ABSTRACT

This case study explores students’ perceptions of the effects of expanded student services on their mental health literacy (MHL). The data is derived from a pilot project that provides additional resources for health care professionals and social workers in an upper secondary school (students aged 16–19) to better enable them to enhance the mental health literacy of the students. MHL comprises students’ knowledge about the antecedents of and risk factors for mental health problems, the nature of mental illness, the lgocation of resources and the promotion of positive mental health. The majority of students (>70%) reported improved MHL as a result of their participation in the pilot project. They found it easier to contact health professionals and to speak openly about mental health issues, and they also reported increased knowledge about mental health due to the project. Still, in comparison to the female students the male students found it easier to talk about mental health with teachers, school counsellors and school nurses. Implications of the study will be discussed.

Introduction

This paper addresses openness and help-seeking behaviour among students as some of the key aspects of mental health literacy (MHL). The concept of MHL ‘broadly refers to the knowledge and abilities necessary to benefit mental health’ (Bjørnsen et al., Citation2017). According to Kutcher et al. (Citation2016), MHL comprise four key components. These are: (1) decreasing the stigma related to the causes of mental health problems; (2) knowledge about how to obtain and maintain positive mental health; (3) understanding mental disorders and their treatments; and, (4) enhancing help-seeking efficacy (knowing when and where to seek help and developing competencies designed to improve one’s mental health care and self-management capabilities) (p. 155). There is evidence that interventions based in educational settings are effective to improve MHL, and that talking to students about mental health increase their willingness to seek help from school counsellors or health professionals (Jorm, Citation2012). Consequently, improving MHL among students is fundamental for promoting mental health in the schools.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health has indicated that only 17% of adolescents (aged 13–15) with severe emotional difficulties seek assistance for their problems (Helland & Mathiesen, Citation2009). These low help-seeking rates may be the result of stigma, poor access to mental health services or the absence of a trusted friend or adult to talk to (Idsøe et al., Citation2016). Consequently, many students struggle alone daily with mental health problems without receiving any help to manage their situations. This finding is supported by international studies that have revealed low help-seeking rates for students with unmet needs for psychological counselling or treatment (Sheppard et al., Citation2018). The problem seems to be worse among male adolescents aged 12–19 years (Clark et al., Citation2018; Johansson et al., Citation2007). Fearing stigmatising responses from parents, teachers and peers, adolescents seem to be reluctant to disclose their mental health problems (Chandra & Minkovitz, Citation2007). There is also a clear difference in teenagers’ help-seeking behaviours around physical and mental health issues. By far, physical symptoms, such as asthma, flu or back pain, are characterised as ‘normal, painful and treatable’, and symptoms such as tearfulness, sadness or anxiety are characterised as ‘painless, taboo and untreatable’ (MacLean et al., Citation2013, p. 166). Wright et al. (Citation2012) found that mental health problems related to stress or shyness predicted less intention to seek help.

There is a significant relationship between stress and mental health problems (Lillejord et al., Citation2017), and early help-seeking is necessary to prevent their escalation. Therefore, the reduction of mental health stigma and the creation of an enabling environment to increase students’ willingness and opportunities to talk to someone about their mental health issues are important aspects of mental health promotion in schools. According to the Norwegian government, all K-12 schools have a responsibility to identify students that are not coping well and help them to get the help they need. Sometimes, this may happen at school and sometimes with help from other services’ (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2015, p. 171).

This paper explores the perceived effects of an expanded student services pilot project in an upper secondary school. In Norway, upper secondary students can choose between Vocational Education Programmes and Education Programmes for Specialization in General Studies. Our study was conducted at a school solely for Vocational Education Programmes. The ‘expanded services’ included new positions for social workers at school, and more resources to school nurse. The aim of the project was to improve students’ help-seeking rates and ability to talk openly about their mental health problems, which both are essential components in MHL. Hence, the main research questions in this paper are:

What is the perceived effect of expanded student services on students’ help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues?

What are the students’ suggestions for teachers to facilitate help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues?

The problem of mental health stigma

Poor MHL and prejudiced attitudes towards the antecedents and causes of mental health problems is a major contributor to the persistence of mental health stigma all over the world (Funk et al., Citation2010). This is supported by a Norwegian white paper on public health, indicating that individuals with mental illness not only are engaged in a fight against stigma, but also suffer from self-stigmatization and reduced ability to learn due to their mental health difficulties (Ministry of Health and Care Services, Citation2014). Coping with the symptoms, such as the mood swings and physical pain that often accompany depression or anxiety, can be difficult and exhausting. Hence, there may be little energy left to schoolwork and social activities. In addition, and due to the problem of stigma, many students are afraid of revealing their struggles with poor mental health because of the fear of hindering their chances of earning good grades or gaining employment. This problem has been attributed mainly to the major misunderstanding that mental health problems are life-long rather than temporary (Reavley & Jorm, Citation2011). Studies on the stigmatic attitudes toward mentally ill individuals have concluded that improved knowledge about the nature and causes of mental illness is vital for the prevention of stigmatising misconceptions (Lyngstad, Citation2000; Reavley & Jorm, Citation2011). Finally, individuals with mental health problems often suffer from self-stigmatisation. They perceive themselves as being less worthy, and they are unable to take actions to improve their situations. Such learned helplessness is often linked to mental health difficulties such as depression in which an individual perceives the current situation as hopeless and beyond his/her control (Seligman, Citation1975; Seligman et al., Citation2009).

The fear of being stigmatised or ‘looked down upon’ because of mental health problems has been discussed in other studies. Buchanan and Murray (Citation2012) highlighted the problem of students’ inability to talk openly about their problems in school for fear of being disrespected or degraded by teachers or other students. In a recent study at Vocational Education Programmes in upper secondary school, many students cited embarrassment, discomfort and fear of loss of status with peers as help-seeking barriers. The students also expressed concerns about being looked down upon or being considered weak by their peers (Tharaldsen et al., Citation2017). Anvik and Eide (Citation2011) found that students with mental health problems perceived that they were not being taken seriously by their teachers. In addition, they were subjected to low expectations and were being treated negatively. Moses (Citation2010) found that 35% of high school students held teachers partly responsible for their feelings of stigmatisation. Hence, the availability of alternative persons with whom students can discuss these issues is important.

Research indicate that loneliness peaks during adolescence (Heinrich & Gullone, Citation2006). Loneliness is related to a lack of emotional support and the perceived lack of a confidant (Wang et al., Citation2017), and according to Jones et al. (Citation2011), loneliness emerges from a discrepancy between the need for and the perception of having social relationships. Social support and relationships are vital for positive mental health, and social relationship deficits are linked to increased risks for mental problems such as depression and suicidal behaviours. The transition from lower secondary to upper secondary school represents a period of change in social support and the formation of new friendships. For some, the transition also includes changes in their living situations, as they move away from friends and family to attend school. For many students, the school-based mental health services could serve as a gateway to help-seeking. Gender differences are identified here, in that female adolescents are more likely than male adolescents to seek help from mental health professionals (Menna & Ruck, Citation2004).

The problem of not having anyone to talk to

According to Kidger et al. (Citation2009), students with mental health difficulties prefer to talk to health professionals, such as the school nurse, rather than their teachers because the health professionals ‘talk to you like you’re a normal person’ (p. 11) and know more about mental health. In a study of gender differences in MHL among young people (aged 17–22 years), males rated self-helping strategies significantly higher than females and were more aversive towards seeking help from mental health professionals or parents. Overall, teachers were rated quite low as a source of help (Furnham et al., Citation2014). Still, teachers are key professionals for identifying emerging mental health problems among students and may encourage the students to seek professional help (Stiffman et al., Citation2004; Williams et al., Citation2007). Moreover, teachers can facilitate positive mental health through the provision of emotional and academical support to their students (Danielsen et al., Citation2009).In a study of adolescents with mental health problems, 17% of the students in upper secondary school said they were unable to talk to someone about their problems, and 9% reported not having anyone to talk to (Anvik & Gustavsen, Citation2012).

While the key professional that students prefer to talk to is the school nurse (Kidger et al., Citation2009), a cross-sectional study of 284 school nurses in Norway found that they often felt that they lacked the necessary training and knowledge to meet the adolescents’ mental health needs (Skundberg‐Kletthagen & Moen, Citation2017). Inadequate knowledge about available school resources was identified as one of the main help-seeking barriers for upper secondary students (Tharaldsen et al., Citation2017). This indicates students’ lack of awareness of available resources, hence their perceptions of the lack of someone with whom they can discuss mental health issues at school. The provision of information about student services is therefore vital to students’ use of such services for existing and emergent mental health problems.

One approach could be the use of screening tools to assess students’ needs for targeted approaches, such as small group conversations with the school nurse. In Norway, a recent study has facilitated such trials of interventions as part of a universal work strategy for school health services. The evaluations identified significant differences in MHL between the test and the control group participants. There was a significant positive increase in the girls’ overall mental well-being. The intervention seemed to be of more benefit for the girls, as participation improved their overall mental well-being scores (Bjørnsen et al., Citation2018). These results demonstrate the importance of supplemental interventions through student services targeted to those identified as experiencing or being at risk for emergent mental health problems.

Materials and methods

Sample characteristics and research design

This study can be characterised as having a mixed methods design. According to Lund (Citation2005), a mixed methods study ‘involves the collection or analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study in which the data are collected concurrently or sequentially, are given a priority, and involve the integration of the data at one or more stages in the process of research’ (p. 156). Here, the questions to elicit the qualitative data were part of the quantitative research instrument, providing an embedded design (Creswell, Citation2009).

The school was selected based on its engagement in a Norwegian Department of Health-funded pilot project for expanding inter-professional collaboration among teachers, social workers and health care professionals. One of the innovations was the increased presence of social workers in school. The project resulted in the creation of a new position: a community worker responsible for follow-up, especially during the students’ apprenticeships. It also established a schedule for weekly meetings of the psychiatric nurses and specialists from the municipality’s mental health and addiction care services to be held at the schools. A job specialist from the local Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration was hired to monitor the students and to prevent dropout.

The data were collected in May 2018 from 157 boys and 103 girls (N = 260) in an upper secondary school, providing Vocational Education Programmes only. The response rate was 82%. The questionnaire, which comprised 9 Likert -scaled questions with a total of 35 items and three open-ended questions was administered using a QR code that the students scanned with their mobile devices. All the data were collected under the supervision of a teacher or researcher during school hours. This enabled the students to be informed about the survey and its aim. It also provided the opportunity to address misconceptions and to assist with the translation of difficult words and phrases for the students for whom Norwegian was not their first language. The students were well informed about their right to deny participation, withdraw without fear of penalty and skip individual items during the survey.

Measures

Based on their relevance to the main research questions in this paper, 20 out of 35 items and all three open-ended questions were selected for analysis. The individual survey items and the measures are presented in . Some questions were more general, and others required the students to rate each collaborative student services partner based on the perceived importance to student mental health and well-being at school. The collaborative partners included in the survey were the school counsellors, psychiatric nurses, community workers, job specialists and school nurses. The open-ended questions addressed (1) the students’ overall satisfaction with the expanded student services, (2) the teachers’ role in promoting student mental health through their regular teaching activities and (3) the school’s role in promoting student mental health.

Table 1. Survey item overview

Analysis

The survey findings were first analysed through descriptive statistics. The expanded student service project introduced new groups of professionals to the students and included them in school context. These groups were psychiatric nurses, social workers and job specialists. Due to this, it is interesting to identify potential differences in student ratings on the different groups of professionals. Next, ANOVA with a series of t-tests were performed with gender as the independent variable and the question ‘How easy is it for you to talk to the following persons in student services about mental health issues?’ as the dependent variable. This was done to identify potential between-group differences between boys’ and girls’ experiences related to talking about mental health with different professionals. Finally, the potential correlation between some of the variables related to openness about mental health and help-seeking behaviour, were explored through Pearson’s r. In sum, these analyses intended to cover research question number one: What is the perceived effect of expanded student services on students’ help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues? The results of the quantitative analysis were supplemented by the findings from the open-ended questions to provide a more complete and nuanced understanding of student perceptions. This complementarity is a main advantage of mixed method designs and can only be accomplished by combining qualitative and quantitative data (Teddlie & Tashakkori, Citation2009).

The qualitative analysis was accomplished through classical content analysis with inductive coding (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2008, Citation2011). This represents a continual process of alternating between theory-driven and empirically driven analytical categories. The process started with a thorough reading of the statements from the three open-ended questions. Next, the statements were coded with the NVivo11© software, sorting textual elements into thematic categories (nodes). In this round of coding, five main categories emerged. These were; information about student services, importance of student services, availability of student services, fear of making contact and teachers’ role and impact. The qualitative data, and especially the last category, provided the main basis for addressing the second research question: What are the students’ suggestions for teachers to facilitate help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues?

Results

Students perceived effect of expanded student services on their MHL

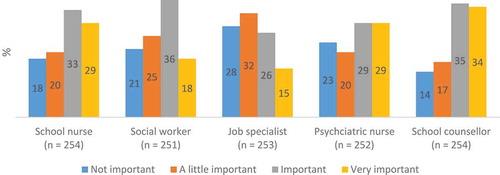

indicates that the students believe that it is most important that school counsellors, psychiatric nurses and school nurses make themselves familiar to the students and shows that one out of three students believes that easy access to these three groups of professionals is very important to facilitate help-seeking. Here, the psychiatric nurses represent the ‘new’ element in the expanded student services and these professionals have not previously been located at the school.

Figure 1. Responses to the following question: how important is it for you and your mental health that the following student services staff walk around the school to get to know the students?

Figure 2. Responses to the following question: how important is it that the following student services staff be accessible so that you can easily contact them about mental health issues at school?

Regarding the qualitative data, getting to know the students and disseminating information about student services was highlighted as being important for promoting student mental health. The main argument was that familiarity with the services and the staff made it much easier for students to take contact and to seek help when necessary. According to a student survey respondent:

It is very good that we have student services at our school, and I recommend that the school counsellors and others get to know the students better and be with them during break. This makes it easier for the students who are struggling to seek help when they need it. I also recommend that the teachers talk more with students during break. This builds friendship and trust and makes it easier for students to contact them.

Other students offered similar opinions. They stressed the importance of the school nurse and other health professionals’ getting to know the students better. A student stated that it was important that the school nurse ‘make herself familiar to the students in the hallways, making it easier to take contact. There may be many students who need someone to talk to but do not dare’. In other words, familiarity with the student service staff was vital for improving the students’ help-seeking behaviours. Another student stated: ‘It would have been better if they [student services staff] were more visible and not just sitting in an office waiting for us to come.’ This was echoed by several students who stressed the importance of the health professionals’ increased visibility in the school: in the hallways and classrooms. However, availability is more than just meeting times and physical access. It includes an emotional component: the feeling of trust and safety for contacting and confiding in someone. A student stated: ‘I think it is very good to have student services because it gives the students someone to go to with our problems and who we feel has a true concern for us and can take proper care of our cases.’ However, there were some differences regarding whom the students found easiest to contact and to talk to. In addition, there were significant gender differences on two of the items as displayed in .

Table 2. How easy is it for you to talk to the following student services staff about mental health issues?

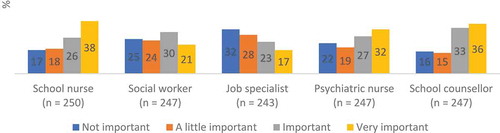

shows that students found it easiest to talk to the school counsellor or the school nurse. However, identifies that the boys seemed to find it easier to have these kinds of conversations. The data from the open-ended questions could not provide a deeper understanding of these gender differences; however, the qualitative findings indicate that having easy access to help when necessary and not having long waits for appointments with the school nurse or counsellor were essential to the students. Many students suggested the need for school nurse to be available at school every day. The extended student service pilot project has improved the resources to school nurse from two hours to one and a half day pr. week, but the students still don’t think this is enough.

Figure 3. Responses to the following question: how easy is it for you to talk to the following student services staff about mental health issues?

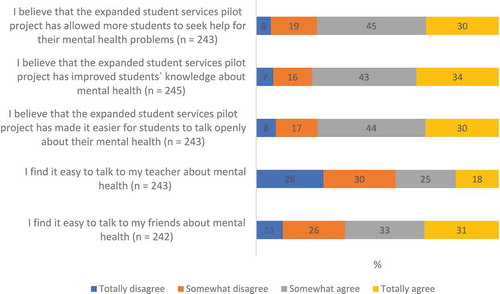

Finally, the students were asked a series of questions about their perceived effect of expanded student services and their own openness about mental health issues. The descriptive statistics are provided in .

Figure 4. Items regarding students perceived effect of expanded student services and their own openness about mental health issues

shows that approximately one third of the students totally agree that the expanded student services has (1) allowed more students to seek help for their mental problems, (2) improved students` knowledge about mental health and, (3) made it easier to talk openly about mental health issues. Also, students seem to find it a lot easier to talk to their friends rather than their teachers about mental health. However, T-tests identified significant gender differences for the scores on the item ‘I find it easy to talk to my teacher about mental health’: boys (M = 2.54, SD = 1.074) and girls (M = 2.02, SD = 0.984); t(219.929) = 3.927, p < .001. Thus, the boys found it easier to talk to their teachers. However, Levene’s test for equality of variances showed significance, thereby indicating that the variances within the two groups were not equal. For the rest of the items, no significant gender differences were identified.

Finally, a scale variable intended to measure the perceived effect of expanded student services was computed. The scale ‘Improved MHL’ comprised three variables from , intended to measure key aspects of MHL. These variables were: (1) I believe that the expanded student services pilot project has made it easier for students to talk openly about their mental health, (2) I believe that the expanded student services pilot project has improved students` knowledge about mental health and (3) I believe that the expanded student services pilot project has allowed more students to seek help for their mental health problems. The reliability of the scale was high (α = .871). Subsequently, the scale was included in a Pearson correlation test (r) to identify the possible co-variation between how easy the students found talking to their teachers and friends about mental health, and their perceived effect of expanded student services on their MHL. The results show that there was a medium strong, positive relationship between the variable ‘I find it easy to talk to my friends about mental health’ and the ‘Improved MHL’ scale, r = .32, n = 240, p < .001. The results also identify a medium strong, positive correlation between the scale and the variable ‘I find it easy to talk to my teacher about mental health’, r = 442, n = 239, p < .001.

Taken together, there was a medium strong correlation between the students’ perceived effects of expanded student services on MHL components such as openness and help-seeking behaviour, and their reported scores on talking about mental health with teachers and friends. The qualitative data conveyed a clear message about the influence of familiarity and accessibility on help-seeking behaviours.

Students’ suggestions for teachers to facilitate MHL

In order to facilitate openness about mental health, the students make it very clear that they want teachers and health professionals to take contact and ask them how they are coping; ‘If the teacher notices that a student is silent or not their “usual selves”, I want the teachers to ask a bit’. Some students may not have many friends to talk to at school; therefore, the teacher could become an important person in their everyday lives. A student stated: ‘Ask students how they are coping. All the students do not have someone to talk to at school, so it helps that at least one person talks to them.’ The students also appreciated professional secrecy among the student service personnel, making it easier to trust and confide in them. However, as one student put it, talking may not always be enough:

Focus on mental health is positive, but we are not as good to find solutions as we are to talk about problems. Perhaps the school can do something to actually improve the students’ mental health, for example, if it turns out to be the school that is the problem.

This quote points to the role of the school both as a risk and protective factor for mental problems. Even if the students recognize the importance of school performance, many of them stressed the importance of seeing them as ‘whole persons’ and not to focus solely on academics: ‘When you see that a student is tired and bored, do not push the student to learn, but, rather, talk about how they are coping.’ They also suggested talking about mental health in class. A student stated: ‘We can have an hour where the students can talk about mental health and explain to the teachers how we are doing so that the teachers can understand what it is like to be us.’ The students also suggested talking together in smaller groups.

Finally, some students mentioned the critical role of the teachers in facilitating help-seeking behaviour. For many, the teacher may be the first person they trust enough to confide in. Thus, the teacher’s encouraging them to seek professional help and, perhaps, accompanying them to the first appointment with the school nurse can be critical. As a student said: ‘Many students think it is embarrassing to visit the school nurse’. Another student indicated that it was easier to talk to the teacher and the student services staff than to the peers and parents: ‘It can be easier to talk to adults [at school] about your mental health problems instead of your own parents, as you do not want to burden them with this kind of information.’ This statement also highlighted the possible fear of ‘wearing others out’ when mental health problems are discussed. Consequently, students stated that collaboration between student services, teachers and parents is essential, and that they need to talk to each other in order to help the student.

In sum, the students made it very clear that they wanted teachers and health professionals to take contact and ask them how they are. Showing interest in their personal as well as academic life, make the students feel seen, build trust and encourage openness and help-seeking behaviour.

Discussion

With a focus on the key aspects of MHL (Kutcher et al., Citation2016), the current paper addressed two main research questions: (1) What is the perceived effect of expanded student services on students’ help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues? (2) What are the students’ suggestions for teachers to facilitate help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues?

The findings of this study indicate that the students were generally very positive about the student services and perceived them to be very important for their mental health and help-seeking behaviours. In the expanded services, new groups of professionals such as job specialists, social workers and psychiatric nurses have been introduced in school. Among these, the psychiatric nurses seem to be regarded as most central in terms of being available and make themselves familiar to the students. In general, these results confirm those of previous studies regarding the school as being the place where most students receive help for their mental health problems (Stiffman et al., Citation2004). For many students, the school is critical for facilitating their access to services regardless of their home backgrounds or socioeconomic status (Rothì et al., Citation2006). Moreover, school is an important site for increasing students’ MHL. This type of literacy encompasses learning about the location of resources, promoting positive mental health, managing mental health problems and illness, and decreasing the stigma associated with mental health issues (Jorm, Citation2012; Kutcher et al., Citation2016).

The findings also show that a large majority of the students (77%) believed that expanded student services had allowed them to increase their knowledge about mental health. In addition, 74% agreed that expanded student services had made it easier to talk openly about their mental health. However, the qualitative data indicate that the accessibility to health professionals such as school nurse and psychiatric nurse still need to be improved to facilitate help-seeking behaviour. The students stress the importance of student service staff to make themselves visible in school context and visit classrooms to inform students about their role. According to Tharaldsen et al. (Citation2017), inadequate knowledge about available school resources was identified as a major help-seeking barrier in upper secondary school.

Existing research indicate that teachers are somewhat peripheral to students when it comes to who they see as a potential source of help when they struggle with mental problems (Furnham et al., Citation2014). However, the present findings indicate that the school counsellor was regarded as the easiest person to talk to about mental health. Here it must be noted that the school counsellor also serves as a teacher and becomes well acquainted with the students through classroom interactions. In addition, the necessity for the counsellor to be the most accessible staff member for discussing mental health problems was highlighted (see ). This could be attributed to the sense of familiarity with the counsellor through the parallel teacher role.

Furthermore, MHL can be enhanced through teacher–student interactions, such as classroom and private conversations about mental health issues. The students were asked for suggestions for teachers to promote mental health. The very clear message from the students was the desire for the teachers to initiate more conversations with them and, specifically, to ask how they were coping not only academically but also socially. There were significant differences between the boys and the girls in that the boys found it easier to talk to health professionals and their teachers about mental health issues. This was an interesting finding that has not been well documented elsewhere and cannot be fully explained without further research. Previous studies on gender differences in help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues have concluded that girls are significantly more likely to seek help for their problems and to experience less stigma about mental health (Chandra & Minkovitz, Citation2007; Liddon et al., Citation2018). Research on the closeness of teacher–student relationships has revealed that girls reported significantly higher levels of closeness with their teachers than did boys (Drugli, Citation2013). More generally, Kidger et al. (Citation2009) indicated that students found talking to their teachers about mental health awkward, and preferred talking to health professionals. They also feared that the disclosure of problems could negatively affect their ‘academic’ relationship. The findings in this study contradict this to some degree, showing that students clearly want their teachers to ask them how they are coping. This does not necessary imply that students want to talk openly about their existing or emergent mental problems with their teachers. Still, by showing their concern and being open about mental health issues, teachers contribute to breaking down stigma and by this facilitate help-seeking behaviours (Mariu et al., Citation2012; Wilson et al., Citation2008). By showing interest in the students’ lives and build trustful relationships, teachers provide emotional support and make the students feel ‘seen’. This may also facilitate academic performance (Hamre & Pianta, Citation2005), and the responses to the open-ended questions indicate that such emotional support is important to many students. In addition, the present findings indicate that students appreciate having ‘professionals’ to talk to about mental health, making them less afraid of ‘wearing their friends out’ with their problems. Also, there is a problem of not having anyone to talk to (Anvik & Gustavsen, Citation2012; Idsøe et al., Citation2016). Through the extended student service project, the students’ perceived access to school nurses, psychiatric nurses and social workers seems to have improved, making it easier to find a trusted adult to confide in at school.

Conclusion

This study aimed to highlight the effects of expanded student services on student MHL, which was defined as general knowledge about help-seeking, knowledge about mental illness, the promotion of mental wellbeing and the reduction of mental health stigma. The two research questions facilitated the determination of students’ perceptions of the effects of the teacher–student relationship and expanded student services on their help-seeking behaviours and openness about mental health issues. The findings have highlighted the vital role of student services. The expanded student services have facilitated the students’ help-seeking, and they have also increased their knowledge and openness about mental health issues. However, teachers complement the student services through classroom- and private conversations, and the students still call for more resources to school nurse. However, the emotional support provided by showing genuine interest in the students’ lives and wellbeing is vital to the promotion of student mental health in the classroom. The students need to be well informed about the available services, and, more important, they need to feel comfortable with the staff. Therefore, it is important that school nurses and social workers visit classrooms and be available to students outside office and scheduled meeting hours.

Acknowledgments

Assistant Professor Reidunn Tvergrov Øye’s collaboration and inspirational conversations during the project are gratefully acknowledged. The students at the case school are recognized for participating in the study and sharing their thoughts and experiences. Finally, Volda University College’s provision of research and development resources for conducting the study is very much appreciated.

Disclosure statement

The author has no financial interest in and gains no benefit from the application of this research.

References

- Anvik, C. H., & Eide, A. K. (2011). De trodde jeg var en skulker, men jeg var egentlig syk. Ungdom med psykiske helseproblemer med svak tilknytning til skole og arbeidsliv [They thought I was a truant, but I was really sick]. Nordlandsforskning [Nordland Research Institute]. http://www.nordlandsforskning.no/getfile.php/Dokumenter/Rapporter/2011/Notat_1001_2011.pdf

- Anvik, C. H., & Gustavsen, A. (2012). Ikke slipp meg! - Unge, psykiske helseproblemer, utdanning og arbeid [Don’t let go of me!- Adolescents mental health problems, education and worklife]. Bodø: Nordlandsforskning [Nordland Research Institute]. http://www.nordlandsforskning.no/getfile.php/Dokumenter/Rapporter/2012/Rapport_13_2012.pdf

- Bjørnsen, H. N., Eilertsen, M.-E. B., Ringdal, R., Espnes, G. A., & Moksnes, U. K. (2017). Positive mental health literacy: Development and validation of a measure among Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4733-6

- Bjørnsen, H. N., Ringdal, R., Espnes, G. A., Eilertsen, M.-E. B., & Moksnes, U. K. (2018). Exploring MEST: A new universal teaching strategy for school health services to promote positive mental health literacy and mental wellbeing among Norwegian adolescents. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), N.PAG-N.PAG. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3829-8

- Buchanan, A., & Murray, M. (2012). Using participatory video to challenge the stigma of mental illness: Acase study. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 14(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2012.673894

- Chandra, A., & Minkovitz, C. (2007). Factors that influence mental health stigma among 8th grade adolescents. A Multidisciplinary Research Publication, 36(6), 763–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9091-0

- Clark, L. H., Hudson, J. L., Dunstan, D. A., & Clark, G. I. (2018). Barriers and facilitating factors to help‐seeking for symptoms of clinical anxiety in adolescent males. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70(3), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12191

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design. qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

- Danielsen, A. G., Samdal, O., Hetland, J., & Wold, B. (2009). School-related social support and students’ perceived life satisfaction. The Journal of Educational Research, 102(4), 303. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.102.4.303-320

- Drugli, M. B. (2013). How are closeness and conflict in student–Teacher relationships associated with demographic factors, school functioning and mental health in norwegian schoolchildren aged 6–13? Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.656276

- Funk, M., Drew, N., Freeman, M., Faydi, E., Van Ommeren, M., & Kettaneh, A. (2010). Mental health and development: Targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group World Health Organization (WHO). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44257/1/9789241563949_eng.pdf

- Furnham, A., Annis, J., & Cleridou, K. (2014). Gender differences in the mental health literacy of young people. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26(2), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2013-0301

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

- Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

- Helland, M. J., & Mathiesen, K. S. (2009). 13-15 åringer fra vanlige familier i Norge - hverdagsliv og psykisk helse [13-15-year-olds from ordinary families in Norway – Everyday life and mental health]. Folkehelseinstituttet [The Norwegian Institute of Public Health]. Retrieved from http://www.fhi.no/artikler/?id=73517

- Idsøe, E. C., Bru, E., & Øverland, K. (2016). Psykisk helse i skolen krever lærere med engasjement og emosjonelt overskudd. In E. Bru, E. C. Idsøe, & K. Øverland (Eds.), Psykisk helse i skolen [School mental health] (pp. 291–298). Universitetsforlaget.

- Johansson, A., Brunnberg, E., & Eriksson, C. (2007). Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260601055409

- Jones, A. C., Schinka, K. C., van Dulmen, M. H. M., Bossarte, R. M., & Swahn, M. H. (2011). Changes in loneliness during middle childhood predict risk for adolescent suicidality indirectly through mental health problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(6), 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.614585

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025957

- Kidger, J., Donovan, J. L., Biddle, L., Campbell, R., & Gunnell, D. (2009). Supporting adolescent emotional health in schools: A mixed methods study of student and staff views in England. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-403

- Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., & Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(3), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715616609

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2008). Qualitative data analysis: A compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 587. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.587

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2011). Beyond constant comparison qualitative data analysis: Using NVivo. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022711

- Liddon, L., Kingerlee, R., & Barry, J. A. (2018). Gender differences in preferences for psychological treatment, coping strategies, and triggers to help‐seeking. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12147

- Lillejord, S., Børte, K., Ruud, E., & Morgan, K. (2017). Stress i skolen - en systematisk kunnskapsoversikt [School stress - a systematic review]. www.kunnskapssenter.no

- Lund, T. (2005). A metamodel of central inferences in empirical research. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830500202918

- Lyngstad, G. D. (2000). Stigma og stigmatisering i psykiatrien – Et område som krever innsats? Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening,120(18)2178–2181. https://tidsskriftet.no/2000/08/kronikk/stigma-og-stigmatisering-i-psykiatrien-et-omrade-som-krever-innsats

- MacLean, A., Hunt, K., & Sweeting, H. (2013). Symptoms of mental health problems: Children’s and adolescents’ understandings and implications for gender differences in help seeking. Children & Society, 27(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00406.x

- Mariu, K. R., Merry, S. N., Robinson, E. M., & Watson, P. D. (2012). Seeking professional help for mental health problems, among New Zeeland secondary school students. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104511404176

- Menna, R., & Ruck, M. (2004). Adolescent help-seeking behaviour: How can we encourage it? Guidance & Counselling, 19(4), 176-183. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234678648_Adolescent_Help-Seeking_Behaviour_How_Can_We_Encourage_It

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2015). NOU 2015: 2 Å høre til. Virkemidler for et trygt psykososialt miljø [NOU 2015: 2 Belonging. Measures for a safe psychosocial environment]. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/35689108b67e43e59f28805e963c3fac/no/pdfs/nou201520150002000dddpdfs.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. (2014). Folkehelsemeldingen - mestring og muligheter. Meld. St. 19 (2014-2015) [Public Health Report - mastery and opportunities]. Kunnskapsdepartementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-19-2014-2015/id2402807/

- Moses, T. (2010). Being treated differently: Stigma experiences with family, peers, and school staff among adolescents with mental health disorders. Social Science & Medicine, 70(7), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.022

- Reavley, N. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2011). Stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: Findings from an Australian national survey of mental health literacy and stigma. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(12), 1086–1093. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.621061

- Rothì, D. M., Leavey, G., & McLaughlin, C. (2006). Mental health help-seeking and young people: A review. Pastoral Care in Education, 24(3), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0122.2006.00373.x

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. Freeman.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934563

- Sheppard, R., Deane, F. P., & Ciarrochi, J. (2018). Unmet need for professional mental health care among adolescents with high psychological distress. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417707818

- Skundberg‐Kletthagen, H., & Moen, Ø. L. (2017). Mental health work in school health services and school nurses’ involvement and attitudes, in a Norwegian context. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 5044–5051. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14004

- Stiffman, A., Pescosolido, B., & Cabassa, L. (2004). Building a model to understand youth service access: The gateway provider model. Mental Health Services Research, 6(4), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MHSR.0000044745.09952.33

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. SAGE.

- Tharaldsen, K. B., Stallard, P., Cuijpers, P., Bru, E., & Bjaastad, J. F. (2017). ‘It’s a bit taboo’: A qualitative study of Norwegian adolescents’ perceptions of mental healthcare services. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 22(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2016.1248692

- Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Giacco, D., Forsyth, R., Nebo, C., Mann, F., & Johnson, S. (2017). Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1451–1461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1

- Williams, J. H., Horvath, V. E., Wei, H.-S., Van Dorn, R. A., & Jonson-Reid, M. (2007). Teachers` perspectives of children`s mental health service needs in urban elementary schools. Children & Schools, 29 (2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/29.2.95

- Wilson, C. J., Deane, F. P., Marshall, K. L., & Dalley, A. (2008). Reducing adolescents’ perceived barriers to treatment and increasing help-seeking intentions: Effects of classroom presentations by general practitioners. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(10), 1257–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9225-z

- Wright, A., Jorm, A., & Mackinnon, A. (2012). Labels used by young people to describe mental disorders: Which ones predict effective help-seeking choices? The International Journal for Research in Social and Genetic Epidemiology and Mental Health Services, 47(6), 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0399-z