Abstract

Background

Rehabilitation and palliative care may play an important role in addressing the problems and needs perceived by socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer. However, no study has synthesized existing research on rehabilitation and palliative care for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer. The study aimed to map existing research of rehabilitation and palliative care for patients with advanced cancer who are socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Material and Methods

A scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). A systematic literature search was performed in CINAHL, PubMed and EMBASE. Two reviewers independently assessed abstracts and full-text articles for eligibility and performed data extraction. Both qualitative and quantitative studies published between 2010 and 2019 were included if they addressed rehabilitation or palliative care for socioeconomically disadvantaged (adults ≥18 years) patients with advanced cancer. Socioeconomic disadvantage is defined by socioeconomic position (income, educational level and occupational status).

Results

In total, 11 studies were included in this scoping review (138,152 patients and 45 healthcare providers) of which 10 were quantitative studies and 1 was a qualitative study. All included studies investigated the use of and preferences for palliative care, and none focused on rehabilitation. Two studies explored health professionals’ perspectives on the delivery of palliative care.

Conclusion

Existing research within this research field is sparse. Future research should focus more on how best to reach and support socioeconomically disadvantaged people with advanced cancer in community-based rehabilitation and palliative care.

Introduction

Socioeconomically disadvantaged cancer patients are diagnosed later in their disease trajectory [Citation1–7], have worse health outcomes [Citation8] and have lower cancer survival rates than patients in similar disease circumstances that are in socioeconomically better positions [Citation9]. Socioeconomic disadvantage is often defined in the literature by socioeconomic position (SEP) [Citation10], where income, educational level and occupational status are the most commonly used indicators [Citation11–13]. The disparity in diagnostic delay results in disproportionately more patients being diagnosed with cancer in advanced stages with no possibility of curative treatment [Citation14].

A meta-analysis from 2016 found that patients with advanced cancer had the greatest unmet needs within the following domains: informational, patient care and support, physical, psychological, and activities of daily living [Citation15]. Generally, cancer patients with low SEP are more likely to report unmet needs than their better-off counterparts [Citation11]. A variety of studies have shown that rehabilitation and palliative care can improve or maintain function and increase quality of life (QoL) in patients with advanced cancer [Citation16–18]. Initiatives to increase QoL in these patients are usually regarded as palliative care [Citation19]; however, little research has been devoted to the beneficial aspects of rehabilitation aimed at enhancing or maintaining function in these patients [Citation16]. The coordination and integration of rehabilitation and palliative care for patients with advanced cancer are slowly changing, particularly in some countries like England and Denmark [Citation20,Citation21], and is explicitly described in the most recent Danish Cancer Plan [Citation22].

Social inequality in cancer in Denmark has recently been reviewed in a Whitebook from the Danish Cancer Society [Citation23]. The Whitebook identified few Danish papers on social inequality in rehabilitation or palliative care for cancer patients [Citation23]. To our knowledge, no study has synthesized existing research on rehabilitation and palliative care for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer. This research field seems not to be extensively researched, which is why a scoping review is warranted to preliminarily assess the extent and scope of available research literature [Citation24]. This scoping review aimed to map existing research of rehabilitation and palliative care for patients with advanced cancer who are socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Methods

Study design

A scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation25]. The methodological framework developed by Hanneke et al. [Citation24] was also applied. Quality assessment of included studies is beyond the scope of a scoping review [Citation26]. This scoping review will help determine whether a systematic review of the literature is warranted.

Searches and information sources

The literature search was conducted together with an information specialist who helped to select the search terms. The search strings were tailored for each database. The following search terms were used: ‘advanced cancer’, ‘socioeconomically disadvantaged’, ‘rehabilitation’ and ‘palliative care’. We then found synonyms for each of these search terms by searching the subject headings of each database. The following filters were used: published in the past 10 years; language: English, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish; adult: 18 +years. The searched databases were CINAHL, PubMed and EMBASE. The reference lists of included studies were assessed, and a citation search was conducted in Web of Science based on the included studies (the full search is available on request).

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they addressed rehabilitation or palliative care for socioeconomically disadvantaged (one of its synonyms: income, educational level, and occupational status) adults (≥18 years) with advanced cancer. WHO definitions of rehabilitation and palliative care were applied [Citation19,Citation27]. Quantitative and qualitative studies and reviews were included. Eligibility criteria together with the search string tailored for the PubMed database can be seen in .

Table 1. Search strategy for the scoping review.

Study selection

Two reviewers (MSP and HKR) independently assessed titles and abstracts for eligibility using the pre-determined inclusion criteria. Any disagreement was discussed and if necessary, a third reviewer (KlC) was involved to achieve consensus. The Rayyan© online data management software was used to select articles in the title/abstracts phase [Citation28]. The software removes duplicates and assists with title/abstract screening, including the possibility of registering reasons for the exclusion of articles [Citation28]. The articles selected based on their title/abstracts were transferred and stored in an Endnote© reference library [Citation29]. The full-text articles were then assessed independently by two reviewers (MSP and HKR). Consensus between the two reviewers was reached, and reasons for excluding articles were registered.

Data charting process

One investigator performed data extraction using a study-specific data extraction form. The following data were extracted: country, sample characteristics (number, diagnosis, age and gender), study aim, study design, determinants of SEP, and findings regarding socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer and rehabilitation/palliative care. A second reviewer verified the extracted data. The findings were synthesized using a narrative summary.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

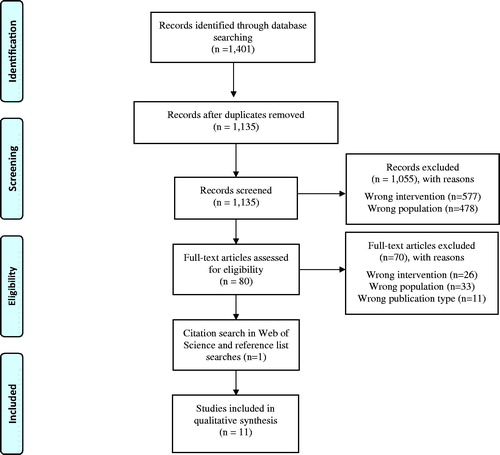

Eleven articles were included in the review [Citation30–40], nine of which represented a total of 138,152 patients and 45 healthcare providers [Citation30–33,Citation35,Citation36,Citation38–40]. In two studies, the number of patients was not accounted for [Citation30,Citation31]. The database search produced 1401 potential articles; 80 articles were full-text screened and 10 articles were included for reviewing. After assessing reference lists of the included studies and a citation search, one additional article was included. A PRISMA flow chart (see ) outlines the selection process, including reasons for the exclusion of the articles.

Characteristics of included studies

presents the extracted data from the 11 included articles [Citation30–40]. Eight articles were published between 2017 and 2019 [Citation30–32,Citation36–40]. Eight originated from USA [Citation30–34,Citation36–38], two from Canada [Citation35,Citation39] and one from the Netherlands [Citation40]. Six studies were register-based studies, all of which were conducted in North America [Citation30–32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37]; two were cohort studies [Citation33,Citation36]; one was a cross-sectional study [Citation38]; one was a secondary analysis of data from a cluster-randomised controlled trial [Citation40]; and one was a qualitative study [Citation39]. Ten studies involved patients or hospitalizations [Citation30–38,Citation40]; and two studies included healthcare providers [Citation33,Citation39], one of which included both patients and healthcare providers [Citation33]. The population age spanned from 21 to ≥65 years. Men and women were almost equally represented in the studies, except in the study by Rosenfeld et al., which only included gynaecological cancer [Citation37]. The most prevalent cancer types across the articles were as follows: six articles with mixed cancer types [Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36,Citation38,Citation39], two with colorectal cancer [Citation35,Citation40], one with lung cancer [Citation34], one with malignant glioma [Citation32] and one with gynaecological cancer [Citation37].

Table 2. Findings from the included articles (N = 11).

Synthesis of results

All studies reported on palliative care for patients with advanced cancer [Citation30–40]. The studies did not describe the palliative care interventions in detail, viz. the specific content, duration and delivery method [Citation30–40]. In the included studies, SEP was mainly conceptualized by income in eight studies [Citation30–35,Citation37,Citation38], while four studies used education [Citation32,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40] and only one study conceptualized SEP by occupation [Citation40].

Two themes emerged from the study results: (1) Socioeconomic factors influence the use of and preferences for palliative care and (2) Health professionals’ perspectives on delivery of palliative care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer.

Socioeconomic factors influence the use of and preferences for palliative care and rehabilitation

Income

Eight studies reported varying results regarding the association between income and palliative care [Citation30–35,Citation37,Citation39]. Three studies found low income to be associated with lower likelihood of receiving palliative care [Citation31,Citation34,Citation35]. Mack et al. investigated the use of hospice among patients insured by Medicaid and Medicare [Citation34], reporting that mainly older, low-income patients utilized hospice less often than older, high-income patients [Citation34]. Similarly, Maddison et al. reported that low-income patients with advanced colorectal cancer are at higher risk of not receiving palliative care than high-income patients [Citation35]. Rubens et al. [Citation31] found patients in the lowest income quartile were less likely to receive palliative care consultations than patients in the highest income quartile. In contrast to these findings, three studies found no association between low income and utilization of palliative care [Citation30,Citation32,Citation37]. Two of these studies reported no statistically significant difference in the use of palliative care over income quartiles [Citation30,Citation37]. The third study found that those with a higher income were less likely to utilize hospice than low-income patients [Citation32]. Furthermore, two studies investigated health professionals’ perspectives on income as a predictor for use of palliative care [Citation33,Citation39]. One of the two studies found that health professionals overestimated low income as a barrier for the utilization of palliative care compared to patients [Citation33]. The other reported that lack of financial resources affected patients’ abilities to deal with symptoms, and that low income and financial constraints were perceived as barriers to utilizing palliative care [Citation39].

Education

Five studies reported on associations between educational level and palliative care [Citation32,Citation36,Citation38–40]. Three studies analyzed the influence of education on the likelihood of (1) hospice enrollment [Citation32], (2) referral to palliative care [Citation36] and (3) palliative care preferences [Citation38]. Forst et al. found higher educational level to be associated with hospice enrollment [Citation32]. The other two studies found no significant association between educational level and referral to or preferences for palliative care [Citation36,Citation38]. However, Schuurhuizen et al. [Citation40] showed that higher educational level was associated with a higher likelihood of use of palliative care. In the qualitative study by Santos Salas et al., health professionals found low educational level to negatively impact patients’ ability to deal with and understand symptom control; low educational level was also found to contribute to symptom complexity [Citation39].

Occupational status

A single study investigated the influence of employment [Citation40]. The study found no association between employment and use of palliative care.

Health professionals’ perspectives on delivery of palliative care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer

Two studies explored aspects of health professionals’ perspectives on how to deliver palliative care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer. Lyckholm et al. reported a discrepancy in the perception of having discussed hospice, where providers thought hospice was discussed more often than did low-income patients (>90% of providers vs. 57% of patients). The authors concluded that it is imperative to ask each patient specifically about barriers to adequate palliative care [Citation33]. In the other study, Santos Salas et al. found that health professionals faced challenges when trying to relieve the suffering of socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer. They also had a secondary aim of outlining practice strategies when working with populations with social disparities. However, they omitted these results in their paper because of word limitations in the published journal [Citation39].

Discussion

This scoping review shows that current research has focused mainly on access to palliative care in socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer, while none of the studies addressed rehabilitation. The results of the studies were to some extent contradictory. Some showed that patients with advanced cancer of low SEP were less likely to participate in palliative care, while others found no such associations. Most studies investigated the impact of income on receiving palliative care. How to reach and support socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer was not made clear by the review, as none of the studies investigated this aspect.

Another issue emerging from our findings is that none of the included studies explored patients’ preferences for a rehabilitation and palliative care intervention. This knowledge is important when developing an intervention [Citation41]. The qualitative study by Santos Salas et al. highlights that future research should address providers’ knowledge and patients’ preferences for community-based interventions [Citation39]. A qualitative study by Johnston et al. described the development of an intervention aiming at increasing uptake of palliative care services for African American patients with advanced solid organ malignancies [Citation42]. They assessed the views of the patients, their caregivers and community health providers regarding how this could be achieved. Johnston et al. [Citation42] suggested a lay navigation model to increase uptake of palliative care and thereby reduce social disparities. This could indicate that future interventions should focus on cross-sectoral transition from hospital treatment to community-based support and care.

One unanticipated finding was that none of the included studies focused on rehabilitation. However, existing research shows that patients with advanced cancer have unmet rehabilitation needs [Citation15,Citation43–46]. This may be even more prevalent in the group of cancer patients with low SEP [Citation8,Citation11]. Socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer may therefore need rehabilitation in order to enable them to live as independently as possible and secure the best QoL until they die [Citation21]. A possible explanation for this lack of rehabilitation studies may be that rehabilitation is usually not an approach that is provided within the context of palliative care [Citation47]. Palliative care has traditionally been the chosen approach for this group of patients, focusing on improvement of QoL by prevention and relief of suffering [Citation19] rather than focusing on optimizing functioning and reducing the experience of disability [Citation27]. It is well established in a variety of studies that rehabilitation and palliative care can prevent decline and improve function, symptoms, mood and coping, and lead to better independence and QoL in patients with advanced cancer [Citation16,Citation48–50]. In addition, both research and national healthcare plans in Denmark are paying growing attention to the need for coordinating rehabilitation and palliative care [Citation22], which is expected to enhance patients’ function and QoL [Citation47]. If these approaches are implemented inclusively, socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer will therefore most likely benefit from both approaches.

We used low SEP to define a disadvantaged person. However, while many scholars in the United States often define disadvantaged people in terms of ethnicity [Citation42,Citation51–54], older age is more commonly applied worldwide [Citation54–57]. Moreover, other modifiable factors like lifestyle [Citation58], health literacy [Citation59] and social support [Citation60] can contribute to social inequality in health. This illustrates the complexity within this field of research. Developing an intervention encompassing all these perspectives is therefore inconceivable. SEP is one of the most used definitions in the literature [Citation11–13] and may also be a proxy for several intermediary factors, e.g., health literacy, life style and general health [Citation10,Citation61]. Thus, using SEP may be an appropriate way of defining a disadvantaged population.

Methodological considerations

This scoping review was meticulously conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guideline [Citation25]. Nonetheless, it also has its limitations. It was difficult to provide precise search synonyms for the search term ‘socioeconomically vulnerable’. For instance, we included synonyms such as cohabitation, family characteristics and living alone in the PubMed database search. However, we were only interested in including disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer, defined by educational level, disposable income and occupational status. Using many search terms of no relevance may have caused an imprecise search with many hits (N = 1,135 hits); yet may also have lowered the risk of missing relevant literature. We included rehabilitation or palliative care interventions abiding by the WHO definitions, such as physical exercise [Citation19,Citation27]. In our literature search, few search terms addressed physical exercise, and we may have used even more than the ones we chose to use. Gray literature, editorials/commentaries, guidelines, letters and conference abstracts were excluded. In addition, we excluded studies reporting in other languages than English, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. Altogether, this may have resulted in missed articles and could have affected the findings of the present scoping review. Furthermore, our search strings did not include patients who died from cancer, which can explain the absence of a Danish register-based study by Neergaard et al. [Citation62] that investigates the association of income on access to specialist palliative care in patients where cancer was the cause of death. The purpose of a scoping review is to identify the extent of research evidence within a specific field and identify the need for a systematic review of the available evidence [Citation24,Citation26]. Nevertheless, we searched in three of the largest databases (PubMed, Embase, Cinahl), assessed the reference lists of included studies and did a citation search. This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of existing research about rehabilitation and palliative care for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer.

Implications for future research

A national research center has been established in Denmark, the Danish Cancer Society National Center for Optimal Cancer Outcomes for All (COMPAS). The overall goal of COMPAS is to provide optimal cancer treatment to all Danish cancer patients irrespective of their social position, and it will seek to eliminate inequality in cancer treatment by developing and testing interventions [Citation63]. One of the planned interventions will be focusing on social reach in rehabilitation and palliative care, the REHPA Vulnerability Study. The project aims to develop an intervention model that guides community-based rehabilitation and palliative care services for socially vulnerable patients with advanced cancer. Both register-based studies together with qualitative studies involving patients and health providers will inform the intervention model, whose feasibility will subsequently be tested in the community. The present scoping review serves as the scientific evidence foundation for developing the intervention, particularly it highlights the need for more qualitative studies exploring patients’ preferences for a rehabilitation and palliative care intervention.

Overall, very few studies were identified, which could indicate that a systematic review currently is not warranted because the research field is still not mature and needs more primary studies. These studies could very well focus on user involvement and interventions.

Conclusion

For socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer, research concerning access to and need for palliative care is sparse; for rehabilitation, it appears to be non-existent. The research in our scoping review mainly focused on the association of income, educational level and occupational status with receiving palliative care. Based on this scoping review, the field appears to be too immature for a systematic review. Future research should focus more on patients’ perspectives and how best to reach and provide rehabilitation and palliative care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with advanced cancer.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ibfelt E, Kjaer SK, Johansen C, et al. Socioeconomic position and stage of cervical cancer in Danish women diagnosed 2005 to 2009. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(5):835–842.

- Dalton SO, Frederiksen BL, Jacobsen E, et al. Socioeconomic position, stage of lung cancer and time between referral and diagnosis in Denmark, 2001–2008. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(7):1042–1048.

- Frederiksen BL, Brown P. d N, Dalton SO, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in prognostic markers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: analysis of a national clinical database. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(6):910–917.

- Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Harling H, et al. Social inequalities in stage at diagnosis of rectal but not in colonic cancer: a nationwide study. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(3):668–673.

- Ibfelt EH, Steding-Jessen M, Dalton SO, et al. Influence of socioeconomic factors and region of residence on cancer stage of malignant melanoma: a Danish nationwide population-based study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:799–807.

- Olsen MH, Bøje CR, Kjaer TK, et al. Socioeconomic position and stage at diagnosis of head and neck cancer - a nationwide study from DAHANCA. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):759–766.

- Seidelin UH, Ibfelt E, Andersen I, et al. Does stage of cancer, comorbidity or lifestyle factors explain educational differences in survival after endometrial cancer? A cohort study among Danish women diagnosed 2005–2009. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(6):680–685.

- Kjaer TK, Johansen C, Andersen E, et al. Influence of social factors on patient-reported late symptoms: report from a controlled trial among long-term head and neck cancer survivors in Denmark. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1713–E1721.

- Dalton SO, Olsen MH, Johansen C, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in cancer survival - changes over time. A population-based study, Denmark, 1987–2013. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):737–744.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12.

- Holm LV, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, et al. Social inequality in cancer rehabilitation: a population-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):410–422.

- Oksbjerg Dalton S, Halgren Olsen M, Moustsen IR, et al. Socioeconomic position, referral and attendance to rehabilitation after a cancer diagnosis: a population-based study in Copenhagen, Denmark 2010–2015. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):730–736.

- Moustsen IR, Larsen SB, Vibe-Petersen J, et al. Social position and referral to rehabilitation among cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):720–726.

- American Cancer Society. What is advanced cancer? 2017 [cited 2017 Dec 21]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/advanced-cancer/what-is.html.

- Moghaddam N, Coxon H, Nabarro S, et al. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3609–3622.

- Salakari MR, Surakka T, Nurminen R, et al. Effects of rehabilitation among patients with advances cancer: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):618–628.

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6(6):CD007760.

- Sarmento VP, Gysels M, Higginson IJ, et al. Home palliative care works: but how? A meta-ethnography of the experiences of patients and family caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):0

- World Health Organisation. WHO Definition of Palliative Care; 2019 [cited 2019 January 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

- Nottelmann L, Jensen LH, Vejlgaard TB, et al. A new model of early, integrated palliative care: palliative rehabilitation for newly diagnosed patients with non-resectable cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3291–3300.

- Tiberini R, Richardson H. Rehabilitative palliative care enabling people to live fully until they die: a challenge for the 21st century. London: Hospice UK, St Joseph’s Hospice, St Christopher’s, Burdett Trust for Nursing; 2015.

- Danish Health Authority [Sundhedsstyrelsen]. Strengthened efforts in the field of cancer. In: Danish Health Authority, editor. Scientific Plan for Cancer Plan IV [Styrket indsats på kraeftområdet. Fagligt oplaeg til kraeftplan IV]. Copenhagen: Danish Health Authority; 2016.

- Olsen MH, Kjaer TK, Dalton SO. Social inequality in cancer in Denmark. Whitebook [Social Ulighed i Kraeft i Danmark. Hvidbog]. 1 ed. Copenhagen: Danish Cancer Association; 2019.

- Hanneke R, Asada Y, Lieberman L, et al. The scoping review method: mapping the literature in “structural change” public health interventions. SAGE; 2017.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

- World Health Organisation. WHO Definition of Rehabilitation [cited 2020 April 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

- Clarivate Analytics. EndNote. [2020 April 29]. Available from: https://www.endnote.com/.

- Okafor PN, Stobaugh DJ, Nnadi AK, et al. Determinants of palliative care utilization among patients hospitalized with metastatic gastrointestinal malignancies. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(3):269–274.

- Rubens M, Ramamoorthy V, Saxena A, et al. Palliative care consultation trends among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer in the United States, 2005 to 2014. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(4):294–301.

- Forst D, Adams E, Nipp R, et al. Hospice utilization in patients with malignant gliomas. Neuro-Oncology. 2018;20(4):538–545.

- Lyckholm LJ, Coyne PJ, Kreutzer KO, et al. Barriers to effective palliative care for low-income patients in late stages of cancer: report of a study and strategies for defining and conquering the barriers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2010;45(3):399–409.

- Mack JW, Chen K, Boscoe FP, et al. Underuse of hospice care by Medicaid-insured patients with stage IV lung cancer in New York and California. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2569–2579.

- Maddison AR, Asada Y, Burge F, et al. Inequalities in end-of-life care for colorectal cancer patients in Nova Scotia. J Palliat Care. 2012;28(2):90–96.

- Penrod JD, Garrido MM, McKendrick K, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized cancer patients referred for inpatient palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(12):1321–1326.

- Rosenfeld EB, Chan JK, Gardner AB, et al. Disparities associated with inpatient palliative care utilization by patients with metastatic gynecologic cancers: a study of 3337 women. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(4):697–703.

- Saeed F, Hoerger M, Norton SA, et al. Preference for palliative care in cancer patients: are men and women alike? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(1):1–6.e1.

- Santos Salas A, Watanabe SM, Tarumi Y, et al. Social disparities and symptom burden in populations with advanced cancer: specialist palliative care providers' perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(12):4733–4744.

- Schuurhuizen C, Braamse AMJ, Konings I, et al. Predictors for use of psychosocial services in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first line systemic treatment. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):115.

- Bleijenberg N, Janneke M, Trappenburg JC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste by optimizing the development of complex interventions: enriching the development phase of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:86–93.

- Johnston FM, Neiman JH, Parmley LE, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on the use of community health workers to improve palliative care use by African Americans with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(3):302–306.

- Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, et al. Symptoms and problems in a nationally representative sample of advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2009;23(6):491–501.

- Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, et al. Do advanced cancer patients in Denmark receive the help they need? A nationally representative survey of the need related to 12 frequent symptoms/problems. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1724–1730.

- Rainbird K, Perkins J, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. The needs of patients with advanced, incurable cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(5):759–764.

- Cheville AL, Troxel AB, Basford JR, et al. Prevalence and treatment patterns of physical impairments in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2621–2629.

- Padgett LS, Asher A, Cheville A. The intersection of rehabilitation and palliative care: patients with advanced cancer in the inpatient rehabilitation setting. Rehabil Nurs. 2018;43(4):219–228.

- Silver JK, Raj VS, Fu JB, et al. Cancer rehabilitation and palliative care: critical components in the delivery of high-quality oncology services. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(12):3633–3643.

- Berry DL. editor Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life integrated into clinical cancer care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27(3):203–210.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742.

- Cole AP, Nguyen D-D, Meirkhanov A, et al. Association of care at minority-serving vs non–minority-serving hospitals with use of palliative care among racial/ethnic minorities with metastatic cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187633–e187633.

- Hanson LC, Armstrong TD, Green MA, et al. Circles of care: development and initial evaluation of a peer support model for African Americans with advanced cancer. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(5):536–543.

- Abdollah F, Sammon JD, Majumder K, et al. Racial disparities in end-of-life care among patients with prostate cancer: a population-based study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(9):1131–1138.

- Ejem DB, Barrett N, Rhodes RL, et al. Reducing disparities in the quality of palliative care for older African Americans through improved advance care planning: study design and protocol. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(S1):90–100.

- Hanratty B, Addington-Hall J, Arthur A, et al. What is different about living alone with cancer in older age? A qualitative study of experiences and preferences for care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:22.

- Bunt S, Steverink N, Andrew MK, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of the social vulnerability index for use in the Dutch context. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11):14.

- Wallace LM, Theou O, Pena F, et al. Social vulnerability as a predictor of mortality and disability: cross-country differences in the survey of health, aging, and retirement in Europe (SHARE). Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27(3):365–372.

- Friis K, Larsen F, Nielsen C, et al. Social inequality in cancer survivors' health behaviours: a Danish population-based study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(3):e12840.

- Friis K, Lasgaard M, Rowlands G, et al. Health literacy mediates the relationship between educational attainment and health behavior: a Danish population-based study. J Health Commun. 2016;21(sup2):54–60.

- Kjaer TK, Mellemgaard A, Stensøe Oksen M, et al. Recruiting newly referred lung cancer patients to a patient navigator intervention (PACO): lessons learnt from a pilot study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):335–341.

- Levin-Zamir D, Baron-Epel OB, Cohen V, et al. The association of health literacy with health behavior, socioeconomic indicators, and self-assessed health from a National Adult Survey in Israel. J Health Commun. 2016;21(sup2):61–68.

- Neergaard MS, Jensen AB, Olesen F, et al. Access to outreach specialist palliative care teams among cancer patients in Denmark. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):951–957.

- COMPAS. Danish Cancer Society National Center for Optimal Cancer Outcomes for All [COMPAS, Dansk Forskningscenter for Lighed i Kraeft]. [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.compas.dk/.