Abstract

Background: Hypertension is an important cardiovascular risk factor with potentially harmful consequences. Home blood pressure monitoring is a promising method for following the effect of hypertension treatment. The use of technology-enabled care and increased patient involvement might contribute to more effective treatment methods. However, more knowledge is needed to explain the motivations and consequences of patients engaging in what has been called ‘do-it-yourself healthcare’. Aim: This study aimed to investigate patients’ experiences of home blood pressure monitoring through the theoretical frame of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT 2). Methods: The study had a qualitative design, with focus group interviews using the web-based platform Zoom. The data were analysed using qualitative deductive content analysis, inspired by Graneheim and Lundman. Results: The results are presented using the seven theoretical constructs of UTAUT 2: Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social Influence, Facilitating Conditions, Hedonistic Motivation, Price Value and Habit. We found one overarching theme ‒ ‘It’s all about the feeling of security’. The patients were influenced by relatives or healthcare personnel and experienced the home monitoring process as being easy to conduct. The patients emphasised that the quality of the blood pressure monitor was more important than the price. Patients reported home monitoring of blood pressure as a feasible method to follow-up care of their hypertension. Discussion: This study indicates that among motivated patients, home blood pressure measurement entails minimal effort, increases security, and leads to better communication about blood pressure between healthcare personnel and patients.

KEY POINTS

Self-monitoring of hypertension is an increasingly common method and may increase measurement accuracy and patient involvement.

Through the theoretical lens of the UTAUT2, home blood pressure monitoring seems to increase patients´ feeling of security.

The respondents did not report negative experiences and might have been more prone to use technology-enabled care.

Home blood pressure monitoring seems to be easily adopted by motivated patients with an interest in self-monitoring their disease.

Introduction

High blood pressure (BP) is classified as one of the leading mortality risk factors worldwide [Citation1]. Furthermore, healthcare services are facing challenges due to the increased proportion of elderly people and individuals with long-lasting diseases [Citation2]. Worldwide, overburdened healthcare services with a shortage of healthcare professionals have emphasised the need for more efficient services that could lead to a paradigm shift in healthcare towards person-centredness [Citation3] and patient participation [Citation4].

One solution to the many challenges may be remote healthcare services, i.e. via technology-enabled care, but patient participation must be considered [Citation5]. Remote monitoring, where patients outside conventional clinical settings have been monitored with the help of technology-enabled care, has been described as a solution for increased access to care and decreased healthcare delivery costs [Citation6–8]. There are promising results regarding the effectiveness of home monitoring of BP [Citation9]. It seems beneficial for all patients since the measures are comparable or even more precise than the BP measurements taken in the clinic [Citation10,Citation11]. Research on patients’ experiences and expectations of remote monitoring for chronic disease showed that it could improve self-management and shared decision-making [Citation12].

In addition, home BP monitoring may lower blood pressure through indirect effects such as reminding patients to take their medication, making more healthy choices in everyday life [Citation9,Citation13] and reducing the impact of white coat syndrome [Citation14]. In England, over 220,000 BP monitors have been distributed to patients so they could report their blood pressure for review by their GP [Citation15]. However, it has been shown that compliance decreased over time, even if patients initially engaged in interactive telehealth interventions to monitor and manage high BP [Citation16]. Inadequate knowledge about the benefits of lowering blood pressure, limited access to monitors or increased stress levels due to a constant reminder of illness identity or uncertainties about interpreting the results are some of the factors that might limit the broader use of blood pressure monitoring [Citation17]. Therefore, to encourage a broad implementation of home monitoring, a more complex model of understanding is needed to explain the patient’s acceptance, motivations for and consequences of engaging in what has been called ‘do-it-yourself healthcare’ [Citation18].

Research in technology adoption has used different theories to predict patients’ behavioural intention to use technological innovations. For example, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT 2) model has been used as a theoretical framework to predict users’ behavioural intention to use technology [Citation19,Citation20]. UTAUT2 includes constructs such as hedonic motivation, price value and habit [Citation21], which are relevant aspects for the adoption and use of home blood pressure monitoring [Citation17]. However, we have not identified any previous qualitative studies exploring these issues in patients using home monitoring of high BP.

Hence, this study aimed to investigate patients’ motives and experiences of home BP measurement, with a focus on constructs derived from the UTAUT 2.

Methods

A qualitative design with semi-structured focus group interviews was used to address the study’s aim.

Recruitment of participants

Recruitment was performed in two ways:

Healthcare staff (none of the researchers) at four healthcare centres in southern Sweden asked patients with hypertension during their visits to participate in the study.

Through a review of medical doctors’ schedules at one of the participating healthcare centres, patients with hypertension booked for annual check-ups were contacted by phone by one of the researchers (IB) and asked to participate.

Inclusion criteria were patients using a home BP monitor, >18 years old, able to communicate in Swedish, without any cognitive impairment, and who monitored BP at home during the last year.

Patients received written information about the study by email and oral information prior to the interview before submitting their consent form. Each focus group interview was booked when five participants had volunteered to participate.

Theoretical framework

UTAUT was described in 2003 and updated in 2012 as UTAUT 2 by Venkatesh, Thong and Xu as a synthesis of different models from information technology acceptance research [Citation19,Citation20]. Key determinants for behavioural intention are performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value and habit. In addition, age, sex and experience have been described as moderators of behavioural intention predicting behaviour [Citation22].

Interview guide

An open-ended interview guide was developed through discussions between the authors (Supplementary 1). The guide was structured according to the key determinants of the behavioural intention in UTAUT 2.

Data collection

Data were collected using semi-structured focus group interviews using the digital platform Zoom. Each interview lasted between 30 to 50 min. Before the focus group, participants received practical information and a link to the meeting with log-in details. The reason for using focus group interviews was to use the group dynamic and interaction to capture different experiences and encourage a discussion between the participants about different aspects of the topic [Citation23].

Two of the authors (one district nurse and one general practitioner) conducted the interviews; one led the interview, and the other had an observer role. Participants were given information about the study and an opportunity to opt out of taking part. All participants were informed orally about the recording using Zoom’s built-in recording function and Zoom’s built-in pop-up window before the recording began. During the interviews, the interviewer asked open-ended and follow-up questions to facilitate discussion. When responses needed clarification, the interviewer asked further questions to elaborate on the answers and followed up with summaries to clarify that the group’s shared experiences were understood correctly. All of the interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Data processing and method of analysis

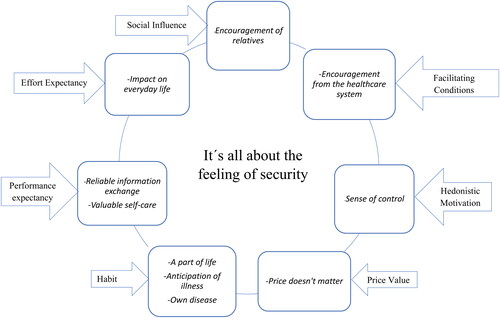

Initially, the researchers read the transcribed interviews. For the data analysis, we used a deductive approach building upon the framework inspired by Graneheim and Lundman [Citation24], as we used a pre-existing theoretical framework (UTAUT2). This method is known for its focus on trustworthiness, which is crucial in deductive content analysis [Citation25]. Central to the qualitative content analysis is sorting the text into different groups: meaning-bearing units, condensed sentences, codes, categories, and themes. All meaning-bearing units and codes were discussed in relation to the theoretical constructs of UTAUT 2. The meaning-bearing units were coded and grouped into 10 subcategories: Encouragement of relatives, Encouragement from the healthcare system, Sense of control, Price doesn’t matter, A part of life, Anticipation of illness, Own disease, Reliable information exchange, Valuable self-care, and Impact on everyday life. These subcategories could then be related to the various theoretical constructs of UTAUT2 (). For data triangulation, five of the researchers discussed the material and reached a consensus on the codes and theme. See for examples of the steps in the analysis process.

Figure 1. Presents the UTAUT 2 constructs in arrows with the underlying categories in the cubes. The overarching theme is in the Middle.

Table 1. Examples of the steps in the analysis process.

Results

Three focus group interviews were conducted between March 2022 and March 2023.

A total of 10 patients participated (3 + 3 + 4), of which two were women, and eight were men, with an average age of 73.4 years (range 64-86 years, median 75 years). The result is presented using the theoretical constructs of UTAUT 2, with a main theme, ‘It’s all about the feeling of security’, comprising 10 categories (). Each citation is followed by (group number/informant number).

Performance expectancy

Valuable self-care

All participants expressed a desire to feel more secure about their BP at home. In addition, there was a desire to ensure continued good health or to be able to establish their own diagnosis. Most participants considered it important to follow the tendency over time to ensure an even and good level of BP. Another important issue reported was to see if a sudden discomfort in the body was due to a change in BP. The participants compared the BP value during the feeling of discomfort in the body with how they felt when the BP was normal.

I had some effect on my… the balance cells or the crystals this summer, and the first thing I did was to take the blood pressure so that it wasn’t low blood pressure or something like that because I got dizzy […], And then I could rule it out right away. (2/2)

Reliable information exchange

Most participants expressed that communication with their healthcare provider became more accessible. For example, upon contact, an exact BP value could be indicated, and if the BP was too high, help was obtained faster. The participants thus became more confident about when to contact their healthcare provider and felt they would be prioritised and taken seriously.

[Blood pressure] was very high. So, then I could say it right away when I called the doctor, or the doctor’s clinic and talked to them and very quickly got help. (2/1)

The participants often brought their measured values to the annual check-up so the doctor could make an overall assessment of further treatment recommendations or make a diagnosis as accurately as possible. However, the participants discussed a recurring feeling that the values measured at home were more accurate than those measured at the clinic. In addition, they expressed that a certain nervousness could be present before monitoring the BP at the healthcare centre, thus giving erroneously high values.

I think you get a more stable blood pressure at home because you are in a home environment without certain factors that interfere. (1/1)

At the same time, there was a concern that the home monitor was not showing accurate values because it might have been incorrectly set, forcing the patient to measure BP repeatedly.

But at home, you can take it easy and take three or four tests one after the other, so you arrive at a stable value, which you don’t do at the healthcare centre, where you only get one value. (3/4)

There was also a desire to be able to calibrate their BP monitors to eliminate the risk of erroneous values. To ensure a more precise and reliable information exchange of the monitored results, some participants brought their BP monitors to the healthcare centre and compared them directly with the measurements made there with the healthcare centre’s BP monitors.

Effort expectancy

Impact on everyday life

The participants did not find the home BP measurement process particularly hard or strenuous, as long as the device’s instructions were followed. The negative feelings about home BP measurement were that it could induce increased health stress and a fixation on the measurement itself. This fixation could itself increase BP and cause additional worry and anxiety if it generated an obsessive control of the BP.

It must not be that you become so insecure, so nervous that something will happen that it becomes a goal itself in some way, huh? (1/3)

The participants initially found the monitoring a bit stressful, but they overcame it in time. The measurement situation was a naturally calm period when the study participants could sit and think during the day. It also seemed to be completed relatively quickly. However, some wondered if it might have been more difficult during more stressful periods of life:

If you only have the time […] There was a difference when you were active all the time and worked all day long, then maybe you would not have had time to take it easy in the same way. (2/2)

[…] As a user, it is straightforward to use. It is no inconvenience at all. (2/3)

Social influence

Encouragement of relatives

Good support from home was important for the participants, which they also felt they had.

It was also described that some relatives also measured their BP at home. Relatives’ BP measurement was also a reason to start monitoring their BP at home; for example, when the relative had different values at the healthcare centre and at home, it could inspire their measurement. Others expressed appreciation for the consideration of relatives and reminded that BP should be measured if, for example, they showed signs of illness.

My wife reminds me very, very rarely nowadays. But she’s keeping an eye on me! (1/2)

There was also a description of more indirect social influence when a participant had home BP monitors demonstrated by a pharmacist through a work-related study circle, which contributed to the participant starting self-monitoring.

Facilitating conditions

Encouraged by the healthcare system

In addition to relatives, other significant individuals influenced the participants to start monitoring their BP at home. It was described mainly as healthcare professionals who recommended and encouraged the purchase of BP monitors for continuous home check-ups:

[…] Then when I got sick […], and the doctor also thought I should do it, I thought yes, okay, then I'll do it! (2/2)

Well, if you had been advised to take it a certain number of times, then absolutely. (2/1)

There was a desire that the healthcare system should push more for the measurements to be carried out at home so that it was noticed if BP would slowly rise.

In addition, there was also a desire for the healthcare system to remind people to take the check-ups, as the participants considered it important that they were done regularly. This could be done, for example, through an automatic reminder from the healthcare provider when it was time to take the BP and that the response was sent in and stored automatically so that all values were available for continuous BP control by the caregiver.

Hedonistic motivation

Sense of control

Important feedback that the participants reported was a sense of control.

By monitoring the BP, the participants got confirmation of good health and an assurance that everything was okay. The measurements were used as a kind of record for one’s well-being. It was described that if the feeling was in a certain way, this was directly reflected in the results of the BP measurements.

Now, after all these years, I've started using it as a recognition sign, when I feel something that’s changing in my body, I take the blood pressure to be allowed to know like that this is what they feel like when the blood pressure is high, or this is what they feel like when it’s very low. (1/3)

It felt extra good to control the BP at home due to the previous absence of symptoms despite very elevated BP. It was also stated that by monitoring BP, their own disease could be followed- up to avoid a relapse or suffering from a more severe illness.

[Home blood pressure measurement] is what puts me in control of my life. […] thus now I've had three strokes, and I wouldn’t have survived them if I hadn’t checked myself at home. (1/3)

Home BP measurement was also used to determine whether regular medication needed to be supplemented with extra medication or, if necessary, on-demand medication for better well-being. In addition, home BP measurement was used to control the effect of new prescribed medications. When higher values than expected were measured, the patients reflected upon factors before the measurement that could have affected the BP.

Yes, I think about what I did before […] I come from the gym and come home and take it after that, yes, then it can be higher, and has it been stressful at work […] you get involved a lot in, then it is also higher […].(3/3)

Some respondents discussed their interest in digital accessories, such as heart rate monitors, with warnings that could indicate something was wrong. A consequent check with a BP monitor could further contribute to the sense of control.

Price value

Price doesn’t matter

A solid underlying opinion was that buying your own BP monitor was relatively cheap. However, even if it had been more expensive, the measurement was so important to the participants that they had considered getting a BP monitor even if the price had been higher. Therefore, an acceptable cost concerning the perceived benefit was approximately SEK 500 (approximately €42) as a reasonable upper ceiling. However, some participants were prepared to pay significantly more for a good-quality BP monitor.

You should not care if it costs 500 instead of 150 (Swedish crowns, SEK), but you should invest in a high-quality BP monitor. (1/2)

Quality was seen as much more important than price. The participants described a belief that quality followed price, and therefore, there was a willingness to pay more to ensure the BP monitor was reliable. However, with an increased price came access to other technical solutions, which some of the participants described as important, and thus there was the willingness to pay a little extra for the availability of different technical solutions, such as a connected application where it was possible to follow the tendency of BP values over time.

Habit

A part of life

The participants who measured their BP regularly saw it as part of their life and lifestyle. For example, it could be part of the daily routine in the morning at the same time as the mental preparation for the day. If it was not measured every day, it would still be seen as a prominent part of everyday life to measure BP every now and then.

So that it is part of my everyday life. Even if I don’t take it every day, which I don’t. (1/3)

The participants believed the BP monitor should be strategically placed to make it easier to remember to measure their BP.

The participants believed the BP monitor could be developed into a more pleasurable design, so it could be strategically placed in the home, as a constant reminder to measure the BP ‘But I think it should be there so that just when you feel something happening in your body, it should be available’. (1/3)

Anticipation of illness

Another thing that could get participants to measure their BP more often was if there was an expected reason why it could be elevated. The reasons mentioned were, for example, heredity for cardiovascular disease or stressful periods in life, which could cause increased BP and, thus, illness.

Own disease

A common denominator for the participants was that they had started taking BP at home after a past illness, such as a heart attack, stroke, or atrial fibrillation. However, before the illness, there had been no thought of monitoring BP at home. Nor could they see that there was anything that could have motivated them to take their BP at home before they fell ill, which some regretted afterwards.

I was no more than 50 years old when I had my first stroke… at that age, you do not think about [increased blood pressure], huh? Then, like life rushes… Oh it, it’s just not on the map. But it should be on the map. Have I learned now? (1/3)

Discussion

In the framework of UTAUT 2, the results in this study indicate that home BP measurement entails low user effort and a high reward in the form of increased security, as well as a reliable information exchange with the healthcare system. Home BP monitoring was perceived as a cheap and easy way to gain increased control over one’s health.

Our results are aligned with previous research that showed that participants were positive toward home BP monitoring [Citation26]. Previous research has also shown that home BP monitoring increases security in everyday life by quickly and easily ruling out or confirming deterioration in this silent but potentially severe disease [Citation27].

Our results are also consistent with the findings of Jones et al. [Citation28], describing the patients’ feeling that the BP results measured at home corresponded better with reality than those measured during visits in the clinic.

Furthermore, the respondents in the present study did not report negative emotions or opinions toward home BP monitoring, which is similar to findings from Walker et al. [Citation12]. They also revealed that home monitoring of various chronic diseases, including hypertension, can increase patients’ feelings of reassurance, disease-specific knowledge and shared decision-making [Citation12].

This contrasts with other studies, reporting concerns about increased personal responsibility for interpreting the BP monitor’s results and that the technical aids will obstruct access to care rather than facilitate contact [Citation27]. Previous research has also shown concerns among participants that the home measurement would increase burden, such as finding out something negative about their health or that they didn’t trust the technology, and a concern about being reduced to just a number and losing their face-to-face time with their caregiver [Citation12]. However, none of these concerns appeared during the interviews in the present study. The patients in our study expressed high confidence in self-documentation of the blood pressure data for further communication to the PCC and the general practitioner as needed, thus indicating good accessibility and continuity of care. However, even if patients have reported self-confidence with self-monitoring of BP, there can be a reluctance to self-titration of medication [Citation28] and concerns about additional personal responsibility [Citation12].

In the present study, participants called for other ways to further enhance the feeling of security, such as automatic healthcare system reminders. Our results may differ from previous studies since our study was conducted post the COVID-19 pandemic, when digital solutions became more common and appreciated. This can explain why previous studies showed a decreased adherence to home BP measurement over time [Citation12,Citation29]. Patients not accustomed to technology were more uncomfortable with home BP measurements and did not trust the measurements from the home BP monitor [Citation12].

Strengths and limitations

One strength of this study is the use of a structured interview process based on an accepted theoretical model that predicts patients’ acceptance of technological inventions. In addition, focus groups could discover and deepen the complexity of a study’s purpose and facilitated engagement between participants that can provide more nuanced descriptions [Citation30]. Between the focus groups, the researchers listened to the first recordings and discussed the quality of the data collection. However, no adjustments were needed regarding the interview guide or setting. The researchers who conducted the interviews and data analysis were working in primary care health centres in Sweden during the study period. During the interviews and data analysis, the researchers kept their preunderstanding of the topic of home blood pressure monitoring explicit but bracketed it by using open questions to increase reflexivity. The interviewees’ responses aligned with the researchers’ perceived experience of the primary care context, thus increasing the validity and credibility of the results.

Using Zoom for the interviews allowed including informants from a larger geographical area, which is a strength, thus increasing the transferability of the results.

The study has some weaknesses that should be mentioned. First, the number of participants should ideally be 5-8 per focus group [Citation23]. However, the group size may have been an advantage, as the co-interviewer noticed that the participants were easily interrupted by each other trying to fill in a gap or to say something simultaneously.

A previously negative image of home BP measurement and low digital literacy [Citation31] most likely affected the willingness to participate in this study. Even if all participants were informed about interviews via Zoom, some who dropped out late perceived the format as intimidating, however, it is possible that more tech-savvy people were faster at getting home BP monitors and that the digital format of the interview did not deter them.

There is also a risk of selection bias; all our participants had no doubts about the price, could afford to buy a BP monitor, and used it for the last year. Thus, we have not selected those who stopped monitoring when the novelty subsided and only included those who have integrated home BP measurement into their everyday lives. This may explain why none of the participants found it challenging to remember measuring their BP. They also chose to participate in online focus groups and might, therefore, have had more positive attitudes towards technology and the use of monitoring tools, which further increases the risk of selection bias. Within the qualitative research design lies the limitation of non-generalizability. This might also negatively affect the transferability of the results to a broader population.

Conclusion

Through the UTAUT 2 model, we identified important factors for the patients’ behavioural intention to use home BP monitoring, with many favourable conditions and few obstacles to implementing this in routine healthcare. Home monitoring seemed like a way to increase the feeling of security in everyday life; home monitoring of BP functioned as an intervention to maintain health and prevent the onset of further illness. There were few negative experiences, perhaps due to the technology-positive individuals who chose to participate in the online interviews.

Author contributions

PN conducted all three interviews, analysed material, and wrote the manuscript. IB observed two interviews, analysed material, and prepared the manuscript draft. BBB observed one interview and wrote and revised the manuscript. MW wrote and revised the manuscript. SC formulated the research question, planned the study, analysed the material, and revised the manuscript. ACLL formulated the research question, planned the study, and revised the manuscript. VMN formulated the research question, planned the study, analysed the material, and revised the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr2022-01199-02)

Competing interests

None of the authors has any competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank science editor Patrick O’Reilly for his valuable comments on the text.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 [cited 2023 May 10]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44203/9789241563871_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- St Sauver JL, Boyd CM, Grossardt BR, et al. Risk of developing multimorbidity across all ages in an historical cohort study: differences by sex and ethnicity. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2):e006413. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006413.

- McCance T, McCormack B, Dewing J. An exploration of person-centredness in practice. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(2):1. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No02Man01.

- Guanais FC. Patient empowerment can lead to improvements in health-care quality. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):489–490.

- Leonardsen AL, Hardeland C, Helgesen AK, et al. Patient experiences with technology enabled care across healthcare settings ‒ a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):779. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05633-4.

- Cafazzo JA, Leonard K, Easty AC, et al., editors. Bridging the Self-care Deficit Gap: remote Patient Monitoring and the Hospital-at-Home. Electronic Healthcare. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009.

- Chase HP, Pearson JA, Wightman C, et al. Modem transmission of glucose values reduces the costs and need for clinic visits. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1475–1479. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1475.

- Bayliss EA, Steiner JF, Fernald DH, et al. Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):15–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.4.

- Breaux-Shropshire TL, Judd E, Vucovich LA, et al. Does home blood pressure monitoring improve patient outcomes? A systematic review comparing home and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring on blood pressure control and patient outcomes. Integr Blood Press Control. 2015;8:43–49. doi: 10.2147/IBPC.S49205.

- Stergiou GS, Bliziotis IA. Home blood pressure monitoring in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension: a systematic review. AmJ Hypertension. 2011;24(2):123–134. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.194.

- Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens. 2008;26(8):1505–1526. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328308da66.

- Walker RC, Tong A, Howard K, et al. Patient expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for chronic diseases: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Med Inform. 2019;124:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.013.

- Fuchs SC, Ferreira-da-Silva AL, Moreira LB, et al. Efficacy of isolated home blood pressure monitoring for blood pressure control: randomized controlled trial with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring – MONITOR study. J Hypertens. 2012;30(1):75–80. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834e5a4f.

- Pioli MR, Ritter AM, de Faria AP, et al. White coat syndrome and its variations: differences and clinical impact. Integr Blood Press Control. 2018;11:73–79. doi: 10.2147/IBPC.S152761.

- National Health Service England (NHS). Home blood pressure monitoring: nhs.uk; 2023. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/cvd/home-blood-pressure-monitoring/

- Cottrell E, Cox T, O'Connell P, et al. Implementation of simple telehealth to manage hypertension in general practice: a service evaluation. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0301-2.

- Natale P, Ni JY, Martinez-Martin D, et al. Perspectives and experiences of self-monitoring of blood pressure among patients with hypertension: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Hypertens. 2023;36(7):372–384. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpad021.

- Carrera PM, Dalton AR. Do-it-yourself healthcare: the current landscape, prospects and consequences. Maturitas. 2014;77(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.10.022.

- Roebroek LO, Bruins J, Delespaul P, et al. Qualitative analysis of clinicians’ perspectives on the use of a computerized decision aid in the treatment of psychotic disorders. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):234. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01251-6.

- Kessler SKMM. How do potential users perceive the adoption of new technologies within the field of Artificial Intelligence and Internet-of-Things ‒ a revision of the UTAUT 2 model using Voice Assistants. Lund; 2017 [cited 2023 May 10]. https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8909840&fileOId=8909844

- Tamilmani K, Rana NP, Wamba SF, et al. The extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): a systematic literature review and theory evaluation. Int J Inf Manage. 2021;57:102269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102269.

- Venkatesh VT, James YL, Xu X. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: a synthesis and the road ahead. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2016;17(5):328–376.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, et al. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1):215824401452263. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633.

- Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society Of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52(1):1–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.189011.

- Grant S, Greenfield SM, Nouwen A, et al. Improving management and effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring: a qualitative UK primary care study. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(640):e776-83–e783. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X687433.

- Jones MI, Greenfield SM, Bray EP, et al. Patients’ experiences of self-monitoring blood pressure and self-titration of medication: the TASMINH2 trial qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(595):e135-42–e142. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X625201.

- Margolis KL, Asche SE, Bergdall AR, et al. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure control: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(1):46–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6549.

- Polit DFBC. Nursing Research. 11th ed. Philadelphia : Wolters Kluwer. 2021.

- Abdullah A, Liew SM, Hanafi NS, et al. What influences patients’ acceptance of a blood pressure telemonitoring service in primary care? A qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:99–106. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S94687.