Abstract

Despite having been referenced in the literature for over a decade, the term “mixed pain” has never been formally defined. The strict binary classification of pain as being either purely neuropathic or nociceptive once left a good proportion of patients unclassified; even the recent adoption of “nociplastic pain” in the IASP Terminology leaves out patients who present clinically with a substantial overlap of nociceptive and neuropathic symptoms. For these patients, the term “mixed pain” is increasingly recognized and accepted by clinicians. Thus, an independent group of international multidisciplinary clinicians convened a series of informal discussions to consolidate knowledge and articulate all that is known (or, more accurately, thought to be known) and all that is not known about mixed pain. To inform the group’s discussions, a Medline search for the Medical Subject Heading “mixed pain” was performed via PubMed. The search strategy encompassed clinical trial articles and reviews from January 1990 to the present. Clinically relevant articles were selected and reviewed. This paper summarizes the group’s consensus on several key aspects of the mixed pain concept, to serve as a foundation for future attempts at generating a mechanistic and/or clinical definition of mixed pain. A definition would have important implications for the development of recommendations or guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of mixed pain.

Introduction

Clinical discussions on “mixed pain” have been ongoing for over a decade yet it remains a poorly defined condition, representing an unmet need in clinical practice. Uniform pain terminology to communicate information about our patients and their pain is important to distinguish one case of chronic pain from another and, therefore, defining basic pain terms and classifying pain syndromes have consistently been the focus of several committees and task forces of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). However, even after the most recent definitions of the IASP’s Task Force on Taxonomy, pain terminology still lacks precision.

The discrete pathophysiological classification of pain as being either purely neuropathic or purely nociceptive has often been challenged as both inaccurate and over-simplisticCitation1–3. This criticism led to changes in pain taxonomy and the development of more universally accepted definitions of types of pain though the term “mixed pain” was (and continues to be) neglected.

The IASP’s 1994 definition of neuropathic pain as “pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the nervous system” generated heated debate, specifically surrounding the term “dysfunction” which was generally viewed to be too broad and imprecise. The IASP Special Interest Group on Neuropathic Pain (NeuPSIG) subsequently endorsed a new definition of neuropathic pain in 2008, as “pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system”Citation4, which was later adopted by the IASP council with an annotation that “neuropathic pain is a clinical description (and not a diagnosis), which requires a demonstrable lesion or a disease that satisfies established neurological diagnostic criteria”Citation5. This much more robust definition has remained unchallenged ever since.

In turn, nociceptive pain – thought to be by far the most common human pain type – is defined by the IASP as “pain that arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to activation of nociceptors” (pain associated with active inflammation falls under this category). The note accompanying this term in the IASP Terminology states that “this term is designed to contrast with neuropathic pain”Citation5.

This original taxonomy was problematic, positing a framework of pain neurobiology in which there is either pain experienced with a normally functioning somatosensory nervous system (i.e. nociceptive pain) or pain experienced when the somatosensory nervous system exhibits any kind of abnormal function (i.e. neuropathic pain). Put another way, these definitions positioned nociceptive pain as the only alternative to neuropathic pain, and vice versa. This strict binary classification of pain left a sizeable proportion of patients unclassified, specifically: (1) patients who present clinically with a substantial overlap of nociceptive and neuropathic symptoms; and (2) patients who do not exhibit signs or symptoms of any actual or threatened tissue damage, nor evidence of a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system.

For the latter patient group, which includes patients with fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome type 1, or “functional” visceral pain disorders (such as irritable bowel syndrome and bladder pain syndrome), a 2016 topical review by Kosek and colleagues proposed utilizing a third mechanistic descriptor to describe the chronic pain stateCitation2. The authors’ candidate adjectives for this third descriptor included (1) “nociplastic”, to reflect changes in function of nociceptive pathways; (2) “algopathic”, to describe a pathological perception or sensation of pain not generated by injury; and (3) “nocipathic”, to denote a pathological state of nociception. Reactions to the proposal within the medical pain community were largely positiveCitation6, though a few critics contended that a further mechanistic pain descriptor was not necessaryCitation7,Citation8. Nonetheless, in November 2017, the IASP Council adopted the proposal for a third mechanistic descriptor of painCitation6, electing to include the term “nociplastic pain” in the IASP TerminologyCitation5. The Task Force on Taxonomy defined nociplastic pain as “pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain”. Thus, if one were to count pain of psychological origin in this framework – a patient’s report of which should be accepted as pain, as highlighted in the note accompanying the IASP definition of painCitation5 – a clinician has at least four different classes of pain to consider.

For patients who present clinically with a substantial overlap of nociceptive and neuropathic symptoms in the same body area, the term “mixed pain” is increasingly recognized and accepted by pain clinicians, and the term is used in the scientific literature to describe such specific patient scenarios. Notably, however, mixed pain has never been formally defined – the term “mixed pain” does not appear in the IASP Taxonomy, and it is still missing in textbooks, educational programs, and guidelines of medical associations and health authorities. This lack of a formal definition – coupled with the vagueness and imprecision inherent in the term – has resulted in “mixed pain” being inadequately used in an extensive array of contexts, including as a description for, among others: pain due to a primary injury and its secondary effectsCitation9; pain that transitions from nociceptive pain to neuropathic painCitation9; pain that yields ambiguous scores on neuropathic pain scoring tools, such as painDETECTCitation10; pain experienced by a non-homogeneous group of study patientsCitation11; pain with combined elements of somatic, visceral and neuropathic painCitation12; pain generated from combined central and peripheral pain mechanisms post-strokeCitation13; or simply pain occurring at multiple sitesCitation14.

One might think that attempting a definition at this point in time is premature given the fact that the mechanisms by which mixed pain is generated are presently still unclear and, moreover, the elaboration and development of clinical criteria to identify patients with nociplastic pain has only just begunCitation15. Within the pain research field there are those who argue that there is no foundation for a definition of mixed pain, suggesting that the development of one would be a “pseudo-intellectual exercise”. However, given the increasing clinical evidence and patient need, it would be an over-simplification to oppose a concept while arguing that the reason the term “mixed pain” does not appear in the IASP Taxonomy or textbooks and guidelines most likely is due to lack of need. In our view, it is crucial to clarify and define a pain term which is increasingly used worldwide. Furthermore, it is only logical to take the first steps in the direction of an initial definition of “mixed pain”, as such a definition would have important implications:

It would promote a better understanding and awareness of mixed pain among healthcare professionals, which would improve identification and diagnosis of patients;

It would allow the categorization of some patients with chronic pain conditions currently classified as “pain of unknown origin”;

It would establish the basis for the development of new therapeutic strategies and agents which target potentially distinct mixed-pain mechanisms;

It would form the basis for the development of new mixed-pain screening and diagnostic tools for both research and clinical use; and

It would be the impetus for development of recommendations or guidelines for the management of mixed pain.

Granting that an attempt at a definition is controversial, what is entirely appropriate and, in fact, imperative at this stage is to consolidate current knowledge and articulate all that is known (or, more accurately, thought to be known) and all that is not known about mixed pain. This can serve as a first foundation for future attempts at generating a more widely accepted mechanistic and/or clinical definition of mixed pain.

Methods

On the initiative of the first author, an international group of pain clinicians from multiple specialities – pain medicine specialists, anaesthesiologists, neurologists, orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists and general internists from Brazil, Colombia, Germany, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Mexico, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand – participated in a series of informal discussions on mixed pain, carried out online and on the sidelines of three regional medical conferences in Asia and Latin America in 2017. The formation of the group resulted from personal contacts, was arbitrary, and was not endorsed by any scientific or medical society. However, members of the group are all highly experienced practicing pain clinicians who see patients with mixed pain on a regular basis; most are involved in pain research and are abreast of current developments, and are leaders of their respective national pain societies.

Members were asked to reflect on and respond to a set of questions on mixed pain developed by the first author, answers to which were then discussed and debated upon face to face by the larger groups. The discussions yielded a short, bulleted list of general statements representing the group’s consensus on several key aspects of the mixed pain concept. This paper elaborates on these discussion points.

To inform the group’s discussions, a Medline search for the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) “mixed pain” was performed via PubMed. The search strategy encompassed clinical trial articles and reviews from January 1990 to the present. Clinically relevant articles were selected and reviewed, with the pertinent highlights of these articles presented below.

Results

What is known (or thought to be known) about mixed pain

1. The literature on mixed pain goes back at least two decades

The concept of somatic pain conditions exhibiting a combination of nociceptive and neuropathic components has been reported in the literature for almost 20 years and recently with increasing frequencyCitation10,Citation16,Citation17. The term “mixed pain” – used in reference to a pathophysiological category of pain – was first employed by Grond and colleagues in 1999. Having conducted a survey of 593 cancer patients treated by a pain service, they reported that 181 patients had both nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain – these patients they categorized as having “mixed pain”Citation18.

Subsequently, in a paper arguing that understanding of a patient’s pathophysiological process, initiation of appropriate treatment and enhancement of patient outcomes can only be achieved with improvements in pain classification, Ross observed that “[current] classification schemes do not recognize that patients with pain often have mixed pain syndromes and do not fall neatly into these schemes”Citation3.

The discussion of mixed pain as a pathophysiological concept in literature truly emerged in 2004, when a German group extensively discussed “the mixed pain concept as a new rationale” in the German Medical Association’s official science journalCitation19, then presented it at a symposium organized by the German Pain Society, the German chapter of the IASP. A parallel publication by the same working group then linked the mixed pain concept explicitly to a specific pain condition, namely chronic sciaticaCitation20; here they offered the description of “mixed pain” in recognition of the different pain-generating mechanisms underlying typical sciatic pain, and discussed the challenges to providing effective treatment.

Two consecutive publications in 2005 expanded clinical understanding of the condition. The first focused on the pathophysiology of mixed pain, arguing that a mixture of nociceptive and neuropathic pain-generating mechanisms in certain patients with chronic pain challenges the notion of a strict demarcation between these mechanismsCitation1. The second publication focused on the implications of mixed pain pathophysiology on therapy, highlighting the necessity of a treatment approach that combines therapies targeting both nociceptive and neuropathic pain componentsCitation21.

Several years later, Freynhagen and Baron provided a comprehensive review of the mixed pain concept as linked to chronic back painCitation22, elaborating on key ideas in mixed-pain pathophysiology, diagnosis and management that were first outlined in their 2004 paper.

Interest in mixed pain as a clinical and research topic has risen exponentially in recent years. A search of “mixed pain” as a MeSH term on Medline yielded 563 publications spanning preclinical studies, clinical trials and systematic reviews in the decade since the term first emerged (i.e. 1999–2010); in contrast, the number of publications to emerge subsequently (i.e. 2011 to the present) was 1779. Besides studies in low back pain, recent publications have described mixed pain in different novel contexts.

2. Several chronic pain states are considered in the literature to be mixed pain

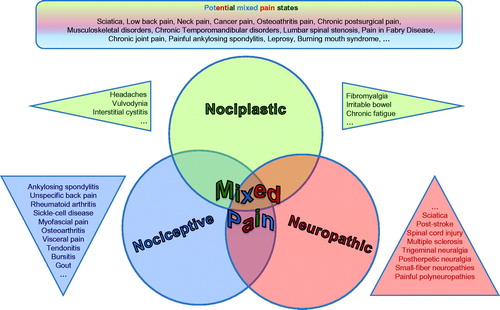

A number of commonly encountered pain states have been described in the literature as “mixed pain”. Notably, what these conditions share is a common characterization of manifesting clinically with a substantial overlap of the different known pain types in any way (nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic; ).

Figure 1. The three different types of pain defined by the IASP give rise to overlap which can be acknowledged as “mixed pain” (Freynhagen©). Conditions described as “mixed pain” in the literature share a common characterization of manifesting clinically with a substantial overlap of the different known pain types.

Cancer pain. It seems widely accepted that cancer pain is often of mixed aetiologyCitation23,Citation24. Results of a systematic review of 22 studies reporting on 13,683 patients with active cancer reporting pain, and in which a clinical assessment of pain had been made, showed that the prevalence of neuropathic pain ranged from a conservative estimate of 19.1% to a liberal estimate of 39.1%, when patients with mixed pain were includedCitation25.

Low back pain. Low back pain, ranked among the top 10 diseases and injuries in terms of highest number of disability-adjusted life years worldwideCitation26, is often classified as mixed pain, associated with both neuropathic and nociceptive pain componentsCitation17,Citation20,Citation22. A systematic review of low back pain trials highlighted that 20–55% of patients with chronic low back pain had a greater than 90% likelihood of having a neuropathic pain component, while in another 28% of patients, a neuropathic pain component was suspectedCitation17.

Osteoarthritis pain. Osteoarthritis pain, always the prototype of nociceptive pain, is now increasingly considered a result of the co-occurrence of nociceptive and neuropathic pain mechanisms at both local and central levelsCitation27. In a 2014 review, Thakur and colleagues made the case for recognizing patients with osteoarthritis having pain with neuropathic features as comprising a distinct subgroup, with a different osteoarthritic aetiology, and a sensitivity to pharmacological agents that contrasts with other patients with the conditionCitation28. The proportion of such patients is not inconsequential: in a study involving patients with knee osteoarthritis who were asked to describe the quality and severity of their pain, 34% used both neuropathic and nociceptive pain descriptors, suggesting “that [osteoarthritis] can be associated with a mixture of pain mechanisms”Citation29. Results of the most recent systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis – culling data from nine studies involving a total of more than 2000 patients – showed an overall prevalence of neuropathic pain components of 23%Citation30.

Postsurgical pain. Mixed pain is also hypothesized to be associated with postsurgical pain. A 2006 paper estimated that 10–50% of patients who underwent routine surgery developed acute postsurgical pain that eventually became chronicCitation31. While iatrogenic neuropathic pain is regarded as a major cause of chronic postsurgical pain, ongoing nociception is recognized as a contributing factor in certain patients. A more recent French multicentre prospective cohort study looked at neuropathic aspects of persistent postsurgical pain occurring within 6 months after nine types of elective surgical procedures. From 2397 patients, the cumulative risk of neuropathic postsurgical persistent pain was estimated at 20.6% for the whole cohort; the risk ranged from 3.2% for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy to 37.1% for breast cancer surgeryCitation32.

Pain in primary care versus the orthopaedic setting. A recently published Spanish cross-sectional study of 5024 patients in primary care and orthopaedic settings reported that pain of mixed pathophysiology was the most common pain condition (59.3%), followed by nociceptive and neuropathic pain (31.8% and 8.9%, respectively)Citation16. Mixed pain was more frequent in primary care settings (61.2%) than in orthopaedic settings (57.3%); it was found to be particularly associated with spine-related complaints (80% of cases), though it was also detected in other, non-spine-related conditions.

3. Mixed pain is phenotypically heterogeneous

In a survey of 1083 patients with axial low back pain, investigators identified five distinct subgroups of patients showing a characteristic “sensory profile”, or a typical constellation and combination of pain symptoms; notably, patients of some subgroups exhibited distinct neuropathic characteristics, while patients in other groups showed nociceptive featuresCitation33. Further, participants of a qualitative, focus-group study involving representative types of patients suffering from osteoarthritis described a wide variety of painful sensations which differed in terms of intensity (e.g. “pain as an electrical shock”), duration (from ongoing “background pain” to sharp, instantaneous pains brought on by “bad movement”), depth (muscle-deep vs bone-deep), and associated symptoms (most often anxiety related to the sensation of intense pain)Citation34. Finally, among patients who had undergone joint replacement and reporting persistent postsurgical pain, pain symptoms ranged from mild to “severe–extreme” (occurring in 15% of study patients post-total knee replacement), with the persistent pain most commonly described as “aching”, “tender”, and “tiring”Citation35.

The authors hypothesized that this complexity of presentations is rooted in the chronological presentation of nociceptive versus neuropathic versus nociplastic symptomatology: nociceptive, neuropathic and nociplastic pain components in any combination may occur simultaneously or concurrently in a patient with a mixed pain conditionCitation36, denoting, ostensibly, that these components are operating at the same time or during the same time course; or one pain component (and, presumably, one mechanism) may be more clinically predominant at a given time, driven or blocked by different molecular mechanisms leading to a decrease or increase in the excitability of spinal cord neuronsCitation37. Then again, it may well be that mixed pain is subserved by an entirely independent pathophysiological mechanism (or mechanisms), distinct from nociceptive, neuropathic or nociplastic mechanisms and, as yet, uncharacterized (see What is not known about mixed pain below).

4. The presence of mixed pain has negative implications for quality of life

An early study of 8000 patients with low back pain reported that 37% had predominantly neuropathic pain components and that these patients suffered longer and more severely, and were more susceptible to depression, panic/anxiety disorders and sleep disorders than patients in the rest of the study cohortCitation38. A prospective multicentre study of 1519 patients reported that neuropathic pain and mixed pain were associated with impaired physical and mental QoL, producing a substantial level of disability in these patients; mixed pain was specifically associated with lower physical and mental QoL than neuropathic pain aloneCitation39. A study of 80 patients with treated leprosy found that 12 of 14 patients reporting either neuropathic pain or mixed pain had high scores on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), indicative of possible depressionCitation40.

In accordance with the published literatureCitation16,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41, all members of the group generally perceived patients with mixed pain as having more comorbidities, such as depression, anxiety and sleep disorders, that collectively contribute to psychosocial problems, and as having more complex clinical presentations that negatively impact on response to treatment. It was also agreed that these patients are more difficult to treat.

What is not known about mixed pain

1. We do not know the mechanism(s) of mixed-pain generation

Whether mixed pain is the manifestation of neuropathic and nociceptive mechanisms operating simultaneously or concurrently, or the result of an entirely independent pathophysiological mechanism – distinct from nociceptive, nociplastic and neuropathic pain – is currently unknown. In other words, is mixed pain simply the addition of two or more components or does the mixture of different types of mechanisms result in the emergence of a true, qualitatively different clinical entity? And is mixed pain more frequent when pain occurs in large areas of the body (which might, however, be simply a probability issue, linking larger pain areas with higher odds of the presence of a concurrent pain mechanism)?

Assessing the results of their cross-sectional study of 5024 Spanish patients suffering from pain in primary care and orthopaedic settings, Ibor and colleagues proposed that “[the consideration of mixed pain as] an independent category in the pathophysiological classification of pain is justified”, given that patients with mixed pain “showed a greater clinical complexity” than patients with either nociceptive or neuropathic pain – these patients exhibited more comorbidities; were associated with more adverse psychosocial factors; responded less effectively to treatment; and experienced a lower health-related quality of lifeCitation16. However, they offered no clear evidence or hypothesis of a bona fide unique mechanism – distinct from neuropathic and nociceptive pain-generating mechanisms – underpinning mixed pain as an independent pain type.

Notably, an exhaustive review of the pertinent literature yielded no animal or human studies establishing that such a distinct, independent mechanism is operative in patients suffering from mixed pain. The most detailed characterization of chronic lumbar radicular pain – so far the prototypical mixed-pain state – describes it as the end-result of several neuropathic and nociceptive pain-generating mechanisms, including lesions of nociceptive sprouts within the degenerated lumbar disc; mechanical compression of the nerve root; and action of inflammatory mediations originating from the degenerative disc even without mechanical compressionCitation22.

2. We do not know how to screen for and diagnose mixed pain definitively

The updated grading system for neuropathic pain emphasized the importance of identifying pain associated with sensory abnormalities, in conjunction with performance of diagnostic tests, to confirm a lesion or disease of the somatosensory systemCitation42. However, this grading system was never designed to identify mixed pain syndromes; therefore, its ability to identify a neuropathic component in situations such as low back pain, osteoarthritis pain, persistent postsurgical pain or cancer pain remains uncertain and raises doubts about its suitability as a gold standard.

Also, there are currently no validated screening tools specific for the detection of mixed pain, or of the nociceptive pain component alone. However, there are existing validated tools for neuropathic pain screening or assessment that can be deployed to detect the presence of this componentCitation43. These tools include the self-reported Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (s-LANSS) toolCitation44, Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions (DN4)Citation45 and painDETECTCitation38, as elaborated in the NeuPSIG guidelines on assessment of neuropathic painCitation46. Notably, a recent systematic review evaluating the performance of screening tools for neuropathic components in cancer pain found that it is clinically more challenging to distinguish predominantly neuropathic pain from predominantly nociceptive pain within a mixed pain context, particularly for clinicians with little or no training in pain assessmentCitation24. Consequently, the reviewers assessed the performance of currently available screening tools and identified concordance between the clinician diagnosis and screening tool outcomes for LANSS, DN4 and painDETECT, leading them to conclude that these screening tools are practical for identifying potential cases of neuropathic cancer painCitation24.

It is important to note that the pain part of a neuropathic problem has to be established using other pieces of the diagnostic armamentarium in addition. Additional diagnostic assessments, including quantitative sensory testingCitation47, corneal confocal microscopyCitation48 and skin biopsyCitation49, may be helpful for the clinician to diagnose the presence of a neuropathic pain component in rare but challenging cases (e.g. small-fibre neuropathy). Detection of elevated inflammatory markers, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein (CRP), may be used to identify the presence of inflammation, which would support a possible nociceptive pain componentCitation50. However, no diagnostic gold standard is available.

The authors concluded that, as there is no available validated tool to screen for the nociceptive pain component at present, the diagnosis of mixed pain is made based on clinical judgement following detailed history-taking and thorough physical examination, rather than by formal confirmation following explicit screening or diagnostic criteria.

3. We do not know how to provide definitive treatment for mixed pain

The phenotypical complexity of mixed pain makes assessment and diagnosis of the mixed-pain patient considerably challenging for the clinician, and treatment even more so – no clear guidelines specific to mixed pain are currently available and, thus, the best guidance on treatment decision-making can be derived only from treatment recommendations for neuropathic painCitation36.

Discussion

Given the foregoing considerations, the authors provide a few practice pearls for clinicians who encounter a patient with presumptive mixed pain ().

Table 1. Mixed pain: practice pearls.

One criticism that has been levelled at Kosek et al. regarding their conceptualization of “nociplastic pain” is that the term is “nothing more than a rather trivial clinical observation… [that] serves [no] defined clinical or scientific purpose”Citation8. It is not unlikely that such a criticism will also be levelled at this present effort to consolidate current knowledge on mixed pain, or any future effort to articulate a mechanistic definition of mixed pain.

In response, the authors align themselves with the position staked by Kosek and colleagues, who pointed out that any novel pain descriptor is aimed at filling a gap in our lexicon of pain terminology for patients presenting with chronic painCitation51. As “nociplastic pain” was conceptualized to fill the lexicon gap between the two current concepts available to describe the biomedical or somatic dimension of the pain experience (i.e. nociceptive and neuropathic), so too will a future definition of mixed pain fulfil the role of a mechanistic descriptor for the pain presenting as various combinations of nociceptive, neuropathic or nociplastic components.

Furthermore, even as such an advancement of the current conceptual framework beyond nociceptive/neuropathic/nociplastic is crucial in and of itself, it assumes greater importance in the context of our patients with chronic pain, who still are often told that their pain is not real or “all in their head”. A future definition of mixed pain will allow affected patients to validate their own experience of chronic pain, facilitating doctor–patient communication and positively impacting on treatment outcomes. Moreover, it should spur a more widespread recognition that chronic pain is a disease in its own right – a concept that is familiar to pain clinicians and researchers but has still not sufficiently spread throughout the medical community and the lay publicCitation52.

Importantly, the authors hope that this foundational work on mixed pain, together with the recent conceptualization of nociplastic pain, will serve as an impetus for future research, particularly in the detection, quantification and definition of peripheral and central sensitization, and of alterations in nociception. This current lack of tools and techniques to gauge nervous system sensitization in both clinical practice and the laboratory setting prevents the full characterization of pain-generating mechanisms in patients with nociplastic pain, as well as in those presenting with two or more pain componentsCitation15. What the authors believe to be the most important questions for future research into mixed pain are summarized in .

Table 2. Important questions for future research.

Conclusions

To the authors’ knowledge, this paper represents a first published consolidation of knowledge on the mixed pain concept which can serve as a foundation for future attempts at generating a mechanistic and/or clinical definition of mixed pain. Based on the preceding considerations, the group formed consensus around the following starting point:

“Mixed pain is a complex overlap of the different known pain types (nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic) in any combination, acting simultaneously and/or concurrently to cause pain in the same body area. Either mechanism may be more clinically predominant at any point of time. Mixed pain can be acute or chronic.”

It is foreseeable that this advancement of the current conceptual framework of the neurobiological basis of chronic pain beyond nociceptive, neuropathic and nociplastic pain will gain increasing acceptance even as it is debated and discussed, given that a clear definition of mixed pain will have profound implications – this may, indeed, form the foundation of forthcoming clinical diagnostic criteria and treatment strategies.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The expert consensus meetings, and medical writing and editing services, were sponsored by Merck Consumer Health.

Author contributions: All authors were involved in the conception and design of the manuscript. R.F. was responsible for drafting of the paper; all authors participated in revising it critically for intellectual content; and all authors gave the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

R.F. reports personal fees from Astellas, Grünenthal, Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Develco, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Galapagos, outside the submitted work. C.A.C.O. reports that he is a consultant for Merck. J.C. reports personal fees from Pfizer and Merck. K.Y.H. has received honoraria from Halyard Healthcare, Pfizer, Menarini and Merck, outside the submitted work. A.L.S. discloses that she is a consultant or speaker for Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Teva, Merck and Grünenthal. M.D.S. reports that she is a member of a Merck clinical advisory board. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Jose Miguel (Awi) Curameng of MIMS (Hong Kong) Limited for providing medical writing and editing support for this manuscript.

References

- Freynhagen R. [“Mixed pain” as new rationale: pie in the sky or pie on the plate.] Psychoneuro. 2005:31:103–105. German.

- Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, et al. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain. 2016;157:1382–1386.

- Ross E. Moving towards rational pharmacological management of pain with an improved classification system of pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:1529–1530.

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70:1630–1635.

- IASP Terminology [Internet]. Washington DC, USA: International Association for the Study of Pain; c2018 [updated 2017 Dec 14; cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/terminology?navItemNumber=576

- IASP Council Adopts Task Force Recommendation for Third Mechanistic Descriptor of Pain [Internet]. Washington DC, USA: International Association for the Study of Pain; c2018 [updated 2017 Nov 14; cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=6862-&navItemNumber=643

- Brummett C, Clauw D, Harris R, et al. We agree with the need for a new term but disagree with the proposed terms. Pain. 2016;157:2876.

- Granan LP. We do not need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states! Not yet. Pain. 2017;158:179.

- Argoff CE. New Insights Into Pain Mechanisms and Rationale for Treatment [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: WebMD LLC; c1994–2018 [updated 2011 Sep 16; cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/742578_transcript

- Takahashi N, Shirado O, Kobayashi K, et al. Classifying patients with lumbar spinal stenosis using painDETECT: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:90.

- Samolsky Dekel BG, Remondini F, et al. Development, validation and psychometric properties of a diagnostic/prognostic tool for breakthrough pain in mixed chronic-pain patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;141:23–29.

- Portenoy RK, Bennett DS, Rauck R, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of breakthrough pain in opioid-treated patients with chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2006;7:583–591.

- Roosink M, Guerts ACH, Ijzerman MJ. Defining post-stroke pain: diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:344.

- Wilder-Smith OHG, Tassonyi E, Arendt-Nielsen L. Preoperative back pain is associated with diverse manifestations of central neuroplasticity. Pain. 2002;97:189–194.

- Andrews N. What’s in a Name for Chronic Pain? [Internet]. Washington DC, USA: Pain Research Forum; c2018 [updated 2018 Feb 5; cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.painresearchforum.org/news/92059-whats-name-chronic-pain

- Ibor PJ, Sánchez-Magro I, Villoria J, et al. Mixed Pain Can Be Discerned in the Primary Care and Orthopedics Settings in Spain: A Large Cross-Sectional Study. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:1100–1108.

- Romanò CL, Romanò D, Lacerenza M. Antineuropathic and antinociceptive drugs combination in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:154781.

- Grond S, Radbruch L, Meuser T, et al. Assessment and treatment of neuropathic cancer pain following WHO guidelines. Pain. 1999;79:15–20.

- Junker U, Baron R, Freynhagen R. [Chronic pain: the “mixed pain concept” as a new rationale]. Dtsch Arztebl. 2004;101:1393–1394. German.

- Baron R, Binder A. [How neuropathic is sciatica? The mixed pain concept]. Orthopäde. 2004;33:568–575. German.

- Freynhagen R, Busche P. [The mixed pain concept]. Psychoneuro. 2005;31:331–333. German.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R. The evaluation of neuropathic components in low back pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:185–190.

- Fallon MT. Neuropathic pain in cancer. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:105–111.

- Mulvey MR, Boland EG, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain in cancer: systematic review, performance of screening tools and analysis of symptom profiles. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:765–774.

- Bennett MI, Rayment C, Hjermstad M, et al. Prevalence and aetiology of neuropathic pain in cancer patients: a systematic review. Pain. 2012;153:359–365.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196.

- Perrot S. Osteoarthritis pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:90–97.

- Thakur M, Dickenson AH, Baron R. Osteoarthritis pain: nociceptive or neuropathic? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:374–80.

- Hochman JR, French MR, Bermingham SL, Hawker GA. The nerve of osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1019–1023.

- French HP, Smart KM, Doyle F. Prevalence of neuropathic pain in knee or hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:1–8.

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618–1625.

- Dualé C, Ouchchane L, Schoeffler P, et al. Neuropathic aspects of persistent postsurgical pain: a French multicenter survey with a 6-month prospective follow-up. J Pain. 2014;15:24.e1–24.e20.

- Förster M, Mahn F, Gockel U, et al. Axial low back pain: one painful area – many perceptions and mechanisms. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68273.

- Cedraschi C, Delézay S, Marty M, et al. “Let’s talk about OA pain”: a qualitative analysis of the perceptions of people suffering from OA. Towards the development of a specific pain OA-related questionnaire, the Osteoarthritis Symptom Inventory Scale (OASIS). PLoS One. 2013;8:e79988.

- Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, et al. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain. 2011;152:566–572.

- Binder A, Baron R. The pharmacological therapy of chronic neuropathic pain. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:616–626.

- Farajidavar A, Gharibzadeh S, Towhidkhah F, et al. A cybernetic view on wind-up. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:304–306.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1911–1920.

- Gálvez R, Marsal C, Vidal J, et al. Cross-sectional evaluation of patient functioning and health-related quality of life in patients with neuropathic pain under standard care conditions. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:244–255.

- Haroun OM, Hietaharju A, Bizuneh E, et al. Investigation of neuropathic pain in treated leprosy patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Pain. 2012;153:1620–1624.

- Müller-Schwefe G, Morlion B, Ahlbeck K, et al. Treatment for chronic low back pain: the focus should change to multimodal management that reflects the underlying pain mechanisms. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1199–1210.

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016;157:1599–1606.

- Attal N, Bouhassira D, Baron R. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain through questionnaires. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:456–466.

- Bennett MI, Smith BH, Torrance N, et al. The S-LANSS score for identifying pain of predominantly neuropathic origin: validation for use in clinical and postal research. J Pain. 2005;6:149–158.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H A, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114:29–36.

- Haanpää M, Attal N, Backonja M, et al. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain. 2011;152:14–27.

- Vollert J, Maier C, Attal N, et al. Stratifying patients with peripheral neuropathic pain based on sensory profiles: algorithm and sample size recommendations. Pain. 2017;158:1446–1455.

- Tavakoli M, Quattrini C, Abbott C, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: a novel noninvasive test to diagnose and stratify the severity of human diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1792–1797.

- Lauria G, Hsieh ST, Johansson O, et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:903–912,e44–e49.

- Koch A, Zacharowski K, Boehm O, et al. Nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory cytokines correlate with pain intensity in chronic pain patients. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:32–37.

- Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, et al. Reply. Pain. 2017;158(1):180.

- National Poll: Chronic Pain and Drug Addiction [Internet]. Arlington, VA, USA: Research!America; c2018 [updated 2013 Apr; cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.researchamerica.org/sites/default/files/uploads/March2013painaddiction.pdf