ABSTRACT

This study describes the development and validation of Proso-Quest, a parental report of toddlers’ prosodic skills that aims to assess early prosodic development in European Portuguese. The development and validation of Proso-Quest proceeded in three phases. Phase 1 was undertaken (a) to establish the structure of the parental report and select the items considering previous work, (b) to collect input from experts on prosodic development, and (c) to revise the report after a pilot study. Phase 2 examined internal consistency, reliability, test-retest reliability, and correlations between Proso-Quest and a valid measure of vocabulary development. Finally, Phase 3 evaluated the discriminant validity of this report in a clinical sample that frequently presents prosodic impairments. The psychometric properties of Proso-Quest indicated an excellent internal consistency, high test-retest reliability, significant correlations with a valid measure of vocabulary development, and sensitivity to identify prosodic delays. This parental report showed evidence of reliability and validity in describing early prosodic development and impairment, and it may be a useful tool in research and educational assessments, as well as in clinical-based assessments.

Introduction

Prosody can be defined as the ‘level of linguistic representation at which the acoustic-phonetic properties of an utterance vary independently of its lexical items’ (Wagner & Watson, Citation2010, p. 905). In other words, it covers the ‘aspects of speech that are not directly related to the articulation of the vowels and consonants in linguistic expressions’ (Gussenhoven, Citation2015, p. 714). As prosodic impairments can dramatically influence daily conversations, social interactions (Paul et al., Citation2005; Shriberg et al., Citation2001), and typical language development (e.g. Cutler & Swinney, Citation1987; Gervain et al., Citation2020; Paul et al., Citation2020; Peppé, Citation2018), it is crucial to assess prosodic skills early on development. The main purpose of this study is to present the development and validation of a parental report of toddlers’ prosodic skills, the Proso-Quest, that assesses early prosodic development in European Portuguese.

The development of prosodic skills is characterised by an age-related sequence that begins at birth (or even prior to birth) and goes beyond the first years of life. From birth, typically developing children use prosody as a means to bootstrap the acquisition of the grammar and the lexicon during language learning (e.g. Christophe et al., Citation1997; Gervain, Citation2018; Höhle, Citation2009). For instance, 5-month-old infants are already able to discriminate the native intonation patterns of statements and questions, which are basic sentence types crucial for communication and social interaction (Frota et al., Citation2014). Around the same age, infants have been shown to distinguish between stress patterns and recognise the typical stress pattern of the native language (Bhatara et al., Citation2018; Frota, Butler, et al., Citation2020), an ability that has been linked to the development of other abilities, such as the segmentation of the speech signal into words and phrases (Christophe et al., Citation2003; Jusczyk et al., Citation1999; Polka & Sundara, Citation2012, among others). The prosodic cues for phrase boundaries have also been shown to guide word segmentation, as infants extract word forms from continuous speech when placed next to a major prosodic boundary before they are able to segment them at other positions within the utterance (as early as by 4 months of age in Butler & Frota, Citation2018, and by 6 months of age in Johnson et al., Citation2014). Around 16 months, the sensitivity to prosodic cues allows extracting information about the intentions of others (Sakkalou & Gattis, Citation2012). In production, children seem to use vocalisations and some particular prosodic patterns already at 12 months as a guide to action, for instance in danger or ambiguous situations (Vaish & Striano, Citation2004). Catalan, Spanish, and European Portuguese-learning toddlers have been reported to use intonation contours in an adult-like fashion from the onset of speech to express different pragmatic meanings (Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016; Prieto et al., Citation2012). For example, around 18 months of age, a single syllable or word might be uttered to express a statement, a command, a request, or a question depending on the intonation contour. Dutch-learning children have also been shown to early master important aspects of native intonation by 24 months of age (Chen & Fikkert, Citation2007; see Frota & Butler, Citation2018 for a review of work on the early development of intonation). The early production of multiword combinations tends to be characterised by successive single-word prosodic phrases first, followed by words integrated into coherent prosodic phrases (Behrens & Gut, Citation2005; Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016).

Failure to achieve the expected milestones in prosodic development may lead to prosodic impairments with impact on language development, communication, and social interaction (Paul et al., Citation2005, Citation2020; Peppé, Citation2018; Shriberg et al., Citation2001). Research has shown that prosodic impairments are frequent in a variety of clinical populations, such as in developmental language disorder (e.g. Paul et al., Citation2020; Wells & Peppé, Citation2003), autism spectrum disorders (e.g. Filipe et al., Citation2014; Green & Tobin, Citation2009), Down syndrome (e.g. Frota, Pejovic, et al., Citation2020; Heselwood et al., Citation1995; Stojanovik, Citation2011), Williams syndrome (e.g. Catterall et al., Citation2006; Stojanovik & Setter, Citation2009), developmental dyslexia (e.g. Goswami et al., Citation2010; Keshavarzi et al., Citation2022), epilepsy (e.g. Sanz-Martín et al., Citation2006), cerebral palsy (Paul et al., Citation2020), hearing loss and deafness (e.g. Parker & Rose, Citation1990; Paul et al., Citation2020), or motor speech disorders such as childhood apraxia of speech (ASHA, Citation2007). In addition, it has been suggested that the use of prosodic cues, for example in speech segmentation, might differ in infants and toddlers at risk for language impairment, such as in preterm children or in siblings of autistic children (Frota, Pejovic, et al., Citation2020)

To better understand typical language development and to identify prosodic atypicalities, tools for evaluating children’s prosodic skills are extremely important. There are several tests, profiles, and batteries available for evaluating children’s prosodic skills. Some of most well-known ones are described below:

The Prosody-Voice Screening Profile (PVSP) quantifies prosodic skills, as well as voice characteristics, through a spontaneous conversation (McSweeny & Shriberg, Citation2001; Shriberg et al., Citation1990). It is divided into seven areas, three of which assess prosody (phrasing, rate, and stress) and four evaluate voice (loudness, pitch, laryngeal quality, and resonance). This procedure has reference data for children between 3 to 19 years of age.

The Prosody Profile (PROP; Crystal, Citation1982) focuses on intonation, and it can be used to describe other prosodic categories, such as the rhythm of speech. It focuses on the linguistic use of pitch. A conversation sample is recorded and analysed: tone units are identified and categorised as constituting grammatical structures (clauses, phrases, and words), stereotypical utterances, imitative utterances, and indeterminate utterances. The type of tones used is annotated, as is the appropriateness of tonicity and pitch range.

The Voice Assessment Protocol for Children and Adults (VAP) evaluates vocal pitch, loudness, quality, breath features, and rate/rhythm (Pindzola, Citation1987). Tasks are guided step by step, and immediate interpretations of normality are facilitated by a grid-marking system. This is a procedure for individuals aged between 4 and 18 years.

The Frenchay Dysarthria Assessment (FDA) is a 10-item validated test in which eight items focus on the observation of oral structures and speech functions (Enderby & Palmer, Citation2008). The FDA has eight sections that include reflexes (cough, swallow, and dribble/drool), respiration (at rest and in speech), lips (at rest, spread, seal, alternate, and in speech), palate (fluids, maintenance, and in speech), laryngeal (time, pitch, volume, and in speech), tongue (at rest, protrusion, elevation, lateral, alternate, and in speech), intelligibility (words, sentences, and conversation), and influencing factors (including hearing, sight, teeth, language, mood, posture, rate, and sensation). This rating form indicates strengths and weaknesses and allows for a comparison of performance across all items. The assessment evaluates the prosody at the word, sentence, and discourse levels from the age of 12 to adulthood. Normative data are reported for adults without dysarthria as well as patients with specific dysarthria.

The Profiling Elements of Prosody in Speech-Communication (PEPS-C; Peppé & McCann, Citation2003) is specifically designed for evaluating receptive and expressive prosodic abilities, and the tasks are at two levels: form and function. The form level assesses auditory discrimination and the voice skills required to perform the tasks, whereas the function level evaluates receptive and expressive prosodic skills in four domains: (a) turn-end – questions versus statements; (b) affect – liking versus disliking; (c) chunking – prosodic phrase boundaries; and (d) focus – accent placement on a particular word. This test is suitable for adults and children above 4 years of age with typical or atypical development and is useful for the comparison of prosodic development in different languages (Peppé et al., Citation2009), including European Portuguese (Filipe et al., Citation2017).

Despite the importance of the tools described above, the instruments available for assessing prosodic skills show several limitations, such as the lack of strong psychometric properties and ecological validity. Moreover, some tools are difficult to apply, require specific linguistic knowledge, and demand a considerable amount of time for administration. A common limitation of the tools available is that none assess the expression and comprehension of prosody before the age of 4 years. Indeed, to our knowledge, there are no instruments to evaluate expressive and comprehensive prosody on toddlers.

A classic method used to measure developmental skills is parental reports (e.g. Fenson et al., Citation1993, Citation2007; Wetherby & Prizant, Citation2003). These tend to be a cost-efficient and valid means for the assessment of language skills, by using longitudinal information collected from parents or children’s caregivers, who have extensive experience with their children under a wide variety of contexts. Moreover, parental reports may provide an inexpensive alternative to standardised assessments and are more likely to prove representative measures of the individual child’s skills. Thus, parental reports can be utilised as a useful tool in research, educational and clinical settings, namely in clinical-based assessments.

To the best of our knowledge, a parental report to assess early prosodic development has not yet been developed. To address the present gap in the assessment of early prosodic skills and contribute to the knowledge about early prosodic development, we developed a new tool to measure prosodic development and prosodic impairments. The main aim of this study is to describe the development and validation of Proso-Quest, a parental report designed to elicit useful and reliable information from caregivers about their toddler’s prosodic abilities, that can be used in research and clinical settings, as in speech-language pathology service. The 18-item scale was designed for toddlers, given the age range of the early acquisition of prosodic skills and the goal to measure early development and early identification of developmental delays.

The development and validation of the Proso-Quest proceeded in three phases. Phase 1 was undertaken to ensure that the tool had a clear structure with clear items, which were easy to understand and suitable to assess prosodic skills early on development. In Phase 2, we assessed reliability and validity in a typically developing sample measured by internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and correlations between this measure and a measure of expressive vocabulary development. In Phase 3, we evaluated the discriminant validity of the tool in a clinical sample (toddlers with Down syndrome) to support the ability of Proso-Quest to identify prosodic impairments. It was predicted that scores on the Proso-Quest would be lower in the clinical sample than in the typically developing peers.

Phase 1

Purpose

Work on the Proso-Quest started in 2012 (Frota et al., Citation2012). Phase 1 was the first step undertaken (a) to establish the structure of the parental report and select the items considering previous work, (b) to collect input from experts on prosodic development, and (c) to revise the report after a pilot study. Information was collected about the ease of administration and length of time required to complete the parental report.

Method

The prosodic skills to be assessed were operationally defined as the comprehension and production of communicative functions of intonation (i.e. statement, question, command, request, and call), of the prosodic structure of utterances (i.e. single-word phrases, multiword prosodic phrases, sensitivity to major prosodic boundaries), and of the highlighting function of prosody (i.e. signalling the most important information to be conveyed through prominence features, as in the case of contrastive focus). This choice is in line with the three main linguistic functions of prosody long defined in the literature (e.g. Halliday, Citation1967): the distinction among sentence types (choice of nuclear contour); demarcation, i.e. the chunking of the speech stream into prosodic phrases; and highlighting, i.e. the placement of prominence. Furthermore, work on infants’ and toddlers’ perception of prosody has suggested a developmental path characterised by early abilities to discriminate the intonation contours that distinguish the native statement and question sentence types (Frota et al., Citation2014, for European Portuguese), and to use prosodic chunking to extract word forms from continuous speech first when they are placed next to a major prosodic boundary and later at other positions within the utterance (Butler & Frota, Citation2018; Johnson et al., Citation2014; Seidl & Johnson, Citation2006; Shukla et al., Citation2011, for European Portuguese). By the end of the first year of life, infants seem to be able to discriminate the prosodic contrast that conveys the distinction between all-new information (broad focus) and the highlighting of a particular word (narrow/contrastive focus) in European Portuguese (Butler et al., Citation2016). Work on the early production of prosody has shown the ability to produce a variety of nuclear contours to convey different sentence type meanings, mostly using single-word prosodic phrases (e.g. Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016; Prieto et al., Citation2012, for European Portuguese). Successive single-word phrases follow, with words integrated into coherent prosodic phrases appearing later in development (Behrens & Gut, Citation2005; Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016). The ability to produce the highlighting function of prosody, namely contrastive focus, has been shown to vary across languages depending on the language specific means used for focus marking (e.g. Chen, Citation2018), with European Portuguese learning-toddlers showing near adult-like production before 24 months of age in spontaneous speech data (Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016). European Portuguese has been reported as a language where contrastive focus is mostly conveyed by prosody alone (Fernandes, Citation2007; Frota, Citation2000, Citation2014). Importantly, the use of pitch prominence to mark focused words in child-directed speech is common to other languages (e.g. Fernald & Mazzie, Citation1991, for English). Moreover, speech directed to infants has been shown to make a critical use of prosodic features that may enhance prosodic learning (Räsänen et al., Citation2018).

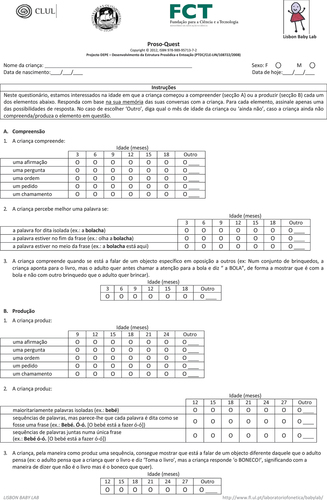

A total of 18 items were developed to assess these prosodic skills, 9 for the comprehension of prosody and 9 for the production of prosody, each with a 7-alternative forced-choice question that corresponds to different age options, with the last option being ‘other/not yet (understood or produced)’. Ten items measure the distinction among sentence types in comprehension and production, six measure the role of prosodic structure in comprehension and production, and another two measure the ability to understand and produce contrastive focus. An example of an item is provided in (see Appendix 1 for an English translation of the parental report, together with the Portuguese original version). The items were formulated to be simple to read and easy to understand. Crucially, prosody is not mentioned in any of the items, as parents are not expected to understand prosodic concepts (such as nuclear contour, prosodic boundary, or prominence). Instead, prosodic skills are assessed through the ability to use the main functions of prosody as instantiated in the items included in the parental report.

Table 1. Item to assess the comprehension ability to distinguish among sentence types.

This report should be completed retrospectively (e.g. at the age of 18 months of the child, parents would be asked to recall the age of acquisition of the different prosodic abilities). The validity of retrospective data collection has been supported by work showing that estimates from memory are as valid and reliable as the data collected with children. For instance, research compared two ways of collecting the age of acquisition (AoA) for a set of words: (a) adults were asked to estimate the age at which they possibly learned a given word and (b) children’s performance was analysed in naming tasks. Results showed that the norms provided by the two methods are highly correlated (Cameirão & Vicente, Citation2010; Ghyselinck et al., Citation2000; Morrison et al., Citation1997; Pind et al., Citation2000).

To ensure the face validity of the items selected, they were evaluated by four linguists with an expertise on prosody who worked at the Lisbon Baby Lab and had experience with infants, toddlers, and parents. Each linguist provided an oral statement regarding the relevance of each item.

Proso-Quest was subsequently administered to 50 children (27 girls; age range 13 months and 28 days to 28 months and 29 days; M = 22 months and 29 days, SD = 3.73) to determine how long it would take to complete the questionnaire and whether the items were easy to understand. Because the focus was on time constraints and clarity of wording, children’s developmental status was not ascertained. All participants were European Portuguese-learning toddlers from European Portuguese monolingual homes, with no visual or hearing problems. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of participants, and the parent/caregiver had the opportunity to ask for further information about the study.

Results

Parents required an average of 10 minutes to complete the report, and the pilot study resulted in improvements in the instructions given, in question formulation, and in form layout. All items were considered as relevant by the experts. Examples were added or amended for clarification in the items that measure the role of prosodic structure and the ability to understand/produce contrastive focus to reflect parents’ questions and suggestions. The instructions given to fill in the form were also amended for clarity. Finally, the layout of the form was improved to better visually define and separate each item and respective response lines. All changes were verified with the experts and a subset of 10 parents/caregivers to confirm that they improved the form. No other revisions were required.

Phase 2

Purpose

Phase 2 assessed the reliability and validity of the scale with typically developing toddlers. Internal consistency of the items within the comprehension and production categories was calculated (this measure depends on the correlation between the items, the number of items, and the variance of the total score). In addition, test-retest reliability was measured. A group of caregivers completed the report twice to assess the consistency between test and retest. For validity, we analysed the correlation between the mean scores of this new measure and the mean scores of a valid parental report to assess lexical development. We expected good internal consistency, moderate to high positive correlations for test-retest, and validity correlations between the Proso-Quest and the measure of lexical development.

Method

Participants

According to the National Statistics Institute (INE, Citation2016), there were 249,637 children between the age range chosen for this study in continental Portugal and the islands of Azores and Madeira in 2016. Considering this target population, we computed our sample size using the formula provided by Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) with the following parameters: margin of error of 5%, and the confidence level of 95%. We obtained a sample size of 384.

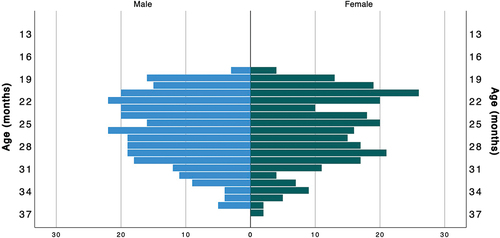

A total of 597 children recruited through nursery schools and the Lisbon Baby Lab database participated in the study, and 67 participants were excluded from analysis because of missing data (in the report itself or about the child, e.g. date of birth). The final sample included 530 children (256 girls, 274 boys; range 18–36 months; Mean age = 25 months and 25 days, SD = 4.54), from different regions of Portugal (28.8% from North, 26.2% from Lisbon, 21.7% from the Center, 9.3% from Alentejo, 8.3% from the Algarve, and 5.6% from the Islands). The age range for administration of the questionnaire was between 18 and 36 months, given that previous studies indicated that some of the prosodic skills assessed were not expected to be developed before 18 months of age. The age of the child at the moment the caregiver filled out the report had no impact in the excluded forms. The distribution of participants by age and sex is presented in .

To compute consistency between test and retest, the replication sample consisted of 21 children (8 girls, 13 boys; Mean age at time of test = 19 months and 18 days, SD = 5.18; Mean age at time of retest = 20 months and 29 days, SD = 5.63). As there is no established criterion to determine the test-retest sample size, no formal sample size was calculated for the follow-up questionnaire.

To measure the correlation between Proso-Quest and a measure of lexical development, a subsample of the initial sample was assessed with a parental report measure of vocabulary development (n = 460 children; 223 girls, 237 boys; range: 18–30 months; Mean age = 25 months and 24 days, SD = 4.47).

All participants were European Portuguese-learning toddlers from European Portuguese monolingual homes, with no visual or hearing problems. Forms were not collected for children reported to have medical conditions, based on the information provided by the nursery school teacher or the caregiver. Parental employment and educational status of the caregivers showed that the majority of participating families were in the high and medium-qualified categories (42.5% and 38.3%, respectively), 6.4% were in the low-qualified category, and 12.8% belong to the unemployed group.Footnote1 These numbers are in line with other parental report studies that show a skewing towards higher/medium educational levels of the caregivers (e.g. Fenson et al., Citation2000, Citation2007; Frota, Butler, et al., Citation2016; Jackson-Maldonado et al., Citation2013; Kristoffersen et al., Citation2013; Simonsen et al., Citation2014).

Material

All the participants were evaluated with the Proso-Quest parental report described in Phase 1. Proso-Quest was scored according to the age (in months) when the respective prosodic skill emerged. A subsample was also assessed with a parental report that measures vocabulary development, the toddler form of the European Portuguese MacArthur – Bates Communicative Development Inventories short forms (EP-CDI SFs; Frota, Butler, et al., Citation2016). The EP-CDI SF toddler form contains a 100-word vocabulary production checklist and a question about word combinations, and takes only a few minutes to complete. Higher scores on the EP-CDI SFs correspond to a better lexical development.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained by the ethics committees ‘Comissão de Ética para a Saúde do Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte’ (Ref.ª DIRCLN-16JUL2014-208) and ‘Comissão de Ética para a Saúde da Administração Regional de Saúde de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo’ (Proc.015/CES/INV/2014) and the recruitment of participants followed the ethical principles and recommendations of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights and the Declaration of Helsinki (developed by the World Medical Association). Informed consent was obtained from the caregivers of participants, which had the opportunity to ask for further information about the study.

The time points at which participants completed the Proso-Quest are referred to as Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2).

Results

Scores were statistically analysed to provide Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for comprehension and production mean scores at T1. This analysis was replicated in a subsample of 21 caregivers at T2, and test-retest reliability was computed. The validity of the measure was estimated by correlating the mean scores of parental responses in Proso-Quest with the mean vocabulary scores of the EP-CDI SFs. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.

The internal consistency measured with Cronbach’s alpha at T1 was .92 for comprehension mean scores and .91 for production mean scores. For the subsample that completed the Proso-Quest at T2, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were lower: comprehension mean score, α = .84; production mean score, α = .88.

The test-retest reliability measured by the Pearson product-moment correlations between the two administrations (T1 and T2) showed positive significant correlations for both comprehension (r = .77, p ≤ 0.001) and production mean scores (r = .85, p = 0.015).

Finally, the results of the (Pearson) correlation between the Proso-Quest and the EP-CDI toddler SF showed that the comprehension of prosody responses was negatively correlated with lexical development (r = −.31, p ≤ 0.001). No correlation was found for the production of prosody and vocabulary scores. In other words, the earlier acquisition of receptive prosodic skills promoted higher vocabulary scores.

Phase 3

Purpose

Phase 3 aimed to support the validity of the tool to identify prosodic impairments, using a clinical sample of children with Down syndrome (DS). DS results from partial or complete duplication of chromosome 21, and it is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability (Martin et al., Citation2009). As children with DS usually present delays in developmental milestones such as prosodic development (Heselwood et al., Citation1995; Stojanovik, Citation2011), we measured whether the Proso-Quest showed a high level of sensitivity for the identification of prosodic impairments in this population.

Method

Participants

Two groups participated in this Phase: the typically developing group of Phase 2 and a clinical group. The clinical group included 20 caregivers of children with DS (8 girls, 12 boys; 12–42 months; Mean age = 20.30; SD = 6.85) recruited through the database of the project Horizon 21 from the Lisbon Baby Lab. Ethical approval for the participation of the clinical group was obtained by the Ethical Committee for Research (CEI) of the School of Arts and Humanities of the University of Lisbon (1_CEI2018). All participants were European Portuguese-learning toddlers from European Portuguese monolingual homes.

Material and procedure

All the caregivers filled out the Proso-Quest parental report as described in Phase 2.

Results

Differences between the clinical group and the typically developing group were examined. Given the unequal sample size and unequal variance between the groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. For the comprehension items, the results showed significant differences between the scores of the DS children and the typically developing participants except for the understanding of commands and requests (cf. ). The differences for production items were not computed because most of the participants in the clinical group provided answers showing that these skills were not yet acquired by the time they completed the questionnaire.

Table 2. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), mean ranks, and U-values for children with Typical Development (TD) and children with Down Syndrome (DS) on the Proso-Quest.

General discussion

The Proso-Quest parental report was systematically developed and showed evidence of reliability and validity in describing early prosodic development and impairment. The first step of the development of the parental report (Phase 1) was devoted to establish its structure and select the items to be included (Frota et al., Citation2012), to collect input from experts on prosodic development, and to revise the report after a pilot study. The structure was designed to cover the main linguistic functions of prosody long defined in the literature (e.g. Halliday, Citation1967), comprising both comprehension and production. To establish face validity, items were selected considering data and findings from previous work on infants’ and toddlers’ perception and production of prosody. Furthermore, experts on prosodic development rated the items for relevance, provided feedback on the comprehensiveness of the report, and analysed whether it effectively captured the skills to be assessed. Moreover, a pilot study was conducted. As a result, the final version of the Proso-Quest had a clear structure with items that were easy to understand and suitable to assess prosodic skills early on development.

In Phase 2, reliability and validity were assessed in a sample of typically developing toddlers. As measured by Cronbach’s alpha, internal consistency was excellent for both comprehension and production mean scores. The replication with a second sample consisting of a group of caregivers that completed the report twice supported the stability of the alphas achieved. Moreover, administering the report twice yielded a high degree of short/long-term test-retest reliability. In addition, a low but significant negative correlation between the Proso-Quest comprehension measures and the CDI expressive vocabulary measure was found, suggesting that the earlier comprehension of prosodic skills promoted higher vocabulary scores, in line with proposals that the perception of prosody might facilitate language learning (e.g. Gervain et al., Citation2020; Höhle, Citation2009; Morgan & Demuth, Citation1996). However, our data did not support a link between the production of prosody and vocabulary scores, as no correlation was found between the Proso-Quest production scores and the CDI expressive vocabulary scores. In other words, the age of acquisition of prosody production skills seems not to be related to vocabulary production. A recent study examined early prosodic development measured with the Proso-Quest before 19 months of age as a predictor of the child’s performance on the CDI vocabulary scores two to seven months later (Sousa et al., Citation2022). Both for typical and atypical language acquisition, the authors found that the comprehension and production of prosody predicted later vocabulary outcomes. Although there are methodological differences between Sousa et al. (Citation2022) and the present study, given that our study correlated responses to the Proso-Quest and the CDI provided in the same moment in time, the partially similar findings obtained in the two studies further support the validity of the Proso-Quest tool.

The Proso-Quest was designed to be answered retrospectively, given that the validity of retrospective data collection has been supported in previous work on acquisition (albeit not specifically on prosody). This form of administration is less costly than successive data collection at multiple developmental points, and offers developmental information within a single questionnaire. A comparison with infants’ performance in perception and production tasks reported in previous studies suggests the validity of the retrospective procedure followed. Importantly, the results obtained for the TD sample were in line with performance-based measures available in the literature for the ability to perceive and produce sentence type distinctions, prosodic chunking, and prosodic focus in typically developing infants and toddlers.

Specifically, the comprehension of sentence type distinctions seems to be in place around 12 months of age, and the ability to produce the different sentence types is developed by 18 months of age. Infant perception experimental data have shown that the prosody of statements and questions in European Portuguese is discriminated by infants early in the first year of life (Frota et al., Citation2014). The discrimination ability is a prerequisite for the acquisition of the sentence types, namely their comprehension and production. Moreover, the analysis of longitudinal spontaneous speech data from two European Portuguese-learning toddlers has shown that they are able to produce a variety of sentence types by 17 months of age (Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016).

The Proso-Quest results for prosodic chunking suggest that it affects the ability to understand a word, which is achieved before 12 months if the word appears isolated, around 12 months if the word is placed next to a major prosodic boundary, and later if it appears in a phrase-internal position. Similarly, toddlers were found to produce first words in isolation (around 14 months), then successive single-word phrases and finally words bound together into the same prosodic phrase (by 19 months). These results are in accord with experimental data on early word segmentation that demonstrated that word forms at the utterance-edge are extracted from continuous speech early in the first year of life, whereas word segmentation in utterance-internal position is still developing by the end of the first year (Butler & Frota, Citation2018). The Proso-Quest findings are also in line with speech production data that show similar developmental steps, with prosodic integration of words into the same phrase between 17 and 21 months of age (Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016).

With respect to the highlighting function of prosody, the Proso-Quest results suggest that prosodic focus is understood around 13 months and produced around 18 months. Once again, this is in line with infant perception experimental data that showed discrimination between focalised words (contrastive focus) and neutral statements (broad focus) by the end of the first year of life (Butler et al., Citation2016). It also nicely matches early production data from two toddlers showing the successful production of prosodic focus (Frota, Cruz, et al., Citation2016).

In Phase 3, the discriminant validity of the tool was evaluated in a clinical sample of children with Down syndrome. As expected, scores on the Proso-Quest for the clinical sample were generally significantly lower than in the typically developing toddlers. This result confirmed previous studies showing that children with DS present with a delay in prosodic development (Heselwood et al., Citation1995; Stojanovik, Citation2011), and thus supported the validity of Proso-Quest to identify prosodic impairments. However, probably because of the small sample size, the large population variance which lead us to use a less powerful (non-parametric) test, and the broad age range of our sample from this clinical population, in the present study differences in two of the nine comprehension items measured by the Proso-Quest were not significant. Nevertheless, the present findings provide a first measure that might be useful for assessing prosodic development in toddlers with Down syndrome.

According to Diehl and Paul (Citation2009), tools for prosodic assessment should (a) have a typical comparison sample and strong psychometric properties; (b) be based on information concerning typical developmental paths of prosodic acquisition; (c) be sensitive to developmental change; (d) subcategorise several features of prosody; (e) use tasks that have ecological validity; and (f) be easy to administrate and have short duration for administration. Proso-Quest has all these crucial characteristics that allow it to become part of standard language assessment batteries. Given these characteristics, the values reported in the current study for typically developing toddlers constitute a reference to assess possible delays in prosody comprehension or production.

Proso-Quest was developed to profile the development of prosody early on language development. The report is simple and easy for caregivers to use, requiring a short administration time. For the speech-language pathologist interested in determining the language and communicative profile of toddlers, this report provides a time-efficient and cost-effective alternative to coding naturalistic interactions. Despite the positive feedback from the caregivers involved in all the phases of the study, it is important to consider that caregivers might not always have a clear understanding/judgement of speech features in a given communicative context. Thus, in-person administration should be prioritised to allow extra clarification and additional examples to describe the use of prosodic functions when needed.

The current study considered performance-based measures, both in perception and production, to develop the Proso-Quest and determine its items, and the results found that typically developing toddlers were in line with the findings from performance-based measures. Although this is a promising result, this study has five potential limitations. First, caregivers are not trained observers and may be biased reporters of their children’s abilities (Suen et al., Citation1995). As such, they may under- or over-estimate their child’s skills. Second, the current study did not systematically compare the Proso-Quest scores to performance-based measures of prosodic development for all the items. In fact, such measures are not yet available for all Proso-Quest items, as in the case of sentence types beyond statements and questions or direct measures for word comprehension (which go beyond the identification and extracting of word forms). Thus, future research should further examine the relationship between performance-based measures of prosodic development and the Proso-Quest scores, in order to strengthen the construct validity of the parental report. Third, sources of error might occur in retrospective studies due to confounding and recall bias, and future research should further compare the Proso-Quest results with other methods of data collection, and possibly also explore the questionnaire as a tool to collect data at many different developmental points. Fourth, given the small size of the test-retest replication sample, the good test-retest reliability should be interpreted with caution. Lastly, the present study just explored the administration of the questionnaire between 18 and 36 months of age. Therefore, additional research is needed to establish the lower and upper age limit of Proso-Quest application.

As the Proso-Quest items were developed taking into account the scientific literature related to prosodic development, and the application of the tool to atypical populations is still limited (Sousa et al., Citation2022), future research is crucial to explore the utility of this tool to the clinical field. Indeed, research with other clinical populations is required to further determine its ability to discriminate between typical and atypical populations with prosodic impairments. Moreover, future research should also address the value of this measure as a screening tool.

Although the assessment of prosodic skills is crucial to language and communicative development, no tool for assessing prosodic production and comprehension skills before the age of 4 years existed prior to the present study. Thus, the Proso-Quest provides researchers, educators, and clinicians with a useful tool for the evaluation of a young child’s prosodic abilities. The Proso-Quest scores for typically developing toddlers can be used as reference data for early prosodic development in European Portuguese. The clear and simple structure of the tool, targeting main linguistic functions of prosody, facilitates its adaptation to other languages. Thus, this parental report offers important and exciting new directions in the study of early prosodic development and in furthering our understanding of early prosodic deficits, with potential implications to early intervention strategies to support language learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The detailed data of this study are available from the corresponding author, SF, upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Professional categories followed the employment/educational status classification of the Portuguese Classification of Jobs (CNP, 2010, retrieved from http://cdp.portodigital.pt/profissoes/classificacao-nacional-das-profissoes-cnp), with 6 of the 9 CNP categories represented in the sample.

References

- ASHA. (2007). Technical report: Childhood apraxia of speech.

- Behrens, H., & Gut, U. (2005). The relationship between prosodic and syntactic organization in early multiword speech. Journal of Child Language, 32(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000904006592

- Bhatara, A., Boll-Avetisyan, N., Höhle, B., & Nazzi, T. (2018). Early sensitivity and acquisition of prosodic patterns at the lexical level. In P. Prieto & N. Esteves-Gibert (Eds.), The development of prosody in first language acquisition (pp. 37–57). https://doi.org/10.1075/tilar.23.03bha

- Butler, J., & Frota, S. (2018). Emerging word segmentation abilities in European Portuguese-learning infants: New evidence for the rhythmic unit and the edge factor. Journal of Child Language, 45(6), 1294–1308. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000918000181

- Butler, J., Vigário, M., & Frota, S. (2016). Infants’ perception of the intonation of broad and narrow focus. Language Learning and Development, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15475441.2015.1020376

- Cameirão, M. L., & Vicente, S. G. (2010). Age-of-acquisition norms for a set of 1,749 Portuguese words. Behavior Research Methods, 42(2), 474–480. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.2.474

- Catterall, C., Howard, S., Stojanovik, V., Szczerbinski, M., & Wells, B. (2006). Investigating prosodic ability in Williams syndrome. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20(7–8), 531–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699200500266380

- Chen, A. (2018). Get the focus right across languages: Acquisition of prosodic focus-marking in production. In P. Prieto & N. Esteve-Gibert (Eds.), Prosodic development in first language acquisition (pp. 295–314). https://doi.org/10.1075/tilar.23.15che

- Chen, A., & Fikkert, P. (2007). Intonation of early two-word utterances in Dutch. In J. Trouvain & W. J. Barry (Eds.), Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (pp. 315–320). Saarbrücken, Germany: Pirrot GmbH.

- Christophe, A., Gout, A., Peperkamp, S., & Morgan, J. (2003). Discovering words in the continuous speech stream: The role of prosody. Journal of Phonetics, 31(3–4), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0095-44700300040-8

- Christophe, A., Guasti, T., Nespor, M., Dupoux, E., & Ooyen, B. V. (1997). Reflections on phonological bootstrapping: Its role for lexical and syntactic acquisition. Language and Cognitive Processes, 12(5/6), 585–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/016909697386637

- Crystal, D. (1982). Profiling linguistic disability. Edward Arnold.

- Cutler, A., & Swinney, D. A. (1987). Prosody and the development of comprehension. Journal of Child Language, 14(1), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000900012782

- Diehl, J. J., & Paul, R. (2009). The assessment and treatment of prosodic disorders and neurological theories of prosody. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(4), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500902971887

- Enderby, P., & Palmer, R. (2008). Frenchay dysarthria assessment (2nd ed.). Pro-Ed.

- Fenson, L., Dale, P., Reznick, J. S., Thal, D., Bates, E., Hartung, J., Pethick, S., and Reilly, J. S. (1993). The MacArthur communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Singular Publishing Group.

- Fenson, L., Marchman, V. A., Thal, D. J., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., & Bates, E. (2007). MacArthur–Bates communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual (2nd ed.). Brookes Publishing.

- Fenson, L., Pethick, S., Renda, C., & Cox, J. L. (2000). Short form versions of the MacArthur communicative development inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics, 21(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400001053

- Fernald, A., & Mazzie, C. (1991). Prosody and focus in speech to infants and adults. Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.2.209

- Fernandes, F. (2007). Tonal association in neutral and subject-narrow-focus sentences in Brazilian Portuguese: A comparison with European Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 6(1), 91–115. https://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.146

- Filipe, M. G., Frota, S., Castro, S. L., & Vicente, S. G. (2014). Atypical prosody in Asperger syndrome: Perceptual and acoustic measurements. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1972–1981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2073-2

- Filipe, M. G., Peppé, S., Frota, S., & Vicente, S. G. (2017). Prosodic development in European Portuguese from childhood to adulthood. Applied Psycholinguistics, 38(5), 1045–1070. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716417000030

- Frota, S. (2000). Prosody and focus in European Portuguese: Phonological phrasing and intonation. Garland Publishing.

- Frota, S. (2014). The intonational phonology of European Portuguese. In S.-A. Jun (Ed.), Prosodic typology II. The phonology of intonation and phrasing (pp. 6–42). Oxford University PressOxford.

- Frota, S., & Butler, J. (2018). Early development of intonation. Trends in Language Acquisition Research, 23, 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1075/tilar.23.08fro

- Frota, S., Butler, J., Correia, S., Severino, C., Vicente, S., & Vigário, M. (2016). Infant communicative development assessed with the European Portuguese MacArthur–Bates communicative development inventories short forms. First Language, 36(5), 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723716648867

- Frota, S., Butler, J., Uysal, E., Severino, C., & Vigário, M. (2020). European Portuguese-learning infants look longer at iambic stress: New data on language specificity in early stress perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01890

- Frota, S., Butler, J., & Vigário, M. (2014). Infants’ perception of intonation: Is it a statement or a question? Infancy, 19(2), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12037

- Frota, S., Cruz, M., Matos, N., & Vigário, M. (2016). Early prosodic development. In M. Armstrong, N. C. Henriksen, & M. M. Vanrell (Eds.), Intonational grammar in Ibero-Romance: Approaches across linguistic subfields (pp. 295–324). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Frota, S., Cruz, M., Severino, C., Correia, S., Butler, J., & Vigário, M. (2012). Proso-Quest – Questionário Parental sobre o desenvolvimento da estrutura prosódica e entoação. Laboratório de Fonética, CLUL/FLUL.

- Frota, S., Pejovic, J., Severino, C., & Vigário, M. (2020). Looking for the edge: Emerging segmentation abilities in atypical development. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Speech Prosody 2020, 814–818. https://doi.org/10.21437/SpeechProsody.2020-166

- Gervain, J. (2018). Gateway to language: The perception of prosody at birth. In H. Bartos, M. den Dikken, Z. Bánréti, & T. Váradi (Eds.), Boundaries crossed, at the interfaces of morphosyntax, phonology, pragmatics and semantics (pp. 373–384). Springer International Publishing.

- Gervain, J., Christophe, A., & Mazuka, R. (2020). Prosodic bootstrapping. In C. Gussenhoven & A. Chen (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language prosody (pp. 562–573). Oxford University Press.

- Ghyselinck, M., De Moor, W., & Brysbaert, M. (2000). Age-of-acquisition ratings for 2816 Dutch four- and five-letter nouns. Psychologica Belgica, 40(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.958

- Goswami, U., Gerson, D., & Astruc, L. (2010). Amplitude envelope perception, phonology and prosodic sensitivity in children with developmental dyslexia. Reading & Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23(8), 995–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-009-9186-6

- Green, H., & Tobin, Y. (2009). Prosodic analysis is difficult … but worth it: A study in high functioning autism. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(4), 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500903003060

- Gussenhoven, C. (2015). Suprasegmentals. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 714–721). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.52024-8

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1967). Intonation and grammar in British English. The Hague. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111357447

- Heselwood, B., Bray, M., & Crookston, I. (1995). Juncture, rhythm and planning in the speech of an adult with Down’s syndrome. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 9(2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699209508985328

- Höhle, B. (2009). Bootstrapping mechanisms in first language acquisition. Linguistics, 47(2), 359–382. https://doi.org/10.1515/LING.2009.013

- INE. (2016). Portugal em Números. Portugal. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. https://www.ine.pt/ine_novidades/PN_2016//files/assets/common/downloads/publication.pdf

- Jackson-Maldonado, D., Marchman, V., & Fernald, L. (2013). Short-form versions of the Spanish MacArthur–Bates communicative development inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics, 34(4), 837–868. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716412000045

- Johnson, E. K., Seidl, A., Tyler, M. D., & Berwick, R. C. (2014). The edge factor in early word segmentation: Utterance-level prosody enables word form extraction by 6-month-olds. PloS One, 9(1), e83546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083546

- Jusczyk, P. W., Houston, D. M., & Newsome, M. (1999). The beginnings of word segmentation in English-learning infants. Cognitive Psychology, 39(3–4), 159–207. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0716

- Keshavarzi, M., DiLiberto, G. M., Gabrielczyk, F., Wilson, A., Macfarlane, A., & Goswami, U. (2022). Atypical speech production of multisyllabic words by children with developmental dyslexia. bioRxiv [Internet]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.24.505144

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Kristoffersen, K. E., Simonsen, H. G., Bleses, D., Wehberg, S., Jørgensen, R. N., Eiesland, E. A., & Henriksen, L. Y. (2013). The use of the Internet in collecting CDI data–an example from Norway. Journal of Child Language, 40(3), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000912000153

- Martin, G. E., Klusek, J., Estigarribia, B., & Roberts, J. E. (2009). Language characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome. Topics in Language Disorders, 29(2), 112–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/tld.0b013e3181a71fe1

- McSweeny, J., & Shriberg, L. D. (2001). Clinical research with the prosody-voice screening profile. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 15(7), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699200110078159

- Morgan, J. L., & Demuth, K. (1996). Signal to syntax: An overview. In J. L. Morgan & K. Demuth (Eds.), Signal to syntax: Bootstrapping from speech to grammar in early acquisition (pp. 1–22). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Morrison, C. M., Chappell, T. D., & Ellis, A. W. (1997). Age of acquisition norms for a large set of object names and their relation to adult estimates and other variables. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 50(3), 528–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/027249897392017

- Parker, A., & Rose, H. (1990). Deaf children’s phonological development. In A. G. Pamela (Ed.), Developmental speech disorders (pp. 83–108). Wiley.

- Paul, R., Augustyn, A., Klin, A., & Volkmark, F. R. (2005). Perception and production of prosody by speakers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Development Disorders, 35(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-004-1999-1

- Paul, R., Simmons, E., & Mahshie, J. (2020). Prosody in children with atypical development. In C. Gussenhoven & A. Chen (Eds.), Oxford handbook of language prosody (pp. 582–594). Oxford University Press.

- Peppé, S. (2018). Chapter 17: Prosodic development in atypical populations. In P. Prieto & N. Esteve-Gibert (Eds.), The development of prosody in first language acquisition (pp. 343–362). https://doi.org/10.1075/tilar.23.17pep

- Peppé, S., & McCann, J. (2003). Assessing intonation and prosody in children with atypical language development: The PEPS-C test and the revised version. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 17(4/5), 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269920031000079994

- Pind, J., Jónsdóttir, H., Tryggvadóttir, H. B., & Jónsson, F. (2000). Icelandic norms for the Snodgrass and Vanderwart (1980) pictures: Name and image agreement, familiarity, and age of acquisition. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00169

- Pindzola, R. (1987). A voice assessment protocol for children and adults manual. Pro-Ed.

- Polka, L., & Sundara, M. (2012). Word segmentation in monolingual infants acquiring Canadian English and Canadian French: Native language, cross‐dialect, and cross‐language comparisons. Infancy, 17(2), 198–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00075.x

- Prieto, P., Estrella, A., Thorson, J., & Vanrell, M. M. (2012). Is prosodic development correlated with grammatical development? Evidence from emerging intonation in Catalan and Spanish. Journal of Child Language, 39(2), 221–257. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030500091100002X

- Räsänen, O., Kakouros, S., & Soderstrom, M. (2018). Is infant-directed speech interesting because it is surprising? – Linking properties of IDS to statistical learning and attention at the prosodic level. Cognition, 178, 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.05.015

- Sakkalou, E., & Gattis, M. (2012). Infants infer intentions from prosody. Cognitive Development, 27(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2011.08.003

- Sanz-Martín, A., Guevara, M. A., Corsi-Cabrera, M., Ondarza-Rovira, R., & Ramos- Loyo, J. (2006). Efecto diferencial de la lobectomía temporal izquierda y derecha sobre el reconocimiento y la experiencia emocional en pacientes con epilepsia. Revista de Neurología, 42(07), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.4207.2004572

- Seidl, A., & Johnson, E. K. (2006). Infant word segmentation revisited: Edge alignment facilitates target extraction. Developmental Science, 9(6), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00534.x

- Shriberg, L. D., Kwiatkowski, J., & Rasmussen, C. (1990). The prosody-voice screening profile. Communication Skill Builders.

- Shriberg, L. D., Paul, R., McSweeny, J. L., Klin, A., Cohen, D. J., & Volkmar, F. R. (2001). Speech and prosody characteristics of adolescents and adults with high- functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 44(5), 1097–1115. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2001/087)

- Shukla, M., White, K. S., & Aslin, R. N. (2011). Prosody guides the rapid mapping of auditory word forms onto visual objects in 6-mo-old infants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(15), 6038–6043. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017617108

- Simonsen, H. G., Kristoffersen, K. E., Bleses, D., Wehberg, S., & Jørgensen, R. N. (2014). The Norwegian communicative development inventories: Reliability, main developmental trends and gender differences. First Language, 34(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723713510997

- Sousa, R., Silva, S., & Frota, S. (2022). Early prosodic development predicts lexical development in typical and atypical language acquisition. Proceedings Speech Prosody 2022, 387–391. https://doi.org/10.21437/SpeechProsody.2022-79

- Stojanovik, V. (2011). Prosodic deficits in children with Down syndrome. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 2(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2010.01.004

- Stojanovik, V., & Setter, J. (2009). Conditions in which prosodic impairments occur. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(4), 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500902943647

- Suen, H. K., Logan, C. R., Neisworth, J. T., & Bagnato, S. (1995). Parent-professional congruence: Is it necessary? Journal of Early Intervention, 19(3), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/105381519501900307

- Vaish, A., & Striano, T. (2004). Is visual reference necessary? Contributions of facial versus vocal cues in 12-month-olds’ social referencing behavior. Developmental Science, 7(3), 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00344.x

- Wagner, M., & Watson, D. G. (2010). Experimental and theoretical advances in prosody: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes, 25(7–9), 905–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690961003589492

- Wells, B., & Peppé, S. (2003). Intonation abilities of children with speech and language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 46(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2003/001)

- Wetherby, A. M., & Prizant, G. (2003). CSBS DP manual. First normed edition. Brookes Publishing.