ABSTRACT

The role of educational psychologists (EPs) in supporting the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people is increasingly being recognised in light of pressures on support services, and the identified importance of school-based provision. At the same time, EP practice has benefitted from psychological practice frameworks which support formulation and decision-making although, to date, none of these has focused on therapeutic work. This paper proposes a flexible, practical model, based on the constructionist model of reasoned action (COMOIRA) and informed by cognitive behavioural therapy, human givens therapy and motivational interviewing. It offers practical guidance and structure for EPs engaging in direct therapeutic work with children and young people, complementing guidance from the Division of Educational and Child Psychology (DECP) on the delivery of therapeutic approaches in school and communities. Further research and development of this model is encouraged by the authors.

Introduction: the educational psychologist’s role in therapeutic intervention

In the United Kingdom (UK), there is increasing recognition of the importance of school-based support for student mental health, with figures indicating that in 2017 one in eight children and young people aged 5–19 had a mental health disorder (Sadler et al., Citation2018). The green paper Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision (Department of Health & Department for Education, Citation2017) highlighted that the school environment is well suited to a graduated response, and is non-stigmatising, making any interventions offered potentially more acceptable (section 23). The paper also indicated that aspects of school life can trigger mental health difficulties, a point reinforced by the House of Commons Education and Health and Social Care Committees (Citation2018), which concluded that educational factors, including school exclusion, pressures of examinations and the narrowing of the curriculum were contributory factors.

This article starts from the assumption that student mental health exists on a continuum and can fluctuate in accordance with life and educational stressors (Atkinson et al., Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2020). Also, that mental health can be both negative and positive, and that promoting wellbeing can mitigate developing mental health disorders in students (Department of Health & Department for Education, Citation2017; Public Health England, Citation2015). Within this context, educational psychologists (EPs) have an important role, not only in working with individual students, but in supporting schools systemically through building capacity, promoting awareness and reducing stigma (Atkinson et al., Citation2019; Weare, Citation2015). In many cases, given the limitations on EP time and potential cost implications, it may be both efficient and effective for EPs to support wellbeing through training, supervision or mentoring of education support staff, as with the emotional literacy support assistant (ELSA) initiative (Osborne & Burton, Citation2014).

However, in a large-scale survey involving interviews with 577 staff from 341 schools in England, 60% of whom were senior leaders, Sharpe et al. (Citation2016) found that specialist mental health support was most often provided by EPs. Research from Atkinson et al. (Citation2011) also suggested that EPs were routinely engaged in therapeutic practice, with 92% of a self-selecting sample of 455 UK EPs reporting recent therapeutic work; although it is acknowledged that more recent data would help elucidate the current landscape, particularly post the growth in traded services (Lee & Woods, Citation2017), austerity measures and the COVID-19 national health emergency. After convening a working group in response to calls for greater professional practice guidance, and clarification of necessary skills and competencies required for therapeutic work, the Division of Educational and Child Psychology (DECP) published Delivering Psychological Therapies in Schools and Communities (Dunsmuir & Hardy, Citation2016)

While the Oxford English Dictionary (Citation2020) defines therapy as “the treatment of mental or psychological disorders by psychological means”, referring specifically to EP practice, MacKay and Greig (Citation2007, p. 4) asserted that:

Therapeutic work may involve the direct intervention of a psychologist with an individual child or a group of children. Equally it is applicable to the wider role of supporting others with children on a daily basis.

While this paper focuses more on the EP’s role within work with young people, the most commonly reported mode of practice (Atkinson et al., Citation2011; Thomas et al., Citation2019), this multi-faceted therapeutic contribution to supporting children’s mental health and wellbeing should not be overlooked.

Research suggests that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most effective and widely used psychological intervention in the improvement of anxiety in children and young people (A. James et al., Citation2007). However, evidence is generally derived from clinical settings, where intervention variables may be more closely controlled and presenting concerns categorised clinically. A recent systematic literature review (Simpson & Atkinson, Citation2019) identifying eight studies, where it was often used with groups or combined with other interventions (for example, attribution retraining), indicated limited evidence for its effectiveness when used in schools by educational and school psychologists. Indeed, within the review, there was generally a lack of consensus around the therapeutic approaches used by educational and school psychologists, or structures in place to support these. Boden (Citation2020) ascribed limited progress when using CBT within EP practice with a post-16 student, to motivational, systemic and extra-therapeutic factors, although these have also been issues within clinical contexts (cf Marker & Norton, Citation2018). Cryer and Atkinson (Citation2015) suggested that the EP’s therapeutic role also included a capacity to spot “levers for change” (p. 68) within the school system, rather than delivering therapeutic interventions per se. Therefore, the authors suggest a greater need for therapeutic interventions which are cognisant of the contexts in which EPs work, as well as acknowledging systemic school factors which impact mental health and wellbeing.

While the model proposed here seeks to use therapeutic approaches to consider and address a young person’s needs holistically, it is acknowledged that there are current pressures on EPs’ ability to deliver therapeutic interventions, particularly in some local authorities (Hill & Murray, Citation2019; Thomas et al., Citation2019). While consideration of these issues is beyond the scope of this paper, readers are directed to the Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) chapter on Commissioning and service delivery for further information.

Professional practice frameworks in EP practice

Kelly et al. (Citation2008) described professional practice frameworks, which offer a model for practice without stipulating precise processes, as essential resources for integrating theory and practice. These leave space for different approaches and theoretical orientations to guide work at different levels. The first published professional EP practice framework was conceptualised by Monsen et al. (Citation1998). Originally defined as a basis for explicit teaching of case formulation for EPs in training completing the then one-year Masters training programme, Monsen et al. (Citation1998) hoped that making the model explicit would allow for open and transparent practice. This led to an emergence of different frameworks informed by constructionist (cf. Gameson et al., Citation2003) and socio-cultural (cf. Leadbetter et al., Citation2007) philosophies. Fallon et al. (Citation2010) proposed that psychological frameworks have helped clarify understanding of the role of the EP, highlighting the contribution to psychological, interactionist, constructionist, and ethical understanding of practice. Professional practice models may have also helped EPs to become more recognisable as scientist practitioners (Fallon et al., Citation2010).

Frameworks for therapeutic practice for EPs

DECP guidance (Dunsmuir & Hardy, Citation2016) offered advice for therapeutic delivery by EPs. The document covered a number of different areas: theoretical frameworks and key principles, ethical practice, the evidence base, training and supervision, practicalities, commissioning and evaluation. While the model of “core principles for delivery of psychological therapies” (p. 23) set out key procedures, processes and principles for delivering therapeutic approaches, it offered limited detail about how an EP might actually work with a young person, in terms of the specific therapeutic approaches they might use. This was identified as an area for further research and exploration by the authors of this paper, one of whom was a member of the DECP working group behind the Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) guidance.

The professional practice model proposed in the current paper is designed to help EPs to operationalise these principles, particularly the components relating to engaging, information gathering, formulating and decision-making. While it focuses specifically on direct therapeutic work, it is acknowledged that this might take different forms. It is envisaged that the model could provide a structure for a therapeutic intervention, for example, in response to expressed concerns about anxiety, emotional regulation or emotionally-based school non-attendance. However, it also provides a template for working therapeutically within the context of a wider brief, for example, an assessment or multifaceted piece of casework. Finally the model offers a “toolkit” which EPs can draw on during their casework to supplement their existing repertoire of assessment and intervention skills and strategies.

The model presented should be considered in parallel with the Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) guidance, which offers more detail about the commissioning, contracting, logistics and evaluation of therapeutic approaches than can be offered here, within the scope of this paper.

From this perspective, it is important to note that the authors support the positioning of therapeutic support within an interactionist paradigm (Dunsmuir & Hardy, Citation2016), acknowledging Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979, Citation2005) bioecosystemic model. Cryer and Atkinson (Citation2015) suggested that the EP role within therapeutic practice was more akin to that of a “caseworker” than “therapist” and involved coordinating support with parents, teachers and other agencies, as well as optimising affective and educational factors in the child’s school environment (p. 67). For this reason, the framework proposed here does not only draw on applying therapeutic ideas, such as the concept of ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) or understanding links between thoughts, feelings and behaviour (Stallard, Citation2005); but acknowledges the wider context of school-based intervention, as well as the limits of what is feasible and achievable to EPs.

In developing a therapeutic model, both authors have previously found the Constructionist Model of Reasoned Action (COMOIRA) framework (Gameson et al., Citation2003; Rhydderch & Gameson, Citation2010) effective for working therapeutically with children and young people. COMOIRA has strong theoretical roots and well-defined practice applications. It offers a heuristic for guiding professional work which can be applied to different contexts, offering stages and processes which help to facilitate change (Rhydderch & Gameson, Citation2010). The model, which has been used and researched within practice (Eddleston & Atkinson, Citation2018), has been reviewed and refined over a number of years (Gameson et al., Citation2003; Rhydderch & Gameson, Citation2010) and is based upon four underpinning principles:

Constructionism – that groups and individuals construct their own unique interpretations of events.

Systemic thinking – that questions and change issues are considered within a holistic frame of reference.

Enabling dialogue – promoting self-efficacy and independence as opposed to reliance on an “expert”.

Informed, reasoned action – considered choices are made in relation to desired outcomes.

Its flexibility allows for an iterative approach and allows for change to be considered within the context of wider systems. However, as EP trainers, the current authors have observed that often explicit teaching is required to make links between therapeutic work and COMOIRA; while at the same time, trainees are keen to understand the fundamental principles of therapeutic engagement and to have ideas for working directly with children and young people. As such, this paper’s suggested model is designed to illustrate how an individual therapeutic intervention might be structured.

The proposed model is based upon principles from three main therapeutic approaches: motivational interviewing (MI), human givens (HG) therapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The rationale for this is that these are the main modalities used by the authors; but it is also believed that each approach provides a complementary perspective on therapeutic working. Specifically, the authors consider that strengths of the approaches lie with attention to the therapeutic relationship (MI); the therapeutic structure (HG); and technical and psychoeducational tools and strategies for promoting wellbeing (CBT). Combining approaches in this way is consistent with an integrative approach which promotes selecting different theories and techniques from different models of therapy to develop a new framework for practice. Specifically, this framework employs the integrative approach of “technical eclecticism” (p. 1), which seeks to use effective factors from different approaches (Zarbo et al., Citation2016). The relative contribution of each of these modalities will now be considered in turn.

Motivational interviewing

MI is not described as a therapy, but as a person-centred counselling style which seeks specifically to address the notion of ambivalence about change (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). MI defines both its relational and technical components (Miller & Rose, Citation2009). Relational factors link closely to the central spirit of MI (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) and indicate that the practitioner should demonstrate: acceptance (including accurate empathy, a non-judgemental approach and respect for the client’s autonomy in making behavioural changes): compassion (acting in the client’s best interests; partnership (collaboration) with the client; and evocation (meaning that the practitioner should be mindful that reasons for change have to come from the client). Technical factors relate to the elicitation and amplification of change talk, and the suppression of sustain talk (arguments for staying the same). Practitioners are encouraged to work through processes of engaging, focusing and evoking with the client, before planning for change; and to utilise skills of open questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). MI is often used to enhance the effectiveness of other therapeutic approaches (cf Marker & Norton, Citation2018) because it helps build motivation for change. Additionally, the authors argue that MI offers a particularly strong contribution to the relational aspects of therapeutic practice.

Human givens therapy

HG therapy (Griffin & Tyrrell, Citation2003) is a psychotherapeutic approach with a growing evidence base (cf Attwood & Atkinson, Citation2020; Minami et al., Citation2013; Yates & Atkinson, Citation2011) which posits that individuals have innate emotional needs (Human Givens Institute, Citation2006) which, if not met in balance, can cause emotional distress. It draws on ideas from other counselling paradigms, including MI and CBT, to propose a holistic and practical framework for understanding what is needed to be mentally healthy. While it can be described as a therapeutic approach in itself (Attwood & Atkinson, Citation2020; Yates & Atkinson, Citation2011), identification of unmet emotional needs can potentially provide avenues for more systemic intervention (Waite et al., Citation2021). Within direct work, HG offers a practical and positive approach to supporting clients, using a clear therapeutic structure, defined by the acronym RIGAAR, which stands for: rapport; information gathering; goal setting; accessing resources; agreeing strategies for change; rehearsal. The therapeutic structure is particularly explicit, and gives a much clearer sense of direction and progression than within other therapeutic modalities.

Cognitive behavioural therapy

CBT is a therapeutic approach which aims to bring about positive change and facilitate progress in addressing psychological difficulties. Fonagy et al. (Citation2002) described CBT as an effective early intervention, finding it produces positive outcomes, particularly with children who fall within the mild-moderate range of psychological difficulties. CBT is referred to by Squires (Citation2010) as a talking therapy that is gaining popularity as a therapeutic model. Concerns, however, do emerge about the linguistic and cognitive ability required to engage in CBT, and little research exists with children under eight years and with those with learning disabilities (Monga et al., Citation2009).

CBT includes psychoeducation as a key part of intervention and focuses on cognitive as well as behavioural factors, such as withdrawal and avoidance, which can exacerbate and maintain emotional difficulties. A recent Cochrane report (A. C. James et al., Citation2015) concluded from a review of 41 studies that CBT was more effective than no therapy in children and young people experiencing anxiety. Clear, accessible practice description is available (Fuggle et al., Citation2013): CBT practice is defined by key competencies (Roth & Pilling, Citation2007) which have been developed specifically for practitioners working with children and young people (Fuggle et al., Citation2013). Additionally, CBT offers an excellent description of many technical aspects of therapeutic approaches and is ideal for young people who are receptive to intervention (Atkinson & Earnshaw, Citation2019).

A proposed model for therapeutic work

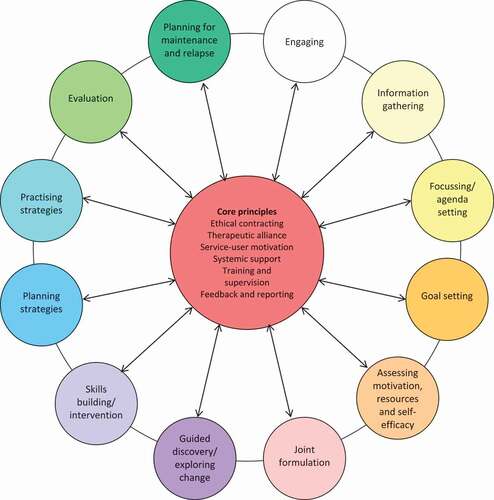

The proposed model follows a similar structure to that of COMOIRA, with key principles at the centre of the wheel, and activities positioned around the outside. Whilst these are broadly sequential, it is not envisaged that the practitioner would necessarily work through all of them, or follow them in order. Instead, in keeping with a flexible and responsive integrative approach (Zarbo et al., Citation2016), they should be considered in relation to the needs of the young person and used according to the ongoing therapeutic needs and formulation.

The proposed model is shown in below. To follow the logical (though not prescriptive) order, outer circles should be read in a clockwise direction, starting from “Engaging” and ending with “Planning for maintenance and relapse”

Core principles

Just as COMOIRA has key principles at its core, which guide professional casework practice, this therapeutic model is also centred on a number of key concepts: ethical contracting, therapeutic alliance, service-user motivation, systemic support, training and supervision, and feedback and reporting. While detailed exploration of these concepts is beyond the scope of this paper, a brief overview, along with references for further reading, can be found in .

Table 1. Overview of key effective concepts.

Process elements of the model

In the following sections, each peripheral process element of the model is discussed in turn. It is hoped that, as well as offering process descriptions, these will provide a toolkit of ideas for EPs wishing to develop and extend their therapeutic practice.

Engaging

While it may be possible to omit some of the later elements of the model, there is consensus between therapeutic modalities that engagement, or rapport building, is key (cf Griffin & Tyrrell, Citation2003; Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013; Roth & Pilling, Citation2007). There is often pressure on EPs to move quickly towards a formulation and plan for desired outcomes, and yet these could be jeopardised by insufficient attention to understanding the young person’s situation via empathic listening, and through identifying strengths, skills and resources (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). Other potential ways of engaging could include meeting or writing to the young person prior to working therapeutically; using preferred activities (for example, art and crafts, sport); or having an initial three-way meeting with a member of staff whom the young person trusts and respects. At this stage there should be acknowledgement that the young person might be ambivalent about addressing behaviours which are concerning to others (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013), particularly if they have been referred by a third person.

Information gathering

Once there is sufficient engagement and motivation to focus on the young person’s priorities, it may be helpful to gain more information about the presenting concerns. Within the context of HG therapy, Griffin and Tyrrell (Citation2003) offered a protocol for establishing more information about the presenting problem, through a series of open questions. These are shown in below:

Figure 2. Information gathering protocol (Griffin & Tyrrell, Citation2003).

While this protocol may be useful where the presenting concern is clear and well-defined (for example, anger, anxiety) often issues will be more nebulous and multifaceted. In such instances, using MI skills of open questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries, allows issues to be explored in a more discursive way, rather than as a “list” of questions, allowing a more open-ended and young person-centred discussion. Other activities which are potentially useful at this stage include the personal construct psychology-based “Ideal Self” task (Moran, Citation2001) (another example of therapeutic integration) or an audit of emotional needs (Human Givens Institute, Citation2006; or in card format [In8, Citation2016]). Both can also help to illuminate current issues and to help give the young person and EP a sense of possible ways forward.

Focussing/agenda setting

Focusing is a central process within MI (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) which allows therapeutic conversations to be directed to areas with are most important and salient to the needs of the young person. Roth and Pilling (Citation2007) described how CBT sessions should follow an agenda which is negotiated between the practitioner and client. However, it is worth acknowledging that this could pose a challenge for the EP, particularly if the young person’s priorities are not consistent with those of the commissioner or concern-holder. An example would be where a young person is referred because of a school-based behaviour which is causing concern (for example, non-compliance or underachievement) but the young person wishes to talk about other things (for example, relationships or concerns outside school). Even where the referred concern relates to a mental health concern, such as self-harm, or disordered patterns of eating, this may not be what the young person wishes to focus on.

While EPs need to be mindful of ethical and safeguarding responsibilities, there is importance in work being co-contracted, both from the perspective of addressing need and in terms of the young person’s engagement and motivation. Miller and Rollnick (Citation2013) noted that, as well as the focus for change coming from the client, it could also be linked to the context (for example, the school setting) and to factors identified by the practitioner, in this case the EP. It is therefore legitimate for the EP to make suggestions, whilst acknowledging that these might not necessarily reflect the priorities of the young person.

Procedurally, agenda-setting may take different forms. Miller and Rollnick (Citation2013) proposed using a “bubble chart” which involves listing possible areas for discussion on a sheet containing blank bubbles, or circles. These areas are then discussed and prioritised and a focus area agreed. In CBT, best practice requires collaborative working, thinking together and joint session planning or agenda setting. A key focus is on being child-centred (Fuggle et al., Citation2013) whereby the session is shaped actively by the child or young person. Many different techniques can be used, such as drawing, writing or pictures.

Goal setting

Goal setting is a key step in HG therapy. Griffin and Tyrrell (Citation2003) used the acronym PAN – positive, achievable and needs-focused – to define parameters of goals, but the authors’ practice experience suggests that positively worded goals are sometimes difficult for young people, and that using the young person’s own language (for example, staying away from the police; not smoking/drinking/using drugs) might also be an appropriate starting point. Using the SMART (specific, measureable, achievable, realistic and time-limited) acronym may therefore be a more familiar and useful framework for those working within education.

Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) advocated agreeing, monitoring and evaluating goals through the “Target Monitoring and Evaluation” system, which is a variant of goal attainment scaling (GAS) (Dunsmuir et al., Citation2009). This process allows goals to be made explicit and progress towards them regularly reviewed. Potentially, this increases the young person’s sense of agency in the intervention, and also provides feedback to the EP about the effectiveness of the intervention, and whether additional support and resources are needed. A freely available child-friendly version (Thomas & Atkinson, Citation2018) may be a useful resource in therapeutic goal-setting conversations.

Assessing motivation, resources and self-efficacy

If the young person is not ready to receive a particular intervention (for example, CBT) or not motivated for change, it is likely that they will not fully engage, or even avoid or withdraw from support (cf. Marker & Norton, Citation2018). Therefore, consideration needs to be given to assessing their readiness to change, and potentially to helping them to resolve ambivalence. Miller and Rollnick (Citation2013) stress the importance of scaling both motivation for, and confidence about, change using 10-point rulers. For example, a young person engaged in criminal behaviour might be highly-motivated to change, but have no confidence that this would be achievable (for example, because of gang involvement). For this reason, it is important to develop self-efficacy; essentially situation-specific self-confidence (Bandura, Citation1997).

In order to do this, it is important to help the young person access resources and skills which may have helped them before. This could be achieved via, for example, strengths-based assessment (Bozic, Citation2013) or by using open-ended questions, such as those exemplified in . Affirmations (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) are another way of both strengthening self-efficacy and identifying personal resources.

Joint formulation

Case conceptualisation (also known as formulation) is a collaborative process to describe and explain presenting issues, with a view to relieving distress and building resilience (Kuyken et al., Citation2009). It aims to develop a shared formulation which combines the young person’s understanding of their life with the EP’s theoretical and professional knowledge (Fuggle et al., Citation2013), allowing for a shared journey of discovery. Formulation should be fluid and new information can be incorporated as the intervention progresses and more information comes to light (Cartwright-Hatton et al., Citation2010).

A maintenance formulation enables exploration of five aspects of a young person’s life; thoughts, feelings, physiology and behaviours, under the umbrella of their environment or context (see for an example). Maintenance formulations also include additional information such as early life events, core beliefs and assumptions, and home, school and other relevant factors (see for an example). The information gathering protocol provided in may also be helpful in supporting the development of rich formulations.

Guided discovery/exploring change

Questioning assumptions is a key part of learning. Indeed Socrates considered questioning as synonymous with learning and the discovery of knowledge and understanding (Kazantzis et al., Citation2014).

Within the Socratic process as defined by Stallard (Citation2005), dialogue consists of three main phases:

Empathic listening

Ensuring the child feels understood

Exploration of evidence for their belief, considering:

How the young person has come to this belief or conclusion

Whether there might be another way of viewing the situation

Summarising to allow the young person to reappraise their beliefs based on the new knowledge

Kazantzis et al. (Citation2014) describe the importance of distancing oneself from one’s thoughts, through the process of questioning thoughts, beliefs, assumptions and rules, resulting in less rigid beliefs and assumptions and ideally creating distance between beliefs and assumptions contributing to emotional distress.

Skills building/intervention

Behavioural and cognitive techniques are useful in skills building and include behavioural activation and exposure. Behavioural activation aims to encourage the young person to make links between mood and activity and to monitor the impact of changing mood (Fuggle et al., Citation2013). For example, a useful intervention for a young person with mild to moderate depression might be to encourage them to approach activities they previously enjoyed and schedule some of these into their week, often with the support of friends or family; the idea being to support the young person to move away from inactivity towards a more positive active lifestyle. Preparing for scheduled activities requires careful consideration with manageable and achievable goals broken into small steps. If the young person finds this difficult, an opportunity is provided for discussion about obstacles and barriers. Ideally the young person’s autonomy should be maintained through supporting them to explore potential benefits, rather than direct persuasion. Exposure consists of slowly introducing the feared situation or object to the young person in a graded hierarchy of steps identified with the young person who, importantly, retains a high level of control of the process.

Other skills aimed at bringing about cognitive change include use of pie charts, surveys, scaling and rules for living worksheets (see Stallard, Citation2005), all of which support more adaptive coping and balanced thinking.

Planning strategies

Linked to skills-building is the idea of planning strategies. Because the young person is the expert in their own situation (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) they will arguably be better placed than the EP to ascertain which strategies could be successful. Therefore, wherever possible, it is better to elicit strategies from the young person (perhaps using some of the prompts in the accessing resources section above) and get them to assess the potential feasibility of these, before selecting the most appropriate. On some occasions, the EP might have a suggestion for something which might work for the young person, for example, the CBT broken record technique Footnote1(where the young person repeats a chosen phrase over and over again) for peer provocation. In this instance, (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) advocated the elicit-provide-elicit approach for asking permission to provide information, for example:

They sound like sensible strategies but they’ve not yet worked for you. I’m just thinking. There is a technique called ‘Broken Record’ which I know young people have used when they have been called names. Would it be helpful if I explained it?

Yeah, OK.

Using the elicit-provide-elicit approach, once the EP had then provided the information, they would then ask the young person for their thoughts.

Practising strategies

Griffin and Tyrrell (Citation2003) highlighted the importance of rehearsal (the final element of their six-point RIGAAR structure). This involves the young person practising any strategies within the safety and security of the therapeutic work, so that they may be skilled and fluent at using them in real time. Strategies could include role play, for example, with the EP taking on the role of perpetrator, or question and answer (for example, what if the person says this … ?). These could also include guided imagery, Griffin and Tyrrell (Citation2003) advocating for this to happen after progressive relaxation; or exploring scenarios through the medium of art or play. Once again, seeking the young person’s permission for these activities and asking them what their reflections were, using the elicit-provide-elicit approach is advocated.

Evaluation

Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) highlighted the need for accountable and evidence-informed practice, in advocating for evaluation of outcomes, satisfaction and service delivery to be incorporated into therapeutic practice. Although evaluation has strong links with the core principle of “feedback and reporting” (see ), it is also incorporated as a process element, as an activity which needs to be undertaken. Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) suggested that standardised behavioural and affective measures, observations and reports from supporting adults can be used to evaluate progress. They also advocated for the use of goal attainment scaling (see Goal setting) in allowing young people to review and revise self-set targets. Evaluation can also incorporate young people’s views about the EP’s role and to what extent it was experienced as being consistent with therapeutic principles (cf. Thomas & Atkinson, Citation2018).

Evaluation can incorporate pre-, post- and follow-up measures, session-by-session evaluation, or data from multiple sources (for example, young person, parent and teacher) (Dunsmuir & Hardy, Citation2016). Consideration should be given to the evaluation process at the outset of the intervention to ensure that the work completed is evidence-informed and appropriately targeted.

Planning for maintenance and relapse

In the event that the therapeutic intervention has been successful and has led to tangible changes or benefits, it is important that, particularly where EP involvement is coming to an end, plans are made for maintenance and relapse. Miller and Rollnick (Citation2013) noted that commitment to change tends to fluctuate and that it is important for those delivering therapeutic approaches to expect this to happen and empathise when it does. Atkinson and Amesu (Citation2007) described how solution-focused techniques, including reflections of change and reverse scaling (for example, “You’re at a 7 now. How would you know if you slipped back to a 6?”) can help inoculate against relapse and increase the young person’s awareness of when to seek help.

Limitations

It is possible that, for many practitioners, existing professional practice frameworks and/or the Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) DECP guidance are sufficient to guide therapeutic practice. For many, this proposed model might feel more like an example of showcasing therapeutic practice within the COMOIRA framework. However, from the authors’ experience of mapping therapeutic practice using COMOIRA, the generic practice framework does not give prominence to specific therapeutic processes and approaches. It is therefore hoped that the current model will provide greater direction for practitioners who would like a more structured approach to therapeutic intervention. Given that, unlike within clinical settings, the nature of the young person’s needs, as well as the most effective way to proceed, may not be well-defined, it also provides guidance for integrative therapeutic approaches, which can be responsive and flexible, as opposed to problem-focused or disorder-specific (for example, trauma-focused) models.

It should be noted that, like other models of professional practice (cf. Gameson et al., Citation2003; Monsen et al., Citation1998) this therapeutic framework is not empirically derived, and while it is evidence-informed, it is not evidence-based. The model requires testing, and further research aimed at refining and improving it is strongly encouraged.

While the model proposes a flexible framework for practice and also references the RIGAAR structure, it does not specifically highlight the key concept of beginnings, middles and endings (cf Mearns et al., Citation2013). Thus, it is important that the work is appropriately contracted in accordance with these key principles and that the conclusion of the work is agreed by, and comfortable for, both parties. In cases where, at the end of the intervention, additional support is required, appropriate signposting or referral to other services, shared discussions with key members of staff and/or parents, and contingency plans for when things do not go according to plan are all recommended.

The model incorporates three therapeutic approaches, assimilating what the authors believe to be their key strengths: the relational components from MI; the technical skills from CBT; and the structure from HG. However, there may be room for strong elements from other therapeutic approaches, such as narrative or family therapy to be incorporated, which strengthen the model.

Finally, while this model refers to training and supervision, it does not specifically advocate practitioner development. Competency benchmarking should form part of ongoing practice reflection and be integral to supervision. For this, protocols such as those offered within CBT (Roth & Pilling, Citation2007) or MI (Moyers et al., Citation2014) are advocated.

Conclusion

This paper presents a professional therapeutic practice model for EPs. It is focused particularly on the direct delivery of therapeutic approaches, designed to complement guidance from Dunsmuir and Hardy (Citation2016) and based on COMOIRA and the therapeutic modalities of CBT, HG and MI. It is not anticipated to be a definitive practice model and should be subjected to on-going review via practice and research. The authors would very much welcome practitioner liaison, debate and discussion about how to progress the model to maximise its usefulness, relevance to EP practice, and capacity to improve outcomes for children and young people. Considering therapeutic approaches within such a framework aims to expand thinking and shift practice from the sometimes narrow focus of individual therapy, whilst encouraging the EP to consider therapeutic practice within the broadest of meanings. With the advent of more therapeutic working within schools, it is prudent that EPs examine and explore broader frameworks and models of practice which incorporate therapeutic practice and principles within them. This model is just one example. Using such models may also support research into effectiveness of therapeutic approaches and in particular help identify the key mechanisms of change within practice.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Geolocation information

Keywords have been selected which are relevant to the article and to searches undertaken within this study. Author ORCID identifiers have been included where appropriate.

Notes

1. Broken Record (Smith, Citation1975), is an approach which involves repeating the same agreed phrase over and over again.

References

- Atkinson, C., & Amesu, M. (2007). Using solution-focused approaches in motivational interviewing with young people. Pastoral Care in Education, 25(2), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0122.2007.00405.x

- Atkinson, C., Bragg, J., Squires, G., Muscutt, J., & Wasilewski, D. (2011). Educational psychologists and therapeutic interventions: Preliminary findings from a UK-wide survey. Debate, 140, 6–12. https://shop.bps.org.uk/decp-debate-140-september-2011

- Atkinson, C., & Earnshaw, P. (2019). Motivational cognitive behavioural therapy. Routledge.

- Atkinson, C., Thomas, G., Goodhall, N., Barker, L., Barker, L., & Barker, L. (2019). Developing a student-led school mental health strategy. Pastoral Care in Education, 37 (1), 3–25. Published online 9th February. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2019.1570545.

- Attwood, S., & Atkinson, C. (2020). Supporting a post-16 student with learning difficulties using human givens therapy. Educational and Child Psychology, 37(2), 34–47. http://shop.bps.org.uk/educational-child-psychology-vol-37-no-2-june-2020-working-with-young-people-aged-16-25-part-1

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publishers.

- Boden, T. (2020). Cognitive behavioural therapy in a further education setting to support an adolescent experiencing low mood. Educational and Child Psychology, 37(3), 40–55. http://shop.bps.org.uk/educational-child-psychology-vol-37-no-3-september-2020-working-with-young-people-aged-16-25-part-3

- Bozic, N. (2013). Developing a strength-based approach to educational psychology practice: A multiple case study. Educational and Child Psychology, 30(4), 18–29. https://shop.bps.org.uk/educational-child-psychology-vol-30-no-4-december-2013-strength-based-practice

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments in nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage.

- Cartwright-Hatton, S., Laskey, B., Rust, S., & McNally, D. (2010). From timid to tiger: A treatment manual for parenting the anxious child. John Wiley and Sons.

- Chen, S. P., Chang, W. P., & Stuart, H. (2020). Self-reflection and screening mental health on Canadian campuses: validation of the mental health continuum model. BMC Psychology,8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00446-w

- Cryer, S., & Atkinson, C. (2015). Exploring the use of motivational interviewing with a disengaged primary-aged child. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(1), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2014.988326

- Department of Health, & Department for Education. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. DoH/DfE. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf

- Dunsmuir, S., Brown, E., Iyadurai, S., & Monsen, J. (2009). Evidence‐based practice and evaluation: From insight to impact. Educational Psychology in Practice, 25(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360802697605

- Dunsmuir, S., & Hardy, J. (2016). Delivering psychological therapies in schools and communities. BPS.

- Eddleston, A., & Atkinson, C. (2018). Educational Psychology in Practice theory, research and practice in educational psychology Using professional practice frameworks to evaluate consultation. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(4), 430–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2018.1509542

- Fallon, K., Woods, K., & Rooney, S. (2010). A discussion of the developing role of educational psychologists within Children’s Services. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360903522744

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Cottrell, D., Phillips, J., & Kurtz, Z. (2002). What works for whom? A critical review of treatments for children and adolescents. The Guilford Press.

- Fuggle, P., Dunsmuir, S., & Curry, V. (2013). CBT with children, young people and families. Sage.

- Gameson, J., Rhyddrech, G., Ellis, D., & Carroll, T. (2003). Constructing a flexible model of integrated professional practice: Part 1 – Conceptual and theoretical issues. Educational and Child Psychology, 20(4), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667361003768476

- Gibbs, S., Atkinson, C., Woods, K., Bond, C., Hill, V., Howe, J., & Morris, S. (2016). Supervision for school psychologists in training: Developing a framework from empirical findings. School Psychology International,37(4), 410–431.

- Griffin, J., & Tyrrell, I. (2003). Human givens: The new approach to emotional health and clear thinking. HG Publishing.

- Hill, V., & Murray, A. (2019). Investigating the impact of changes in funding on access to an Educational Psychologist and EP service delivery in England. Paper presented at Division of Education and Child Psychology Conference, Bath, 10 January.

- House of Commons Education and Health and Social Care Committees. (2018) . The government’s green paper on mental health: Failing a generation. House of Commons.

- Human Givens Institute. (2006). Emotional needs audit. Human Givens Institute. Retrieved January 17, 2020, from www.enaproject.org

- In8. (2016). Anxiety freedom cards. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: In8. https://www.in8.uk.com/

- James, A., Soler, A., & Weatherall, R. (2007). Cochrane review: Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 2(4), 1248–1275. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.206

- James, A. C., James, G., Cowdrey, F. A., Soler, A., & Choke, A. (2015). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (Review). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004690.pub4.www.cochranelibrary.com

- Kazantzis, N., Fairburn, C. G., Padesky, C. A., Reinecke, M., & Teesson, M. (2014). Unresolved issues regarding the research and practice of cognitive behavior therapy: The case of guided discovery using Socratic Questioning. Behaviour Change, 31(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2013.29

- Kelly, B., Woolfson, L., & Boyle, J. (Eds). (2008). Frameworks for practice in educational psychology. Jessica Kingsley.

- Kuyken, W., Padesky, C. A., & Dudley, R. (2009). Collaborative case conceptualization: Working effectively with clients in cognitive-behavioral therapy. PsycNET. Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-19087-000

- Leadbetter, J., Daniels, H., Edwards, A., Martin, D., Middleton, D., Popova, A., Warmington, P., Apostolov, A., & Brown, S. (2007). Professional learning within multi-agency children’s services: Researching into practice. Educational Research, 49(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880701200815

- Lee, K., & Woods, K. (2017). Exploration of the developing role of the educational psychologist within the context of “traded” psychological services. Educational Psychology in Practice, 33(2), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2016.1258545

- MacKay, T., & Greig, A. (2007). Editorial. Educational and Child Psychology, 24(1), 4–6. https://shop.bps.org.uk/educational-child-psychology-vol-24-no-1-2007-therapy

- Marker, I., & Norton, P. J. (2018). The efficacy of incorporating motivational interviewing to cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders: A review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 62(April), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.04.004

- Mearns, D., Thorne, B., & McLeod, J. (2013). Person-centred counselling in action. Sage.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing, third edition: Helping people change. Guilford Press.

- Miller, W. R., & Rose, G. S. (2009). Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. The American Psychologist, 64(6), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016830

- Minami, T., Andrews, W. P., Wislocki, A. P., Short, F., & Chow, D. (2013). A five-year evaluation of the Human Givens therapy using a practice research network. Mental Health Review Journal, 18(3), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-04-2013-0011

- Monga, S., Young, A., & Owens, M. B. (2009). Evaluating a cognitive behavioural therapy group program for anxious five to seven year old children: A pilot study. Depression and Anxiety, 26(3), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20551

- Monsen, J., Graham, B., Frederickson, N., & Cameron, R. J. (Seán). (1998). An accountable model of practice. Educational Psychology in Practice, 13(4), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266736980130405

- Moran, H. (2001). Who do you think you are? Drawing the Ideal Self: A technique to explore a child’s sense of self. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 6(4), 599–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104501006004016

- Moyers, T. B., Manuel, J. K., & Ernst, D. (2014). Motivational interviewing treatment integrity coding manual 4.1 (MITI 4.1), (December). University of New Mexico. http://casaa.unm.edu/download/MITI4_1.pdf

- Osborne, C., & Burton, S. (2014). Emotional literacy support assistants’ views on supervision provided by educational psychologists: What EPs can learn from group supervision. Educational Psychology in Practice, 30(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2014.899202

- Oxford English Dictionary (2020). OED online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved August 11, 2020, from www.oed.com/

- Prochaska, J. O., Norcross, J. C., & DiClemente, C. C. (1994). Changing for Good:A Revolutionary Six-Stage Program for Overcoming Bad Habits and Moving Your Life Positively Forward. Quill.

- Public Health England. (2015). Promoting children and young people’s emotional health and wellbeing A whole school and college approach.

- Rhydderch, G., & Gameson, J. (2010). Constructing a flexible model of integrated professional practice: Part 3 - the model in practice. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(2), 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667361003768476

- Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy. Houghton Mifflin.

- Roth, A. D., & Pilling, S. (2007). The competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for people with depression and with anxiety disorders. Department of Health.

- Sadler, D. K., Vizard, T., Ford, T., Marcheselli, F., Pearce, N., Mandalia, D., … McManus, S. (2018, March). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017 Summary of key findings. Health and Social Information Centre, NHS Digital. http://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017

- Sharpe, H., Ford, T., Lereya, S. T., Owen, C., Viner, R. M., & Wolpert, M. (2016). Survey of schools’ work with child and adolescent mental health across England: A system in need of support.”. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21(3), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12166

- Simpson, J., & Atkinson, C. (2019). The role of school psychologists in therapeutic interventions: A systematic literature review. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 1–15. ( Published online 6 December). https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1689876.

- Smith, M. J. (1975). When i say no, i feel guilty: How to cope, using the skills of systematic assertive therapy. Bantam Books.

- Squires, G. (2010). Countering the argument that educational psychologists need specific training to use cognitive behavioural therapy. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 15(4), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2010.523211

- Stallard, P. (2005). A clinician’s guide to Think Good Feel Good: The use of CBT with children and young people. John Wiley.

- Thomas, G., & Atkinson, C. (2018). Child attainment goal scaling and session outcome rating scales. In C. Allen, C. Atkinson, & G. Thomas (Eds.), Motivational interviewing amongst United Kingdom educational psychologists: Opportunities for practice development(pp. 23). University of Manchester. Retrieved January 04, 2021, from https://4f274257-ee67-446f-9523-7bccb642df4b.filesusr.com/ugd/79e42a_f02596bfc83f4738b4d5f9d326294599.pdf

- Thomas, G., Atkinson, C., & Allen, C. (2019). The motivational interviewing practice of UK educational psychologists. Educational and Child Psychology, 36(3), 61–72. https://shop.bps.org.uk/educational-child-psychology-vol-36-no-3-september-2019-selected-papers

- Waite, M., Atkinson, C.,& Oldfield, J. (2021). The mental health and emotional needs of secondary age students in the United Kingdon. Pastoral Care in Education.

- Weare, K. (2015). What works in promoting social and emotional well-being and responding to mental health problems in schools? Advice for Schools and Framework Document. National Children’s Bureau.

- Yates, Y., & Atkinson, C. (2011). Using Human Givens therapy to support the well‐being of adolescents: A case example. Pastoral Care in Education, 29(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2010.548395

- Zarbo, C., Tasca, G. A., Cattafi, F., & Compare, A. (2016). Integrative psychotherapy works. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(January), 2015–2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02021