ABSTRACT

At the local government level in the US, the process of privatisation has been a dynamic one of experimentation with market delivery and return to public delivery when privatisation fails to deliver. National survey data show what drives this experimentation are pragmatic concerns with service cost and quality. Service and market characteristics, local government capacity and regulatory framework matter. In contrast to current international debates about the potential of remunicipalization to be a political reassertion of the public sector, for US local governments it is primarily a process of pragmatic municipalism. While some shifts in private finance and state regulatory environment favour private actors at the expense of local government, federal investments since COVID-19 provide funding and policy preference for maintaining a public role.

Introduction

Public administration scholars have spent decades studying privatisation of local government services. Less attention has been given to reverse privatisation, or remunicipalization of public services. Recent claims regarding a new wave of remunicipalizations around the world (Transnational Institute Citation2021) are countered by more cautious scholarship which notes a lack of empirical evidence of a wave of remunicipalization (Clifton et al. Citation2021). While some scholars argue these reversals are a political move to re-publicise public services (Cumbers and Paul Citation2022; Lobina and Weghmann Citation2021), others recognise this as a pragmatic market management process, especially in the US (Hanna and McDonald Citation2021; Warner and Aldag Citation2021).

Claims of reassertion of the role of the public sector are not new. Ramesh, Araral, and Wu (Citation2010) explored the reassertion of public delivery through a series of cases of privatisation around the world, including education services in China (Painter and Mok Citation2008) and health care in China, South Korea, Singapore and Thailand (Ramesh Citation2008) and Vietnam (London Citation2008) where higher levels of public involvement resulted in better service outcomes. The studies also addressed the importance of a public coordinating role in transportation services (Barter Citation2008), and the limits of privatisation among water utilities in the Global South (Araral Citation2009a; Pérard Citation2009). In the US, at the local government level, the pendulum swing away from privatisation and back towards public delivery occurred back in 2002 (Warner Citation2008).

Various theoretical frames have been used to understand privatisation and its reverse. These include transactions costs (Hefetz and Warner Citation2004; Brown and Potoski Citation2004; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010), social choice (Hefetz and Warner Citation2007; Hebdon and Jalette Citation2008), and strategic political competition (Feigenbaum and Henig Citation1994; Bel and Fageda Citation2017; McDonald Citation2018). Araral (Citation2009a) offers a framework which gives attention to the characteristics of the service (monopoly or competitive, public or market), the players (residents, providers, regulators, politicians), and the institutions (transactions costs, norms).

In the US, pragmatic municipalism is a theoretical framing that helps us understand local government behaviour. This theory argues that local governments balance community needs and political interests within fiscal constraints (Kim and Warner Citation2016; Warner, Aldag, and Kim Citation2021a). Pragmatic municipalism sits between two extremes. At one end is austerity urbanism, which sees the emergence of a local predatory state focused on privatising and cutting services (Peck Citation2014; Donald et al. Citation2014) with Detroit as a prime example (Atuahuene Citation2020). At the other end is progressive municipalism, which sees the democratic reassertion of public ownership (Cumbers and Paul Citation2022; Lobina and Weghmann Citation2021). While cities at both ends of the spectrum can be found, the vast majority of US local governments sit in the middle range, ‘riding the wave’ of fiscal stress and using both privatisation and remunicipalization as strategies to maintain service delivery (Warner, Aldag, and Kim Citation2021a; Warner and Clifton Citation2014). The process is more pragmatic than political. Pendulum swings are not that great because local government managers, as pragmatic actors, are seeking a balance across strategies with the goal of maintaining services. They are neither revolutionary nor reactionary, but rather pragmatic managers.

Privatisation and remunicipalization can be understood as part of a larger management process that involves market management (Hefetz and Warner Citation2004; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010), contract management (Girth et al. Citation2012; Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2008), labour management (Warner and Hefetz Citation2020), and balancing of needs and political interests (Gradus and Budding Citation2020; Bel and Fageda Citation2017). In the US, most of these choices are local and should be understood in that context. But we also must situate local governments in a broader multiscalar system of government. State level action affects local government choices. While US local governments have traditionally enjoyed more autonomy than local governments in the UK and Europe (OECD Citation2016), there are increasing pressures from US state governments to pre-empt local authority (Kim and Warner Citation2018; Riverstone-Newell Citation2017). Led by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), this regulatory capture of state level policy increasingly favours private interests – against labour, environment and local government (Hertel-Fernandez Citation2019). This could affect the policy space in which local governments can practice pragmatic municipalism in the future. However, recent shifts in federal policy under the American Rescue Plan (passed in 2021) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (passed in 2022) push back against state pre-emption and open up more policy space for local government, as the laws specifically support municipal ownership in water, sewer and broadband (U.S. Department of Treasury Department Citation2021; Warner, Kelly and Zhang Citation2022.

This paper reviews US local government privatisation and remunicipalization from an historical empirical and theoretical lens. It lays out the market failure arguments to explain the twin processes of privatisation and remunicipalization that draw primarily from property rights and transaction cost theory to explain market management behaviour. Then it broadens the discussion of management to include attention to local political interests with regard to citizens, labour and place. Most of the international literature on both privatisation and remunicipalization has been focused on water utilities (Pérard Citation2009; Bel, Fageda, and Warner Citation2010; Bel Citation2020). Thus, the paper uses the water sector to illustrate the factors affecting privatisation and remunicipalization and the challenges of addressing power differences between local government, the state and private market actors. How these power differentials are resolved will determine how local governments can manage privatisation and remunicipalization in the future.

Privatisation, Remunicipalization and Market Management

Local government is the primary service provider for urban residents. In the US, local governments are responsible for a very broad range of services. Most services are publicly provided, but historically, as services emerge, they may first emerge as private and then later be municipalised. This occurred in the late 19th and early 20th century as urbanisation prompted cities to municipalise private service delivery in water, street cleaning and transport to improve quality, promote better service coordination, control costs and reduce corruption (Adler Citation1999; Hanna and McDonald Citation2021; Rossi Citation2021). Some of these municipalisation efforts were pragmatic, while others were more politically progressive. Thus, the idea of municipalisation is not new. What is new is the coining of the term, remunicipalization after 2010. This was done as an explicit political project to reclaim public ownership from privatisation, with special interest in public water (Hoedeman, Kishimoto, and Pigeon Citation2013). But the process of reversing privatisation had been studied long before the term, remunicipalization, was coined, and many of those studies take a broader economic and management perspective. While some privatisation reversals may be politically progressive, large scale empirical analysis finds market management is the more common explanation in the US, the only country where longitudinal empirical data is available (Warner and Hebdon Citation2001; Hefetz and Warner Citation2004, Citation2007; Brown and Potoski Citation2004; Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2008; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010; Warner and Hefetz Citation2012; Warner and Aldag Citation2021).

The push to insert market efficiencies into local government led to a new interest in privatisation in the 1980s and 1990s (Hood Citation1991; Osborne and Gaebler Citation1992). While in the UK, this process was pushed by the national government; in the US, privatisation was never required. Local government leaders were generally supportive of market-based service delivery and willing to consider the possibilities of contracting out. The popular book, Reinventing Government, by Osborne and Gaebler (Citation1992), was widely read by local officials, and increased experimentation with contracting followed. According to national surveys of local governments in the US, privatisation peaked in 1997 (Warner and Hefetz Citation2012).

Less studied is the process of reverse privatisation. Some economists and public administration scholars considered privatisation to be a one way street, arguing the superiority of markets would lead to lower costs and better service quality (Savas Citation1987) and free government to focus on steering rather than rowing (Osborne and Gaebler Citation1992). But some major theoretical failures were embedded in this logic.

Three theoretical failures stand out – and all derive from a failure to understand the limits of private markets for public goods. First was the false assumption that private delivery would be cheaper. Property rights theory (Hart, Shleifer, and Vishny Citation1997) tells us that private providers will seek to maximise profit, so unless strong regulation or monitoring is present, prices will not be lower with privatisation. The second fallacy was the assumption that there would be competition in public service markets. Many public services, by their nature, are natural monopolies. Thus, in a local area, there may be competition for the market, but there will not be competition in the market once a contract is let. In that case, privatisation just substitutes a public monopoly for a private one. Indeed, studies of US managers have found that on average, there are fewer than two providers for each of the range of services local governments provide (Warner and Hefetz Citation2012). The third problem was the failure to recognise the high transaction costs involved in contracting (Williamson Citation1979). These costs include not only contract design and the process of identifying qualified bidders, but also the ongoing costs of monitoring (Girth et al. Citation2012). Indeed transaction costs has been the primary theoretical frame for most US studies of privatisation and its reverse (Brown and Potoski Citation2004; Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2008; Hefetz and Warner Citation2004, Citation2007; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010; Warner and Hefetz Citation2012, Citation2020).

Much of the debate around privatisation has focused on costs, though more recent research gives broader attention to service quality, social and environmental concerns (Gonzalez Rivas and Schroering Citation2021; Carolini and Raman Citation2021; D’Amore, Landriani, and Lepore Citation2021; McDonald Citation2016). Research has found that cost savings from privatisation are ephemeral at best, as providers may offer a loss-leading contract to capture the market, and raise prices later. Water delivery and waste collection are the services with the most experience internationally with privatisation. Individual empirical studies find both lower and higher costs with privatisation, but a meta-regression analysis of all studies published from 1965–2010 across the world finds no statistical support for lower costs with privatisation (Bel, Fageda, and Warner Citation2010).

Cost savings from privatisation could come from competitive pressures to keep prices low, but without competition, monitoring would be critical to ensure cost savings. However, most US local governments do not monitor their contracts. On average less than half of governments responding to nationwide surveys in the US report monitoring their contracts (Warner and Hefetz Citation2020). In a competitive market, pressures from alternative suppliers would help keep prices down and service quality up. But in local government service markets, managers spend much of their time trying to create and bolster a market to which they could contract out, and this time comes at the expense of monitoring (Girth et al. Citation2012).

These market failures of privatisation require that local government play a market management role. If competitive pressures do not remain in the market once a contract is let, then government must create that competition over time. This is done through reverse privatisation, i.e., contracting back in previously privatised services. Thus reverse privatisation or remunicipalization can be understood as the opposite side of the same coin as privatisation, e.g., part of a market management process.

The first empirical paper on reverse privatisation in the US looked at local governments across New York State in 1997 and found that 8% of service delivery was in the form of reverse privatisation (Warner and Hebdon Citation2001). The authors found local governments engaged in a complex array of contracting options – new contracting out to for profits, non-profits and other governments, and contracting back in when those contracts failed. This research moved the issue of privatisation from the notion of a single option, to one among several service delivery alternatives, used in combination.

The first national study of contract reversals in the US was conducted by Hefetz and Warner (Citation2004). It used a transaction cost framework and found that contracting back in was often a substitute for monitoring. What was interesting about this study was that rates of privatisation reversals and new contracting out where high in the same services, suggesting both contracting out and contracting back in were part of a process of experimentation at the margin. For example, services like building maintenance, legal services and street repair were the highest in both new contracting out and contracting back in. Subsequent US studies have also used a transaction costs framework (Brown and Potoski Citation2004; Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2008; Hefetz and Warner Citation2007; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010; Warner and Hefetz Citation2012, Citation2020).

The market management role of local government is not dissimilar to the market management role played by private firms, where contract reversals are also quite common. ‘Insourcing’ in the private sector, is driven by concerns with costs, quality and control. The need for internal knowledge of the workings of the supply chain, and to have the ability to manage risk has led many private sector firms to insource previously outsourced contracts (Deloitte Citation2005). For the public sector there are a broader range of concerns to manage – not just cost and quality – but also public interests and public values (Hefetz Citation2016; Bel, Brown, and Warner Citation2014).

Work on public sector contracting has elaborated a broader set of measures beyond monitoring and contract management. These include attention to the level of competition and the level of citizen interest in the specific local government market, both of which have been measured and modelled empirically on national samples of US local governments (Hefetz and Warner Citation2007, Citation2012; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010). Social choice offers a broader frame for understanding these reverse privatisation processes, and was used by Hefetz and Warner (Citation2007) in their analysis of US contracting dynamics from 1997–2002. They found that citizen satisfaction played as important a role as market management in explaining levels of privatisation reversals. A later study found similar results for the period 2002–2007 (Warner and Hefetz Citation2012). Hebdon and Jalette (Citation2008) also used a social choice approach in their measures of contracting dynamics in Canada.

Market management in the US also requires attention to place characteristics. By definition local government service delivery is local, so characteristics of the regional market matter. Suburbs have been the most attractive market for privatisation in the US because they have higher income and many similar sized municipalities to serve (Hefetz, Warner, and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2012; Joassart-Marcelli and Musso Citation2005). Larger cities tend to have more remunicipalization because that requires capacity to bring work back in house. Rural areas lag in both privatisation (due to their lack of attractiveness to private providers) and in reversals (due to lack of capacity to bring work back in house) (Hefetz and Warner Citation2007; Warner and Hefetz Citation2012).

Remunicipalization – Political or Pragmatic?

The resurgent interest in remunicipalization since the Great Recession, is driven in part by an interest in whether this might be a politically transformative moment (Lobina Citation2017; McDonald and Swyngedouw Citation2019). In the context of rising fiscal stress and austerity pressures on the state, could remunicipalization be a form of pushback against neoliberal attacks on the state (Warner and Clifton Citation2014)? Some case studies suggest this current ‘wave’ of remunicipalizations may be just that, as localities seek to regain public control over services. Cases in France, Germany and Jakarta (Lobina, Weghmann, and Marwa Citation2019a; Lobina, Weghmann, and Nicke Citation2019b) have been presented as politically transformative. Other scholars have viewed cases in Spain, the Netherlands, France and Germany as a combination of market management and political dynamics (Albalate et al. Citation2021; Angel Citation2021; Gradus, Schoute, and Budding Citation2021; Bel and Sebő Citation2020; Fitch Citation2007; Chong, Saussier, and Silverman Citation2015).

US scholars using large sample empirical evidence find remunicipalization to be primarily a tool of market management, as governments use both privatisation and its reverse in a complementary manner to manage transaction costs (Hefetz and Warner Citation2004; Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2008). Reversals can be used to build competition in the market for public services (Levin and Tadelis Citation2010; Hefetz, Warner, and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2012), as a substitute for monitoring (Girth et al. Citation2012), as a response to labour pressures (Warner and Hefetz Citation2020), and to ensure public interests in the process of service delivery are addressed (Hefetz and Warner Citation2007; Warner and Hefetz Citation2012). International studies find remunicipalization often takes the form of corporatisation, so market principles are instilled inside the service delivery (Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2021). When viewed as part of a market management process, both privatisation and its reverse can be studied in a dynamic way, and some international studies include both privatisation and remunicipalization in the analysis yielding insights into the role of transaction costs, market structure, political and regulatory power (Albalate and Bel Citation2021; Gradus, Schoute, and Budding Citation2021; Gradus and Budding Citation2020; Chong, Saussier, and Silverman Citation2015).

What is interesting about the US work is that party politics so rarely plays a role. While some scholars use voting for president as a proxy for local politics (Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke Citation2008), it is a poor measure of local politics in the US. At the local government level, elections are often non-partisan in the US (Aldag Citation2019). When actual local measures of local political climate are included, we find no effect on remunicipalization (Warner and Aldag Citation2021). This is in contrast to most European studies of privatisation (Bel and Fageda Citation2017). In the US where public officials may voice support for privatisation in political campaigns, the decision to privatise local services is a more pragmatic one. Managers look for cost savings while maintaining service quality. Any service delivery alternative must meet these two goals. Indeed nationwide surveys of local government show these are the top two reasons for privatisation reversals – failure to deliver cost savings and problems with service quality. Less common are political pressures to bring work back in house. More common are efforts to improve service delivery from within the local government organisation – by managers and line workers. See .

Table 1. US Local Government Motivations for Contracting Back In.

Pragmatic municipalism argues that governments will also manage labour interests. Unions, which are generally opposed to privatisation, could be a source of political pressure against privatisation and for remunicipalization (Savas Citation1987; McDonald Citation2018). Actual measures of the level of unionisation at the local level are hard to find, but a 2012 nationwide survey measured unionisation levels and found that US local governments with higher unionisation rates actually have higher rates of new contracting out and lower rates of remunicipalization (Warner and Hefetz Citation2020). This is the opposite of what one might expect, and suggests that pragmatic managers manage labour as well as contracts. Theories of union pressures note that unions decrease organisational slack and thus pressure government to manage better (Slichter, Healy, and Livernash Citation1960). Monitoring is one part of management, but the analysis found that only in unionised governments did monitoring have a significant effect on contracting – and it was associated with more new contracting and fewer reversals (Warner and Hefetz Citation2020). Thus, unionised governments force better market management practices on local government. Unions are part of the political interests that encourage better management and make pragmatic municipalism work.

Pragmatic municipalism argues that governments will balance service needs even in the face of fiscal stress (Kim and Warner Citation2016). In contrast to the claims of austerity theorists who argue that fiscal stress will lead to more privatisation (Peck Citation2014; Donald et al. Citation2014), rates of privatisation in the US have not grown since the Great Recession (Kim Citation2018). Indeed the most recent US nationwide surveys in 2017 find even stronger support for the pragmatic municipalism thesis as local governments balance fiscal stress, community needs and new forms of service delivery (Warner, Aldag, and Kim Citation2021a). Intermunicipal cooperation, as a more public form of contracting, has been growing, and in 2017 it became the more common service delivery alternative than privatisation (Warner, Aldag, and Kim Citation2021b). Intermunicipal cooperation has many of the benefits of privatisation in terms of reaching potential economies of scale (by broadening the service area), but it maintains public control (Bel and Gradus Citation2018). A comparison of the motivators for intermunicipal cooperation as compared to for profit contracting shows a more public value orientation (Kim Citation2018). While both privatisation and intermunicipal cooperation are used to save costs, cooperation is also invoked to improve regional collaboration and service equity. These broader regional equity goals are more common in US studies than in Europe, where cost savings is a primary focus of inter-municipal contracting (Bel and Warner Citation2015). Some include new inter-municipal partnerships in their definition of remunicipalization (Transnational Institute Citation2021). In the US inter-municipal contracting has been found to be more stable than contracting to for profit providers, so reversals are lower (Warner Citation2016). This may be because values are more similar when both principals are public.

Understanding Trends

What are the trends in new contracting and remunicipalization? The US is the only country that has trends data over time, based on surveys conducted every five years by the International City/County Management Association of all US municipalities over 2500 population. Hefetz and Warner (Citation2004) developed a methodology for combining survey responses over time. They take the common survey respondents over two time periods and measure if each service included on the survey is provided the same way as in the previous time period. See .

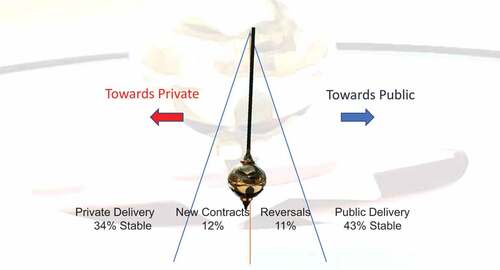

Most services are stable public delivery and the second largest group is stable contracts. At the margins we see new contracting out and contracting back in. These tend to be about equal – at around 10% of service delivery. Over time the percentage of services that are stable public has declined while the percentage that are stable contracts has grown. This suggests a slight shift towards more contracting, not less. What is interesting about these trends is that neither new contracting nor remunicipalization have grown over time, rather they remain relatively equal as part of a market management process of experimentation at the margin. For example, from 2012 to 2017, the most recent period for which data are available, 43% of services are in stable public delivery, 34% in stable contracts (to for profit, non profit and other government providers) and 12% are in new contracts and 11% are reversals ().

Figure 2. Contracting Dynamics, US Local Governments, 2012-17.

These US results stand in contrast to some recent work that argues we are in a wave of remunicipalizations around the world (Kishimoto, Petitjean, and Steinfort Citation2017). This discrepancy could be explained for several reasons. First, US local governments never privatised that much in the first place. The majority of US local government service delivery remains in public delivery, so there is not as much to reverse. Second, the TNI data base of remunicipalization (Transnational Institute Citation2021) is a crowdsourced data base designed to profile remunicipalization cases. As more cases are sought, more are found. There is no longitudinal comparison nor any counterfactual (e.g., level of new contracting) to create meaningful comparison. What the data base does provide is case study evidence on factors leading to remunicipalization. A recent study of 72 of the US cases on water delivery in the TNI data base found that these cases were mostly driven by pragmatic reasons (Hanna and McDonald Citation2021). Indeed, lack of cost savings is a primary reason for privatisation reversals in the water sector, as most recent studies in the US find higher prices with private deliverers (Beecher and Kalmbach Citation2013; Wait and Petrie Citation2017; Zhang et al. Citation2022).

Actors, Regulation and Financialization

Araral’s (Citation2009b) framework focuses not just on the characteristics of the service, but also the range of actors and the institutional structure. Recent research on drinking water delivery in the US has emphasised the dichotomy of public and private is too simple, as there are a range of organisational and management forms – special districts, corporatized public agencies, cooperatives – that provide water services (Onda and Tewari Citation2021; Pierce and Gmoser-Daskalakis Citation2021). Research in Italy has focused on mixed public/private firms and a broader range of performance criteria for water systems – cost, affordability, environmental sustainability, etc. (D’Amore, Landriani, and Lepore Citation2021). However, as finance becomes more important in the water sector, cases from Latin America show that even public water systems are giving more institutional emphasis to financial factors than social criteria (Almeida and Hungaro Citation2021; Santos Citation2021). This has led scholars to outline a broader social efficiency framework for water benchmarking (McDonald Citation2016) and call for spatial equity in performance measures (Carolini and Raman Citation2021). For example in Pittsburgh, PA, after private management was cancelled, social movements pushed for more safety, quality and affordability in the city’s water system (Gonzalez Rivas and Schroering Citation2021).

Increasing financialization in the water sector creates pressures both for new privatisation and for remunicipalization. The case study of water municipalisation in Missoula, Montana illustrates the increasing power of financial interests (Mann and Warner Citation2019). The City of Missoula had always had private water, but dissatisfaction with service quality, water rates and inadequate conservation efforts, led the city to try to take over the water system. The case illustrates Araral’s (Citation2009b) framework well. The city faced information and power asymmetries throughout the process and this raised their transactions costs. But as the process extended over time and costs rose, the challenge of maintaining political will grew. These political costs were significant, and the city had to build political will to take back the system. Finally, there were the financial costs. During the municipalisation process the private operator sold the water system to a venture capital firm, so the cost of repurchasing the system rose.

Institutions matter, and the City of Missoula was only one actor in a multiscalar governance system. The state also had a role to play through the Public Utilities Commission. Ultimately the case was decided by a state judge. The city used the process of eminent domain to take back its water system, and they had to pay market value. How market value is determined when the company is being sold for speculative purposes at the same time as the city is attempting to municipalise, brings financialization and power directly into play. Missoula originally offered to buy the water system for $65 million in 2011, but Park Water instead sold to the Carlyle Group for $156 million. Carlyle then sold to Liberty Utilities for $327 million in 2015, in the middle of the condemnation process. In approving the condemnation for eminent domain in 2017 the judge determined a fair value would be $88.6 million, and the city paid this to municipalise its water supply (Mann and Warner Citation2019). While successful, the story of Missoula is a cautionary tale regarding municipal power and the role of private investors and regulators. The city never would have been able to purchase its system after its sale to venture capital firms if a judge had not intervened to set a fair price. Actors and institutional context matter. A similar effort by Apple Valley, CA to buy back its water system from the same company, Liberty Utilities, ultimately ended in defeat (Citizens for Government Accountability Citation2021).

The entrance of venture capital could shift water delivery towards more privatisation in the US in the future, as US water systems have become attractive targets for venture capital. Large investor-owned utilities such as American Water and Essential Utilities’ Aqua America have grown in the US market in part because water is less politicised in the US. But as large investor-owned utilities have gained share in the US market, they have pushed for more favourable regulation. Actors and institutions intersect and financialization and regulation are intertwined. A number of US states have recently enacted regulatory reforms to enhance the attractiveness for private capital. Janney Capital Markets (Citation2013) follows these trends and ranks states on their favourability to private investors. States can enact policies that create a favourable environment for the private sector, such as ‘fair market value’ which values assets above book value, and Distribution System Investment Charges, which are surcharges related to capital costs that enable rate adjustments between rate cases (Kline Citation2018; Beecher Citation2019; Gallos Citation2019). Pennsylvania and New Jersey are leaders in these regulatory reforms, and a study of water prices of the 500 largest city systems in the US found the more favourable regulation for private providers explains one-third of the higher prices with private providers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania (Zhang et al. Citation2022). As of 2019, ten states had passed fair market value legislation, and this is expected to lead to more acquisitions and consolidation in the future (Beecher Citation2019).

US local governments derive their powers from the subnational state, and states have been pre-empting local government power in a broad range of areas – from land use, to local government finance, to broadband (Riverstone-Newell Citation2017). This could affect local government power to remunicipalize in the future. But the Federal government also plays a role, in market regulation and in finance. For example, while broadband is primarily a private service not under municipal control, some municipalities have attempted to provide municipal broadband and then been challenged by state pre-emption (Bravo, Warner, and Aldag Citation2020). They have successfully appealed to the Federal government for intervention from the Federal Communications Commission (Schwarze Citation2018). In addition, the American Rescue and Recovery Act (ARPA) passed in 2021, provides federal funds for municipal investment in water, sewer and broadband and it specifically references municipal and cooperative forms of service delivery (U.S. Department of Treasury Department Citation2021). The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), passed in late 2021, similarly focuses on municipal ownership and does not privilege private investment. Thus, federal funds create potential for more municipal control. Both of these bills have a multi-year time frame. Most communities plan to invest their ARPA funds in water and sewer. Broadband and other more progressive investments are less common (Warner, Kelly, and Zhang Citation2022). While most water and sewer systems are municipally controlled, broadband is primarily private. New forms of public, private and intermunicipal partnerships offer the potential for pragmatic local governments to expand access to broadband in local markets where private actors have shown little interest (Read and Wert Citation2021; Schmit and Severson Citation2021), but these are more likely to be partnership arrangements than municipal ownership.

Conclusion

This paper argues that both privatisation and remunicipalization in the US have been primarily a process of pragmatic market management, as local governments seek to balance costs, community needs and political interests. Most local government services in the US continue to be provided by the public sector, and the rate of both new privatisation and reversals (remunicipalization) is low.

Local governments are pragmatic municipal actors. They must navigate their state context, where increased efforts by private interests may seek regulatory reforms at the state level, which shift the regulatory landscape in favour of private investors. But recent Federal legislation, such as ARPA and IIJA, has shown a preference for municipal control. How local governments balance their own needs and market conditions with these shifts in state and federal policy will determine future trends.

The United States has seen a mostly pragmatic approach to privatisation and remunicipalization. This is because decision-making has been left primarily to local government leaders who balance need, cost and quality to serve their residents. While shifts in finance and in the regulatory framework at the state level could swing the balance more in favour of private investors, new federal infrastructure funds will help local governments balance need, market conditions and political interests in a pragmatic municipalism approach.

Tweet

Pendulum swings between privatisation and remunicipalization in the US local governments reflect contracting, market and citizen interests, as well as regulatory shifts, especially in water services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adler, M. 1999. “Been there, done that! The privatization of street cleaning in nineteenth century New York.“ New Labor Forum 4: 88–99. https://www.proquest.com/docview/237229197?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Albalate, D., and G. Bel. 2021. “Politicians, Bureaucrats and the Public–Private Choice in Public Service Delivery: Anybody There Pushing for Remunicipalization?” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 361–379. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1685385.

- Albalate, D., G. Bel, R. Gradus, and E. Reeves. 2021. “Re-Municipalization of Local Public Services: Incidence, Causes and Prospects.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 87 (3): 419–424. doi:10.1177/00208523211006455.

- Aldag, A. M. 2019. “Who Votes for Mayor? Evidence from Midsized American Cities.” Local Government Studies 45 (4): 526–545. doi:10.1080/03003930.2019.1571997.

- Almeida, R. P., and L. Hungaro. 2021. “Water and Sanitation Governance Between Austerity and Financialization.” Utilities Policy 71: 101229. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101229.

- Angel, J. 2021. “New Municipalism and the State: Remunicipalising Energy in Barcelona, from Prosaics to Process.” Antipode 53 (2): 524–545. doi:10.1111/anti.12687.

- Araral, E. 2009a. “The Failure of Water Utilities Privatization: Synthesis of Evidence, Analysis and Implications.” Policy and Society 27 (3): 221–228. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.10.006.

- Araral, E. 2009b. “Privatization and Regulation of Public Services: A Framework for Institutional Analysis.” Policy and Society 27 (3): 175–180. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.10.008.

- Atuahuene, B. (2020). Predatory Cities, California Law Review https://works.bepress.com/bernadette_atuahene/52/

- Barter, P. A. 2008. “Public Planning with Business Delivery of Excellent Urban Public Transport.” Policy and Society 27 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.09.007.

- Beecher, J. A. (2019). “Corporate Consolidation of Water Utilities: Is Fair Market Value Fair?” https://ipu.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Beecher-Fair-Market-Value-Water-Nov-2019.pdf.

- Beecher, J. A., and J. A. Kalmbach. 2013. “Structure, Regulation, and Pricing of Water in the United States: A Study of the Great Lakes Region.” Utilities Policy 24: 32–47. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2012.08.002.

- Bel, G. 2020. “Public versus Private Water Delivery, Remunicipalization and Water Tariffs.” Utilities Policy 62: 100982. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2019.100982.

- Bel, G., T. Brown, and M. E. Warner. 2014. “Mixed and Hybrid Models of Public Service Delivery.” International Public Management Journal 17 (3): 297–307. doi:10.1080/10967494.2014.935231.

- Bel, G., and X. Fageda. 2017. “What Have We Learned from the Last Three Decades of Empirical Studies on Factors Driving Local Privatisation?” Local Government Studies 43 (4): 503–511. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1303486.

- Bel, G., X. Fageda, and M. E. Warner. 2010. “Is Private Production of Public Services Cheaper Than Public Production? A Meta-Regression Analysis of Solid Waste and Water Services.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29 (3): 553–577. doi:10.1002/pam.20509.

- Bel, G., and R. Gradus. 2018. “Privatisation, Contracting-Out and Inter-Municipal Cooperation: New Developments in Local Public Service Delivery.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1403904.

- Bel, G., and M. Sebő. 2020. “Waste Management Reform: Introducing and Enhancing Competition to Improve Service Delivery.” Waste Management 118: 637–646. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2020.09.020.

- Bel, G., and M. E. Warner. 2015. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Costs: Expectations and Evidence.” Public Administration: An International Quarterly 93 (1): 52–67. doi:10.1111/padm.12104.

- Bravo, N., M. E. Warner, and A. Aldag. 2020. Grabbing Market Share, Taming Rogue Cities and Crippling Counties: Views from the Field on State Preemption of Local Authority. Ithaca, NY: Dept. of City and Regional Planning, Cornell University. http://cms.mildredwarner.org/p/298.

- Brown, T. L., and M. Potoski. 2004. “Transaction Costs and Institutional Explanations for Government Service Production Decisions.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13 (4): 441–468. doi:10.1093/jopart/mug030.

- Brown, T. L., M. Potoski, and D. M. Van Slyke. 2008. “Changing Modes of Service Delivery: How Past Choices Structure Future Choices.” Environment and Planning C, Government & Policy 26 (1): 127–143. doi:10.1068/c0633.

- Carolini, G. Y., and P. Raman. 2021. “Why Detailing Spatial Equity Matters in Water and Sanitation Evaluations.” Journal of the American Planning Association 87 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1080/01944363.2020.1788416.

- Chong, E., S. Saussier, and B. S. Silverman. 2015. “Water Under the Bridge: Determinants of Franchise Renewal in Water Provision.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 31 (suppl_1): i3–39. doi:10.1093/jleo/ewv010.

- Citizens for Government Accountability. (2021). https://www.applevalleycitizens.org/2021/05/11/judge-makes-preliminary-ruling-against-apple-valley-taking-over-water-system/

- Clifton, J., M. E. Warner, R. Gradus, and G. Bel. 2021. “Re-Municipalization of Public Services: Trend or Hype?” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 293–304. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1691344.

- Cumbers, A., and F. Paul. 2022. “Remunicipalisation, Mutating Neoliberalism and the Conjuncture.” Antipode 54 (1): 197–217. doi:10.1111/anti.12761.

- D’Amore, G., L. Landriani, and L. Lepore. 2021. “Ownership and Sustainability of Italian Water Utilities: The Stakeholder Role.” Utilities Policy 71: 101228. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101228.

- Deloitte. 2005. Calling a Change in the Outsourcing Market. New York: Deloitte Consulting.

- Donald, B., A. Glasmeier, M. Gray, and L. Lobao. 2014. “Austerity in the City: Economic Crisis and Urban Service Decline?” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst040.

- Feigenbaum, H., and J. Henig. 1994. “The Political Underpinnings of Privatization: A Typology.” World Politics 46 (2): 185–208. doi:10.2307/2950672.

- Fitch, K. 2007. “Water Privatisation in France and Germany: The Importance of Local Interest Groups.” Local Government Studies 33 (4): 589–605. doi:10.1080/03003930701417627.

- Gallos, P. (2019) Who’s Profiting from Repairs to Aging Water and Sewer Systems, NJ Spotlight News, Sept 12. https://www.njspotlight.com/2019/09/19-09-11-op-ed-whos-profiting-from-repairs-to-aging-water-and-sewer-systems/

- Girth, A. M., A. Hefetz, J. M. Johnston, and M. E. Warner. 2012. “Outsourcing Public Service Delivery: Management Responses in Noncompetitive Markets.” Public Administration Review 72 (6): 887–900. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02596.x.

- Gonzalez Rivas, M. G., and C. Schroering. 2021. “Pittsburgh’s Translocal Social Movement: A Case of the New Public Water.” Utilities Policy 71: 101230. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101230.

- Gradus, R., and T. Budding. 2020. “Political and Institutional Explanations for Increasing Re-Municipalization.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (2): 538–564. doi:10.1177/1078087418787907.

- Gradus, R., M. Schoute, and T. Budding. 2021. “Shifting Modes of Service Delivery in Dutch Local Government.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 333–346. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1630123.

- Hanna, T. M., and D. A. McDonald. 2021. “From Pragmatic to Politicized? The Future of Water Remunicipalization in the United States.” Utilities Policy 72: 101276. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101276.

- Hart, O. D., A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny. 1997. “The Proper Scope of Government: Theory and an Application to Prisons.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (4): 1127–1161. doi:10.1162/003355300555448.

- Hebdon, R., and P. Jalette. 2008. “The Restructuring of Municipal Services: A Canada—United States Comparison.” Environment and Planning C, Government & Policy 26 (1): 144–158. doi:10.1068/c0634.

- Hefetz, A. 2016. “The Communicative Policy Maker Revisited: Public Administration in a Twenty-First Century Cultural-Choice Framework.” Local Government Studies 42 (4): 527–535. doi:10.1080/03003930.2016.1181060.

- Hefetz, A., and M. E. Warner. 2004. “Privatization and Its Reverse: Explaining the Dynamics of the Government Contracting Process.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 14 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1093/jopart/muh012.

- Hefetz, A., and M. E. Warner. 2007. “Beyond the Market Vs. Planning Dichotomy: Understanding Privatisation and Its Reverse in US Cities.” Local Government Studies 33 (4): 555–572. doi:10.1080/03003930701417585.

- Hefetz, A., and M. E. Warner. 2012. “Contracting or Public Delivery? The Importance of Service, Market, and Management Characteristics.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (2): 289–317. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur006.

- Hefetz, A., M. E. Warner, and E. Vigoda-Gadot. 2012. “Privatization and Intermunicipal Contracting: The US Local Government Experience 1992–2007.” Environment and Planning C, Government & Policy 30 (4): 675–692. doi:10.1068/c11166.

- Hertel-Fernandez, A. 2019. State Capture: How Conservative Activists, Big Businesses, and Wealthy Donors Reshaped the American States – and the Nation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hoedeman, O., S. Kishimoto, and M. Pigeon. 2013. Remunicipalization: Putting Water Back into Public Hands. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

- Hood, C. 1991. “A Public Management for All Seasons?” Public administration 69 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x.

- Janney Capital Markets. 2013. “Think Secular, Act Cyclical: The Pragmatist’s Guide to Water.” Equity Research Industry Report, November, 13: 55–57.

- Joassart-Marcelli, P., and J. Musso. 2005. “Municipal Service Provision Choices Within a Metropolitan Area.” Urban Affairs Review 40 (4): 492–519. doi:10.1177/1078087404272305.

- Kim, Y. 2018. “Can Alternative Service Delivery Save Cities After the Great Recession? Barriers to Privatisation and Cooperation.” Local Government Studies 44 (1): 44–63. doi:10.1080/03003930.2017.1395740.

- Kim, Y., and M. E. Warner. 2016. “Pragmatic Municipalism: Local Government Service Delivery in the Great Recession.” Public Administration: An International Quarterly 94 (3): 789–805. doi:10.1111/padm.12267.

- Kim, Y., and M. E. Warner. 2018. “Shrinking Local Autonomy: Corporate Coalitions and the Subnational State.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (3): 427–441. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy020.

- Kishimoto, S., O. Petitjean, and L. Steinfort. 2017. Reclaiming Public Services. how Cities and Citizens are Turning Back Privatization. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

- Kline, K. J. (2018). Water Distribution System Improvement Charges: A Review of Practices, Report No. 18-01, National Regulatory Research Institute, Washington, DC.

- Levin, J., and S. Tadelis. 2010. “Contracting for Government Services: Theory and Evidence from US Cities.” The Journal of Industrial Economics 58 (3): 507–541. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6451.2010.00430.x.

- Lobina, E. 2017. “Water Remunicipalisation: Between Pendulum Swings and Paradigm Advocacy .” In Urban Water Trajectories, edited by Bell, S., Allen, A., Hofmann, P. and Teh, T.-H., 149–161. Cham: Springer.

- Lobina, E., and V. Weghmann. 2021. “Commentary: The Perils and Promise of Inter-Paradigmatic Dialogues on Remunicipalisation.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 398–404. doi:10.1080/17487870.2020.1810473.

- Lobina, E., V. Weghmann, and M. Marwa. 2019a. “Water Justice Will Not Be Televised: Moral Advocacy and the Struggle for Transformative Remunicipalisation in Jakarta.” Water Alternatives 12 (2): 725–748.

- Lobina, E., V. Weghmann, and K. Nicke. 2019b. Water remunicipalisation in Paris. France and Berlin, Germany: PSIRU.

- London, J. D. 2008. “Reasserting the State in Viet Nam Health Care and the Logics of Market-Leninism.” Policy and Society 27 (2): 115–128. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.09.005.

- Mann, C. L., and M. E. Warner. 2019. “Power Asymmetries and Limits to Eminent Domain: The Case of Missoula Water’s Municipalization.” Water Alternatives 12 (2): 725–737.

- McDonald, D. A. 2016. “The Weight of Water: Benchmarking for Public Water Services.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (11): 2181–2200. doi:10.1177/0308518X16654913.

- McDonald, D. A. 2018. “Remunicipalization: The Future of Water Services?” Geoforum 91: 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.027.

- McDonald, D. A., and E. Swyngedouw. 2019. “The New Water Wars: Struggles for Remunicipalisation.” Water Alternatives 12 (2): 322–333.

- OECD. 2016. Fiscal Federalism 2016: Making Decentralisation Work: A Bird’s Eye View of Fiscal Decentralization. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264254053-3-en.

- Onda, K., and M. Tewari. 2021. “Water Systems in California: Ownership, Geography and Affordability.” Utilities Policy 72 (3): 101279. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101279.

- Osborne, D. E., and T. Gaebler. 1992. Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley).

- Painter, M., and K. H. Mok. 2008. “Reasserting the Public in Public Service Delivery: The de-Privatization and de-Marketization of Education in China.” Policy and Society 27 (2): 137–150. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.09.003.

- Peck, J. 2014. “Pushing Austerity: State Failure, Municipal Bankruptcy and the Crises of Fiscal Federalism in the USA.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7 (1): 17–44. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst018.

- Pérard, E. 2009. “Water Supply: Public or Private? An Approach Based on Cost of Funds, Transaction Costs, Efficiency and Political Costs.” Policy and Society 27 (3): 193–219. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.10.004.

- Pierce, G., and K. Gmoser-Daskalakis. 2021. “Multifaceted Intra-City Water System Arrangements in California: Influences and Implications for Residents.” Utilities Policy 71: 101231. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101231.

- Ramesh, M. 2008. “Reasserting the Role of the State in the Healthcare Sector: Lessons from Asia.” Policy and Society 27 (2): 129–136. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.09.004.

- Ramesh, M., E. Araral, and X. Wu. 2010. Reasserting the Public in Public Services. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Read, A., and K. Wert. 2021. How States are Using Pandemic Relief Funds to Boost Broadband Access. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts.

- Riverstone-Newell, L. 2017. “The Rise of State Preemption Laws in Response to Local Policy Innovation.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 47 (3): 403–425. doi:10.1093/publius/pjx037.

- Rossi, M. (2021). Socialist Aspirations and Local Realities: Dilemmas in Municipalization and Pseudomunicipalization During Milwaukee’s Socialist Era, paper presented at Unwinding Privatization workshop, Chicago, IL.

- Santos, C. 2021. “Open Questions for Public Water Management: Discussions from Uruguay’s Restatization Process.” Utilities Policy 72: 101273. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101273.

- Savas, E. S. 1987. Privatization: The Key to Better Government. Chatham, NJ: Chatham House Publishers).

- Schmit, T., and R. Severson. 2021. “Exploring the Feasibility of Rural Broadband Cooperatives in the United States: The New New Deal?” Telecommunications Policy 45 (4): 102–114. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102114.

- Schwarze, C. L. 2018. “We Want Wi-Fi: The Fcc’s Intervention in Municipal Broadband Networks.” Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 56 (1): 197–218.

- Slichter, S. H., J. J. Healy, and E. R. Livernash. 1960. The Impact of Collective Bargaining on Management. Vol. 4. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst Press.

- Transnational Institute. 2021. Remunicipalization Data Base. Amsterdam: TNI. https://publicfutures.org/#/index.

- U.S. Department of Treasury. 2021. Interim Final Rule. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Treasury.

- Voorn, B., M. K. Van Genugten, and S. Van Thiel. 2021. “Re-Interpreting Re-Municipalization: Finding Equilibrium.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 305–318. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1701455.

- Wait, I. W., and W. A. Petrie. 2017. “Comparison of Water Pricing for Publicly and Privately Owned Water Utilities in the United States.” Water International 42 (8): 967–980. doi:10.1080/02508060.2017.1406782.

- Warner, M. E. 2008. “Reversing Privatization, Rebalancing Government Reform: Markets, Deliberation and Planning.” Policy and Society 27 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2008.09.001.

- Warner, M. E. 2016. “Pragmatic Publics in the Heartland of Capitalism: Local Services in the United States.” In Making Public in a Privatized World: The Struggle for Essential Services, edited by D. McDonald, 189–202, London: Zed Books.

- Warner, M. E., and A. M. Aldag. 2021. “Re-Municipalization in the US: A Pragmatic Response to Contracting.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 319–332. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1646133.

- Warner, M. E., A. M. Aldag, and Y. Kim. 2021a. “Pragmatic Municipalism: US Local Government Responses to Fiscal Stress.” Public Administration Review 81 (3): 389–398. doi:10.1111/puar.13196.

- Warner, M. E., A. M. Aldag, and Y. Kim. 2021b. “Privatization and Intermunicipal Cooperation in US Local Government Services: Balancing Fiscal Stress, Need and Political Interests.” Public Management Review 23 (9): 1359–1376. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1751255.

- Warner, M. E., and J. Clifton. 2014. “Marketization, Public Services and the City: The Potential for Polanyian Counter Movements.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst028.

- Warner, M. E., and R. Hebdon. 2001. “Local Government Restructuring: Privatization and Its Alternatives.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (2): 315–336. doi:10.1002/pam.2027.

- Warner, M. E., and A. Hefetz. 2012. “In-Sourcing and Outsourcing: The Dynamics of Privatization Among U.S. Municipalities 2002-2007.” Journal of the American Planning Association 78 (3): 313–327. doi:10.1080/01944363.2012.715552.

- Warner, M. E., and A. Hefetz. 2020. “Contracting Dynamics and Unionization: Managing Labor, Political Interests and Markets.” Local Government Studies 46 (2): 228–252. doi:10.1080/03003930.2019.1670167.

- Warner, M. E., P. M. Kelly, and X. Zhang. 2022. “Challenging Austerity Under the COVID-19 State.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, forthcoming. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsac032.

- Williamson, O. E. 1979. “Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations.” The Journal of Law & Economics 22 (2): 233–261. doi:10.1086/466942.

- Zhang, X., M. Gonzalez Rivas, M. E. Warner, and M. Grant. 2022. “Water Pricing and Affordability in the US: Public Vs Private Ownership.” Water Policy 24 (3): 500–516. doi:10.2166/wp.2022.283.