ABSTRACT

Our study examines ‘Finstagramming’ as a resistance strategy from influencers trying to circumvent the prescriptive nature and restrictive algorithm of Instagram. Without ever leaving the platform, Finstagram acts as an emancipatory outlet that enables influencers to share more intimate, less-conforming and unpolished content without jeopardising the highly curated, monetizable person-brand of their main account. Through a dual-method qualitative approach of netnography and in-depth interviews, we unravel this paradox of embedded escapism, where influencers toggle between main and Finsta accounts in their pursuit of authenticity. Our findings reveal the porosity of these multiple digital personae and differentiated digital work taking place on the platform. We argue that Finstagram affords a momentary escape from the digital attention economy whilst remaining tethered to socially mediated authenticity markers.

Honestly, I don’t know why, exactly, I find the existence of this particular finsta so fascinating.

Perhaps it’s just the thrill of imagining that any rando follower request could actually be one

of the most famous singers in the world.

Or perhaps that Adele is as interested in cats and interior design as the rest of us.

Or perhaps it’s far more simple than even that.

Perhaps it’s just knowing that Adele – she’s just like us.

(Watercutter, Citation2021)

Introduction

Like other celebrities, singer-songwriter Adele admits to keeping a fake Instagram (or ‘Finsta’) as well as a fake Twitter account, the former reserved for interior decorating and cat content, the latter used to stealthily follow online gossip about her life. Whereas her official, verified accounts focus on highly visible promotional material about her musical career, Adele’s fake social media profiles attempt to ‘keep the mess where it belongs: off main’ (Watercutter, Citation2021).

Heralded as a ‘chance to be real’, Finstagram (i.e. ‘fake’ Instagram), is believed to free celebrities (Safronova, Citation2015), teens (Parham, Citation2018) and everyday influencers (Kang & Wei, Citation2020) from the performativity (Abidin, Citation2018b), prescribed aesthetics (Reade, Citation2021) and algorithmic strictures (Cotter, Citation2019) of the image-based platform, allowing for ‘truer’, unencumbered versions of themselves to emerge (Kang & Wei, Citation2020). Seemingly more candid, or at least less ‘plandid’ (Drenten et al., Citation2020), than their counterpart main accounts, these secondary profiles are also less in the limelight (and potentially scrutinising gaze) of a social other (Elias & Gill, Citation2018). Reserved for the most part for the select few allowed ‘in’, these accounts are generally less visible, frequently hiding under inconspicuous pseudonyms or doppelgänger handles that disguise provenanceFootnote1 (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019). As such, Finstagram encourages users to ‘share more personal content with a select group of friends’ (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019, p. 131), presenting themselves in a seemingly more genuine manner to a more exclusive, discerning audience. Seeking quality over quantity of attention (Marwick, Citation2015), Instagrammers toggle between their main and Finsta accounts to share more unique, creative or even playful content to smaller and more intimate audiences on their secondary profiles whilst retaining and nourishing their monetizable personal brand on their primary account (Haenlein et al., Citation2020). Compared to mainstream Instagram, these ‘fake’ profiles act as temporary safe havens for users from the ‘stringent media ideologies’ (Ross, Citation2019, p. 368) of more visible, highly commercialised social networking sites which can feel like less genuine presentations of the self. Rather than being ‘fake’, Finsta accounts appear more real (Reade, Citation2021) in their portrayal of influencers’ lives.

Authenticity as an ideal, however, is essentially unstable (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017) and always relative to something else: an inauthentic other. Within the social media ecology (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019), we see how different social networking sites ‘battle for the mantle of authenticity’ (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017, p. 1) as they play authenticity markers off one another. If Twitter provides real-time authenticity, then Facebook’s self-representation affords nominal authenticity; Snapchat’s spontaneous authenticity sets it apart from Instagram and its creative authenticity, whilst other platforms offer anti-commercial (Ello), anonymous (Whisper) and even segregated authenticity (Google+) (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017). Amidst this smorgasbord of mediated authenticity (Enli, Citation2015), Finstagram appears to leverage several authenticity markers all at once: a spontaneous (less curated) creativity that hides under the cloak of anonymity whilst being purposefully set apart from mass viewing and – on many occasions – unfettered by market dynamics. As such, Finstagramming emerges as a means of escaping the calculated authenticity (Pooley, Citation2010) and ‘reputational baggage’ that weighs many socially mediated exchanges down (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017, p. 15). As a resistance strategy, Finstagramming enables users to move beyond the ‘authenticity bind’ (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019), a tension between being ‘real enough’ but not ‘too real’ (Marwick, Citation2013) that can suffocate creative identity work on social media.

Rather than gauging the perceived greater authenticity of Insta (main) over Finsta (fake) accounts, we argue that the latter offers an emancipation from the pressures to conform to the attention economy (Drenten et al., Citation2020; Marwick, Citation2015), whereby its smaller scale, more exclusive nature momentarily liberates them from the (socially mediated) importance of being authentic. This notion of ‘escape’ is by no means alien to marketers (Kozinets, Citation2002). In fact, the market is replete with immersive experiences that offer consumers a fleeting escape from societal pressures, for instance through extreme forms of leisure (Scott et al., Citation2017) or detoxing from our digital connectivity with new forms of unplugged tourism (Radtke et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the irony of entrapment has not been overlooked in the literature (Kozinets, Citation2002), where attempts to escape the market remain bound by market dynamics. In our study, we see how, although both profiles remain tethered to the platform’s logics (Davis & Chouinard, Citation2016; Hurley, Citation2019), Finstagramming is less about ‘winning’ at a visibility game (Cotter, Citation2019; Duffy & Hund, Citation2019) and more about the ‘sanctity’ (Watercutter, Citation2021) of being free to share more creative and seemingly genuine – if not ‘amateurish’ (Abidin, Citation2017) – content that might otherwise be judged or even castigated on their main accounts. This makes Finstagram a powerful resistance strategy within today’s attention economy (Marwick, Citation2015) for celebrities, teens and influencers alike. By unravelling how Finstagram affords a sideways escape (Kozinets, Citation2002), our study contributes to ongoing debates on influencer resistance (Cotter, Citation2019; Fiers, Citation2020; O’Meara, Citation2019) as we foreground how Finstagram enables users to circumvent algorithmic confines without ever leaving the platform (Cotter, Citation2019; Noble, Citation2018), overcome prescriptive aesthetics (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019; Reade, Citation2021) and resist a socially mediated authenticity (Enli, Citation2015), whilst fostering higher levels of engagement through bespoke connective labour (Drenten et al., Citation2020) among members within this more exclusive, safe enclave (Kozinets, Citation2002). How influencers cultivate differentiated online identities and leverage authenticity across the multi-account affordance of the platform merits further attention as it sheds light on their enacted creativity within the attention economy (Marwick, Citation2015). Moreover, our study reveals a bleeding (Abidin, Citation2018b) of this mediated authenticity across various accounts, whereby the seemingly emancipated, and even non-commercial digital work within Finstagram can in fact feed into influencers’ mainstream monetizable personal brands.

To address these points, we first examine portrayals of authenticity within our digital age, how influencers use digital affordances to connect with followers (Drenten et al., Citation2020) and play a visibility game, and lastly how Finstagram acts as a resistance strategy to help leverage authenticity. We then present our dual-method approach to the field, namely netnography and in-depth interviewing. In our use of netnography (Kozinets, Citation2019) we explored the dual-visual identities and storytelling (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019) of 50 influencers, comparing main and Finsta accounts. This rich digital data is coupled with interviews (Charmaz, Citation2014) with six influencers, where we unpack the drivers behind their profile-toggling, how they perform authenticity across these accounts, and how they use their multi-profile personae for commercial success and personal wellbeing. Our thematic findings unravel the crafting of authenticity and the aesthetic and emotional labour involved in this storytelling; as well as how influencers leverage authenticity across the multi-account affordance of the platform. In our concluding thoughts, we consider the role of Finstagram as an emancipatory space for influencers (Kozinets, Citation2002), noting how having to negotiate authenticity might impact their public/private lives (Dobson et al., Citation2018) across multiple accounts. Additionally, we explore the implications these findings have on practitioners.

Literature review

Authenticity demands in the age of the attention economy

Authenticity is a loaded word that has long been at the heart of our social theorising of the self (Burke & Stets, Citation2009). Within this theorising, we understand that we negotiate idealised images and authentic performances of our self for others to see Goffman (Citation1990), and we acknowledge the tensions inherent in this ‘selfing process’ (Davis, Citation2014). As an impression that we make for others (as well as for ourselves), authenticity refers to ‘an uncalculated core, an unmediated guide for the actor’s inner thoughts and emotions, such that outward actions are mere reflections of what lies inside’ (Davis, Citation2014, p. 505). Beyond performativity (Goffman, Citation1990), Davis (Citation2014) argues how authenticity must be felt, where ‘one strives not only to seem authentic but also to be authentic’ (p. 506).

With the rise of our ‘networked era’ (boyd, Citation2010) and the cornucopia of digital affordances of online platforms (Hurley, Citation2019), the way we present ourselves ‘authentically’ has reached new heights, such that we can highlight or conceal aspects of our identity (Davis, Citation2014) with greater ease, freedom and speed than ever before (Marwick, Citation2015). Whereas previous research examines the congruity of these mediated, ‘disembodied’ representations of ourselves (Reade, Citation2021) vis-à-vis our offline physical personae (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019), others have argued for the porosity of our physical and digital selves (Davis, Citation2014), so that our online performances are ‘more or less faithful representations of an offline, corporeal self’ (Schultze, Citation2014, p. 85). For Abidin (Citation2018a), authenticity on social media is part of a ‘performative ecology’, where digital and material worlds bleed into one another and therefore there is no real self behind one’s online front. It is through this ‘porous authenticity’ (Abidin, Citation2018b) that influencers are able to ‘entice their audience into evaluating how genuine their persona is’ (Reade, Citation2021, p. 538). This bleeding of offline lives into online personae has in fact revolutionised the way we market today (De Veirman et al., Citation2017), whereby traditional forms of advertising (Djafarova & Trofimenko, Citation2019) have been replaced by professional content creators as online opinion leaders, who appear to enact ‘rawness’ (Reade, Citation2021) and sincerity (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019) in their recommendations. Instagram – as a ‘highlight reel’ (Reade, Citation2021, p. 536) – helps these content creators depict authenticity through their posts (Lim et al., Citation2015), whereby they make informed choices about what intimate information gets disclosed and what remains hidden from view (Reade, Citation2021). Although Instagram has been deemed an authentic and creative social-networking site since its launch in 2010 (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019; Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), it is important to assess the performativity of this digital self-representation (Abidin, Citation2018b).

The authenticity of Instagram has been dubbed as ‘calculated’ (Halpern & Humphreys, Citation2016, p. 73) or ‘curated and controlled’ (Abidin, Citation2018b) whereby authenticity is presented on the platform as an ideal or fantastical (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019; Hurley, Citation2019), rather than a tangible reality. Instagrammers attempt to appear real to others in the hope of sparking ‘affective encounters’ with their followers (Reade, Citation2021), as well as attracting commercial attention from brands seeking genuine endorsements for their market offerings (Cotter, Citation2019; Drenten et al., Citation2020; Duffy & Hund, Citation2019; Marwick, Citation2013, Citation2015). This pressure on influencers to project themselves as authentic is classified as the ‘visibility mandate’, where they feel a directive to put oneself out there and deflect any potential critique of being ‘not real enough’, whilst also avoiding stepping into territory that could be perceived as ‘too real’ (Cotter, Citation2019). Marwick (Citation2013) sees this tension of being ‘real enough’ but not ‘too real’ as an ‘authenticity bind’ (p. 196) where influencers walk a thin line of self-commodification (Drenten et al., Citation2020) between visibility vs. vulnerability (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019; Duffy & Pruchniewska, Citation2017). Striking this balance is crucial for influencers’ livelihoods (Duffy, Citation2019) as career success is directly linked to data-driven metrics (i.e. likes, followers and comments) that make influence and status legible to both advertisers and audiences (Pooley, Citation2010).

Paradoxically, as influencers grow in popularity, their aura of authenticity wanes (Duffy, Citation2019), trapped as they are in the ‘authenticity bind’ (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019) where they fight to ‘reconcile self-promotion and expressive distinction’ (Pooley, Citation2010, p. 77). Compared to models and celebrities, professional content-creators or influencers (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019) – who are regular individuals that have accrued a following on social media (Jin et al., Citation2019) – are perceived as more relatable to consumers and therefore more credible in their endorsements (Schouten et al., Citation2020). The ‘rawness’ of their stories draws followers in Reade (Citation2021); the amateur quality of their imagery (Abidin, Citation2017) is seen to be a reflection of life, not Hollywood; and the connectivity (Drenten et al., Citation2020) they foster with their audience is a testament that they are friends not salespeople (Yuan & Lou, Citation2020). Although instrumental to their socially mediated success, authenticity remains a confounding and relative ideal for influencers (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), as they play the balancing act of projecting themselves as ‘real’ (Abidin, Citation2016) whilst also carefully adhering to the tenets of online self-branding (Duffy, Citation2019).

As we enter a post-authenticity age of ‘keeping it real’ instead of parading our #blessed lifestyles (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019), we see how self-disclosure fosters renewed relatability and intimacy among followers (Yuan & Lou, Citation2020). The disclosure of intimate details emphasises one’s (contrived) authenticity and injects moments of candour through a ‘calibrated amateurism’ (Abidin, Citation2017), particularly through the desirably ‘raw’ aesthetic (Reade, Citation2021) of posts. Given the seemingly amateurish, au naturel look of Instragram posts, we see how micro-influencers, that is, influencers with 1000 to 100k followers can join the commercialFootnote2 playing field, with their own non-professional visual narratives of somewhat vacuous content (e.g. posts of lattes and sunsets). In fact, micro-influencers can appear more genuine in their engagement and authentic in their content than their macro counterparts (Abidin, Citation2015). Because of their size, micro-influencers feel an obligation to connect more with their followers (Drenten et al., Citation2020), reacting to their comments in real time (Kay et al., Citation2020) which in turn helps boost popularity (Marwick, Citation2016). These communal exchanges heighten the experience (Kozinets, Citation2002) for followers, as engagement appears more exclusive and ‘intimate’ (Abidin, Citation2015; Reade, Citation2021) in nature, making these ‘affective encounters’ between influencer and follower (Reade, Citation2021) feel more genuine (Davis, Citation2014) and less market-mediated.

In the shadow of rich conceptualisations on authenticity (Burke & Stets, Citation2009; Davis, Citation2014) and recent accounts of how influencers’ digital labour enacts authenticity (Duffy, Citation2019; Duffy & Hund, Citation2015), our study examines how macro influencers use Finstagram as a resistance strategy to leverage authenticity across multiple digital personae and recoup some of the ‘raw’ intimacy (Reade, Citation2021) of smaller scale communal exchanges. By manipulating the platform’s affordances (Hurley, Citation2019), Finstagramming allows for seemingly freer, more intimate content compared to mainstream Instagramming, so that this emancipatory outlet (Kozinets, Citation2002) enables more genuine accounts to both be ‘seen’ and ‘felt’ by followers (Davis, Citation2014).

Technological affordances and playing the visibility game

Instagram’s multimodal affordances are what enable its creative authenticity, where the platform’s ‘promise of authenticity is through filtered enhancement’ (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017, p. 12). The storying of Instagrammers’ lives occurs through the platform’s digital affordances (see Drenten et al., Citation2020 for a deconstruction of the platform’s anatomy), the photographs, captions, comments, filters, hashtags and videos they post, which act as ‘material property communicating meaning’ (Hurley, Citation2019, p. 2) to audiences. As ‘dynamic link[s] between subjects and objects within sociotechnical systems’, affordances ‘operate by degrees’ of efficacy (Davis & Chouinard, Citation2016, pp. 241–242). Within these subject-artefact relations, we see how Instagram’s affordances foster certain social interactions, whilst suppressing others (Hurley, Citation2019), meaning that they can either help or hinder influencers in their (authentic) curation of their online personae.

Thanks to its technological architecture (Drenten et al., Citation2020; Hurley, Citation2019), Instagram makes it unclear to users how content is positioned in newsfeeds (Cotter, Citation2019), so that influencers battle with algorithms in their effort to maximise exposure (visibility) and engagement (connectivity) with followers (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019). With the increasing monetisation of influencers’ intimate lives (Aslam, Citation2021), Instagram has taken steps to tighten its control over the marketisation and dissemination of content, namely through algorithmic changes (Noble, Citation2018), including the removal of chronological news feeds in 2016 (Cotter, Citation2019). This move thwarted the freedom and inherent creativity of Instagrammers as content creators (De Veirman et al., Citation2017), in terms of what, how and when they posted material.

Consequently, influencers adopt resistance strategies to ensure visibility and increase engagement, namely through engagement pods (O’Meara, Citation2019) and tagging strategies (Fiers, Citation2020). In engagement pods groups of influencers like and comment on each other’s posts to boost exposure, using the platform’s affordance of ‘liking’ to their favour (O’Meara, Citation2019). This share tactic helps stimulate connectivity by accelerating the rate of engagement and visibility (Lim et al., Citation2015). Reciprocal engagement groups act as a kind of ‘mutual back-scratching’, where influencers share newly published posts in private group messages so others can ‘like’ or comment on them organically, expecting the same in return (O’Meara, Citation2019, p. 7). As a result, influencers hope to cheat Instagram’s algorithm into prioritising their content by becoming more visible in the news feeds of their followers (O’Meara, Citation2019). As well as discretely fishing for engagement through reciprocal pods, Fiers (Citation2020) notes how influencers can conceal ‘inauthentic’ or status-seeking strategies, downplaying or concealing hashtags (O’Meara, Citation2019) to give a sense of effortless engagement. However, cultivating buzz around posts and maximising engagement from users is a laborious task that requires ongoing maintenance from account holders, and there is little guarantee that future changes may not render this technical affordance obsolete (Cotter, Citation2019). Moving beyond ‘like counting’ tactics, our study fleshes out how Finstagramming, as a resistance strategy, is more about focusing on the quality of engagement (Kang & Wei, Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2021).

As well as jockeying the platform’s affordances for heightened engagement, influencers must also consider how they post content. ‘Double posting’ is taboo on social media and can diminish credibility and marketability for the one posting (van Dijck, Citation2013). As well as how often influencers post, they need to consider the aesthetic appeal of their content. Visual affordances inherent in the platform – the photos, videos, filters and emojis – are markers of creative authenticity (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), encourage ‘artivism’ amongst users (Carrasco-Polaino et al., Citation2018) and give rise to a monetised visual economy (Citton, Citation2017). These multimodal affordances allow influencers to conjure ‘self-presentations of idealised authenticity’ (Hurley, Citation2019, p. 5). However, artistic overkill or delusional self-representations can in equal measure be reprimanded (Ross, Citation2019) if we think of how the popularisation of #nofilter to help signal a seemingly truer, more authentic image (Marwick, Citation2015).

While Instagram offers an array of affordances for curating content (Hurley, Citation2019), there remains a concern that algorithms exercise too much power in influencing social realities (Gillespie, Citation2014), as well as perpetuating neoliberalism, where influencers’ existence (and worth) is ‘framed and measured in economic terms’ (Hurley, Citation2019, p. 5). Cotter (Citation2019) envisions a ‘visibility game’ that is played by influencers to mitigate the power of the platform’s digital affordances. With little control over its technical infrastructure, influencers instead manipulate the social and economic value they can accrue on Instagram (O’Meara, Citation2019) employing tactics that pursue (visible) authenticity and that grow their follower base (Gillespie, Citation2014). ‘Finsta’ accounts become influencers’ secret weapon as they play the hegemon at its own game.

‘Finsta’ accounts as profile-toggling – new influencer strategies

Amidst growing pressure to perform in line with the platform’s algorithmic strictures and feeling constrained about what to post (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019), we have seen the rise of Finsta (or secondary) accounts as a means of seeking out alternative forms of representation. Forsey (Citation2019, n.p) defines Finsta as ‘a chance to share a goofier, less-edited version of yourself with a trustworthy group of friends – and for those friends to see less “perfect” posts, and more real ones’. Whereas main accounts operate within ‘the cultural conventions of social media performativity’ (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019, p. 131) with highly curated posts and fishing for likes (Reade, Citation2021); Finstas subvert this orthodoxy (Kozinets, Citation2002) encouraging users to be more light-hearted, critical, ironic, and even vulnerable within an allegedly judgement-free zone (Haenlein et al., Citation2020) and a more intimate community (Jin et al., Citation2019). Here, they can work on more genuine ‘affective encounters’ (Reade, Citation2021) and connectivity with a smaller number of followers (Drenten et al., Citation2020), where their emotional work (Hochschild, Citation1983) looks and feels more real (Davis, Citation2014). Finstas are often described as a VIP backstage arena, where only a handful of followers witness the truly intimate happenings (Patterson & Ashman, Citation2020) and ‘behind the scenes’ activities of influencers (Ross, Citation2019), including uncensored material about the digital labour they perform (Duffy & Hund, Citation2015).

In this emancipatory space (Kozinets, Citation2002), distanced from the personal branding and inherently monetised activities of their main account, influencers can share content more freely, including unedited photos and diary-like entries, or even focus on new interests such as pets, lifestyle, food, etc (LaBrie et al., Citation2021). Given the smaller size of Finsta audiences, many of the taboos associated with posting under the algorithmic constraints (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019) become rescinded, for instance influencers can open up about sensitive topics, such as societal pressures impacting women on social media today (Elias & Gill, Citation2018) or share ‘edgier’ (or R-rated) content that might otherwise jeopardise their reputation if leaked to the wrong audience (potential employers or parents) (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019, p. 131). At the other end of the spectrum, researchers identify Rinstagram (real+Instagram) (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019) as an influencer’s main account, which is typically monetised and has a high number of followers (Williams, Citation2016). Without having to negate and/or threaten the commercialised, socially conforming curated self (Van Dijck, Citation2013) of their ‘real’ accounts, strategic influencers can toggle between their main, highly visible and monetised Rinsta accounts, and their subversive, exclusionary and seemingly more ‘genuine’ Finstas accounts. As such, Finstas act as breathing spaces for influencers in our age of digital surveillance (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019).

Within the paucity of research on Finstagram as a new genre of resistance, Kang and Wei (Citation2020) call for richer data detailing the motivation driving this practice as well as the content of these secondary accounts. Our study answers this call as we further our understanding of the phenomenon of Finstagram by comparing influencers’ main and secondary accounts, examining their toggling across multiple accounts, assessing how these differentiated digital personae help cultivate engagement and a sense of authenticity with followers, and whether or not content and following bleed from one account to another, thus impacting their personal brand. To do so, we adopt a dual-methodological approach to collecting data which we examine next.

Methodology

Underpinned by interpretivism (Goulding, Citation1999), our study adopts a dual-method data collection, namely netnography (Kozinets, Citation2019) and in-depth interviews (Charmaz, Citation2014), to unravel the visual storytelling (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019) of influencers across multiple accounts and digital personae. Whereas Gurrieri and Drenten’s (Citation2019) application of visual storytelling centres on a media analysis of users’ visual and textual narratives of recovery, where they unpack the processes of these shared visual stories as intimate and vulnerable disclosures of Instagram users, our interests lie in fleshing out influencers’ differentiated digital personae, how they leverage authenticity across multiple accounts of the same platform, and how they use Finstagram as an escape to evade the rules of a ‘visibility game’ (Cotter, Citation2019). As such, our study unearths the digital labour (Duffy & Hund, Citation2015, Citation2019) – the aesthetic, emotional and connective work (Drenten et al., Citation2020) – that lies behind these parallel profiles, as we assess the how and why of influencers’ profile-toggling and whether or not their mediated authenticity (Enli, Citation2015) bleeds (Abidin, Citation2018b) across these various accounts.

In our netnography (Kozinets, Citation2019) we studied a total of 50 influencers who self-identified as profile-togglers. A range of influencer typesFootnote3 were included ranging from micro to mega based on main accounts with follower numbers that ranged from 100,000 to over 1 million. We follow Jeffrey et al. (Citation2021) in their approach to covertly ‘lurk’ on social media as a means of capturing a genuine lived experience of influencers in situ (Heinonen & Medberg, Citation2018). Posting content online, some argue, implies providing consent to third parties (Walther, Citation2002), so for our netnographic material of 50 influencers, we exclusively accessed accounts that were publicly available. The material that interested us was captured via screengrabs (Zappavigne, Citation2016) between 2020 and 2022 and analysed by the authorial team. As public content, we share links to influencers’ profiles and refer to original @handles in the text, although no original images from our netnography are reproduced in this study. To help in the analysis of this data, particularly in the distinction between the main and Finsta account, the French digital data website www.tanke.fr was used compare and contrast influencers’ dual accounts, paying particular attention to the ‘affective encounters’ (Reade, Citation2021) or engagement rate of these exchanges.

The number of followers an influencer ‘owns’ is not the only criteria by which to measure success and brand status (Kay et al., Citation2020). Deep-rooted engagement rates can be a better indicator of an influencer’s potential worth, particularly when considering brand partnerships (Schouten et al., Citation2020). In their study on sexualised labour on Instagram, Drenten et al. (Citation2020) recorded differentiated ‘connective labour’ among a hierarchy of influencers, as engagement with followers is not necessarily uniform on the platform. Engagement rates suggest how ‘real’ an influencer’s connection and interaction is with their audience as the figure presents the proportion of people who see a post and interact with it (e.g. like or comment). Relatability and engagement seem to go hand in hand (Reade, Citation2021), so that the more an influencer ‘grows’, the less relatable they become (Duffy, Citation2019). Engagement rates tend to decrease when an influencer gains over 100k followers, and even more so when they become mega influencers and gain over 1 million (O’Meara, Citation2019). To regain credibility, influencers toggle between accounts, weaving more relatable material and seemingly authentic portrayals of themselves on Finsta accounts. Homing in on the ‘affective encounters’ (Reade, Citation2021) taking shape in this more exclusive space (Kozinets, Citation2002) of Finstagram, and directly comparing these exchanges to the contrived engagement levels of their main profiles, sheds light on the emotional labour (Hochschild, Citation1983) of influencers in these secondary accounts, revealing layers of (performed) authenticity on both profiles. On average secondary accounts showed an increase engagement rate of around 175%, testifying to the clout of these more intimate spaces and personalised interactions (Haenlein et al., Citation2020). Compared to Drenten et al. (Citation2020) typology of influencers with their stratified ‘connective labour’, we witness the very same influencer performing differentiated connectivity on parallel accounts. With heightened engagement rates, it becomes clear that the digital labour (Duffy & Hund, Citation2015, Citation2019) of Finsta accounts feels more ‘real’ (Davis, Citation2014) than mainstream, algorithmically prescriptive Instagram profiles.

To illustrate this distinction between main and Finsta accounts, presents celebrity and influencer Justin Bieber’s contrasting Instagram profiles, as one of the 50 influencers that made up the netnographic sample for this study. Here we see how engagement on his Finsta vis-à-vis his main account has risen ten-fold from 2% to 23%:

Table 1. Sample of netnographic data: comparing the digital labour of a main and Finsta account of the same influencer.

We enhanced this comparative data by examining the visual imagery and textual content (in the form of comments, hashtags and captions) of influencers’ visual storytelling (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019) across both accounts. This allowed for sensemaking of how influencers use the platform’s technical affordances (Hurley, Citation2019) to perform (layers of) authenticity on both profiles – in tandem – without ever jeopardising the ethos of either account. Staying with Bieber’s account as illustrative, we see how his main account @justinbieber (https://instagram.com/justinbieber/) focuses on his celebrity persona with professional and amateur photography, whereas his Finsta account @kittysushiandtuna (https://www.instagram.com/kittysushiandtuna/) centres on his pet cats, revealing two very different types of storytelling (of the same person) in terms of aesthetics and content.

Alongside visual cues, name handles (@name) were also used to craft differentiated digital personae across profiles (Haenlein et al., Citation2020), at times concealing authorship with a pseudonym as a ‘tactic of surveillance evasion’ (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019, p. 130) or highlighting the ‘realness’ (Davis, Citation2014) of secondary accounts in comparison to the curbed content and aesthetics of main accounts. From our netnography we see, for instance, how influencer @zara_mcdermott’s (https://www.instagram.com/zara_mcdermott/) main account highlights her modelling profession with links and shoutouts to collaborations she has had with the BBC, whereas her Finsta account @atzarashouse (https://www.instagram.com/atzarashouse/) is more confessional and intimate in tone, as she ‘welcomes’ us to her home, using a house emoji in her short bio that reinforces the light, playful nature of her secondary account. Her handles tell distinct stories: a professional woman with a modelling career (@zara_mcdermott) versus an amateur foodie (@atzarashouse) with pictures of her cooking endeavours.

Following our netnography, in-depth interviews (each lasting approximately one hour) with six influencers – who openly practise profile-toggling – gave us insight into the drivers of Finstagramming as well as the mechanism of this dual-profile digital labour (see for participants’ details). Following ethical guidelines, we asked our participants to sign consent forms where they indicated whether they want to be credited for the netnographic material or not. Two out of our six influencer participants gave full consent to use their original names, @handles and reproduce their images from their Instagram and Finstagram accounts (and we have credited them in the text). The rest have been given pseudonyms and none of their netnographic visual material has been included in the paper. During interviews, Instagram screengrabs were used as visual stimuli (Harper, Citation2002) to explore the visual cues and visual storytelling taking place on both profiles. Using a constant comparative method (Charmaz, Citation2014), we were able to connect the dots of our data analysis for a more holistic narrative, until we reached a desired ‘theoretical completeness’ (Glaser, Citation2001).

Table 2. Participants of the study.

Given the exploratory nature of the study, grounded theory (GT) coding (Goulding, Citation1998) was used to weave the various data sources into a cohesive story. Grounded theory’s versatility as a ‘method, a technique, a framework, a paradigm’ (Rodner, Citation2019, p. 156) gives interpretivist researchers the freedom to pick and choose how GT can best help them. GT thematic coding (Charmaz, Citation2014) allowed us to draw nascent theory from our data and through a constant comparison method (Glaser, Citation2001). Moving between a priori theoretical frameworks of emotional, aesthetic and connective labour inherent in influencer marketing (Drenten et al., Citation2020) and the empirical visual and textural material of our study, we anchor our emergent theory on a layered authenticity and multiple personae that are leveraged across the platform’s multi-account affordance. Following Saldaña (Citation2021), we applied first and second coding cycles to our netnographic and interview data, mixing and matching first cycle coding methods which included structural, initial, descriptive (elemental methods) and emotive and values (affective methods) coding, before connecting the dots of our data through axial coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). illustrates some of the first cycle coding (Thornberg & Charmaz, Citation2014), including descriptive, structural and emotive nuances, where we compare the content depicted on both profiles (Insta and the Finsta). Firstly the @handle and bio were examined with terms like ‘real’ and ‘fakeinsta’ featuring in the main account handle. Moreover, the bio also acted as a roadmap guiding followers (predominantly) from the Finsta page, back to the influencers main account. In terms of the main visual content featured in both profiles, the aesthetic layout (Drenten et al., Citation2020) was examined with the main account showing highly curated and posed images with promotions notably visible. In comparison, the Finsta account typically contains random, misaligned and unstaged visual content with some influencers explicitly stating and embracing this ‘no filter’ aesthetic, e.g. ‘Here is what my life looks like without a filter and without me trying to be cute’ (@therealjadetunchy see ). Alongside this analysis, the follower count and engagement rates were explored to provide a comparative overview of connectivity (Drenten et al., Citation2020) using aforementioned www.tanke.fr. Through our second cycle, we were able to connect the ‘bones of our analysis’ into a theoretical ‘working skeleton’ (Charmaz, Citation2014) inferring the motivations and strategies of influencers’ profile-toggling, as well as illustrating their aesthetic, emotional and connective labour, meaning-making, and layered portrayals of authenticity, thus revealing porous digital labour (Duffy & Hund, Citation2015, Citation2019) across profiles.

Table 3. Grounded theory coding: a thematic analysis of netnographic data.

Findings

Our examination of Finstagramming as a means of escaping the pressures of Instagram’s calculated (Halpern & Humphreys, Citation2016) and controlled (Abidin, Citation2018b) authenticity reveals how influencers strategically toggle between different digital personae. Here we flesh out how influencers perform differentiated digital labour (Duffy & Hund, Citation2015, Citation2019) across their main and Finsta accounts, so that the stories they tell (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019) and ‘affective encounters’ (Reade, Citation2021) they foster with their audiences engender palpably different calibres of authenticity. Without ever leaving the platform, influencers toggle between the manufactured, monetisable, highly visible and conforming authenticity of their main accounts, and the emancipated, spontaneous, ‘more real’ and unburdened authenticity of their Finsta accounts. We know of other emancipatory events, like festivals, that enable consumers to momentarily free themselves from social and economic order whilst remaining entrapped by market logics (Kozinets, Citation2002). We argue that Influencers adopt Finstagram as a supposed means of escaping the digital attention economy whilst seemingly remaining tethered to social mediated authenticity markers (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017). To unravel this paradox of embedded escapism, we first we explore how influencers craft their tales of authenticity in the aesthetic and emotional labour they perform, and, second, how they leverage their authenticity across their unbounded, porous accounts.

Crafting authenticity – looking and feeling ‘real’

The secret of influencers’ ability to build intimate relationships with their followers (Yuan & Lou, Citation2020) lies in the perceived authenticity of their activities online, where their emotional work feels ‘deeper’ compared to the ‘surface’ work of their main accounts (Hochschild, Citation1983), and their aesthetic labour looks more real (Reade, Citation2021). Once their main accounts become too commercialised and their following too large, influencers find more freedom for their digital storying on their Finsta accounts, where they aim to reflect more genuinely to their followers ‘what lies inside’ (Davis, Citation2014, p. 505). Liam sheds light on his less contrived Finsta persona:

I’m more expressive and I show more of my personality… It’s much more light hearted…more of a look at my day-to-day life… I really don’t care, I posted a photo of a Red Bull can in a supermarket. (Liam)

The ‘judgement free zone’ of Finstagram’s intimate community (Ross, Citation2019, p. 368) creates a sense of communitas (Kozinets, Citation2002) where influencers feel free to share more light-hearted content that remains out of sight of the surveillant gaze of mainstream social media (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019; Elias & Gill, Citation2018). As well as content, we see how influencers use Finsta accounts in a more spontaneous manner (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), posting stories that appear more organic and less ‘calibrated’ (Abidin, Citation2017) than their main accounts. Comparing the grids on his main and Finsta accounts, Joe comments how

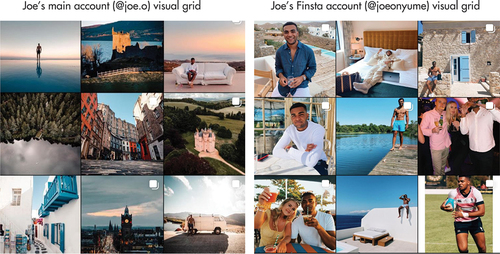

If you take the first grid of nine photos of my alternative account… if you categorise them it definitely portrays me and my passions and what I enjoy… represents what I stand for and my values most accurately … it is very centred around myself and what I’ up to and more real life, some organic few moments. (Joe)

Spending less time on picture-perfect representations (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019) typical of highly curated main accounts, we see how Finstagram allows him to focus on genuine passions, rather than prescribed aesthetic labour (Elias & Gill, Citation2018). As such his Finstagram becomes an emancipatory outlet (Kozinets, Citation2002) where he can share intimate tales of his day-to-day life (). Whereas his main account portrays his more curated self, with his nine-tile grid dominated by semi-professional landscape photography offering little evidence of the man (or subject) behind the camera, his Finsta profile (although aesthetically still highly polished) brings the subject (Joe) back to the fore and focuses more on the people (friends) and activities (sports and hobbies) that make up his life. On the performativity of his main profile, Joe notes how

Figure 1. Comparing 9-tile visual storytelling across main and Finsta accounts. Source credit: permission received from participant to use original images and @handles.

My main account is a glorified lifestyle of myself… I may go out to shoot a specific place in mind, rather than taking an image in the moment and by chance getting an ‘insta-worthy’ photo. If I took the first nine squares of my profile it I may go out to shoot a specific place in mind, rather than taking an image in the moment and by chance getting an ‘insta-worthy’ photo. If I took the first nine squares of my profile it 9–5pm…[this] doesn’t show the personal side of me so much. (Joe)

As Joe’s case illustrates, main profiles can be reserved for professional, commercially viable content, with a focus on highly curated – even dehumanised – imagery, whereas Finsta accounts bring the subject back, narrating their sociality, playfulness, humanness, criticality or even vulnerability. For Joe, Finsta allows for greater connectivity or communal exchanges (Kozinets, Citation2002) with followers, where ‘affective encounters’ (Reade, Citation2021) are unencumbered by mercantile or societal pressures. He acknowledges that on his Finstagram engagement is more sincere thanks to the spontaneity and genuineness behind his posts and stories. Recalling social media’s taxonomy of authenticity (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), main accounts on Instagram champion creative authenticity through carefully curated aesthetic work, whereas Finsta ones thrive on the emotion work of spontaneous and exclusive encounters with followers which look and feel more real (Davis, Citation2014). Although clearly more relaxed than the professional imagery of his main account, with controlled environments and photographic equipment, some tiles of Joe’s Finsta account continue to feel ‘contrived’ (Abidin, Citation2017), evidencing an entrapment by mediated authenticity and a subsequent layered performance across his accounts.

Regarding the aesthetic labour involved, Cameron comments on how the process of shooting, editing and posting a photo is significantly simplified on Finstas compared to the heavy ‘visibility labour’ (Abidin, Citation2016) demanded by main accounts. Given the labour involved in maintaining a socially acceptable, commercially viable profile (Duffy, Citation2019), Finstas act as emancipatory spaces (Kozinets, Citation2002) that allow influencers to share more amateur visual content (Abidin, Citation2017). Comparing the curatorial work of the two, Cameron explains how

I spend longer editing on my main account and use software like Photoshop to aid the process. The thought process behind it is long, and I definitely sway a lot between ‘do I/don’t I post’. I use a professional camera to take pictures for my main account whereas on my alternative account … I may take an image ‘in the moment’ and by chance get a ‘insta-worthy’ photo. (Cameron)

Our netnography echoes this, whereby Finsta accounts portrayed seemingly less professionally curated imagery when compared to the high-quality, staged nature of Instagram posts. In the case of @milliehannahhh (www.instagram.com/milliehannahhh/), we find her main account to be sharp, performed and populated by photographs captured on good-quality cameras, whereas her Finsta feeds on @35mmillie (www.instagram.com/35mmillie/) are more genuinely spontaneous (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), captured as they are on her non- digital 35 mm camera with its distinctive poorer image quality. The grainy, ‘raw’ quality (Reade, Citation2021) of her photos taken on the pre-social media 35 mm camera are perceived as more carefree and ‘in the moment’ and therefore experienced as more ‘real’ (Davis, Citation2014).

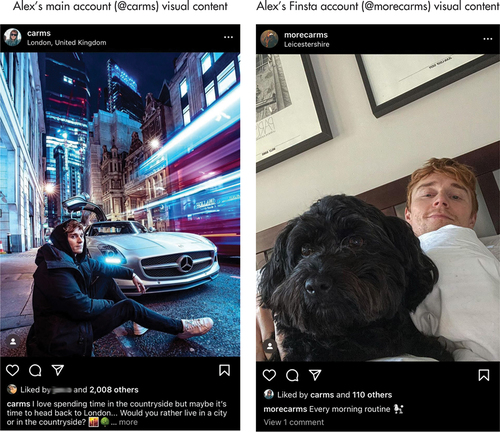

Although images on Finstas may be more relatable, Alex explains that Finstagramming is not a ‘fishing for likes’ (Fiers, Citation2020) exercise. For him, Finstagram acts as a safe haven for posting unedited, intimate behind-the-scenes footage of his everyday life, whereas his main account competes for attention (Marwick, Citation2015) as it portrays professional travel photo shoots (see .

So I created my second account to continue sharing content that is not curated.

I don’t care if my pictures get minimal likes.

My personal account says ‘this is the real me’. (Alex)

Figure 2. Comparing visual content on main and Finsta accounts. Source credit: permission received from participant to use original images and @handles.

Although not driven by like-hunting (Fiers, Citation2020), the rawer content on Finstagram reveals heightened levels of engagement in the form of meaningful comments and ‘affective encounters’ (Reade, Citation2021), as followers feel they are more privy to the intimate lives of influencers. As influencers appear to invest less into the curatorial economics (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019; Reade, Citation2021) of their Finsta accounts, they focus their digital labour more on connective labour (Drenten et al., Citation2020), nourishing communal exchanges (Kozinets, Citation2002) with followers. On this communitas, which appears unhindered by the logics of the attention economy, Cameron explains how he prefers the encounters taking place on Finstagram, where ‘only selected people can see [what you post]’. He admits to engaging more in this space, direct messaging (DM) people and speaking directly to the camera,

I speak to the camera directly and more interactively a lot more … I try to gain feedback and I check my secondary account DM’s much more actively, because it’s less overwhelming and it’s more fun as the number of followers on there is much less. If the account had as many followers [as the main one] I wouldn’t be able to talk to them all as I do. (Cameron)

As part of this heightened engagement, stories shared on Finstagram are longer and more detailed, even more confessional in tone, compared to the more ‘contrived’ authentic narratives (Abidin, Citation2017) on main accounts. Whereas main accounts can be skeletal in content, with short, uninformative captions, or riddled with sponsored hashtags (Haenlein et al., Citation2020), Finsta accounts tell more detailed stories. This is captured vividly in Jade’s posts, where a single emoji gets posted on her main account, compared to the diary-entry caption of her Finsta (see ).

Table 4. Comparing textual narratives of main and Finsta accounts.

The segregated nature of these spaces from mainstream viewing (and judgement) motivates influencers to open up and dialogue more directly with their followers (Drenten et al., Citation2020). Over Finstagram, we see influencers engaging in ‘deeper’ (Hochschield, 1983), more meaningful and even personalised exchanges with their followers (Drenten et al., Citation2020), even to the point of sharing their personal lives and vulnerabilities (Duffy & Pruchniewska, Citation2017).

Porous membranes and bleeding narratives – leveraging authenticity through multi-account affordances

Influencers perform different digital work and develop distinct digital personae across their multiple accounts, using Finsta accounts as a hiding space from the panoptic gaze and socially mediated pressures of mainstream Instagram. Nascent literature on the topic suggests that Finstagram emerges as a censoring tool for influencers wishing to keep sensitive content out of plain view (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019). As well as affording escapism from the masses, we argue that profile-toggling allows influencers to sidestep genres, cultivating different digital personae (and degrees of authenticity) without impacting their overall personal brand and/or profession. From our netnography, we witnessed genre side-stepping as influencers toggled across accounts. For instance, we saw how fashion and lifestyle influencer @sarahhashcroft (www.instagram.com/sarahhashcroft/) metamorphoses into a homeware and interior design influencer on her Finsta account @sarahashcrofthome (www.instagram.com/sarahashcrofthome/), where she is known as showcasing an expertise in her alternative account that might otherwise get overshadowed by the content of her primary one. Her specialisation gets clearly signposted in her handle, so that @sarahashcrofthome (Finsta) signals something different from @sarahhashcroft (main). Through Finsta she takes her smaller circle of followers into the privacy of her home and decorating endeavours. Whereas some influencers humanise their Finsta accounts with friendships or pets, Sarah’s storying revolves around a redecoration journey. This behind-closed-doors account of a lifestyle influencer turned interior designer not only fosters relationality (Dobson et al., Citation2018) but also provides a more personal touch to the influencer’s recommendations (Casaló et al., Citation2020) so that her endorsements (for homeware) are seen as more genuine (Schouten et al., Citation2020; Torres et al., Citation2019). It appears as if in her escape from a mainstream, highly polished, monetised account, @sarahashcrofthome never truly frees herself from the market dynamics (Kozinets, Citation2002) of the platform. The perceived intimacy of a Finsta account can also be a calculated strategy on the part of influencers to craft a secondary business or brand for themselves. For Liam, profile switching affords differentiated digital work with various online communities:

[Finstagramming] has allowed me to gain much more understanding of the various uses of social media…to run a page for a business, to act sensitively, to really build a following, to tread carefully, how to interact with people and how to use certain Instagram features to maximise potential. (Liam)

Influencers use their awareness of the platform’s affordances to craft various digital personae and perform differentiated digital work. For some this digital work acts as a creative and emotional outlet, whereas for others it is a profitable opportunity that affords innovation (via the Finsta account) without interruption of the status quo (i.e. main account). Showcasing the porosity of profiles, Liam led a select group of followers from his main account to his more exclusive Finsta one where he offered a more tailored online experience, affording him a sense of segregated authenticity (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017). In creating a private account by invitation only, Liam was able to charge his Finsta followers a monthly subscription to access his exclusive fitness programme:

I was motivated to create my second account for monetisation purposes … I wanted to try and gain an income from the followers that I had built up on my main account. I saw someone else that I followed exploring the more polished and creative aspect of Instagram in greater depth … I wasn’t faking any kind of passion, but I was curating with followers in mind. (Liam)

Although the motivations for toggling between various accounts on the same platform may vary, some seeking to escape market logics whereas others actively create new markets for themselves, the entrepreneurial drive of influencers’ circumvention of the algorithmic constraints of the platform remains the same (O’Meara, Citation2019). In their switching, influencers get some respite from the internal and external pressures of Instagram, showcasing their creativity and digital savviness. On this escapism, Liam comments on how he navigated the issue of ‘double-post taboo’; that is, the constraints of encapsulating lived experiences and photography into a single, quintessential image (Ross, Citation2019). Thanks to his Finsta, Liam was able to post more than once a day without risking diminishing his credibility or jeopardising his likeability factor (Reade, Citation2021):

My alternative Instagram account allows me to portray the zoomed-in passion of mine without it being frowned upon. I can post every day and more than once a day, because I want to grow an audience, without it being perceived as weird by family and friends. My alternative account is a private place for me in a sense; it’s not followed by any family or friends. (Liam)

Finsta accounts afford a sense of freedom (Kozinets, Citation2002) not only regarding the look and feel of the posts, but also in the digital labour that lies behind this content; for instance when it comes to frequency of posting. Echoing Liam, Jude notes how he felt stifled and ‘in a box’ when it came to content curation on his main account, while profile-toggling allowed him to post according to his own creative interests, with less risk of judgement. Out of sight of the surveillant masses (Elias & Gill, Citation2018), Finstagramming allows users to momentarily drop the mask (Goffman, Citation1990) of their Instagrammable authenticity, affording a more relaxed self to come to the fore:

I didn’t want people to think “why is he changing up the level of posting perfection that he normally posts?” There is an expectation set in the visuals and effort I put into the content on my primary account… so I created another one… I felt that I was “in a box” on my work account. It really means I can post whatever, whenever and to whoever on Instagram freely… I can share more content without the pressure of worrying if it’s good enough. (Jude)

More than just content shifting, Finsta accounts allow for identity-switching, as influencers dabble in new genres within these emancipatory spaces (Kozinets, Citation2002). Rather than risk losing follower engagement because of a brash shift of style or a confusing collage of genres on a single profile, influencers utilise Finsta accounts as viable outlets for genre development, leveraging their personal brand(s) and mitigating their status-seeking intentions (Fiers, Citation2020) in the process.

Some influencers are quite candid about their multi-account hopping as they purposefully ‘shout-out’ to their doppelgänger accounts, evidencing the porosity of their digital personae. For instance, influencer @jadetunchy directs her followers to her Finsta account @therealjadetunchy ‘For fun’. Jade openly invites audiences to experience different degrees of her authenticity, much like Abidin’s (Citation2018b) notion of ‘layers of identity’. Moreover, she signposts that Finsta is where one finds ‘the real’ Jade Tunchy (@therealjadetunchy) versus her more professional digital persona (@jadetunchy), using the platform’s technological affordances of handles (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019) to narrate her authenticity or ‘rawness’ (Reade, Citation2021). Somewhat tongue in cheek, Jade mocks the unrealistic ethos of Instagram, pocking fun at the lack of reality of mainstream accounts versus Finsta. Her Bio highlights how her Finsta captures ‘what [her] life looks like without a filter and without [her] trying to be cute’, similar to a #nofilter self (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017). Those looking for a ‘prettier’ version of Jade (and her lifestyle) get directed to her main account. Similarly, Anastasia is also candid about her multi-account existence and the bleeding across her profiles,

My alternative account portrays my unique-selling point very clearly… I have testimonials and user-generated content on this account to show proof that I am genuinely good at my job. This visual progress creates a community feel and demonstrates that I’m not like everyone else. The accounts are linked together. I have my alternative account @name in my biography on my primary account. I think the extra source of information allows me to deliver clear and genuine intentions. (Anastasia)

For Anastasia, profile-toggling helps influencers develop their narratives in an organised and structured manner. As a fitness influencer, her Finsta builds on her expertise in the industry whilst acting as a testimonial to her main account. Like Jade – who directs people to her ‘funnier’ side on her Finsta – Anastasia does shout-outs on both her main and Finsta accounts to encourage followers to tap into the content most pertinent to them. Given how saturated the influencer market is, Anastasia argues that Finstas are more of a necessity than a fun outlet, as influencer must distinguish themselves from disingenuous activities of what she deems ‘inferior quality’; for instance, influencers posting vacuous homogenous imagery or overloading a post with vast Hashtag Clouds.

Authenticity thus gets cultivated – to differing degrees – on Instagram via influencers’ main and Finsta accounts through visual and textual content, but also through the strategic use of the platform’s affordances (Hurley, Citation2019), including handles and biographies. Whereas Abidin (Citation2018b) views authenticity bleeding from our material into our digital worlds through a ‘performative ecology’ (Abidin, Citation2018a), we see layers of authenticity bleeding across the influencers’ different digital personae. As influencers’ accounts become more professionalised (Drenten et al., Citation2020; Duffy, Citation2019), more sophisticated (Cotter, Citation2019) and more commoditised (De Veirman et al., Citation2017), we see how these influential others seek subversive and emancipating outlets (Kozinets, Citation2002) to revert back to some of the rawer content and imagery (Reade, Citation2021) of their early days. Moreover, whereas previous theorising on Finstagram has suggested how secondary or alternative accounts exemplify ‘boundary work’ (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019), our data reveals a porosity across accounts, where differentiated narratives of authenticity bleed into various digital personae (Abidin, Citation2018b). Jade’s and Anastasia’s transparency regarding their dual-account personae opens followers’ eyes to the performativity of it all.

Conclusion

Studies on authenticity are plentiful in the social media marketing literature (Lim et al., Citation2015; Reade, Citation2021), with a keen focus on influencers as authentic content-creators (Abidin, Citation2017, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Duffy & Hund, Citation2019). Marketers are drawn to influencers who espouse authenticity (Schouten et al., Citation2020) for a more credible endorsement of their brands; followers get lured in by the confessional ‘mediated intimacies’ of influencers (Patterson & Ashman, Citation2020), whose ‘real talk’ (Reade, Citation2021) fosters connectivity between them and their followers (Yuan & Lou, Citation2020); and the platform itself has heralded authenticity as a key feature since its launch over a decade ago (Duffy & Hund, Citation2019).

Despite this thirst for authenticity, social media scholars have questioned the performativity of authenticity on digital platforms vis à vis our ‘real’, embodied, offline reality (Schultze, Citation2014). Bridging this performativity beyond the confines of physical or digital spaces, Abidin (Citation2018b) argues that all presentations of our selves – á la Goffman (Citation1990) – are in fact ‘curated and controlled’, so that authenticity becomes part of a ‘performative ecology’ (Abidin, Citation2018a, p. 91), with leakage between presentations of digital and material selves. This leakage is supported by findings from this study which demonstrate the ‘porous authenticity’ (Abidin, Citation2018a) afforded through use of secondary accounts whereby both content and narratives bleed in Finsta and main accounts. We therefore extend De Veirman et al.’s (Citation2017) work on the confluence of offline lives into online personae towards a more intrinsic ‘bleeding’ between online profiles as a means of escaping the authenticity bind (Marwick, Citation2016).

However, as influence grows, influencers’ perceived authenticity dwindles (Park et al., Citation2021), given that their digital labour becomes thwarted by the platform’s algorithm (Gillespie, Citation2014; Noble, Citation2018), the socially mediated expectations followers have of them (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019; Elias & Gill, Citation2018) and the strictures of the commercially viable self (Duffy, Citation2019) they have created. In the wake of recent influencer resistance strategies (Cotter, Citation2019; Fiers, Citation2020; O’Meara, Citation2019) that either circumvent or manipulate the platform’s technological affordances (Davis & Chouinard, Citation2016; Hurley, Citation2019) in the hope of performing more authentically, our study homes in on the rising phenomenon of Finstagramming as a subversive and emancipatory escape (Kozinets, Citation2002) from the pressures of the attention economy (Marwick, Citation2015), whilst remaining firmly embedded in the dynamics of the platform. We have unearthed how influencers strategically toggle between their main and Finsta accounts, crafting differentiated digital personae for themselves, and how the emancipatory space (Kozinets, Citation2002) of Finstagram enables various authenticity markers (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017) to emerge all at once: a more spontaneous, less prescribed creativity that looks and feels more genuine (Davis, Citation2014) to those few allowed in. Unencumbered by trying to win at a ‘visibility game’ (Cotter, Citation2019) these outlets express more (seemingly) authentic narratives to audiences they feel care, so that in a way Finsta accounts appear to hark back to the early days of influencers’ digital labour and limited visibility. Although authenticity remains a resonant ideal within influencer circles (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017), the balancing act of projecting themselves as ‘real’ (Abidin, Citation2016) whilst adhering to the tenets of online self-branding (Duffy, Citation2019) is mediated through the use of these Finstagram accounts.

As emancipatory spaces (Kozinets, Citation2002), Finsta accounts can be seen as subversive to the picture-perfect tales being told on influencers’ main accounts (Ross, Citation2019): the aesthetic labour appears less calibrated and more ‘raw’ (Reade, Citation2021) when compared to the highly polished visual identities of their main accounts. Moreover, thanks to the intimacy of this smaller, more exclusive communitas (Kozinets, Citation2002), Finstagrammers enact ‘deeper’ acting (Hochschild, Citation1983) in their emotional labour with followers, thus encouraging more meaningful ‘affective encounters’ with their followers (Drenten et al., Citation2020; Reade, Citation2021).

Discursively, influencers posted richer captions, wrote extensive biographies some of which tapped into deeper vulnerabilities and made use of their handles to be more creative, light-hearted or seemingly genuine. Visually, we saw greater use of filter or edit-free images, live content and photography that appeared to align more with their passions. We therefore contribute to Cotter’s (Citation2019) notion of a visibility mandate, as we unpacked the impression of ‘realness’ prevalent on these alternative Instagram accounts. In furthering our understanding of influencer resistance strategies, we respond to Fiers (Citation2020) call for further research into ‘the prevalence of like hunting and the hiding thereof’ of the status-seeking strategies on Instagram (p. 10). In their pursuit to perform more authentically, influencers manipulate the multi-account affordance of the platform, whereby they paradoxically navigate the visibility game (Cotter, Citation2019) in their favour through the strategy of embedded escapism. This echoes similar accounts of the market, where consumers flee market dynamics whilst being entrapped by this very logic (Kozinets, Citation2002). We reveal how in their uptake of Finstagramming, influencers are not in fact evading the attention economy (Marwick, Citation2015) nor throwing in the towel of the visibility game (Cotter, Citation2019). Instead, they strategically leverage authenticity across their multi-person ecosystem. Expanding on Abidin’s (Citation2018b) notion of ‘layered identity’, we suggest layers of authenticity being performed and leveraged across the platform’s multi-account affordance, and similar to Abidin’s move beyond dichotomies of reality (offline selves) and falsity (online selves), we suggest that Rinstagram and Finstagram afford influencers varying degrees of authenticity, so that through their aesthetic, emotional and connective work, influencers make their digital personae look and feel (Davis, Citation2014) more or less ‘real’.

We saw how in their main accounts, influencers were able to safeguard their lucrative, monetised selves (Duffy, Citation2019; Duffy & Hund, Citation2015; van Dijck, Citation2013) through the aesthetic work they perform, whereas in their Finsta accounts they safeguard more intimate portrayals of themselves free from the surveillant gaze (and judgement) of the market (Duffy & Chan, Citation2019; Haenlein et al., Citation2020). Finsta accounts provide influencers with the necessary breathing space to develop their online identity, thus escaping from the inherent platform restrictions on what, how and when to post content (Ross, Citation2019). Content appeared more creative and experimental, as well as spontaneous, on these profiles. The pressures to conform to social media expectations (Elias & Gill, Citation2018) lightened, even allowing influencers to diversify into different genre types, without ever jeopardising their main account (and livelihood). In addition to aesthetic labour, we see emotional work foregrounded in these alternative accounts, whereby influencers can make more genuine and personalised connections (Drenten et al., Citation2020) and reveal more vulnerable sides of themselves to others (Haenlein et al., Citation2020). In doing so, they make the connections with followers appear more genuine whilst rocketing their engagement rates. This shift to smaller-scale accounts with fewer (but more engaged) followers suggests that influencer growth is not as linear as we once thought (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020), with a taken-for-granted progression from nano to micro, micro to mid-tier, mid-tier to macro and so on, escalating self-commodification (see Drenten et al.’s (Citation2020) influencer typology progressing from affiliation- to access-based labour). Instead, profile-toggling reveals how influencers not only dabble in different content, tone, moods, genres and typologies, but also in different rankings, whereby the ability to downscale becomes an indication of social media worth. Our study therefore contributes to theorising on identity construction (Hurley, Citation2019), not least identity bleeding, where we see how navigating across (and through) different profiles on the same platform affords diverse presentations of the self (Van Dijck, Citation2013) and also new forms of influencer marketing.

In practical terms, the heightened engagement levels found on ‘Finstagram’ can act as barometers for influencer marketers in their search for suitable endorsers (Schouten et al., Citation2020), so that paradoxically whilst Finsta accounts are more removed from the market they can be key tools for the assessment of influencers’ (monetary and symbolic) worth. We saw from the data how the digital personae of these multiple accounts bled into one another, if we recall how some influencers included ‘shout-outs’ to their other profiles, endorsing their various identities. As such, influencer marketing managers can use alternative accounts to gain more information about an influencer’s skills, values, and identity, assessing their suitability and marketability for certain brands and audiences. Profile-toggling – as a social media phenomenon – allows marketing managers to reduce risk when hiring an influencer for an endorsement campaign in an over-saturated market.

Future research

Methodologically, this study tells the story of influencers’ pursuit of authenticity through Finstagramming from a producer’s perspective. Future research on the phenomenon could tell the consumers’ side of this tale, unravelling how authenticity, credibility and relatability are experienced (and interpreted) by followers. Given that some influencers use their alternative account to share more ‘real’, light-hearted content, further research could examine how influencers’ use of humour impacts their relatability in their alternative accounts. Recent research has foregrounded the more confessional tone that influencers adopt in their tales of body transformation (Rodner et al., Citation2022) and physical and emotional recovery (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019). Further research could delve deeper into the waters of Finstagram to examine tales of vulnerability shared with intimate audiences, and how this emancipatory space (Kozinets, Citation2002) nourishers users’ well-being as well as their creative authenticity.

Additionally, whether or not these more intimate accounts of influencers’ lives become monetised (Duffy, Citation2019) needs further examination. Will a tsunami of brands flood this seemingly subversive, emancipatory space? Or will these ‘raw’ accounts (Reade, Citation2020) remain less commercialised compared to main accounts and thus continue to be an outlet for momentary escape? Broadening our horizons beyond the borders of Instagram, further research on profile-toggling could extend to platform-switching or media-switching as a phenomenon, where influencers navigate various social media platforms (e.g. TikTok, YouTube, etc) in their crafting of authenticity. We must also turn our attention to a new era of influencers, such as kidfluencers (Wong, Citation2019), petfluencers (Maddox, Citation2020), and even virtual influencers (Robinson, Citation2020), to better understand how they perform authenticity on one or multiple accounts. These new breeds of influential others offer insight into matters of authenticity, connectivity and relatability, and the agency of their storytelling (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019), all of which merit our attention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amy Goode

Dr Amy Goode is a Lecturer in Marketing at the Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow (UK). Amy completed her PhD in Marketing at the University of Strathclyde and her research and teaching interests are in digital marketing, consumer behaviour and consumer culture. She is currently working on a number of projects relating to these areas specifically exploring: influencer marketing, communities of consumers, socialbots and consumer vulnerability. Amy has published her work in the European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Services Marketing and Advances in Consumer Research. She recently secured funding from the Academy of Marketing Research Council and is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Victoria Rodner

Dr Victoria Rodner is a Lecturer in Marketing at the University of Edinburgh (UK) and her main research areas include branding, consumer narratives including digital identity projects, institutional change, value creation in the visual arts market, and religiosity and spiritual consumption. She is currently working on studies of embodiment, atmospheres, (consumer) agency, and affect theory. Some of her recent work has focused on the phenomenon of spirit possession and mediumship in the context of Brazil. Victoria is a qualitative researcher and has a keen interest in grounded theory, embodied research, video-methodologies and personal introspection methods including poetry. She publishes in marketing, management, and sociology journals including Academy of Management Journal, Annals of Tourism Research, Marketing Theory, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Services Marketing, Journal of Marketing Management among others. She is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Matilda Lawlor

Matilda Bea Lawlor, graduate of University of Edinburgh, is a London-based freelance content creator who shares her daily life on TikTok & Instagram (@matildabeaa). From throwing her friends the ultimate Galentine’s brunch, to creating an aesthetic low-key table setting for date night, the TikToker has become the un-official queen of hosting. Her work has been featured in Cosmopolitan and Sheer Luxe & she has worked with many household names including Starbucks, CeraVe, Magnum, L’Oreal and more.

Notes

1. New Zealand singer-songwriter Lorde, for instance, was verified as posting under the Finstagram handle @onionringsworldwide, whereas many other celebrity fake accounts remain unverifiable (Morgan, Citation2021).

2. We see how many smaller-level players, have flooded the platform, driven by the commerciality of becoming ‘Instafamous’ (Djafarova & Trofimenko, Citation2019), where a single post by influencers with 10,000 followers can earn £100 (Mackay, Citation2018).

3. The sample of influencers comprising our netnography was made up of a wide typology, including lifestyle, fashion, fitspo (from the buzzword ‘fitspiration’, a portmanteau of ‘fitness’ and ‘inspiration’), photography, food, and specialist knowledge (e.g. cars) influencers. For our interview data, influencers’ expertise ranged from fitspo, photography and cars in their main profiles, and fitspo and personal narratives in their Finsta accounts.

References

- Abidin, C. (2015). Communicative ❤ intimacies: Influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, (8). http://dx.doi.org/10.7264/N3MW2FFG

- Abidin, C. (2016). Visibility labour: Engaging with influencers’ fashion brands and #ootd advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia, 161(1), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X16665177

- Abidin, C. (2017). #familygoals: Family influencers, calibrated amateurism, and justifying young digital labor. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117707191

- Abidin, C. (2018a). Internet celebrity: Understanding fame online. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787560765

- Abidin, C. (2018b, April 16). Layers of identity: How to be ‘real’ when everyone is watching. Real Life. Retrieved December 24, 2020, from http://reallifemag.com/layers-of-identity/

- Aslam, S. (2021). Instagram by the numbers (2021): Stats, demographics & fun facts. Retrieved January 23, 2021, from https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/

- boyd, d. (2010). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites (pp. 39–58). Routledge.

- Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory. Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003

- Carrasco-Polaino, R., Villar-Cirujano, E., & Martín-Cárdaba, M. (2018). Artivism and NGO: Relationship between image and ‘engagement’ in Instagram. Comunicar, 26(57), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.3916/C57-2018-03

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.005

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Citton, Y. (2017). The ecology of attention (B. Norman, Trans.). Polity Press.

- Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media & Society, 21(4), 895–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818815684