This special issue on ‘Influencer Marketing: Interdisciplinary and Socio-Cultural Perspectives’ aims to discuss, problematise and stimulate debate on how influencer marketing, its consumption and wider implications for the contemporary world can be examined and re-thought from socio-cultural and interdisciplinary perspectives. Influencer marketing is a growing area of interest both inside and outside of the academy. Brands are increasingly devoting their marketing budgets to influencer marketing, which has grown into a $21.1 billion industry (Geyser, Citation2022). Whilst many definitions of influencers exist, most describe influencers as digital content creators who aim to gain the attention of a ‘following’ on social media and influence the behaviour of this audience through representations of their everyday lives in which commodities play a vital role (Drenten et al., Citation2020). In this ‘demotic turn’ (Turner, Citation2010), ordinary people have become increasingly visible in marketing, giving power to ‘real’ voices (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019) who use social media as a megaphone to reach mass audiences (McQuarrie et al., Citation2013) and then monetise their following across an array of contextual lifestyle boundaries such as food, fashion, family, technology, politics, activism and health. However, influencer marketing is underscored by dynamics and inequities that are often overlooked in the hype that surrounds this ‘authentic’ way of influencing and connecting with consumers.

In this introduction to the special issue, we take up the challenge to critically and culturally interrogate influencer marketing and create pathways to connect scholarship across fields. Our goal is to offer a unique interdisciplinary and socio-cultural voice to the burgeoning literature and special issues on influencer cultures and marketing. Recent contributions in this regard include special issues and sections in advertising scholarship that explore the efficacy and consumption of influencer marketing (Hudders & Lou, Citation2022) and how advertisers can best leverage influencers (Rosengren & Campbell, Citation2021), with in press special issues in business and marketing dedicated to examining virtual influencers (Koles et al., Citationin press), implications of influencers and influencer marketing for consumers and society (Mardon et al., Citationin press) and the ways influencers can be leveraged for the ‘greater good’ to encourage sustainable and pro-social behaviours (Gerrath et al., Citationin press). In other fields, recent special issues have covered wide ranging topics, including influencers and strategic communication (Borchers, Citation2019), political influencers (Riedl et al., Citation2023), influencer governance and regulations (Abidin et al., Citationin press) with a range of compilations in press on creative industries (Karhawi & Amalia Dalpizol Valiati, Citationin press), wanghong (Abidin & Shen, Citationin press), hospitality and tourism (Cheah Shenzhen et al., Citationin press) and mapping the phenomenon of influencers (von Sikorski et al., Citationin press).

Together, the above collections advance our understanding of influencer marketing from a variety of standpoints yet remain relatively siloed. Our special issue aims to connect these perspectives, bringing together voices from marketing with other fields both in terms of contributors to the special issue and the approaches taken across the papers. This clearly resonated with scholars, our call for papers initially attracting 42 submissions, with 19 papers being sent out for review and a final collection of 8 papers forming the special issue. The authors of these papers are predominantly early to mid-career scholars and hail from a range of places around the world, including Sweden, Canada, Australia, America and the United Kingdom. This array of voices enriches the collective contributions offered and speaks to the growing scholarly interest in influencer marketing across the academy.

The remainder of this Editorial is structured as follows. First, we undertake a focused and non-exhaustive review of interdisciplinary research on influencer marketing to set the scene on scholarship to date on the topic. Second, we introduce our influencer marketing symbiosis/parasitism framework as a lens through which we can examine the influencer marketing ecosystem and unpack the dynamics of reliance and exploitation that pervade it. Third, we provide a summary of the eight articles published in this special issue and map them against our framework, bringing to life the complexities of influencer marketing and the numerous social and cultural issues that intersect and are produced by it. Finally, we conclude with future directions for research to guide scholarship on influencer marketing, with the aim of promoting more interdisciplinary, critical and socio-cultural research on influencer cultures in the marketing field and beyond.

A non-exhaustive genealogy of interdisciplinary research on influencer marketing

Modern influencer marketing emerged throughout the 2010s alongside the rise of social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. These Web 2.0 platforms enabled so-called ‘regular’ people to amass followings by sharing their relatable and seemingly authentic day-to-day lives. Brands recognised the opportunity to leverage this attention often by sending them free products to review or post. Thus, the influencer marketing industry was born.

Today, influencer marketing is a thriving industry fuelled by advertising dollars, internet culture, and the ongoing competition for attention (Hund, Citation2023). As a marketing tactic, the early use of influencers dominated lifestyle domains such as beauty, fashion, fitness, home, and travel; however, modern influencers are deployed across unexpected arenas including mental health, financial services, and even controversial products such as tobacco and firearms. The influencer industry has rapidly evolved. What was once a seemingly scrappy, cost-effective marketing fad is now a robust ecosystem of influencers, marketing agencies, journalists, brands, consumers, platforms, and regulatory institutions.

Modern social commerce is reflected in cultural rallying cries such as ‘TikTok made me buy it’ (Glover, Citation2022) and ‘do it for the gram’ (Wang, Citation2017) wherein consumers point to digital platforms (e.g. TikTok, Instagram) as mediators of their consumption choices. Influencers are considered a powerful marketing resource due to their perceived credibility, authenticity and relatability (Abidin, Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2023; Djafarova & Rushworth, Citation2017; Pöyry et al., Citation2019). Marketers have capitalised on the popularity of influencers, turning to them as trusted tastemakers to endorse products and brands to their followers, thereby monetising their following (De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Dinh & Lee, Citation2021). Research shows that influencers shift consumers purchase intentions and drive sales (Ao et al., Citation2023). For instance, in the US, nearly half (44%) of Gen Z consumers report making a purchase based on an influencer’s recommendation, compared to 26% of the broader population (Kantar, Citation2020).

In academic marketing research, the abundance of scholarly work to date centres on practical aspects of influencer marketing: how brands can profit from influencers (Hughes et al., Citation2019; Ki & Kim, Citation2019; Leung et al., Citation2022; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Martínez-López et al., Citation2020; Reinikainen et al., Citation2020), the functional components of influencer marketing (Brooks et al., Citation2021; Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020), roles and categorisations of influencers (Ouvrein et al., Citation2021; Rundin & Colliander, Citation2021), disclosure implications in influencer marketing (Audrezet & Charry, Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2023; De Jans & Hudders, Citation2020; Giuffredi-Kähr et al., Citation2022; Karagür et al., Citation2022), and consumer perceptions of influencers (De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Lee & Eastin, Citation2020; Yuan & Lou, Citation2020). Such research positions influencers as tools in an overall marketing strategy in which variables like source trustworthiness, audience perception, and purchase intention can be measured and manipulated (i.e. antecedents and consequences of influencer marketing, Vrontis et al., Citation2021). But this fails to attenuate for evolutions in the influencer economy, where influencers are not just tools to be deployed but are cultural intermediaries and brands in their own right. For a rich understanding of influencer marketing, we must go beyond attempts to pinpoint a magic mathematic equation for gaining amplification and attention.

Indeed, the commodification and monetisation of private lives raises critical questions about power, privilege, appropriation, and resistance in a content-driven marketplace. That is not to say critical and socio-cultural scholarship on influencer cultures is absent; only that much of it is situated outside of the marketing domain – with media and cultural studies pioneering the exploration of such topics (Khamis et al., Citation2017; Raun, Citation2018; Tufekci, Citation2017). Across this scholarship, examinations of concepts such as labour, authenticity, attention and surveillance dialogue with inequalities and complexities across the influencer industry. These are compounded by the underlying digital dynamics of platforms, algorithms, and affordances (Bishop, Citation2020; Bucher & Helmond, Citation2018; Noble, Citation2018; O’Meara, Citation2019). Accordingly, such approaches to studies of influencer cultures have tended to examine particular interest groups or specific phenomena.

One important focus of this scholarship is the socio-cultural analysis of influencers and their contributions to issues of social justice. For example, indigenous and minority group influencers have been noted for leveraging their visibility on social media, leadership among followers, and ambassadorship with brands to advocate for their communities, tell personal stories and produce counter-hegemonic narratives (Kim, Citation2023; Strangelove, Citation2010). These studies have highlighted the importance of ‘online sisterhood’ (Cabalquinto & Soriano, Citation2020) and networked support during social upheaval and crisis. Another topic of research pertains to examinations of the variations and nuances across situated histories, cultural markets and genre practices, often challenging perceptions of influencer cultures from a monolithic Global North perspective (Song, Citation2018; Zhang & de Seta, Citation2018). This includes the creative strategies employed by influencers to generate attention whilst maintaining intimacies across platforms (Abidin, Citation2021; Lee, Citation2021) as well as the intentional courting of scandal and controversy to sustain interest in an ever-saturated attention economy (Baker, Citation2022; Lewis et al., Citation2021). These issues are examined across a range of marginal online communities, such as queer influencers (Duguay, Citation2019) and child influencers (Pedersen & Aspevig, Citation2018). The implications of the influencer industry for issues of identity, power and resistance have also been explored in relation to gender (Duffy et al., Citation2022; Hurley, Citation2022) and the nuances of tiered classism and racism (Lee & Abidin, Citation2022).

Media and cultural studies scholarship on influencers has also examined the competing pressures of relational maintenance and a commercial agenda, as underscored by emic frameworks of ‘feeling rules’ within the industry (Lehto, Citation2022). This includes mental health and well-being pressures for influencers (Abidin, Citation2019), driven by a need to remain memorable and relevant in the industry (Arriagada & Ibáñez, Citation2020), which can lead to engagement in problematic practices such as peddling lies and hoaxes to followers (Baker & Rojek, Citation2020; Lee & Abidin, Citation2021) with adverse career outcomes. This has driven an interest in researching nuanced and even cynical perspectives of the commercial underpinnings of the influencer industry, considering the proliferation of vernacular indicating degrees of authenticity and sincerity, such as ‘not sponsored’, ‘spon con’, ‘pro bono’, and ‘genuine’ posts. Research in this domain is slowly emerging but will likely be particularly fruitful for future dialogue with marketing scholarship. To date, studies on this topic focus on the ambivalent boundaries between sponsored content and friendly pro-bono shout-outs, such as influencers who overtly signpost ‘not sponsored’ work to stand out for their sincerity in a climate of hyper-commercial content (Abidin, Citation2016); and case studies of influencer philanthropy, such as influencer MrBeast who leverages his visibility and audience engagement to boost his YouTube income and donate to charity (Miller & Hogg, Citation2023).

To wrap up the scope of interdisciplinary studies on influencers, we turn to the two most recent special issues by communication and media studies scholars to examine emerging topics on influencer cultures. First, communication scholars Riedl et al. (Citation2023) turn to the genre of political influencers, which they define as ‘both those who exclusively focus on political or social issues in their social media activities and those who temporarily, or in a more limited manner, promote political or social causes through their accounts’ (Riedl et al., Citation2023, p. 2). They introduce a schema that points to the blurring boundaries between influencers as ordinary citizens and traditional public figures, arguing that influencers partake in a ‘grey area between market and democracy’ (de Gregorio & Goanta, Citation2022, p. 225 in Reidl et al., Citation2023, p. 2) which complicates issues pertaining to commercial regulations. The collection of 8 papers focus on a variety of social media including Silicon Valley platforms (Boichak, Citation2023; Harris et al., Citation2023; Liang & Lu, Citation2023; Nyangulu & Sharra, Citation2023); global platforms (Tang, Citation2023); alternative platforms (Starbird et al., Citation2023); and messaging apps (Sehl & Schützeneder, Citation2023; Stewart et al., Citation2023). The editors offer that while market logics in influencer marketing provide the aspirational promise that ‘anyone can be an influencer’, the reality is that a close examination of platform structures and their power dynamics underscore issues of ‘exclusion and marginalisation similar to other domains of society’ (Reidl et al., 2023, p. 6).

Second, media studies scholars Abidin et al. (Citationin press) focus on the topic of governance and regulation. The collection of 8 papers investigate how influencers may be differently policed by the state (Lee & Abidin, Citation2022; Radics & Abidin, Citation2022); how cultural norms guide decisions in specific markets (Barbetta, Citation2022; Mahy et al., Citation2022); how influencer practices can be subject to rigorous state-based policies (Ju, Citation2022; Xu et al., Citation2022); and how political regimes shape the restrictive media climate within which Influencers operate (Le & Hutchinson, Citation2022; Soriano & Gaw, Citation2022). The socio-cultural and political-economic backdrops of these markets highlight the importance of underscoring context and market frameworks in studies of influencer marketing practices, which are not universalising experiences. Collectively, the editors contend that while recent scholarship has turned attention to the growth of the influencer industry in Asia and platforms outside of Silicon Valley, they argue that the socio-cultural perspective has thus far focused on ‘types of labour’, ‘algorithms and machine learning’, ‘follower relations’, and ‘monetising engagements’ (Abidin et al., Citationin press, p. 1). It is in this vein that this special issue aims to broaden the scope and value of the socio-cultural lens as applied to influencer marketing.

Turning now again to marketing literature – mostly from the vantage point of consumer culture theory scholarship – socio-cultural examinations and critiques of influencer marketing have started to gain traction. Building on research from other fields that have highlighted influencer labour as laborious, precarious and often unpaid (Duffy, Citation2017; Mangan, Citation2020; Terranova, Citation2000), this stream of research has sought to examine the problems and challenges faced by these autobiographical entrepreneurs or ‘autopreneurs’ as they internalise ‘a structure of feeling’ divined from neoliberal ideology (Ashman et al., Citation2018). One key focus has been how influencer marketing is marked by power dynamics and (re)produces structural inequalities, including in relation to gender and sexuality (Drenten et al., Citation2020), religion and race (Pemberton & Takhar, Citation2021), age (McFarlane & Samsioe, Citation2020; Veresiu & Parmentier, Citation2021) and class (Iqani, Citation2019). Research has also considered the implications of influencers’ mediated practices for consumers’ identity projects (Scholz, Citation2021) and consumer collectives (Mardon et al., Citation2023). One important focus across research that examines influencers and issues of identity is the body. This is because the body plays a critical role in the representations that are the end product of influencers’ labour, which are in turn consumed by audiences. Here, the body has been conceived as a site through which social inequalities can be both produced (Viotto et al., Citation2021) and resisted (Södergren & Vallström, Citation2020).

Research in this stream has also sought to problematise and unpack some of the more managerial concepts and assumptions marketing has applied to influencer scholarship. For example, more critical interrogations of authenticity explore the tensions influencers negotiate between maintaining an authentic persona and monetising their social influence. These include how influencers manufacture authenticity (Gannon & Prothero, Citation2016) and negotiate brand encroachment in their lives (Audrezet et al., Citation2020). Beyond how influencers can effectively foster parasocial relationships with audiences to influence brand attitudes and purchase decisions, research has also considered the implications of this work for influencers themselves – including emotional labour (Mardon et al., Citation2018) and sharenting labour (Campana et al., Citation2020) – as well as the potential for influencers to move beyond the entanglements of marketisation (Bradley et al., Citation2023). Finally, instead of celebrating influencer marketing as the ‘next big thing’, research has also sought to examine resistance to influencers and the influencer marketing industry more broadly, for example where citizen-consumers counter influencers’ questionable actions (Ray Chaudhury et al., Citation2021).

Yet, the challenge of marketing and other fields progressing scholarship on influencer marketing without due consideration of each other is a lack of engagement with the concepts and theories being advanced in each space. This risks duplication of effort and reduces possibilities for richer examinations of the phenomena at play. In the spirit of providing a point of dialogue across spaces, in this Editorial we offer below a framework of ‘symbiosis/parasitism’ that speaks to the relations and dynamics that underscore the influencer marketing ecosystem.

The influencer marketing symbiosis/parasitism framework

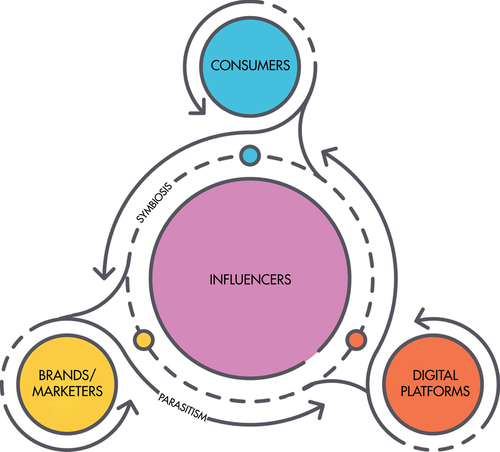

One unique way of looking at the relationship between influencers, marketers and brands, consumers and social media platforms is to consider who is exploiting whom and to what ends. In our framework, we approach this from the perspective of parasitism versus symbiosis. Parasitism is a relationship between two species in which one of them benefits and the other species is harmed. Symbiosis is a close relationship between two species in which usually both gain benefits from each other. Viewing the relationship between influencers, marketers and brands, digital platforms, and consumers through the lens of parasitism versus symbiosis can shed light on the complex relations and dynamics at play. illustrates the influencer marketing symbiosis/parasitism framework, in which dashed lines represent the capacity for symbiosis whereas the solid lines reflect the capacity for parasitism. With influencers at the core, these dynamics operate concurrently with slippages betwixt and between. Influencers, the brands they work with, digital platforms, and consumers are all harmed by one another, as is the case with parasitism, yet they also benefit one another, as is the case with symbiosis.

On one hand, the parasitic aspect is evident when influencers exploit the reach and engagement of social media platforms to gain popularity, build their personal brand, and amass a dedicated following. In this scenario, influencers may benefit from the platform’s features and algorithms to boost their visibility and, consequently, their influence over their audience (Khamis et al., Citation2017). Influencers are dependent and reliant on the platform’s resources (Nieborg & Poell, Citation2018); however, they often do not receive equitable reciprocity in terms of driving user engagement. This relationship could be seen as parasitic in nature, where influencers are exploiting the platforms to achieve their own level of celebrity and reach while platforms are exploiting influencers to drive engagement and advertising revenues. In the midst of this are brands and marketers who are largely responsible for the investment in social media platforms in the form of advertising placement. Influencer marketing, to some extent, circumvents this direct investment in social media platforms, thus leaving platforms to bear the financial costs of sustaining the infrastructure and managing the logistics of content hosting. Moreover, platforms run the risk of suffering negative consequences from influencers’ behaviours, such as the spread of misinformation (Harff et al., Citation2022), controversial content (Drenten et al., Citationin press), or the potential misuse of algorithms for personal gain (O’Meara, Citation2019). Consumers, similarly, can be harmed in this process as their personal data are used as fuel to power influencer marketing algorithms and are subject to privacy concerns. Yet, consumers demonstrate parasitism by extracting value from influencer content (e.g. information, recommendations, product reviews, self-expression) without the burden of direct investment. Brands and marketers can also develop parasitic relationships with influencers whose contractual agreements and compensation for their work can be exploitative (Duffy, Citation2017). In this view, there is distrust and exploitation across the influencer ecosystem. These parasitic aspects tend to speak to the types of issues examined in socio-cultural and critical investigations of influencer marketing, both inside and outside of marketing.

On the other hand, a symbiotic aspect is also prevalent in the influencer ecosystem. Brands and marketers recognise the power of influencers’ genuine connections with their followers (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020). By partnering with influencers, brands can access highly targeted and engaged audiences, which can lead to increased brand awareness, sales, and a boost in credibility. In turn, influencers benefit from collaborations with brands by receiving financial compensation, products, or other perks in addition to enhancing the influencer’s own reputation (Ibáñez-Sánchez et al., Citation2022). Influencer culture often establishes trends and dictates what is considered fashionable or desirable. While this can exert social pressure on consumers to conform, it simultaneously enables consumers to capitalise on such trends to gain social capital and attention of their own. This mutual exchange of value illustrates a symbiotic relationship between influencers, brands and consumers, where all parties derive benefits from each other’s strengths (Carter, Citation2016). Having brands, influencers, and consumers present (and pleased) on a digital platform enables the platform to gain capital, users, and ultimately profit. And platforms in turn operate to support the growth of the ecosystem of influencers and brands online (Cutolo & Kenney, Citation2021). In this view, through the prism of capitalism, they mutually benefit, and all need each other to survive. To ensure the system operates smoothly, policies, guidelines and regulations are promoted to ensure equity and fairness exist, such as disclosures of sponsored content by influencers (Kay et al., Citation2020) and ethical principles guiding the production of sponsored content (Wellman et al., Citation2020). These symbiotic aspects speak to the areas of influencer marketing that more managerial marketing literatures have examined, where the emphasis is on value creation for players in the influencer marketing ecosystem (Vrontis et al., Citation2021).

The relations and dynamics between influencers, brands and marketers, social media digital platforms and consumers are indeed complex and can be analysed through the contrasting perspectives of parasitism and symbiosis. Influencers rely on the platform and brand ‘s resources to grow their influence, while brands leverage influencers’ reach and the affordances of platforms to promote their products. Meanwhile, social media platforms benefit from increased user engagement, but they must also navigate potential issues stemming from influencer and brand activities. Tensions between influencers and brands also exist. Other actors in the influencer ecosystem, such as influencer agencies and consumers, are also subject to these dynamics. By considering the operation of parasitism and symbiosis, we can better understand the multifaceted nature of the influencer ecosystem in today’s digital and social media landscape. Crucially, this also allows us to account for the range of topics and perspectives covered across interdisciplinary research on influencer cultures and marketing.

The special issue papers

Given the growing interest in academic research on influencer marketing, one might ask: what is so special about this special issue? In this issue, we present a collection of 8 groundbreaking, forward-thinking articles focusing on socio-cultural and interdisciplinary perspectives of influencer marketing and influencer cultures. These studies broadly cover three themes: the marketplace of influencing; representation and identity in influencer cultures; and complexities in influencer-audience relationships. Here, we summarise key contributions from each article and tie these works back to the influencer marketing symbiosis/parasitic framework.

The marketplace of influencing

The first set of articles in this special issue showcase the evolution of influencer marketing in research and practice. The past two decades have witnessed a rise in influencer research as a scholarly field, in the practice of influencing as a career, and in influencer marketing as an industry. Research on celebrity studies, advertising endorsements, and digital marketing paved the way for influencer marketing as a scholarly field in its own right. Developments in influencer marketing scholarship have run parallel to advancements in the influencer industry as a marketing practice. Since its inception, influencer marketing has weathered multiple storms to establish itself as a profession. Online influencer content emerged in the late 2000s, at a time when the world’s economic markets were in crisis. What started as a somewhat scrappy, disjointed network of bloggers and vloggers has shifted into a full-fledged industry complete with talent agencies (e.g. INF Influencer Agency), media buying companies (e.g. Omnicom Transact), influencer content development enterprises (e.g. The Influencer Marketing Factory), audience management tools (e.g. Captiv8), dedicated awards (e.g. American Influencer Awards), special events (e.g. VidCon) and more. Influencer marketing strategies have become more sophisticated and dependent on transitions in the landscape of digital platforms (e.g. changes in algorithmic filtering, availability of novel features). These evolutions spotlight how external forces (e.g. economic environments, regulatory institutions) influence the marketplace of influencing and necessitate exploration of the influencer industry from interdisciplinary and sociocultural perspectives – beyond so-called bottom lines and best practices often discussed in marketing literature.

Kendra Fowler and Veronica L. Thomas’s article, ‘Influencer marketing: a scoping review and a look ahead’, adopts a ‘framework-based analysis’ to study a corpus of 150 English-language peer-reviewed articles focused on influencer marketing, published in 71 journals primarily based in the Global North, over a 15-year period. Following a strict set of inclusion/exclusion criteria that prioritised whether each article had explicitly disclosed their ‘theories, contexts, constructs/concepts, and methodological approaches’ and using four journal databases, the authors sought to identify trends in the scholarship, gaps in the literature, and possible directions for further study. The authors introduce a coding schema concentrating on the population, industry, platform, research methods employed, data analysis techniques used, constructs/concepts studied, and theories identified in the corpus. Among their offers, future research should illuminate the collaborative practices that fold in influencers of different standing and status, the dynamics among influencers themselves, and also expand on the wider ‘marketing ecosystem’ comprising influencer partnerships and interactions with brands. On reflection, the authors suggest limitations to their review – including the dominance of a Western perspective that excludes other cultural contexts and platforms, utilising data collection guidelines advocated primarily by Journals in the Global North, the reliance on English language scholarship, and the bias of their scoping framework that prioritises quantitative research – thus providing helpful in-routes for future attempts at scoping the scholarship with different protocols.

Kyle Kubler’s article, ‘Influencers and the attention economy: the meaning and management of attention on Instagram’, deploys in-depth semi-structured interviews with a sample of influencers from the ‘online fitness’ genre who focus on Instagram, and whose influencer personas are engaged in a range of commercialism. Through empirical evidence surfaced from their corpus of interviewees primarily based in the USA, the author argues that as influencers shift from part-time to full-time, or from being in the early to the more established stages of their careers, their strategies similarly transit from being ‘attention-seeking’ to ‘attention-mitigating’. This challenges the adage that ‘all publicity is good publicity’, as experienced influencers have learned to qualify the metrics of attention – such as likes, comments, and followers – in more nuanced ways to ‘alig[n] with their needs’. Specifically, established influencers were beginning to set up their own small businesses, and desired to pivot their advertising efforts away from marketing other brands and towards promoting their own company and wares.

Johan Nilsson, Riikka Murto, and Hans Kjellberg’s article, ‘Influencer marketing and the “gifted” product: framing practices and market shaping’, explores the dynamics of sending ‘stuff’, or gifts, to influencers, and how such ‘stuff’ is regulated from a taxation and compensation perspective. By studying the Swedish Tax Agency and the Swedish influencer market, their study maps different ways in which involved actors frame the circulation of ‘stuff’. From a PR perspective, ‘stuff’ is sent to earn media attention, while from a marketing perspective, it may be framed as compensation for services rendered. Their work points to how the professionalisation and formalisation of the influencer industry has introduced new regulatory challenges and friction in how market exchange takes place between companies, influencers, and third-party intermediaries. The authors use Callon’s lens of framing to propose ways (e.g. framing, reframing, and preframing) in which ‘stuff’ sent to influencers is contextualised to organise the market and tackle the bigger issue of payment in the influencer industry.

Indeed, the influencer industry has grown in complexity, comprising more and more actors who each have different objectives, strategies and standpoints. As our framework of symbiosis and parasitism highlights, whilst one actor may benefit, another may be harmed - and vice versa. All are subject to the whims of the influencer marketing industry, including the platforms that host them. For whilst influencers continue to rise in status in the attention economy as celebrities and entrepreneurs - with influencing now a legitimate career - this comes at the cost of greater regulatory scrutiny and heightened corporate expectations. Influencers increasingly generate revenue through creating their own merchandise lines, their own exclusive meet-and-greet opportunities, and their own paywalled content; thus aiming to shift their audience away from traditional social media platforms. For example, in 2016, popular male beauty influencer James Charles became the first CoverBoy for CoverGirl in the company's 58-year history. His fame was later leveraged to launch a co-branded mini makeup-palette in partnership with Ulta Beauty and Morphe, and in 2023, he introduced his own makeup brand, Painted. Yet, the evolution of his career has been peppered with controversies, scandals, and dramas including public feuds with fellow influencers, accusations of sexual grooming, and alleged violations of regulatory advertising standards.Footnote1 Similarly, after a group of influencers were invited to tour the factories of controversy plagued e-retailer Shein, they received swift backlash and accusations of promoting propaganda.Footnote2 The brand - which has been accused of labour law violations and negative environmental impacts - was revealed to have signed partnership deals with the influencers prior to the trip.Footnote3 This led to public denouncements the influencers had “sold out”,Footnote4 highlighting the increasing role of ethics and responsibility across the influencer ecosystem. This points to both the increasing complexity of the influencer industry and how all actors work within the confines of ever-changing regulatory boundaries and cultural trends, whilst also actively shifting them. This complexity is heightened as influencers begin to wade into more controversial spaces where traditional marketing efforts have stalled, such as gambling, Big Pharma and cryptocurrencies. Who is harmed and who benefits are crucial questions to ask, especially in such contexts.

Representation and identity in influencer cultures

The next set of articles in this special issue addresses representation and the complexities of identity in influencer culture. Indeed, influencer marketing has undergone a substantial transformation from its initial focus on lifestyle domains like fashion, beauty, travel, and culinary pursuits. Today, virtually every niche community and distinctive subculture boasts a cadre of influencers – pet influencers, climate influencers, gun influencers, transgender influencers, book influencers, education influencers, kid influencers, and more. As the influencer landscape evolves, influencers face both opportunities and challenges in representing their identities online. Underrepresented and historically excluded voices can challenge stereotypes, break down barriers, and create a more inclusive online space, but they may also face compounded issues of criticism, harassment, and backlash. This shift merits research into issues of representation in influencer marketing. Who attains the mantle of an influencer; what attributes transcend traditional categorisations; how are the complexities of identity portrayed through influencer culture; and how do so-called ‘nontraditional influencers’ connect with audiences and disseminate their perspectives in unique ways?

Jonatan Södergren and Niklas Vallström’s article, ‘Disability in influencer marketing: a complex model of disability representation’, explores how social media influencers with disabilities draw upon unique self-presentation strategies to present themselves as neither victims nor superhuman agents but as complex human beings. Through a lens of ‘complex personhood’, their work pushes our understanding of market-mediated representations of disability, beyond narratives based on pity and ‘inspiration porn’. The authors suggest social media influencers with disabilities should set the terms for how they are represented in advertising, rather than marketers, who have historically failed to produce multifaceted portrayals of disability in advertising. The authors extend existing influencer marketing literature by highlighting how influencer content can challenge stereotypes and raise awareness of disability-related issues.

Aya Aboelenien, Alex Baudet, and Ai Ming Chow’s article, ‘“You need to change how you consume”: ethical influencers, their audiences and their linking strategies’, examines the role of ethical social media influencers in promoting consumption-driven social change. Their study of vegan and zero-waste Instagram influencers offers a conceptual typology of ethical influencers and highlights their positive social impact, countering criticisms of so-called ‘traditional’ influencers. The authors identify unique linking strategies used by ethical influencers to connect audiences with other actors for driving consumption-related change. Their work highlights the important emerging role of ‘ethical influencers’ as agents of change, driving positive action and creating a ripple effect that encourages consumers, businesses, and policymakers to prioritise ethical practices. This is particularly relevant given the increasing importance of social change issues such as human rights, healthcare access, gender equity, sustainability and climate conservation, mental health, and racial justice – domains in which ethical influencers have the potential to create positive and lasting transformations in society.

These works point to an urgency for examining influencers that operate beyond traditional ‘lifestyle’ categories (e.g. travel influencer, food influencer, fashion influencer) to capture the complexities of identity across influencer culture. When viewed through the lens of our framework, these articles point to a need to more deeply explore when representation is agentic versus exploitative. In particular, historically marginalised and excluded communities have found a foothold in digital culture and representation of such individuals has now trickled into traditional advertising efforts. For example, parallel to the increase in influencer marketing and content, we have a seen a rise in inclusive talent agencies, such as Zeebeedee, which is devoted to individuals with disabilities, and a rise in representation of disabilities in advertising campaigns, such as the Rollettes, a wheelchair dance troupe whose members have partnered with Aerie, Target, Reebok, Wells Fargo, Clorox, and other brands. Whilst this greater diversity of representation is crucial to advance equality more generally, the capitalist motivation that underscores these representational practices reveals where this can fall apart. For example, Bud Light’s 2023 digital marketing campaign featuring transgender TikToker Dylan Mulvaney illustrates how brands can quickly and ruthlessly abandon influencers driving social change efforts through the marketplace when they attract divided public opinion.Footnote5 The complexities of identity in influencer culture underline how quickly relations between different actors in the influencer ecosystem can shift from agentic and beneficial to exploitative and harmful – and back again.

Complexities in influencer-audience relations

The final set of papers in the special issue explore the complex socio-cultural relations between influencers and their audiences. Moving beyond a focus on how audience relations are dependent on perceptions of authenticity, trustworthiness and relatability and how these influence purchase intentions, research on influencers has begun to delve deeper into the complex parasocial relations between influencers and followers. Indeed, both audiences and influencers have comprehensive and intimate understandings of one another – influencers offer audiences a view into their personal lives whilst knowledge of their audiences built through platform-generated insights are central to the success of the influencer. This speaks to both the symbiotic and parasitic potentials across these relations. In the influencer landscape, instances abound of the ways in which these relations continue to deepen and evolve. For example, as influencers continuously seek out novel ways to engage and build their audiences, new platform offerings such as the rise of subscription-based services offer ways for influencers to create more personalised content and services for subscribers – in exchange for a monthly fee – whilst becoming less reliant on brand collaborations. Audiences on the other hand continue to shift how they consume influencer marketing, with heightened scepticism towards influencer sponsored content driving the growing popularity of less polished nano- and micro-influencers as consumers turn their backs on glamorous and highly curated mega-influencers. These changes open up important conversations about the arising complexities of the relations and intimacies between audiences and influencers, which the final three papers in our special issue grapple with.

Amy Goode, Victoria Rodner, and Matilda Lawlor’s article, ‘Beyond the Authenticity Bind – Finstagram as an escape from the attention economy’, examines the influencer culture trend of ‘finstagramming’, whereby influencers create fake Instagram accounts to escape the algorithmic confines and prescribed aesthetics of the platform Instagram. These accounts enable influencers to share intimate and unpolished content without jeopardising their curated monetised account. The authors identify embedded escapism as a paradox that defines how influencers toggle between their main and Finsta accounts as they navigate the pressures of authenticity through an emancipatory yet platform-bound outlet. Their work highlights a resistance strategy adopted by influencers in grappling with the demands of the attention economy that enables the cultivation of differentiated online identities through multi-account affordances yet allows influencers to remain embedded in the dynamics of the platform. Additionally, they critically examine notions of authenticity, both exploring how influencers craft tales of authenticity in the aesthetic and emotional labour they perform whilst simultaneously leveraging their authenticity across different accounts. The authors highlight a porosity of authenticity which bleeds across influencers’ different digital personae, as enabled through secondary accounts. They position this as a means for influencers to escape and move beyond the ‘authenticity bind’ of being ‘real enough’ but not ‘too real’ in navigating the pressures and complexities of relations with their audiences.

Nataly Levesque, Alysha Hachey and Albena Pergelova’s article, ‘No filter: navigating well-being in troubled times as social media influencers’, further unpacks this tension of how much should and can influencers reveal of themselves with audiences by delving into the issue of influencers’ sense of self. Specifically, the authors explore how the pressure to balance monetising their following and expressing their identity can impact influencers’ well-being – especially as they engage with more controversial issues during troubled times, where interactions with followers can be polarising. Using the COVID-19 pandemic as a context, the authors explore how the decision to engage with the topic of COVID-19 on social media impacted influencers’ well-being. Their research contends that thwarted feelings of autonomy and authenticity-positivity tensions generate self-presentation tensions that can inhibit people’s integrated sense of self and well-being. However, self-presentation solutions arise from fostering relatedness and negotiating competence, which can help influencers deal with these tensions and provide pathways to a more unified sense self which enhances well-being. Their paper brings attention to what underscores and destabilises influencer well-being, an important contribution as influencers rise in status and power in the attention economy. This can enrich both influencers’ own understandings of how they negotiate their work and how marketers should embed understandings of care in partnerships with ‘human brands’.

Finally, Rebecca Mardon, Hayley Cocker and Kate Daunt’s article, ‘When parasocial relationships turn sour: social media influencers, eroded and exploitative intimacies, and anti-fan communities’, explores the phenomenon of social media influencer-focused anti-fan communities. Through an investigation of how fans of social media influencers can become critics, the authors unpack how positive parasocial relationships may subsequently become negatively charged – to the point of fuelling participation in anti-fan communities. This highlights the agency of audiences and the power they can wield if they turn on the influencer they once idealised. The authors reveal that the erosion of reciprocal and disclosive intimacies, as well as the perception of exploitative commercial intimacies, can shift consumers’ parasocial relationships with influencers from positive to negative, turning fans into anti-fans. Moreover, they identify that anti-fan communities provide opportunities for consumers to sustain negative parasocial relationships with influencers. Their work highlights the variance and shifts in consumers’ parasocial relationships with influencers and the role of anti-fan communities in this evolution. Importantly, their research signals that influencers must avoid the erosion or perceived exploitation of intimacies with followers and the importance of liberally moderating social media comments by viewers to mitigate this.

The papers in this set point to the precarity of influencer-audience relations and the importance of unpacking these dynamics in ways that do not assume simplistic capitalistic benefits gained from each other. Indeed, these papers highlight that things can fall apart between influencers and audiences, whereby the intimacies fostered can quickly turn awry. When considered through our framework, these complex relations point to the potential for both symbiosis and parasitism. For example, in 2023, after popular beauty influencer Mikayla Nogueira was called out for using fake eyelashes in a product review for L’Oreal, fans started questioning her integrity and growing scepticism arose about her online persona.Footnote6 This had catastrophic impacts on her career as an influencer. Yet, the same fans who outed/investigated the controversy surrounding ‘LashGate’ ironically quickly gained followers in their own right, thus launching their own influencer platforms on the rubble of another influencer’s fall from grace. This exemplifies the blurred line between how we categorise ‘influencers’ and ‘audiences’, as they are increasingly one and the same. Moreover, volatility pervades how each informs the other. As a consequence, audiences and influencers both work to (re)claim their spaces within digital cultures, which can be both liberating and oppressive. Given that influencers are – ostensibly – monetising their audiences, it is tempting to underestimate the power that audiences have over influencers. Yet, in this human brand scenario, audiences can impact influencers’ well-being, cannibalise and hijack influencer content, and colonise their personal spaces. As both are increasingly platform dependent, finding emancipatory spaces can be challenging. Fuelling this, the influencer ecosystem is marked by constant questions about who is exploiting whom and to what ends.

Where do we go from here?

Influencer marketing, as both a practice and a scholarly research context, is dynamic and rapidly evolving. Studying influencer marketing from a socio-cultural perspective offers valuable insights that go beyond the surface-level understanding of marketing strategies and consumer behaviour. As we delve into the future potentialities in this domain, it is essential to consider three key directions that can shape the trajectory of scholarship and provide valuable insights into the intricate relationship between influencers, culture, and marketing practice.

Interdisciplinary integration and collaborative engagement

The first avenue for future research highlights the growing imperative for scholars to transcend the boundaries of their respective disciplines and actively engage in interdisciplinary collaboration. We recognise the many inherent challenges in conducting truly interdisciplinary influencer research. For instance, academic institutions and funding agencies are often organised around disciplinary silos, making it difficult to secure resources and recognition for interdisciplinary work. Different disciplines often have their own terminology, methodologies, and paradigms. Yet, bridging gaps between disciplines encourages critical evaluation and a richer peer-review process. This panoply of voices will only enhance the continued development of influencer marketing and influencer cultures research. Interdisciplinary influencer research can improve the rigour of our scholarship by identifying potential biases or myopic interests that might arise only through the prism of a single discipline. Beyond merely citing each other’s work, genuine collaboration should encompass interactions at both theoretical and practical levels. This entails fostering partnerships across disciplines such as cultural studies, communications, sociology, psychology, marketing, and others.

For instance, a collaboration between scholars specialising in communication studies, cultural anthropology, and marketing might explore the cultural implications of influencer discourses and practices as they are tethered to monetisation and the marketplace. As our framework suggests, these dynamics can be simultaneously exploitative and beneficial for actors involved. By pooling their expertise, scholars could conduct a comprehensive analysis of how influencers navigate cultural nuances while promoting products or ideas that ultimately monetise communities of consumers. Such interdisciplinary collaborations could extend to joint research projects, co-authored papers, and even jointly organised conferences. Moreover, practitioners and influencers themselves can contribute to this dialogue by sharing their real-world experiences and challenges, leading to a richer and more nuanced understanding of influencer dynamics.

Embracing complexity and messiness in influencer culture research

The second avenue for future research involves a departure from traditional linear research to embrace the complexities and messiness inherent in influencer culture. Scholars must recognise that the landscape of influencer marketing is far from straightforward, and a deep dive into the intricacies of content creation, audience engagement, and evolving trends is necessary. As our framework demonstrates, the influencer ecosystem is marked by complex relations that cannot be taken for granted as static or productive.

For instance, consider the tensions between an influencer’s personal brand and the sponsored content they promote. Research examining this could involve qualitative analyses of influencer narratives, revealing how they navigate the delicate balance between authenticity, commercial interests and audience engagement and/or cynicism. By embracing the messiness of contradictory motives and complex negotiation processes, scholars can uncover the nuanced strategies influencers employ to connect with their audiences while simultaneously satisfying brand partnerships and adhering to increasing regulatory scrutiny. These dynamics speak to so much more than simply brand profitability and consumer purchase intentions, as influencer marketing evolves from a marketing tactic to a cultural phenomenon.

Tethering socio-cultural dynamics to marketing practice

The third avenue for future research is developing a robust understanding of the socio-cultural dynamics intertwined with influencer marketing practice. This direction necessitates investigations beyond just marketing outcomes and industry best practices. Scholars must examine the intricate interplay between influencers, culture, and society to shed light on broader societal trends, power dynamics, and the evolving nature of communication. This speaks to the tensions and paradoxical dynamics that underscore the influencer marketing ecosystem, as represented in our framework.

For instance, researchers could delve into the emergence and evolution of nontraditional influencers, such as micro-influencers from marginalised communities, highlighting their unique role in (re)shaping cultural narratives. Additionally, research should not be limited to individual influencers. Research on influencer collectives could uncover how these groups collaborate, compete, and influence consumer culture collectively. Lastly, examining the influencer marketing industry itself as a business entity offers opportunities to scrutinise its power structures, ethical challenges, and evolving strategies and the impacts of these on the marketplace and society at large.

Concluding thoughts

In sum, the future of influencer marketing research from interdisciplinary and socio-cultural perspectives is promising, with the potential to yield groundbreaking insights. By fostering collaboration across fields, embracing complexity, and dissecting socio-cultural dynamics, scholars can unravel the intricate tapestry that connects influencers, consumers, the marketplace and culture. This exploration will not only enrich academic discourse but also inform industry practices and empower influencers and their followers to navigate this ever-evolving landscape with deeper insights and critical acumen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

References

- Abidin, C. (2015). Communicative intimacies: Influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media & Technology, 8. https://doi.org/10.7264/N3MW2FFG

- Abidin, C. (2016). “Aren’t these just young, rich women doing vain things online?”: Influencer selfies as subversive frivolity. Social Media + Society, 2(2), 205630511664134. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116641342

- Abidin, C. (2019). Victim, rival, bully: influencers’ narrative cultures around cyberbullying. In H. Vandebosch & L. Green (Eds.), Narratives in research and interventions on cyberbullying among young people (pp. 199–212). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04960-7_13

- Abidin, C. (2021). From “networked publics” to “refracted publics”: A companion framework for researching “below the radar” studies. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 2056305120984458. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984458

- Abidin, C., & Shen, S. (in press). The future of Wanghong. Global Media & China.

- Abidin, C., Xu, J., & Hutchinson, J. (in press). Influencer regulations, governance and sociocultural issues in Asia. Policy & Internet. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.340

- Ao, L., Bansal, R., Pruthi, N., & Khaskheli, M. B. (2023). Impact of social media influencers on customer engagement and purchase intention: A meta-analysis. Sustainability, 15(3), 2744. Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032744

- Arriagada, A., & Ibáñez, F. (2020). “You need at least one picture daily, if not, you’re dead”: Content creators and platform evolution in the social media ecology. Social Media + Society, 6(3), 205630512094462. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120944624

- Ashman, R., Patterson, A., & Brown, S. (2018). ‘Don’t forget to like, share and subscribe’: Digital autopreneurs in a neoliberal world. Journal of Business Research, 92, 474–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.055

- Audrezet, A., & Charry, K. (2019, August 29). Do influencers need to tell audiences they’re getting paid? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/08/do-influencers-need-to-tell-audiences-theyre-getting-paid

- Audrezet, A., de Kerviler, G., & Guidry Moulard, J. (2020). Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research, 117, 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.008

- Baker, S. A. (2022). Alt. Health influencers: How wellness culture and web culture have been weaponised to promote conspiracy theories and far-right extremism during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211062623

- Baker, S. A., & Rojek, C. (2020). The Belle Gibson scandal: The rise of lifestyle gurus as micro-celebrities in low-trust societies. Journal of Sociology, 56(3), 388–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319846188

- Barbetta, T. (2022). Ghosts of YouTube: Rules and conventions in Japanese YouTube content creation outsourcing. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.323

- Bishop, S. (2020). Algorithmic experts: Selling algorithmic lore on YouTube. Social Media + Society, 6(1), 2056305119897323. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119897323

- Boichak, O. (2023). Mapping the Russian political influence ecosystem: The night wolves biker gang. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177920

- Borchers, N. S. (2019). Social media influencers in strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(4), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1634075

- Bradley, T., Anderson, K. C., & Hass, A. (2023). The virtuous cycle: Social media influencers’ potential for kindness contagion. Journal of Macromarketing, 43(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/02761467231163754

- Brooks, G., Drenten, J., & Piskorski, M. J. (2021). Influencer celebrification: How social media influencers acquire celebrity capital. Journal of Advertising, 50(5), 528–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1977737

- Bucher, T., & Helmond, A. (2018). The affordances of social media platforms. In The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 233–253). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473984066.n14

- Cabalquinto, E. C., & Soriano, C. R. R. (2020). ‘Hey, I like ur videos. Super relate!’ Locating sisterhood in a postcolonial intimate public on YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 23(6), 892–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1751864

- Campana, M., Van den Bossche, A., & Miller, B. (2020). #dadtribe: Performing sharenting labour to commercialise involved fatherhood. Journal of Macromarketing, 40(4), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146720933334

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003

- Carter, D. (2016). Hustle and brand: The sociotechnical shaping of influence. Social Media + Society, 2(3), 205630511666630. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116666305

- Cheah Shenzhen, C. W., Cheah, J.-H., Gretzel, U., Yeik Koay, K., & Xiang, K. (in press). Human and virtual influencer marketing in hospitality and tourism. https://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-hospitality-and-tourism-management/call-for-papers/journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-hospitality-and-tourism-management/call-for-papers/undefined

- Chen, L., Yan, Y., & Smith, A. N. (2023). What drives digital engagement with sponsored videos? An investigation of video influencers’ authenticity management strategies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51(1), 198–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-022-00887-2

- Cutolo, D., & Kenney, M. (2021). Platform-dependent entrepreneurs: Power asymmetries, risks, and strategies in the platform economy. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(4), 584–605. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2019.0103

- de Gregorio, G., & Goanta, C. (2022). The influencer republic: Monetizing political speech on social media. German Law Journal, 23(2), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2022.15

- De Jans, S., & Hudders, L. (2020). Disclosure of vlog advertising targeted to children. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 52(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.03.003

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035

- Dinh, T. C. T., & Lee, Y. (2021). “I want to be as trendy as influencers” – How “fear of missing out” leads to buying intention for products endorsed by social media influencers. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(3), 346–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-04-2021-0127

- Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

- Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., Duff, A., & Barnhart, M. (in press). Curating a consumption ideology: Platformization and gun influencers on Instagram. Marketing Theory.

- Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2020). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12354

- Duffy, B. E. (2017). (Not) getting paid to do what you love. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/9780300264753/not-getting-paid-to-do-what-you-love

- Duffy, B. E., & Hund, E. (2019). Gendered visibility on social media: Navigating Instagram’s authenticity bind. International Journal of Communication, 13. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11729

- Duffy, B. E., Miltner, K. M., & Wahlstedt, A. (2022). Policing “fake” femininity: Authenticity, accountability, and influencer antifandom. New Media & Society, 24(7), 1657–1676. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221099234

- Duguay, S. (2019). “Running the numbers”: Modes of microcelebrity labor in queer women’s self-representation on Instagram and vine. Social Media + Society, 5(4), 205630511989400. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119894002

- Gannon, V., & Prothero, A. (2016). Beauty blogger selfies as authenticating practices. European Journal of Marketing, 50(9/10), 1858–1878. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-07-2015-0510

- Gerrath, M., Olya, H., Shah, Z., Ja Kim, M., & Kam Fung So, K. (in press). Psychology & marketing - call for papers: Special issue on influencer marketing for the greater good: How to encourage sustainable and prosocial behavior. Psychology & Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6793

- Geyser, W. (2022, January 24). The state of influencer marketing 2023: Benchmark report. Influencer Marketing Hub. https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/

- Giuffredi-Kähr, A., Petrova, A., & Malär, L. (2022). Sponsorship disclosure of influencers – A curse or a blessing? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 57(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/10949968221075686

- Glover, E. (2022, December 13). ‘TikTok made me buy it’ is only the beginning. https://builtin.com/consumer-tech/social-commerce

- Harff, D., Bollen, C., & Schmuck, D. (2022). Responses to social media influencers’ misinformation about COVID-19: A pre-registered multiple-exposure experiment. Media Psychology, 25(6), 831–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2080711

- Harris, B. C., Foxman, M., & Partin, W. C. (2023). “Don’t make me ratio you again”: How political influencers encourage platformed political participation. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177944

- Hudders, L., & Lou, C. (2022). A new era of influencer marketing: Lessons from recent inquires and thoughts on future directions. International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2022.2031729

- Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919854374

- Hund, E. (2023). The Influencer Industry: The Quest for Authenticity on Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691234076

- Hurley, Z. (2022). Middle Eastern women influencers’ interdependent/independent subjectification on Tiktok: Feminist postdigital transnational inquiry. Information, Communication & Society, 25(6), 734–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2044500

- Ibáñez-Sánchez, S., Flavián, M., Casaló, L. V., & Belanche, D. (2022). Influencers and brands successful collaborations: A mutual reinforcement to promote products and services on social media. Journal of Marketing Communications, 28(5), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2021.1929410

- Iqani, M. (2019). Picturing luxury, producing value: The cultural labour of social media brand influencers in South Africa. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877918821237

- Ju, R. (2022). Producing entrepreneurial citizens: Governmentality over and through Hong Kong influencers on Xiaohongshu (Red). Policy & Internet, 14(3), 618–632. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.324

- Kantar. (2020, September 10). Building brands with Gen Z: New Kantar research on Gen Z’s brand preferences. https://forbusiness.snapchat.com/blog/building-brands-with-gen-z-kantar

- Karagür, Z., Becker, J.-M., Klein, K., & Edeling, A. (2022). How, why, and when disclosure type matters for influencer marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 39(2), 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.09.006

- Karhawi, I., & Amalia Dalpizol Valiati, V. (in press). Digital influencers and creative industries. Brazilian Creative Industries Journal. https://periodicos.feevale.br/seer/index.php/braziliancreativeindustries/announcement/view/28

- Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., & Parkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: The impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3–4), 248–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1718740

- Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of social media influencers. Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

- Ki, C.-W., & Kim, Y.-K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing, 36(10), 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21244

- Kim, D. (2023). Racialized beauty, visibility, and empowerment: Asian American women influencers on YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 26(6), 1159–1176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1994626

- Koles, B., Audrezet, A., Ameen, N., Mckenna, B., & Guidry Moulard, J. (in press). Virtual influencers: A new frontier in interdisciplinary research. Journal of Business Research. https://www.ukais.org/event/virtual-influencers-a-new-frontier-in-interdisciplinary-research/

- Lee, J. (2021). “I don’t understand what you’re saying now, but you are cute, I love you”: Global communication between South Korean gay male YouTubers and fans from overseas. Feminist Media Studies, 21(6), 1044–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1959372

- Lee, J., & Abidin, C. (2021). Backdoor advertising scandals, Yingyeo culture, and cancel culture among YouTube influencers in South Korea. New Media & Society, 14614448211061828. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211061829

- Lee, J., & Abidin, C. (2022). Oegugin influencers and pop nationalism through government campaigns: Regulating foreign-nationals in the South Korean YouTube ecology. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.319

- Lee, J. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2020). I like what she’s #Endorsing: The impact of female social media influencers’ perceived sincerity, consumer envy, and product type. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 20(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2020.1737849

- Lehto, M. (2022). Ambivalent influencers: Feeling rules and the affective practice of anxiety in social media influencer work. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(1), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549421988958

- Le, V. T., & Hutchinson, J. (2022). Regulating social media and influencers within Vietnam. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 558–573. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.325

- Leung, F. F., Gu, F. F., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Online influencer marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(2), 226–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00829-4

- Lewis, R., Marwick, A. E., & Partin, W. C. (2021). “We dissect stupidity and respond to it”: Response videos and networked harassment on YouTube. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(5), 735–756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221989781

- Liang, F., & Lu, S. (2023). The dynamics of event-based political influencers on Twitter: A longitudinal analysis of influential accounts during Chinese political Events. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177946

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Mahy, P., Winarnita, M., & Herriman, N. (2022). Influencing the influencers: Regulating the morality of online conduct in Indonesia. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 574–596. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.321

- Mangan, D. (2020). Influencer marketing as labour: Between the public and private divide. In The regulation of social media influencers (pp. 185–208). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/display/edcoll/9781788978279/9781788978279.00017.xml

- Mardon, R., Cocker, H., & Daunt, K. (2023). How social media influencers impact consumer collectives: An embeddedness perspective. The Journal of Consumer Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucad003

- Mardon, R., Cocker, H., Daunt, K., & Kozinets, R. (in press). Influencers & influencer marketing: Implications for consumers & Society. Journal of Business Research. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-business-research/about/call-for-papers#influencers-influencer-marketing-implications-for-consumers-society

- Mardon, R., Molesworth, M., & Grigore, G. (2018). YouTube beauty Gurus and the emotional labour of tribal entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 92, 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.017

- Martínez-López, F. J., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Fernández Giordano, M., & Lopez-Lopez, D. (2020). Behind influencer marketing: Key marketing decisions and their effects on followers’ responses. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(7–8), 579–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1738525

- McFarlane, A., & Samsioe, E. (2020). #50+ fashion Instagram influencers: Cognitive age and aesthetic digital labours. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 24(3), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-08-2019-0177

- McQuarrie, E. F., Miller, J., & Phillips, B. J. (2013). The megaphone effect: Taste and audience in fashion blogging. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1), 136–158. https://doi.org/10.1086/669042

- Miller, V., & Hogg, E. (2023). ‘If you press this, I’ll pay’: MrBeast, YouTube, and the mobilisation of the audience commodity in the name of charity. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 29(4), 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231161810

- Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4275–4292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression. NYU Press.

- Nyangulu, D., & Sharra, A. (2023). Agency and incentives of diasporic political influencers on Facebook Malawi. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177936

- O’Meara, V. (2019). Weapons of the Chic: Instagram influencer engagement pods as practices of resistance to Instagram platform labor. Social Media + Society, 5(4), 205630511987967. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119879671

- Ouvrein, G., Pabian, S., Giles, D., Hudders, L., & De Backer, C. (2021). The web of influencers. A marketing-audience classification of (potential) social media influencers. Journal of Marketing Management, 37(13–14), 1313–1342. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1912142

- Pedersen, I., & Aspevig, K. (2018). Being Jacob: Young children, automedial subjectivity, and child social media influencers. M/C Journal, 21(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1352

- Pemberton, K., & Takhar, J. (2021). A critical technocultural discourse analysis of Muslim fashion bloggers in France: Charting ‘restorative technoscapes’. Journal of Marketing Management, 37(5–6), 387–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1868551

- Pöyry, E., Pelkonen, M., Naumanen, E., & Laaksonen, S.-M. (2019). A call for authenticity: Audience responses to social media influencer endorsements in strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(4), 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1609965

- Radics, G., & Abidin, C. (2022). Racial harmony and sexual violence: Uneven regulation and legal protection gaps for influencers in Singapore. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.320

- Raun, T. (2018). Capitalizing intimacy: New subcultural forms of micro-celebrity strategies and affective labour on YouTube. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 24(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736983

- Ray Chaudhury, S., Nafees, L., & Perera, B. Y. (2021). “For the gram”: An exploration of the conflict between influencers and citizen-consumers in the public lands marketing system. Journal of Macromarketing, 41(4), 570–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146720956380

- Reinikainen, H., Munnukka, J., Maity, D., & Luoma-Aho, V. (2020). ‘You really are a great big sister’ – Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3–4), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1708781

- Riedl, M. J., Lukito, J., & Woolley, S. C. (2023). Political influencers on social media: An introduction. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177938

- Rosengren, S., & Campbell, C. (2021). Navigating the future of influencer advertising: Consolidating what is known and identifying new research directions. Journal of Advertising, 50(5), 505–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1984346

- Rundin, K., & Colliander, J. (2021). Multifaceted influencers: Toward a new typology for influencer roles in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 50(5), 548–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1980471

- Scholz, J. (2021). How consumers consume social media influence. Journal of Advertising, 50(5), 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1980472

- Sehl, A., & Schützeneder, J. (2023). Political knowledge to go: An analysis of selected political influencers and their formats in the context of the 2021 German federal election. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177916

- Södergren, J., & Vallström, N. (2020). One-armed bandit? An intersectional analysis of Kelly Knox and disabled bodies in influencer marketing. ACR North American Advances, NA-48. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/2664299/volumes/v48/NA-48

- Song, H. (2018). The making of microcelebrity: AfreecaTV and the younger generation in neoliberal South Korea. Social Media + Society, 4(4), 205630511881490. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118814906

- Soriano, C. R. R., & Gaw, M. F. (2022). Broadcasting anti-media populism in the Philippines: YouTube influencers, networked political brokerage, and implications for governance. Policy & Internet, 14(3), 508–524. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.322

- Starbird, K., DiResta, R., & DeButts, M. (2023). Influence and improvisation: Participatory disinformation during the 2020 US election. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177943

- Stewart, N. K., Al-Rawi, A., Celestini, C., & Worku, N. (2023). Hate influencers’ mediation of hate on telegram: “We declare war against the anti-white system”. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177915

- Strangelove, M. (2010). Watching YouTube: Extraordinary videos by ordinary people. University of Toronto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt2tv1kq

- Tang, J. L. (2023). Issue communication network dynamics in connective action: The role of non-political influencers and regular users. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 205630512311779. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177921

- Terranova, T. (2000). Free labor: Producing culture for the digital economy. Social Text, 18(2), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-18-2_63-33

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press.

- Turner, G. (2010). Ordinary people and the media: The demotic turn. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446269565

- Veresiu, E., & Parmentier, M.-A. (2021). Advanced style influencers: Confronting gendered ageism in fashion and beauty markets. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 6(2), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1086/712609