ABSTRACT

With a shared focus on resiliency, agency, and pro-sociality, environmental education and positive youth development (PYD) have numerous intersections. Recognizing and supporting this synergy can help both fields achieve their goals, namely increased pro-environmental action and improved youth outcomes. To better understand this convergence, we undertook a systematic review to explore what environmental education outcomes reported in the peer-reviewed literature support PYD. We searched empirical research and identified 60 relevant studies. Qualitative coding revealed environmental educators are supporting PYD with a range of audiences and in varied settings via documented outcomes from all categories of the 5Cs model of PYD: competence, confidence, connection, character, and caring. Analysis revealed eight programme strategies and approaches that support PYD outcome development, including incorporating meaningful daily-life connections; emphasizing student-centred activities; and building in opportunities for teamwork, environmental action, and experiential learning. We conclude with research and practice implications for PYD and environmental education.

Introduction

Young people today are growing up in a world rife with opportunities and challenges. To help support youth as they leverage those opportunities and face those challenges, families, educators, community organizations, and policymakers may turn to the principles and practices of positive youth development (PYD). PYD is an asset-based approach that aims to optimize the wellbeing of young people as they address the complex landscape of today’s and tomorrow’s world (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Citation2002). Although various conceptual frameworks and definitions are proposed for understanding and operationalizing PYD, several core concepts are primary, including emphasizing assets, strengths, human plasticity, personal competencies, and supportive contexts (Arnold & Silliman, Citation2017; Burkhard et al., Citation2020; Lerner, Citation2017; Lerner et al., Citation2011; Shek et al., Citation2019). One of the best-known and most empirically supported PYD frameworks is the 5Cs model (Dvorsky et al., Citation2019; Geldhof et al., Citation2015; Shek et al., Citation2019), which emphasizes the following outcomes: competence, confidence, connection, caring, and character, which together give rise to contribution (Lerner et al., Citation2005).

In addition to focusing on young people’s assets, PYD considers the context and type of settings that enable youth to develop those assets. The National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (Citation2002) have compiled setting characteristics that promote PYD (see, ), emphasizing physical aspects (e.g. safety considerations), emotional aspects (e.g. settings that facilitate positive and supportive relationships with peers and adults), and community-focused aspects (e.g. settings that contribute to the community and connect with broader resources). PYD settings can be developed through targeted programmes and by creating supportive environments (Acosta et al., Citation2021). Researchers have investigated specific contexts, such as youth sports (Bruner et al., Citation2021) and the arts (Elpus, Citation2013; Haglund et al., Citation2021), as avenues to achieving PYD outcomes (Larson, Citation2000; Waid & Uhrich, Citation2020). Environmental education is another avenue towards PYD and, given what has often been recognized by educators, scholars, and policymakers as a natural alignment between environmental education and PYD, connecting these fields has the potential for impactful synergy.

Table 1. Features of Positive Youth Development Settings (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Citation2002, pp. 7–10).

Environmental education is a dynamic, interdisciplinary field based on principles of informed decision-making and action at the individual and collective scales (Ardoin et al., Citation2020; Clark et al., Citation2020). The Tbilisi Declaration, produced by an intergovernmental consortium commissioned by the United Nations in 1977, describes the essential elements of environmental education as including environmental awareness, knowledge, attitudes, skills, and citizen participation (UNESCO, Citation1978). Relatedly, the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE), a premier backbone organization of the environmental education field, describes an environmentally literate person as ‘someone who, both individually and together with others, makes informed decisions concerning the environment; is willing to act on these decisions to improve the wellbeing of other individuals, societies, and the global environment; and participates in civic life’ (Hollweg et al., Citation2011, pp. 2–3). Environmental education programmes showcase diversity in form and function with a range of settings, topics, audiences, structures, and effective practices (Ardoin et al., Citation2018). Examples of environmental education include an early childhood programme during which a caretaker guides children on a hike through a local park; an after-school environmental club during which students learn about pollution in a local river and develop an action plan to address the issue; an educational programme at an aquarium where families learn about threats to biodiversity and what they can do to help; and a community outreach programme where adults learn about water conservation and undertake activities such as building a rain barrel. Notably, environmental education can and does include audiences of all ages in a variety of settings, from formal to informal and indoor to outdoor, and with a range of intended environmental and sustainability-related outcomes (Clark et al., Citation2020; Monroe et al., Citation2008).

Environmental education researchers have discussed the overlap between environmental education and PYD, noting a substantial number of shared goals, practices, and outcomes (e.g. Barnason et al., Citation2022; Delia & Krasny, Citation2018; North American Association for Environmental Education, Citation2022; Russ, Citationn.d.; Schusler, Citation2013; Schusler et al., Citation2017; Schusler & Krasny, Citation2010). Moreover, as discussed in a review of mission statements of residential environmental education programmes, many such programmes strive to promote personal growth, social skills, and the development of community among learners (Ardoin et al., Citation2015), indicating that an intentionality exists to develop competencies like those often addressed in PYD. Despite the emerging discussion and evidence of convergence among the core components of environmental education with those of PYD (see, ; see also, Schusler, Citation2013, , p. 108), environmental education practitioners and researchers have yet to enter the broader conversation on PYD, at least in a prominent or consistent manner.

Table 2. Practices and Intended Outcomes of PYD and EE, Compared.

Review purpose

To more deeply understand the alignment between PYD and environmental education, we undertook a systematic review of both the PYD and environmental education literatures, in relation to each other. (See ‘Methods’ for a description of the terms used to guide the search.) We sought empirical, peer-reviewed studies that focused on environmental education programmes and reported outcomes related to PYD. The following questions drove our review:

What PYD outcomes of environmental education programmes for young people (ages 0–25) are reported in the peer-reviewed research?

What environmental education strategies appear to support the development of PYD outcomes?

Methods

To conduct this systematic review, we drew from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021) and suggested procedures for systematic reviews in the social sciences (Cooper et al., Citation2019; Gough et al., Citation2017). We worked with a library specialist at Stanford University, who provided feedback on our search terms and processes.

Searching the literature

We used the following seven EBSCOhost databases to search for relevant research: Academic Search Premier, Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), Environment Index, ERIC, Family & Society Studies Worldwide, GreenFILE, and Urban Studies abstracts. We selected these databases as they either indexed a range of academic journals or provided a focus on journals relevant to education, the environment, or youth development. To determine appropriate search terms and parameters, we conducted scoping searches to find the combination that would produce a broad yet relevant search resulting in a manageable number of citation records to screen. We also reviewed relevant studies with which we were already familiar to identify key search terms. Ultimately, we identified three sets of search terms, with each set focusing on a subject area (and related terms) relevant to our research questions and review purpose. (See, .) All search results had to contain at least one search term from each set.

Table 3. Search terms.

For search parameters, we limited our search to peer-reviewed research published in English between 2011 and 2021. (We conducted the search in March 2021.) The search returned 3,487 records, which were exported to Zotero, a bibliographic management programme. The EBSCOhost database and Zotero removed 1,236 duplicates, leaving 2,251 records to be screened for relevancy. (See, for the PRISMA flow diagram.)

Based on our familiarity with environmental education research, we recognize high-quality work examining PYD-related environmental education programmes exists in venues outside of traditional, peer-reviewed academic outlets (i.e. grey literature [Alexander, Citation2020]). In prior reviews we have conducted, however, we found that challenges exist in pursuing an efficient, effective, and systematic search of the environmental education grey literature, a common barrier when working with grey literature writ large (Godin et al., Citation2015; Mahood et al., Citation2014). As such, in this review, we focused on peer-reviewed research, but note constraints related to this decision in this paper’s Limitations section.

Screening Results for Relevancy and Quality

For the first round of screening, two research team members developed a list of exclusion criteria to be applied to each record after reviewing the title and abstract. The first criteria eliminated studies that were not in English, peer-reviewed, or empirical. Studies were then excluded if they did not present findings related to the implementation of an environmental education programme for youth (ages 0–25). We used the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (Citation2021, para. 1) definition of environmental education: ‘Environmental education (EE) is a process that allows individuals to explore environmental issues, engage in problem solving, and take action to improve the environment. As a result, individuals develop a deeper understanding of environmental issues and have the skills to make informed and responsible decisions.’ We also referred to language used to describe environmental education in the foundational Tbilisi Declaration (UNESCO, Citation1978), as well as descriptions of environmental education provided by the North American Association for Environmental Education (Citationn.d.). Finally, we excluded studies that did not include findings related to PYD outcomes in youth. We defined PYD outcomes broadly and used multiple resources (e.g. Catalano et al., Citation2004; Lerner et al., Citation2005; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Citation2002; Pittman et al., Citation2003; Schusler, Citation2013) to determine youth outcomes commonly associated with PYD programmes (see, ). Applying these criteria resulted in the exclusion of 1,890 records, leaving 361 records advancing to the next round of screening.

Table 4. Suggested Positive Youth Development outcomes used in the screening process.

In the second round of screening, we retrieved the full text of all 361 records and assessed the 361 full-text articles for eligibility (i.e. inclusion in the final review sample). In this round, three research team members reviewed the full-text and applied the same exclusion criteria used in the first screening round. In addition, we applied straightforward quality criteria, which asked team members to ensure each study provided (1) sufficient description of methods, tools, and measures and (2) clear-cut data to support claims about PYD outcomes. We excluded instrument development papers unless the papers included an equal focus on the intervention and its connection to the measured outcomes. We also excluded studies in which researchers measured outcomes only via secondary sources (e.g. asking educators and parents to report changes in youth outcomes). After this second round of screening, we identified 60 studies that reported on high-quality research of PYD outcomes in youth following participation in an environmental education programme. Included studies did not have to report only positive outcomes; i.e. we also included studies reporting null or negative findings. (See Appendix for a bibliography of the 60 studies.)

A major challenge for the screeners was that many empirical studies addressing the effectiveness of environmental education report changes in environmental knowledge or environmental action. In theory, these outcomes could be classified as PYD outcomes as they represent cognitive and behavioural development. Our intent, however, was to focus on studies that reported outcomes beyond traditional, common environmental education outcomes, such as increased environmental knowledge, connection to nature, environmental awareness, pro-environmental attitudes, and environmental behaviour and action. We excluded studies that only presented findings for these types of outcomes.

Coding and analysis

We used NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software tool, to code and analyse the 60 studies. We developed a preliminary codebook to provide basic structure for the coding process and help ensure consistency between coders. The codebook contained five main categories of codes: article information, study information, programme information, programme strategies, and programme outcomes. See, for details about what each coding category entailed. Two research team members served as coders and used a combination of inductive and deductive coding for the initial open coding (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014; Miles et al., Citation2014). The initial coding resulted in codes that we then organized into logical and emergent coding categories. For some coding, like that of participant age and data collection methods, codes could be organized into discrete categories (e.g. high school age or 14–18 years old for participant age; surveys for data collection methods). For programme strategies, initial codes were grouped together based on commonalities. For example, the initial codes of ‘action research project’ and ‘community engagement’ were grouped into an emergent category of Taking Action.

Table 5. Five main coding categories of the codebook used for initial coding.

Programme outcomes were coded as either PYD outcomes or non-PYD outcomes, with preliminary codes provided for PYD outcomes (see, ). After initial coding of PYD outcomes, we used the 5Cs model (Lerner et al., Citation2005) to organize the long list of initial PYD outcome codes. The 5Cs model is one of the most commonly used PYD frameworks (Dvorsky et al., Citation2019; Shek et al., Citation2019) and appropriately captured and accounted for the PYD outcomes that emerged in our reviewed studies. The codes for PYD outcomes were placed into one of the 5C categories of competence, confidence, caring, character, and connection. We used Lerner et al.’s (Citation2005) definitions of the 5Cs to guide the categorization of each code (see, ). Finally, given the range of methods used to measure outcomes and the large number of outcomes reported, we coded for overall level of findings (positive, negative, null, or mixed) for each study rather than coding findings for individual outcomes. If a study only reported positive outcomes, for example, we coded it as having ‘positive findings,’ but if a study reported both null and positive findings, we coded it as mixed with an additional code indicating a mix of positive and null.

Table 6. Frequency of PYD Outcomes Based on the 5Cs Model (Lerner et al., Citation2005).

Findings

Article and study characteristics

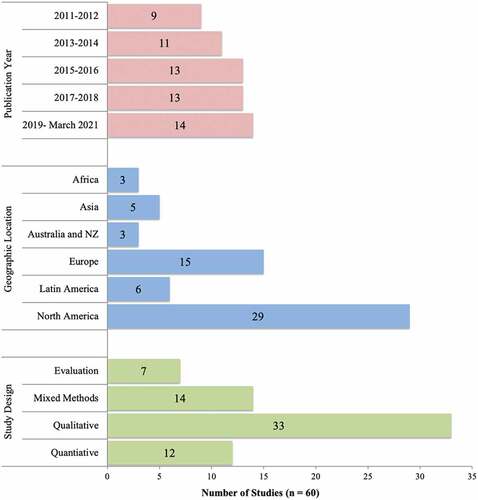

The 60 articles were published relatively evenly throughout the time period we examined, with a slight increase over the decade (see, ). The studies were published in a range of journals focused on education (e.g. International Journal of Science Education, Peabody Journal of Education), environment (e.g. Local Environment, Journal of Cleaner Production), and environmental education (e.g. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education). The two journals that were the most common sites of publication for articles in our sample were Environmental Education Research (n = 13) and The Journal of Environmental Education (n = 10).

The 60 studies employed a range of research designs and approaches (see, ). We coded over half of the studies (n = 33) as using a qualitative research design, adopting naturalistic approaches such as case studies, action research, arts-based research, community-based research, ethnography, and critical theory. Researchers used a quantitative design in 12 studies, and those studies often involved quasi-experimental research with pre- and post-tests. We coded 7 studies as having an evaluation design with a focus on providing evaluative data for programme developers and providers to gauge the effectiveness of an environmental education programme.

Researchers reported using a mixed-methods approach in 14 studies. Similarly, data collection methods varied across the 60 studies. Qualitative data collection included tools such as observation, interviews, and focus groups. Quantitative measures included various types of surveys, questionnaires, and scales. Less-frequent collection methods included analysis of student work, photo elicitation, word association, visual mapping, and repertory grids.

Most of the studies (n = 49) presented findings from a single environmental education programme. Ten studies reported on multiple programmes, with nine of those presenting data from 2 to 6 programmes, and 1 study (Dale et al., Citation2020) combining data from 334 programmes.

Geographically, the environmental education programmes under study occurred across the world (see, ). Many took place in North America (United States and Canada, n = 29) and Europe (n = 15). The most frequent country of focus was the United States (n = 24), followed by Canada (n = 5), Greece (n = 3), and the United Kingdom (n = 3).

Participant characteristics

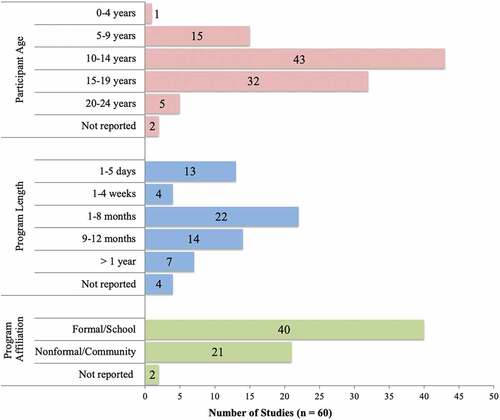

Across the 60 studies, researchers reported a range of data about programme participants. All but two studies clearly described the age range of participants (see, ). Most participants were young people of secondary-school age with 32 studies reporting participants aged 15 to 19 and 43 studies reporting participants aged 10 to 14. Other demographic data for participants was less consistently reported, although several studies reported information about geographical density (i.e. placement on urban–rural continuum), race and ethnicity, and socio-economic status; diversity occurred in these categories, with no one class, race, or location dominating.

Programme characteristics

In terms of programme length (see, ), most programmes lasted between one and eight months (n = 22) or the length of a school year (n = 14; approximately nine to twelve months). Researchers frequently reported that, while programmes lasted several months, the participants were not exposed to the programmes daily; rather, programme implementation occurred less frequently, often on a weekly basis. We coded whether the programmes were part of formal education (i.e. school-based or sponsored by the school system) and found 40 studies reported on formal programmes. Twenty-one studies examined environmental education programmes presented by organizations such as local parks or non-profit organizations.

Programme outcomes

To be included in the final review sample, a study had to report at least one PYD-related outcome. We coded 32 studies as also reporting outcomes not related to PYD. In all cases, these outcomes were related to the environment and included outcomes such as environmental awareness, environmental knowledge and understanding, pro-environmental attitudes, environmental action and behaviour, environmental identity, and connection to nature.

The focus of this review was on PYD outcomes, and we organized reported PYD outcomes using the 5Cs model that emphasizes the outcomes of competence, confidence, connection, character, and caring (Lerner et al., Citation2005). provides data on how many studies reported each PYD outcome category and provides examples of the individual codes assigned to each coding category. While outcomes were reported in all 5 categories, researchers most frequently reported outcomes in the categories of Competence (n = 40) and Confidence (n = 33). We also coded for the level of findings reported for PYD outcomes. All 60 studies reported some level of positive findings for PYD outcomes.

Programme strategies and approaches

Initially in the coding process, we attempted to identify programme strategies explicitly linked to increases in PYD outcomes; however, because PYD was often not the focus of the study or program, such connections between practice and PYD were rarely explicit. As all 60 studies in the final sample reported at least some positive findings for PYD outcomes, we examined reported programme strategies for common educational practices that indicated potential practices supporting PYD. Those practices included, primarily, emphasizing relevance through creating meaningful connections to the daily lives of young people (e.g. Selby et al., Citation2020; Stapleton, Citation2019) and occurring in nature-rich, outdoor settings (e.g. Fröhlich et al., Citation2013; Garip et al., Citation2021; Lithoxoidou et al., Citation2017). Also important to PYD outcomes were programmes that were not only youth-centred, but especially those that were youth-led (e.g. Caiman & Lundegård, Citation2014) and those that provided opportunities for teamwork and collaboration (e.g. Allen & Elmore, Citation2012; Briggs et al., Citation2019; DuBois et al., Citation2018). Programmes focused on directly incorporating action and action strategies were also likely to support PYD outcomes (e.g. Blanchet-Cohen & Di Mambro, Citation2015; Meza Rios et al., Citation2018) as were those that provided explicit, direct instruction related to targeted knowledge, dispositions, and skills (e.g. Cincera & Simonova, Citation2017; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi et al., Citation2015). Finally, programmes that were interdisciplinary and holistic, incorporating aspects not only of science and engineering along with the environmental focus, but also the humanities, were more likely to result in PYD-related outcomes (e.g. Tsevreni, Citation2011; Tuntivivat et al., Citation2018). (See, .)

Table 7. Programme Strategies and Approaches to Support PYD in Environmental Education.

Discussion

We conducted this systematic review of research to explore the intersection of PYD and environmental education. After searching the literature using academic databases and screening the results, we identified 60 studies that fit our final review sample criteria. Similar to the field of PYD research, a number of studies were concentrated in the United States (Shinn & Yoshikawa, Citation2008) and demonstrated that PYD-related environmental education occurs in both school and community (or formal and informal) settings (Wiium & Dimitrova, Citation2019). Analysis of the coded studies addressed our primary research questions, which inquired what PYD-related outcomes of environmental education programmes are reported in the empirical, peer-reviewed literature and what programmatic strategies and approaches appear to support the development of those outcomes.

Although focused on PYD-related outcomes, we also coded 32 studies as reporting a range of environmental outcomes, such as increased environmental knowledge and the development of pro-environmental attitudes. Additionally, while many of the other studies reported environmental outcomes, they were coded as PYD-related outcomes. This demonstrates the inherent overlap of PYD and environmentally related outcomes and thus the difficulty we experienced when coding exclusive outcomes. It was challenging to parse reported outcomes, forcing them into a dichotomy between environmental outcomes and PYD outcomes. For example, we coded outcomes such as decision making, leadership development, and critical thinking as ‘PYD outcomes,’ even though skills and knowledge are also important in the development of an environmentally active citizen, which is the ultimate goal of environmental education. While such nuance is problematic for coding into discrete categories of outcomes, it is a positive sign of the synergy between environmental education and PYD and a reflection of similar goals.

In terms of PYD outcomes, we found that all reviewed studies reported some level of success in contributing to PYD. Using Lerner et al.’s (Citation2005), 5Cs model of PYD to organize the PYD outcomes, our findings indicated environmental education programmes may facilitate the development of all 5Cs. Our findings suggest environmental education programmes may be particularly effective at achieving the competence and confidence outcomes, with over half of the reviewed studies reporting outcomes in these two PYD categories, although the large number of studies coded to the competence category may also reflect the broad nature of that category. Lerner et al.’s (Citation2005) definition of competence includes development in several domains, including academic, social, cognitive, and vocational. As discussed in the previous paragraph and the introduction (see, ), we noted a great deal of overlap among environmental and PYD outcomes. Many of the outcomes environmental educators believe lead to environmental literacy and action align with desired PYD outcomes, and this appears to be reflected in the empirical findings of the reviewed studies. Environmental educators aim to improve skills such as communication, critical thinking, and decision making (competence); develop a sense of moral and ethical consideration (character); increase self-efficacy and agency (confidence); and build social capital (connection).

The least frequently documented category in this review – that of ‘caring’ – may be undercounted as Lerner et al.’s (Citation2005) definition of caring focuses on care for human beings, rather than care for the broader (human and more-than-human) world, which is a more-common framing in environmental education. Although we documented a handful of studies (n = 7) that reported outcomes demonstrating care for other humans, many more environmental education programmes also strive to develop care for nature, other animals, and the environment. If the category of caring were to be expanded to include care for more-than-human entities (e.g. other animals and nature writ large), the number of environmental education studies reporting outcomes related to the PYD outcome of caring would certainly increase.

Our second research question queried programme strategies that support the development of PYD outcomes. As part of the coding process, our team attempted to focus on text in each study where researchers linked certain programme practices to PYD outcomes. Because we found little discussion explicitly linking practices and PYD outcomes, we expanded our coding to include the major practices emphasized as critical to the described environmental education programme. We organized the coded practices into emergent categories (see, ) with the intent of guiding practitioners as they develop and implement environmental education programmes in support of PYD. At this stage, these practices serve as a starting point for research and practice seeking to connect environmental education programme strategies and PYD. Further research opportunities exist to explore and examine these links.

Even in the absence of conclusive evidence that the identified environmental education practices lead specifically to PYD-related outcomes, the described practices represent often-documented effective approaches identified in the field of education in general, and environmental education and PYD programming in particular (e.g. Ardoin et al., Citation2020; Lerner et al., Citation2011). The aforementioned strategies also align with practices in fields related to environmental education, such as outdoor education, adventure education, and experiential education, which practitioners and researchers have also previously linked to positive youth development (Sibthorp, Citation2010).

Implications for practice and research

Looking across the findings from this review, we see clear evidence for past and future synergy between PYD and environmental education, in both practice and research. Our review makes evident that environmental education programmes can be structured and implemented in ways that support PYD. For youth practitioners, our findings serve as an invitation to explore environmental education as a programme format to develop PYD-related outcomes in young people. With its relevancy to universal yet local issues, environmental education can be a naturally engaging context for young people. As they explore the environment and develop fundamental skills, knowledge, and dispositions to address and solve sustainability issues, young people tap into their assets and potentialities to optimize personal wellbeing, the driving goal of PYD (Benson et al., Citation2007; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Citation2002). Drawing on psychological roots, environmental education’s ultimate goal is to create environmentally literate citizens who contribute to the wellbeing of the environment, mirroring the idea of contribution, the ultimate goal of the 5Cs model supported by the outcomes of competence, confidence, connection, character, and caring (Lerner et al., Citation2005). To assist practitioners as they adopt, or continue using, environmental education in their work, our review also surfaced eight practices (see, ). Incorporating as many of these strategies and approaches as possible into youth environmental educational programming may help develop PYD-related outcomes.

While linking environmental education and PYD is not a new idea in environmental education research (e.g. Barnason et al., Citation2022; Delia & Krasny, Citation2018; Schusler & Krasny, Citation2010), this review suggests the discussion is no longer about proving a connection between environmental education and PYD, but rather about how to further this connection in a way that enhances both environmental and PYD outcomes. Our findings focus on how environmental education can support PYD goals, with a mention of how the reviewed studies also reported evidence for environmental outcomes. More research is needed to focus on this flipside: how PYD programming can support environmental outcomes. Additionally, the identified strategies for environmental education programmes to contribute to PYD () represent a starting point for understanding the mechanisms and processes of environmental education that lead to PYD. Further research is also needed to confirm and refine these strategies. Finally, the field of PYD continues to evolve, including recent work to expand the measurement of PYD using the 5Cs model (Geldhof et al., Citation2015) and advance PYD research from diverse geographic regions (Dimitrova & Wiium, Citation2021), leading to the need for environmental education researchers to strive to remain up-to-date and aware of new directions in PYD research.

Limitations

As with any systematic review, the findings of this review should be interpreted and considered while acknowledging limitations and delimitations of the process. Although we attempted to be broad in our search, we certainly missed or unwittingly excluded relevant studies. For practical reasons, we limited our search to research published in English over the last decade (from 2011 to 2021). There are studies in other languages or published prior to 2011 that could contribute additional evidence or offer a contrary perspective. Additionally, we recommend future work to identify and examine the PYD-related grey literature in environmental education. Including work such as dissertations, reports, evaluation and assessment documents, conference presentations, and other items available outside of traditional academic journals can provide varying perspectives, while also addressing issues of search and publication bias (Suri, Citation2020). Finally, the positionality of our research team, a team with decades of experience in environmental education and situated at a U.S.-based university, impacted how we searched, screened, coded, and interpreted the relevant research.

Conclusion

Today’s young people are coming of age against a backdrop of questions around social and environmental justice that place many communities in harm’s way. In the sustainability space, we are experiencing greater climate vulnerability than ever before and, based on the rapid pace of biodiversity loss, many scientists predict we are on the precipice of the sixth mass extinction in planetary history (Barnosky et al., Citation2011). Difficult decisions face humanity with regard to the energy transition, as well as choices over agriculture, water quantity and quality, and inequitable distribution of food, among countless other challenges.

Yet we also live in an age, the Anthropocene, in which the human-induced nature of these issues brings the opportunity for people, particularly youth, to exert agency to address them. Local, regional, and even global-scale engagement has been increasing – as evidenced in the School Strike for Climate (SS4C) among other youth-led efforts – and young people are more motivated and energized than ever before to take action on issues of social and environmental justice, alternative energy, and more. Youth worldwide profess their eagerness to develop the knowledge and skills to create the world they wish to inhabit now and in the future. Environmental education offers ‘an approach, a philosophy, a tool, and a profession’ (Monroe et al., Citation2008, p. 205) to support this development, and this review provides evidence that environmental education can do even more than this: While helping youth improve the world in which they live, environmental education can also help young people leverage their assets to improve their own wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to our eeWORKS advisors for their insights during study conceptualization. We appreciate the research assistance provided by Estelle Gaillard during the initial scoping elements of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicole M. Ardoin

Nicole M. Ardoin, Emmett Faculty Scholar, is an associate professor at Stanford University where she runs the Social Ecology Lab. Her research addresses individual and collective environmental behaviour, especially as influenced by environmental learning and place connections.

Alison W. Bowers

Alison W. Bowers is a senior research associate in the Social Ecology Lab at Stanford University. She is interested in the scholarship of systematic reviews in environmental and sustainability studies as well as education, more broadly.

Archana Kannan

Archana Kannan is a PhD student in environmental and science education at the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University. Her research focuses on developing alternative assessments in environmental education and the role of technology in a range of outdoor and informal learning contexts.

Kathleen O'Connor

Kathleen O'Connor is a consulting researcher with the Social Ecology Lab at Stanford University and an evaluation and learning consultant with TCC Group. Her research interests include social and emotional learning among young people, evaluation of environmental education programs, and climate change education.

References

- Acosta, J. D., Chinman, M., & Phillips, A. (2021). Promoting positive youth development through healthy middle school environments. In R. Dimitrova & N. Wiium (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice in Global Contexts (pp. 483–499). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70262-5_32

- Alexander, P. A. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: The art and science of quality systematic reviews. Review of Educational Research, 90(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319854352

- Allen, K., & Elmore, R. D. (2012). The effects of the wildlife habitat evaluation program on targeted life skills. Journal of Extension, 50(1). eric. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1042364&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,sso&custid=s4392798

- Ardoin, N. M., Biedenweg, K., & O’Connor, K. (2015). Evaluation in residential environmental education: An applied literature review of intermediary outcomes. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 14(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2015.1013225

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2020). Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation, 241, 108224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., Roth, N. W., & Holthuis, N. (2018). Environmental education and K-12 student outcomes: A review and analysis of research. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49(1), 1–17.

- Arnold, M. E., & Silliman, B. (2017). From theory to practice: A critical review of positive youth development program frameworks. Journal of Youth Development, 12(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2017.17

- Barnason, S., Li, C. J., Hall, D. M., Wilhelm Stanis, S. A., & Schulz, J. H. (2022). Environmental action programs using positive youth development may increase civic engagement. Sustainability, 14(11), 6781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116781

- Barnosky, A. D., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S., Wogan, G. O. U., Swartz, B., Quental, T. B., Marshall, C., McGuire, J. L., Lindsey, E. L., Maguire, K. C., Mersey, B., & Ferrer, E. A. (2011). Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature, 471(7336), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09678

- Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., Hamilton, S. F., & Sesma Jr., A. (2007). Positive youth development: Theory, research, and applications. [Abstract]. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0116

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Di Mambro, G. (2015). Environmental education action research with immigrant children in schools: Space, audience and influence. Action Research, 13(2), 123–140.

- Briggs, L., Krasny, M., & Stedman, R. C. (2019). Exploring youth development through an environmental education program for rural Indigenous women. Journal of Environmental Education, 50(1), 37–51.

- Bruner, M. W., McLaren, C. D., Sutcliffe, J. T., Gardner, L. A., Lubans, D. R., Smith, J. J., & Vella, S. A. (2021). The effect of sport-based interventions on positive youth development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1875496

- Burkhard, B. M., Robinson, K. M., Murray, E. D., & Lerner, R. M. (2020). Positive youth development: Theory and perspective. In The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development (pp. 1–12). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119171492.wecad310

- Caiman, C., & Lundegård, I. (2014). Pre-school children’s agency in learning for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 20(4), 437–459.

- Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the united States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260102

- Cincera, J., & Simonova, P. (2017). “I am not a big man”: Evaluation of the issue investigation program. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 16(2), 84–92. eric.

- Clark, C. R., Heimlich, J. E., Ardoin, N. M., & Braus, J. (2020). Using a Delphi study to clarify the landscape and core outcomes in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 26(3), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1727859

- Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (Eds.). (2019). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (3rd ed.). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE.

- de Vreede, C., Warner, A., & Pitter, R. (2014). Facilitating youth to take sustainability actions: The potential of peer education. Journal of Environmental Education, 45(1), 37–56.

- Delia, J., & Krasny, M. E. (2018). Cultivating positive youth development, critical consciousness, and authentic care in urban environmental education. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2340.

- Dimitrova, R., & Wiium, N. (2021). Handbook of positive youth development: Advancing the next generation of research, policy and practice in global contexts. In R. Dimitrova & N. Wiium (Eds.), Handbook of positive youth development: Advancing the next generation of research, policy and practice in global contexts (pp. 3–16). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70262-5_1

- DuBois, B., Krasny, M. E., & Smith, J. G. (2018). Connecting brawn, brains, and people: An exploration of non-traditional outcomes of youth stewardship programs. Environmental Education Research, 24(7), 937–954.

- Dvorsky, M. R., Kofler, M. J., Burns, G. L., Luebbe, A. M., Garner, A. A., Jarrett, M. A., Soto, E. F., & Becker, S. P. (2019). Factor structure and criterion validity of the five Cs model of positive youth development in a multi-university sample of college students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(3), 537–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0938-y

- Elpus, K. (2013). Arts education and positive youth development: Cognitive, behavioral, and social outcomes of adolescents who study the arts (p. 56). National Endowment for the Arts. https://5y1.org/download/8be528ebbfdda10f0a4681abc60d28dd.pdf

- Fröhlich, G., Sellmann, D., & Bogner, F. X. (2013). The influence of situational emotions on the intention for sustainable consumer behaviour in a student-centred intervention. Environmental Education Research, 19(6), 747–764.

- Garip, G., Richardson, M., Tinkler, A., Glover, S., & Rees, A. (2021). Development and implementation of evaluation resources for a green outdoor educational program. Journal of Environmental Education, 52(1), 25–39.

- Geldhof, G. J., Bowers, E. P., Mueller, M. K., Napolitano, C. M., Callina, K. S., Walsh, K. J., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2015). The five Cs Model of positive youth development. In E. P. Bowers, G. J. Geldhof, S. K. Johnson, L. J. Hilliard, R. M. Hershberg, J. V. Lerner, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Promoting Positive Youth Development (pp. 161–186). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17166-1_9

- Godin, K., Stapleton, J., Kirkpatrick, S. I., Hanning, R. M., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2015). Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Systematic Reviews, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (Eds.). (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Haglund, K., Ortiz, A., De Los Santos, J., Garnier-Villarreal, M., & Belknap, R. (2021). An engaged community-academic partnership to promote positive youth development. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.54656/LNWP6978

- Hollweg, K. S., Taylor, J., Bybee, R. W., Marcinkowski, T. J., McBeth, W. C., & Zoido, P. (2011). Developing a framework for assessing environmental literacy: Executive summary. NAAEE. https://cdn.naaee.org/sites/default/files/envliteracyexesummary.pdf

- Lerner, R. M. (2017). Commentary: Studying and testing the positive youth development model: A tale of two approaches. Child Development, 88(4), 1183–1185. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12875

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdottir, S., Naudeau, S., Jelicic, H., Alberts, A., Ma, L., Smith, L. M., Bobek, D. L., Richman-Raphael, D., Simpson, I., Christiansen, E. D., & von Eye, A. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431604272461

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Lewin-Bizan, S., Bowers, E. P., Boyd, M. J., Mueller, M. K., Schmid, K. L., & Napolitano, C. M. (2011). Positive youth development: Processes, programs, and problematics. Journal of Youth Development, 6(3), 38–62. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2011.174

- Lithoxoidou, L. S., Georgopoulos, A. D., Dimitriou, A. Th., & Xenitidou, S. Ch. (2017). “Trees have a soul too!” Developing empathy and environmental values in early childhood. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 5(1), 68–88.

- Mahood, Q., Van Eerd, D., & Irvin, E. (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits: MAHOOD ET AL . Research Synthesis Methods, 5(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1106

- Meza Rios, M. M., Herremans, I. M., Wallace, J. E., Althouse, N., Lansdale, D., & Preusser, M. (2018). Strengthening sustainability leadership competencies through university internships. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(4), 739–755.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Monroe, M. C., Andrews, E., & Biedenweg, K. (2008). A framework for environmental education strategies. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 6(3–4), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15330150801944416

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10022

- North American Association for Environmental Education. (2022). Guidelines for excellence: Environmental education program (p. 110). North American Association for Environmental Education. https://naaee.org/our-work/programs/guidelines-excellence

- North American Association for Environmental Education. (n.d.). About EE and why it matters. NAAEE. https://naaee.org/about-us/about-ee-and-why-it-matters

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

- Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Hadjichambis, A. Ch., & Korfiatis, K. (2015). How students’ values are intertwined with decisions in a socio-scientific issue. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 10(3), 493–513.

- Pittman, K. J., Irby, M., Tolman, J., Yohalem, N., Ferber, T., & Forum for Youth Investment. (2003). Preventing problems, promoting development, encouraging engagement: Competing priorities or inseparable goals? The Forum for Youth Investment. http://dev.forumfyi.org/files/Preventing%20Problems,%20Promoting%20Development,%20Encouraging%20Engagement.pdf

- Russ, A. (n.d.). Positive youth development. In Environmental education in action: Learning from case studies around the world. Global Environmental Education Partnership. https://thegeep.org/sites/default/files/files/GEEP.PositiveYouthDevelopmentEBookChapter.pdf

- Schusler, T. M. (2013). Environmental action and positive youth development. In M. C. Monroe & M. E. Krasny (Eds.), Across the spectrum: Resources for environmental educators (pp. 94–115). North American Association for Environmental Education.

- Schusler, T. M., & Krasny, M. E. (2010). Environmental action as context for youth development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 41(4), 208–223.

- Schusler, T. M., Davis-Manigaulte, J., & Cutter-Mackenzie, A. (2017). Positive youth development. In Urban environmental education review (pp. 165–174). Cornell University Press.

- Selby, S. T., Cruz, A. R., Ardoin, N. M., & Durham, W. H. (2020). Community-as-pedagogy: Environmental leadership for youth in rural Costa Rica. Environmental Education Research, 26(11), 1594–1620.

- Shek, D. T., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Chai, W. (2019). Positive youth development: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 10, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S179946

- Shinn, M., & Yoshikawa, H. (2008). Toward positive youth development: Transforming schools and community programs. Oxford University Press.

- Sibthorp, J. (2010). A letter from the editor: Positioning outdoor and adventure programs within positive youth development. Journal of Experiential Education, 33(2), vi–ix. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382591003300201

- Stapleton, S. R. (2019). A case for climate justice education: American youth connecting to intragenerational climate injustice in Bangladesh. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 732–750.

- Suri, H. (2020). Ethical considerations of conducting systematic reviews in educational research. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research, 41–54.

- Tsevreni, I. (2011). Towards an environmental education without scientific knowledge: An attempt to create an action model based on children’s experiences, emotions and perceptions about their environment. Environmental Education Research, 17(1), 53–67.

- Tuntivivat, S., Jafar, S., Seelhammer, C., & Carlson, J. (2018). Indigenous youth engagement in environmental sustainability: Native Americans in Coconino County. International Journal of Behavioral Science, 13(2), 82–93.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021). What is environmental education? [ Overviews and Factsheets]. https://www.epa.gov/education/what-environmental-education

- UNESCO. (1978). Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education: Tbilisi (USSR), 14-26 October 1977. Final report. http://www.gdrc.org/uem//ee/EE-Tbilisi_1977.pdf

- Wiium, N., & Dimitrova, R. (2019). Positive youth development across cultures: Introduction to the special issue. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09488-7

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., & Buntins, K. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. Springer Nature.

AppendixBibliography of the 60 Studies in the Final Review Sample

- Aguilar, O. (2018). Toward a theoretical framework for community EE. Journal of Environmental Education, 49(3), 207–227.

- Allen, K., & Elmore, R. D. (2012). The effects of the wildlife habitat evaluation program on targeted life skills. Journal of Extension, 50(1).

- Ampuero, D. A., Miranda, C., & Goyen, S. (2015). Positive psychology in education for sustainable development at a primary-education institution. Local Environment, 20(7), 745–763.

- Ampuero, D., Miranda, C. E., Delgado, L. E., Goyen, S., & Weaver, S. (2015). Empathy and critical thinking: Primary students solving local environmental problems through outdoor learning. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15(1), 64–78.

- Ardoin, N. M., DiGiano, M., O’Connor, K., & Holthuis, N. (2016). Using online narratives to explore participant experiences in a residential environmental education program. Children’s Geographies, 14(3), 263–281.

- Barnett, M., Vaughn, M., Strauss, E., & Cotter, L. (2011). Urban environmental education: Leveraging technology and ecology to engage students in studying the environment. International Research in Geographical & Environmental Education, 20(3), 199–214.

- Birdsall, S. (2013). Reconstructing the relationship between science and education for sustainability: A proposed framework of learning. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 8(3), 451–478.

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Di Mambro, G. (2015). Environmental education action research with immigrant children in schools: Space, audience and influence. Action Research, 13(2), 123–140.

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Reilly, R. C. (2017). Immigrant children promoting environmental care: Enhancing learning, agency and integration through culturally-responsive environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 23(4), 553–572.

- Blythe, C., & Harré, N. (2020). Encouraging transformation and action competence: A theory of change evaluation of a sustainability leadership program for high school students. Journal of Environmental Education, 51(1), 83–96.

- Breunig, M., Murtell, J., & Russell, C. (2015). Students’ experiences with/in integrated environmental studies programs in Ontario. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15(4), 267–283.

- Briggs, L., Krasny, M., & Stedman, R. C. (2019). Exploring youth development through an environmental education program for rural Indigenous women. Journal of Environmental Education, 50(1), 37–51.

- Caiman, C., & Lundegård, I. (2014). Pre-school children’s agency in learning for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 20(4), 437–459.

- Ceaser, D. (2012). Our school at Blair Grocery: A case study in promoting environmental action through critical environmental education. Journal of Environmental Education, 43(4), 226.

- Cincera, J., & Krajhanzl, J. (2013). Eco-Schools: What factors influence pupils’ action competence for pro-environmental behaviour? Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 117–121.

- Cincera, J., & Simonova, P. (2017). “I am not a big man”: Evaluation of the issue investigation program. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 16(2), 84–92.

- Dale, R. G., Powell, R. B., Stern, M. J., & Garst, B. A. (2020). Influence of the natural setting on environmental education outcomes. Environmental Education Research, 26(5), 613–631.

- Davis, N. R., & Schaeffer, J. (2019). Troubling troubled waters in elementary science education: Politics, ethics & Black children’s conceptions of water [justice] in the era of Flint. Cognition and Instruction, 37(3), 367–389.

- de Vreede, C., Warner, A., & Pitter, R. (2014). Facilitating youth to take sustainability actions: The potential of peer education. Journal of Environmental Education, 45(1), 37–56.

- Dimick, A. S. (2012). Student empowerment in an environmental science classroom: Toward a framework for social justice science education. Science Education, 96(6), 990–1012.

- Dittmer, L., Mugagga, F., Metternich, A., Schweizer-Ries, P., Asiimwe, G., & Riemer, M. (2018). “We can keep the fire burning”: Building action competence through environmental justice education in Uganda and Germany. Local Environment, 23(2), 144–157.

- DuBois, B., Krasny, M. E., & Smith, J. G. (2018). Connecting brawn, brains, and people: An exploration of non-traditional outcomes of youth stewardship programs. Environmental Education Research, 24(7), 937–954.

- Fröhlich, G., Sellmann, D., & Bogner, F. X. (2013). The influence of situational emotions on the intention for sustainable consumer behaviour in a student-centred intervention. Environmental Education Research, 19(6), 747–764.

- Gallay, E., Marckini-Polk, L., Schroeder, B., & Flanagan, C. (2016). Place-based stewardship education: Nurturing aspirations to protect the rural commons. Peabody Journal of Education, 91(2), 155–175.

- Garip, G., Richardson, M., Tinkler, A., Glover, S., & Rees, A. (2021). Development and implementation of evaluation resources for a green outdoor educational program. Journal of Environmental Education, 52(1), 25–39.

- Gibbs, L., Block, K., Ireton, G., & Taunt, E. (2018). Children as bushfire educators—“just be calm, and stuff like that”. Journal of International Social Studies, 8(1), 86–112.

- Goldman, D., Assaraf, O. B. Z., & Shaharabani, D. (2013). Influence of a non-formal environmental education programme on junior high-school students’ environmental literacy. International Journal of Science Education, 35(3), 515–545.

- Hadjichambis, A. Ch., Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Ioannou, H., Georgiou, Y., & Manoli, C. C. (2015). Integrating sustainable consumption into environmental education: A case study on environmental representations, decision making and intention to act. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 10(1), 67–86.

- Heras, M., & Tàbara, J. D. (2016). Conservation theatre: Mirroring experiences and performing stories in community management of natural resources. Society & Natural Resources, 29(8), 948–964.

- Heras, R., Medir, R. M., & Salazar, O. (2020). Children’s perceptions on the benefits of school nature field trips. Education 3-13, 48(4), 379–391.

- Hinds, J. (2011). Woodland adventure for marginalized adolescents: Environmental attitudes, identity and competence. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 10(4), 228–237.

- Holley, D., & Park, S. (2020). Integration of science disciplinary core ideas and environmental themes through constructivist teaching practices. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16(5).

- IDRISSI, H. (2020). Exploring global citizenship learning and ecological behaviour change through extracurricular activities. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 39(3), 272–290.

- Johnson-Pynn, J. S., Johnson, L. R., Kityo, R., & Lugumya, D. (2014). Students and scientists connect with nature in Uganda, East Africa. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 9(3), 311–327.

- Karahan, E., & Roehrig, G. (2016). Use of web 2.0 technologies to enhance learning experiences in alternative school settings. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 4(4), 272–283.

- Kim, M., & Tan, H. T. (2013). A collaborative problem-solving process through environmental field studies. International Journal of Science Education, 35(3), 357–387.

- Ladawan, C., Singseewo, A., & Suksringarm, P. (2015). Development of environmental knowledge, team working skills and desirable behaviors on environmental conservation of Matthayomsuksa 6 students using good science thinking moves method with metacognition techniques. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(13), 1846–1850.

- Lee, E. U. (2017). The eco-club: A place for the becoming active citizen? Environmental Education Research, 23(4), 515–532.

- Liddicoat, K. R., & Krasny, M. E. (2014). Memories as useful outcomes of residential outdoor environmental education. Journal of Environmental Education, 45(3), 178–193.

- Lithoxoidou, L. S., Georgopoulos, A. D., Dimitriou, A. Th., & Xenitidou, S. Ch. (2017). “Trees have a soul too!” Developing empathy and environmental values in early childhood. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 5(1), 68–88.

- Littrell, M. K., Tayne, K., Okochi, C., Leckey, E., Gold, A. U., & Lynds, S. (2020). Student perspectives on climate change through place-based filmmaking. Environmental Education Research, 26(4), 594–610.

- Marques, R. R., Malafaia, C., Faria, J. L., & Menezes, I. (2020). Using online tools in participatory research with adolescents to promote civic engagement and environmental mobilization: The WaterCircle (WC) project. Environmental Education Research, 26(7), 1043–1059.

- Meza Rios, M. M., Herremans, I. M., Wallace, J. E., Althouse, N., Lansdale, D., & Preusser, M. (2018). Strengthening sustainability leadership competencies through university internships. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(4), 739–755.

- Papastergiou, M., Antoniou, P., & Apostolou, M. (2011). Effects of student participation in an online learning community on environmental education: A Greek case study. Technology, Pedagogy & Education, 20(2), 127–142.

- Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Hadjichambis, A. Ch., & Korfiatis, K. (2015). How students’ values are intertwined with decisions in a socio-scientific issue. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 10(3), 493–513.

- Schindel, A., & Tolbert, S. (2017). Critical caring for people and place. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(1), 26–34.

- Selby, S. T., Cruz, A. R., Ardoin, N. M., & Durham, W. H. (2020). Community-as-pedagogy: Environmental leadership for youth in rural Costa Rica. Environmental Education Research, 26(11), 1594–1620.

- Skinner, Ellen A, Chi, U., & The Learning-Gardens Educational Assessment Group1. (2012). Intrinsic motivation and engagement as “active ingredients” in garden-based education: Examining models and measures derived from self-determination theory. Journal of Environmental Education, 43(1), 16–36.

- Smith, J., DuBois, B., & Krasny, M. (2016). Framing for resilience through social learning: Impacts of environmental stewardship on youth in post-disturbance communities. Sustainability Science, 11(3), 441–453.

- Sperling, E., & Bencze, J. L. (2015). Reimagining non-formal science education: A case of ecojustice-oriented citizenship education. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics & Technology Education, 15(3), 261–275.

- Stapleton, S. R. (2019). A case for climate justice education: American youth connecting to intragenerational climate injustice in Bangladesh. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 732–750.

- Stern, M. J., Frensley, B. T., Powell, R. B., & Ardoin, N. M. (2018). What difference do role models make? Investigating outcomes at a residential environmental education center. Environmental Education Research, 24(6), 818–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1313391

- Stern, M. J., Powell, R. B., & Ardoin, N. M. (2010). Evaluating a constructivist and culturally responsive approach to environmental education for diverse audiences. The Journal of Environmental Education.

- Tanu, D., & Parker, L. (2018). Fun, ‘family,’ and friends. Indonesia & the Malay World, 46(136), 303–324.

- Thomas, R. E. W., Teel, T. L., & Bruyere, B. L. (2014). Seeking excellence for the land of paradise: Integrating cultural information into an environmental education program in a rural Hawaiian community. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 41, 58–67.

- Tierney, G., Goodell, A., Nolen, S. B., Lee, N., Whitfield, L., & Abbott, R. D. (2020). (Re)designing for engagement in a project-based AP environmental science course. Journal of Experimental Education, 88(1), 72–102.

- Tsevreni, I. (2011). Towards an environmental education without scientific knowledge: An attempt to create an action model based on children’s experiences, emotions and perceptions about their environment. Environmental Education Research, 17(1), 53–67.

- Tuntivivat, S., Jafar, S., Seelhammer, C., & Carlson, J. (2018). Indigenous youth engagement in environmental sustainability: Native Americans in Coconino County. International Journal of Behavioral Science, 13(2), 82–93.

- Williams, C. C., & Chawla, L. (2016). Environmental identity formation in nonformal environmental education programs. Environmental Education Research, 22(7), 978–1001.

- Zhan, Y., He, R., & So, W. W. M. (2019). Developing elementary school children’s water conversation action competence: A case study in China. International Journal of Early Years Education, 27(3), 287–305