ABSTRACT

Residents’ lived experiences of movement into state directed housing frequently evidence contradictory outcomes. Often, movement is articulated in terms of displacement, noting its profoundly negative outcomes. However, displacement does not always fully capture contradictions, particularly where housing programmes form part of wider developmental strategies, themselves ambiguous in practice. Adopting a relational analysis, the paper argues for consideration of new sites of settlement relative to previous locations through a critical evaluation of place, as well as accounting for dynamism of urban change over time. Framings must capture residents varied and contradictory lived experiences and the relationality of place experiences. Contributing to work in this field, this paper calls for a broader analytical framing, named here as “disruptive re-placement”. Drawing on two different housing programmes, in South Africa and Ethiopia the paper charts movement into, and living in, state-led housing in three case study areas within three cities. It employs a ‘lived experiences’ methodology to understand these relocations, drawing on residents’ accounts of disruptive re-placement to examine the materialities of planned state-provided formal housing; the spatialities of disruptive re-placement; the economic and socio-political dimensions of these processes and the significance of temporality in shaping disruption. A continuum of disruptive and injurious re-placement, and a critique of the developmental state is used to articulate a just urban agenda in relation to relocation practices.

Introduction

State-directed housing programs are a growing phenomenon in parts of the global South (Lemanski et al., Citation2017) often resulting in the relocation of beneficiaries (Yntiso, Citation2008). New housing is built in situ or more commonly on alternative sites, often on the fringes of cities which can be poorly connected, reinforcing spatial segregation and fragmentation (Caldeira, Citation2017; Turok, Citation2013). At the same time, this housing can provide improved living conditions, and support desires for privacy and home ownership. In recent years, South Africa and Ethiopia have implemented such programs with an emphasis on private ownership, where relocation has often occurred as a result. Advanced under progressive policy rhetoric with a specific welfarist agenda (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017; Potts, Citation2020; Venter et al., Citation2015), these interventions have produced mixed outcomes for residents. For some, housing provision has proved very popular, with many eagerly awaiting its allocation. Yet significant variations in experience occur across space and time, and for many, outcomes are highly contradictory. There is substantial evidence of disquiet and suffering, often a direct function of these programs’ relatively poor location alongside the unaffordability of transport services; the unavailability and costs of services; prohibitive loan payments; poor build quality; reduced employment opportunities and social networks.

Interpretation and theorization of the contradictory nature of relocation and subsequent new ways of living through state-directed housing programs remain elusive, particularly where welfarist agendas are present. Globally, critiques of state-housing interventions inform anti-displacement activist practice (see Nowicki, Citation2020); and much academic work similarly theorizes processes of resettlement as evidence of displacement (see Coelho, Citation2016; Nikuze et al., Citation2019; Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017) noting their often-violent practices and marginalizing impacts (briefly discussed below). Other displacement practices (e.g. clearing of small-scale farmers from land, such as in Addis Ababa, see Tsegaye, Citation2021) can also be enacted to facilitate state-directed relocations or “displacements” of housing beneficiaries, although these are not the focus of this paper. Comprehensive recognition of the contradictory nature of state housing programs is also evident (see Hammar, Citation2017 on Zimbabwe; Chiu-Shee & Zheng, Citation2019 and Wang, Citation2020 on China; Buire, Citation2014 on Angola; De Pacheco Melo, Citation2017 on Mozambique; and Planel & Bridonneu on Addis Ababa, Citation2017) but there is less questioning of the applicability of the term displacement to interpret these messy realities (although see Beier et al., Citation2022; Wang, Citation2020). Additionally, there is insufficient work on the new lives that those who are relocated attempt to build (Wang, Citation2020) and this paper supports work in this vein.

This paper argues, therefore, that although much urban housing change directed by the state is captured by the term “displacement”, the term is less well equipped to depict the variations and contradictions in outcome and experience of relocation. Nor does it always capture the messy everyday realities for those who have moved, or their relative experiences of place within a context of often rapidly changing urban form. The paper’s contribution then is to respond to this challenge, agreeing that a “one-size fits all framework” of displacement (Wang, Citation2020, p. 2) can prove problematic. “Disruptive re-placement” is proposed in this paper as a conceptual framework that can help make sense of some urban movements through state-directed housing advanced through a welfarist or developmental agenda. Focusing on South Africa and Ethiopia, and the experiences of relocated residents in Addis Ababa, Johannesburg and Durban, the paper puts to work five analytical qualities of a “disruptive re-placement” lens to produce a more subtle theorization of relocation which includes: accounting for complex lived experiences; critically evaluating the varied places included in relocation events; recognizing the relationality of place experiences; accounting for the dynamism of urban change; and providing an analytic label that is both descriptive and critical. To achieve this, debates on resettlement and displacement are examined, presenting the idea of “disruptive re-placement” as a productive conceptual device. The “lived experience” methodology underpinning subsequent claims is detailed, followed by an overview of the housing programs and three case study sites under focus. Empirical material illustrates the analytical contributions of a “disruptive re-placement” lens, by examining the qualities of formal housing and related spatial elements, assessing its political, economic and social implications, and discussing the significance of temporality. Conclusions address how employing the lens of disruptive re-placement can inform a just urban agenda.

Displacement and resettlement within a developmental agenda: a search for a wider framing

This paper’s focus is on the lived experiences of “beneficiaries” of relocation (including displacement) produced by state-directed interventions in land and housing, informed by a developmental agenda. To examine this coalition of factors, this review first explores a critical reading of the developmental state to ground interpretations of the housing programs and displacements later analyzed. Then wider literature is reviewed teasing out the varying dimensions of displacement as an analytical construct, illustrating how the above factors, pertinent to this paper, are not always easily accounted for. The discussion then engages with scholarship on “displacement via housing programmes” which are productive in their recognition of paradoxical outcomes and sticky questions of temporality. Finally, fully cognisant of broader neoliberal forces shaping urban change, this review embraces gentrification and resettlement literature which privileges a political-economic critique, but it argues that the everyday and contradictory lived experiences are also a key site of political learning. It introduces the framing of “disruptive re-placement” as a conceptual device to address some of these concerns.

Government-directed welfarist or developmental agendas, relevant to both Ethiopia and South Africa and within which housing programs sit, may include “a universal urban franchise, opening up access to basic needs to all residents through an expanded state program of indigent support”. They can include commitments to citizen participation among other interventions (Parnell & Robinson, Citation2012, p. 605) and “more genuine attempts at creating inclusive and … transformative cities” (Mosselson, Citation2017, p. 352). Such developmental practices are by no means unambiguous, and outcomes are frequently contradictory (Mosselson, Citation2017, p. 381), however they reflect a particular political urban moment, which this paper argues is insufficiently incorporated in analyses of displacement, which often rest on a neoliberal critique. There are numerous reasons why the state may re-house citizens, including a desire to redress historical inequities and other welfare-related concerns (see Patel’s, Citation2016 work on this in India). Motivations around profit generation are simultaneously evident but the urban narrative is not simply neoliberal accumulation (Parnell & Robinson, Citation2012). Given this, analyses of urban processes (including displacement) in such contexts, must include a critique of sometimes progressively motivated (but often poorly implemented) urban policies and practices associated with the state, including planning, as integral, so that the contradictory outcomes of state housing can be articulated.

In a review of global literature on urban displacement, Hirsh et al. (Citation2020) identify four core often inter-related themes in this work: eviction, slum clearance, gentrification and development induced displacement (D.I.D) (Citation2020, p. 393). Our review centers on “slum clearance” as this partially aligns with relocation arising from state-directed housing programs, however the other “themes” of displacement hold some relevance to this paper too. Displacement through eviction and slum clearances can be tied to failures to pay rents or mortgages, or environmental and health concerns (Hirsh et al., Citation2020), among others. Declining state tolerance of squatting, and land clearances in advance of commodification, with land transfers to private developers can ensue (Caldeira, Citation2017), and resettlement can significantly bolster local authority tax bases. Durand-Lasserve calls for a broadened definition of market-driven displacement which “encompasses all situations where displacements are the direct or indirect consequences of a development aiming to make a more profitable use of the land” (Citation2007, p. 2) including non-forceful evictions where land values rise on parcels settled by residents with weak claims to the land, and those involving compensation. This emphasis on an accumulation logic is critical, however it does not reveal how relocated residents relationally experience the different places of relocation, nor offer a critical evaluation of these same places (origin, destination, etc.). In South Africa and Ethiopia, strategies for profit-making by the state or the private sector, often at the expense of the urban poor (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017) are evident, including for some living in the locations we address later. Yet there are important differences and divergences in policy implementation, housing outcomes and residents’ experiences between and within different countries, and between cities (Zhou & Ronald, Citation2017) and settlements. Impacts vary across beneficiaries, often but not always along class lines.

States’ claims to be improving “life conditions” through housing programs are central to this paper, and Hirsh et al.’s (Citation2020) argue these claims are evident in some slum clearance processes, such as efforts to rehouse residents in industrializing Britain. They contrast these with clearances of informal settlements and associated illegal activities (commonly in the global South). Arguably much current-day relocation through state-directed housing programs (often witnessed in global South contexts) is a combination of both. In many cases displacement is appropriately used to describe dire outcomes. For example, Coelho (Citation2016) examines problematic processes of resettlement, displacement and ghettoization occurring in India, and the physical, social, financial, human and natural impacts of pre- and post-relocation are detailed by Nikuze et al. (Citation2019) focusing on displacement in Rwanda. Planel and Bridonneau (Citation2017) analyze condominium housing in Addis Ababa noting their negative impacts on poorer residents particularly in relation to prohibitive costs. They describe some of these moves as displacement, and this paper concurs that numerous relocations in Addis are the displacement of the urban poor. Others identify the displacement consequences of exclusionary processes for the poor and lower-middle classes tied to state housing subsidies and provision (see Lemanski, Citation2014). There is substantial debate over different governments’ success at meeting poverty and social targets through housing relocation mechanisms (Chiu-Shee & Zheng, Citation2019; Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017; Venter et al., Citation2015; Zhou & Ronald, Citation2017). In nearly all contexts, including South Africa and Ethiopia, governments are often seen to have failed to meet the needs of the poor, or to have tackled poverty in sustainable ways (Ejigu, Citation2012; Huchzermeyer, Citation2010; Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017; Potts, Citation2020). These troubled welfarist agendas are pertinent to the contexts examined in this paper, setting the scene but also revealing too little about the ambivalence of urban residents experiencing location, including contradictory outcomes.

The paradoxical nature of displacement and resettlement is central to Hammar’s (Citation2017) arguments in the city of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe and productive for thinking through contradictory outcomes examined in this paper. She describes how residents were evicted from informal housing into state-provided housing in the urban periphery (Hammar, Citation2015, Citation2017) and emphasizes the importance of a relational approach, one which is sensitive to temporalities and paradoxes, and which recognizes multiple power positions. Hammar reveals how processes involve complex disruptions and new forms of differentiation alongside opportunities for residents, conceptualizing these as “paradoxes of propertied citizenship” (Citation2017). Hammar’s findings parallel many detailed later in this paper however, her starting position, housing politics and trajectories in Zimbabwe, is distinct from those detailed here. The Zimbabwean case evidences eviction, physical destruction, trauma, hunger, hardship, dumping, and extreme poverty (Citation2017, pp. 89–91), processes which quite rightly point to overt displacement. These processes are partly evident in the cases detailed below, but they do not represent the generic experiences of relocated residents in these South African and Ethiopian cases. Analyzing contradictory outcomes is also discussed by Di Nunzio (Citation2019) in an analysis of urban renewal, peripheral housing developments and urban infrastructure in Addis Ababa. He calls for an “analytical distinction between material gains and diffused benefits … it is only the actual delivery of direct material gains that can make the difference in triggering trajectories of social improvement and emancipation” (Citation2019, p. 392). Di Nunzio’s work challenges a more simplistic reading of positives, and places timing and temporality center stage. This paper agrees with this critique but notes that unknown temporalities of change blur evaluations of “benefits”, and weighing up impacts on identity, privacy, affordability, and safety are not at all easy. The mix of outcomes is not easily reducible, although the economic costs to the urban poor are often directly evident as this paper goes on to illustrate. Beier et al.’s edited 2022 collection examines the “inextricability” of the processes of displacement, relocation and reinstallation (Citation2022, p. 2) in the global South. Using the term “resettlement” to capture this set of relationships, they draw on a lived experience approach to call for a mid- or long-term perspective. Their definition of resettlement centers on recognizing the duality of processes, including loss/gain and destruction/production, but displacement is always fundamental (Citation2022, p. 5). Their work emphasizes temporality noting that “resettlement does not necessarily mean the end of (constrained) mobilities” (Citation2022, p. 6). Critical questions of temporality are evident in other scholarship including Sakizlioğlu’s (Citation2014) work critiquing urban renewal processes in Turkey. Temporalities associated with the loss of community and home, and displacement threats are identified and Sakizlioğlu argues that existing studies of displacement ignore the impacts of displacement before actual relocation occurs, claiming that this “socio-spatial phenomenon [is reduced] into a spatial one” (Citation2014, p. 208 after Davidson, Citation2008, p. 225). Similarly, Hirsh et al. (Citation2020) note temporality as key to understanding displacement, describing a time frame from initial decision, to notifying residents, to eviction (Citation2020, p. 399). Our paper extends these arguments of temporality noting that a disruptive re-placement lens recognizes that temporalities are associated with all elements including experiences of living in relocation sites after resettlement (see Wang, Citation2020 and Beier et al., Citation2022 for a similar analysis).

Finally, a concern for the politics of displacement in theorizations of gentrification is evidenced in various heated debates (see Slater, Citation2010; Hamnett, Citation2010 for example) as well as through scholar-activist engagements in resistance practices (Lees & Ferreri, Citation2016) illustrating one of the ways in which displacement scholarship works to challenge urban decision making. The criticality of debate is commonly under scrutiny often from a political-economy perspective. Bernt and Holm argue that theories of displacement have been displaced as an intellectual or political concept (Bernt & Holm, Citation2009, p. 322), and replaced by work that is more politically neutral, and which takes the “neighborhood as scenery” using ethnographic methods (Bernt & Holm, Citation2009, p. 320). Explicitly critical, their work challenges research that neglects the wider politics of displacement in a broader context of state-private sector interests in urban development and change, particularly those driven by a neoliberal agenda. While in agreement with this position, this paper argues that the everyday viewed through ethnographic or qualitative methods can deliver political readings of urban change and relocation while simultaneously privileging a focus on the paradoxical outcomes of relocation for residents. Furthermore, as noted by Parnell and Robinson (Citation2012) critiques of neoliberalism are not sufficient to understand urban processes in many global South contexts.

The search for a critical approach to analyses of resettlement is also the subject of Rogers and Wilmsen’s (Citation2020) insightful work. Although displacement and resettlement are different but related processes, consideration of debates on resettlement is relevant here because of the state-directed nature of the movement, and control over development programs. Rogers and Wilmsen define resettlement as “a government program with multiple logics, one that seeks to render people and space more governable” (Citation2020, p. 3) similar to D.I.Ds mentioned earlier within Hirsh et al’s framing. Rogers and Wilmsen’s work mainly references the development of large dam projects, etc., which enforce extensive resettlement. They criticize mainstream approaches to resettlement that commonly seek to understand and seek solutions to the challenges that arise from resettlement, arguing they tend to “normalise resettlement” (p. 4). Drawing on political-economic and Foucauldian ideas, in contrast, they reveal how these critical approaches instead focus attention on the “key drivers and modalities of land dispossession and resettlement” (p. 6) and questions relating to “how a problem is defined for which resettlement is the solution … and the means through which governable subjects and spaces are produced” (Citation2020, p. 6). They propose reading these two intellectual approaches as complementary arguing that the former encourages us to ask about “the why of resettlement”, while the latter “the how of resettlement” (Citation2020, p. 8). Rogers and Wilmsen’s approach is productive, but as the subsequent section argues, these critical framings are less easily able to address the lived experiences of government-directed developments that at one level seek to (and for some, do) directly benefit those who are relocated through a wider developmental or welfarist agenda, while also fulfilling wider state /private sector ambitions over property rights, land value, profit generation and governability.

Having reviewed literature on the developmental state, displacement, and the politics or criticality of displacement, an alternative framing is clearly required to make sense of contradictory outcomes of state-directed housing relocations through a lived experience lens. The paper turns now to the idea of “disruptive re-placement” to achieve this aim.

Disruptive re-placement?

Much state-directed housing change can be captured by the term displacement and there is ample empirical evidence of different histories of displacement in South Africa and Ethiopia. In the South African context, wars, colonization, and subsequent Apartheid governments’ mass forced removals program saw thousands of black residents violently moved from cities, rural sites and farms into relocation settlements, usually located within the artificially defined homelands. More recently, exercises in state-directed eradication of informal housing and its residents have occurred in pursuit of the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) goal of slum eradication (Huchzermeyer, Citation2010), alongside the privileging of private property claims, and concerns about health. Within Ethiopia’s recent history, significant displacement arose during the 1998 war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, when civilians caught in the conflict fled their homes, and both countries deported citizens. Over the past decade, development-induced resettlement programs, including the building of dams and irrigation projects, etc. have contributed to substantial state-controlled displacement causing insecurity, conflict, and environmental degradation (Watson, Citation2011), and Tsegaye’s article details the political nature of displacing farmers for housing developments in Addis Ababa (Citation2021). There has been a recent rise in conflict-induced displacement following a period of relative calm including events in the northern regions of Ethiopia in 2021–2022. Ethnic conflict, conflict over land and urban development, and flooding have produced displacement (IDMC, Citation2020). Although these varying processes are in practice more complex than outlined here, in general, they typify aggressive action, limited engagement, destruction of property, removal from place of habitation and disconnection from social links as well as key services. In most cases, these processes have resulted in the production of sterile, fragile, poorly located, temporary and emergency accommodation, low-quality housing or further informal living.

However, not all movement advanced by the governments of Ethiopia and South Africa, particularly under the guise of their housing programs, is captured by the narrative of displacement. Much (although certainly not all) movement into state housing is voluntary and in the case of South Africa it forms a popular electoral promise, rather than forced and involuntary. Displacement proves too blunt a descriptor of developmental states’ efforts to implement a significant social housing program. Yet appropriate descriptors capturing these movements are limited. Although both countries’ housing programs have been heavily criticized, they are feted internationally, by UN Habitat, as examples of good practice (Ejigu, Citation2012; Huchzermeyer, Citation2011). Clearly, the work of critical researchers cited above, including the authors of this paper, find substantial fault with these programs, including noting the displacement effects of farmers and the urban poor for example in Addis Ababa. However, there is remarkable variability of outcomes and describing recipients of state housing as displaced or resettled does not do adequate intellectual work to understand the contingent forces, current and future experiences of everyday lives.

Analytically, and in terms of the processes focused on in this paper, the term displacement privileges the “forced” movement from place A, but commonly articulates weakly the qualities of place B, beyond a static description of lack. Additionally, there is a tendency to focus on the place of destruction’s resistive practices, rather than processes of rebuilding (Wang, Citation2020, p. 3) or reinstallation (Beier et al., Citation2022). Place B is imagined as something “not here”, a non-place. Simultaneously, displacement can evoke a romanticized vision of the qualities of Place A, imbued with security, community, vibrancy, economic possibility and access. Such advantages can be evident. Residents residing in downtown Addis Ababa had easy access to markets and community. But frequently the challenges of Place A are poorly articulated in displacement arguments. Unsatisfactory services, housing, insecure tenure, and lack of privacy often troubled residents experiencing relocation, and in some cases Place A proved more vulnerable to crime. Finally, remaining in Place A may also produce challenges for residents who are not relocated (Wang, Citation2020). Recognition of the impacts of Place A (its history, qualities, possibilities) on the experiences of Place B, demands a relational approach to interpreting urban movement (as noted by Hammar, Citation2017). This paper is inspired by McFarlane’s (Citation2020) use of Massey’s conceptualization of space to articulate his relational framing of de/re-densification: viewing space as “first, composed through inter-relations of near and far, second, as a contemporaneous plurality of co-existing trajectories, and third as always under construction, a “simultaneity of stories-so-far”” (McFarlane, Citation2020, p. 318 after Massey, Citation2005, p. 9). He proposes bringing “multiple space-times within and beyond a given site” into relation (McFarlane, Citation2020, p. 318). These varied approaches to relationality are woven through the subsequent analysis.

Finally, the descriptor “displacement” heralds an outcome, namely, that of being displaced, describing in essence a largely static urban condition. Noting the idea of space as “always under construction” outlined above, the term “displaced” risks under-emphasizing how residents’ experiences in relation to the places they have left, or moved to, change over time, and how places change (become better or worse) usually in relation to wider processes of economic and political change. Displacement does not commonly address how relative location further shifts as patterns of urban densification or expansion unfold and fragmented sites become connected or further marginalized. It does not necessarily capture how connections at multiple scales deepen, collapse or transition through varying processes of change. Wang (Citation2020, p. 7) similarly uses the term post-displacement to question the “predetermined idea that displacement is the worst and ultimate outcome of urban redevelopment”.

Alongside these limitations of the term “displacement”, the term “resettlement” similarly describes a direction of travel but lacks analytical purchase and criticality by assuming the outcome is one of “settlement” or to be settled (although see Beier et al. for a productive reframing of this term, as outlined earlier). This can leave uninterrogated the significance of the event and outcome. The interpretation of movement is again one of static finality. Work addressing movements within cities provoked by the acquisition of state housing counters these characteristics of the term “resettlement”. As such moves may accompany or be followed by multiple “informal” movements by residents (Beier et al., Citation2022, p. 6), due to the resale of state housing where house prices are rising and assets are limited (Lemanski, Citation2014) evident also in Addis Ababa as cash-strapped owners sell or rent out state housing to overcome prohibitive costs (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017, p. 34). Unaffordability may preclude permanent residence of new housing, or for reasons tied to employment or access to services, residents may sleep elsewhere in the city on a temporary basis, returning to their resettlement home on occasion (see Charlton, Citation2018).

To overcome the limitations of the terms displacement and resettlement in capturing the dynamic nature of state-directed (developmental) movement, this paper proposes the term disruptive re-placement. This articulates damaging, trouble-inducing consequences of relocation, while accommodating the potential for said consequences reducing in significance over time. Importantly it also signals that damage may prove injurious or irreversible. Disruptive is a stretchy adjective, thus “injurious” is employed alongside the more recoverable “disruption” to critically articulate continuum ends. Implicit is that state-directed movement without disruption is not evident. Disruptive re-placement also connotes processes of change (both in terms of location and the experiences thereof) are alive and ongoing, that their stories are incomplete. This is indicated by the active qualifier “disruptive”. The idea of re-placement refers to the movement of residents, from one to another place, but symbolically indicates that the experience of being in place, can be re-found or re-created. Moved residents may (or may not) ultimately feel “in place” in their new location. Re-placement signifies the directives of powerful external agents, in this case the state, managing and controlling the terms of movement, undermining, but not removing, the power and agency of residents being moved. The narratives of movement under examination in this paper refer not to the replacement of one set of residents by another, although that is an important focus for displacement studies. Many, but not all the case-study sites were greenfield and brownfield, although historic displacement of small-scale farmers did occur in Addis Ababa to make way for housing. Rather, here the focus is on the replacement of one located home for another. Combined, these readings of re-placement, facilitate recognition of the contradictory outcomes of movement as a function of state-directed developmental interventions.

This paper argues that the concept “disruptive re-placement” provides five distinct analytical contributions which speak to the various issues raised in the review of related literature outlined above. The contributions are the capacity to account for the complex lived experiences and practices of residents; a nuanced and contextualized critical evaluation of places of origin, destination or elsewhere; recognition of the relationality of place experiences; an account of the dynamism of urban change; and an ability to label varied experiences and processes through a term that is conceptually flexible, but politically significant. Before turning to an empirically informed analysis of “disruptive re-placement” in the context of three cases in South Africa and Ethiopia, the methodological approach is detailed, along with an overview of the systems of state housing in both country contexts, and summary descriptions of the three case study areas used in this paper.

Methodological approach: learning from lived experiences

The paper draws on data from mixed methods research originally conducted in seven cases – analyzing changing urban peripheries across three African city regions, namely, Addis Ababa, Gauteng and the municipality of eThekwini (in Ethiopia and South Africa respectively) (see Meth et al., Citation2021). The emphasis was on the lived experiences of residents, including many who had relocated to these areas. Between 2017 and 2018, nearly 50 diaries and interviews along with auto-photography were obtained from residents living in each case area. These were accompanied by interviews with key informants including government representatives, community leadership and business leaders. Additionally, 200 surveys were conducted in each of the cases, assessing the quality of life issues, changing urban services and infrastructure alongside residents’ housing trajectories and livelihood characteristics. Survey data inform some of the qualitative findings discussed below. Data were collected in the local languages of isiZulu, Sotho and Amharic, and transcribed and translated into English by authors Buthelezi, Masikane and Belihu. Analysis was conducted collaboratively and thematically. All cases were multimodal, variously incorporating different types of housing forms, including informal settlements, state-provided housing (evident in all seven cases), high-end middle-class housing and some lower middle income mortgaged housing. Details on the cases and methodology can be found in other publications (see Meth, Goodfellow et al., Citation2021; Meth, Todes et al., Citation2021). Here findings from three areas of state housing are used, evident within three of these seven cases, namely, Hammond’s Farm in Durban (located in the eThekwini municipality), Lufhereng in Johannesburg (located within Gauteng) and Tulu Dimtu in Addis Ababa to illustrate the wider arguments developed herein. The case choice for this paper is practically and analytically derived, representing each city-region under analysis, with varying politics, geographies and economies. In addition, the cases reveal distinct elements of relocation germane to the arguments advanced below. This includes evidence of severe dislocation, movement nearer to an urban core and differences in the integration of urban services with housing delivery.

The Ethiopian and South African housing programs

The Ethiopian Integrated Housing Development Programme (IHDP) was launched in 2004 aiming to provide low and medium income privately owned housing in the form of multi-storey condominiums. Delivering around 171 000 units by 2010, although less than the planned 400 000, the program is regarded by some as an example of success (Ejigu, Citation2012; UN Habitat, Citation2011). Across Ethiopia, the condominiums are built on cleared land previously occupied by informal housing, small-scale farmers, or on brownfield or greenfield sites. Within Addis Ababa, much of the early production was on inner-city well-located land, but increasingly building has occurred on the urban peripheries (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017). Groups of buildings usually share a separate jointly managed communal building, to facilitate traditional practices of animal slaughter, large-scale cooking, and laundry. Around 10% of each condominium site is allocated to ground floor commercial units (UN Habitat, Citation2011, p. 22). Structures are standardized, with housing units consisting of studios, one, two or three bed-roomed apartments. A two-bed apartment is around 30–45 m². Each unit contains a bathroom and kitchen with water and electricity (although not all have benefitted from completed connections). The cost of the housing program was initially planned to be entirely recoverable, through payments made by beneficiaries to cover the building costs. Smaller units are cross-subsidised by larger units, where the latter are charged at more than their construction costs and the former at less. This was intended to support poorer households' access to the apartments (UN Habitat, Citation2011). Allocation occurs through a lottery system to overcome claims of preferential allocation, and 30% of housing is reserved for women. Residents are required to pay initial deposits (between 10% and 40%) for their properties (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017) and then once residing in the properties, to repay their loans with interest over 10–20 years.

From 1994 onwards, South Africa, through its Department of Human Settlements (DHS), has progressed a substantial housing program delivering around 4.7 million privately owned housing opportunities to residents (DHS, Citation2019). It is a key welfare intervention, aimed at redressing inequities of apartheid, reducing poverty and ridding cities of informal housing. Eligibility criteria for this housing, including maximum household monthly earnings of ZAR3500 (GroundUp, Citation2019), being South African nationals, among others, are used to determine beneficiary rights to such housing (Tissington, Citation2011). The housing is free at the point of delivery, with payment for municipal rates and services required upon occupation. Labeled “RDP”Footnote1 housing, it commonly consists of a house, plot, and full title, although securing deeds has proved challenging for some. While municipalities have implemented in situ housing development where possible, many beneficiaries were resettled. Affordable greenfield land is commonly located on city peripheries (Turok, Citation2013). Properties were initially small, intended as starter units, but have increased over time and are commonly around 40 m², consisting of two bedroomed units. Housing is often detached, although higher density designs are being trialed. Properties include water and electricity, but these connections are not always viable upon occupation and incur charges.

The three areas of state-directed housing

Hammond’s Farm (HF) is located to the north of Durban, directly south of the airport. A relatively recent development, it contains 1,800 terraced two-storey houses built on greenfield land, serviced with electricity and water. It lacks additional infrastructure including transportation, schools or clinics but benefits from a large supermarket at the main road junction into the settlement. A substantial number of the residents of HF were relocated from Ocean Drive-In (ODI), an informal settlement 17 km further north on the city’s periphery. ODI had dire living conditions (Sutherland & Buthelezi, Citation2013) but its good local linkages to employment was a key advantage. Other residents who moved into HF came from elsewhere in the city, usually from informal settlements or other insecure housing. A large proportion of residents struggle with poor access to employment, and the costs associated with their new housing. The settlement has a relatively high proportion of female-headed households.

Lufhereng is located on the western boundary of the city of Johannesburg, west of Soweto, within Gauteng, the economic powerhouse of South Africa (see Charlton, Citation2017 for a detailed overview). The partly developed settlement is dominated by detached, and some semi-detached state-subsidized housing. Additionally, bonded housing has been built in late 2018 with a view to attracting lower middle-class homeowners. Most recipients of state housing moved from nearby informal settlements from 2014 onwards, with some moving from nearby Soweto where they occupied backyard shacks. Many residents are unemployed. The lack of affordable transportation impacts negatively on residents’ abilities to access work, health services and shopping facilities but the recent development of local schools is a key gain. Lufhereng’s development is controversial as plans to build the settlement flouted agreed planning policy for Johannesburg, which previously described the area as “poorly located” (Charlton, Citation2019) and hence a low priority for investment (Charlton, Citation2017). Its development fulfills the planning agenda of the province of Gauteng (Charlton, Citation2014) which is investing in a mega-projects approach to urban transformation (Ballard & Rubin, Citation2017; Charlton, Citation2017).

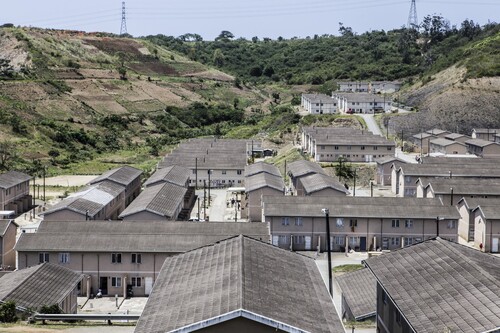

Tulu Dimtu in Addis Ababa is located to the south of the city, far from the city center. Part of the settlement straddles neighboring Oromia state. It is bifurcated by a newly extended motorway traveling south out of Addis Ababa and characterized by various housing typologies. To the west is a large area of cooperative housing, with a smaller pocket of condominium housing, and a relatively older area of housing occupied by residents resettled due to nearby developments (including a prison and university). To the east, the housing is primarily new condominiums (some built on former farmland) with a small section of farmer/informal housing (established by the former communist regime's villagization program). Many of the condominium residents moved from informal housing within inner-city Addis, shared a home with extended families and had limited infrastructure. All condominiums are of the “20/80” finance scheme (i.e. 20% deposit/80% long-term payment). Most are five storey walk-ups with several six to eight-storey apartments located centrally on the eastern side. Also within the eastern side is a small market. Lack of adequate infrastructure and services, including education, transport and medical provisions are affecting residents. South of the Addis Ababa border just beyond Tulu Dimtu along the A1 road and the Addis-Adama Expressway lies a large industrial complex.

Lived experiences of disruptive re-placement

Materialities of planned state-provided formal housing

For residents in all three cases, numerous gains arise from the acquisition of new housing. Movement into new formal housing is commonly their first experience of homeownership. Most moved from informal housing, often where ownership or security of tenure was lacking, and they articulated significant satisfaction over their status as homeowners and the possession of a home. Aside from the significant financial burdens, detailed below, the material gains of shelter, the tenure security and privacy of homeownership were important. Pride and status were key emotional registers evidenced through residents’ lived experiences of their new housing.

I will say my house is a gift from God and a nice house and I feel very happy to have a house because I was staying in a shack. Now even if it’s raining, I’ve got no worries for rain. (NF ♀, Interview, Lufhereng)

That councillor … to me is like the Moses from the bible who help the people of Israel from Egypt to the promised land because he was able to take me from the muddy house to the formal house. (MM, ♂, Diary, Hammond’s Farm)

Truly on my side I see life as good because I’m free [before] … we shared [our house] Now life wasn’t nice you understand when you share a house there isn’t any peace. (EM, ♀, Interview, Lufhereng)

A final feature of state-directed movement through housing programs is the explicit parallel presence (and threat) of trajectories of settlement master planning. Scaled-up planned settlements can provide opportunities for efficient and sustainable design, public space, higher densities, provision of services and integrated development. Lufhereng’s development is distinctively (and self-consciously) more integrated than Hammond’s Farm, with planning interventions ongoing and dynamic, including investment in different housing typologies in the area illustrating important “attention to design” (Charlton, Citation2017, p. 89). In Tulu Dimtu, the provision of community buildings and retail spaces on the ground floor of condominium structures evidence achievements of formal planning, however poor articulation can arise, as in the case of some community buildings:

These units are constructed for purposes such as, slaughtering animals and for times of weddings/funerals and for other everyday activities … don’t have water and electricity and one doesn’t know for what purpose they’re constructed in the first place. The location of these units is also irrational, some are located near the housing units and others are far, implicating design problems. (ME, ♀ Diary Tulu Dimtu)

Following Rogers and Wilmsen’s (Citation2020) argument around how problems and solutions are determined, we must ask what alternatives to state-directed housing could there have been, and how would these have shaped residents’ experiences? In policy terms, re-placement could have occurred through movement into affordable rental units, or more incremental planning approaches (Ejigu, Citation2012) or em-placement (on-site-relocation) through upgrading or rebuilding on original sites, strategies that are not entirely at odds with a developmental state agenda.

Spatialities of disruptive re-placement

New formal housing settlements often possess distinctive spatialities tied to location and extant environmental qualities. These qualities, or experiences thereof are dynamic, transforming over time in positive and negative ways. Peripheral location is a binding yet relative feature across Lufhereng, Tulu Dimtu and Hammond’s Farm and is also experienced relationally by residents, origin dependent. Lufhereng’s residents mainly moved from nearby informal settlements, located a similar distance from the urban core, but which benefitted from good pedestrian access to a nearby shopping mall and employment in neighboring Lenasia. In relative terms, Lufhereng is poorly located. Tulu Dimtu’s substantial distance from central Addis far away from job opportunities with poor transportation links produces distinct peripherality. With different connection roads planned and under construction, promise for the future is evident. Yet Hammond’s Farm’s relatively promising situation near the recently developed economic hub of Gateway/Umhlanga, exemplifying a case of moving towards rather than away from the urban core, for locationally specific reasons has proved detrimental for residents’ access to work and services. Despite these three distinct locational realities, across all cases, residents perceive their location as stuck on the city fringes, impacting their lives in significant ways.

A critical evaluation indicates that the lack of affordable transportation was a contextually particular deficiency in destination locations. Its persistence shapes relocation as injurious rather than simply disruptive producing new inequalities and unliveability, which if untackled points to an unresolvable tension in the framing of disruptive re-placement. State failure, across all three cases, to invest in transportation eroded many of the benefits of what are potentially desirous housing estates. Lufhereng residents, who lacked access to private vehicles, depended on minibus taxis, noted as expensive, dangerous and time consuming. The building of good local schools was a significant advantage in this new settlement, but near-hopeless access to work meant some residents were pushed into unemployment and poverty because of relocation.

Lufhereng is a beautiful place, to me the only problem is just the transportation. (PR, ♂, Interview, Lufhereng)

Relocation to new housing settlements does not have to spell inaccessibility, yet here, and in many other cases, it does. A disruptive re-placement lens facilitates the possibility of overcoming the friction of location through affordable transportation. Charlton cites a city official’s reflections on the potential impacts of improved transport in Johannesburg: “I don’t think we would even notice that people are living on the periphery” (Citation2014, p. 186). Resettlement can be a dynamic process. Strategic and integrated urban planning can facilitate and overcome an initial period of disruption, which eases as transport provisions are resolved. This is a question of planning policy, but also of budget allocation, political willingness, and technical capacity. The lesson, particularly in view of a developmental approach, is not necessarily that people should not be resettled, but when this occurs, without careful, integrated, and inclusive planning, unliveable urban conditions are produced.

New settlements have physical and spatial absences, often taking decades to resolve. Lack of associated “urban” qualities, particularly shops, schools, health care services, alongside the materialities of “incomplete space” (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017, p. 31) are evident. With residents enduring months or years of building contractors working nearby, or with properties half complete, vacant or at risk of illegal occupation. Occupation of retail and residential spaces in Tulu Dimtu’s condominiums varied, while communal structures for cooking and slaughter were unfinished. In Hammond’s Farm, no communal facilities or onsite commercial sites existed. Residents used their small homes for retail and service provision. A centrally located concrete plot remained undeveloped some nine years after settlement occupation. In Lufhereng, the existing site represented a small proportion of the proposed overall development, meaning ongoing building works were a likely feature for some time.

Imperfect build quality and inadequate services varied across cases and between residents. In Tulu Dimtu, erratic and insufficient water supply reduced infrastructure function in vertical structures. Ground floor residents experienced sufficient supply, however those living above depend on manual delivery.

there is a huge problem with water, we only get it once a week which makes our lives difficult. As it is known a life in a condominium is difficult without water. This is because we have toilets inside and if we don’t get water every day the smell is very bad. (074 ♂ Diary, Tulu Dimtu)

Peripheral and/or new settlements do possess various spatial positives in terms of their environmental features, distinct benefits of relocation. Access to nature, fresh air, relative peace and quiet, and opportunities for small-scale subsistence farming are evident. For residents living in previously dense urban contexts, the relative rurality of peripheral locations is an important contrast:

When I moved here from another area, I was very afraid since I felt it was a completely rural area. But I was mistaken, it has a distinct feature. When we leave this condominium site what we see is nature and this creates happiness. (BG10, ♀ Diary, Tulu Dimtu)

Disruptive re-placement as an economic and socio-political process

Relocation into new settlements produces a raft of complex socio-economic consequences, which are largely but not entirely stories of rising financial hardship for those unemployed or on low incomes, discernible through residents’ lived experiences. Seemingly paralleling outcomes evident through a displacement lens, the analysis below uses a disruptive re-placement framing recognizing that the socio-economic contexts of state-managed relocation can be partially distinct in important ways. The terms of homeownership, the presence of welfare infrastructures and active investment in some economic sectors shape outcomes. Furthermore, movement is commonly (but not always) voluntary, and often from informal to more formal contexts, which impacts socio-political relations in multiple ways.

A critical evaluation of the destination sites reveals that in the South African cases where receipt of state housing is free, many residents describe the costs associated with rates and services as prohibitive. In Hammond’s Farm, a growing reliance on food charities and church donations result from rising poverty. Residents have indeed been made poorer by the move. There, and in Lufhereng, the loss of employment opportunities relative to their previous locations underpins significant economic hardship. In Ethiopia’s case of Tulu Dimtu, payment toward the mortgage costs of the condominium apartments proved a significant financial hurdle for most. A relatively high proportion of residents had rented out or sold their homes, presumably unable to afford repayments coupled with other unaffordable services. Experiences of disruptive re-placement are explicitly tied to economic policy interventions with Potts (Citation2020) linking housing affordability directly to income levels. The limits of developmental states are evident in their failure to secure permanent jobs or decent incomes. Turok and Borel-Saladin question the South African government’s prioritizing of housing, in view of exceptional joblessness (Citation2016, p. 397). Residents’ economic outcomes are a function of local and national economic policies, fluctuations in employment, the forms of state welfare and work programs and in the quality of and access to education and training. In Addis Ababa, work in the construction sector was an important but unreliable source of income for several residents, with its variability proving challenging for some. Because the condominium housing scheme and renting are only available to residents with an income, some employed residents experienced their new housing as expensive – with constantly rising prices for tenants – but manageable. In South Africa, dependence on welfare payments (via pensions and child support grants) paved the way for varied experiences, with some residents able to persist in these settlements. Irregular opportunities to work in public works programs facilitated some local income. This grant-dependent resident points to multiple economic and political barriers to employment:

Most people here are not working because they are far from the city. Nowadays, even if you have a good education, you have to know someone and sometimes even if you know someone, you have to bribe someone in that industry to get work. Where do you get money to bribe when you are not working? (NM, ♀ interview, Hammond’s Farm)

Relocation in all three cases, as elsewhere (see Seekings et al., Citation2010) brought significant disruption and destabilization of community networks, neighbor relationships and links, forcing re-crafting of relationships. Yet our study revealed varied experiences. Some HF residents complained about isolation, unfriendliness, and the loss of communal and outdoor ways of socializing. For some in Tulu Dimtu, a life behind closed doors in comparison to a former lively environment of communal living is a point of dislike. But others across all three cases celebrated the opportunities, and joy at forging new networks, and at levels of neighborly interaction. For some, relocation spelled freedom from the constraints of earlier communal living, alongside advantages of relative privacy. Social networks are clearly one form of bond that is severely disrupted, even broken during relocation, but the evidence here is that this is not always irreversible, nor necessarily always negative. For young adults, women particularly, freedom from previous networks can be liberating as they escape the restrictions of more communal living.

Significance of temporality

As with any urban change, the dynamics of change over time are critical to the logics and experiences of resettlement. A modernist linearity where change is necessarily productive and positive is eschewed in this paper. Change can be both positive and negative, evidenced through contextual critical evaluations of each case, and interpreted through the descriptor “disruption”, which suggests possible improvement over time. Cautious employment of this label recognizes it is partial, dependent, contingent, varied and relative. Nor is this label applicable to all forms of state-directed relocation, or even most beneficiary experiences. There is ample research to prove otherwise. Many areas of new state housing across the world, may never improve over time, may never prove viable or sustainable, and may serve to worsen the lives of the urban poor particularly. Indeed, state housing (originally intended to counter poverty) may ultimately provide affordable homes for a rising middle class (Planel & Bridonneau, Citation2017). Similarly, our three cases reveal how particular post-resettlement temporalities are often ones of worsening realities, alongside small improvements. Water access in Tulu Dimtu, as an exemplar, shows negligible improvement, and is likely to worsen as the settlement grows in scale and population. Here, dynamism is evidenced by infrastructural collapse. However, the gradual rise in retail outlets and the habitation of vacant apartments is improving the liveability of the settlement (see ).

A focus on the temporalities of relocation is critical however because urban analysis must capture the dynamism of the urban condition while advancing evaluation of the politics of these produced temporalities. Urban experimentation and planned solutions can be important, but interventions which actively worsen residents’ lives are not acceptable. Here two dimensions of temporality are considered, the first relates to the scale or extent of time over which change occurs, and the second to ideas about the future.

Regarding temporalities of scale and extent, the concept of disruptive re-placement suggests the production of inconvenience and difficulties tied to relocation. Here analyses of the lived experiences suggest the delays in critical provisions are beyond disruptive and are instead commonly injurious. In South Africa, a critical evaluation of the close ties between the ambitions and ideologies of the governing ANC government and the state housing program implicates the state in the speed and nature of delivery. In Hammond’s Farm, the failure to provide local schools or resolve children’s journeys to nearby schools is deeply disruptive for families although their complaints have resulted in the provision of traffic lights to aid pedestrian mobility. The efforts in Lufhereng to design the settlement in an integrated manner have on some levels proved successful. Tarred roads, better building quality and the provision of decent schools have proved critical. For new residents, the simultaneity of movement into a relatively serviced settlement is important, as is the promise of economic investment alongside private sector housing development. Yet residents wait for a host of other critical elements: access to work and affordable transportation being key. The delays of both fundamentally undermine the viability of this site (Charlton, Citation2014, Citation2017). In Ethiopia, for residents of Tulu Dimtu, the twin lack of transportation and water are utterly injurious and residents’ capacities to cope with these realities over time will prove decisive in who can afford to reside in this settlement while these features are lacking. In essence, poor vulnerable residents suffer the consequences of slow processes of urban development.

Critical policy questions pertaining to the temporalities of a developmental agenda arise. For how long can conditions be endured by residents, and how can these be avoided altogether? Recognizing that urbanization has historically been forged through frontier practices that are predicated on political gain, disruption, loss, lawlessness (McGregor & Chatiza, Citation2019), danger and scarcity, what extents of temporal disruptions are acceptable, reasonable and avoidable? Furthermore, when these are state-produced disruptions, over what time period, if any, are injurious impacts ever acceptable? Urban spaces are dynamic. Once-peripheral locations can become desirably located. A planner involved asked “Who knows what might happen to somewhere like Lufhereng?” (cited in Charlton, Citation2014, p. 186). These deeply political questions, demand acknowledgment of the often-limited power of the relocating residents to challenge and contest the imposition of injurious conditions. They also demand recognition of the role of state politics, including party politics and conflicts across scales of governance (Charlton, Citation2014) in the production of these settlements (McGregor & Chatiza, Citation2019). Urban planners and governance figures need better agreement and discussion about the temporalities of relocation. What are they, how do they vary, what impacts do the long- or medium-term absences of facilities have on residents over time? How honest and realistic are narratives about new settlements (advertising boards, policy ambitions) in relation to the time taken for key changes to occur, and how does this stack up alongside residents’ capabilities to cope with conditions as they change? What are the politics of medium to long-term disruptions associated with relocation?

The future and its role in planning, imagination and political promise is the second key dimension of temporalities of disruptive re-placement. In all three cases, residents were excited, apprehensive and anxious about both the move into their new homes and settlements and living in these new spaces. These emotions were tied to their expectations and experiences of relative material improvements in the quality of shelter and hopes for their future. For some this evidenced sheer optimism, for others it was a function of their relational knowledge of comparable settlements, lived experience of other forms of urban living, desperation, or expectations tied to state communication and depiction of the qualities of these settlements. Their lived experiences of these future imaginings evidence strong emotion:

I always knew Lufhereng was going to be a beautiful place right. It’s a place where it’s inspiring it gives you hope to live for the next day. (PR, ♂, Interview, Lufhereng)

This area after a year or two would change a lot and become so vibrant that, I think, a lot of people would want to move here. Because the general feature of the area is great. (BG ♀ 10 Diary, Tulu Dimtu)

the children love the word flat … They do not want to move. (ZN ♂ Interview, Hammond’s Farm)

“Oh Tulu Dimtu, one day I think it will change; May that day be soon!!!” (TD030 ♂, Diary, Tulu Dimtu)

Disruptive re-placement and a just urban agenda

Arguing that displacement can prove too narrow in capturing contradictory outcomes for relocated residents, particularly in contexts where housing provision is driven by a developmental state pursuing a welfarist agenda, this paper calls for extended language to capture urban movement for particular residents, tied to state housing programs. This objective parallels Wang’s calls for work going “beyond the lens of displacement” (Citation2020, p. 1). The paper’s aim was not to advance a critique of said programs from either a political-economic or Foucauldian perspective (Rogers & Wilmsen, Citation2020) although this is certainly a valid exercise. But it does attempt to understand the why and how of resettlement (Rogers & Wilmsen, Citation2020) from the perspectives of residents in relation to state policy. Employing the term “disruptive re-placement”, the paper identifies five distinct contributions of the framing, offering a lived experience analysis, embedded in contextualized critical evaluations of all locations, which is relational, can account for the dynamism of urban change, and is sensitive to varied experiences. These analytical elements of the disruptive re-placement frame an empirically grounded examination of two cases in South Africa, Hammond’s Farm and Lufhereng, and one in Ethiopia, Tulu Dimtu – all sites of relocation into state-directed housing. Privileging the experiences of residents, the substantive arguments traced how planned settlements, their spatialities and socio-economic realities articulated with temporalities of relocation to produce contradictory outcomes, best understood through the term disruptive re-placement.

An ongoing tension between disruptive and injurious impacts of disruptive re-placement bleeds through the analysis, with the paper seeking no comforting resolution. Instead, the argument recognizes that outcomes and experiences of relocation are contingent, varied, contextual, relational and dynamic. However, the production of disruption and injury, and the temporalities of this are firmly located at the feet of developmental states. Provocations regarding housing, planning and employment policy are inserted throughout the analysis, noting failings to integrate developments, or to ensure affordability through meaningful employment. Without these, peripheral locations are likely to be unlivable for most urban poor. The politics of temporality, particularly how long residents should endure disruptive or injurious realities, and who this impacts specifically, were identified as critical questions for government and planners. These are key concerns underpinning efforts to advance a just urban agenda and local communities need to be capacitated to hold the state accountable to ensure appropriate interventions, and in a timely manner. To understand the fluid nature of change over time, whether improvements or deteriorations, qualitative work which establishes complex histories and narratives of change is needed, ideally foregrounding a longitudinal approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the empirical and intellectual contributions of researchers involved in the wider project including Tatenda Mukwedeya, Zhengli Huang, Jennifer Houghton, Yohana Eyob Teffera, Messeret Kassahun, Israel Tesfu, Alison Todes, Sarah Charlton and Tom Goodfellow. We also acknowledge the analysis work carried out by Spencer Robinson and Isabella Langton Kendall. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers who provided insightful critical guidance which informed revisions to this paper. We are grateful to the residents of Lufhereng, Hammond’s Farm and Tulu Dimtu for sharing their experiences with us, helping us to understand the complexities of relocation in African cities. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence* to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 RDP stands for Reconstruction and Development Programme.

References

- Ballard, R., & Rubin, M. (2017). A ‘marshall plan’ for human settlements: How megaprojects became South Africa's housing policy. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 95(1), 1–31.

- Beier, R., Spire, A., & Bridonneau, M. (2022). Urban resettlements in the global south. Routledge.

- Bernt, M., & Holm, A. (2009). Is it, or is not? The conceptualisation of gentrification and displacement and its political implications in the case of Berlin-prenzlauer berg. City, 13(2–3), 312–324.

- Buire, C. (2014). The dream and the ordinary: An ethnographic investigation of suburbanisation in Luanda. African Studies, 73(2), 290–312.

- Caldeira, T. (2017). Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global south. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), 3–20.

- Charlton, S. (2014). Public housing in Johannesburg. In A. Todes, C. Wray, G. Gotz, & P. Harrison (Eds.), Johannesburg after apartheid: Changing space, changing city (pp. 176–193). Wits University Press.

- Charlton, S. (2017). Poverty, subsidised housing and Lufhereng as a prototype megaproject in Gauteng. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 95(1), 85–110.

- Charlton, S. (2018). Spanning the spectrum: Infrastructural experiences in South Africa’s state housing programme. IDPR, 40(2), 97–120.

- Charlton, S. (2019, June 11–14). Providing on the peripheries: Exploring multiple logics, drivers and consequences of housing delivery on African urban edges. Conference paper presented at ECAS, Edinburgh. https://ecasconference.org/2019/downloads/ecas2019_programme.pdf

- Chiu-Shee, C., & Zheng, S. (2019). A burden or a tool? Rationalizing public housing provision in Chinese cities. Housing Studies, 36(4), 500–543.

- Coelho, K. (2016). Tenements, ghettos, or neighbourhoods? Outcomes of slum clearance interventions in Chennai. Review of Development and Change, XXI(2), 111–136.

- Davidson, M. (2008). Spoiled mixture: Where does state-led ‘positive’ gentrification end? Urban Studies, 45, 2385–2405.

- De Pacheco Melo, V. (2017). Top-down low-cost housing supply since the mid-1990s in Maputo: Bottom-up responses and spatial consequences. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 93(1), 41–67.

- DHS. (2019). Annual Reports, 2018/2019. Department of Human Settlements, Republic of South Africa. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from http://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/u16/2018-19%20DHS_ANNUAL%20REPORT_WEB.pdf

- Di Nunzio, M. (2019). Not my job? Architecture, responsibility, and justice in a booming African metropolis. Anthropological Quarterly, 92(2), 375–401.

- Durand-Lasserve, A. (2007). Market-driven eviction processes in developing country cities: The cases of Kigali in Rwanda and Phnom Penh in Cambodia. Global Urban Development, 3(1), 1–14.

- Ejigu, A. (2012). Socio-spatial tensions and interactions: An ethnography of the condominium housing of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. In M. Robertson (Ed.), Sustainable cities: Local solutions in the Global South (pp. 97–112). Practical Action Publishing Limited, and the International Development Centre.

- GroundUp. (2019). Everything you need to know about government housing. Site updated 21 May 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.groundup.org.za/article/everything-you-need-know-about-government-housing/

- Hammar, A. (2015). Displacement economies: Paradoxes of crisis and creativity in Africa. In A. Hammar (Ed.), Displacement economies (pp. 3–28). Zed Books.

- Hammar, A. (2017, December). Urban displacement and resettlement in Zimbabwe: The paradoxes of propertied citizenship, African Studies association. African Studies Review, 60(3), 81–104.

- Hamnett, C. (2010). ‘I am critical. You are mainstream’: A response to slater. City, 14(1–2), 180–186.

- Hirsh, H., Eizenberg, E., & Jabareen, Y. (2020). A new conceptual framework for understanding displacement: Bridging the gaps in displacement literature between the global South and the global north. Journal of Planning Literature, 35(4), 391–407.

- Huchzermeyer, M. (2010). Pounding at the tip of the iceberg: The dominant politics of informal settlement eradication in South Africa. Politikon, 37(1), 129–148.

- Huchzermeyer, M. (2011). Cities with ‘slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. University of Cape Town Press.

- IDMC. (2020). Internal displacement monitoring centre: Ethiopia. Retrieved February 4, 2020, from https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/ethiopia

- Lees, L., & Ferreri, M. (2016). Resisting gentrification on its final frontiers: Learning from the heygate estate in London (1974–2013). Cities, 57, 14–24.

- Lemanski, C. (2009). Augmented informality: South Africa’s backyard dwellings as a by-product of formal housing policies. Habitat International, 33(4), 472–484.

- Lemanski, C. (2014). Hybrid gentrification in South Africa: Theorising across southern and northern cities. Urban Studies, 51(14), 2943–2960.

- Lemanski, C., Charlton, C., & Meth, P. (2017). Living in state housing: Expectations, contradictions and consequences. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 93(1), 1–12.

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.

- McFarlane, C. (2020). De/re-densification. City, 24(1–2), 314–324.

- McGregor, J., & Chatiza, K. (2019). Frontiers of urban control: Lawlessness on the city edge and forms of clientalist statecraft in Zimbabwe. Antipode, 51(5), 1554–1580.

- Meth, P. (2020). ‘Marginalised-formalisation’: An analysis of the in/formal binary through shifting policy and everyday experiences of ‘poor’ housing in South Africa. IDPR, 42(2), 139–164.

- Meth, P., Goodfellow, T., Todes, A., & Charlton, S. (2021). Conceptualizing African urban peripheries. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45(6), 985–1007.

- Meth, P., Todes, A., Charlton, S., Mukwedeya, T., Houghton, J., Goodfellow, T., Belihu, M. S., Huang, Z., Asafo, D., Buthelezi, S., & Masikane, F. (2021). At the city edge: Situating peripheries research in South Africa and Ethiopia. In M. Keith & A. De Souza Santos (Eds.), African cities and collaborative futures: Urban platforms and metropolitan logistics (pp. 30–52). Manchester University Press. https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526155351/9781526155351.00008.xml

- Mosselson, A. (2017). Caught between the market and transformation: Urban regeneration and the provision of low-income housing in inner-city Johannesburg. In P. Smets & P. Watt (Eds.), Urban renewal and social housing, A cross-national perspective (pp. 351–390). Emerald Books.

- Nikuze, A., Sliuzas, R., Flacke, J., & van Maarseveen, M. (2019). Livelihood impacts of displacement and resettlement on informal households - A case study from Kigali, Rwanda. Habitat International, 86, 38–47.

- Nowicki, M. (2020). ‘Housing is a human right. Here to stay, here to fight’: Resisting housing displacement through gendered, legal, and tenured activism. In P. Adey, J. C. Bowstead, K. Brickell, V. Desai, M. Dolton, A. Pinkerton, & A. Siddiqi (Eds.), Handbook of displacement (pp. 725–738). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parnell, S., & Robinson, J. (2012). (Re)theorizing cities from the global south: Looking beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geography, 33(4), 593–617.

- Patel, K. (2016). Encountering the state through legal tenure security: Perspectives from a low income resettlement scheme in urban India. Land Use Policy, 58, 102–113.

- Planel, S., & Bridonneau, M. (2017). (Re)making politics in a new urban Ethiopia: An empirical reading of the right to the city in Addis Ababa’s condominiums. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 11(1), 24–45.

- Potts, D. (2020). Broken cities: Inside the global housing crisis. Zed Books.

- Rogers, S., & Wilmsen, B. (2020). Towards a critical geography of resettlement. Progress in Human Geography, 44(2), 256–275.

- Sakizlioğlu, B. (2014). Inserting temporality into the analysis of displacement: Living under the threat of displacement. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 105(2), 206–220.

- Seekings, J., Jooste, T., Muyeba, S., Coqui, M., & Russell, M. (2010). The social consequences of establishing ‘mixed’ neighborhoods: Does the mechanism for selecting beneficiaries for low-income housing projects affect the quality of the ensuing ‘community’ and the likelihood of violent conflict? Report for the Department of Local Government And Housing, Provincial Government of the Western Cape, Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town.

- Slater, T. (2010). Still missing marcuse: Hamnett’s foggy analysis in London town. City, 14(1–2), 170–179.

- Sutherland, C., & Buthelezi, S. (2013). Settlement case 2: Ocean drive in an informal settlement. In E. Braathen (Ed.), Addressing sub-standard settlements WP3 settlement fieldwork report (pp. 75–80). Retrieved January 19, 2016, from http://www.chance2sustain.eu/fileadmin/Website/Dokumente/Dokumente/Publications/pub_2013/C2S_FR_No02_WP3__Addressing_Sub-Standard_Settlements.pdf

- Tissington, K. (2011). A resource guide to housing in South Africa 1994-2010: Legislation, Policy, Programmes and Practice. SERI Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa.

- Tsegaye, Y. (2021). Pushing boundaries in Ethiopia’s contested capital. Ethiopia Insight. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2021/06/21/pushing-boundaries-in-ethiopias-contested-capital/

- Turok, I. (2013). Transforming South Africa's divided cities: Can devolution help? International Planning Studies, 18(2), 168–187.

- Turok, I., & Borel-Saladin, J. (2016). Backyard shacks, informality and the urban housing crisis in South Africa: Stopgap or prototype solution? Housing Studies, 31(4), 384–409.

- UN Habitat. (2011). Condominium Housing in Ethiopia: The Integrated Housing Development Programme, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT).

- Venter, A., Marais, L., Hoekstra, J., & Cloete, J. (2015). Reinterpreting South African housing policy through state welfare theory. Housing Theory and Society, 32(3), 346–366.

- Wang, Z. (2020). Beyond displacement – exploring alternative social impacts of urban redevelopment. Urban Geography, 41(5), 703–712.

- Watson, E. (2011). Book Review: Moving people in Ethiopia: Development, displacement and the state edited by A. Pankhurst and F. Piguet Woodbridge: James Currey, 2009. Journal of Modern African Studies, 49(1), 180–181.

- Yntiso, G. (2008). Urban development and displacement in Addis Ababa: The impact of resettlement projects on low-income households. Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, 24(2), 53–77.

- Zhou, J., & Ronald, R. (2017). Housing and welfare regimes: Examining the changing role of public housing in China. Housing Theory and Society, 34(3), 253–276.