention to marketing communication messages to provide accurate information about their products.

6. Limitations and future research

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, this study was implemented in China while focusing on Chinese ethnic diners. Researchers have noted that Chinese customers have favorable attitudes and images toward chain restaurants (Kim & Song, Citation2020). Thus, the current study findings might not be applicable to populations in other countries. Future research employing samples from other national groups is required to support the external validity of this study’s findings. Furthermore, this study recruited respondents using a panel data service and asked them to recollect their most recent dining experience at a Korean restaurant in the previous six months. Thus, the respondents’ memory bias and the panel data company’s rigorous procedures in data collection could not be controlled. To improve these issues, future research could collect data at target restaurants by intercepting diners who finished their meals as they exit the restaurants.

This study also focused on three authenticity factors that are mainly related to a restaurant’s attributes. However, a recent study suggested that individuals’ personality traits related to authenticity perception, such as self-authenticity, can influence consumer preferences and future behaviors (Wood et al., Citation2008). Accordingly, future studies should extend the current study model by examining the influence of this factor on consumer behavior. Additionally, this study utilized a second-order factor structure of perceived authenticity in line with the current study purposes. However, given that the three types of authenticity could impact consumer perceptions and behaviors differently, future research should operationalize the first-order construct of authenticity and examine the comparative influences of the three authenticity dimensions on consumer behavior. Finally, this study assessed revisit intention rather than actual behavior. Although some researchers have reported that behavioral intention measures can be utilized as substitutes for actual behaviors (Reich et al., Citation2005), others are concerned about their low predictability of actual consumer behavior (Buzby & Skees, Citation1994). Thus, future research employing real purchase data could further validate the current study results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amirtha, R., & Sivakumar, V. J. (2021). Building loyalty through perceived value in online shopping – does family life cycle stage matter? The Service Industries Journal, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.1960982

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Arora, S., Parida, R., & Sahney, S. (2020). Understanding consumers’ showrooming behaviour: A stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) perspective. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(11), 1157–1176. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-01-2020-0033

- Bai, X. F. (2021). New thoughts of food and beverage: Focusing on customers. Renmin Youdian Publisher.

- Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. John Wiley & Sons.

- Buzby, J., & Skees, J. (1994). Consumers want reduced exposure to pesticides on food. Food Review/National Food Review, 16(2), 19–22. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.266146

- Carroll, G. R., & Wheaton, D. R. (2009). The organizational construction of authenticity: An examination of contemporary food and dining in the U.S.. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.06.003

- Chen, Q., Huang, R., & Hou, B. (2020). Perceived authenticity of traditional branded restaurants (China): impacts on perceived quality, perceived value, and behavioural intentions. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(23), 2950–2971. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1776687

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- De Vries, H. J., & Go, F. M. (2017). Developing a common standard for authentic restaurants. The Service Industries Journal, 37(15-16), 1008–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1373763

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Harris, K. J., DiPietro, R. B., Murphy, K. S., & Rivera, G. (2014). Critical food safety violations in florida: Relationship to location and chain vs. Non-chain restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 38, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.12.005

- DiPietro, R. B., & Levitt, J. (2019). Restaurant authenticity: Factors that influence perception, satisfaction and return intentions at regional American-style restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 20(1), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2017.1359734

- Gilmore, J. H., & Pine IIB. J. (2007). Authenticity: What customers really want. Harvard Business School Press.

- Gorsuch, R. L. (1974). Factor analysis. WB Saunders.

- Grayson, K., & Martinec, R. (2004). Consumer perceptions of iconicity and indexicality and their influence on assessments of authentic market offerings. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(2), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1086/422109

- Guèvremont, A. (2018). Creating and interpreting brand authenticity: The case of a young brand. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17(6), 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1735

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hernandez-Fernandez, A., & Lewis, M. C. (2019). Brand authenticity leads to perceived value and brand trust. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 28(3), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-10-2017-0027

- Hicks, J. A., Schlegel, R. J., & Newman, G. E. (2019). Introduction to the special issue: Authenticity: Novel insights into a valued, yet elusive, concept. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019829474

- Hong, E., & Ahn, J. (2021). Effect of social status signaling in an organic restaurant setting. The Service Industries Journal, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.2006644

- Jang, S., & Ha, J. (2015). The influence of cultural experience: Emotions in relation to authenticity at ethnic restaurants. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 18(3), 287–306.

- Keiningham, T.L., He, Z., Hillebrand, B., Jang, J., Suess, C., & Wu, L. (2019). Creating innovation that drives authenticity. Journal of Service Management, 30(3), 369–391.

- Kim, H. J., Park, J., Kim, M.-J., & Ryu, K. (2013). Does perceived restaurant food healthiness matter? Its influence on value, satisfaction and revisit intentions in restaurant operations in South Korea. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.10.010

- Kim, J.-H. (2021). Service authenticity and its effect on positive emotions. Journal of Services Marketing, 35(5), 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-07-2020-0261

- Kim, J.-H., & Jang, S. (2016). Determinants of authentic experiences: an extended Gilmore and Pine model for ethnic restaurants. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(10), 2247–2266. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2015-0284

- Kim, J.-H., & Song, H. (2020). The influence of perceived credibility on purchase intention via competence and authenticity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102617

- Kim, J.-H., Song, H., & Youn, H. (2020). The chain of effects from authenticity cues to purchase intention: The role of emotions and restaurant image. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102354

- Kim, J.-H., Youn, H., & Rao, Y. (2017). Customer responses to food-related attributes in ethnic restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.11.003

- Kim, K., & Baker, M. A. (2017). The impacts of service provider name, ethnicity, and menu information on perceived authenticity and behaviors. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(3), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965516686107

- Kim, S.-H., Kim, M., Holland, S., & Townsend, K. M. (2021). Consumer-based brand authenticity and brand trust in brand loyalty in the Korean coffee shop market. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(3), 423–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020980058

- Kim, W. G., & Moon, Y. J. (2009). Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.010

- Koh, Y., Rhou, Y., Lee, S., & Singal, M. (2018). Does franchising alleviate restaurants’ vulnerability to economic conditions? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(4), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348015619411

- Kovács, B., Carroll, G. R., & Lehman, D. W. (2014). Authenticity and consumer value ratings: Empirical tests from the restaurant domain. Organization Science, 25(2), 458–478. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0843

- Kuo, Y.-F., Wu, C.-M., & Deng, W.-J. (2009). The relationships among service quality, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and post-purchase intention in mobile value-added services. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.03.003

- Latiff, K., Ng, S. I., Aziz, Y. A., & Basha, N. K. (2020). Food authenticity as one of the stimuli to world heritage sites. British Food Journal, 122(6), 1755–1776. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2019-0042

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Cognition and motivation in emotion. American Psychologist, 46(4), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.352

- Le, T. H., Arcodia, C., Abreu Novais, M., Kralj, A., & Phan, T. C. (2021). Exploring the multi-dimensionality of authenticity in dining experiences using online reviews. Tourism Management, 85, 104292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104292

- Le, T. H., Arcodia, C., Novais, M. A., & Kralj, A. (2019). What we know and do not know about authenticity in dining experiences: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management, 74, 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.02.012

- Lee, C., Hallak, R., & Sardeshmukh, S. R. (2016). Drivers of success in independent restaurants: A study of the Australian restaurant sector. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 29, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.06.003

- Lehman, D. W., O’Connor, K., & Carroll, G. R. (2019). Acting on authenticity: Individual interpretations and behavioral responses. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019829470

- Lin, Y. C., & Liu, Y. C. (2018). Deconstructing the internal structure of perceived authenticity for heritage tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(12), 2134–2152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1545022

- Liu, H., Li, H., DiPietro, R., & Levitt, J. (2018). The role of authenticity in mainstream ethnic restaurants: evidence from an independent full-service Italian restaurant. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(2), 1035–1053. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0410

- Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., & Lu, C. Y. (2015). Authenticity perceptions, brand equity and brand choice intention: The case of ethnic restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.008

- Ma, J., Tu, H., Zhou, X., & Niu, W. (2021). Can brand anthropomorphism trigger emotional brand attachment? The Service Industries Journal, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.2012163

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press.

- Moulard, J. G., Raggio, R. D., & Folse, J. A. G. (2016). Brand authenticity: Testing the antecedents and outcomes of brand management's passion for its products. Psychology & Marketing, 33(6), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20888

- Moulard, J. G., Raggio, R. D., & Folse, J. A. G. (2021). Disentangling the meanings of brand authenticity: The entity-referent correspondence framework of authenticity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(1), 96–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00735-1

- Nguyen, T. H. H. (2020). A reflective–formative hierarchical component model of perceived authenticity. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(8), 1211–1234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020944460

- O’Connor, K., Carroll, G. R., & Kovács, B. (2017). Disambiguating authenticity: Interpretations of value and appeal. PLoS one, 12(6), e0179187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179187

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Malhotra, A. (2005). E-S-QUAL. Journal of Service Research, 7(3), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670504271156

- Pelet, J.-E., Durrieu, F., & Lick, E. (2020). Label design of wines sold online: Effects of perceived authenticity on purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102087

- Peterson, R. A. (2005). In search of authenticity. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1083–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00533.x

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Robinson, R. N., & Clifford, C. (2012) Authenticity and festival foodservice experiences. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 571–600.

- Reich, A. Z., McCleary, K. W., Tepanon, Y., & Weaver, P. A. (2005). Roles of product and service quality on brand loyalty: an investigation of quick service restaurants. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 8(3), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J369v08n03_04

- Rodriguez-Lopez, M. E., Del Barrio-García, S., & Alcántara-Pilar, J. (2020). Formation of customer-based brand equity via authenticity: the mediating role of satisfaction and the moderating role of restaurant type. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(2), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2019-0473

- Song, H., & Kim, J.-H. (2021). Developing a brand heritage model for time-honoured brands: Extending signalling theory. Current Issues in Tourism, published online on 14 May, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1926441

- Song, H., Xu, J., & Kim, J.-H. (2021). Nostalgic experiences in time-honored restaurants: Antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 99, 103080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103080

- Song, J., & Qu, H. (2017). The mediating role of consumption emotions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.015

- Spiggle, S., Nguyen, H. T., & Caravella, M. (2012). More than fit: Brand extension authenticity. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(6), 967–983. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.11.0015

- Steiner, C. J., & Reisinger, Y. (2006). Understanding existential authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.08.002

- Taheri, B., Gannon, M. J., & Kesgin, M. (2020). Visitors’ perceived trust in sincere, authentic, and memorable heritage experiences. The Service Industries Journal, 40(9-10), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1642877

- Vitezić, V., & Perić, M. (2021). Artificial intelligence acceptance in services: Connecting with generation Z. The Service Industries Journal, 41(13-14), 926–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.1974406

- Wang, C.-Y., & Mattila, A. S. (2015). The impact of servicescape cues on consumer pre-purchase authenticity assessment and patronage intentions to ethnic restaurants. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 39(3), 346–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013491600

- Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

- Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385

- Xu, X. A., Wang, L., Song, Z., & Song, J. (2021). Brand equity for self-driving route along the silk road. The Service Industries Journal, 41(7-8), 462–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1569633

- Yang, K., Kim, J., Min, J., & Hernandez-Calderon, A. (2021). Effects of retailers’ service quality and legitimacy on behavioral intention: The role of emotions during COVID-19. The Service Industries Journal, 41(1-2), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2020.1863373

- Youn, H., & Kim, J.-H. (2017). Effects of ingredients, names and stories about food origins on perceived authenticity and purchase intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 63, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.01.002

- Zielke, S. (2014). Shopping in discount stores: The role of price-related attributions, emotions and value perception. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(3), 327-338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.04.008