ABSTRACT

Interdisciplinary education and research foster cross disciplinary collaboration. The study of age and aging is complex and needs to be carried out by scholars from myriad disciplines, making interdisciplinary collaboration paramount. Non-formal, extracurricular, and interdisciplinary networks are increasingly filling gaps in academia’s largely siloed disciplinary training. This study examines the experiences of trainees (undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate students) who belonged to one such network devoted to interdisciplinary approaches to education and research on aging. Fifty-three trainees completed the survey. Among respondents, some faculties (e.g., Health Sciences) were disproportionately represented over others (e.g., Business, Engineering, and Humanities). Most trainees valued their participation in the interdisciplinary network for research on aging. They also valued expanding their social and professional network, the nature of which was qualitatively described in open-text responses. We then relate our findings to three types of social capital: bonding; bridging; and linking. Finally, we conclude with recommendations for the intentional design and/or refinement of similar networks to maximize value to trainees, provide the skills necessary for interdisciplinary collaboration, and foster egalitarian and representative participation therein.

Introduction

Aging is considered a multi-faceted and complex biophysiological and psychosocial process directed by the interaction between individual disposition and context (Beard et al., Citation2016). As such, investigative teams in aging and aging-related research needs to be cohesive, complementary, and interdisciplinary. Interdisciplinary research occurs when scholars from more than two disciplines leverage their unique perspectives and integrate their theoretical and methodological approaches to solve a shared problem (Aboelela et al., Citation2007). By 2025, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) aims to establish the infrastructure necessary to promote interdisciplinary research on aging that enable collaboration and teamwork (Citation2020). This integrated infrastructure includes training “scientists across the full spectrum of research on aging” (NIA Citation2020, p. 39).

Academic institutions can foster opportunities for trainees to develop skills in devising and executing discipline-specific and interdisciplinary research. The McMaster Institute for Research on Aging [MIRA] at McMaster University (Hamilton, Canada), is one example of institutional infrastructure with a mandate to promote training in interdisciplinary research on aging. MIRA was formed in 2016 with the aim of advancing the science of aging by encouraging cross-disciplinary partnerships through funding collaborative projects, organizing knowledge exchanges that traverse disciplinary boundaries and involve community partners, and facilitating conversations between scholars interested in aging-related sciences (McMaster Institute for Research on Aging, Citation2021). Part of MIRA’s operational mandate was to also support the professional development of trainees: undergraduate, graduate, and post-doctoral student trainees who study age and aging, which was formed one year later, in 2017. Toward this aim, MIRA also offers a wide array of interdisciplinary programming, such as monthly networking and knowledge mobilization meetings. These MIRA-affiliated trainees have ample opportunities to engage in these initiatives, as well as others designed specifically for educational purposes, all intended to advance their skills and competencies in collaborating with researchers and peers in other disciplines. This study aimed to evaluate trainees’ engagement and perceived value of their membership within this institute, particularly within its trainee network.

Background

Research programs bringing together interdisciplinary experts from diverse specialties encounter multiple challenges. These challenges have been examined extensively in the literature and include, but are not limited to, differing epistemological and ontological beliefs, language barriers and discipline-specific jargon, contextual constraints in intentionally integrating theoretical concepts and research methods, competing priorities for recognition and career advancement, and logistics of coordinating complex interdisciplinary research (Bridle, Vrieling, Cardillo, Araya, & Hinojosa, Citation2013; Green & Johnson, Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2006; Hennessy & Walker, Citation2011; Pischke et al., Citation2017). Future researchers need to be trained to anticipate and circumvent these challenges. Unfortunately, the challenges to embedding interdisciplinary perspectives in research are also found in formal undergraduate and graduate-level university education. Such educational barriers to interdisciplinary training include overcoming diverse pedagogical approaches, valuing discipline-specific jargon, integrating ontology, epistemology, and methodological approaches, and conceptually challenging students’ disciplinary stances (Carr, Loucks, & Blöschl, Citation2018). Deliberate approaches that cultivate research trainees’ knowledge of and skills in interdisciplinary interactions are thus needed, particularly given the complexity of aging research (Bass, Citation2013; Finlay et al., Citation2019; Spelt, Biemans, Tobi, Luning, & Mulder, Citation2009).

Strategic applied health education has aimed to develop learners’ collective knowledge about geriatric and gerontological concepts, a better understanding of disciplinary roles, skills in shared decision-making and problem-solving, as well as skills in communication and conflict resolution (Flores-Sandoval, Sibbald, Ryan, & Orange, Citation2021; Holmes et al., Citation2020). Myriad pedagogical approaches have been used to develop competencies for cross-disciplinary collaboration, including online learning resources, toolkits, structured curricula, and case-based projects (Flores-Sandoval et al., Citation2021). These pedagogical strategies not only promote enhanced group dynamics, but also individual, discipline-specific confidence (Finlay et al., Citation2019; Holmes et al., Citation2020). Engaging graduate-level trainees in active learning initiatives with peers from diverse disciplines broadens individuals’ understandings of the breadth of disciplinary contributions in gerontology and geriatrics, methodological approaches, and opportunities for scholarly career advancement (Finlay et al., Citation2019). The nuances of mandatory or self-directed engagement, depth and duration of immersion, and nature of participation in interdisciplinary opportunities have received little attention, specifically for trainees in aging research.

There has been limited differentiation between collaboration, coordination, or networking, each of which vary in the purpose, characteristics, and performance of interdisciplinary teams (Reeves, Xyrichis, & Zwarenstein, Citation2018). Where collaboration and coordination necessitate shared responsibility for a common project goal with clearly defined team member roles, interdisciplinary networks allow for interactions to occur on a more ad hoc basis to facilitate a specific task or objective (Reeves et al., Citation2018). For research trainees, such interactions can support informal relationship-building with potential collaborators or future employers/ supervisors, resource and knowledge exchange between peers, and engagement with non-academic stakeholders/community partners. As a form of non-formal education, whereby learning is organized in some manner by an institution but for which no formal credits are awarded (Ainsworth & Eaton, Citation2010, p. 10), the value of networks developed in academic contexts to provide supportive infrastructure for interdisciplinary research on aging need to be explored.

The MIRA trainee network is a peer-led interdisciplinary network of undergraduate, graduate, and post-doctoral researchers-in-training who share an interest in aging, gerontology, and/or geriatrics. The trainee network is affiliated with the University’s interdisciplinary research institute, MIRA, which is made up of a network of faculty whose research also focuses on aging, gerontology, and/or geriatrics (for more information about the trainee network and research institution, please visit: https://mira.mcmaster.ca). The trainee network’s aim is to bridge disciplinary boundaries for the benefit of members’ professional and personal development, improve the depth and breadth of their interdisciplinary research, and enhance the potential impact and visibility within the academic and local community. Formed in 2017, the trainee network hosts over 100 members annually. Any students enrolled at the university and whose research also focuses on aging are eligible to become members. Membership and recruitment are managed by a council made up of trainees with the administrative support of MIRA staff.

The network’s mandate called for creating infrastructure to facilitate interdisciplinary interactions among trainees with an interest in aging research. The initial development of the network was grassroots and not guided by any particular gerontological or interdisciplinary competency frameworks. Activities hosted by the network and in which trainees could participate at the time of this study were: undertaking aging research programs (e.g., funding calls for interdisciplinary projects, scholarships, and fellowships); social events (e.g., monthly meetings where trainees share their research with time for open discussion, connecting at gerontological conferences); and training (e.g., research presentation days, webinars on research skills, grant-writing workshops, platform to practice presentations). Not all activities were developed solely for MIRA trainees, thus allowing trainees to interact with scholars, government officials, industry partners, and community stakeholders, such as older adults (see Appendix 1 for more details about MIRA’s programmatic offerings for trainees). Social events were led by trainees, with support from MIRA staff, while other activities were largely coordinated by MIRA staff. As such, trainees are self-directed in their ability to participate in these events, with some trainees taking an active role in research, social, and training opportunities, while others take a less active role (e.g., subscribing to the network’s e-newsletter). The value of developing, maintaining, and promoting infrastructure (i.e., membership in the MIRA trainee network and participation in associated activities) that facilitates interdisciplinary research on aging in an academic institution needs to be better understood. As such, the purpose of this study was to understand the experiences of trainees in aging research that participated in a learner-led network mandated to foster interdisciplinary learning experiences. Objectives of this study were to:

Examine trainees’ engagement in and perceived value of the MIRA interdisciplinary trainee network; and

Explore trainees’ experiences of membership and participation within the network.

Methods

Procedures

We developed a survey to understand the experiences of current (and former, where applicable) MIRA trainees, regarding the learning, research, networking, social, and career-related benefits offered through membership to this interdisciplinary trainee network on aging. This project was led by trainee investigators who received funding for the project from the institution’s teaching and learning center. Our aim in undertaking this study was to assess the degree to which the interdisciplinary trainee network was fostering a non-formal educational space that promoted student engagement and retention, particularly in under-represented disciplines. We also sought to determine whether involvement with the trainee network was perceived as a value-added experience to the traditional disciplinary learning and research activities of its membership.

Measures

Toward the aforementioned aim, we crafted survey questions that targeted the experiences of trainee network members. As no previous tool existed, the team of researchers developed an original survey tool (see Appendix 1). The survey first solicited demographic information, including year of study, program, research interests, and career aspirations. In consultation with MIRA staff, we then posed questions inquiring about areas for improvement within the trainee network to enhance the learning opportunities of the trainees, as well as improve engagement and retention rates. The latter sections of the survey asked respondents about their engagement and current experiences within the network, as well as the perceived value of those experiences, within the network. Herein, we asked about trainee’s personal development and enrichment as a result of participating in the MIRA trainee network, as measured by number of new connections fostered through network activities, and trainees’ experiences with regards to undertaking interdisciplinary research.

Once the research team reached consensus regarding survey design, and after we obtained ethics approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board at McMaster University (Project Number 7452), we pilot tested the survey among a small subset of the MIRA trainee membership. Upon receiving satisfactory pilot results (e.g., that the survey was easy to navigate, questions were easily understood, etc.), we launched the survey across the wider MIRA trainee network. Data collection took place in October 2019 and the survey was administered online via the university’s approved survey platform. At the time the online survey was launched, the MIRA trainee network had a membership of 181 undergraduate students, graduate students, and post-doctoral fellows representing all six faculties/school on campus. Trainees received an electronic invitation to participate in an online survey. Participants were aware that two respondents would be chosen at random to receive a gift card following full completion of the survey. The survey was set up in a manner such that no participants, including those in the pilot group, could take the survey more than once. Additionally, all responses to the survey were anonymized by the survey platform.

Participants

Fifty-three of the 181 trainees fully completed the survey; five partially completed the survey. Therefore, the response rate was 32%.

Participant characteristics

Survey respondents’ age ranged from 20 to 60 years (M = 29.07 years). The majority (n = 39; 76.5%) of respondents self-identified as female, with 10 respondents (19.6%) self-identifying as male, and one respondent (2%) self-identifying as “Gender fluid, non-binary, and/or two-spirit.” In terms of training level, respondents included 22 (43.1%) PhD trainees, 11 (21.6%) Master’s trainees, 10 (19.6%) Postdoctoral trainees, and six (11.8%) Undergraduate trainees. One (2%) respondent selected “Other training level.” Respondents also varied by faculty. Most respondents (n = 26; 51%) were Health Sciences trainees, followed by: Science (n =12; 23.5%); Social Sciences (n = 7; 13.7%); Engineering (n = 3; 5.9%); Business (n = 2; 3.9%); and Humanities (n = 1; 2%). Lastly, respondents varied in length of membership in the trainee network. Many respondents (n = 23; 45.1%) were members of the network for less than a year, while 14 respondents (27.5%) were members for between one and two years, and 12 (23.5%) were members for more than two years. One respondent (2%) was a former member of the network, and one respondent (2%) was not sure about their membership length.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

They survey included closed-ended questions and/or items requiring numerical responses. These questions included multiple-choice questions, Likert scales, and YES/NO-type questions. Descriptive statistics for relevant variables and participant characteristics were conducted using IBM SPSS 26.0 software.

Textual analysis

There were 12 questions on the survey eliciting open text responses (see Appendix 1). The first author performed all aspects of the textual analysis and engaged with “critical friends,” authors 3 and 6, and member reflections with the broader research team, who are/were also members of the trainee network, in order to ensure rigor in our analysis (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). When analyzing this data, the researcher first organized the participant responses by creating 12 tables, one for each of the questions. She then read the responses to each open text question to familiarize herself with the data. She identified the most common and notable responses from within the data. Each question was analyzed as an individual unit and reported in our results by question.

Results

In the section that follows, we first share the demographic and descriptive results of the survey. We then describe the results from the open text responses. Throughout, we focus on trainees’ perceived value of participating in the interdisciplinary network and the ways in which trainees fostered, and/or failed to foster, new connections as a result of their membership in the non-formal network.

Trainee experiences

Value gained

Survey respondents were asked “How valuable is your participation in [the network]?” Most participants (49%) felt that participation in the network brought them “high value,” and 41% of participants felt that it brought them “moderate value.” Three participants (5.9%) felt participation was of “low value,” and one participant (2%) expressed that they did not value participation in the network.

This variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable such that responses “Do not value” and “low value” were coded as “No or low value” and responses “Moderate value” and “High value” were coded as “Moderate or high value.” Frequencies divided by respondent faculty/school are presented in . Frequencies were also divided by training level and are presented in . In both cases, data did not meet the assumptions required for significance testing, so these are not reported.

Table 1. How valuable is your experience with [the network]? Frequencies by faculty/school.

Table 2. How valuable is your experience with [the network]? Frequencies by training level.

Responses to this question were also divided into sub-sample categories by length of membership (see ). Overall, 45 (94%) of respondents expressed that participation in the network was of “Moderate value” or “High value.” See for summary.

Table 3. How valuable is your experience with [the network]? Frequencies by length of membership.

New connections

Survey respondents were asked to identify how many new connections they made during their time in the trainee network. Specifically, respondents were asked about new connections made with other students they did not know before, with faculty across the university, and with various types of community members as a result of participating in network events and initiatives (i.e., older adults, industry, community organizations). The majority of respondents reported making at least one new connection with all types of connections with the exception of industry/community organizations and older adults. Responses to these questions are summarized in .

Responses to open text questions

Personal/professional development

We first asked, “How valuable is your participation in MIRA activities to your personal/professional development?” and about trainees’ direct or indirect benefits of participating in MIRA. Trainees shared that they were introduced to different disciplinary perspectives, thus gaining valuable insights into how research on aging is conducted in other disciplines. As such, trainees were inspired and able to try these new research methods and build their capacity as interdisciplinary scholars. As one trainee wrote, “Being part of MIRA allows me to see my work through a different lens. As well, by attending networking sessions and events I have had the opportunity to be exposed to leading figures in the field of aging.” When we later asked, “Is interdisciplinarity valuable to your research outcomes and career objectives?,” trainees noted that interdisciplinary skills were marketable or valuable within and outside of academia, were integral to the study of aging, and were increasingly required for grant funding, knowledge translation, and other research endeavors. Moreover, many trainees shared that they were aware of, and participated in, other interdisciplinary networks, both on and off campus.

Trainees also noted myriad individual benefits, such as networking and collaborating with other scholars. We inquired, “Have these connections enriched your overall training experience at McMaster University or informed career plans for the future?,” and some trainees agreed that these connections lead to jobs, grants, co-authorship on manuscripts, and opportunities for further education. Some benefits were realized right away: “I have been working on the [Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging] and MIRA helped connect me with other people also working on the dataset. This connection has been invaluable to me.” Other benefits required trust in future payoffs: “My academic and non-academic networks have expanded which have allowed me to consider non-academic career paths. I also have new ideas to merge into my current research portfolio.” Network activities provided trainees with practical experiences, such as presenting at monthly meetings or opportunities to apply for funding (e.g., travel awards and scholarships). Overall, when asked if there was anything else trainees would like us to know about with regard to their experiences with the MIRA trainee network, trainees shared very positive experiences overall.

MIRA truly enriched my experience at McMaster. Not only MIRA provided me with several opportunities to showcase my research outside my own department, but I could also meet wonderful people [MIRA staff] and other colleagues/researchers from various disciplines. MIRA broadened my vision and helped me reach a greater audience via its trainee website, trainee seminars and poster competitions session. I really appreciate all your efforts.

Interdisciplinary collaborations

In two follow up questions, we asked about the role the network played in fostering interdisciplinary collaborations (“Did MIRA facilitate or enable any of the above accomplishments?” and “Has your involvement with MIRA enabled you to expand on your own interdisciplinary network?”). Toward this end, trainees expressed that MIRA provided: 1) encouragement to undertake interdisciplinary aging research; 2) administrative structure to support building collaborations; 3) employment opportunities and funding; and 4) opportunities for exposure to interdisciplinary ideas, networking with diverse scholars, and knowledge translation activities (e.g., community presentations). Collectively, trainees felt that participation in the network facilitated the broadening of trainee’s perspectives from disciplinary to interdisciplinary and broadening of trainee’s social networks. Indeed, when asked if there were any activities or programs in which trainees would participate in if MIRA added to their programmatic offerings, trainees indicated a desire for more networking and interdisciplinary research training: “I would love to see an event where MIRA trainees get to meet with faculty members in something like a speed dating format” and “having a ‘Research Bootcamp’ or a half day training program of highlighting research methods from across departments and current opportunities for collaboration to add variables to existing or upcoming studies.” Evident herein is that MIRA offered opportunities that which departments and faculties/schools were not equipped to provide.

Facilitators and barriers to interdisciplinary work

Finally, we asked, “Within your research setting, what are the factors (e.g. at the personal, project, organizational, or institutional levels) that support or hinder (barriers) the successful adoption of an interdisciplinary approach?” Notably, trainees mentioned that it was important that their supervisor supported their participation in the interdisciplinary network, but other facilitators largely echoed the aforementioned personal benefits related to career advancement, skill development, and networking/collaborating. In terms of barriers, trainees cited both individual and structural barriers. Personal barriers included trainee’s personalities (i.e., too “shy”), overcoming their lack of interdisciplinary experience and training, and their attitude regarding interdisciplinarity. Structural barriers consisted of tradition of disciplinarity in academia, so the logistics supporting collaboration and networking are not built into the system:

“There seem to be so many barriers. Firstly, while the term interdisciplinary gets thrown around a lot, I sense that a lot of people are reluctant to undertake these projects since it’s messy and complicated to get set up, and even within MIRA it seems like it’s pretty forced to get people from different domains to work together. As a student, I really don’t have the tools necessary to form these collaborations, and my impression is my supervisor is too busy to facilitate the process for me.”

When specifically asked “What challenges in doing interdisciplinary work do you perceive, and how might they be overcome?,” trainee’s responses were twofold: 1) the need to learn how to communicate and work effectively in interdisciplinary teams from the outset of a project, rather than being retro-fitted in a manner that does not fully value each team member’s contributions; and 2) the need to innovate, rather than replicate traditional approaches to research. To overcome these challenges, trainees suggested: 1) finding common ground, such as aging, to bring together interdisciplinary scholars; 2) balancing the effort put into collaboration and finding ways to recognize interdisciplinary contributors; 3) creating an institutional culture that values interdisciplinarity by building interdisciplinarity into existing structures (such as publication, hiring, and promotion practices); and 4) allocating dedicated time and space to fostering collaborations, along with learning about research methods and scientific contributions from other fields.

Discussion

This study investigated student experiences within an interdisciplinary trainee network on aging. The findings suggest that many participants derived high or moderate value as a result of participation in the network, regardless of faculty/school or level of degree, with far fewer participants reporting low to no value from their experiences within the network. Most trainees also reported connecting with at least one other student, staff, faculty, or other network affiliated individual. However, few connections were made with industry/community organizations or older persons. In a network designed to foster collaboration across disciplines, these additional social connections were unfortunately few. In the section that follows, we will discuss some of the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Bonding

Our findings align with Putnam’s (Citation2000) three types of social capital: bonding; bridging; and linking. Social capital, according to Putnam (Citation2000) describes connections between individuals (in this case trainees) and the networks/groups to which these individuals belong. This lens and thus be useful in advancing our understanding of group dynamics in interdisciplinary collaborations (Finlay et al., Citation2019). Bonding describes the exclusive coherence of a group over shared identities (Putnam, Citation2000). In this study, trainees bonded over three shared identities: as researchers who study aging, as trainees, and as network members. However, trainees also needed to identify as interdisciplinary researchers to bond and cohere with other members of the network’s group. This is evident in respondents’ accounts of the personal barriers they expressed as barriers to adopting an interdisciplinary approach to their research. These personal barriers echo extant research (Bridle et al., Citation2013; Carr et al., Citation2018; Green & Johnson, Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2006; Hennessy & Walker, Citation2011; Pischke et al., Citation2017) and were related to trainees’ personality traits, valuation of interdisciplinarity, and attitudes. Thus, it could be surmised that trainees who identify heavily as disciplinary researchers, may fail to bond with trainees from other disciplines within the network, and might not attribute much value to their experiences in the network.

Bridging

It was shared identities as emerging interdisciplinary researchers and gerontologists that seemed to serve a bridging function into interdisciplinary practice. Bridging describes the act of bringing diverse individuals and/or groups together (Putnam, Citation2000). Indeed, the primary function of the network was to bring together trainees from diverse disciplines. Unfortunately, our data set consisted of mostly of trainees from Health Sciences (n = 26) and Science (n =12), with very few members from Engineering (n = 3), Business (n = 2), and Humanities (n = 1). This trend is in keeping with previous research that identified more course offerings related to aging in Health and Human Sciences than in Engineering and Business (Obhi et al., Citation2019). For aging education and research to be truly interdisciplinary, there is a need for greater inclusion of trainees from underrepresented disciplines in aging research. Therefore, to more effective bridge trainees from disparate disciplines, interdisciplinary networks, such as MIRA, must make a more concerted effort to attract and include trainees from Engineering, Business, and Humanities.

Linking

Finally, linking is when individuals gain affiliation with social and organizational institutions, such as MIRA (Putnam, Citation2000). As noted in our findings, MIRA supported interdisciplinary collaboration and networking (Reeves et al., Citation2018) by actively encouraging trainees to undertake interdisciplinary aging research, providing administrative structure to support interdisciplinary collaborations, offering employment and funding opportunities for interdisciplinary projects, and exposing trainees to other epistemologies, scholars outside of one’s discipline, and social and professional events. It is in this manner that MIRA responds to the NIA’s call for the creation of infrastructure to promote of interdisciplinary research on aging (Citation2020). Indeed, MIRA was instrumental for bringing interdisciplinary trainees together, and thus for bonding and bridging to have occurred. Meaning, trainees who join, and thus gain affiliation with the network, are linked to MIRA. Linking oneself to the network provided added value to trainee’s formal education in terms of additional qualifications, skills, social opportunities, and more. The network’s commitment to fostering interdisciplinary research was thus the catalyst for interdisciplinary collaboration, and in order for that mission to be effective, a strong, institutional presence was needed. However, trainees in our study recognized that in order to fully realize the benefit conferred by participating in the network, that they needed to be active participants in the network activities (i.e., you get out what you put into it).

Limitations

One primary limitation of this study, conducted in the early years of the MIRA trainee network is that due to the sample size there was not enough power to conduct statistical relationships (e.g., correlations or association) between perceived values for MIRA by faculty/school, program, and/or years of membership. Similarly, it is unclear the extent to which the respondents are representative of the full membership as demographic information was not collected from trainees upon joining the network. Also, this study reports findings from one interdisciplinary trainee network, and therefore findings might not be transferable, often known as inferentially generalizable, to other university networks devoted to aging education and research (Lewis, Citation2014; Smith, Citation2018). However, the findings resonated with the study’s authors, who are or were current and former members of the trainee network, thus fitting with the notion of representational generalizability (Lewis, Citation2014; Smith, Citation2018).

Implications for practice

Our findings highlighted myriad benefits of institutional involvement to initiate interdisciplinary collaboration. Some trainees in this study felt that they did not personally possess the tools necessary for fostering interdisciplinary collaborations, and as such an interdisciplinary research center on aging was essential for students to learn about and develop interdisciplinary research skills. We would therefore support the creation of, or strengthening of existing, interdisciplinary research centers on aging at other post-secondary institutions as critical infrastructure to support and train interdisciplinary aging researchers (NIA, Citation2020). Toward that aim, we offer some advice.

We recommend offering diverse means of engaging trainees, as well as asking membership of particular networks/institutes about the types of programming and outcomes from which they would most benefit. The MIRA trainee network offered myriad ways in which students could participate: monthly newsletters; monthly meetings highlighting trainees’ research programs; funding opportunities; events at which trainees could present their work; networking sessions with peers and notable scholars; skill development workshops; career advancement opportunities; and more. These events not only exposed trainees to other epistemologies and means of researching age and aging, thus broadening their perspectives, but were also opportunities for personal and professional development. Indeed, respondents to our survey expressed a desire for more networking and interdisciplinary research training.

We also recommend the intentional design of network activities to support interdisciplinary collaboration, as this might not otherwise occur organically. The MIRA trainee network’s aim is to support interdisciplinary aging research. Some aforementioned events, such as networking and social events, were vital to fostering new connections, but might not be sufficiently affecting interdisciplinary collaboration. It may be important to be mindful of trainees’ identities (e.g., identifying as interdisciplinary scholars) and the meaningful creation of opportunities (e.g., funding interdisciplinary projects) with the intent of fostering interdisciplinary collaboration.

Finally, we recommend being mindful to the barriers to interdisciplinary collaboration network members might experience, as well as the recommendations trainees espouse. The trainees in this study shared two main barriers they perceived to doing interdisciplinary research on aging. First, they identified the need for communication and project management skills needed for working effectively in interdisciplinary teams. Herein, trainees wanted to ensure that each team member was engaged early in the course of an interdisciplinary project and that all member’s contributions were valued. These are skills that networks could develop and build into their professional development offerings. Second, trainees noted that the interdisciplinary research with which they were familiar replicated traditional disciplinary research. These trainees noted a dearth of innovation when undertaking interdisciplinary research. As such, networks on aging could thus provide a safe space for trainees to experiment with new and innovative approaches.

Conclusion

Aging might be a necessary aspect of bringing together interdisciplinary scholars, educators, and trainees, but a shared interest alone is insufficient for fostering genuine interdisciplinary work. Herein, non-formal aging networks may serve a vital function in fostering interdisciplinary relationships, but again are insufficient without deliberate consideration of the institutional and personal barriers to interdisciplinary work. Many future gerontological and geriatric professionals and scholars value interdisciplinarity, and in this study trainees valued participating in such networks. However, participation therein should foster new connections across disciplines, and thus build trainees’ social capital. Yet, there remain many barriers to interdisciplinarity, despite the many benefits of engaging in interdisciplinary scholarship. This study adds to the large corpus of literature by advocating for the intentional design of non-formal aging networks in post-secondary institutions to more effectively develop the skills future aging scholars need to undertake interdisciplinary research on aging.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aboelela, S. W., Larson, E., Bakken, S., Carrasquillo, O., Formicola, A., Glied, S. A., … Gebbie, K. M. (2007). Defining interdisciplinary research: Conclusions from a critical review of the literature. Health Services Research, 42(1p1), 329–346. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00621.x

- Ainsworth, H. L., & Eaton, S. E. (2010). Formal, non-formal and informal learning in the sciences. Calgary, AB: Onate Press.

- Bass, S. A. (2013). The state of gerontology-opus one. The Gerontologist, 53(4), 534–542. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt031

- Beard, J. R., Officer, A., De Carvalho, I. A., Sadana, R., Pot, A. M., Michel, J. P., … Chatterji, S. (2016). The world report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. The Lancet, 387(10033), 2145–2154. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4

- Bridle, H., Vrieling, A., Cardillo, M., Araya, Y., & Hinojosa, L. (2013). Preparing for an interdisciplinary future: A perspective from. Futures, 53, 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2013.09.003

- Carr, G., Loucks, D. P., & Blöschl, G. (2018). Gaining insight into interdisciplinary research and education programmes: A framework for evaluation. Research Policy, 47(1), 35–48. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.09.010

- Finlay, J. M., Davila, H., Whipple, M. O., McCreedy, E. M., Jutkowitz, E., Jensen, A., & Kane, R. A. (2019). What we learned through asking about evidence: A model for interdisciplinary student engagement. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education, 40(1), 90–104. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1428578

- Flores-Sandoval, C., Sibbald, S., Ryan, B. L., & Orange, J. B. (2021). Interprofessional team-based geriatric education and training: A review of interventions in Canada. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 42(2), 178–195. doi:10.1080/02701960.2020.1805320

- Green, B. N., & Johnson, C. D. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: Working together for a better future. Journal of Chiropractic Education, 29(1), 1–10. doi:10.7899/JCE-14-36

- Hall, J. G., Bainbridge, L., Buchan, A., Cribb, A., Drummond, J., Gyles, C., … Solomon, P. (2006). A meeting of minds: Interdisciplinary research in the health sciences in Canada. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 175(7), 763–771. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060783

- Hennessy, C. H., & Walker, A. (2011). Promoting multi-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary ageing research in the United Kingdom. Ageing & Society, 31(1), 52–69. doi:10.1017/S0144686X1000067X

- Holmes, S. D., Smith, E., Resnick, B., Brandt, N. J., Cornman, R., Doran, K., & Mansour, D. Z. (2020). Students’ perceptions of interprofessional education in geriatrics: A qualitative analysis. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education, 41(4), 480–493. doi:10.1080/02701960.2018.1500910

- Lewis, J. (2014). Generalizing from qualitative research. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. M. Nicholls, R. Ormston. (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (2nd ed., pp. 347–366). London, UK: Sage.

- McMaster Institute for Research on Aging (2021). Our story. Retrieved from: https://mira.mcmaster.ca/about/about-us

- National Institute on Aging. (2020). The national institute on aging: Strategic directions for research, 2020-2025. doi:10.1097/00005650-199808000-00002.

- Obhi, H. K., Margrett, J. A., Su, Y., Francis, S. L., Lee, Y. A., Schmidt-Crawford, D. A., & Franke, W. D. (2019). Gerontological education: Course and experiential differences across academic colleges. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 40(4), 449–467. doi:10.1080/02701960.2017.1373348

- Pischke, E. C., Knowlton, J. L., Phifer, C. C., Gutierrez Lopez, J., Propato, T. S., Eastmond, A., & Halvorsen, K. E. (2017). Barriers and solutions to conducting large international, interdisciplinary research projects. Environmental Management, 60(6), 1011–1021. doi:10.1007/s00267-017-0939-8

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Reeves, S., Xyrichis, A., & Zwarenstein, M. (2018). Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: Why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(1), 1–3. doi:10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Smith, B. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: Misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(1), 137–149. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

- Spelt, E. J. H., Biemans, H. J. A., Tobi, H., Luning, P. A., & Mulder, M. (2009). Teaching and learning in interdisciplinary higher education: A systematic review. Educational Psychology Review, 21(4), 365–378. doi:10.1007/s10648-009-9113-z

Appendix 1:

Survey Questions

*denotes open-text questions

Preamble:

The MIRA trainee network offers multiple activities in which trainees might participate throughout the academic year. Some examples are described below, but these might vary each year depending on the strategic directions of the broader MIRA organization.

Examples of the MIRA trainee network’s knowledge mobilization activities:

Monthly meetings: One-hour meetings where MIRA staff will provide updates about MIRA initiatives and upcoming conferences/events/funding competition. This is followed by presentations by 1–3 trainee (who volunteer in advance of each meeting) on their aging research. Trainees have the opportunity to use these presentations to practice for the defenses/vivas and receive feedback from other trainees. Meetings end with social networking with refreshments (when in-person).

Labarge Annual Research Day: Annual research fair event hosted by MIRA and open to the public. This event consists of presentations by interdisciplinary faculty teams whose research was funded by MIRA and a poster session showcasing trainees’ aging research. Trainees have the option to participate in a poster competition for a cash prize. A key purpose of this event is to showcase the breadth of research supported by the institute and promote networking between scholars and other key stakeholders.

Other annual trainee-focused events: Example being “Meet My Method” where trainees share their data collection/analysis methods they use to undertake their research projects on aging-related topics. This event allows trainees exposure to multiple research tools with the aim of sparking dialogue and future collaboration.

Examples of social activities hosted by the MIRA trainee network:

Monthly meetings as described above.

Annually, trainees can register to attend a one-hour networking session with members of MIRA’s scientific advisory board, who are global leaders in aging research, for brief mentoring sessions.

Examples of training and capacity building activities hosted by MIRA:

Trainees are invited to attend MIRA’s and MIRA’s partners’ webinars and workshops showcasing work by aging researchers. Recent MIRA webinars have paired two researchers from different disciplines who research similar topics (such as physical activity and aging) to share findings from their recent projects.

Trainees can apply for scholarships (Master’s and Doctoral) and fellowships (Undergraduate, Doctoral, and Postdoctoral) funded by MIRA. These funding streams require trainees to be supervised by an interdisciplinary committee of faculty members from three different disciplines within the university.

Trainees can apply for professional development funds which can cover costs for age-related educational programming outside of one’s degree or for travel-related costs associated with attending and/or presenting at a gerontological or geriatrics conference.

Examples of interaction with end-users and other stakeholders facilitated by MIRA for trainees:

MIRA hosts multiple community-oriented events where trainees can present a poster or interactive station to disseminate their research to lay audiences.

MIRA can connect trainees to older community members who can advise on the design of trainees’ research proposals.

MIRA staff are also able to support recruitment initiatives for trainees.

Career/work opportunities:

MIRA shares job postings, funding calls, calls for proposals, and calls for abstracts in their communications with trainees (via a monthly e-newsletter or at announcements at monthly meetings).

MIRA partners with other organizations (such as AGE-WELL) to co-fund scholarships and fellowships. MIRA staff will connect trainees interested in applying with faculty whose research interests are well aligned to trainee’s research interest. MIRA staff will also advise trainees through the application process.

Survey Questions

The following survey was adapted to an electronic format for data collection.

Section One: Demographics

Age: (open-ended)

Gender: (Select: Woman, Man, Gender-Fluid/Non-Binary/Two-Spirit, OR Prefer Not to Answer)

Current training level: (Select: Undergraduate, Master’s, PhD, Post-Doc, Other)

Years of current academic program completed (Select: >1, 1 Year, 2 Years, 3 Years, 4 Years, 5 Years, 6 Years, 7 Years, More than 7 Years)

Primary faculty/school and program

Faculty (Select: Health Sciences, Social Sciences, Science, Engineering, Humanities, or Business)

Department or program: (open-ended)

List 5 keywords or phrases that describe your research interests (e.g., driver safety, muscle metabolism, age-friendly cities):

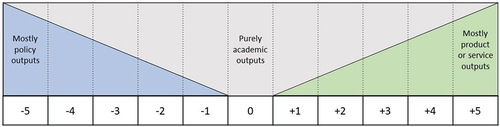

How would you position your research on the following scales?:

Please consider your research output (or desired output). If that output is solely academic, you would be at the center of the scale (0). If the outcomes of your work tend toward policy or products and services, you should place yourself closer to −5 or +5, as illustrated:

(b) Indicate where on a continuum your research would fit between completely focused on practice or application (0) or completely focused on theory and discovery (10), as illustrated:

(8) How would you describe your career plans?

I plan to pursue a career in the following field: (Select: Academic, Clinical, Non-Academic Research, Or Other)

I plan to work in a field: (Select: Related to Aging, Not Related to Aging, Or Not Yet Decided

(9) How long have you been a member of the MIRA Trainee Network? (Select: Less than a year, Between 1–2 years, More than 2 years, Former member, Or Not sure)

(10) Do you have, or have you ever had, a supervisor that is affiliated with MIRA? (https://mira.mcmaster.ca/team/researchers) (Select: Yes, No, or Unsure)

Section Two: Experiences of MIRA trainees

How frequently do you participate in the following MIRA activities?

Attendance at monthly meetings (11 annually):

□ Never attend

□ Seldom attend,1–2 meetings per year

□ Sometimes attend, 3–6 meetings per year

□ Attend most of the time, 7 or more meetings per year

i) How can we better facilitate your participation in monthly meetings? (select all that apply)

□ Send a calendar invitation

□ Different location

□ Different time and/or date

□ Provide more information about presentations

□ Improve diversity of content

□ Incentives for regular attendance (e.g., allocating a portion of awards to active members)

□ Better snacks

□ Other: ___________

(b) Attendance at MIRA events, (e.g., Networking Meetings, Research Fairs, Public Panels or Seminars, Pitch your Project, MIRA and Labarge Research Days):

□ Never attend

□ Seldom attend, 1–2 per year

□ Sometimes attend, 3–4 per year

□ Attend most of the time, 5 or more per year

(c) Presentation (oral, poster or exhibit) at a MIRA event (including monthly MIRA trainee meetings):

□ Never present

□ Seldom present, 1 event per year

□ Sometimes present, 2 events per year

□ Present regularly, 3 or more events per year

Have you experienced any barriers to presenting at MIRA events? (select all that apply)

□ Scheduling conflict

□ Not a good fit

□ Didn’t know about it

□ Not at the right stage in my research to share

□ Do not feel my research would be of interest to the group

□ Too shy

□ Other: ___________

(d) Applied for MIRA funding opportunities (e.g., scholarships, postdoctoral or undergraduate fellowships, travel grants):

□ Never applied

□ Seldom apply, 1–2 applications total

□ Sometimes apply, 3–4 applications total

□ Frequently apply, 5 or more applications total

Have you experienced any barriers to applying for MIRA funding opportunities? (select all that apply)

□ Not a good fit

□ Not eligible

□ Didn’t know about it

□ Too busy

□ Already funded

□ Difficulties with application process

□ Other: ___________

(e) Read MIRA monthly bulletins, newsletters or announcements:

□ Never

□ Seldom read, 1–25% of communications

□ Sometimes read, 25–74% of communications

□ Read most of the time, more than 75% of communications

i) How can MIRA improve its e-mail communication to trainees? (select all that apply)

□ Send fewer e-mails

□ More frequent e-mails about events

□ More frequent e-mails about MIRA funding and collaboration opportunities

□ More information about scholarships, external funding, etc.

□ More information about aging research at McMaster

□ Other: ___________

(2) *How valuable is your participation in MIRA activities to your personal/professional development? (Select: Do Not Value, Low Value, Moderate Value, or High value

Please explain. Comment box (open-ended)

(3) What aspects of the MIRA trainee network do you find most valuable? (Select: Do Not Value, Low Value, Moderate Value, or High Value)

Research sharing activities (e.g., monthly meetings, Labarge Day, conferences, etc.)

Social (e.g., networking sessions, food and beverage offerings)

Training and capacity building (e.g., workshops, mentoring webinars, etc.)

Interaction with end-users and other stakeholders

Career/work opportunities (e.g., securing post-degree opportunities including further training (e.g., post-doc) or work opportunities)

(4) How did you hear about and come to join the MIRA Trainee Network? (check all that apply)

○ Supervisor shared information

○ Fellow trainee shared information

○ Learned about MTN at MIRA or McMaster event

○ Learned about MTN at external event (e.g., conference, community event, etc.)

○ Other: (text response)

(5) Tell us about your accomplishments since joining the MIRA network, including those that may be unrelated to your membership in the MIRA trainee network.

Internal funding and monetary and non-monetary awards from the university (including MIRA, departmental, or university funding that you must apply or be nominated for (i.e., not guaranteed departmental funding as per terms of student contract), and grants?

External funding and monetary and non-monetary awards (e.g., Ontario Graduate Scholarship, CIHR award, Canadian Association of Gerontology award)?

Training and employment opportunities (either completed, in-progress, or planned for the near future)

*Other direct or indirect benefits to you or your research? (open-ended)

*Did MIRA facilitate or enable any of the above accomplishments? (open-ended)

Section Three: Trainee Personal Development/Enrichment

How many new connections have you formed as a result of participation in the MIRA Trainee Network?

How many new connections (i.e., someone that you have contacted, or plan to contact, outside of a MIRA activity) have you formed with MIRA trainee or faculty outside of your discipline as a result of participation in the MIRA network?

*Have these connections enriched your overall training experience at McMaster University or informed career plans for the future? (Select: Yes, No, or Unsure) Please explain in the comment box (open ended)

*Are there any activities or programs that you would participate in if MIRA were to add them to their support for trainees (E.g., informal trainee social activities, multidisciplinary aging research journal club, writing club, research club, co-design training, interdisciplinary training, certificate or other incentive for participation, etc.)? Please describe the proposed activities and/or programs and explain what benefit you would find from it.

What other activities would you benefit from that you would like to see provided by the MIRA Trainee Network? Please describe (open ended)

Section Four: Interdisciplinary Research

How would you rate your interdisciplinary collaboration experiences within the MIRA trainee network? (Select: Positive, Somewhat Positive, Neutral, Somewhat Negative, Negative, or Not Applicable).

Please explain your answer: _______________________________________________

(2) How much interdisciplinary collaboration were you exposed to prior to joining the MIRA trainee network? (Select: None, A Little, Quite a Bit, or A Lot).

(3) Which disciplines are represented on the research team of your primary research project? (e.g., exercise physiology and biomedical engineering; economics; rehabilitation sciences and labor studies, etc.) If possible, please list the disciplines in order of impact on the project.

(4) *Has your involvement with MIRA enabled you to expand on your own interdisciplinary network? Please describe how or why not. (Select: Yes, No, or Don’t Know)

○ Comment box (open ended)

(5) *Is interdisciplinarity valuable to your research outcomes and career objectives? Please explain why or why not. (Select: Yes, No, or Don’t Know)

○ Comment box (open ended)

(6) *Within your research setting, what are the factors (e.g., at the personal, project, organizational, or institutional levels) that support or hinder (barriers) the successful adoption of an interdisciplinary approach?

□ Supportive factors: (open-ended)

□ Barriers: (open-ended)

□ Unsure

(7) *Do you participate in other interdisciplinary teams outside of your MIRA involvement? If yes, which ones? (Select: Yes, No, or Don’t Know)

○ Comment box (open-ended)

(8) *What challenges in doing interdisciplinary work do you perceive, and how might they be overcome? (open-ended)

(9) *Is there anything else you would like us to know about your experience with the MIRA trainee network? (open-ended)