ABSTRACT

This paper presents collage-making as an art-based research method that can be engaged throughout the research process in order to enhance a reflexive consumer research practice. We argue that such an approach is specifically useful for researching contested spaces, as collage can help navigate the ‘messiness’ of such research. To illustrate how collage can support a critically engaged academic practice, we present an on-going collaboration between the authors that explores consumer culture in a conflict setting. We show that when taken on as a comprehensive, reflexive approach to consumer research, collage-making facilitates an exploration of research contexts in a more affective, interactive, contextualised, and embodied manner. In this way, collage allows to communicate research contexts as they are lived and experienced, rather than through the lens of pre-existing structures of research.

Introduction

Consumer research that focuses on issues of social justice often takes place in contested spaces, which are contexts marked by messiness. More than a state of disorderliness, messiness is a cultural classification. In her seminal work on symbolic pollution, Douglas (Citation1967) defines tidiness and (untidiness) as ‘classification and the dangerous transgression in classification’ (quoted in: Dion et al., Citation2014, p. 566). While tidiness promotes dominant ways of knowing, messiness challenges the status quo by symbolically polluting accepted norms and meanings (Dion et al., Citation2014). Messiness is thus political, shining a light on the possibility of a different future and opening up the potential for new directions (Avner et al., Citation2014). Arguably, most research takes place in somewhat messy contexts. However, contested spaces present an especially complex set-up for messiness, as they often come with potential volatilities as well as elaborate and problematic ideological dimensions (Micheletti & Oral, Citation2018).

The way researchers engage with and communicate the messiness of research contexts often tidies up and thus obscures the multiplicity of meanings that it entails. A ‘sanitised approach’ to research communication overlooks the messiness of the research process itself, which tends to involve multiple entanglements. By this we refer not only to the contexts in which we do our work, but also, for instance, to the theories that inform our work and the forms of interaction we take on with our research participants. Research that ‘sanitises’ messy contexts often engages with the politics and ideologies of these settings through narrowly defined structures of academic work. In this way, hegemonic discourses and practices are perpetuated in the process of communicating research (Merilӓinen et al., Citation2008).

Traditional formats for conducting and presenting research cannot always convey the complexity of messiness within research contexts and processes, as messiness is not easily approached or expressed through linear, language-based structures (following Seregina, Citation2020; Scotti & Aicher, Citation2016; Wood, Citation2015). Art-based research (ABR) methods are one way to approach research differently, as they allow researchers to engage interactive, reflexive, and co-creative tools for building knowledge and engaging research contexts. Specifically, we propose collage as an ABR tool for helping researchers navigate the messiness of doing and presenting research.

Alternative research methods that make use of artistic processes have emerged in consumer research as a response to traditional research approaches reducing meaning to scientific language and thus failing to fully engage emotional, subjective, and political experiences (Sherry & Schouten, Citation2002; Wood, Citation2015). In order to tap into co-created, affective, diffused meanings in their work, as well as to push the boundaries of doing and sharing research, consumer researchers have taken on poetry (e.g. Canniford, Citation2012; Downey, Citation2016), prose (e.g. Brown, Citation2011; Schouten, Citation2014), video (e.g. Belk et al., Citation2005; Hietanen et al., Citation2014), as well as various performance- and visuals-based approaches (e.g. Modrak, Citation2015; Ozanne et al., Citation2013).

Following Seregina (Citation2020), consumer researchers often use alternative research methods to supplement traditional methods for data collection. (Notable, but rare exceptions, where the creative output in itself is the focus of research, include, for example, the Consumer Culture Theory Conference Poetry books and the Marketing Theory special issue ‘Expressions of Interest’.) In contrast, we engage collage as a reflexive tool throughout the research process in order to understand how it can support researchers working in contested spaces. We highlight how collage as a comprehensive artistic process can help at all stages of the research process (e.g. theorising, data collection, analysing), and, most importantly, can support researchers in engaging and communicating messy contexts.

The overall aim of this paper is to explore and present the use of collage-making as a comprehensive, reflexive approach to consumer research, specifically when working within contested spaces. We further contribute towards methodological advances in scholarship that can account for and communicate the complex and sensitive nature of social justice research (Hutton & Heath, Citation2020), including the conceptual communication of its ‘messiness’. This, we hope, will enable researchers to become aware of the multiple entanglements in relation to their research contexts and processes, as well as become more comfortable with the implications that ‘messiness’ might have on the way that they experience conducting and presenting their work (following Bröckerhoff & Lopes, Citation2020).

To illustrate the use of collage as ABR, we draw on an on-going collaboration between the authors that explores topics of consumer culture and the use of ABR in a conflict setting. We provide detailed descriptions of and reflections on using collage individually and collaboratively in practice, as well as discuss ways in which using collage can support researchers in communicating messiness and complexity of research. We begin by providing an overview of ABR and collage as part of it.

Collage as method of art-based research

Art-based research (ABR) is an approach that uses various artistic media and engages artistic processes to develop insight and build knowledge (for more on ABR, see Hervey, Citation2000; Leavy, Citation2009; Seregina, Citation2020). ABR allows researchers to overcome limitations embedded in traditional academic methods by engaging all of one’s senses and working with one’s body in order to gain emotional, relational, and reflexive understanding that goes beyond verbalisation and rationalisation (Barone & Eisner, Citation2012). In practice, ABR focuses on the process of knowledge creation, rather than its product, creating contexts for interaction among researcher(s), participant(s), phenomena, and/or audience(s) that allow for co-created, interactive, discursive, and situated knowledge (see Seregina, Citation2020).

The use of visual media and collage specifically is not new to consumer research (see, e.g. Belk et al., Citation2003; Williams-Burnett & Skinner, Citation2017; Zaltman, Citation1997). Collages have mostly been used as part of a portfolio of ‘projective techniques’ with the aim to help research participants think about and express meanings and sensory experiences, to elicit emotions and narratives, as well as to aid discussion and interviewing. In consumer research, collage has thus mainly been used as a supplement to more traditional methods during data collection. In contrast to this, we employ collage as a method of ABR. In other words, we aim to present collage-making as a holistic, bodily, interactive, and processual approach to research practice. We posit that using collage in this form at various stages throughout a research project can enhance our ability to research and communicate findings from contested spaces.

Collage can be described as ‘visual artworks that are created by selecting magazine images, textured papers, or ephemera; cutting or altering these elements; and arranging and attaching them to a support such as paper or cardboard’ (Chilton & Scotti, Citation2014, p. 163). The process need not be restricted to print media, but can employ the use of any art materials or even materials that are not traditionally seen as artistic (e.g. we used food stuffs in our work). From a practical point of view, collage does not necessitate advanced artistic skills in the same way as, for instance, drawing or painting are stereotypically seen to require. Hence, this approach to ABR may feel less threatening to people who do not normally engage in art-making (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, Citation2010).

The process of making a collage involves analysing and synthesising ideas alongside gathering, selecting, and placing imagery (Leavy, Citation2009). Collage gives space to free association which allows subconscious or potentially hidden meanings to emerge through an embodied practice of combining and juxtaposing disparate imagery. In addition to the actual making of a collage, the process can involve a discussion of, and around, the created art pieces. This enables researchers to identify reoccurring themes from a more traditional interpretive lens, but also allows room for the collage-maker to give voice to and consciously analyse the process, identifying ideas, feelings, and insights that they gained during art-making (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, Citation2010).

Collage-making is particularly suited to research in messy settings, as it can juxtapose ideas, as well as include a variety of interpretations and perspectives (Vaughan, Citation2005). Knowledge created through ABR is bodily, emotional, and interactive, allowing collage-makers to express themselves in ways that they normally could not (Leavy, Citation2009; Seregina, Citation2020). Creating art further allows for easing tensions that individuals may experience due to the topic and/or context of the research. People often find it easier to express and potentially even speak about emotionally or politically difficult topics when they can channel their interaction towards art objects and art-making (Malchiodi, Citation2018). What emerges through collage is thus a process of reflection, revelation, and documentation that hopefully uncovers something for the individual who is making it (Vaughan, Citation2005). These qualities make collage useful to researchers who engage messy contexts in their research.

Creating collages as exploratory and reflexive research practice

In order to illustrate collage-making, we draw from an on-going collaboration between the authors. The collaboration stems from a more traditional qualitative project started by Aurélie, which explored participation in consumer boycott in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) amid liberal peacebuilding. Liberal peacebuilding is an approach to conflict transformation that introduces marketisation to conflict settings with the aim to bring about a reduction in violence and an end to conflict. The lived experience of marketisation in this conflict setting is complex, contradictory, and has deeply transformed Palestinians’ ability to engage market transactions for political purposes (Bröckerhoff & Qassoum, Citation2019; Bröckerhoff, Citation2017).

Soon after Aurélie returned from collecting data in the West Bank in 2016, she began working together with Usva to explore how ABR may offer opportunities to express and present the incongruous and contradicting experiences of consumer culture in the oPt. Broadening the remit of the initial research, our collaboration, to date, has explored the marketisation of this particular conflict setting more broadly beyond the remit of consumer activism. The ABR project has taken on various forms, such as collages and an installation (Bröckerhoff & Seregina, Citation2016, Citation2018).

The collages that we present in this paper were created against this backdrop. The purpose of our collage-making was (1) to individually and collaboratively reflect on our research practices to date, (2) to explore consumerist meanings within the research context, and (3) to identify avenues for future research. We have engaged collage as a tool for strengthening our research practice in what can be a challenging environment in which to conduct research.

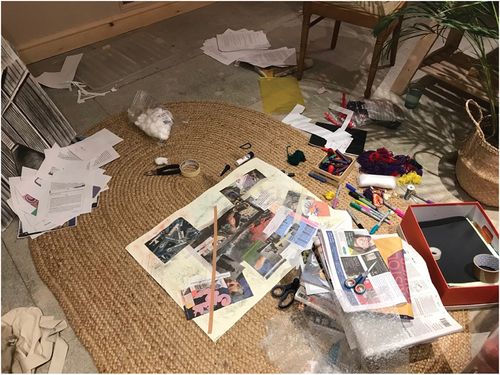

We created both individual and collaborative collages. Our art-making spanned over the course of three days, with the exception of two individual collages made by each author beforehand. Usva came to stay at Aurélie’s house, in which a dedicated space was used for collage-making (see ). As we outline below, each collage focused on a specific aspect of the research process, ranging from the analysis and interpretation of research findings to drawing on existing and new materials to explore themes for future research. The particular angle for each collage was predefined by us as part of planning the research project.

Materials used included printed out primary data quotes, excerpts from published articles, photos, research notes, exchanges/conversations between authors, adverts and product packaging from the research contexts, as well as sketches, designs, and artefacts from our previous ABR work. We further used an array of newspapers, magazines, and general art materials. We brought most of the materials for collage-making into the room at the outset of the research process, with additional materials being printed out and gathered at study-relevant locations.

Each collage-making session took 60–90 minutes (less for individual collages and more for collaborative ones). We discussed the topics of the research as well as practicalities of collaboration during art-making. In addition, we debriefed each collage-making process and resulting collage in interviews. The interviews took the form of an open-ended discussion of the process of collaging, as well as the ideas, emotions, and experiences it brought up. Both the discussions and debriefs were audiotaped and transcribed. We photographed the physical collages for documentation. In what follows, we present our collages alongside reflections on the process of making them, as well as the ways in which we debriefed them.

Individual collages – setting the scene

The first collages were created individually prior to meeting up. Each of us had a particular brief, focused on each author’s experiences: collage and art-based research as a method (Usva) and the occupied Palestinian territory as research setting (Aurélie). The aim of these collages was to take stock of our collaboration to date, an opportunity for kick-starting discussions and reflections around the use of collage as art-based method to communicate messiness in contested spaces. This formed the basis for the collages we created later.

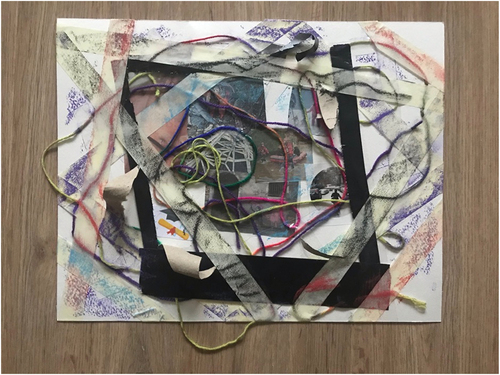

Usva: The aim of this collage (see ) was to capture and express art-based research (ABR). I wanted the process to be emergent and hence I did not plan or prepare. I started with a blank piece of paper, some newspapers and magazines, as well as an array of art supplies. The lack of a plan did not feel intimidating, but a welcome challenge. However, the idea of representing ABR as collage felt a bit daunting, because it was so meta: what if I couldn’t capture the essence of ABR?

I felt that, in the end, the collage was successful in capturing the idea of ABR for me, formed by a striking amount of layering, as Aurélie notes when interviewing me about the collage. The process of layering was important for me to understand and uncover the underlying idea of ABR, allowing me to gain metaphors for how I define it. I went through a process of trial-and-error, with many materials that I tested out not making it to the final collage. I nevertheless left traces of this as seen in the bits of cardboard and tape. Overall, the process was quite frustrating most of the time, as I was not sure where I was going. Yet this frustration felt productive and important. I was able to enter a state of flow and ultimately reach a moment of discovery.

The first layer of the collage was formed by newspaper and magazine clippings. I began by looking through the paper materials that I had, and cutting out images that caught my eye. The images that spoke to me were of people in various difficult terrains, such as floods or snow storms. I realised that the metaphor of ‘wading through’ was important for my collage. As I was arranging and gluing on the chosen images, it came to me that this is how I feel about ABR or even research in general: you are flooded with huge amounts of information and you have to find your way in it.

The second layer of the collage was formed by string (see ). Initially I layered the string on top of my collage with an aim of connecting images. After trying this out in a few different ways, I ended up with a swirl pattern, which, in the end, became quite chaotic through the use of various string. The string is not stuck to the paper perfectly: it still moves around. Just like ABR, the string does not have a final, set shape and it changes as we interact with it. The choice of colour for the string was not deliberate, but the aim was rather to bring in as much colour as possible. Retrospectively, I realised that ABR for me is about bringing colour and life to research.

The next layers were formed of various tape. I initially used clear tape to stick the string to the collage, purely out of practical reasons. But I liked it there so I next used the black duct tape in order to delimit the chaotic image with strong motions. Just like in more traditional research, we often need to frame our context, sometimes in quite aggressive ways. A bit of the tape came off, but I left it as is because I thought it was funny that you can try to delimit things, but the material may rebel against you. Lastly, I used masking tape. I laid it down in different shapes; initially as just one triangle, which then became an intricate web of frames (see ).

I began to go over the masking tape with black pastel and later also various coloured pastels. The initial idea was to give it some texture. As I was doing this, the various underlying layers began showing up on the tape, the most vivid of which was the string, forming beautiful and vivid swirls on the surface of the tape. Something clicked: this is what ABR is about! It is about uncovering understanding through a mass of layers, about findings emerging from wading through information, about discovering meaning that expresses a particular context at a particular time.

Making this collage gave me an idea or a representation that helps me define the process of ABR and how I feel about it. The metaphors of wading and layering emerged as central takeaways.

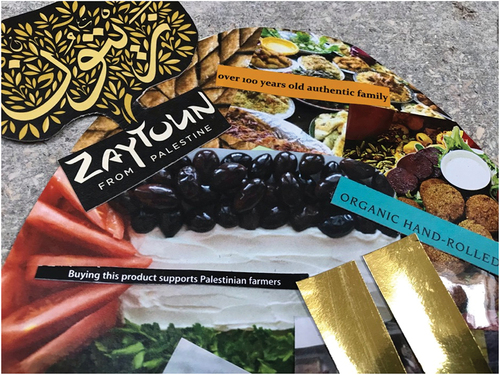

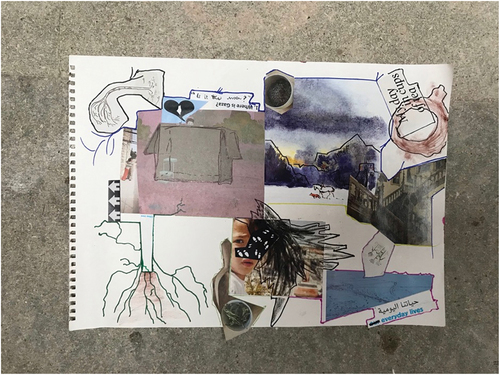

Aurélie: This collage (see ) reflects the research context, i.e. consumer culture in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt). The collage juxtaposes multiple conflicting ideas pertaining to the research context: global vs local consumer culture; development vs conflict; tradition vs modernity; presenting a ‘resolved, one-dimensional narrative’ vs multifaceted experiences of consumer culture. These are also presented as an organic whole; differentiating any of these disjunctures would feel like sanitising the layered and contradictory experiences of consumer culture in the oPt.

I sourced materials focusing on predominant symbols of consumer culture: for example, Snickers, Kellogg’s, and Pringles are all globally available products. These branded foods of Western consumer culture juxtapose with the mainly unbranded food products I chose to represent Palestine (see ). Food politics is a huge issue in the oPt – many people I spoke with expressed that the spread of global consumer culture – in addition to the ongoing violent occupation – was eroding their traditional food culture as well as their food sovereignty.

I chose to cut out and incorporate terms like ‘handmade’ and ‘organic’. Traditional Palestinian food growing and preparation is local, organic, small-scale, and artisanal. Food activists in Palestine and across the globe hold an almost romantic reverence towards those ways of production in light of global mass production. Efforts are made to maintain an appreciation of artisanal small-scale farming across the oPt with a population that may increasingly be moving towards the offers of global consumer culture. With food and politics so strongly linked in this research context, the conflation of liberalisation with development and conflict is most strongly visible here. This is represented by the two golden exclamation marks (see ). To illustrate the more globally removed positionality of Palestinians, I chose to depict Israeli products as those where global and local cultures meet and merge.

The collage represents the conflation of Western, Israeli, and Palestinian daily food products into the shape of the rooster. Initially I had thought of bringing these food elements together in the shape of a ticking time bomb or hourglass, but during the process of gathering materials, this felt too simplistic. A rooster symbolises the start of a new day and new opportunities arising, but it also points to aggression and threat. My research participants experienced consumer culture as anything from a place of empowerment to a mechanism of oppression, a threat to their traditions, as well as the survival of their nation amid conflict. I had a ‘Eureka’ moment when I decided to opt for the rooster, as it represents the hope and despair, joys and frustrations, of the context simultaneously. The different products sharing a body means that they are all part of the same organism, coexisting and conflicting.

I loved making this collage, although I also felt tense throughout the process. I worried about misrepresenting particular angles of the problematics pertaining to the topic, of exaggerating or simplifying certain elements. However, I loved the freedom of making the collage, as I could raise issues without needing to convincingly argue or resolve them. I didn’t need to worry as much about ‘choosing the right words’. I placed the images to encapsulate my intended meanings, but these can also be interpreted differently by others in ways that are meaningful to them.

Overall, the first collages helped us set the scene for our research, reflect on what we had done so far, as well as test out the process of collage-making and debriefing. Most importantly, we were able to communicate aspects of our understandings that may have otherwise remained implicit. We further felt we were able to better express the topics of our respective collages and gain a more in-depth understanding of our approaches towards them.

Collaborative collages – taking stock and representing research

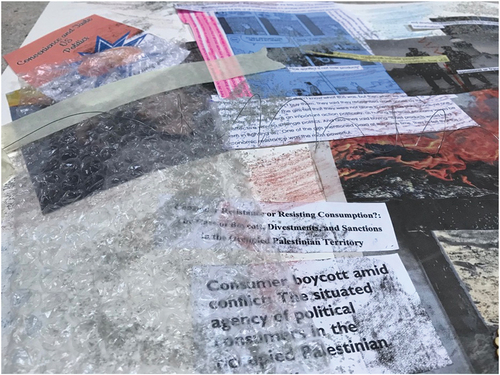

In our first collaborative collage, we responded to our existing research on the topic of marketisation in the context of Palestinian food consumption. We wanted to explore what meanings emerge when co-creating a collage based on an existing collaboration. Alongside art materials, we used a lot of the existing, more traditional research data and its analysis, such as research notes, photographs, and interview transcripts. In this collage, we collaboratively explored the opportunities of collage in conceptual communication and presentation of meaning.

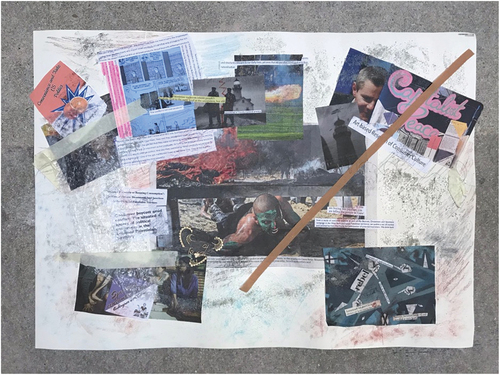

Image 8. The first collaborative collage, which is responding to and representing existing research on the topic of consumer culture in the occupied Palestinian territories.

Aurélie and Usva: We began making the collage (see ) with quite a long process of cutting out images and bits of text from newspapers, magazines, research materials, and documentation. This was very much still an individual process of going through available media to choose elements for our art-making.

Having separately gathered bits to work with, we slowly began bringing it all together. Usva started the process by combining bits of text with images. This brought new meaning to the images, thus changing or stressing certain elements. Aurélie framed a comic strip with a variety of quotes of what participants had said about the context: a range of views that are important to reflect, she stressed. In the middle, it says: ‘the conflict is not over products’. Usva pointed out that they were unsure about using too much text, as this might depict pre-defined meaning and thus limit the interpretive, analytical potential of the collage.

After some moments of playing around with imagery, we began testing out how to arrange the images on paper, negotiating and discussing research-related topics. We first arranged images into groups thematically, but something felt like it was missing. We then decided to place the large image of military training in Gaza in the middle of the collage. To us, it represents the omnipresence of institutionalised violence that forms the backdrop of research in this context. This seemed to pull the collage together: the other images and quotes were placed around the large image as if radiating out from it. We now felt better about the collage and began to glue images onto the paper. Once we were finished gluing, we were nevertheless still experiencing a sense of unfinishedness.

As a response to our feeling about the collage, we explored other art materials. We first covered any remaining white paper with various earth-shade colours of crayon, as the white space felt out of place. We drew around, but also over images to create a feeling of messiness. The texture of the woven rug we were working on came through on the paper, giving a grittier look to the collage. We found some grey powder and decided to glue this all over the collage to represent ash (see ). We further obscured the quotes and images with some bubble wrap (see ). Here, we clearly began working together: we stated our ideas and suggestions more directly, nevertheless giving room to one another to respond. As we worked more interactively with one another and with different art materials, the process began to feel more expressive. The collage started coming together as a meaningful entity.

At the very end of the process, Aurélie noticed some wire. She unravelled it as a spiral in a way that it looks like barbed wire; it felt an apt way to express conflict. We put it across the collage and taped it down (see ). The collage was finished.

Messiness and dirtiness seemed to pull the collage together, emerging as the main underlying concepts or logics of the art piece. In the debrief, we reflected that this may be due to the messiness of presenting research findings from conflict settings. It contrasts with conventions of communicating academic research that has a tendency of sanitising contexts. We liked how images and text merged into one entity with no hierarchies in the collage. At first glance, it seems impossible to tell what is data, context, dissemination of research, or abstract reflection. None has primacy over the other. The images are striking but don’t stick out. In parallel, when conflict becomes daily life, it also no longer sticks out. In the oPt, activists campaign for the public recognition of occupation-related restrictions to prevent their normalisation.

The process of making the collage ended up being an explorative, experimental one, through which we learned how to work together in collaborative art-making, as well as how to share resources and findings. The process felt a bit careful, as we were still finding each other’s boundaries, roles, and modes of working. We discussed our actions in a lot of detail: what to cut out or not, what to glue on or not, how to place things and in what order. Such a long process of selection may have been due to the fact that we were responding to a wide array of textual data that we wanted to represent. Moreover, we found that we may have given ourselves a bit too much freedom in the amount of art supplies we had gathered for our use, which made it difficult to choose and start working with specific materials.

The collage represents the messiness of the research context and the process of engaging in research within that context. We find that the collage gives the research phenomenon coherence. This does not need to be cleaned up, but can rather exist in its messy state of interconnected elements.

Collaborative collage – engaging research contexts

In the second collaborative collage, we explored the research context more freely, without the backdrop of previous research. For additional materials, we gathered flyers and food products at study-relevant locations to inspire us and to be used in the collage. We collected the materials together, which helped set the tone and collaborative feel to the collage (see ) early on.

Image 12. The second collaborative collage, which is an exploration of the context of consumer culture in the occupied Palestinian territories.

Aurélie and Usva: Thinking about the ways in which food can anchor experiences, we began by discussing Palestinian food and tasting some sumac and za’atar (common spices used in Palestinian cooking). This led us to incorporate food items into the collage-making. We also liked that it would make the collage multi-sensorial, alluding to the opportunities of ABR to engage us as researchers on various experiential and emotional levels. We attached dried sage with a piece of string to the collage (see ) – it looks like an uprooted olive tree (olive trees being one of the symbols of Palestine and a source of livelihoods). We also created a figure of a human made from sumac and za’atar punching the air or holding a Palestinian flag (see ). Depicting a person from spices added to a sense that the research topic is related to people’s daily, embodied experiences.

At one point, when selecting and discussing materials for the collage, we discussed creating street art as part of the collage. Street art in the West Bank, including that made by famous international artists such as Banksy, already has a place in addressing Palestinian experiences of occupation. We made our own ‘graffiti’ as a response to this: we attached a ‘capitalist peace’-graffiti made on separate paper and wrote ‘everyday consumption’ across the entire collage with a crayon (see ). These are the two underlying concepts guiding this exploration.

We extensively discussed the shape of the collage with the possibility of clustering it into sections, such as a business section, a food section, an arts section, and a ‘political’ section. As Aurélie requested moving an image further in, we began envisioning the layout in general. We decided to create a very crowded-looking collage with overlapping imagery. We removed any uncovered paper and ripped off the remaining straight edges of the paper, as it felt too constraining. We found that this reflects the multitude of interconnecting issues of the research context. The jagged edges reflect conflict and blurred borders. The rips and holes made into the collage express the disappearing geography for Palestinians that becomes increasingly punctuated by Israeli annexations and settlements.

The shape of the collage became circular with jagged edges and no specific focal point. As a result, the collage reveals itself in a multitude of shapes and meanings depending on the viewer’s perspective. The holes change the collage depending on the surface that it rests on, adding further sense of layered meanings (see ).

The collage lacks specific focus or direction, but evokes a sense of urgency. To us, this reflects the coexistence of conflict with everyday life, which can feel inconceivable to those not living their daily lives in that manner. By juxtaposing different images and materials, meanings are crammed together as if there is no space to breathe. This also represents the complex, layered, and multi-faceted nature of the research, as well as our positionalities as researchers in that setting – unpicking a lot of issues and looking into various different avenues.

Towards the end of the process, we were unsure how to finish. The collage felt incomplete to us, so we ripped the edges some more, peeled away more paper to enhance the messiness. Usva now felt like the collage was coming together, but stress that they could have continued working on it for much longer. We reflected on our experiences of collage as a potentially never-ending process.

This process of collage-making felt more collaborative: we worked together on the same sections, not just sequentially or in parallel. We discussed images and their possible meanings, exploring what these mean to us and working together from these conversations. We further felt more comfortable challenging or developing each other’s ideas, most likely because of the developed trust and mode of working together. We were finding comfort in the potential for open-endedness afforded by collage.

The collaborative collage-making allowed us to engage topics and themes beyond those immediately present in our research to date: the relative visibility of Palestinians compared to other people’s living under occupation; chain restaurants in the West Bank and the local appropriation or imitation of global consumer brands; the impact of international assistance in conflict areas; the banality and politics of consumer culture. The collage further made us appreciate the value of iterations: collage as a process can be used for anything from developing an idea to engaging in a process. In our debrief, we reflect that it is the beauty of ABR that we don’t need to resolve issues in a collage in the same way that you would in a paper. Meaning can be emergent, multi-faceted, layered, unfinished, and open-ended.

We came to understand that collages are useful for getting ideas into form and into our direct understanding, without needing to know exactly and immediately how to go forward with them. The process offers a broad base and comprehensive overview from which to develop ideas and research projects further.

Individual collages – reflections on collage-making

The aim of the final, individual collages was to reflect on the entirety of the collage-making process, as well as to explore topics and ideas that may form the basis of future collaborations.

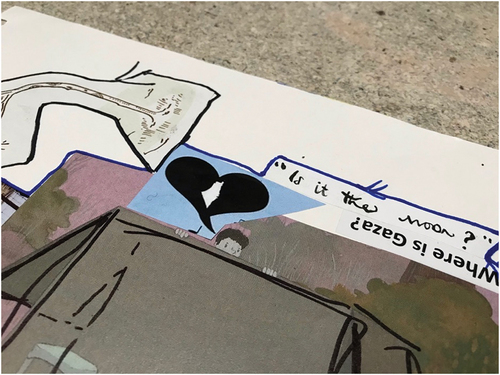

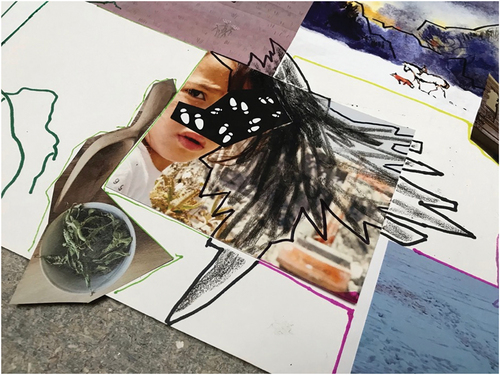

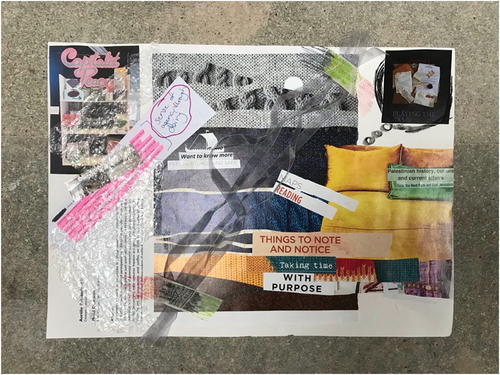

Usva: Reflecting my first individual collag (see ), the process of making this collage (see ) was quite unplanned and emergent. However, experientially, the process was much more cognitive, rational, and acknowledged than my other collages; a methodical way of doing ABR. The end result is the least layered of my collages, as Aurélie points out in the debrief. This collage was about showing a process or building a pathway, in which layering did not feel appropriate. The collage-making clearly involved less emergent work and flow, focusing more on thinking and reflecting.

I began once again with looking through magazines for images. However, instead of formulating a coherent entity before gluing things on, I decided I wanted to glue everything as it came up. It felt like this reflected the uncontrollable nature of doing research: we deal with it as we go. Aligning the images became quite important, that is, gluing them in a way that straight lines and corners would meet perfectly. In reflection, this action expressed the process of finding how elements that were not planned to fit can fit together somehow.

The main chosen images were important. The image of the box resonated with me, as I felt like this research project is the wilderness, and we are either putting it in a box or putting a box in its context. I am peeking out and looking at all the other images to figure out what is going on (see ).

The image of the child reflects my strong response to children in Palestine. They are presented a lot in media and research, and I always find it shocking to see young children who grow up in difficult conditions. I placed the image of shoeprints over the child’s face, as it feels that their rights are being trampled. The hair I extended with crayon and marker, turning it into an entity that comes from the outside and takes over (see ). Aurélie sees an explosion in that image, which I find to be a fitting interpretation. This is where I first start outlining images with marker, a process that later becomes an important element of the overall collage. This represented the notion of abstract elements as part of our work, which we have to outline strongly in order to present them.

Images of different pathways or crossroads represent a multitude of directions, out of which we can only take one. This has to be a very conscious decision, which is supported by the outlining with a marker. The stairs are a very neat example of decision-making, whereas the tracks in the snow show the reality of it. There is a clear track, but another has gone around it; someone has walked in circles and someone else has jumped on the spot. The image of the horse and the fox walking in the snow shows choosing one path and exploring unknown terrain: it’s dangerous, but one can hope that there is a beautiful sunset at the end. All of these images further reflect the research context: there is so much research done in Palestine, but our project has to pave a new way within it.

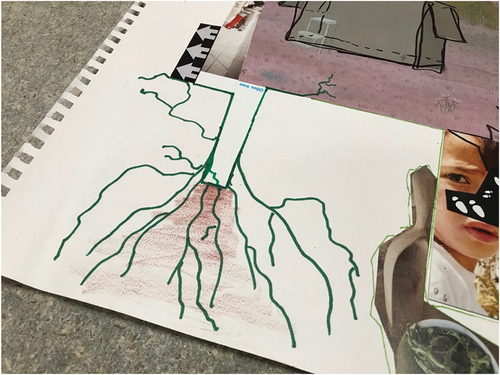

The plants scattered throughout the collage were important, as they represent life growing in unexpected places. The most important one emerged from the text ‘olive tree’. I turned the text into a tree with long roots (see ). The dual meaning of olive trees as both cultural and physical is important, as olive trees form the roots for Palestinians and their way of life, but also feed them and fuel their economy. I further felt that the image looked like a factory furnace, so I added some smog. Capitalism is coming to override everything in its path.

I included text-based images, which I would not have normally done before. Influenced by our work on the previous collages, I found that using text can bring a different type of depth to the collage. ‘Where is Gaza?’ turns into an abstract question of not only where it is physically, but also in terms of who it belongs to, how we think about it, and where it is within research. I imply that perhaps it is ‘ … the moon’, as it feels alien and distant to those in a Western context. In ‘Our Everyday Lives’, I crossed out ‘Our’, as it is not my life, but someone else’s (see ). Yet as outsiders we have more rights in Palestinians’ homeland with our foreign passports.

In the end, I am left with a feeling of incompletion. Still looking at the collage now, I do not think it is finished. However, I think the process that it represents is not finished, and hence this feeling of lack of finality is important and one I am happy to live with. The collage nevertheless helped me uncover how I feel about and approach the research process for this project, directing me towards the future.

Aurélie: Making this collage (see ) felt a lot more liberating than the first collage. The theme of the collage allowed me to explore my own entanglements and emotions more explicitly, resulting in a flow less burdened by previous research. Having spent time making collages first on my own and then with Usva has meant that with each collage I was able to accumulate experience for subsequent collages. The result is a more texturally varied and layered collage.

It took me just over half the time to make this collage compared to the first one. I partly attribute this to the fact that I just used materials that were in front of me in quite an emergent manner. In fact, I worked with one magazine only, which led me to the ‘Eureka’ moment a lot quicker through finding the central imagery of this collage, which represents comfort and exploration. Discovering these central underlying tenets allowed me to quickly assemble materials from the available resources.

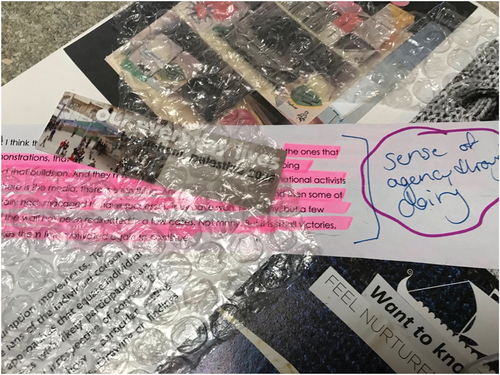

The collage flows from left to right. To the left are materials from previous work, both my own and from the collaboration with Usva: a picture of our art piece, data, and literature cut outs, the front page of a publication. I used bubble wrap to obscure these, which reflects the psychological and intellectual shift I made over the course of the collage-making project (see ). I feel as if I have shifted focus from where I have been with the research towards new horizons.

The cut out of a data excerpt has my own annotation next to it reading ‘sense of agency through doing’. This overlaps with the central section of the collage – a boat charting a course across a sea of knitwear. With renewed energy, I felt myself to be (on) that boat, keen to explore new places and spaces. For the central section, I cut out words from magazines that meaningfully reflected behaviours (reading, map making, taking time, noticing) and intentions (nurtured and safe, with purpose).

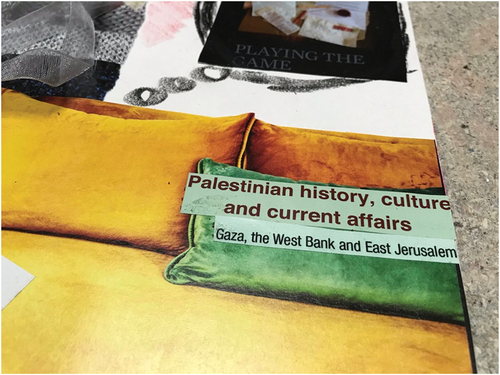

To the right, a sofa with cushions represents the act of getting comfortable and processing the ideas coming out of our collaboration, as well as planning this paper and future research. The latter is represented by the two cut outs reading ‘Palestinian history, culture and current affairs’ and ‘Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem’ – both are broader than my research to date (see ). I positioned a thought bubble reading ‘playing the game’ into the background, the academic game being something that will (have to) be on my mind as we progress.

Over the top, I added some frill in the form of ribbon and tape that I painted in the colours of the Palestinian flag. The loosely attached ribbon is a little bit shiny, but also see through, because I wanted it to embellish without taking over, and for the underneath to remain visible (see ). These additions are a nod to context, but also to working together. Prior to working with Usva, I wouldn’t have thought about adding different fabrics and layers in this way, so I wanted to reflect that.

Although the collage is messy, it also feels more focused and clear. As I am writing this, I realise there is a lot less to untangle for me in this collage compared to the first individual one. It was a more emergent process, during which I spent less time at the outset planning and analysing potential meanings. I can’t help but think that this is a reflection of my own journey and my growing confidence in using collage as an art-based method.

Through the individual collages, we were able to reflect on the multiplicity of perspectives and meanings embedded in our collaboration, as well as in our engagement with the research setting. Throughout the process, we were able to track how we both responded to the messiness of the research context, while also learning to navigate each other’s positionalities towards emerging themes and the context of the occupied Palestinian territory. We found we were able to incorporate positionalities that were at times complementing, and at times, contradictory, without this somehow creating a disconnected experience of our collaboration, or, more so, of our ability to communicate and present the research setting.

We were further able to track our development as collage-makers, both individually and collaboratively. Most striking is our almost mirrored development in our approach to the process of and attitude towards collage-making. Through working together, we seem to have learned from one another and picked up different ways of working. Usva’s work in collage became much more planned and analytical, while Aurélie felt that she was able to become more free, liberated, and emergent in her work. Moreover, in having worked on collages in multiple iterations, we became much more confident in our work both alone and together, allowing us to push the limits of collage as a medium for open-ended meaning-making.

Reflections on using collage in messy research settings

As we show throughout this paper, collage-making as an ABR approach can be used throughout the research process to aid the exploration, understanding, and expression of culturally embedded, multi-faceted meanings. Moreover, collage is especially useful for research in contested spaces, as it allows for different modes of interaction and expression that are particularly suited for representing messiness.

To summarise, we highlight the opportunities for collage as ABR in engaging and communicating consumer research, especially when researching contested spaces that are defined by messiness. Firstly, collage allows researchers to consider and present configurations of meaning embedded in their work. In other words, in using collage, the focus can turn to situated connections between the component elements of a research project, as well as processes by which these elements come together or fall apart. Collage thus allows presenting and communicating complex constellations of meanings that emerge in the exploration of lived experiences, but may not always be compatible with pre-existing structures of research tradition.

Secondly, the exploration and presentation of meanings through collage can be multiple, layered, overlapping, or even contradicting. Collage allows for addressing a multitude of meanings simultaneously, which may not make sense when presented together in more traditional formats of academic work. It further forgoes the need for narrative structure, and can therefore simultaneously point to a variety of interpretations or present juxtaposing ideas. In this way, collage gives research multi-sensory and multi-faceted depth.

Thirdly, communication through collages and in collage-making goes beyond language, letting researchers and research participants engage topics that are difficult to verbalise. Limitations of verbal representations may arise for many reasons: lack of norms for expressing difficult or even taboo topics; embarrassment, fear, or shame; lack of conscious experience or critical distance from an issue. Furthermore, in cross-cultural research, collages can reduce cultural and linguistic barriers by creating a pictorial, embodied connection with context, topics, and/or participants.

Fourthly, collage can help researchers and participants to explore and present phenomena that carry emotional or political sensitivity. The method aids in uncovering meanings or interpretations one was not aware of, forming new connections and relationships, as well as providing ideas for future developments. The widespread use of collage in art therapy (e.g. Malchiodi, Citation2018) attests to the ‘therapeutic potential’ of collage in a variety of settings: collage has the potential to unlock deep-seated, often unconscious experiences and understandings. The many Eureka moments that we experienced in the collage-making illustrate this point. To us, these moments have highlighted how much we can gain as academics when we allow ourselves to access deep-seated, spontaneous responses to our research context, be they emotional, cognitive, or physiological. In a similar vein, Cunliffe (Citation2016) refers to these ‘struck bys’ as the moments of learning in a critically reflexive academic practice. Allowing ourselves to engage in embodied, subjective responses to our research in this way may thus help us unearth meanings and connections that we would otherwise not find.

Finally, collage creates novel opportunities for collaborative research, as it allows for expression, communication, and co-creation via emotive, bodily means that are not accessible via language-focused traditional research processes. Collage-making can involve insecurity, lack of clarity, and general feelings of unease, as the process asks the researcher or research participant to take a leap of faith, as well as to open up to others in (potentially) vulnerable ways. In working collaboratively, collage-makers are pushed to express emotions and experiences through bodily activity as well as learn to give room for others’ expressions, thus exploring boundaries, building shared trust and understanding, as well as learning to assert one’s own voice. Ideas and analysis develop collaboratively, letting embodied experiences inform and guide meaning-making.

As it becomes apparent, collage allows researchers to address and face the messiness of contested spaces in a way that does not compromise the multiplicity of meanings inherent to such contexts. Collage brings together disparate elements, permitting researchers to see issues from a multitude of perspectives and to present experiences in ways that may not be easily accessible via other means (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, Citation2010; Vaughan, Citation2005). The process of making collage further incorporates layers of artistic, theoretical, and intersubjective knowledge, allowing for intricate overlapping and interweaving of meanings (Chilton & Scotti, Citation2014). In line with other researchers who have methodologically delved into the potential of messiness in research (e.g. Avner et al., Citation2014; Law, Citation2004), we found that engaging collage helps resist reducing diverse experiences and perspectives into a single, often hegemonic (Merilӓinen et al., Citation2008), voice. The approach further challenges and restructures established academic norms, thus showing transgressive potential.

Embracing the messiness of research through the use of collage allows for critical, embodied engagement of research contexts as well as the communication of multiple viewpoints, pushing researchers to work outside the linear organisation of academic work. By working beyond sanitised structures that direct meaning and social reality into predetermined formats, research can focus on exploring experiences and presenting multi-faceted meanings from a variety of perspectives simultaneously. Taken on as an ABR approach, collage engages the topics and contexts of research as they are lived, rather than as raw material to be placed into existing structures of research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aurélie Bröckerhoff

Aurélie Bröckerhoff is a research fellow at the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University. Primarily using ethnographic and arts-based methods, her research explores how (the politics of) spaces of consumption shape everyday social relations. Before joining academia, Aurélie has worked in international development and social policy, and her work continues an international focus.

Usva Seregina

Usva Seregina is a visual artist and a researcher of consumer culture. Their academic work focuses on exploring topics of consumerism, consumer agency, and gender performance, as well as developing art-based research methods.

References

- Avner, Z., Bridel, W., Eales, L., Glenn, N., Loewen Walker, R., & Peers, D. (2014). Moved to messiness: Physical activity, feelings and transdisciplinarity. Emotion, Space and Society, 12, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2013.11.002

- Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2012). Art-based research. Sage.

- Belk, R. W., Ger, G., & Askegaard, S. (2003). The fire of desire: A multisited inquiry into consumer passion. The Journal of Consumer Research, 30(3), 326–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/378613

- Belk, R. W., Kozinets, R. V., & Elliott, R. (2005). Videography in marketing and consumer research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 8(2), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750510592418

- Bröckerhoff, A. (2017). Consumer resistance or resisting consumption? The case of boycott, divestment, and sanctions in the occupied palestinian territory. In A. Özerdem, C. Thiessen, & M. Qassoum (Eds.), Conflict transformation and the palestinians – the dynamics of peace and justice under occupation (pp. 165–177). Routledge.

- Bröckerhoff, A., & Lopes, M. (2020). Finding comfort in discomfort: How to early-career researchers are learning to embrace ‘failure’. Emotion, Space and Society, 35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100671

- Bröckerhoff, A., & Qassoum, M. (2019). Consumer boycott amid conflict: The situated agency of political consumers in the occupied palestinian territory. Journal of Consumer Culture, 21(4), 892–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540519882483

- Bröckerhoff, A., & Seregina, A. (2016). Shopping at capitalist peace. In Consumer Culture Theory Conference. Organised by Skema Business School, Lille, France, 6-9 July.

- Bröckerhoff, A., & Seregina, A. (2018). Shopping at Capitalist Peace. In Everyday Resistance of Kurds And Palestinians: Countering Domination via Nonviolent Means Conference. Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations (CTPSR), Coventry, UK, 22-23 June.

- Brown, S. (2011). Animal crackers: Making progress on the penguin’s progress. Consumption Markets and Culture, 14(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2011.604497

- Butler-Kisber, L., & Poldma, T. (2010). The power of visual approaches in qualitative inquiry: The use of collage making and concept mapping in experiential research. Journal of Research Practice, 6(2), 1–16.

- Canniford, R. (2012). Poetic witness marketplace research through poetic transcription and poetic translation. Marketing Theory, 12(4), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593112457740

- Chilton, G., & Scotti, V. (2014). Snipping, gluing, writing: The properties of collage as arts-based research practice in arts therapy. Art Therapy, 31(4), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2015.963484

- Cunliffe, A. L. (2016). Republication of ‘on becoming a critically reflexive practitioner’. Journal of Management Education, 40(6), 747–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916674465

- Dion, D., Sabri, O., & Guillard, V. (2014). Home sweet messy home. Journal of Consumer Culture, 41(3), 565–589. https://doi.org/10.1086/676922

- Douglas, M. (1967). Purity and danger: An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Downey, H. (2016). Poetic inquiry, consumer vulnerability: Realities of quadriplegia. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(3–4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1103301

- Hervey, L. W. (2000). Artistic inquiry in dance/movement/therapy: Creative research alternatives. Charles C Thomas.

- Hietanen, J., Rokka, J., & Schouten, J. W. (2014). Commentary on Schembri and Boyle (2013): From representation towards expression in videographic consumer research. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 2019–2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.009

- Hutton, M., & Heath, M. (2020). Researching on the edge: Emancipatory praxis for social justice. European Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0150

- Law, J. (2004). After method mess in social science research. Routledge.

- Leavy, P. (2009). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. Plenum.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2018). Creative arts therapies and arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook for arts-based research (pp. 68–87). Guilford Press.

- Merilӓinen, S., Tienari, J., Thomas, R., & Davies, A. (2008). Hegemonic academic practices: Experiences of publishing from the periphery. Organization, 15(4), 584–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508408091008

- Micheletti, M., & Oral, D. (2018). Problematic political consumerism: Confusions and moral dilemmas in boycott activism. In M. Boström, M. Micheletti, & P. Oosterveer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political consumerism. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190629038.013.31

- Modrak, R. (2015). Learning to talk like an urban woodsman: An artistic intervention. Consumption Markets and Culture, 18(6), 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1052968

- Ozanne, J. L., Moscato, E. M., & Kunkel, D. R. (2013). Transformative photography: Evaluation and best practices for eliciting social and policy changes. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 32(1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.11.161

- Schouten, J. W. (2014). My improbable profession. Consumption, Markets & Culture, 17(6), 595–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2013.850676

- Scotti, V., & Aicher, A. L. (2016). Veiling and unveiling: An artistic exploration of self-other processes. Qualitative Inquiry, 22(3), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415605055

- Seregina, U. A. (2020). Co-creating bodily, interactive, and reflexive knowledge through art-based research. Consumption, Markets & Culture, 23(6), 513–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2019.1634059

- Sherry, J. F., Jr., & Schouten, J. W. (2002). A role for poetry in consumer research. The Journal of Consumer Research, 29(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1086/341572

- Vaughan, K. (2005). Pieced together: Collage as an artist’s method for interdisciplinary research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690500400103

- Williams-Burnett, N. J., & Skinner, H. (2017). Critical reflections on performing arts impact evaluations. Arts and the Market, 7(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAM-11-2015-0017

- Wood, M. (2015). Audio-visual production and shortcomings of distribution in organisation studies. Journal of Cultural Economy, 8(4), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2014.942346

- Zaltman, G. (1997). Rethinking market research: Putting people back in. Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379703400402