ABSTRACT

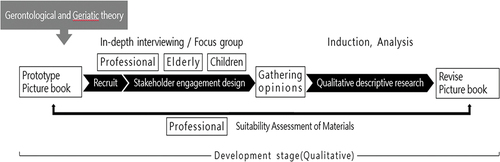

This study explored the preferences of different stakeholders when translating geriatrics and gerontology concepts into children’s picture books, with the aim of developing a feasible model. Following the stakeholder engagement design and qualitative method, three types of stakeholders were enrolled: medical and educational professionals (n = 9), older adults aged over 65 (n = 9), and children aged 9 to 12 (n = 7). Individual interviews and focus groups were used to collect the views of the stakeholders as a basis for revising the picture book, as well as to analyze the opinions of different stakeholders. Results show that medical professionals’ recommendations focused on intellectual content (18.0%) and written verbal narratives (16.5%). Education experts tended to recommend textual verbal narratives (18.8%) and storyline (6.0%). Older adults’s suggestions focused on story content (6.8%) and included detailed descriptions of older adults. Children’s suggestions were focused on plot arrangement (2.3%) and text size (2.3%). Mean scores for the appropriateness of the three picture book materials increased after the stakeholder engagement, with the communication literacy picture book achieved statistical significance (p = .042). It is concluded that the stakeholder engagement design is a viable development model for achieving intergenerational understanding, realistic and theoretical goals, and bridging heterogeneity across the stakeholders.

Introduction

The advent of an aging society means that intergenerational relationships often last longer than ever before (Kemp, Citation2005). Intergenerational understanding creates a strong support network, in turn increasing friendship, sharing and confidence between generations and relieving the social pressures of aging (Boger & Mercer, Citation2017; Springate, Atkinson, & Martin, Citation2008). There is also literature that suggests that the more children understand of older adults the more older adults feel a sense of belonging, live in peace and age comfortably when they are still living independently in the community. (Masuda, Murashima, & Majima, Citation2018). However, there are many studies that suggest that discrimination against older adults may be more serious than previously thought because of the influence of the family and the media. Children’s negative attitudes toward older adults begin to develop at the age of five, and by the age of eight there are “clear negative perceptions” of older adults (Gilbert & Ricketts, Citation2008), demonstrating that children’s knowledge about aging needs to be taken seriously.

Despite the fact that intergenerational understanding has been shown to generate a good sense of community-wide cohesion and is a valuable tool in combating age-related isolation (Gualano et al., Citation2018), much of literature on geriatric learning targets either medical personnel or medical students (Bortz, Citation2015; Duane et al., Citation2011; Marvanova & Henkel, Citation2003; Reneker, Weems, & Scaia, Citation2016; Stiles & Haist, Citation1999; Zolezzi et al., Citation2018) or university students and teenagers (Gugliucci & O’Neill, Citation2019; Krout & McKernan, Citation2007; Nechasek & Carboni, Citation1980; Tanyi & Pelser, Citation2018). A type of literature that can be used with both the older adults and children is intergenerational service-learning (ISL), which focuses on gerontology-focused service learning (GFSL) (Hinck & Brandell, Citation1999) as the mainstream form of learning. Compared to learning-driven teaching, gerontology-focused service learning (GFSL) is more easily applied to students of all ages (Gualano et al., Citation2018). In addition, there is the lack of appropriate educational materials due to the abstract nature of language, emotions and empathy in relation to the developmental age of the child (Malloy-Diniz et al., Citation2007). Therefore, the appropriateness of the materials is important if we are to break through the limitations of intergenerational understanding and identify age-appropriate learning opportunities.

In the past, many papers in the field of child education have pointed out that picture books are good educational media for children (Surani et al., Citation2011). According to the literature, “picture book” is defined as a type of children’s literature and should have: Precise themes, limited concepts, interesting themes, refined and beautiful texts and pictures are main body or at least of equal importance to texts. In addition to teaching children about themselves, they have also been used to help children understand the concept of the “non-self” (Aiken, Citation1998; Jalongo, Citation2004; Shang Chih, Citation1992; Shulevitz, Citation1985) . Therefore, the use of picture books as a medium could be expected to be an opportunity to promote intergenerational understanding between elders and young children. At the same time, however, research has shown that teaching materials such as health education books tend to pay little attention to their applicability to the intended target population (Garnweidner-Holme et al., Citation2016). Therefore, this study is an attempt to use a stakeholder engagement design (stakeholder engagement), which emphasizes multicultural teamwork between all product stakeholders to provide ideas or allows them to be directly involved in the event development process (Goodman & Sanders Thompson, Citation2017), in order for the materials to be relevant to the needs of future users (Aner, Citation2016). In the field of aging, although the inclusion of stakeholder input has been widely recognized as leading to better product suitability, much of the literature on stakeholder engagement design has focused on health and care issues for older adults (Brailsford et al., Citation2009; Glover, Hillier, & Gutmanis, Citation2007; Spagnoletti, Resca, & Sæbø, Citation2015). Given that intergenerational understanding relates to multiple communities, a stakeholder engagement design may be also appropriate for issues that promote intergenerational understanding.

Promoting the intergenerational understanding can start with children’s knowledge about aging. Since there have many fields of aging knowledge, chose the right aging knowledge issue that is suitable for children is important for children to recognize the older adults. According to the theoretical foundation of gerontology and geriatrics, aging issues can be divided into many domains and falls and nutrition have been chosen as important contributors to health and well-being in later life. According to the literature, falls are the leading cause of accidental death and injury among older adults (Sun & Sosnoff, Citation2018) (Lusardi et al., Citation2017). Malnutrition can affect physical performance and is associated with a higher rate of falls (Trevisan et al., Citation2019) and higher mortality (Vellas et al., Citation1997). In psychosocial terms, communication is an important part of getting along with each other. Children could have a deeper understanding of their own grandparents with good and effective communication therefore interact more and prevent older adults from becoming isolated (Gross, Citation1990). Therefore, in this study, the aspects of falls, nutrition and communication were chosen as priority issues for children to understand. The study is also an attempt to introduce into the teaching materials information that can be observed, understood, prevented, or resolved in the community, so that children can understand and help their nearest and dearest older adults while they are still living independently.

To construct a story that appeals to children requires some particular method and details. According to theories related to children’s literature, “plain language” should be used when constructing stories (Aiken, Citation1998; Shang Chih, Citation1992) based on oral language, precision, and clarity and emphasizing the use of stories to present ideas with educational themes (Shang Chih, Citation1992), adapting to children’s preferred styles, emphasizing a smooth, concise, and clear plot or rhythm, creating clear characters, avoiding static narratives, the indoctrination of knowledge and explanations of moral norms (Shang Chih, Citation1992; Yeh, Citation1967). Through the use of these skills, it is expected that knowledge about aging can be passed on to children in a suitable way rather than being excluded by obscure words.

This study is aimed toward developing a series of informational picture books about aging knowledge that can be read by children through a combination of professional (medical and educational experts), stakeholders of interest (older adults), and users (children). Those picture books will be expected to be placed in classrooms and family room for children to read and have fun after class or school to achieve the goal of intergenerational understanding, enable older adults to age more comfortably when they are still living independently and accompanied by younger generation. The aims of the study include the following: (1) to translate geriatrics and gerontology information into children’s picture books through the use of a stakeholder engagement design, (2) to compare the similarities and differences between the stakeholders’ views of picture books, and (3) to develop possible and practical models and principles for transforming aging knowledge information into educational materials.

Method

Participants

To facilitate sampling, different types of picture book stakeholder groups were included in this study: professionals (medical and educational specialists) at a medical center and national university in Taiwan (n = 5) (n = 4), stakeholders of interest (older adults over 65 years old) (n = 9), and users (children aged 9–12 years old) at an day care center (n = 7), excluding those who were unable to view the picture book and engage in discussions. In-depth interviews were conducted, or focus groups were created for the stakeholder engagement design to collect the opinions of various types of stakeholders on the gerontology and geriatrics information picture book. The Ethical Committee for Human Research at National Cheng Kung University Hospital approved this study (A-ER-108-241).

Procedure

When the first draft of the picture book was created, empirical gerontology, geriatrics medicine, geriatrics syndromes, and the Comprehensive Gerontology Assessment were reviewed (Brailsford et al., Citation2009), aiming at information that children could observe and understand in the community or the acquisition of knowledge that could help prevent or solve problems. The three main topics chosen for the aging knowledge picture books were “falls” and “nutrition” in the physical context and “communication” in the psychosocial context. All of stories were constructed according to children’s literary theory. In the second stage, the stakeholder engagement design was introduced by including three groups of stakeholders in the picture book design process: professionals (medical and educational experts) (n = 5) (n = 4), stakeholders of interest (older adults aged 65+) (n = 9), and users (children aged 9–12) (n = 7). In-depth interviews or focus group discussions were conducted to allow the stakeholders to share their opinions on the first draft of the picture books about aging knowledge, which was used as a basis for revising the book.

Based on children’s literary preferences, the falls knowledge picture book was named “Grandma’s Socks.” The story used surprising situations, anthropomorphic characters, and familiar scenes to stimulate children’s interest. In this picture book, grandma’s striped socks were created as an anthropomorphic role that speak up for grandma, interacting with the young master. In the exciting night adventure, striped socks led the young master to discover the unfavorable situation of older adult, including physical limitations and the fear of being in a dangerous environment that are not acquainted with younger generation. To understand that the physical fitness of older adult and children are different as well as the difference of requirements for the environment. There are four main themes: physical aging makes falls dangerous, the seriousness of falls among older people, inappropriate environments, the relationship between behavior and falls and ways to prevent falls among older people as learning themes. The nutrition knowledge picture book, which was named “Grandpa Bear is Sick,” is based on a real-life story that uses anthropomorphic animals and dialogs to engage children’s attention. Through the bewildered sickness of close grandpa bear, the little bear is told by doctor that the nutritional problems of the older adult may be caused by the seemingly trivial toothless. It could easily cause the result of imbalanced nutrition, and if neglected, it is more likely to lead to serious physical diseases and nutritional problems. The four main topics include: key concepts of nutrition for older people, the link between teeth and nutrition, health problems caused by malnutrition, and how to prevent or improve malnutrition in older people, which are the learning themes in the area of senior nutrition. Communication knowledge picture book was named “You Just Have to Use the Right Method.” The picture book use warm colors and conversational situations to describe everyday family scenes. The little girl does have some confusion in beginning of the story. Why doesn’t grandma always answer her when she talks to her? Does grandma not understand what she talks about? Through those close conversation with grandma, the communication knowledge picture book brings out the misconceptions that children tend to have about the older adults and the skills they need to communicate with them. This picture book provides an introduction to the subject of communication with the older adults. The three main themes are: communication problems arising from physical aging, the myth that older adults have poor hearing and responses indicating poor cognition, and how to communicate correctly with older adults.

After the first draft of the picture book was created, interviews were conducted based on the stakeholder engagement design in the form of individual interviews with experts and children. The interview pacing was adapted to the characteristics of the different groups in order to understand their focus on the picture book. Older adults were formed into a focus group. The researcher served as a facilitator, guiding the focus of group discussions without using suggestive questioning or interfering with the process and content of each group’s conversations, and ensuring that participants were able and willing to give their own opinions. The individual interviews and focus groups were conducted in an open discussion style, allowing the thoughts and ideas of the stakeholder community to be fully expressed. When the feedback of three picture books from the individual interviews and the two focus groups showed a large number of repeated opinions, we believe that the collection of data is close to saturation. In the end, the three types of stakeholder interviews were retained in the form of verbatim transcripts.

Qualitative descriptive research (Lambert & Lambert, Citation2012) was used to codify the interviews and summarize the themes for analysis as the basis for the revision of the picture book. The suitability of the picture book before and after the revision was assessed using the Chinese version of the suitability of materials assessment form (Chang et al., Citation2014) ().

Measures

The tool used for assessing the suitability of the picture book before and after revision was the Chinese version of the Suitability Assessment of Materials (Doak, Doak, & Root, Citation1985), which was translated from the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM), a teaching materials assessment scale for written healthcare messages that covers six areas: content, literacy needs, graphics, typography, learning stimuli and motivation, and cultural appropriateness (Chang et al., Citation2014).

Analysis

The verbatim text of the interviews recorded using the stakeholder engagement design was coded using qualitative descriptive research (Lambert & Lambert, Citation2012). The coding themes were summarized based on connotation, and the concepts were aligned. The three types of stakeholder interviews were analyzed and used as the basis for the revision of the picture book. In addition, the suitability scale was used before and after the picture book revision to classify the materials into good, suitable, and unsuitable using cutoff scores of 40% and 70% (Chang et al., Citation2014). The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference in the suitability of the materials before and after the revision, thus completing the analysis of the suitability of the picture book.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

presents the characteristics of the three types of stakeholders selected after the adoption of the stakeholder engagement design: professionals (medical and education specialists) who are physicians, teacher training and education specialists, elementary school teachers, dietitians, and nurses (n = 9) with an average age of 53.44 years old, ranging from 42 to 63 years old. The average age of the stakeholders of interest (older adults that live independently) was 71.33 years, with an age range of 66–77 years. There were 3 males and 6 females (n = 9). The mean age of the users (children) was 10.71 years old, ranging from 9 to 12 years old, with 1 user aged 9, 1 user aged 10, 4 users aged 11, and 1 user aged 12, respectively. There were 4 boys and 3 girls (n = 7).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

Suggested content for the interview & thematic identification of conflict codes

Based on the content of the interviews, a bottom-up approach was used to summarize the stakeholders’ comments on the three picture books, and they were coded into themes for analysis. According to the scope of the suggestions, the coding themes were categorized into overall content suggestions and pagination suggestions. In addition, the suggestions were also categorized into broad conceptual themes, including intellectual content, storyline, and textual narrative, as well as visual suggestions such as typographic suggestions and font size. The three picture books were categorized by recommendation, and the results are summarized below:

Falls Knowledge Picture book (Grandma’s Socks): mostly suggestions for informational content. The concepts include correcting the knowledge that are missing or not mentioned in the first draft of the picture book. For example, “Adding the message that falls can occur even when sitting or lying down in a position different from standing” is one of those missing concepts. Other suggestions include pointing out the imperfect knowledge content and correcting the narrative that does not conform to the facts according to their own experience so as to have a more comprehensive concept of the prevention and conception of falls in old age. In addition, stakeholders recommended modifying the overly rigid content of the stories, emphasizing that the primary goal is to please the reader in order to achieve the goal of passing on aging knowledge.

Nutrition knowledge picture book (Grandpa Bear is Sick): Stakeholder comments focus on that not only should children know the importance of malnutrition in older adults but also need to know how to observe the signs of malnutrition. For example, “Strengthen the link between the impact of toothlessness on older adults,” and “weight loss is a proxy for malnutrition.” Besides, there are also many details of knowledge that need to be more precise, such us “revise and clearly define the distinction between food types and listed items.” The goal is to allow children to develop a series concept of nutritional knowledge in the picture book, knowing how to observe and understand conditions or prevent and solve problems. It is also suggested that the problem of “too much information on one page” be rectified, so that the important information is conveyed in a precise, concise manner; the story contains concepts that are easy for children to understand, and the content is smooth without losing the entertaining elements of the picture book.

Communication knowledge picture book (You Just Have to Use the Right Method): Suggestions relating to the knowledge content included: “Add the concept of low and loud voices;” “add the concept of keeping speaker’s face on the sunshine;” and “emphasize the impact of noisy environments.” Those was intended to give children a better understanding of how to communicate with older adults and the importance of correcting narratives to make characterization clearer and grandparent interaction more realistic. It was also suggested that the communication myths related to older adults and the skills of communicating with older adults should be presented separately to avoid confusion. The title of the book should also be amended to “Right Method” to better fit the content of the book.

After categorizing the stakeholder comments, apart from the differences in suggestions for content, it was clear that the recommendations for the three picture books were all based on increasing readability in terms of story content and wording, streamlining knowledge, and improving the fluency and logic of the stories, making the language more “plain language.” In terms of suggestions for pictures, some children and experts pointed out that there were “inconsistencies” in the picture books. For example, the fridge of a person who cannot eat is not empty. Therefore, it is important to correct the compatibility between the graphics and make the color palette more vibrant.

During the study, conflicting views were also found among the different stakeholders, suggesting that the use of a stakeholder engagement design could reflect the values of different communities. For example, in the falls knowledge picture book, medical and educational experts had different views on retaining “fall-causing drugs.” Although the opinions were quite different, the use of the stakeholder engagement design also offered opportunities for reconciliation. In the end, the medical and educational experts chose to remove the content and pages on fall medications, in line with the view that medication is in the medical field. In its place, the item “Inappropriate door threshold” and “Scattered wires can cause older adults to fall” was added to give children a more comprehensive understanding of environments that are conducive to falling. In addition to the presentation of the informational items, the education experts disagreed with each other on the choice of fonts. However, considering the differences in the development of individual children, a strict judgment was made to switch to a more reader-friendly, square font. Although all three picture books had experts who said that they needed to be annotated, the children’s opinions were that the absence of annotation marks would not be a problem, so they were not specifically annotated.

Comparison of stakeholder’s interview differences with picture books about aging knowledge corrections

The number and percentage of stakeholder comments coded for each of the three picture books are presented in . When comparing the number of suggestions given by different stakeholders, it can be seen that the medical experts were the stakeholders who gave the most suggestions among the three picture books (50.4%), followed by education experts (32.3%), then older adults (10.5%), and the lowest number of suggestions was given by children (6.8%). It was also observed that the suggestions of the medical experts were mainly focused on informational content (18.0%) and textual narrative (16.5%). The education experts’ recommendations focused on the words (18.8%) and the storyline (6.0%). In contrast with the medical experts, they gave less advice on informational content (3.8%). On the other hand, children’s suggestions were focused on plot arrangement (2.3%) and text size (2.3%). After consolidating the recommendations, it was clear that the medical experts gave the most advice in the areas of intellectual content (18.0%), storyline (9.0%), and typography (4.5%). Education experts gave the most advice in the areas of textual narrative (18.8%) and text size (3.0%). The older adults gave very few recommendations but gave more detailed advice on the depiction of interactions with grandchildren than the other groups. Also, unlike experts, suggestions for increasing readability leaned toward broader perceptual suggestions rather than direct verbal suggestions. Although children gave the least amount of advice, as users, their opinions were the most direct feedback on the suitability of the picture book for initial exploration. It can be seen that each of the three types of stakeholders had its own strengths, demonstrating the importance of a balance of stakeholder opinions.

Table 2. Number and percentage of coded comments from stakeholders.

The first draft of the picture book was then coded according to all the comments from the different categories of stakeholders and corrected on an article-by-article basis. The suitability of the picture book before and after corrections can be seen from the results of five professionals using the Teaching Material Suitability Scale (), where the average applicability scores of all of the picture books improved. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to examine the difference between the pretest and posttest scores. The result showed that only of the communication recognition picture book reached significance after the correction (p = .042). Nonetheless, given the increase in mean scores, it is fair to say that the assessors felt that the revised picture book had improved in terms of the suitability of the material.

Table 3. Textbook Suitability Ratings of First Draft picture book and Revised picture book – Verified using the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test.

Discussion

Although stakeholder-driven research has flourished in the field of aging in the past, it has not been applied to the field of intergenerational understanding, but only to aging-related matters. The development of models and details of the stakeholder engagement design has also been limited. Therefore, this study is unique in that it is the first attempt to use a stakeholder engagement design in the development of teaching materials about intergenerational understanding and the development of a model for applying the stakeholder engagement design to the development of teaching materials in order to present the concerns of different stakeholders and to understand the importance of the stakeholder engagement design in the field of intergenerational understanding.

An analysis of the interviews with professionals (experts), stakeholders (older adults), and users (children) revealed that the different stakeholders had different focuses, perspectives, and ways of making suggestions, which is in line with the literature suggesting that stakeholders are a heterogeneous group with multiple perspectives, needs, resources, abilities and interests (Aner, Citation2016; Goodman & Sanders Thompson, Citation2017). Comparing the suggestions of the different stakeholders, we found that the professionals made the largest number of suggestions, with the medical experts suggesting more often than the educational experts, placing a high value on both informational content and textual wording. In contrast, the education experts gave more advice on textual language. The older adults gave more advice on the representation of emotions and things related to their own experiences, and also on increasing the appropriateness for children. In order to increase readability, the experts were more inclined to embellish words directly, while the older adults were more inclined to give advice on overall perceptions, showing that the two types of stakeholders had different perspectives and approaches to things. Suggestions made by the children were fewer in number. Their subjective thoughts were, however the most intuitive form of feedback. Unlike the experts and older adults, who often had to gauge children’s thoughts to make suggestions, the suggestions from children were an important indicator of reading appropriateness. The results also showed that conflicting suggestions from different stakeholder groups on the same topic of discussion reflect the different values and perspectives, each with their own focus and characteristics. The development process influences the presentation of picture books in a unique way, but it also allows room for discussion and conflict resolution, allowing the opportunity to take into account the full range of perspectives. Therefore, the research suggests that all types of stakeholders are essential to the development of a product. As the literature suggests, the inclusion of a wide range of stakeholders allows for the formation of multi-faceted teams that can offset the existing distribution of power and inequality and create a model of co-creation (Aner, Citation2016).

It was found that implementing a stakeholder engagement design within a theoretical framework allowed the product to meet both realistic and theoretical requirements. It is found that most of stakeholder’s opinions can correspond to theories. In fact, they are not in conflict with each other and the ideas presented could even be validated theoretically with greater clarity, which proves that the model used in this work is both feasible and advantageous. In the study, it was observed that although the different stakeholders had different values and perspectives, under the stakeholder engagement design, different stakeholders had the opportunity and right to speak out for their own positions (Sanders & Stappers, Citation2008). This feature has a more significant impact in the field of intergenerational understanding. The diverse nature of these communities of stakeholders requires the use of such an approach to ensure that the development process is comprehensive and that it shapes what is relevant to them based on their individual influences (Aner, Citation2016). According to the findings of this study, a stakeholder engagement design can provide a space for theory and reality to intersect and interact, opening up more possibilities for intergenerational understanding and presenting new opportunities for intergenerational understanding between older adults and young children.

However, this study’s as a first attempt to apply a stakeholder engagement design to the field of intergenerational understanding has three limitations: (a) The development period did not include input for the picture books from literary art experts and children’s librarians. The lack of professional input on graphic art presentation and the input of children’s librarians could both limits the integrity of the picture book presentation. (b) A picture book that has not undergone a secondary development cycle will be limited in terms of presentation. (c) The gender imbalance in the representation of older adults may have led to neglecting the perspective of males. For future research, it is hoped that further quantitative studies can be conducted to test the practical effects of the stakeholder engagement design in the area of intergenerational understanding, and that more picture books about aging knowledge can be developed to improve children’s understanding of the different faces of older adults. Finally, it was found that a stakeholder engagement design is highly advantageous in the field of intergenerational understanding between the older adults and young children. In the future, stakeholder engagement designs can be used to further develop intergenerational understanding and more mature techniques so as to model the dialogue between stakeholder representation and stakeholders and in turn make the stakeholder engagement design model more accurate.

Conclusion

In this study, a stakeholder engagement design was used to transform the empirical knowledge of aging knowledge into a picture book that is in line with medical, educational, and literary theories, meets the expectations of professionals, does not contradict with the reality of older adults, and is suitable for children to read and be entertained. It was found that the stakeholder engagement design not only brings picture books closer to reality and theory at the same time, but also allows ideas from different perspectives to interact with each other to create a holistic view, which is ideal for use in the field of intergenerational understanding, where stakeholder heterogeneity is high – especially between older adults and young children, where there are more constraints. The study ultimately was an attempt to develop a theoretically-based development model using a stakeholder engagement design, where it was found that there are opportunities to increase the applicability and acceptance of relevant issues. It can be expected that using this feasible approach to conducting activities and projects could lead to new opportunities to improve intergenerational understanding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aiken, J. (1998). The way to write for children: An introduction to the craft of writing children’s literature. England: St. Martin’s Griffin.

- Aner, K. (2016). Discussion paper on participation and participatory methods in gerontology. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 49(Suppl 2), 153–157. doi:10.1007/s00391-016-1098-x

- Boger, J., & Mercer, K. (2017). Technology for fostering intergenerational connectivity: Scoping review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 250-250. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0652-y

- Bortz, K. L. (2015). Creating a geriatric-focused model of care in trauma with geriatric education. quiz E1-2 Journal of Trauma Nursing : The Official Journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses, 22(6), 301–305. doi:10.1097/JTN.0000000000000162

- Brailsford, S. C., et al. Stakeholder engagement in health care simulation. In Proceedings of the 2009 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC). Austin Texas, 2009.

- Chang, M. C., Chen, Y. C., Gau, B. S., & Tzeng, Y. F. (2014). Translation and validation of an instrument for measuring the suitability of health educational materials in taiwan: Suitability assessment of materials. The Journal of Nursing Research, 22(1), 61–68. doi:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000018

- Doak, C. C., Doak, L. G., & Root, J. H. (1985). Teaching patients with low literacy skills. AJN the American Journal of Nursing, 96(12), 16M. doi:10.1097/00000446-199612000-00022

- Duane, T. M., Fan, L., Bohannon, A., Han, J., Wolfe, L., Mayglothling, J., Whelan, J., Aboutanos, M., Malhotra, A. & Ivatury, R. R. (2011). Geriatric education for surgical residents: Identifying a major need. The American Surgeon, 77(7), 826–831. doi:10.1177/000313481107700714

- Garnweidner-Holme, L. M., Dolvik, S., Frisvold, C., & Mosdøl, A. (2016). Suitability assessment of printed dietary guidelines for pregnant women and parents of infants and toddlers from 7 european countries. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 48(2), 146–51.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2015.10.004

- Gilbert, C. N., & Ricketts, K. G. (2008). Children’s attitudes toward older adults and aging: A synthesis of research. Educational Gerontology, 34(7), 570–586. doi:10.1080/03601270801900420

- Glover, C., Hillier, L. M., & Gutmanis, I. (2007). Stakeholder engagement and public policy evaluation: Factors contributing to the development and implementation of a regional network for geriatric care. Healthc Manage Forum, 20(4), 6–19. doi:10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60085-3

- Goodman, M. S., & Sanders Thompson, V. L. (2017). The science of stakeholder engagement in research: Classification, implementation, and evaluation. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(3), 486–491. doi:10.1007/s13142-017-0495-z

- Gross, D. (1990). Communication and the elderly. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Geriatrics, 9(1), 49–64. doi:10.1080/J148V09N01_05

- Gualano, M. R., Voglino, G., Bert, F., Thomas, R., Camussi, E., & Siliquini, R. (2018). The impact of intergenerational programs on children and older adults: A review. International Psychogeriatrics / IPA, 30(4), 451–468. doi:10.1017/S104161021700182X

- Gugliucci, M. R., & O’Neill, D. (2019). Health professions education: Advancing geriatrics and gerontology competencies through age-friendly university (AFU) principles. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 40(2), 194–202. doi:10.1080/02701960.2019.1576658

- Hinck, S. S., & Brandell, M. E. (1999). Service learning: Facilitating academic learning and character development. NASSP Bulletin, 83(609), 16–24. doi:10.1177/019263659908360903

- Jalongo, M. R., 幼兒文學-零歲到八歲的孩子與繪本, ed. 林汝穎. 2004: 心理出版社股份有限公司. 249.

- Kemp, C. L. (2005). Dimensions of grandparent-adult grandchild relationships: From family ties to intergenerational friendships. Canadian Jornal on Aging, 24(2), 161–177. doi:10.1353/cja.2005.0066

- Krout, J. A., & McKernan, P. (2007). The impact of gerontology inclusion on 12th grade student perceptions of aging. Older Adults and Working with Elders. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 27(4), 23–40. doi:10.1300/J021v27n04_02

- Lambert, V. A., & Lambert, C. E. (2012). Qualitative descriptive research: An acceptable design. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 16(4), 255–256.

- Lusardi, M. M., Fritz, S., Middleton, A., Allison, L., Wingood, M., Phillips, E., Criss, M., Verma, S., Osborne, J. & Chui, K. K. (2017). Determining risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis using posttest probability. J Geriatr Phys Ther, 40(1), 1–36. doi:10.1519/JPT.0000000000000099

- Malloy-Diniz, L. F., Bentes, R. C., Figuereido, P. M., Brandao-Bretas, D., da Costa-Abrantes, S., Parizzi, A. M., Borges-Leite, W.& Salgado, J. V. (2007). Standardisation of a battery of tests to evaluate language comprehension, verbal fluency and naming skills in Brazilian children between 7 and 10 years of age: Preliminary findings. Revista De Neurologia, 44(5), 275–280.

- Marvanova, M., & Henkel, P. J. (2019). Continuing pharmacy education practices in geriatric care among pharmacists in the Upper Midwest. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 59(3), 361-368

- Masuda, S., Murashima, K., & Majima, Y. (2018). Virtual teaching materials developed for elementary school students to foster support capabilities for elderly people with dementia. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 250, 70.

- Nechasek, J. E., & Carboni, D. K. (1980). The impact of a gerontology curriculum in a college of health sciences. Journal of Allied Health, 9(2), 95–101.

- Reneker, J. C., Weems, K., & Scaia, V. (2016). Effects of an integrated geriatric group balance class within an entry-level doctorate of physical therapy program on students’ perceptions of geriatrics and geriatric education in the United States. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 13, 35. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2016.13.35

- Sanders, E. B. N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068

- Shang Chih, T. (1992). Research on children’s story writing (Vol. 307). Taipei, Taiwan: Wu-Nan Book Inc.

- Shulevitz, U. (1985). Writing with pictures: How to write and illustrate children’s books (Vol. 272). New York, United States: Watson-Guptill.

- Spagnoletti, P., Resca, A., & Sæbø, Ø. (2015). Design for social media engagement: Insights from elderly care assistance. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 24(2), 128–145. doi:10.1016/j.jsis.2015.04.002

- Springate, I., Atkinson, M., & Martin, K., Intergenerational practice: A review of the literature. LGA research report F/SR262. 2008: ERIC.

- Stiles, N., & Haist, S. (1999). A four-year longitudinal gerontology curriculum for medical students. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 74(5), 584–585. doi:10.1097/00001888-199905000-00053

- Sun, R., & Sosnoff, J. J. (2018). Novel sensing technology in fall risk assessment in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 14. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0706-6

- Surani, S., Reddy, R., Houlihan, A. E., Parrish, B., Evans-Hudnall, G. L., & Guntupalli, K. (2011). Ill effects of smoking: Baseline knowledge among school children and implementation of the “AntE Tobacco” project. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2011, 584589-584589. doi:10.1155/2011/584589

- Tanyi, P. L., & Pelser, A. (2019). The missing link: Finding space for gerontology content into university curricula in South Africa. Gerontology & geriatrics education, 40(4), 491-507

- Trevisan, C., Crippa, A., Ek, S., Welmer, A. K., Sergi, G., Maggi, S., Manzato, E., Bea, J. W., Cauley, J. A. Decullier, E., Hirani, V.,Lamonte, M.J., Lewis, C.E.,Schott, A.M.Orsini, N.& Rizzuto, D. (2019). Nutritional status, body mass index, and the risk of falls in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(5), 569–582.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2018.10.027

- Vellas, B. J., Hunt, W. C., Romero, L. J., Koehler, K. M., Baumgartner, R. N., & Garry, P. J. (1997). Changes in nutritional status and patterns of morbidity among free-living elderly persons: A 10-year longitudinal study. Nutrition, 13(6), 515–519. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00029-4

- Yeh, K. Y. (1967). A study of the development of children’s reading interests in Taiwan. The National Chengchi University Journal, 16, 305–361.

- Zolezzi, M., Sadowski, C. A., Al-Hasan, N., & Alla, O. G. (2018). Geriatric education in schools of pharmacy: Students’ and educators’ perspectives in Qatar and Canada. Curr Pharm Teach Learn, 10(9), 1184–1196. doi:10.1016/j.cptl.2018.06.010

Appendix

Stakeholder’s comment code, and example of the picture book before and after correction

Table