?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Reading violent stories or watching a war documentary are examples in which people voluntarily engage with the suffering of others whom they do not know. Using a mixed-methods approach, we investigated why people make these decisions, while also mapping the characteristics of strangers’ suffering to gain a rich understanding. In Study 1 (N = 247), participants described situations of suffering and their reasons to engage with it. Using qualitative thematic analysis, we developed a typology of the stranger (who), the situation (what), the source (how), and the reason(s) for engaging with the situation (why). We categorised the motives into four overarching themes – epistemic, eudaimonic, social, and affective – reflecting diversity in the perceived functionality of engaging with a stranger’s suffering. Next, we tested the robustness of the identified motives in a quantitative study. In Study 2, participants (N = 250) recalled a situation in which they engaged with the suffering of a stranger and indicated their endorsement with a variety of possible motives. Largely mirroring Study 1, Study 2 participants engaged to acquire knowledge, for personal and social utility, and to feel positive and negative emotions. We discuss implications for understanding the exploration of human suffering as a motivated phenomenon.

In the current hyperconnected world, people commonly decide to view, read about, or listen to the suffering of other people. For example, people may read about a local hate crime, listen to a podcast about the victims of a gross injustice, seek out details about the personal conflict of a movie star, click on a video detailing a natural disaster on a different continent, pause on the street to watch a traffic accident, or visit a museum to learn about a terrible historical event. Critically, in all these examples the people who are suffering are not part of the viewer’s personal social network – they are strangers. Nevertheless, even in the absence of a direct relationship, viewers are willing to allocate resources – emotional, cognitive, and timewise – to inform themselves about their situation. Why do people decide to voluntarily engage with the suffering of strangers? And who are these strangers and what is their suffering about? The present paper addresses these fundamental questions, focusing on the expected value or benefits people may see in exploring other people’s hardships.

Research from a variety of scientific disciplines has shown that people deliberately expose themselves to triggering content through a wide variety of sources. For example, media studies have yielded consistent evidence that people seek out information about threatening events (Robertson et al., Citation2023), such as terrorist attacks, even though doing so may increase their fear of becoming a victim (Redmond et al., Citation2019). Similarly, aesthetics research has documented people’s interest in (Turner & Silvia, Citation2006) and enjoyment of art that portrays tragic or disturbing scenes (Menninghaus et al., Citation2017). Other examples come from fiction, such as the consumption of horror movies or videogames (Hofer et al., Citation2017; Scrivner et al., Citation2022), and sad novels or poetry (Koopman, Citation2015). Finally, research on curiosity has demonstrated that people are curious about images that show death or harm within a social context (e.g. images of fights, accidents, attacks, and war), and even prefer those to viewing neutral social alternatives (Oosterwijk, Citation2017).

These lines of research raise the question of why people seek out this type of content. We propose that the exploration of human suffering is motivated by perceived benefits (Niehoff & Oosterwijk, Citation2020). In this paper, we take a mixed-methods approach to examine this possibility and map the breadth of the phenomenon by creating a contextualised overview of people’s motives to engage with the suffering of a stranger.

Motives for engaging with the suffering of others

Although empirical research on the motives for voluntarily engaging with other people’s suffering is relatively scarce, work in the (largely separate) areas of curiosity, information seeking, media, empathy, and emotion regulation provides some initial insights. We provide a brief overview of these key literatures and theoretical approaches to situate our research within the broader field and inform our subsequent interpretation of the collected data.

First, work in the field of curiosity and information seeking suggests that engagement with others’ hardships allows people to acquire knowledge about the world. Generally, it is proposed that people seek out information because knowledge acquisition is rewarding (Murayama, Citation2022; Murayama et al., Citation2019). Information that is relevant or useful to the self may be sought out in particular (Abir et al., Citation2022; Sharot & Sunstein, Citation2020). Recent work has suggested that such informational motives are also important for engaging with negative content (for an overview see Niehoff & Oosterwijk, Citation2020). For example, when consuming horror, people report not only being motivated by sensation seeking, but also by goals like learning and personal development (Scrivner et al., Citation2022). Moreover, recent work has shown that decisions to engage with negative COVID-19 news are predicted by anticipated knowledge acquisition and the relevance of this information to one’s own situation (Niehoff et al., Citation2023). In short, people may engage with the suffering of others because their negative experiences hold information that is relevant for the successful navigation of social life (van Kleef, Citation2009).

Second, research in media psychology and aesthetics indicates that people seek out eudaimonic experiences when they engage with social media, books, films, and other cultural expressions that contain stories of hardship (e.g. Bartsch et al., Citation2014; Koopman, Citation2015; Oliver, Citation2022). In contrast to hedonia, which revolves around the experience of pleasure, eudaimonia refers to seeking out virtuous and meaningful experiences to pursue a life well lived (Gentzler et al., Citation2021). Art and entertainment portraying tragedy and suffering can promote in the observer a sense or reflection, insight, and cognitive challenge (Raney et al., Citation2022), and may create an opportunity to experience intense emotions from a safe distance (Menninghaus et al., Citation2017). In short, this literature highlights that observing and engaging with (artistic) expressions of suffering is a way of finding meaning and developing the self.

Third, work in the field of empathy suggests that empathy plays a role in guiding engagement with other people’s suffering. According to a recent perspective, context shapes motivations to up- or down-regulate empathy (Weisz & Cikara, Citation2021). On the one hand, people may up-regulate empathy in contexts where they want to affiliate with ingroup members, to capitalise on the positive emotional state of others, or to confirm social values (Zaki, Citation2014). On the other hand, people may down-regulate empathy because they want to protect themselves against emotionally taxing consequences, to avoid the (cognitive or monetary) costs of engaging with suffering, or to avoid being distracted by outgroup member’s emotions in cases of intergroup conflict (Zaki, Citation2014). For example, individuals with higher power tend to be less motivated to connect with other people’s suffering compared to individuals with lower power (Van Kleef et al., Citation2008). The idea that empathy can be costly and requires motivation is further supported by experimental evidence showing that people often avoid choosing tasks that demand an empathic response (Cameron et al., Citation2019). In short, in order to understand why people deliberately engage with the suffering of others, empathy is an important factor because it can be seen as an expected benefit (e.g. confirming social or personal values) or an expected cost (e.g. sharing distress).

Fourth, work from the field of emotion regulation indicates that people may be motivated to experience the emotional states that negative events evoke. Tamir (Citation2016) proposed that people use their emotional experiences instrumentally to be able to act (e.g. perform) in a particular way, gain knowledge, relate to others, and develop autonomy and competence. Importantly, people may maintain or up-regulate negative emotions to reach these goals. Empirical support for this perspective comes from studies showing that people sometimes prefer to experience unpleasant emotions (e.g. anger) for instrumental reasons (Tamir & Millgram, Citation2017). For example, when expecting to compete (vs. cooperate) with other people, participants chose anger- over happiness-inducing tasks to increase their chance of a successful outcome (Tamir & Ford, Citation2012). This perspective adds to explanations of people wanting to experience negative emotions for hedonic purposes (e.g. sensation or thrill seeking; see Andersen et al., Citation2020; Rozin et al., Citation2013).

This theoretical and empirical work provides preliminary insight into the motives that may lead people to engage with the suffering of others, including strangers. In the present study, we focus exclusively on why people engage with the suffering of strangers, which represents a particularly puzzling everyday phenomenon that remains poorly understood. In the case of a close other, engagement tends to be a given and the key question is what form the engagement takes (e.g. different strategies of interpersonal emotion regulation; Groth et al., Citation2023; Kalokerinos et al., Citation2017). In the case of a stranger, in contrast, engaging with the suffering could be costly (Cameron et al., Citation2019) and there are no interpersonal demands equivalent to those in close relationships, nor would there be lasting interpersonal consequences when dismissing the experience. Nevertheless, examples of people deliberately seeking out details about other people’s suffering in news, social media, books, movies, documentaries, museums, and on the street are manifold. In light of the ubiquity of this behaviour, it is important to understand people’s motivation for engaging with the suffering of strangers in particular.

The current research

The aim of this project is to enhance understanding of why people engage with the suffering of strangers by creating a theoretically plausible and contextualised taxonomy of motives. To accomplish this, we adopted a mixed-methods approach. In Study 1 we employed a qualitative design to (1) develop a typology of the situations of suffering people engaged with (by describing who was the suffering person, what was the situation, and how the participants accessed the content), and (2) gain insight into why they chose to engage with that situation. In Study 2 we aimed to (1) evaluate the robustness of the motives emerging from the qualitative study by using a quantitative approach and (2) explore possible differentiation in the endorsement of motives depending on the situation. This mixed-method approach lends itself well to addressing our central objective of assessing participants’ personal experiences and exploring novel and hitherto unidentified motives for engaging with the suffering of strangers in a rich and structured way (Kelle, Citation2006).

Following recommendations of the Qualitative Oriented Mixed-Methods approach (Poth & Shannon-Baker, Citation2022), we first conducted an initial qualitative step to build a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon at hand (Study 1), which was followed by a more structured quantitative phase (Study 2; for a similar approach, see Landmann et al., Citation2019). The initial qualitative phase allowed us to gain insight into the breadth of the phenomenon of interest, develop a preliminary understanding of relevant motives, and develop measures to tap into those motives (Scheel et al., Citation2021). By using this exploratory strategy, we aimed to obtain a rich and ecologically valid corpus of situations of suffering and motives to engage with these situations that can provide a basis for generating and testing specific hypotheses in future studies.

Study 1

Method

Participants

In total, 247 participants were recruited online through the platform Prolific. This sample size was substantially larger than the sample sizes commonly recommended (N ∼ 100) to capture the breadth of a topic and reach saturation (Braun et al., Citation2021). In the sample, 102 participants identified as women, 116 participants identified as men, and 29 participants reported identifying as non-binary or did not report their gender. The mean age was 30.5 (SD = 12.38, range from 19 to 74 years) and 49.4% of the participants were students. The sample included people from 36 different nationalities. English fluency was selected as the inclusion criterion. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Review Board prior to data collection (#2021-SP-13343). Participants received £4.00 for their participation, which took about 30 min. The study was run on 20 April 2021.

Procedure

Participants were asked to recall and share personal examples of situations in which they engaged with another person’s suffering and explain the reasons that guided this decision. Voluntary engagement with other’s suffering was defined as a situation in which people “deliberately choose to inform themselves about the suffering of others, for instance by reading about it, watching videos, listening to podcasts, talking about it with others, or in any other way.” Given our interest in engagement with the suffering of strangers, participants were further instructed that

we are particularly interested in situations where people engage with the suffering of someone, they do not know personally, whether face-to-face or online, involving a complete stranger, a real (famous) person currently alive, a historical figure, or a fictional character (e.g. in a book).

After these general instructions, participants were asked to share as much detail as possible about the situation of suffering (i.e. what was the event about, who was the stranger, how did the participant access the information). Participants could share up to 5 different situations in which they recalled engaging with distant others’ suffering. Then, participants were asked to describe the reason(s) for engaging with each of the shared situations. The question specifically asked participants to reflect on the expected value, function, or outcome of their voluntary engagement with the stranger’s suffering. Full details of the instructions are reported in the Supplementary Material and the codebook is available at the Open Science Framework. The raw qualitative data will be available upon reasonable request for privacy reasons.

Analysis

Data were analysed manually with semantic thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) using Atlas.ti software. This analysis aims to extract meaningful and recurrent patterns from participants’ responses and structure them hierarchically into codes, themes, and overarching themes. Codes are the unit closest to the raw data, followed by themes that capture groupings of several codes, and then (where applicable) overarching themes that group several themes.

The coding process followed existing guidelines for inductive coding. These do not state a predefined number of codes; rather, the aim is to generate a manageable and interpretable set of codes while doing justice to the complexity and richness of the data (Linneberg & Korsgaard, Citation2019). We followed a step-by-step procedure, beginning with an initial familiarisation of the data. In this step, responses that were not aligned with the study goal (e.g. situations in which family members, partners, friends, or participants themselves were suffering) were excluded from the dataset. After this initial cleaning, recurring patterns and salient responses were labelled through codes. For example, after reading several of the participants’ responses, we realised that a recurrent pattern involved situations of people incidentally and unintentionally hurting themselves (e.g. falls, cuts, or being hit by a car). Therefore, we developed the label “Accident” and tagged all the data entries that described accidents with this code.

Importantly, participants’ responses could include one or multiple codes. For example, participants commonly described multiple goals or reasons for their engagement (e.g.

Curiosity, motivation to not allow that to happen to my kids in the future, any way I could prevent it that maybe they overlooked, I also wanted to get an insight into how the family would be feeling – potentially make myself feel better about my life” Case 38).

Results

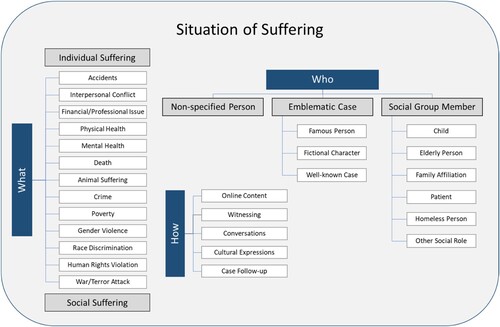

Participants shared in total 459 instances of suffering (M = 1.87 situations of suffering described per participant). Ninety-three responses were excluded from the analysis, because participants did not follow instructions. These exclusions concerned instances where the participants described the suffering of a close other (e.g. partner, family member) or themselves. In total, 366 instances were analysed. See Table SM1 in the Supplementary Material for examples of responses that illustrate different themes. and present a visual representation of all the themes and overarching themes emerging from the qualitative coding.

Figure 1. Characteristics of the reported situations of suffering, the strangers involved, and the means of accessing the information (Study 1).

Situations of suffering

Who were the suffering strangers?

The codes characterising the person suffering resulted in 10 themes, grouped into 3 overarching themes: non-specified person, emblematic case, and social group member.

The first overarching theme was non-specified person, which describes instances where the participant did not include any detail that characterised the person suffering. Participants referred to the suffering person as someone, a person, or a stranger.

The second overarching theme was named emblematic case and included instances in which the suffering individuals were identified with their names. This contained three different themes: famous people, well-known cases, and fictional characters. First, the theme famous people included politicians, entertainment characters, elite athletes, and other celebrities. For example, Case 53 describes: “Another formula one driver, Michael Schumacher fell into a coma after an unfortunate fall on the slope. It was a very shocking. experience for me, even though he is a stranger to me”. Second, well-known cases referred to people who have been locally or internationally recognised because of their suffering (e.g. George Floyd). To illustrate this theme, Case 56 stated:

When Natasha Kampusch got kidnapped, we were told to be careful when we go outside. I was very little back then, but I heard a lot about it and when the movie about her story and a few documentations came out I watched it. She suffered a lot and its crazy that it happened.

The third overarching theme was named social group member. This contained instances in which the person suffering was characterised by an aspect of their social identity or their membership of a certain social group. This included themes where certain details of the person suffering were shared, such as their age (e.g. children or elderly people) or their interpersonal affiliation (e.g. widow(er), parent, wife, husband). Note that “family affiliation” is a code used to specify how an instance placed emphasis on the interpersonal affiliation of the stranger (e.g. a grieving parent); in all cases, the suffering person was a stranger to the participant. This theme also included historically marginalised community members, such as disabled people/health patients, people of colour, and homeless people. Notably, some responses explicitly described people in situations of vulnerability, such as victims of personal or structural power abuse. For example, Case 120 stating “A woman being emotionally controlled by her husband”.

What were the situations of suffering about?

The coding process resulted in 13 themes characterising different situations of suffering. The most frequent theme referred to situations of suffering that portrayed death, which included violent death, natural death (e.g. long-term illnesses), suicide, accidental death, and unexpected death (e.g. still birth).

Among the other identified themes, participants described situations involving physical health problems, including disabilities and chronic disease; poverty, including famine or homelessness; interpersonal conflict, involving romantic relationships, friendships, or family issues; accidents, varying from minor events to accidents with life-lasting consequences; mental health issues, including drug addictions, depression, and anxiety; financial and professional issues, including career failures and unemployment; human rights violations, including political imprisonment and cases of state violence; gender violence, including aggression towards women, non cis-gender, and non-heterosexual people; crime, including mainly violent incidents; race discrimination towards non-white people; war and terror attacks, both recent and historical; and animal suffering, including the death of pets and cases of animal cruelty.

Based on our observation that participants emphasised systemic and less-systemic sources of suffering, and consistent with similar concepts in social psychology (e.g. collective victimhood; Vollhardt, Citation2020), sociology (Bourdieu et al., Citation1999), and anthropology (Wilkinson & Kleinman, Citation2016), we placed these themes on a continuum with individual suffering on one end, and social suffering on the other end (see ). Individual suffering reflected situations that primarily affected the target individual’s suffering and/or the suffering of their loved ones. Case 159 wrote, “I saw that a small girl fall on the playground and her knee was bleeding. I tried to talk to her and comfort her before her mum came”. Social suffering reflected themes regarding systematic violence, which implied the political, economic, national, ethnic, cultural, or other identitarian aspects of the individual(s) involved (Renault, Citation2010). For example, Case 188 wrote:

George Floyd was murdered by police who knelt on his neck until he stopped breathing. This sparked a lot of conversations about systemic racism, and I did a lot of research on his life and the circumstances that led up to his death. I did this by reading, watching the news, and accessing educational resources on social media.

How did participants access the suffering?

The codes characterising the sources of information participants accessed were grouped into 5 themes, of which 4 referred to a single source and the last one to multiple sources.

First, participants most frequently mentioned accessing suffering through online content. This theme mainly described online news (i.e. audiovisual or written news media) and social media platforms (i.e. Twitter, Facebook or Reddit). For instance, Case 21 described: “I saw a post on Instagram about a 10-year-old boy suffering from cancer and who needed a lot of money”. Second, participants referred to witnessing the event in person (“Seeing people who have no home”, Case 73). This theme included street interactions, where the participant actively got involved (e.g. by helping) or observed the situation. Third, participants mentioned conversations with others (“when I get told by the police of recent stabbings in my neighborhood”, Case 60). Fourth, the theme cultural expressions included any media format created for sharing a story of suffering, such as movies, documentaries, books (e.g. novels, autobiographies), podcasts with testimonies, videogames, and tv shows. For example, Case 88 said: “I quite often watch documentaries. These can be a range of different topics from rare medical conditions to oppressive regimes in foreign countries.”

The fifth and final theme did not explicitly refer to one source but to multiple ones and was labelled case follow-up. In some instances, participants engaged in an online search or tried in other ways to find out more details or background information about a situation of suffering. For example, Case 70 wrote: “I have educated myself on various places of conflict across the world including in Palestine, Syria and Lebanon. I have read about this online, attended educational events and listened to podcasts”.

Why did participants engage with the suffering?

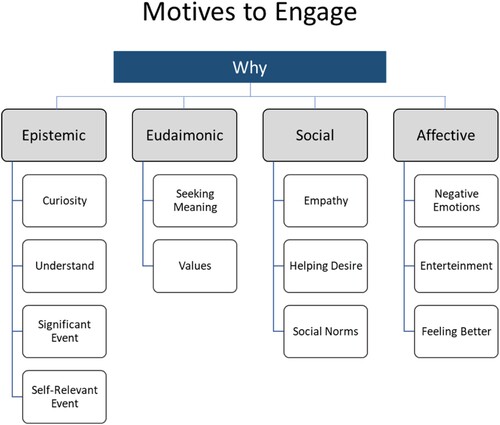

The coding of reasons why people engaged with the suffering of a stranger resulted in 12 themes of motives grouped into four overarching themes: epistemic motives, eudaimonic motives, social motives, and affective motives (see ).

Epistemic motives. This overarching theme represents motives that emphasise the informational aspects of the situation (e.g. due to their novelty) or the potential knowledge gained by engaging with the person’s suffering.

Curiosity. Participants described how curiosity-related states stimulated them to explore the situation of suffering. These instances often contained explicit references to epistemic states such as curiosity, intrigue, interest, and fascination (“I am interested in the psyche of the killers and find that fascinating”, Case 165).

Understand. This theme represented instances in which participants mentioned a motive to acquire knowledge or to understand (the cause of) the situation. More specifically, we coded as part of this theme instances that included the words “learn”, “knowledge”, “educate me” and “understand”. For example, “Trying to put myself in their shoes to understand what a person can think before committing suicide” (Case 49).

Significant event. Another theme that reflected the informational value present in the instance was labelled significant event. This theme includes references to the frequency of the event (e.g. something that happens very often or very rarely), the novelty of the situation (“it’s a sickness I had never seen before”, Case 147), high social impact (“I like to keep up to date with current affairs”, Case 165), or severe consequences for the person suffering (e.g. irreversibility).

Self-relevant event. Finally, as part of the epistemic motives, we included instances in which participants reflected on how the situation was connected to their own past or future. For example, “As mentioned, I experienced recent death which was the loss of my dear mother. This was the first major loss I have experienced and now have great empathy with others who are dealing with grief and bereavement” (Case 162). Furthermore, the theme included references to personal utility, in which participants mentioned how they themselves or their loved ones could potentially be in that position. For example,

Because I'm a girl who also likes to go to concerts and knowing that it could've been me or someone, I know is horrible. These people didn't deserve to suffer that much and that’s why it also got to me. (Case 56)

Eudaimonic motives. This overarching theme involved existential aspects that motivated engaging with the situation of suffering, including the pursuit of a meaningful life and a desire for self-actualisation. Note that these motives are different from the epistemic motives as they exceed the informational value of the event itself and instead refer to reflection, insight, and meaning-making processes to guide self-development (Bartsch et al., Citation2014).

Seeking meaning. This theme represented instances in which participants reflected on the value or deeper meaning of engaging with suffering. For example, some participants mentioned that suffering gives access to a raw reality or an insight into the human condition. Other participants described being inspired by stories of resilience and post-traumatic growth or reflecting on justice and solidarity

(I am passionate about social justice and work in an industry where these values are paramount (social work). After George Floyd's death I was angry and engaging with his experience was necessary to confront the injustice of what happened to him, Case 188).

Values. This theme represents instances in which participants referred to specific personality traits or personal values as reasons for engaging with the suffering, such as kindness, good citizenship, religious belief, or moral duty (e.g. “Because I am a Christian loving woman that loves everyone. God commands me to be the person I am”, Case 245).

Social motives. This overarching theme included motives that emphasised prosocial feelings or acts, socially desirable outcomes, and norms associated with situations of suffering.

Empathy. This theme included instances that used the words compassion, empathy, or sympathy, or other references to feeling concerned about the other, or taking the perspective of the other, such as feeling sorry for the other person, feeling their pain, wanting to empathise and putting themselves in the other’s shoes. Case 53, for example, stated: “I was just taken by his story, and I was overwhelmed with compassion”.

Helping desire. This theme included a need to help or do something about the situation of suffering. For example:

I like to help where I can, on social media, people usually share phone numbers or banking details where help can be sent. I usually sent something even if it is little but as long as it is helping even if it is a little. (Case 127)

Social norms. This theme included descriptions of how other observers influenced engagement with the suffering (“to be honest, I chose to engage because everyone around me was doing so” Case 181). Note that this theme reflected both reactions of support and dismissal of other observers, and situations in which an absence of others implied the need to react (“I chose to engage because there weren't many people around and it was obvious that they needed help. It was important that I helped otherwise they might have suffered further injuries.” Case 187).

Affective motives. This overarching theme referred to the emotional states associated with engaging with the suffering of strangers. In some cases, participants referred to the desired affective impact or anticipated emotional consequence of exploring the suffering of others. In other cases, the reason for engaging was an existing emotional state or feeling.

Negative emotions. The reason for engaging with the suffering situation included an explicit mention of a negative emotion (mainly anger, guilt, sadness, or worry). For example, “This incident just angered me.” (Case 253). This theme represents the (negative) emotional reaction experienced by the observer that was given as a reason or consequence of engaging with the situation of suffering. When a discrete negative emotion was explicitly experienced towards the suffering of the other, the instance was also coded as empathy (e.g. I felt sad for her).

Entertainment. Some participants explicitly referred to engaging with the situation to elicit pleasant emotional states such as amusement, fun, or schadenfreude. For example, participants mentioned enjoying horror stories, tragic novels, or online videos, given the thrill they produce (“it is also quite entertaining in a morbid way”, Case 147).

Feeling better. This theme reflected instances in which participants mentioned that the situation of suffering evoked a positive feeling about their own situation (e.g. gratitude) or a better perspective on their own life. For instance:

I engage with the suffering that comes with shootings in the USA because it is something I am not used to seeing in my country. In a way, the shootings make me feel safe because I know that all this is happening far, far away. (Case 181)

Discussion

The central aim of Study 1 was to develop a preliminary understanding of people’s motives to engage with the suffering of strangers. A secondary goal was to explore the breadth of the phenomenon by mapping the characteristics of the situations of suffering that people engaged with. Therefore, we developed a typology of the situations of suffering by describing who was the suffering person, what the situation was about, and how the participants accessed the content.

Regarding the who, participants described non-specified individuals (i.e. descriptions of the stranger without any personalised information), emblematic cases (e.g. famous people, well-known cases of suffering), and individuals with a clear social group membership (e.g. elderly, children, ethnic groups). This latter finding connects to work emphasising the importance of social identity and group membership (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) in social categorisation and social cognition (Bodenhausen & Kang, Citation2012). Regarding the what, participants described a large diversity of situations, including accidents, conflicts, health issues, race discrimination, human rights violations, and war. Consistent with work in social psychology (Vollhardt, Citation2020), sociology (Bourdieu et al., Citation1999), and anthropology (Wilkinson & Kleinman, Citation2016), the situations of suffering ranged on a continuum from individual to social suffering. Regarding the how, participants described different sources of information, such as online media, conversations, witnessing the event, and cultural products (e.g. books, documentaries, exhibitions), demonstrating diversity in the ways people acquire information about other people’s suffering. In the General Discussion, we will address the characteristics of the situation in more detail.

Regarding the why, participants described a large variety of motives that were relatively consistent with the theoretically derived motives described in the Introduction. We organised the motives in four overarching, theoretically driven themes: epistemic, eudaimonic, social, and affective motives. Regarding epistemic motives, participants reflected on the informational value of engaging with the suffering of other people (e.g. understand, learn, know). This is consistent with theoretical and empirical work emphasising knowledge acquisition as a prime motivator for seeking out (negative) information (e.g. Murayama, Citation2022; Niehoff et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, discrete epistemic states such as curiosity, interest, and fascination were frequently mentioned by participants. Interestingly, in some cases, the informational value seemed to lie in the perceived possibility that it was useful to engage with the event for personal or future purposes (i.e. instrumental utility, Dubey et al., Citation2022; Kelly & Sharot, Citation2021). Regarding eudaimonic motives, participants reflected on meaning-making processes and self-transcendent values. In line with perspectives in the literature on eudaimonia, people engaged with the suffering to gain insight in life itself and in the ways in which hardship is overcome (Bartsch et al., Citation2014; Koopman, Citation2015). Regarding social motives, participants reflected on altruistic reasons to engage with the suffering (e.g. helping), together with empathic responses that the situations of suffering evoked (Zaki, Citation2014). These motives emphasise the interpersonal value of engaging with suffering (Cameron et al., Citation2022). Regarding affective motives, participants reflected on the emotional impact of engaging with the suffering. In some cases, consistent with the theoretical perspective of Tamir (Citation2016), people reported negative emotions regarding the event as a reason to engage. These negative emotions may fuel an interest to learn more about the situation (e.g. moral outrage, Zembylas, Citation2021). In other cases, engaging with the situation evoked positive emotions (e.g. entertainment, schadenfreude) or a positive feeling towards the participant’s own situation (e.g. feeling better). In short, our results support the idea that people perceive value in engaging with other people’s suffering, by expanding their knowledge of the world, to connect with or help others, or to seek out eudaimonic or emotional outcomes.

Study 1 combined open-ended questions with online sampling. This approach allows for casting a wide net around the phenomenon under investigation (Braun et al., Citation2021). Indeed, the themes emerging from our qualitative coding show a rich and diverse landscape of situations of suffering as well as motives to engage with those situations. Nevertheless, the qualitative design does not provide insight into the prevalence of the motives that emerged. Therefore, the proposed taxonomy and the robustness of the motives’ endorsement should be evaluated using a quantitative approach. This was the objective of Study 2.

Study 2

Building upon Study 1, we performed a follow-up study to test the robustness of the motives that emerged from the qualitative study using a quantitative approach. First, to measure differences in motives endorsement, we operationalised the themes of Study 1’s taxonomy into items and asked participants to rate their applicability. Second, to explore differences in motives endorsement for specific contexts of suffering we incorporated two characteristics that appeared to be relevant in Study 1, namely differences in the type of suffering and the source of information. The first was inspired by findings about the identity of the stranger (who) and the type suffering (what). To address this variation, we asked participants to describe situations that affected members of social groups (e.g. minorities or historically marginalised communities, referred to here as social suffering) or situations that only affected an individual and their close environment (individual suffering). The second refers to a differentiation of the source of information (how) that allowed their engagement. To address this, we asked participants to rate motives for situations of suffering they accessed online, through cultural expressions, or in real life (i.e. direct witnessing).

Method

Participants

As this study is a follow up from Study 1, we aligned with the previous sample size, population characteristics, and inclusion criteria. Thus, 250 participants from Prolific completed the study between 28 April and 2 May 2022, with English fluency as an inclusion criterion. This sample size was defined to retain a similar diversity in instances across the two studies. In the Supplementary Material, we report a post-hoc sensitivity analysis for this sample size. The sample mean age was 31.73 (SD = 12.87), ranged from 18 to 76 years. 123 females, 123 males and 4 non-binary/other gender were part of the study. Participants reported 39 different nationalities; 40.8% were students. The study design was reviewed and approved by the local Ethics Review Board before data collection (approval code #2021-SP-14285). All participants gave informed consent prior to participation and received approximately £4.00 upon completion.

Procedure

The study had a 2 (type of suffering: social vs. individual suffering) × 3 (source of information: online vs. real-life vs. cultural expression) design, with type of suffering varied between-subjects and source of information varied within-subjects.

The procedure was similar to that of Study 1, with the following differences. First, considering that not all participants described the suffering of a stranger in Study 1 (i.e. some described the suffering of close others) a comprehension check was included. For participants who did not pass the comprehension check (39.2%), a feedback message was given highlighting that the study was about the suffering of people that they did not personally know. As in Study 1, cases that involved instances of suffering of close others, the participants themselves, or no suffering at all (i.e. when participants could not recall an instance of suffering), were excluded from the analysis (n = 44 instances out of 750 in total).

After the general instruction, half of the participants were asked to recall and describe a situation of a suffering individual (i.e. “individual suffering” condition) using the following prompt: “We are interested in situations in which you chose to explore, look into, or inform yourself about the suffering of an individual who you did not know personally, such as a complete stranger, famous person, or fictional character”. The other half of the participants were asked about the suffering of a member or members of a certain group in society (i.e. “social suffering” condition) using the following prompt: “We are particularly interested in situations of suffering that involve certain members of society, such as members of minority groups, or members of groups defined by certain characteristics, such as age or gender.” Participants were randomly assigned to one of these conditions. Supplementary Figure SM1 illustrates differences between the situations of suffering described by participants in the individual and social suffering conditions.

Each participant was asked to describe a situation in which the suffering was accessed by going online (e.g. through social media or an online news source), a situation in which the suffering was accessed through a cultural expression (e.g. by reading a book, watching a movie, soap opera, song lyrics, art expressions, going to a museum), and a situation in which the suffering happened in a real-life incident (e.g. as a witness on the street). These three questions were presented in a counterbalanced order. Participants had to work on each description for at least 2 minutes. In the Supplementary Material, we provide full details of the study materials and report the qualitative analysis of the situations of suffering described by participants.

Measures

Motives. For each shared situation, participants were asked to rate why they voluntarily engaged with it. They were presented with 32 statements about the value, function, or outcome of engaging with a stranger's suffering and asked to think carefully about the extent to which each of these applied to their decision. The items represented the twelve themes that emerged from Study 1 (for the full list of items please see Supplementary Material Study 2). Some themes were represented by multiple items to capture salient aspects (e.g. “I engaged with the situation because it was a way of helping” and “I engaged with the situation to show social support”). Other items were added based on insights from the larger literature on information seeking (e.g. boredom, Westgate, Citation2020; outrage; Zembylas, Citation2021). Specifically, the epistemic motives (9 items) included curiosity (e.g. “because I was curious”), understand (e.g. “to expand my knowledge about the world”), significant event (e.g. “because it was severely impactful”), and self-relevant event (e.g. “because a similar situation could happen to me or my loved ones”). For the eudaimonic motives (5 items), seeking meaning (e.g. “to gain insight in the human condition”), and personal values (e.g. “to become a wiser person”) were included. Social motives (7 items) included social norms (e.g. “because something like this should not be ignored”), helping desire (e.g. “because it was a way of helping”), and empathy (e.g. “to feel compassion for the people involved”). Finally, 11 items represented affective motives including entertainment (e.g. “because I was looking for a thrill”), feeling better (e.g. “to feel better about my own situation”), and negative emotions (e.g. “to feel sadness”). Our goal with this set of items was twofold. On the one hand, we wanted to be comprehensive by representing all motives that emerged from Study 1, but on the other hand, we wanted to limit the total number of items to keep the study manageable for participants. This led us to use the minimum number of items needed to capture the motives and their sub-facets. In some cases (i.e. for “singular” motives), one item was deemed enough to capture the essence of the motive. In other cases (i.e. for more complex, multi-faceted motives), we needed more items to fully capture the motive. Furthermore, given the number of items, we employed data reduction methods for grouping these items.

These items were previously tested and finetuned in a pilot study (for details see the Supplementary Material). Each of the 32 statements started with the phrase “I engaged with the situation … ”. Participants were asked to rate “the extent to which each of the following applies to you” with a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much.

Situation characteristics. To explore whether different situations of suffering differ in terms of severity, personal relevance, and frequency of the event, participants were asked a set of additional questions. First, participants rated the impact of the situation in terms of its consequences for (1) the individual(s) involved; (2) society at large, and (3) the participants themselves. Regarding personal relevance, participants rated how relevant the situation was in terms of their own past experiences or future personal lives. Finally, participants rated the frequency of the event (“How rare was the situation that you just described?”). Participants answered the questions on 7-point Likert scales (1 = not at all, to 7 = extremely). Importantly, the societal impact was rated significantly higher in the social suffering condition (M = 5.67, SE = .11, CI [5.44, 5.89]) than in the individual suffering condition (M = 5.08, SE = .11, CI [4.86, 5.31]), attesting to the effectiveness of this manipulation (F(2,430) = 5.73; p = .004). The two conditions did not differ in terms of impact on the stranger and on the participant (see Supplementary Material Table SM2). Analyses involving the other questions did not yield pertinent insights, so they are not discussed further. A full report of these analyses can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

We evaluated how the 32 items grouped together by running a Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The aim of this analysis was to reduce data complexity and facilitate the interpretation of the results. We used oblique rotation (direct oblimin) following common recommendations (Field, Citation2018). As the criterion for retaining components, we used the Kaiser’s criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1. Finally, items were averaged for each component to serve as input for the main analyses.

We performed a repeated-measures ANOVA to examine whether motive endorsement differed across sources of information, type of suffering, and/or their interaction. In cases of sphericity violations, we report the Greenhouse–Geisser correction. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni correction.

The quantitative data is available at the Open Science Framework.

Results

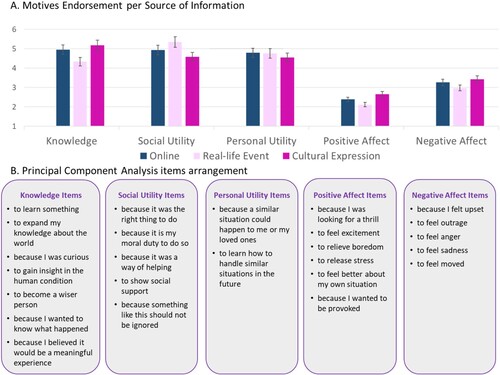

Motives categorisation

The PCA initially yielded a six-component solution as the best fit to the data, but the factor loadings of 6 items did not reach recommended thresholds (> .40 on the main factor, < .40 on alternative factors; see Supplementary Table SM2). The analysis was run again after excluding the items with poor fit (see Supplementary Table SM3). This resulted in a 5-component solution, explaining 59.96% of the variance. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure verified that the sample size was adequate for using PCA (KMO = .896). Bartlett’s test of sphericity χ2 (496) = 7789.89, p < .001, indicated a correlation structure adequate for the analysis.

The component structure emerging from the second iteration of the PCA was at follows. First, most of the epistemic motives’ items (e.g. curiosity, understanding, significant events) and the eudaimonic motives’ items (e.g. seeking meaning and personal development) organised together. We named this component “Knowledge”. Second, most of the social motives’ items are arranged together in a component that we named “Social Utility”. Third, the two self-relevant items grouped together in a component that we named “Personal Utility”. Due to dissimilar content and a switched sign for the factor loading, the rarity item was excluded from this component. Finally, affective items organised in two separate components according to emotional valence. The component named “Positive Affect” included items referring to positive-valence emotions while “Negative Affect”, included items of negative-valence emotions. B details the items that were included in each component. Details about factor loadings after rotation (Table SM3) and correlation between the five motives categories (Table SM4) are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Motives salience

We performed a 2 (type of suffering) × 3 (source of information) × 5 (motive category) repeated-measures ANOVA to examine the relative endorsement of the motives and to see whether motive endorsement differed across situations. A significant main effect was found for the motive category, F(2.928,629.52) = 277.73, p < .001, = .56, showing that participants differentially endorsed the five categories of motives. Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons demonstrated that Personal Utility motives (M = 4.07, SE = .09, CI [4.52, 4.88]) were significantly less endorsed than Social Utility and Knowledge motives (p < 0.001). Knowledge (M = 4.82, SE = .08, CI [4.67, 4.98]) and Social Utility (M = 4.96, SE = .08, CI [4.80, 5.12]) did not significantly differ (p > .90). Affective motives (Positive Affect (M = 2.39, SE = .08, CI [2.23, 2.54]) and Negative Affect (M = 3.22, SE = .09, CI [3.06, 3.40]) were significantly less endorsed than all the other motive categories (all ps < .001).

ANOVA also revealed a significant main effect of source of information (F(2,430) = 6.35; p = .002; = .03). Pairwise comparisons showed that, overall, the motives were more endorsed for cultural expressions (M = 4.08, SE = .06, CI [3.95, 4.20]) and online platforms (M = 4.06, SE = .07, CI [3.93, 4.19]) than for real-life encounters (M = 3.91, SE = .06, CI [3.78, 4.03]; p < 0.01). Furthermore, there was a significant main effect, F(1,215) = 12.47; p < .001;

= .06) of the type of suffering. Overall, motives were endorsed more for situations experienced by specific social group members (M = 4.22, SE = .08, CI [4.06, 4.37]) as compared to situations where the individual suffering was not specified (M = 3.82, SE = .08, CI [3.66, 3.98]).

The two-way interactions of motive category and type of suffering (F(2.93,629.52) = 0.85; p = .49), and source of information with type of suffering (F(2,430) = 0.79; p = .46) were not significant. However, the two-way interaction between source and motive category was significant F(6.27,1348.30) = 21.84; p < .001; = .10. After Bonferroni correction (αcor = α/15), pairwise comparisons (all ps ≤ .002) showed that Knowledge was endorsed more for cultural expressions and online content than for real-life events; highest endorsement for Social Utility was observed for real-life events, followed by online content and followed by cultural expressions; highest endorsement for Positive Affect was observed for cultural expressions, followed by online content, and followed by real-life events; and Negative Affect was endorsed more for online content and cultural expressions than for real-life events (see A). Finally, the three-way interaction of motive category, source and type of suffering was significant; F(6.27,1348.30) = 3.74; p < .001;

= .02. After Bonferroni correction (αcor = α/15), pairwise comparisons (all p’s ≤ .003) revealed that Social Utility was endorsed more for social situations than for individual situations but only for cultural expressions; Positive Affect was endorsed more for social situations than for individual situations but only in real-life events; and Negative Affect was endorsed more for social situations than for individual situations but only for real-life events. In the Supplementary Material, we include further detail of the descriptives (Table SM5 for the Motives and Source interaction and Table SM6 for the three-way interaction) and plots for the three-way interaction (Figure SM2).

Discussion

The first goal of Study 2 was to test the robustness of the motives that emerged from the qualitative study using a quantitative approach. Based on a PCA we extracted 5 components, Knowledge, Personal Utility, Social Utility, Positive Affect, and Negative Affect, which show considerable similarity with the results of Study 1. The most notable differences were that eudaimonic and epistemic items clustered together in a single component, self-relevant items clustered together in a single component, and affective items split into two separate components according to valence. When comparing endorsement between the different motives’ components, we found that participants endorsed Knowledge, Personal Utility, and Social Utility significantly more than both affective components.

The second goal of Study 2 was to explore whether different motives were associated with different situations of suffering. Generally, the motives were endorsed more strongly for social suffering situations as compared to individual suffering situations and more strongly for online content and cultural expressions as compared to real-life events. When comparing specific motives within (combinations of) conditions we found, most notably, that Social Utility motives (e.g. helping, moral duty) were most strongly endorsed for real-life events, whereas Knowledge motives (e.g. learning, understanding) were endorsed more for cultural expressions and online content than for real-life events.

General discussion

We investigated why people engage with the suffering of strangers. In Study 1, we employed a qualitative design to develop a typology of the situations of suffering that people generally engage with and to generate insight into the motives that explain this behaviour. Our thematic analysis demonstrated that participants engaged with different types of suffering strangers, ranging from completely anonymous to fully identifiable individuals (e.g. emblematic cases). Participants described a vast range of situations of suffering, varying from accidents and health problems to human rights violations and war. Participants informed themselves about the suffering of strangers through different sources, including online content, real-life events, cultural expressions, conversations, and a sequential search of different sources (i.e. case follow-up). The motives participants described were organised into a taxonomy that included four overarching themes: epistemic, eudaimonic, social, and affective motives. In Study 2, using a quantitative method, we examined the robustness of our qualitative findings by asking participants for their endorsement of these motives across different contexts of suffering and different sources of information. Five motive categories emerged from these data. Knowledge, Personal Utility, and Social Utility motives were endorsed significantly more than Positive- and Negative Affect. A significant interaction of motives and sources of information showed that Social Utility motives, such as helping and moral duty, were highly applicable to real-life situations. In contrast, Knowledge motives, including learning and understanding, were more frequently endorsed for cultural expressions and online content compared to real-life events. Below, we discuss these results in light of the existing literature, reflect on the strengths and limitations of our approach, and consider future directions.

What kind of suffering do people engage with?

Participants generated detailed accounts of situations in which they engaged with the suffering of complete strangers, in which they allocated cognitive and emotional resources to further understanding, exploring, or getting involved.

Regarding the characterisation of the stranger (i.e. the who), our results generally suggest that even in the absence of a personal relationship, and in the presence of a large physical- or temporal distance, the suffering of strangers can be salient. The finding that people are willing to put in resources to inform themselves about the suffering of strangers connects with work on people’s moral circle (e.g. a representation of beliefs about who in one’s environment matters, Waytz et al., Citation2019). Research on moral circles has shown that strangers are usually not central to people’s moral circle, but that a more inclusive moral circle has important societal and ethical implications (Anthis & Paez, Citation2021). The current findings suggest that complete strangers can become part of people’s moral circles, at least temporarily. Future work could examine to what extent deliberate engagement with stories about suffering results in the expansion of one’s moral circle, and impact awareness of injustice or prosocial action.

In some cases, participants described situations in which the suffering stranger was a famous person. This is reminiscent of the notion of parasocial relationships, in which people feel connected to media personalities and their personal lives (Dibble et al., Citation2016). Recently, it has been suggested that parasocial relationships can raise awareness about health issues, and even impact wellbeing by increasing social connectedness and promoting coping strategies and personal growth (Hoffner & Bond, Citation2022). For example, with regard to the “MeToo” movement, celebrities played an important role in creating awareness about the prevalence of sexual harassment (Cohen et al., Citation2021). Thus, seeking information about the hardship of celebrities may not only be driven by entertainment, but may also have an informative function.

Participants often referred to social group membership when characterising the stranger (e.g. children, black people). According to the Social Identity Model of Identity Change (SIMIC; Haslam et al., Citation2021), social group membership becomes more salient when people face life-changing events (e.g. (forced) migration, natural disasters, human rights violations; Ballentyne et al., Citation2021; Greenaway et al., Citation2015). Research has shown that people going through life changes often develop (new) social group memberships (e.g. survivors’ groups, patients’ associations) that help them to face and cope with the situation through a sense of community and shared experience (Greenaway et al., Citation2016). Although existing research in the realm of the SIMIC has exclusively focused on the first-person experience, there may be a relatively understudied role of observers or third parties in the recognition of changed identities. Indeed, the present results suggest that social identities are important aspects of the characterisations of suffering strangers.

Regarding the characterisation of the situation of suffering (i.e. the what), people described an incredibly diverse set of situations of hardship. These varied in terms of severity, urgency, and irreversibility, but generally, and consistent with existing literature on morbid curiosity, often involved death, violence, or harm (Oosterwijk, Citation2017). One aspect that emerged from the data is that participants often described situations of collective or systemic suffering (e.g. war, human rights violations, race discrimination). A relevant perspective from social psychology to contextualise this finding is work on collective victimhood, or the acknowledgement of structural and/or organised violence as a result of power abuse in intergroup contexts (Vollhardt, Citation2020). An initial step in the recognition of collective victimhood, called factual acknowledgment, involves the recognition of the targeted group, the events, and the context. A second step, called empathic acknowledgment, entails recognising the events as collective suffering, including the emotional consequences for the victims (Twali et al., Citation2020). These two initial stages of acknowledgement are processes that do not exclusively involve the perpetrators, but can also apply to society at large (e.g. in official narratives, through public memorials and commemorations, and restorative justice policies, see Twali et al., Citation2020). Our study prompts new questions about the role of the general public in learning and informing themselves about collective victimisation, including how engaging with stories of suffering can lead to both factual and empathic acknowledgement.

Regarding the characterisation of the source of the information (i.e. the how), our results showed a variety of ways through which people accessed the strangers’ suffering. First of all, participants often described real-life events as a way to engage with the suffering of other people (e.g. helping someone in the street, talking to other bystanders about an incident). Furthermore, online media and cultural expressions were salient sources, which resonates with work on (negative) news (Hoffner et al., Citation2009; Robertson et al., Citation2023), horror films (Andersen et al., Citation2020; Scrivner et al., Citation2022), true crime (Harrison & Frederick, Citation2022), sad novels (Koopman, Citation2015; Rozin et al., Citation2013), negative art (Hanich et al., Citation2014; Menninghaus et al., Citation2017), and even dark tourism (Magano et al., Citation2022). Our findings further indicate that some individuals exhibit a behaviour we labelled “case follow-up,” where they actively tracked a specific instance of suffering (e.g. an emblematic case) by gathering additional information from various sources. Previous research has identified two different information-seeking profiles that are relevant to this finding (Lydon-Staley et al., Citation2021). So-called hunters are characterised by targeting thematically related information, whereas so-called busybodies are characterised by a more exploratory, unstructured strategy, seeking very diverse content. Our case follow-up theme seems very similar to the hunters’ profile. Further research could explore individual differences in information-seeking styles, especially in the context of engaging with situations of suffering, using methods like momentary experience sampling to uncover motives, antecedents, and outcomes in the decision-making process.

Why do people engage with strangers’ suffering?

With regard to people’s motives for engaging with the suffering of strangers (i.e. the why), the current research offers a number of insights that align with and expand existing knowledge. First, in line with accounts of curiosity and information seeking (FitzGibbon et al., Citation2020; Murayama, Citation2022), participants both spontaneously mentioned (Study 1) and endorsed (Study 2) epistemic motives for engaging with a stranger’s suffering. In Study 2, knowledge acquisition motives were endorsed in particular for online media and cultural expressions as compared to real-life events. These findings suggest that stories about the suffering of others can offer a relevant source of information or knowledge to build (or fine-tune) a realistic model of the world (Niehoff & Oosterwijk, Citation2020). Moreover, many participants referenced (Study 1) or endorsed (Study 2) personal utility as a salient motive for engaging with other people’s suffering. Interestingly, people both mentioned (and endorsed) that they engaged with suffering because it related to events that happened in their past or because it could provide useful information that could help them to prepare for similar negative events in the future (see Niehoff et al., Citation2023, for a similar result). Note that the informational value of negative content could lie in generating fine-grained predictions about how to handle future negative events (Hoemann et al., Citation2017), but possibly also in learning how to support or react to others experiencing negative events. In this sense, our results connect with Emotions as Social Information (EASI) theory (van Kleef, Citation2009), which proposes that people use the emotional expressions and experiences of others as sources of information to streamline social interactions and to inform their decisions and actions. Our results suggest that people may also inform themselves about strangers who are temporally or physically distant (or even fictional) in order to better navigate the social world.

Second, and consistent with work from media psychology (Bartsch et al., Citation2014), our data showed that people find eudaimonic value in engaging with the suffering of strangers. In Study 1, participants reflected on the deeper meaning of engaging with the suffering of other people, the insights that it could bring, or the inspiration they found in stories of resilience. Although we initially separated epistemic and eudaimonic motives based on the qualitative data, the quantitative approach in Study 2 suggested that motives oriented around knowledge acquisition and eudaimonia are related. This may be due to the items that we used in Study 2, which were primarily focused on the cognitive component of eudaimonia (e.g. meaning-making, cognitive elaboration; Raney et al., Citation2020), possibly blurring the lines with epistemic motives. Future work could examine how emotions associated with eudaimonia, such as hope, awe, and elevation, relate to the deliberate engagement with the suffering of strangers.

Third, in addition to self-oriented and personally beneficial motives, participants reflected on other-oriented or social motives such as helping desire, seeking social connectedness, and empathy. These social utility motives were more strongly endorsed for real-life incidents as compared to online content or cultural expressions. With regards to motives oriented around helping, examples of helping strangers were abundant in our data, aligning with recent work that the norm is that bystanders assist strangers in situations of threat (Philpot et al., Citation2019). Moreover, people often mentioned engaging with the suffering of strangers to feel (or because they felt) empathy (Cameron et al., Citation2022). Interestingly, recent research has demonstrated that people often avoid empathy in laboratory contexts, presumably because it is mentally and emotionally costly (Cameron et al., Citation2019). Our findings, however, suggest that in daily life, people do seek out situations that evoke empathy, and perceive empathy as a valued outcome. Moreover, our results are relevant to a long-lasting discussion in the field of empathy (Batson et al., Citation1981; Cialdini & Kenrick, Citation1976), which revolves around the question of whether selfless altruism exists, or whether there are always traces of personal benefit when engaging with the suffering of others. According to our findings, these motives may co-exist, and people may engage with other people’s suffering for both other-oriented and self-oriented reasons. It is currently an open question whether people’s interest in the stories of strangers can make a difference for the people going through this hardship.

Fourth, across both studies, participants referred to positive and negative affective states as reasons to engage with the suffering of other people, although this motive category was endorsed less in comparison to Knowledge, Personal Utility, and Social Utility motives in Study 2. Even though approaching suffering may seem a counterintuitive decision, research has shown that some people seek out negative emotions for meta-emotional or hedonic purposes (e.g. feeling good about feeling bad; Andrade & Cohen, Citation2007; Koopman, Citation2015; Rozin et al., Citation2013). Moreover, other perspectives have suggested that negative experiences can be helpful to train emotion regulation skills from a safe distance (Menninghaus et al., Citation2017; Scrivner et al., Citation2022). Interestingly, sensation seeking, entertainment, or schadenfreude were rarely mentioned in Study 1 and received relatively low endorsement in Study 2, even though research has suggested that such concepts play a role in negative information seeking (Ouwerkerk et al., Citation2018; Zuckerman & Litle, Citation1986). One possible reason for this finding is that entertainment media related to suffering (e.g. horror movies) were not that often mentioned, so that our data may reflect an underestimation of the prevalence of entertainment-oriented motives.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

First, the evidence we collected is built upon idiosyncratic situations that participants recalled from their daily lives. This was a deliberate decision, aligned with the exploratory goal of the project to generate a rich and ecologically valid corpus of situations of suffering. Nevertheless, it is possible that people recalled events that stood out to them or were relevant to remember for reasons other than the person’s suffering. Although many of the examples people gave concerned day-to-day experiences, some examples were more extreme cases or rare anecdotes of incidents. Thus, based on our data it is difficult to draw conclusions about the frequency with which people engage with the suffering of others in their daily lives. Experience-sampling methods may shed new light on this question (see Grühn et al., Citation2008 for an example).

Second, we targeted people’s own insights into their motives to engage in situations of suffering. However, what people think was important for their decision may not fully cover the psychological mechanisms that drove their behaviour in the moment. For example, it is possible that some motives known to drive curiosity, such as the reduction of uncertainty (e.g. van Lieshout et al., Citation2020), may be more salient within the moment of decision-making as when recalling a situation sometime later. Moreover, some people may engage with suffering habitually, for example as in doomscrolling, defined as the persistent consumption of negative news (Shabahang et al., Citation2023). Research shows that doomscrolling can be conceptualised as a habit (Sharma et al., Citation2022) and may even have addictive properties (Shabahang et al., Citation2023). In these cases, more higher-order goals, such as eudaimonic or social motives, may be less important. Furthermore, it is possible that people were hesitant to share motives that they thought were socially undesirable. This could explain the relatively low endorsement of motives related to positive affect, including sensation-seeking motives. Taking these limitations into account, the present study derives a taxonomy of motives that captures people’s perceptions of the benefits of engaging with specific situations of suffering. This taxonomy can inform hypothesis generation and methodological decisions in future research. A next step is to test how the current motives predict actual decisions to engage with material that portrays the suffering of other people (e.g. stories, movies, images) when presented in a controlled research paradigm (see Niehoff et al., Citation2023 for such an approach).

Third, although this research provides relevant insights into the motives that relate to decisions to engage with the suffering of others, our findings do not provide direct insight in the motives that people may have to ignore, avoid, or disengage with other people’s suffering. Nevertheless, just as decisions to engage, these decisions may be based on the weighing of (perceived) costs and benefits (Niehoff & Oosterwijk, Citation2020). In relation to ignoring situations of suffering, we speculate that if people do not perceive any value or benefit of engaging with the situation, they may respond with indifference. In relation to avoiding situations of suffering, insights may be gleaned from the motivated empathy perspective which states that such avoidance occurs when the costs of engaging surpass the benefits (Cameron et al., Citation2018; Zaki, Citation2014). Similarly, people may avoid suffering when they anticipate that the emotional costs will be too high, although this relationship may not be linear. For example, recent research on negative news consumption demonstrated an inverted-U shape relationship between anticipated feelings and the likelihood of choosing to read negative COVID-19 news (Niehoff et al., Citation2023). In other words, both the anticipation of strong feelings, and the absence of feelings, could be related to avoidance. Finally, it is an open question to what extent a buildup of costly experiences (e.g. effort, negative emotions, empathy) may predict a switch from engagement to disengagement with the suffering of others.

Fourth, it is important to reflect on possible constrains on the generalisability of our findings to other contexts and populations. The situations of suffering shared by participants were highly idiosyncratic and tied to their specific time, place, and reality. Considering the rather large number of events that went into our analyses and the wide variation we observed in the types of events, it is reasonable to assume that the current corpus of situations and typology of motives paints a relatively comprehensive picture of (reasons to engage with) suffering situations, suggesting that the results we obtained will generalise to other contexts. Nevertheless, in Study 2 we found some support for the idea that the relative importance of motives can be moderated by the source of information (e.g. social motives were endorsed more for real-life events). Moreover, Study 1 suggested that some motives are tied to certain contexts. For example, some participants reported that they engaged with suffering to become aware of social injustice. It is an open question whether endorsement of justice-oriented motives significantly increases for particular situations of suffering (e.g. stories of police brutality; human rights violations). Furthermore, we acknowledge that although Prolific provides good-quality data (Eyal et al., Citation2021), it is biased towards WEIRD populations (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic; Henrich et al., Citation2010). More research is needed to establish the generalisability of the current findings to non-WEIRD populations.

Finally, based on our data we cannot distinguish between expected outcomes of engaging with other people’s suffering and actual outcomes. For example, people might say that they engaged with a situation to learn or show social support, but it is yet unclear whether people indeed found the knowledge they sought or were able to provide social support. Future research that manipulates people’s engagement with a stranger’s suffering could investigate the extent to which such content indeed meets the expected goals.

Conclusion

Stories of suffering can be disturbing, distressing, or heartbreaking. Nevertheless, the present studies demonstrate that people deliberately engage with stories about a wide variety of suffering, including death, war, discrimination, physical and mental health problems, interpersonal conflicts, and many more. When asked about their reasons, people both spontaneously mentioned and endorsed motives to learn about the world and other people’s lives, to fulfil their values and moral standards, to empathise and help others, to prepare for future events, and to experience positive and negative emotions. These insights provide a stepping stone towards a better understanding of a pervasive human behaviour that may be key to sustaining humane relations in our current hyperconnected world.

Supplementary Material - resubmission 2.docx

Download MS Word (129.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anne Waldeck for her contribution with the qualitative analysis of Study 2.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The studies' materials are detailed in the Supplementary Material. The codebook (Study 1) and the quantitative data (Stusy 2) are available at the Open Science Framework. The raw qualitative data is available upon request.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Faculty Ethics Review Board previous to data collection (Study 1: #2021-SP-13343, April 8th, 2021. Study 2: #2021-SP-14285, January 18th, 2022).

Declaration of contribution

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies. All authors contributed equally to the project conceptualisation, methodology, original draft writing, reviewing and editing. Anastassia Vivanco Carlevari contributed with a leading role in data curation, analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, and visualisation. Suzanne Oosterwijk contributed with a leading role in supervision and validation, and supporting role in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, and visualization. Gerben A. van Kleef contributed with a leading role in supervision, and supporting role in data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, validation, and visualisation.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abir, Y., Marvin, C. B., van Geen, C., Leshkowitz, M., Hassin, R. R., & Shohamy, D. (2022). An energizing role for motivation in information-seeking during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30011-5

- Andersen, M. M., Schjoedt, U., Price, H., Rosas, F. E., Scrivner, C., & Clasen, M. (2020). Playing with fear: A field study in recreational horror. Psychological Science, 31(12), 1497–1510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620972116

- Andrade, E. B., & Cohen, J. B. (2007). On the consumption of negative feelings. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1086/519498

- Anthis, J. R., & Paez, E. (2021). Moral circle expansion: A promising strategy to impact the far future. Futures, 130, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102756

- Ballentyne, S., Drury, J., Barrett, E., & Marsden, S. (2021). Lost in transition: What refugee post-migration experiences tell us about processes of social identity change. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 31(5), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2532