ABSTRACT

Children’s development during early childhood affects their well-being and educational success, but there are few reliable assessment instruments available. The aim of the study was to develop, pilot and validate an e-assessment instrument for assessing five-year-old children’s development in cognitive processes, learning, language and mathematical skills. The tablet-based instrument was piloted in Estonia in 11 kindergartens with 122 children. The teachers guided the children one by one over several days. The instrument was validated using teachers’ evaluations of the sampled children’s skills. The results showed positive associations in expected skill areas supporting the claim of the instrument being valid for assessing young children’s development.

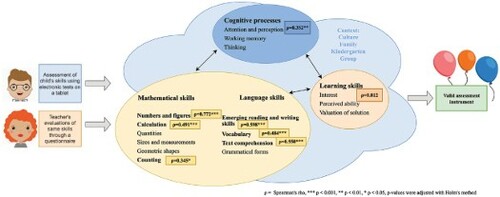

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

There is strong evidence that early learning matters and affects children’s development and coping in later life (Bartik Citation2014; Brownell and Drummond Citation2020; Schoon et al. Citation2015). The first five years of children’s lives are critical to their development (Shuey and Kankaraš Citation2018), with high-quality preschool education affecting academic achievement in later school levels (Fuller et al. Citation2017; Karoly and Whitaker Citation2016; Bakken, Brown, and Downing Citation2017). Even though it is well-acknowledged that early childhood education and care matters, children’s experiences with it vary largely due to their individual characteristics, family background, access and participation in early childhood education (Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission Citation2014).

Monitoring development in early childhood helps to make children’s early learning visible (Dunphy Citation2010). It is important to get feedback at the local and national levels (Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission Citation2014) as well at the programme and individual level (National Research Council Citation2008) in order to understand how to support children’s development effectively. In Estonia, various methods are used to assess young children’s skills, including observations in settings where one or two teachers have to usually look after 20 or even 24 children at a time (Kikas and Lerkkanen Citation2010). Observation as a formative assessment method is common in early childhood education. However, it is also crucial that the observers have extensive knowledge about children’s development and the assessment is manageable in terms of time and resources (Dunphy Citation2010). E-assessment allows teachers to save time on assessment and/or the subsequent scoring and gives them instant feedback. Compared to other assessment methods (e.g. observations or interviews), e-assessment can be more engaging for the children by including visual, audio, and video materials (Adkins Citation2021).

E-assessment instruments are often standardised, making them reliable instruments due to their extensive development period and quality. For a test to be of value to teachers, it should give a clear indication of the child’s strengths and weaknesses which teachers can use to make decisions to support children’s development (Brown and Hattie Citation2012). Although there has been much research on young children’s skills, most studies have focused on a specific developmental domain (see Best et al. Citation2011, for cognitive processes; Collie et al. Citation2019, for social skills; Morgan et al. Citation2019, for cognitive processes; Watts et al. Citation2014, for mathematical skills; Duncan et al. Citation2020, for literacy). Some studies involving more than one developmental area (Fuhs et al. Citation2014; Janus and Offord Citation2007; OECD Citation2020; Pisani, Borisova, and Dowd Citation2018; Fuller et al. Citation2017) have shown the benefits of taking a holistic approach to understanding young children’s development. In addition to traditionally emphasised developmental areas (literacy and numeracy), assessments should include non-academic skills affecting children’s development and well-being, e.g. cognitive, self-regulation, social and emotional skills (National Research Council Citation2008; Shuey and Kankaraš Citation2018).

Even though in Estonia, the curriculum of preschool childcare institutions states that assessment of children’s development is part of the daily teaching and learning process (The Government of the Republic Citation2008/2011/Citation2008/2011), it is not specified what assessment instruments teachers can use and how they interpret the gathered data. Although studies have shown that tablet-based assessment involving storytelling is appropriate for children as young as four or five (Adkins Citation2021; OECD Citation2020), there are no widely available assessment instruments which cover various developmental areas (Pisani, Borisova, and Dowd Citation2018; Reid et al. Citation2014). However, e-assessment instruments should not be merely paper-based tests transferred to digital format but innovative assessment instruments employing the advantages of technology (Day et al. Citation2019). For this reason, the Estonian Education and Youth Board started developing a new electronic assessment instrument for assessing young children’s skills. The instrument does not claim to offer a complete overview of children’s development; rather, it offers information in areas where teachers might need assistance and e-assessment has advantages. It should be kept in mind that a single assessment cannot provide a definitive evaluation of children’s development. Instead, rather various tools should complement each other (Boekaerts and Corno Citation2005). In order to ensure that the results of an assessment instrument are trustworthy, the assessment instrument should be validated (Messick Citation1994). Sireci (Citation2007) has written that validity should be considered when using a test for a particular purpose, but not as a property of the test in question. Evidence that could support or discredit the test scores should be collected to validate a test (Camargo, Herrera, and Traynor Citation2018).

The current work presents the developed tool and describes its validation process involving comparing children’s direct assessments with teachers’ evaluations of the same skills. Other assessment instruments (Alloway et al. Citation2008) or parent questionnaires have been previously used to validate new assessment instruments (Pisani, Borisova, and Dowd Citation2018). Previous research has shown that teachers are quite accurate in evaluating children’s skills (Kowalski et al. Citation2018; OECD Citation2020; Cabell et al. Citation2009) and their evaluations align with actual skills more than parents’ opinions (OECD Citation2020).

1.1. Developing e-assessment instrument for assessing five-year-olds’ development

The development of the e-assessment instrument for five-year-old children was commissioned by the Estonian Ministry of Education. Estonian Education and Youth Board, together with researchers from Tallinn University, started the development of the instrument at the beginning of 2019. The team brought together experts from psychology, early childhood education, and special education. The instrument has been developed drawing on the experience and knowledge gained from the IELS study (Phair Citation2021) and from previous research in Estonia (Männamaa and Kikas Citation2011). The instrument is intended to be used on tablets with teachers guiding the children one-on-one basis. As the instrument is entirely computer-based and includes audio instructions, teachers are only expected to guide the children on using the tablet’s functionality. The instrument is developed to give kindergarten teachers an indication of children’s skill levels, including areas and topics where they outperform expected outcomes or where they might need further support. The tool will be freely available to all kindergarten teachers in Estonia who have attended a training course.

An assessment framework and prototype were created during the first stage of the instrument’s developmental process. The assessment framework includes the theoretical basis for assessing and supporting young children’s development and the areas covered with the instrument. The theoretical background of the assessment instrument draws on the social constructivist approach of Vygotsky (Citation1978), retaining the notion that children construct their knowledge together with parents and peers while the surrounding environment, culture, and society also play a crucial role. In order to support children in this process, their knowledge and skills need to be assessed using appropriate methods (Boekaerts and Cascallar Citation2006).

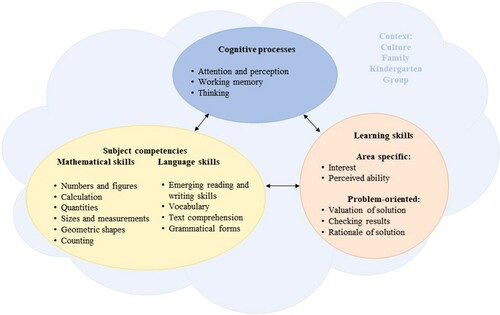

The developmental areas included in the assessment instrument were chosen based on the national curriculum of preschool childcare institutions (The Government of the Republic Citation2008/2011/Citation2008/2011) and previous studies which indicated the competencies needed to become an autonomous self-regulated learner (Boekaerts and Cascallar Citation2006; OECD Citation2020). There are no expected outcomes for five-year-old children in the Estonian preschool curriculum, only for six-seven-year-old children (The Government of the Republic Citation2008/2011/Citation2008/2011). Therefore, in addition to taking the curriculum as a basis, the appropriate level of the instrument was set based on previous similar research (OECD Citation2020). According to the framework, the assessment instrument includes five areas: cognitive processes, mathematical, language, learning, and social skills. Each area is divided into topics and/or constructs to be assessed. The instrument’s prototype includes a continuous thematic story and ideas for assessment items (Kikas et al. Citation2020). The areas of cognitive processes, language and mathematical skills were separated to be able to assess cognitive processes, which are a basis for other developmental areas (Best et al. Citation2011). Learning skills are assessed as previous research has shown the importance of learning and social skills in contributing to a child’s later academic success (McClelland, Acock, and Morrison Citation2006). In the current Estonian curriculum, the cognitive processes and learning skills are presented together as ‘cognitive and learning skills’ and while components of cognitive skills have been specified, components of learning skills have not. As the curriculum is currently under revision to make it more consistent with the curriculum for primary schools, where learning skills have been explicitly brought out (The Government of the Republic Citation2011/2022/Citation2011/2022), the cognitive processes and learning skills were included separately in the instrument. Social skills will be included in the later stage of the development of the instrument.

1.2. The present study

The aim of the present research was to pilot and validate a new electronic instrument for assessing five-year-old children’s development in Estonia. The current study involves the second stage of the instrument’s development, namely, the development of two tests based on the prototype and piloting of the assessment tool in a sample of kindergartens. The tests include four developmental areas: cognitive processes, mathematical, language, and learning skills. The developmental areas and topics included in the present study are shown in . In the areas of cognitive processes and subject competencies, the topics are further divided into sub-topics (constructs), but in learning skills, the topics correspond to the constructs. The four areas are integrated into the tests, and both tests include a continuous story that gives a guide to solving the items (see below in measures).

The present study focuses on the following research question: Are the results obtained with the children’s assessment instrument consistent with the results of the teachers’ questionnaire? Teachers’ evaluations were chosen to validate the instrument as there were no other suitable measures freely available, and previous research has shown that teachers’ evaluations of children’s skills broadly align with children’s actual skills (Kowalski et al. Citation2018; OECD Citation2020; Cabell et al. Citation2009). Teachers do not tend to overestimate results as much as parents (OECD Citation2020). We have set the following hypotheses:

(H1) The assessed developmental areas and topics have moderate positive associations. Previous research has shown that children’s outcomes in different topics in one developmental area as well as across different developmental areas are positively correlated (Reid et al. Citation2014; Best et al. Citation2011; Vitiello and Williford Citation2021; McClelland, Acock, and Morrison Citation2006). Previous research has shown that the associations between topics are somewhat lower for learning skills (Yen, Konold, and McDermott Citation2004);

(H2) The results of the children’s assessment and teachers’ evaluations have moderate positive associations. Previous studies have shown that teachers are quite accurate in evaluating young children’s skills, with teachers’ evaluations being moderately correlated with children’s actual skills (Reid et al. Citation2014; Cabell et al. Citation2009; Kowalski et al. Citation2018; Vitiello and Williford Citation2021) but also based on previous research, we assume that there are some discrepancies between teachers’ ratings and children’s actual skills; this discrepancy could be attributed to rater bias (Hinnant, O’Brien, and Ghazarian Citation2009; Mashburn and Henry Citation2004; OECD Citation2020; Waterman et al. Citation2012);

(H3) The correlations between children’s direct assessment and teachers’ evaluations are stronger in academic skills (language, mathematics) than in cognitive processes and learning skills. As teachers cannot fully rely on the pre-school curriculum which only states outcomes of six-seven-year-old children and studies have concentrated more frequently on academic skills and seldom on cognitive processes and learning skills (McClelland, Acock, and Morrison Citation2006; Kesäläinen et al. Citation2022), teachers have less information about these areas. Also, we expect weaker associations in more complex topics which are on a level not yet expected from five-year-olds and harder for teachers to assess (Mashburn and Henry Citation2004).

1.3. Children’s e-assessment in Estonia

Various e-assessment instruments have been developed in Estonia following the Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020 to focus on a digital turn in education (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2019). The general goal of the strategy was to consider everyone as a learner whose specific needs and abilities should be considered while providing learning opportunities. Five strategic goals were set for 2020: (1) the change in approach to learning considering each learner’s individual and social development, (2) competent and motivated teachers and school leaders, (3) concordance of lifelong learning opportunities with the needs of the labour market, (4) having a digital focus on lifelong learning which supports the use of digital technology in learning and teaching, (5) equal opportunities and increased participation in lifelong learning (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2014). The first and fourth goals are the most relevant in terms of this work as their principles guide the development of the new e-instrument. The goals are continued in a follow-up Education Strategy for 2021-2035, which also emphasises the importance of developing general competencies and digital pedagogy in all educational levels and forms (Ministry of Education and Research Citation2021). Even though both strategies emphasise the importance of continuity through education levels, until now, e-assessment instruments developed in Estonia have only been used in primary and secondary education (Eurydice Citation2020).

Estonia participated in the International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS) in 2018 to get information about various aspects of children’s development and the environmental factors affecting it. The study involved assessing five-year-old children’s development using a specially developed e-assessment instrument. The study showed the possibility and suitability of tablet-based assessments for young children (OECD Citation2020). Estonian teachers were highly motivated to participate in IELS as study administrators. They expressed their opinion that similar tablet-based tools were needed in their work, making it evident that teachers are positively minded towards e-assessment (Meesak Citation2019).

2. Methodology

The aim of the current study was to pilot and validate an electronic instrument which can be used for assessing five-year-old children’s development. The study involves quantitative data collection and analysis methods. Previous research has shown that information regarding young children’s skills can be gathered quantitatively with an e-assessment instrument (OECD Citation2020) and teachers evaluations can be used for validating those results obtained (Cabell et al. Citation2009; Kowalski et al. Citation2018). Quantitative approach allows the researcher to generalise the results to a larger population (Carr Citation1994) and can reduce the burden put on participants without compromising the quality of the research (Rhemtulla and Hancock Citation2016).

2.1. Sample and procedure

The assessment instrument for assessing five-year-old children’s skills is developed by the Estonian Education and Youth Board on behalf of the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research. The approval from ethics committee is not required for nationally developed studies in Estonia. However, the study followed the American Psychological Association’s ethical guidelines (American Psychological Association Citation2017). Consent for the study was given by all parties concerned – kindergartens, teachers, parents and children.

The chairwoman of the board of the Estonian Association of Pre-School Education Leaders (MTÜ Eesti Alushariduse Juhtide Ühendus) was asked to invite the association’s members to participate in the item trial of a new assessment instrument for assessing five-year-old children’s development. The first eight kindergartens who responded by e-mail were able to take part. In addition, two kindergartens from which a teacher and head of studies were involved in developing the items and two kindergartens where Tallinn University Preschool Education Programme’s Bachelor’s-level students worked joined the study. Due to the time-consuming nature of the assessments, only 10 children from each kindergarten could participate. The representatives of the kindergartens gave their written consent for the kindergartens and their teacher’s participation. The children’s parents received a letter informing them about the study’s aims, procedure, and possibilities of participating in the study, as well as the conditions regarding withdrawing their consent. Parents signed an informed consent form for their child’s participation, and each child was also asked for verbal consent to participate before each assessment session. Due to the children’s age, they were asked if they wanted to ‘play a game on a tablet which they can stop at any time’. Only children whose parents had given written consent and who had agreed to the games participated in the study.

The assessments were carried out on a one-on-one basis with the child and the administrator. A tablet computer was used for instrument administration. All the administrators received a manual for carrying out the assessments, and online training was provided. The manual included an introduction to the instrument and instructions for carrying out the assessments. Screenshots of the introductory items, along with specific suggestions, were included. The administrators were instructed to encourage the child to get to know the assessment instrument during the introductory items, while the administrators were allowed to guide and help the child in any way, including explaining the meaning of each button. During the assessment, the administrators were allowed only to answer technical questions (e.g. ‘should I push this button to continue?’).

Each child took part in the assessment for more than one day. There was no maximum time limit, but administrators were instructed not to assess one child longer than 30-minutes at a time. Taking breaks and continuing later the same day or another day was encouraged. Going through the introductory items took children, on average, about five and half minutes (M = 5.33 min, SD = 2.95 min), solving the Home test took on average 38 min (M = 38.25, SD = 8.73) and solving the Shop test took on average 67 min (M = 66.84, SD = 17.87).

The teacher who knew the child the best filled out an online questionnaire about the child’s skills before the assessments. The questionnaire was administered through LimeSurvey and filled out for each child separately. The questionnaire administration period was 2nd November – 9th November 2020. The children’s assessment period was 9th November – 15th December 2020.

In total, 122 children from 11 kindergartens from five different counties participated in the study. Data from 119 children were used for analysis as one child was excluded due to a special need (colour-blindness), and two children did not finish the assessments. The children’s age range was 4 years 10 months to 6 years 1 month (M = 5.54; SD = 0.28). 55% (N = 65) were boys and 45% (N = 54) were girls. The teachers were all women (N = 14) with an average age of 44 (SD = 8.90). The age of the teachers ranged from 25 to 62.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Children’s assessment instrument

The children’s assessment instrument currently includes items to assess cognitive processes, language, mathematical and learning skills, which are divided into two thematic tests. The theme of the first test is ‘children at home’ (Home test), and the second theme is ‘children in the shop’ (Shop test). The two tests have different difficulty levels, with the Shop test including more advanced items. The Home test includes 77 items, and the Shop test includes 101 items. Also, there are 12 introductory items which have to be solved before the tests, the results of which will not be assessed. Each item from the mentioned two tests corresponds to at least one topic and construct, the construct being the smallest component assessed. The instrument included 16 topics, 46 constructs and multiple items corresponding to each topic and construct. In the present work, the sums of the scores for topics (in language and mathematical skills) or skill areas (in cognitive processes and learning skills) were used. All items include only audio instructions and are entirely computer-assessed. Examples of the children’s assessment items for each developmental area are included in Supplementary Materials.

2.2.2. Teacher’s questionnaire

A teachers’ questionnaire was developed based on the concept of assessing five-year-old children’s development (Kikas et al. Citation2020) and the constructs included in the assessment instrument. The questionnaire included five statements on cognitive processes, eleven on language skills, eight on mathematical skills and five on learning skills (see Appendix A, ). The statements on language and mathematical skills were divided into three sub-topics. All the statements had a 3-point scale with an additional option of omitting an answer (1 = ‘not at all’, 2 = ‘partially’, 3 = ‘very well’, 4 = ‘don’t know’). If the fourth option was chosen, the respondent was asked to elaborate on why they could not respond. The option ‘partially’ included specifying information on the statement (e.g. ‘depending on the task’). There was an open-ended option after each skill area to leave comments. The comments were either general (e.g. ‘The child is smart, sharp and broad-minded’, or noted in which situations the child demonstrates their skills (e.g. ‘The child excels in smaller groups of children’; ‘The child might need some extra time in bigger groups’) or indicated if the topic is included in the kindergarten’s curriculum (e.g. ‘We are still in the process of learning letters and sounds’; ‘So large numbers are not used or taught in kindergarten’). As none of the comments affected the accuracy of the teachers’ questionnaire, nor were relevant while considering the children’s assessment results, they were not further analysed.

3. Analysis strategy

Data analysis was conducted with R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team Citation2022). The reliability of the children’s items used for assessing each construct was first tested with Cronbach’s alpha or Kuder – Richardson Formula 20 from [psych] package v[2.2.5] (Revelle Citation2022). The reliability coefficients were calculated for items or questions for each construct. The constructs with a high number of items or questions and low coefficient α < 0.5 (Castro Citation2016; Nunnally Citation1967) or very high success percentage were modified by decreasing items or questions or entirely leaving them out of the construct. Some constructs with a low number of items and low coefficients were still included based on the experts’ decisions and previous research showing that acceptable values used in research differ and decisions should not only rely on the size of the value rather than theoretical and logical conclusions (Kopalle and Lehmann Citation1997; Taber Citation2018). Values as low as α = 0.3 can be considered acceptable, when the number of items is limited and the diverse and engaging breadth of the constructs is more important than achieving high coefficients (Ryff and Keyes Citation1995), as is the case with developing an assessment instrument for young children. Similarly, the Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for initial questionnaire items based on intended factors.

To determine if the children’s assessment and teachers’ questionnaire data were Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) the Little (1988) MCAR test from [naniar] package v[0.6.1] was used (Tierney et al. Citation2021). For the children’s assessment, the data were divided into topics as the test can be performed with a maximum of 50 variables (Yanagida Citation2022). The children’s assessment and teachers’ questionnaire data were then imputed using classification and regression trees from [mice] package v[3.14.0] (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Citation2011).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) from [lavaan] package v[0.6-12] with the Maximum Likelihood Estimation Method (Rosseel Citation2012) was used to examine the structure of the teachers’ questionnaire. First, the option ‘don’t know’ was recorded as a missing value (−99). According to Kline (Citation2016), a CFI (comparative fit index) and TLI (Tucker-Lewis index) values above 0.90 indicate a good model fit, while an SRMR (standardised root mean square residual) value below 0.08 (Hu and Bentler Citation1999) and an RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) value below 0.07 (Steiger Citation2007) can be considered acceptable.

Spearman correlations between children’s assessment results and teachers’ evaluations were then calculated using [Hmisc] package v[4.7-0] (Harrell and Dupont Citation2022) to validate the children’s assessment instrument. Correlations of children’s assessment instruments and teachers’ questionnaires were visualised using [corrplot] package v[0.92] (Wei et al. Citation2021). According to Ellis (Citation2010), correlations below 0.30 are considered low, 0.30–0.50 are considered moderate, and correlations exceeding 0.50 can be considered large.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Reliability of constructs

The number of items for the children’s assessment instrument in each developmental area and topic, descriptive statistics and reliability indicators are included in Appendix A (). The reliability coefficients of the constructs ranged from 0.56–0.91 for cognitive processes, 0.32–0.87 for language skills, 0.49–0.92 for mathematical skills and 0.57–0.64 for learning skills. Only topics having an equivalent in the teachers’ questionnaire were included for further analysis. Similarly, the descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for teachers’ questionnaire are included in the Appendix A ().

4.2. Data imputation

Before further analysis, the data were imputed using classification and regression trees (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Citation2011). The Little (1988) MCAR test showed that the questionnaire data were not MCAR (MCAR test: χ2 (860) = 1044, p < 0.001). The data for cognitive processes (MCAR test: χ2 (276) = 351, p < 0.001), text comprehension (MCAR test: χ2 (94) = 144, p < 0.001), emerging reading and writing (MCAR test: χ2 (769) = 995, p < 0.001), counting (MCAR test: χ2 (110) = 215, p < 0.001), numbers and figures (MCAR test: χ2 (73) = 147, p < 0.001) were not MCAR, whereas the data for vocabulary (MCAR test: χ2 (11) = 7,94, p = 0.718), calculation (MCAR test: χ2 (173) = 218, p = 0.011) and learning (MCAR test: χ2 (88) = 99.0, p = 0.198) were MCAR.

4.3. Latent structure of teachers’ questionnaire

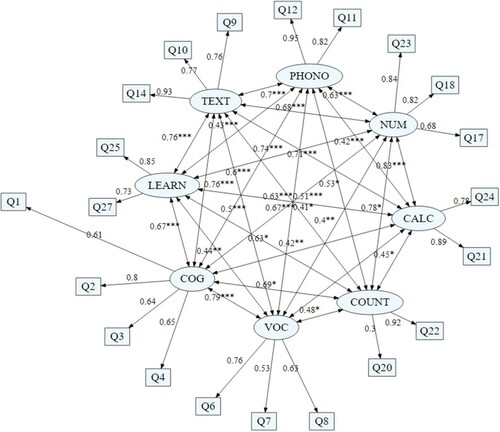

The latent structure of the teachers’ questionnaire was then confirmed using CFA. The model has eight factors corresponding to the initial intended factors. The model fit indices showed good fit between the hypothesised model and the data with CFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.924, RMSEA = 0.063, SRMR = 0.059. The model with standardised coefficients and covariates is shown in . There are significant covariations between all factors of the model.

Figure 2. Questionnaire latent variable model with standardised path coefficients and covariates. Note: COG = cognitive processes, TEXT = text comprehension, PHONO = emerging reading and writing (phonology), VOC = vocabulary, NUM = numbers and figures, CALC = calculation, COUNT = counting, LEARN = learning skills, all covariations are significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

4.4. Construct validity

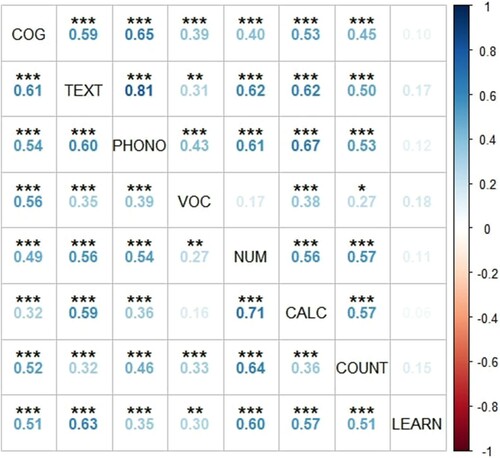

For determining the construct validity of the e-assessment instrument, Spearman correlations were first calculated separately between children’s assessment topics, then teachers’ questionnaire factors and finally between the corresponding topics and factors. The p-values were adjusted with Holm’s method.

The significant Spearman correlations between children’s assessment instrument topics are shown in the upper part of and correlations between teachers’ questionnaire factors in the lower part. The figure shows that all the topics of the children’s assessment are positively and significantly interrelated (except learning skills), with the correlations ranging from moderate (0.30 < ρ < 0.50) to large (ρ > 0.50). The analysis included all the topics of cognitive processes, three out of four topics of language skills, three out of six topics of mathematical skills and all the remaining topics of learning skills. In line with a number of previous studies (Reid et al. Citation2014; Best et al. Citation2011; Vitiello and Williford Citation2021; McClelland, Acock, and Morrison Citation2006) and our H1, children’s outcomes in assessed developmental areas are positively related. Also, similar to previous research showing moderate relations between learning skills and other developmental areas (Yen, Konold, and McDermott Citation2004), correlations for learning skills were low and not statistically significant. This shows that five-year-old children’s interest and perceived ability in an area or topic are not associated with their actual skills indicating that children are happy to show an interest in topics they do not excel in. However, in the case of the teachers’ questionnaire, learning skills were moderately related to other topics, suggesting that teachers perceive higher-performing students to have a higher interest and perceived ability as well. This shows the need for an instrument that allows the children to express their level of interest, compared to teachers evaluating it indirectly. For the questionnaire, all the factors except vocabulary and calculation are significantly positively correlated, with the effect ranging from moderate (0.30 < ρ < 0.50) to large (ρ > 0.50).

Figure 3. Spearman correlations for children’s assessment topics (upper right part of matrix) and teachers’ questionnaire factors (lower left part of matrix). Note: COG = cognitive processes, TEXT = text comprehension, PHONO = emerging reading and writing (phonology), VOC = vocabulary, NUM = numbers and figures, CALC = calculation, COUNT = counting, LEARN = learning skills, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, p-values are adjusted with Holm’s method.

The Spearman correlations between factors identified in CFA and the sums of the children’s assessment items (topics) corresponding to the factors are shown in . As expected in H2, the results of the children’s assessment and teachers’ evaluations were moderately positively associated. The findings are similar to several previous studies (Reid et al. Citation2014; Cabell et al. Citation2009; Kowalski et al. Citation2018; Vitiello and Williford Citation2021). In line with H3, the relations were stronger in academic areas of language and mathematics and moderate in cognitive processes. This indicates that teachers can more accurately assess areas explicitly brought out in the preschool curriculum, making it more important to give them an accurate tool for assessing other skills.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlations between children’s assessment topics and teachers’ questionnaire factors.

The correlations between children’s results and teachers’ evaluations were highest in topics such as numbers and figures, text comprehension, and emerging reading and writing, while the more difficult topics of counting, calculations, and vocabulary were less strongly correlated. This might indicate that teachers tend to under – or overestimate children’s skills (Begeny and Buchanan Citation2010) or are not confident in evaluating skills which exceed the expected level (Mashburn and Henry Citation2004). As previous research has shown that five-year-old children have high mathematical skills (OECD Citation2020), despite the tasks being more difficult than expected in the curriculum, it is important to provide teachers with an instrument that, in addition to assessing the skill level expected from this age group, can give information on topics exceeding it.

There were no significant correlations between children’s assessed learning skills and teachers’ evaluations of those skills, underlining the notion that teachers associate higher interest and perceived ability with children’s skills in other areas, which might not be the case and therefore, teachers are not able to evaluate children’s learning skills accurately. We should provide teachers with an instrument that gives them a more accurate overview of children’s opinions. Previous research has indicated that motivated, confident and attentive children tend to have higher academic results (Yen, Konold, and McDermott Citation2004). For this reason, it is very important for teachers to get information about this area to encourage children to continue learning in the areas that motivate them.

Several limitations should be considered while interpreting the results. First, the kindergartens participating in the study did it voluntarily with a first-come, first-served policy. As the study’s timeframe was limited, only 10 children from each kindergarten could participate. Despite the sample size being rather small, it can still be considered sufficient considering the time-consuming process of assessing each child. Second, there were some discrepancies between the children’s direct assessment results and teachers’ ratings, particularly in learning skills which might suggest that teachers were not able to accurately assess those skills. Previous studies have also shown that the accuracy of kindergarten teachers’ evaluations is moderate (Begeny and Buchanan Citation2010; Kowalski et al. Citation2018; Vitiello and Williford Citation2021), and teachers are not very accurate in identifying children at risk (Cabell et al. Citation2009). However, it could also indicate problems with questions. Thus, further studies are needed to assess children’s learning skills with different methods (observations, interviews) and validate the adequacy of the questions used in this instrument.

5. Conclusion

The results of the current study confirm the reliability and construct validity of the new e-assessment instrument for assessing young children’s skills in four areas. The present work contributes to the area of early learning studies, showing the relations between children’s developmental areas as well as offering a practical outcome of a validated assessment instrument. The research showed that e-assessment can be used for assessing young children’s skills as five-year-olds were successfully able to solve the items on a tablet and their results broadly aligned with teachers’ evaluations making way for similar assessments to be carried out in other countries. At the same time, the results showed that using common methods such as observations, teachers might not be able to accurately assess all skill areas, thus showing the need for varied methods and instruments to be available to kindergarten teachers.

The instrument provides information on emergent language and mathematical skills that teachers are more accustomed to evaluating, as well as on cognitive processes and learning skills that teachers might not feel as confident to assess or might assess inaccurately. Items for assessing social skills will be added to the instrument. The use of the e-assessment tool helps teachers assess the child’s development in certain areas, which also supports the implementation of the curriculum at the level of both the kindergarten group and the institution. The instrument is tablet-based, entirely computer-assessed, includes audio instructions and will be freely accessible to all teachers in Estonia. The instrument helps teachers get an overview of children’s development in areas and topics where direct e-assessment has advantages compared to other measures used.

As some items were further developed or added to the instrument, their properties should be analysed as well. In the next stage of the development, a study with a larger and more representative sample should be carried out. Also, parents should be involved in a study alongside teachers to get information about other aspects of children’s development and from all people involved in children’s lives. In the future, a study could be carried out to determine the consistency of the children’s direct assessment results over time.

Supplementary_logonew.jpg

Download JPEG Image (578.2 KB)Supplementary_Materialsnew.docx

Download MS Word (542.3 KB)Table_A3new.docx

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Table_A2new.docx

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Table_A1new.docx

Download MS Word (16.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the kindergartens, teachers, study administrators, children and their families who participated in the study and as well other experts involved in developing the instrument, namely Tiiu Tammemäe, Maire Tuul, Astra Schults and Natalia Tšuikina.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

The current research is based on the Estonian Education and Youth Board’s project of developing an e-assessment instrument for assessing five-year-old children’s skills. This article was supported by the Research Fund of the School of Educational Sciences at Tallinn University through project ‘Research group for studying the kindergarten learning environment and teachers’ teaching practices’ under grant [number 120_TA3221 ] and by the European Regional Development Fund through an ASTRA measure project ‘TLU TEE or Tallinn University as the promoter of intelligent lifestyle’ under grant [number 2014-2020.4.01.16-0033].

The current research is based on the Estonian Education and Youth Board’s project of developing an e-assessment instrument for assessing five-year-old children’s skills. This article was supported by the Research Fund of the School of Educational Sciences at Tallinn University through project ‘Research group for studying the kindergarten learning environment and teachers’ teaching practices’ under grant [number 120_TA3221 ] and by the European Regional Development Fund through an ASTRA measure project ‘TLU TEE or Tallinn University as the promoter of intelligent lifestyle’ under grant [number 2014-2020.4.01.16-0033].References

- Adkins, Deborah. 2021. “Digital Self-Administered Assessments: The Utility of Touch Screen Tablets as a Platform for Engaging, Early Learner Assessment.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 19 (4): 500–515.

- Alloway, Tracy P., Susan E. Gathercole, Hannah Kirkwood, and Julian Elliott. 2008. “Evaluating the Validity of the Automated Working Memory Assessment.” Educational Psychology 28 (7): 725–734. doi:10.1080/01443410802243828.

- American Psychological Association. 2017. “Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct”, 12–14. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bakken, Linda, Nola Brown, and Barry Downing. 2017. “Early Childhood Education: The Long-Term Benefits.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 31 (2): 255–269. doi:10.1080/02568543.2016.1273285.

- Bartik, Timothy J. 2014. From Preschool to Prosperity: The Economic Payoff to Early Childhood Education. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E: Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

- Begeny, John C., and Heather Buchanan. 2010. “Teachers’ Judgments of Students’ Early Literacy Skills Measured by the Early Literacy Skills Assessment: Comparisons of Teachers With and Without Assessment Administration Experience.” Psychology in the Schools 47 (8): 859–868. doi:10.1002/pits.20509.

- Best, John, R. Patricia, H. Miller, and Jack A. Naglieri. 2011. “Relations between Executive Function and Academic Achievement from Ages 5 to 17 in a Large, Representative National Sample.” Learning And individual Differences 21 (4): 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.007.

- Boekaerts, Monique, and Eduardo Cascallar. 2006. “How Far Have We Moved Toward the Integration of Theory and Practice in Self-Regulation?” Educational Psychology Review 18 (3): 199–210. doi:10.1007/s10648-006-9013-4.

- Boekaerts, Monique, and Lyn Corno. 2005. “Self-Regulation in the Classroom: A Perspective on Assessment and Intervention.” Applied Psychology 54 (2): 199–231. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x.

- Brown, G.T.L., and J. Hattie. 2012. “The Benefits of Regular Standardized Assessment in Childhood Education.” In Contemporary Debates in Childhood Education and Development, edited by S. Suggate, and E. Reese, 287–292. London: Routledge.

- Brownell, Celia A., and Jesse Drummond. 2020. “Early Childcare and Family Experiences Predict Development of Prosocial Behaviour in First Grade.” Early Child Development and Care 190 (5): 712–737. doi:10.1080/03004430.2018.1489382.

- Cabell, Sonia Q., Laura M. Justice, Tricia A. Zucker, and Carolyn R. Kilday. 2009. “Validity of Teacher Report for Assessing the Emergent Literacy Skills of At-Risk Preschoolers.” Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools 40 (2): 161–173. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2009/07-0099).

- Camargo, Sandra Liliana, Aura Nidia Herrera, and Anne Traynor. 2018. “Looking for a Consensus in the Discussion about the Concept of Validity: A Delphi Study.” Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences 14 (4): 146–155. doi:10.1027/1614-2241/a000157.

- Carr, Linda T. 1994. “The Strengths and Weaknesses of Quantitative and Qualitative Research: What Method for Nursing?” Journal of Advanced Nursing 20 (4): 716–721. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20040716.x.

- Castro, Salvador. 2016. Classical Test Theory (CTT).” In RPubs. https://rpubs.com/castro/ctt

- Collie, Rebecca J., Andrew J. Martin, Natasha Nassar, and Christine L. Roberts. 2019. “Social and Emotional Behavioral Profiles in Kindergarten: A Population-Based Latent Profile Analysis of Links to Socio-Educational Characteristics and Later Achievement.” Journal of Educational Psychology 111 (1): 170–187. doi:10.1037/edu0000262.

- Day, Jamin, Kate Freiberg, Alan Hayes, and Ross Homel. 2019. “Towards Scalable, Integrative Assessment of Children’s Self-Regulatory Capabilities: New Applications of Digital Technology.” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 22 (1): 90–103. doi:10.1007/s10567-019-00282-4.

- Duncan, Robert, J. Yemimah, A. King, Jennifer K. Finders, James Elicker, Sara A. Schmitt, and David J. Purpura. 2020. “Prekindergarten Classroom Language Environments and Children’s Vocabulary Skills.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 194: 104829. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2020.104829.

- Dunphy, Elizabeth. 2010. “Assessing Early Learning through Formative Assessment: Key Issues and Considerations.” Irish Educational Studies 29 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/03323310903522685.

- Ellis, Paul D. 2010. The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes: Statistical Power, Meta-Analysis, and the Interpretation of Research Results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eurydice. 2020. “Estonian Standard-Determining Tests in Maths and Sciences Take Place Online.” In Eurydice.

- Fuhs, Mary Wagner, Kimberly Turner Nesbitt, Dale Clark Farran, and Nianbo Dong. 2014. “Longitudinal Associations between Executive Functioning and Academic Skills Across Content Areas.” Developmental Psychology 50 (6): 1698–1709. doi:10.1037/a0036633.

- Fuller, Bruce, Edward Bein, Margaret Bridges, Yoonjeon Kim, and Sophia Rabe-Hesketh. 2017. “Do Academic Preschools Yield Stronger Benefits? Cognitive Emphasis, Dosage, and Early Learning.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 52: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2017.05.001.

- Harrell, Frank E., Jr., and Charles Dupont. 2022. Package ‘Hmisc’.” In CRAN. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/index.html

- Hinnant, J. Benjamin, Marion O’Brien, and Sharon R. Ghazarian. 2009. “The Longitudinal Relations of Teacher Expectations to Achievement in the Early School Years.” Journal of Educational Psychology 101 (3): 662–670. doi:10.1037/a0014306.

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling 6 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Janus, Magdalena, and David R. Offord. 2007. “Development and Psychometric Properties of the Early Development Instrument (EDI): A Measure of Children’s School Readiness.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement 39 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1037/cjbs2007001.

- Karoly, Lynn A., and Anamarie A. Whitaker. 2016. “Informing Investments in Preschool Quality and Access in Cincinnati: Evidence of Impacts and Economic Returns from National, State, and Local Preschool Programs”, 14–16. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Kesäläinen, Jonna, Eira Suhonen, Alisa Alijoki, and Nina Sajaniemi. 2022. “Children’s Play Behaviour, Cognitive Skills and Vocabulary in Integrated Early Childhood Special Education Groups.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 26 (3): 284–300. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1651410.

- Kikas, Eve, and Marja-Kristiina Lerkkanen. 2010. “Education in Estonia and Finland.” In Perspectives in Early Childhood Education: Diversity, Challenges and Possibilities, edited by Marika Veisson, Eeva Hujala, Manula Waniganayake, Peter K Smith, and Eve Kikas, 33–46. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien: Peter Lang Verlag.

- Kikas, Eve, Tiiu Tammemäe, Maire Tuul, Astra Schults, and Anne-Mai Meesak. 2020. "Viieaastaste laste arengu elektroonilise hindamisvahendi kontseptsioon.” , edited by Anne-Mai Meesak, 5–10. Tallinn: Education and Youth Board.

- Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th ed. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

- Kopalle, Praveen K., and Donald R. Lehmann. 1997. “Alpha Inflation? The Impact of Eliminating Scale Items on Cronbach’s Alpha.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 70 (3): 189–197. doi:10.1006/obhd.1997.2702.

- Kowalski, Kurt, Rhonda Douglas Brown, Kristie Pretti-Frontczak, Chiharu Uchida, and David F. Sacks. 2018. “The Accuracy of Teachers’ Judgments for Assessing Young Children’s Emerging Literacy and Math Skills.” Psychology in the Schools 55 (9): 997–1012. doi:10.1002/pits.22152.

- Männamaa, Mairi, and Eve Kikas. 2011. “Developing a Test Battery for Assessing 6- and 7- Year-Old Children’s Cognitive Skills.” Global Perspectives in Early Childhood Education; Diversity, Challenges and Possibilities 20: 203–216.

- Mashburn, Andrew J., and Gary T. Henry. 2004. “Assessing School Readiness: Validity and Bias in Preschool and Kindergarten Teachers’ Ratings.” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 23 (4): 16–30.

- McClelland, Megan M., Alan C. Acock, and Frederick J. Morrison. 2006. “The Impact of Kindergarten Learning-Related Skills on Academic Trajectories at the End of Elementary School.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 21 (4): 471–490. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.09.003.

- Meesak, Anne-Mai. 2019. “Rahvusvahelisest IELS uuringust uue laste arengu hindamisvahendini.” Ülevaade haridussüsteemi hindamisest 2018/2019. õppeaastal.

- Messick, Samuel. 1994. “The Interplay of Evidence and Consequences in the Validation of Performance Assessments.” Educational Researcher 23 (2): 13–23. doi:10.3102/0013189X023002013.

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2014. “The Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020”, 4–5. Tallinn: Ministry of Education and Research.

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2019. “Digital focus.” Accessed 1 February 2022. https://www.hm.ee/en/activities/digital-focus.

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2021. “Education Strategy 2021-2035”, 19–21. Tallinn: Ministry of Education and Research.

- Morgan, Paul L., George Farkas, Yangyang Wang, Marianne M. Hillemeier, Yoonkyung Oh, and Steve Maczuga. 2019. “Executive Function Deficits in Kindergarten Predict Repeated Academic Difficulties Across Elementary School.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 46: 20–32. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.06.009.

- 2008/2011. National Curriculum for Pre-School Institutions.” In Riigiteataja, RT I 2008, 23, 152. The Estonian Government.

- 2011/2022. “National Curriculum for Primary Schools.” In Riigiteataja, RT I, 12.04.2022, 10. The Estonian Government.

- National Research Council. 2008. “Early Childhood Assessment: Why, What, and How, edited by Catherine E. Snow, and Susan B. Van Hemel, 90–304. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Nunnally, Jum C. 1967. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- OECD. 2020. Early Learning and Child Well-being.

- Phair, Rowena. 2021. “International Early Learning and Child Well-Being Study Assessment Framework.” doi:10.1787/af403e1e-en.

- Pisani, Lauren, Ivelina Borisova, and Amy Jo Dowd. 2018. “Developing and Validating the International Development and Early Learning Assessment (IDELA).” International Journal of Educational Research 91: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2018.06.007.

- R Core Team. 2022. “The R Project for Statistical Computing.” In Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Reid, Erin E., James C. Diperna, Kristen Missall, and Robert J. Volpe. 2014. “Reliability and Structural Validity of the Teacher Rating Scales of Early Academic Competence.” Psychology in the Schools 51 (6): 535–553.

- Revelle, William. 2022. “Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research.”.

- Rhemtulla, Mijke, and Gregory R. Hancock. 2016. “Planned Missing Data Designs in Educational Psychology Research.” Educational Psychologist 51 (3-4): 305–316. doi:10.1080/00461520.2016.1208094.

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. “Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2): 1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Ryff, Carol D., and Corey Lee M. Keyes. 1995. “The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 719–727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

- Schoon, Ingrid, Bilal Nasim, Rukmen Sehmi, and Rose Cook. 2015. “The Impact of Early Life Skills on Later Outcomes”, 64–75. London: UCL Institute of Education.

- Shuey, Elizabeth A., and Miloš Kankaraš. 2018. “The Power and Promise of Early Learning.” doi:10.1787/f9b2e53f-en.

- Sireci, Stephen G. 2007. “On Validity Theory and Test Validation.” Educational Researcher 36 (8): 477–481. doi:10.3102/0013189X07311609.

- Steiger, James H. 2007. “Understanding the Limitations of Global Fit Assessment in Structural Equation Modeling.” Personality and Individual Differences 42: 893–898.

- Taber, Keith. 2018. “The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education.” Research in Science Education 48: 1–24. doi:10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

- Tierney, Nicholas, Di Cook Miles McBain, Colin Fay, Mitchell O’Hara-Wild, Jim Hester, Luke Smith, and Andrew Heiss. 2021. Naniar: Data Structures, Summaries, and Visualisations for Missing Data.” In CRAN. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/naniar/naniar.pdf

- van Buuren, Stef, and Karin Groothuis-Oudshoorn. 2011. “Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R.” Journal of Statistical Software 45 (3): 1–67. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

- Vitiello, Virginia E., and Amanda P. Williford. 2021. “Alignment of Teacher Ratings and Child Direct Assessments in Preschool: A Closer Look at Teaching Strategies GOLD.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 56: 114–123. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.03.004.

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in Society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. London: Harvard University Press.

- Waterman, Clare, Paul A. McDermott, John W. Fantuzzo, and Vivian L. Gadsden. 2012. “The Matter of Assessor Variance in Early Childhood Education—Or Whose Score is it Anyway?” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 27 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.06.003.

- Watts, Tyler W., Greg J. Duncan, Robert S. Siegler, and Pamela E. Davis-Kean. 2014. “What’s Past is Prologue: Relations between Early Mathematics Knowledge and High School Achievement.” Educational Researcher 43 (7): 352–360.

- Wei, Taiyun, Viliam Simko, Michael Levy, Yihui Xie, Yan Jin, Jeff Zemla, Moritz Freidnak, Jun Cai, and Tomas Protivisky. 2021. “Corrplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix.”

- Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission. 2014. “Proposal for Key Principles of a Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care.” In Directorate-General for Education and Culture, European Commission.

- Yanagida, T. 2022. “Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) Test.” Accessed 13 April 2022. https://search.r-project.org/CRAN/refmans/misty/html/na.test.html.

- Yen, Cherng-Jyh, Timothy R. Konold, and Paul A. McDermott. 2004. “Does Learning Behavior Augment Cognitive Ability as an Indicator of Academic Achievement?” Journal of School Psychology 42 (2): 157–169. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2003.12.001.

Appendix A

Table A1. Questionnaire items before analysis.

Table A2. Descriptive statistics and number of items for each topic after initial analysis.

Table A3. Descriptive statistics for initial questionnaire items based on intended factors.