?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Impairments in sexual function are common among breast cancer survivors (BCSs), particularly in BCSs receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET). Whether these impairments cause distress, thus qualifying for a more clinically relevant diagnosis of sexual dysfunction (SD), is inadequately described among BCSs and represents an important research gap. Hence, the primary aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of clinically relevant SD, in this context: impairments with associated distress, and to identify factors associated with SD among BCSs on AET. Secondly, to explore the extent of distress caused by specific impairments in sexual function.

Materials and methods

In this cross-sectional study of BCSs on adjuvant treatment with endocrine therapy for at least three months, participants completed an online survey comprising standardized measures of sexual and psychosocial function. Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and Sexual Complaint Screener – Women (SCS-W) were used to asses clinically relevant SD. Multiple regression analyses were performed to identify factors significantly associated with SD.

Results

In total, 333 BCSs with a mean age of 58.7 years were included in the study, of whom 227 were sexually active. Among sexually active BCSs, 134 (59%) met the criteria for having clinically relevant SD, of whom 78 (58%) perceived cancer treatment as the primary reason for their sexual problems. Factors associated with SD included vaginal dryness (adjusted OR= 2.25, 95% CI: 1.52–3.34, p < .01) and psychological well-being (adjusted OR= 1.11, 95% CI: 1.03–1.18, p < .01). Age was not related to neither prevalence of SD nor the level of distress caused by any impairment, with exception of low sexual desire. Pain in relation to intercourse was the most distressing impairment.

Conclusion

SD was highly prevalent among sexually active BCSs on AET. Sexual health is important to address independent of the woman’s age.

Introduction

The increasing number of breast cancer survivors (BCSs) necessitates consideration of long-term side effects and late effects of breast cancer (BC) treatment including sexual dysfunction (SD) [Citation1–3]. Studies have found that both chemotherapy (CT) and adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) with either tamoxifen – an estrogen receptor blocker or aromatase inhibitors (AIs), that prevent estrogen formation in post-menopausal women, may interfere with sexual function by inducing or worsening symptoms often related to menopause; low libido, vaginal dryness and pain [Citation4–10]. Although CT is considered the primary cause of permanent premature menopause [Citation10,Citation11], side effects of AET may be more problematic as the recommended treatment duration is at least five years [Citation12,Citation13].

Several studies have evaluated the prevalence of SD among BCSs [Citation14–24], but inconsistency in the definition and assessment of SD complicates interpretation and comparison of results.

The most widely used classification systems, ICD-10 [Citation25] and DSM-IV-TR [Citation26,Citation27], describe four major categories of SDs (desire disorders, arousal disorder, orgasmic disorder, and sexual pain disorders). Both systems recognize the need for a distress criterion in defining SD [Citation28]. Accordingly, SD should comprise two elements: the impairment such as low desire, and the distress this imposes on the individual.

The most frequently used instrument to assess SD is the validated Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), the creation of which in 2000 was influenced by DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 [Citation25,Citation27,Citation29,Citation30]. However, FSFI does not account for distress and only few studies evaluating SD among BCSs have used an additional scale to integrate distress in their definition of SD [Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation31]. Hence, prevalence estimates of SD among BCSs assessed by the FSFI show a considerable variation between studies, ranging from 32% to 93% [Citation14–21,Citation32]. These variations may also reflect differences in age and degree of sexual activity between cohorts.

Assessment of distress caused by a sexual problem enables identification of women with clinically relevant sexual disorders. In accordance, studies evaluating SD solely based on the FSFI may overestimate the prevalence of clinically relevant SD, in this context; impairments in sexual function causing distress. To our knowledge, there is a research gap as no prior studies have assessed clinically relevant SD by combining total FSFI with a distress scale among sexually active BCSs in a Western population. Furthermore, present studies lack information of which impairments are most distressful to BCSs and therefore may require increased attention in a rehabilitation perspective.

In addition to treatment-related factors, other factors as age [Citation9,Citation33–35], depressive symptoms [Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37], concerns about body image [Citation15,Citation36–40], relationship issues [Citation34–36] and partner’s SD [Citation16,Citation36] significantly impact sexual health and may be associated with SD. However, most studies included only few factors in their analyses. In addition, sexual quality of life (SQOL) prior to BC is rarely reported, thus limiting the ability to determine if the sexual problems experienced are inflicted by treatment per se.

Estimates of prevalence of clinically relevant SD among BCSs are required to elucidate the need for sexual rehabilitation after BC. It is necessary to identify factors associated with SD and the impact of BC treatment to establish potential targets of rehabilitation. Hence, the primary aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of clinically relevant SD among BCSs on AET and to determine associated factors of SD. Secondly, to explore the extent of distress caused by specific impairments in sexual function and analyze if these were perceived as consequences of BC treatment by BCSs.

Materials and methods

Recruitment and data collection

This survey-based, cross-sectional cohort study was conducted from April 2018 to May 2019 at Aarhus University Hospital and Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark. Inclusion criteria: 1) female gender, 2) ≥18 years of age, 3) current treatment for ≥3 months with AET, either tamoxifen if pre- or perimenopausal or letrozole (an AI) if postmenopausal, 4) completion of all primary treatment (surgery, radiation therapy, CT) for BC stages 0-III, 5) no clinical evidence of recurrent disease. Exclusion criteria: 1) other cancer diagnosis, except non-melanoma skin cancer, 2) vaginal bleeding of unknown etiology <12 months prior to inclusion, 3) current treatment with antipsychotics, and 4) history of radiation of the vaginal area.

Eligible BCSs on AET attending follow-up visits at one of the two oncological departments were invited to participate in the online survey. Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients.

Data provided by BCSs were securely stored using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). All personal data were managed and protected in accordance with current European data legislation [Citation41,Citation42]. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (approval no. 2012-58-006). According to Danish law, a science-ethic committee approval for survey-based studies is not mandatory.

Assessment of primary outcome

Female sexual function index (FSFI)

The FSFI (19-items) is a psychometrically validated questionnaire addressing subdomains of sexual functioning in the past four weeks [Citation29,Citation43,Citation44]. The total FSFI score ranges from 2 to 36. A cutoff of 26.55 differentiates women at risk of SD from women without SD [Citation44]. Others have used FSFI in Danish [Citation45]. As FSFI is highly sensitive to sexual activity status [Citation15,Citation29], and as abstaining from sexual activity may not necessarily reflect SD but potentially absence of a partner, we performed the analysis of SD on a selected cohort comprising only sexually active BCSs, who engaged in intercourse. This was done to circumvent the most obvious confounder for identifying SD (not having a partner). Likewise, sexually active BCSs who answered ‘no intercourse’ in the FSFI were included if they had a partner.

Sexual complaint screener – women (SCS-W)

The SCS-W (10-items) is a screening tool addressing all domains of SD in the past six months, developed by the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) [Citation46]. There is preliminary evidence of good validity when compared to FSFI [Citation47]. Moreover, SCS-W addresses distress caused by any sexual complaint, reinforcing diagnosis of SD. In this study, distress was considered present when an impairment in sexual function was experienced as ‘a considerable problem’ or ‘a very great problem’.

Although the time course of SCS-W is beyond the scope of FSFI, this was not considered problematic as the cohort comprised BCSs on current treatment with AET for ≥3 months. Furthermore, BCSs had to have completed all primary treatment, thus both scales only cover a period, where the women had treatment for their BC, which minimizes the impact of the two different time frames.

Defining clinically relevant sexual dysfunction

SD was considered clinically relevant when BCSs were at risk of SD according to FSFI (total score 26.55) and had distress caused by at least one sexual impairment according to SCS-W.

Assessment of covariates

Sociodemographic and health-related variables were assessed by additional questions developed by the authors. Clinical variables as tumor characteristics and type of AET were collected from medical records.

Urogenital symptoms

The International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire – Female Sexual Matters associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTSsex) is a validated four-item questionnaire addressing vaginal and urinary symptoms [Citation48,Citation49]. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale, and greater values reflect more comprehensive problems.

Psychological well-being

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a validated questionnaire with 21 items measuring the severity of depressive symptoms [Citation50–52].

Body image and relationship status

Subscales of the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) were used to assess body image and relationship satisfaction. CARES is a validated, cancer-specific, rehabilitation and quality of life instrument [Citation53,Citation54].

Sexual quality of life prior to breast cancer diagnosis

Five items were developed to evaluate whether SQOL had changed due to BC treatment (Table S1, Supplemental).

The total survey consisted of 177 items and took approximately 30 min to complete.

ICIQ-FLUTSsex and CARES subscales were translated into Danish using a standard forward-backward translation process, based on MAPI Institute guidelines [Citation55]. Permission to use the scales was obtained from the developers of the instruments.

Statistical analysis

When testing for group differences, chi2 and the Wilcoxon–Man–Whitney tests were used. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used for analyzing associations between specific factors and SD. SD was constructed as a binary outcome (SD = total FSFI ≤ 26.55 +distress, No SD = total FSFI ≤ 26.55 ÷distress or total FSFI >26.55). First, univariate analyses were performed, separately testing all independent variables against SD. Factors significantly associated with SD and not significantly correlated to other independent variables, were included in the multivariate analysis. Restricting the number of independent variables entered into the regression model prevented overfitting [Citation56,Citation57]. The statistical model was further validated through tests for additivity and linearity. Continues variables are presented as means ± standard deviations when normally distributed, and medians including range for not normally distributed data. Results were considered significant if the two-sided p-values were <.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Management of missing values

Participants were excluded from either all analyses, a specific subscale or standardized instrument, when failing to complete >20% of the total survey or of a specific subscale or instrument, respectively. Missing responses with no discernible pattern were considered missing at random and were replaced with the participant’s mean item score of the relevant domain/subscale (in FSFI and CARES) and mean item score of the total questionnaire (in BDI).

Results

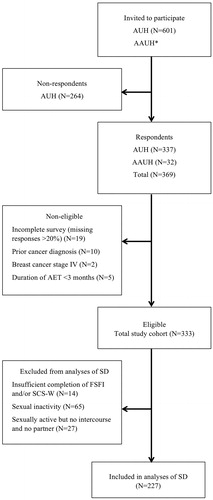

A total of 369 BCSs completed the survey. Response rate and exclusion of participants are displayed in . Thirty-six BCSs were non-eligible, primarily due to incomplete questionnaire data. The total study cohort amounted to 333 BCSs. The cohort for analysis of SD comprised 227 sexually active BCSs.

Figure 1. Flowchart. AUH: Aarhus University Hospital; AAUH: Aalborg University Hospital; BCSs: breast cancer survivors; AET: adjuvant endocrine therapy; FSFI: Female Sexual Function Index; SCS-W: Sexual Complaint Screener – Women; SD: sexual dysfunction. *At AAUH; the number of women invited to participate was not registered.

Characteristics of the study cohort are displayed in . Mean age was 58.74 ± 10.13 years (range: 22–80). Mean age of non-respondents was 61.34 ± 10.20 years (range: 23–91). No further characteristics of non-respondents were accessible; however, the small age difference indicates that our study cohort may also be representative regarding clinical parameters. Of characteristics not listed in , most participants were Caucasian (99%), sexually active (80%) and satisfied with their sexual life prior to BC (84%). Nine percent had taken antidepressants during the past month. Median time since surgery was 26.91 months (3–144 months) and median duration of AET was 22.93 months (3–120).

Table 1. Sociodemographic, health-related and clinical characteristics of the total study cohort.

Prevalence of clinically relevant sexual dysfunction

Among the 227 sexually active BCSs, 134 (59%) met the criteria for having clinically relevant SD (total FSFI score ≤26.55 + distress). Disregarding the presence of distress, 142 BCSs (63%) were at risk of SD (total FSFI score ≤26.55).

To explore the risk of bias when excluding sexually inactive BCSs, we compared BCSs based on sexual activity status (Tables S2–S4, Supplemental). No significant bias was revealed when comparing the two groups.

Reasons for sexual inactivity

Reasons for sexual inactivity among BCSs (N = 65) comprised: low libido (51%), no partner (49%), partner’s SD (23%), feeling unattractive (20%), relationship issues (17%), tiredness (11%) and urogenital symptoms (9%). Eight reported low libido and/or urogenital symptoms as the only reasons for sexual inactivity. These BCSs may have SD; however, when including these eight women in the analysis, SD prevalence remained at 59%.

Distress related to individual impairments

In the total cohort, lowest average domain scores in FSFI were seen for desire (median 2.4, range 1.2–5.4), and 99% of BCSs were at risk of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) (domain score 5) [Citation30]. However, only 26% of women at risk of HSDD reported distress in SCS-W.

Calculating average scores of the individual bother scales in the SCS-W showed that pain in relation to intercourse caused most distress, followed by lack of orgasm. Distress related to low desire was negatively associated with age (rho= −0.33, p < .01). Noteworthy, distress related to pain, lack of orgasm, arousal and pleasure was not associated with age.

Sexual dysfunction and covariates

Urogenital and psychosocial scores

Data from ICIQ-FLUTSsex showed that 74% of the total cohort reported current urogenital symptoms (dry vagina, urinary symptoms and/or pain in relation to intercourse). Only 20% have experienced these symptoms prior to BC diagnosis. The presence of specific urogenital symptoms prior to BC diagnosis and at study entry is shown in .

Table 2. Urogenital symptoms prior to the breast cancer diagnosis and at time of study entry.

Psychosocial scores indicated high psychological well-being (BDI, median (range): 6 (0–32)), high relationship satisfaction (CARES marital subscale: 0.22 (0–2.89)) and few body image concerns (CARES body image subscale: 0.33 (0–4)).

Sexual dysfunction associated with breast cancer treatment

Of the 134 sexually active BCSs with clinically relevant SD, 114 (85%) experienced their sexual life as worse or much worse after BC, and 78 women (58%) perceived their sexual problems as a consequence of BC treatment. These women reported that their sexual satisfaction had worsened due to low desire (N = 68, 87%), urogenital symptoms (N = 53, 68%), feeling of unattractiveness (N = 26, 33%) and/or tiredness (N = 13, 17%).

Relationship between sexual dysfunction and covariates

Results from univariate analyses are shown in . Vaginal dryness, psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction were significantly associated with clinically relevant SD. Odds for SD increased with higher scores at ICIQ-FLUTSsex (OR= 2.41, 95% CI: 1.68–3.47, p < .01) and at BDI (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.06–1.18, p < .01), indicating increasing probability of SD with more/worse vaginal dryness and depressive symptoms. Similarly, odds of SD increased with higher score on the CARES marital subscale (>median score vs. <median score: OR = 1.90, 95% CI: 1.10–3.29, p = .02), indicating increasing probability of SD with less relationship satisfaction. No treatment-related factors were significantly associated with SD.

Table 3. Odds ratios for sexual dysfunction according to selected covariates among sexually active women (N = 227).

Due to a non-linear relationship between log odds of SD and the continuous variable of relationship satisfaction, caused by a few BCSs with high subscale scores, categorization of relationship satisfaction was used in the multivariate analyses.

presents the results of the multivariate analysis. Only vaginal dryness (OR = 2.25, 95% CI: 1.52–3.34, p < .01) and psychological well-being (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.03–1.18, p < .01) remained significantly related to SD, with vaginal dryness being closest associated with SD.

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios for sexual dysfunction according to age, vaginal dryness, psychological well-being, relationship satisfaction and duration of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Discussion

The present study investigated the prevalence of clinically relevant SD, defined as impairments in sexual function causing distress, among BCSs on AET. Main findings were that among 227 sexually active BCSs, 59% met the criteria for having clinically relevant SD, and 58% of these women perceived SD as a consequence of BC treatment. Low desire was experienced by 99% of BCSs, including those being sexually inactive or not having a partner, consequently, only 26% reported associated distress. The most distressing impairment in sexual function was pain in relation to intercourse, followed by lack of orgasm. The level of distress related to both impairments was independent of age. Finally, vaginal dryness and psychological well-being were significantly associated with SD, whereas age, type of BC treatment and duration of AET did not influence the risk of SD.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to combine total FSFI with a distress scale to assess a more clinically relevant measure of any SD among sexually active BCSs in a western population. One study by Robinson et al. [Citation31] evaluated HSDD among Australian BCSs combining the FSFI desire domain and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS-R), however, no result regarding total FSFI was reported. The study by Lee et al. [Citation20], who used the combined measures of all FSFI domain scores and FSDS, was more comparable to our study regarding SD outcome. They found that among 269 sexually active Korean BCSs, 32% had SD. This estimate of SD differs considerably from our estimate of 59%, possibly due to methodological differences. Lee et al. [Citation20] used FSFI domain scores <3 as cutoff scores in their definition of SD. These cutoff scores may not appropriately assess SD, as they are not validated [Citation30]. In addition, the use of FSDS to assess distress may also play a role. FSDS is a validated instrument assessing sexual distress, which includes feelings of guilt, frustration, stress, worry, anger, embarrassment, and unhappiness [Citation58]. This deviates from distress assessed by SCS-W, as SCS-W measures the level of bother related to individual impairments in sexual function. Possibly, not all women bothered by impairments in sexual function, will meet the criteria for sexual distress according to FSDS. Nevertheless, we believe that distress assessed by a bother scale is a meaningful measure to describe clinically relevant SD.

Disregarding the inclusion of distress, we found that 63% of BCSs were at risk of SD according to FSFI. A recently published meta-analysis of SD prevalence among women with BC, including 15 studies using FSFI, found a pooled SD estimate of 73% [Citation59]. Several of the included studies did not exclude sexually inactive women from FSFI analysis, which may explain the higher estimate of SD. The significance of sexual activity status is demonstrated in the study by Raggio et al. [Citation15], where the prevalence of SD decreased from 74% to 60% when excluding sexually inactive BCSs. A newly published study by Gandhi et al. [Citation32] found that 47% of 278 sexually active BCSs were at risk of SD. This study cohort was similar to ours regarding menopausal status, however, only 59% received AET.

Among the 134 BCSs with clinically relevant SD in the present study, 58% associated SD with their BC treatment. This reflects results from a large Australian cross-sectional study [Citation37], where most BC patients reported several consequences of BC treatment affecting sexual health, such as vaginal dryness (63%) and feelings of unattractiveness (51%). In the prospective cohort study by Lee et al. [Citation20]., they investigated SD both prior to diagnosis and after BC treatment, with exception of AET, and found the prevalence of SD increased significantly from 17.6% to 31.6% following diagnosis and primary treatment. In a large national representative Danish cohort [Citation60], prevalence of SD assessed by FSFI-6 was 28% among 3394 sexually active women aged 55–64 years. The considerably lower prevalence of SD found in the background population as compared to BCSs supports the hypothesis that BC treatment has a major impact upon sexual well-being.

No significant association between type of BC treatment and risk of SD was revealed by regression analyses. Similar to other studies, we found significant associations between SD and psychological well-being [Citation20,Citation33–36], relationship satisfaction [Citation18,Citation21,Citation34–36] and vaginal dryness [Citation18,Citation24,Citation33,Citation36]. However only vaginal dryness and psychological well-being remained significant in the multivariate analysis. Due to the cross-sectional design of this study, it is not possible to discern the causality between poor relationship or depression and the risk of SD. Vaginal dryness remained significantly associated to SD in the multivariate analysis, indicating that AET itself may contribute with significant changes regarding urogenital symptoms. These findings further emphasize the importance of addressing urogenital symptoms independent of age.

Intriguingly, age did not influence the level of distress caused by impairments in sexual function, with exception of low desire. In the general population, sexual problems seems to increase with age [Citation60], whereas the proportion of women distressed about the sexual problems attenuates with age [Citation61,Citation62]. Side effects of BC treatment may significantly and abruptly worsen menopausal symptoms in peri- and post-menopausal women, which might explain why changes in sexual health are equally distressing for post- and pre-menopausal women.

Among the strengths of this study are the consideration of various factors potentially affecting sexual health and the thorough analysis of FSFI scores. Domain scores of zero were only accepted when SD was a plausible underlying cause; hence, the risk of overestimating prevalence of SD was reduced. Furthermore, reasons for sexual inactivity were obtained and did not seem to reveal any bias. Ideally, reasons for not engaging in intercourse should also have been assessed. Importantly, it was possible to evaluate the extent to which SD was perceived as a long-term side effect of BC treatment. Our study population is representative of BCSs from western countries regarding sociodemographic and clinical characteristics [Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation32]. However, this study is unique as 100% of the participants received AET.

The response rate of 56%, which is similar to other studies evaluating sexual health among BCSs, is a limitation [Citation1,Citation15,Citation35,Citation39], and may introduce selection bias if non-respondents represent either women with many or few sexual issues. Recall bias is inevitable when evaluating sexual health based on subjective experiences of participants and may in particular be present in evaluation of SQOL prior to BC.

Future perspectives

As low desire was experienced by 99% of BCSs and results in difficulties in all other phases of the sexual response or vice versa, more focus should be given to address this particular aspect of sexuality in AET patients.

The response rate emphasizes the taboo surrounding sexual issues, which necessitates a safe setting for sexological counseling and sufficient education of relevant staff. Sexological counseling should be offered to all BCSs, independent of age. Involving the partner may be beneficial, as relationship satisfaction was found to influence sexual health. It might be speculated that presence of SD can affect treatment compliance.

Conclusion

The present study emphasizes the clinical importance of addressing sexual difficulties among sexually active BCSs, as SD was highly prevalent and perceived as a consequence of BC treatment by two thirds of BCSs with SD. Vaginal dryness was the strongest associated factor of SD. Notably, age was not related to neither prevalence of SD nor level of distress caused by any impairment, with exception of low sexual desire. Pain in relation to intercourse caused the most distress.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (54.1 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(1):39–49.

- Malinovszky KM, Gould A, Foster E, Anglo Celtic Co-operative Oncology Group, et al. Quality of life and sexual function after high-dose or conventional chemotherapy for high-risk breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(12):1626–1631.

- Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, et al. Then and now: quality of life of young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(3):147–160.

- Morales L, Neven P, Timmerman D, et al. Acute effects of tamoxifen and third-generation aromatase inhibitors on menopausal symptoms of breast cancer patients. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2004;15(8):753–760.

- Fan HGM, Houédé-Tchen N, Yi Q-L, et al. Fatigue, menopausal symptoms, and cognitive function in women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: 1- and 2-year follow-up of a prospective controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):8025–8032.

- Fallowfield LJ, Leaity SK, Howell A, et al. Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-B. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55(2):187–199.

- Fallowfield L, Cella D, Cuzick J, et al. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the arimidex, tamoxifen, alone or in combination (ATAC) adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4261–4271.

- Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, et al. Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2788–2796.

- Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: understanding women's health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):501–514.

- Shapiro CL, Recht A. Side effects of adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):1997–2008.

- Ewertz M, Jensen AB. Late effects of breast cancer treatment and potentials for rehabilitation. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):187–193.

- Condorelli R, Vaz-Luis I. Managing side effects in adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(11):1101–1112.

- Burstein HJ, Lacchetti C, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(5):423–438.

- Speer JJ, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, et al. Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2005;11(6):440–447.

- Raggio GA, Butryn ML, Arigo D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sexual morbidity in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health. 2014;29(6):632–650.

- Pumo V, Milone G, Iacono M, et al. Psychological and sexual disorders in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer Management Res. 2012;4:61–65.

- Schover LR, Baum GP, Fuson LA, et al. Sexual problems during the first 2 years of adjuvant treatment with aromatase inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2014;11(12):3102–3111.

- Boquiren VM, Esplen MJ, Wong J, et al. Sexual functioning in breast cancer survivors experiencing body image disturbance. Psychooncology. 2016;25(1):66–76.

- Paiva CE, Rezende FF, Paiva BS, et al. Associations of body mass index and physical activity with sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(8):2057–2068.

- Lee M, Kim YH, Jeon MJ. Risk factors for negative impacts on sexual activity and function in younger breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1097–1103.

- Alder J, Zanetti R, Wight E, et al. Sexual dysfunction after premenopausal stage I and II breast cancer: do androgens play a role? J Sex Med. 2008;5(8):1898–1906.

- Cobo-Cuenca AI, Martin-Espinosa NM, Sampietro-Crespo A, et al. Sexual dysfunction in Spanish women with breast cancer. PloS One. 2018;13(8):e0203151.

- Kedde H, van de Wiel HB, Weijmar Schultz WC, et al. Sexual dysfunction in young women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(1):271–280.

- Ljungman L, Ahlgren J, Petersson LM, et al. Sexual dysfunction and reproductive concerns in young women with breast cancer: type, prevalence, and predictors of problems. Psychooncology. 2018;27(12):2770–2777.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization;1992.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA. American Psychiatric Association;2013.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press;2000.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Atalla E, et al. Definitions of sexual dysfunctions in women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2016;13(2):135–143.

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208.

- Meston CM, Freihart BK, Handy AB, et al. Scoring and Interpretation of the FSFI: what can be learned from 20 years of use? J Sex Med. 2020;17(1):17–25.

- Robinson PJ, Bell RJ, Christakis MK, et al. Aromatase inhibitors are associated with low sexual desire causing distress and fecal incontinence in women: an observational study. J Sex Med. 2017;14(12):1566–1574.

- Gandhi C, Butler E, Pesek S, et al. Sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: is it surgical modality or adjuvant therapy? Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42(6):500–506.

- Avis NE, Johnson A, Canzona MR, et al. Sexual functioning among early post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(8):2605–2613.

- Oberguggenberger A, Martini C, Huber N, et al. Self-reported sexual health: breast cancer survivors compared to women from the general population - an observational study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):599.

- Bredart A, Dolbeault S, Savignoni A, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of sexual problems after early-stage breast cancer treatment: results of a French exploratory survey. Psychooncology. 2011;20(8):841–850.

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, et al. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2371–2380.

- Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Changes to sexual well-being and intimacy after breast cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2012;35(6):456–465.

- Panjari M, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Sexual function after breast cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8(1):294–302.

- Rosenberg SM, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, et al. Treatment-related amenorrhea and sexual functioning in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2264–2271.

- Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):579–594.

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), 2016.

- Corrigendum to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). 2018.

- Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4606–4618.

- Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31(1):1–20.

- Petersen CD, Giraldi A, Lundvall L, et al. Botulinum toxin type A-a novel treatment for provoked vestibulodynia? Results from a randomized, placebo controlled, double blinded study. J Sex Med. 2009;6(9):2523–2537.

- Giraldi A, Rellini A, Pfaus JG, et al. Questionnaires for assessment of female sexual dysfunction: a review and proposal for a standardized screener. J Sex Med. 2011;8(10):2681–2706.

- Burri A, Porst H. Preliminary validation of a german version of the sexual complaints screener for women in a female population sample. Sexual Med. 2018;6(2):123–130.

- Brookes ST, Donovan JL, Wright M, et al. A scored form of the Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire: data from a randomized controlled trial of surgery for women with stress incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):73–82.

- ICIQ-Female Sexual Matters associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. [cited 2020 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.iciq.net/ICIQ.FLUTSsex.html.

- Warmenhoven F, van Rijswijk E, Engels Y, et al. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) and a single screening question as screening tools for depressive disorder in Dutch advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(2):319–324.

- Hopko DR, Bell JL, Armento ME, et al. The phenomenology and screening of clinical depression in cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26(1):31–51.

- Vodermaier A, Linden W, Siu C. Screening for emotional distress in cancer patients: a systematic review of assessment instruments. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(21):1464–1488.

- Ganz PA, Schag CA, Lee JJ, et al. The CARES: a generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1992;1(1):19–29.

- Schag CA, Heinrich RL, Aadland RL, et al. Assessing problems of cancer patients: psychometric properties of the cancer inventory of problem situations. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. Am Psychological Assoc. 1990;9(1):83–102.

- Mapi Research Institute. Mapi Institute Linguistic Validation. [cited 2020 Aug 21]. Available from: http://mapigroup.com/services/language-services/

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Springer Verlag; 2015. p. 72–74.

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–1379.

- Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D'Agostino D, et al. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357–364.

- Jing L, Zhang C, Li W, et al. Incidence and severity of sexual dysfunction among women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis based on female sexual function index. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(4):1171–1180.

- Frisch M, Moseholm E, Andersson M, et al. Sex in Denmark. Key findings from Project SEXUS 2017-2018. 2019.

- Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(3):193–208.

- Rosen RC, Shifren JL, Monz BU, et al. Correlates of sexually related personal distress in women with low sexual desire. J Sex Med. 2009;6(6):1549–1560.