ABSTRACT

Focusing on three of the Central and Eastern European countries – Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary – the paper investigates the evolution of spatial planning systems and the introduction of strategic planning practices from the beginning of the post-communist transition in the early 1990s to the present. It sheds new light on this issue by applying the conceptual lens of historical institutionalism to explain this process and elucidate the role of the accession to the European Union (EU) as a catalyst for change. In particular, the paper identifies and analyses the critical junctures at which path dependencies emerged and later constrained the capacity of the regional and local actors to adjust to the EU Cohesion Policy framework and engage in strategic planning as part of it.

Introduction

While planning is not a competence of the European Union (EU), in practice the organization has put in place several initiatives, concepts, and policies that influence spatial planning practices and systems in the EU member and candidate states. One of these measures is the European Spatial Development Perspective,Footnote1 which was an attempt by the EU to promote the spatial planning approach and stimulate an integrated thinking about the impacts of EU policies on the territory,Footnote2 a topic covered also by Faludi in this issue. Another is the notion of territorial cohesionFootnote3 – as some scholars argue, a concept close to that of spatial planningFootnote4 understood as ‘formulating integrated strategic spatial frameworks to guide public as well as private action’Footnote5 – which at present is one of the goals of the EU alongside economic and social cohesion. Finally, there is the Cohesion Policy (CP), which is the EU’s main instrument to pursue territorial, social and economic cohesion, by providing funding to support regional and urban development through a complex multi-level governance system, involving authorities at various territorial scales.Footnote6 It is upon this aspect of the EU’s influence on the planning practice on the ground in the EU candidate and member states that this paper will focus.

EU CP has been associated with the promotion of institutional and policy changes in the present and prospective EU member states.Footnote7 One aspect of the domestic impact of this policy is the promotion of strategic, long term and place-based approaches to economic development at the different levels of government through the multi-annual planning requirements.Footnote8 The programming principle requires EU CP spending to be based on operational programmes covering periods of seven years, designed by national and regional authorities managing the EU funds. A substantial share of the Structural Funds (SF) is disbursed via Regional Operational Programmes (ROPs), which are to support the pursuit of regional development strategies. Over time, EU CP framework has been reformed to become more strategically focused and ‘place-based’, in line with the OECD’s new regional development policy paradigm according to which every region has opportunities for growth and development that can be exploited through a place-tailored measures.Footnote9

However, the actual ability to use EU funding programmes to support regional and local development strategies depends largely on administrative capacity of sub-national authorities. The latter is one of the key barriers to the implementation of EU CP and varies significantly not only across the EU Member States but also within them.Footnote10

This paper endeavours to shed light on the capacity of regional and local authorities to employ EU funding to support place-based development strategies, which remains relatively under-researched. Conceptually, it imports ideas from political science, following from the Europeanisation literatureFootnote11 (which is concerned with the impacts of the EU and its policies on sub-national actors), but mainly building on historical institutionalism.Footnote12 The latter school of thought strives to explain continuity and change of institutions over time, chiefly using the notion of path dependency. Historical institutionalism has been widely used to study institutional and policy change, mainly in the field of public policy and political science. However, it has remained somewhat underused in the literature on spatial planning,Footnote13 despite its potential to provide a sound theoretical framework for studying planning history and for shedding light on the departures from the historically established paths and embedded ways of doing things. By using this approach, one can examine why the outcomes of Europeanisation processes differed between countries. This differentiation has been flagged up in previous research on the domestic impacts of EU CP, particularly in Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) that have joined the EU since 2004.Footnote14 This paper does so by focusing on historical decisions that lock institutional and policy developments into particular paths and on the critical junctures at which external or domestic events may push the developments towards a new path by changing (a) the actors’ strategic calculus about the change or (b) by modifying their cognitive templates and interpretations through learning.

Thus, the paper, first, investigates what was the influence of the EU and its CP on the emergence of strategic planning at the regional and local levels in CEECs and strives to explain variation in the outcomes of this process across them. Second, it examines the extent to which the pathways of transition towards market economy and liberal democracy after 1989 as well as towards membership in the EU have shaped and constrained the process of Europeanisation of planning practices at the regional and local levels. In order to answer those questions, the paper draws on three case studies of regions from Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary.

EU CP and strategic planning

Strategic ‘spatial planning’ refers to the processes of development strategy building that are closely intertwined with regional policy and other policies that have territorial impacts like, for example, environmental policy.Footnote15 Therefore, it is an important tool for designing place-based economic development strategies. Spatial planning in the European context is often associated with spatial development policy, concerned with shaping the ‘geographical distribution of features in the built and natural environment and patterns and flows of human activity’ and reducing the ‘geographical disparities in socio-economic conditions and life chances of citizens’.Footnote16

The literature on Europeanisation of spatial planning, that is of the influence of the EU on domestic spatial planning practices, has grown from the mid-1990s onwards. This happened in response not just to the conceptual emergence of European spatial planning and, subsequently, the establishment of the ESDP in 1999,Footnote17 but also the development of EU policies that affect domestic sectoral policies the impacts of which matter for spatial development.Footnote18

Despite the negative connotations of ‘planning’ in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe, frequently associated with communist-era central planning,Footnote19 since the early 1990s, spatial planning in CEECs has been developing, driven by the preparations for future EU membership and the implementation of EU CP.Footnote20 While the pressures for these changes emanating from the EU were similar for all of the EU accession candidate countries and to a degree these countries shared similar communist regimes’ legacies, the actual adjustment of planning practices to the CP framework followed different trajectories, reflecting different institutional settings and planning traditions.Footnote21

Most of the studies considering Europeanisation of planning focus on the influence of the ESDP,Footnote22 territorial cooperationFootnote23 or discursive notions such as territorial cohesionFootnote24 as instruments for diffusion of European norms and practices. However, there is a shortage of research looking at the impact of EU CP on planning practices, even though it has been an important driver for changes in strategic planning, particularly in CEECs. In fact, since 2004 the SF have provided those countries with unprecedented amount of developmental funding, while at the same time triggering major institutional and policy reforms, including strategic, integrated and place-based approaches to regional and local development. As Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel put it,

East European acceding countries showed a greater willingness to open up the national spatial planning debate to the European meta-discourse and the spatial principles associated therewith. Of course the role played by financial incentives from the European structural funds is not to be underestimated here.Footnote25

In practice, however, the application of the EU CP rules in CEECs is often ‘superficial’ and inconsistent in general,Footnote27 particularly in the planning realm.Footnote28 The governance reforms undertaken prior to accession focused on the establishment of a decentralized (or at least de-concentrated) territorial administration and regional policies in line with the EU CP framework, but relatively little attention was paid to the issue of strategic planning.Footnote29

Historical institutionalism as a conceptual lens

The historical institutionalism strand of institutionalist literature, which is concerned with how institutions persist or change over time, was used in this research to explain the stages and the outcomes of the processes of Europeanisation of strategic spatial planning in CEECs. Historical institutionalists define institutions as ‘formal or informal procedures, routines, norms and conventions embedded in the organizational structure of the polity or political economy’.Footnote30 This approach, used in political science to explain ‘stickiness’ of institutions and policies and the difficulties in reforming them, is surprisingly seldom used in the planning literature. As Sorensen argues, however, the approach can offer a particularly useful theoretical framework for studying change and continuity in planning systems in a comparative perspective.Footnote31 In particular, historical institutionalism, concerned with sequence and patterns of institutional development, can help to avoid the pitfalls of comparative research in urban and planning studies that contrast developments in economically and politically similar contexts.

The central concept in historical institutionalism is ‘path dependence’. It ‘characterizes specifically those historical sequences in which contingent events set into motion institutional patterns or event chains that have deterministic properties’.Footnote32 The underlying idea is that ‘once established, some institutions tend to become increasingly difficult to change over time, and so small choices early on can have significant long-term impacts’.Footnote33 However, this contention should not be reduced to claiming that history matters. Historical institutionalism is also concerned with how history matters and the mechanisms that result in this stickiness or durability of institutions. To shed light on these mechanisms, the notion of positive feedback effects is put forward, whereby actors benefitting from the status quo mobilize to form coalitions to support continuation of a given institution or policy.

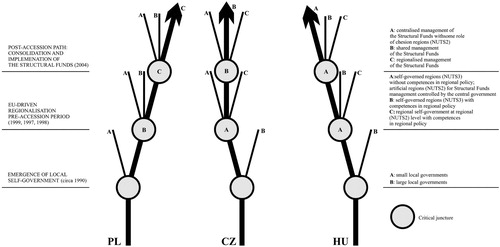

That said, there can be events which may disrupt the balance of power between the actors and change the structures of opportunities for them, resulting in a shift of preferences and new institutions being formed. Such events are referred to as ‘critical junctures’, defined as ‘moments when substantial institutional change takes place thereby creating a “branching point” from which historical development moves onto a new path’.Footnote34 Often these are major exogenous shocks, such as an economic crisis, a military intervention or an important geopolitical event. Basically, critical junctures can be best understood as moments where constellations of interests and opportunities change, resulting in the formation of new or modification of existing institutions, which then open up new institutional pathways. This study uses the concept of ‘critical junctures’ to shed more light on the ways in which the EU has influenced and shaped the emergence of strategic planning capacity at the sub-national levels in CEECs at three critical moments on their journey towards EU membership.

Path dependencies and European influence

This empirical section will explain how the EU influenced strategic planning practices at the regional level in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, by focusing on three ‘critical junctures’: the establishment of local self-government units in the context of systemic transition after the collapse of communism in 1989; regionalization reforms in the context of the opening of the process of EU accession in the mid-1990s and preparation for the management of the EU SF; and finally, accession to the EU itself and implementation of those funds. At these critical moments, windows of opportunity for a change in the territorial organization and strategic planning practices opened, albeit resulting in differentiated trajectories of change. These differences, as will be argued, can be explained by the ‘stickiness’ of the institutional choices made at those junctures, which shaped the domestic responses to the influence of the EU.

Choice of case studies and research methods

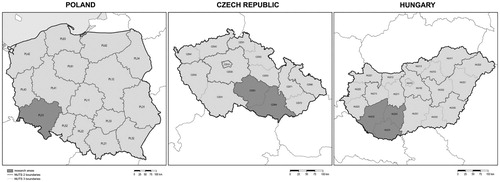

The three countries studied here experienced a regime change from communist dictatorship towards liberal democracy and market economy in 1989 and have followed a similar timetable in the process of accession to the EU. However, their trajectories in territorial reforms undertaken in the wake of EU accession were different, which resulted in differentiated outcomes adjustment to the EU CP framework. In fact, the three countries differ not only in the degree of autonomy, competencies, and size of the regional authorities in relation NUTS 2 level, which is critical for the implementation of EU CP, but also in terms of the approaches to the management of the SF and of the size and thus capacities of the local self-government units, which are the main recipients of these funds (see ).

Table 1. Local level of government in the countries under investigation.

In each country, one region on NUTS 2 level was selected for a more in-depth focus and fieldwork: Lower Silesia (Poland); the South East Cohesion Region (Czech Republic); and South Transdanubia (Hungary). NUTS 2 is a meso-level unit of territorial classification used by the EU for statistical purposes (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) and for the implementation of SF, which are distributed by the so-called Managing Authorities at this territorial level. While the comparison remains imperfect, with the Polish and Czech Regions being among the more developed regions in their countries and South Transdanubia being Hungary’s least developed one, what the three regions share is a relatively more developed cooperative culture and/or a track record of institutional innovation in the process of regionalization.

Concerning the research methods used, this paper mainly analyses secondary sources, such as laws, reports, and planning documents, as well as press articles. These were complemented by insights from 46 semi-structured interviews conducted in the 3 regions under investigation as well as in the capitals of the countries in which they are located. The interviews focused mainly on the impacts of EU rules on strategic planning at regional and local levels after accession to the EU. They allowed for triangulating the findings from the analysis of secondary sources and enhancing validity of findings. They also allowed for investigating the actors’ perceptions of the strategic planning practices and the EU’s influence on them. Interviewees were selected from the key informants within the institutions involved in management of the SF at the central level (e.g. the Ministries of Regional Development, Hungarian National Development Agency), regional authorities, regional development agencies, municipalities and a variety of regional development experts.

The first critical juncture

The first period of interest from the point of view of this paper, from 1989 to roughly mid-1990s, started with the implosion of the communist regimes, followed by a period of transition towards liberal democracies. In most of the countries of the former Eastern bloc, the re-establishment of local self-government was widely considered as part of the process of democratization. In fact, under communist rule administrative systems were extremely centralized (reflecting the idea of the so-called ‘democratic centralism’) and territorial self-governments were non-existent. Instead, there were purely administrative territorial units without much autonomy, serving as a ‘conveyor belt’ for the directives and policies coming from the top and often operating under direct trusteeship of the regional communist party branches. Thus, municipal self-government with elected authorities was introduced in 1990 in the three countries, revolutionizing the territorial administration systems. In all of those cases, however, planning practice remained somewhat weak and contested due to its associations with centralized planning prior to 1989 and the huge momentum that the neoliberal paradigm had as an antidote to the failures of the centrally planned economy, which was reflected in planning, particularly at the local level, where the interests of the private investors heavily weighted on the land use decisions.Footnote35

At this stage European influence was irrelevant, first, because the CP was barely established in 1988, and second, because accession to the European Community was little more than a distant dream for the post-communist leaders with their eyes fixed on the systemic transition, albeit framed in the rhetoric on ‘return to Europe’. In other words, in the early 1990s, there was no realistic prospect for the post-communist countries to join the European Community. However, with hindsight, the choices made then concerning the division of the territory into local government units were critical from the point of view of capacity to adjust to and adopt the EU CP’s framework, including the rule on multi-annual strategic programming of the use of the SF, after these countries’ accession in 2004.

In Poland, communes (gminy) retained their pre-1989 borders and were categorized into three types: rural, urban–rural, and urban. In the Czech case, the post-1989 transformation entailed increasing the number of municipalities (obcí) from 4108 to 6250 and classifying them into seven categories with different scope of responsibilities, depending on the size of a unit.Footnote36 In Hungary, the pre-existing local units (települések) were also used as a basis for the introduction of decentralized, local self-government and divided into categories based both on size and developmental character: rural or urban.

In all three countries, the reformed municipalities have become equipped with a set of new competences, rights, and roles. Decentralization was the shared priority of local government reform. Municipal self-government was meant to introduce an adequate form of fiscal management, along with competences and rights mainly concerning issues like development, land use planning, infrastructure, citizens’ empowerment and needs.

Czechoslovakia (from 1993 the Czech Republic) and Hungary opted for relatively small municipalities (see ), which entailed limited resources for the local governments to steer local development and engage in complex strategic planning tasks. The Czech (12.6 km2 and 1641 inhabitants on average) and Hungarian (29.51 km2 and 3229 inhabitants on average) municipalities thus had to form so-called micro-regions in order to pool resources and plan investment in infrastructure. In Poland, by contrast, the newly established local authorities governed over a much more substantial territory (130 km2 on average) and population (16,000 on average), giving them more capacity and resources to plan and implement investment in infrastructure to promote local development. However, it should be stressed that in Poland too, municipalities tended to lack adequate experience. Planning practice as such remained contested as a remnant of the previous regime and competed with a preference for letting the market forces steer development.Footnote37

Thus, the collapse of the communist regimes and the start of transition towards liberal democracies was the first critical juncture at which the choices of options for local government reform were taken. The three countries embarked on reforms to establish local self-government roughly at the same time, but chose different paths for this process. These choices made in 1990 later constrained the capacity of the municipalities to seize the opportunities stemming from EU CP and engage in learning processes leading to the development of strategic planning at the local level.

The second critical juncture

The second critical juncture, when the later developments in the development of strategic planning capacity in the three countries studied here were determined, was the opening of the negotiations on the accession of these countries to the EU and the following process of adjustment to EU norms to meet the membership criteria. That was the period of a powerful external pressure for institutional change and intensive rule transfer from the EU to these countries aspiring for EU membership, which was driven by accession conditionalities.Footnote38 This provided a strong incentive to engage in reforms to adapt to the entirety of EU regulations and policies, including the framework of EU CP, which required the establishment of regional authorities capable of managing the SF in an effective way and according to regionally designed strategies and operational programmes.

Pressure from the EU and the offer of the ultimate reward for compliance in the form of EU membership put the three countries on a new path towards regionalization. It changed the structure of opportunities for actors, providing incentives for the introduction of regional governments and a new cognitive template for this in the form of the principles of EU CP. The latter make sub-national governments important actors in its implementation (partnership principle) and require that the EU funding is used strategically across the different parts of national territories (programming principle).

The European Commission exerted influence on these processes through twinning programmesFootnote39 as well as through the Commission’s regular reports on progress towards accession that were issued from 1998 to 2004, which included a section on regional policy. These reports scrutinized the development of administrative capacity, regionalization reforms and the formation of an institutional structure to manage EU CP after accession (emergence of regional development ministries, establishment of regional authorities), examined the founding of a legal framework for regional policy, and pointed to what should still be done and improved. From 2001 onwards ‘accession partnerships’ were introduced as a tool for driving further adjustment to the EU rules, including those on regional policy, and specifying the timetable for changes and needs in terms of building administrative and judicial capacities. In parallel, there was also the actual negotiation of the acquis under so-called ‘chapter 21 Regional policy and co-ordination’, that took place between the European Commission and the national governments of the three countries studied here between January 2000 to December 2002.

The chosen approaches of the three countries to this reform differed. They were presented with two dilemmas. One entailed a choice between (a) setting up regions with elected self-government, and thus a relatively strong regional authority, having responsibility for steering economic development within its territory and dealing with regional planning, and (b) establishing regions without elected authorities and only delegated powers from the central government, thus authorities that are weaker and not based on self-government – in other words, between decentralized regional authority and deconcentrated regional authority. The other dilemma was between (c) setting up relatively large regions that would match NUTS 2 units at which EU CP’s ROPs are implemented, and (d) opting for smaller regions and bundling them together at NUTS 2 level solely for the purpose of implementation of the SF, but without locating regional authority at this level. In the former case, the regions would gain a powerful source of funding and thus also the power that comes with the responsibility for the determination of the priorities for the use of the SF and of the distribution of funding among the local authorities and other beneficiaries.

The Polish reform in 1999Footnote40 established elected regional authorities (województwa) and sub-regional ones (powiaty). While the competencies of the latter are rather limited when it comes to steering economic development, the former were given substantial competencies in regional development policy and planning, coupled with financial transfers to support investment in specific areas as part of the so-called regional contracts between the regions and the central government,Footnote41 albeit with limited fiscal autonomy. Later in 2003, the Law on Spatial Planning and Development (UPZP),Footnote42 specified the responsibilities of the regional authorities in województwa in terms of preparing regional development strategies. Since 2006 these strategies are supposed to provide a strategic basis for the ROPs,Footnote43 documents specifying the priorities for using the SF the regions. Thus, in the Polish case, there is a close connection between regional spatial planning and the framework for implementing EU CP at the regional level.

Among the three countries studied here, in Poland regions have definitely the widest competences in spatial planning. Importantly, however, the Polish regions are by far the biggest among the CEECs, with an average population of roughly 2.4 million and an average territory of 19,544 km2 (Brusis 2002), and their boundaries were designated to fit the NUTS 2 classification (see , the areas shaded in dark grey correspond to the case study regions). This decision has significant consequences when it comes to implementation of EU CP after Poland’s EU accession in 2004, as the Polish regions became key players in the management of EU SF.

Figure 1. The boundaries of NUTS 2 and NUTS 3 levels in the countries studied. Source: Elaborated by the Authors on the basis of NUTS classification maps from EUROSTAT

The Czech Republic, in contrast to Poland, has less endogenous pressures for establishment of the regional tier of government after the collapse of the communist system. As the prospect of EU accession became clearer in the late 1990s, however, the Czech Republic also embarked on the regionalization path to respond to EU pressures to put in place an institutional system for EU CP. Thus, in 1997 14 self-government regions (kraje) were established – albeit due to procedural delays they only begun operating in 2001.Footnote44 In 2006, the Czech regions were given considerable powers in regional development policy, incorporating the principles of EU CP, such as multi-annual programming, and were entrusted with the task of preparing statutory regional planning documentsFootnote45 and, similar to the Polish regions, development strategies additionally set priorities for the use of the SF.Footnote46 These strategies aligned with the National Development Strategy and provide inputs for the ROPs.Footnote47 However, the Czech regions remain relatively small, with an average 737,000 inhabitants, 5633 km2,Footnote48 and, with some exceptions, their boundaries correspond to NUTS 3 level, with the exception of the regions of Prague, Central Bohemia, and Moravia-Silesia (the territories of which match the NUTS 2 classification). Hence, unlike their Polish counterparts, most kraje governments could not act as prospective Managing Authorities for the SF after accession. As a consequence, eight NUTS 2 Cohesion Regions were established in 1998 to put in place institutions compatible with the EU CP implementation system. In most cases, a Cohesion Region is composed of several kraje and are governed by Regional Councils comprising representatives of these regions. In this context, the priorities of the ROPs have to combine the priorities outlined by each of the relevant kraje, which may subject to negotiation and power play between them. After accession in 2004, this arrangement made it impossible for the Czech kraje to use the powers in the distribution of the SF to reassert their power and standing as the Polish regions did, and resulted in the establishment of an institutional system for distribution of the EU funding that was parallel to the territorial administration system. Thus, the Cohesion Regions lacked legitimacy and power stemming from elections that the Kraje had.

Finally, in the case of Hungary, while the 19 counties (megye) were established as part of the 1990 Law of Local Government, they remained relatively weak actors in the state administration system, even after acquiring ‘territorial government’ status in 1994. This situation can largely be attributed to a lack of traditions of local or meso-level self-government in Hungary and a strong legacy of centralization that even predates the communist period.Footnote49 Not only are megye relatively small, with an average of 537,000 inhabitants and 4895 km2,Footnote50 but also their role is mainly administrative and do not play a significant role in spatial or economic development policy. Planning is, in fact, the domain of the central government and the municipalities, with an effective planning vacuum at the meso-level.Footnote51

From the mid-1990s, as elsewhere in Central Europe, the perspective of EU accession has galvanized territorial reforms in Hungary but preference was given to maintaining the counties and creating a parallel system for administering EU funds after accession, as in the Czech Republic. Thus, the 1996 Spatial Development and Land Use Planning Act, a document influenced by the EU experts, introduced a system of development bodies at four levels, from local to national, allowing the municipalities and counties to cooperate voluntarily on micro-regional and regional scales, respectively.Footnote52 In 1999 seven Cohesion Regions at NUTS 2 level were established, each comprising several counties operating at NUTS 3 level. The purpose of the Cohesion Regions was mainly to coordinate preparation of ROPs for the purpose of the EU SF. In South Transdanubia the ROP was to reflect the strategic priorities of the three counties, however, the latter had neither competence nor capacity for strategic planning. To some extent, this gap was bridged by the obligation to prepare strategic documents as a pre-condition for application for ROP funding. However, these documents, often prepared in collaboration between several municipalities, reflected not regional priorities but rather those specified by the central government. Regional Development Councils (RDCs), in turn, comprised representatives of the counties, municipalities, NGOs, but also of the central government, with the latter being a majority group of representatives. It can be argued that, even more so than in the Czech case, the Cohesion Regions have remained institutionally and politically weak, somewhat reflecting the weak role of the counties in regional development policy and the preferences of the Hungarian elites for regionalization ‘light’, but also being due to an (increasingly) firm grip of the central government over the activities of the RDCs and to weakening pressure for regionalization from the European Commission itself in the late 1990s.Footnote53

In sum, regionalization reforms were carried out in all three countries between 1996 and 1999, but they followed different options for reform. Contingent institutional choices made in response to this critical juncture produced very different regional authorities, with different capacities, that had important consequences during the next stage of institution-building.

The third critical juncture

The third critical juncture was the actual accession of Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary to the EU in 2004. It was a game-changing event which again, like the previous shift from communism to liberal democracies with market economies and like the opening of the negotiations on the accession, has changed the structure of opportunities for the regional and local actors involved in regional policy. Thus, while in the pre-accession period the adjustment to the EU CP framework was largely driven by the accession conditionality, once this ultimate reward was reaped the EU’s capacity to influence institutional and policy changes and to exert compliance with its norms was largely weakened.Footnote54 Thus, one could expect that after accession the new EU Member States could lose their reform zeal and be tempted to reverse some of the hanges introduced prior to 2004 which were intended to satisfy the European Commission’s demands, but were not necessarily in line with the preferences of the central government. This, for instance, was the case with regionalization reforms in Hungary, where the Fidesz governments (1992–2002 and 2010 to present) in particular were suspicious of delegating powers to the sub-national actors.

That being said, after accession the actual implementation of EU CP started and it was only then that the regional authorities could get real experience of managing the SF and using them to support their strategic priorities. Only too when the SF actually started flowing after EU accession did local authorities – the main recipients of EU Cohesion Policy funding – have proper exposure to the rules governing the implementation these funds.

Regional level: U-turns and (missed) learning opportunities

Thus at the regional level, to begin with, the European Commission itself has contributed to the weakening of the newly established regional authorities. As the accession date approached, the European Commission made a U-turn when it came to promoting regionalization in the candidate countries and instead started arguing for centralized management of EU funding in the first 2004–2006 programming period as a transition phase, fearing that the new regions would lack capacity to implement the SF via their own ROPs. Consequently, for all the three countries studied, the Commission recommended entrusting the management of the ROPs to central governments as part of single Integrated Regional Operational Programmes (IROPs) for each country.Footnote55 Here, the regions were effectively side-lined from the programming of the Structural Funds and thus were not able to use the preparation and management of ROPs to develop strategic planning and administrative capacity. In fact, the priorities of the IROPs were not set regionally but rather defined centrally, regardless of the actual regional specificities, challenges to regional development and place-specific investment needs. The priorities for allocation of the SF in regions were specified at central level.

However, this arrangement was meant to be a temporary fix to the administrative capacity deficit and in the subsequent EU CP programming period, 2007–2013, the regional authorities from the new Member States were expected to prepare and manage their own ROPs corresponding to NUTS 2 regions. In the case of Lower Silesia, as for all Polish regions, the preparation and implementation of the ROP were delegated to the regional authority, since the boundaries of the region corresponded to the NUTS 2 region boundaries (see ). In the case of the Czech Republic’s South East Cohesion Region, comprising the South Moravia and Vysočina regions, the authorities of those two regions were jointly responsible for the formulation of the ROP for the Cohesion Region. The implementation of the programme was delegated to the Regional Council, comprising representatives of the two Kraje. In the Hungarian case and the South Transdanubia cohesion region, preparation of the ROP was the responsibility of the Regional Development Agency in Pécs, which also was given responsibility for implementation of this programme on behalf of the National Development Agency, based in Budapest. Some commentators argued that ‘represented a major turning point in building regional capacities’Footnote56 and created scope for developing a more place-based strategic thinking regional level.

The actual scope for seizing these opportunities was very different in each of the three countries. In the Polish case, because of the match between the ROPs’ boundaries and those of the self-governed region, the regional development strategy could be used as a basis for setting the priorities for use of SF to be outlined in the ROP. The regional authority enjoyed a high degree of autonomy in this process. Thus, the regionalization of the management of the EU funds created an opportunity for the regional authority to develop strategic planning capacity and provided a major source of funding for realization of the regions’ strategic goals that was independent from central government transfers. This was made possible by the regionalization choices taken in the run-up to Poland’s accession, allowing both for an institutional alignment of the regional entities for CP management with the self-governed regions at NUTS 2 level and for a close connection between regional-level territorial planning and planning for the purpose of the EU funds and ROPs.Footnote57

By contrast, in the Czech case, the ROP for the South East Cohesion Region not only had to result from a compromise between the strategic priorities of the two participating Kraje, but also the options for setting these priorities were severely constrained with the central government imposing three priority axes for all the Czech ROPs (transport, sustainable tourism, sustainable development of towns and villages). Thus, one can argue that the regionalization path on which the Czech Republic embarked as part of its pre-accession Europeanisation limited the room for regional empowerment and strategic capacity development, as was observed in Poland. It also resulted in hybrid situation with shared responsibilities for the management of the SF post-2007 between the two Kraje bundled in an ‘artificial’ Cohesion Region. In addition to this legacy of the Czech regionalization pathway, the scope for influence of CP on the actual strategic planning practice was constrained also through the separation of planning for the purpose of CP, in which Kraje were involved, and the actual territorial planning for which the key actors are central government and local authorities, with a lesser role for the regional tier.Footnote58

Finally, in the Hungarian case, due to the weak role of the counties in the territorial administration system and the fact that they do not have responsibilities for regional development, the role of this tier in the preparation of the ROP was marginal. What is even more striking, however, is the strong degree of central control on the regional programming process. Central government set a menu of priorities and interventions for the ROPs from which the Regional Councils in cohesion regions could pick and choose elements that suited them.Footnote59 The RDAs then formulated draft ROPs on that basis and organized consultations to gather input from the regional stakeholders. However, these choices ‘were often overwritten and overridden’ by the National Development Agency supervising the implementation of EU CP from the central level.

Even though ‘centralisation of the administration of regional policy is a perennial phenomenon in Hungarian politics regardless of the ideological colour of the government in power’,Footnote60 this centralizing trend has been further reinforced since the conservative party Fidesz, led by Viktor Orbán, returned to power in Hungary in 2010. Thus, in 2011 the Local Government was amended to transfer some of the competencies to the central level and the newly established county-level deconcentrated central government offices, while the Spatial Development and Land Use Planning Act amendment from the same year abolished development councils at the national, regional, county and micro-region levels as a means to improve the efficiency of public administration, put the Regional Development Agencies under closer supervision from the National Ministry of Development, and left the consultation bodies for county presidents as the only institutions operating at NUTS 2 level.Footnote61 In sum, the Fidesz government unravelled the EU-driven regionalization, hollowed out the sub-national governments and centralized regional and spatial policies in Budapest.

To understand the EU influence on strategic planning at the regional level, it is also revealing to take a closer look at how the ROPs were actually elaborated in terms of engagement of the regional stakeholders, in line with the requirements of the EU CP’s partnership principle. The latter calls for close cooperation between the actors at various scales and representing various stakeholder groups in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of the implementation of the SFFootnote62 requires inclusion of sub-national authorities as well as economic and social partners at all stages of implementation of the SF. Widespread consultations of the ROPs were initiated in the run up to the 2007–2013 programming period, thus creating scope for the participation of stakeholders in the programming process.

Nevertheless, in practice there were considerable differences in the outcomes of stakeholder engagement in the formulation of the ROPs. Only in the Polish case of Lower Silesia did the municipalities have any influence on the ROP priorities via sub-regional consultation groups established for that purpose. Most of the stakeholders interviewed in Lower Silesia claimed to have had a genuine possibility to influence the ROP and that their voice was considered. Urban redevelopment was an example of a priority introduced as a result of pressures from the municipalities. Conversely, in the Czech and Hungarian regions, no evidence of such mobilization of municipalities or of the influence of the regional stakeholders on the ROPs was mentioned by interviewees. Therefore, this indicates that stakeholder engagement in South East and South Transdanubia regions was largely a ‘window-dressing’ exercise that defied the very purpose of participative regional strategic programming.

In all three cases, however, the engagement of stakeholders in this process faced common hurdles. For instance, smaller or peripheral municipalities tended to be less or not at all active. Another major problem that remains is that strategic planning stimulated by EU CP eventually fails to target actual place-specific developmental challenges and opportunities. In Poland, with strong pressure to disburse the SF and an equally strong demand for grants among the local authorities, the regions largely failed to articulate their strategic aims and opted for a broad-brush approach to maximize the intake of EU funding. While in the Czech Republic and Hungary, the strong control of the central government on the elaboration of the ROPs undermined the ability of these programmes to address regional needs.

Local level: uneven exposure to EU influence

Shifting the focus to the local level, after 2004 the municipalities came into play as the main beneficiaries of the SF,Footnote63 including those distributed via ROPs. It can be argued thus that it was only after EU accession that the municipalities became actually exposed to the influence of EU CP. In order to be eligible to apply for European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) subsidies for their projects, the municipalities needed to demonstrate that the projects that they wished to have supported with European monies were part of the efforts to implement a local development plan. This requirement spurred municipalities wishing to benefit from EU funding to prepare such documents, which encouraged municipalities to reflect on their development priorities and resulted in an explosion of local plans. It is here that the legacies of the choices made at the first critical juncture, regarding the (re)establishment of local self-government, become apparent. Many of the Czech and Hungarian municipalities were unable to acquire EU funds due to lack of financial capacity to provide match funding and human resources and skills to engage in the planning activities that were pre-requisite for applying for ERDF subsidies. In Poland, the situation was different as most municipalities were able to fulfil the eligibility criteria and acquire EU funding, albeit the capacity to do this also varied markedly, with some remaining excluded from EU funding programmes.

The interviews in all three regions studied revealed that strategic planning at the local level is seldom considered to be more than a formality required to get access to EU money, particularly in municipalities with lower capacity to develop a coherent development strategy. The problem of limited planning capacity is more acute in Hungary and Czech Republic where municipalities are small; while in Poland it concerns particularly the smaller or peripheral units. In addition, local strategic planning documents tend to be tailored to the priorities of the ROP rather than to actual local needs. In many cases, strategies were akin to ‘wish lists’ or were prepared by consultancy firms according to a template. As a result, many beneficiaries from European funding were fragmented small-scale investment projects aimed at improving the quality of life of the citizens (and boosting the popularity of the local government) rather than at achieving well-thought strategic developmental objectives.

Despite negative aspects, however, there were encouraging signs of change across the three regions. For example, it was found that bigger (or more resourceful) municipalities tended to learn, accumulate experience and gradually internalize strategic planning, even though it was initially considered to be solely a requirement to gain access to funding. This obligation did stimulate reflection on the development and introduced the local officials to the use of new instruments, such as indicators of output, SWOT (Strenghts, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis and consultations. Positive spin-offs, such as increased transparency in the spending of public funds, as well as spillover and learning effects, could be observed.

In sum, after EU accession the scope to use the EU funds to build strategic planning capacity among the regional and local authorities in Poland’s Lower Silesia, Czech Republic’s South East region and the Hungarian South Transdanubia remained differentiated. Looking back at the previous critical junctures in the reforms of territorial administration in the context of the systemic transition and preparations for EU membership, namely the establishment of local self-government in 1990 and later regionalization reforms between 1996 and 1999, allows for explaining these differences.

Conclusions

This study builds on and adds to the previous research on Europeanisation of sub-national authorities by shedding light on how the EU and its CP have influenced the development of strategic planning capacity at the local and regional levels in the CEECs. Unlike previous studies, it used historical institutionalism to explore the formation of path dependencies in the process of reform of territorial administration and planning systems from the fall of communism in 1989 to the first years after accession to the EU in 2004. The use of critical junctures as analytical lens provided a framework for comparison and enhanced our understanding of why Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary responded in different ways to the pressures from and opportunities created by EU accession and the inflow of EU SF. It also highlighted the limitations of Europeanisation of regional and local planning practices by stressing the stickiness of institutional paths chosen early on in the transition and EU accession processes and the ways in which these choices can constrain the scope for learning and internalization of EU-imported practices.

This study demonstrated that the choices made at the critical junctures identified – that of establishment of local self-government in 1990 and subsequent reforms introducing regional governments in the latter half of the 1990s – were critical for the later development of strategic planning capacity at the regional and local levels in the context of pre-accession adjustment to the European norms and post-accession implementation of EU CP. Focusing on those junctures helped to explain how major exogenous events (e.g. end of communism, EU accession), may (1) bring opportunities for changing the institutional development pathways using external stimuli and resources which are seized (as was the case to some extent at least in Poland) or not (as was the case in the Czech Republic and Hungary), but also (2) how the choices made of those junctures can result in choosing sub-optimal solutions that remain ‘sticky’. In the case of the Czech Republic and Hungary the options chosen at these critical junctures limited the scope for learning and adopting strategic planning. By contrast, in Poland, they allowed for the emergence of regional and local authorities that were more capable of managing and/or benefiting from EU funds and thus being exposed to norms governing their implementation, which require inter alia that the funding be given to support strategic regional and local development priorities defined in a participatory process. illustrates these findings.

Figure 2. The critical junctures and pathways of territorial administration reforms and implementation of the SF in Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary. Source: Authors.

That said, despite the notable differences that were outlined above, in all three cases the legacies of the communist era and the transition period, including low administrative capacity, clientelism and passiveness of local leaders resulted in superficial and formalistic compliance with EU requirements regarding strategic and place-based use of the SF. In fact, the EU and CP remain largely perceived by the governments at all scales in those countries as a ‘milking cow’ and thus regional and local strategic planning tends to remain a hollow ‘window-dressing’ exercise.

In closing, one is tempted to speculate what comes next? There are signs that the paths on which the three countries discussed here embarked upon remain sticky and the trends described above are set to continue. One indication of that are the choices for the implementation of the SF in the 2014–2020 period. While the Polish government chose to maintain and even reinforce the regionalization of management of the funds in that period, with a doubling of funding allocated to the 16 ROPs,Footnote64 the Czech government reverted to a system with a single IROP for all regionsFootnote65 and the Hungarian government continued the centralization trend focusing on sectoral programmes and only including a single territorial programme for all the lagging regions and a separate one for the more developed Central Hungary region.Footnote66 Exploring how exactly these choices will affect the processes of building strategic planning capacity at the regional and local levels and how, in turn, this will affect the ability of EU CP to reduce economic development disparities effectively, remains an exciting avenue for further research. Such research would be all the more salient considering that, in the context of continuing crises and growing euro-scepticism across the EU Member States, CP is under threat or at least growing pressures to deliver tangible results in ensure territorial, social, and economic cohesion across the EU, while helping to achieve the EU’s strategic goals. Thus, the coming years are likely to bring a major overhaul of the policy and that will be the next critical juncture to explore.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to André Sorensen for his inspiration and very helpful feedback. Also many thanks to Michael Hebbert and John Gold for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Marcin Dąbrowski is an Assistant Professor at the Chair of Spatial Planning and Strategy in the Department of Urbanism, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology. In the past, he worked at the University of Vienna and at the European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde, conducting research on (EU) regional and urban policies in European countries, with a focus on governance issues. He published widely on EU Cohesion Policy, including its impacts on spatial planning practices in Central and Eastern Europe. His research interests, however, span across many topics related to urban and regional governance, from regional strategies for circular economy or energy transition, to climate change adaptation in cities.

Katarzyna Piskorek is a PhD Candidate at Wroclaw University of Technology and a Visiting Researcher at Delft University of Technology. In her core research work, she uses linguistic and communication theory as an explanation for social mechanisms and public participation phenomena in spatial planning. Her work focuses on communication issues between local authorities and citizens, not only in theory but also in practice, as well as on spatial planning systems in Europe.

ORCID

Marcin Dąbrowski http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6775-0664

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Committee on Spatial Development. ESDP.

2 Faludi and Waterhout, The Making of the European Spatial Development Perspective.

3 Faludi, “From European Spatial Development to Territorial Cohesion Policy”; and Polverari and Bachtler, “The Contribution of European Structural Funds to Territorial Cohesion.”

4 Dühr, Colomb, and Nadin, European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation.

5 Faludi, “Centenary Paper: European Spatial Planning,” 1.

6 Bache, Europeanization and Multi-Level Governance.

7 Bachtler, Mendez, and Oraže, “From Conditionality to Europeanization in Central and Eastern Europe”; andDąbrowski, “Shallow or Deep Europeanisation?”

8 Manzella and Mendez, “The Turning Points of EU Cohesion Policy.”

9 OECD, How Regions Grow.

10 Bachtler, Mendez, and Oraže, “From Conditionality to Europeanization in Central and Eastern Europe”; and Dąbrowski, “EU Cohesion Policy, Horizontal Partnership and the Patterns.”

11 Stead and Cotella, “Differential Europe”; Stead and Nadin, “Shifts in Territorial Governance”; Cotella, “Spatial Planning in Poland”; Scherpereel, “EU Cohesion Policy and the Europeanization of Central and East European Regions”; Ferry and McMaster, “Implementing Structural Funds in Polish and Czech Regions”; Brusis, “Between EU Requirements, Competitive Politics, and National Traditions”; Hughes, Sasse, and Gordon, “Conditionality and Compliance in the EU’s Eastward Enlargement”; and Ferry and McMaster, “Cohesion Policy and the Evolution of Regional Policy.”

12 Hall and Taylor, “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms”; Pierson and Skocpol, “Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science”; Sorensen, “Taking Path Dependence Seriously”; and Mahoney and Thelen, Explaining Institutional Change.

13 Sorensen, “Taking Path Dependence Seriously.”

14 Ferry and McMaster, “Implementing Structural Funds in Polish and Czech Regions”; Bachtler and McMaster, “EU Cohesion Policy and the Role of the Regions”; Dąbrowski, “EU Cohesion Policy, Horizontal Partnership and the Patterns”; and Adams, Cotella, and Nunes, Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning.

15 Böhme and Waterhout, “The Europeanization of Planning,” 227.

16 Dühr, Colomb, and Nadin, European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation, 301.

17 See: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/pdf/sum_en.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2014.

18 Dühr, Colomb, and Nadin, European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation.

19 Nedović-Budić, “Adjustment of planning practice.”

20 Stead and Nadin, “Shifts in Territorial Governance.”

21 Maier, “11 The Pursuit of Balanced Territorial Development”; and Finka, “5 Evolving Frameworks for Regional Development.”

22 Faludi, “Centenary Paper: European Spatial Planning”; and Stead and Nadin, “Shifts in Territorial Governance.”

23 Dühr, Colomb, and Nadin, European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation.

24 Adams, Cotella, and Nunes, Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning.

25 Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel, “Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe,” 10.

26 Malý and Ondřej, “European Territorial Cohesion Policies.”

27 Ferry and McMaster, “Implementing Structural Funds in Polish and Czech Regions.”

28 Cotella, “Spatial Planning in Poland.” Maier, “Changing Planning in the Czech Republic.”

29 Pallagst and Mercier, “Urban and Regional Planning in Central and Eastern European Countries.”

30 Hall and Taylor, “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.”

31 Sorensen, “Taking Path Dependence Seriously.”

32 Mahoney, “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology,” 507.

33 Sorensen, “Taking Path Dependence Seriously,” 21.

34 Hall and Taylor, “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms,” 942.

35 Cotella and Rivolin, A Conceptual Device for Spreading (Good); Maier, “Changing Planning in the Czech Republic.”

36 Hladík and Kopecký. “Public Administration Reform in the Czech Republic.”

37 Cotella, “Spatial Planning in Poland.”

38 Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, “Governance by Conditionality.”

39 Bafoil et al., “Jumelages Institutionnels.”

40 Law on introduction of the three-tier basic territorial division of the state (Dz.U. 1998.96.603); Law on regional self-government (Dz.U. 1998.91.576 ze zm).

41 Regulski, Local Government Reform in Poland.

42 Law from 27 March 2003 on spatial planning and arrangement (Dz.U. 2003 nr 80 poz. 717).

43 Law from 6 December 2006 on the principles of implementation of development policy (Dz.U. 2006 nr 227 poz. 1658).

44 Ferry and Mcmaster, “Implementing Structural Funds in Polish and Czech Regions.”

45 Building Act, 183/2006.

46 WBU, Studium Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Pogranicza Polsko–Czeskiego.

47 Regional Support Act from June 2000.

48 Brusis, “Between EU Requirements, Competitive Politics, and National Traditions.”

49 Buzogány and Korkut, “Administrative Reform and Regional Development Discourses in Hungary”; and Varró and Faragó, “The Politics of Spatial Policy and Governance in Post-1990 Hungary.”

50 Brusis, “Between EU Requirements, Competitive Politics, and National Traditions.”

51 Varró and Faragó, “The Politics of Spatial Policy and Governance in Post-1990 Hungary.”

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Sedelmeier, “Is Europeanisation through Conditionality Sustainable?”

55 Hughes, Sasse, and Gordon, “Conditionality and Compliance in the EU’s Eastward Enlargement.”

56 OECD, Territorial Reviews: Poland 2008, 211.

57 Cotella, “Spatial Planning in Poland.”

58 Maier, “Changing Planning in the Czech Republic.”

59 Polverari et al., “Strategic Planning for Structural Funds in 2007–2013.”

60 Buzogány and Korkut, “Administrative Reform and Regional Development Discourses in Hungary,” 1573.

61 Varró and Faragó, “The Politics of Spatial Policy and Governance in Post-1990 Hungary.”

62 Dąbrowski, “EU Cohesion Policy, Horizontal Partnership and the Patterns.”

63 If one considers the pre-accession funding as part of PHARE as a ‘warm up’ in which only a few municipalities took part.

64 See summary Partnership Agreement EU–Poland for 2014–2020: http://ec.europa.eu/contracts_grants/pa/partnership-agreement-poland-summary_en.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2016.

65 See summary of the Partnership Agreement EU–Czech Republic for 2014–2020: http://ec.europa.eu/contracts_grants/pa/partnership-agreement-czech-summary_en.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2016.

66 See Summary of the Partnership Agreement EU–Hungary for 2014–2020: http://ec.europa.eu/contracts_grants/pa/partnership-agreement-hungary-summary_en.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2016.

Bibliography

- Adams, Neil, Giancarlo Cotella, and Richard Nunes. Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: Building on EU Enlargement. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Bache, Ian. Europeanization and Multi-Level Governance: Cohesion Policy in the European Union and Britain. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008.

- Bachtler, John, and Irene McMaster. “EU Cohesion Policy and the Role of the Regions: Investigating the Influence of Structural Funds in the New Member States.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 26, no. 2 (2008): 398–427. doi: 10.1068/c0662

- Bachtler, John, Carlos Mendez, and Hildegard Oraže. “From Conditionality to Europeanization in Central and Eastern Europe: Administrative Performance and Capacity in Cohesion Policy.” European Planning Studies 22 (2014): 735–757. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.772744

- Bafoil, François, Fabienne Beaumelou, Rachel Guyet, Gilles Lepesant, Lhomel Édith, and Catherine Perron. “Jumelages Institutionnels : Les Limites D’un Apprentissage Collectif.” Critique Internationale 4, no. 25 (2004):157–167. doi: 10.3917/crii.025.0157

- Böhme, Kai, and Bas Waterhout. “The Europeanization of Planning.” In European Spatial Research and Planning, edited by Andreas Faludi, 225–248. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2008.

- Brusis, Martin. “Between EU Requirements, Competitive Politics, and National Traditions: Re-Creating Regions in the Accession Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Governance 15, no. 4 (2002): 531–559. doi: 10.1111/1468-0491.00200

- Buzogány, Aron, and Umut Korkut. “Administrative Reform and Regional Development Discourses in Hungary. Europeanisation Going NUTS?” Europe – Asia Studies 65, no. 8 (2013):1555–1577. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2013.833015

- Committee on Spatial Development. ESDP European Spatial Development Perspective Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union. Brussels: European Commission, 1999.

- Cotella, Giancarlo. “Spatial Planning in Poland Between European Influence and Dominant Market Forces.” In Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe. A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes, edited by Mario Reimer, Panagotis Getimis, and Hans Heinrich Blotevogel, 255–277. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Cotella, Giancarlo, and Umberto Janin Rivolin. A Conceptual Device for Spreading (Good) Territorial Governance in Europe. ESPON Scientific Report. Luxembourg: ESPON, 2014.

- Dąbrowski, Marcin. “Europeanizing Sub-National Governance: Partnership in the Implementation of European Union Structural Funds in Poland.” Regional Studies 47, no. 8 (2011): 1–12.

- Dąbrowski, Marcin.“Shallow or Deep Europeanisation? The Uneven Impact of EU Cohesion Policy on the Regional and Local Authorities in Poland.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30, no. 4 (2012): 730–745. doi: 10.1068/c1164r

- Dąbrowski, Marcin.“EU Cohesion Policy, Horizontal Partnership and the Patterns of Sub-National Governance: Insights From Central and Eastern Europe.” European Urban and Regional Studies 21, no. 3 (2014): 364–383. doi: 10.1177/0969776413481983

- Dąbrowski, Marcin, John Bachtler, and François Bafoil. “Challenges of Multi-Level Governance and Partnership: Drawing Lessons From European Union Cohesion Policy.” European Urban and Regional Studies 21, no. 4 (2014): 355–363. doi: 10.1177/0969776414533020

- Dühr, Stefanie, Claire Colomb, and Vincent Nadin. European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Faludi, Andreas. “From European Spatial Development to Territorial Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies 40 , no. 6 (2006): 667–678. doi: 10.1080/00343400600868937

- Faludi, Andreas. “Territorial Cohesion Policy and the European Model of Society.” European Planning Studies 15, no. 4 (2007): 567–583. doi: 10.1080/09654310701232079

- Faludi, Andreas. “Centenary Paper: European Spatial Planning: Past, Present and Future.” Town Planning Review 81, no. 1 (2010): 1–22. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2009.21

- Faludi, Andreas, and Bas Waterhout. The Making of the European Spatial Development Perspective: No Masterplan. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Ferry, Martin, and Irene Mcmaster. “Implementing Structural Funds in Polish and Czech Regions: Convergence, Variation, Empowerment?” Regional & Federal Studies 15, no. 1 (2005): 19–39. doi: 10.1080/13597560500084046

- Ferry, Martin, and Irene McMaster. “Cohesion Policy and the Evolution of Regional Policy in Central and Eastern Europe.” Europe-Asia Studies 65, no. 8 (2013): 1502–1528. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2013.832969

- Finka, Maroš. “5 Evolving Frameworks for Regional Development and Spatial Planning in the New Regions of the EU.” In Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: Building on EU Enlargement, edited by Neil Adams, Giancarlo Cotella, and Richard Nunes, 103–122. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Hall, Peter A., and Rosemary C. R. Taylor. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44, no. 5 (1996): 936–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Hladík, Jan and Václav Kopecký. “Public administration reform in the Czech Republic.” Research Paper, Association for International Affairs, 1–34, March, 2013.

- Hooghe, Lisbet. “Building a Europe with the Regions: The Changing Role of the European Commission.” In Cohesion Policy and European Integration. Building Multi-Level Governance, edited by Lisbet Hooghe, 89–128. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Hughes, James, Gwendolyn Sasse, and Claire Gordon. “Conditionality and Compliance in the EU’s Eastward Enlargement: Regional Policy and the Reform of Sub-National Government.” Journal of Common Market Studies 42, no. 3 (2004): 523–551. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9886.2004.00517.x

- Kovács, Ilona Pálné. “Regionalization in Hungary: Options and Scenarios on the ‘Road to Europe.’” In De-Coding New Regionalism. Shifting Socio-Political Contexts in Central Europe and Latin America, edited by James W. Scott, 199–214. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

- Kovács, Ilona Pálné. “Local Governance in Hungary – The Balance of the Last 20 Years.” Discussion Papers Cenre for Regional Studies of Hungarian Academy of Sciences 83 (2011). Pecs: RKK, 2011.

- Kovács, Ilona Pálné, Christos Paraskevopoulos, and Gyula Horváth. “Institutional ‘Legacies’ and the Shaping of Regional Governance in Hungary.” Regional & Federal Studies 14, no. 3 (2004): 430–460. doi: 10.1080/1359756042000261388

- Mahoney, James. “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29, no. 4 (2000): 507–548. doi: 10.1023/A:1007113830879

- Mahoney, James, and Kathleen Thelen. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Maier, Karel. “11 The Pursuit of Balanced Territorial Development.” In Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: Knowledge and Policy Development in an Enlarged EU, edited by Neil Adams, Giancarlo Cotella, and Richard Nunes, 266–290. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Maier, Karel. “Changing Planning in the Czech Republic.” In Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe. A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes, edited by Mario Reimer, Panagiotis Getimis, and Hans Blotevogel, 215–235. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Malý, Jiří, and Mulíček Ondřej. “European Territorial Cohesion Policies: Parallels to Socialist Central Planning?” Moravian Geographical Reports 24, no. 1 (2016): 14–26. doi: 10.1515/mgr-2016-0002

- Manzella, Gian Paolo, and Carlos Mendez. The Turning Points of EU Cohesion Policy. Brussels: European Commission, 2009.

- Milio, Simona. “Can Administrative Capacity Explain Differences in Regional Performances? Evidence From Structural Funds Implementation in Southern Italy.” Regional Studies 41, no. 4 (2007): 429–442. doi: 10.1080/00343400601120213

- Milio, Simona. “The Conflicting Effects of Multi-Level Governance and the Partnership Principle: Evidence From the Italian Experience.” European Urban & Regional Studies 2, no. 4 (2014): 384–397. doi: 10.1177/0969776413493631

- Nedović-Budić, Zorica. “Adjustment of Planning Practice to the New Eastern and Central European Context.” Journal of the American Planning Association 67, no. 1 (2001): 38–52. doi: 10.1080/01944360108976354

- OECD. Territorial Reviews: Poland 2008. OECD, 2008.

- OECD. How Regions Grow: Trends and Analysis. OECD, 2009.

- Pallagst, Karina M., and Georges Mercier. “Urban and Regional Planning in Central and Eastern European Countries – From EU Requirements to Innovative Practices.” In The Post-Socialist City, edited by Kiril Stanilov, 473–490. Dordrecht: Springer, 2007.

- Pierson, Paul, and Theda Skocpol. “Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science.” In Political Science: The State of the Discipline, edited by Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner, 693–721. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Polverari, Laura, and John Bachtler. “The Contribution of European Structural Funds to Territorial Cohesion.” Town Planning Review 76, no. 1 (2005): 29–42. doi: 10.3828/tpr.76.1.3

- Polverari, Laura, Irene McMaster, Frederika Gross, John Bachtler, Martin Ferry, and Douglas Yuill. Strategic Planning for Structural Funds in 2007–2013. A Review of Strategies and Programmes. 20th IQ-Net Conference 2006-06-27. Glasgow: EPRC, 2006.

- Regulski, Jerzy. Local Government Reform in Poland: An Insider’s Story. Budapest: Local Government and Public Service Reform Initiative, 2003.

- Reimer, Mario, Panagiotis Getimis, and Hans Blotevogel. Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Scherpereel, John A. “EU Cohesion Policy and the Europeanization of Central and East European Regions.” Regional & Federal Studies 20, no. 1 (2010): 45–62. doi: 10.1080/13597560903174899

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Ulrich Sedelmeier. “Governance by Conditionality: EU Rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11, no. 4 (2004): 661–679. doi: 10.1080/1350176042000248089

- Sedelmeier, Ulrich. “Is Europeanisation Through Conditionality Sustainable? Lock-in of Institutional Change After EU Accession.” West European Politics 35, no. 1 (2011): 20–38. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.631311

- Sorensen, André. “Taking Path Dependence Seriously: An Historical Institutionalist Research Agenda in Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 30, no. 1 (2015): 17–38. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2013.874299

- Stead, Dominic, and Giancarlo Cotella. “Differential Europe: Domestic Actors and Their Role in Shaping Spatial Planning Systems.” disP – The Planning Review 47, no. 186 (2011): 13–21. doi: 10.1080/02513625.2011.10557140

- Stead, Dominic, and Vincent Nadin. 2011. “Shifts in Territorial Governance and the Europeanization of Spatial Planning in Central and Eastern Europe.” In Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning. Knowledge and Policy Development in an Enlarged EU, edited by N Adams, G Cotella, and R Nunes, 154–177. London: Routledge.

- Swianiewicz, Paweł. “Size of Local Government, Local Democracy and Efficiency in Delivery of Local Services —International Context and Theoretical Framework.” In Consolidation or Fragmentation? The Size of Local Government in Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Paweł Swianiewicz, 5–29. Budapest: Open Society Institute, 2002.

- Varró, Krisztina, and László Faragó. “The Politics of Spatial Policy and Governance in Post-1990 Hungary: The Interplay Between European and National Discourses of Space.” European Planning Studies 24, no. 1 (2016): 39–60. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2015.1066760

- WBU. Studium Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Pogranicza Polsko–Czeskiego. Warsaw: Ministry of Infrastructure and Construction of Poland/Ministry of Development of the Czech Republic, 2004.