Abstract

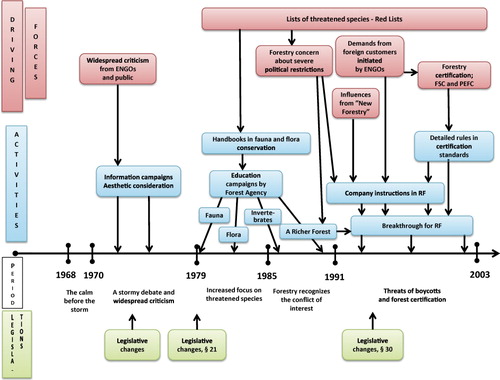

Retention forestry (RF) is a modified form of clear-cutting that has been introduced recently in several countries. It is intended to integrate the conservation of biodiversity with timber production and to maintain the provision of other ecosystem services by retaining important forest qualities, habitats and structures. In this study we seek to identify forces driving the conceptual development, acceptance and implementation of RF in Sweden by describing and investigating the RF debate among foresters and environmental NGOs from 1968 to 2003. Specifically, we seek to elucidate when RF was first proposed, the arguments for and against it, and pivotal trends in the debate. Our study is based on thorough systematic analysis of articles published in journals issued by two non-profit associations. Our data show that the development of RF in Sweden was driven by several interacting factors and we distinguish critical time periods, from strong debates and conflicts during the 1970s until the breakthrough of forestry certification at the turn of the millennium. We argue that historical analysis of the forces driving changes in forestry management is important for elucidating why changes occur and the dynamic nature of perceptions and uses of forest ecosystems in modern societies.

Introduction

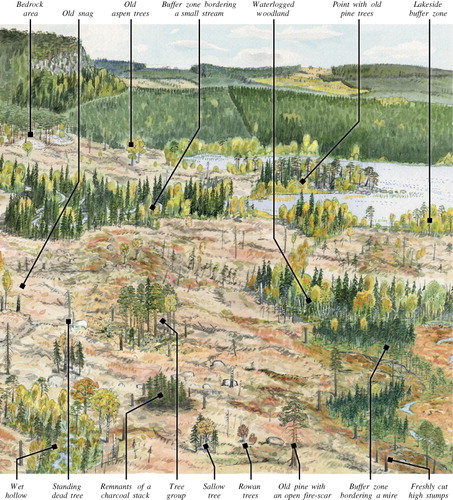

Retention forestry (RF) is a modified form of clear-cutting that has been introduced in several countries during recent decades (Gustafsson et al. Citation2012). The overall aims of RF are to integrate the conservation of biodiversity with timber production and to preserve other ecosystem services by retaining important elements during harvests. These elements may include both structures and areas, such as single trees of particular ecological value, tree groups, standing dead trees (snags), downed dead trees and patches with valuable habitats, e.g. waterlogged woodlands and buffer zones bordering watercourses, lakes and wetlands (). RF received considerable international attention following development and application of the so-called “New Forestry” concept in the Pacific Northwest region of the USA in the late-1980s (Franklin Citation1989; Gustafsson et al. Citation2012).

Diverse terminology is used to describe RF, such as variable retention cutting (Franklin et al. Citation1997; Aubry et al. Citation2009), green-tree retention (Rosenvald & Lõhmus Citation2008), tree retention (Gustafsson et al. Citation2010), retention harvesting (Lindenmayer et al. Citation2012) and the retention approach to forestry (Gustafsson et al. Citation2012). The terms aggregated or group retention and dispersed retention are used to describe the spatial distribution of retained elements. RF has numerous more specific purposes, including: “life-boating” species between forest generations; increasing amounts of substrate in new forest generations; and enhancing connectivity in the forest landscape (Franklin et al. Citation1997). Among further benefits are to promote early successional species; to maintain various ecosystem functions such as mycorrhizal processes; to mitigate the impact of harvesting on surrounding environments, e.g. watercourses; and to improve the aesthetic appearance of harvested areas (Gustafsson et al. Citation2012). A comprehensive meta-analysis including 78 studies on the effect on biodiversity of retention approaches has recently been published (Fedrowitz et al. Citation2014).

Clauses related to RF have been included in the Swedish Forestry Act since 1975, when a key paragraph was complemented with a clause stating that consideration of nature should be incorporated in forest management (SFS Citation1974). In 1979 a new, separate section on nature consideration was added for the first time, §21 (SFS Citation1979). Most regulations in §21 stipulated that aesthetic values and recreational interests should be considered. In 1993 a revised Forestry Act was passed, enshrining a major change in forest policy (still valid), stipulating that environmental and production values should be regarded as equally important. Now the key paragraph, §1, states: “The forest is a national resource that shall be managed in such a way as to provide sustainable good yield while maintaining biological diversity. Forest management should also take into account other public interests” (SFS Citation1993). In the new Forestry Act the clauses on nature consideration are in §30, which provides regulations stipulating that appropriate measures shall be taken regarding care-demanding habitats, plant and animal species, buffer zones, trees and groups of trees and the size of clear-cuts. Most of the regulations in §30 concern biodiversity unlike the corresponding section in the previous law of 1979.

The measures intended to foster implementation of RF in Swedish forestry policies have always been “soft”, including the provision of substantial resources for relevant education and advice, while legal regulation has been weak (Hysing & Olsson Citation2005; Götmark et al. Citation2009). The law is based largely on “freedom under responsibility” (Bush Citation2010, p. 472). The regulations in the legislation are mandatory, but if a forest-owner does not follow them no sanctions can be imposed unless the Swedish Forest Agency has issued an injunction stating which specific consideration(s) should be applied. Another major limitation of the law is that the conservation requirements must not be “so extensive as to severely handicap current land use” (Bush Citation2010, p. 476).

Sweden was one of the first countries to implement RF, and is one of few countries where it is practiced by all landowners, public and private. However, it is also widely practiced now in industrial forestry in several countries, mostly in Europe and North America (Gustafsson et al. Citation2012). This can be regarded as a paradigm shift for forest management since it is more consistent with an ecosystem-oriented approach to natural resource management than most traditional forestry models (Franklin Citation1993). However, although various aspects of RF have been addressed by numerous authors, there have been no detailed analyses of its conceptual development, acceptance and implementation (hereafter development).

Identification of driving forces and their interactions is an essential component of land-use change analyses (Bürgi et al. Citation2004; Hersperger et al. Citation2010) and has a long tradition (e.g. Wood & Handley Citation2001). For example, in a landscape context Bürgi et al. (Citation2004, p. 858) defined them as “the forces that cause observed landscape changes, i.e. they are influential processes in the evolutionary trajectory of the landscape”. In the current context an analysis of forces driving the focal changes in forest management practices may reveal the most important drivers as well as the interaction between them. Driving forces are commonly classified into socioeconomic, political, cultural, technological and natural types (Brandt et al. Citation1999). Methodological approaches in the study of drivers vary greatly and include (inter alia) quantitative analyses of meta-data on land-cover and socio-economy (Geist & Lambin Citation2002), interviews (Schneeberger et al. Citation2007) and document analysis (Hersperger & Bürgi Citation2009).

The main objective of this study is to identify the key driving forces behind the development of RF in Sweden by describing and investigating the RF debate among foresters and environmental NGOs (ENGOs) during the period 1968–2003. Specific questions we address include the following. When did the argument for and discussion about RF first appear? What were the main points raised by key interest groups? Can the development of the RF debate be separated into distinct periods with different driving forces? How did RF develop in Sweden in comparison with neighbouring countries and the “New Forestry” concept in the USA? Why were conservation actions integrated with production forestry instead of maintaining the traditional conservation strategy of establishing reserves, i.e. separating production and conservation? Our ambition is to contribute to explanations of the processes whereby factors related to human values, governance and socio-economic conditions (nationally and internationally) lead to changes in land-use practices.

Materials and methods

Swedish forestry and conservation

In Sweden there is 23 million ha of productive forestland, of which 56% is privately owned, often in small holdings. Large privately owned forestry companies own 25% whilst the state and other public landowners own 19% (Swedish Forest Agency Citation2013). Sweden is the world's second largest exporter of paper, pulp and sawn wood products (The Swedish Forest Industries Citation2012) and was one of the first countries to introduce the two international certification systems, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). Currently, they cover similar areas, about 11 million ha of productive forestland (The Swedish Forest Industries Citation2012), some forest-owners are certified by both systems.

One of several environmental objectives in Sweden is to preserve forest biodiversity. To meet this objective Sweden has developed a multi-scaled model, “the Swedish model”, for biodiversity conservation (Angelstam Citation2003; Gustafsson & Perhans Citation2010). This model is usually divided into three levels, and RF covers the small-scale level, from individual trees to patches up to about 0.5–1.0 ha. The medium-scale level comprises parts of stands or entire stands from 0.5 to 1.0 ha up to about 15–20 ha, and the large-scale level covers greater areas. The forest-owner is responsible for meeting the small-scale (RF) objectives and currently 3–5% of the clear-cut area is retained for nature conservation (Gustafsson et al. Citation2012). The state is responsible for the large-scale level and responsibilities for the medium level are mixed. Concerning the responsibility of the state, about 3.6% of the productive forestland is legally protected, mainly in large-scale nature reserves (Swedish Forest Agency Citation2013). Forest-owners also voluntarily set aside 1.1 million ha of forestland, mostly in medium-scale set asides, amounting to 4.7% of the productive forestland (Swedish Forest Agency Citation2013).

Analysis of historical sources

Our study is based on a thorough, systematic analysis of articles, published between 1968 and 2003, in journals issued by two non-profit associations in Sweden representing key interest groups (cf. Anshelm Citation2004; Lindkvist et al. Citation2011; Lundmark et al. Citation2013). One is Skogen (“the Forest”), the Swedish Forestry Association's magazine, and the others are the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation's (SSNC) magazine Sveriges Natur (“Nature of Sweden”) and annual Sveriges Natur årsbok (“The Yearbook of Nature in Sweden”). Both of these organisations are umbrella organisations and their journals are regarded as providing representative views of the forestry sector (including forestry industries) and Swedish non-governmental conservationists, respectively. Much of the public debate on forestry and forest conservation issues in Sweden during the last 50 years (including views of the foremost protagonists) has been expressed in these journals.

We scrutinised all issues of each journal published during 1968–2003, following recommendations that the time period for such analysis should cover all major changes in the study system (Bürgi et al. Citation2004). The starting year of 1968 was chosen because a pilot study indicated that RF was not discussed before then and the end year of 2003 because international forest certification efforts and RF were well established by then.

In a first step 2191 ordinary articles, reviews, editors' comments, letters to editors and announcements, all with some relevance to the subject, were chosen. The subject content of each article was summarised in one sentence and each article was categorised according to a three-graded scale of relevance for this study. In a second step 899 of the most relevant articles were chosen for thorough analysis. Each of these articles was categorised according to type (e.g. editorial, article, letter to the editor), subject relevance (using a 4° scale) and subject type. All articles related to RF and our questions were more deeply analysed and both summaries and quotes were compiled. Also, many more general articles on forestry/conservation were examined to place the RF discussion in a broader conservation context. Out of all of the 899 studied articles, 55% were regarded as having moderate or high relevance for the aims of the study (). Divided into 5-year periods, the highest proportion of articles was published during the years 1990–1994 (21% of all articles) and the lowest during the years 1975–1979 (13%; ).

Table 1. Numbers of analysed articles with indicated relevance to the topic.

Table 2. Numbers of analysed articles from Skogen, Sveriges Natur and Sveriges Natur årsbok published in indicated time periods.

In the text, references from Skogen, Sveriges Natur and Sveriges Natur årsbok are marked S, SN and SNA, respectively. For S and SN articles, the publication year, issue and page are given, while for SNA articles, the publication year and page are given. The Swedish state forest agency, Skogsstyrelsen in Swedish, was previously called The National Board of Forestry in English but is presently called the Swedish Forest Agency. All three names appear but refer to the same agency. Formal forest research and higher forestry education were provided by the Royal College of Forestry (Skogshögskolan) until 1977 when it became part of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, abbreviated as SLU.

Results

1968–1970: the calm before the storm

Plantations on previously farmed land

In the late 1960s conservation problems associated with clear-cuts were not discussed, at least in the source journals. The major forestry-related issue of the time was the large-scale plantation of spruce on previously farmed land, which had been going on for decades. The plantations darkened the previously open pastoral cultural landscape, much of which was situated close to habitations (SNA 1969:53–63; SN 1973:3:147–149).

1970–1979: a stormy debate and widespread criticism

Aerial spraying sparks criticism

In the early 1970s a very widespread debate about Swedish forestry suddenly started, initiated by massive protests against aerial spraying of herbicides to control brushwood in clear-cuts (SN 1972:6:279; S 1971:9:283; ). A forester wrote that the debate had a clear starting point in 1970 after a lethal incident, which was subsequently shown to be unrelated to the substances allegedly involved. Analogies were made to the use of herbicides in the Vietnam War (SNA 1973, 43–56). The criticism then expanded to cover other forest management practices, such as fertilisation, scarification, use of DDT, planting alien tree species and use of clear-cutting as a forestry method. The first news item in Sveriges Natur about the criticism of clear-cutting is from 1971: “Whilst scientists continue to debate the medical effects of phenoxy acids, people in Värmland have hit on another feature of modern forestry: the large clear-cuts. This has quickly gained growing support across the country” (SN 1971: 6:282).

The conservation movement's criticisms of clear-cutting included the drastic alteration of the landscape it caused, the negative ecological consequences of planting large monocultures after clear-cutting, and the damage caused by large vehicles during associated operations (SN 1972:6:279–283; SN 1972:6:283–284; ). Often the criticism was more general, e.g. “the soils are depleted, the ground-water is contaminated and the water balance in the ground is upset” (SN 1976:3:111–114).

The foresters had difficulties understanding and assimilating the harsh criticism from the conservation movement. They felt wrongly condemned when forestry was identified as a “serious environmental threat” (S 1973:2:39) or accused of “vandalism” (S 1971:8:260–261). The common arguments in favour of clear-cutting included the following. First, clear-cuts were said to be ecologically justified as they mimic forest fires, which are natural disturbances (e.g. SNA 1973:61–74). Second, it was stated that forestry is conservation. Foresters viewed the clear-cutting of old, slow-growing forests and replacement with plantations as active conservation, as illustrated by the following quotation by a chief forester of a large forestry company.

If we did not cut our forests, they would not continue to look the way they do forever. We would see what one calls forest slums. And slums, whether it concerns forests or houses, must be cleaned, to make room for something new and better. (S 1971:8:260–261)

An “information problem”

The foresters interpreted the criticism of forestry in general, and clear-cuts in particular, as an information problem. They regarded the conservation demands as diffuse and unfounded opinions, whilst forestry provided the facts (SN 1977:3:111–112; SN 1977:4:138). They believed that if only the public had sufficient knowledge about forestry practices and understood that new forests would grow on the clear-cuts, they would accept the practices (S 1970:23:569; S 1971:2:53). This led to the establishment of a forestry working group to address information issues (S 1971:5:141) and arrangement of meetings with journalists to explain forestry methods (S 1971:9:283). One debater in Sveriges Natur was highly critical of this “Forestry information group” and its arguments (SN 1972:6:284–285).

There was obvious irritation from the conservation side about the forestry attitude of “We know best” and there was a view that foresters denied that they had a conflict of interest (SNA 1973, 13–15; SN 1986:1:32–33). However, a certain degree of self-criticism from the foresters can be sensed in the debate, as they acknowledged that clear-cuts ought to be smaller and more aesthetically appealing (S 1971:4:122; S 1972:3:75). They reckoned that the public reaction to clear-cuts was based on aesthetic values, a general perception that they had made the scenery less beautiful (S 1971:9:298), but this could be fixed by adapting clear-cuts to the landscape more harmoniously, making smaller clear-cuts or retaining trees or tree groups on clear-cuts to eliminate the bare impression (S 1972:2:42). An example of the latter is the following quotation from Skogen: “Let the forest be left where the productivity is low. It provides a pleasant break in a bare landscape” (S 1973:1:7). The foresters responded to the criticism of forestry in 1974 by developing a common policy statement supported by owners of all categories (S 1974:9:362–364) and adopting various forms of environmental programmes (e.g. S 1974:3:92–94). The Swedish Forest Service (Domänverket, in Swedish) programme stated for instance that:

Consideration to landscape scenery and wildlife environments can call for forests, tree groups and individual trees on bogs, mountains or other forest impediments to be preserved in addition to the placement of clear-cuts so that the landscape scenery is disturbed as little as possible. (S 1973:3:71)

The criticism directed against clear-cuts is only mildly associated with appearance. Mostly, it is controlled by other values, where clear-cuts are perceived as a consequence of poor forest resource management. If this hypothesis is true, we can hardly solve the debate about clear-cuts by giving them a more attractive appearance. (S 1978:9–10:42–43)

The government's clear-cutting investigation

The widespread criticism of clear-cuts led to many suggestions to parliament about forbidding clear-cuts. This resulted in the Ministry for Agriculture establishing a working group to investigate the impact of clear-cuts on the environment (S 1972:3:75; SN 1972:2:107). The group presented a report in 1974, clarifying the official standpoint as being that clear-cutting was the most appropriate harvesting method on most forestland. This was also supported by the referral organisations. The report suggested various kinds of RF, such as “leaving trees or tree groups to break the monotony of uniform landscapes or to avoid indentations on the horizon” (S 1974:7:270–272, 283). These suggestions mainly focused on aesthetic considerations, but included the retention of trees that provide nesting for certain birds and dead trees. Furthermore, incorporation of mandatory reporting of planned clear-cuts and a general precautionary rule about nature consideration in the forestry legislation was recommended (S 1974:7:270–272, 283). In response to the report, the SSNC stated that they were “aware that the method of clear-cutting must be used despite the large uncertainties about the effects of clear-cut forestry on the forest ecosystem…” (SN 1974:6:268–269). The report's recommendations were passed in parliament, leading to changes in the Forestry Act from 1 July 1975. The clause “Consideration must be shown towards conservation interests” and mandatory reporting were introduced for clear-cuts larger than 0.5 ha (S 1975:8:415). The change in legislation meant that forest-owners had to “submit to a certain amount of intrusion due to consideration towards conservation interests” and that this ought to be “a normal part of forestry operations” (S 1976:4:141–142).

1979–1985: increased focus on threatened species

Threatened species

In the early 1970s there was criticism that clear-cut forestry was disadvantageous for rare plants and animals, leading to various demands. For instance, the SSNC demanded improvements in protection for eagles by forbidding clear-cutting in the vicinity of their nests (SN 1973:5:269), specific measures to mitigate impacts on woodpeckers and the retention of large deciduous trees on clear-cuts (SN 1974:2:58–60). Prominent scientists also expressed concerns about the implications of clear-cutting for flora and fauna. A professor of botany, Måns Ryberg, wrote about clear-cut forestry:

This means that plants and animals that need old, untidy trees, e.g. hole-nesting birds in general, raptors, many insects and small animals, bryophytes and lichens will disappear or at least be strongly depleted in the new monocultures of spruce and pine. (SNA 1973, 17–27)

Forest scientists' knowledge about the negative impacts of clear-cut forestry on certain plants and animals increased during the late 1970s and early 1980s (SNA 1975, 121–125). In 1977, a book about fauna conservation was published by a professor at the Royal College of Forestry (Ahlén Citation1977). The book provided advice on different types of RF that would benefit threatened bird species (S 1977:11:482–483). In 1979, the Swedish Forest Agency issued a book on fauna consideration in managed forests, the first of seven on various aspects of conservation (Ahlén et al. Citation1979).

A new Forestry Act and criticism of it

In 1978 a new forestry report was presented, recommending a substantial increase in forest production by fertilisation, ditching, the use of alien tree species and various suggestions for a new Forestry Act (S 1978:2:4). The SSNC was highly critical of the report, stating that issues related to flora and fauna had not been sufficiently considered (SN 1978:6:374) and the society protested to the Committee for Agriculture against its espousal of clear-cutting as the only harvesting method (SN 1979:3:123). A new Forestry Act came into force on the 1 January 1980, which for the first time included a separate section on nature consideration, §21, including detailed regulations composed by the Swedish Forest Agency after consultation with forestry and environmental organisations (S 1979:14:4). Conservationists were quick to criticise the new Forestry Act. They complained that a landowner could flagrantly break the conservation regulations without sanctions, unless the Swedish Forest Agency issued an injunction or banned a specific action (S 1980:13:7; S 1980:15:12). In a response to the Swedish Forest Agency the SSNC requested clearer legislation and stated that “too much is left for the landowner to decide concerning how much nature consideration should be shown” (SN 1982:7:35).

A scientific assessment of the quality of the nature consideration stipulations in §21 of the Forestry Act was presented in the early 1980s by a forester, Katarina Eckerberg, of the Royal College of Forestry. A total of 146 areas were studied before and after clear-cutting. The results showed considerable deficiencies regarding, for instance, consideration towards the retention of dead trees and that the nature consideration was strongest at sites where there was little economic incentive to harvest forests, i.e. on bare rock, steep slopes and fens. More training, better planning and more conservation specialists in forestry were recommended to improve quality (S 1985:2:52–55; SN 1985:2:14–15). These results initiated considerable debate and the SSNC often referred to the shortcomings highlighted in the study (e.g. SN 1986:6:34). An editorial in Skogen included the following passage regarding the reported results:

conservation issues need to receive more attention in forestry. The main reason for this is of course that nature consideration has intrinsic values. The same resource that allows us to manage our forests, maybe most efficiently in the world, can also be a threat to fauna and flora … Without satisfactory management of conservation we cannot argue for efficient forestry methods. (S 1985:2:4)

An influential forester, Börje Häggström, complained that Katarina Eckerberg had interpreted the Forestry Act subjectively and questioned the value of several conservation measures, such as leaving dead trees. He pointed out that 2.2% of the timber stock consisted of dead trees and concluded that “Insects and fungi could hardly have too little dead wood” (S 1985:7:48). In a letter to the magazine a forester stated that it is a misconception that it is mandatory to follow the Forestry law, and claimed that it is the forest-owner who has to decide how the forest should be managed until a formal financial penalty is imposed by the Swedish Forest Agency (S 1986:4:56). An editorial in Skogen joined this line of debate, claiming: “The instructions for §21 should mostly be regarded as examples of nature consideration … Blindly following detailed conservation instructions can lead to questionable results” (S 1986:9:4).

1985–1991: forestry recognises the conflict of interest

Lively debate about the book “Living forests”

In 1985 the SSNC started a large forest campaign and lobbied the government with demands for a new Forestry Act (SN 1985:2:12; SN 1985:3:22–23). Another part of the campaign focused on the importance of leaving hollow trees on clear-cuts to benefit all the species that depend on them (SN 1985:2:29–30). In addition, a book about forestry was published, “Levande Skog” (“Living forests”; Olsson Citation1985), providing the SSNC's view on environmental problems associated with forestry and suggestions for improvement. One of the three main suggestions was that more extensive nature consideration should be shown on all forestland (SN 1985:2:13–14). The book received great attention in Skogen, where both an editorial and a review were very critical of its descriptions of forestry and related environmental problems (S 1985:4:6; S 1985:4:10–11). The critique of SSNC's book led to a lively debate in Skogen, where Björn Hägglund (then Director of the Swedish Forest Agency) and a County Forester regarded the criticism as biased (S 1985:7:42; S 1985:7:46–47; S 1985:9:46). Hägglund urged forestry representatives to “Change their attitude” (S 1985:7:42), because they had not shown that they were capable of participating in a constructive debate with conservationists. He wrote that: “We demand that conservationists listen to forestry…. But then we must also listen to them” (S 1985:7:42).

The Swedish Forest Agency presented a new policy in 1985 with a stronger focus on conservation of fauna and flora (S 1985:12:6–7). The Swedish Forestry Association organised a large field trip in the same year, with the theme “Fauna and flora management in forestry”, during which scientists and foresters discussed different types of RF (S 1985:7:50–51). The SLU autumn conference in 1985 also had a conservation theme, “Soils, flora and fauna.” Scientists claimed that different guidelines for RF should be developed for different forests (S 1986:1:56–57). In addition, threatened forest flora and fauna was a theme during “the forestry week” (an annual gathering for foresters), in the spring of 1986 (S 1986:3:12–13; 16–18).

RF instructions

During the late 1980s, instead of regarding conservation issues only as an information problem, forestry companies started producing instructions for their employees to improve conservation efforts and training their staff accordingly (SN 1987:6:23). Some of the instructions were general, whilst others were more specific (S 1986:9:59; S 1987:8:59). For instance, the Iggesund Company's instructions stated that all snags and high-stumps should be retained, if present, and if neither were present at least one large living tree per three hectares should be retained (S 1987:7:40). In the mid-1980s, the SSNC initiated detailed examinations of forestry companies' specific conservation efforts (SN 1986:1:32–33; SN 1990:2:14–16). One criticism was that the companies' “conservation brochures are lavishly produced, but are more of a display window than useful handbooks for their staff” (SN 1988:3:27–30). Furthermore, there was criticism that employees were not informed about why conservation work should be performed and that “companies are still nowhere close to fulfilling the minimum requirements of §21 of the Forestry Act. This is thirteen years after the demand for nature consideration was introduced in the first paragraph of the Forestry Act” (S 1988:8:62–63). The SSNC intensified their criticism of the Swedish Forestry Act during the end of the 1980s and produced a new declaration in 1988 demanding extensive improvements to the legislation and highlighting the need for “binding rules with the opportunity to apply sanctions if §21 is to have the intended effect” (SN 1988:2:27–28).

RF, reserves or clear-cut free forestry?

Following increases in awareness of the negative impacts of clear-cut forestry on a large number of plants and animals various possible strategies to mitigate species depletion were discussed, such as setting aside large forest areas as reserves, conversion to clear-cut free forestry or implementation of RF. The optimal strategy to adopt was discussed during most of the studied period (e.g. S 1981:5–6:118–120). As early as 1974, before the development of RF, a professor of botany, Hugo Sjörs, suggested that RF should be introduced, because the alternative “would be setting aside a large proportion of our forests as nature reserves, which would probably be less appealing to forestry than self-imposed restrictions” (S 1974:1:7).

Demands for more forest reserves were made in 1976 by a representative of the SSNC, who argued that many species were so sensitive that RF would not be sufficient (SN 1976:5:205–209). In 1982 the same representative wrote that reserves and RF should be regarded as complementary, rather than competing, methods. However, he was critical of the Forestry Act, which he thought caused more harm than good because it was used by forest-owners to argue that forest reserves were unnecessary (SN 1982:3:32–34). The Director of the Swedish Forest Agency, Björn Hägglund, clearly stated in 1985 that RF should be the main route to follow and said in an interview that “We will adapt forestry methods, not fix them over large areas. Consideration of nature and recreation does not cost much…. It is refraining from forestry that costs” (SN 1985:6:20–23). Even the chairman of SSNC maintained that RF was important, since reserves would only cover “a fraction of forestland” (S 1986:8:55). Wildlife scientists repeatedly stressed that RF would not be sufficient but must be complemented with reserves (e.g. S 1989:9:62).

A forest production scientist warned about the idea of implementing clear-cut free forestry as clear-cutting had been proven to be better than selective logging as far back as 1914 (S 1992:4:24–26). The rationale was that clear-cutting with RF and generous set asides was preferable to “nature-adapted forestry” (S 1992:8:42).

A Richer Forest

In a long interview in Sveriges Natur, the newly appointed Director of the Swedish Forest Agency, Björn Hägglund, pointed out that there is an intrinsic conflict between forestry and conservation, which had been generally denied by foresters previously (SN 1985:6:20–23). He also stressed the importance of training staff to be aware of conservation issues. By the late 1980s there was political pressure to increase conservation ambitions and the Swedish Forest Agency commenced an extensive education campaign in 1989 called “A Richer Forest” (S 1989:2:4; S 1990:9:16–18). A book with the same title (The National Board of Forestry Citation1992) was published and was reviewed in Sveriges Natur under the heading “Better late than never”, in which the reviewer pointed out that the training book had only appeared 10 years after incorporation of §21 in the Forestry Act (SN 1991:1:60). The forestry sector's own research foundation started work on conservation issues during the late 1980s that resulted in a book about RF (Aldentun et al. Citation1991) and the provision of courses in RF (S 1990:9:64). The foundation considered that good harvest planning, clear responsibilities and sound biological knowledge were essential for good RF (S 1990:10:50). During the “forestry week” in 1991 forestry consideration towards red-listed species (threatened species in forest ecosystems) was discussed and participants from forestry, scientific research and conservation organisations agreed that complete preservation of species was impossible. During the meeting a professor of botany, Lars Ericson, stated that for readily-dispersed species “the nature consideration rules were an important tool … for instance the retention of ten large trees per hectare during clear-cutting” (S 1991:4:14–15).

1991–2003: threats of boycotts and forest certification

A new forestry policy

A committee was appointed in 1990 to investigate forestry policy and presented a report in 1992 (S 1992:8:6; SN 1992:5:15). The report recommended extensive changes in forestry policy and forestry legislation. Parliament had already issued a statement in 1991, containing the following overall target: “The biological and genetic diversity shall be secured. Plant and animal communities shall be preserved so that naturally occurring species shall be provided the conditions to survive in viable populations” (SN 1992:5:11). Before the target and associated clauses were incorporated in revisions to the Forestry Act the SSNC suggested that stricter and more biologically functional general regulations about nature consideration should be included. Furthermore, there were demands for conservation regulations with penalties, and changes in compensation rules for forest-owners (SN 1992:2:13). A new Forestry Act came into force in 1994, giving environmental and production goals equal importance. Many of the detailed regulations concerning timber production were removed, and regulations concerning RF were given a clear orientation towards preservation of plants and animals.

The new Forestry Act stipulated that RF should be applied on all clear-cuts. Shortly after its publication there was criticism from some foresters about this, with suggestions that conservation efforts should be focused on some areas, whilst others should be used for intensive plantation forestry (S 1996:4:52). In contrast, the Swedish Forest Agency stated that it is better to use a model combining forestry and conservation in all stands with additional protection in reserves (S 1996:9:51).

Red-listed species

A list of threatened species in Sweden (vertebrates) was published in 1975 (SNA 1975:126–129) and a pilot project partly financed by the WWF, involving establishment of a dedicated Threatened Species Unit based at SLU (S 1985:2:56), was initiated in 1984. However, in 1991 the Unit became a formally integrated part of SLU (SN 1993:2:24–25), one of its most important tasks being to spread knowledge about the occurrence of red-listed species, and throughout the 1990s the focus on red-listed species in forestry conservation efforts intensified.

Gradually knowledge about red-listed species occurrences and requirements increased. A series of articles was published on the subject in Skogen (e.g. S 1993:4:36–38). For instance, in northern Sweden 37% of the red-listed species were reportedly associated with downed dead wood (S 1993:5:62–63). An analysis of all 1500 of Sweden's red-listed forest species indicated that 25% would survive clear-cutting if RF was applied (S 1995:12:30–32). In Sveriges Natur there were regular articles about threatened species. Notably, a thematic issue focused on “Diversity,” which highlighted among other things the importance of retaining dead trees for many beetle species (SN 1991:6: 46–47). The strong focus on red-listed species and the debate about environmental requirements of species resulted in several major forestry companies employing biologists to develop conservation practices (e.g. S 1995:10:46–47).

A new measure that was introduced in the mid-1990s, mainly to benefit beetles, was the creation of high-stumps by cutting trees at a height of 4–5 m, which was questioned by many foresters (S 1996:1:45; S 1997:4:5).

Boycotts from abroad

In1991 Swedish ENGOs started to stir opinion in Europe against Swedish forestry. Harvesting of montane forests had been a contentious issue since 1978 when the Swedish Forest Service shifted a border, beyond which no large-scale timber harvesting had been permitted, further towards the Scandes Mountains (SN 1978:1:28). One ENGO, FURA (Fjällnära Urskogars Räddningsaktion, in Swedish) called for a boycott of products from forest companies that operated in montane forests. In a letter to these companies it was stated that the threat of boycott would remain until the companies had ceased to harvest these low-productivity forests (S 1991:11:8–9). The threat had the desired effect and an editorial in Skogen asked how “contagious the decision to yield to the threat of boycott would be?” (S 1992:2:7).

In 1993 the German branch of Greenpeace demanded “clear-cut free paper” (S 1993:10:11; S 1994:1:6–8) and received support from Axel Springer's publishing group in Germany, a major purchaser of printing paper from Sweden. The following discussions between forestry companies and German paper buyers led to some of the latter withdrawing demands for clear-cut free forestry “provided that forest diversity of plants and animals is not affected” (SN 1994:2:62). Springer's environmental director said “In the future we will support the suppliers who care for species protection and biodiversity” (S 1994:1:6–8). During the following years several articles were published about the international criticism of Swedish forestry. Concerning RF in Swedish forestry Sveriges Natur wrote that “more has happened since 1991 than after years of domestic debate” (SN 1994:5:55–58). Greenpeace had not anticipated the response and concern in Sweden. One representative said that their campaign had mostly been focused on Canadian forestry (S 1994:9:26).

A press conference hosted by the SSNC during the UN meeting in Rio de Janeiro 1992 received substantial attention when representatives claimed that the Swedish forestry model transformed forests into plantations and exterminated plants and animals (SN 1992:4:54–55). This action prompted the following comment from the Swedish King, who attended the meeting, “What does the SSNC mean? This sounds mad. Swedish forestry is outstanding” (S 1992:6–7:6–8).

“New Forestry”

The first article in the analysed magazines about the concept of “New Forestry” in the USA was published in 1991 when Professor Jerry Franklin visited Sweden and he was very critical of Swedish forestry legislation (SN 1991:6:66–67). A conflict about a threatened species in the USA, the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), led to extensive restrictions on forestry (S 1993:8:17–18). This conflict and development of the “New Forestry” concept led Swedish foresters to visit the USA, where it was first introduced and learn about the American debate and actions (S 1991:12:50–52). In an interview Franklin stated that “There is no fundamental difference between ‘New Forestry’ and your Swedish campaign for Richer Forests” (S 1993:8:20). Swedish scientists agreed (S 1993:8:22).

International forestry certification

Work towards international forestry certification commenced in the early 1990s. In 1993 a working group was commissioned by the WWF to formulate a Swedish FSC standard (S 1993:11:50–51), and in 1995 the SSNC and WWF presented outlines for a Swedish standard (SN 1995:4:43). A broad working group was established in 1996, including representatives of private forest-owners, forestry companies, the wood-processing industry, unions, the indigenous Sami people and various ENGOs (SN 1996:2:56). A draft for a Swedish FSC standard was completed in 1997 and an SSNC representative said, “We have certainly had to compromise on some issues, but we have still received more than we have given away” (SN 1997:5:16). One of the most important achievements of the SSNC was the incorporation of more comprehensive RF requirements in the FSC standard than the forest-owners wanted, including the creation of high-stumps and retention of at least 10 living trees per hectare on average, all large and old trees and all dead wood. Sveriges Natur published an article on one of the first FSC-certified Swedish clear-cuts, in which an SSNC representative stated that the FSC standard had raised the bar for RF (SN 1998:1:12–14). The Forest Owners' Association withdrew from the FSC process in 1997 as they regarded the requirements as too high. They accused the FSC of being appropriate for tropical conditions but not relevant for Nordic conditions (S 1997:8:20–21). Together with other European private forestry actors but without the participation of ENGOs, they subsequently established the competing environmental certification system PEFC (S 1999:5:78).

The SSNC scrutinised some of the first FSC-certified clear-cuts and was critical of several aspects, especially the small numbers of field controls during audits (SN 2000:1:20–25). A more extensive follow-up, by both the WWF and the SSNC, highlighted deficiencies in the retention of dead wood and trees with high biodiversity value. However, the WWF still believed that FSC certification had led to significant changes (SN 2002:2:64). In 2001, a member of the SSNC claimed that the FSC restrained the Society “But if the forest has gained from FSC, we have made a great loss. A weapon has been removed from our hands. As SSNC supports the FSC, we cannot criticise the FSC-labelled forest-owners openly any more” (SN 2001:3–4:96).

Discussion

Driving forces

Identification of driving forces is important for elucidating the conceptual origins, temporal shifts in attitudes towards and implementation of changes in land-use and land management. These may include highly interactive societal factors, such as economic pressures, aesthetic values, other concerns of the public and or specific interest groups and policy (Hersperger et al. Citation2010). There have been few analyses of driving forces related to forestry management models, although Bürgi and Schuler (Citation2003) examined causes of changes in the extent of artificial regeneration practices and associated shifts in the species composition of stands in Switzerland. However, since forestry and forest management have almost invariably involved diverse interest groups (in various ways), rather than only a narrow sector, in our opinion it is valuable to analyse changes by identifying broad drivers of change. In our search for explanations for the development of RF in Sweden we identified six possible national and international driving forces: (1) widespread criticism of clear-cutting from ENGOs and the public during the 1970s, (2) lists of threatened species, (3) forestry concern about severe political restrictions on forestry, (4) demands from foreign customers initiated by ENGOs, (5) influences of “New Forestry” and (6) forestry certification (). The drivers, debate and activities concerning RF have varied over time, as further discussed below, and several more or less distinct periods can be distinguished ().

Widespread criticism from ENGOs and the public

The initial driving force was the widespread criticism of clear-cuts, which were perceived as large and ugly by the public and ENGOs in the 1970s (see also Gulbrandsen Citation2005a; ). Clear-cutting had been successively taking over as the main logging method in the preceding decades (Lundmark et al. Citation2013), and clear-cuts became much larger and therefore much more visible during the 1960s and the 1970s. Criticism of forestry also frequently appeared in the daily press, primarily triggered by protests against herbicide spraying.

The SSNC did not present precise demands for RF in the 1970s, but wanted to limit the size of clear-cuts to 5–20 ha, with as much environmental consideration as possible during harvests (Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen Citation1978). However, the SSNC presented clear demands regarding forestry methods, seeking the prohibition of practices such as e.g. forest fertilisation.

The debate among politicians about clear-cutting initially appeared to have mostly ended when the working group commissioned by the government to investigate clear-cutting presented its report in 1974, concluding that clear-cutting was an appropriate forestry method (Jordbruksdepartementet Citation1974). In the referral process – a specific Swedish form of stakeholder response to governmental investigations Trädgårdh (Citation2007) – the SSNC indicated that they accepted clear-cutting as a forestry method. Enander (Citation2007) maintains that this SSNC position was highly important for subsequent forestry debate.

Foresters and conservation groups clearly did not understand each other, as there was a clear absence of constructive dialogue in the 1970s and early 1980s. Indeed, Lisberg Jensen (Citation2002) describes the discussion at this time as “non-communication” (p. 138). Foresters were hurt by the harsh criticism, and regarded themselves as successful men of the modern new age, as they turned sparse old forests into dense fast-growing plantations. Lisberg Jensen (Citation2011) notes that “Clear-felling became an expression of modernity” (p. 423). Thus, forestry forced opponents to argue for the opposite, i.e. defend the “old.” This had two consequences: it provoked a harsher debate and forced the conservationists to be more precise. Clear parallels can be drawn with a current discourse in Sweden on the introduction of more intensive forestry, in which widely divergent values among stakeholders, rather than a weak knowledge base, is a main explanation of conflicts (Lidskog et al. Citation2013).

Lists of threatened species

The second driver was the compilation of Red Lists. During the 1970s foresters perceived the criticism of clear-cut forestry to be diffuse, with mixed arguments, many of which they considered based on sentiment rather than logic. Then suddenly, conservationists started providing detailed lists of threatened species and pointing out actual occurrences in the forest. This was a new, and uncomfortable, experience for the foresters. The focus of the debate shifted from the previous aesthetic concerns during the 1970s (and in the 1979 Forestry Act), towards flora and fauna conservation and threatened species. A basis for this development was the systematic mapping of threatened species and compilation of Red Lists, mostly by SLU researchers, who also produced several handbooks on flora and fauna conservation, issued by the Forest Agency (e.g. Ingelög Citation1981; Ehnström & Waldén Citation1986). For instance, 5 editions and 29,000 copies of a book on fauna conservation in forestry (Ahlén et al. Citation1979) were printed between 1979 and 1986. When the Threatened Species Unit was formed at SLU in 1984, the compilation of Red Lists became more extensive and permanent (Ingelög Citation2008), involving increased efforts to map and evaluate species and threats.

The lists of threatened species became important drivers and effective tools for the criticism of forestry from the early 1980s until the end of the study period, and led to demands for more extensive RF, more voluntary set asides and more nature reserves (Lindahl Citation1990). In the late 1980s, ENGOs began to use some red-listed species as “indicator species” for high conservation value forests (Karström Citation1992), and later authorities also adopted the use of such species in nature conservation work (Olsson Citation1993). Many of the “indicator species” were considered to reflect forests with “long stand continuity” (Karström Citation1992), a link which has been questioned by among others (Ohlson et al. Citation1997).

The conservation work had a very strong focus on red-listed species during the 1990s while ecosystem function (Mooney & Schulze Citation1993) was not an important issue that time. The interest in threatened species was influenced by increased international activities in the compilation of Red Lists during the 1970s, not only globally but also nationally (Scott et al. Citation1987). The term biodiversity (“biologisk mångfald” in Swedish) came into use in the debate, being used in Sveriges Natur for the first time in 1987 (SN 1987:4:18–19). Lisberg Jensen (Citation2002) claims that the term biodiversity strongly influenced the debate as it bridged a gap between conservationists and foresters.

Forestry concern about severe political restrictions

The third main driver we have identified is the forestry sector's concern about severe political restrictions. The sector could not ignore scientific arguments against clear-cutting based on red-listed species (see also Elliott & Schlaepfer Citation2001). When foresters gradually recognised the problem that clear-cut forestry negatively affected flora and fauna, in the late 1980s, we conclude that they made a conscious decision to introduce RF on a larger scale. They hoped that this would avoid severe forestry restrictions by political decisions that might demand other management systems or obligations to sell large forest areas as nature reserves. As early as the 1970s, Åsa Moberg, a columnist in one of Sweden's largest newspapers, demanded several times that legislation against clear-cutting should be introduced (Enander Citation2007), and in 1978 the SSNC demanded that timber should be harvested using selective logging (Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen Citation1978). The director of the Swedish Forest Agency, Björn Hägglund, clearly stated in 1985 that RF was considerably better for forestry than exempting large areas from forest management, which would impose considerably more restrictions and incur considerably more costs for both the forestry industry and the state. He also reacted in 1985 to the harsh debate by urging foresters to change their attitude towards conservation and listen to conservationists' criticisms. Bush (Citation2010) highlights this as an important event. Instead of denying the conflict between forestry and conservation, as foresters had previously done, Hägglund admitted that there was an inherent conflict of interest. The attitude towards conservation was probably also generation-related. Older foresters found it difficult to absorb the conservation ideas.

At the end of the 1980s forestry companies started participating in RF education, producing their own RF instructions and implementing RF to a greater degree instead of regarding conservation as an information problem. This was an important development, as efficient dissemination of results from researchers to managers greatly facilitates the adoption of sustainable forestry practices (Farrell et al. Citation2000). Various educational materials regarding stand-adapted forestry and conservation of flora and fauna were also summarised in the book “A Richer Forest” (The National Board of Forestry Citation1992), of which 72 000 copies were printed, and a major study campaign was initiated for both forest-owners and forestry officials. Handbooks on flora and fauna conservation as well as the campaign “A Richer Forest” provide good illustrations of the communication of evidence-based messages about RF to practical foresters during this time. It is worth noting that this type of education provides advice to participants and increases their awareness but does not reportedly alter their basic values (Hysing & Olsson Citation2005).

Demands from foreign customers initiated by ENGOs

The fourth main driver was the strident demand from European customers in the early 1990s for more environmentally–friendly forestry, especially clear-cut free harvesting systems, initiated by ENGOs. Elliott and Schlaepfer (Citation2001) point out that Swedish ENGOs cooperated with their international colleagues to lobby retailers and corporate customers in several countries, e.g. UK and Germany. Simply threatening to boycott Swedish products resulted in complete cessation of harvesting montane forests. This was a major achievement for the ENGOs, which then started to work with one of Europe's largest paper purchasers, Springer Verlag. Seeing one of their major clients sit next to Greenpeace representatives at a press conference and demand “clear-cut free paper” was a completely new and uncomfortable experience for the forestry industry (Klingström Citation2012).

Influences of “New Forestry”

The developments in Sweden occurred in parallel to similar developments in the Pacific Northwest region of the USA. During the early 1990s debate in the USA focused on cutting of old-growth forests and the introduction of RF was advocated as a part of a solution to this, and associated problems, as part of the “New Forestry” concept. The starting point for the concept was realisation of the importance of biological legacies for post-disturbance succession, together with studies of the processes and structures in old-growth forests. The aim was to integrate consideration of such components into forest management in order to make forests more complex (Franklin Citation1989; Swanson & Franklin Citation1992). Land-use conflicts seem to have been key factors driving the development of RF in North America (Swanson & Franklin Citation1992). The government of British Columbia, Canada, appointed a Scientific Panel for Sustainable Forest Practices in Clayoquot Sound after mass demonstrations against clear-cuts. The panel introduced the term “variable retention” and suggested it was the most appropriate harvest practice (Mitchell & Beese Citation2002; Bunnell et al. Citation2009). “New Forestry” received great attention in Sweden and several Swedish foresters visited the Pacific Northwest region and were impressed by what they saw. Professor Franklin also visited Sweden. We therefore consider that the “New Forestry” concept inspired both scientists and foresters to develop RF in Sweden, thus it can also be considered as a driving force, though weak.

The main motives for Swedish efforts to develop and implement RF initially were aesthetic considerations, but focus on structures and biotopes that are important for threatened species (e.g. old pines for eagles to nest in, old deciduous trees that support lichens and groups of aspens for invertebrates) grew successively stronger during the 1980s. We regard the development of RF in the USA and Sweden as having different starting points and evolving independently until the early 1990s but with similar outcomes. According to Gustafsson et al. (Citation2012), the development of RF in north-western North America started about 25 years ago, based on recognition of the importance of mimicking natural disturbance dynamics in production forestry, including biological legacies and spatial heterogeneity. However, our analysis indicates that the RF concept first emerged in Sweden in the early 1980s, based on concerns for threatened species, although the importance of mimicking natural disturbance processes, as fire (Zackrisson Citation1977), also provided strong arguments for RF during the 1990s (e.g. Fries et al. Citation1997; Angelstam Citation1998).

Sweden was the first country to introduce RF in north Europe, and subsequent RF development in neighbouring countries, e.g. Finland and the Baltic States, very likely largely rested on Swedish experiences. In Finland leaving retention trees in clear-cuts started in the late 1980s and in the mid-1990s several forestry organisations included retention recommendations (J. Kouki, personal communication). RF was introduced on a larger scale by PEFC certification in 1999, although the retention of trees is not required by law in Finland. In Latvia and Lithuania RF was introduced in the late 1990s (J. Priednieks and D. Stoncius, personal communication), and the Estonian Forest Act has required the retention of live and dead trees since 1999 (Rosenvald Citation2008).

Forest certification: FSC and PEFC

The sixth and final driving force identified in our analysis is forest certification, which is strongly linked to the fourth driver “Demands from foreign customers initiated by the ENGOs”. Market demands were major reasons why Swedish forestry organisations joined the two international forestry certification systems, FSC and PEFC (whose standards clearly state requirements for RF) in the late 1990s. Overall, forest certification in Sweden was strongly influenced by international processes like the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992, which put biodiversity on the global agenda (Boström Citation2003). Certification is usually regarded as a market-driven system, but underlying the certification demands from the forest product customers were often demands from various ENGOs, e.g. the WWF (Cashore et al. Citation2004; Gulbrandsen Citation2005b; Johansson Citation2013). When an FSC working group with no forestry representatives presented a draft for a Swedish FSC standard in 1995, Cashore et al. (Citation2004) described the situation as follows: “Now Swedish industrial forest companies and forest landowners faced a clear choice: participate with the FSC and earn market recognition, or refuse to participate and face increasing boycotts and international scrutiny” (p. 201).

Environmental organisations directly influenced the formulation of RF practices specified in the FSC standard by participating in relevant working groups. At the time of its introduction, Elliott (Citation1999) even argues that the agenda of the working groups was largely determined by the ENGOs. This has further prompted scholars to suggest that the FSC's decision-making process, in which representatives from ENGOs, social organisations and the economic sector have equal voting rights and weight, may result in democratic and inclusive decision-making (Auld & Gulbrandsen Citation2010; cf. Johansson Citation2013). In the 1980s the Swedish Forest Agency played a significant role through educational efforts, advice and drafting guidelines for implementing RF. However, the FSC explicitly excludes governmental authorities and political parties from the decision-making process, and the Forest Agency lost its leading role when it was not included in the FSC working groups that formulated RF guidelines for certification. Thus, the Agency was excluded from the development of RF within certified forestry (Hysing Citation2009).

Trade-offs between RF and reserves

Both in Sweden and internationally the traditional way to consider conservation interests was to separate conservation areas from productive forestry areas by creating reserves and applying intense forestry without RF in the remainder (e.g. Lindenmayer & Franklin Citation2002). Leading up to the Swedish forestry policy of 1993 a working group linked to the forestry policy committee presented a study on the need for reserves, assuming that RF would be implemented according to norms of the time and the ambition to preserve biodiversity (SOU Citation1992b). The group concluded that 15% of the productive forestland would need to be set aside as reserves. The forestry policy committee discussed various solutions, such as completely separating production areas and conservation areas, or applying more comprehensive RF on all forestland and only setting aside limited reserves (SOU Citation1992a). Their report recommended the latter and the new Forestry Act set production and environmental objectives as equally important. The political decision to apply RF on all forestland instead of comprehensive reserves seems rational as purchasing land for reserves would be very expensive for the state. Instead, the politicians placed much of the responsibility for conservation on forest-owners, who were expected to carry the costs of RF without compensation from the government. The principle of sectorial responsibility of forestry had been passed in parliament in 1988 (Bush Citation2010), and was consistent with the extended producer responsibility (Lindhqvist Citation2000) developed for industry. Since RF was also developing in other countries (see above), the political decision was also in line with prevailing ideas of the time. During the 1990s the “Swedish model,” a multi-scaled model for biodiversity conservation, gradually developed (Gustafsson & Perhans Citation2010).

There was some criticism from the SSNC of claims by forest-owners that reserves were unnecessary, and cutting forests with high conservation value was justified, if forests were managed with RF. In support of this criticism, Lindenmayer et al. (Citation2012) maintain that arguments for RF do not justify logging in high conservation forests and Gustafsson et al. (Citation2012) state that RF cannot replace the need for reserves.

Breakthrough for RF

The identified driving forces and various activities, such as education campaigns and the development of relevant company-specific instructions led to a breakthrough for RF in the mid-1990s (). Other important factors included: (1) increased public awareness of biodiversity, partly due to the Rio conference in 1992, (2) new national estimates of timber supply and demand, together with increases in imports from the former Soviet Union, leading to the forestry industry seeing a “timber mountain” instead of a “timber depression” (S 1992:6–7:20–22) and (3) the stronger emphasis on biodiversity, including more specific retention requirements in the new Forestry Act. Some scientific studies have assessed and quantified changes in forest structures due to RF during our study period. A significant increase in frequencies of broadleaved retention trees with high conservational values, attributed to education and advice, between 1985 and 2000 was reported by Götmark et al. (Citation2009). Similarly, Kruys et al. (Citation2013) reported a 70% increase in amounts of dead wood on new clear-cuts between 1997 and 2007, as well as considerable increases in frequencies of retained living trees between 1980 and 2007.

Our study period ends in 2003, but we maintain that no major changes in RF practices have occurred during the last decade. Much of the ongoing development of RF today is determined by the certification systems. For instance, the FSC standard is negotiated during three-party negotiations involving representatives of environmental, social and economic interest groups. Hence, the process is often slow. In recent years a new debate has started in Sweden, in which forestry has been criticised for lack of consideration towards aesthetic and recreational interests and for having neglected humans in favour of red-listed species (Zaremba Citation2012). Considering the current debate our assessment is that the focus on recreational aspects of RF will increase in coming years, which is interesting since aesthetic impairment of the landscape by clear-cutting was a main argument for the introduction of RF in Sweden in the 1970s.

Methodological considerations

This study is based on a systematic analysis of historical documents published by two NGOs, both of which have played very important roles in the course of events described and discussed in this study. Thus, the core of the study is based on historical sources and source criticism must be applied (Östlund et al Citation1997; Ernst Citation2000). The origins of the sources are clear, but their quality (factual arguments vs. unverified opinions) varies considerably since each article was written by a different author (although some authors made multiple contributions during the study period). This problem is here reduced by acknowledging the authors and their status, indeed one of the main aims of the study is to document the width of this debate and contrast opposing views on the same topic.

A major strength of this type of analysis is the extensive, detailed and consecutive nature of the sources used, the weakness is that the sources are biased, reflecting opinions of the two organisations (and their individual representatives). A further strength is that it enables the progress of RF, and details of its development, to be analysed on a yearly basis, and precise details of its development and the debate to be described clearly. It has also allowed us to discern the arguments and relate the story of one of the most dramatic periods of Swedish forest history, the paradigm shift from modern forestry to post-modern forestry, and thus put “flesh on the carbon based bones of forest history” (cf. Williams Citation2000). To limit the problem of bias, we have also contrasted our sources with other relevant information from contemporary literature and more recent studies on this topic.

Conclusions

We have identified six main driving forces for RF development in Sweden (). The debate about clear-cuts started suddenly in the early 1970s, after previously being a non-issue. The origin of RF lies in attempts to mitigate this criticism of clear-cuts and increase public acceptance by retaining trees and tree groups. In the mid-1970s scientists and environmental organisations provided increasing evidence that clear-cuts had negative effects on certain plants and animals, thereby advocating RF from a conservation perspective. The development of RF can be separated into several more or less distinct periods, from strong debates and conflicts during the 1970s until the breakthrough of forestry certification at the turn of the millennium (). We conclude that the development of RF in Sweden was harmonised with similar developments in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, but certain aspects emerged earlier in Sweden. The answer to our final question, i.e. the reason for choosing RF as a tool for forest conservation rather than creating large forest reserves, is probably that the cost of improving conservation could be distributed among numerous land-owners instead of being borne solely by the Swedish state.

Our analysis clearly shows that the further development of RF in Sweden was affected by several interacting driving forces. Despite a lack of systematic methodology for assessing the relative importance of such forces (Hersperger & Bürgi Citation2009), in our case we find strong support for the hypothesis that the main one was concern for threatened species. This is because the compilation of Red Lists offered a new instrument for environmentally oriented actors to demonstrate concrete effects of forestry on biodiversity, from national to stand level. These lists strongly affected both the public debate and the drivers “forestry concerns about severe restrictions on forestry” and “demands from foreign customers.” During the last 10-year period, from 2003 to 2013, RF practices have become consolidated and the rate of change in policy and practice has decreased, although some legislative changes have been recently suggested. ENGOs, and to a certain extent the forestry authorities, still criticise the quality and quantity of the practical implementation of RF, thus a discussion is still ongoing, but increasingly in the form of dialogue between the actors. We argue that studies of shifts in societal values and consequent forest management practices are important because they can elucidate why changes occur and facilitate attempts to understand the dynamic nature of forests ecosystem in modern societies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hanna Lundin for scrutinising all the issues of the two journals. We also thank Anna-Maria Rautio and Gudrun Norstedt for helpful discussion and comments on this manuscript and Mick Bobik for help with .

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahlén I. 1977. Faunavård [Fauna conservation]. Stockholm: LiberFörlag.

- Ahlén I, Boström U, Ehnström B, Pettersson B. 1979. Faunavård i skogsbruket [Fauna conservation in forestry]. Jönköping: Skogsstyrelsen.

- Aldentun Y, Drakenberg B, Lindhe A. 1991. Naturhänsyn i skogen [Nature conservation in forestry]. Kista: Forskningsst. Skogsarbeten.

- Angelstam P. 1998. Maintaining and restoring biodiversity in European boreal forests by developing natural disturbance regimes. J Veg Sci. 9:593–602. 10.2307/3237275

- Angelstam P. 2003. Forest biodiversity management – the Swedish model. In: Lindenmayer DB, Franklin JF, editors. Towards Forest Sustainability. Collingwood: CSIRO; p. 143–166.

- Anshelm J. 2004. Det vilda, det vackra och det ekologiskt hållbara. Om opinionsbildningen i Svenska Naturskyddsföreningens tidskrift Sveriges Natur 1943-2002 [The wild, the beautiful and the ecologically sustainable. The moulding of public opinion in the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation's magazine Sveriges Natur 1943-2002]. Umeå: Umeå universitet.

- Aubry KB, Halpern CB, Peterson CE. 2009. Variable-retention harvests in the Pacific Northwest: a review of short-term findings from the DEMO study. For Ecol Manage. 258:398–408. 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.03.013

- Auld G, Gulbrandsen LH. 2010. Transparency in nonstate certification: consequences for accountability and legitimacy. Glob Environ Polit. 10:97–119. 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00277.x

- Boström M. 2003. How state-dependent is a non-state-driven rule-making project? The case of forest certification in Sweden. J Environ Policy Plan. 5:165–180. 10.1080/1523908032000121184

- Brandt J, Primdahl J, Reenberg A. 1999. Rural land-use and dynamic forces – analysis of “driving forces” in space and time. In: Krönert R, Baudry J, Bowler IR, Reenberg A, editors. Land-use changes and their environmental impact in rural areas in Europe. Paris: UNESCO; p. 81–102.

- Bunnell FL, Beese WJ, Dunsworth GB. 2009. The example – social and historical contexts. In: Bunnell FL, Dunsworth GB, editors. Forestry and biodiversity. Learning how to sustain biodiversity in managed forests. Vancouver: UBC Press; p. 26–28.

- Bürgi M, Hersperger AM, Schneeberger N. 2004. Driving forces of landscape change – current and new directions. Landscape Ecol. 19:857–868.

- Bürgi M, Schuler A. 2003. Driving forces of forest management – an analysis of regeneration practices in the forests of the Swiss Central Plateau during the 19th and 20th century. For Ecol Manage. 176:173–183.

- Bush T. 2010. Biodiversity and sectoral responsibility in the development of Swedish Forestry Policy, 1988–1993. Scand J Hist. 35:471–498. 10.1080/03468755.2010.528249

- Cashore B, Auld G, Newsom D. 2004. Governing through markets – forest certification and the emergence of non-state authority. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

- Ehnström B, Waldén H. 1986. Faunavård i skogsbruket. Del 2 – Den lägre faunan [Conservation of invertebrates in forestry]. Jönköping: Skogsstyrelsen.

- Elliott C. 1999. Forest certification: analysis from a policy network perspective [doctoral dissertation] Lausanne: Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne.

- Elliott C, Schlaepfer R. 2001. The advocacy coalition framework: application to the policy process for the development of forest certification in Sweden. J Eur Public Policy. 8:642–661. 10.1080/13501760110064438

- Enander KG. 2007. Skogsbruk på samhällets villkor [Forestry on society's conditions]. Umeå: SLU, Institutionen för skogens ekologi och skötsel.

- Ernst C. 2000. How professional historians can play a useful role in the study of an interdisciplinary forest history. In: Agnoletti M, Andersson S, editors. Methods and approaches in forest history. New York (NY): CABI; p. 29–34.

- Farrell EP, Führer E, Ryan D, Andersson F, Hüttl R, Piussi P. 2000. European forest ecosystems: building the future on the legacy of the past. For Ecol Manage. 132:5–20. 10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00375-3

- Fedrowitz K, Koricheva J, Baker SC, Lindenmayer DB, Palik B, Rosenvald R, Beese W, Franklin JF, Kouki J, Macdonald E, et al. 2014. Can retention forestry help conserve biodiversity? A meta-analysis. J Applied Ecol. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12289

- Franklin JF. 1989. Towards a new forestry. Am Forests. 95:37–44.

- Franklin JF. 1993. Preserving biodiversity: species, ecosystems, or landscapes? Ecol Appl. 3:202–205.

- Franklin JF, Berg DR, Thornburgh DA, Tappeiner JC. 1997. Alternative silvicultural approaches to timber harvesting: variable retention systems. In: Kohm KA, Franklin JF, editors. Creating a forestry for the 21st century: the science of forest management. Washington (DC): Island Press; p. 111–139.

- Fries C, Johansson O, Pettersson B, Simonsson P. 1997. Silvicultural models to maintain and restore natural stand structures in Swedish boreal forests. For Ecol Manage. 94:89–103. 10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00003-0

- Geist HJ, Lambin EF. 2002. Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. BioScience. 52:143–150. 10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0143:PCAUDF]2.0.CO;2

- Gulbrandsen LH. 2005a. The effectiveness of non-state governance schemes: a comparative study of forest certification in Norway and Sweden. Int Environ Agreem: Polit, Law Econ. 5:125–149. 10.1007/s10784-004-1010-9

- Gulbrandsen LH. 2005b. Explaining different approaches to voluntary standards: a study of forest certification choices in Norway and Sweden. J Environ Policy Plan. 7:43–59. 10.1080/15239080500251874

- Gustafsson L, Baker SC, Bauhus J, Beese WJ, Brodie A, Kouki J, Lindenmayer DB, Lõhmus A, Martínez Pastur G, Messier C, et al. 2012. Retention forestry to maintain multifunctional forests: a world perspective. BioScience. 62:633–645. 10.1525/bio.2012.62.7.6

- Götmark F, Fridman J, Kempe G. 2009. Education and advice contribute to increased density of broadleaved conservation trees, but not saplings, in young forest in Sweden. J Environ Manage. 90:1081–1088.

- Gustafsson L, Kouki J, Sverdrup-Thygeson A. 2010. Tree retention as a conservation measure in clear-cut forests of northern Europe: a review of ecological consequences. Scand J For Res. 25:295–308. 10.1080/02827581.2010.497495

- Hersperger AM, Bürgi M. 2009. Going beyond landscape change description: quantifying the importance of driving forces of landscape change in a Central Europe case study. Land Use Policy. 26:640–648. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.08.015

- Hersperger AM, Gennaio M, Verburg PH, Bürgi M. 2010. Linking land change with driving forces and actors: four conceptual models. Ecol and Society. 15:1–17.

- Hysing E. 2009. Governing without government? The private governance of forest certification in Sweden. Public Admin. 87:312–326. 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01750.x

- Hysing E, Olsson, J. 2005. Sustainability through good advice? Assessing the governance of Swedish forest biodiversity. Environ Polit. 14:510–526. 10.1080/09644010500175742

- Ingelög T. 1981. Floravård i skogsbruket. Del 1 – Allmän del [Flora conservation in forestry – General section]. Jönköping: Skogsstyrelsen.

- Ingelög T. 2008. Artdatabanken – en resa från 70-talets kalhyggesdebatt till dagens Nationalnyckel [The Threatened Species Unit – a journey from the 70s clear-cut debate to today's Encyclopedia of the Swedish Flora and Fauna]. In Ramberg G, editor. SLU – Tre decennier mitt i samhällsutvecklingen [SLU – Three decades in the center of the societal development]. Uppsala: SLU; p. 257–269.

- Johansson J. 2013. Constructing and contesting the legitimacy of private forest governance: the case of forest certification in Sweden [Doctoral dissertation]. Umeå: Umeå University.

- Jordbruksdepartementet. 1974. Kalhyggen [Clear-cuts]. Ds Jo. 1974:2.

- Karström M. 1992. Steget före – en presentation [The project one step ahead – a presentation]. Svensk Bot Tidskr. 86:103–114.

- Klingström L. 2012. Halvseklet då skogen tog plats i samhällsdebatten. [The half century when the forest took place in public debate]. Skog & framtid. 2012:6–7.

- Kruys N, Fridman J, Götmark F, Simonsson P, Gustafsson L. 2013. Retaining trees for conservation at clearcutting has increased structural diversity in young Swedish production forests. For Ecol Manage. 304:312–321. 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.05.018

- Lidskog R, Sundqvist G, Kall A-S, Sandin P, Larsson S. 2013. Intensive forestry in Sweden: stakeholders' evaluation of benefits and risk. J Int Environ Sci. 10:145–160. 10.1080/1943815X.2013.841261

- Lindahl K. 1990. De sista naturskogarna. Om svensk naturvård i teori och verklighet [The last natural forests. Swedish conservation in theory and reality]. Stockholm: Naturskyddsföreningen.

- Lindenmayer DB, Franklin JF. 2002. Conserving forest biodiversity – a comprehensive multiscaled approach. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Lindenmayer DB, Franklin JF, Lõhmus A, Baker SC, Bauhus J, Beese W, Brodie A, Kiehl B, Kouki J, Pastur GM, et al. 2012. A major shift to the retention approach for forestry can help resolve some global forest sustainability issues: retention forestry for sustainable forests. Conserv Lett. 5:421–431. 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00257.x

- Lindhqvist T. 2000. Extended producer responsibility in cleaner production. Policy principle to promote environmental improvements of product systems [doctoral dissertation]. Lund: Lund University.

- Lindkvist A, Kardell Ö, Nordlund C. 2011. Intensive forestry as progress or decay? An analysis of the debate about forest fertilization in Sweden, 1960–2010. Forests. 2:112–146.