Abstract

Infrastructure and technological advancements mark a change in the nature and the extent of surveillance practices, which have become central in the advertising landscape. These new developments come with their own ethical ramifications for the industry, consumers, and regulators. The current article reviews the current state of advertising ethics and surveillance by examining the role and interplay of the industry, consumers, and regulators. We present a future research agenda in which we call for more research into the ethical consequences of the omnipresent surveillance in advertising regarding the changes in the advertising landscape, and new theoretical and methodological implications.

Introduction

Developments in digital technologies have greatly transformed the landscape of advertising around the world. The technical possibilities and low costs of collection and processing of consumer data have led to the domination of the landscape by digital data-driven advertising (e.g. personalized advertising, social media advertising, computational advertising, Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning). While past research on this type of advertising has mostly focussed on examining consumer privacy concerns (see Boerman and Smit in this special issue), the surveillance by advertisers who collect consumers’ information such as their name and demographic information, monitor their behaviours such as online searches, location, and media consumption with the purpose to inform or persuade consumers, raises a number of broader ethical issues. From the industry perspective, it comes with new responsibilities regarding data safety as well as ethical deployment of data-driven practices. From the consumer perspective, such surveillance can have (unintended) ethical side-effects, such as limiting consumers’ autonomy online (Büchi, Festic, and Latzer Citation2022) and creating new divides and vulnerabilities (Finn and Wadhwa Citation2014). From the regulators perspective, surveillance poses new ethical challenges that require additional levels of protection for consumers (Helberger et al. Citation2020).

Advertising ethics, which is defined as ‘what is right and good in the conduct of the advertising function. It is concerned with questions of what ought to be done, not just what legally must be done’ (Cunningham Citation1999, p. 500), has a long tradition in advertising research (e.g. Nevett Citation1985; Hailey Citation1989) with International Journal of Advertising as one of the main contributors with topics, such as advertising to children, stereotyping, advertising questionable products (e.g. tobacco, alcohol), and impacts on consumer well-being (Hyman, Tansey, and Clark Citation1994; Gilbert et al. Citation2021). Surveillance has become a new prominent ethical issue in contemporary advertising. To continue the contribution of the International Journal of Advertising (IJA) on advertising ethics scholarship (see online appendix for an overview of IJA publications), we present an overview of the ethical ramifications of surveillance in advertising including a research agenda.

Theoretically, this article will contribute to building our understanding of digital advertising ethics and surveillance by reviewing the current state and proposing a future research agenda on this topic. Practically, this article will contribute to ethics in the advertising industry and how to handle consumer data in a responsible manner. Surveillance has a potentially negative impact on the relationship between consumers and companies that collect their data and process it for advertising purposes. This negative impact goes beyond privacy violations and stems from broader ethical and societal consequences of surveillance for advertising purposes such as impact on individual autonomy, increasing inequality, and facilitating manipulation (Finn and Wadhwa Citation2014). Possible unintended effects of corporate surveillance might impact attitudes and behaviour of consumers and hence be detrimental to the quality of data collected as consumers change their behaviour, provide false information or take protective measures to avoid surveillance (i.e. the data potentially does not reflect true user preferences), which lowers the effectiveness of data-driven advertising. Finally, understanding ethics and surveillance is important for regulators, particularly if their aim is to protect and empower consumers in the face of data collection and to ensure that digital data-driven advertising benefits all actors in the advertising landscape.

Ethics and surveillance in advertising

Surveillance by the industry on their consumers has long existed, such as keeping records on consumers through loyalty programs and trading consumer characteristics in the direct marketing sector (Christl Citation2017). Infrastructure and technological advancements mark a change in the nature and extent of surveillance practices (Manokha Citation2018), such as the internet, and later social media and smartphones (Christl Citation2017). It has changed the possibilities of surveillance; it allows for the continuous automated collection, storage, and processing of unspecified digital traces, which is also known as dataveillance (Büchi, Festic, and Latzer Citation2022). Examples are the Facebook Pixel or Google’s _gac cookie that facilitate data collection of online browsing information when people visit a website that has this pixel/cookie installed (Van Gogh et al. Citation2021). We distinguish between different types of consumer data, namely zero- (i.e. data voluntarily given by consumers), first- (i.e. data collected by organization), second- (i.e. another organisation’s first party data), and third-party data (i.e. data bought from a data management platform) (Yun et al. Citation2020). These data are collected, processed, and stored with the purpose to optimize communications efforts by, for example, retargeting, sending personalized advertisements or personalized promotions to consumers (Van Gogh et al. Citation2021; Yun et al. Citation2020).

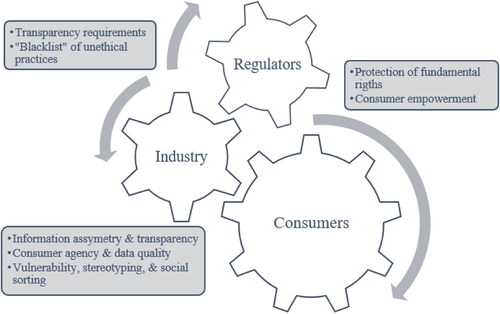

Different theories have been used to explain effects of personalized advertising and data collection practices (for an overview see Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017). However, frameworks that could explain digital ethics and surveillance are limited. The Transparency-Awareness-Control Framework (Segijn et al. Citation2021) provides a starting point for studying the interaction between transparency of (surveillance) practices and consumer control. Additionally, this framework and the Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers Citation1975) could provide guidance to further understand consumer empowerment in this context. Finally, Büchi, Festic, and Latzer (Citation2022) proposes the theory of the chilling effects of dataveillance that can be applied to study ethical side effects of dataveillance. Although these frameworks touch upon some digital ethical issues (e.g. transparency, self-censorship), other issues (e.g. information asymmetry, vulnerability) are not included (). An integrated framework regarding digital ethics and surveillance could help to further our understanding of the topic. Additionally, new technological developments come with their own ethical questions to be considered by the industry and that have implications for consumers and regulators (). We will discuss some current issues in the next section.

The advertising industry

The industry has a responsibility to collect, store, and process consumer information ethically. For ethical decisions, advertisers should concern themselves with the intention, the actions, and the consequences of the actions (Carrigan and Szmigin Citation2000). An ethical code could help the employees to understand what the organisation and industry expect but without reinforcement and implementation of the management it could lead to a false sense of security (Chonko, Hunt, and Howell Citation1987).

With the increased centrality of consumer data (Malthouse and Copulski in this special issue), broader ethical questions have been gaining importance (Strycharz et al. 2019), such as social sorting (i.e. classifying people based on criteria to target for special treatment, suspicion, eligibility, or inclusion; Lyon Citation2002). In the advertising context it, for example, involves explicitly not targeting certain groups due to their lower income and has been described as social discrimination (Turow Citation2012). Such practices do not only exclude consumers from information but may also reinforce existing stereotypes and lead to social exclusion (European Data Protection Authority Citation2013).

Drumwright and Murphy (Citation2009) identified transparency as an important theme regarding advertising ethics. Transparency in the relation to personalized advertising is ‘the degree of disclosure of the ways in which firms collect, process, or share (exchange) personal data’ (Segijn et al. Citation2021, p. 123), which is the responsibility of the sender (e.g. advertiser) but could impact the receiver (e.g. consumer). A lack of transparency impacts the extent to which consumers can make informed decisions regarding their personal information. Transparency is required in some privacy regulations (Degeling et al. Citation2019) but with the increasing self-regulation of the industry it is largely their own responsibility to be transparent about the practices (Helberger et al. Citation2020). Transparency is not always the solution, for example, because of consumers’ limited understanding of data collection practices and consequences, information overload, default options, and false perceptions of control (Van Ooijen and Vrabec Citation2019). Additionally, for unethical practices (e.g. exploitation of vulnerabilities) it might be better to avoid these practices altogether (Helberger et al. Citation2021).

The consumer

The centrality of consumer data in surveillance practices has given consumers both more and less control and agency. On the one hand, consumers have become more influential because they generate the data, which are critical for the algorithmic processes behind advertising (Helberger et al. Citation2020; Yun et al. Citation2020). For example, consumers may turn to avoiding certain activities so that data on them is not collected by the industry. These self-censorship practices of consumers are an ethical consequence of surveillance by external parties (e.g. government, advertisers), because they interfere with consumers’ agency and their right to informational self-determination (Büchi, Festic, and Latzer Citation2022; Finn and Wadhwa Citation2014). Furthermore, when data are directly shared by consumers, they can purposefully provide inaccurate information to mislead the industry (Yun et al. Citation2020).

On the other hand, the centrality of consumers for surveillance does not automatically translate to agency as users are limited in their control of data flows (Helberger et al. Citation2020), for example, because of information asymmetry between them and the surveillant (Marwick Citation2012). Research shows that consumers have a lack of knowledge on surveillance techniques, such as cookies (Smit, Van Noort, and Voorveld Citation2014), which calls for more advertising literacy to empower consumers. Additionally, a consumer who is capable of making informed decisions in one situation might not have the time or cognitive resources to do this in another. For example, when consumers are under time pressure (e.g. I have to find the nearest hospital now), when they are ego depleted, or are under (financial) stress, they may accept tracking cookies/user agreements to quickly access online information that they otherwise might not (see Helberger et al. Citation2021 for individual biases perspective on the informed consent approach).

Regulations

In the context of surveillance and advertising, regulators aim to empower consumers by providing them with extensive rights and by requiring industry to offer transparency and choices regarding data collection and processing (Degeling et al. Citation2019). The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) introduced in the European Union (EU) in May 2018 is of central relevance to digital advertising ethics. This regulation aims to empower consumers who are given a high degree of control over their data online, which should fulfill their fundamental right to the protection of their personal data. Additionally, the regulation puts high requirements for data controllers and processors who are obliged to inform consumers about collecting and using their data for advertising purposes (Li, Yu, and He Citation2019). The regulators can thus potentially have substantial impact on both consumers and the industry.

Additionally, a potential solution is defining practices that would be forbidden in all circumstances. Such a ‘black list’ of specifically defined commercial practices that are deemed unfair under all circumstances is already present in the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive of the EU (which also applies to advertising; Strycharz and Duivenvoorde Citation2021 Strycharz et al., Citation2019). A similar blacklist could be created for unethical computational advertising practices that exploit consumer vulnerabilities and exercise psychological or emotional pressure through targeting such as ‘using psychographic profiles to exercise emotional and psychological pressure with the goal of selling products’ (Helberger et al. Citation2021, p. 145).

Future research agenda

Changes in the advertising landscape come with new questions that future research should focus on, as well as new theoretical and methodological implications. Below, we present a future research agenda on digital advertising ethics and surveillance that deserves attention in future International Journal of Advertising publications.

Technological developments

With new technologies, new ethical issues arise (Drumwright and Murphy Citation2009). Future research should look into the affordances of new technologies that could raise new ethical questions Think about technologies that allow extension of surveillance to the private sphere through cameras or microphones (e.g. mobile devices, augmented reality, smart devices), outdoor advertising that changes based on who is passing by, and facial recognition software. Additionally, developments in AI come with new ethical questions (Helberger and Diakopoulos Citation2022), such as who is accountable for actions taken by chatbots (Dignum Citation2018).

Consumer vulnerability

Certain groups of consumers are more susceptible to unfair commercial practices than others and less able to protect themselves (Rozendaal in this special issue). We propose to define digital vulnerability beyond group membership as vulnerability can be individual and contextual (i.e. stemming from the situation one is in, such as external circumstances that lead to distress; Helberger et al. Citation2021). This is particularly relevant for computational and personalized advertising as insights gained from consumer data can be used to render individuals vulnerable in a certain context, for example, by using information on one’s psychographic profile in online interactions. Therefore, future research needs to investigate to what extent modern advertising and targeting practices contribute to reinforcing and creating new types of digital vulnerabilities. We should rethink advertising literacy programs by examining who is vulnerable in what situations, and how to protect them in that situation.

Industry players

With the centrality of data, any business entity that generate revenues from consumer data and advertising should be considered a part of the new advertising industry (Helberger et al. Citation2020). Thus, technology firms that provide technology necessary for online advertising are now part of the industry. In particular, this category includes (1) hardware companies that responsible for electronic devices through which consumers access media (e.g. smart speakers or watches) that function as data collection points; (2) companies responsible for technological support necessary for online advertising; and (3) data aggregating companies that provide technological support in converting potential audience views into ad exposure and effects (Helberger et al. Citation2020). The role and the monopoly of a limited number of technology firms offering such services raises ethical questions. For example, Facebook and Google found a way to work around the blocking of third-party data by web browsers (e.g. Safari) by having hosting websites install the pixel or _gac cookie, which makes data collected through these methods now first-party data (Van Gogh et al. Citation2021).

Theoretical and methodological implications

We call for more theory building on this topic, which could be a combination of applying existing theories to new contexts (see ‘ethics and surveillance in advertising’ above), extending them, or developing new theories. Additionally, for researchers who do not have access to the same data as the industry does, it is challenging to measure consumers’ responses to surveillance for advertising and to examine consequences of it. To keep up with the industry, researchers have to start using digital analytics (e.g. social media analytics, see Yun, Pamuksuz, and Duff Citation2019) to move beyond measuring motivations and intentions. Researchers can cooperate with the industry to gain access to digital trace data (e.g. Social Science One program aimed at partnerships between academic researchers and the private sector, including a partnership with FacebookFootnote1). However, such collaborations are not free from their own challenges, among others related to the full power of the industry over the data and access to it (a more detailed discussion of such controversies, see e.g. Hegelich Citation2020). Alternatively, researchers can develop new methods to collect their own digital behavioural data, for example by asking consumers to donate their digital trace data (Araujo et al. Citation2021).

International perspective

Finally, we call for international perspectives on the topic of ethics and surveillance. Given the difference in privacy regulations (e.g. stricter privacy regulations such as the GDPR in the EU and less governmental intervention in the U.S.), we could also expect different data collection practices and impacts on consumers. For example, in a situation where consumers feel protected by the regulations, they may not feel the need to take additional protective measures themselves (e.g. self-censorship, privacy protection). While self-censorship might be more prevalent when this protection or trust in institutions is not present. Finally, countries and cultures may differ in their perceptions of ethics, agency, and autonomy. To get a better understanding of surveillance and ethics, different regulatory and cultural perspectives are needed.

Conclusion

In sum, the role of surveillance in the advertising landscape has increased over the years and taken on new forms. The centrality of consumer data brings new ethical challenges with impacts for the industry, the consumers, and regulators. Because of, on the one hand, an information asymmetry between consumers and the industry, and on the other hand, the potential power consumers have to stop data collection processes, the interplay between the industry and consumers has gained complexity. We call for more research into the ethical consequences of the omnipresent surveillance in advertising regarding the changes in the advertising landscape, and theoretical and methodological implications. The challenge for practitioners and research still ‘lies in improving the effectiveness of actions designed to reduce unethical activity’ (Chonko, Hunt, and Howell Citation1987, p. 273).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.1 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding to report.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed for the current manuscript.

Notes

References

- Araujo, T., J. Ausloos, W. van Atteveldt, F. Loecherbach, J. Moeller, J. Ohme, … K. Welbers. 2021. OSD2F: An open-source data donation framework.

- Boerman, S. C., S. Kruikemeier, and F. J. Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2017. Online behavioral advertising: A literature review and research agenda. Journal of Advertising 46, no. 3: 363–76.

- Büchi, M., N. Festic, and M. Latzer. 2022. The chilling effects of digital dataveillance: A theoretical model and an empirical research agenda. Big Data & Society 9, no. 1: 205395172110653.

- Carrigan, M, and I. Szmigin. 2000. The ethical advertising covenant: Regulating ageism in UK advertising. International Journal of Advertising 19, no. 4: 509–28.

- Chonko, L. B., S. D. Hunt, and R. D. Howell. 1987. Ethics and the American advertising federation principles. International Journal of Advertising 6, no. 3: 265–74.

- Christl, W. 2017. Corporate surveillance in everyday life. https://crackedlabs.org/en/corporate-surveillance

- Cunningham, P.H. 1999. Ethics of Advertising. In The advertising business, ed. John Philip Jones, 499–513. London: Sage.

- Degeling, M., C. Utz, C. Lentzsch, H. Hosseini, F. Schaub, and T. Holz. 2019. We value your privacy. Now take some cookies: Measuring the GDPR’s impact on web privacy. In Proceedings 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium:1-20. San Diego, California, USA.

- Dignum, V. 2018. Ethics in artificial intelligence: Introduction to the special issue. Ethics and Information Technology 20, no. 1: 1–3.

- Drumwright, M. E, and P. E. Murphy. 2009. The current state of advertising ethics. Journal of Advertising 38, no. 1: 83–107.

- European Data Protection Authority. 2013. Opinion 03/2013 on purpose limitation. https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2013/wp203_en.pdf

- Finn, R. L, and K. Wadhwa. 2014. The ethics of “smart” advertising and regulatory initiatives in the consumer intelligence industry. info 16, no. 3: 22–39.

- Gilbert, J. R., M. B. Stafford, D. A. Sheinin, and K. Pounders. 2021. The dance between darkness and light: A systematic review of advertising’s role in consumer well-being (1980-2020). International Journal of Advertising 40, no. 4: 491–528.

- Hailey, G. D. 1989. The federal trade commission, the Supreme Court and restrictions on professional advertising. International Journal of Advertising 8, no. 1: 1–5.

- Hegelich, S. 2020. Facebook needs to share more with researchers. Nature 579, no. 7800: 473–4.

- Helberger, N, and N. Diakopoulos. 2022. The European AI act and how it matters for research into AI in media and journalism. Digital Journalism. Online First. 1–10.

- Helberger, N., J. Huh, G. Milne, J. Strycharz, and H. Sundaram. 2020. Macro and exogenous factors in computational advertising: Key issues and new research directions. Journal of Advertising 49, no. 4: 377–93.

- Helberger, N., O. Lynskey, H.-W. Micklitz, P. Rott, M. Sax, and J. Strycharz. 2021. EU Consumer Protection 2.0. Structural asymmetries in digital consumer markets. A joint report from research conducted under the EUCP2.0 project. Retrieved from https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2021-018_eu_consumer_protection.0_0.pdf

- Hyman, M. R., R. Tansey, and J. W. Clark. 1994. Research on advertising ethics: Past, present, and future. Journal of Advertising 23, no. 3: 5–15.

- Li, H., L. Yu, and W. He. 2019. The impact of GDPR on global technology development. Journal of Global Information Technology Management 22, no. 1: 1–6.

- Lyon, D. 2002. Surveillance as social sorting: Computer codes and mobile bodies. In Surveillance as social sorting, ed. David Lyon: 27–44. London: Routledge.

- Manokha, I. 2018. Surveillance, panopticism, and self-discipline in the digital age. Surveillance & Society 16, no. 2: 219–37.

- Marwick, A. E. 2012. The public domain: Social surveillance in everyday life. Surveillance & Society 9, no. 4: 378–93.

- Nevett, T. 1985. The ethos of advertising. F.P. Bishop reconsidered. International Journal of Advertising 4, no. 4: 297–304.

- Rogers, R. W. 1975. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology 91, no. 1: 93–114.

- Segijn, C. M., J. Strycharz, A. Riegelman, and C. Hennesy. 2021. A literature review of personalization transparency and control: Introducing the transparency-awareness-control framework. Media and Communication 9, no. 4: 120–33.

- Smit, E. G., G. Van Noort, and H. A. Voorveld. 2014. Understanding online behavioural advertising: User knowledge, privacy concerns and online coping behaviour in Europe. Computers in Human Behavior 32: 15–22.

- Strycharz, J., G. Van Noort, N. Helberger, and E. Smit. 2019. Contrasting perspectives – practitioner’s viewpoint on personalised marketing communication. European Journal of Marketing 53no.4: 635–60. doi:10.1108/EJM-11-2017-0896.

- Strycharz, J, and B. B. Duivenvoorde. 2021. The exploitation of vulnerability through personalised marketing communication: Are consumers protected? Internet Policy Review 10, no. 4: 1–27.

- Turow, J. 2012. The daily you. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- van Gogh, R., M. Walrave, and K. Poels. 2021. Personalization and digital marketing: Implementation strategies and the corresponding ethical issues. In The SAGE handbook of marketing ethics, eds. Lynne Eagle, Stephan Dahl, Patrick De Pelsmacker & Charles R. Taylor. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Van Ooijen, I, and H. U. Vrabec. 2019. Does the GDPR enhance consumers’ control over personal data? An analysis from a behavioural perspective. Journal of Consumer Policy 42, no. 1: 91–107.

- Yun, J. T., U. Pamuksuz, and B. R. Duff. 2019. Are we who we follow? Computationally analyzing human personality and brand following on twitter. International Journal of Advertising, 38, no. 5: 776–95.

- Yun, J. T., C. M. Segijn, S. Pearson, E. C. Malthouse, J. A. Konstan, and V. Shankar. 2020. Challenges and future direction of computational advertising measurement systems. Journal of Advertising 49, no. 4: 446–58.