Abstract

Objective

We sought to summarize current recommendations for the diagnosis of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) and describe available management options, highlighting a newer US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agent, eluxadoline.

Methods

Literature on IBS-D was assessed up to January 2020 using PubMed, with key search terms including “IBS-D diagnosis”, “IBS-D management”, and “eluxadoline”.

Results

IBS is a common gastrointestinal disorder affecting up to 14% of US adults and is particularly prevalent in women and those aged under 50. Symptoms include abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits (i.e. diarrhea and/or constipation subtyped based on the predominant stool pattern). As IBS-D is challenging to manage with varying symptom severity, effective treatment requires a personalized management approach. Evidence-based therapeutic options endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association and the American College of Gastroenterology can be used to effectively guide treatment. Dietary and lifestyle modifications, including adequate hydration, reducing caffeine and alcohol intake, and increasing soluble fiber intake may lead to symptom improvement. Over-the-counter medications such as loperamide are frequently recommended and may improve stool frequency and rectal urgency; however, for the outcome of abdominal pain, mixed results have been observed. Several off-label prescription medications are useful in IBS-D management, including tricyclic antidepressants, bile acid sequestrants, and antispasmodics. Three prescription medications have been approved by the FDA for IBS-D: alosetron, eluxadoline, and rifaximin.

Conclusions

IBS-D can be effectively managed in the primary care setting in the absence of alarm features. Benefits and risks of pharmacologic interventions should be weighed during treatment selection.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the seventh most common diagnosis made by primary care clinicians and the most common diagnosis made by gastroenterologists in the USCitation1–3. It affects up to 14% of US adultsCitation4,Citation5, with higher prevalence among women and those under 50 years of ageCitation4. IBS is a chronic disorder involving the gut–brain axis associated with motility disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, altered mucosal and immune function, gut microbiota, and central nervous system processingCitation6. It presents with abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits (i.e. constipation and/or diarrhea) and is classified into subtypes based on the predominant stool pattern: constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or mixed (IBS-M). Approximately one-third of patients with IBS are classified as having IBS-DCitation7,Citation8. Symptoms of IBS-D extend beyond diarrhea and abdominal pain, and include rectal urgency and abdominal bloatingCitation9. To help clinicians classify a diagnosis of a patient with a functional gastrointestinal disorder such as IBS, a set of criteria called the Rome criteria is used.

IBS-D has a significant negative impact on patients’ quality of life, exceeding the quality of life decrements seen in asthma, gastrointestinal reflux disease, migraine headachesCitation10–12, and even IBS-CCitation13. A number of comorbid conditions have been associated with IBS, including migraine headaches, fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, generalized anxiety, and major depressionCitation14. IBS-D imposes a substantial economic burden on society and payers due to increased healthcare useCitation15–18.

IBS-D can be a challenging condition to manage effectively. Symptoms range from mild and intermittent to severe and continuousCitation19, requiring tailored management strategies. The cornerstone of treatment for most patients with IBS is dietary and lifestyle modifications in conjunction with an effective therapeutic clinician–patient relationship. Many patients require over-the-counter and/or prescription medications to achieve adequate symptom control. Patient symptom patterns, comorbidities, and preferences play an important role in determining appropriate treatments. Based on the IBS in America internet survey, nearly 80% of individuals with IBS reported having tried a non-prescription treatment (i.e. loperamide, fiber, and bismuth subsalicylate), with fewer than 20% being “very satisfied” with eachCitation20.

The prevalence, impact on quality of life, and healthcare burden of IBS-D make it a worthy focus for novel therapeutics. There are numerous reasonably effective interventions for IBS-D, including lifestyle, diet, and pharmacologic tools. Despite such treatments, some patients continue to have substantial symptom burden and impairments to quality of life. Here we review current recommendations for the diagnosis of IBS-D and provide a brief overview of available management options, while highlighting the newest US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agent, eluxadoline.

Literature search method

A literature review was performed using PubMed; key search terms included “IBS-D diagnosis”, “IBS-D management”, and “eluxadoline”. Searches of articles were performed up to January 2020 to identify the most recently published articles. For inclusion, the studies were required to be published in English.

Diagnosis

Approximately 40% of patients with IBS are cared for by their primary care clinician and never require consultation from a gastroenterologistCitation5. A primary care clinician can provide the majority of evidence-based care given by a gastroenterologist; however, clinicians may prefer to refer patients with IBS to a specialist for further work-up when the diagnosis of IBS is not secure.

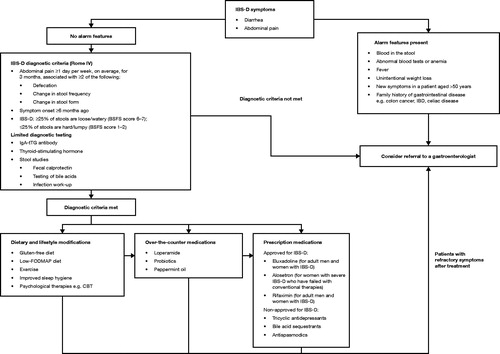

In the absence of alarm features which may suggest the presence of an organic disease, IBS may be safely diagnosed and managed in the primary care setting. In patients who meet the Rome IV criteria for IBS-D symptoms (see below), limited testing is recommended, including celiac serology (i.e. IgA-tTG antibody and quantitative IgA level), fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin (or serum C-reactive protein if stool studies are not available), thyroid-stimulating hormone, and stool infectious work-up (i.e. Giardia direct fluorescent antigen) in patients with risk factors (for example, having travelled to endemic areas).

If these tests are abnormal or if alarm features are present (blood in the stool, fever, unintentional weight loss, new symptoms in a patient aged >50 years, an abdominal mass or ascites, or a family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease), additional testing (i.e. colonoscopy and/or imaging of the abdomen) and potential referral to a gastroenterologist may be indicatedCitation21. Additionally, bile acid malabsorption (BAM) [also known as bile acid diarrhea] should be considered as a potential etiology. In one systematic review, 10–32% of patients presenting with chronic diarrhea had varying levels of severity of BAM, as assessed by 7-day SeHCAT (tauroselcholic [75Selenium] acid) thresholdsCitation22, while a meta-analysis found that 28.1% (n = 908) of patients with IBS-D have BAMCitation23. Given there is no current gold standard diagnostic test for BAM and existing tests may not be routinely available, empiric bile acid suppression therapy may be considered or a gastroenterologist consultedCitation24.

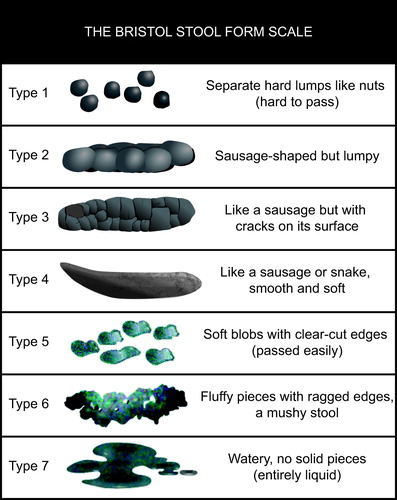

The pathophysiology of IBS is multifactorial and a variety of physiological, psychological, and early-life factors likely contribute to the onset of symptoms. Identified abnormalities include changes in the gut microbiota (especially post infectious diarrhea or after antibiotics), low-grade mucosal inflammation, immune dysfunction, abnormal bile salt absorption, genetic factors, a history of childhood abuse, gastrointestinal infections, and a variety of dietary hypersensitivitiesCitation22,Citation25–30. A biomarker panel test has been developed recently for diagnosis of IBS-DCitation31; however, it is only valid for post-infectious IBS-D and has not been definitively established as diagnostic. Hence, the current diagnostic criteria (i.e. Rome IV criteria) are symptom-based. To meet the Rome IV criteria for IBS, patients must have abdominal pain for ≥1 day per week for the preceding 3 months that is associated with at least two of the following three criteria: abdominal pain associated with defecation, change in stool frequency, or change in stool formCitation7,Citation32. Symptom onset must have occurred ≥6 months prior to diagnosis. A patient is considered to have the IBS-D subtype if more than one-quarter of bowel movements (on days with an abnormal bowel movement) are a Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) scoreCitation33 of 6–7 (diarrhea) and fewer than one-quarter are a score of 1–2 (constipation) ().

Figure 1. Bristol Stool Form ScaleCitation33.

Overview of current management options

An overview of currently available management options for IBS-D, and their endorsement by the American College of Gastroenterology, is shown in Citation34. The American Gastroenterological Association also provides guidelines for the pharmacological management of IBSCitation35.

Table 1. Overview of IBS-D management options, including ACG recommendationsCitation34.

Dietary and lifestyle modifications

Approximately two-thirds of patients with IBS-D report worsening symptoms after meals, and up to 84% report food intolerancesCitation75,Citation76; thus, it is not surprising that dietary interventions may be of benefit. The use of soluble fiber (e.g. psyllium) may be helpful in some patients with IBS-DCitation77, though it is more commonly recommended for patients with IBS-C and may worsen bloating. There are increasing data to support the efficacy of a low-FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) diet ()Citation78,Citation79. A guide to the low-FODMAP diet is available from the American Gastroenterological AssociationCitation80. Exercise and improving sleep hygiene may also help reduce IBS symptoms. Multiple studies have shown that psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, may also improve IBS symptomsCitation34,Citation47–52.

Over-the-counter medications

Over-the-counter medications should be considered if dietary and lifestyle modifications are not possible or have proved ineffective. The most commonly used over-the-counter treatment for IBS-D is loperamide, a non-scheduled, synthetic opioid agonist with antidiarrheal effectsCitation81. Loperamide is generally effective in reducing the duration of symptoms associated with acute diarrheaCitation82. It has also been shown to significantly improve stool consistency and urgency in small, placebo-controlled clinical trials in patients with IBSCitation54,Citation55,Citation83, with a favorable safety profile at recommended doses (for acute diarrhea: 4 mg initially, then 2 mg after each unformed stool; for chronic diarrhea: 2–4 mg once or twice daily; no more than 16 mg to be taken per day). Given its favorable safety profile and low cost, loperamide is generally recommended as the first-line pharmacological treatment option for IBS-DCitation84. However, clinical trial results addressing the efficacy of loperamide for pain in patients with IBS have been mixed; hence, clinicians should recognize that patients may not attain adequate pain relief, relief from bloating, and improvement of symptoms with this agentCitation34.

As changes in gut flora may be a factor in triggering IBS-D symptoms, probiotics can improve bloating and flatulence in some patientsCitation85–87. However, questions remain as to the specific type of probiotic, dose, and duration of therapy that should be recommendedCitation88. Mixed results have been observed for enteric-coated peppermint oil (180–200 mg up to 3 times a day), an antispasmodic, which has been shown to improve abdominal pain and global symptoms compared to placebo, but does not improve stool consistency and may worsen symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux diseaseCitation63,Citation64,Citation87,Citation89,Citation90.

Prescription medications: not FDA-approved for the treatment of IBS-D

Should over-the-counter medications fail to sufficiently alleviate symptoms, several prescription medications that are not approved by the FDA specifically for the treatment of IBS-D are commonly prescribed and may be useful in its management, such as tricyclic antidepressants, bile acid sequestrants, and antispasmodics. Tricyclic antidepressants are a low-cost option that mediate central pain, improve visceral pain, have antispasmodic properties, and slow gastrointestinal transitCitation91. In a recent systematic review, tricyclic antidepressants were found to demonstrate modest efficacy in relieving pain and overall symptoms of IBSCitation34. Treatment begins at a low dose (i.e. 10–25 mg a day), with gradual titration to 75–100 mg. Higher doses should be avoided due to the potential for severe heart problems; patients should be screened for cardiac conduction diseases before initiatingCitation34,Citation65. Several studies have shown that up to 40% of patients with IBS-D have evidence of BAM. In these patients, bile acid sequestrants may improve stool consistency and frequency, though placebo-controlled trials are currently lackingCitation65,Citation92. Smooth muscle antispasmodics may relieve abdominal pain and overall symptoms, though limited data exist for the current antispasmodics available in the United States (i.e. hyoscyamine and dicyclomine) and anticholinergic properties limit their use, particularly at higher dosesCitation35,Citation67,Citation93.

Prescription medications: FDA-approved for the treatment of IBS-D

Three prescription medications are currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of IBS-D: alosetron, eluxadoline, and rifaximin. Rifaximin, a minimally absorbed oral antibiotic, has been available since 2004 (indicated for treating travelers’ diarrhea) and was approved for IBS-D in 2015Citation94. In two Phase 3 clinical trials in patients with IBS without constipation, 41% of patients treated with rifaximin 550 mg 3 times a day for 14 days achieved sustained adequate relief of IBS symptoms (i.e. reported at least “adequate relief” for at least 2 out of the first 4 weeks after treatment), which was significantly higher than placebo (31%)Citation73. In a re-treatment trial with rifaximin, approximately two-thirds of patients who responded to rifaximin had recurrence of symptoms up to 18 weeks after treatment. Patients who experienced a recurrence of symptoms showed improvement in IBS symptoms compared to placebo after two subsequent treatments of rifaximinCitation95. Rifaximin appears to be well tolerated with a side-effect profile similar to placebo and specifically no evidence of microbial resistance or secondary infections such as Clostridium difficileCitation94–96. In a recent meta-analysis of alosetron, eluxadoline, ramosetron, and rifaximin, rifaximin ranked highest in terms of safety; however, interpretation should consider the lack of direct comparisons of patient populations and outcomes that are inherent to meta-analysesCitation97.

Alosetron, a 5-HT3 antagonist, was approved in 2000 for treating IBS-D in women. It was withdrawn in 2001 due to adverse events of severe constipation and ischemic colitis, and re-introduced in 2002 via a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy for women with severe, disabling, refractory IBS-DCitation68,Citation98. Adequate relief was reported in 41–43% of women with IBS-D in clinical trials; urgency and stool frequency also decreasedCitation69,Citation70,Citation99. A lower starting dose is now recommended (0.5 mg once daily rather than 1.0 mg twice daily) to reduce adverse events related to constipation, not including ischemic colitis, which occurs in approximately 1 in 750 to 1000 patients. The dose may be increased to 1.0 mg twice daily if symptoms are not adequately controlled. In a network meta-analysis of IBS-D treatments mentioned previously, alosetron ranked first in terms of efficacy, based on FDA-recommended composite trial endpoints. However, the authors acknowledge the inherent caveats of meta-analyses, most importantly the influence of data heterogeneityCitation97. Direct drug comparisons in a clinical setting would be desirable to support the study’s conclusions on comparative efficacy.

Focus on eluxadoline

Enteric opioid receptors μ, κ, and δ are involved in regulating gastrointestinal motility, secretion, and visceral sensation; μ-opioid activation relieves pain and inhibits motility and secretion by slowing peristaltic contractions and increasing sphincter muscle tone.

Eluxadoline, a μ-opioid and κ-opioid receptor agonist and δ-opioid receptor antagonist, was developed with the aim of using a mixed opioid receptor profile to treat both abdominal pain and diarrhea while reducing the potential for constipation. It has minimal central nervous system penetration; consequently, the likelihood of central nervous system effects and the potential for abuse is markedly reduced. Eluxadoline was approved by the FDA in 2015 for the treatment of adults with IBS-DCitation100, and has been recommended in recent American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines for the treatment of the global symptoms of IBS-DCitation101.

Most clinicians are familiar with constipation as an adverse effect associated with use of μ-opioid analgesics. The adverse effect of constipation is common to all opioid analgesics (or other agents with meaningful intestinal μ-opioid receptor agonism). However, unlike the other effects of μ-opioids, tolerance to constipation does not occur.

Based on animal models, combining a δ-opioid receptor antagonist with a μ-opioid receptor agonist enhances its effects on visceral sensation, while reducing the potential for constipationCitation102–104. Although the exact effects of combining κ-opioid agonism is not fully understoodCitation72, it may play a role in reducing abdominal painCitation105.

Efficacy

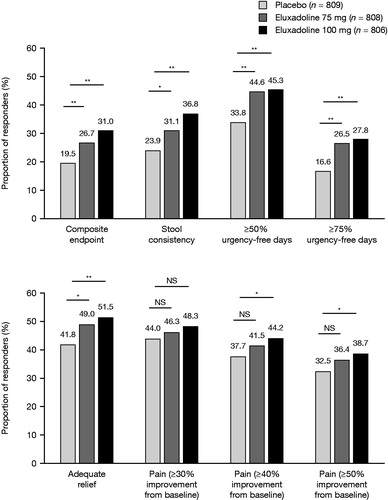

In two Phase 3 trials (N = 2425)Citation71, a significantly greater proportion of patients with IBS-D taking twice-daily eluxadoline (75 mg or 100 mg) achieved a simultaneous improvement in abdominal pain and diarrhea (BSFS score <5 or no bowel movement and ≥30% reduction in worst abdominal pain compared to baseline, on the same day, for ≥50% of treatment days) compared to placebo (31.0%, 26.7%, and 19.5% for eluxadoline 100 mg, 75 mg, and placebo, respectively: all p<.001 vs. placebo)Citation71.

Furthermore, eluxadoline also improves a constellation of symptoms associated with IBS-DCitation106. In the Phase 3 trials, patients receiving eluxadoline achieved reductions in fecal urgency, bloating, and daily number of bowel movements compared to those receiving placebo, with significantly higher proportions achieving improved stool consistency (BSFS score <5 or no bowel movement on ≥50% of treatment days) and adequate relief of symptoms ()Citation71,Citation106. A significantly higher proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline 100 mg achieved ≥40% (p=.008) or ≥50% (p=.009) reduction in their worst abdominal pain compared to placebo (not significant for ≥30% improvement)Citation71. Improvements over placebo were observed in the first week of treatment and were sustained over the 6-month clinical trial period.

Figure 2. Proportion of responders across multiple symptoms for eluxadoline compared to placebo. *p<.05; **p<.001. Pooled data from Phase 3 trials over weeks 1–26. Response criteria were defined as follows: composite response, improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score (0–10 scale where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain imaginable) vs. baseline and, on the same day, a BSFS score of <5, on ≥50% of treatment days; stool consistency, as for composite response; urgency-free days, no reported urgency episodes; adequate relief, “yes” response to the question: “Over the past week, have you had adequate relief of your irritable bowel syndrome symptoms?” on ≥50% of weeks; abdominal pain, improvement of ≥30%, ≥40%, or ≥50% in worst abdominal pain score vs. baseline, on ≥50% of treatment days. Abbreviations. BSFS, Bristol Stool Form Scale; NS, Not significant.

Eluxadoline is equally effective across demographic groups. Subgroup analyses found no clinically relevant differences in efficacy when patients were stratified by gender, race, body mass index, or history of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms or depression. However, while the pathophysiological underpinnings of this observation remain elusive, patients aged ≥65 years were more likely to respond to eluxadoline compared to those aged <65 years (100 mg dose: 40.5 vs. 30.1%, respectively), with a much greater proportion responding to the 75 mg dose (50.8 vs. 24.6%, respectively)Citation107.

Many patients in the Phase 3 trials had previously used loperamide (36.0%), of whom the majority (61.8%) reported that loperamide did not adequately relieve their IBS-D symptomsCitation108. A Phase 4 study of eluxadoline 100 mg in patients with prior inadequate symptom control with loperamide (RELIEF; N = 346) found that more than twice as many patients in the eluxadoline group achieved improvement in pain and stool consistency (≥40% worst abdominal pain improvement and BSFS score <5 or no bowel movement on ≥50% of treatment days) compared to placebo (22.7 vs. 10.3%, respectively; p<.002)Citation109.

Quality of life improvement is an important treatment consideration in IBS-D, due to the bothersome nature of symptoms and impact of psychiatric comorbiditiesCitation14,Citation110. Significantly more patients receiving eluxadoline compared to placebo in the Phase 3 trials achieved a clinically meaningful improvement in disease-specific health-related quality of life (≥14-point increase, maximum score = 100) over the study duration (26 weeks and 52 weeks), measured using the validated Irritable Bowel Syndrome – Quality of Life questionnaireCitation111. Significantly more eluxadoline-treated patients reported improvements in subscales such as interference with activity, body image, social reaction, health worry, and food avoidanceCitation112.

Safety

Nausea and constipation were the most frequent adverse events across Phase 2 and 3 trials (N = 2814); however, these led to discontinuation in only a few casesCitation113. Constipation was reported in 2.5, 7.4, and 8.1% of patients receiving placebo, eluxadoline 75 mg, and eluxadoline 100 mg, respectively; it was the most common reason for discontinuation (0.3, 1.1, and 1.5%, respectively). Nausea was reported in 5.0, 8.1, and 7.1%, respectivelyCitation113, with 0.4, 0.6, and 0.0%, respectively, discontinuing due to nauseaCitation113. Pancreatitis was the most common serious adverse event, reported in 3 (0.4%) and 4 (0.4%) patients receiving eluxadoline 75 mg and 100 mg, respectively; sphincter of Oddi spasm was reported in 2 (0.2%) and 8 (0.8%) patients on eluxadoline 75 mg and 100 mg, respectively, with all events occurring in patients without a gallbladder. There were no deaths in either study.

If a patient has mild or moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh Classes A or B) or is currently taking OATP1B1 inhibitors (gemfibrozil, antiretrovirals, cyclosporine) or OATP1B1 substrates (rosuvastatin), then the dose should be reduced to 75 mg twice daily; this is also recommended for patients with moderate or severe renal impairment, and those with end-stage renal disease not yet on dialysis. The prescribing information recommends using the lowest effective dose of rosuvastatin when eluxadoline is co-prescribedCitation72.

Due to its action on opioid receptors, eluxadoline is classed as a controlled (Schedule IV) substanceCitation114, requiring appropriate authorization, monitoring, and review of controlled substance prescriptions. However, clinical studies indicate a low potential for abuse and a low risk of dependence. A study in recreational opioid users found lower abuse potential of subtherapeutic doses of eluxadoline compared to oxycodone. Mean Drug Liking Visual Analog Scale scores, measuring the degree to which participants liked the drug effect, were close to neutral for eluxadoline, and were 25–35 points lower with eluxadoline compared with oxycodone (on a scale of 0–100)Citation115. Across the Phase 2 and 3 trials, there was no significant difference in the overall incidence of adverse events potentially related to abuse between placebo and eluxadoline (2.8, 4.3, and 2.7% for placebo, eluxadoline 75 mg, and eluxadoline 100 mg, respectively)Citation116.

Contraindications

All contraindications for eluxadoline are listed in , with key contraindications for eluxadoline described below. Eluxadoline must not be prescribed for patients without a gallbladder due to an increased risk of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and pancreatitis. Following its approval, 120 cases of possible eluxadoline-associated pancreatitis were reported to the FDA between May 2015 and February 2017, of which two patients died and 76 patients were hospitalizedCitation117,Citation118. Of 67 patients where gallbladder status was known, the majority (n = 55; 82%) did not have a gallbladderCitation118. Following these events, the FDA changed eluxadoline’s label in 2017 to contraindicate eluxadoline in these patientsCitation72. In addition, a proportion (18%) of those experiencing severe pancreatitis had an intact gallbladder; therefore, clinicians should still be vigilant about severe pancreatitis as an adverse event and any occurrences should be thoroughly investigated.

Table 2. Contraindications of eluxadolineCitation72.

Excessive alcohol consumption (defined as ≥3 alcoholic beverages per day) further increases the risk for eluxadoline-associated pancreatitis, and therefore, eluxadoline is contraindicated in patients who suffer from alcohol use disorderCitation72. No cases of pancreatitis were reported in the Phase 4 RELIEF study, which excluded patients without a gallbladder and those with a history of excessive alcohol consumptionCitation109.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction occurs when the smooth muscle surrounding the end of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct (the sphincter of Oddi) cannot contract and relax properly, causing obstruction of bile and pancreatic juice. Signs and symptoms include: upper abdominal pain or epigastric pain that radiates to the back or shoulder, with or without nausea or vomiting, fever, elevated pancreatic enzymes or liver transaminases, jaundice, pruritus, brown urine, weight loss or decreased appetite, fatigue, and greasy or clay-colored stools. Acute pancreatitis may result from sphincter of Oddi dysfunctionCitation119; symptoms include: severe central abdominal pain that radiates to the back, with or without nausea or vomiting, fever, diarrhea, abdominal swelling or tenderness, tachycardia, and jaundice. Eluxadoline should be discontinued in patients exhibiting signs and symptoms of either sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or pancreatitis.

Most cases (approximately 80%) of serious pancreatitis or sphincter of Oddi spasm associated with eluxadoline occurred within a week of starting treatment, with patients often developing symptoms after 1 or 2 dosesCitation118. All cases in Phase 2 and 3 trials were clinically resolved with medication discontinuation: all patients discontinued treatment and achieved lipase normalization within days (except one patient with alcoholism, who required several weeks)Citation113.

Eluxadoline is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh Class C), as it may cause unacceptable increases in eluxadoline plasma concentrations in these patients (). The Child-Pugh score uses five clinical markers to estimate the severity of liver disease. A high score (Class C: 10–15 points) indicates severe disease, while Classes A and B (5–6 and 7–9 points, respectively) indicate mild or moderate hepatic impairment, respectively. For patients with hepatic impairment classed as mild or moderate, the 75 mg dose of eluxadoline is recommendedCitation72,Citation120.

As discussed previously, constipation was reported as a common adverse event in Phase 2 and 3 trialsCitation113, and was the most common reason for study discontinuation. Post-marketing surveillance of eluxadoline has identified cases of severe constipation, of which some required hospitalizationCitation72. Therefore, patients with a history of severe or chronic constipation should not use eluxadoline.

There is a high prevalence of IBS-D in the US, and while the condition is not life-threatening or associated with major complications, it can prove debilitating for patients, with significant associated costsCitation4,Citation10,Citation16,Citation17. Therefore, while the possibility of serious side effects with eluxadoline must be balanced against the non-fatal nature of the disease and the risk factors of each patient, eluxadoline represents a viable treatment option for patients with IBS-D, given its efficacy in alleviating a range of abdominal and bowel symptomsCitation106.

Implications for clinical practice

Managing patients with IBS-D presents unique challenges for clinicians, given the unpredictable and chronic nature of the condition. In the absence of alarm features, the diagnosis and appropriate management of IBS-D can be achieved within a primary care setting. Patients with typical symptoms of IBS-D without alarm features should be confidently diagnosed with only limited diagnostic testing.

Dietary and lifestyle modifications are the cornerstone of IBS-D treatment and should be the first intervention considered for disease management. If modifications prove ineffective, over-the-counter treatments (i.e. loperamide) are generally first-line therapies. If these maneuvers are ineffective, prescription medications may be the appropriate next management option (). Other potential options for persistent IBS-D symptoms include low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, bile acid sequestrants, and antispasmodics; however, there is minimal or low-quality evidence for their efficacy in IBS-D treatment and they are not FDA-approved for this indicationCitation121–123.

Figure 3. Diagnosis and management flow diagram for IBS-D. Management options should be discussed and selected through shared decision-making with the patient. They often begin with dietary and lifestyle modifications, transitioning to over-the-counter and prescription medications if symptoms do not improve. Abbreviations. BSFS, Bristol Stool Form Scale; CBT, Cognitive behavioral therapy; FODMAP, Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols; IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; IBS-D, Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; tTG, Tissue transglutaminase.

Alosetron, eluxadoline, and rifaximin are approved prescription medications for the treatment of IBS-D, and their exact roles in IBS management for different patient populations are still under investigationCitation124. In the absence of clinical data directly comparing these treatments, a treatment choice should be made at the physician’s discretion, after taking American College of Gastroenterology recommendations and each drug’s indication, contraindications, and safety profile into account. The risks and benefits for each patient should also be thoroughly weighed. For instance, alosetron has demonstrated efficacy in treating IBS-D but is only indicated for women with severe disease who have failed other treatments. Rifaximin has a favorable safety profile and an attractive 2-week treatment period that may be repeated twiceCitation73, and while data indicate relapse may occur, they are also supportive of re-treatment in these patientsCitation95,Citation121. Eluxadoline, working by a different mechanism than other treatment options, has demonstrated efficacy across a range of IBS-D symptoms, together with a generally acceptable safety profile in low-risk patients. Recent ACG guidelines suggest clinicians consider eluxadoline for the treatment of the global symptoms of IBS-D in low-risk patientsCitation101. Eluxadoline is only an appropriate therapeutic tool for IBS-D as long as clinicians evaluate patient risk for known adverse effects of sphincter of Oddi spasm, acute pancreatitis, and severe constipation, while observing the appropriate contraindications to its use and fully disclosing the risks and potential benefits to the patient.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This review was sponsored by Allergan plc, Dublin, Ireland (prior to acquisition by AbbVie Inc.). Allergan (now AbbVie) provided suggestions for topic ideas and for authors of this manuscript to Complete HealthVizion, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA. Allergan (now AbbVie) was not involved in the development of the manuscript with the authors or the vendor. Allergan (now AbbVie) had the opportunity to review the final version of the manuscript and provide comments; however, the authors maintained complete control over the content of the paper.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

A Lembo has served on advisory boards for Allergan (now AbbVie), Ardylex, Mylan, IM Health, Bayer, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Salix Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Shire. L Kuritzky has served on advisory boards for Salix Pharmaceuticals and Shire, and on speaker bureaus for Shire and Allergan (now AbbVie). B Lacy has served on advisory boards for IM Health, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Shire, and as a consultant for Viver. The authors have no other financial or other relationships to disclose. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception, design, and content of the paper as well as drafting and revising it critically for intellectual content. Final approval of the published version was given by all authors, who agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors met the ICMJE authorship criteria. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship.

Acknowledgements

Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Helena Cant, MChemPhys, and Amy Graham, PhD, of Complete HealthVizion, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA and funded by Allergan plc, Dublin, Ireland (prior to acquisition by AbbVie Inc.).

References

- American Gastroenterological Association. IBS in America: survey summary findings [Internet]; 2015 [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available from: http://www.multivu.com/players/English/7634451-aga-ibs-in-america-survey/docs/survey-findings-pdf-635473172.pdf.

- Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254–272.e11.

- American College of Gastroenterology. Interactive IBS tools [Internet]; 2019 [cited 2019 Jul 22]. Available from: https://gi.org/patients/gi-health-and-disease/interactive-ibs-tools/.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(7):712–721.

- Hungin APS, Chang L, Locke GR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(11):1365–1375.

- Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(2):151–163.

- Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1393–1407.

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480–1491.

- Lin S, Mooney PD, Kurien M, et al. Prevalence, investigational pathways and diagnostic outcomes in differing irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26(10):1176–1180.

- Buono JL, Carson RT, Flores NM. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):35.

- ten Berg MJ, Goettsch WG, van den Boom G, et al. Quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome is low compared to others with chronic diseases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(5):475–481.

- Frank L, Kleinman L, Rentz A, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with other chronic diseases. Clin Ther. 2002;24(4):675–689.

- Singh P, Staller K, Barshop K, et al. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea have lower disease-specific quality of life than irritable bowel syndrome-constipation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(26):8103–8109.

- Lackner JM, Ma C-X, Keefer L, et al. Type, rather than number, of mental and physical comorbidities increases the severity of symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1147–1157.

- Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(9):1023–1034.

- Buono JL, Mathur K, Averitt AJ, et al. Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: retrospective analysis of a U.S. commercially insured population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):453–460.

- Törnblom H, Goosey R, Wiseman G, et al. Understanding symptom burden and attitudes to irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea: results from patient and healthcare professional surveys. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(9):1417–1427.

- Flores NM, Tucker C, Carson RT, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea (IBS-D) by disease severity among patients in the EU5 region. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A514–A515.

- Drossman DA, Chang L, Bellamy N, et al. Severity in irritable bowel syndrome: a Rome Foundation Working Team report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(10):1749–1759.

- Rangan V, Ballou S, Shin A, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center GI Motility Working Group, et al. Use of treatments for irritable bowel syndrome and patient satisfaction based on the IBS in America Survey. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):786–788.e1.

- Moayyedi P, Mearin F, Azpiroz F, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis and management: a simplified algorithm for clinical practice. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(6):773–788.

- Wedlake L, A’Hern R, Russell D, et al. Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(7):707–717.

- Slattery SA, Niaz O, Aziz Q, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of bile acid malabsorption in the irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(1):3–11.

- Carrasco-Labra A, Lytvyn L, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. AGA technical review on the evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in adults (IBS-D). Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):859–880.

- Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):133–146.

- Drossman DA. Abuse, trauma, and GI illness: is there a link? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(1):14–25.

- Lembo A, Zaman M, Jones M, et al. Influence of genetics on irritable bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux and dyspepsia: a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(11):1343–1350.

- Ek WE, Reznichenko A, Ripke S, et al. Exploring the genetics of irritable bowel syndrome: a GWA study in the general population and replication in multinational case-control cohorts. Gut. 2015;64(11):1774–1782.

- Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, Rome Foundation Committee, et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62(1):159–176.

- Ford AC, Talley NJ. Mucosal inflammation as a potential etiological factor in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(4):421–431.

- Morales W, Rezaie A, Barlow G, et al. Second-generation biomarker testing for irritable bowel syndrome using plasma anti-CdtB and anti-vinculin levels. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(11):3115–3121.

- Palsson OS, Whitehead WE, van Tilburg MAL, et al. Development and validation of the Rome IV Diagnostic Questionnaire for adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1481–1491.

- Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920–924.

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD, ACG Task Force on Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(Suppl 2):1–18.

- Weinberg DS, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ, American Gastroenterological Association, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1146–1148.

- Aziz I, Trott N, Briggs R, et al. Efficacy of a gluten-free diet in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea unaware of their HLA-DQ2/8 genotype. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(5):696–703:e1.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):508–514.

- Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, et al. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):320–328.

- de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(9):895–903.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, et al. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67–75.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Liljebo T, et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1399–1407.

- Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, et al. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64(1):93–100.

- Eswaran S, Chey WD, Jackson K, et al. A diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols improves quality of life and reduces activity impairment in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(12):1890–1899.

- Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142(8):1510–1518.

- Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, et al. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(5):487–495.

- Lacy BE. The science, evidence, and practice of dietary interventions in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(11):1899–1906.

- Wang B, Duan R, Duan L. Prevalence of sleep disorder in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(3):141–150.

- Patel A, Hasak S, Cassell B, et al. Effects of disturbed sleep on gastrointestinal and somatic pain symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(3):246–258.

- Buchanan DT, Cain K, Heitkemper M, et al. Sleep measures predict next-day symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(9):1003–1009.

- Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Keefer L, et al. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(1):47–57.

- Johannesson E, Ringström G, Abrahamsson H, et al. Intervention to increase physical activity in irritable bowel syndrome shows long-term positive effects. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(2):600–608.

- Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(5):915–922.

- Zheng H, Li Y, Zhang W, et al. Electroacupuncture for patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome or functional diarrhea: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(24):e3884.

- Hovdenak N. Loperamide treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1987;130:81–84.

- Lavö B, Stenstam M, Nielsen AL. Loperamide in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome–a double-blind placebo controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1987;130:77–80.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Drug safety communications: FDA warns about serious heart problems with high doses of the antidiarrheal medicine loperamide (Imodium), including from abuse and misuse [Internet]; 2016 [cited 2020 Oct 1]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM505108.pdf.

- Akel T, Bekheit S. Loperamide cardiotoxicity: "A brief review". Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2018;23(2):e12505.

- Vidarsdottir H, Vidarsdottir H, Moller PH, et al. Loperamide-induced acute pancreatitis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:517414.

- Dierksen J, Gonsoulin M, Walterscheid JP. Poor man's methadone: a case report of loperamide toxicity. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015;36(4):268–270.

- MacDonald R, Heiner J, Villarreal J, et al. Loperamide dependence and abuse. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015209705.

- Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA. Loperamide, the "poor man's methadone": brief review. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(1):18–21.

- Didari T, Mozaffari S, Nikfar S, et al. Effectiveness of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Updated systematic review with meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(10):3072–3084.

- Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG. Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):505–512.

- Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM. A novel delivery system of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(2):560–571.

- Lacy BE. Review article: an analysis of safety profiles of treatments for diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48(8):817–830.

- Page JG, Dirnberger GM. Treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome with Bentyl (dicyclomine hydrochloride). J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3(2):153–156.

- Hadley SK, Gaarder SM. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(12):2501–2506.

- US Food and Drug Administration. LOTRONEX (alosetron hydrochloride) tablets: risk evaluation and mitigation strategy [Internet]; 2016 [cited 2016 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/rems/Lotronex_2016-01-07_REMS_Document%20.pdf.

- Camilleri M, Northcutt AR, Kong S, et al. Efficacy and safety of alosetron in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9209):1035–1040.

- Camilleri M, Chey WY, Mayer EA, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist alosetron in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(14):1733–1740.

- Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, et al. Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(3):242–253.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Viberzi. Highlights of prescribing information [Internet]; 2020 [cited 2020 July 27]. Available from: https://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/viberzi_pi.

- Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):22–32.

- Schoenfeld P, Pimentel M, Chang L, et al. Safety and tolerability of rifaximin for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome without constipation: a pooled analysis of randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(10):1161–1168.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, et al. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):634–641.

- Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63(2):108–115.

- Nagarajan N, Morden A, Bischof D, et al. The role of fiber supplementation in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(9):1002–1010.

- De Giorgio R, Volta U, Gibson PR. Sensitivity to wheat, gluten and FODMAPs in IBS: facts or fiction? Gut. 2016;65(1):169–178.

- Werlang ME, Palmer WC, Lacy BE. Irritable bowel syndrome and dietary interventions. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2019;15(1):16–26.

- American Gastroenterological Association. Low-FODMAP diet [Internet]; 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/low-fodmap-diet.

- Schiller LR, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, et al. Mechanism of the antidiarrheal effect of loperamide. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(6):1475–1480.

- Barr W, Smith A. Acute diarrhea in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):180–189.

- Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(5):463–468.

- Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2566–2578.

- Cash BD. Emerging role of probiotics and antimicrobials in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(7):1405–1415.

- Brenner DM, Chey WD. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624: a novel probiotic for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2009;9(1):7–15.

- O'Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(3):541–551.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(10):1547–1561.

- Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1581–1590.

- Weerts ZZRM, Masclee AAM, Witteman BJM, et al. Efficacy and safety of peppermint oil in a randomized, double-blind trial of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):123–136.

- Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, et al. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation working team report. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1140–1171.e1.

- Camilleri M, Acosta A, Busciglio I, et al. Effect of colesevelam on faecal bile acids and bowel functions in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(5):438–448.

- Martínez-Vázquez MA, Vázquez-Elizondo G, González-González JA, et al. Effect of antispasmodic agents, alone or in combination, in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2012;77(2):82–90.

- Salix Pharmaceuticals Inc. Xifaxan. Highlights of prescribing information [Internet]; 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 6]. Available from: https://shared.salix.com/shared/pi/xifaxan550-pi.pdf.

- Lembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS, et al. Repeat treatment with rifaximin is safe and effective in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1113–1121.

- Pimentel M, Cash BD, Lembo A, et al. Repeat rifaximin for irritable bowel syndrome: no clinically significant changes in stool microbial antibiotic sensitivity. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(9):2455–2463.

- Black CJ, Burr NE, Camilleri M, et al. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies in patients with IBS with diarrhoea or mixed stool pattern: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2019;69(1):78–82.

- Sebela Pharmaceuticals. Lotronex. Highlights of prescribing information [Internet]; 2016 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://sebelapharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/lotronex-pi.pdf.

- Lembo T, Wright RA, Bagby B, et al. Alosetron controls bowel urgency and provides global symptom improvement in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(9):2662–2670.

- Garnock-Jones KP. Eluxadoline: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75(11):1305–1310.

- Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(1):17–44.

- Ananthan S. Opioid ligands with mixed mu/delta opioid receptor interactions: an emerging approach to novel analgesics. AAPS J. 2006;8(1):E118–E125.

- Wade PR, Palmer JM, McKenney S, et al. Modulation of gastrointestinal function by MuDelta, a mixed µ opioid receptor agonist/µ opioid receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(5):1111–1125.

- Abdelhamid EE, Sultana M, Portoghese PS, et al. Selective blockage of delta opioid receptors prevents the development of morphine tolerance and dependence in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258(1):299–303.

- Hughes PA, Castro J, Harrington AM, et al. Increased κ-opioid receptor expression and function during chronic visceral hypersensitivity. Gut. 2014;63(7):1199–1200.

- Brenner DM, Dove LS, Andrae DA, et al. Radar plots: a novel modality for displaying disparate data on the efficacy of eluxadoline for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(8):e13331.

- Lacy BE, Harris LA, Chang L, et al. Impact of patient and disease characteristics on the efficacy and safety of eluxadoline for IBS-D: a subgroup analysis of phase III trials. eCollection 2019 [Epub Ahead of Print]. 2019;12:1–12.

- Lacy BE, Chey WD, Cash BD, et al. Eluxadoline efficacy in IBS-D patients who report prior loperamide use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(6):924–932.

- Brenner DM, Gutman C, Jo E. Efficacy and safety of eluxadoline in IBS-D patients who report inadequate symptom control with prior loperamide use: a Phase 4, multicenter, multinational, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study (RELIEF). Poster presentation P0344: American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, October 5–10, 2018.

- Zhu L, Huang D, Shi L, et al. Intestinal symptoms and psychological factors jointly affect quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):49.

- Andrae DA, Patrick DL, Drossman DA, et al. Evaluation of the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) questionnaire in diarrheal-predominant irritable bowel syndrome patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:208.

- Abel JL, Carson RT, Andrae DA. The impact of treatment with eluxadoline on health-related quality of life among adult patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(2):369–377.

- Cash BD, Lacy BE, Schoenfeld PS, et al. Safety of eluxadoline in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):365–374.

- US Drug Enforcement Administration. Schedules of controlled substances: placement of eluxadoline into schedule IV. Notice of proposed rulemaking. Fed Regist. 2015;80(154):48044–48051.

- Levy-Cooperman N, McIntyre G, Bonifacio L, et al. Abuse potential and pharmacodynamic characteristics of oral and intranasal eluxadoline, a mixed μ- and κ-opioid receptor agonist and δ-opioid receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;359(3):471–481.

- Fant RV, Henningfield JE, Cash BD, et al. Eluxadoline demonstrates a lack of abuse potential in phase 2 and 3 studies of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(7):1021–1029.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA warns about increased risk of serious pancreatitis with irritable bowel drug Viberzi (eluxadoline) in patients without a gallbladder [Internet]; 2017 [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm546154.htm.

- Harinstein L, Wu E, Brinker A. Postmarketing cases of eluxadoline-associated pancreatitis in patients with or without a gallbladder. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(6):809–815.

- McLoughlin MT, Mitchell RM. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(47):6333–6343.

- Marbury TC, Berg JK, Dove LS, et al. Effect of hepatic impairment on eluxadoline pharmacokinetics. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(11):1454–1459.

- Levio S, Cash BD. The place of eluxadoline in the management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(9):715–725.

- Lacy BE. Diagnosis and treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:7–17.

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(suppl 1):S2–S26.

- World Gastroentrology Organisation. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines: irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective [Internet]; 2015 [cited 2020 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs-english.