ABSTRACT

This study examines the influence of family social support on student resilience and self-regulated learning (SRL), as well as the role of SRL as a mediator for Indonesian and Turkish students. This quantitative method used three research scales to answer the research questions: resilience, family social support, and self-regulated learning. The study included 606 Indonesian respondents and 504 Turkish respondents. In this study, the researchers used a structural equation model based on partial least squares to perform data analysis. The results showed that Indonesian students had a higher average academic resilience score than Turkish students. Turkish students’ family social support scores were higher than Indonesian students. The bootstrapping method demonstrated a positive indirect effect of SRL on the relationship between family social support and academic resilience. Hence, SRL is a good variable that connects family social support with academic resilience.

Introduction

Suicide cases among students have shown an alarming rate for the past few years. The WHO noted that more than 700.000 people die by suicide each year in the age group of 15–29 years. Indonesia has a suicide rate of 2.4 per 100,000 people. High levels of stress due to academic and social pressure are one of the causes. High academic pressure, including deadlines, assignments, exams, and demands for high achievement, can cause excessive stress levels (M. F. Suud & Na’imah, Citation2023). The students’ limited capacity to cope with the diverse challenges they encounter is also a contributing factor to the rising prevalence of student suicide. Therefore, the focus on academic resilience is a significant priority for numerous studies in the present day. Currently, the discussion around academic resilience holds significant importance. The ScienceDirect website yielded 5,529 academic resilience-specific documents for the year 2022 and 6,394 documents for the year 2023. Overall, there is a strong correlation between resilience and academic resilience

Academic resilience has been a concern for researchers before. Elnaem et al. (Citation2024) investigated 12 countries related to student resilience. He found that the highest academic resilience was in Sudan, Pakistan, and Nigeria. While in Indonesia and Turkey, low levels of resilience were also reported. This study also found that students studying at private universities had higher academic resilience than students studying at private universities. Academic resilience is often positively connected to academic achievement (Hunsu et al., Citation2023; Sattler & Gershoff, Citation2019). Yang and Wang (Citation2021) & Cassidy et al. (Citation2023) found that academic resilience is not only connected to achievement but can also contribute to improving students’ mental well-being. In addition, subjective well-being and life satisfaction were found to be strong predictors of academic resilience among college students. Saunders et al. (Citation2023) and Kim et al. (Citation2021) linked academic resilience with emotional engagement. Previous research has proven the importance of academic resilience for students. However, efforts to realize academic resilience are also related to other variables. One of the relationships is the variables of self-regulated learning and family social support, which are intrinsic and extrinsic elements.

The research gap was finally found in some previous research results, which revealed why Indonesia and Turkey are referred to as countries with lower academic resilience than others. Influences from within the student and from outside were re-examined. Family social support as a representative variable of external students has shown its important role. Permatasari et al. (Citation2021) added that family social support is the most dominant element that contributes to academic resilience compared to other variables. Cheng et al. (Citation2012) reinforced the important role of Family social support in academics. The level of family social support is perceived as important not only as a major predictor of the magnitude and stability of students’ grades for three consecutive semesters but also as a factor that helps students succeed in any field.

Self-regulated learning is an internal variable in students that has been proven to positively affect academic achievement consistently (Alibakhshi & Zare, Citation2010; Kibtiyah & Suud, Citation2024; Pandey et al., Citation2018). Mohan and Verma (Citation2020) emphasized that SRL is remarkably strategic in increasing academic resilience. Self-regulatory learning strategies, such as metacognitive regulation, are also strong predictors of academic adjustment (Cazan, Citation2012). Separately, some research has proven that the two studied variables played an important role in influencing academic resilience. However, the relationship between two phenomena sometimes does not exist because other phenomena often act as intermediaries.

Based on previous studies, human behaviour is not always influenced by variables directly but rather involves mediation processes that influence it (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986a; Urbayatun & Widhiarso, Citation2013). Therefore, this study seeks to reveal whether self-regulated learning plays a mediating role in the relationship between the dimensions of social support and academic resilience of students in Indonesia and Turkey.

Literature review

Academic resilience

Resilience is an individual’s ability to bounce back from adversity and trauma (Masten et al., Citation2012). Resilience can be learned and developed through life experience and social support (F. M. Suud et al., Citation2023). Tough life experiences and frequent challenges can make a person learn to survive. Academic resilience is a person’s endurance or fighting power in learning. Gunawan and Huwae (Citation2022) found that resilience studies on students show that students with good resilience skills have high academic resilience. The big question arises from thousands of studies on academic resilience that previous researchers have conducted: what are the benefits for children who have academic resilience, and what are the consequences for students if they do not? Academic resilience predicts positive educational and psychological student outcomes (Martin & Marsh, Citation2008). Collectively, these papers show that family social support plays an important role in academic resilience among students.

Permatasari et al. (Citation2021) found that perceptions of family support contribute the highest to academic resilience in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Putri (Citation2022) also found a positive relationship between peer social support and academic resilience among young adult migrant students. Additionally, Romano et al. (Citation2021) found that teachers’ emotional support mediated the relationship between academic resilience and school engagement. However, Wilks (Citation2008) focused on social work students and found that peer support, versus family support, moderated the negative association between academic stress and resilience. Overall, the paper highlights the importance of social support, particularly from family and peers, in improving academic resilience.

Family social support

Some research suggests that family support affects academic resilience. A study found that parental support significantly impacted academic resilience, and expectations and active coping mediated this relationship (Cheraghian et al., Citation2023). Another study found that family communication patterns were positively associated with high school students’ academic resilience (Jowkar et al., Citation2011). Other studies highlighted the importance of healthy school and family relationships in fostering academic resilience (Gafoor & Kottalil, Citation2011). Parental involvement is positively associated with resilience in children with special educational needs. A study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic discovered that family social support positively impacted children’s mental health resilience (Kadiri, Citation2023).

Overall, some of these studies suggest that family support is important in improving academic resilience among students. Parents and families can provide emotional support, encouragement, and resources that help students overcome academic challenges and develop resilience. The results showed that self-regulated learning influenced shaping academic resilience. In addition, research has shown that self-regulated learning (SRL) is important for students’ educational advancement because it makes them more motivated and academically successful. Longitudinal studies found that senior high school students’ reports on self-regulation strategies were positively associated with their academic achievement and resilience (Yang & Wang, Citation2021). Metacognitive self-regulation, effort setting, and self-evaluation skills in online learning could significantly improve academic achievement (Xu et al., Citation2022). Student resilience and self-regulating learning positively affect academic achievement (Galizty & Sutarni, Citation2021). A study conducted on high school students in Spain found that academic self-regulation negatively predicted procrastination and positively predicted academic achievement and resilience (Ragusa et al., Citation2023). Thus, self-regulation in learning is an important factor in shaping academic resilience. Self-regulated learning strategies can help students become more motivated, academically successful, and resilient in facing academic challenges.

Social support in general, and family support in particular, can also influence the development of self-regulated learning. SRL can help students develop the ability to organize and control their learning process, including in facing academic difficulties and challenges. SRL can help students develop the ability to cope with academic stress and pressure, which is an important factor in the development of academic resilience. SRL can help students develop the ability to evaluate their learning outcomes and make necessary changes, which is an important factor in developing academic resilience (Deasyanti & Armeini, Citation2007). Support from family can help students develop SRL by providing an environment conducive to learning and emotional support. Support from family can also help students develop the ability to overcome academic difficulties and challenges, which is an important factor in the development of academic resilience (Putri, Citation2022).

Self-regulated learning

Self-regulated learning theory is a prominent characteristic of social cognitive theory, which is Bandura’s main idea (Bandura, Citation1991). B. J. Zimmerman and Martinez-Pons (Citation1990) also proposed a formulation to explain self-regulated learning based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory. Bandura said that students’ efforts to regulate themselves in learning involve three dimensions, namely the student’s personal processes, environment, and behaviour (B. J. Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, Citation1990). Self-regulated learning is an important aspect of academic success, which involves the ability to understand and control one’s learning environment. Saribeyli (Citation2018) included metacognitive awareness, motivation, and the use of effective learning strategies. Weerasingha et al. (Citation2024) & Morris et al. (Citation2023) further emphasized the active and constructive nature of self-directed learning, with learners setting goals and monitoring their progress.

Ansong et al. (Citation2024) highlighted the role of teachers in encouraging independent learning, suggesting that students can be taught to become independent learners. Self-regulation in learning can be interpreted as self-direction or self-regulation in behaviour. Meanwhile, learning based on self-regulation can be interpreted as regulating or directing oneself in learning (Zimmerman, Citation1989). Eggen & Kauchak further argued that learning based on self-regulation is a process of individuals using thoughts and actions to achieve maximum learning goals (Eggen & Kauchak, Citation2010). According to Shcunk, self-regulation in learning contexts necessitates students to possess autonomy in determining both their actions and methods (Schunk, Citation2012). Therefore, self-regulated learning has a crucial role in mediating family social support.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of university students (N = 1110) from Indonesia (N = 606) and Turkey (N = 504). Most students in both groups were female (Turkey, 72.1%; Indonesia, 60.24%). The sample’s age range was 20–24, and the mean age was 22. The departments the students studied varied from theological sciences to social, medical, communicational, and engineering sciences. All respondents provided satisfactory responses to the offered questions, as indicated by the lack of empty answers from any of the respondents.

Instruments

The resilience scale

The Resilience Scale was prepared based on the resilience factor developed by Reivich (Citation2002). It consists of emotional regulation, impulse control, optimism, causal analysis, empathy, self-efficacy, and reaching out (Salleh et al., Citation2021). The scale consisted of 24 items designed to measure student academic resilience by statements. The Family Social Support Scale was prepared based on the concept of family support (Friedman, Citation2003), which was designed based on the dimensions of family social support, such as emotional support, instrumental support, information support, and reward support, and modified into 23 items.

The self-regulated learning scale

The Self-Regulated Learning Scale is a modified self-regulated learning scale that consists of 28 items and is developed based on the dimensions of metacognition, motivation, and behavioural skills, as described by (B. J. Zimmerman & Moylan, Citation2009; Zimmerman, Citation1990). All scales were Likert-type, consisting of five optional answers from strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, to strongly agree.

Procedures

The research instruments were distributed to university students in Indonesia and Turkey online through Google Forms. The questionnaire took about 15 minutes. Researchers were involved in the data collection process. There was no compulsion to fill the research scale. At the time of filling in the research data, the researchers provided informed consent, and respondents were given the freedom to agree or disagree to engage in research. Data collection continued when respondents were willing to fill out the research scale. So, there was no coercion in the data collection process.

After data collection, numerical data from family support, SRL, and academic resilience variables were analysed to test the relationship model between variables using Partial Least Square (PLS) software. Data analysis was carried out by combining measurement model testing (outer model), including convergent validity tests, discriminant validity, construct reliability, and structural model testing (inner model) on latent variables to see the strength of estimates between latent variables based on substantive theory. PLS is a model in Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) that adopts a variant-based approach. In this study, PLS-SEM is a multivariate statistical analysis method that combines the outer model and the inner model (Abdillah & Hartono, Citation2015). By using PLS-SEM, researchers could analyse and interpret the relationship between variables in the model comprehensively, thus providing deeper insight into the interaction and influence between family support variables and SLR on student academic resilience.

Results

Outer model testing

The measurement model was evaluated using three main criteria: convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability (Sarstedt et al., Citation2021). Convergent validity was assessed by observing the research variables’ outer loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). Generally accepted guidelines for establishing convergent validity suggest that the outer loading value should exceed 0.7, although values of 0.5 to 0.6 are also considered acceptable (Ghozali & Latan, Citation2015). A high outer loading value indicates that the indicators consistently measure the same construct. An AVE value higher than 0.5 is considered better, implying that the construct effectively captures the measured concept, demonstrating strong convergent validity (Gye-Soo, Citation2016; Sarstedt et al., Citation2021). The analysis is presented in .

Table 1. Measurement Model.

indicates that all constructs have outer loading values passing 0.6, implying a significant contribution to the measured factor. The strong relationship between the indicator and the construct is apparent because the outer loading value exceeds the preset limit. In addition, the analysis results showed that the AVE values for all constructs exceeded 0.5, confirming that construct validity was adequately met.

Cronbach alpha and composite reliability were used to measure the reliability of measurements of social support from family, self-regulated learning, and academic resilience. A high Cronbach alpha and composite reliability score indicate reliability in measuring these three variables. Where for the Cronbach academic resilience variable, the alpha score is 0.913, and the composite reliability is 0.927. Cronbach’s Family Social Support alpha score is 0.810, and composite reliability is 0.902. Cronbach’s self-regulated learning alpha score is 0.868, and composite reliability is 0.864.

The Cronbach alpha for each construct exceeds 0.7, indicating that these measurements are reliable. Composite reliability (CR) is an alternative way to measure internal consistency. It is based on confirmatory factors or models and tends to give more conservative estimates than Cronbach alpha. CR values also range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a higher level of reliability. The results of discriminant validity (correlation of latent variables and square roots of AVE) are presented in .

Table 2. Discriminant Validity Measurement.

The number in bold is the square of AVE, while the value outside the diagonal is the correlation. X = family social support; M = self-regulated learning; Y = academic resilience. shows that the measurements used in this study had adequate discriminant validity. The validity of this discriminant shows that the measurement tool is effective in measuring various dimensions that want to be studied separately so that the research results become more reliable and relevant.

Inner model testing

The problem of collinearity in structural models is evaluated using VIF values for all variables. VIF is also seen as the opposite of tolerance, and standard bias tests are performed based on these VIF values. If the value of VIF is equal to or lower than 3.30, then there is no significant bias problem (Ghozali, Citation2014; Sarstedt et al., Citation2021). All VIF values were below 3.30 (see ).

Table 3. Multicollinearity Analysis.

Therefore, the data used in this study did not suffer from bias problems. In addition, another recommended approach to examining possible multicollinearity problems is to evaluate the HTMT (heterotrait-monotrait) ratio. As a guideline, the construct value should not exceed 0.9. The maximum value for the evaluated constructs was below 0.9, so this study did not experience multicollinearity problems. Full results are presented in .

The researchers used the coefficient of determination (R square) in the PLS-SEM structural model to indicate the extent to which the independent variable explains variation in the predictor variable. In PLS-SEM, the R square value is generally considered good if it is greater than or equal to 0.60, moderate if it is about 0.33, and weak if it is about 0.19. In this study, an R square score of 0.637, which falls into the good category, suggests that family social support and self-regulated learning together account for 63.7% of the variation in academic resilience.

The f-square test is used to measure the influence of endogenous variables on exogenous variables, providing insight into the extent of the impact of endogenous variables on exogenous variables. The f-squared value in this study indicated how much the family social support variable affects academic resilience, with a value of 0.018. This effect size falls into the weak category, suggesting that family social support weakly influences academic resilience. Furthermore, the self-regulated learning variable has an f-square value of 0.287, which indicates a moderate influence on academic resilience. The family social support variable also has an f-square value of 0.607, indicating a high influence on self-regulated learning.

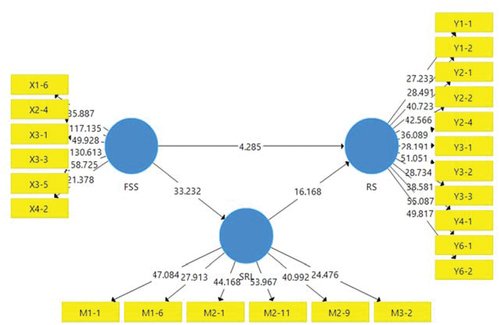

illustrates a standardized estimate for the structural model of this study. This image provides information on factor loading for each item and the mediating effects of self-regulated learning.

Figure 1. Inner Model Testing Result: The Relationship of Family Social Support to the Academic Resilience of Indonesian and Turkish Students and the Role of SRL Mediation.

shows the path coefficients of the study, which are useful numbers to describe the direction of the relationship between variables, indicating whether the hypothesis has a positive or negative direction. Path coefficients have a range of values between −1 and 1. If the value is between 0 and 1, it signals a positive direction of the relationship, while if the value is between −1 and 0, it indicates a negative direction of the relationship (Ghozali, Citation2018; Sarstedt et al., Citation2021).

Table 4. Results of path coefficients.

shows a negative relationship between the variables Family Social Support and Academic Resilience, meaning that the higher the level of family social support, the lower the level of academic resilience. This negative relationship indicates that hypothesis one is rejected or not supported by the data found in the study. In other words, the results do not support the hypothesis that assumes a positive relationship between the two variables. Hypotheses 2 and 3 are accepted, meaning that family social support has a positive relationship direction with self-regulated learning (t = 33,232; p = 0.000), self-regulated learning has a positive relationship direction with academic resilience (t = 16,168; p = 0.000). Family social support can help individuals develop and improve self-regulated learning skills. Furthermore, self-regulated learning can affect the level of academic resilience.

Furthermore, bootstrapping methods were carried out to calculate the indirect effects. Self-regulated learning mediated the relationship between family social support and academic resilience (b = 0.360; SD = 0.026; t = 13.738; p = 0.000). Self-regulated learning helps explain why there is a relationship between family social support and academic resilience in this study. Thus, self-regulated learning functions fully as a mediator variable and plays an important role in explaining the effect of family social support on academic resilience. Baron and Kenny (Citation1986b) argue that the mediator variable is not necessarily the only observed cause of effect; it still contributes meaningfully to explaining the phenomenon. In other words, the mediator can explain how and to what extent the independent variable affects the dependent variable, even if there are still other influences that also play a role in influencing the dependent variable.

Difference test

A t-test was conducted to determine the average difference between each variable in the two countries. Results are given in

shows a significant difference in the average score of academic resilience between Indonesian and Turkish students. Indonesian students have a higher average score than Turkish students (M = 23.8482 > M = 21.7183; Sig = 0.000). These results show that Indonesian students have a significantly higher level of academic resilience than Turkish students. The average score of family social support also had a significant difference. Students from Turkey had a higher average score in family social support (M = 13.2706 < M = 22.5992; Sig = 0.000) than Indonesian students. The average score of Indonesian students’ self-regulated learning variables is lower than that of Turkish students (M = 13.3548 < M = 17.1468; Sig. = 0.000).

Table 5. Differences in academic resilience and family social support and self-regulated learning between Indonesian and Turkish students.

Discussion

The results showed a negative relationship between the variables Family Social Support and Academic Resilience, meaning that the higher the level of family social support, the lower the level of academic resilience. This result differs from (Permatasari et al., Citation2021), showing that family support is the most dominant element and contributes to strengthening students’ academic resilience. Good communication and intensive interaction between parents and children are believed to increase student resilience in facing academic challenges (Jowkar et al., Citation2011). However, in certain situations, students must also develop independence in managing themselves. Sometimes, overprotective families can protect their children from experiences of adversity or failure, but this situation can make students less accustomed to facing actual academic challenges and developing resilience skills. Some students depend significantly on their families for assistance and miss opportunities to develop independence. In that case, they may be less able to cope with stress or academic difficulties in a more independent environment such as college. Therefore, it is important to find a balance between the family support provided and allowing students to develop their resilience skills. This study found the importance of the role of family in improving students’ self-regulation skills.

According to (Choe, Citation2020), adolescents need academic and emotional support for academic achievement and self-regulated learning. Academic support can take the form of help and resources that assist students in understanding course material coursework and developing academic skills. Emotional support includes understanding, support, and comfort provided by family, friends, or other social environments, helping teens cope with stress, anxiety, and other emotional challenges that can affect academic performance (F. M. Suud et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, the study also found the importance of self-regulated learning in increasing academic resilience. Saufi et al. (Saufi et al., Citation2022) also found that self-regulated learning can increase the academic resilience of adolescents in Indonesia. In other words, adolescents who can organize and manage their learning are more likely to be more resilient and empowered in academic contexts. (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986b) argued that the mediator variable is not necessarily the only observed cause of effect; it still contributes meaningfully to explaining the phenomenon. In other words, the mediator can explain how and to what extent the independent variable affects the dependent variable, even if there are still other influences that also play a role in influencing the dependent variable.

The findings revealed that self-regulated learning mediated the relationship between family social support and student academic resilience. Balanced family social support can also help students develop independence in their learning. They learn how to manage their time, identify resources, and overcome obstacles effectively, essential elements of self-regulated learning. Self-regulated learning also involves the ability to overcome failures or difficulties in learning. Good family social support can provide the emotional and psychological support needed to help students feel more resilient when facing academic difficulties, thereby increasing academic resilience. The findings (Erda & Yuniardi, Citation2023) on students in Indonesia explained that the higher the social support, the higher the self-regulated tolerance, ultimately increasing academic resilience. In this context, the higher social support students receive, the higher their ability to organize their learning. Students who organize their learning well tend to be more resilient in the face of academic challenges and could recover after experiencing failure or adversity. The findings illustrated that the social support received by students can help them develop self-regulated learning skills, which in turn increases their ability to become more resilient in an academic environment.

The results of the different tests show differences in factors that support academic resilience and self-regulated learning between Indonesian and Turkish students. There is a significant difference in the average score of academic resilience between Indonesian and Turkish students. Indonesian students have a higher average score compared to Turkish students. These results show that Indonesian students have a significantly higher level of academic resilience than Turkish students. The average score for family social support also had a significant difference; students from Turkey had a higher average score for family social support. It can be interpreted that students from Turkey have a significantly higher level of family social support than Indonesian students.

Several factors can cause low academic resilience, based on internal factors: spirituality, self-efficacy, optimism, and self-esteem. External factors include family support, peer support, lecturer support, and a learning environment that is not conducive. High academic demands and a lack of resources also influence a person’s academic resilience (Missasi & Izzati, Citation2019). Belief systems and traditions in culture and religion are some of the things that are recommended for the formation of resilience (Utami, Citation2020). Factors that influence family support for weak academic resilience include lack of emotional, instrumental, and information support from family, lack of family involvement in children’s education, family conflicts, and lack of family understanding of the importance of academic resilience (Prabowo, Citation2020; Pratiwi & Watini, Citation2021; Tara Ayodani et al., Citation2023).

According to several studies conducted in Turkey, besides family support, other factors can increase academic resilience, including having a positive self-concept, one of the internal protective factors positively associated with academic resilience among impoverished adolescents (Gizir & Aydin, Citation2009). Having a positive self-concept can help increase academic resilience. Self-efficacy is another protective factor positively associated with academic resilience among impoverished adolescents. High self-efficacy, motivation, and coping abilities can help increase academic resilience (Gizir & Aydin, Citation2009; Yang & Wang, Citation2021). The conclusion is that internal factors are stronger for increasing academic resilience. The researchers’ hypothesis was rejected in this study. Research in Indonesia on regional students found that academic resilience was determined more by self-efficacy than social support (Linggi et al., Citation2021). Students living outside their home area must face academic challenges without direct support from their family or social environment. Therefore, they tend to rely on independence and self-efficacy in overcoming academic problems. Meanwhile, respondents in this study were aged 20–24 years where they already tended to take responsibility for themselves and self-development for their future success.

Theresya and Setiyani (Citation2023) found that social support has no effect on academic resilience, but self-esteem and self-efficacy have a positive effect on academic resilience. The dimensions of emotional support, instrumental support, information support, and companionship support are empirically proven not to affect students’ academic resilience. Self-esteem and self-efficacy are internal factors underlying how students respond to and overcome academic challenges. Students who have high levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy tend to be better able to deal with stress and academic challenges, thus increasing their level of resilience. Although social support is considered important in many resilience studies, its effects can vary depending on the context and quality of support received.

The average score of Indonesian students’ self-regulated learning variables is lower than that of Turkish students (M = 13.3548 < M = 17.1468; Sig. = 0.000). This finding revealed a significant relationship between emotion regulation, optimism, family support, and student resilience. According to one study, academic stress can affect self-regulated learning in students. Students who experience academic stress tend to have low self-regulated learning (Febriana & Simanjuntak, Citation2021). According to a study, environmental factors are one of the factors that affect self-regulated learning in students. Students who lack support from the environment tend to have low self-regulated learning (Janah, Citation2020).

Academic procrastination can affect self-regulated learning in students. Students procrastinating on academic tasks tend to have low self-regulated learning (Maijoita, Citationn.d.). Other studies have found motivation as a factor that affects academic resilience. Students who lack motivation tend to have low self-regulated learning (Hardhito & Leonardi, Citation2016).

Conclusion

Academic resilience is a person’s ability to rise from difficulties and trauma in an academic context. Several variables, such as family social support and self-regulated learning, could enhance academic resilience. However, contrary to earlier research findings, this study discovered that unless self-regulated learning mediated the impact, family social support did not have an impact on academic resilience. Therefore, students also need to develop autonomy in managing themselves. In certain cultures, too-protective families can protect their children from experiencing difficulties or failures. However, this condition can make them less accustomed to facing actual academic challenges and developing resilience skills.

Further research is needed to deepen this issue. This research showed that self-regulated learning can help cultivate student academic resilience. Another finding is that Turkish students had higher self-regulated learning and family social support than Indonesian students, but Indonesia had higher scores for academic resilience. This study has limitations because it did not explore the cultural differences of the two countries in depth. Therefore, this study suggests that further researchers should pay attention to cultural issues when developing similar research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fitriah M. Suud

Fitriah M. Suud is a lecturer in the Ph.D program specializing in Islamic educational psychology at Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She is an educational psychology researcher specializing in student resilience, with a particular emphasis on academic resilience, digital resilience, and Islamic resilience. Aside from her active research, she actively participates in community service initiatives aimed at helping students recognize and prepare for bullying at school. She is the editor of the International Journal of Islamic Educational Psychology and a reviewer for several national and international educational psychology journals.

Zuhal Agilkaya-Sahin

Zuhal Agilkaya-Sahin is a lecturer at Department of Psychological Counseling and Guidance, Istanbul Medeniyet Üniversitesi, Istanbul, Türkiye. She is a researcher who focuses on religion psychology and spiritual counseling.

Tri Na’Imah

Tri Na’Imah is a lecturer in the Faculty of Psychology at Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto, which is located in Indonesia. She possesses a PhD degree in Islamic Education Psychology from Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. With a strong commitment to research and community service, she specialises in educational psychology, specifically focusing on character education, well-being in schools, and the teaching profession.

Muhammad Azhar

Prof. Dr. Muhammad Azhar, MA, Lecturer at the Islamic Religion Faculty and Doctoral Programme, Postgraduate, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Member of BRAIS (UK). Member of Global Illuminators, Malaysia. Editorial Board of Strateginews, Jakarta. He is also a member of LARI (Lingkar Akademisi Reformis Indonesia), located in Yogyakarta. Turkey, South Korea, Japan, China, Dubai, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Pennsylvania, and Chattanooga have all hosted his works. He also gets comparative studies and research in Melbourne, Sydney, Thailand, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, Macao, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Holland, Spain, Germany, France, Washington, DC, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Chattanooga.

Mariah Kibtiyah

Mariah Kibtiyah, a lecturer at the Palngka Raya State Islamic Institute in Indonesia, has finished her doctoral program in Islamic educational psychology at Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. She actively conducts research in the field of educational psychology with a focus on the Big Five Personalities: Learning Achievement, Self-Regulated Learning, and Emotional Intelligence.

References

- Abdillah, W., & Hartono, J. (2015). Partial Least Square (PLS): Alternatif structural equation modeling (SEM) dalam penelitian bisnis. Andi.

- Alibakhshi, S. Z., & Zare, H. (2010). Effect of teaching self-regulated learning and study skills on the academic achievement of university students. Education. https://www.sid.ir/paper/151862/en

- Ansong, D., Okumu, M., Amoako, E. O., Appiah-Kubi, J., Ampomah, A. O., Koomson, I., & Hamilton, E. (2024). The role of teacher support in students’ academic performance in low- and high-stakes assessments. Learning and Individual Differences, 102396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102396

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–14.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986a). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986b). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Cassidy, S., Mawdsley, A., Langran, C., Hughes, L., & Willis, S. C. (2023). A large-scale multicenter study of academic resilience and well-being in pharmacy education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, ajpe8998. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe8998

- Cazan, A. M. (2012). Self-regulated learning strategies - Predictors of academic adjustment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.092

- Cheng, W., Ickes, W., & Verhofstadt, L. (2012). How is family support related to students’ GPA scores? A longitudinal study. Higher Education, 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9501-4

- Cheraghian, H., Moradian, K., & Nouri, T. (2023). Structural model of resilience based on parental support: The mediating role of hope and active coping. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 260.

- Choe, D. (2020). Parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parental support as predictors of adolescents’ academic achievement and self-regulated learning. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105172.

- Deasyanti, & Armeini, A. (2007). Self regulation learning Universitas Negeri Jakarta. Perspektif Ilmu Pendidikan, 16(7095), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.21009/PIP.162.2

- Eggen, & Kauchak. (2010). Educational psychology : Windows in classrooms (8th) ed.). NJ. Pearson Education. Inc.

- Elnaem, M. H., Wan Salam, W. N. A. A., Thabit, A. K., Mubarak, N., Abou Khatwa, M. M., Ramatillah, D. L., Isah, A. M., Barakat, M., Al-Jumaili, A. A., Mansour, N. O., Fathelrahman, A. I., Adam, M. F., Jamil, S., Baraka, M., Rabbani, S. A., Abdelaziz, D. H., Elrggal, M. E., Okuyan, B., & Elcioglu, H. K. (2024). Assessment of academic resilience and its associated factors among pharmacy students in twelve countries. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 88(5), 100693.

- Erda, B., & Yuniardi, M. S. (2023). Hubungan social support dengan academic resilience dimediasi self - regulated learning pada mahasiswa keperawatan dimasa pandemi. Profesional Health Journal, 5(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.54832/phj.v5i1.431

- Febriana, I., & Simanjuntak, E. (2021). Self regulated learning Dan Stres Akademik Pada Mahasiswa. Experientia: Jurnal Psikologi Indonesia, 9(2), 144–153.

- Friedman, M. (2003). Family nursing: Research, theory, and practice. Prentice Hall.

- Gafoor, K. A., & Kottalil, N. K. (2011). Within child factors fostering academic resilience: A research review. Endeavors in Education, 2(2), 104–117. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED574833.pdf

- Galizty, R. C. M. F., & Sutarni, N. (2021). The effect of student resilience and self-regulated learning on academic achievement. Pedagonal : Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan, 5(2), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.33751/pedagonal.v5i2.3682

- Ghozali, I. (2014). Structural equation modeling, metode alternatif dengan partial least square (PLS). Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

- Ghozali, I. (2018). Aplikasi analisis multivariate dengan program IBM SPSS 25. Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

- Ghozali, I., & Latan, H. (2015). Partial least squares Konsep, Teknik Dan Aplikasi Menggunakan Program SmartPLS 3.0 Untuk Penelitian Empiris (II). Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

- Gizir, C. A., & Aydin, G. (2009). Protective factors contributing to the academic resilience of students living in poverty in Turkey. Professional School Counseling, 13(1), 2156759X0901300.

- Gunawan, E., & Huwae, A. (2022). Peer social support and academic resilience for students from 3T regions at SWCU. Eduvest - Journal of Universal Studies, 2(12), 2701–2716.

- Gye-Soo, K. (2016). Partial least squares structural equation modeling(PLS-SEM): An application in customer satisfaction research. International Journal of U- and e-Service, Science and Technology, 9(4), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.14257/ijunesst.2016.9.4.07

- Hardhito, R., & Leonardi, T. (2016). Gambaran self-regulated learning pada Mahasiswa yang Tidak Menyelesaikan Skripsi dalam Waktu Satu Semester di Fakultas Psikologi Universitas Airlangga. Jurnal Psikologi Pendidikan dan Perkembangan, 5(1). https://repository.unair.ac.id/106814/4/4.%20BAB%20I%20PENDAHULUAN%20.pdf

- Hunsu, N., Oje, A. V., Tanner-Smith, E., & Adesope, O. (2023). Relationships between risk factors, protective factors, and achievement outcomes in academic resilience research: A meta-analytic review. Educational Research Review, 41(1), 100548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100548

- Janah, M. (2020). Perbedaan self regulated learning Pada Mahasiswa Asal Gayo Lues Yang Bekerja Dengan Tidak Bekerja Di Banda Aceh. Universitas Islam Negeri Ar-Raniry.

- Jowkar, B., Kohoulat, N., & Zakeri, H. (2011). Family communication patterns and academic resilience. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 87–90.

- Kadiri, M. (2023). Family social support and children’s mental health resilience during COVID-19—Case of Morocco. Youth, 3(2), 541–552.

- Kibtiyah, M., & Suud, F. M. (2024). Relationship between big five personalities and habit of memorizing the Qur’an on mathematics learning achievement through mediator of self-regulated learning. Islamic Guidance and Counseling Journal, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.25217/0020247453900

- Kim, S. J., Lee, J., Song, J. H., & Lee, Y. (2021). The reciprocal relationship between academic resilience and emotional engagement of students and the effects of participating in the Educational Welfare Priority Support Project in Korea: Autoregressive cross-lagged modeling. International Journal of Educational Research, 101802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101802

- Linggi, G. G. A., Hindiarto, F., & Roswita, M. Y. (2021). Efikasi Diri Akademik, Dukungan Sosial, Dan Resiliensi Akademik Mahasiswa Perantau Pada Pembelajaran Daring Di Masa Pandemi Covid-19. Jurnal Psikologi, 14(2), 217–232.

- Maijoita, R. R. (n.d.). Hubungan self-regulated learning Dengan Prokrastinasi Akademik Pada Mahasiswa Universitas Islam Riau. Universitas Islam Riau.

- Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2008). Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. Journal of School Psychology, 46(1), 53–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.01.002

- Masten, A., Cutuli, J., Herbers, J., & Reed, M.-G. (2012). Resilience in development. Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0012

- Missasi, V., & Izzati, I. D. C. (2019). Faktor – Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Resiliensi. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Magister Psikologi Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, 2009, 433–441. https://seminar.uad.ac.id/index.php/snmpuad/article/view/3455

- Mohan, V., & Verma, M. (2020). Self-regulated learning strategies in relation to academic resilience. Voice of Research, 9(3), 27–34. https://voiceofresearch.org/Doc/Full/December-20.pdf

- Morris, T. H., Bremner, N., & Sakata, N. (2023). Self-directed learning and student-centered learning: A conceptual comparison. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2023.2282439

- Pandey, A., Hale, D., Das, S., Goddings, A.-L., Blakemore, S.-J., & Viner, R. M. (2018). Effectiveness of Universal Self-regulation–Based interventions in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 566. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0232

- Permatasari, N., Rahmatillah Ashari, F., & Ismail, N. (2021). Contribution of perceived social support (Peer, Family, and Teacher) to academic resilience during COVID-19. Golden Ratio of Social Science and Education, 1(1), 01–12.

- Prabowo, M. A. (2020). Akademik Siswa Sma Broken Home Di Kota Palembang. Universita Sriwijaya.

- Pratiwi, I. A., & Watini, S. 2021. Implementation of school TV digital library as electronic learning media in Al-Amanah Islamic Kindergarten, Depok City. Edukasia: Journal of Education and Learning, 2 (2), 167–180. (Optimization, Islamic boarding school education, policy). https://cemerlang-paud-pancasakti.ac.id/index.php/prosiding/article/view/147

- Putri, Z. M. (2022). Pengembangan Model Resiliensi Sebagai Upaya Meningkatkan Ketangguhan Perawat Di Rumah Sakit Sumatera Barat. http://scholar.unand.ac.id/109369/

- Ragusa, A., González-Bernal, J., Trigueros, R., Caggiano, V., Navarro, N., Minguez-Minguez, L. A., Obregón, A. I., & Fernandez-Ortega, C. (2023). Effects of academic self-regulation on procrastination, academic stress and anxiety, resilience and academic performance in a sample of Spanish secondary school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14.

- Reivich, K. (2002). The resilience factor ; 7 essential skills for overcoming life’s inevitable obstacle. Bright & Happy Books.

- Romano, L., Angelini, G., Consiglio, P., & Fiorilli, C. (2021). Academic resilience and engagement in high school students: The mediating role of perceived teacher emotional support. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(2), 334–344.

- Salleh, R. R., Ismail, N. A. H. H., & Idrus, F. (2021). The relationship between self-regulation, self-efficacy, and psychological well-being among the Salahaddin University Undergraduate Students in Kurdistan. International Journal of Islamic Educational Psychology, 2(2), 105–126.

- Saribeyli, F. R. (2018). Theoretical and practical aspects of student self-assessment. Obrazovanie I Nauka, 183–194. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2018-6-183-194

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2021, November). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handbook of Market Research, 587–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57413-4_15

- Sattler, K., & Gershoff, E. (2019). Thresholds of resilience and within- and cross-domain academic achievement among children in poverty. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.003

- Saufi, M., Budiono, A. N., & Mutakin, F. (2022). Korelasi self regulated learning Dengan Resiliensi Akademik Mahasiswa. Jurnal Consulenza: Jurnal Bimbingan Konseling dan Psikologi, 5(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.56013/jcbkp.v5i1.1244

- Saunders, I. M., Pick, A. M., & Lee, K. C. (2023). Grit, subjective happiness, satisfaction with life, and academic resilience among pharmacy and physical therapy students at Two Universities. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2022.10.009

- Schunk, D. H. 2012. Learning theories: An educational perspective. 6. Pearson Education, Inc.

- Suud, F. M., & Rouzi, K. S., & Faisal bin Huesin Ismail. (2023). Proceedings of Eighth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology : ICICT 2023, London. Volume 1. Proceedings of Eighth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology, 3, 1116.

- Suud, M. F., & Na’imah, T. (2023). The effect of positive thinking training on academic stress of Muslim students in thesis writing: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 28(1).

- Tara Ayodani, B., Hendro Wibowo, D., & Kristen Satya Wacana, U. (2023). Dukungan Sosial Orang Tua dan Resiliensi Akademik Siswa SMP Selama Pembelajaran Daring. Jurnal Bimbingan Dan Konseling Indonesia, 8(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.23887/JURNAL_BK.V8I1.1737

- Theresya, D., & Setiyani, R. (2023). Pengaruh self Esteem dan Social Support terhadap Resiliensi Akademik Mahasiswa dengan Self Efficacy sebagai Variabel mediasi. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Pendidikan, 19(2), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.21831/jep.v19i2.53690

- Urbayatun, S., & Widhiarso, W. (2013). Variabel Mediator dan Moderator dalam Penelitian Psikologi Kesehatan Masyarakat. Jurnal Psikologi, 39(2), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.6985

- Utami, L. H. (2020). Bersyukur dan Resiliensi Akademik Mahasiswa. Nathiqiyyah, 3(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.46781/nathiqiyyah.v3i1.69

- Weerasingha, T. K., Ratnayake, C., Abeyrathne, R. M., & Tennakoon, S. U. B. (2024). Evidence-based intrapartum care during vaginal births: Direct observations in a tertiary care hospital in Central Sri Lanka. Heliyon, e28517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28517

- Wilks, S. E. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress : The moderating impact of social support among social work students, 9(2), 106–125. //pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4fcf/e9e492ab4c96d166a07382108302321b7f66.pdf

- Xu, L., Duan, P., Padua, S. A., & Li, C. (2022). The impact of self-regulated learning strategies on academic performance for online learning during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1047680

- Yang, S., & Wang, W. (2021). The role of academic resilience, motivational intensity and their relationship in EFL learners’ academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 823537. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.823537

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Article in Journal of Educational Psychology, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: an overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3–17.

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning: relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Article in Journal of Educational Psychology, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Moylan, A. R. (2009). Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. Handbook of Metacognition in Education, 299–315. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876428