ABSTRACT

The realisation of voice is a particularly challenging aspect of dialogue. The aim of this study is to explore how a microblogging tool creates conditions for the realisation of student voice. Drawing on data collected as part of a larger international study, analysis of student focus group interviews (aged 11–12 years) in two schools in England (n = 36) suggest that the use of a microblogging tool can develop student agency, helping to realise student voice by removing the struggle to capture and maintain the floor and enabling students to become attuned to the ideas of others. However, some students were concerned about the tool's democratic use. Guided by this finding, a detailed micro-analysis of interactions of video data, lesson transcripts and microblog meta-data explores how students' microblogging contributions were heeded by three teachers in one school. We consider the pedagogical implications of these findings, exploring the juxtaposition between a school culture that celebrates individual achievement and the culture of a dialogic classroom. For such classrooms, this research indicates that student commitment to dialogic interaction is encouraged where the ideas of all students are, as far as possible, acknowledged by the teacher and used in developing collective ideas.

Introduction

‘Voice’ is as much a stance as an act (Alexander Citation2020). It can refer both to the act of speaking, in which ideas are verbalised (Lefstein, Pollak, and Segal Citation2020), but also to the right of students in educational settings to express their ideas and the obligation of others to listen and treat them with respect (Alexander Citation2020). This paper draws on data collected as part of a larger four-year (April 2016–August 2020) international study into the dialogic use of a microblogging tool, ‘Talkwall’,Footnote1 investigating how exploratory talk is supported or modified in relation to the use of the tool in the classroom. The design-based research involved collaboration between teachers, researchers and technology developers in Norway and the UK. Talkwall, which was designed for use specifically within the context of a dialogic pedagogy, enables students to easily share, and build upon, each other’s ideas. Empowering student voices is central to a dialogic pedagogy, where increased student participation, in terms of both number of voices and the length of individual turns, is seen as crucial for learning (Segal and Lefstein Citation2016). However, the realisation of student voice is a particularly challenging aspect within classroom dialogue (Lefstein, Pollak, and Segal Citation2020). Ideas must also be heeded by others; if a voice is not heard and attended to it drops out of the conversation and exclusion occurs (Segal, Pollak, and Lefstein Citation2017).

In this paper, we are interested in how student voice relates directly to teaching and learning in classrooms (Warwick et al. Citation2019) and begin by listening to what students have to say about their experiences using Talkwall. This approach enables students to ‘identify and analyze issues related to their schools and their learning that they see as significant’ (Fielding and Bragg Citation2003, 4). As Rudduck and Flutter (Citation2003) found in their work over several years, engaging with students’ perspectives in this way is the first step towards fundamental change in classrooms. Secondly, and in response to students’ experiences, we explore how student voice is realised through Talkwall in the classroom.

Thus, we ask:

How do students perceive the use of a microblogging tool in the sharing and development of ideas in the classroom?

How are students’ microblogging contributions heeded by the teacher in whole class contexts?

We consider the pedagogical implications of these findings, exploring the juxtaposition between a school culture of individual achievement and the culture of a dialogic classroom.

2. Literature review

The sociocultural tradition recognises the importance of language as both a cultural tool (for the development and sharing of knowledge) and a psychological tool (for the development of individual thought) (Vygotsky [Citation1934] Citation1962, Citation1978). Vygotsky’s work espouses an important educational principle, that children learn to think individually through first learning to reason with others. Dialogue is a type of language usage that encourages the development and sharing of knowledge. A dialogic approach to teaching is founded on the idea that knowledge and understanding are collaboratively constructed, predicated on the active involvement of teachers and students in the classroom (Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick Citation2019). However, talk in the classroom is multifaceted, reflecting a range of different purposes and contexts (Warwick and Cook Citation2019). As Mortimer and Scott (Citation2003) argue, teachers may adopt different communicative approaches in different phases of a lesson, all of which have important roles to play. A dialogic pedagogy encourages the development of educationally productive forms of talk in groups such as ‘Exploratory Talk’ (Barnes Citation1976; Mercer Citation1995), or ‘Accountable Talk’ (Wolf, Crosson, and Resnick Citation2006). Such talk enables people to ‘interthink’, facilitating an understanding of one another’s knowledge and perspectives as they co-construct knowledge together (Littleton and Mercer Citation2013). The perceived benefits of a dialogic pedagogy are supported by recent research that suggests positive effects on attainment (EEF Citation2017; Howe et al. Citation2019; Muhonen et al. Citation2018), reasoning and problem-solving skills (T'Sas Citation2018) and the development of student voice (Siddiqui, Gorard, and See Citation2017).

In problematising idealistic approaches to dialogic pedagogy, Lefstein and colleagues argue that the realisation of voice is particularly challenging. Drawing upon Hymes (Citation1996), Blommaert (Citation2006) and Bakhtin (Citation1981), they identify four aspects of voice: ‘(a) opportunity to speak; (b) expressing one’s own ideas; (c) on one’s own terms; and (d) being heeded by others’ (Lefstein, Pollak, and Segal Citation2020, 2), all of which involve some element of struggle, namely ‘the struggle to capture and maintain the floor, the struggle between student and classroom language, and the struggle to have one’s ideas recognized and addressed, among the sea of competing voices’ (2). In response, Alexander (Citation2008) notes the importance of developing a classroom ethos that is collective, reciprocal and supportive, to enable children to voice their opinions, share ideas and learn from their mistakes. As we note elsewhere (Warwick and Cook Citation2019), without the agentic environment that such an ethos creates, students rarely get the opportunity to ‘actively participate in the negotiation of both the content and structure of classroom discourse’ (Aguiar, Mortimer, and Scott Citation2010, 174). Importantly, research over a considerable period has shown that such an ethos can be strongly supported by establishing and respecting ‘ground rules’ for productive classroom talk (Mercer Citation2000), which emphasise reasoning, rational argument, building on the ideas of others, querying, explaining and justification in co-constructing knowledge (Howe and Abedin Citation2013; Mercer and Dawes Citation2008; Mercer et al. Citation2004).

A dialogic ethos in the classroom, supported by ground rules for talk, helps to foster a safe environment in which students are able to articulate their ideas freely. Synthesising recent research on the science of learning and development, Darling-Hammond et al. (Citation2019) argue that school and classroom communities that offer safe, personalised settings for learning help to foster the supportive relationships that enable children to take advantage of learning opportunities. They argue that the development of collaborative community practices helps to strengthen relationships with the result that ‘members feel personally connected to one another and committed to each other’s growth and learning’ (106). This reflects the idea that the classroom might become a ‘community of practice’ (Wenger Citation1998), with shared domains of interest, relationships that acknowledge that we know and can do more collectively than individually, and shared repertoires of resources. Darling-Hammond and colleagues highlight the active role played by the teacher in this process, co-regulating students’ learning behaviours and scaffolding their development towards self-regulation. We argue that this move to the classroom as a community of practice requires dialogic engagement in the classroom, both teacher-to-student and peer-to-peer.

So where might technology in the classroom fit within this picture? The relationship between talk and digital technology use in the classroom is complex. Students are used to interacting or talking using digital technology (e.g. in messaging or via social media sites). The language used for communication in such environments is likely to differ from the talk for learning that is expected in the classroom (Kleine Staarman Citation2009). Nevertheless, the familiarity with such tools may be seen as advantageous as teachers increasingly look to forms of digital technology to support and enhance dialogic interaction in the classroom. Underpinned by a strong collaborative and cooperative ethos, digital tools may be used to enable students to easily share ideas, gain insight into each other’s perspectives, and develop ideas together. For example, externally representing ideas on large screens has been seen to be productive for grounding and sustaining attention, facilitating on task collaborative engagement (Beauchamp and Hillier Citation2014; Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick Citation2019), the visualisation of ‘interthinking’ (Gillen et al. Citation2007) and supporting the co-construction of knowledge (Hennessy Citation2011). Microblogging tools can be used for whole-class sharing in this way, for group activities, or in a combination of both, where group activity leads to whole class sharing. In their review of 21 microblogging studies published between 2008 and 2011, Gao, Luo, and Zhang (Citation2012) concluded that microblogging can promote a collaborative learning environment in which ideas can be easily shared. The sharing of ideas is facilitated through the creation of concise posts, or tangible artefacts, in which thinking can become visible and the focus of shared attention (Mercier, Rattray, and Lavery Citation2015). This suggests that the use of digital tools may help to resolve some of the issues identified by Lefstein regarding the realisation of voice. Indeed, researchers are beginning to turn their attention to the intersection between digital technologies and student voice. A recent special issue of the British Journal of Educational Technology, for example, identified a range of tools used to improve student voice and participation (Manca et al. Citation2017), including the use of email and online forums to facilitate virtual dialogue between teachers and students (Cook-Sather Citation2017). This paper seeks to contribute to this growing area of research interest, focusing on the realisation of student voice in the classroom through dialogic engagement with a specific microblogging tool.

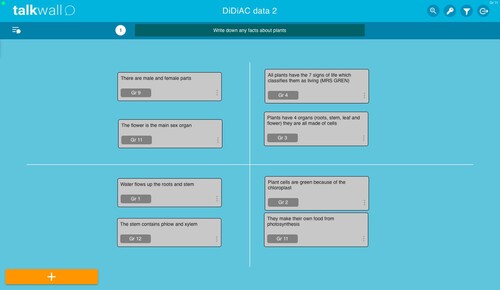

Talkwall is a free cross-platform microblogging system for engaging students in digital classroom interaction. Developed by the University of Oslo, Talkwall’s design is underpinned by a dialogue-based approach to the development of children’s learning that enables ‘thinking together’ (Littleton and Mercer Citation2013), with students easily able to share, and build upon, each other’s ideas. Using Talkwall, a teacher formulates a question or a challenge for students, working in groups, to discuss. Following their collaborative discussion, students post contributions to a shared feed, making their ideas visible to the whole class. Contributions can be interactively arranged in various ways as students pin contributions from the feed to their own group ‘walls’. Group walls can be viewed by the teacher and shared with the whole class via a large screen or projector. The teacher can also pin contributions from the feed to their own wall and share these with the class. Using Talkwall, students can discuss and work with their own ideas or those of other groups.

Analysis of the content and language of students’ posts appears in other papers associated with this research project. Here we explore how a microblogging tool creates conditions for the realisation of student voice through (i) providing the opportunity and a focus for dialogue, both oral and written; and (ii) providing the opportunity for being heeded by others, both within a small working group and more widely across the classroom community.

3. Methodology

3.1. The research study

This study is part of a wider international design-based research project. This paper reports on data collected in two schools in England, where three teachers from each school attended a series of four university workshops focused on sharing effective strategies for promoting classroom dialogue. Collaboratively establishing ground rules for talk with students was an important first step in the research process in schools. In each school, one English, science and geography teacher worked with their class (aged 11–12 years) to integrate Talkwall activities into their usual curriculum.

In each class, the teachers selected two focus groups of three students (n = 36). Three lessons were video recorded and transcribed, with one camera focusing on the interactive whiteboard and the second focusing on one of the two student focus groups. The video data were accompanied by low-inference field notes from the research lessons. Following the completion of the project, the two student focus groups from each class were interviewed. The use of semi-structured group interviews enabled flexible questioning, designed to elicit responses in a more natural, conversational manner. Working with established working groups, and asking more open questions, potentially reduces the possibility of acquiescence response bias, where students give answers that they think the interviewer wants to hear. Conducting the interviews as a group may, of course, lead to some influencing of answers between the students, but the collaborative nature of the discussion was intended to provide a richer dialogue than would be gained from a one-to-one interview (Warwick and Chaplain Citation2017).

The data for this paper is drawn from field notes, video data from lessons, transcripts from lessons and student focus group interviews, in addition to Talkwall meta-data containing logs of interaction from one school. Ethical procedures were followed throughout the research process, informed by BERA (Citation2018) guidelines and the specific requirements of the funder, with voluntary informed consent obtained from all participants. All student names used in this paper have been anonymised.

3.2. Analytical approach

For this paper, each transcribed student focus group discussion was coded by the lead author and key themes arising from the data were derived and revised iteratively (see Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2018). Guided by the key themes emerging from this data, a detailed micro-analysis of interactions of video data, lesson transcripts and Talkwall meta-data was conducted, focused on students’ experiences of sharing ideas using Talkwall in School B. Following Jordan and Henderson (Citation1995), repeated viewings of video extracts enabled a fine-grained analysis exploring how students’ contributions were heeded by the three teachers in whole-class contexts. Further refinement of the data occurred at this stage, when the decision was made to focus on the third research lesson in all three classes. This lesson was chosen because there were whole class discussions of Talkwall in all classes and the Talkwall log data was the most complete for all lessons.

4. Findings

4.1. Student agency and attunement to others

The student interview data reveals how the students saw the role of Talkwall in relation to their collaboration with others in the classroom. In both schools, students frequently spoke about how the tool allowed them to easily share ideas, enabling them to become attuned to the ideas of others as they considered different perspectives. For example:

I would say, I mean it's quite good that we're having the discussions because we get to see everyone else's opinion and everyone else's ideas, because sometimes you agree with those ideas, and think like ‘I've never really thought about that.'

And what I like on Talkwall is you can add to other people’s things, so maybe they've gone like typed in ‘it was built in 18..’ whatever, you could put ‘it was built in 18.. there, by some constructor people’ or whatever.

Yeah. You can add to different people's (—)

ideas to make them better, so it's easier for everybody else as well as you.

I feel like it's easier to concentrate when you're doing it as pairs, and then you're using it on the screen. Because you can pin your ideas and other ideas on your own board, so if you were talking about poetry let's say, you could pin up different bits and then you could put them all together.

You also get more chances to make contributions, because if there's one teacher, she can only pick one person at a time, but then if you're on Talkwall you can just write your answers up and they'll pop up.

Yeah, that's like the same as me. Like I thought that when you put your hands up there's not always a chance that you can be picked, but like when you have Talkwall you can just like put your answer down and it will be seen. And then like people can have opinions, and Miss also mentioned stuff like ‘oh I think that this one is good because … ’ or ‘I don't think this one, because … ’ so like she gets to see them all and give her opinion and other people get their opinions on it. So everyone gets, you know, like their idea out.

It takes quite a while for everyone else's ideas to come up and then they all suddenly come and you're just like ‘we don't have time to read all of this.’

It does take a long time for it to like show up there […] Like sometimes like it would get lost. Because you think it would (send) and like you'd re do it, and like other people would put loads up and then, for example, you might have had a good idea when Miss asked a question and then it would be like at the back after five others and she wouldn't find it.

Yes because it means you don't have to put your hand up and wait, and like sometimes you forget, or you can put it up and then everyone will hear it and understand it because a lot of times a lot of people can't hear you as well.

Unless it's like a really silly comment, and then the teacher will delete it.

Yeah, you can always just delete the comments.

Um, Miss reads out the questions on the board, from Talkwall, and then she'll like say what's good about that and what's bad about it. So, and then she'll give a fair like opinion on how she thinks about that one. And then she also pins them to her wall, the ones she thinks are the best ones.

Yeah.

So she'll pin like maybe three or four to her wall, and then she goes onto other people's walls, which I think is a really good like feature […] that she can check out and put on the board everyone else's walls. So if you've pinned some that you think are really good, she can see the ones that you think are really good as well.

Yeah, and she normally clicks on most boards, and like it really shows how different people think like the best ones are.

I think having it on your own iPad's like good because you can pin your own suggestions up. Like, ‘oh that's a nice idea so we'll put that on.’ And you can also put your own on if you think they're good. Then also when Miss, because you can obviously look on them on her screen because she can click on each group, and when you've like got just yours, she kind of goes ‘well aren't there any other good ideas?’ Like ‘oh yes, but they're the exact same as ours.’ So that just annoys me when we all have the same idea, and we've all put it on.

Like one person gets picked.

Yeah, like the smiley board, when she puts the names up. Because the whole class had that idea, it's just luck.

Basically, when we say something interesting or something, Miss will put our names up. But then say, not that this has happened at all, but if Iris gets picked like ten times in the lesson and everyone else in the whole class says the same thing, then like that's like three achievement points like (—)

for me.

Yeah, but I deserve some achievement points too, so does Laura, so does everyone.

So she's got a smiley face and a sad face, and a smiley face is she wrote my name. That would be one point. If I got a tick that would be two points. If I got two ticks and my name I get an achievement point.

Well on Talkwall it's exactly the same because she picks only one person, but it depends how far down, or how far up you are.

[…] I kind of think Miss needs to scroll down it all and then have a look and put them on.

Beyond simply expressing ideas, student voice also involves the obligation of others to listen to these ideas. Having listened to students’ experiences of sharing their ideas with their teachers through Talkwall, the following section explores in more depth how students’ contributions were heeded by all three teachers as they each taught a single lesson in School B.

4.2. Democratising Talkwall use

4.2.1 English class

In the English class, which was a smaller low ability class of 15 students, there were five groups and a total of 10 contributions posted to the Talkwall feed throughout the lesson. In the first task, the groups had to guess who or what was being described in a riddle read out by the teacher. The groups first discussed and agreed their answers before posting their contributions to Talkwall. Correct answers were pinned to the teacher’s wall. In the second task, students worked in groups to write words describing an object or person from the class text. Each group then had to select one ‘best’ sentence and submit this to Talkwall. At the end of the lesson, the teacher read out each contribution from the feed and the rest of the class had to guess who or what each sentence was describing:

((reading contribution)) ‘I've seen an interesting scene between Zero, Mr Pendanski, Zigzag and Caveman, I need to go and paint my nails.’ That was group 3. What did you write down for that one? Fiona's group, who did you decide that was?

I think it's the Warden.

Warden, correct?

Yeah.

Excellent. What was the clue?

‘I need to go and paint my nails.’

'I need to go and paint my nails’. You didn't actually say ‘I'm the Warden’, you were using that to show her viewpoint and what she was going to go off and do. Well done.

Table 1. Group contributions and how these were attended to by the teacher during whole class discussion.

4.2.2. Science class

The science lesson on plants was a mixed ability class of 26 students. There were 69 contributions throughout the lesson from 12 Talkwall groups ().

Table 2. Group contributions and how these were attended to by the teacher during whole class discussion.

The first Talkwall task was for students to discuss in groups what facts they knew about plants and agree those to become contributions to the feed. The teacher emphasised that she did not want groups repeating the same facts and encouraged the students to review the feed to avoid repetition. At the end of the first task the teacher read through all of the contributions on the feed, giving reasons for deleting some, building on ideas or revoicing them. The teacher took a methodical approach to ensure that all contributions from the feed were included, and every group therefore had at least one contribution read out from the feed ():

Now, I am going to quickly scan through some of them, I'm going to select some of them, ok, and then I'm going to tell you what your next task is […] So I'm going to look through all of them, because I'm not just going to start picking from the top.

OK, now, can I have one of you two explain your wall to me and your reasons for your four groups?

So that one's about reproduction, that one's about (—)

living.

Like living

Being living?

Yeah. That one was about the stem and the water, and that was (—)

What have you got here? Look what you've chosen. You've chosen chloroplasts and photosynthesis, and where does that take place?

In the leaves.

In the leaves. Ok, so again, quite different. Similarities – signs of life. And then you've looked at some organs. Ok, they've looked at some organs.

I'm going to pick one last group. ((Disappointed outcries)) Remember, we're going to be doing this more than once […] I do like the enthusiasm of you guys wanting to show your work though. Ok, let's have a look.

((reading contribution)) ‘Savanah, roots will be longer because it's very dry and it will be hard to find water.’ Now, I'm going to get rid of that one purely because it's not about seed dispersal. Ok? It's right, but it's not seed dispersal.

4.2.3. Geography class

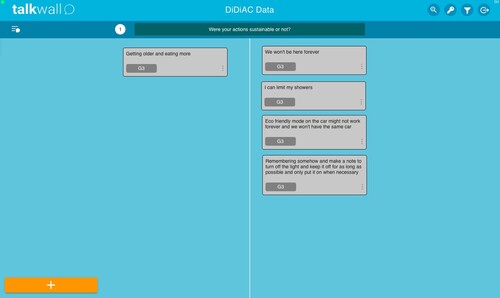

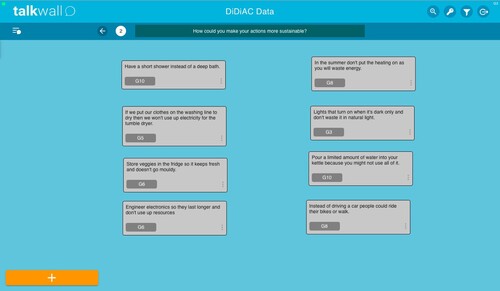

The geography lesson focused on sustainability, with three Talkwall tasks during the course of the lesson. This was a larger mixed ability class of 29 students. There were ten Talkwall groups in total, with 80 contributions created throughout the lesson ().

Table 3. Group contributions and how these were attended to by the teacher during whole class discussion.

The first Talkwall task involved each group adding three contributions from their homework that summarised their impact on the environment during a typical day. The students each took it in turn to add one idea from their homework, again reviewing the feed to ensure that there was no repetition of ideas. At the end of this task the teacher pinned her ‘favourite’ contributions to her wall and commented on these:

Right guys, these are some of my favourite ones that I've picked and you've explained them really well. I particularly like the one that Fi added at the top, so ‘drives to school in an eco-friendly mode in the car, so no extra fumes pollute the environment.’ That's a really good one. And then I liked this one where Vicky's talking about (hands down) eating food that has perhaps been shipped in from other countries and that has to use fuel to get it here. That’s a really good one. Penny leaves her bedroom light on and wastes energy – that's absolutely appalling. Appalling!

Right so, can you talk me through then your ideas. So Claire or Pippa or Poppy, I don't mind. Why have you guys sorted them in this way?

Um

So is this your sustainable or not sustainable column? ((pointing to the right hand side of the wall))

Not sustainable.

So, if you limit your showers, is that sustainable, or is that not sustainable, Claire?

Um.

If you limit the amount of time you spend in the shower? Is that more sustainable or less sustainable?

Less sustainable?

Is it better for the environment or worse for the environment?

Better.

Better, so that would mean it is more (—)

sustainable.

Sustainable, ok. So think about that one. Right, well done girls.

After this discussion, the teacher introduced the third and final Talkwall task of the lesson:

Right guys, what I want you to do now, the last Talkwall task today. ‘How can you make your actions more sustainable?’. So, if you get the car to school, how could that action be made more sustainable? Now I heard some great conversations then when I was walking around, much, much better. Let's make sure the last five minutes worth of discussion is really top quality, so asking each other lots of questions and making sure we're building on ideas and working together as a group. Ok? I'm going to select the best ones for achievement points at the end. Off you go.

Right guys, these ideas are absolutely fantastic and it shows me that you've understood what it means to be sustainable and what things are not sustainable and how we can correct these issues. So, can everyone shut the iPads for me.

5. Discussion

Understanding how students perceive the use of Talkwall for the sharing and development of ideas in the classroom involved us in listening to the voices of the students. What became clear in analysing their views was that, whilst acknowledging constraints, Talkwall was seen as a tool that can be part of the encouragement to participate, collaborate and ‘find their voice’, not least by removing the struggle to capture and maintain the floor (Lefstein, Pollak, and Segal Citation2020). Since its development and intended use is underpinned by a dialogic pedagogy, intended to empower students to play an agentive role in the joint construction of knowledge (Snell and Lefstein Citation2018), the fact that the students themselves felt that they were easily able to share and build on each other’s ideas is an important validating finding for this project.

Talkwall, perhaps most importantly, enables students to become attuned to the ideas of others, widening the social connectivity of the classroom as they access ideas beyond the confines of their own group and explore the perspectives of others, taking shared responsibility for each other’s learning as they build on ideas and made connections between them. However, echoing Darling-Hammond and colleagues (Citation2019) who noted the central role of the teacher in establishing collaborative community practices, students repeatedly spoke about the importance of sharing their ideas with their teacher. Findings from the micro-analysis of all three classes in School B suggest that the students appeared most motivated by having their ideas heeded by the teacher, rather than their peers, suggesting that, for the students at least, the epistemic authority rests with the teacher (Segal, Pollak, and Lefstein Citation2017). As Shaw (Citation2019) noted in her study of two early years classes, engaging with children’s voices can help to illuminate children’s perceptions of inclusion in pedagogical activities, helping to create environments for learning that are more inclusive. In our study, students’ perceptions of inclusion focused on the democratic use of Talkwall, particularly with respect to the struggle to have one’s ideas recognised and addressed by the teacher. Listening to the experiences of students, it was evident that the influx of ideas to the feed could quickly become overwhelming for both teachers and students, creating what Lefstein and colleagues (Citation2018) call a sea of competing voices. The skill of the teacher, as we have seen above, is in finding ways to equitably manage the flow and amount of student input, so that student agency is maintained in tasks and important ideas are not side-lined.

With this in mind, and turning to our second research question, in the science and English lessons the teachers adopted a systematic way of attending to contributions from the feed, thus ensuring that no groups’ ideas went entirely unheeded. When attending to these ideas the teachers either revoiced them, built on them, queried them, invited elaboration or deleted them entirely (whilst explaining why). Pinning contributions and focusing on group walls did not ‘cover’ every idea in both classes; however, because of both teachers’ work with the feed, all groups had at least one idea heeded by the teacher throughout the course of the lesson. In contrast, the third teacher did not work with ideas from the feed. Her use of pinning contributions and focusing on group walls did not address contributions from every group, with the result that two groups did not have any of their ideas heeded by the teacher throughout the course of the lesson. Furthermore, in this class the teacher took a more active role in regulating students’ behaviour through the use of the school’s external rewards system. Here, students sometimes felt that they struggled to have their ideas ‘heard’ by their teacher, whose agenda was more influenced by the backdrop of the wider school culture. The use of achievement points added a competitive element to the task that led to a sense of disenfranchisement among students and a sense that some voices were randomly privileged over others. Allowing voices to drop out of the conversation in this way risks excluding students from the community (Segal, Pollak, and Lefstein Citation2017), undermining the culture of participation and the realisation of student voice.

This raises a potential dilemma, where the dominant culture of the school, in this case geared towards the celebration of individual achievement, may be at odds with the culture of a dialogic classroom, where collaborative endeavour is celebrated because it leads to individual achievement (Vygotsky [Citation1934] Citation1962, Citation1978). In this context it is important to note the impact that the learning environment and classroom ethos have on intrinsic student motivation, with motivation supported where individual competition and comparison is minimised (Blumenfeld, Puro, and Mergendoller Citation1992). Indeed, Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) note that students’ intrinsic motivation for a task may be reduced where extrinsic motivation based on external rewards, used to control students’ behaviour, are employed. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that students expressed a sense of disenfranchisement in the class where a competitive edge to the task was introduced by awarding some groups’ contributions achievement points. Although used to recognise individual achievement, the rewards system clearly reduced students’ intrinsic motivation for the use of Talkwall, leading to a sense of injustice that some groups’ ideas were favoured by the teacher over others.

Interestingly, all three teachers in this discussion were potentially ‘constrained’ by this school’s competitive ethos of individual achievement (Shaw Citation2019), yet two managed to emphasise more strongly the relationship between ‘voice’ and ‘agency’ or ‘action’ (Holdsworth Citation2000, 357), through changes in pedagogical practice that created a more appropriate classroom environment for dialogue and the sharing of ideas (Cook-Sather Citation2020; Ferguson-Patrick Citation2020). In these two classes, students had a sense that the teacher’s use of Talkwall was a generally equitable way of ensuring that they could ‘get their ideas’ to the teacher, enabling their voices to be heard. The collaborative use of Talkwall was itself intrinsically motivating for students in these classes, as evidenced by the students’ responses to having their contributions discussed by the teacher or having their group walls shared with the whole class. Knowing that the two teachers promoting genuinely dialogic interactions with Talkwall were more experienced than the third teacher may be a clue here. Perhaps their professional maturity allowed them to resist the siren call of competition in lessons.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore how a microblogging tool creates conditions for the realisation of student voice through creating purposeful opportunities to speak and be heard by others. Our findings, which are based on a limited data set and therefore cannot be more widely generalised, suggest that the use of a microblogging tool can develop student agency, helping to realise student voice by removing the struggle to capture and maintain the floor and enabling students to become attuned to the ideas of others. However, the democratic use of the tool was identified as an important issue for students, particularly with respect to the struggle to have their ideas recognised and addressed by the teacher. In one school, whilst noting the different approaches adopted by teachers when attending to students’ microblogging contributions, it was the use of achievement points that led to a sense of disenfranchisement among students and a sense that some voices were randomly privileged over others.

Classroom talk, which serves a variety of different purposes, is contextually bound. Our findings suggest that a dialogic classroom ethos may be successfully developed within a wider school culture that celebrates individual achievement. However, this requires changes in pedagogical practice that celebrate the sharing of ideas, emphasising the relationship between voice and agency in collaborative knowledge construction. Furthermore, whilst it is of course prudent to recognise that it is neither feasible nor possible to ensure that every student’s voice will be heard in every whole-class discussion, it is very clear that it is of crucial importance to students that certain voices are not privileged over others (Segal, Pollak, and Lefstein Citation2017). To do so risks the perception by students that the adoption of a more dialogic stance by the teacher (Boyd and Markarian Citation2011) may be less than authentic.

Acknowledgements

The DiDiAC research project is funded by the Research Council of Norway [FINNUT/Project No: 254761] and is registered and approved by the Norwegian data protection service (NSD): http://www.nsd.uib.no/personvernombud/en/notify/index.html. The authors particularly wish to thank the teachers and students who took part in the project for their enthusiastic involvement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Other educational tools that include microblogs, such as Padlet, IdeaBoardz or Google Jamboard, might have been used. However, part of the wider research project was focused on the design-based development of Talkwall as a dialogic tool, with contributions by teachers, researchers and software engineers.

References

- Aguiar, O. G., E. F. Mortimer, and P. Scott. 2010. “Learning from and Responding to Students’ Questions: The Authoritative and Dialogic Tension.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 47 (2): 174–193.

- Alexander, R. 2008. Towards Dialogic Teaching: Rethinking Classroom Talk. 4th ed. Cambridge: Dialogos.

- Alexander, R. 2020. A Dialogic Teaching Companion. London: Routledge.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by M. Holquist, translated by C. Emerson and M. Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Barnes, D. 1976. From Communication to Curriculum. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Beauchamp, G., and E. Hillier. 2014. An Evaluation of iPad Implementation Across a Network of Primary Schools in Cardiff. Cardiff: Cardiff Metropolitan University. http://www.cardiffmet.ac.uk/education/research/Documents/iPadImplementation2014.pdf

- British Educational Research Association [BERA]. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. 4th ed. London. https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018.

- Blommaert, J. 2006. “Ethnopoetics as Functional Reconstruction: Dell Hymes’ Narrative View of the World.” Functions of Language 13 (2): 255–275.

- Blumenfeld, P. C., P. Puro, and J. Mergendoller. 1992. “Translating Motivation Into Thoughtfulness.” In Redefining Student Learning, edited by H. H. Marshall, 207–241. New York: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

- Boyd, M. P., and W. C. Markarian. 2011. “Dialogic Teaching: Talk in Service of a Dialogic Stance.” Language and Education 25 (6): 515–534. doi:10.1080/09500782.2011.597861.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education. 8th ed. London: Routledge.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2017. “Virtual Forms, Actual Effects: How Amplifying Student Voice Through Digital Media Promotes Reflective Practice and Positions Students as Pedagogical Partners to Prospective High School and Practicing College Teachers.” British Journal of Educational Technology 48 (5): 1143–1152.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2020. “Student Voice Across Contexts: Fostering Student Agency in Today’s Schools.” Theory Into Practice 59 (2): 182–191. doi:10.1080/00405841.2019.1705091.

- Darling-Hammond, L., L. Flook, C. Cook-Harvey, B. Barron, and D. Osher. 2020. “Implications for Educational Practice of the Science of Learning and Development.” Applied Developmental Science 24 (2): 97–140. doi:10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- EEF. 2017. Dialogic Teaching – Evaluation Report and Executive Summary. Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Projects/Evaluation_Reports/Dialogic_Teaching_Evaluation_Report.pdf.

- Ferguson-Patrick, K. 2020. “Developing a Democratic Classroom and a Democracy Stance: Cooperative Learning Case Studies from England and Sweden.” Education 3-13, doi:10.1080/03004279.2020.1853195.

- Fielding, M., and S. Bragg. 2003. Students as Researchers: Making a Difference. Cambridge, UK: Pearson Publishing.

- Gao, F., T. Luo, and K. Zhang. 2012. “Tweeting for Learning: A Critical Analysis of Research on Microblogging in Education Published in 2008-2011.” British Journal of Educational Technology 43 (5): 783–801. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01357.x.

- Gillen, J., J. Kleine Staarman, K. Littleton, N. Mercer, and A. Twiner. 2007. “A ‘Learning Revolution’? Investigating Pedagogic Practice Around Interactive Whiteboards in British Primary Classrooms.” Learning, Media and Technology 32 (3): 243–256.

- Hennessy, S. 2011. “The Role of Digital Artefacts on the Interactive Whiteboard in Supporting Classroom Dialogue.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 27 (6): 463–489.

- Holdsworth, R. 2000. “Schools That Create Real Roles of Value for Young People.” UNESCO International Prospect 3: 349–362. doi:10.1007/BF02754058.

- Howe, C., and M. Abedin. 2013. “Classroom Dialogue: A Systematic Review Across Four Decades of Research.” Cambridge Journal of Education 43 (3): 325–356.

- Howe, C., S. Hennessy, N. Mercer, M. Vrikki, and L. Wheatley. 2019. “Teacher–Student Dialogue During Classroom Teaching: Does It Really Impact on Student Outcomes?” Journal of the Learning Sciences 28 (4-5): 462–512. doi:10.1080/10508406.2019.1573730.

- Hymes, D. H. 1996. Ethnography, Linguistics, Narrative Inequality: Toward an Understanding of Voice. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Jordan, B., and A. Henderson. 1995. “Interaction Analysis: Foundations and Practice.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 4 (1): 39–103. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0401_2.

- Kleine Staarman, J. 2009. “The Joint Negotiation of Ground Rules: Establishing a Shared Collaborative Practice with New Classroom Technology.” Language and Education 23 (1): 79–95.

- Lefstein, A., I. Pollak, and A. Segal. 2020. “Compelling Student Voice: Dialogic Practices of Public Confession.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 41 (1): 110–123. doi:10.1080/01596306.2018.1473341.

- Littleton, K., and N. Mercer. 2013. Interthinking: Putting Talk To Work. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Manca, S., V. Grion, A. Armellini, and D. Devecchi. 2017. “Editorial: Student Voice. Listening to Students to Improve Education Through Digital Technologies.” British Journal of Educational Technology 48 (5): 1075–1080.

- Mercer, N. 1995. The Guided Construction of Knowledge: Talk Amongst Teachers and Learners. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Mercer, N. 2000. Words and Minds. London: Routledge.

- Mercer, N., and L. Dawes. 2008. “The Value of Exploratory Talk.” In Exploring Talk in School: Inspired by the Work of Douglas Barnes, edited by N. Mercer, and S. Hodgkinson, 55–72. London: Sage.

- Mercer, N., L. Dawes, R. Wegerif, and C. Sams. 2004. “Reasoning as a Scientist: Ways of Helping Children to Use Language to Learn Science.” British Educational Research Journal 30 (3): 359–378.

- Mercer, N., S. Hennessy, and P. Warwick. 2019. “Dialogue, Thinking Together and Digital Technology in the Classroom: Some Educational Implications of a Continuing Line of Inquiry.” International Journal of Educational Research 97: 187–199. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2017.08.007.

- Mercier, E., J. Rattray, and J. Lavery. 2015. “Twitter in the Collaborative Classroom: Micro-Blogging for In-Class Collaborative Discussions.” International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments 3 (2): 83–99.

- Mortimer, E. F., and P. H. Scott. 2003. Meaning Making in Secondary Science Classrooms. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

- Muhonen, H., E. Pakarinen, A.-M. Poikkeus, M.-K. Lerkkanen, and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2018. “Quality of Educational Dialogue and Association with Students’ Academic Performance.” Learning and Instruction 55 (1): 67–79.

- Rudduck, J., and J. Flutter. 2003. How to Improve Your School: Giving Pupils a Voice. London and New York: Continuum Press.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78.

- Segal, A., and A. Lefstein. 2016. “Exuberant, Voiceless Participation: An Unintended Consequence of Dialogic Sensibilities?” Contribution to a Special issue on International Perspectives on Dialogic Theory and Practice, edited by Sue Brindley, Mary Juzwik, and Alison Whitehurst. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 16: 1–19. http://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2016.16.02.06.

- Segal, A., I. Pollak, and A. Lefstein. 2017. “Democracy, Voice and Dialogic Pedagogy: The Struggle to be Heard and Heeded.” Language and Education 31 (1): 6–25. doi:10.1080/09500782.2016.1230124.

- Shaw, P. A. 2019. “Engaging with Young Children’s Voices: Implications for Practitioners’ Pedagogical Practice.” Education 3-13 47 (7): 806–818. doi:10.1080/03004279.2019.1622496.

- Siddiqui, N., S. Gorard, and B. H. See. 2017. Non-Cognitive Impacts of Philosophy for Children. Durham, NC: School of Education, Durham University.

- Snell, J., and A. Lefstein. 2018. “‘Low Ability’, Participation, and Identity in Dialogic Pedagogy.” American Educational Research Journal 55 (1): 40–78.

- T'Sas, J. 2018. “Learning Outcomes of Exploratory Talk in Collaborative Activities.” PhD. diss., University of Antwerp.

- Vygotsky, L. (1934) 1962. Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Edited by M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, E. Souberman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Warwick, P., and R. Chaplain. 2017. “Research with Younger Children: Issues and Approaches.” In School-based Research: A Guide for Education Students, edited by E. Wilson, 3rd ed., 155–172. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Warwick, P., and V. Cook. 2019. “Classroom Dialogue (Section Introduction).” In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Dialogic Education, edited by Neil Mercer, Rupert Wegerif, and Louis Major, 120–123. London: Routledge.

- Warwick, P., M. Vrikki, A. M. F. Karlsen, P. Dudley, and J. D. Vermunt. 2019. “The Role of Student Voice as a Trigger for Teacher Learning in Lesson Study Professional Groups.” Cambridge Journal of Education 49 (4): 435–455. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2018.1556606.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wolf, M. K., A. C. Crosson, and L. B. Resnick. 2006. Accountable Talk in Reading Comprehension Instruction (CSE Technical Report 670). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing.