ABSTRACT

This study identifies and profiles market mavens among the baby boomer generation in the United Kingdom. Boomers are an important market segment, yet most advertising targets younger audiences, making word-of-mouth communications crucial among this older cohort. Findings suggest boomer mavens place great importance on ‘respect’ values, are particularly concerned with fashion and compared with non-mavens are more likely to try new brands, watch more television, hold positive attitudes towards advertising and seek out bargains. The study is useful to those businesses wishing to target a mature consumer who people perceive as a good source of marketplace information and who likes introducing new brands to others.

Introduction

Since its conception (Feick & Price, Citation1987), a substantial body of knowledge pertaining to market mavenism has developed, resulting in increased understanding of the concept. Market mavens are ‘individuals who have information about many kinds of products, places to shop, and other facets of markets, and initiate discussions with consumers and respond to requests from consumers for market information’ (Feick & Price, Citation1987, p. 85). In other words, market mavens are active purveyors of word-of-mouth communications. The importance of word-of-mouth communications cannot be underestimated. Its ability to influence product and store choice plays an important role in shaping consumer attitudes and behaviours, and is one of the most enduring and widely supported concepts in consumer behaviour (Brown & Reingen, Citation1987; Christiansen & Snepenger, Citation2005). In summarising the literature, Buttle (Citation1998) explains word-of-mouth is more influential than other marketing sources not only for advertising but also those that are perceived as neutral, such as ‘which?’ and other consumer reports. Market mavens are characterised by an extraordinary level of marketplace knowledge and experience and a desire to share this information with others (Feick & Price, Citation1987).

Mavens are powerful diffusers of marketing messages because they are perceived by other consumers as a personal and trusted source of market information (Fitzmaurice, Citation2011) and are therefore able to influence the purchasing decisions of other consumers on a great variety of products (Gnambs & Batinic, Citation2012). Mavens even pass on marketplace information about products they do not buy themselves (Walsh, Gwinner, & Swanson, Citation2004), such is their capacity to sift through masses of marketplace data, news and reports in order to extract information that may be useful to others (Fitzmaurice, Citation2011). These consumers are therefore both information-seekers and -diffusers (Price, Feick, & Higie, Citation1987).

From a socio-demographic profiling perspective, the market maven remains elusive (Sudbury & Jones, Citation2010). However, past research finds that market mavens are individuals who demonstrate relatively high levels of self-esteem (Clark & Goldsmith, Citation2005). They are social beings who enjoy a large number of interactions with other consumers (Higie, Feick, & Price, Citation1987). Mavens are also innovative and demonstrate strong exploratory consumer behaviour and new brand trial (Abratt, Nel, & Nezer, Citation1995; Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). These consumers are smart shoppers in that they hunt out bargains (Boon, Citation2013; Price, Feick, & Guskey, Citation1995); they enjoy shopping (Goldsmith, Flynn, & Goldsmith, Citation2003) and have higher brand recall than non-mavens (Elliott & Warfield, Citation1993).

Market mavens are important because they have knowledge of a wide range of market-related topics and communicate this information to potentially wide-ranging networks of people. In contrast to innovators, early adopters and opinion leaders who spread word-of-mouth communications about specific products, maven’s word-of-mouth incorporates a range of brands (Engelland, Hopkins, & Larson, Citation2001; Slama & Williams, Citation1990) because they have a greater need for variety (Stockburger-Sauer & Hoyer, Citation2009). Moreover, while innovators, early adopters and opinion leaders tend to diffuse product information during the early stages of a product’s life cycle, market mavens diffuse information throughout the life cycle of products (Fitzmaurice, Citation2011). Consumer markets also comprise greater numbers of mavens than either opinion leaders or early adopters (Wiedmann, Walsh, & Mitchell, Citation2001). Mavens disseminate both positive and negative marketplace information (Geissler & Edison, Citation2005), and engage in stronger referral behaviour that achieves a considerably higher conversion rate of new customers than non-mavens. Further, the average order value and cash contributions of new customers acquired through these referrals are higher than the cash contributions of new customers acquired through other sources (Walsh & Elsner, Citation2012). Clearly, the identification and targeting of mavens is crucially important to any firm that wants to stay close to its customers.

Some research classifies market mavenism as a personality trait (Kwak, Jaju, & Larsen, Citation2006; Laroche, Pons, Zgolli, & Kim, Citation2001). Just as extraverts talk more than introverts (Campbell & Rushton, Citation1978), market mavens possess a predisposition to disseminate word-of-mouth to fellow consumers (Wiedmann et al., Citation2001). In other studies mavenism has been classified as a psychographic trait (Martínez & Montaner, Citation2008), suggestive of a wider attitude or lifestyle choice. Other researchers view market mavenism as a role that can be adopted (Feick & Price, Citation1987; Smith & Bristor, Citation1994). Role theory explicates that individuals are members of social positions and each role holds behavioural expectations from both the individual’s and other person’s perspective (Biddle, Citation1986). Hence, the role of the market maven is to gather and transmit information to others as part of an implicit contract. The maven is rewarded by becoming more valuable to those with whom they disseminate information (Smith & Bristor, Citation1994). A further perspective is that market mavenism may be a way of expressing self-concept and identity. It is well established that people use brands and products to communicate their sense of identity (Belk, Citation1988; Twigg, Citation2007), so perhaps in a similar way people use consumption-related information as a way of expressing themselves (Saenger, Thomas, & Johnson, Citation2013). Finally, it is well established that some people take extreme pleasure from shopping as a leisure activity. These people enjoy window shopping and browsing, they have relatively high interest in and involvement with a range of merchandise and they actively pursue evidence of quality and fashion trends (Ohanian & Tashchian, Citation1992). Certainly, there is evidence that some individuals are far more interested and involved in consumer decisions than others (Arnold & Reynolds, Citation2006; Kassarjian, Citation1981). For some people, reasons for shopping extend beyond the provisioning domain, and these individuals reap non-functionalist experiential or social benefits not only from shopping and information searching, but from the dissemination of their findings as well (Collins, Kavanagh, Cronin, & George, Citation2014; Fortin, Citation2000).

What all the preceding perspectives have in common is that they are not dichotomous. Strictly speaking, therefore, when the market maven measurement scale was developed it was designed to measure propensity to provide general shopping and marketplace information (Feick & Price, Citation1987). Consequently, some researchers have questioned the terms ‘mavens’ versus ‘non-mavens’ (Collins et al., Citation2014; Wangenheim, Citation2005). However, just as psychologists refer to people high in propensity for excitability, sociability, talkativeness and assertiveness as ‘extroverts’ (Little, Citation2008), so too can people high in propensity to provide shopping and marketplace information be ‘referred to as market mavens’ (Feick & Price, Citation1987, p. 83; Smith & Bristor, Citation1994).

Originally identified in the United States (Feick & Price, Citation1987), market mavens are now recognised in a variety of countries and cultures (Abratt et al., Citation1995; Chelminski & Coulter, Citation2002; Kwak et al., Citation2006; Martínez & Montaner, Citation2008; Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). However, the United Kingdom lags behind. Of the two previous UK studies, one (Goodey & East, Citation2008) cast doubt on the existence of a British market maven, while the other (Sudbury & Jones, Citation2010) suggested they do exist. Clearly, further investigation is needed to ascertain the usefulness of the concept in the United Kingdom, particularly as cultural differences have emerged in previous studies (Feick & Price, Citation1987; Kontos, Emmons, Puleo, & Viswanath, Citation2011; Pornpitakpan, Citation2004; Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). Moreover, studies comprising a range of segments and markets have resulted in the identification of industrial mavens (Nataraajan & Angur, Citation1997), e-Mavens (Walsh & Mitchell, Citation2010), teen mavens (Belch, Krentler, & Willis-Flurry, Citation2005), man-mavens (Wiedmann et al., Citation2001) and even virtual world mavens (Barnes & Pressey, Citation2012). Yet, no previous attempt has identified and profiled the more mature maven, despite the unprecedented and profound aging of the world’s population that makes middle-aged and older consumers in general, and baby boomers in particular, so important.

Evidence from cognitive psychology and cognitive and affective neuroscience supports the contention that older adults have different information processing strategies than their younger counterparts (Gutchess, Citation2010). Consequently, older consumers have different decision-making processes (Peters, Citation2010; Queen, Hess, Ennis, Dowd & Grühn, Citation2012; Yoon, Cole, & Lee, Citation2009), all of which impacts their attitudes towards possessions (Ekerdt, Citation2009; Folkman Curasi, Price, & Arnould, Citation2010), and brand choice (Lambert-Pandraud & Laurent, Citation2010). Older and younger consumers differ in the way they make product-related decisions (Queen et al., Citation2012; Yoon et al., Citation2009) and age-related differences in advertising processing and effectiveness has been well-documented for decades (Burnett, Citation1991; Cole & Balasubramanian, Citation1993; Johnson & Cobb-Walgren, Citation1994). Clearly, what works when targeting younger people will not necessarily work with older adults. Yet the vast majority of advertising spend still goes on advertising designed for people under 50 years old (Haslam, Citation2015; Lewis, Medvedev, & Seponski, Citation2011; Nielsen, Citation2012). Many practitioners are still struggling to find effective communication strategies to reach mature consumers (Moody & Sood, Citation2010; Moschis & Mathur, Citation2006) leading to alienation (Carrigan & Szmigin, Citation2000; Hurd Clarke, Citation2011; Moschis & Mathur, Citation2006; Twigg & Majima, Citation2014; Walker & Macklin, Citation1992) among a market that is becoming increasingly important for a range of goods and services (Eurostat, Citation2012; Reuters, Citation2013; Sudbury-Riley, Kohlbacher, & Hofmeister, Citation2015). Clearly, this situation makes the identification of market mavens among older segments even more important.

The current study makes three major contributions. First, it identifies and profiles an older market maven which is useful for practitioners who wish to target mature consumers. Second, the study adds to the relative paucity of UK-based maven research and therefore answers calls for more research in additional countries (Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). Finally, the current research contributes to the burgeoning international literature pertaining to mavens. In so doing, the study in part replicates previous work, and at the same time extends knowledge pertaining to mavens by investigating some antecedents that have never before been considered. The paper begins by outlining the importance of baby boomer consumers to businesses. It then reviews the market maven literature and identifies potentially important antecedents, attitudes and behaviours typical to these important consumers, in order to build a model which is then empirically tested using structural equation modelling (SEM). Implications of the study for research and practice are discussed.

Baby boom consumers

Baby boomers (born 1946–1964) comprise 23% of the UK population (ONS, Citation2013). Though deep pockets of poverty exist among boomers (Hayes & Finney, Citation2014), overall this cohort has the highest wealth levels and is amongst the leading spenders on a range of products and services in the United Kingdom (Kingman, Citation2012; Sudbury-Riley, Kohlbacher, & Hofmiester, Citation2012; Zolpho Cooper, Citation2012). Indeed, a recent report conducted by the Centre for Economic and Business Research (CEBR) claimed spending by consumers aged 50 and over helped drag Britain’s economy out of its 5-year malaise (Oxdale, Citation2014). Despite these facts, which should have firms clamouring to serve boomers, there is a body of research to suggest marketers are still ignoring them in favour of their younger counterparts (Giegerich, Citation2012). This neglect is particularly pertinent in advertising: less than 5% of advertising is geared towards people over 50 years old (Nielsen, Citation2012), an assertion that is supported by content analyses of UK advertising (Carrigan & Szmigin, Citation2003; Simcock & Sudbury, Citation2006; Yoon & Powell, Citation2012). Consequently, it can be speculated that word-of-mouth communications may be relatively more important for boomers than for younger age groups who receive the majority of marketing communications messages.

Baby boomers are a unique cohort from a cultural and marketing perspective. In contrast to the generation that preceded them which grew up with the austerity of the post-war years and a tendency to conform (Lifecourse Associates, Citation2012), boomers have experienced a life-course with an emphasis on choice, autonomy, self-expression and pleasure (Jones et al., Citation2008; Whitbourne & Willis, Citation2006). The advertising agencies of Madison Avenue created a youth culture as a reaction to the Depression, and a shift from class differences to age-related lifestyle differences was born. The cultural shift took a little longer in the United Kingdom, but nevertheless it came. By the 1960s, for the first time in history, the focus in British society was on working-class teenagers and this is the period in which the origins of mass consumption are found. Subsequently, ‘socialization into the new lifestyles of consumption has permeated the lives…of the participants of post-war youth culture’ (Jones et al., Citation2008, p. 39). In a nutshell, baby boomers shaped modern marketing (Thompson & Thompson, Citation2009) and there is no reason to believe that just because they have reached a landmark birthday they will cease to be interested in the marketplace. Recent research shows the amount of advice a consumer receives decreases significantly over the age of 54 (East, Uncles, & Lomax, Citation2015), making the identification of market mavens among older segments even more important.

The use of the label ‘baby boomer’ in the United Kingdom needs to be explained, as it is perhaps not quite as distinct as the American baby boom. The United Kingdom had a distinctive pattern of two separate peaks in the birth rate – in 1947 and 1964 (Phillipson, Citation2007) and sociologists have argued that the label baby boomer should be used with a caveat in the United Kingdom, with many referring to this period in life as the ‘third age’ (Laslett, Citation1989). The ‘third age’ is a term used to describe the period before old age, necessary, Laslett (Citation1989) argues, due to the astonishing increases in life-expectancy. The third age is one marked by personal realisation and self-fulfilment that extra years of life have made possible. Twigg (Citation2007) refers to the third age as a social space with its roots in consumer culture. Gilliard and Higgs (Citation2007) argue that Laslett’s (Citation1989) view of the third age confounds individual development, cohort and period. These authors contrast two perspectives: a baby boomer cohort perspective with a generational approach concerned with mass consumer culture, and argue that what differentiates them is the focus on a distinct baby boomer identity as opposed to a focus on generational lifestyle. Important, however, is the assertion that whichever perspective is taken, there is no doubt that the 1960s marked a cultural and economic revolution that witnessed choice, autonomy, self-expression and hedonism (Gilliard & Higgs, Citation2007). This is a generation that view themselves as a bridging generation between the old ways of their own parents and the fundamentally different views of the next generation. Consequently, new subcultures based on different lifestyles and ways of purchasing emerged. Thus, while there is some doubt that in 2015 those people between the age of 50 and 69 years in the United Kingdom necessarily identify with the term baby boomer as a social identity, it is clear that this group of people are particularly favoured and are establishing a new mature market whose communal identity is based upon a consumer-oriented lifestyle (Gilliard & Higgs, Citation2007). The post-war period marked the formation of a particular generational entelechy which has been carried on into the twentieth century with particular consequences for the experience of consumption in later life (Jones, Higgs, & Ekerdt, Citation2009). This group of people also recognise a marked difference in social attitudes as a comparison with the generation that preceded them, and these are expressed in certain consumption choices, notably choices that influence appearance, including clothing (Twigg, Citation2007), bodily maintenance, diet and exercise (Biggs, Phillipson, Leach, & Money, Citation2007). There also appears to be a marked shift in consumption practices from consuming things to consuming experiences (Gilliard & Higgs, Citation2009).

Whatever the label used, there is no doubt that sociologists view baby boomers, or third agers, or ‘the young-old’ (Garfein & Herzog, Citation1995), as a generation that is set apart from other generations due to their distinct experiences. Thus, while sweeping generalisations should be discouraged because different nations experienced the baby boom in different ways, there is little doubt that distinct experiences shared by this group of people across many nations revolve around consumption and lifestyle experiences that were unlike preceding generations (Phillipson, Citation2007). The extent to which different aspects of consumption and lifestyles are related to specific generational groups is an important area for research, particularly in examining the generational habits that developed in tandem with the rise of mass consumption (Jones et al., Citation2009). The UK press frequently use the term baby boomer (Robertson, Citation2015; Sodha, Citation2015; Vallely, Citation2011), and it is used here to refer to the group of people who were born between 1946 and 1964, who were therefore aged 50–69 years in 2015. The baby boomers are an important cohort to study not only because of its size but because of the journey they have taken over their lives (Leach, Phillipson, Biggs, & Money, Citation2013). Yet, many empirical studies of market mavens fail to include anyone over age 50 years in their samples at all (Goldsmith, Flynn, & Clark, Citation2012; Goldsmith et al., Citation2003; Hwan, Leizerovici, & Zhang, Citation2012; Mooradian, Citation1996) or are biased towards younger aged respondents with average sample ages in the twenties (Geissler & Edison, Citation2005; Goldsmith, Clark, & Goldsmith, Citation2006) or thirties (Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). No previous maven study has concentrated solely on consumers over 50 years old. The current study therefore adds knowledge to what is the increasingly important older consumer market.

Market mavenism: potential antecedents

Socio-demographics

Previous research fails to reach consensus on whether market mavenism is negatively related to age (Goldsmith et al., Citation2006; Goodey & East, Citation2008; Williams & Slama, Citation1995), unrelated to age (Barnes & Pressey, Citation2012; Walsh et al., Citation2004) or indeed positively related to age (Kontos et al., Citation2011). Kontos et al.’s (Citation2011) study is very relevant in the current context because it is one of the few pieces of maven research that incorporates a relatively large number of older respondents (71 respondents over 50 years old) and finds that people over 50 years old are among those groups who are particularly reliant on interpersonal sources for information. Generally, however, market maven knowledge emerges from studies of younger adults (Goldsmith et al., Citation2012; Mooradian, Citation1996; Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). Even samples that incorporate relatively wide age ranges tend not to include many respondents over 50 years old. Wiedmann et al. (Citation2001), for example found some analyses were impossible to perform because there were too few subjects in their age 50+ group, thus their assertion that age is not related to market mavenism needs further investigation. Other socio-demographic variables also fail to demonstrate consistent results with regards to mavenism. Some studies find mavens are more likely to be female (Goldsmith et al., Citation2006; Kontos et al., Citation2011; Williams & Slama, Citation1995), and others found a tendency for mavens to be of lower socio-economic groups (Feick & Price, Citation1987). Overall, however, from a socio-demographic profiling perspective the market maven remains elusive (Clark, Goldsmith, & Goldsmith, Citation2008; Walsh et al., Citation2004; Wiedmann et al., Citation2001). There is no theoretical reason why boomer mavens should have a different socio-demographic profile than those belonging to younger cohorts, thus it is suggested that:

H1: The basic socio-demographic profile (age, gender, socio-economic status (SES)) of boomer mavens does not differ from their non-maven counterparts.

Feick and Price (Citation1987) view market mavenism as a role that can be adopted, and discuss the possibility that some people gather information (including marketplace information) to use in future social interactions. For some, this knowledge is important not necessarily because it is directly relevant to their own interests (as would be the case with an opinion leader who is highly involved in a product category) but because ‘they think it will be useful to others or because it will provide a basis for conversations’ (Feick & Price, Citation1987, p. 85). This finding is potentially important for the current study among baby boomers, many of whom experience role loss due to children flying the nest, retirement or even widowhood. Indeed, activity theory suggests that if a person is to age optimally, new roles should be substituted for those that are lost (Passuth & Bengston, Citation1988). At the same time, becoming a grandparent can be a time of rejuvenation (Thompson, Itzin, & Abendstern, Citation1990) and this role can be an important one. However, past maven research has not considered these potentially important life-cycle variables. Thus,

H2: Market mavenism is related to (a) empty-nest status, (b) widowhood, (c) retirement, (d) grandparenthood.

Traits and values

Attempts to understand the personality traits of the market maven using the big-5 (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness) have not been very successful. Mooradian (Citation1996) found extraversion and conscientiousness were significant predictors, but these accounted for only 5% of the variance. Goodey and East (Citation2008) found none of the big-5 to be predictors. In contrast, when traits founded from a synthesis of Jungian and post-Jungian personality types were used, Brancaleone and Gountas (Citation2007) found a significant physical/sensing trait – defined as a person who gets pleasure from physical comforts and material possessions. Clearly, this personality trait is akin to materialism, which is usually classified as a value in the consumer behaviour literature (Bearden & Netemeyer, Citation1999), and has been found to be an antecedent to market mavenism (Goodey & East, Citation2008). Perhaps, then, investigations into values are more worthwhile, especially as values have hierarchical primacy over attitudes (Homer & Kahle, Citation1988) and transcend objects and situations, which attitudes do not (Crosby, Gill, & Lee, Citation1984). Indeed, values can help the understanding of consumer’s motivations and logic of decision-making (Homer & Kahle, Citation1988) and influence a range of consumer behaviours including reactions to products media preferences, advertising, packaging, personal selling and retailing (Batra, Homer, & Kahle, Citation2001). It is surprising that only a small number of maven studies have considered values.

Goodey and East (Citation2008) argue that because mavens are particularly interested in the marketplace, it follows that they are focused on material possessions. This argument was partially supported among the males in their sample. Conversely, consumer theory suggests that the relationship a person has with material items changes over time, and as people age they become less materialistic (Belk, Citation1988; Citation1990; Richins & Dawson, Citation1990) and more interested in experiences than things (Dychtwald & Flower, Citation1989). Indeed, Wolfe (Citation2004) suggests the key values that form the root motivations of consumers over 50 years old include social connectedness and altruism. Consequently it would be useful to consider materialism in relation to a more mature sample, with the expectation that boomer mavens may be less materialistic than their non-maven counterparts. Further evidence to tentatively suggest that mavens may have a different value base than non-mavens comes from only one small-scale study. Sudbury and Jones (Citation2010) found mavens place importance on values such as being responsible, helpful, polite and having warm relationships with others, supporting the contention that mavens are motivated to engage in word-of-mouth communications through a sense of obligation to share information, a desire to help others and feelings of pleasure derived from this helping behaviour (Walsh et al., Citation2004), all of which suggest the market maven has a social, altruistic nature. These traits are in complete contrast to someone who places high importance on material possessions because materialistic people tend to place less emphasis on personal relationships (Richins & Dawson, Citation1992). This enigmatic situation, coupled with the fact that age differences in the importance placed on different values have been identified (Kahle, Poulos, & Sukhdial, Citation1988), provide sound reasons for investigating values in general and materialism in particular in relation to boomer mavens. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3: Mavenism among boomers is (a) positively related to values pertaining to relationships and altruism, and (b) negatively related to material values.

Group factors

Evidence suggests market mavens exert normative influence over others in their social network due to their enhanced social status. This status is derived from being perceived as knowledgeable and willing to share that knowledge with others (Goldsmith et al., Citation2006). However, this does not suggest that market mavens like to stand out from the crowd. Rather, mavens seem to prefer to be distinctive within social boundaries. Hence mavens choose products that distinguish them within their social groups, but ensure these brand choices do not break conventional boundaries of the group. Confirmation of this characteristic comes from findings that while market mavenism is positively related to susceptibility to normative influence and to a consumer need for uniqueness, it is also positively related to a tendency to conform (Clark & Goldsmith, Citation2005; Goldsmith et al., Citation2006). Initially these traits appear to contradict each other, but uniqueness can be used for differentiation and social approval purposes at the same time (Ruvio, Citation2008), and when they are considered from a reference group perspective they make sense. The market maven uses brands, knowledge of market information and marketplace helping behaviour in order to gain status within the group, not to be different from the group (Goldsmith et al., Citation2006).

Of course, a central problem with reference group theory is the identification of an important reference group (Williams, Citation1970). One way to overcome this problem is to use a comparison group (Childers & Rao, Citation1992). Festinger’s (Citation1954) original social comparison theory was based on the premise that comparisons with other people are valuable sources of knowledge about oneself, and, in the absence of any objective standards, individuals compare themselves with others (Gulas & McKeage, Citation2000). The concept of attention to social comparison information (ATSCI) is useful in a consumer behaviour context because sources of social comparison information include the type of brands that are worn and ‘explicit pronouncements of the relative appropriateness of the consumption of certain products or services made by important referents’ (Bearden & Rose, Citation1990, p. 462). Clearly, this description fits the market maven, though to date ATSCI has never been investigated in relation to them. Consequently,

H4: Market mavenism is positively related to attention to social comparison information.

Psychological factors

Social comparison also serves as a basis for self-enhancement, aimed at protecting or enhancing one’s self-esteem (Wood, Citation1989). Substantial research demonstrates that ‘people are not unbiased; they often harbour unrealistically positive views of themselves and bias information in a self-serving manner’ (Wood, Citation1989, p. 232). Indeed, in comparison to non-mavens, market mavens have been shown to demonstrate higher levels of self-efficacy (belief about his or her ability to produce effects) which may of course encourage marketplace helping behaviour insofar as the maven is confident that the help will be effective (Geissler & Edison, Citation2005). Given this enhanced status and self-belief, it is no surprise that research overwhelmingly shows market mavens demonstrate relatively high levels of self-confidence (Chelminski & Coulter, Citation2007). The concept of public self-consciousness is akin to a general measure of self-confidence, and refers to a process of self-focused attention (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, Citation1975). Persons who demonstrate high levels of public self-consciousness are particularly concerned with the kind of public impression they make, as well as being less shy or embarrassed with strangers (Barak, Citation1998). This description appears to fit the market maven, yet to date public self-consciousness has never been considered in maven studies, despite its potential as an important segmentation variable (Burnkrant & Page, Citation1982). Clearly, it is worthy of investigation, and on this basis:

H5: Market mavenism is positively related to public self-consciousness.

Social comparison information is focused on the reactions of others to one’s behaviour. Termed the injunctive norm (Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, Citation1991; Cialdini, Reno, & Kallergren, Citation1990), behaviour is motivated via doing what is expected by other people. In contrast, the personal norm is tied to self-concept and motivates a person to act in a way that is consistent with their own values. Behaviour that is compliant with the personal norm enhances self-esteem (Minton & Rose, Citation1997). Self-esteem is an important motivational drive for a range of consumption behaviours, including acceptance or avoidance of symbolic goods that serve as symbols of either uniqueness or group affiliation (Banister & Hogg, Citation2004). Some research shows mavens demonstrate relatively high levels of self-esteem (Clark & Goldsmith, Citation2005). What is not known, however, is if marketplace helping behaviour is driven more by a concern for what other people think (ATSCI) than the need to behave in a manner consistent with individual values (self-esteem). Clearly, it would be interesting to compare both ATSCI and self-esteem in order to better understand the motivations of market mavens. Hence,

H6: Market mavenism is positively related to self-esteem.

The literature so far suggests that although the market maven is difficult to profile in terms in socio-demographic characteristics, they are a person who is altruistic, perhaps not very materialistic, who values relationships, cares what other people think of them and has high self-esteem. In other words, the issues under deliberation so far pertain to the individual’s demographic, social and psychological make-up. It is also important to contemplate the outcomes of market mavenism, so it is to the literature on attitudes and behaviour of mavens that the discussion now turns.

Market mavens: attitudes and behaviour

New brand trial

While market mavenism and opinion leadership are distinct constructs (Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007) they are positively related (Goldsmith et al., Citation2006). There is no doubt that in contrast to non-mavens, mavens are venturesome in that they demonstrate earlier awareness of new products and brands (Abratt et al., Citation1995), strong exploratory behaviour and new brand trial (Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007) and perceive less risk in their purchases, probably due to increased marketplace comfort (Smith & Bristor, Citation1994). A popular belief that early adopters tend to be young led Rogers (Citation2003) to a thorough review of the innovation literature, from where he confirmed, ‘early adopters are no different from late adopters in age’ (p. 288). In other words, early adopters come in all ages and there are vast differences between groups of baby boomers, with some demonstrating relatively high levels of willingness to try new brands, while others are far less innovative (Sudbury & Simcock, Citation2009). Thus,

H7: Market mavenism is positively related to willingness to try new brands.

Consumer information sources

Maven’s marketplace involvement make them good targets for a range of marketing messages, including those that may not have much inherent consumer interest. In other words, market mavens are highly involved with a range of marketing activities (Feick & Price, Citation1987). Consequently, mavens have better top-of-the-mind awareness of more brands across different product categories indicative of their experimental buying behaviour and general interest in gathering marketplace information (Elliott & Warfield, Citation1993). Mavens are active information-seekers (Smith & Bristor, Citation1994) who gather information by consulting lots of different information sources, as they watch more television, listen to more radio, read a wider variety of newspapers and magazines and pay more attention to direct marketing literature (Abratt et al., Citation1995; Schneider & Rodgers, Citation1993). However, in contrast to a true innovator, the market maven is not a risk-taker (Ruvio & Shoham, Citation2007). While they like new technology (Atkinson, Citation2013; Barnes & Pressey, Citation2012) and acknowledge the relative advantage of online shopping in terms of excitement and the convenience of a delivery service (Pechtl, Citation2003) as well as the ability to hunt for deals (Boon, Citation2013), they are less likely to use or adopt online banking (Lassar, Manolis, & Lassar, Citation2005), more strongly disapprove of the missing touch-and-feel experience and have stronger doubts about data protection (Pechtl, Citation2003). Research also suggests that the market maven scale is not the best predictor of online word-of-mouth communications (Saenger et al., Citation2013). These findings lead to the next hypothesis:

H8: Market mavenism is (a) positively related to media consumption (including television, radio and print) but (b) not related to internet use.

Mavens enjoy shopping more than other adults (Abratt et al., Citation1995) and have more favourable attitudes towards direct mail (Schneider & Rodgers, Citation1993), sales promotions (Price, Feick, & Guskey-Federouch, Citation1988) and advertising (Chelminski & Coulter, Citation2002), suggesting they may hold more positive attitudes towards marketing communications in general, though to date this has never been empirically measured. Clearly, this area of attitudes towards marketing is worthy of further investigation because the true maven, irrespective of age, would be expected to demonstrate more positive attitudes towards marketing communications than their non-maven counterparts. On this basis,

H9: Market mavenism is positively related to favourable attitudes towards marketing and advertising.

Price-consciousness

Research shows that mavens are frugal (Bove, Nagpal, & Dorsett, Citation2009), smart shoppers who are heavy users of coupons and deal websites (Boon, Citation2013; Price et al., Citation1995), indicative of the fact that they are price-sensitive and bargain-hunting (Berne, Múgica, Pedraja, & Rivera, Citation2001; Martínez & Montaner, Citation2006; Urbany, Dickson, & Kalapurakal, Citation1996). Irrespective of their price-consciousness in comparison with younger age groups, boomer mavens would be expected to demonstrate such traits to a greater degree than boomers who are non-mavens. Therefore,

H10: Market mavenism is positively related to price-consciousness.

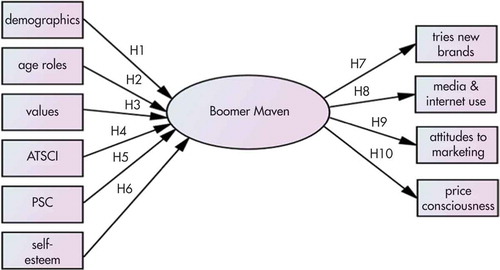

The model to be tested in the study is now complete and can be seen diagrammatically in . Some variables included have been studied widely in the maven literature, though not with individuals over 50 years of age (notably basic socio-demographics, new brand trial, media use and price-consciousness), some have previously been included in one or two general maven studies (values, self-esteem) and others have never before been considered in relation to market mavenism (ATSCI, public self-consciousness (PSC) and overall attitudes towards advertising) and will therefore contribute to the body of existing knowledge pertaining to these important consumers.

Method

Instrument development

A self-administered questionnaire was used in the study. The questionnaire was first pilot tested to colleagues not involved directly with the design of the instrument, a step recommended by Diamantopoulos, Reynolds, and Schlegelmilch (Citation1994) before being piloted to 10 baby boomers, a number considered sufficient for testing such an instrument (Fink, Citation1995). The debriefing method (Webb, Citation2002) was used, hence pilot respondents were told that this was a pre-testing exercise, and in addition to completing the questionnaire they were asked to be critical and note any ambiguities, layout or order issues, or any other improvements they wished to suggest (Fowler, Citation1993). They were also asked to note the length of time taken to complete the questionnaire, which revealed an average of 20 minutes. Personal interviews then took place to debrief respondents, as recommended in the literature (Boyd, Westfell, & Stasch, Citation1989; De Maio & Ladreth, Citation2004; Peterson, Citation1988).

Measures

Whenever possible, well-established multi-item scales with clear conceptual definitions and available evidence of reliability and validity were used. The individual items that these scaled comprise are reported in Appendix 1. No changes were made to the wording of the original Market Maven Scale (Feick & Price, Citation1987). An overall score was computed for all respondents, with a higher score indicating a greater propensity to provide marketplace knowledge.

Socio-demographic variables (as in H1) included age, gender and socio-economic group. Age-related roles (H2) included empty/full nest, grandparenthood, widowhood and retirement status. Empty nest and grandparenthood have never before been incorporated into a maven study, but have been found to be important drivers in the consumer behaviour of baby boomers (Schewe & Balazs, Citation1992), probably due to the significance of these roles during later life.

Values (H3a) were measured using Kahle’s (Citation1983) list of values (LOV), defined as enduring beliefs that individuals hold about specific modes of conduct or end states (Batra et al., Citation2001), and developed from a theoretical base most closely tied to social adaptation theory, and relate to the major roles in life (Kahle, Citation1983). The materialism value (H3b) comprised Richins and Dawson’s (Citation1992) Materialism scale. These authors conceptualise materialism as ‘a value that guides people’s choices and conduct in a variety of situations, including, but not limited to, consumption arenas’ (p. 307).

Social comparison (H4) was measured using the ATSCI scale (Lennox & Wolfe, Citation1984). Lennox and Wolfe explain the construct as the extent to which one is aware of the reactions of others to one’s behaviour and is concerned about or sensitive to the nature of those reactions. These individuals care what other people think about them and look for clues as to the nature of others’ reactions towards them.

Public self-consciousness (H5) was assessed using the public self-conscious scale (Fenigstein et al., Citation1975) which defines the construct as ‘a general awareness of the self as a social object’ (p. 523).

Self-esteem (H6) was measured with the self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, Citation1965, Citation1979); this conceptualises self-esteem as self-worth, a feeling of self-acceptance.

In terms of expected behaviour, the new brand tryer (H7) scale (Wells & Tigert, Citation1971) was chosen on the basis that it measures venturesome consumers in terms of curiosity with new brands, innovation and a liking for novelty.

Media usage (H8) was ascertained with a series of questions to determine the amount of television, newspaper, radio, magazine and internet usage.

Attitudes to marketing and advertising (H9) were assessed using two of the sub-scales of the ‘consumer attitudes toward marketing and consumerism’ instrument (Barksdale & Darden, Citation1972). The first sub-scale pertains to the philosophy of marketing (e.g. ‘most manufacturers operate on the philosophy that the consumer is always right’ and ‘manufacturers seldom shirk their responsibility to the consumer’), while the second relates to advertising and comprises statements such as ‘manufacturers’ advertisements are reliable sources of information about the quality and performance of products’.

Finally, price-consciousness (H10) was measured using the price-conscious scale (Wells, Citation1975), which comprises items such as ‘I shop a lot for special offers’ and ‘I usually watch out for announcements of sales’.

Sample

After gaining ethical approval from the university, a national (encompassing people from all parts of the United Kingdom) mailing list comprising 2500 randomly selected names and addresses of consumers born between 1946 and 1964 was purchased from a commercial market research agency. The list was delivered in the form of pre-printed labels each with the name and address of a person born between 1946 and 1964. Hence, the only exclusion criterion was people born outside this period. The four-page questionnaire and pre-paid reply envelope were mailed to each person, along with a cover letter that explained the study was academic and not for commercial purposes, requested that only the person whose name appeared on the envelope should complete the questionnaire, and guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. There was also a slip for respondents to include a telephone number if they wished to enter a sweepstake with prizes of shopping vouchers for a major high-street store. Two prizes of £200 each were offered, and the director of faculty oversaw the prize draw, with two names being drawn at random. A total of 442 questionnaires were returned; of these 4 were unusable. A description of the demographic make-up of the final sample (n = 438) is shown in . The mean age of the sample is 58.5 years (SD 5.76 years).

Table 1. Sample profile (n = 438).

Analysis and results

Preliminary analysis

The market maven scale demonstrated high levels of reliability (α = 0.89). The reliability of the remaining scales were checked and also found to be acceptable (material values, α = 0.82; attention to social comparison, α = 0.81; public self-consciousness, α = 0.81; self-esteem, α = 0.84; new brand tryer, α = 0.79; attitudes towards marketing and consumerism, α = 0.72; price-consciousness, α = 0.78).

Basic socio-demographics (H1)

Analysis provided mixed support for H1. Market mavenism is unrelated to age. However, in comparison to males (M = 16.0, SD = 5.39), females score significantly higher (M = 18.10, SD = 5.1) on the market maven scale (t = −3.957, df = 429, p < .001). Further, a one-way ANOVA reveals significant differences between socio-economic groups (F(3, 409) = 14.370, p < .001) and post hoc tests demonstrate that boomers in the highest SES group are less likely to be market mavens than those in the lower SES groups.

Age roles (H2)

Market mavens are significantly more likely to be found among those with empty nests (M = 18.03, SD = 5.15) in comparison to full nests (M = 16.78, SD = 5.16, t = −2.289, df = 382, p < .05). However, while widows score higher on the maven scale than any other marital status, these differences did not reach statistical significance. Likewise, retirees do not display different maven tendencies to workers or homemakers. Finally, grandparents show significantly greater maven tendencies (M = 18.0, SD = 51.16) than those without grandchildren (M = 16.5, SD = 5.22, t = 2.790, df = 351, p < .01).

Structural equation model

The remaining hypotheses were tested with structural equation modelling (SEM) using AMOS, version 20. Prior to testing the SEM, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to test the measurement model in order to examine the extent (or lack) of interrelationships among the latent constructs and indeed derive the best indicators for the latent variables. It is better to have highly correlated indicators as these are most likely to yield unbiased and efficient representations of constructs and their interrelations (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, Citation2002). Thus, through screening the correlation matrices for items that clustered together (and discarding items that had near-zero or negative correlations with other measures of the same construct) and examining the reliability of each item by ensuring the squared correlation between the item and the latent variables was greater than .5, indicator variables for each latent variable were chosen. Because SEM explicitly takes into account measurement error and hence reliability, it is permissible to have some latent constructs comprise as few as two items (Xie, Bagozzi, & Østli, Citation2012), though Schumacker and Lomax (Citation2004) advise at least three. Thus, as many indicator variables as possible were retained on the basis that using more rather than fewer indicator variables was deemed to be a more efficient representation of the latent constructs (Little et al., Citation2002). Less than 1.5% of cases contained missing data so it was considered safe to delete these cases (Roth, Citation1994).

Prior to developing the structural model, a measurement model was built in order to ensure the measurement of each latent variable was psychometrically sound (Byrne, Citation2010), and the analysis moved from confirmatory to exploratory when several indicator variables were removed on the basis of their low loadings or instances of the Heywood effect. The final measurement model was assessed using a variety of fit indices (comparative fit index, Tucker-Lewis index and incremental fit index) shown in .

Table 2. Final measurement and path model fit.

Though the χ2 value is significant (χ2 = 900.923, df = 558, p < .000), the RMSEA value of .038 is well within the guidelines for a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993). Likewise, the range of fit indices shown in all fall within recommended values (Byrne, Citation2010).

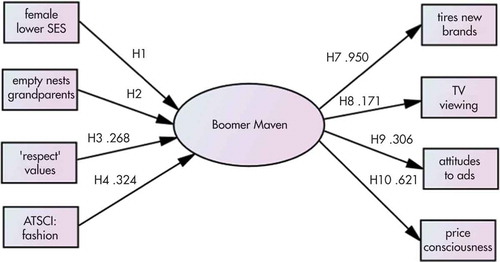

The final structural model, which, as shows, is also a well-fitting model, revealed some structural paths to be non-significant, and these were duly removed. details the standardised estimates for the structural paths.

Table 3. Standardised parameter estimates for structural paths.

Table 4. Mean scores, average variances extracted (AVE) and construct reliability (CR).

Additionally, presents the mean scores, the average variance extracted (AVE) and the construct reliability (CR) results. All AVEs exceed the cut-off of .5 (Ping, Citation2004) indicating convergent validity and all CRs exceed .7 indicating good reliability (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988).

In relation to H3a, only two of the eight LOVs were found to significantly impact market mavenism. The values that remained in the final model are LOV 4 and LOV 7, which are ‘being well-respected’ and ‘self-respect’. Materialism (H3b) was not significant and was deleted from the final model. A CFA conducted on ATSCI (H4) revealed the scale to comprise two distinct factors. The first relates to the tendency to look to other people for cues of how to behave (e.g. ‘when I am uncertain how to act in a social situation, I look to the behaviour of others for clues’ and ‘it’s important to me to fit into the group I’m with’), while the second pertains to fashion and clothing (e.g. ‘I tend to pay attention to what others are wearing’ and ‘I keep up with clothing styles’. Both factors were used in the measurement model, and only one – the fashion factor – remained significant in the final model. Contrary to expectations, market mavenism is not related to public self-consciousness (H5) or self-esteem (H6).

Of course, for these findings to be useful there needs to be an indication that boomer mavens behave differently to their non-maven counterparts. In support of H7, boomer mavens are found to be venturesome. This means that these boomer mavens are more interested in new brands and are more likely to purchase them just to see what they are like, are more innovative in that they try new brands before their friends and neighbours do and they like novelty in that they like to try new and different things. In terms of media use (H8), mavenism among boomers is found to be positively related to television viewing but no significant paths emerged with other media (radio, newspapers and magazines) or with internet use. In terms of attitudes towards marketing and consumerism, no direct path remained between mavenism and marketing attitudes, but a significant path did remain between mavenism and the second factor, thus there is support for H9 in that boomer mavens hold favourable attitudes towards advertising. Finally, full support was found for H10 in that boomer market mavens shop for special offers, hunt for bargains, check the prices in supermarkets and watch for announcements of sales. This relationship still emerged in a follow-up analysis when the effects of SES were controlled (r = .40, n = 538, p < .001).

In sum, results suggest that boomer market mavens are more likely to be female with empty nests. They are more likely to be grandparents and found in all but the highest socio-economic group. They are motivated to give consumer knowledge to others because they need to feel well-respected within the group, and because it gives them a sense of self-respect. These mavens care about clothes and fashion: they pay attention to what others are wearing and they like to keep up with clothing styles. They behave differently to other boomers in the marketplace in that they are significantly more likely to try new brands, hold more positive attitudes towards advertising, watch more TV and are more price-conscious and bargain-seeking. Even when income is taken into consideration, the need to bargain-hunt remains, suggesting this trait is due to their maven tendencies and not due to the need to save money. The final model is shown in .

Discussion

Analysis of the socio-demographic and age-related roles (H1 and H2) provide a profile of a female baby boomer market maven drawn from all socio-economic groups with the exception of the highest, who already has an empty nest, and is a grandparent. At first glance, this could be a description of a much older person, but despite this profile boomer mavens are no older than their non-maven counterparts. Nor are they more likely to be widowed or retired – thus it seems as though it is those boomers who had children and then grandchildren relatively young who are more likely to be market mavens. Much of this socio-demographic profile is of no surprise, given that some prior research finds market maven tendencies among females with lower education status (Feick & Price, Citation1987), suggesting that boomer mavens do not differ from market mavens of other ages in their socio-demographic make-up. Progeny has never before been considered in relation to market mavenism, and these results suggest that family make-up and decision-making processes among mavens is clearly worthy of further investigation.

The expectation that mavens would place importance on values pertaining to relationships and altruism (H3a) was tentative due to the paucity of previous mavenism research that considers values. Neither of these values emerged as important. Interestingly, recent research (Berger, Citation2014) suggests that motivation to engage in word-of-mouth communications is self-serving rather than other-serving. Certainly, the results found here lend support to these findings. That the only values to emerge as important are the ‘respect’ values of ‘being well-respected’ and ‘self-respect’ is therefore a significant finding and suggests that the boomer maven is motivated by a need to belong to a group in which they are well-respected, and this respect is apparently more important than are close relations with people in that group. Recently, it has been established that the ways in which a maven perceives him or herself within their network is of crucial importance to their psychological well-being (Hwan et al., Citation2012). Perhaps by sharing consumer knowledge of brands, products and places to shop they attain that sense of respect. While this finding is novel, it does support earlier research that suggests mavenism is positively related to self-efficacy which is the belief a person has in his/her capacity to produce effects (Geissler & Edison, Citation2005). In other words, market mavens feel that they can make a difference. Taken together, these results suggest that boomer mavens engage in marketplace helping behaviour not solely out of a sense of altruism and concern for others but also for social interaction reasons, particularly to increase their self-perceptions of being well-respected within their social networks.

The finding that there is no relationship between mavenism and material values (H3b) is an interesting one and is also worthy of further investigation. One previous study (Goodey & East, Citation2008) suggests mavens are materialistic, while gerontology and other consumer behaviour literature suggests as people age they become less materialistic (Belk, Citation1988, Citation1990; Richins & Dawson, Citation1990). The possibility therefore remains that while younger mavens may be highly materialistic, as they age this value reduces in importance as they become more interested in experiences than things. Certainly, a maven study to include materialism comparisons between age groups would be an interesting one, particularly as materialism has been shown to be a significant predictor of a range of important variables, including the amount of time spent shopping and spending (Fitzmaurice & Comegys, Citation2006).

ATSCI (H4) has never before been considered in relation to market mavenism. These results are therefore important for several reasons. First, recall that a CFA conducted on the ATSCI scale revealed two distinct factors: one pertaining to the use of social comparisons in order to guide behaviour, and one pertaining to fashion and clothing. That market mavenism is not related to the ‘behaviour guiding’ factor suggests that boomer mavens are confident individuals who are sufficiently self-assured to not need to look to other people for guidance on how to behave. Indeed, that mavenism is also unrelated to public self-consciousness (H5), added to the emphasis placed on ‘respect values’, reinforces the suggestion that boomer mavens are confident individuals. A person who pays attention to social comparison information and who is high in public self-consciousness would certainly need to look to others for guidance and approval of others. The boomer maven, on the other hand, appears to be sufficiently self-assured and hence does not require guidance from others in order to know how to behave in social situations. At the same time, they are no higher in self-esteem (H6) than other boomers, which makes sense given that it is now recognised that social comparison serves as a basis for self-enhancement, aimed at protecting or enhancing one’s self esteem (Wood, Citation1989). Clearly, these mavens achieve a sense of self-respect from sources other than comparisons with other people. The fact that boomer mavenism is however related to the clothing and fashion factor of ATSCI is an important finding. This factor reveals that boomer mavens actively avoid wearing clothes that are not in style, they pay attention to what others are wearing and they keep up with clothing style changes. As Twigg and Majima (Citation2014) point out when discussing baby boomers, clothing provides a fruitful area in which to explore the interface between identity and its expression, as well as the social meanings attached to it. These authors go on to suggest that for some baby boomers, consumption offers the chance of counteracting the cultural exclusion traditionally associated with age (p. 24). Certainly, the results here suggest that involvement in fashion is used by these middle-aged mavens as way of gaining status within the group.

In support of H7, boomer mavens are venturesome. This venturesome trait incorporates items pertaining to curiosity with new brands, innovation and preference for novelty. This means that in comparison to non-mavens, these boomers are more interested in new brands, more likely to purchase a new brand just to see what it is like, more innovative in that they try new brands before their friends and neighbours do and they like novelty in that they like to try new and different things. This of course means that the boomer maven is not likely to demonstrate high levels of loyalty which of course needs to be offset against the fact that they will provide marketplace information that is valued and perceived as credible to other consumers.

Adults aged 55+ years watch more TV than any other age group (Nielsen, Citation2014). The finding that mavens watch even more than the average boomer is therefore an important one that gives practical implications as to how best to reach these crucial consumers. There was full support for H8b, as no significant path emerged between market mavenism and internet use. This finding is also important, in that boomer mavens are just as likely to use the internet as are their non-maven counterparts, but despite their involvement in shopping, brands and the marketplace in general they seem to prefer the real world over online shopping opportunities. This finding supports previous research into younger mavens, where it has been discovered that they are significantly less likely to use or adopt online banking (Lassar et al., Citation2005), and though they acknowledge the benefits of online shopping in terms of convenience and delivery, they more strongly miss the touch-and-feel advantages of the physical shopping experience. Additionally, previous research has found that mavens have a recreational orientation to shopping (Walsh & Mitchell, Citation2002) and there is no reason to suppose these boomers are any different.

It is now recognised that advertising and word-of-mouth are interrelated and complementary (Graham & Havlena, Citation2007; Keller & Fay, Citation2009; Vázquez-Casielles, Suárez-Álvarez, & Del Río-Lanza, Citation2013). The finding that boomer mavens hold more favourable attitudes towards advertising than their non-maven counterparts (H9) is a novel one. It seems that these mavens find most advertising believable and to feel it paints a true picture of products. These mavens find advertisements to be reliable sources of information about the quality and performance of products. This does not imply boomer mavens are susceptible consumers. Indeed, earlier research has shown that mavens understand marketing gimmicks (Feick & Price, Citation1987), while more recently it is being recognised that in comparison to younger consumers middle-aged and older consumers have different decision-making styles that appear to reflect their most valued attributes in making product choices. In other words, older adults may benefit from accrued knowledge experience (Queen et al., Citation2012). Overall, this finding suggests boomer mavens interpret and understand advertising and extract valuable consumer knowledge from it.

Finally, boomer mavens are price conscious bargain-hunters (H10), supporting earlier empirical evidence conducted with younger mavens (Goodey & East, Citation2008; Martínez & Montaner, Citation2006). Recent research suggests that the desire to find the best available product is more important to the market maven than is the need to gain social status (Fitzmaurice, Citation2011). Certainly this smart shopping behaviour is irrespective of their disposable income. Many firms have attempted to move away from a reliance on price-based sales promotions and move instead towards everyday low pricing. However, Garetson and Burton (Citation2003) note that some consumers have reacted negatively to this strategy, suggesting that there is a group of consumers whose primary motivation is not to save money; rather, it is the sense of achievement they get by purchasing products on special offer that motivates them to bargain-hunt. Certainly, these results lend support to this earlier research.

Limitations and implications for future research

This research is not without its limitations. Focusing solely on baby boomers means no age-related differences can be identified or contrasted. Projections suggest that by 2050 life expectancy will reach 85 years in the United Kingdom (United Nations, Citation2015), hence future research should aim to include the generation that preceded boomers, as well as those that followed. If market mavenism is indeed a role that people adopt, then it is possible that role expectations may change over time. Longitudinal as well as cross-sectional research could begin to uncover any such age-related differences in role expectations and enactment. Second, while the current study adds knowledge to the small amount already known about UK mavens, the model needs to be tested using a variety of cultures and nations, particularly as past research has found market mavenism to be impacted by cultural issues (Kontos et al., Citation2011; Pornpitakpan, Citation2004). Third, the current study does not provide any clues as to the nature of the networks through which boomer mavens disseminate marketing information. Future research could attempt to identify whether these networks comprise close ties such as family and friends or weak ties such as work colleagues or acquaintances (Goldenberg, Libai, & Muller, Citation2001). Early research (Granovetter, Citation1973) suggests that weak ties are most important because they have the ability to pass information across clusters or networks, which is important for wide dissemination. Fourth, the research does not give any insight into the online behaviour or television-viewing habits of boomer mavens. Results show that these boomer mavens do not use the internet more than their non-maven counterparts, but it is possible that when they do go online they are spreading word-of-mouth communications that is deemed credible by others. Consumers aged 55–64 years do use the internet but show a marked inclination to make purchases instore (UTalkMarketing.com, Citation2010). The current study clearly reveals that boomer mavens watch relatively high levels of TV. Likewise, uncovering the actual types of preferred television programmes and peak viewing times were beyond the scope of the current study, and research into boomer maven’s television viewing habits would provide practitioners with useful information in order to better target these important consumers. Furthermore, boomer mavens have relatively positive attitudes towards advertising. Recently age-related differences in advertising appeals have been identified (Van Der Goot, Van Reijmersdal, & Kleemans, Citation2016; Wei, Donthu, & Bernhardt, Citation2013), thus future work needs to ascertain the types of advertisements that are likely to resonate with market mavens in this cohort. Finally, while this research has uncovered a group who enjoy shopping, their preferred retail outlets remain unknown. Difficulties experienced in retail outlets increases with age (Atkinson & Hayes, Citation2010), while older consumers have been found to enjoy farmers’ markets (Szmigin, Maddock, & Carrigan, Citation2003). Thrift shopping (shopping for second-hand goods) often attracts people simply for the ‘thrill of the hunt’ (Bardhi, Citation2003) and goes beyond economic factors. The precise shopping habits of these boomer mavens remain unknown.

Conclusion

Despite a wealth of information pertaining to the spending power of baby boomers, marketers and advertisers have been slow to target this potentially lucrative segment. This means that word-of-mouth communications are likely to be even more important among mature adults than among younger audiences. Indeed, market mavens can compensate for a lack of market information and contribute to the welfare of others (O’Sullivan, Citation2015; Price et al., Citation1995). Moreover, researchers usually favour younger samples, yet as people age they become more dissimilar with respect to lifestyles, needs and consumption habits (Moschis, Citation1996), so findings that are relevant to younger adults are not necessarily applicable to middle-aged and older consumers. On this basis, the current study makes an important contribution to knowledge pertaining to baby boomer consumers. Results suggest that boomer mavens are more likely to be female, come from all except the highest socio-economic group and tend to be grandparents with empty nests. Despite this profile boomer mavens are no older than non-maven baby boomers. They place great emphasis on being well-respected and on self-respect, and pay a lot of attention to fashion and clothing. Certainly, the fashion factor to materialise from the ATSCI construct was unexpected at the start of this study. For it to emerge so strongly as an important issue is one that appears to be ripe for further research, especially because some baby boomers are using clothing to resist or redefine the meanings of ageing and the third age, and is therefore an important issue in the role of consumer culture (Twigg, Citation2007, Citation2009). These mavens love trying new brands and introducing new brands to their friends and family, they watch more TV than others in their cohort and they have very positive attitudes towards advertising and use advertisements to gain product information. Relatively recently a focus on ways to successfully target mature consumers through advertising has resurfaced (Sudbury-Riley & Edgar, Citation2013; Van Der Goot et al., Citation2016; Wei et al., Citation2013), and the results here suggest such studies are of utmost importance, given the emphasis boomer mavens place on advertising as a crucial source of information for them to diffuse. Finally, they love to seek out bargains and sales. This bargain-hunting tendency is irrespective of spending power, thus they hold consumer knowledge of pricing and sales and are willing to share that information with other consumers.

Additionally, this research makes a contribution to the market maven literature. It strengthens understanding of the social and psychological profile of market mavens, not least in the use of variables that have been relatively or even completely neglected. Consideration of values as important motivations for these important consumers appears to be a particularly fruitful area of research. The inclusion of ATSCI, never before considered in market maven studies, makes a novel and important contribution. Perhaps even more importantly is the contribution to knowledge pertaining to market mavens in the United Kingdom, which lags far behind what is known in many other countries.

From a managerial perspective, boomer mavens can be targeted with television advertising that positions brands as new and exciting with reasonable prices. The advertising execution strategy should be one where a middle-aged consumer is portrayed as having respect in a social setting. Boomer mavens are willing to try new brands and are interested in advertising to glean consumer information pertaining to many aspects of the marketplace. They are therefore an ideal target for a range of products as well as information pertaining to price reductions and sales. They are also particularly concerned with fashion and clothing, thus are prime targets to disseminate information about clothes shopping and sales. The potential value of these important consumers in terms of their ability to help drive the adoption and diffusion of both new and existing products and brand cannot be underestimated. Indeed, changes in consumption patterns can often be driven by a small group of knowledgeable consumers (Brancaleone & Gountas, Citation2007).

In conclusion, this research adds to the existing body of knowledge pertaining to those important consumers known as market mavens. Its greatest contribution, however, is towards an understanding of the disseminators of marketing information among baby boomer consumers and as such makes a small but significant advancement to current understanding of this large and increasingly important but relatively neglected segment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lynn Sudbury-Riley

Dr Lynn Sudbury-Riley is a lecturer in marketing with experience of teaching a range of marketing courses to undergraduate and postgraduate students. Lynn has won several international awards for her research and has successfully completed a number of consultancy projects with SMEs and mainstream brands in the both the public and private sector. Lynn has gained increasing recognition for her core research which focuses on the consumer behaviour of older adults and her publications appear in many international journals including the Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Business Research, International Marketing Review, Psychology & Marketing, Journal of Marketing Intelligence & Planning, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Journal of Consumer Marketing, International Journal of Advertising and Journal of Consumer Behaviour.

References

- Abratt, R., Nel, D., & Nezer, C. (1995). Role of the market maven in retailing: A general marketplace influencer. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10(1), 31–55. doi:10.1007/BF02249268

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Arnold, M. J., & Reynolds, K. E. (2006). Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 79, 77–95. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(03)00007-1

- Atkinson, A., & Hayes, D. (2010). Consumption Patterns among older consumers. Retrieved from: http://www.ilcuk.org.uk/index.php/publications/publication_details/consumption_patterns_among_older_consumers_-_statistical_analysis

- Atkinson, L. (2013). Smart shoppers? Using QR codes and ‘green’ smartphone apps to mobilize sustainable consumption in the retail environment. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 387–393. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12025

- Banister, E. N., & Hogg, M. K. (2004). Negative symbolic consumption and consumers’ drive for self-esteem: The case of the fashion industry. European Journal of Marketing, 38, 850–868. doi:10.1108/03090560410539285

- Barak, B. (1998). Inner-ages of middle-aged prime-lifers. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 46(3), 189–228. doi:10.2190/Q9X5-8R56-EU39-BEND

- Bardhi, F. (2003). Thrill of the Hunt: Thrift Shopping for Pleasure. Advances in Consumer Research, 30, 375–376.

- Barksdale, H. C., & Darden, W. R. (1972). Consumer attitudes toward marketing and consumerism. Journal of Marketing, 36, 28–35. doi:10.2307/1250423

- Barnes, S. J., & Pressey, A. D. (2012). In search of the “Meta-Maven”: An examination of market maven behavior across real-life, web, and virtual world marketing channels. Psychology & Marketing, 29, 167–185. doi:10.1002/mar.20513

- Batra, R., Homer, P., & Kahle, L. (2001). Values, susceptibility to normative influence, and attribute importance weights: A nomological analysis. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11, 115–128. doi:10.1207/S15327663JCP1102_04

- Bearden, W. O., & Netemeyer, R. G. (1999). Handbook of marketing scales (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- Bearden, W. O., & Rose, R. R. (1990). Attention to social comparison information: An individual difference factor affecting consumer conformity. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(4), 461–471. doi:10.1086/209231

- Belch, M. A., Krentler, K. A., & Willis-Flurry, L. A. (2005). Teen internet mavens: Influence in family decision making. Journal of Business Research, 58, 569–575. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.08.005

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 139–168. doi:10.1086/209154

- Belk, R. W. (1990). The role of possessions in constructing and maintaining a sense of past. Advances in Consumer Research, 17, 669–676.

- Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24, 586–607. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.002

- Berne, C., Múgica, J. M., Pedraja, M., & Rivera, P. (2001). Factors involved in price information-seeking behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8, 71–84. doi:10.1016/S0969-6989(99)00027-2

- Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 67–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435

- Biggs, S., Phillipson, C., Leach, R., & Money, A.-M. (2007). The mature imagination and consumption strategies: Age & generation in the development of a United Kingdom baby boomer identity. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 2(2), 31–59. doi:10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.072231

- Boon, E. (2013). A qualitative study of consumer-generated videos about daily deal web sites. Psychology & Marketing, 30, 843–849. doi:10.1002/mar.20649

- Bove, L. L., Nagpal, A., & Dorsett, A. D. S. (2009). Exploring the determinants of the frugal shopper. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 16, 291–297. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2009.02.004

- Boyd, H. W., Westfell, R., & Stasch, S. (1989). Marketing Research: Text and Cases. Boston, MA: Irwin.

- Brancaleone, V., & Gountas, J. (2007). Personality characteristics of market mavens. Advances in Consumer Research, 34, 522–527.

- Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 350–362. doi:10.1086/jcr.1987.14.issue-3

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Burnett, J. B. (1991). Examining the media habits of the affluent elderly. Journal of Advertising Research, 31(5), 33–41.

- Burnkrant, R. E., & Page, T. J. (1982). On the management of self-image in social situations: The role of public self-consciousness. Advances in Consumer Research, 9, 452–455.

- Buttle, F. A. (1998). Word of mouth: Understanding and managing referral marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 6(3), 241–254. doi:10.1080/096525498346658

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Campbell, A., & Rushton, J. P. (1978). Bodily communication and personality. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17, 31–36. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1978.tb00893.x

- Carrigan, M., & Szmigin, I. (2000). Advertising and older consumers: Image and ageism. Business Ethics: A European Review, 9(1), 42–50. doi:10.1111/1467-8608.00168

- Carrigan, M., & Szmigin, I. (2003). Regulating ageism in UK advertising: An industry perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21(4), 198–204. doi:10.1108/02634500310480086

- Chelminski, P., & Coulter, R. (2002). Examining Polish market Mavens and their attitudes toward advertising. Journal of East-West Business, 8(1), 77–90. doi:10.1300/J097v08n01_05

- Chelminski, P., & Coulter, R. A. (2007). On market mavens and consumer self-confidence: A cross cultural study. Psychology & Marketing, 24(1), 69–91. doi:10.1002/mar.20153

- Childers, T. L., & Rao, A. R. (1992). The influence of familial and peer-based reference groups on consumer decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 198–211. doi:10.1086/jcr.1992.19.issue-2

- Christiansen, T., & Snepenger, D. J. (2005). Information sources for thrift shopping: Is there a “thrift maven”? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(6), 323–331. doi:10.1108/07363760510623911

- Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 201–234.