Abstract

Background

Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency is a rare neurological condition, associated with a wide range of symptoms and functional issues, such as profound motor impairment and learning disability. Most individuals with AADC deficiency are completely dependent on their caregivers. This study explored the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted with caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency in Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United States. An interview guide was developed with input from clinical experts and caregivers and included questions on the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. Interviews were conducted by telephone/videoconference and were recorded and transcribed. Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

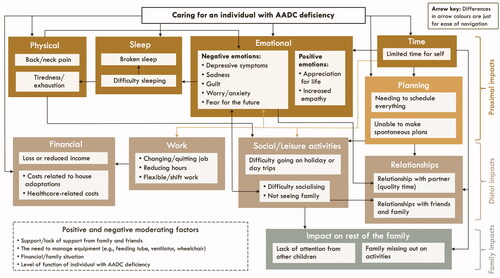

Fourteen caregivers took part who provided care to 13 individuals with AADC deficiency aged 1–15 years. Caregivers reported that their lives centred around the individual with AADC deficiency, due to their need for 24-hour care and regular healthcare appointments. They reported both proximal impacts (impact on time, planning, physical health and emotional wellbeing), and distal impacts (impact on social/leisure activities, relationships, work and finances). These concepts and relationships were illustrated in a conceptual model.

Conclusions

This is the first qualitative study to report on the experience of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. Caregivers reported that caring had a substantial multifaceted impact on their lives. These findings highlight the importance of considering the caregiver experience when evaluating the burden of AADC deficiency.

Introduction

Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency is a rare, autosomal recessive neurometabolic disorder that leads to impaired synthesis of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrineCitation1. The prevalence of AADC deficiency varies globally, with estimates reported at between 1:64,000 and 1:90,000 births in the USA, 1:116,000 in the European Union, 1:162,000 in Japan and 1:32,000 in TaiwanCitation2–4. Symptoms typically present during the first year of lifeCitation5, but diagnosis can be challenging due to the rarity of the disease and complex diagnostic testingCitation1. There are currently no licensed treatments specifically for AADC deficiencyCitation1,Citation6.

AADC deficiency is associated with a wide range of symptoms and functional issues, which can vary depending on the underlying genetical mutationCitation1. This can range from relatively “mild” (slight delay in developmental milestones, ambulatory without assistance, mild intellectual disability) to severe (no, or very few developmental milestones, non-ambulatory)Citation1. The majority of cases are classified as severe (80%), with 5% and 15% classified as mild and moderate, respectivelyCitation1,Citation7. Additional symptoms include hypotonia, oculogyric crises (upward deviation of the eyes lasting from seconds to hoursCitation8) mood and sleep disturbance, autonomic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, and eating difficultiesCitation1,Citation6,Citation9. There are no licensed treatments for AADC deficiency, but research has shown that gene therapy can improve the motor function of individuals with AADC deficiencyCitation7,Citation10,Citation11.

Due to the broad spectrum of symptoms and functional issues associated with AADC deficiency, most individuals require life-long careCitation1,Citation12. A survey of physicians and caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency (N = 63) found that 71% of individuals were completely dependent on their caregiverCitation9. Similarly, caregivers have reported needing to provide round the clock supervision and administration of medication, frequent hospital visits, inability to leave the house, loss of job, and sleep disruptionCitation13. Very little has been published on the lived experience of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency, but families with children with other chronic diseases have been shown to be at risk of reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL)Citation1. Understanding the extent of the tasks undertaken by caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency, and the impact this has on their lives, is crucial to understanding the full extent of the disease burden in this population. This information can be used to inform clinicians and regulators on the impact of the disease, as well as highlight the potential benefit of new treatments.

Qualitative research enables an in-depth exploration of the impact of a disease on patients and caregivers. It can provide insight into what it means to be a caregiver of an individual AADC deficiency, which may be difficult to fully appreciate without hearing it in their own words. This is particularly important in rare diseases, such as AADC deficiency, where little is known about the caregiver experience. This paper reports the findings of a qualitative study, which aimed to explore the impacts and challenges experienced by caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency. The specific focus was on caregivers of those treated with standard of care, rather than any disease modifying treatments, to ensure that the findings reflected the typical natural course of the disease.

Methods

Design and participants

This was a cross-sectional qualitative interview study with informal (unpaid) caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency in Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United States. The aim of the interviews was to explore the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. Participant inclusion criteria were: (i) being the main caregiver (providing at least 50% of caring responsibilities) of an individual with AADC deficiency, (ii) aged 18 years or over, (iii) live in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain or Portugal, (iv) willing and able to provide informed consent. In addition, a further inclusion criterion was for the individuals to have a confirmed diagnosis of AADC deficiency from at least two of the three tests: (1) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurotransmitter analysis, (2) molecular genetic testing of the DDC gene, (3) blood AADC enzyme activity. Caregivers of individuals who had been treated with gene therapy were excluded.

Study materials

A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the published literature, consultation with clinical experts (N = 3) and caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency (N = 2). The interview guide comprised mainly of open-ended questions to allow participants to speak freely about their experience. Questions were included on the impacts and challenges of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency (impacts on the individual were also explored, but are reported elsewhere).

A background questionnaire was developed to collect information on socio-demographics and the individual with AADC deficiency’s disease and treatment.

Ethics review and approval

This study was submitted for ethical review by the WIRB-Copernicus Group Independent Review Board and was granted an exemption (tracking number: #1-1327023-1).

Recruitment and interviews

Participants were recruited by a specialist recruitment agency using a variety of sources including social media, patient support groups and clinician referrals. Participants were sent an information sheet about the study and a background questionnaire, which they were asked complete and return by email. All interviews were conducted by telephone/videoconference in the local language for the study country. Verbal informed consent was taken before the interview, which then followed the semi-structured interview guide. Interviews lasted around an hour, were recorded and transcribed. Non-English language interviews were conducted by trained interviewers within the recruitment agency. These were translated into English for analysis.

Analyses

Data from the background questionnaire were summarised using descriptive statistics. Data from the interviews were analysed using thematic analysis in MAXQDACitation11, a software tool that assists with organising qualitative data, but does not automate any of the analysis process. Two researchers read all the transcripts and developed a coding framework based on the topics covered in the interview guide. One researcher then coded a sample of transcripts, which were reviewed by a second researcher and any discrepancies were discussed. The coding framework was revised following this discussion and the remaining transcripts were coded. Additional data-driven amendments were made to the coding framework throughout the coding process. The codes were then grouped into themes to describe the experience of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. A conceptual model was developed to illustrate the relationship between these themes.

Best practice in qualitative research is to keep conducting interviews until data saturation is reached. Data saturation has been defined as the point at which no new insights are obtained, or no new themes are identified in the dataCitation14. Saturation matrices were used to monitor the frequency of spontaneous and probed reports of concepts across the interviews, in which the concepts are presented in rows and the columns represent individual interviews in order of completionCitation15,Citation16.

Results

Sample characteristics

Fourteen interviews were conducted with caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency, including 10 mothers, two fathers, one brother and one aunt. Two caregivers were parents of the same individual. The caregiver characteristics are shown in and the characteristics of the individuals with AADC deficiency are shown in .

Table 1. Caregiver characteristics (N = 14)a.

Table 2. Characteristics of individuals with AADC deficiency (N = 13).

Caring activities

Caregivers commonly reported that their day was focused on providing constant care for the individual with AADC deficiency, including washing, dressing, feeding, and helping them with physiotherapy exercises. In addition to providing direct care, many caregivers reported conducting a range of administrative tasks associated with managing the individual’s condition, including administering medication, cleaning and setting up their equipment, and taking them to numerous medical appointments.

Constant care, two hours for this and three hours for that … there’s nothing that’s like “oh bath time, what fun”. No. It’s, it’s gruelling and it’s difficult and it takes twice as long as it did with the girls [her other children] and you know, maintaining the feeding tube, cleaning it, you know, mixing … it’s just all day long, it’s just … time. You know, getting to appointments when we can go. – participant 607 (caregiver to a 1 year old)

Those who cared for an individual who could walk independently, or with limited support, described the need to constantly monitor the individual in order to prevent accidents. Conversely, those who cared for an individual with more limited motor function reported providing additional physical care such as holding, manoeuvring and carrying the individual.

All caregivers stated that another caregiver was involved in caring for the individual with AADC deficiency. For most caregivers, this assistance was provided by their partner, but some caregivers also stated receiving help from their friends and wider family members (e.g. their parents).

My mother is very helpful, and she helps me manage my son. I have to say that friends and relatives help me a lot as well, and I also have the help of this person [government paid healthcare assistant]. – participant 203 (caregiver to a 10 year old)

A few caregivers reported that they receive support from government paid healthcare assistants at home. However, although some mentioned paying for care themselves in the past, none of the caregivers paid for a healthcare assistant at the time of the study.

Overview of caregiver impacts

Caregivers reported both proximal and distal impacts of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. Proximal impacts included lack of time and need to plan, as well as an impact on their emotional wellbeing, physical health and sleep. These were each reported as being direct impacts of caring for the individual with AADC deficiency. More distal impacts included an impact on their work, social and leisure activities, relationships and finances. These impacts and the relationships between them are described in more detail below and are shown in a conceptual model in . The saturation matrices indicated that saturation had been reached for the broad overarching themes, with no new impacts emerging, after five interviews ().

Figure 1. Conceptual model on the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. The conceptual model is designed to be read from the top, where there are the most proximal impacts, to the bottom, where there are more distal impacts. The arrows show the relationships between the concepts, which are either unidirectional or bidirectional (for example, difficulty socialising/not seeing family was found to impact on negative emotions and vice versa). Some relationships are between the larger external boxes, for example, time-related impacts were reported to impact on emotional wellbeing, work and social/leisure activities. Other relationships are between the internal boxes (e.g. sleeping difficulty impacts broken sleep).

Table 3. Data saturation matrix for caregiver impacts.

Proximal impacts

Time and planning related impacts

All caregivers described how caring for an individual with AADC deficiency took up a substantial amount of their time and that this left little time for doing anything else.

I don’t have the time I used to have. [When] my [other] kids used to go to school, I used to do the grocery shopping, I used to love cooking. I used to have me time – participant 601 (caregiver to a 6 year old)

One caregiver reported that they even neglected their health because of their lack of time.

[I] don’t even [go] to gynaecological check-ups … I have not even been to a check-up, I have not been to the dentist, that I had to go – participant 401 (caregiver to a 3 year old)

Many caregivers stated that they looked forward to even the simplest tasks that they could do by themselves, such as going food shopping or to the hairdressers, as these were the few occasions when they were able to gain respite from their caring duties. Some described how they needed to plan their time very carefully and stick to a tight schedule in order to fit in all of their responsibilities.

Every day, having to anticipate everything, I always have to plan everything, I have to go to the supermarket and so on, my life is schedule[d] minute by minute. I have to plan things, I cannot miss one hour, I sometimes panic, I get paranoid, because I have to do this and that. – participant 204 (caregiver to an 8 year old)

The requirement to stick to a rigid schedule made it difficult for caregivers to make spontaneous plans. One caregiver described how this lack of spontaneity had the largest impact on their quality of life.

The biggest impact has been that lack of spontaneity and having to have a schedule and not being able just to go up and take off – participant 606 (caregiver to a 4 year old)

Impact on emotional wellbeing

All caregivers reported that caring for an individual with AADC deficiency had a substantial impact on their emotional wellbeing. Some caregivers described how their caring responsibilities had a greater impact on their mental health than their physical health, due to the mental tiredness from having to manage their numerous caring responsibilities.

I think that the mental aspect of being tired and doing the things that I need to do and keeping track of everything, and then also the fear of the future. Those weigh down on me the most – participant 603 (caregiver to a 7 year old)

Another commonly reported emotional impact was sadness, which was described as a consequence of watching the individual suffer, or a grief for the loss of an imagined future.

My son and I are living a life, that, he doesn’t understand it, but I’m living a life that I did not want for him and I. I wanted a different life – participant 201 (caregiver to a 15 year old)

In relation to this, several caregivers expressed anxiety and worry about the individual’s uncertain future or explained how they felt anxious about the individual when they were not with them, for example, when they were with their partner or at school.

I’m scared something could happen, I’m not ready to help him if something happens, I’m anxious also when he is at school when he is not under my eyes … I’m anxious also when he is with my husband because I constantly look at my watch, always obsessed by time – participant 204 (caregiver to an 8 year old)

Some caregivers reported experiencing depressive symptoms and saw a counsellor or therapist to help them cope.

I do see a counsellor just for my own mental well-being of my mind and, you know, getting out my frustrations – participant 601 (caregiver to a 6 year old)

Despite the difficult circumstances, several caregivers stated that they try to maintain a positive outlook of their life. For example, one described how caring for the individual with AADC deficiency had helped them to understand the value of life and be grateful for what they have.

Impact on physical health

Several caregivers reported that caring for the individual impacted their physical health. For example, some reported that they experienced back and neck pain from lifting and carrying the individual. Others described how they felt drained and exhausted from their caring responsibilities. This included both physical exhaustion from performing physical care activities (e.g. lifting, carrying and cleaning equipment), and mental exhaustion from having to plan everything in advance and constantly monitor the individual.

Time, energy, never being able to be away, or rest [are the main challenges]. Um, having to mentally be aware as well as physically – participant 602 (caregiver to a 4 year old)

Impact on sleep

Several caregivers mentioned that caring impacted their sleep, for example, broken sleep because they needed to continuously check on the individual throughout the night.

I check … the breathing machine is working and that it’s not turned off. That she hasn’t unplugged it or shifted it or pulled it away from her nose. I know that I’m not getting a full great night’s sleep, every single night. – participant 604 (caregiver to a 1 year old)

Others reported difficulty falling asleep due to anxiety and worry, for example, about whether the individual would stop breathing during the night.

Distal impacts

Impact on social and leisure activities

Several caregivers reported that their social and leisure activities were limited because of their caring responsibilities. For example, it was described how they were unable to play sport or exercise, or go to the cinema or out for dinner with their friends.

We cannot go to a party. If there is a party, we cannot go. Basically, we live an isolated life – participant 301 (caregiver to a 15 year old)

One caregiver reported having to leave social occasions early due to the individual with AADC deficiency being in discomfort.

I even go out to the park [with my daughter] and talk to a neighbour, we spend [no] more than 5 minutes talking … and she quickly … she constantly gets desperate … [so] the social life has moved to, well, not as much recently. – participant 401 (caregiver to a 3 year old)

Others reported that they had to adapt their social activities around the individual with AADC deficiency, for example, by hosting friends and family at home.

We are still able to have social lives, our son either comes with us or we have people over – participant 603 (caregiver to a 7 year old)

One caregiver mentioned that they generally avoided social events as they were aften too emotionally and physically exhausted from caring for the individual with AADC deficiency.

Gosh yes, those things [social events] have been impacted. I don’t have time. And honestly, I don’t have energy. If I get any time, I want to just, I kind of want to just be alone. – participant 602 (caregiver to a 4 year old)

A few caregivers explained how they avoided seeing other family members (e.g. their parents) as they did not want to burden them.

Impact on relationships

Several caregivers reported that their caring responsibilities had an impact on their relationships with others, including their partner, family and friends.

I wasn’t doing fine psychologically, we [self and partner] were quite distant both at a physical level and we weren’t talking much, we were not on the same track. Let’s say that my concern was not any more a husband and a marriage, I was concentrating on other things – participant 204 (caregiver to an 8 year old)

In addition, some caregivers described how they had lost friendships as a consequence of not being able to leave the individual in order to go out and socialise.

My social relationships, seeing people [is impacted] … but then it’s not that life is excluded [when you have a healthy child], you keep your friendships even if you are a parent, mostly at a certain age, when they have fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, eighteen years old … but you can leave them alone and in the evening you can go to the pizzeria with some friends. – participant 201 (caregiver to a 15 year old)

On the positive side, some caregivers discussed some of the ways in which their family and friends had been supportive. Others described how caring for the individual with AADC deficiency had made them more compassionate and strengthened their relationship with their partner and other family members.

We have a good relationship, in the sense that this thing has tied us strongly. And anyhow, we share this thing, so it did not have a negative impact on our relationship – participant 203 (caregiver to a 10 year old)

Impact on work

Most caregivers reported that they had needed to make changes to their work, including reducing their hours, changing jobs or stopping working altogether.

I had to quit my job and stay at home to care for her because I wanted her to have [a good] quality of life. I stopped being … poor me, I stopped earning money, I stayed at home – participant 301 (caregiver to a 15 year old)

Others described how they would like to go back to work if they could.

I would give up everything in my life for my child, but there have been times where I would love to go back to work and I know that that’s not an option for me – participant 603 (caregiver to a 7 year old)

Some caregivers said their work was not impacted because they were already stay at home parents before they had to take on these caring responsibilities.

Impact on finances

Some mentioned that their finances were impacted as a result of being a caregiver for an individual with AADC deficiency. Direct costs included medical tests, treatments and medical insurance. Indirect costs included those associated with adapting their home or care to make it more accessible to the individual with AADC deficiency.

I had to move house. I lived in a house with stairs. I came to a housing district, which is not easy at all, because I also lost my income. We had to adapt the bathroom, we had some work done – participant 301 (caregiver to a 15 year old)

Impact on family

Although not the focus of this study, most caregivers described how living with AADC deficiency impacted the whole family, and that their daily lives were centred around the individual with the condition. In particular, several caregivers mentioned experiencing difficulty going on day trips or holidays as a family. Several barriers were reported to planning these occasions, such as the need for there to be a nearby hospital and to have both parents present.

Everything is complicated, you cannot go where you wish to go, because, you have to learn first is [whether] where you are going there is a hospital, where they know how to treat him if he doesn’t feel well – participant 201 (caregiver to a 15 year old)

Some caregivers took steps to ensure that their other children did not miss out. For example, some reported that their partner or other family members would take the other children out, so they could socialise or have their own hobbies.

Moderating factors

The proximal and distal impacts were influenced by a range of positive and negative moderating factors. For example, caregivers with support from their family or friends found it easier to manage the individual’s AADC deficiency, compared with those who did not have such support. Their financial/family situation also had a moderating effect, for example, those who were already stay at home parents or who were better off financially were less impacted than those who had needed to give up work. These individuals were also in the position to move to a new house or change their car which may have alleviated some of the physical burden associated with caring for the individual. This may have created more space for wheelchair access and equipment to help lift the individual in the bathroom.

The level of function of the individual with AADC deficiency and their need for equipment (e.g. feeding tube and ventilator) also had a moderating effect. For example, while the use of a feeding tube made it easier for them to manage the individual’s dietary intake, it also added to their time burden because they needed to set up and clean the equipment. The individual’s level of motor function was also a moderating factor, as while those with some motor function (e.g. able to walk) were less limited, they also required more supervision from their caregiver.

Discussion

This is the first qualitative study to explore the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency and to develop a conceptual model illustrating the relationship between these various caregiver impacts. We found that caregivers spent a substantial amount of time caring for the individual with AADC deficiency and that their caring activities were associated with a range of proximal and distal impacts. Proximal impacts that were reported included time-related, planning, emotional, physical and sleep impacts. These impacts were, in turn, reported to have a wide-ranging effect on the lives of the caregivers, including on their work, social and leisure activities, relationships and finances. All caregivers also stated that another caregiver (e.g. their partner or parent) was involved in the care.

These qualitative findings highlight the substantial burden of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency and the significant unmet needs of caregivers. These insights are important as it is not possible to fully conceptualise the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency, or any rare neurodevelopmental disorder, without speaking to caregivers directly. Although it has been documented that individuals with AADC deficiency require support with all aspects of their daily livesCitation12, and that this can impact their caregivers’ jobs and sleepCitation9,Citation10, this is the first study to provide rich contextual information on what it means to be a caregiver in their own words. The findings have enabled a nuanced understanding about how the caregiver burden may differ depending on a number of moderating factors, such as the caregiver’s financial/living situation, the availability of support from friends and family and the level of functioning of the individual with AADC deficiency. For instance, more time was reported to be required caring for individuals who used feeding tubes (i.e. due limited head control) because of the need to set-up and clean this equipment.

The conceptual model extends these findings by showing further how the reported proximal and distal impacts relate to each other, demonstrating how burden in one area of life may impact other areas. For instance, caregiver’s lack of time was reported to impact on their ability to work and take part in social and leisure activities and these limitations were, in turn, described to impact on their emotional wellbeing. The relationships shown in the conceptual model can highlight the potential impact of a treatment, as an improvement in one area may lead to an improvement in other areas. For instance, if a treatment can improve an individual’s level of functioning, they may need less help with manoeuvring, which may therefore lead to the caregiver carrying out fewer physical activities and reducing their likelihood for back pain. The conceptual model provides a useful tool for identifying concepts that may be important to measure quantitatively when considering the benefits of a treatment. It can also be used as a tool in clinical practice to facilitate communication between healthcare providers and caregivers on the impact of AADC deficiency and the potential benefits of treatments.

While this study provides novel insights, it also has some limitations which should be acknowledged. Participants were sought from countries across Europe and North America, but the majority of participants were recruited from the United States and Italy. However, as AADC deficiency is an extremely rare disease, recruitment relies on a limited pool of individuals agreeing to take part. Our data saturation matrices indicated that data saturation was reached, but it is still possible that the findings may vary in different populations. For instance, although qualitative research is not designed to be representative, the sample were predominantly White and university educated. It also included some parents who were already full-time homemakers before they took on the responsibility of caring for someone with AADC deficiency, which may have influenced the transferability of the findings.

Despite these limitations, this is the first qualitative study to provide an in-depth exploration of the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency. Although it was not intended to be the focus of the interview guide, this study additionally provided insights about the impacts of AADC deficiency on the whole family (e.g. impacts on other children). Future research could extend this qualitative study by exploring the broader impact on the family, as well as evaluating the caregiver burden quantitatively. In addition, future research could explore the experience of caregivers of individuals with different levels of severity of disease (mild, moderate and severe phenotypes).

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative study to illustrate the depth and breadth of impact of AADC deficiency on the lives of caregivers from their own perspective and using their own words. The findings provide a valuable education tool and voice piece for the AADC deficiency community. They may be used to inform clinicians, regulators, and biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies working in this area on the substantial unmet need in this population, as well as provide insights into concepts that could be measured in clinical trials for new treatments.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by PTC Therapeutics International Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

HS, KW and SA are employees of Acaster Lloyd Consulting Ltd. CW, SO and KB are employees of PTC Therapeutics. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. The study materials were developed by HS, KW and SA and all authors provided feedback. The English language interviews were conducted by HS and KW. The analysis was conducted by HS and KW and the conceptual model was developed by HS, KW and SA. HS drafted the manuscript and all authors provided feedback. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the caregivers who took part in the study.

References

- Wassenberg T, Molero-Luis M, Jeltsch K, et al. Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):12.

- Whitehead N, Schu M, Erickson SW, et al. Estimated prevalence of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency in the United States, European Union, and Japan. Poster sesion presented at: Annual Congress of the European Society Gene and Cell Therapy. 2018 Oct 16–19. Lausanne.

- Hyland K, Reott M. Prevalence of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in at-risk populations. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;106:38–42.

- Chien YH, Chen PW, Lee NC, et al. 3-O-methyldopa levels in newborns: result of newborn screening for aromatic L-amino-acid decarboxylase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;118(4):259–263.

- Brun L, Ngu LH, Keng WT, et al. Clinical and biochemical features of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neurology. 2010;75(1):64–71.

- Fusco C, Leuzzi V, Striano P, et al. Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: results from an Italian modified Delphi consensus. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47(1):13.

- Kojima K, Nakajima T, Taga N, et al. Gene therapy improves motor and mental function of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain. 2019;142(2):322–333.

- Barow E, Schneider SA, Bhatia KP, et al. Oculogyric crises: etiology, pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;36:3–9.

- Pearson TS, Gilbert L, Opladen T, et al. AADC deficiency from infancy to adulthood: symptoms and developmental outcome in an international cohort of 63 patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020;43(5):1121–1130.

- Chien YH, Lee NC, Tseng SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of AAV2 gene therapy in children with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: an open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1(4):265–273.

- Hwu WL, Muramatsu SI, Tseng SH, et al. Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(134):134ra61.

- Williams K, Skrobanski H, Werner C, et al. Symptoms and impact of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: a qualitative study and the development of a patient-centred conceptual model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(8):1353–1361.

- Hanbury A, Smith AB, Buesch K. Deriving vignettes for the rare disease AADC deficiency using parent, caregiver and clinician interviews to evaluate the impact on health-related quality of life. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2021;12:1–12.

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020. Software. 2019. maxqda.com.

- Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Res. 2008;8(1):137–152.

- Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269–281.