ABSTRACT

Aphasia, a communication disability prevalent among stroke survivors, significantly impacts psychosocial well-being and quality of life. Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs) provide intensive and comprehensive treatment, incorporating individual and group therapy, patient and family education, and technology utilization. Despite positive outcomes, global implementation of ICAPs remains limited. In Brazil, preliminary evidence supports the development of intensive and comprehensive aphasia programs, such as the Brazilian Aphasia House—a program inspired by the successful Aphasia House model in the United States. The Brazilian Aphasia House offers personalized and intensive therapy in a simulated domestic environment, encompassing individual and group therapy sessions, and patient and family education, with the goal of enhancing functional communication skills and overall quality of life. Operating as a teaching clinic within a public university, it also serves as a training ground for future therapists to expand ICAP availability in Brazil. Challenges in implementing ICAPs in Brazil include socioeconomic barriers, limited public aphasia awareness, a shortage of specialized professionals, transportation, and session costs. Sustainable implementation requires committed leadership and financial resourcing, with involvement from public institutions and universities. By increasing awareness and nationwide implementation of ICAPs, access to aphasia rehabilitation services can be improved, potentially leading to better outcomes for individuals with aphasia and their caregivers. The Brazilian Aphasia House serves as an exemplar of an ICAP, offering intensive and personalized therapy to enhance communication abilities and promote social participation for people with aphasia.

Introduction

Aphasia is a communication disability acquired after a stroke that can significantly and negatively impact the quality of life in around 30% of the affected population (Engelter et al., Citation2006). Aphasia has a large range of negative psychosocial consequences including anxiety (Morris, Eccles, Ryan, & Kneebone, Citation2017), depression (Baker et al., Citation2018), reduced participation in social activities (Cruice, Worrall, & Hickson, Citation2010), significantly fewer friendships a lower likelihood of returning to work (Simmons-Mackie & Cherney, Citation2018), and significant carer burden (Blom Johansson, Carlsson, Östberg, & Sonnander, Citation2022). The quality of life of individuals with aphasia can be affected by various factors, including the severity of aphasia, limitations in activities and participation, and aspects of social networks and support (Hilari, Needle, & Harrison, Citation2012). Given the extent of the negative impacts of aphasia, speech pathology interventions need to address a wide range of targets across the domains of impairment, function, participation, environment, and personal factors. Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs) are an intervention option addressing all domains (Rose, Cherney, & Worrall, Citation2013).

ICAPs, first described by Rose and colleagues in 2013 (Rose et al., Citation2013), offer intensive and comprehensive treatment over a short period, including individual and group therapy, patient and family education, and the use of technological advances such as apps and computer therapy. Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs) adhere to specific criteria, requiring a minimum of 3 hours of daily treatment over at least two weeks. These programs utilize various treatment approaches and formats, targeting both impairment and activity/participation levels. ICAPs have a clear start and end date with group entry and exit, as outlined by Rose et al. (Citation2013). Studies have shown that ICAPs positively affect functional language, psychosocial well-being, and quality of life outcomes in individuals with chronic aphasia and their carers (Babbitt, Worrall, & Cherney, Citation2015; Dignam et al., Citation2015; Griffin-Musick, Off, Milman, Kincheloe, & Kozlowski, Citation2021; Hoover & Carney, Citation2014; Off, Leyhe, Baylor, Griffin-Musick, & Murray, Citation2022). However, to date, global ICAP implementation has been limited with a recent international survey revealing only 21 ICAPs running across the world (Rose et al., Citation2022). Given this limited program availability, it is essential to develop strategies and public policies that ensure better access to services such as ICAPs and to improve outcomes for people aphasia and their carers/family.

In their recent international survey, Rose and colleagues (Citation2022) identified programs that had some modification to the ICAP criteria which they termed modified ICAPs (mICAPs). The modifications can be in either intensity (dose) or comprehensive program elements, but not both. mICAPs may include some or all the components of an ICAP but with a modification to one core aspect, such as providing the minimum therapy hours over a slightly more extended period or omitting family education while still offering intensive individual, group, and app-based therapies.

In the Brazilian context, preliminary evidence supports further investigation and implementation of intensive and comprehensive aphasia programs. In a study conducted in Brazil, Ribeiro Lima and colleagues discovered that a moderately intensive group therapy program (3 hours per week for 12 weeks), focusing on language and functional communication improvement, resulted in significant enhancements in overall language and quality of life (Ribeiro Lima et al., Citation2021). Moreover, younger age, the presence of a caregiver, larger household size, and female gender were associated with increased quality of life, particularly in the communication domain, as measured by the SAQOL-39 (Hilari, Byng, Lamping, & Smith, Citation2003) in the same study.

A recent study on speech therapy services in Brazil revealed that most speech therapists provide acute care (until 3 months) for patients with aphasia, conducting more than three sessions per week. However, few professionals offer intensive services for patients with chronic aphasia despite the long-term negative impacts on participation, mood, and quality of life (Lima, et al., Citation2024). In Brazil, there has been a recent increase in therapists establishing support groups, aphasia associations, and artistic projects aimed at supporting people with aphasia (Abreu, Balinha, Costa, & Brandão, Citation2021).

The lack of public and professional awareness about aphasia and its significance is a critical issue that needs to be addressed. A survey conducted in the city of Florianópolis, Brazil demonstrated that most people were not clear about the causes and characteristics of aphasia, with only 8.5% of people having heard about the condition (Nascimento, Citation2015). A lack of aphasia awareness is usually associated with a lack of understanding about aphasia intervention programs, such as ICAPs. Further, lack of community awareness may result in governments and health authorities failing to comprehend the importance of investing in the development and implementation of aphasia rehabilitation services The SUS, Brazil’s public health system, encompasses primary care, medium and high complexity care, urgent and emergency services, hospital care, epidemiological, health, and environmental surveillance actions and services, as well as pharmaceutical assistance. Consequently, the creation of ICAP at the University should serve as a model for the public system to develop a similar service accessible to the entire population using the SUS. We believe it is essential to expand aphasia programs developed and delivered by Brazilian universities to encompass the scope of the Brazil Unified Health System (SUS), thereby reaching a broader segment of the population. Furthermore, it is essential to ensure accessibility to services and social inclusion programs for people with aphasia and their caregivers, including the provision of specialized transportation to promote access to rehabilitation services and full participation in society.

Studies, such as the one conducted by Cabral and colleagues in Joinville Brazil, highlight that even five years after stroke, a considerable portion of patients (20%) experience disabilities (Cabral et al., Citation2018), with aphasia affecting 22.6% of individuals (Lima et al., Citation2020). In this context, intensive therapy provided by ICAPs emerge as a unique opportunity for people with aphasia and their families during the chronic phase of recovery to benefit from intensive and personalized interventions. Considering that ICAPs are a relatively new approach in Brazil, except for the Aphasia House USP Bauru (described below), there is an opportunity to introduce and promote these services in other locations throughout the country.

Aim

This article refers to a descriptive case study on the adaptation of the Brazilian Aphasia House, an ICAP in Brazil at the University of São Paulo-Brazil.

Description of the Brazilian Aphasia House

The Brazilian Aphasia House (Casa da Afasia) offers a rehabilitation program for people with aphasia (PwA) focusing on enhancing communication. Rather than operating from a hospital or outpatient setting, the Brazilian Aphasia House operates as a teaching clinic within a public University in Bauru City, São Paulo, Brazil. The program was started as a research project called “Stroke: risk factors, health promotion and innovations in the language rehabilitation process and public health policies – actions of a multidisciplinary group” supported by the Foundation of the State of São Paulo, Brazil (process number 2015/16862-7). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Public University of São Paulo, USP, Brazil (53782416.2.0000.54177).

The Brazilian Aphasia House can be considered an ICAP as it: a) provides an intensive dose (with a specific start and end date) with a minimum of four hours of daily treatment over a period of at least four weeks (minimum 100 hours) exceeding the ICAP minimum dose (30 hours over two weeks; b) is comprehensive in scope, utilising individual and group therapy and including patient/family education and computer therapy; c) targets both the impairment and the activity/participation levels of language and communication functioning.

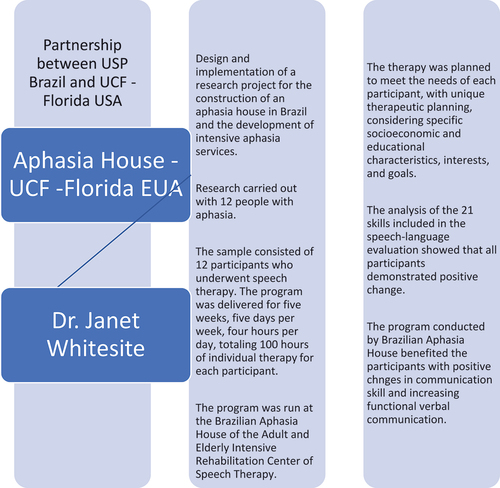

The Brazilian Aphasia House program was modelled on the Aphasia House at the University of Central Florida (UCF), USA, (Helm-Estabrooks & Whiteside, Citation2012; Whiteside & Kong, Citation2014). Personalized goal setting is used to improve patient motivation, response to rehabilitation, satisfaction with outcomes, and increase autonomy, and goals are actioned in a highly communicatively accessible environment. describes the development and implementation phases of the aphasia house in Brazil, in accordance with The FRAME (Wiltsey Stirman et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1a. Development and implementation phases of the aphasia house in Brazil (Stirman et al., 2019). Phase 1 - Elaboration and development of a research project with the aim of describing scientific evidence for the Brazilian population. “Stroke: risk factors, health promotion and innovations in the language rehabilitation process and public health policies – actions of a multidisciplinary group. ”Supported by the Foundation of the State of São Paulo, Brazil (process number 2015/16862-7)

For the adaptation of the Aphasia House in Brazil some modifications were necessary regarding the physical structure. For example, at the UCF Aphasia House in the United States there is a room that represents the garage, while in Brazil the garage has the sole function of storing a car, therefore this room was replaced by an office. Another difference is that in Brazil the house was built in repurposed sea shipping containers because the foundation that financed the project did not provide for the construction of a building, however, the purchase of containers was possible. The Brazilian Aphasia House is a teaching clinic that resembles the physical structure of a house. In this environment there is a TV room, bedroom, kitchen, office and a space for group programs. Each room is furnished to simulate the rooms of a house, keeping the characteristics close to a domestic environment (see Appendix A for photographs of these contexts).

The creation and implementation of therapy within these environments aims to establish personalized goals for patients, targeting their communication difficulties, and proposing functional strategies that can improve their autonomy during communication in family and social contexts. Such programming specifically addresses systematic, intensive and individualized intervention, incorporated into an everyday and realistic environment, with the aim of maximising generalisation of therapy effects to everyday functional communication abilities.

The Aphasia House conducts therapies for individuals with aphasia who enroll through a waiting list based on spontaneous demand. A screening process is then undertaken to select and form a group of participants, adhering to the inclusion criteria. Approximately 10 individuals with aphasia are chosen for each module, conducted once per semester. The inclusion criteria include: a medical diagnosis of cerebral vascular accident (CVA), with an absence of thrombolysis; diagnosis of expressive aphasia; adults; both male and female; injury time between 0 and 24 months; and no prior speech therapy for aphasia-related changes. Each day, each person with aphasia and a therapist spends an hour in each of the rooms in the house, with specific work objectives, keeping the same therapist for the day (see ). The therapies take place during the morning from 8am to 12noon. Each program was carried out with 3 groups of 4 participants.

Figure 1b Phase 2 - Adapting the results of the research to offer the program to the Brazilian population- What is modified?

Table 1. Rotation between participant with aphasia, therapeutic environments, hours and speech therapists.

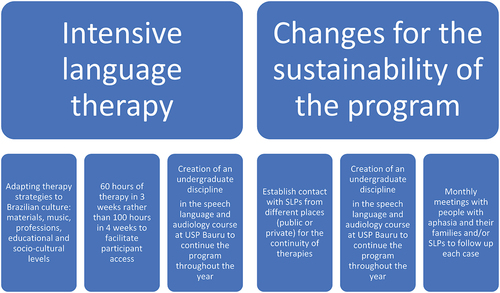

The Brazilian Aphasia House intervention program follows a multisensory model with objects and actions used in Brazilian life routies. Typical foods (e.g., mango, papaya, banana, rice, beans, salad, meat), typical festivals of each region of the country, and specific cultural references unique to Brazil were included. The therapy materials included discussions about traditional Brazilian cuisine, such as feijoada (a black bean stew with pork) and brigadeiro (a popular chocolate sweet). The therapy sessions also incorporated references to Brazilian music, discussing famous Brazilian musicians. This not only engaged the participants but also provided a cultural context that was familiar and meaningful to them, and language practice that could be directly implemented in their everyday lives. Additionally, the program considered the cultural values of personal relationships and social interaction. Brazilian culture places a strong emphasis on social connections, so group activities and opportunities for socialization were incorporated into the program. This included encouraging participants to engage in conversations about Brazilian social events, such as Carnaval and Festa Junina (i.e., June Festival). Overall, the modifications made to the US Aphasia House for its Brazilian version aimed to create a program that was culturally sensitive and relevant to the needs and experiences of the Brazilian participants.

In the Brazilian Aphasia House, undergraduate and graduate students (master’s and doctoral) deliver the therapy supervised by a professor, with the objective of building capacity by training new therapists that could implement the program in the future in different regions of Brazil. A unique therapeutic plan is made for each patient based on their specific socioeconomic and educational background, interests, and communication needs. Therapy is aimed at improving the use of oral and written language, focusing on both formal and functional language across phonologic, semantic, syntactic, and pragmatic levels. Levels of language are activated by repetitive stimuli. Auditory, articulatory, visual, olfactory and gustatory models are used, preferably using real objects that available in each room of the house. All therapy tasks are performed in routine and functional situations, quite similar to the situations that happen in a domestic environment. In addition to the individual sessions, on Fridays there are four hours of group therapy with topics that were discussed individually during the week. Group conversation also takes place during breaks between therapy sessions. The group interaction assists in enhancing well-being and stimulates identity reconstruction, thus promoting the recovery of discursive skills and social bonds.

Education/guidance sessions for family members and/or caregivers are delivered by a speech and language therapist, a neurologist, and a psychologist. A range of topics are covered, for example: How can the family help with speech therapy; What is the purpose of the group meetings?; What is aphasia?; Changes in communication and behaviour; Facilitating communication strategies; The multidisciplinary team and the family (da Silva Michelini & de Lourdes Caldana, Citation2005). Family members are also able to discuss the daily challenges they may face, with the view to improve the quality of life of the person with aphasia and their family.

Studies Carried out at the Brazilian Aphasia House

As part of the university, the Brazilian Aphasia House is dedicated to providing care for individuals with aphasia, guided by studies conducted with undergraduate and postgraduate students. These studies demonstrate favourable scientific evidence tailored to the needs of the Brazilian population, aligning with international research (Helm-Estabrooks & Whiteside, Citation2012; Whiteside & Kong, Citation2014).

In 2020, a research study was conducted by Marina Godoy, a doctoral student supported by the Faculty of Dentistry of Bauru. The study aimed to investigate the impacts of providing information about stroke and aphasia, as well as addressing the needs and burden of family caregivers, stress, and coping strategies (Godoy, Citation2020). A booklet was developed specifically for family caregivers, focusing on their practical and emotional needs. Twelve family members of patients undergoing rehabilitation at the Brazilian Aphasia House participated in the study (Godoy, Citation2020). All questionnaires used in the study were translated and validated for Brazil in order to apply them to the caregivers: Informal Caregiver Burden Assessment Questionnaire (QASCI) (Monteiro, Mazin, & Dantas, Citation2015); Stress Symptoms Inventory for Adults (Lipp & de Hoyos Guevara, Citation1994); and the Inventory of Stress Strategies Coping (Savóia, Santana, & Mejias, Citation1996). The development of the carer booklet was based on a literature review, including indexed scientific articles and official websites, as well as previous research (Carleto, Godoy, & Caldana, Citation2016), with a focus on well-received informative bulletins. The data collected from the questionnaire instruments also served as the basis for the written material, considering the observed profiles of the caregivers in terms of burden, stress, and coping strategies. The design and illustrations of the booklet were created by a designer from the Department of Educational Technology at the Faculty of Dentistry. The study indicated the need to look at caregivers and think about the emotional aspects of the reality imposed on them, who are often unprepared for sudden care and lack specific knowledge about the disease. Future research with this population is extremely important, as it is possible to further improve the quality of life of caregivers with relevant information and support.

Another postdoctoral project (Carleto, N., a post-doctoral study) in the Brazilian Aphasia House research group. The aim was to develop a multidisciplinary orientation program for family caregivers of individuals with aphasia and to analyze their burden and knowledge of the subject before and after participation in the orientation group. The multidisciplinary orientation group was designed and developed, and the Zarit Burden Interview Scale (Yap, Citation2010) and the Knowledge of Aphasia Questionnaire (Palma, Citation2014) were used before and after participation in the group. This study included 11 family caregivers who took part in the multidisciplinary guidance group. A varying degree of burden was observed prior to participation in the orientation group and, after participation, the majority had no burden and only three participants had knowledge of aphasia and its consequences. It was possible to observe the positive influence of the orientation group both on the burden of family caregivers and on knowledge about aphasia and its consequences.

Discussion

Challenges of Implementing ICAPs in Brazil

The majority of the Brazilian population depends on public healthcare and stroke is one of the main causes of disability (Cacho et al., Citation2022). According to data from the 2019 National Health Survey (PNS), 69.8% of the Brazilian population relies on the Unified Health System (SUS), while only 28.5% have private health insurance. Unfortunately, little is known about access to rehabilitation for stroke in the public health system across different Brazilian regions (Cacho et al., Citation2022). However, data concerning access to healthcare, housing and food as detailed below, suggests that access to rehabilitation after stroke will be very poor across the country.

The socioeconomic context in Brazil poses significant challenges for the inclusion of individuals with aphasia in intensive therapy programs. The data provided in 2019 by the João Pinheiro Foundation showed a housing deficit throughout Brazil of around 5.8 million dwellings, with an increasing trend in the deficit. On the other hand, there were 2,814,000 unoccupied dwellings due to the high cost of rents (Tamietti & Tamietti, Citation2024). There is considerable food stress in Brazil with more than half (58.7%) of the Brazilian population (Guedes, Citation2022) living with so-called food insecurity. The affordability and accessibility of food can pose significant challenges for individuals with aphasia. This is particularly relevant in the context of caregivers who often need to accompany the patient to therapy sessions, potentially leading to a disruption in their own employment and income. Consequently, the financial strain experienced by caregivers may impact their ability to purchase an adequate and nutritious food supply for both themselves and the individual with aphasia. Another key area affected by socioeconomic status is transportation, as many individuals may face difficulties in accessing therapy centers due to limited financial resources or inadequate public transportation infrastructure.

Another critical aspect impacting aphasia intervention in Brazil is the lack of national-level aphasia awareness. This lack of awareness hampers the early identification and referral of individuals with aphasia to appropriate services. Furthermore, the speech therapy profession in Brazil often lacks sufficient education and training in service delivery models specifically tailored for aphasia interventions. As a result, individuals with aphasia may not receive the comprehensive and specialized care they require for optimal recovery and communication improvement.

As discussed in the study conducted by Rose (Citation2022), addressing issues related to the sustainability of Intensive and Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs) during their implementation is crucial. ICAPs have proven to be an effective service delivery model (Rose et al., Citation2022), but the research revealed that 25% of participating programs in 2013 were no longer operational in 2020. This suggests the need to investigate factors that affect the sustainability of these programs. Currently, the treatment of people with aphasia at the Aphasia House in Brazil is funded by the University of São Paulo. The University incorporates the program as part of the speech-language pathology curriculum, allowing undergraduate students to gain theoretical knowledge and practical experience by participating in intensive aphasia therapy. The program is conducted under the guidance of a professor who oversees the students’ activities. This integration ensures that future professionals are adequately prepared to provide comprehensive care for people with aphasia. Planning is underway to expand the physical facilities of Aphasia House in Brazil and introduce a multidisciplinary approach to care. This expansion will encompass the integration of multiple disciplines, including physical therapy, nursing, psychology, and social work. The overall goal is to offer a comprehensive treatment approach for individuals with aphasia, addressing not only their communication impairments but also their physical, emotional, and social well-being. This project will be supported by the São Paulo state research support foundation (FAPESP).

To address the challenges and promote the sustainability of ICAPs in Brazil, it is crucial to ensure the involvement of Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) who actively engage with government initiatives and are dedicated to achieving financial stability. Additionally, the involvement of public institutions and universities plays a fundamental role by providing resources and academic support for the implementation and continuity of these programs. These institutions possess knowledge of the needs of patients with aphasia and can contribute to the stability and longevity of ICAPs. Ongoing training and education of the professionals involved, and the adoption of evidence-based practices are essential in delivering high-quality treatments to patients with aphasia. Efforts are also needed to ensure the quality and effectiveness of the services provided.

In summary, various factors require attention to implement ICAPs in Brazil including committed leadership, financial stability, and involvement of public institutions and universities. Addressing these issues may make it possible to promote the continuity and effectiveness of these programs, ensuring that individuals with aphasia have access to appropriate and quality treatments.

Conclusions and Future Research

Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs (ICAPs) have emerged as a promising treatment approach, addressing multiple domains of disability, role, participation, environment, and personal factors. However, the implementation and sustainability of ICAPs face challenges worldwide, including in Brazil. There is a need to focus on raising public and professional awareness of aphasia, developing strategies, and establishing public policies to improve access to ICAPs. It is crucial to educate and train speech-language pathologists in effective aphasia interventions, promote aphasia awareness at the national level, and address socioeconomic barriers that hinder access to therapy, such as transportation. Based on the Aphasia House program, it is feasible to implement more ICAPs in Brazil. For this, health professionals, especially speech therapists, must seek financial support from the government to introduce this therapy model. Demonstrating the overall benefits of ICAPs in the recovery of individuals with aphasia, including improved language skills, functional communication, and listening comprehension, will be crucial to starting the program. In conclusion, implementing ICAPs in Brazil requires strong leadership, financial stability, and collaboration with public institutions and universities. By addressing these challenges and promoting the sustainability of ICAPs, individuals with aphasia will have better access to high-quality care, improving their communication skills and overall well-being.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.4 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2314330

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abreu, E. A. d., Balinha, D. M., Costa, M. L. G., & Brandão, L.(2021). Afasia e inclusão social: panorama brasileiro na Fonoaudiologia. Distúrbios da comunicação. São Paulo. 33, 2 (jun. 2021), p. 349–356.

- Babbitt, E. M., Worrall, L., & Cherney, L. R. (2015). Structure, Processes, and Retrospective Outcomes From an Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program. American Journal of Speech-language Pathology?, 24(4), S854–863. doi:10.1044/2015_ajslp-14-0164

- Baker, C., Worrall, L., Rose, M., Hudson, K., Ryan, B., & O’Byrne, L. (2018). A systematic review of rehabilitation interventions to prevent and treat depression in post-stroke aphasia. Disability and Rehabilitation?, 40(16), 1870–1892. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1315181

- Blom Johansson, M., Carlsson, M., Östberg, P., & Sonnander, K. (2022). Self-reported changes in everyday life and health of significant others of people with aphasia: a quantitative approach. Aphasiology, 36(1), 76–94. doi:10.1080/02687038.2020.1852166

- Cabral, N. L., Nagel, V., Conforto, A. B., Amaral, C. H., Venancio, V. G., Safanelli, J., and Zetola, V. H. F. (2018). Five-year survival, disability, and recurrence after first-ever stroke in a middle-income country: A population-based study in Joinvile, Brazil. International Journal of Stroke?, 13(7), 725–733. doi:10.1177/1747493018763906

- Cacho, R. O., Moro, C. H. C., Bazan, R., Guarda, S. N. F. D., Pinto, E. B., Andrade, S. M. M. D. S., Valler, L. A., Ribeiro, K. J., Almeida, K. J., Ribeiro, T. S., de Moura Jucá, R. V. B., Minelli, C., Piemonte, M. A. P., Paschoa, E. H. A., Pedatella, M. T. A., Pontes-Neto, O. M., Fontana, A. P., & Pagnussat, A. S., Conforto, A. B., & Area Study Group,(2022). Access to rehabilitation after stroke in Brazil (AReA study): Multicenter study protocol?. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria, 80(10). doi:10.1055/s-0042-1758558.

- Carleto, N. G., Godoy, M., & Caldana, M. (2016). Programa de orientação fonoaudiológica e psicológica para familiares de pacientes lesionados cerebrais. Distúrbios da Comunicação, 28(2).

- Cruice, M., Worrall, L., & Hickson, L. (2010). Health-related quality of life in people with aphasia: implications for fluency disorders quality of life research. Journal of Fluency Disorders?, 35(3), 173–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfludis.2010.05.008?.

- da Silva Michelini, C. R., & de Lourdes Caldana, M. (2005). Grupo de orientação fonoaudiológica aos familiares de lesionados cerebrais adultos. Revista Cefac, 7(2), 137–148.

- Dignam, J., Copland, D., McKinnon, E., Burfein, P., O’Brien, K., Farrell, A., & Rodriguez, A. D. (2015). Intensive versus distributed aphasia therapy: a nonrandomized, parallel-group, dosage-controlled study. Stroke, 46(8), 2206–2211.

- Engelter, S. T., Gostynski, M., Papa, S., Frei, M., Born, C., Ajdacic-Gross, V., …Lyrer, P. A. (2006). Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke, 37(6), 1379–1384. doi:01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c [pii]

- Godoy, M. R. B. (2020). Cuidando de quem cuida: elaboração de uma cartilha de orientações para os cuidadores familiares de pacientes pós-AVC. Universidade de SãoPaulo, Griffin-Musick,J. R., Off, C. A., Milman, L., Kincheloe, H., & Kozlowski, A.(2021). The impact of a university-based Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program (ICAP) on psychosocial well-being in stroke survivors with aphasia. Aphasiology, 35(10), 1363–1389.

- Guedes, A., Retorno do Brasil ao Mapa da Fome da ONU preocupa senadores e estudiosos. Agência Senado, 14 out. 2022. Disponível em: https://www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/infomaterias/2022/10/retorno-do-brasil-ao-mapa-da-fome-da-onu-preocupa-senadores-e-estudiosos

- Helm-Estabrooks, N., & Whiteside, J. (2012). Use of life interests and values (LIV) cards for self-determination of aphasia rehabilitation goals. Perspectives on Neurophysiology and Neurogenic Speech and Language Disorders, 22(1), 6–11.

- Hilari, K., Byng, S., Lamping, D. L., & Smith, S. C. (2003). Stroke and aphasia quality of life scale-39 (SAQOL-39) evaluation of acceptability, reliability, and validity. Stroke, 34(8), 1944–1950.

- Hilari, K., Needle, J. J., & Harrison, K. L. (2012). What are the important factors in health-related quality of life for people with aphasia? A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation?, 93(1 Suppl), S86–95 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.028?. Retrieved from

- Hoover, E. L., & Carney, A. (2014). Integrating the iPad into an intensive, comprehensive aphasia program. Seminars in Speech and Language?, 35(1), 25–37. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1362990

- Lima, R. R., Borges, R., Lima, H. D. N., Caldana, M. D. L., & Freitas, M. I. D. Á.(2024). A survey on the speech therapy rehabilitation landscape for aphasia in Brazil. Aphasiology. doi:10.1080/02687038.2024.2314325.

- Lima, R. R., Rose, M., Lima, H. d. N., Cabral, N., Silveira, N. C., & Massi, G. A. (2020). Prevalence of aphasia after stroke in a hospital population in southern Brazil: a retrospective cohort study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation?, 27(3), 215–223. doi:10.1080/10749357.2019.1673593

- Lipp, M. E. N., & de Hoyos Guevara, A. J. (1994). Validação empírica do Inventário de Sintomas de Stress (ISS). Estudos de psicologia, 11(1–3), 43–49.

- Monteiro, E. A., Mazin, S. C., & Dantas, R. A. S. (2015). The informal caregiver burden assessment questionnaire: Validation for Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 68, 421–428.

- Morris, R., Eccles, A., Ryan, B., & Kneebone, I. I. (2017). Prevalence of anxiety in people with aphasia after stroke. Aphasiology, 31(12), 1410–1415. doi:10.1080/02687038.2017.1304633

- Nascimento, D. (2015). Consciência sobre a Afasia: Inquérito realizado no município de Florianópolis.

- Off, C. A., Leyhe, A. A., Baylor, C. R., Griffin-Musick, J., & Murray, K. (2022). Patient Perspectives of a University-Based Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program for Stroke Survivors with Aphasia. Aphasiology, 1–28.

- Palma,T.A.l.B.S(2014). Conhecimento sobre afasia da população portuguesa adulta. Barcarena: Universidade Atlântica.

- Ribeiro Lima, R., Rose, M. L., Lima, H. N., Guarinello, A. C., Santos, R. S., & Massi, G. A. (2021). Socio-demographic factors associated with quality of life after a multicomponent aphasia group therapy in people with sub-acute and chronic post-stroke aphasia. Aphasiology, 35(5), 642–657

- Rose, M. L., Cherney, L. R., & Worrall, L. E. (2013). Intensive comprehensive aphasia programs: an international survey of practice. Topics in stroke rehabilitation?, 20(5), 379–387. doi:10.1310/tsr2005-379

- Rose, M. L., Pierce, J. E., Scharp, V. L., Off, C. A., Babbitt, E. M., Griffin-Musick, J. R., & Cherney, L. R. (2022). Developments in the application of Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs: an international survey of practice. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(20), 5863–5877.

- Savóia, M. G., Santana, P. R., & Mejias, N. P. (1996). Adaptação do inventário de Estratégias de Coping1 de Folkman e Lazarus para o português. Psicologia usp, 7(1–2), 183–201.

- Simmons-Mackie, N., & Cherney, L. (2018). Aphasia in North America: Highlights of a White Paper. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 99, e117. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.07.417

- Tamietti, G., & Tamietti, G. (2024, January22). Déficit Habitacional no Brasil – NOVO | Fundação João Pinheiro - FJP| Portal Da Fundação João Pinheiro. https://fjp.mg.gov.br/deficit-habitacional-no-brasil/

- Whiteside, J. D., & Pak Hin Kong, A. (2014). Design Principles and Outcomes of” Aphasia House” an University Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Program (ICAP). aphasiology.pitt.edu. http://aphasiology.pitt.edu/2577/

- Wiltsey Stirman, S., Baumann, A. A., & Miller, C. J. (2019). The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 14, 1–10.

- Yap, P. (2010). Validity and reliability of the Zarit Burden Interview in assessing caregiving burden. Ann Acad Med Singapore, 39 758–763.