ABSTRACT

This article focuses on children’s play during the pandemic and how some young people responded with hybrid, playful media-making. The Play Observatory was an ESRC-funded project led by UCL and the University of Sheffield, inviting children to make contributions to a national collection of stories, texts and artefacts linked with their play during lockdown. The cultural material generated by children is an important post-pandemic legacy that allows us to argue for informal film-making as a legitimate literacy practice. Insights gained from children’s creative film and animation work inspire new approaches to learning with media described as transludic, in which the characteristics of playful and improvised media production processes are given time and space to unfold.

This article draws on research focusing on children’s play during the pandemic, revealing how some young people responded to the crisis with hybrid forms of play and creative media-making. The Play Observatory (Citation2021), running from 2020 to 2022, was an ESRC-funded project led by UCL, the University of Sheffield and CASA (The Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis). The project invited children and their parents and carers to make contributions to a national collection of stories, texts and artefacts linked with their play during the pandemic. Of particular interest to the authors are the moving images that came to light in our call for contributions. We believe the skills, dispositions and learning associated with creative media activities to be of direct relevance to understanding the lived lives of young people - their concerns and cultural pleasures, and notably the ways in which their intertextual understandings are historically situated. With deeper understandings of children’s perspectives on the pandemic through instances of play, we propose that our insights could serve as blueprints for holistic and agentive approaches to learning and literacy with new media, inclusive of dynamic productive engagements with film and animation.

In the context of serious disruption to everyday routines, the project exposes rich seams of cultural material generated by children that allow us not only to counter deficit narratives of ‘learning loss’ (Harmey and Moss Citation2021; Williamson Citation2021), but to reconsider play with media forms as an important post-pandemic legacy. We present the media texts and comments of four young people, and develop a multi-dimensional theoretical frame through which to understand their informal engagements with film underpinned by play and playfulness. The authors identify an assemblage of digital tools, raw materials, practices, skills and dispositions, which comprise the complex conditions in which meanings were made and shared during the pandemic. We question the ways in which popular cultural forms and media engagements are, in the main, excluded from primary and early secondary children’s formal school experiences, given the drive and sophisticated media learning evident in our data.

Inclusive child-focussed research design

The Play Observatory included a multidisciplinary team of folklorists, child historians, digital media educators, and experts in early years, youth culture, play and spatial analysis. We were driven by an urgent need to document and preserve for future generations the voices of children at a time of global crisis. A range of qualitative approaches and research tools were developed: a child-friendly online survey soliciting play stories and texts; online interviews with child participants and their families to create in-depth case studies of several survey contributors; a youth film-making workshop; and an online display of play exhibits, produced and curated in collaboration with design agency Episod, and the Young V&A. Whilst the team tried to ensure as representative a sample as possible, the fully online nature and scope of the project did not allow for as complete and diverse a data set as we might have wished; neither was it the case that all children expressed positive accounts of their lockdown experiences. Nevertheless, we are able to describe how some children negotiated restriction and confinement with impressive ingenuity and wit through film, animation, games and playful family interactions.

As children’s wellbeing and agency were key drivers in the research design, particular attention was given to ethical issues, including seeking voluntary informed consent from parents/carers and providing a specially designed information and consent form for children. The study received ethical approval from UCL Institute of Education, in line with the BERA Ethical Guidelines (British Educational Research Association Citation2018) and the NCRM ethical guidelines for working with visual data (Wiles et al. Citation2008). We were careful to ensure that we had permission from carers/children visible in the texts to be able to use their media artefacts for research and archiving purposes, and that both parties knew their rights in terms of levels of anonymity and public access. Contributors, particularly those who uploaded short films, were encouraged to take out a public copyright license (via Creative Commons) allowing others to share their work, whilst the creators’ themselves retained copyright. The Play Observatory’s ethical procedures were under continual review as new dissemination challenges emerged throughout the life-course of the project.

Film-making and transludic practices

The range of disciplinary expertise at our disposal within the research team, and demonstrable within our child participants, enabled the development of a framework of understanding we describe as transludic. We draw on Huizinga’s founding thoughts in ‘Homo Ludens’ in his cultural thesis on play (Citation1947) and Burn’s more recent work on video game-play and education in his chapter ‘Liber Ludens’ (Citation2016) in our elaboration of what the term means for digital making practices. Trans addresses the use of multiple meaning-making modes across time and space, including the idea of crossing and reconfiguring established boundaries and thresholds (Potter Citation2012), in a ceaseless process of re-making (Potter and Cowan Citation2020). Ludic attends to the pleasures of improvisation, self-directed challenge and open-ended play within the specific rules and conventions of filming and editing. An assemblage of transludic practices takes account of the unusual formation of pandemic time, space and social relations experienced by many families as they negotiated and adjusted to new domestic arrangements through play and film production.

The subject of play as a social and cultural phenomenon has been subject to much theorising and taxonomisation (Caillois Citation2001; Sutton-Smith Citation2009) since Dutch theorist Huizinga’s Citation1947 thesis on the cultural function of play in society. This article revisits his seminal work ‘Homo Ludens’, as observations within its contours seem to align with the possible role of film-making as a means of powerful learning for young people. Huizinga takes account of the social and cultural importance of play and parallels are made below between the repetitious and dynamic practices of play, its internal structures, and the similar qualities of film production practice as a bounded text-making experience:

Play begins, and then at a certain moment it is ‘over’. It plays itself to an end. While it is in progress all is movement, change, alternation, succession, association, separation. But immediately connected with its limitation as to time there is a further curious feature of play: it at once assumes fixed form as a cultural phenomenon. Once played, it endures as a new-found creation of the mind, a treasure to be retained by the memory. It is transmitted, it becomes tradition. It can be repeated at any time, whether it be ‘child’s play’ or a game of chess, or at fixed intervals like a mystery. In this faculty of repetition lies one of the most essential qualities of play. It holds good not only of play as a whole but also of its inner structure. In nearly all the higher forms of play the elements of repetition and alternation (as in the refrain), are like the warp and woof of a fabric. (Huizinga Citation1947, 9–10)

Our textual analysis offers glimpses of aptitudes, dispositions and particular conditions that point to a more ambitious and inclusive vision of literacy (Potter Citation2012) that endorses the dramatic sensibility and skills of oracy and performance (Burn Citation2009), as complementary to the norms of print literacy. We see evidence of sustained crafting of raw resources at hand (objects, images, text, sound and music) unfolding with a playful disposition and an appreciation of the affordances of local and domestic spaces. This supports calls for an education system founded on multimodal literacies, where contemporary texts are understood as combining multiple modes of expression and communication (Bezemer and Kress Citation2016; Carey and Kress Citation2003). It further supports the continued advocacy for media education which enables children to access these codes and conventions in familiar and popular cultural contexts (Buckingham Citation2019).

The authors explore our junior film-makers’ work in terms of pleasurable and playful moments of learning during lockdown, using a frame inspired by some of the features of play highlighted by Cowan (Citation2020) and constructs related to creative media production (Cannon Citation2018). Cowan acknowledges, as we do here in this piece, that the typology she presents in the ‘Panorama of Play’ report (2020, 6) is by no means exhaustive or essentialising, but encompasses amongst other qualities, play’s diversity of form and the intrinsic motivation of ‘players’. Cannon’s primary school film-making studies (Citation2018, 222) note these features too, as well as the iterative dimension (drawing on Burn Citation2009 and Potter Citation2012), where repetition and review necessarily accompany making processes, and often, the design of the texts themselves. As seen in the data, there are recurring motifs and ‘refrains’ in different genres that children reproduce from their knowledge of popular culture. Bearing these concepts in mind, we work towards outlining an assemblage of transludic practices, to re-imagine literacy in relevant, contingent and ultimately child-inspired ways.

Case Study 1: Louis – ‘It’s just things happening over time’

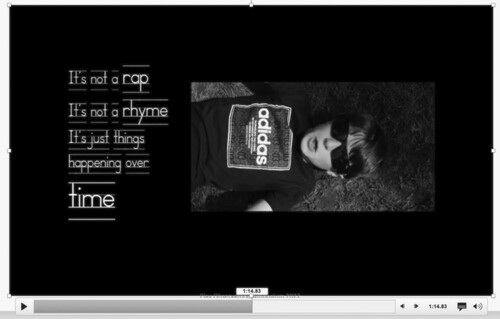

‘Covid Gone’ (Davis and Davis Citation2020) is a short film submitted to the Play Observatory survey (). It runs for a little over 2 min and takes the form of a YouTube style ‘lyric video’ in which the words to a rap appear written on the screen over the performance. The work was completed at home during the first lockdown in the summer of 2020, in a collaboration between a 10 year old boy and his father, Louis and Jonathan respectively. The film has a dual set of play practices embedded within it. Firstly, it is a record of play and play spaces in lockdown. Secondly, its creation, the act of making the film itself is a form of intergenerational play which, as Jonathan noted in a post-production interview helped to ‘keep everything positive’.

Figure 1. Things happening over time. Still from Covid Gone. Play Observatory PL56C1/S001/v1 © Louis and Jonathan Davis (reproduced with permission).

The remarkable sophistication in conception and completion of the piece belies the fact that this was the first attempt at video production by either of them. It represents a powerful message, illuminating deep and complex emotions about the pandemic, framed by exceptional writing and editing. Analysing the images and edits alongside the transcript of both the interview and the rap reveals a complex network of relations between people, spaces and the material conditions of lockdown which speak to theories of literacy, the digital and sociomateriality (Burnett and Merchant Citation2020). It also, arguably, has much to say about the distinctiveness of moving image production as a site of meaning-making for children and young people and lends considerable weight to arguments made elsewhere about introducing such practices into the school curriculum (see for example: Burn Citation2009; Cannon Citation2018; Buckingham Citation2019).

Beginning with the imagery in the writing itself, we can see the interplay of the interior emotion and space of the home, and the immediate local area in which amenities were closed, including school, for substantial periods of time. These are words which are written on the screen as they are spoken and illuminated with sharp editing and suitably dramatic music.

Two sets of repeated phrases run through the rap. The first of these is the couplet of ‘Worse than Terminator / Corona the new Exterminator’ and the second is ‘It’s not a rap / It’s not a rhyme/ It’s just things happening over time’. Explicit reference to naming the havoc wreaked at that point by the virus, by reference to popular culture, is in the first couplet, and the attempt to get to grips with the production and purpose of the piece is encoded in the second.

During the interview, Jonathan identified his son as the main author and performer and himself as the editor. The division of labour is important here, as the concepts originate with Louis and the shaping possibilities of the editing are under the control of Jonathan. But there is no doubt about the ways in which they combine to produce meaning and keep each other going through the process. This quotation from Jonathan in the interview illustrates the moment at which the project, which is proving to be very hard work, produces some extraordinary lyrics:

there was a moment wasn’t there when you said, ‘I can’t do this anymore Dad, I can’t do it anymore’. And I said, ‘Lou, Lou, what you’ve done is brilliant, absolutely brilliant, don’t say you can’t do it, you’re writing amazing stuff here’. And then you suddenly said, ‘No, no, no, Dad, you don’t understand, it’s not a rap, it’s not a rhyme, it’s just things happening over time’ … And it was like – Louis, Louis. Oh my God. Like write it down, because that’s a lovely moment.

Figure 2. Locked school gates. Still from Covid Gone Play Observatory PL56C1/S001/v1. © Louis and Jonathan Davis (reproduced with permission).

Spaces were disrupted and different. All around the immediate environment there was evidence of changing relations between people, and with space and time. In the post project interview, Jonathan alludes to the contribution of the film towards keeping ‘everything positive’ even though, within the words and images used, there is real affective force which displays serious fears and worries. The word ‘weird’, for example, recurs throughout the rap and the shots move through a sequence of colour changes and other video effects to underline the strangeness of the time. The confusion of emotions felt by Louis is present in the contradictory emotions of lines like: ‘My mind is exploding / Though the plants keep growing’ and ‘I’m not mad / At least I’m glad’. This sequence finds a counterweight in a series of stills which show family members, his brother, mum and dad in their ‘homely home’ and end in a sequence in which Louis acknowledges that it is ‘not all about Me Me Me’ and shows a clip of him clapping for the NHS, during one of the national celebrations of health workers.

The experience of lockdown itself pulled people into a particular kind of relation with one another which disrupted the usual habits and routines. Moving image production, a medium with a set of organisational principles which depends on the temporal relation of shot to shot (Bordwell et al. Citation2019), has much to offer a complex and direct representation of such a powerful human experience, of ‘things happening over time’. It allows Louis to be seen and it enables him to curate himself into the experience and position himself in relation to the pandemic and the attendant lockdown. There is no other form of cultural production which merges modes of meaning-making in this way, nor which permits the affective response to a crisis to pull together space and time. With the time facilitated by lockdown, access to support, and the willingness to learn together, Louis and Jonathan have produced a text which will communicate the experience of lockdown into the future in the Play Observatory archive. One lesson to learn from this powerful submission echoes the findings in other research and writing (Burn Citation2009; Potter and McDougall Citation2017; Cannon, Potter, and Burn Citation2018; Cannon Citation2018) that moving image production should have the space and time allocation in the curriculum, alongside the other forms of literacy available as an expressive resource for children and young people.

Case Study 2: Prisha – ‘The light wasn’t coming in me’

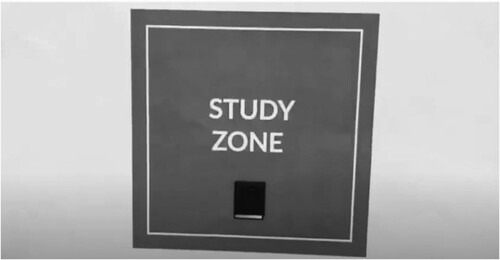

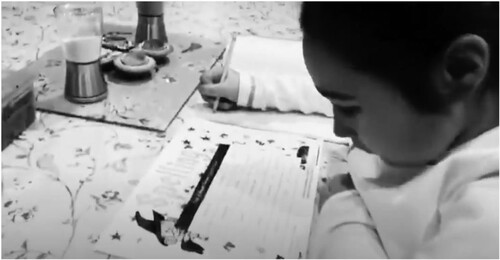

Ten year old Prisha came to us via the HomeCool Kids magazine (henceforth HCK) which was a lockdown initiative based in the Midlands where a group of primary-aged children produced an online magazine for their peers. The magazine had high production values and the children were interviewed about their work by Play Observatory researchers, becoming important contributors to both the project blog and the pandemic play collection. Prisha was part of the HCK production team and she volunteered to participate in a film-making workshop that ran alongside the processes of data collection. There was a range of skills in evidence among our young participant film-makers: some produced polished and edited fictional short films, whereas Prisha, supported by her older sister, chose to represent her experience of lockdown in a sequence of silent clips showing us various of her daily routines. The film, lasting 2 min and 25 s, depicted a house divided into different zones with signs on the doors to indicate how time was being spent in that particular area. Beyond the examples shown below, there were zones for Yoga, Reading, Gaming and Creativity ().

Figure 3. Still from All By Myself Exercise Area. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1. © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

Figure 4. Still from All By Myself Prisha exercising. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1. © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

Figure 5. Still from All By Myself Study Zone. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1. © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

Figure 6. Still from All By Myself Prisha studying. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1. © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

Figure 7. Still from All By Myself Meditation Zone. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1. © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

Figure 8. Still from All By Myself Prisha meditating. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1. © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

The ways in which the house was carved up with assigned activities may appear familiar to some readers during the challenging months of lockdown, and perhaps signals that an important sense of control was being exerted, if fleetingly, over her environment. For most of the movie, the camera follows Prisha around the house and frames her alone and busy, in doing-mode. Control is disrupted however, towards the end of the film when there is a shift in tone: Prisha is looking at a class photo on the floor of her bedroom, in a posture that suggests sadness and resignation, underwritten with a sense of nostalgia (). She reflects on the friends she is missing and her sense of isolation, and there is no signpost for these emotions, as if these feelings were all-pervasive throughout time and space, cutting through the busy-doing-ness.

Figure 9. Still from All By Myself Prisha reflecting on class photo. Play Observatory PL194C1/S001/v1 © Prisha and Shaanti Kular (reproduced with permission).

The film is a touching portrayal of a ten year old making sense of her pandemic experience through film. As an image-time-space based medium, film allows for the slow exercise of creative control over our environment in expressive and rhythmic representations. One of the aims of The Play Observatory project was to archive the pandemic play experiences of children, and Prisha’s film delivers in this respect by enabling her to structure her story around doing and being. As she thinks back on her experience and engages in re-configuring the spatial and the temporal to create an effective and affective visual narrative, we are encouraged as viewers to watch her while she does, and be with her while she feels the absence of her classmates. Prisha’s film is an achievement on many levels, and if one of literacy’s milestones towards progress is the ability to wield language in ways that affect readers/an audience successfully, then it is indeed puzzling why moving image literacy is denied the legitimacy that is accorded the printed word.

Louis’ film was suggestive of a changed and generative relationship with his familial surroundings, and Prisha also seems to see the mundane with new eyes. Film is a medium that can facilitate that shift by re-framing the quotidian, and making the familiar strange in pleasing and surprising ways. This section ends with a comment made by Prisha to delegates at the online Play Observatory Research Symposium in January 2022. The young film-making workshop participants were invited to introduce their films at the screening of their movies during the Symposium. Prisha, now eleven, as unphased and confident as she had proved to be throughout, delighted in showing her film All on my Own - Getting to light at the end of the tunnel to the assembled, and when asked to talk about how the film came about she explained that ‘the light wasn’t coming in me’. There is something both poignant and liberating about how the making of the film seemed to have effected some kind of artistic release for Prisha. For her, the lockdown was a difficult passage through a dark tunnel, impermeable to light, enclosed on either side, and the only way was through. It is as if film-making for Prisha, at this particular moment at this particular time, was an energetic activity in the widest sense. A certain opaque stasis had shifted through processes of creative production that allowed the passage of light and clarity of focus. There is of course a scientific relationship between light and the operations of film, but what lands with more resonance about her choice of words is the idea of making something that radiated positively out of chaotic conditions, and that this was achieved by noticing, thinking about, and playing with light.

Case Study 3: Levi - Bumblebee versus Sinsestro

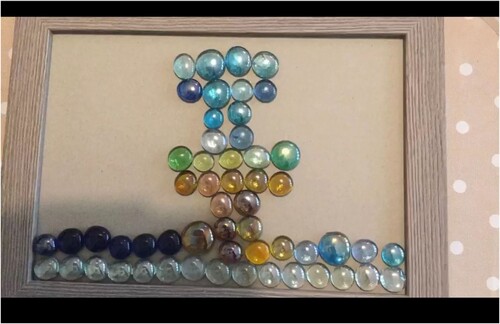

Bumblebee versus Sinsestro is a survey contribution created in July 2020, involving text and a media file of a short, stop-motion animation, uploaded by a nine year old boy (the child of one of the Play Observatory team) who we will call Levi. Levi self-describes as having dyslexia and dyscalculia, conditions that negatively impact on traditional literacy norms such as reading and writing, and understandings based on numbers. In the text contributed alongside the film, Levi describes his play:

My mum has some loose parts play stuff in the house. I’ve used it in the past to make pictures but this time I used it to make the scenes for some animation called Bumblebee versus Sinestro.

I had four picture frames and lots of glass beads, metal things, wooden rods, polystyrene pieces. Once I had built the scenes in the frames I used my Lego mini figures. I recorded my animation on my iPad with a tripod and I used the Lego Animator app. My mum bought me the tripod but I did the animation on my own.

(We would like to acknowledge at this point that Bumblebee, Sinestro and all the other names of characters and places mentioned above, feature in the original DC Universe comic series published by DC Comics, a subsidiary of Warner Bros. Discovery. Inc.)

Opening credit:

Scene 1: Exterior shot: Area around Arkham Asylum

Bumblebee is trying to capture Sinestro

They fly through the air and Bumblebee fires a yellow laser from his ring

Sinestro is blasted through the wall of Arkham Asylum

Scene 2: Interior shot: Arkham Asylum

Joker enters and tries to climb to Cheetah suspended from the ceiling in a cage

Beastboy and Cyborg arrive and try to stop Joker

Beastboy turns into a bird and flies into Joker, knocking him over

Cyborg’s jetpack malfunctions and he slams into Cheetah’s cage, accidentally releasing her. He then hits the wall, causing an avalanche of rocks, smoke and dust

In the confusion, Cheetah gets out of her cage

A rope is lowered from off-screen (by a character we do not see, but who Levi states is Catwoman) and Cheetah escapes

Joker escapes out of the door

Scene 3: Exterior shot: Teen Titans Tower

Interior shot: Bumblebee arrives to brief the Teen Titans about Cheetah’s escape

Scene 4: Exterior shot: Legion of Doom HG with swamps

Interior shot: Sinestro, Cheetah and Joker have return, reunited with Lex Luthor, Catwoman and Mr Freeze they make plans to cause more chaos.

Closing credits

The look and sensory presence of the loose parts play materials are utilised with precision and narrative awareness. Drawing on his cultural capital, Levi assembles LEGO™ minifigure DC Universe (DCU) characters as his cast. Across the three acts of the film, knowledge of the DCU informs the ‘good guys’ versus villains grouping of characters, their use of specific powers, and their interactions in the locations in the plot (Arkham Asylum, Titans Tower and the Legion of Doom headquarters). With improvised dexterity, he draws an additional character (a yellow laser) and a prop (the bird) to move the narrative along. There is pleasure and metaphorical skill associated with the successful orchestration of symbolic elements to create meaning, especially as this relates to a young man for whom schooled literacy practices may prove challenging. For example, when Cyborg loses control of his jetpack and hits a wall, brown coloured glass beads become tumbling rocks and white polystyrene pieces depict the smoke and dust from the impact (). There are few quick wins when animating, and constructing this climactic moment in the story will have required sustained self-direction, artistry and focus over a considerable length of time.

Figure 10. Still from Bumblebee versus Sinestro. Debris, smoke and dust from Cyborg’s crash. Play Observatory PL34C1/S002/v1 © Play Observatory DOI: 10.15131/shef.data.21198142.

Making appropriate aesthetic choices is a strong element of creative media practice. The LEGO™ Animator app has soundtrack options, and Levi chose one with an appropriately fast-pace, in an action-adventure style to suit story and momentum. The use of an establishing exterior shot (), followed by interior shots, helps the story to progress and there is further evidence of implicit film know-how in the rescue of Cheetah. Often off-screen action is as important as on-screen, as it raises questions and creates tension: the lowering and raising of the LEGO™ rope off-screen makes this tacit knowledge explicit. ( and ). The film is the result of a complex assemblage of cultural knowledge, film literacy and imaginative symbolic play that Levi operationalises using the material and audiovisual affordances of animation, and his digital wit.

Figure 11. Still from Bumblebee versus Sinestro. Establishing exterior shot of Titans Tower. Play Observatory PL34C1/S002/v1 © Play Observatory DOI: 10.15131/shef.data.21198142.

Figure 12. Still from Bumblebee versus Sinestro. Cheetah escapes via a rope. Play Observatory PL34C1/S002/v1 © Play Observatory DOI: 10.15131/shef.data.21198142.

Figure 13. Still from Bumblebee versus Sinestro. Joker flying out of the Legion of Doom HQ. Play Observatory PL34C1/S002/v1 © Play Observatory DOI: 10.15131/shef.data.21198142.

Animation works through a process known as ‘persistence of vision’, where the eye is tricked into perceiving the movement of a series of still images. The same phrase can be applied to Levi’s persistence in the accomplishment of his vision: it was a sustained physical and mental effort with which he appeared to be satisfied, not least because his work was shared with relations. The contribution was accompanied by this affirmatory text:

I enjoyed doing this. It took a lot of time but I was very happy with my film. My mum sent it to my grandma and my uncles, aunts and cousins.

Case study 4: Ghina – ‘Kid’s understanding of Corona Virus’: A lockdown YouTube video

Several contributions to the Play Observatory survey mentioned children’s use of social media and video-streaming sites as significant activities throughout the pandemic, both in terms of watching content and creating their own (see Cowan et al. Citation2021). In one submission from Melbourne, Australia, a parent described her eight year old daughter ‘making crafts and creating videos’ for entertainment during lockdown and shared a list of links to her daughter’s YouTube channel (Play Observatory PL145A1/S001) called GhiSmart (Citation2020). The videos feature the child, who we will call Ghina, addressing the viewer directly, filmed in one take. They include a variety of forms, such as ‘day-in-the-life’ style vlogs where she talks through activities such as riding her bike or visiting the beach, tutorials for crafts such as how to make a figure out of clay, and popular YouTube trends such as ‘unboxing’ of toys.

Several of the videos make reference to the pandemic as a feature of day-to-day life. For instance, in a video showing Ghina riding on a train, she demonstrates putting on her mask. In another, entitled ‘News Reporter’, she mimics a newsreader, talking about changes to home schooling whilst sitting at a desk with sheets of paper in front of her as a ‘Breaking News’ animation spins in the lower portion of the screen.

Focusing on one of these videos, ‘Kid’s understanding of Corona Virus’ was uploaded in the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic and features Ghina talking about the virus (see transcript). In the recording, lasting 2 min and 25 s, she addresses the viewer directly, positioned close to the camera and looking directly into the lens. She is dressed in a headscarf, worn in all her videos, sitting in a kitchen presumably whilst at home during lockdown.

Hi guys. Welcome back to my channel, and today I’m gonna talk about coronavirus because there’s a lot of coronavirus coming in China so you have to be careful with this, you know. And don’t forget to wash your hands (puts hands together) with soap or something else that can make all the coronavirus fail and not stay on your hands. And don’t forget to do that all the time. And don’t forget to take a bath! And do you know, coronavirus is making you really sick or die so you have to be really careful about this. So if you get coronavirus you have to really really really go fast to the car and go to the hospital because coronavirus can make you die. The thing that I just say, so if you get coronavirus you have to go to the hospital. And one more thing, if you cough you have to cover it with your elbows (points to elbow) or get a tissue and then cover it up (gestures holding hands over her mouth/nose). And you have to use something … no no no you actually have to drink a lot because if you get coronavirus and if your mouth is dry (points to mouth) you’re actually maybe you’re gonna die or something. And I don’t know about the rest so bye-bye (waves). See you next time in [name of channel]. Don’t forget to subscribe and click the thumbs up button. Bye! (waves). See you later!

(Transcript of ‘Kid’s understanding of Corona Virus’. © Play Observatory PL145A1/S001. GhiSmart YouTube channel. See https://youtu.be/y0pLriM_zvk)

The points she mentions reflect key public safety messages that were being widely shared particularly in the early stages of the pandemic, outlining hygiene measures to limit the spread of the virus. Ghina’s direct instructional style emulates the media’s emphasis at the time when her video was made. As she shares advice about hand-washing and the need to cover your mouth and nose when coughing, she gestures to further accentuate and demonstrate the importance of these actions (). The video reveals her understanding of healthy practices and the unfolding international crisis, for instance mentioning increasing cases in China, and her awareness of the possibility the virus could lead to illness or death. It also reveals her uncertainties about what else might be done to prevent it, such as having to take a bath or drink a lot.

Figure 14. Ghina demonstrating covering mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing. © Play Observatory PL145A1/S001.

Whilst the video draws on many conventions of news media and instructional videos, it also shows awareness of genres and conventions of YouTube. She begins the video with a casual opening, ‘Hi guys, welcome back to my channel’, and ends it with a conversational, ‘See you next time on [name of channel]’ and ‘See you later!’. She also reminds the viewer, ‘Don’t forget to subscribe and click the thumbs up button’, referring to the practice of adding ‘likes’ to videos and subscribing to the creator’s content, a feature of many videos uploaded by popular YouTubers.

The importance of YouTube in children’s lives, and its influence on playful practices, has been identified in earlier research undertaken in school playgrounds (Potter and Cowan Citation2020). In this example from Ghina, YouTube is both a medium for playful creation, a way of sharing these creations with others remotely whilst social contact was restricted, and a genre influencing the design and style of the video itself. Whilst on first viewing this video may seem simple (for instance, in terms of its lack of editing), it shows not only Ghina’s understanding of the pandemic but also her knowledge of a range of media texts, including news reports, instructional videos and content made by popular YouTubers. She combines these into her own timely multimodal text that offers insights into both her understanding and lived experience of Covid-19, and of contemporary media.

Ghina demonstrates confidence with the YouTube video format, perhaps developed through her own watching of videos and her experience of having made a number of videos for her channel. She seems to be improvising an unscripted piece to camera, as many experienced vloggers do, confidently embodying or ‘playing’ a YouTuber persona. Despite the serious subject matter, she makes the content playfully engaging, seeming to address an audience of peers. This is emphasised in the naming of the video as ‘Kid’s understanding of Corona Virus’, emphasising that this is a young person’s distinctive view of the unfolding pandemic.

Children’s videos produced for, and in response to, social media and video-streaming platforms such as YouTube constitute important cultural texts in the lives of children. The extent to which they are recognised as such, let alone permitted or encouraged within education, requires careful reconsideration if we are to develop meaningful educational practices supportive of children’s multimodal literacies.

Discussion

The pandemic was a global event that foregrounded the extraordinary resourcefulness and capacity for humans to adapt to shifting circumstances, and children were and continue to be playful and adaptable negotiators of such events. We believe that the case studies reveal children’s resilience and creativity in the face of adversity in ways that showcase hitherto unseen talents and orientations that complicate debates on the nature of literacy. These findings echo the work of Nordström, Kumpulainen, and Rajala (Citation2021) who speak of the ‘unfolding joy’ inherent in creative experiences with multiliteracies in the Early Years classroom, and the ‘affective intensities’ that ‘augment our power of acting’. Our analyses of multimodal contributions from the public sphere thus ground relevant and bold visions for learning in the primary and early secondary years.

Case Study 1 addressed the ways in which planning, shooting and editing film delivered on positive intergenerational play and performance in the spaces of the home, specifically drawing on rap culture and the lyric video which were found to be inspiring for Louis. The complex choreography of modes, music and meaning-making devices was the result of a rich collaboration between father and son, both learning in improvised ways, and both learning from each other. We saw similar displays of family support in Case Study 2 where Prisha was helped by her sister to make a film that represented how time, space and activity were carved up in the home and, more poignantly, how she missed her friends. For Levi, in Case Study 3, the effort expended on storytelling with moving image and sound offered satisfaction and a sense of empowerment. Finally, Ghina, emulating and performing the tropes of vloggers’ pieces to camera, made videos and shared pandemic advice through her YouTube channel, exhibiting an ease and independence of spirit, to inform and interact with her peers and audiences beyond.

Conclusion

We acknowledge that not all children had access to technology during lockdown, nor did many enjoy such supportive home environments, which adds weight to our argument that school is the space in which all children should be offered opportunities to use their improvisatory film and media skills, pursue their cultural interests and use whatever materials are at hand, to develop multimodal expression. All these children’s achievements were intrinsically motivated, and emerged from an entangled mess of historical circumstance. The composing and shaping of expressive digital and analogue resources entailed ‘joyful intra-actions’ with multiple ‘agentive entities’ (Nordström, Kumpulainen, and Rajala Citation2021), thus creating a clearing, out of which texts could be disentangled, shaped, shared and remembered by others.

From the Play Observatory case studies, we have been able to identify an assemblage of transludic practices with digital media that could inform change to what counts as legitimate literacy texts, practices and tools, in ways that both serve children’s interests and celebrate their capabilities. We suggest that urgent provision be made in schools for creative engagements with:

multiple meaning-making modes, materials and digital tools

self-directed manipulation of time and space, in time and space

iterative and inclusive creative media arts practises incorporating popular cultural knowledge

free experimentation and improvisation with the expressive resources at hand

intra-active and social making and sharing experiences among local networks

The impulse to make films unearthed by the Play Observatory provides a template for more playful ways to make sense of the world, not only in response to a global emergency, but also in terms of everyday social and cultural participation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the whole Play Observatory team who were integral to the design, implementation and success of the project: Dr. Catherine Bannister, School of Education, University of Sheffield; Dr. Julia Bishop, School of Education, University of Sheffield; and Dr. Valerio Signorelli, CASA, Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, UCL, London.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Gunther Kress. 2016. Multimodality, Learning and Communication: A Social Semiotic Frame. New York: Routledge.

- Bordwell, David, Kristin Thompson, and Jeff Smith. 2019. Film Art: An Introduction. 12th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. BERA Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. London: BERA.

- Buckingham, David. 2019. The Media Education Manifesto. Cambridge: Polity.

- Burn, Andrew. 2009. Making New Media: Creative Production and Digital Literacies. New York: Peter Lang.

- Burn, Andrew. 2016. “Liber Ludens: Games, Play and Learning.” In The Sage Handbook of E-Learning Research, edited by Caroline Haythornthwaite, Richard Andrews, Jude Fransman, and Eric Meyers M, 127–51. London: Sage Publication Ltd.

- Burn, Andrew, and James Durran. 2006. “Digital Anatomies: Analysis as Production in Media Education.” In In Digital Generations: Children, Young People, and the New Media, edited by David Buckingham, and Rebekah Willett, 273–93. London: Routledge.

- Burnett, Cathy, and Guy Merchant. 2020. Undoing the Digital: Sociomaterialism and Literacy Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Caillois, Roger. 2001. Man, Play and Games. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Cannon, Michelle. 2018. Digital Media in Education: Teaching, Learning and Literacy Practices with Young Learners. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cannon, Michelle, John Potter, and Andrew Burn. 2018. “Dynamic, Playful and Productive Literacies.” Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education 25 (2): 183–99. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2018.1452146.

- Carey, Jewitt, and Gunter Kress. 2003. Multimodal Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

- Cowan, Kate. 2020. A Panorama of Play - A Literature Review. London.: Digital Futures Commission.

- Cowan, Kate, John Potter, Yinka Olusoga, Catherine Bannister, Julia Bishop, Michelle Cannon, and Valerio Signorelli. 2021. “Children’s Digital Play During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from the Play Observatory.” Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society 17 (3): 8–17. doi:10.20368/1971-8829/1135590.

- Davis, Louis, and Jonathan Davis. 2020. Covid Gone. Play Observatory PL56C1/S001/v1. © Louis and Jonathan Davis (reproduced with permission). Accessed 23 September 2022. https://mediacentral.ucl.ac.uk/Player/JBJA12jf.

- Dowsett, Elizabeth, and Arie Kaplan. 2018. DC Superheroes Visual Dictionary. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- GhiSmart Channel. 2020. “Kid’s (sic) Understanding of Corona Virus.” Accessed 26 September 2022. https://youtu.be/y0pLriM_zvk.

- Harmey, Sinead, and Gemma Moss. 2021. “Learning Disruption or Learning Loss: Using Evidence from Unplanned Closures to Inform Returning to School After COVID-19.” Educational Review, 1–20. doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.1966389.

- Houser, Natalie, Lindsay Roach, Michelle Stone, Joan Turner, and Sara Kirk. 2016. “Let the Children Play: Scoping Review on the Implementation and Use of Loose Parts for Promoting Physical Activity Participation.” AIMS Public Health 3 (4): 781–99. doi:10.3934/publichealth.2016.4.781.

- Huizinga, Johan. 1947. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Nicholson, Simon. 1971. “How Not to Cheat Children, the Theory of Loose Parts.” Landscape Architecture 62 (1): 30–34.

- Nordström, Alexandra, Kristiina Kumpulainen, and Antti Rajala. 2021. “Unfolding Joy in Young Children’s Literacy Practices in a Finnish Early Years Classroom.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. doi: 10.1177/14687984211038662.

- Observatory, Play. 2021. The Play Observatory Project Website. Accessed 21 September 2022. www.play-observatory.com.

- Potter, John. 2012. Digital Media and Learner Identity: The New Curatorship. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Potter, John, and Kate Cowan. 2020. “Playground as Meaning-Making Space: Multimodal Making and Re-Making of Meaning in the (Virtual) Playground.” Global Studies of Childhood 10 (3): 248–63. doi:10.1177/2043610620941527.

- Potter, John, and Julian McDougall. 2017. Digital Media, Culture and Education: Theorising Third Space Literacies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Street, Brian. 2003. “What’s ‘New’ in New Literacy Studies? Critical Approaches to Literacy in Theory and Practice.” Current Issues in Comparative Education 5 (2): 77–91.

- Sutton-Smith, Brian. 2009. The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wiles, Rose, Jon Prosser, Anna Bagnoli, Andrew Clark, Katherine Davies, Sally Holland, and Emma Renold. 2008. “Visual Ethics: Ethical Issues in Visual Research.” NCRM Working Paper. n/a. (Unpublished). Accessed 8 March 2023. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/421/

- Williamson, Ben. 2021. “Counting Learning Losses” in Code Acts in Education. 24 September 2021. Accessed 23 September 2022 from: https://codeactsineducation.wordpress.com/2021/09/24/counting-learning-losses/.