Abstract

Background

Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) were developed as an alternative to warfarin to treat and prevent thromboembolism, including stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients. The COVID-19 pandemic could increase the risk of stroke and/or the risk of bleeding in patients due to nonadherence or sub/supra-optimal dosing.

Objective

To investigate DOAC prescription trends in England’s community settings during the complete first wave of COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Descriptive and interrupted time series (ITS) analyses were conducted to examine the prescription patterns of DOACs (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban) and warfarin for primary care patients in the English Prescribing Dataset from January 2019 to February 2021, with March 2020 as the cut-off point.

Results

A 19% increase in mean DOAC’s accompanied with 20% warfarin prescriptions decline was observed. ITS modelling showed an increase in DOAC prescription volume in March 2020 (+7 million items, p = 0.008). The pre-existing upward trend in DOAC prescriptions slowed during the period (-427,000 items, p = 0.007). Apixaban was the most frequently used DOAC and had the largest step-change in March 2020 (+5 million items, p = 0.010). The mean monthly combined cost of DOACs and warfarin was higher during the period. DOAC prescription trends were consistent across England’s regions. Conclusion: The overall oral anticoagulants use in this period was lower than expected, indicating a medical needs gap, possibly due to adherence issues. The potential clinical and logistical consequences warrant further study to identify contributing factors and mitigate avoidable risks.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), stroke is the second leading cause of death globally in 2019 behind ischaemic heart disease [Citation1]. Thrombotic events, such as stroke, are prevented and treated with traditional oral anticoagulants like vitamin K antagonists, primarily warfarin, acting as benchmark therapy [Citation2]. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) developed since 2011 overcome inconveniences related to warfarin [Citation3]. DOACs have predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics that allow for the use of a fixed dose, eliminating the warfarin linked burden of frequent international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring [Citation4]. DOACs also have fewer drug and dietary interactions. However, challenges for successful anticoagulation therapy using DOACs, both medically (e.g. deteriorating renal function; hepatic disease including patients with moderate to severe cirrhosis) and in application (e.g. patient adherence) remain [Citation5–7]. There are four licensed DOACs in the UK, a direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, and three inhibitors of activated factor X, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban [Citation8–11]. These medicines are indicated for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation to prevent stroke or systemic embolism [Citation8–12]. DOACs have at least comparable efficacy to warfarin and the advantage of reduced incidences of intracranial bleeding [Citation13–18].

The Coronavirus pandemic [Citation19], has affected healthcare systems globally. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a national clinical guideline in managing anticoagulation services during the pandemic [Citation20], recommending the use of DOACs instead of warfarin for patients requiring oral anticoagulation therapy and to consider switching those patients already on warfarin to DOACs where clinically appropriate. These measures sought to minimise the burden of monitoring and reduce the requirement for physical attendance in healthcare facilities to limit COVID-19 exposure and better manage care services.

Compared to other acute infections, there is a higher incidence of thromboembolic events in hospitalised COVID-19 patients, particularly in those admitted to the intensive care unit [Citation21–23]. In this setting, DOACs are typically preferred for extended post-discharge VTE prophylaxis (when clinically indicated) over warfarin, low-molecular-weight-heparin and unfractionated heparin [Citation24–27]. Blood coagulation and fibrinolysis are greatly activated based on the strategy of the different infectious agents which exploit the excess of response of both systems to achieve the greatest possible virulence. These are valuable concepts in planning therapeutic interventions in the different infectious diseases where anti-thrombotic and anti-fibrinolytic drugs could be of help in contrasting the course of these diseases characterized by a high mortality rate [Citation28].

There are reports of rare thrombotic incidents as a side effect of the vaccines, particularly the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine (Vaxzevria®), which could require the use of anticoagulants such as DOACs [Citation29,Citation30]. The Expert Haematology Panel guidelines from the British Society for Haematology, recommend the use of non-heparin-based therapies (including DOACs) for the treatment of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 vaccine–induced thrombosis [Citation31]. As the reported thromboembolic events were accompanied by thrombocytopenia, DOACs were also recommended for prophylaxis of thrombotic events when thrombocytopenia was present after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. However, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is not used when the platelet count is severely reduced (below 30 × 109/L), but in practice this applies to DOACs as well as this being a practical rule of thumb [Citation32].

Another clinical concern associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the lockdowns and containment measures, was access to medication and adherence to therapies. Adequate adherence to therapeutic regimens determines therapeutics effectiveness and is associated with better clinical and economic outcomes [Citation33,Citation34]. A study evaluating patients’ adherence to long-term medications during the pandemic was conducted in Italy, where a trend of increased failure to refill prescriptions for select medicines was observed [Citation35]. Although adherence to DOACs during the pandemic has not been studied, it is understood to be crucial to achieve successful outcomes and reduce harm [Citation5,Citation36].

Primary objectives are to compare DOAC and warfarin prescription trends before and after the pandemic’s onset in England as a proxy for adherence. Secondary objectives included studying the related costs and regional differences within England.

Methods

Study design

This is an observational study using an interrupted time series (ITS) design to detect whether DOAC prescription patterns during the pandemic differed from their underlying trends. ITS is a robust design to investigate the impact of an intervention at a population-level, accounting for pre-existing trends [Citation37,Citation38]. Detailed methods have been previously published [Citation39]. The ITS tutorial by Bernal et al. and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care ITS resource were used in this study [Citation40,Citation41]. Monthly total number of prescribed and dispensed DOACs and warfarin items were collected over the study period (January 2019–February 2021). March 2020 was used as the cut-point (when pandemic was declared by the WHO and lockdown and major containment measures were initiated in England) [Citation19,Citation42].

Data source

The publicly available English Prescribing Dataset (EPD) was used as the data source for this study [Citation43]. EPD provides comprehensive information on England’s community-issued prescriptions per month. EPD includes all prescribed and dispensed items, their quantity and cost, and practice name. EPD excludes prescriptions issued outside of England, does not provide patient identification, non-dispensed or returned items, items prescribed and dispensed in hospitals or prisons and private prescriptions.

The prescription data (total quantity of prescribed and dispensed items, total cost and regional office name) of the four DOACs (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban) and warfarin for each month were downloaded from the EPD as comma-separated values (CSV) files. Data from January 2019 until February 2021 (the last available month in the dataset at the time of data extraction) were collected. Medications were identified by their British National Formulary (BNF) codes (dabigatran: 0208020 × 0, rivaroxaban: 0208020Y0, apixaban: 0208020Z0, edoxaban: 0208020AA and warfarin: 0208020V0). All warfarin and aggregated DOAC prescription data were stratified according to England’s National Health Service (NHS) regions to observe regional prescription patterns.

Statistical analysis

Both descriptive and ITS analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS® statistics v26.0. Temporal trends in the prescriptions (total quantity of items) were graphically inspected before performing the ITS analysis, with the assumption that pre-COVID-19 trends would have continued unchanged in the absence of the pandemic. ITS analysis was performed using an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model [Citation43,Citation44]. This controls potential bias such as autocorrelation and seasonality [Citation38,Citation45]. To allow for short-term serial correlations, the model added an autoregressive one-month lag to reflect routine primary-care practice of dispensing a prescription up to a month later (See S1 Syntax).

The pandemic’s impact can be described by a range of effect estimates, referred to as impact models, such as a level change, slope change (i.e. trend change) or both [Citation40]. The level change represents an abrupt effect of the pandemic, while the slope change suggests a gradient change in the outcome value (prescription volume) [Citation37]. Regression coefficients estimates were obtained for both effects (level and trend change). Confidence intervals of the estimated effect were calculated based on the effect estimates and the standard error (SE). The model estimates were reported at a 95% confidence level, with p < 0.05 (5%) considered significant.

Ethical considerations

This was secondary analysis of government published data under the open government licence version 2.0 [Citation46]; it did not contain patient identifiable data; therefore, approval was not necessary. However, this study was conducted in line with the declaration of Helsinki [Citation47].

Reporting guideline

To support the reporting of this study, the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data (RECORD) checklist was used (See S5) [Citation48].

Results

Prescription data from 26 consecutive months were analysed, with 14 time points before the pandemic and 12 time points after its onset (March 2020 cut-off point). Sensitivity analysis is presented in S2.

Total quantity of medications

Descriptive statistics are presented in and show a 19% increase in the mean DOAC prescription volume after the pandemic’s onset (40 million items before versus 48 million items after), accompanied by a 20% decline in mean warfarin prescriptions (30 million items before versus 24 million items after the pandemic’s onset). Of the four DOACs, apixaban was the most frequently used followed by rivaroxaban, while dabigatran and edoxaban made relatively minor constituents. However, the variation in the mean prescription volume for each DOAC during the pandemic followed a different pattern. Specifically, there were 92%, 8% and 20% increases in edoxaban, rivaroxaban and apixaban prescriptions, respectively, and a 6% decrease in dabigatran prescriptions. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a significant difference for the mean prescription volumes for all the medications (p < 0.05) between the pre- (January 2019 to February 2020) and post-pandemic (March 2020 to February 2021) time points.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (in thousands) of the monthly total quantity of prescribed medications; standard deviation (STD), confidence interval (CI).

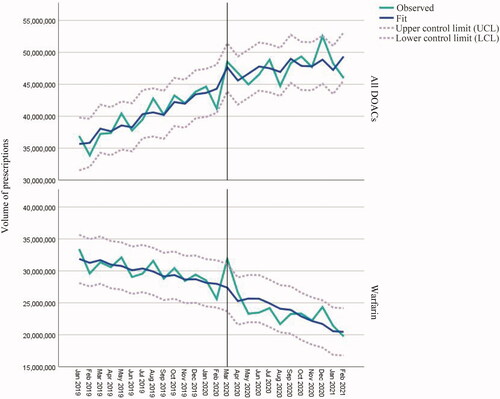

Interrupted time series

and summarises the volume of DOAC prescriptions, which were steadily growing before the pandemic (687,000 items/month, p < 0.001), with a level change of approximately 7 million items in March 2020 (p = 0.008). While this upward trend continued during the pandemic, it was at a much lower rate (-427,000 items, p = 0.007) with a wide confidence interval, suggesting that those patients who were stabilised on DOACs before the pandemic, may not be taking them as intended, not accounting for newly switched patients. In contrast, warfarin’s prescription volume was on a downward trend before the pandemic (-297,000 items/month, p = 0.008), which decelerated during the pandemic, but not statistically significantly. However, there was a non-significant (p = 0.242), step-change in warfarin prescriptions at the intervention time (+3 million items).

Figure 1. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model with one-month autocorrelation (1,0,0)(0,0,0) for the prescribed medications.

Table 2. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model (1,0,0)(0,0,0) parameters for estimated prescription volume change; t-statistic (t-stat), confidence interval (CI) *Calculated as the sum of the pre-intervention slope and pre- and post-slope difference [Citation41].

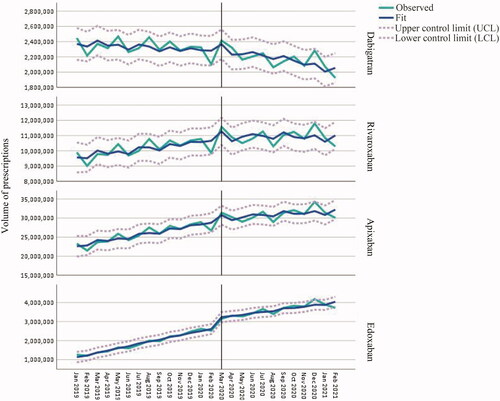

and provides the ARIMA model summary of the four DOACs. Apixaban showed the greatest level change in March 2020 (+5 million items, p = 0.010) and dabigatran the lowest (p = 0.074). Unlike other DOACs, dabigatran had a downward trend before and after the pandemic indicating its waning popularity. As the pandemic progressed, rivaroxaban showed the slowest growth in prescription rates compared to apixaban and edoxaban (5,000, 200,000 and 75,000 items/month, respectively), with the latter two representing the major contributors to the DOAC model.

Figure 2. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model with one-month autocorrelation (1,0,0)(0,0,0) for each DOAC.

Seasonality was not expected to influence the model trends during the pandemic as these medicines are long-term medicines that are not normally discontinued after a patient has been stabilised on therapy. Primary care practices continued to provide healthcare services, and scheduled appointments were kept, although most services were moved online [Citation49]. Moreover, since DOACs are prescribed for long-term conditions, patients had online access to repeat prescription service [Citation50]. Nevertheless, a high DOAC prescription volume was noted in December 2020 as seen in and and in S3 Aggregated data.

Total cost of medications

The total cost of DOACs increased in step with the increment in the prescription volume (See ), while the total cost of warfarin decreased in line with lower prescriptions (See S3 Aggregated data).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the total monthly cost (in thousands) in pound sterling (£, GBP) of the prescribed medications; confidence interval (CI).

Since DOAC unit prices are higher, the net change in total cost (the change between the mean monthly cost of DOACs and warfarin before and after the pandemic) increased by 19%.

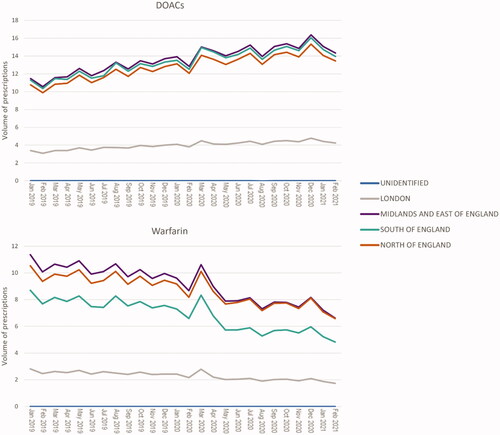

Regional variations

Aggregated data across England’s main regions were analysed over the study period. EPD regional-labelling was updated by the data controller after April 2020 [Citation43] but was transparent enough to allow this analysis. The aggregated regions include London, the Midlands and East of England, South of England (South-East + South-West), North of England (North-East + North-West + Yorkshire) and few unidentified records.

During the pandemic, variations in DOAC and warfarin prescription volumes were consistent across the regions (). Generally, a slightly greater total quantity of warfarin was prescribed in the Midlands and East of England. In contrast, all regions prescribed DOACs in similar proportions, except London. There were some regional variations between DOAC prescriptions, with dabigatran and rivaroxaban dominating in the South of England and edoxaban in the Midlands and East of England, while apixaban prescriptions were consistent across the regions (see S4 Regional).

Discussion

Findings describe oral anticoagulant prescribing patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. We observed immediate (level) and sustainable (slope) changes in prescription volume during the pandemic. Although there was a significant rise in the total number of DOACs prescribed at the onset of the pandemic, the sustained growth rate was marginal compared to the trend before the pandemic. Nevertheless, this increase is accompanied with the decelerating use of warfarin during the pandemic. This provides evidence of ‘switching’ as per the urgently issued NICE guidelines [Citation20] in the early phase of the pandemic, with patients on warfarin before the pandemic being switched to newer DOACs, reducing warfarin-related follow-up for INR monitoring. This relates to the NHS's policy that came out immediately in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and was directly consequent to the pandemic. As a result, there was nationwide switching in addition to the longstanding trend over which warfarin has been substituted with DOACs. However, the overall increases in anticoagulant use were modest and lower than expected. It could be that multiple-tablet warfarin daily dosage [e.g. 0.5 mg (white), 1 mg (light brown), 3 mg (blue), and 5 mg (pink)] was consolidated into a single DOAC tablet. However, this is not a satisfying explanation as few patients take multiple warfarin tablets daily. A more rational explanation would suggest a lack of adherence to anticoagulants during the study period, which suggests a potentially growing, unmet medical need of patients who need anticoagulation therapy, but not receiving it. Particularly vulnerable to this effect would be newly diagnosed or recently initiated anticoagulant patients during the pandemic. Anecdotal evidence suggests switching was only considered for complex or poorly controlled patients on warfarin (requiring more frequent INR monitoring). For long-stabilised warfarin users, INR monitoring intervals were extended and or home testing considered [Citation20]. This introduces the potential risk of variability in standard of care and inconsistent patient care, which might lead to variable patient outcomes.

Other considerations include access to medication and prescriptions in a timely manner, or lack thereof. Failed prescription refills for chronic conditions have been reported in Italy during 2020 [Citation35]. Low adherence to DOACs is a known phenomenon and reported in several studies between 2017- 2020 prior to the pandemic [Citation7,Citation51–54]. Although this cannot be the sole explanation behind the deceleration in DOAC prescriptions, it is likely a major contributor. Adherence may be a greater concern for DOACs than warfarin due to their shorter half-lives (t½: 20–60, 12–14, 5–13, ∼12 and 10–14 h for warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban, respectively); thus, missing a scheduled DOAC dose could rapidly diminish anticoagulation effects with greater risk of negative patient outcomes [Citation4,Citation55]. Nonadherence can lead to several clinical and cost consequences [Citation33,Citation36] with escalating disease aetiology, risk of complications, and patient harm.

An OpenSafely study reported a small but substantial number of patients who were prescribed warfarin and DOACs simultaneously in the early phase of the pandemic [Citation56]. The co-prescribing practice could predispose the patients to serious adverse events, including bleeding. Additionally, some switches were made via telephone consultations [Citation57], where patients’ retention of information, level of adherence and compliance with instructions and advice may not be comparable to face-to-face consultations. Therefore, multiple telephone sessions may be required to follow-up on patients’ understanding and current medication use behaviour. It is also important to note that not all patients are eligible for switching to DOACs (such as patients with a prosthetic mechanical heart valve, antiphospholipid syndrome, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, severe renal impairment [e.g. creatinine clearance less than 15 mL/min and less than 30 mL/min with dabigatran [Citation58]], active malignancy or chemotherapy [unless advised by a specialist], on strong cytochrome P-450 CYP3A4 inducers [e.g. phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbitone or rifampicin]); therefore, guidance for safe switching should be followed [Citation20]. Additionally, the sudden and substantial increase in demand for DOACs arising from the switching practice could threaten the pharmaceutical supply chain and lead to cost constraints. We found that the mean monthly net costs of anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) were higher during the pandemic.

It is acknowledged that DOACs could be initiated for patients with active cancer as per recommendations from the American Society of Haematology 2021 guidelines [Citation59], however, the UK's guidelines [Citation20] recommended that patients with active cancer should not be considered for switching from warfarin to DOACs unless advised by a specialist. Many patients with cancer have a hypercoagulable state and an increased risk of developing VTE, arterial occlusion, and pulmonary emboli. Patients with cancer may also have an increased risk of bleeding with anticoagulant treatment. DOACs were noninferior to dalteparin in preventing VTE recurrence in patients with cancer without a significantly increased risk of major bleeding. However, DOACs were associated with higher rates of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding compared with dalteparin, primarily in patients with gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies [Citation60].

Although major bleeding risks are lower with DOACs than warfarin, there are concerns about increased GI bleeding risks [Citation14–16] The sudden spike in DOAC prescription volumes during the pandemic may, therefore, necessitates attention. A UK-based, longitudinal study reported a 0.8% increase in emergency admissions for bleeding incidents for every 10% increase in DOAC prescriptions between 2011 and 2016 [Citation61]. Recently, a new study reported higher GI bleeding rates with rivaroxaban than apixaban and dabigatran, explained by its once-daily dosing and higher peak levels, which could be a consideration when choosing among DOACs [Citation62]. This could also be concerning for the ‘south of England’ region, where rivaroxaban dominates the prescribed DOACs. It is also important to note that edoxaban has no specific reversal agent for emergency bleeding [Citation63], which could be a concern in the ‘Midlands and East of England’ where edoxaban is the most prescribed DOAC. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has recently published a drug safety update reminding healthcare professionals of the risk of bleeding complications associated with DOACs [Citation63]. This was precipitated by frequent reports of DOAC-induced bleeding in the UK, particularly in patients with underlying conditions that increase their bleeding risk, such as renal impairment and older age.

Recently, the COVID-19 vaccine has been reported to induce thromboembolic events [Citation29]. Although rare, this side effect could necessitate the use of DOACs for the treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19 vaccine–related thrombosis, as recommended by a recent national guideline [Citation31]. It also shows that in practice, at least, the guidance is largely a ‘theoretical’ science rather than delivered with a wider practice-evidence base or research. It seems that clinicians are either not convinced of the science, do not have sufficient opportunities to initiate the switch or other (as yet) unknown adverse effects that are appearing precluding DOAC use, amongst other possibilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic can further exacerbate the previously discussed concerns. For example, there is a notable decline in emergency department attendance, hospital admissions (including for stroke) and the use of primary care services [Citation64–66], which suggests these patients’ reluctance to attend healthcare facilities. We know that time-dependent care for stroke can dictate life-outcomes. Despite the increase in urgent care calls to the NHS and emergency calls to ambulance services in England [Citation64,Citation67], the massive increase was only seen in March 2020; therefore, there is still a possible chance that patients’ need for prompt help may have been compromised by the avoidance of medical health facilities. In addition, healthcare services have become largely virtual during the pandemic [Citation49]. While this may enhance the continuity of care, sudden changes to the routine provision of healthcare require behavioural adaptations. Behaviours of adherence may not have kept pace with many variables changes to routine, such as digital access, technology literacy, technical support, educational level, internet connectivity and age or frailty [Citation68].

This study found apixaban to be the most frequently prescribed DOAC, followed by rivaroxaban. However, both apixaban and edoxaban were favoured during the pandemic, in agreement with findings from an OpenSafely study and King’s College Hospital Foundation NHS Trust experience concerning switching patients from warfarin during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation57]. In May 2020, NHS England strongly encouraged Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to utilise apixaban and rivaroxaban for patients switching from warfarin in an 80:20 split corresponding to the additional quantities secured for that reason [Citation69]. However, the price structure and complexity of such switching will have a major impact on CCG budgets. There is no established superiority of one DOAC over another in terms of efficacy and safety, although evidence suggests fewer bleeding incidents with apixaban [Citation70]. Edoxaban is rarely included in comparison studies as it is relatively new, but new evidence is expected to rapidly emerge because of the massive switching in a large population. Impacts on liver and renal function and related interactions will continue to emerge; especially as these will predominantly be in older adults. Head-to-head RCTs comparing the individual DOACs would provide more conclusive evidence to guide healthcare professionals’ decisions in managing their patients. A Danish phase 4 RCT (NCT03129490) [Citation71] comparing the four DOACs in atrial fibrillation was recruiting subjects and estimated to be completed by September 2021. Additionally, although minimal, there is heterogeneity in the level of adherence to different DOACs, with similar or slightly higher adherence observed with apixaban and rivaroxaban and lower adherence with dabigatran [Citation7,Citation51–54]. These differences can be attributed to multiple factors related to the patients (e.g. demographics, psychological factors, comorbidities and concomitant medications) or the treatment (e.g. dosage regimen, side effects and cost) [Citation7,Citation51,Citation54,Citation72,Citation73].

The notable increase in edoxaban prescription volume during the pandemic could be attributed to its once-daily dosage regimen, which is generally preferred. However, apixaban has generally been preferred (both for prescribing and adherence) despite its twice-daily regimen, likely due to its lower cost compared to rivaroxaban and edoxaban. Also, apixaban maybe preferred because of its lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients. In our expert understanding, the decrease in dabigatran prescription volume could be attributed to its high bleeding rate and low adherence compared to the other DOACs (mainly apixaban), however, this has not been demonstrated in independent research.

Although deemed a cost-effective treatment, apixaban had the highest total cost for items dispensed in the community in England in 2019 and 2020/21 of £290 million and £356 million, respectively [Citation74,Citation75]. As seen in the annual prescription cost analysis [Citation76], the total cost of the prescriptions dispensed in the community in England is increasing over the years. The generic entry of apixaban may contribute to cost management; however, this will not be accomplished in the near future, as apixaban patent expires in 2026 [Citation77]. Recently, NICE made a financial impact analysis of the recommendation of DOACs in the management of atrial fibrillation guideline (NG196) considering the expected increase in drug tariffs for the next five years (up to 2025/26) [Citation78]. They found that the increase in drug cost will be offset by anticipated benefits arising from a reduction in the requirement for anticoagulation clinics, but this is based on theoretical assumptions that may or may not be valid. Anticoagulation clinics are pivotal in anticoagulation management during COVID-19 pandemic. This is especially true for rethinking service delivery, managing patients infected with COVID-19 while on anticoagulant, and managing surveillance of routine patients during periods of lockdown and relaxed restrictions [Citation79]. Moreover, it is not clear if the COVID-19 pandemic effects on thrombosis and anticoagulation therapy and the impact of relevant guidelines issued during the pandemic have been considered in the financial analysis. As the population ages, the community prescriptions will likely increase, but some evidence suggests that the pandemic might shorten life expectancy, especially for disadvantaged segments of the population [Citation80,Citation81]. Therefore, life tables of population longevity should have also been involved in the financial analysis. Although drug prices did not change over our study period, the total cost of oral anticoagulant prescriptions increased; therefore, considering potential uncertainties around and plausibility of assumptions in the economic models, inflation, ageing population, supply chain disruptions, currency fluctuations and the significant pandemic influence on DOACs prescribing, reassessment of cost analysis might be warranted.

Our findings concerning the significant changes in anticoagulant prescribing patterns may reflect the real-life implications of altered healthcare and anticoagulation provisions and use during the pandemic. However, causality cannot be confirmed, nor short-term consequences anticipated. Our analysis provides an early signal for lower rates of adherence and offers potential for active decision making to optimise patient outcomes including for follow-up. This picture is highly relevant to England, but could provide early warning for many advanced nations that provide a structured program of care for such patients, making our findings relevant globally.

Strengths

This study benefits from the use of national, real-world data to evaluate the impact of a global pandemic on national oral anticoagulant prescription trends. This data may hint at the uptake of relevant national guidance and safety alerts issued during the COVID-19 pandemic. ITS analysis is generally unaffected by population demographics, socioeconomics and other confounding variables that remain relatively constant over time and have been captured by modelling the underlying trends, making it a robust modelling tool [Citation40].

Limitations

The EPD is frequently reviewed and updated, which might alter the accuracy of the current analysis and interpretations. However, the latest available version of the data was used in this analysis. Individual level demographic patient data was unavailable for this study (e.g. individual prescription details, documented diagnosis, duration of treatment and presence of risk factors that limited use or lead to discontinuation of the oral anticoagulants) and would be recommended for further research. Confounding variables can be the longstanding trend over which warfarin has been substituted with DOACs. The research team do not have access to patient identifiable data (e.g. biographic/demographic data). Rates of hospitalisation were substantially lower than normal because all elective procedures had been suspended and only urgent operations and procedures were being performed. Even maternity services were scaled down. As a result, hospitalisation during this would not reflect ‘true unmet medical need’ for secondary care. For that matter, primary care had also largely shutdown and no face-to-face consultations were being provided with only ‘digital consultations’ and prescription medication with minimal evaluation of risks such as bleeding. However, uni/multivariate analysis might not be representative of these patients during the pandemic where normal hospitals functioning had been affected.

Implications for clinical practice

This study highlights significant changes in DOAC prescription patterns during the study-period. These findings could guide healthcare organisations in the preparation and allocation of appropriate resources to improve clinical and economic outcomes during a pandemic and for future pandemics.

Clinicians need to assess patients’ adherence at each patient interaction with proactive attempts to reinforce its importance and ensure the patients receive the medications they need. Healthcare providers should work collaboratively with patients to understand their current status (comorbidities and medications, medication use habits, medication access issues and their health concerns) to help enhance adherence levels. Pharmacies and GPs need to proactively detect potential nonadherence, monitor its consequences, while looking out for known and unknown adverse effects of successful switching. Healthcare professionals should guard against co-prescribing through assuring that warfarin prescription is withheld when switching to DOAC during both the prescribing and dispensing process, advising patients to discard any remaining warfarin.

Increasing the frequency of monitoring for patients with a high risk of bleeding, advise and empower patients to report bleeding incident directly through the yellow card scheme, maximise the reporting of minor and major bleeding incidents to enhance the national-level statistics and hence preparedness. A targeted approach might be needed for patients at high risk of thrombotic or bleeding complications. The health records and appointments of such patients should be tracked to prioritise and recall those with urgent need.

Future studies

Future studies should aim to investigate the underlying causes of the changes in prescription trends from patients’ and prescribers’ perspectives. Investigations of changes in the rate of bleeding and thrombotic complications and related hospital admissions during the pandemic should be performed. It would also be interesting to correlate the pattern of change in DOAC prescriptions with variations in reported bleeding or thrombotic incidents, including stroke. Budget impact analyses of the expedited and massive switching from warfarin to DOACs and other relative recommendations and practices during the pandemic need to be done. Researchers should establish a granular risk-benefit profile. Impacts on the healthcare workforce should be investigated.

Conclusion

The volume of DOAC prescriptions increased at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by a gradual deceleration as compared to the pre-pandemic prescription trends. Despite the switching from warfarin to DOACs during the pandemic, the overall use of oral anticoagulants was lower than anticipated. This indicates that the switching did not sufficiently explain the potential unmet medical need. There were regional variations in the dominance of one DOAC over another. A higher net cost of oral anticoagulants was observed during the pandemic. More needs to be done to safeguard these patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper was not funded and was conducted as part of an MSc Clinical Pharmacy programme of academic studies.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

SA conducted the literature search, data extraction (Nov 2020 to Feb 2021), statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. RB was principal investigator and study supervisor responsible for study conception, design, data extraction (Jan 2019 to Oct 2020), interpretation, and revision. Both authors agreed on the final draft for publication.

Appendices_1-5.docx

Download MS Word (874.9 KB)Acknowledgements

None.

References

- World Health Organization. Global health estimates: Leading causes of death: WHO; 2000–2019 [cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death

- Hirsh J, Fuster V, Ansell J, et al. American heart association/american college of cardiology foundation guide to warfarin therapy1. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(9):1633–1652.

- Chan Noel C, Eikelboom John W, Weitz Jeffrey I. Evolving treatments for arterial and venous Thrombosis: Role of the Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Circ Res. 2016;118(9):1409–1424.

- Eriksson BI, Quinlan DJ, Weitz JI. Comparative pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of oral direct thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors in development. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48(1):1–22.

- Verheugt FWA, Granger CB. Oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: current status, special situations, and unmet needs. The Lancet. 2015;386(9990):303–310.

- Abdou JK, Auyeung V, Patel JP, et al. Adherence to long-term anticoagulation treatment, what is known and what the future might hold. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(1):30–42.

- Ozaki Aya F, Choi Austin S, Le Quan T, et al. Real-World adherence and persistence to direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2020;13(3):e005969.

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Pradaxa hard capsules: emc; 2008 [updated 02 Jul 2020. cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4703/smpc.

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Xarelto film-coated tablets: emc; 2008 [updated 05 Feb 2021. cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6402/smpc.

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Eliquis film-coated tablets: emc; 2011 [updated 26 May 2021. cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4756/smpc.

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Lixiana Film-Coated Tablets: emc; 2015 [updated 12 Jan 2021. cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6907/smpc.

- Chen A, Stecker E, Bruce AW. Direct oral anticoagulant use: a practical guide to common clinical challenges. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(13):e017559.

- van der Hulle T, Kooiman J, den Exter PL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of novel oral anticoagulants as compared with vitamin K antagonists in the treatment of acute symptomatic venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(3):320–328.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a Meta-analysis of randomised trials. The Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955–962.

- Makam RCP, Hoaglin DC, McManus DD, et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants approved for cardiovascular indications: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0197583.

- López-López JA, Sterne JAC, Thom HHZ, et al. Oral anticoagulants for prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: systematic review, network Meta-analysis, and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j5058.

- Sterne JA, Bodalia PN, Bryden PA, et al. Oral anticoagulants for primary prevention, treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolic disease, and for prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: systematic review, network Meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(9):1–386.

- Cohen AT, Hill NR, Luo X, et al. A systematic review of network Meta-analyses among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a comparison of efficacy and safety following treatment with direct oral anticoagulants. Int J Cardiol. 2018;269:174–181.

- World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO's COVID-19 response: WHO; [updated 25 January 2021; cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guide for the management of anticoagulant services during the coronavirus pandemic, COVID-19 NHSE/I specialty guide: NICE; 2020. [updated February 2021; cited 2021 June]. Online. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/COVID-19/Specialty-guides/specialty-guide-anticoagulant-services-and-coronavirus.pdf.

- Malas MB, Naazie IN, Elsayed N, et al. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29:100639.

- Alikhan R, Cohen AT, Combe S, MEDENOX Study, et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with acute medical illness: Analysis of the MEDENOX study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(9):963–968.

- Chen Y-G, Lin T-Y, Huang W-Y, et al. Association between pneumococcal pneumonia and venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients: a nationwide population-based study. Respirology. 2015;20(5):799–804.

- Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Gupta A, Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group, et al. Pharmacological agents targeting thromboinflammation in COVID-19: Review and implications for future research. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(7):1004–1024.

- Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group, Endorsed by the ISTH, NATF, ESVM, and the IUA, Supported by the ESC Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: Implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and Follow-Up: JACC state-of-the-Art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973.

- Hajra A, Mathai SV, Ball S, et al. Management of thrombotic complications in COVID-19: an update. Drugs. 2020;80(15):1553–1562.

- McBane RD, 2nd, Torres Roldan VD, Niven AS, et al. Anticoagulation in COVID-19: a systematic review, Meta-analysis, and rapid guidance from Mayo clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(11):2467–2486.

- Marongiu F, Grandone E, Scano A, et al. Infectious agents including COVID-19 and the involvement of blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. A narrative review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(10):3886–3897.

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). A weekly report covering adverse reactions to approved COVID-19 vaccines: MHRA2021. [updated 9 July 2021; cited 2021 July]. Online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions#history.

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Coronavirus vaccine - weekly summary of Yellow Card reporting: MHRA; 2021 [updated 9 July 2021; cited 2021 July]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting#analysis-of-data.

- Pavord S, Lester W, Makris M, et al. Guidance produced by the Expert Haematology Panel (EHP) focussed on Vaccine induced Thrombosis and Thrombocytopenia (VITT): British Society for Haematology (BSH); 2021. [updated 20 April 2021; cited 2021 July]. Online]. Available from: https://b-s-h.org.uk/media/19718/guidance-v20-20210528-002.pdf.

- Napolitano M, Saccullo G, Marietta M, et al. Platelet cut-off for anticoagulant therapy in thrombocytopenic patients with blood cancer and venous thromboembolism: an expert consensus. Blood Transfus. 2019;17(3):171–180.

- Deshpande CG, Kogut S, Willey C. Real-World health care costs based on medication adherence and risk of stroke and bleeding in patients treated with novel anticoagulant therapy. JMCP. 2018;24(5):430–439.

- Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2003.

- Degli Esposti L, Buda S, Nappi C, Network Health-DB, et al. Implications of COVID-19 infection on medication adherence with chronic therapies in Italy: a proposed observational investigation by the fail-to-Refill project. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:3179–3185.

- Yao X, Abraham NS, Alexander GC, et al. Effect of adherence to oral anticoagulants on risk of stroke and major bleeding among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(2):e003074.

- Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309.

- Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, et al. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):950–956.

- Barrett R, Barrett R, Dhar K, et al. Gonadorelins adherence in prostate cancer: a time-series analysis of england’s national prescriptions during the COVID-19 pandemic (from jan 2019 to oct 2020). BJUI Compass. 2021;2(6):419–427.

- Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–355.

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Interrupted time series (ITS) analyses: EPOC Resources for review authors; 2017. [cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors.

- The official home of UK legislation. The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020: The National Archives on behalf of HM Government; 2020 [cited 2021 June]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2020/350/contents/2020-03-26.

- NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) Data warehouse. English Prescribing Dataset (EPD): Open Data Portal for the NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA); 2020 [updated 14 June 2021; cited 2021 June]. v001:[Online]. Available from: https://opendata.nhsbsa.net/dataset/english-prescribing-data-epd.

- Nelson BK. Statistical methodology: V. Time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(7):739–744.

- Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, et al. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(4):613–623.

- The Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO). Open Government Licence V2.0: HMSO; [cited 2021 April]. Available from: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/.

- The World Medical Association (WMA). Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects: WMA; 2018. [cited 2019 June]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

- Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, RECORD Working Committee, et al. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885.

- National Health Service (NHS). Using the NHS and other health services during coronavirus (COVID-19): NHS; [updated 8 July 2021; cited 2021 July]. Online]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/social-distancing/using-the-nhs-and-other-health-services/.

- National Health Service (NHS). The NHS website repeat prescription ordering service: NHS; [updated 14 July 2020; cited 2021 July]. Online]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/nhs-services/prescriptions-and-pharmacies/the-nhs-website-repeat-prescription-ordering-service/.

- Salmasi S, Loewen PS, Tandun R, et al. Adherence to oral anticoagulants among patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e034778.

- Banerjee A, Benedetto V, Gichuru P, et al. Adherence and persistence to direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a population-based study. Heart. 2020;106(2):119–126.

- Manzoor BS, Lee TA, Sharp LK, et al. Real-World adherence and persistence with direct oral anticoagulants in adults with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(10):1221–1230.

- Ferroni E, Gennaro N, Costa G, et al. Real-world persistence with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in naïve patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. International Journal of Cardiology. 2019;288:72–75.

- Aronis KN, Hylek EM. Evidence gaps in the era of Non-Vitamin K oral anticoagulants. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(3):e007338.

- Curtis HJ, MacKenna B, Walker AJ, et al. OpenSAFELY: impact of national guidance on switching from warfarin to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in early phase of COVID-19 pandemic in England. medRxiv. 2020.

- Patel R, Czuprynska J, Roberts LN, et al. Switching warfarin patients to a direct oral anticoagulant during the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. Thromb Res. 2021;197:192–194.

- Lutz J, Jurk K, Schinzel H. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with chronic kidney disease: patient selection and special considerations. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:135–143.

- Lyman GH, Carrier M, Ay C, et al. American society of hematology 2021 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention and treatment in patients with cancer. Blood Adv. 2021;5(4):927–974.

- Sabatino J, De Rosa S, Polimeni A, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with active cancer: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JACC CardioOncol. 2020;2(3):428–440.

- Alfirevic A, Downing J, Daras K, et al. Has the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in England increased emergency admissions for bleeding conditions? A longitudinal ecological study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e033357.

- Ingason AB, Hreinsson JP, Ágústsson AS, et al. Rivaroxaban is associated with higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding than other direct oral Anticoagulants : A Nationwide Propensity Score-Weighted Study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(11):1493–1502.

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs): reminder of bleeding risk, including availability of reversal agents, Drug Safety Update: MHRA; 2020. [cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/direct-acting-oral-anticoagulants-doacs-reminder-of-bleeding-risk-including-availability-of-reversal-agents.

- Flynn D, Moloney E, Bhattarai N, et al. COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(4):673–691.

- National Health Service (NHS). A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions England: NHS; [cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/.

- National Health Service (NHS). Admissions for stroke per month and the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19): NHS Digital; 2020 [updated 14 September 2020; cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/2020/stroke-admissions-and-the-impact-of-coronavirus.

- National Health Service (NHS). Integrated Urgent Care (including NHS 111) England: NHS; [cited 2021 June]. Online]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/nhs-111-minimum-data-set/.

- Crotty BH, Hyun N, Polovneff A, et al. Analysis of clinician and patient factors and completion of telemedicine appointments using video. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2132917.

- National Health Service (NHS). Supply of additional direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) during COVID-19 England: NHS; 2020. [cited 2021 June]. Available from: https://www.worcslmc.co.uk/cache/downloads/C0517-DOAC-briefing-for-CCGs_27-May.pdf.

- Douros A, Durand M, Doyle CM, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis of observational Studies. Drug Saf. 2019;42(10):1135–1148.

- The Danish Non-vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulation Study in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (DANNOAC-AF): ClinicalTrials.gov; [cited 2021 November]. Online]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03129490.

- Amin A, Marrs JC. Direct oral anticoagulants for the management of thromboembolic disorders: the importance of adherence and persistence in achieving beneficial outcomes. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016;22(7):605–616.

- McHorney CA, Peterson ED, Ashton V, et al. Modeling the impact of real-world adherence to once-daily (QD) versus twice-daily (BID) non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants on stroke and major bleeding events among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):653–660.

- NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA). Prescription Cost Analysis - England 2019 England: NHSBSA; 2020 [updated 14 January 2021; cited 2021 September]. Online]. Available from: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/prescription-cost-analysis-england/prescription-cost-analysis-england-2019.

- NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA). Prescription Cost Analysis - England 2020/21 England: NHSBSA; 2021 [cited 2021 September]. Online]. Available from: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/prescription-cost-analysis-england/prescription-cost-analysis-england-202021.

- NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA). Prescription Cost Analysis - England England: NHSBSA; [cited 2021 September]. Online]. Available from: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/prescription-cost-analysis-england.

- Intellectual Property Office. Supplementary Protection Certificate 2011. [cited 2021 September]. Online]. Available from: https://www.ipo.gov.uk/p-find-spc-byspc-results.htm?number=SPC/GB11/042.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Resource impact report: Atrial Fibrillation: management (NG196): NICE; 2021 [cited 2021 September]. Online]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196/resources/resource-impact-report-pdf-9078749533.

- Poli D, Tosetto A, Palareti G, On the behalf of Italian Federation of Anticoagulation Clinics (FCSA), et al. Managing anticoagulation in the COVID-19 era between lockdown and reopening phases. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(5):783–786.

- Islam N, Jdanov DA, Shkolnikov VM, et al. Effects of covid-19 pandemic on life expectancy and premature mortality in 2020: time series analysis in 37 countries. BMJ. 2021;375:e066768.

- Office for National Statistics. National life tables – life expectancy in the UK: 2018 to 2020: OSN; 2021 [cited 2021 November]. Online]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/nationallifetablesunitedkingdom/latest.