Abstract

Influencer marketing is a very important marketing strategy that builds its success on the strong link between influencers and their followers. A recent change in legislation obligates influencers to disclose if they are posting promotional content. Some studies indicate that such disclosures might dampen positive attitudes toward the promoted product as well as toward the influencer itself. With this study (N = 396 female participants), we investigate the effects of the sponsored partnership disclosure on Instagram compared to no disclosure and no brand depiction. As an addition to existing disclosure research, we furthermore explore the moderating role of similarity based on shared interests with the influencer. We manipulate the follower-influencer similarity by exposing our participants to one out of two influencers with a specific interest and by examining the interests of our participants in these topics. Findings suggest that disclosures can foster ad recognition. Disclosures can also lead to increased influencer trustworthiness when there is high follower-influencer similarity. Trustworthiness, in turn, affects purchase intentions for the advertised brand and future intentions to follow the influencer in a positive way.

Introduction

Today, marketers are often taking use of the far-reaching impact of social media influencers to promote their brands (Childers et al. Citation2019). Previous studies have indicated that employing influencers as brand endorsers can significantly increase consumers’ positive brand attitudes and purchase intentions (e.g., Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017). There are two reasons why influencer marketing is deemed to be so successful: First, the branded messages are often seamlessly woven into the content that influencers post on their social media accounts. Hence, this type of marketing increases the message authenticity and decreases the likelihood of message reactance (Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017). Second, recipients follow influencers they share interests with, thus feel similar to or strive to be like (Hoffner and Buchanan Citation2005; Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021). Therefore, influencers are perceived as ‘fashionable friends’ whose opinions his/her community is willing to follow (Colliander and Dahlén Citation2011).

The fairness of influencer marketing strategies has become an increasingly important issue. In particular, consumer advocacy groups have doubted that recipients can adequately understand the persuasive intent of influencer marketing strategies. Consequently, influencers in Western countries are now obligated to disclose paid or sponsored posts (e.g., EASA Citation2018). The impact of disclosing embedded or native advertising is thus a broadly discussed topic in advertising research (see for a meta-analysis on the topic Eisend et al. Citation2020). The main objective of disclosures is to make the advertising intent apparent to the audience, as it is the consumers’ right to know when they are targeted with persuasive messages (Boerman et al. Citation2018a). One of the main constructs in this research area is conceptual persuasion knowledge (PK), which is a multifaceted model that among other concepts includes the recognition of the persuasive intent (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; De Jans, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2018; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021). In fact, the effects of disclosing branded content on advertising recognition and how this in turn affects the advertised brands has been frequently studied (e.g., Beckert et al. Citation2020; Boerman et al. Citation2018a; Evans et al. Citation2017, Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016).

Yet, how denoting a branded post with a disclosure on social media or omitting such a disclosure affects the influencer’s trustworthiness has not been sufficiently examined. In general, existing studies have discussed the concepts of advertising recognition (Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Dhanesh and Duthler Citation2019; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021) and trustworthiness of the influencer separately (e.g., Colliander and Erlandsson Citation2015; De Veirman and Hudders Citation2020). However, the revelation that people have been confronted with sponsored content without a disclosure has been found to negatively affect the credibility of the communicator (Colliander and Erlandsson Citation2015). Trustworthiness of the communicator is thus a relevant factor in the persuasive process of influencer marketing and needs to be considered as such (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021). We therefore need to study the interplay of advertising recognition and trustworthiness of the communicator when explaining the outcomes related to the influencer (i.e., the effects on intention to follow the presented influencer) and the advertiser (i.e., the effects on purchase intention of the promoted brand). This marks a first relevant addition to the growing body of influencer marketing research.

Additionally, while source characteristics of influencers and the relationship of influencers to their followers are considered as very relevant (Enke and Borchers Citation2019), we lack empirical insights about the role of the relationship influencers have with their audience (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021). The key idea behind influencer marketing – that it is especially effective if it comes from a communicator the recipients like and feel related to (Childers et al. Citation2019) thus has not been sufficiently considered in empirical examinations. In this study, we therefore want to consider one aspect of para-social interaction (PSI) followers build with influencers they are confronted with. PSI describes the spontaneous response toward a media communicator such as an influencer in the moment of first exposure (Schramm and Hartmann Citation2008; Eyal and Dailey Citation2012). PSI this is built on first brief assessments of this communicator. One key factor that plays a role in this assessment is the perceived similarity between the audience and the influencer. This perceived similarity can be built on factors such as gender, origin, shared interests or mutual values (Hoffner and Buchanan Citation2005; see Mayrhofer and Matthes Citation2020). For the purpose of this study we specifically focus on shared interests as an indicator for similarity and we contribute to the existing literature (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021) by experimentally considering the moderating role of this similarity factor.

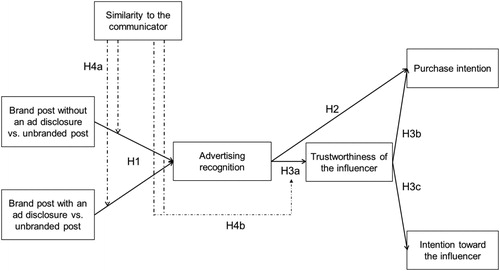

We thus conducted an experimental study manipulating the presence of embedded advertising and the absence and presence of a disclosure (i.e., no brand shown vs. brand shown without a disclosure vs. brand shown with a disclosure) on an influencer profile. We examined advertising recognition and trustworthiness of the influencer as our mediators and the effect of similarity between the audience and an influencer as our moderator. As outcome variables we focused on behavioral outcomes toward the promoted brand and the influencer itself.

Effects of branded post and disclosure

Influencer marketing has become a highly popular advertising technique, as marketers appreciate the cost-efficient possibility to reach a large portion of their target audience (Phua, Jin, and Kim Citation2017). There is also a rising research interest in the field of influencer marketing (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021) and the comprehension of this marketing technique (e.g., Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Dhanesh and Duthler Citation2019; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021, Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020). Instead of directly marketing their products or services, brands aim to encourage highly followed and admired influencers to endorse their products or services. Through this method, marketers indirectly advertise their brand by employing influencers as their electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM; Berger Citation2014). eWOM describes a social sharing between at least two users of online brand-related information and/or evaluation (Berger Citation2014) and is widely considered a very effective tool for marketers (King, Racherla, and Bush Citation2014). Marketers and researchers often attribute the persuasive power of eWOM to the perceived trustworthiness of the information or evaluation received by other users, as they, other than the brand itself, do not have an apparent reason to positively promote a brand (Willemsen, Neijens, and Bronner Citation2012). Yet, influencers are special types of users, who not only reach their close group of friends, but who can also distribute brand information and evaluation to a large circle of followers (Enke and Borchers Citation2019; Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021). Brands often compensate influencers for their connections to their followers, which commonly makes marketing a main source of income for influencers (Abidin Citation2016).

Hence, influencer marketing is a valuable option of outreach for marketers and the main source of income for influencers. Yet, regulators and consumer advocacy groups have increasingly questioned the fairness of this marketing technique toward the audience (see for instance Boerman et al. Citation2018a). Brand endorsements of influencers often are embedded seamlessly in the regular content of the influencers and rely heavily on the concept of the unbiased recommendation of a regular user (Willemsen, Neijens, and Bronner Citation2012), which potentially masks the persuasive intent. Yet, if influencers receive compensation for their postings and advertisers have control over the produced content, this form of marketing is required to comply with advertising regulations (EASA Citation2018). Hence, comparable to native advertising practices in journalistic contexts, influencers are obligated to disclose paid or sponsored posts with some type of disclosure (e.g., European Commission Citation2018).

The main objective behind these disclosures is to make the advertising intent apparent to the audience, as it is the consumer right to know when they are targeted with persuasive messages (Boerman et al. Citation2018a). Hence, one of the main constructs that has been investigated in extant research on disclosures is the recognition of the persuasive intent (e.g., Janssen et al. Citation2016; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). Researchers have mostly addressed the issue of influencer marketing by employing the construct of conceptual PK (e.g., Dhanesh and Duthler Citation2019; Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021) which is based on the Persuasion Knowledge Model by Friestad and Wright (Citation1994). Conceptual PK refers to the cognitive dimension that embodies the realization that a message actually is advertising. In addition, it conceptualizes the understanding of the persuasive intent, selling intent, and the necessary persuasive tactics (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012, p. 1049). Conceptual PK thus is a multifaceted construct that is built around advertising recognition but also gives insights into connected dimensions (Boerman et al. Citation2018b). Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) presume that consumers gradually develop knowledge about marketers’ attempts to persuade them as well as methods for coping with persuasive messages through regular exposure. Therefore, the mere presence of a persuasive message could be enough to trigger the audience’s conceptual understanding that they are targeted with an advertising message (Ahluwalia and Burnkrant Citation2004). Past studies indicate that disclosing sponsored content can help users to alert them to the fact that they are confronted with a persuasive message (Eisend et al. Citation2020), thus serve as a prime for users’ advertising recognition. This has been indicated for disclosures for embedded brands on TV (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012), in advergames (Van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2015), and on social media outlets (e.g., Beckert et al. Citation2020; De Jans, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2018; Evans et al. Citation2017). Thus, a large body of studies have pointed to the fact that disclosures on social media might be to a certain degree effective in increasing recipients’ advertising recognition. Yet, there is not necessarily a positive effect of advertising disclosures in influencer marketing on participants conceptual persuasion knowledge beyond advertising recognition (Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016). For instance, Lou, Ma, and Feng (Citation2021) indicate that participants who did not receive an advertising literacy intervention additional to an advertising disclosure were not able to activate their conceptual persuasion knowledge. Thus, it is not abundantly clear whether disclosures in influencer marketing are able to help participants to fully recognize the persuasive intent. As the existing body of literature still largely points to disclosures being effective in creating advertising recognition, we still assume that:

H1: A branded post with and without an advertising disclosure compared to an unbranded post heightens a user’s advertising recognition.

The realization that a message has a persuasive intent (i.e., the activation of users’ advertising recognition), is believed to have consequences for the further processing. This processing entails resistance strategies, and two main targets of these resistance strategies have been commonly identified (Fransen, Smit, and Verlegh Citation2015): First, users may start to critically contest the presented content itself. Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) suggest that identifying a communication as a persuasive message changes the meaning of this message. Thus, users might consider the identified persuasive attempt as an intrusion into the communication context which could (but not necessarily has to) have a negative effect on the evaluation of the message (Campbell and Kirmani Citation2008). Indeed, previous research has found conflicting results regarding the effect of advertising recognition on evaluative outcomes (e.g., Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). Still, being confronted with a persuasive message and realizing the persuasive intention is typically met with rejection (Colliander and Erlandsson Citation2015). The audience critically questions the content of the persuasive message, which in turn, can lead to a negative affective reaction against the content, hence the promoted brand (Hwang and Jeong Citation2016; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015). Furthermore, content that is identified as an advertising message oftentimes triggers negative attitudes such as annoyance and distrust which can further deteriorate the attitudes toward the presented brand (e.g., Mittal Citation1994).

Disclosures might therefore, based on reactance and negative attitudes triggered by persuasive messages, indirectly have a negative impact on advertiser’s intended brand outcomes (Zuwerink and Cameron Citation2003). As a relevant measure that gives insights into behavioral intention regarding the brand, studies have frequently considered purchase intention of the promoted brand as an outcome variable (e.g., Dhanesh and Duthler Citation2019; Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021). Based on existing research (Hwang and Jeong Citation2016; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015), we assume that activated advertising recognition could annihilate marketers’ intended outcomes such as purchase intentions (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012):

H2: A user’s advertising recognition activated by brand and disclosure presentations in an influencer’s post negatively affects the purchase intention of the promoted brand.

Second, users’ resistance strategies might be directly targeted at the source of the identified persuasive message (Fransen, Smit, and Verlegh Citation2015). In the case of influencer marketing, influencers are the source of the persuasive message. Thus, making the persuasive attempt being known through the use of a disclosure might lead to a descent of trust in the influencer due to activated persuasion knowledge. Trustworthiness is considered to be an important part of the effectiveness of eWOM, and therefore, what an influencer shares and how he/she might endorse brands, reflects back on the perceived trustworthiness of the communicator (Berger Citation2014). Within this context, Colliander and Erlandsson (Citation2015) point out that becoming aware of the persuasive intent of a message can deteriorate the trustworthiness of the communicator. Hence, the affective resistance strategies described above might also affect the influencers themselves.

Based on this line of argumentation, becoming aware of the persuasive intention of a post (i.e., advertising recognition) through branded posts or a disclosure could downgrade the trustworthiness of a communicator and the provided information (Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). We thus propose that advertising recognition can lead to a decrease in trust in the influencer. This may lead to a negative impact for the promoted brand (Willemsen, Neijens, and Bronner Citation2012) and have negative outcomes for the influencer’s interests. Hence, users might be reluctant to follow an influencer, which the users perceive to have been deceived by (Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015):

H3: A user’s advertising recognition activated by brand and/or disclosure presentations in an influencer’s post, (a) decreases the trustworthiness of the influencer which in turn reduces (b) the user’s purchase intention of the promoted brand, and (c) the user’s intentions toward the influencer.

The moderating role of similarity to the communicator

Previous studies have indicated that the audience is likely to interpret influencer endorsements as highly credible eWOM (e.g., King, Racherla, and Bush Citation2014). Thus, influencers are widely perceived to be more effective in creating positive brand outcomes than traditional advertising messages (Abidin Citation2016). Research indicates that use of influencers as brand endorsers can significantly increase consumers’ positive brand attitudes and purchase intentions (e.g., Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017). This is based on the close proximity of the advertising messages to the unsponsored content of the influencer (Abidin Citation2016), which potentially increases the message authenticity. On the other hand, the trustworthiness of the message builds on the para-social interaction (e.g., Kuan-Ju Chen and Jhih-Syuan Citation2020) the followers establish with an influencer.

Para-social interaction (PSI) is the illusion of a face-to-face relationship with a person one only knows through media contact (Horton and Wohl Citation1956). PSI is a theoretical concept originally applied for the relationship the viewers develop with TV-series characters. Yet, the regular content and the daily updates about often very private aspects of their lives (Abidin Citation2016), makes influencers the perfect ambit for the theoretical concept of PSI. PSI can take place in a single media exposure (Giles Citation2002) and encompasses the spontaneous response toward a communicator in the moment of first exposure (Schramm and Hartmann Citation2008, Eyal & Dailey Citation2012) yet the development of a deeper relationship only occurs if there are further media encounters (Giles Citation2002, p. 288).

Studies have indicated that influencers appear very approachable and hence can create feelings of familiarity, comparable to a friend in real life (e.g., Colliander and Dahlén Citation2011). The audience commonly establishes PSI with media characters they perceive as similar to themselves or characters the audience members wish they could be (Hoffner and Buchanan Citation2005). Hence, sharing similarities with an influencer (e.g., regarding interest and lifestyle) is an important aspect that researchers need to consider when investigating the impact of influencer marketing. This is because testimonials are particularly trustworthy when their persona is perceived to be similar to the target audience (e.g., Chang Citation2011; Feick and Higie Citation1992). A recent study on influencer marketing supports this assumption. Results indicate that perceived similarity with an influencer indeed affects trust in the communicator as well outcomes of promoted brands (Lou and Yuan Citation2019). Hence, the existing literature points toward similarity being an important factor when investigating the processing of persuasive messages. Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman (Citation2021) thus also include the user’s similarity to an influencer as a key factor in their conceptualization of strategic use of influencer marketing.

If we perceive other communicators as similar to ourselves, this potentially makes them more persuasive (Feick and Higie Citation1992). This is because brand information provided by a similar person is typically considered as more authentic and believable compared to, for instance, a promotional message by the company itself (Willemsen, Neijens, and Bronner Citation2012). When we assume that people similar to us (i.e., other people like us) do not have a monetary reason to positively promote a brand online (King, Racherla, and Bush Citation2014), we might not expect a persuasive intent. In other words, as we see other users as similar to ourselves, we do not automatically expect a persuasive intent, when they talk about brands. This, in turn, is considered to increase the trustworthiness of the communicator. Especially if the audience feels like somebody is sharing their interests and values, their recommendations and opinions are likely to come across as more trustworthy (Feldman Citation1984; Feick and Higie Citation1992):

H4a: High similarity based on shared interest between an influencer and their audience decreases advertising recognition activated by brand and/or disclosure presentations in an influencer’s post; (b) this in turn increases the trustworthiness of an influencer.

For all hypotheses and the research question, see the conceptual model in .

Method

We conducted an online-survey experiment. We manipulated the similarity with the communicator with two different accounts (fashionista vs. environmentalist) and the presence/absence of embedded advertising as well as presence/absence of a disclosure (no brand posts vs. brand posts without a disclosure vs. brand posts with a disclosure).

Participants

For our online-survey experiment we recruited a convenience sample of 396 women between the age of 18 to 60 (M = 24.13; SD = 4.47). We decided to keep the gender of our participants constant as this is an additional factor that might impact the perceived user-influencer similarity.

Stimulus and study design

Similarity with the communicator

To manipulate the similarity with the communicator, we created two different influencer accounts. We base similarity on shared interests which can be characterized as ego-based similarity (see Cohen, Weimann-Saks, and Mazor-Tregerman Citation2018). We portrayed one influencer to be an environmentalist; the other influencer we portrayed to be a fashionista. We chose these types of accounts as (a) influencers that promote fashion topics are very common and are often employed as influencers (Kulmala, Mesiranta, and Tuominen Citation2013), and (b) to provide two topics where it can be assumed that following these accounts is not necessarily based on the same interests and views. For instance, influencers who promote sustainability typically tend to take a stance against fast fashion and luxury fashion and therefore can be perceived as somewhat of a counterpart to a fashionista’s account (Bly, Gwozdz, and Reisch Citation2015).

To create the environmentalist’s and the fashionista’s account, we manipulated (a) the written information about the influencer in the accounts (b) the different filler posts used for the accounts, and (c) the hashtags of the filler posts. We kept the name, the profile picture, and the age of the influencer as well as the number of likes, comments, and followers equal between conditions (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017). For details on the stimulus material, see Appendix A.

To assess whose interests (the environmentalist’s or the fashionista’s interests), participants aligned with, they were given a short questionnaire prior to the account exposure. This questionnaire recorded the participants’ attitudes regarding fashion and environmental topics. To assess importance of fashion topics, we asked four questions (e.g., ‘Dressing fashionably is an important part of my life’; 1 = ‘I don’t agree’; 7 = ‘I completely agree’; α = .82; M = 4.54; SD = 1.24). Importance of environmentalist topics were also measured by four items (e.g., ‘Protecting the environment is very important to me’ 1 = ‘I don’t agree’; 7 = ‘I completely agree’; α = .81; M = 5.41; SD = 1.00).

After answering these questions, the women were randomly assigned to either the account of the fashionista (n = 185) or the environmentalist (n = 211). To establish the respondents’ similarity to the communicator, we mean-centered the importance of fashion respectively environmental topic. We then calculated an interaction term of the mean-centered importance of the topic and the corresponding account. In a next step, we summated these interaction terms to obtain a moderator variable indicating the similarity to the communicator (ranging from low similarity = −4.41 to high similarity = 2.46; M = −0.01; SD = 1.14). We were therefore able to assess the effects of similarity on a continuum. As the differences in the two types of accounts (fashionista vs. environmentalist) might elicit main effects we did not consider (e.g. as different types of profiles are used for different reasons and therefore evaluated differently, Kaye and Johnson Citation2011), we included the dummy coded-variable of the two accounts as a control in all analyses.

Pre-test

To ensure that our intended manipulation of similarity was appropriate we conducted a pre-test with N = 38 female participants similar to the sample of the main study (Mage = 25.03; SD = 6.07). We used the same stimulus and procedure regarding the assessment of similarity as described above (importance of fashion topics: α = .79; M = 4.63; SD = 1.23; importance of environmentalist topics: α = .65; M = 4.57; SD = 1.00). To examine whether our procedure can be deemed effective in manipulating the similarity to the influencer, we assessed participants’ perceived similarity to the communicator. We measured this construct based on four items (e.g., ‘Sara of saras_blog…’ 1 = ‘does not act like me’; 7 = ‘acts like me’; α = .95; M = 3.43; SD = 1.65; based on Chang Citation2011).

We tested the effectiveness of our manipulation. Results showed that participants who regarded fashion topics to be important also perceived themselves to be similar to the influencer when they had seen the fashionista’s account (n = 24; r = .72, p = .004). This relationship however did not occur for those who had seen the environmentalist’s account (n = 24; r = −.07, p = .757). Vice versa, participants who regarded environmental topics to be important perceived themselves to be similar to the environmentalist. However, this relationship did only approach significance (n = 14; r = .37, p = .076). Again, we found no significant association between the importance of environmental topics and perceived similarity if they had seen the fashionista’s account (n = 14; r = .39, p = .165). Due to the limited sample size and small statistical power, we still regarded the manipulation of similarity as successful and therefore employed this design in our main study.

Brand and disclosure occurrence

To manipulate the brand occurrence and the disclosure we created three different conditions: (a) The influencer did not mention or depict any brands on her feed (control group; n = 137). The influencer mentioned and depicted the brand Herbivore Botanical either (b) without (no disclosure condition; n = 123) or (c) with the standard Instagram disclosure (‘Sponsored Partnership with BRAND’ - disclosure condition; n = 136). All branded posts showed the same brand - Herbivore Botanical which is a real cosmetic brand that is not popular or well-known in Austria. We chose this product as it is one the one hand promoted as a natural cosmetic in recyclable and reusable packages which makes it a likely fit for the environmentalist but on the other hand Herbivore Botanical is a cosmetic brand and as a lifestyle and beauty product it also has a fit to the fashionista account.

Participants first saw a screenshot of the Instagram profile and then clicked through the individual posts containing ten filler-posts and four brand-posts, which were presented in a fully randomized order. The control group saw only the ten filler posts and no additional branded posts. While we picked the filler posts to match the specific influencers’ topic (fashion content for the fashionista and nature images for the environmentalist), we kept the brand posts constant.

Measures

Mediators

Subsequent to stimulus exposure, we measured participants’ advertising recognition with four items (e.g., ‘This Instagram profile …’ 1 = ‘contained no advertising content’; 7 = ‘contained advertising content’; α = .85; M = 4.12; SD = 1.67; based on Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012). The influencer’s trustworthiness was measured by asking the participants to assess eight statements on a 7-point differential scale (e.g., ‘The influencer I just saw was…’ 1 = ‘not trustworthy’; 7 = ‘trustworthy’; α = .91; M = 4.40; SD = 1.21; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015).

Dependent variables

We measured participants’ purchase intention of the promoted brand. This was measured with four statements (e.g., ‘I would like to try a product by Herbivore Botanical’; 1 = ‘I don’t agree’; 7 = ‘I completely agree’; α = .89; M = 2.92; SD = 1.46; based on van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016). We included the intentions directed toward the influencer assessed by the intention to follow this influencer (three statements; e.g., “I would follow the account ‘saras_blog’” 1 = ‘I don’t agree’; 7 = ‘I completely agree’; α = .94; M = 2.70; SD = 1.57; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015) as our second dependent variable.

For a full list of all employed ‘measures see the Appendix B. For a descriptive analysis of these four measures stratified by our experimental conditions, see .

Table 1. Descriptive Analysis

Results

Manipulation check

To test the effectiveness of our similarity manipulation, we followed the same procedure as in the pre-test. We examined whether the participants perceived similarity to the communicator correlated with the importance of fashion topics, respectively environmental topics in the according accounts. We thus measured ego-based similarity as a key (and one possible) dimension of similarity (Cohen, Weimann-Saks, and Mazor-Tregerman Citation2018). Results indicate that our manipulation can be deemed successful (fashionista: correlation of perceived similarity to the influencer with the importance of fashion topics: n = 185; r = .34, p < .001; environmentalist: correlation of perceived similarity to the influencer with the importance of environmental topics: n = 211; r = .17, p = .016). The adverse type of influencer and set of interests did not correlate (p > .05).

Randomization check

Randomization checks for age (F (5, 390) = 0.62; p = .687), using Instagram (F (5, 390) = 1.25; p = .284), and the importance of Instagram (F (5, 390) = 0.40; p = .847) were successful.

Descriptive results and main effects

We calculated bivariate correlations of our conceptualized moderator, mediator and dependent variables. The results can be found in . In addition, we ran a MANOVA with our experimental conditions (control group, disclosure condition, and no disclosure condition) as the independent factors, and advertising recognition, trustworthiness of the influencer, purchase intention and intention toward the influencer as our dependent variables. As can be observed in , our control condition showed significantly lower levels of advertising recognition, and significantly higher levels of trustworthiness of the influencer compared to both the brand post with a disclosure and without a disclosure. Furthermore, the control group and the brand post with a disclosure had significantly higher intentions toward the influencer then the condition with a branded post without a disclosure. A disclosure compared to no disclosure also significantly increased both advertising recognition and the trustworthiness of the influencer.

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations

Table 3. MANOVA

Statistical model

We tested our proposed moderated mediation model with intention toward the influencer and purchase intention of the advertised brand as the dependent variables. We examined our two dependent variables in two separate models. We treated advertising recognition and trustworthiness of the influencer as the successive mediators, and similarity with the influencer as a moderator, using SPSS Macro PROCESS, Model 85 involving 1,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes Citation2018). The control condition that did not show any brand occurrences served as our reference group. Furthermore, we included our second manipulated factor, the type of account (fashionista = 1 vs. environmentalist = 0), as a control variable in all analyses.

Full model

Advertising recognition

With regard to our H1, we found that participants in both brand conditions (with and without a disclosure) had a significantly higher level of advertising recognition compared to the control condition showing no brand posts (disclosure condition: b = 1.94, p < .001; LLCI = 1.62; ULICI = 2.27; no disclosure condition: b = 1.36, p < .001; LLCI = 1.02; ULICI = 1.69). Interestingly, the type of account also influenced advertising recognition, as participants who saw the fashionista’s account had a significantly higher level of advertising recognition compared to participants who saw the environmentalist’s account (b = 0.86, p < .001; LLCI = 0.60; ULICI = 1.14). However, neither similarity to the influencer nor the interaction of the similarity with our experimental conditions did affect advertising recognition. This leads us to reject our H4a.

Regarding the effectiveness of the disclosure on advertising recognition, we computed the same model but inserted the no disclosure condition as our reference group. A brand post with a disclosure significantly increased participant’s advertising recognition even more than a sole brand presentation without a disclosure (b = 0.58, p < .001; LLCI = 0.25; ULICI = 0.92). We did not observe any additional main or indirect effects.

Trustworthiness of the influencer

As hypothesized (H3a) advertising recognition negatively affected the perceived trustworthiness of the influencer (b = −0.35, p < .001; LLCI = −0.42; ULICI = −0.28). Beyond this hypothesized relationship we found that compared to the control condition showing no branded posts a direct negative effect of the no disclosure condition on trustworthiness of the influencer could be observed (b = −0.46, p < .001; LLCI = −0.73; ULICI = −0.19). Hence, an undisclosed brand presentation decreased the trustworthiness of an influencer. This direct effect was also observed when comparing the no disclosure condition to the disclosure condition. Thus, presenting brands with a disclosure had a positive impact on the trustworthiness of the influencer while showing brands without the disclosure is perceived as a preach of trust (b = 0.58, p < .001; LLCI = 0.32; ULICI = 0.83). No direct effects of the disclosure condition compared to the control condition with no branded content on trustworthiness of the influencer was observed (b = 0.12, p = .411; LLCI = −0.17; ULICI = 0.40).

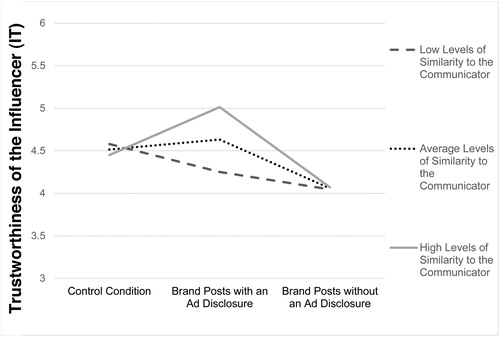

Connected to H4b, we found a moderation effect with similarity to the communicator (b = 0.39, p < .001; LLCI = 0.17; ULICI = 0.61): compared to the control condition, brand posts with a disclosure increased the trustworthiness of the influencer if participants were similar to the communicator. This effect also held up compared to the no disclosure condition (b = 0.32, p < .001; LLCI = 0.11; ULICI = 0.54). As H4b expected a moderated mediation path through advertising recognition and not a direct moderation effect on trustworthiness, H4b only finds partial support. For an illustration of the interaction effect, see .

Purchase intention

Regarding the intention to buy the promoted brand, we did not observe a direct (H2) nor a mediated negative effect (H3b) of advertising recognition elicited through brand occurrence or the use of a disclosure (b = 0.09, p = .112; LLCI =- 0.02; ULICI = 0.20). Thus, H2 and H3b are not supported. However, we observed a positive main effect of the trustworthiness of the influencer on the intention to buy the product (b = 0.39, p < .001; LLCI = 0.25; ULICI = 0.52). Furthermore, when treating the control condition with no brand presentations as a reference group, similarity to the influencer directly increased purchase intention of the target brand (b = 0.28, p = .010; LLCI = 0.07; ULICI = 0.49). This direct relationship however did not hold up when treating the no disclosure condition as the reference group (b = 0.11, p = .275; LLCI = −0.09; ULICI = −0.31). This result therefore indicates that if an influencer who is similar to the users shows a brand and a disclosure, this presentation compared to no brand presentation at all can assert a positive effect on purchase intention.

When examining the moderated mediation path of the disclosure condition compared to the control condition showing no brand presentations, we observed that the positive effect of the high similarity with the influencer on perceived trustworthiness also translated on to the purchase intention (b = 0.21; LLCI = 0.06; ULICI = 0.41). Not being presented with a disclosure however deteriorated participants’ trust which for low (b = −0.21; LLCI = −0.38; ULICI = −0.07) and average levels of similarity (b = −0.18; LLCI = −0.30; ULICI = −0.07) also translated on to the purchase intention of the brand compared to the control group that showed no branded content. When comparing the no disclosure condition to the disclosure condition, average (b = 0.23; LLCI = 0.12; ULICI = 0.38) and high levels of similarity (b = 0.36; LLCI = 0.19; ULICI = 0.56) also asserted positive indirect effects on purchase intention.

Intentions toward the influencer

Regarding intentions directed toward the influencer, we found that compared to the no disclosure condition intentions toward the influencer were higher in both the control condition (b = 0.40; p = .029; LLCI = 0.04; ULICI = 0.75) and the disclosure condition (b = 0.48; p = .006; LLCI = 0.14; ULICI = 0.82). The perceived trustworthiness of the influencer furthermore had a positive direct effect on the intention toward the influencer when treating the no disclosure condition as a reference group (b = 0.63; p < .001; LLCI = 0.50; ULICI = 0.76). We also observed this effect when comparing the disclosure condition to the control condition. We found no other main or indirect effects. However, when treating the no disclosure condition as the reference group, being similar to the communicator had a positive interaction effect in the disclosure condition (b = 0.28; p = .048; LLCI = 0.00; ULICI = 0.56). This means that the intention to follow the influencer could be positively impacted when transparency measures for branded messages were provided.

When examining the moderated mediation pathway of the conditions via trustworthiness of the influencer on the effects of the intention toward the influencer, we found that, compared to the no disclosure condition, the positive effect on the trustworthiness of the influencer translated onto a positive effect toward the intentions to follow the influencer for all levels of similarity (control condition: b = 0.29; LLCI = 0.11; ULICI = 0.48; disclosure condition: b = 0.36; LLCI = 0.19; ULICI = 0.55). Yet compared to the control condition, the intention to follow the influencer in the disclosure condition was only mediated by the trustworthiness of the influencer for high levels of similarity with the communicator (b = 0. 34; LLCI = 0.10; ULICI = 0.63). This lends partial support to H3c. For all results in detail, see .

Table 4. Full Model

Discussion

As influencers can exert a tremendous impact on their followers, they can help to positively shape the image of brands and products. Such a platform, however, also comes with a certain need to act in responsible and transparent ways. Consequently, researchers and consumer advocacy groups have called for clear rules about what should be regarded as advertising in influencer communication and what not. In that context, disclosures have become a timely and important topic for advertising scholars (Boerman et al. Citation2018a). In fact, previous studies have shown that disclosures can increase advertising recognition, which may then negatively affect brand outcomes (e.g., Evans et al. Citation2017). However, disclosures may not only affect dimensions of PK, they may also shape the perceived trustworthiness of an influencer and the relationship between these variables may be more complex than previously thought.

In this paper, we have tested the effects of disclosures on advertising recognition, influencer trustworthiness as well as future intentions toward the influencer and the brand (i.e., purchase intentions). First, our findings show that brands on social media can foster advertising recognition, especially when they are disclosed (e.g., Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). This gives indications that disclosures in influencer marketing can successfully increase concepts of conceptual PK (Evans, Hoy, and Childers Citation2018; Lou, Ma, and Feng Citation2021; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016). Interestingly, we found that not only whether or not a brand or disclosure was shown affected the participants’ advertising recognition, but also the topic of the post shaped the awareness for the presence of sponsored content. Specifically, we found that participants in the fashionista account condition activated their advertising recognition to a higher extent compared to the environmentalist account condition. This indicates that certain topic content might be more likely to be connected with persuasive intent than other content. We assume that the content of a fashionista might be more strongly related to consumerism than content of an environmentalist which might explain this result. This is an interesting finding, which highlights that future research should include the factor of the topic of the account in experimental designs.

At first glance, the results that disclosure heighten advertising recognition might suggest that disclosures impede positive brand outcomes as disclosing sponsored content was connected to reduced brand attitudes in the past (Eisend et al. Citation2020). However, as our findings around influencer trustworthiness have demonstrated, this is clearly not the case. There was a parallel effect path suggesting potential positive effects of disclosing ads.

In fact, our results suggest that a disclosure of a brand occurrence can have a positive impact, both for the advertised brand as well as the influencer who posts the brands. More specifically, we showed that disclosures can increase influencer trustworthiness in case the influencers are similar to the followers. Such increased trustworthiness, then, shapes purchase intentions toward the brand and future following intentions with respect to the influencer. With our study, we therefore indicate that transparency is appreciated (for similar results see Campbell and Evans Citation2018) as well as that the similarity between the users and the communicators matter and can have important consequences. In other words, our results point out that when there is high similarity, disclosures are taken as a cue for an influencer’s trustworthiness. Similarity itself is arguably related to trustworthiness (e.g., Feldman Citation1984). Thus, in the state of high similarity, trustworthiness is easily primed with a disclosure because there is already a positive predisposition. In other words, when we feel similar to a person, transparency additionally reminds us about the trustworthiness of that person. The disclosure is automatically interpreted in positive ways. When there is low similarity, however, a disclosure is not treated as a cue for trustworthiness. In that case, a person behaves in transparent ways, but that does not automatically serve as a prime.

When interpreting these findings, it is important to note that we manipulated similarity in an experiment. This was necessary in order to understand the process behind similarity as well as its effects. In addition, we argued that the experimental manipulation of similarity systematically addresses the fact that users often have a para-social interaction or even relationships with an influencer. Thus, using a random or unknown influencer in a typical experimental study may lead us to erroneous or incomplete conclusions (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021). Of course, we have no data about the degree to which followers feel similar to the influencers they chose to follow. Yet it can be argued that similarity will be high rather than low for most influencers. In fact, one could argue that influencers are so successful because they can provide their audience with the impression of similarity (Willemsen, Neijens, and Bronner Citation2012). Therefore, the effects of similarity in the real world of influencers may be even larger than the present study suggests.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, while we were able to address the limitations in external validity of experimental studies on social media by examining the role of similarity to the consumer to some extent, our manipulation still falls short to examine the long-lasting and complex relationship between an influencer and his/her followers (Horton and Wohl Citation1956). We need longitudinal study designs to go beyond examining the factor of PSI and get insights about the role of long-lasting relationships between influencers and their audience, that is, parasocial relationships (Schramm and Hartmann Citation2008). Second, our measurement of conceptual PK focused on the aspect of advertising recognition. As conceptual PK is a multifaceted construct, examining this aspect more thoroughly seems warranted (Boerman et al. Citation2018b). Third, we only examined the proposed relationship for female participants. We decided for this procedure, based on internal validity concerns regarding the manipulation of similarity. Fourth, in our study, we only employed two different types of accounts (fashionista vs. environmentalist). Even though these types of accounts are common (Bly, Gwozdz, and Reisch Citation2015), they do not live up to the variety of accounts that exist. Connected to that we only focused on interest similarity based on these two topics and did not include any other similarity aspects. Furthermore, we only examined one product type. Yet, in addition to the fit between the influencer and its audience which we examined in this paper, influencer–product fit is also an important factor (De Cicco, Iacobucci, and Pagliaro Citation2020; Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2021) which we did not consider in this study. Thus, future studies should (a) examine long-term effects (b) consider both genders to test whether the examined relationships hold for both, men and women, and (c) take additional similarity dimensions and product dimension into account.

Implications

These limitations notwithstanding, our results have several implications. Our findings indicate that even though brand occurrences increase advertising recognition, and as a consequence, may decrease the trustworthiness of the influencers, adding a disclosure can level out these negative effects. In fact, when followers feel similar to the influencers, disclosures can increase the trustworthiness of the influencer, which in turn, has positive consequences for the influencers themselves and for marketers. We would therefore recommend that influencers comply with the established regulations and that marketers be adamant in their negotiations with influencers and their agencies that adequate disclosures are employed. As the existing regulations are primarily addressed at native advertising and journalism public policy makers should explicitly include influencer marketing. Disclosing brands on social media may thus be regarded a win-win situation for all involved parties: Consumers are provided with the transparency they deserve, influencers can be perceived as trustworthy, and marketers are still be able to transport their messages. Although more research is needed to bolster these claims, our results should further encourage influencers to add disclosures to their messages involving persuasive content.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (4.2 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Brigitte Naderer

Brigitte Naderer (PhD, University of Vienna) is a Post-Doc at the Department of Media and Communication, LMU Munich, Germany. She holds a PhD in Journalism and Communication Studies (2017) and a MA in Political Science. Her main research interests focus on persuasive communication, advertising literacy, and advertising effects on children.

Jörg Matthes

Jörg Matthes (PhD, University of Zurich) is professor of communication science at the Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. He chairs the division of advertising research and media effects. His research focuses on advertising effects, the process of public opinion formation, news framing, and empirical methods.

Stephanie Schäfer

Stephanie Schäfer (MA, University of Vienna) was a master student at the University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. Her master thesis dealt with advertising disclosures on Instagram.

References

- Abidin, C. 2016. “Aren’t these just young, rich women doing vain things online?”: Influencer selfies as subversive frivolity. Social Media + Society 2: 1–17.

- Ahluwalia, R., and R. E, Burnkrant. 2004. Answering questions about questions: A persuasion knowledge perspective for understanding the effects of rhetorical questions. Journal of Consumer Research 31, no. 1: 26–42.

- Beckert, J., T. Koch, B. Viererbl, and C. Schulz-Knappe. 2020. The disclosure paradox: How persuasion knowledge mediates disclosure effects in sponsored media content. International Journal of Advertising. (Online-First).

- Berger, J. 2014. Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, no. 4: 586–607.

- Bly, S., W. Gwozdz, and L. A. Reisch. 2015. Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 39, no. 2: 125–35.

- Boerman, S. C., N. Helberger, G. van Noort, and C. J. Hoofnagle. 2018a. Sponsored blog content: What do the regulations say: And what do bloggers say. Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and Electronic Commerce Law 9: 146–59.

- Boerman, S. C., E. A. van Reijmersdal, and P. C. Neijens. 2012. Sponsorship disclosure: Effects of duration on persuasion knowledge and Brand responses. Journal of Communication 62, no. 6: 1047–64.

- Boerman, S. C., E. A. van Reijmersdal, E. Rozendaal, and A. L. Dima. 2018b. Development of the persuasion knowledge scales of sponsored content (PKS-SC). International Journal of Advertising 37, no. 5: 671–97.

- Boerman, S. C., L. M. Willemsen, and E. P. Van Der Aa. 2017. This post is sponsored”: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of facebook. Journal of Interactive Marketing 38: 82–92.

- Campbell, C., and N. J. Evans. 2018. The role of a companion banner and sponsorship transparency in recognizing and evaluating article-style native advertising. Journal of Interactive Marketing 43: 17–32.

- Campbell, M. C., and A. Kirmani. 2008. I know what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. Handbook of Consumer Psychology 549–574.

- Chang, C. 2011. Opinions from others like you: The role of perceived source similarity. Media Psychology 14, no. 4: 415–41.

- Childers, C. C., Lemon, L. L. and M. G., Hoy. 2019. # Sponsored# Ad: Agency perspective on influencer marketing campaigns. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 40, no. 3: 258–274.

- Cohen, J., D. Weimann-Saks, and M. Mazor-Tregerman. 2018. Does character similarity increase identification and persuasion?Media Psychology 21, no. 3: 506–28.

- Colliander, J., and M. Dahlén. 2011. Following the fashionable friend: The power of social media: Weighing publicity effectiveness of blogs versus online magazines. Journal of Advertising Research 51, no. 1: 313–20.

- Colliander, J., and S. Erlandsson. 2015. The blog and the bountiful: Exploring the effects of disguised product placement on blogs that are revealed by a third party. Journal of Marketing Communications 21, no. 2: 110–24.

- De Cicco, R., S. Iacobucci, and S. Pagliaro. 2020. The effect of influencer–product fit on advertising recognition and the role of an enhanced disclosure in increasing sponsorship transparency. International Journal of Advertising: 1–27. (Online-First).

- De Jans, S., V. Cauberghe, and L. Hudders. 2018. How an advertising disclosure alerts young adolescents to sponsored vlogs: The moderating role of a peer-based advertising literacy intervention through an informational vlog. Journal of Advertising 47, no. 4: 309–25.

- De Veirman, M., V. Cauberghe, and L. Hudders. 2017. Marketing through instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on Brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising 36, no. 5: 798–828.

- De Veirman, M., and L. Hudders. 2020. Disclosing sponsored instagram posts: The role of material connection with the Brand and message-sidedness when disclosing covert advertising. International Journal of Advertising 39, no. 1: 94–130.

- Dhanesh, G. S., and G. Duthler. 2019. Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public Relations Review 45, no. 3: 101765.

- Djafarova, E., and C. Rushworth. 2017. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior 68: 1–7.

- EASA. 2018. EASA best practice recommendation on influencer marketing. Available at: https://www.easa-alliance.org/sites/default/files/EASA%20BEST%20PRACTICE%20RECOMMENDATION%20ON%20INFLUENCER%20MARKETING_2020_0.pdf (Accessed Jan 04, 2021).

- Eisend, M., E. A. van Reijmersdal, S. C. Boerman, and F. Tarrahi. 2020. A Meta-analysis of the effects of disclosing sponsored content. Journal of Advertising 49, no. 3: 344–66.

- Enke, N., and N. S. Borchers. 2019. Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework for strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13, no. 4: 261–277.

- European Commission. 2018. Behavioural study on advertising and marketing practices in online social media. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/behavioural-study-advertising-and-marketing-practices-social-media-0_en

- Evans, N. J., M.G. Hoy, and C.C. Childers. 2018. Parenting “YouTube natives”: The impact of pre-roll advertising and text disclosures on parental responses to sponsored child influencer videos. Journal of Advertising 47, no. 4: 326–46.

- Evans, N. J., J. Phua, J. Lim, and H. Jun. 2017. Disclosing instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising 17, no. 2: 138–49.

- Eyal, K., and R. M. Dailey. 2012. Examining relational maintenance in parasocial relationships. Mass Communication and Society 15, no. 5: 758–781.

- Feick, L., and R. A. Higie. 1992. The effects of preference heterogeneity and source characteristics on ad processing and judgements about endorsers. Journal of Advertising 21, no. 2: 9–24.

- Feldman, R. H. 1984. The influence of communicator characteristics on the nutrition attitudes and behavior of high school students. Journal of School Health 54, no. 4: 149–51.

- Fransen, M. L., E. G. Smit, and P. W. Verlegh. 2015. Strategies and motives for resistance to persuasion: An integrative framework. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1–12.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research 21, no. 1: 1–31.

- Giles, D. C. 2002. Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology 4, no. 3: 279–305.

- Hayes, A.F. 2018. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A Regression-Based approach. New York: Guilford Press

- Hoffner, C., and M. Buchanan. 2005. Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: The role of perceived similarity and character attributes. Media Psychology 7, no. 4: 325–51.

- Horton, D., and R. Wohl. 1956. Mass communication and Para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 19, no. 3: 215–29.

- Hudders, L., S. De Jans, and M. De Veirman. 2021. The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising 40, no. 3: 327–375.

- Hwang, Y., and S. H. Jeong. 2016. This is a sponsored blog post, but all opinions are my own”: The effects of sponsorship disclosure on responses to sponsored blog posts. Computers in Human Behavior 62: 528–35.

- Janssen, L., M. L. Fransen, R. R. Wulff, and E. A. van Reijmersdal. 2016. Brand placement disclosure effects on persuasion: The moderating role of consumer self-control. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15, no. 6: 503–15.

- Kaye, B. K., and T. J. Johnson. 2011. Hot diggity blog: A cluster analysis examining motivations and other factors for why people judge different types of blogs as credible. Mass Communication and Society 14, no. 2: 236–63.

- King, R. A., P. Racherla, and V. D. Bush. 2014. What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Interactive Marketing 28, no. 3: 167–83.

- Kuan-Ju Chen, Y.S., and L. Jhih-Syuan. 2020. When social media influencers endorse brands: The effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. International Journal of Advertising 39: 590–610.

- Kulmala, M., N. Mesiranta, and P. Tuominen. 2013. Organic and amplified eWOM in consumer fashion blogs. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 17, no. 1: 20–37.

- Liljander, V., J. Gummerus, and M. Söderlund. 2015. Young consumers’ responses to suspected covert and overt blog marketing. Internet Research 25, no. 4: 610–32.

- Lou, C., W. Ma, and Y. Feng. 2021. A sponsorship disclosure is not enough? How advertising literacy intervention affects consumer reactions to sponsored influencer posts. Journal of Promotion Management 27, no. 2: 278–305.

- Lou, C., and S. Yuan. 2019. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising 19, no. 1: 58–73.

- Matthes, J., and B. Naderer. 2016. Product placement disclosures: Exploring the moderating effect of placement frequency on Brand responses via persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 35, no. 2: 185–99.

- Mayrhofer, M., and J. Matthes. 2020. Observational learning of the televised consequences of drinking alcohol: Exploring the role of perceived similarity. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 37, no. 6: 557–575.

- Mittal, B. 1994. Public assessment of TV advertising: Faint praise and harsh criticism. Journal of Advertising Research 34: 35–54.

- Phua, J., S. V. Jin, and J. J. Kim. 2017. Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social Capital: A comparison of facebook, twitter, instagram, and snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior 72: 115–22.

- van Reijmersdal, E. A., M. L. Fransen, G. van Noort, S. J. Opree, L. Vandeberg, S. Reusch, F. van Lieshout, and S. C. Boerman. 2016. Effects of disclosing sponsored content in blogs: How the use of resistance strategies mediates effects on persuasion. American Behavioral Scientist 60, no. 12: 1458–74.

- Van Reijmersdal, E. A., N. Lammers, E. Rozendaal, and M. Buijzen. 2015. Disclosing the persuasive nature of advergames: Moderation effects of mood on Brand responses via persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 34, no. 1: 70–84.

- Willemsen, L. M., P. C. Neijens, and F. Bronner. 2012. The ironic effect of source identification on the perceived credibility of online product reviewers. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 18, no. 1: 16–31.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and N. J. Evans. 2016. Going native: Effects of disclosure position and language on the recognition and evaluation of online native advertising. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 2: 157–68.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and N. J. Evans. 2020. The covert advertising recognition and effects (care) model: Processes of persuasion in native advertising and other masked formats. International Journal of Advertising 39, no. 1: 4–31.

- Zuwerink, J., and K. A. Cameron. 2003. Strategies for resisting persuasion. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 25, no. 2: 145–61.