ABSTRACT

This two-part study investigated how educational psychologists (EPs) might support schools working with young people (YP) with eating disorders (EDs). Part one explored the current support in UK schools for secondary-aged pupils with EDs, and the areas that parents (n52) and school staff (n39) felt needed further development, using online questionnaires. Data were analysed, using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis to inform the focus for semi-structured interview questions for part two, whereby eight EPs offered their views on aspects highlighted in part one. Ways forward are discussed, including how input to schools could be implemented. In summary, staff and parents considered that the support schools offered could be greatly enhanced. Four themes emerged from the EP data, which included recommendations for EPs to improve the support around EDs in schools. This study highlights the potential role EPs could have in supporting schools, working with YP with EDs, and their families.

Introduction

Mental health

The number of YP experiencing mental health (MH) difficulties in the UK continues to rise, (National Health Service [NHS], 2018a). A recent consultation in England has focussed on improving MH support in schools, for example, ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: a Green Paper’ (Department for Education & Department of Health [DfE & DoH], Citation2017), setting out plans for the improvement of practice in MH support in schools with the creation of mental health support teams (MHSTs). Recommendations included the introduction of ‘group-based interventions engaging participants in critiquing the “thin ideal”, which can be effective in reducing eating disorder symptoms and body image concerns, when targeted toward high-risk adolescent girls’. (DfE & DoH, Citation2017, p. 22). Despite positive movements forward, it is unclear how this will be undertaken regarding specific MH difficulties, for example, eating disorders (EDs).

Eating disorders

EDs ‘develop to deal with problems in a variety of areas of life’, including emotional and personal conflicts (Mehler & Andersen, Citation2017, p. 6). They are complex conditions, which are believed to be multifactorial (Aquilina et al., Citation2014; Lask & Bryant-Waugh, Citation2013). In 2013, the Diagnostic Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) revised the ED section to include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED). Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) is a category describing individuals whose symptoms do not fit the aforementioned criteria yet are still clinically severe (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

Knightsmith (Citation2015, p. 17) stated that AN, BN and BED are the ‘three major types of eating disorders’, as ‘what all three have in common is that the sufferer is using their food intake, their weight, or their shape as a way of coping’. It is estimated that of those with an ED, 10% have AN, 40% BN, and the rest have either BED or OFSED (Priory Group, Citation2018). Other EDs exist in the DSM-5; however, these may be associated with medical, sensory, and neurodevelopmental diagnoses, where there is less focus on weight loss and body image (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). As the onset of EDs are typically in adolescence (Knightsmith, Citation2015), this study focuses on secondary-school age pupils with EDs.

UK figures estimate that 1.6 million people have an ED, approximately 2.4% of the population (Priory Group, Citation2018). The rate of EDs for those under the age of 25 is double this (Mental Health Foundation Mental Health Foundation, Citation2016), highlighting that this is a significant area of MH affecting YP.

Current clinical interventions for EDs

Without treatment it is rare that individuals with EDs recover, whereas early intervention increases the chances of this (Knightsmith, Citation2015). Presently, EDs are typically treated in therapy using approaches including cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and family-based treatment (National Health Service, Citation2018b). Treatment can be provided by child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS; Knightsmith, Citation2015): nevertheless, research suggests that outcomes have not improved for AN patients since the 1980s (Murray et al., Citation2018). There is a moderately high drop-out rate amongst this population, leaving many chronically ill (Hilbert et al., Citation2012). Additional systemic factors can influence access to treatment, for example, long waiting periods (Beat Eating disorders [BEAT, Citation2015]), suggesting that an enhanced approach to supporting the recovery of YP with EDs could be beneficial. Understanding how key systems surrounding these individuals could meet their needs may be pertinent.

EDs and systems

Research suggests that sociocultural influences affect the aetiology of EDs (Culbert et al., Citation2015), and Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) identified the two systems closest to YP (microsystem) as their school and home.

The home system

Government guidelines highlight the importance of listening to the voices of parents and YP (UK Government, Citation2014), yet there is some concern as to how well this is being achieved currently. For example, McCormack and McCann (Citation2015, p143) noted that there ‘is a distinct lack of studies’ exploring the views of parents of YP with EDs. Findings by Mitrofan et al. (Citation2019) identified the benefits of a more person-centred support for both YP and their parents. Furthermore, Jungbauer et al. (Citation2016, p. 1) described siblings of individuals with EDs as ‘the forgotten kin’, ‘overlooked by both researchers and clinicians’; ultimately finding that they wanted to receive support themselves. Therefore, it appears that parents and siblings are yet to express their voices fully.

The consequences of this omission cannot be overestimated as caring for a person with MH difficulties can influence one’s psychological wellbeing (McCormack & McCann, Citation2015). Family-based therapy is considered to be an effective form of intervention for YP with EDs (Robinson et al., Citation2015), further highlighting the need for practitioners to both seek views and identify needs.

The school system

YP can spend approximately 25-27.5 hours a week in education (Long, Citation2019), making the school an important part of the microsystem. For pupils with EDs, understanding how school systems address and support them could be a component of the overall management of their difficulties.

Although school staff have a role in early identification of EDs (DfE & DoH, Citation2017), research exploring their awareness of EDs is limited. Current findings suggest that there is a paucity of understanding and knowledge about EDs, and school staff do not feel comfortable discussing the issues with pupils (Knightsmith et al., Citation2013). highlights some of the interventions that have been researched following implementation in school environments; however, only two of these are UK based. Knightsmith (Citation2015) identified strategies schools could implement to support the needs of YP with EDs, including increasing staff competency through training, and providing strategies and practical ideas; the value of clear policies; and the need for effective procedures for YP reintegrating back into school having had an extended absence due to their ED. Dror et al. (Citation2015) suggested successful reintegration is more likely when using a staged approach with a multi-disciplinary (MD) team.

Table 1. ED intervention/prevention programmes

Schiele (Citation2016) explored provisions offered to YP with EDs in the US through interviewing YP and their mothers, with questionnaires completed by 561 school mental health (SMH) staff. Within the US, SMH professionals are those who offer input within school settings and could include school and clinical psychologists, counsellors and therapists. The types of support identified within this study included; consultation, educating students, referral to medical professionals for assessment, and some listed individual therapy. All parents felt SMH staff could provide input for families of YP with EDs, for example, links to resources. Data may not be generalisable to UK schools that have a different curriculum to USA schools (Relocate Global, Citation2019) or specifically UK educational psychologists (EPs), but it highlights that school-based MH professionals and schools might provide support.

In summary, the research base regarding the support for YP with EDs in UK schools is limited, and the empirical evidence available suggests that the support offered could be enhanced: this may be beneficial for these pupils and their families.

The role of the EP and EDs

With increased focus on MH needs in schools, EPs are undertaking more work in this area (Price, Citation2017). Methods used include multi-agency work, training, consultation, assessment, increasing awareness, and preventative work (Price, Citation2017). Many consider that it is important that the EP profession supports the MH needs of pupils, confident in their abilities to provide input around MH through guiding schools, staff training, parent interventions, and direct work with pupils (Greig et al., Citation2019). Barriers to this identified include EPs’ view of their role in relation to MH being significantly different to how others view this, for example, schools, and government (Greig et al., Citation2019).

The American National Eating Disorder Association’s (NEDA, Citation2019) ‘Educator’s Toolkit’ provides guidance on how US school psychologists can support schools. American school psychologists are noted as having a similar role to a UK EP (Watkins et al., Citation2001; Bardon, Citation2017) as both roles include a diversity of responsibilities that can include assessing the needs of YP, planning and developing interventions, offering individual support, and training for staff working with pupils with EDs. The Educator’s Toolkit document discusses: creating a healthy school environment, for example, intolerance of appearance-based bullying; approaching YP at risk of EDs; helping schools devise ways to reduce workloads; facilitating successful reintegration; and supporting the YP and their family. Similar research exploring the potential role for EPs in relation to aiding UK schools in the management of EDs is required.

Academic and professional rationale for the current research

As discussed, EPs are increasingly providing input regarding MH needs by working with key adults in microsystems (Greig et al., Citation2019). However, the current literature exploring how EPs are undertaking work around specific MH difficulties, such as EDs, is limited. Recovery rates of some EDs have not improved since the 1980s (Murray et al., Citation2018), thus suggesting a need for an enhanced approach. There are gaps in the empirical evidence surrounding the support in UK schools for EDs, from a parental and school perspective. EPs could be well placed to work collaboratively with adults within home/school microsystems and mesosystem. Therefore, the question of how EPs can utilise their skills to make positive changes for YP with EDs is raised.

This study will discuss the current practice in schools focussed on EDs, and the role of EPs. Four questions will be explored:

What is the current practice in schools when supporting a YP with an ED?

What are the views of parents and carers of YP with EDs about the support being provided for their child within the school setting?

What support do school staff and parents/carers feel is necessary, and would like to receive?

What are the views of practising EPs about how the profession could better support schools to meet the needs of YP with an ED?

Methods and measurements

Design

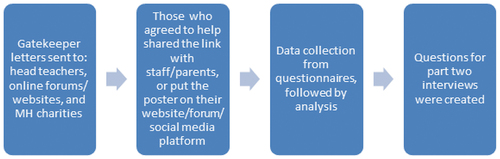

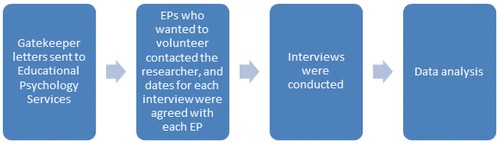

This study adopted a Critical Realist paradigm, the epistemological standpoint was Contextualism (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Braun and Clarke, Citation2021). Part one collected data from 39 school staff and 52 parents using online questionnaires (). The outcomes were used to inform questions for semi-structured interviews in part two (). A combined methods approach was adopted (Lindsay, Citation2013).

Recruitment and participants

Target populations were split into three: school staff, parents, and EPs ().

Table 2. Staff and parent participant information

Table 3. EP participant information

Piloting

A pilot study was conducted independently to explore the feasibility of the research approach used, following which appropriate amendments were made (Leon et al., Citation2011).

Data collection and analysis

Qualtrics was used to gather data in part one, which were then analysed and reported using descriptive statistics. The model of profoundisation was used, whereby quantitative methods produced results, which were subsequently explored using qualitative methods to ‘enrich or tease out important aspects of the data’ (Fisher & Warren, Citation2011, p. 676). Guidelines by Roopa and Rani (Citation2012) were followed to increase the validity and reliability of the data collected in part one: a process that starts with the initial considerations through to formulating question content, phrasing, sequence, and layout, followed by a pilot with revisions, before arriving at the final questionnaire.

Once transcribed, the qualitative data from the interviews were analysed inductively, using reflexive thematic analysis (TA) following the steps highlighted by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013), pp. 202-203; Braun and Clarke (Citation2021). Themes and sub-themes were reviewed by an independent researcher. Yardley’s (Citation2000, Citation2008) ‘neutral’ validity principles were used as a framework to assess the quality of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013, pp. 289-290)

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was gained from the Ethics Committee of Cardiff University School of Psychology (EC.19.03.12.5593).

Findings

Part one sought to ascertain the knowledge and understanding of school staff and parents, as well as their views on current practice and policies and the support being offered, whereas part two focussed on the responses from practising EPs regarding how the profession could better support schools. Key findings are reported below (; ): for further details see, Elms (Citation2020).

Table 4. Key findings from school staff questionnaire

Part one: school staff

Descriptive statistics

Outcomes reflected a positivity and willingness to address and support the needs of YP with EDs, acknowledging a need for more to be done in areas such as training of school staff, support and interventions.

Thematic analysis of staff views

‘Support’ highlights that school staff considered that more individualised and flexible support for pupils with EDs is needed, yet noted the barriers (paucity of training and funding). ‘Working Together’ considered views on the need to increase collaborative working and communication between key people. Within ‘School Systems’ issues relating to the whole-school system were highlighted, for example, importance of a key person, increasing student knowledge and understanding, and having a positive whole-school approach.

Part one: parents

Descriptive statistics

Similar to above, the views of parents (; ) reflected experiences of inadequate knowledge and understanding of school staff, a paucity of support being offered and a need for more to be done in terms of collaboration and implementation of preventative measures.

Table 5. Key findings from parent questionnaire

Thematic analysis of parental views

‘The Needs of the YP with an ED’ encapsulated views regarding the limited support currently within school systems, and needs such as increasing knowledge and awareness of school staff and pupils; more effective reintegration practice; the importance of having a key staff member; providing a positive/safe place for pupils; and the dangers of healthy eating talks.

‘Needs of the Family’ highlighted how interactions between people in the school system could influence the development and recovery of EDs, for example, with parents, external professionals, and through supporting siblings.

Part two: EP interviews

The EPs discussed how the profession could provide input around EDs to schools. Four themes were identified presented in four thematic maps ().

Gaps in support being offered to pupils were highlighted in the theme ‘Not Enough’, along with possible explanations for these (lack of both confidence and capacity, messages being shared in healthy eating talks, limited training of school staff).

‘The ED Friendly School’ considers the various ways support could be improved, for example, increasing the understanding of school staff and having clear boundaries for their roles; awareness of EDs amongst pupils to empower them to support friends; ensuring a graduated response; positive relationships; effective polices that take account of the needs of those with EDs, and embedding health/wellbeing into the curriculum.

In the third theme ‘Family’, the importance of listening to the views of parents was discussed, noting that parents’ needs do not appear to be met (and the difficulties that then result); the potential value of increasing knowledge and understanding so parents can identify EDs early in their emergence was highlighted; and finally the unmet needs of siblings for support was raised.

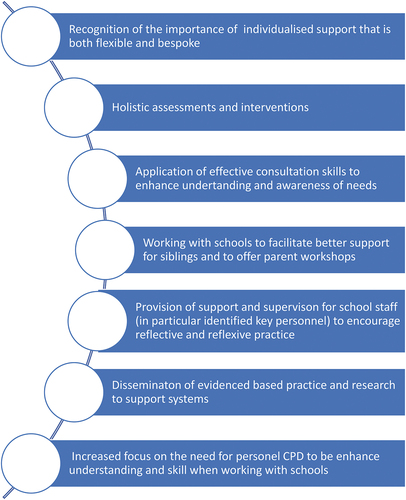

Finally, ‘The EP Offer’, () emphasised the skills EPs possess, which they could call upon when supporting schools working with pupils with EDs; for example, consultation, holistic assessment, running staff training and parent workshops, their knowledge and understanding of school and wider systems, and how to support these (through evidence-based practice/research). EPs discussed how many people do not understand their role, and the importance of having boundaries between the roles of clinical and educational psychologists.

Summary

The data provided by the three participant groups were generally in accordance, with a strong consensus on how support for YP with EDs could be enhanced. represents areas of concordance and variation in the degree to which themes were referenced. The EPs discussed how the profession could facilitate positive changes in their role().

Discussion

Through the lens of the key systems that influence YP’s development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979), this study explored the work being done in UK schools in supporting YP with EDs with a particular focus on how EPs could enhance outcomes. There were many similarities to the views of the three participant groups, such as the importance of individualised support. Issues raised highlighted aspects such as the limitation of resources available, and the need for better collaboration. Distinctive findings included proposals for how EPs could provide input (for example, consultation), and parental views of managing peers.

The four research questions will be addressed individually, although question 4 will be considered throughout.

RQ1: What is the current practice in schools when supporting a YP with an ED?

All school staff agreed that supporting the needs of YP with EDs was part of the role of a school, yet only 46% felt their school was effectively achieving this. The support available included Mindfulness, signposting, counselling, and reasonable adjustments: only 18% of schools organised individual therapy sessions. BEAT (Citation2015) discussed long waiting times for individuals with EDs to receive treatment from healthcare services, and data from the current study indicates support in schools is limited.

Findings also indicated that a limited amount of prevention or intervention work focussed on EDs is being undertaken in schools, with only 15% reporting their school ran programmes (unnamed). However, all groups highlighted the need for ‘Early Identification’ through ‘Preventative’ work and ‘Interventions’. When making a CAMHS referral, Knightsmith (Citation2015, p. 132) suggests school should ‘provide details of any interventions’ and evidence of their impact, as CAMHS are ‘more likely to work first with the more complete referral’. It appears few programmes are being run in schools; therefore, it could be difficult for the staff to discuss a ‘graduated response’ when writing referrals. This may influence how quickly/if YP with EDs receive input from CAMHS, and their road to recovery.

All three participant groups identified the need to increase knowledge and understanding of EDs. Within ‘But need more’ the school staff identified ‘Effective training’ and EPs were not aware of any training offered in this area, which impacted on understanding and confidence. Parents, too, believed ‘School system’s knowledge, understanding and awareness’ was an aspect to be improved upon. 60% of school staff had not received training on EDs, below the 74% found by Knightsmith et al. (Citation2014). Knightsmith et al. (Citation2013) suggested many staff do not possess a basic understanding of EDs. As school staff are well placed to identify early signs of EDs (Knightsmith, Citation2015) a lack of training reduces the chances of ‘Early identification’, suggesting training could be a viable strategy. This could be facilitated by EPs by providing this input as ‘Educators’.

Approximately half of the school staff respondents reported their school had policies to address the needs of pupils with EDs, although only 50% of these felt they were effective. Aspects such as ‘Ethos’ were discussed. These will be addressed in further detail in the subsequent section (RQ2).

When asked about barriers being encountered, school staff identified ‘Funding’, and EPs felt ‘Schools have so much on their plates’. EPs identified the negative impact of limited resources on their practice, the ‘EP role has shrunk’, discussing how this then contributed along with a lack of a perception of EPs as being able to support MH needs, reflecting findings by Greig et al. (Citation2019). Recent data found that ‘93% of EP services were experiencing more demand than could be currently met’, considered as being due to an ‘increase in statutory assessment work’ and ‘a shortage of EPs in LAs’ (Department for Education, Citation2019, p. 7). The estimated cost for ED treatment is between £3.9 and £4.6 billion for the NHS (BEAT, Citation2015), however, services are stretched financially (McIntosh, Citation2017). It could be argued that a focus on early identification/prevention of EDs, supported by EPs, could potentially save public services money further down the line, thus alleviating some pressures and so providing good cost-effectiveness.

RQ2: What are the views of parents and carers of YP with EDs about the support being provided for their child within the school setting?

Overall, there was a high degree of consistency in the views of the parents. The data suggests that parents are not satisfied with the support provided by schools, for example, only 14% of parents believed it was adequate and 86% of parents felt the succour given by their child’s school was ineffective. The findings of Schiele (Citation2016) completed in the USA, contrast with this. Possibly, UK school staff lack sufficient understanding of EDs due to limited training, concurring with findings by Knightsmith et al. (Citation2013). Nevertheless, 74% of parents felt that staff were concerned about their child’s wellbeing, suggesting school staff are empathetic yet perhaps are not sure how to improve how they work with pupils.

In response to increasing obesity rates amongst children and YP, the government focused on healthy eating in schools, both in lessons and food served (Healthy Schools, Citation2008). Some parents discussed the negative effects of ‘Healthy eating’, which was echoed by EPs (‘Food isn’t ‘good’ or ‘bad”). Participants believed more positive messages around food may avoid the development of poor body image in pupils. Sadegholvad et al. (Citation2017) explored the views of food-related professionals on nutrition and food education programmes in Australia through interviews. One emergent sub-theme was about nutrition messages, identifying the need to reframe negative and prohibiting views of food. Further research on how healthy eating talks in UK schools are being delivered could be beneficial, offering a deeper understanding of the messages around food that are being presented and construed by children and YP.

Both school staff and parents understood the importance of effective communication between home and school (‘Parents’, ‘Enhancing home-school collaboration’). Additionally, parents reported that school staff were rarely involved in meetings regarding their child; however, 94% felt that they should be. Mirroring this was school staff, who discussed working with ‘External agencies’, and the EPs who identified that key parties should be ‘Working together’. Knightsmith (Citation2015) highlighted the importance of positive relationships between key adults from all systems around a pupil with an ED, and a consistent and collaborative approach between school and external agencies. MD working could better achieve early identification of needs and promote ‘co-ordinated service provision’ (Knightsmith, Citation2015, p. 133). Farrell et al. (Citation2006) suggest that EPs’ skills and psychological knowledge, ability to work with various agencies, and awareness of LA provision could enable them to have a key role in this.

The EPs in this study reflected this, discussing ‘Systems’ work, and sharing psychology and evidence-based practice as part of them being ‘Schoolologists’. Farrell (Citation2009) suggested that for effective multi-agency work to occur, professional boundaries must be broken down and those involved should trust and place equal value on the opinions of everyone. In line with Farrell’s views, boundaries between clinical and EPs were highlighted in the current study (‘Understanding the EP role’), showing EPs are aware of the challenges MD working can present. EPs have been described as ‘the lynchpin between health and education’ (Roffey et al., Citation2018, p. 5). As YP with EDs are typically treated by healthcare professionals yet spend time in school, more joint work involving EPs, healthcare professionals, school staff, and parents could help improve communication across sectors, break down any existing barriers, encourage consistent support across home and school settings, and thus enable effective support in schools. Additionally, this could address parents’ views around involving school staff in MD meetings and increasing home-school communication.

Another area that some parents felt was lacking was ‘Reintegration’ back to school. For those whose child had been absent for an extended period, the effectiveness of the school support regarding the transition back varied. Knightsmith (Citation2015) discussed how returning to school could cause intense fear for YP who have experienced inpatient care and could trigger relapse if handled incorrectly. Also highlighted were several elements that should be considered during a reintegration, including: a phased return; consideration of academic pressures; identifying triggers, for example, bullying; awareness of signs of relapse; peer support; and ‘preparing school staff and peers for the student’s return’ (p. 142). EPs felt that they have the appropriate skills to support the transition of YP with EDs back into school, as ‘Reintegration’ is already part of their role. Limited research exploring the effective reintegration of YP with EDs appears to exist. However, the use of models such as Ecological Model of Successful Reintegration (Nuttall & Woods, Citation2013) could allow EPs to facilitate successful transition of pupils back into school, and help schools understand how to increase effective practice in this area.

Parents raised concerns over ‘Managing negativity of peers’, and the need for schools to be ‘A safe and positive place’ for pupils. Within this, they discussed wider issues around MH and the need for specific policies on EDs. EPs reiterated this and suggested incorporating the voices of parents and YP to increase efficacy (‘Policies’). The ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: a Green Paper’ highlights the importance of having policies to ‘tackle poor behaviour and bullying’ (DfE & DoH, Citation2017, p. 43) and promoting a whole-school approach to MH.

All three participant groups identified the need to include teaching about EDs in the ‘Curriculum’, to help increase ‘Student knowledge and understanding’. EPs and school staff also emphasised the importance of a ‘Whole-school approach’ and school ‘Ethos’. Roffey et al. (Citation2018, p. 5) discussed how EPs are ‘influencing policy and practice at other levels of the systems in which they work’. Furthermore, Roffey (Citation2016, p. 38) stated that EPs can influence whole-school wellbeing as they have the ‘knowledge and expertise’, which could include promoting relational approaches, which are ‘effective across the school system’. In summary, EPs could help schools develop effective policies and a whole-school approach. This could include focussing on positive ‘Relationships’ between school staff and pupils, and addressing bullying through increasing pupil knowledge and understanding of EDs to encourage more active peer support.

RQ3: What support do school staff and parents/carers feel is necessary, and would like to receive?

Parents and school staff highlighted the importance of an ‘Identified key person’ in each school who was knowledgeable about EDs, and who pupils could talk to (‘Key person’). EPs shared this view (‘Knowledge of EDs’). This is in line with the MH green paper (Department for Education & Department of Health, Citation2017, p. 4), which suggested that schools have a ‘Designated Senior Lead for Mental Health’. The paper stated that this role could include: supporting the development of a whole-school approach, which would include polices, curriculum and pastoral support; aiding early identification of YP experiencing MH difficulties; developing links with and knowledge of MH services; overviewing interventions; and supporting school staff in raising awareness.

Parents, school staff, and EPs identified that teaching pupils about EDs would be beneficial to help raise awareness and understanding of EDs (‘Peers’; ‘Student knowledge and understanding’; ‘Awareness’). Furthermore, parents and EPs felt that this knowledge could help pupils be supportive of individuals with EDs (‘How do I help my friend?’; ‘Support’). As peer groups can have both a negative and positive influence on YP’s eating attitudes and behaviours (Scott et al., Citation2019) increasing their knowledge and awareness of EDs could help students identify symptoms that friends exhibit early. Secondly, this could increase empathy towards those with EDs and may encourage pupils to share concerns with adults (Damour et al., Citation2015). Sessions to address this could be included as part of the curriculum, which EPs, parents and teaching staff felt could be positive for all students (‘Curriculum’; ‘Peers’; ‘Student knowledge and understanding’).

EPs felt that ‘Changes in eating at home’ were likely to be how EDs are first identified, so parents need to be better informed in order to spot symptoms, reflecting the findings of Schiele (Citation2016). Furthermore, Goodier et al. (Citation2014) found that a skill-based intervention programme for parents of YP with EDs is beneficial; parents reported the workshop had led to more open communication with their child, improved family dynamics, externalisation of the ED, and helped parents set boundaries, with positive emotional effects through sharing experiences with others. EPs in this study identified the difficulties experienced by parents, suggesting ‘Parent workshops’ were a possible way forward. As parents of YP with EDs do want more support (McCormack & McCann, Citation2015), this could be a viable strategy EPs could incorporate into their practice to support parents in understanding their child.

RQ4: What Are the Views of Practising EPs About How the Profession Could Better Support Schools to Meet the Needs of YP With EDs?

As identified above, there are many ways EPs could work with schools. EPs also highlighted specific skills that could be useful, such as consultation, holistic assessment, and supervision. EPs talked about the work surrounding EDs they had undertaken, and the limitations of this.

All three participant groups identified the need for ‘Individualised support’ that is ‘Flexible and bespoke’. EPs felt their strengths in taking a ‘Holistic’ approach and sharing evidence-based practice and research when working at the ‘Systems’ level would make a strong contribution. This is in line with the guidance for EPs produced by The British Psychological Society (Citation2015, p. 3), that ‘the EP provides a unique perspective, based on holistic assessment and child-centred approach and rooted in psychological theory’.

The school staff interviewed considered that those working with YP with EDs should receive support themselves (96%). EPs discussed how they could provide staff with ‘Supervision’ to meet this need. Reference was made to the Emotional Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) supervision model (Burton, Citation2011). Osborne and Burton (Citation2014) explored ELSA’s views on supervision run by EPs, finding that supervision was useful for discussing cases, problem-solving, sharing ideas, and enabling better support for students. EPs providing supervision for school staff could encourage reflective and reflexive practice, to improve the quality of support offered.

Both parents and EPs identified possible negative effects having a brother/sister with an ED could have on ‘Siblings’. The bespoke support provided by ELSAs in schools could also meet the needs of YP with EDs and/or their siblings.

Consultation is widely used by individual EPs (and as part of a model of service delivery), where individuals involved have ‘unique expertise that contributes’ to identifying possible solutions to move forward (Wagner, Citation2017, p. 195). EPs felt that their skills in ‘Consultation’ could be applied when working with EDs, for example, applying techniques such as reframing to facilitate change when working with key adults as well as jointly exploring possible ways forward to facilitate change (Gameson & Rhydderch, Citation2017), p.137.

Limitations, implications for EP practice, and conclusion

Limitations

Several limitations of this study are evident: the participants for part one were diverse with regard to geographical location and school types, however the overall sample size was relatively small. An omission was clarity about the specific EDs that were the focus of the study. Part-two enabled discussion of the challenges and ways forward for the EP population, underpinned by views from current practitioners, but it is acknowledged that a relatively small number of interviews were completed, from a limited base of local authorities. Additionally, the self-selecting nature of those interviewed meant that all had personal experience of EDs which may have resulted in some bias in what was offered. However, these findings may offer a helpful starting point for the profession, and future studies could develop and further understanding by broadening the scope in terms of participants and more actively seeking the voice of the young people themselves.

Implications for educational psychology practice

In addition, to the elements highlighted in RQ4 above regarding the implications for practice of EPs the following may be worthy of consideration. The EPs involved in this study considered that their knowledge base about EDs was inadequate. Given that EPs are working more with schools around MH difficulties (Greig et al., Citation2019), which would include support around EDs, it is suggested it is the responsibility of individuals to up-skill themselves on the impact of ED on the lives of young people. Once achieved, an EP would then be well placed to work with staff in schools, YP with EDs, their parents and siblings, as well as all pupils, improving knowledge and understanding of EDs and their impact educationally, as well as highlighting the important part that everyone has to play in both prevention and more effective intervention.

The profession could play an active and significant role in the provision of diverse and more flexible support for young people in schools. Examples would include recognition of the importance of holistic assessments and understanding of the impact of the system around a YP; the offer of support groups for YP and siblings; provision of workshops for families, and supporting schools in the identification and implementation of appropriate interventions. Finally EPs could have an important part to play in ensuring that school practice is evidence based and that all stake holders, YP, families, and schools are well informed with regard to current research findings.

Conclusion

The number of YP experiencing mental health (MH) difficulties in the UK continues to rise. This study set out to explore how EPs could better support schools in supporting young people with EDs. It is argued that EDs are an example of a specific MH need, where supporting the key systems surrounding these individuals could enhance the effectiveness of the outcomes, and that EPs have an important part to play in this. Findings suggested that families, school staff, and EPs view the awareness, understanding, policy and practice in schools as inadequate currently. Ways in which the EP profession could work with schools to enhance practice are highlighted, including the application of core EP skills such as the importance of working systemically; use of consultation; holistic assessments and interventions; the provision of bespoke and flexible support for young people, siblings and families; and working to better upskill parents and staff and indeed themselves.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.

- Aquilina, F. F., Agius, M., & Sharma, K. (2014). The multifactorial etiology of eating disorders outlined in a case of anorexia nervosa and complicated by psychiatric co-morbidities. Psychiatria Danubina, 26(1), 250–255. Accessed 3 March 2020. https://www.psychiatria-danubina.com/UserDocsImages/pdf/dnb_vol26%20Suppl%201_no/dnb_vol26%20Suppl%201_no_250.pdf

- Bardon, J. I. (2017). The school psychologist as an applied educational psychologist. In: The school psychologist in non-traditional settings (pp. 1–32). Routledge. Accessed 20 August 2021. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10>!-- -->.4324/9781315211893-1/school-psychologist-applied-educational-psychologist-jack-bardon

- BEAT. (2015). The cost of eating disorders: Social, health and economic impacts.:https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/uploads/documents/2017/10/the-costs-of-eating-disorders-final-original.pdf

- Berger, U., Schaefer, J. M., Wick, K., Brix, C., Bormann, B., Sowa, M., Schwartze, D., & Strauss, B. (2014). Effectiveness of reducing the risk of eating-related problems using the German school-based intervention program,“Torera”, for preadolescent boys and girls. Prevention Science, 15(4), 557–569. Accessed 3 March 2022. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11121-013-0396-4

- Bird, E. L., Halliwell, E., Diedrichs, P. C., & Harcourt, D. (2013). Happy Being Me in the UK: A controlled evaluation of a school-based body image intervention with pre-adolescent children. Body Image, 10(3), 326–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.02.008

- Braun and Clarke. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology 18(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage Publications.

- British Psychological Society. (2015). Guidance for Educational Psychologists (EPs) when preparing reports for children and young people following the implementation of the children and families Act 2014. file:///C:/Users/admin/Downloads/INF247%20DECP%20Guidance%20for%20Edu%20Psych%20WEB.pdf

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. United States of America: Harvard University Press.

- Burton, S. (2011). ELSA trainer’s manual: Practical and comprehensive training materials to support the emotional needs of pupils. Taylor and Francis Group.

- Culbert, K. M., Racine, S. E., & Klump, K. L. (2015). Research Review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders–a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(11), 1141–1164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12441

- Damour, L. K., Cordiano, T. S., & Anderson-Fye, E. P. (2015). My sister’s keeper: Identifying eating pathology through peer networks. Eating Disorders, 23(1), 76–88.

- Department for Education. (2019). Research on the educational psychologist workforce: Research report. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/people/clare/publications/research_on_the_educational_psychologist_workforce_march_2019_published.pdf

- Department for Education & Department of Health. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. Accessed 18 June 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf

- Diedrichs, P. C., Atkinson, M. J., Steer, R. J., Garbett, K. M., Rumsey, N., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Effectiveness of a brief school-based body image intervention ‘Dove Confident Me: Single Session’ when delivered by teachers and researchers: Results from a cluster randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 94–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.09.004

- Dror, S., Kohn, Y., Avichezer, M., Sapir, B., Levy, S., Canetti, L., Kianski, E., & Zisk‐Rony, R. Y. (2015). Transitioning home: A four‐stage reintegration hospital discharge program for adolescents hospitalized for eating disorders. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 20(4), 271–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12123

- Eickman, L., Betts, J., Pollack, L., Bozsik, F., Beauchamp, M., & Lundgren, J. (2018). Randomized controlled trial of REbeL: A peer education program to promote positive body image, healthy eating behavior, and empowerment in teens. Eating Disorders, 26(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2017.1349005

- Elms, B. (2020). An Exploration of Practice in Schools When Working with Young People with Eating Disorders, and Their Families; The Potential Role for Educational Psychologists. DEdPsy Thesis, Cardiff University.

- Farrell, P. (2009). The developing role of school and educational psychologists in supporting children, schools and families. Papeles del Psicólogico, 30(1), 74–85. Retrieved 3 March 2022. http://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es/English/1658.pdf

- Farrell, P., Woods, K., Lewis, S., Rooney, S., Squires, G., & O’Connor, M. (2006). A review of the functions and contribution of educational psychologists in England and Wales in light of “Every Child Matters: Change for Children”. DfES Publications.

- Fisher, A., & Warren, P. (2011). Statistics and research methods. Pearson Custom Publishing.

- Gameson, J., & Rhydderch, G. (2017). the constructionist model of informed and reasoned action (COMOIRA). In: B. Kelly, L. M. Woolfson, & J. Boyle (Eds), Frameworks for practice in educational psychology: A textbook for trainees and practitioners (second ed., pp. 123–150). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Goodier, G. H., McCormack, J., Egan, S. J., Watson, H. J., Hoiles, K. J., Todd, G., & Treasure, J. L. (2014). Parent skills training treatment for parents of children and adolescents with eating disorders: A qualitative study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(4), 368–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22224

- Greig, A., MacKay, T., & Ginter, L. (2019). Supporting the mental health of children and young people: A survey of Scottish educational psychology services. Educational Psychology in Practice, 35(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2019.1573720

- Health and Care Professions Council, (2016). Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. http://www.hcpc-uk.org/aboutregistration/standards/standardsofconductperformanceandethics/

- Healthy Schools. (2008). National healthy schools programme: Guidance for schools on healthy eating. https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/health/healthy-schools-london/awards/sites/default/files/HS%2520Healthy%2520Eating_1.pdf

- Hilbert, A., Bishop, M. E., Stein, R. I., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Swenson, A. K., Welch, R. R., & Wilfley, D. E. (2012). Long-term efficacy of psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 232–237. Accessed 19 December 2019. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/longterm-efficacy-of-psychological-treatments-for-binge-eating-disorder/62CB13193D0FA6FCD4E9990545A3BDB4

- Jungbauer, J., Heibach, J., & Urban, K. (2016). Experiences, burdens, and support needs in siblings of girls and women with anorexia nervosa: Results from a qualitative interview study. Clinical Social Work Journal, 44(1), 78–86. Accessed 19 December 2019. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10615-015-0569-7

- Knightsmith, P. (2015). Self-harm and eating disorders in schools: A guide to whole-school strategies and practical support. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Knightsmith, P., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2013). Spotting and supporting eating disorders in school: Recommendations from school staff. Health Education Research, 28(6), 1004–1013. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt080

- Knightsmith, P., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2014). We don’t know how to help: An online survey of school staff. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(3), 208–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12039

- Lask, B., & Bryant-Waugh, R. (2013). Eating Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Routledge.

- Leon, A. C., Davis, L. L., & Kraemer, H. C. (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(5), 626–629. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008

- Lindsay, G. (2013). The benefits of combined (mixed) methods research: The large scale introduction of parenting programmes. Social Work and Social Sciences, 16(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1921/swssr.v16i2.532

- Long, R. (2019). The School Day and Year (England). House of Commons Library.

- McCormack, C., & McCann, E. (2015). Caring for an adolescent with anorexia nervosa: Parent’s views and experiences. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(3), 143–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.01.003

- McIntosh, B. (2017). The election: Implications for the future of the NHS. British Journal of Healthcare Management, 23(5), 198–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2017.23.5.198

- Mehler, P. S., & Andersen, A. E. (2017). Eating disorders: A guide to medical care and complications. United States of America: John Hopkins University Press.

- Mental Health Foundation. (2016). Fundamental Facts About Mental Health 2016.

- Mitrofan, O., Petkova, H., Janssens, A., Kelly, J., Edwards, E., Nicholls, D., McNicholas, F., Simic, M., Eisler, I., Ford, T., & Byford, S. (2019). Care experiences of young people with eating disorders and their parents: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 5(1), 1–8. Accessed 17 December 2017. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-open/article/care-experiences-of-young-people-with-eating-disorders-and-their-parents-qualitative-study/4CC22A8267C17B8C96F65CAC8ED882C2

- Murray, S. B., Quintana, D. S., Loeb, K. L., Griffiths, S., & Le Grange, D. (2018). Treatment outcomes for anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychological Medicine 49(4), 535–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718002088

- National Eating Disorder Association. (2019). Educator’s Toolkit. Retrieved 16 July 2019.https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/sites/default/files/Toolkits/EducatorToolkit.pdf

- National Health Service. (2018a). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-healthof-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017on30/11/18

- National Health Service. (2018b). Treatment: Anorexia Nervosa. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/anorexia/treatment/

- Nuttall, C., & Woods, K. (2013). Effective intervention for school refusal behaviour. Educational Psychology in Practice, 29(4), 347–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2013.846848

- Osborne, C., & Burton, S. (2014). Emotional Literacy Support Assistants’ views on supervision provided by educational psychologists: What EPs can learn from group supervision. Educational Psychology in Practice, 30(2), 139–155. Accessed 11 November 2019. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02667363.2014.899202

- Price, R. (2017). The role of the educational psychologist in children and young people’s mental health: an explorative study in Wales. DEdPsy Thesis, Cardiff University.

- Priory Group. (2018). Eating Disorder Statistics. https://www.priorygroup.com/eating-disorders/eating-disorder-statistics

- Relocate Global. (2019). Guide to International Education & Schools. Kent; Profile Locations.

- Robinson, A. L., Dolhanty, J., & Greenberg, L. (2015). Emotion‐focused family therapy for eating disorders in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1861

- Roffey, S. (2016). Building a case for whole-child, whole-school wellbeing in challenging contexts. Educational & Child Psychology, 33(2), 30–42. Accessed 3 March 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311436427_Building_a_case_for_whole-child_wholeschool_wellbeing_in_challenging_contexts

- Roffey, S., Hobbs, C., & Kitching, A. (2018). Educational psychologists influencing policy and practice: Becoming more visible. Educational & Child Psychology, 35(3), 5–7.

- Roopa, S., & Rani, M. S. (2012). Questionnaire Designing for a Survey. Journal of Indian Orthodontic Society, 46(4_suppl1), 273–277. Accessed 10 March 2020. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.5005/jp-journals-10021-1104

- Sadegholvad, S., Yeatman, H., Parrish, A. M., & Worsley, A. (2017). What Should Be Taught in Secondary Schools’ Nutrition and Food Systems Education? Views from Prominent Food-Related Professionals in Australia. Nutrients, 9(11), 1207. Accessed 4 April 2020. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/9/11/1207#

- Schiele, B. E. (2016). Promoting Progress to Assist Youth with Disordered Eating in School Mental Health. PhD Psychology Thesis, University of South Carolina.

- Scott, C. L., Haycraft, E., & Plateau, C. R. (2019). Teammate influences on the eating attitudes and behaviours of athletes: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 183–194. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2019-38723-022

- Stice, E., Marti, C. N., Spoor, S., Presnell, K., & Shaw, H. (2008). Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 329. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.329

- UK Government. (2014). Children and Families Act 2014. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/pdfs/ukpga_20140006_en.pdf on 19/11/21

- Wagner, P. (2017). Consultation as a Framework for Practice. In: B. Kelly, L. M. Woolfson, & J. Boyle (Eds), Frameworks for Practice in Educational Psychology: A Textbook for Trainees and Practitioners (second ed., pp. 194–216). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Watkins, M. W., Crosby, E. G., & Pearson, J. L. (2001). Role of the school psychologist: Perceptions of school staff. School Psychology International, 22(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2F01430343010221005

- Wilksch, S. M., O’Shea, A., & Wade, T. D. (2018). Media Smart-Targeted: Diagnostic outcomes from a two-country pragmatic online eating disorder risk reduction trial for young adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(3), 270–274.

- Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology & Health, 15(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400302

- Yardley, L. (2008). Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Methods (2nd ed., pp. 235–251). Sage.