ABSTRACT

Workplace stress is related to job turnover and intention to leave (ITL) the job and/or profession. The specific mechanisms that drive this association have received less attention, however substantive research using the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) workplace stress model provides an avenue to address this issue and inform workplace interventions to improve employee retention. Our meta-analysis of the associations of components of the ERI model with ITL (k = 23, N = 73,671) demonstrated that low rewards (r = -.41, CI: -.46, -.37) were more associated with an ITL than ERI (r = .33 CI: .27, .38), overcommitment (r = .26, CI: .21, .31), and effort (r = .25, CI: .20, .30). Moderation analysis showed that females were more likely than males to report ITL when effort was high and that males were more likely to report an ITL the profession when rewards were low. Although all components of the ERI model were related cross-sectionally with ITL, prospective designs that target male-dominated professions are required to assess if the findings are robust.

Introduction

The deleterious effects of work stress are many and include physical (Siegrist & Li, Citation2016) and mental health (Harvey et al., Citation2017), dysregulated physiology (Eddy et al., Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2023), decreased productivity (Hassard et al., Citation2018) and unsafe work practices (Dodoo & Al-Samarraie, Citation2019). Therefore, it is no surprise, that work stress is associated with job turnover (Söderberg et al., Citation2014) and intention to leave (ITL) the job or profession (Kim & Kao, Citation2014; Park & Min, Citation2020). Job turnover is estimated to cost an organisation up to 200% of an annual salary for recruiting, hiring, and training replacement staff (Allen et al., Citation2010), with additional indirect costs such as a loss of tacit knowledge (Dess & Shaw, Citation2001) and reduced customer satisfaction (Heavey et al., Citation2013). A strong proxy measure of job turnover is an employee’s intention to leave (He et al., Citation2020). While the consequences of work stress have been well-described, the specific features of work (and employee) that most contribute to an increased risk of turnover have received far less attention.

Large meta-analyses and systematic reviews have consistently shown an association between high workplace stress with increased ITL and actual job turnover (He et al., Citation2020; Kim & Kao, Citation2014; Park & Min, Citation2020). Although these reviews provide an important overview of the area, it is difficult to reliably determine which associations between workplace stressors and ITL are strongest as the data are pooled from different studies where most respondents are completing diverse measures of work demands (e.g. He et al., Citation2020; Kim & Kao, Citation2014; Park & Min, Citation2020). Additionally, most studies are not concurrently completing measures of job resources (Kim & Kao, Citation2014) or coping (He et al., Citation2020; Park & Min, Citation2020), so comparing the associations among constructs with ITL is problematic given employees within each meta-analysis of the work constructs with ITL come from different regions and occupations. A better way to identify the strongest predictors of ITL - to inform evidence-based intervention- is with a homogenous measure of workplace stress where employees provide responses on each of the key components of intrinsic and extrinsic work stress. The effort-reward imbalance (ERI; Siegrist, Citation1996) model of workplace stress is well-situated to fill this void.

The ERI measure was developed in concert with the ERI model (Siegrist, Citation1996) which purports that when an employee receives less reward than the effort expended, an effort-reward imbalance occurs, and workplace stress ensues which increases the risk of poor health (Siegrist, Citation2010). This ERI reflects the job-related characteristics of the workplace, however, the model also includes “overcommitment” (OC). As an intrinsic component of the ERI model, OC is characterised by an employee’s excessive ambition in combination with a strong desire for approval and esteem (Kinman & Jones, Citation2008). An overcommitted employee tends to over-invest in their work efforts and has difficulty withdrawing from their work (Feldt et al., Citation2016). The ERI model hypothesises that; (i), the individual components of effort (e.g. physical, emotional, psychological demands), reward (e.g. job security, opportunity for promotion, remuneration, esteem) and overcommitment (OC; a measure of maladaptive coping) will be associated with negative outcomes; (ii), the imbalance between efforts and rewards (e.g. ERI ratio) will have a stronger association with the outcome than any of the individual factors (efforts, rewards, OC) in isolation; and (iii) that OC moderates the effects of ERI on poor health (Siegrist & Li, Citation2016). Meta-analyses of the ERI model show it to be a strong predictor of health conditions such as coronary heart disease (Dragano et al., Citation2017), depression ( Rugulies et al., Citation2017), and dysregulated physiological responses (Eddy et al., Citation2016; Eddy et al., Citation2018, Citation2023), and mounting evidence appears to link the ERI model with ITL. Although the growing body of research (e.g. Fei et al., Citation2022; Hasselhorn et al., Citation2004; Jiang et al., Citation2022) is demonstrating the usefulness of the ERI in predicting ITL, a synthesis of these data is required to ascertain which components are most associated with an ITL.

Workplace stress models such as the ERI model can assess the separate contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on employees’ ITL. Understanding if it is aspects of the workplace (efforts, reward, ERI) or maladaptive coping (OC) that is most associated with intentions to leave the occupation will provide an evidence-base to guide policy and inform person-focused or structural-level intervention(s). In addition, examining the role of potential moderators such as gender, occupation, or magnitude of stress within the workplace will further articulate the matching of intervention(s) to employee. The effects of workplace stress may differ between genders. For instance, work stress has been associated with poorer physical health in men but poorer mental health in women (Li et al., Citation2006; Mensah, Citation2021). Additionally, in the large Whitehall II study, women experienced higher workplace stress, depressive symptoms and inflammation than men, and in women only, higher depressive symptoms mediated the association between work stress and higher inflammation (Piantella et al., Citation2021). It is unclear, however, if the impact of workplace stress on ITL the workplace is gender-specific.

The aim of the present meta-analysis is to examine the relationships between ERI, OC, effort, and reward and the outcome of ITL. Specifically, we will assess (i), if ERI is associated with an ITL or if the association is driven by higher efforts or lower rewards (ii), if the intrinsic component OC or the extrinsic component ERI, is most associated with ITL, and (iii), if gender, occupation, or the magnitude of the stress reported by the sample, moderates the association(s) of the work stress constructs with ITL.

Method

Procedure

The first systematic search was conducted in September 2022 and the final search was repeated in June 2023 for relevant papers published since the introduction of the ERI model (Siegrist) in 1996. The search strategy was: (effort-reward imbalance OR overcommitment) AND (turnover OR quit* OR leav* OR exit*). The search was limited to English language and peer-reviewed journals.

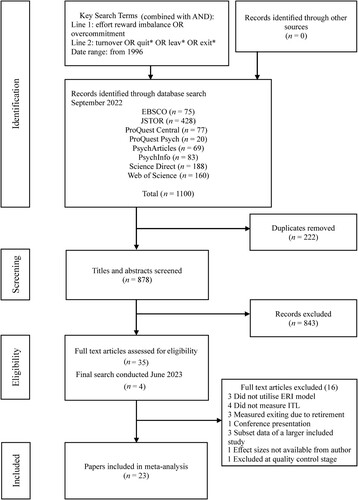

A total of 1100 articles were identified through our initial database search (EBSCO: 75, JSTOR: 428, ProQuest Central: 77, ProQuest Psych: 20, PsycArticles: 69, PsychInfo: 83, ScienceDirect: 188, and Web of Science: 160). The study selection is depicted in .

Study eligibility

After duplicates were removed, 878 articles were screened by title, abstract and keywords. Thirty-five articles were included in the full-text review. The updated search yielded an additional four articles. Two authors (MJ, RC) independently reviewed the full texts for inclusion in the meta-analysis. There were no disagreements on which studies should be included or excluded. Although the Asgarian et al. (Citation2022) article met the inclusion criteria, the reported ERI of 70.6 seems improbable and was possibly calculated by summing the component scores (efforts, rewards, and OC) rather than calculating a ratio from efforts and rewards. Due to the lack of confidence in the data scoring and interpretation, it was excluded with full consensus from our team. The exclusion criteria are presented in .

Table 1. Exclusion Criteria for Study Inclusion in the Meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Each article was read, analysed, and coded by one author and reviewed independently by a second author; intercoder reliability was satisfactory with both coders in total agreement with the data extracted. As such, a third reviewer was not required to resolve discrepancies.

Quality assessment

To assess the quality of the publication, each included paper was read, analysed, and coded independently by two authors, with disagreements resolved quickly by discussion until a consensus was met. The study quality was assessed using a modified version of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (Moola et al., Citation2017) guidelines for appraising cross-sectional research. The JBI contains eight items and was scored 0, no problem, 1, minor problem, or 2, major problem. The included studies scored a mean of 1.26 out of a possible 16.

Data analysis

The Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA) software (version 3; Borenstein et al., Citation2005) contains in-built algorithms to convert raw data or effect sizes to various other effect sizes. Effect sizes for each study were either retrieved from the article or calculated or converted to an r value using the CMA software from information within the article, or the r value was requested from corresponding authors. Effect sizes from individual studies for each sub-group (ERI, OC, effort, reward) were combined using random-effects models to produce an aggregated effect size. Since the intentions to leave the workplace (ITL) outcomes varied by measure, they were classified into two categories: intention to leave the current job (ITLJ) and intention to leave the profession (ITLP). Fourteen studies measured ITLJ, while ten studies measured ITLP. The differences in effect sizes of ITLJ and ITLP were assessed. The heterogeneity of each sub-group was estimated by the Q statistic and evaluated using the I² statistic, which suggests scores of 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 correspond respectively with low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). Meta-regression was used to assess if the inclusion of gender, occupation, or magnitude of the stress (mean ERI) of the sample reduced this heterogeneity. As there were too few studies concurrently reporting ERI, OC and ITL scores, we were unable to assess if OC moderated the ERI-ITL association.

Publication bias was considered through visual assessment of funnel plots and Egger’s r calculations. The Fail-safe N was used to assess how robust the meta r values were as this metric informs how many additional studies with an r of zero would be required to render a significant association non-significant.

Results

Study characteristics

The main characteristics of the 23 included studies were tabulated (). The selected studies included 73,671 participants, with individual sample sizes ranging between 98 (Greenham et al., Citation2019) and 21,729 (Hasselhorn et al., Citation2004). This meta-analysis focused on cross-sectional studies only as there are limited prospective studies examining the relationships between ERI and ITL. To our knowledge, the ERI-ITL relationship has only been examined in two prospective studies: the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH) study (Leineweber et al., Citation2021) and the European Nurses’ Early Exit (NEXT) study (see Derycke et al., Citation2010; Li et al., Citation2011; Li et al., Citation2013). These NEXT study articles were not included in this meta-analysis as their baseline data were a subset of a larger included cross-sectional study (Hasselhorn et al., Citation2004). To harmonise our approach with the cross sectional studies, for the prospective study included in the meta-analysis (Leineweber et al., Citation2021), only the effect sizes from baseline data were used. The majority of the sample was female, one study was limited to females only (Tei-Tominaga et al., Citation2018), and 16 others were predominantly female. The employee occupations were categorised as academics (three), health workers (twelve), educators (three), or other (five).

Table 2. Summary of Characteristics of Studies Included in the Meta-analysis.

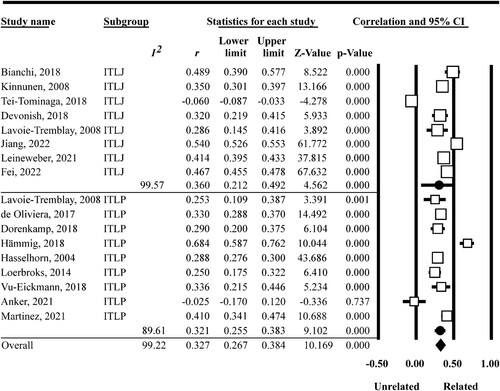

ERI and intention to leave work

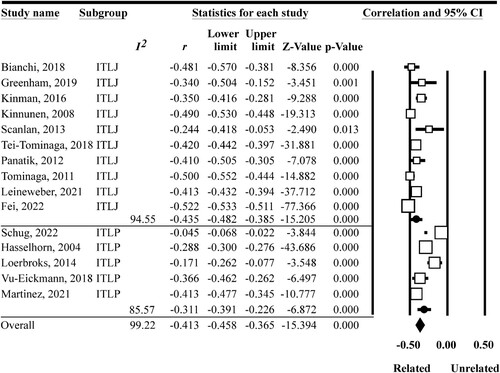

Higher ERI was related to higher intention to leave work (k = 17, r = .33, p < .001) for the combined outcomes (ITLJ and ITLP). Subgroup analysis revealed that there was no difference in effect size between outcomes assessing ITLJ (k = 8, r = .36, p < .001) or ITLP (k = 9, r = .32, p < .001), Qbetween = 0.25, df = 1, p = .62 (). Evaluation of a funnel plot of results for the combined outcomes indicated more studies toward the right, suggesting the possibility of publication bias. Egger’s regression, however, indicated that asymmetry was not significant (p (2-tailed) = .65). Additionally, Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method indicated it was unlikely there were missing studies. The Fail-Safe N analysis revealed that the meta r finding was robust; 22510 more studies with an r value of zero would be required to render the current association non-significant.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of the Association Between Effort-Reward Imbalance and Intention to Leave.

Note. ITLJ = intention to leave the job, ITLP = intention to leave the profession.

As the heterogeneity was high, I² = 99.22, Q = 2048.85, df = 16, p < .001, it was appropriate to assess if potential moderators reduced the heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). Moderation analyses were conducted using meta-regression to assess if the covariates mean ERI, the female percentage of N, or occupation (health workers, educators, others) reduced the between-study heterogeneity. The meta-regression findings (k = 13, with moderator information) revealed that when the covariates were added to the model simultaneously, I² was significantly reduced R² = .53, I² = 97.92, Q = 336.42, df = 7, p < .001. The magnitude of stress (mean ERI, p = .008) attenuated the association between ERI and intention to leave work. Specifically, the association between higher ERI and intention to leave work was higher within samples that reported a higher magnitude of stress. Gender, p = .81 and occupation (educators, health workers, others), p = .61 did not attenuate the association between ERI and intention to leave work.

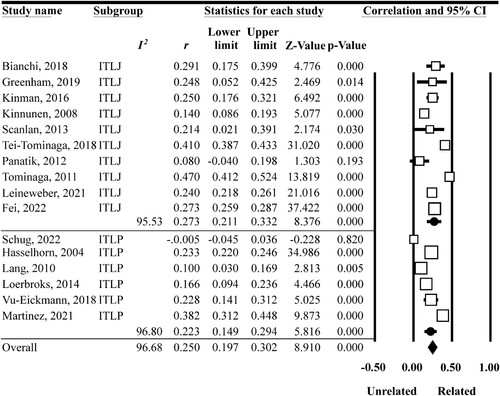

Overcommitment and intention to leave work

There was a significant association between higher OC and a higher intention to leave work (k = 13, r = .26, p < .001). There was no difference in effect size between outcomes assessing ITLJ (k = 7, r = .28, p < .001) or ITLP (k = 6, r = .22, p < .001), Qbetween = 0.95, df = 1, p = .33 (). Evaluation of a funnel plot of results for the combined outcomes indicated more studies toward the right, suggesting the possibility of publication bias. Egger’s regression however indicated that asymmetry was not significant (p (2-tailed) = .58). Additionally, Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method indicated it was unlikely there were missing studies. The Fail-Safe N analysis revealed that the meta r finding was robust; 5,249 more studies with an r value of zero would be required to render the current association non-significant.

Figure 3. Forest Plot of the Association Between Overcommitment and Intention to Leave.

Note. ITLJ = intention to leave the job, ITLP = intention to leave the profession.

As the heterogeneity was high, I² = 97.41, Q = 463.94, df = 12, p < .001, it was appropriate to assess if potential moderators reduced the heterogeneity. Moderation analyses were conducted to assess if the covariates mean ERI, or female percentage of N, or occupation (health workers, educators, others) reduced the between-study heterogeneity. Meta regression analyses were conducted singularly for each moderator (mean ERI (k = 8), the female percentage of N (k = 12), and occupation (health workers, educators, others, k = 13)) as there were not enough studies for all to be entered simultaneously. The meta regression findings revealed that gender, R² < .01, I² = 97.41, Q = 386.61, df = 10, p < .001, mean ERI, R² < .001, I² = 98.23, Q = 339.73, df = 6, p < .001 or occupation, R² = < .01, I² = 97.97, Q = 443.28, df = 9, p < .001 did not moderate the association between OC and intentions to leave work.

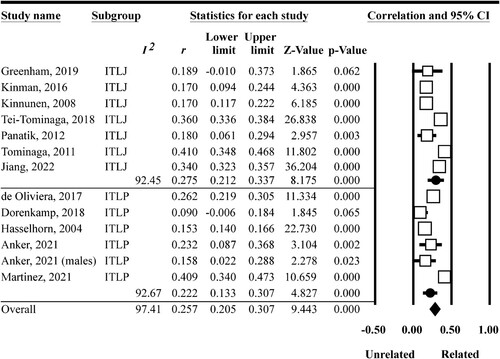

Effort and intention to leave work

Higher perceptions of work efforts were associated with an intention to leave work (k = 16, r = .25, p < .001). There was no difference in effect size between outcomes assessing ITLJ (k = 10, r = .27, p < .001) or ITLP (k = 6, r = .19, p = .001), Qbetween = 2.04, df = 1, p = .15 (). Evaluation of a funnel plot of results for the combined outcomes indicated more studies toward the right, suggesting the possibility of publication bias. Egger’s regression however indicated that asymmetry was not significant (p (2-tailed) = .73). Additionally, Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method indicated it was unlikely there were missing studies. The Fail-Safe N analysis revealed that the meta r finding was robust; 8,655 more studies with an r value of zero would be required to render the current association non-significant.

Figure 4. Forest Plot of the Association Between Effort and Intention to Leave.

Note. ITLJ = intention to leave the job, ITLP = intention to leave the profession.

As the heterogeneity was high, I² = 96.68, Q = 451.24, df = 15, p < .001, it was appropriate to assess if potential moderators reduced the heterogeneity. Meta regression analyses were conducted singularly for each moderator; mean ERI (k = 9), the female percentage of N (k = 15), and occupation (health workers, educators, others, k = 16) as there were not enough studies for all to be entered simultaneously. The meta-regression findings revealed I² was significantly reduced when gender, R² = .15, I² = 96.17, Q = 339.51 df = 13, p = .01 was added to the model. Specifically, the association between higher efforts and intention to leave work was higher within samples that included more female employees (p = .01). Neither mean ERI, (p = .33), nor occupation, (p = .31), attenuated the relationship between effort and intention to leave work.

Reward and intention to leave work

Lower perceptions of work rewards were significantly associated with an intention to leave the workplace (k = 15, r = -.41 p < .001). The effect size between outcomes assessing ITLJ (k = 10, r = -.44, p < .001) and ITLP (k = 5, r = -.26, p = .001) differed, Qbetween = 5.81, df = 1, p = .016 (). As such, the outcomes were treated separately in moderation analyses. Evaluation of a funnel plot of results for both outcomes indicated more studies toward the left, suggesting the possibility of publication bias. Egger’s regression however indicated that asymmetry was not significant (p (2-tailed) > .999). Additionally, Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method indicated it was unlikely there were missing studies. The Fail-Safe N analysis revealed that the meta r finding was robust; 20,419 more studies with an r value of zero would be required to render the current association between rewards and ITL non-significant.

Figure 5. Forest Plot of the Association Between Reward and Intention to Leave.

Note. ITLJ = intention to leave the job, ITLP = intention to leave the profession.

As the heterogeneity was high, I² = 99.23, Q = 1801.28, df = 14, p < .001, it was appropriate to assess if potential moderators for each measure of ITLJ and ITLP reduced the heterogeneity.

Reward and ITLJ. Meta-regression analyses were conducted to assess if the female percentage of N (k = 9), ERI mean (k = 5), or occupation (health workers, educators, others, k = 10) moderated the association between rewards and ITLJ. The meta-regression findings revealed that I² was not reduced when gender, R² < .01, I² = 94.76, Q = 133.50, df = 7, p = .86, ERI mean, R² = < .04, I² = 96.21, Q = 79.07, df = 3, p = .56, or occupation R² = .02, I² = 93.37, Q = 90.47, df = 6, p = .72 were added to the model.

Reward and ITLP. Assessing moderators in the ITLP studies showed that gender moderated the association between rewards and ITLP. Specifically, studies with a greater proportion of males were more likely than females to report an intention to leave the profession when rewards were low, k = 5, R² = .68, I² = 90.86, Q = 32.84, df = 3, p = .02. Neither ERI mean k = 4, R² < .001, I² = 90.20, Q = 20.42, df = 2, p = 61, or occupation type k = 5, R² < .001, I² = 99.46, Q = 368.57, df = 2, p = .72, moderated the association with ITLP.

Occupation type and intention to leave work

Given the variety of occupations included in the meta analysis, sub-group analysis by occupation type was conducted. Occupation type moderated the association between OC and ITL (Q = 9.38, p = .03). Specifically, health employees with higher OC were more likely to report an ITL than academics (Q = 9.29, p = .01) and “other” (Q = 6.98, p = .01) employees. Academics, educators, and others did not differ in the magnitude of association between OC and ITL. Occupation did not moderate the association of ERI, effort or reward with ITL (). Finally, a subgroup assessment of differences in effect size by outcome (ERI, OC, effort, reward) revealed that reward had a stronger association with intention to leave work than ERI (Q = 102.69, p < .001), OC (Q = 115.69, p < 0.01), and effort (Q = 118.80, p < .001). All other contrasts were non-significant.

Table 3. Associations Between Effort-Reward Imbalance, Overcommitment, Efforts, and Rewards and Intentions to Leave by Occupation.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis synthesised the associations between ERI, effort, reward, and OC, with turnover intentions in a sample of 73,671 employees. Our analysis revealed that higher ERI, effort, and OC and lower rewards were associated with higher turnover intentions. Rewards (r = -.413, CI: -.46, -.37) were more strongly associated with ITL than ERI (r = .327, CI: .27, .38), OC (r = .257, CI: .21, .31), and effort (r = .250, CI: .20, .30). Additionally, samples with more females were more likely than males to have an ITL when efforts were high, and samples with more males were more likely than females to have an ITLP when rewards were low. The association between OC and ITL was stronger in health workers than in other occupations. Finally, the association between ERI and ITL was strongest in samples that reported higher workplace stress. With the exception of the rewards to ITL association, the effect sizes did not differ between studies with ITLJ or ITLP outcomes.

Workplace stress (ERI, effort and rewards) and ITL

Our findings showed that an ERI, high efforts, and a lack of rewards were all individually related to ITL and suggest that rewards play a stronger role in the ERI-ITL relationship than workplace efforts. Although subgroup analysis of the outcomes of ITLJ and ITLP showed no difference in the ERI-ITL effect, the association of rewards-ITLJ was greater than the effect size for the reward-ITLP. While leaving a current job for another organisation may appear to have limited impact on a profession, earlier research regarding turnover in nursing has described a withdrawal process whereby nurses may first leave their ward, followed by leaving the organisation and finally abandoning the profession (Krausz et al., Citation1995; Morrell, Citation2005).

The present meta-analysis used the composite scales of rewards in the reward-ITL association, however studies that considered subscales of rewards showed varying findings. Perceptions of career advancement and promotional prospects are negatively related to an ITL (Boag-Munroe et al., Citation2016; Leone et al., Citation2015; Li et al., Citation2013), however, job security is not related (Kinman, Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2013). Although there is some evidence that salary is related to an ITL (Almalki et al., Citation2012; He et al., Citation2020; Kinman, Citation2016; Tei-Tominaga et al., Citation2018), the vast majority of studies suggest it is the perceptions of poor pay (Gardulf et al., Citation2005; Kudo et al., Citation2006) rather than objective pay itself that lead to higher ITL, and this is supported by meta-analytic evidence (Kim & Kao, Citation2014). Esteem has also been shown to be an important factor related to ITL (Kinman, Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2013), which may provide a more malleable avenue to improve rewards than improved pay and promotion opportunities. For instance, experimental ERI research has shown how positive verbal feedback targeting esteem can lead to adaptive physiological responses to a work stressor (Brooks et al., Citation2019).

Moderators of the workplace stress with ITL relationship

The meta-analysis demonstrated that gender did not moderate the ERI, or OC to ITL relationship. This is at odds with previous research showing men are more likely to report an ITL than women (Derycke et al., Citation2010; He et al., Citation2020), with men under high strain, twice as likely to leave compared to men under low strain conditions (Söderberg et al., Citation2014, N = 940). Additionally, the effort to ITL effect was stronger for women than men, but the low reward to ITLP effect was stronger for men than women. Although this finding aligns with findings that men and women may differ in the value they attach to rewarding aspects of their work or experiences of job demands (Derycke et al., Citation2010), the finding that women had higher ITL than men when efforts were high is unusual. Specifically, in an examination of the job demands-resources (Demerouti et al., Citation2001) paradigm, the job demands→strain→turnover relationship was stronger for men, and the job resources→job-satisfaction→turnover relationship was stronger for women (Hoonakker et al., Citation2013, N = 624). Potentially, the use of the reward measure in the ERI model, the smaller sample in the Hoonakker study, or the use of meta-regression which can increase Type I error (Higgins & Thompson, Citation2004), may explain the discrepancy. Neither occupation type nor the average level of stress within the study (i.e. mean ERI) moderated the association of ERI, effort or reward with ITL. However, occupation type did moderate the association between OC and ITL. Specifically, health workers with higher OC were more likely to report an ITL than other workers (academics, managers, military reservists, attorneys, mixed samples).

Maladaptive coping (OC) and ITL

In the current meta-analysis, OC was found to be associated with turnover intentions. The magnitude of this association was moderate for health workers and small for other occupations. Previous research has provided mixed support for the association of OC (and maladaptive coping more generally) with an ITL. In the large study by Hasselhorn et al. (Citation2004), the OC-ITL relationship was present and in the expected direction, albeit weak, whereas other research failed to support the OC-ITL relationship (e.g. Derycke et al., Citation2010; Kinnunen et al., Citation2008; Tominaga & Miki, Citation2011).

Overcommitment is related to reduced job satisfaction (Huyghebaert et al., Citation2018) and there is evidence to suggest that job satisfaction moderates the association between OC and burnout (Avanzi et al., Citation2014), with both burnout (Geurts et al., Citation1998) and low job satisfaction (Al-Hamdan et al., Citation2017, Kim & Kao, Citation2014) strongly related to an ITL. As maladaptive coping is related to job dissatisfaction and ITL (Cheval et al., Citation2019), this provides the impetus to further explore the moderating or mediating pathways between OC and job satisfaction that may lead to an ITL. It was not possible to assess the proposed moderating effect of OC on ERI with an ITL in the present meta-analysis as too few studies provided the necessary data for all measures. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of these pathways will provide a clearer picture for intervention.

Strengths & limitations

To the researchers’ knowledge, this study is the first to meta-analyse the relationship between measures of the ERI model and an ITL. One strength of this study is that it is based on a large sample, with 23 primary studies and an overall sample size of 73,761. As 22 of 23 studies included in this meta-analysis were cross-sectional in nature, these findings need to be confirmed with prospective investigations before inferring causality between constructs. It is also important to note, that the moderating effect of gender on effort with ITL and rewards on ITLP may not be robust as it was based on a small proportion of male employees, with most studies recruiting a high proportion of female employees. Additionally, as intentions to leave and not actual turnover were assessed, caution should be taken interpreting our findings as evidence of ERI resulting in turnover behaviour. While the intention-behaviour gap (Sheeran & Webb, Citation2016) may restrict the interpretation of our findings as evidence of the effect of ERI predicting actual turnover, ITL is widely accepted as a strong predictor of actual turnover (Siong et al., Citation2006). There is a growing interest in physiological indices in workplace stress research, however, the current body of ERI-ITL literature has relied on self-reported evidence. Future research may be encouraged to assess if physiological measures of stress improve the prediction of an ITL the workplace.

Implications

In comparing the relative contributions of the ERI model components, our findings showed low perceived rewards to be the stronger risk factor for ITL. Based on these data, it would appear that for those reporting an ERI that increasing rewards rather than reducing job demands may be more likely to reduce ITL. The few studies that have prospectively considered what improves an ITL suggest that an increased intention to improve professional capabilities reduces an ITL (Chang et al., Citation2019; Parry, Citation2008). Of particular interest are the findings from Chang et al., who report that improved work capabilities mediate the association between outcome expectation (salary and future benefits) with a reduced ITL the profession. When this research is considered alongside the present findings, the continued prospective examination of the impact of job rewards (e.g. improved social support, salary and benefits, esteem) on an ITL appears justified- especially for male workers.

Conclusion

Although the ERI model was developed to predict adverse health outcomes, our study has demonstrated its usefulness in predicting ITL the workplace. Across a range of occupations, high ERI, OC, and efforts, and low rewards were individual risk factors for ITL. Considering the findings together, the ERI-ITL relationship is, for this large sample, driven by a perception of low rewards in the workplace. The findings from this study align with other reviews of the relationship between high workplace stress with ITL. Unlike these earlier reviews, however, the use of the ERI model in the present investigation provides an evidence-based avenue for intervention that is gender-specific (i.e. reduce demands for women, increase rewards for men) and may assist in reducing job turnover.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Hamdan, Z., Manojlovich, M., & Tanima, B. (2017). Jordanian nursing work environments, intent to stay, and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(1), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12265

- Allen, D. G., Bryant, P. C., & Vardaman, J. M. (2010). Retaining talent: Replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(2), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2010.51827775

- Almalki, M. J., FitzGerald, G., & Clark, M. (2012). The relationship between quality of work life and turnover intention of primary health care nurses in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 314–314. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-314

- Anker, J., & Krill, P. R. (2021). Stress, drink, leave: An examination of gender-specific risk factors for mental health problems and attrition among licensed attorneys. PLoS One, 16(5), e0250563–e0250563. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250563

- Asgarian, A., Abbasinia, M., Sadeghi, R., Moadab, F., Asayesh, H., Mohammadbeigi, A., Heshmati, F., & Mahdianpour, F. (2022). Relationship between effort–reward imbalance, job satisfaction, and intention to leave the profession among the medical staff of Qom University of Medical Sciences. Frontiers of Nursing, 9(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.2478/fon-2022-0002

- Avanzi, L., Zaniboni, S., Balducci, C., & Fraccaroli, F. (2014). The relation between overcommitment and burnout: Does it depend on employee job satisfaction? Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(4), 455–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2013.866230

- Bianchi, R., Mayor, E., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2018). Burnout and depressive symptoms are not primarily linked to perceived organizational problems. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 23(9), 1094–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1476725

- Boag-Munroe, F., Donnelly, J., van Mechelen, D., & Elliott-Davies, M. (2016). Police officers’ promotion prospects and intention to leave the police. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(2), https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paw033

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2005). Comprehensive Meta Analysis (version 3) [Computer Software] (3 ed). Biostat. Available from: http://www.meta-analysis.com

- Brooks, R. P., Jones, M. T., Hale, M. W., Lunua, T., Dragano, N., & Wright, B. J. (2019). Positive verbal feedback about task performance is related with adaptive physiological responses: An experimental study of the effort-reward stress model. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 135, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.11.007

- Chang, H. Y., Lee, I. C., Chu, T. L., Liu, Y. C., Liao, Y. N., & Teng, C. I. (2019). The role of professional commitment in improving nurses’ professional capabilities and reducing their intention to leave: Two-wave surveys. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(9), 1889–1901. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13969

- Cheval, B., Cullati, S., Mongin, D., Schmidt, R. E., Lauper, K., Pihl-Thingvad, J., Chopard, P., & Courvoisier, D. S. (2019). Associations of regrets and coping strategies with job satisfaction and turnover intention: International prospective cohort study of novice healthcare professionals. Swiss Medical Weekly, 149, w20074–w20074. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20074

- Demerouti, E., Nachreiner, F., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- de Oliveira, D. R., Griep, R. H., Portela, L. F., & Rotenberg, L. (2017). Intention to leave profession, psychosocial environment and self-rated health among registered nurses from large hospitals in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1949-6

- Derycke, H., Vlerick, P., Burnay, N., Decleire, C., D'Hoore, W., Hasselhorn, H. M., & Braeckman, L. (2010). Impact of the effort-reward imbalance model on intent to leave among Belgian health care workers: A prospective study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 879–893. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X477594

- Dess, G. G., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). Voluntary turnover, social capital, and organizational performance. The Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/259187

- Devonish, D. (2018). Effort-reward imbalance at work: The role of job satisfaction. Personnel Review, 47(2), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2016-0218

- Dodoo, J. E., & Al-Samarraie, H. (2019). Factors leading to unsafe behavior in the twenty first century workplace: A review. Management Review Quarterly, 69(4), 391–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00157-6

- Dorenkamp, I., & Weiß, E.-E. (2018). What makes them leave? A path model of postdocs’ intentions to leave academia. Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research, 75(5), 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0164-7

- Dragano, N., Siegrist, J., Nyberg, S. T., Lunau, T., Fransson, E. I., Alfredsson, L., Bjorner, J. B., Borritz, M., Burr, H., Erbel, R., & Fahlén, G. (2017). Effort-reward imbalance at work and incident coronary heart disease: A multi-cohort study of 90,164 individuals. Epidemiology, 28(4)(4), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000666

- Eddy, P. J., Heckenberg, R., Wertheim, E. H., Kent, S., & Wright, B. J. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effort-reward imbalance model of workplace stress with indicators of immune function. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 91, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.10.003

- Eddy, P. J., Wertheim, E. H., Hale, M. W., & Wright, B. J. (2018). The salivary alpha amylase awakening response is related to over-commitment. Stress, 21(3), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2018.1428553

- Eddy, P. J., Wertheim, E. H., Hale, M. W., & Wright, B. J. (2023). A systematic review and revised meta-analysis of the effort-reward imbalance model of workplace stress and HPA axis measures of stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 85(5), https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000001155

- Fei, Y., Fu, W., Zhang, Z., Jiang, N., & Yin, X. (2022). The effects of effort-reward imbalance on emergency nurses’ turnover intention: The mediating role of depressive symptoms. Journal of Clinical Nursing, https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16518

- Feldt, T., Hyvönen, K., Mäkikangas, A., Rantanen, J., Huhtala, M., & Kinnunen, U. (2016). Overcommitment as a predictor of effort—reward imbalance: Evidence from an 8-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 42(4), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3575

- Gardulf, A. N. N., Söderström, I.-L., Orton, M.-L., Eriksson, L. E., Arnetz, B., & Nordström, G. U. N. (2005). Why do nurses at a university hospital want to quit their jobs? Journal of Nursing Management, 13(4), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2934.2005.00537.x

- Geurts, S., Schaufeli, W., & De Jonge, J. (1998). Burnout and intention to leave among mental health-care professionals: A social psychological approach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(3), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1998.17.3.341

- Greenham, J. C. M., Harris, G. E., Hollett, K. B., & Harris, N. (2019). Predictors of turnover intention in school guidance counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 47(6), 727–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2019.1644613

- Hämmig, O. (2018). Explaining burnout and the intention to leave the profession among health professionals – A cross-sectional study in a hospital setting in Switzerland. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3556-1

- Harvey, S. B., Modini, M., Joyce, S., Milliigan-Saville, J. S., Tan, L., Mykletun, A., Bryant, R. A., Christensen, H., & Mitchell, P. B. (2017). Can work make you mentally ill? A systematical meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 74(4), 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-104015

- Hassard, J., Teoh, K. R. H., Visockaite, G., Dewe, P., & Cox, T. (2018). The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000069

- Hasselhorn, H. M., Tackenberg, P., Peter, R., & Group, N.-S. (2004). Effort-reward imbalance among nurses in stable countries and in countries in transition. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 10(4), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.401

- He, R., Liu, J., Zhang, W.-H., Zhu, B., Zhang, N., & Mao, Y. (2020). Turnover intention among primary health workers in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 10(10), e037117–e037117. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037117

- Heavey, A. L., Holwerda, J. A., & Hausknecht, J. P. (2013). Causes and consequences of collective turnover: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(3), 412–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032380

- Higgins, J., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. www.handbook.cochrane.org

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Thompson, S. G. (2004). Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Statistics in Medicine, 23(11), 1663–1682. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1752

- Hoonakker, P., Carayon, P., & Korunka, C. (2013). Using the Job-Demands-Resources model to predict turnover in the information technology workforce – General effects and gender. Horizons of Psychology, 22, 51–65. https://doi.org/10.20419/2013.22.373

- Huyghebaert, T., Gillet, N., Beltou, N., Tellier, F., & Fouquereau, E. (2018). Effects of workload on teachers’ functioning: A moderated mediation model including sleeping problems and overcommitment. Stress and Health, 34(5), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2820

- Jiang, N., Zhang, H., Tan, Z., Gong, Y., Tian, M., Wu, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, J., Chen, Z., Wu, J., Lv, C., Zhou, X., Yang, F., & Yin, X. (2022). The relationship between occupational stress and turnover intention among emergency physicians: A mediation analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 901251–901251. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.901251

- Kim, H., & Kao, D. (2014). A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among U.S. child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 47(3), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.015

- Kinman, G. (2016). Effort-reward imbalance and overcommitment in UK academics: implications for mental health, satisfaction and retention. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(5), 504–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1181884

- Kinman, G., & Jones, F. (2008). Effort-reward imbalance, over-commitment and work-life conflict: Testing an expanded model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(3), 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810861365

- Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., & Makikangas, A. (2008). Testing the effort-reward imbalance model among Finnish managers: The role of perceived organizational support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(2), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.114

- Krausz, M., Koslowsky, M., Shalom, N., & Elyakim, N. (1995). Predictors of intentions to leave the ward, the hospital, and the nursing profession: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(3), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160308

- Kudo, Y., Satoh, T., Hosoi, K., Miki, T., Watanabe, M., Kido, S., & Aizawa, Y. (2006). Association between intention to stay on the job and job satisfaction among Japanese nurses in small and medium-sized private hospitals. Journal of Occupational Health, 48(6), 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.48.504

- Lang, J., Bliese, P. D., Adler, A. B., & Hölzl, R. (2010). The role of effort-reward imbalance for reservists on a military deployment. Military Psychology, 22(4), 524. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2010.521731

- Lavoie-Tremblay, M., O'Brien-Pallas, L., Gélinas, C., Desforges, N., & Marchionni, C. (2008). Addressing the turnover issue among new nurses from a generational viewpoint. Journal of Nursing Management, 16(6), 724. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2934.2007.00828.x

- Leineweber, C., Bernhard-Oettel, C., Eib, C., Peristera, P., & Li, J. (2021). The mediating effect of exhaustion in the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and turnover intentions: A 4-year longitudinal study from Sweden. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), e12203–e12n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12203

- Leone, C., Bruyneel, L., Anderson, J. E., Murrells, T., Dussault, G., Henriques de Jesus, É, Sermeus, W., Aiken, L., & Rafferty, A. M. (2015). Work environment issues and intention-to-leave in Portuguese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Health Policy, 119(12), 1584–1592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.09.006

- Li, J., Galatsch, M., Siegrist, J., Müller, B. H., & Hasselhorn, H. M. (2011). Reward frustration at work and intention to leave the nursing profession—Prospective results from the European longitudinal NEXT study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(5), 628–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.011

- Li, J., Shang, L., Galatsch, M., Siegrist, J., Müller, B. H., & Hasselhorn, H. M. (2013). Psychosocial work environment and intention to leave the nursing profession: A cross-national prospective study of eight countries. International Journal of Health Services, 43(3), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.43.3.i

- Li, J., Yang, W., & Cho, S. (2006). Gender differences in job strain, effort-reward imbalance, and health functioning among Chinese physicians. Social Science and Medicine, 62(5), 1066–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.011

- Loerbroks, A., Meng, H., Chen, M.-L., Herr, R., Angerer, P., & Li, J. (2014). Primary school teachers in China: Associations of organizational justice and effort-reward imbalance with burnout and intentions to leave the profession in a cross-sectional sample. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 87(7), 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-013-0912-7

- Martinez, M. C., De Oliveira, M. D. R. D., & Fischer, F. M. (2022). Factors associated with work ability and intention to leave nursing profession: A nested case-control study. Industrial Health, 60(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2021-0085

- Mensah, A. (2021). Job stress and mental well-being among working men and women in Europe: The mediating role of social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052494

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K., & Mu, P.-F. (2017). Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In E. Aromaros, & Z. Munn (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

- Morrell, K. (2005). Towards a typology of nursing turnover: The role of shocks in nurses' decisions to leave. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(3), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03290.x

- Panatik, S. A. B., Rajab, A., Shaari, R., Saat, M. M., Wahab, S. A., & Noordin, N. F. M. (2012). Psychosocial work condition and work attitudes: Testing of the effort-reward imbalance model in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 40, 591–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.235

- Park, J., & Min, H. (2020). Turnover intention in the hospitality industry: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102599

- Parry, J. (2008). Intention to leave the profession: Antecedents and role in nurse turnover. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04771.x

- Piantella, S., Dragano, N., Marques, M., McDonald, S. J., & Wright, B. J. (2021). Prospective increases in depression symptoms and markers of inflammation increase coronary heart disease risk - The Whitehall II cohort study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 151, 110657–110657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110657

- Rugulies, R., Aust, B., & Madsen, I. E. (2017). Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(4), 294–306. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3632

- Scanlan, J. N., Meredith, P., & Poulsen, A. A. (2013). Enhancing retention of occupational therapists working in mental health: Relationships between wellbeing at work and turnover intention. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(6), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12074

- Schug, C., Geiser, F., Hiebel, N., Beschoner, P., Jerg-Bretzke, L., Albus, C., Weidner, K., Morawa, E., & Erim, Y. (2022). Sick leave and intention to quit the job among nursing staff in German hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041947

- Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12265

- Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27

- Siegrist, J. (2010). Effort-reward imbalance at work and cardiovascular diseases. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 23(3), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10001-010-0013-8

- Siegrist, J., & Li, J. (2016). Associations of extrinsic and intrinsic components of work stress with health: A systematic review of evidence on the effort-reward imbalance model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(4), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040432

- Siong, Z. M. B., Mellor, D., Moore, K. A., & Firth, L. (2006). Predicting intention to quit in the call centre industry: Does the retail model fit? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610659579

- Söderberg, M., Härenstam, A., Rosengren, A., Schiöler, L., Olin, A.-C., Lissner, L., Waern, M., & Torén, K. (2014). Psychosocial work environment, job mobility and gender differences in turnover behaviour: A prospective study among the Swedish general population. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 605. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-605

- Tei-Tominaga, M., Asakura, K., & Asakura, T. (2018). Generation-common and -specific factors in intention to leave among female hospital nurses: A cross-sectional study using a large Japanese sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081591

- Tominaga, M. T., & Miki, A. (2011). Factors associated with the intention to leave among newly graduated nurses in advanced-treatment hospitals in Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 8(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00157.x

- Vu-Eickmann, P., Li, J., Müller, A., Angerer, P., & Loerbroks, A. (2018). Associations of psychosocial working conditions with health outcomes, quality of care and intentions to leave the profession: Results from a cross-sectional study among physician assistants in Germany. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 91(5), 643–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-018-1309-4