Abstract

Background: We aimed to analyze preferred and perceived levels of patients’ involvement in treatment decision-making in a representative sample of cancer patients.

Material and Methods: We conducted a multicenter, epidemiological cross-sectional study with a stratified random sample based on the incidence of cancer diagnoses in Germany. Data were collected between January 2008 and December 2010. Analyses were undertaken between 2017 and 2019. We included 5889 adult cancer patients across all cancer entities and disease stages from 30 acute care hospitals, outpatient facilities, and cancer rehabilitation clinics in five regions in Germany. We used the Control Preferences Scale to assess the preferred level of involvement and the nine-item Shared Decision-Making Questionnaire to assess the perceived level of involvement.

Results: About 4020 patients (mean age of 58 years, 51% female) completed the survey. Response rate was 68.3%. About a third each preferred patient-led, shared, or physician-led decision-making. About 50.7% perceived high levels, about a quarter each reported moderate (26.0%) or low (24.3%) levels of shared decision-making. Sex, age, relationship status, education, health care setting, and tumor entity were linked to preferred and/or perceived decision-making. Of those patients who preferred active involvement, about 50% perceived high levels of shared decision-making.

Conclusion: The majority of patients with cancer wanted to be involved in medical decisions. Many patients perceived a high level of shared decision-making. However, many patients’ level of involvement did not fit their preference. This study provides a solid basis for efforts to improve shared decision-making in German cancer care.

Introduction

Person-centered health care, patient-reported outcome measures, and shared decision-making (SDM) aim to put the individual patient with his or her preferences into the focus of modern high-quality cancer care. Shared decision-making is defined as a treatment decision-making process, in which the patient and the physician are actively involved. They mutually exchange relevant information, balance risks and benefits, and make an effort to reach a shared understanding on what is the best treatment option for this individual person [Citation1,Citation2]. Patients that are actively involved in treatment decision-making are better informed, appraise risks and benefits more adequately, and experience less decisional conflict [Citation3–5]. Furthermore, SDM is associated with higher satisfaction in patients and physicians [Citation3,Citation6].

Shared decision-making is especially relevant when there is more than one viable treatment option (i.e. preference sensitivity) and/or treatment options considerably affect patients’ subsequent quality of life [Citation7]. However, the preferred level of involvement in the decision-making process varies between patients [Citation8]. The majority of cancer patients prefer to be actively involved in the decision-making process [Citation9–14]. More recent studies are more likely to find patients wanting to be involved [Citation10]. Some studies found, e.g. younger patients to be more likely to want to be involved [Citation11]. Still, it remains unclear which factors are associated with decision-making preferences [Citation9].

There is a mismatch between cancer patients’ preferred and actual level of involvement, with a considerable proportion being less involved than they prefer [Citation15,Citation16]. This is likely to increase decision regret [Citation17]. Moreover, patients experiencing physician-led decision-making were less likely to report highest quality of care and physician communication compared to those reporting SDM [Citation14].

Many studies on SDM in cancer care focused on one or two cancer entities and/or used relatively small samples [Citation9,Citation15]. Epidemiological studies with representative samples are lacking. Data from epidemiological studies has a substantially lower risk of selection bias than data from studies using convenience sampling methods. Such representative data would enable us to better understand the needs and current experiences of the population of cancer patients regarding treatment decision-making. As a consequence, the results could help us to guide future research and inform and improve routine health care. Due to representativeness of the sample, the reported figures may be used as benchmarks for evaluating future findings.

Aim of this epidemiological study was to analyze patients’ preferred and perceived levels of involvement in treatment decision-making processes. Additionally, associations of demographic and clinical characteristics with involvement in decision-making were evaluated.

Material and methods

Study design

In this multicenter epidemiological cross-sectional study, adult cancer patients across all major cancer entities and disease stages were consecutively enrolled from acute care hospitals, outpatient cancer care, and cancer rehabilitation facilities [Citation18,Citation19]. We used a proportional stratified random sample based on the nationwide incidence of all cancer diagnoses in Germany [Citation20]. In the study sample, each stratum was represented in the same proportion as in the population. For more detailed information on sample size calculation and stratification, please compare the study protocol [Citation18]. For preparing this manuscript, we followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [Citation21].

Setting and subjects

The University Medical Centers of Hamburg, Freiburg, Heidelberg, Leipzig, and Würzburg participated, selected to represent diverse regions in Germany.

Individuals were eligible for study participation, if they had a confirmed diagnosis of a malignant tumor according to the medical chart and/or their physicians’ evaluation, were aged between 18 and 75 years, and able to speak and read German. Patients across all tumor entities and disease stages were included. Exclusion criteria were the presence of severe physical, cognitive, and/or verbal impairments that interfered with the ability to give informed consent.

Measures

Demographic information was gathered through a standardized self-report questionnaire assessing sex, age, relationship status, and education.

Medical information included time since first and recurrent diagnosis, tumor entity, disease status, UICC tumor stage, curative or palliative treatment intention, etc. and was gathered through medical records.

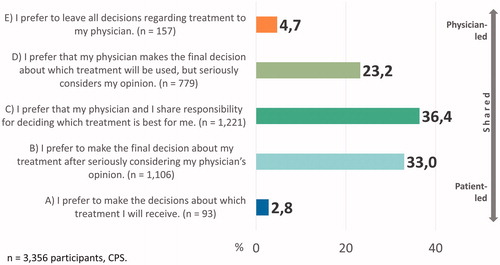

Control Preference Scale (CPS): The CPS [Citation22,Citation23] encompasses whether patients prefer decision-making being led by the doctor, the patient, or both. It contains five statements on the extent of the patients’ preferred participation in decision-making (cp. for item wording). The patient indicates a rank order of these five statements. Depending on the item with the highest ranking, the preference was categorized into three groups: ‘patient-led’ (items A and B), ‘shared decision-making’ (item C), and ‘physician-led’ (items D and E). The CPS has been widely used and found to be a reliable and valid instrument [Citation16,Citation23,Citation24]. It has been translated into German and psychometrically evaluated [Citation25,Citation26].

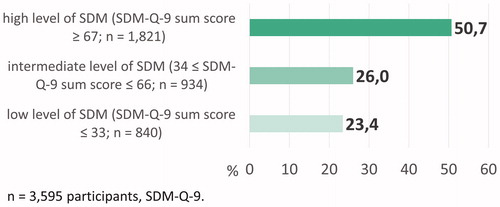

Nine-item Shared Decision-Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9): The SDM-Q-9 [Citation27] is a brief measure, developed to assess the extent of patients’ perceived shared decision-making in medical encounters. It consists of nine items characterizing the SDM process. In the study version, items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (‘strongly disagree’) to 4 (‘strongly agree’) (as opposed to the 6-point scale in the common version of the questionnaire that was published only later on). The SDM-Q-9 sum score was transformed to a 0–100 scale with higher values indicating a higher extent of SDM. The questionnaire was originally developed in German, showed good psychometric properties [Citation27–29], and was used in many studies [Citation30]. Due to pragmatic considerations (no predefined cutoffs), the sum scores (ranging from 0 to 100) were transformed into three categories using tertiles of the theoretical score range: (1) low SDM with SDM-Q-9 sum scores up to 33, (2) intermediate SDM with SDM-Q-9 sum scores between 34 and 66, and (3) high SDM with SDM-Q-9 sum scores of at least 67.

Data collection

Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were contacted by a trained research assistant and consecutively recruited at cancer care facilities within the regional study center’s area. All participants were asked to provide self-report data (e.g. CPS, SDM-Q-9, cp. [Citation18]), after providing written informed consent. Self-report data was collected via paper-and-pencil questionnaires administered by trained and supervised study research assistants. Filled-in questionnaires were sent to the study center at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Data entry was done manually by student assistants supervised by the study coordinator. Data entry was validated through regular checks in random subsamples in order to review completeness, correctness, reasonability, and consistency. Data were collected between January 2008 and December 2010. A more detailed description of the data collection process can be found in the study protocol by Mehnert et al. [Citation18].

Data analysis

Frequency distributions across the entire sample were determined for the CPS (in five categories) and SDM-Q-9 (in three categories). To test bivariate associations of demographic and clinical characteristics with preferred and perceived involvement in decision-making, CPS scores were summarized into three categories. Demographic characteristics were sex, age, relationship status, and education; clinical characteristics were health care setting, tumor entity, disease status, UICC tumor stage, treatment intention, and time since first and recurrent diagnosis. Associations of CPS and SDM-Q-9 categories with age and time since diagnosis were calculated using one-way ANOVA and p < .01 as level of significance. Associations with all other characteristics were tested with Pearson’s chi2-test (for sex, relationship status, etc.) or Mantel–Haenszel linear-by-linear association chi2-test (for education). For all those analyses, a Bonferroni-corrected level of significance of p < .0025 was used.

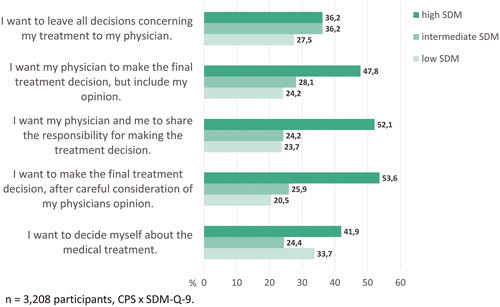

The concordance between preferred and perceived levels of involvement was investigated by cross-tabulating CPS (in five categories) and SDM-Q-9 (in three categories).

All statistical analyses were undertaken between 2017 and 2019 using SPSS version 18 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Ethical approval

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committees of all participating centers: Hamburg (ID: 2768), Schleswig-Holstein (ID: 61/09), Freiburg (ID: 244/07), Heidelberg (ID: S-228/2007; 50155039), Würzburg (ID: 107/07), and Leipzig (ID: 200–2007). All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Sample characteristics

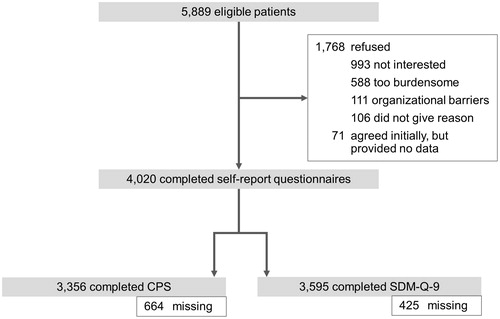

We identified 5889 eligible cancer patients at 30 facilities in Germany (cp. ). The response rate was 68.3%, leading to N = 4,020 participants providing self-report data. The comparison of study participants and non-participants is described elsewhere [Citation19].

dThe mean age of the 4020 participants was 58 years (SD = 11 years) and about half were women (n = 2068, 51%). Most participants indicated to be in a relationship (n = 2904, 72%). About a third each indicated low (n = 1244, 31%), intermediate (n = 1191, 30%), and high formal education statuses (n = 1564, 39%) (n = 21 missings). About 43% of participants were recruited at acute care hospitals, 33% at outpatient units, and 24% at inpatient rehabilitation centers. The most frequent tumor entities were breast (23%), digestive organs (20%), and male genital organs (17%). In most patients, cancer was in complete (41%) or partial (12%) remission.

Preferred level of involvement

N = 3356 participants did, n = 664 participants did not indicate preferred levels of involvement. Approximately one third each opted for an equally shared (C), patient-led (A or B), or physician-led (D or E) decision-making style (). N = 3,106 cancer patients (92.6%) wanted at least some level of shared decision-making (B, C, or D).

A one-way ANOVA showed differences in age for different preferred levels of involvement (F(2,3314) = 5.92, p = .003). Post-hoc analyses showed that those who preferred physician-led decision-making (D or E) were older than those who preferred patient-led decision-making (p = .003). Patients with a higher level of education were less likely to want a physician-led and more likely to want a patient-led decision (chi2-tests, ). As for tumor entity, the highest proportion of patients who preferred to decide by themselves was found for cancer of male genital organs. Patients with cancer of female genital organs, diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs, and breast cancer were the ones with the highest proportion that preferred SDM. The one-way ANOVA assessing differences in time since first and recurrent diagnosis did not yield statistically significant results. Other non-significant associations are shown in Supplementary Material A.

Table 1. Associations of preferred level of involvement with demographic and clinical characteristics.

Perceived level of involvement

The distribution of n = 3,595 participants’ perceived levels of involvement is shown in (n = 425 participants excluded due to missings).

A one-way ANOVA showed differences in age for different perceived levels of involvement (F(2,3543)=17.22, p < .001). Post-hoc analyses showed that those who perceived /high levels of SDM were significantly older than those who perceived intermediate (p < .001) or low (p = .002) levels of SDM. Men and people in a relationship were more likely to experience high levels of SDM (chi2-test, ). Inpatients were more likely to report high levels of SDM than outpatients and patients at rehabilitation facilities. Patients with cancer of male genital organs were most likely to experience high levels of SDM. Patients with cancer of female genital organs, diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs, or other tumor entities were most likely to experience low levels of SDM. The one-way ANOVA showed differences in time since recurrent cancer diagnosis for different perceived levels of involvement (F(2,3269)=10.65, p < .001). Post-hoc analyses showed that for those, who perceived low levels of SDM, time since recurrent diagnosis was longer than for those, who perceived high levels of SDM (p < .001). The one-way ANOVA assessing differences in time since first diagnosis did not yield significant results. Additional information on statistically non-significant associations can be found in Supplementary Material A.

Table 2. Associations of perceived level of involvement with demographic and clinical characteristics.

Concordance between preferred and perceived level of involvement

N = 3,208 participants indicated both their preferences and experiences (n = 812 participants excluded due to missings). Of those participants preferring some degree of shared decision-making (i.e. items B, C, or D of the CPS), about half indicated to have perceived a high level of SDM, which represents a match between preferred and perceived level of involvement. However, about a quarter to a fifth of patients preferring some degree of SDM indicated to have perceived low levels of SDM. For these cancer patients, preferred and perceived level of involvement did not match (see ).

Discussion

Within this large-scale epidemiological multicenter study, we assessed the preferred and perceived levels of involvement in decision-making of cancer patients in Germany. We found that about one third of participants preferred patient-led, shared, or physician-led decision-making, respectively. More than 90% of participants wanted to share the decision-making with their physician to some extent. Overall, half of the cancer patients reported to have perceived high levels of SDM. For about a quarter to a fifth of those patients who wanted some level of involvement in decision-making, preference and experience did not match. Sex, age, relationship status, education, occupational status, health care setting, and tumor entity were found to be associated with preferred and/or perceived levels of involvement.

A large proportion of cancer patients in Germany wants to be actively involved in SDM. This is in line with findings from various studies [Citation9–14]. Patients preferring physician-led decision-making were found to be older than those preferring to be actively involved in decision-making. Many prior studies used small samples and evidence on the association between different demographic and clinical characteristics and the preferred level of involvement was inconclusive [Citation9]. The results from the analyses of this large representative sample support the need for incorporating SDM in high-quality cancer care on a daily basis. Theoretically and empirically based SDM implementation studies, such as the current SDM implementation study at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf [Citation31], are needed to foster SDM in routine care.

Associations with demographic characteristics suggest that older male cancer patients are more likely to perceived high levels of SDM. One might speculate that those patients may either actually experience more SDM or be less critical and thus more prone to ceiling effects in measurement. Also, one could hypothesize that patients in a relationship might have more support from their partner in order to be able to actively participate in decision-making. A systematic review on patient-reported barriers to SDM concluded that patients need to feel empowered in order to be able to share decision-making processes [Citation32].

Study limitations

Many prior studies on SDM were restricted to single tumor entities [Citation9,Citation15], whereas this study incorporates patients with cancers from all different entities. Therefore, its results are generalizable to the entire population of German cancer patients. Moreover, both CPS and SDM-Q-9 are measures that have been used in multiple studies and showed good psychometric properties. However, limitations have to be considered. First, our patient sample is slightly biased toward younger age, more education, and rehabilitation setting [Citation19]. Since younger and more educated persons are more likely to prefer to be involved, this preference might be overrepresented in our sample. Second, clear-cut standards for adequate SDM are missing. Many measures such as the CPS or SDM-Q-9 are used in a rather descriptive way, and there are no cutoffs for adequate or insufficient SDM. Additionally, a previous version of the SDM-Q-9 with a 5-point instead of 6-point Likert scale was used in this study. Since the end points between the 5-point and the 6-point scale did not differ (i.e. both range between ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘strongly agree’) and only one of the middle options (‘somewhat agree’) was missing, we appraised the risk of bias to be minimal. Third, retrospective patient-reported questionnaires might be distorted by memory effects. Also, we do not know the decisions patient had made and referred to when answering the survey. For example, we cannot ensure that patients always referred to a decision that was made in the setting they were recruited from. Finally, all investigated associations were analyzed in an explorative bivariate manner without accounting for possible confounding. For example, statistically significant associations between tumor entity and preference for involvement might be fully or partly explained by demographic and/or clinical characteristics. Nevertheless, this study enabled the generation of generalizable and solid insights into how cancer patients want to make decisions and experience decision-making.

Clinical implications

The concept of SDM has consistently gained importance in health care research over the last decades [Citation33,Citation34]. However, several studies have emphasized that SDM is not implemented on a regular basis in current cancer care [Citation35–39]. Our findings suggest that many cancer patients might be satisfied with the way treatment decisions have been made. At the same time, there was a group of patients that preferred at least some level of SDM, but did not experience SDM (about 20-25%). This group needs specific attention. Other studies also found a lack of concordance between preferred and perceived decision-making styles for some patients [Citation9,Citation12]. Additionally, patients’ preferences for involvement have been found to change over time, and patients need to have had a fair chance to understand their treatment options and associated benefits and risks before assessing their preferred decision-making style [Citation40,Citation41]. Hasty and one-time-only assessment of decision-making preferences would bear the danger of passing patients over. It was suggested to routinely assess patients’ decision-making preferences in clinical practice [Citation11]. By a repeated assessment of preferences, health care professionals move their focus toward different ways of decision-making and make it possible to match their patients’ preferred and perceived levels of involvement. This enables preference-adapted decision-making.

Conclusion

Preferred levels of involvement in medical decisions in this representative sample of cancer patients were found to be split into three equipollent groups: patients wanting patient-led, shared, or physician-led decision-making. Half of the participants reported to have perceived high levels of SDM, while about 25% each reported to have perceived moderate or low levels of SDM. The concordance between preferred and perceived levels of involvement was found to be limited. Next steps are to come to a shared understanding about the amount of SDM different stakeholders deem appropriate (e.g. through cutoffs for measures) and to investigate ways to further improve cancer care.

Author Contribution

UK, AM, EB, HF, HS, JW, and MH designed and performed the original study, of which data were analyzed. PH, LK, and MH conceptualized the presented analyses. PH performed the data analyses with support from LK and MH. All authors contributed to interpretation of the findings. PH and MH drafted the first version of the manuscript, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (436.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank all health care teams involved in data collection in all local study centers. We thank all cancer patients for their study participation.

Disclosure statement

All authors report grants from German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe, DKH, grant no. 107465) during the conduct of the study. PH reports to have given one scientific presentation on shared decision-making during a lunch symposium outside the submitted work, for which she received compensation and travel compensation from GlaxoSmithKline GmbH in 2018. KW reports grants from Biotronik, personal fees from Biotronik, personal fees from Boston Scientific, grants from Resmed, and personal fees from Novartis outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–692.

- Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):114–131.

- Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(4):CD001431.

- Loh A, Simon D, Kriston L, et al. Shared decision making in medicine. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104(21):1483–1489.

- Calderon C, Ferrando PJ, Carmona-Bayonas A, et al. Validation of SDM-Q-Doc Questionnaire to measure shared decision-making physician’s perspective in oncology practice. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017.19(11):1312–1319.

- Whitney SN. A new model of medical decisions: exploring the limits of shared decision making. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):275–280.

- Brom L, Hopmans W, Pasman HR, et al. Congruence between patients’ preferred and perceived participation in medical decision-making: a review of the literature. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:25.

- Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision making of patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):299–318.

- Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18.

- Schuler M, Schildmann J, Trautmann F, et al. Cancer patients’ control preferences in decision making and associations with patient-reported outcomes: a prospective study in an outpatient cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2753–2760.

- Vogel BA, Helmes AW, Hasenburg A. Concordance between patients’ desired and actual decision-making roles in breast cancer care. Psycho-oncology. 2008;17(2):182–189.

- Albrecht KJ, Nashan D, Meiss F, et al. Shared decision making in dermato-oncology: Preference for involvement of melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2014;24(1):68–74.

- Kehl KL, Landrum M, Arora NK, et al. Association of actual and preferred decision roles with patient-reported quality of care: shared decision making in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):50.

- Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, et al. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(6):1145–1151.

- Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–696.

- Nicolai J, Buchholz A, Seefried N, et al. When do cancer patients regret their treatment decision? A path analysis of the influence of clinicians’ communication styles and the match of decision-making styles on decision regret. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(5):739–746.

- Mehnert A, Koch U, Schulz H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychosocial distress and need for psychosocial support in cancer patients – study protocol of an epidemiological multi-center study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):70.

- Mehnert A, Brahler E, Faller H, et al. Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. JCO. 2014;32(31):3540–3546.

- Kaatsch P, Spix C, Katalinic A, et al. Cancer in Germany 2007/2008: frequencies and trends. 8 ed. Berlin: Robert Koch Institut; 2012.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349.

- Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(9):941–950.

- Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21–43.

- Kryworuchko J, Stacey D, Bennett C, et al. Appraisal of primary outcome measures used in trials of patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):497–503.

- Rothenbacher D, Lutz MP, Porzsolt F. Treatment decisions in palliative cancer care: patients’ preferences for involvement and doctors’ knowledge about it. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(8):1184–1189.

- Giersdorf N, Loh A, Härter M. Quantitative Messverfahren des Shared Decison-Making. In: Scheibler F, Pfaff H, editors. Shared Decision-Making: Der Patient als Partner im medizinischen Entscheidungsprozess. Weinheim, München: Juventa-Verlag; 2003. p. 69–85.

- Kriston L, Scholl I, Hölzel L, et al. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):94–99.

- Rodenburg-Vandenbussche S, Pieterse AH, Kroonenberg PM, et al. Dutch translation and psychometric testing of the 9-item shared decision making questionnaire (SDM-Q-9) and shared decision making questionnaire-physician version (SDM-Q-Doc) in primary and secondary care. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0132158.

- De las Cuevas C, Perestelo-Perez L, Rivero-Santana A, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the 9-item Shared Decision-Making Questionnaire. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2143–2153.

- Doherr H, Christalle E, Kriston L, et al. Use of the 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9 and SDM-Q-Doc) in intervention studies-A systematic review. PloS One. 2017;12(3):e0173904.

- Scholl I, Hahlweg P, Lindig A, et al. Evaluation of a program for routine implementation of shared decision-making in cancer care: study protocol of a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):51.

- Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291–309.

- Blanc X, Collet T-H, Auer R, et al. Publication trends of shared decision making in 15 high impact medical journals: A full-text review with bibliometric analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14(1):71.

- Härter M, Moumjid N, Cornuz J, et al. Shared decision making in 2017: International accomplishments in policy, research and implementation. Zeitschrift Für Evidenz, Fortbildung Und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen. 2017;123-124:1–5.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Self-reported use of shared decision-making among breast cancer specialists and perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing this approach. Health Expect. 2004;7(4):338–348.

- Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):276–284.

- Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, et al. Many miles to go…”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(S2):S14.

- Hahlweg P, Hoffmann J, Harter M, et al. In absentia: an exploratory study of how patients are considered in multidisciplinary cancer team meetings. PloS One. 2015;10(10):e0139921.

- Hahlweg P, Härter M, Nestoriuc Y, et al. How are decisions made in cancer care? A qualitative study using participant observation of current practice. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016360.

- Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(2):102–114.

- Fisher KA, Tan ASL, Matlock DD, et al. Keeping the patient in the center: common challenges in the practice of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(12):2195–2201.