Abstract

Introduction

International differences in cancer incidence and survival may partly reflect differences in cancer registration practices. As opposed to most other National Cancer Registries, Death Certificate Initiated (DCI) cases are not included in the Swedish Cancer Register. We characterized cases not reported to the Swedish Cancer Register and assessed the impact of inclusion of DCI cases on the completeness and estimates of one-year lung and pancreatic cancer survival.

Methods

We used information in the Swedish Cause of Death Register to identify individuals in two Health Care Regions (West and Uppsala Örebro) with lung or pancreatic cancer as cause of death in 2013. These records were cross-linked to the Cancer Register to identify individuals without a corresponding cancer registration, i.e. Death Certificate Notified (DCN) cases. DCN cases were cross-linked to the Patient Register to retrieve hospital discharge information to confirm the diagnosis. In a separate step, trace-back of DCN cases was performed to access medical records to validate the diagnosis.

Results

Following validity checks, an estimated 16% and 34% of individuals with a diagnosis of lung or pancreatic cancer, respectively, had not been reported to the SCR. Non-reported patients were older and had a considerable poorer survival than those included in the SCR. Inclusion of DCI cases decreased one-year lung cancer overall survival from 45% to 41%. The corresponding decrease for pancreatic cancer was five percentage points, from 29% to 24%.

Conclusions

Lung and pancreatic cancers are underreported to the SCR yielding too low incidence rates and upward biased survival estimates. We conclude that implementation of systematic death certificate processing with trace-back is feasible also within the Swedish system with regionalized cancer reporting. Verifying registrability by use of information in the Patient Register provided a good approximation of “corrected” survival estimates based on chart review.

Introduction

Differences between countries in cancer incidence and survival have in part been attributed to cancer registration practices [Citation1–3], including differences between the Nordic countries based on comparisons of NORDCAN data, a joint cancer platform to which all Nordic countries provide data [Citation4]. As opposed to most other National Cancer Registries, cancer cases first identified by information in Death Certificate Notifications (DCN) have historically never been included in the Swedish Cancer Register (SCR). Also, at present there is no legal support for routine trace-back of DCNs in Sweden. Non-inclusion of DCN cases eligible for registration has repeatedly been highlighted as a source of bias in comparative international studies since non-reported cases are likely not to represent a random sample of all cases, but rather those with poor prognosis leading to inflated survival estimates (particularly for cancer sites with a poor prognosis) and falsely low incidence rates (particularly among the elderly).

The aims of the present study were four-fold. First, to assess the completeness of reporting to the SCR of lung and pancreatic cancer. Second, to characterize registrable DCN cases. Third, to estimate the impact on one-year survival following inclusion of death certificate initiated (DCI) cases in the SCR. Fourth, to test the feasibility of performing DCN trace-back in the Swedish setting.

Material and methods

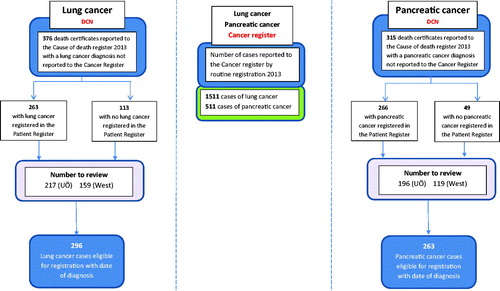

In a multistep approach, we first used information available in the Swedish Cause of Death Register (CDR) and the Swedish Cancer Register (SCR) to identify death certificate notified (DCN) cases. Second, by use of two different approaches we assessed eligibility for registration of DCN cases in the SCR; by manual trace-back with medical chart review and by record linkage to hospital discharge data in the Patient Register (PR), respectively (). The individually unique personal identity number, assigned to all Swedish residents at birth or permanent residency allowed for individual level record linkage between registers [Citation5].

Figure 1. Project overview: lung and pancreatic cancer cases reported to the Swedish Cancer Register (middle column). Flow-chart: identification of Death Certificate Notified cases (DCNs) and assessment of eligibility for registration in the Swedish Cancer Register (left and right columns).

Although there is presently no routine use of death certificate information to identify cancer cases in Sweden, we choose to consistently use the terms DCN and DCI, respectively, when describing our project.

The Swedish cause of death register

The CDR is held by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW) and covers all deaths in Sweden since 1961 based on information from death certificates. Less than 1% of all reported deaths lack cause of death information and the validity for malignant tumors, based on a comparison between death certificates and medical records, has been estimated to exceed 90% [Citation6].

The Swedish cancer register

The nationwide, population-based SCR was established in 1958. Reporting to the SCR is mandated by law with a generally high completeness for solid tumors [Citation7]. The majority of all tumors recorded in the SCR are verified by two independent sources (clinician and pathologist) and are coded according to the most recent version of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O). While the NBHW administers the SCR, all cancer notifications are in an initial step monitored and coded at six Regional Cancer Centers across Sweden before data are submitted for national compilation at the NBHW.

The Swedish patient register

Since 1987, the PR held by the NBHW, records information on hospital admissions and discharges diagnosis coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) from all hospitals in Sweden. Data are generated by hospital in-patient administrative systems and are of general high completeness and quality. Previous comparisons of information in the PR and other health databases have shown a high degree of agreement [Citation8].

Identifying DCN cases

Information in the Swedish Cause of Death Register (CDR) was used to identify individuals deceased in 2013 in two Swedish Health Care Regions (West and Uppsala Örebro) with lung or pancreatic cancer as underlying or contributing cause of death. These records were cross-linked to the Swedish Cancer Register (SCR) to identify individuals without a corresponding cancer registration, that is, DCN cases.

Identifying DCI cases by trace-back and review of medical records

Trace-back of DCN cases with chart review for the purpose of identifying DCI cases eligible for inclusion in the SCR was coordinated from Regional Cancer Centers West and Uppsala Örebro. In this step, clinicians at hospital clinics in the patient´s area of residence were contacted and requested to complete a standardized form to validate the diagnosis and retrieve a date of diagnosis based on information in electronic medical records.

Identifying DCI cases by use of information in the patient register

In a separate step, DCN cases were cross-linked to the Patient Register to determine eligibility for registration in the SCR based on hospital discharge information in support of the diagnosis under study. This way, a file of registrable DCI cases was generated based on record-linkage only.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software package [Citation9].

Overall survival by years since diagnosis and registration status were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method with survival time defined from the date of diagnosis to the date of death (attributed to any cause), emigration, or 31st of December 2016, whichever occurred first. Information on date of death or emigration was obtained from files in the continuously updated Population Register [Citation10]. Completeness was estimated by assuming that the number of DCNs identified with date of death in 2013 roughly reflected the number among all DCNs that would have been traced back to a date of diagnosis in 2013. Completeness of reporting to the SCR was then calculated by dividing the number of cases reported by the sum of the number of reported cases and the number of DCNs.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board in Stockholm (2016-291-31/1).

Results

Lung cancer

In 2013, 1511 men and women residing in the two regions under study were reported to the Swedish Cancer Register with a lung cancer diagnosis. In addition, 376 lung cancer cases were identified as DCN, thus individuals without a record in the SCR. Following medical chart review, 296 (79.3%) of the DCN cases met the criteria to be registrable in the SCR with a date of diagnosis. Of these, 191 (64.5%) had a date of diagnosis in 2013, 70 (23.6%) in 2012 and 35 (11.7%) in 2011 or earlier.

Reasons for not being registrable and included in the analysis (n = 78) included absence of information in medical records confirming lung cancer (n = 40), metastasis from other primary site tumor (n = 23), other (n = 14) and no medical record found (n = 1) ().

Table 1. Number and proportion of death certificate notified (DCN) lung cancer cases eligible for registration in the Cancer Register, by healthcare region and by supporting discharge information of a lung cancer diagnosis in the Patient Register.

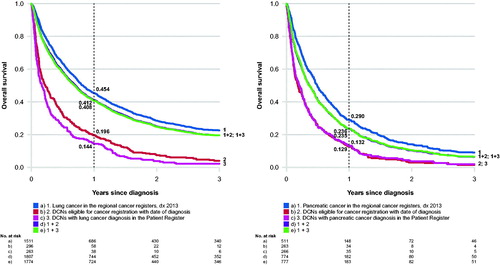

Median age at diagnosis of DCI lung cancer cases were considerably higher compared to those registered in the SCR (78 versus 70 years) with men being slightly overrepresented in this group (51.4%). As expected, one year-overall survival was markedly lower in DCI cases (19,6%) compared to those with a record in the SCR (45.4%) (). Following the inclusion of DCI cases, estimated one-year overall survival in lung cancer patients declined by four percentage points, from 45% to 41% ().

Figure 2. (a) Lung cancer: overall survival by mode of registration and assessment of registrability. (b) Pancreatic cancer: overall survival by mode of registration and assessment of registrability.

Table 2. Characteristics and one-year survival of lung cancer cases: (1) reported to the Cancer Register, (2) death certificate notified (DCN) cases eligible for registration in the Cancer Register (death certificate initiated, DCI), (3) death certificate notified (DCN) cases with suppporting discharge information in the Patient Register.

Compared to cases registered in the SCR, a separate assessment of registrable DCN cases based only on supporting information available in the Patient Register (n = 263) also showed older age at diagnosis (78 years), an overrepresentation of men (53.2%), and an even lower one-year survival in DCI lung cancer cases (14.4%) ().

Taken together, an estimated 16% of all lung cancer cases had not been reported to the SCR. Further, our data show that without trace-back with detailed assessment of registrability of DCN cases, the corrected number of lung cancer cases would have been overestimated by approximately 4%.

Pancreatic cancer

In the two regions under study, a total of 511 men and women had a record of pancreas cancer in the Swedish Cancer Register in 2013. An additional 315 pancreas cancer cases were mentioned on death certificates only, i.e. DCN cases. Following trace-back and review of medical charts, 263 of these cases met the criteria to be included in the SCR with a date of diagnosis. Of these, 170 (64.6%) had a date of diagnosis in 2013, 73 (27.8%) in 2012, 20 (7.6%) in 2011 or earlier. Reasons for not being eligible for registration (n = 48) were absence of information confirming pancreatic cancer (n = 46) and no medical record found (n = 2) (). Median age at diagnosis pancreatic cancer cases eligible for registration was higher compared to those registered in the SCR (79 versus 70 years). Women were overrepresented among DCI cases (55.5%) ().

Table 3. Number and proportion of death certificate notified (DCN) pancreatic cancer cases eligible for registration in the Cancer Register, by assessement by (A) trace-back and review of medical records, and (B) by supporting discharge information of a pancreatic cancer diagnosis in the Patient Register.

Table 4. Characteristics and one-year survival of pancreatic cancer cases: (1) reported to the Cancer Register, (2) death certificate notified (DCN) cases eligible for registration in the Cancer Register (death certificate initiated, DCI), (3) death certificate notified (DCN) cases with suppporting discharge information in the Patient Register.

One year-overall survival was markedly lower in DCI cases (12.9%) compared to patients with a record in the SCR (29.0%) (). One-year overall survival in pancreatic cancer declined by five percentage points from 29.0% to 23.6% after the inclusion of DCI cases ().

An assessment of DCN cases eligible for registration based only on hospital discharge information in the Patient Register (n = 266) also showed older age at diagnosis, an overrepresentation of women (53%), and a lower one-year survival (13.2%) compared to cases with a record in the SCR ().

Based on the number of DCN cases judged to meet the criteria for registration, an estimated 34% of all pancreatic cancer cases lacked a record in the SCR. Without trace-back, the number of pancreatic cancer cases would have been overestimated by about 6%.

Discussion

A high completeness is an important dimension of data quality in population-based cancer registries [Citation11]. Although no cancer registries are 100% complete, trace-back and inclusion of registrable DCN cases lead to more accurate estimates of cancer incidence. Reporting of newly diagnosed cancer cases is mandated by law in Sweden with a documented high completeness in the SCR for solid tumors with the exception for malignancies commonly diagnosed in advanced stages and hematological malignancies. In earlier assessments, the overall proportion of cases not reported to the SCR appear to be stable over time and has been estimated at around 4% [Citation12,Citation13].

While earlier investigators have addressed the underreporting of cancers with a poor prognosis in Sweden [Citation14–17], this is the first study based on comprehensive processing of death certificates including trace-back with diagnostic validation at the source, i.e. medical records. For the purpose of the present study, we choose to focus on lung - and pancreatic cancer, malignancies that are known to be underreported both in Sweden and other countries [Citation2], particularly in elderly, non-hospitalized individuals. Based on detailed trace-back of DCNs, we confirmed a marked underreporting of both sites to the SCR, yielding too low incidence rates and upward biased survival estimates. As much as 16% and 34% of lung and pancreatic cancer cases, respectively, were not reported to the SCR. With regard to pancreatic cancer, a similar magnitude of underreporting has been documented in the Netherlands where one study estimated that less than 70% of pancreatic cancers were reported to the Netherlands Cancer Register [Citation18].

As expected, non-reported cases identified from information on death certificates were markedly older at diagnosis and had a poorer prognosis compared to cases reported to the SCR. Following inclusion of DCI cases, the estimated overall one-year survival declined by about four percentage points among patients with lung cancer and five percentage points among individuals with pancreatic cancer. Although information in the Patient Register also may be incomplete and include errors, of special note was that assessment of registrability of DCNs using information from this data source only, yielded data that provided a good approximation of “corrected” survival estimates based on trace-back and detailed review of medical records.

Our results corroborate findings in a study of the impact of different aspects of variation in cancer registration practices across 12 jurisdictions, including Sweden. In that study, the estimated overall one-year survival among lung cancer patients based on information retrieved from register linkages fell by 3.5 percentage points following inclusion of DCI cases for the period 2008-2012 (3).

Strengths of our study included the use of information from cross-linked population-based registers with national coverage. For the purpose of diagnostic validation at the source, we were able to access virtually all medical records of cases identified by death certificate notifications. However, the review of medical records involved different abstractors and was conducted in slightly different ways at the clinics in the two health care regions under study. Thus, differences in assessment of diagnostic criteria across clinics cannot be excluded. Further, information on severity of disease at diagnosis was incomplete and was not included in the analyses. Another limitation was that some of the identified DCN cases included as DCIs had a date of diagnosis before 2013, potentially affecting the comparability to cases reported to the SCR with a confirmed diagnosis in 2013. However, under the assumption that the effect of this inconsistency is similar across calendar years, it would have only a minor, if any, impact on our overall conclusions regarding patterns of underreporting and estimates of corrected survival. The two health care regions under study include approximately 40% of all residents of Sweden and can be considered to be a representative sample of the total Swedish population. Since current Swedish legislation prohibits the NBHW to routinely share information on death certificates and Patient Register data with Regional Cancer Centers, the present project was conducted as a research study following ethical approval. However, the experiences gained during the course of this project clearly show that routine death certificate processing including trace-back would be feasible also within the Swedish system of regionalized administration of cancer notifications.

Although the impact of exclusion of death certificate-initiated cases on official cancer statistics often is described as a major concern [Citation2,Citation3], challenges and potential biases associated with routine trace-back practices and inclusion of DCI cases are seldom addressed.

First, it should be noted that routines for trace-back differ and vary in quality across National Cancer Registries, and do not guarantee that all non-reported cases are captured. This is a particular challenge in the oldest age groups where diagnostic intensity may be low or death certificates are written in non-hospital settings based on incomplete information, that is, cancer as a cause of death may or may not be mentioned. For example, the age-specific incidence of lung and pancreatic cancer declines sharply in older age groups (>80 years) in all Nordic countries except Finland [Citation2], reflecting challenges to identify all cases despite established routines for trace-back with verification of eligibility for registration.

Second, inclusion of DCIs may produce underestimated survival estimates since it captures a subset of non-reported cases with a generally poorer prognosis, and not non-reported individuals with cancer that are still alive or died due to other causes. The inclusion of DCI cases will by design only add individuals who have died with cancer mentioned on their death certificate, and as long as this is not the case for all non-reported cases at the time of analysis, a bias will be introduced. The magnitude of this bias depends on several factors, but may under certain circumstances be as large as those associated with non-inclusion of DCI cases. Also, these biases yield estimates in different directions, further impeding comparisons of survival between Cancer Registers including and not including DCI cases in routine statistics. However, for lung and pancreatic cancer the vast majority of non-reported cases are likely to have died with their cancer as the main or contributing cause of death, and any bias due to inclusion of DCI cases should be small.

In conclusion, we found that a large proportion of lung and pancreatic cancer cases are not reported to the SCR. As expected, trace-back and inclusion of DCI cases decreased survival estimates for both cancer sites. Verifying registrability of DCN cases by use of hospital discharge information in the Patient Register provided a good approximation of” corrected” survival estimates based on detailed chart review. Further, we conclude that practical implementation of a system for death certificate processing with trace-back is feasible also within the Swedish system with regionalized cancer reporting. A harmonization of registration routines in Sweden with those used in other cancer registers would increase the completeness of the SCR and facilitate international comparisons.

Acknowledgments

The project was made possible by the continuous reporting by clinicians and regional health authorities to the Swedish National Cancer Register, the Patient Register and the Cause of Death Register. We thank regional representatives for their support in reviewing medical charts.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Robinson D, Sankila R, Hakulinen T, et al. Interpreting international comparisons of cancer survival: the effects of incomplete registration and the presence of death certificate only cases on survival estimates. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(5):909–913.

- Pukkala E, Engholm G, Hojsgaard Schmidt LK, et al. Nordic Cancer Registries - an overview of their procedures and data comparability. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(4):440–455.

- Eden M, Harrison S, Griffin M, et al. Impact of variation in cancer registration practice on observed international cancer survival differences between International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP) jurisdictions. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;58:184–192.

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, et al. NORDCAN-a Nordic tool for cancer information, planning, quality control and research. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(5):725–736.

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–667.

- Brooke HL, Talback M, Hornblad J, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(9):765–773.

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/swedish-cancer-register.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna; 2019. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2):125–136.

- Bray F, Parkin DM. Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods. Part I: comparability, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(5):747–755.

- Mattsson B, Wallgren A. Completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register. Non-notified cancer cases recorded on death certificates in 1978. Acta Radiol Oncol. 1984;23(5):305–313.

- Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, et al. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):27–33.

- Kilander C, Mattsson F, Ljung R, et al. Systematic underreporting of the population-based incidence of pancreatic and biliary tract cancers. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(6):822–829.

- Lambe M, Eloranta S, Wigertz A, et al. Pancreatic cancer; reporting and long-term survival in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(8):1220–1227.

- Tettamanti G, Ljung R, Ahlbom A, et al. Central nervous system tumor registration in the Swedish Cancer Register and Inpatient Register between 1990 and 2014. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:81–92.

- Nilsson M, Tavelin B, Axelsson B. A study of patients not registered in the Swedish Cancer Register but reported to the Swedish Register of Palliative Care 2009 as deceased due to cancer. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(3):414–419.

- Fest J, Ruiter R, van Rooij FJ, et al. Underestimation of pancreatic cancer in the national cancer registry - Reconsidering the incidence and survival rates. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:186–191.