ABSTRACT

Wine is a highly-valued-added end product of an important agricultural value chain. In this product category, the single-serve wine by-the-glass (WBG) option in restaurants presents a largely underutilized business opportunity. Academic research examining consumer behavioural psychology-based constructs in the situational consumption context of restaurants, has also not kept pace with this market reality. Hence, this study establishes how product involvement, risk perception, and information processing, affect consumption of WBG by consumers in the situational milieu of restaurants. Following scale validation by conducting confirmatory factor analysis and thereafter fitting a structural equation model, the relationships between constructs are examined by utilising a sample of 1,038 South African consumers representative of dining across all restaurant categories. The findings contribute to the literature by showing that distinct motivational relationships exist between the involvement and perception of risk constructs and information-related behaviour of consumers engaging with the WBG option in restaurants. The stable nature of consumers' enduring involvement with wine products evokes motivational processing by triggering situational involvement upon purchasing WBG and perception of risk arousal of both the cognitively-evaluated (psychological, social and functional) and non-cognitively-evaluated (financial, physical and time) risk types.

1. Introduction

Wine is a highly-valued-added end product of what is an important agricultural value chain. The wine market splits into two main categories: off-premise (take-home retail sales) and on-premise (on-site consumption, e.g., at restaurants). Of specific relevance to the on-premise category, is the fact that the growth trend in single-serve portions of food and beverage products is expected to continue into the next decade until 2030 (Mintel Citation2019). Although the marketing opportunity offered by the single-serve WBG (wine-by-the-glass) option is significant, its utilisation has been below the growth potential it represents (Frost Citation2015; Yoon and Stacy Citation2015). Durham et al. (Citation2004) found that offering WBG is an important factor in realising at least some wine sales. Among the other opportunities associated with the WBG option, expensive wines could be sold faster if more WBG options were made available in restaurants (Frost Citation2015). More specifically, providing WBG options in restaurants articulates to a five percent increase in the bottle price for similar wines offered in bottles, and a twelve percent increase in the bottle margin (Dearden et al. Citation2021). However, utilising the WBG opportunity will need a shift in mindset by many restaurants that view WBG largely as a way to offer consumers “something” instead of “nothing” in the form of single-serve wine options.

Despite the business opportunity that WBG sales in restaurants represents, academic research in this area of marketing and consumer behavioural responses is still at a juvenile stage. This is quite surprising in view of the fact that the hospitality industry, and particularly, the foodservice component thereof, present many situations that are conducive to the formation of attitudes (Lacey et al. Citation2009). Consumers’ interpretation of a specific situation is instrumental in their attitude formation that takes place (Carvalho et al. Citation2018) and, in turn, can affect their behaviour, for example, ordering wine in a restaurant (Lacey et al. Citation2009), and thus could have an impact on strategies of marketing to them. Despite this gap in the knowledge base, most of the research focus has been on the wine taste preferences of consumers (Giacalone et al. Citation2014; Rinaldo et al. Citation2014). Attitude formation from a psychological viewpoint has received less attention (Thomé et al. Citation2016; Carvalho et al. Citation2018), while even fewer (Bruwer et al. Citation2017; Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019) focused on the motivational perspectives of consumers’ relationship with WBG. That is, despite attempts in the form of exploratory studies to develop risk perception scales (Bruwer et al. Citation2017; Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019) and work by Terrier and Jaquinet (Citation2016) on the pairing of food and wine as a risk-reduction strategy (RRS). These studies however, treated perceived risk as a unidimensional construct and did not conduct the conventional reliability and validity testing on the risk measurement scale.

Consumer behavioural psychology (Saad Citation2021) applies a motivational perspective to product involvement and risk perception as constructs, and their effect on the subsequent behavioural responses of seeking and dissemination of product information (Klerck and Sweeney Citation2007). Hence, there is a need for a theory-rooted study, viewed through the behavioural psychology lens (Miranda and Duarte Citation2022), to determine how the individual WBG risk perception dimensions interrelate with product involvement and information-processing behaviour. Such a study will benefit from a strong theoretical grounding using a framework such as a motivational process model provides (Dholakia Citation2001; Sun et al. Citation2010). Theory-building research on WBG consumption in restaurants specifically focused on these pivotal constructs, will not only lay a theoretical foundation in the hospitality management domain, but open an avenue for academic discourse. Hence our study’s objective is to confirm a theory-based model of product involvement and perception of WBG risk that includes information-related behaviours in the motivational process of consumers when exposed to the situation of WBG ordering in restaurants. It achieves this by successfully treating WBG risk perception as a multi-dimensional construct in the restaurant context.

In the agricultural value chain, the wine category has been a prominent and highly value-added final product over many decades, even hundreds of years. Not surprisingly, from a generic viewpoint, its end-use has been extensively examined in the literature from, what has often been, a behavioural perspective. Despite the importance of the on-premise sector to the wine product category, there is however, a paucity among previous research to focus on consumption in the on-premise sector, notably in restaurants. With single-serve consumption in the on-premise sector rapidly on the increase (Mintel Citation2019), WBG consumption in restaurants is an area on which minimal research attention has been focused (Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019). Not only does our study contribute to the theory base by providing nuanced insights from the perspective of holistic and consumer-centric behavioural psychology (Saad Citation2021; Miranda and Duarte Citation2022), but it does this in South Africa, a country where such research has to date been absent. More specifically, we develop a theory-based motivational process model and use structural equation modelling (SEM) to test the relationships between focal behavioural psychology constructs for this specific consumption situation.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

Consumer behaviour, and per se marketing, is a reasoned action and consumption-relevant as a result of cognition and its conscious thinking processes (Grunert and Grunert Citation1995). Therefore, the focal motivational consumer behaviour constructs and psychological processes of product involvement, perceived risk, and information processing as these relate to the restaurant environment and the WBG option, can be theoretically explicated by means of a motivational process model (Dholakia Citation2001). Via this avenue, the current study contributes by providing theoretically grounded insights of various related consumer behavioural psychology constructs in the restaurants’ situational setting.

2.1 Product involvement

Involvement is “a motivational state that affects the extent and focus of consumers’ attention and comprehension processes” (Celsi and Olson Citation1988, p. 210), “as well as overt behaviours such as shopping and consumption activities” (Tarkiainen and Sundqvist Citation2009, p. 847). The definition of consumer involvement is consistent with our study’s motivational perspective.

Involvement has been a subject of interest in the marketing literature largely because of its motivational influence on behavioural outcomes, for instance, consumers’ seeking, dissemination and processing of information and their influence on buying behaviour (e.g., Warrington and Shim Citation2000; Bruwer et al. Citation2017). Since the early days of studying involvement, researchers distinguished between two types: enduring and situational involvement (e.g., Bloch and Richins Citation1983; Celsi and Olson Citation1988). The main differentiation between enduring and situational involvement is temporal duration and thus persistence, with enduring involvement less temporal and more persistent than situational involvement (Richins and Bloch Citation1986, Warrington and Shim Citation2000). Situational involvement is characterised by its fluctuating nature caused by the temporary arousal of the consumer’s interest inherently linked to the timeframe of the purchase decision (Park and Moon Citation2003), and/or the use of a product in a specific situational context (Warrington and Shim Citation2000), such as ordering the WBG option from the wine menu in a restaurant.

By its nature, enduring involvement is a phenomenon that has more stability in its representation of the personal interest of the consumer in the product over an extended period of time (Park et al. Citation2007). Moreover, a direct association between a person’s self-concept and enduring product involvement was found (Roe and Bruwer Citation2017), meaning that a potential relationship exists between enduring involvement and psychological risk. In the case of wine in a restaurant to accompany a meal, consumers who feel that the WBG options resonate strongly with their self-concept, will be more motivated to make a “satisfactory purchase”.

Product and/or environmental factors induce states of arousal and interest in both enduring and situational involvement (Guthrie and Kim Citation2009). These occur because both have similar behavioural responses in the form of attention to product-related information and motivation-induced search (Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019) for information and dissemination (Richins and Bloch Citation1986; Celsi and Olson Citation1988; Ogbeide and Bruwer Citation2013). Environmental aspects, inherent in the risk perceived when dining in a restaurant, induce the interest and arousal associated with situational involvement. Park and Moon (Citation2003) found that situational involvement’s fluctuating nature is inherently linked to the timeframe of a purchase decision, which is typically present in the ordering of a WBG serving from the wine menu during a dining occasion at a restaurant.

The product involvement construct has long been associated with wine (Zaichkowsky Citation1985), and several later studies have utilised this premise and further developed the situational context of wine and consumer involvement (Charters and Pettigrew Citation2006; Ogbeide and Bruwer Citation2013; Bruwer et al. Citation2019). There is also evidence that information seeking and dissemination have associations with involvement (Ogbeide and Bruwer Citation2013). Information seeking furthermore, has an important role in wine purchasing in its use in response to risk perception by acting as a RRS (Johnson and Bruwer Citation2004).

2.2 Perceived risk

Perceived risk as a concept has a history dating back to the 1920s when it was first used in the economics and eventually in the marketing field (Bauer Citation1960). Its development has led to the belief that a better understanding thereof could be an important initial step in developing marketing strategies (Phillips and Hallman Citation2013). Since then, risk perception has been conceptualised in various ways but the one most commonly used by researchers is that of the consumer being faced by feelings of uncertainty when unable to foresee, in particular, negative outcome(s) of a buying decision (Mitchell Citation1999). It was found that the consequences, magnitude and likelihood that adverse consequences may occur if the product is purchased, are mapped into the perceived risk construct (Dowling and Staelin Citation1994).

The contemporary consumer perceived risk construct is multi-dimensional (Mitchell Citation1999; Blais and Weber Citation2006) and incorporates the various dimensions of risk (Bruwer et al. Citation2017; Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019). The construct currently comprises six risk dimensions: physical, functional, financial, time, social and psychological risk (Johnson and Bruwer Citation2004). These comprehensively account for and include the uncertainty(ies) a consumer may perceive in the WBG consumption situation in restaurants (Bruwer et al. Citation2017). The functional risk dimension measures the concern (wine) consumers have about the taste (performance) of the product, while the financial risk dimension measures the degree of possible financial loss. Physical risk is represented by the intensity of the feeling of discomfort and/or enduring detrimental health effects upon consuming the product. Psychological risk denotes the potential loss of self-esteem and negative affective states such as anxiety, guilt, etc. if the product is not consistent with persons’ perception of self-identity (Blais and Weber Citation2006). Social risk perception occurs when significant others will not approve of the product, in other words, another person is the source of this uncertainty (Bohnet et al. Citation2008). Time risk is the potential loss of time associated with making a (bad) purchase decision in terms of the time spent researching and purchasing the product (Bruwer et al. Citation2017). As a counterintuitive response, consumers adopt various RRS to help them cope with the situation, in the process exhibiting behaviours that are dependent upon the degree of importance of a particular type of risk (Blais and Weber Citation2006).

There is evidence that a consumer’s perception of risk is influenced by his/her involvement with the purchase decision (Dowling and Staelin Citation1994; Dholakia Citation2001; Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019). Product involvement and perceived risk both act in motivating consumer behaviours from a motivational perspective. The extant literature is largely in agreement about the distinctiveness of the involvement and risk perception constructs (e.g., Dowling and Staelin Citation1994), although some authors suggest that perceived risk is either an antecedent (Bloch Citation1981), or a dimension of product involvement, or a consequence thereof (Laurent and Kapferer Citation1985).

The process of consumers purchasing wine products has generally been associated with, at times, high complexity and resultingly the perception of risk (Johnson and Bruwer Citation2004). This association with risk perception also transcends to the hospitality situational context and is a major factor affecting consumer decision-making (Bruwer and Rawbone-Viljoen Citation2013). Often risk perception depends on consumers’ interpretation of a specific consumption situation (Bruwer et al. Citation2017), e.g., when faced with the decision of ordering WBG in a restaurant setting. Lacey et al. (Citation2009) found that, in the Australian restaurant sector, tasting a small wine sample before ordering a larger quantity, reduces the majority of perceived risk evoked by the taste of the product. The situational aspect in which WBG is ordered and consumed is therefore helpful towards developing deeper insights into the behavioural responses that consumers have to perceived risk. Their responses are thus dependent upon their interpretation of this situation.

Despite it being referred to in the discussion of risk perception occurring in the on-premise trade (Bruwer and Rawbone-Viljoen Citation2013), a limited number of research studies (Terrier and Jaquinet Citation2016; Bruwer et al. Citation2017; Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019; Acuti et al. Citation2020) have had as their focus WBG as RRS in restaurants. Although the WBG strategy is RRS-specific to the consumption situation in restaurants, its relevance to each type of risk encountered in this situational context, warrants further investigation.

2.3 Search for and dissemination of information

Because much choice and buying behaviour is preceded by information search behaviour in some form, such search behaviour has been a focal topic of research (Peterson and Merino Citation2003). Information search activities have the role of being important RRS (Lacey et al. Citation2009; Bruwer et al. Citation2013). Decisions to purchase vary in complexity, requiring even greater effort when searching for product information for the purpose of RRS (Lacey et al. Citation2009) and, especially so in a high-risk perception environment such as WBG ordering in a restaurant with a meal.

The extant literature provides evidence of differences that exist between hedonic and utilitarian products when consumers process information pertaining to these product types (Laurent and Kapferer Citation1985; Palazon and Delgado-Ballester Citation2013). Alike craft beer (Bruwer and Cohen Citation2022), WBG fits the context of a hedonic product which provides a sensory experience of fun and/or pleasure, especially for consumers with an experiential orientation (Bűttner et al. Citation2013). The situational context is an inherent aspect in the restaurant environment where WBG consumption occurs and adds to the hedonic perspective our study provides.

Previous research found that the type of involvement, whether enduring or situational, can be a driver of consumer information processing method and intensity (Celsi and Olson Citation1988; Park and Moon Citation2003). The motivation to process information is associated with the consumer’s degree of involvement with the various informational stimuli.

A number of effects have been identified by research examining the relationship(s) between information-related behaviour with product involvement and risk perception (Phillips and Hallman Citation2013). Different types of word-of-mouth activities, such as opinion leadership and seeking, are influenced by enduring and situational involvement (Dholakia Citation2001) and by psychological and social risk perception (Lin and Fang Citation2006). Product- and/or situation-related information give rise to various types of risk perception aroused by the composite mental activity of processing such information (Dholakia Citation2001). Moreover, information search behaviour to reduce the perception of risk occurs at two levels, with consumers routinely conducting information search in order to acquire general product information and, at times, to reduce a specific type of risk associated with a situation in which consumption occurs (Dowling and Staelin Citation1994). The need for cognitive closure also plays a role in consumers’ information search behaviour (Choi et al. Citation2008), and more specifically, in situations in which the importance of action in the form of decision is high, which is a scenario classically present with the WBG decision in restaurants.

Wine is a product type requiring much information to completely describe its characteristics in order to be able to make an informed purchase and/or consumption decision (Dodd et al. Citation2005; Lesschaeve et al. Citation2012; Ellis and Caruana Citation2018). Investigating information-related processing and behavioural roles in the motivational processes leading to the actioning of the WBG buying decisions, thus has theoretical value.

2.4 Conceptual model of constructs’ relationships

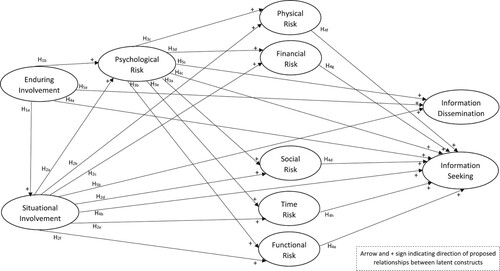

The psychological processes and motivational consumer behaviour constructs can be theoretically explained by a conceptual model of product involvement, perceived risk, and information processing (Dholakia Citation2001). This should also hold for how these relate to the restaurant environment, and specifically the WBG option (Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019). Our study develops a motivational process model that offers a complete and integrated view of how the latent constructs relate to and influence one another (see ). A premise of this model is that all the latent constructs have a distinct nature and influence one another. The execution of the model is instrumental in contributing to the aforementioned gap in the literature.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of wine by-the-glass (WBG), product involvement, risk perception and information processing.

Based on the theoretical linkages between the discussed latent constructs, in the first instance, we propose that:

H1: Enduring involvement (E_I) positively influences a) situational involvement (S_I) with the wine product class, and b) psychological risk (Psych_R) perception of the WBG option.

H2: Situational involvement (S_I) positively influences the perception of a) psychological risk (Psych_R), b) physical risk (Phys_R), c) financial risk (Fin_R), d) social risk (Social_R), e) time risk (Time_R), and f) functional risk (Funct_R) aroused by the WBG option.

H3: The arousal of psychological risk (Psych_R) perception by the WBG option, positively influences the perception of a) social risk (Soc_R), b) functional risk (Funct_R), c) physical risk (Phys_R), d) financial risk (Fin_R), and e) time risk (Time_R).

H4: Seeking product-related information (I_S) before purchasing WBG is positively influenced by a) enduring involvement (E_I) and b) situational involvement (S_I) with the wine product class; and the perception of c) psychological risk (Psych_R), d) social risk (Soc_R), e) functional risk (Funct_R), f) physical risk (Phys_R), g) financial risk (Fin_R) and h) time risk (Time_R) aroused by the WBG option.

H5: Providing product information (I_P) before purchasing WBG is positively impacted by a) enduring involvement (E_I) and b) situational involvement (S_I) with the wine product class; and also, with c) psychological risk (Psych_R) perception aroused by the WBG option.

shows the conceptual model of the focal constructs, the proposed influences between constructs and on consumers’ information-related behavioural responses.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study context

We chose the South African restaurant industry as the focus of our study. South Africa is the largest economy on the African continent and a significant entity in the world wine market. The 2020 revenue of South Africa’s on-premise foodservice industry amounted to ZAR 81.6 billion ($US 5.68 billion) and its domestic wine market revenue to ZAR 47.2 billion ($US 3.3 billion equivalent). In the large markets in Europe (e.g., the UK), and also in the USA, the on-premise sector typically has a volume share of around 20%, while by contrast in South Africa the comparative figure is 32% with this volume contributing 38% of wine’s sales value in South Africa (Euromonitor International Citation2021). Considering that the country’s consumer food-service industry is valued at ZAR 130.3 billion ($US 9.0 billion) with drinks contributing 29.6% of that (Euromonitor International Citation2022), wine is therefore a key contributor to the South African restaurant industry, accounting for a significant portion of restaurant revenue.

3.2 Measures

Data collection to test the study’s hypotheses was achieved by executing an online survey among dining patrons of restaurants in South Africa on a nationally geographically representative sample of restaurant dining patrons. The collection of the data was completed in late 2019, just prior to the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic, meaning that the pandemic and actions such as “lockdowns’ had no effect on the results of our study. The survey instrument consisted of three sections: seven-point Likert measurement scale items for product involvement, WBG risk perception, and information seeking-dissemination, as well as associated consumption metrics and, also socio-demographics.

The product involvement (enduring and situational) construct was measured using scale items from Bruwer and Cohen (Citation2019), following their adjustment to the contexts of the wine product category and the situational aspect in restaurants. After adjustment to the wine and restaurant contexts, we used items from Bruwer and Cohen (Citation2022) to measure information seeking and dissemination. The risk perception construct and its elements were measured using 24 adapted scale items from Bruwer and Cohen (Citation2022) and Dholakia (Citation2001).

We used procedural (ex ante) remedies to control for common method variance (CMV) as a countering action to the self-reported nature of the data (Mackenzie and Podsakoff Citation2012). In the process, we adopted counterbalancing questions order and different response formats. For example, we asked respondents about their product involvement and risk perception before asking about their information processing to avoid priming effects. Respondents had to answer all questions thus there was no missing data and no non-response bias issues.

We used a decompositional approach as in Taylor and Todd (Citation1995) to measuring the respective constructs. Such an approach has been previously used in studies of involvement (Richins and Bloch Citation1986; Ogbeide and Bruwer Citation2013) and risk perception (Dholakia Citation2001; Bruwer et al. Citation2017).

3.3 Sample and procedure

Data collection was by means of an online survey obtained from a geographically representative sample of restaurant dining patrons in South Africa. The participants were recruited from the national data base of a professional third-party consumer panel provider. The sample frame consisted of people from their South African “general population” database who complied with certain qualification criteria: wine consumers, 18 years and older (in accordance with the country’s alcohol consumption regulations), dined out at a venue fitting the restaurant classification (Euromonitor International Citation2022) at least once in the past month, where they bought and consumed WBG. The nomenclature of the seven restaurant categories is the result of adapting the USA categorisation (Canziani et al. Citation2016) and combining that with the South African consumer food-service industry categorisation (Euromonitor International Citation2022), which will aid future studies.

We collected information from respondents during a 7-day time frame ensuring coverage of all week and weekend days. An online survey was programmed in Qualtrics using the panel provider’s online survey platform. A series of decision rules and attention check questions were implemented to obtain quality data. Additional to the advantage an online survey has of eliminating invading the privacy of diners when collecting information in restaurants in situ (Bruwer et al. Citation2017), our survey successfully sampled respondents throughout South Africa and across all of its restaurant categories. We contacted 4,267 people with 2,347 initially agreeing and qualifying to participate in the research study. A total of 1,250 persons completed it from which 1,038 surveys could be utilised for final analysis (44% response rate). Data analysis was executed by means of SPSS 26 and the R package Lavaan software.

The socio-demographics and consumption metrics of the respondents are exhibited in . The gender split is 55% female and 45% male and the average age of the sample is 43.9 years, which is close to the mid-point of the Generation-X age cohort. More specifically, the age generation cohort distribution (Pew Research Center Citation2015) is 32% Millennials (born after 1980), 39% Generation-X (born 1965–80), 23% Baby Boomers (born 1946–1964), and 2% Silent Generation (born 1928–45). also shows that 68% are married or living with a significant other in a household in which 3.4 persons live together (usually 2 adults and 1 child); education wise 70% possess a university or post-secondary qualification; and have median monthly earnings of ZAR 51,979 (US$ 1.00 = ± ZAR 18.00) in the household.

Table 1. Socio-demographics, restaurant category patronage and WBG metrics of respondents.

As far as the respondents’ last dining experience before participating in the study is concerned, reveals that the most frequented restaurant category was full-service family restaurants (35%), with specialist steakhouses (23%), fine-dining upscale (18%), casual ethnic food-service (15%), and all other restaurant categories (9%) following. On this dining occasion the WBG consumption metrics reveal that the consumers spent an average of ZAR 192 on wine (WBG servings and full bottle) and also that the dining groups were multi-person in nature (an average of 3.7 persons per group). A mere 2% of respondents wasn’t part of a multi-person group, electing to dine out alone. The multi-person nature of the dining groups could, at least in part, explain why respondents ordered 1.95 WBG servings (150 ml. size each) on average. Moreover, the multi-person nature of the dining group could explain why, for the table, an additional 0.9 standard-size 750 ml bottle(s) was/were also ordered by the diners who perhaps preferred either a different wine type to the available WBG options available, or felt that WBG was too expensive relative to the quantity of wine offered, etc. Males consumed volumetrically 18% more and spent 9% more money on WBG than females in the dining situation. This is put in some perspective by the fact that the overall monthly wine consumption of females is 11% less than that of males.

3.4 Structural equation model (SEM) fitting

To characterise our dataset’s variability, we conducted skewness and kurtosis tests. Skewness ranged from−0.894 to−1.799, thus below the threshold of 1.0. The kurtosis for all items ranged between−1.224 and 1.634 and conform with the threshold level of between−2.00 and 2.00 (George and Mallery Citation2010). The tests for skewness and kurtosis thus confirm that the distributions of the collected data are acceptable for conducting SEM analysis. SEM is a particularly suitable analysis technique when several dependent and independent variables are involved in complex models, to test the theories involved (Bagozzi and Yi Citation2012; Nunkoo et al. Citation2013). We executed CB-SEM analysis to examine the five constructs in our model using the two-step procedure due to its greater incidence of use by researchers (Nunkoo et al. Citation2013; Miranda and Duarte Citation2022).

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Structural model evaluation

Given the fact that previous attempts in the form of exploratory studies in the restaurant domain treated perceived risk as a unidimensional construct (Terrier and Jaquinet Citation2016; Bruwer et al. Citation2017) and did not comprehensively test the scale(s)” discriminant validity and reliability, these were deemed necessary requirements in our study. Hence, we first tested the psychometric properties of the WBG risk scale’s reliability, discriminant, nomological and convergent validity. We next conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the Lavaan R software package structured in accordance with the risk perception framework (Klerck and Sweeney Citation2007) to obtain each item’s loading on the dimensional variables of WBG risk perception. Cronbach alphas for the constructs’ scales to determine their reliability were also computed. We used the following inclusion criteria to identify the final set of items for the WBG risk perception scale:

– Standardised loadings on each latent construct’s selected items are >0.5

– Items selected for each latent construct, combine for a composite AVE >0.50 and alpha >0.70

The CFA’s outputs indicate satisfactory coefficient loading at > .50 of 24 WBG risk scale items on their dimensional factors and all goodness-of-fit (GoF) statistics above the minimum thresholds (see ). These procedures resulted in a final 24 item-set being selected, following the removal of one and the reversal of two scale items (see Appendices A and B).

Table 2. WBG risk perception constructs confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

For the six perceived risk dimensions (factors), all alpha reliability coefficients and AVEs were satisfactory (). These values range from alpha = .885 and AVE = .686 (psychological risk) to alpha = .711 and AVE = .513 (time risk), thus comfortably satisfying the Cronbach alpha criterion of .700 or greater and AVE 0.50 or greater (Nunnally and Bernstein Citation1994). When considering that social risk (alpha = .865 and AVE = 0.646) had the second highest values after psychological risk, the fact that these two cognitively evaluated risk dimensions produced robust results, is a positive outcome in that it confirms the strong impact of psychological and social risk on the product involvement construct (Dholakia Citation2001). The WBG risk scale yielded a satisfactory average inter-item covariance of 0.374 and composite alpha of 0.833. While achieving the desired Cronbach alpha threshold, the physical, financial, functional, and time risk dimensions in our model had acceptable, although relatively low AVEs values, which resulted in the reverse coding of two items (functional and financial risk) and the deletion of one (psychological risk). There is support for the retention of the constructs with lower AVEs due to one or two weaker latent variables in the SEM measurement model (Hair et al. Citation2011). The CFA results nevertheless confirm the convergent and discriminant validity of the WBG risk measurement scale with both the factor loadings ≥0.5 and AVE values ≥ the squared correlations (SCs) of the constructs (functional and financial risk excepted, before item reversal) (Sideridis et al. Citation2014).

In the case of the enduring involvement, situational involvement, information seeking and information provision scales, all alpha reliability coefficients and AVEs were satisfactory. shows that these values range from alpha = .798 and AVE = .601 (enduring involvement) to alpha = .912 and AVE = .838 (information seeking).

Table 3. Reliability analysis of involvement and information processing constructs scale items.

The results in and indicate the empirical distinctiveness of the latent constructs, thus facilitating fitting the measurement model of the motivational process.

4.2 Measurement model fit

The model was estimated using the R package of Lavaan’s SEM module. The model’s GoF statistics and other parameters are presented in and and show the significant and non-significant structural paths. Confirmation of the satisfactory overall fit of our model is provided by the GoFs in . The .057 RMSEA of our model complies with the recommended RMSEA threshold of .08 or less (Sideridis et al. Citation2014). Our model also complies with all other SEM model GoF thresholds (Nunkoo et al. Citation2013) in that GFI = .958 (recommended GFI is ≥ .900), AGFI = .917 (recommended AGFI is ≥ .900), and SRMR = .051 (recommended SRMR is ≤ .08).

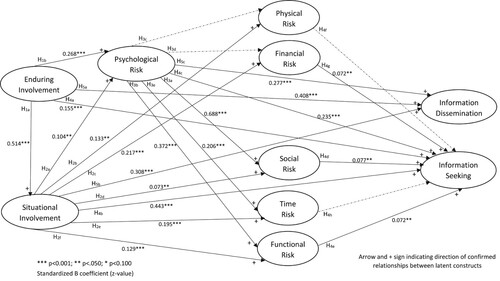

Figure 2. Estimated model of wine-by-the glass (wbg) product involvement, risk perception and information processing.

Table 4. Final SEM outer model loadings outputs.

4.3 Structural parameters for hypothesised paths

displays the path estimates and structural parameters in relation to the study’s hypotheses, while the final measurement model () shows the significant hypothesised paths.

Table 5. Parameter estimates for hypothesised paths.

The analysis confirms that consumers’ level of enduring involvement (E_V) with wine as a product positively affects both consumers’ situational involvement (S_V) with the WBG options in restaurants (H1a: β = 0.514; z = 12.294***), while at the same time, activating their psychological risk perception (H1b: β = 0.268; z = 4.986***). The results also show that consumers’ situational involvement with WBG in restaurants significantly affects all the risk types evoked by the WBG option: psychological (H2a: β = 0.104; z = 2.119**), physical (H2b: β = 0.133; z = 2.229**), financial (H2c: β = 0.217; z = 2.242**), social (H2d: β = 0.073; z = 2.006**), time (H2e: β = 0.195; z = 3.309***), and functional risk (H2f: β = 0.129; z = 3.124***). This deviates from the finding of Bruwer and Cohen (Citation2022) who found that, in the case of craft beer in restaurants, situational involvement only significantly affects psychological, but not social and functional risk perception. This finding is both insightful and a contribution to the theory base in that it confirms, across the full spectrum of risk types, that the WBG consumption situation in restaurants activates these emotions and that the perception of risk varies in intensity. The adoption of risk-reduction strategies (RRS) by consumers can mitigate the negative consequences on their behaviour as later further described in the implications sub-section of this document.

shows mixed results for our supposition that aroused psychological risk is not only an antecedent of social and functional risk, but also of physical, financial, and time risk in the WBG situation in restaurants. Psychological risk positively affects social (H3a: β = 0.688; z = 17.603***), functional (H3b: β = 0.372; z = 10.233***) and time risk (H3e: β = 0.206; z = 3.743***), but not physical (H3c: β = -0.031; z = -0.579) and financial risk (H3d: β = -0.066; z = -1.541). This contributes to theory by reaffirming the cognitively-evaluated risk relationship between psychological and social and functional risk, and adds time risk thereto. Further work on exploring the effects of psychological risk on financial and physical risk is needed.

Consumers’ inclination to obtain product-specific information (I_S) prior to purchasing the WBG option was strongly positively affected by both enduring involvement (E_I) with the wine product (H4a: β = 0.155; z = 3.385***) and situational involvement (S_I) with the WBG option (H4b: β = 0.443; z = 9.986***). Among the six risk types, four positively affected inclination to seek product-related information: psychological (H4c: β = -0.235; z = 2.913***), social (H4d: β = 0.077; z = 2.013**), functional (H4e: β = 0.072; z = 1.985**) and financial (H4g: β = 0.072; z = 1.989**), while the two other risk types did not support the hypotheses: physical (H4f: β = 0.039; z = 1.005) and time (H4h: β = -0.019; z = -0.486). This finding underlines the importance of sound product information (functional) and perception of value (financial) and confirms the pivotal role of the cognitively-evaluated risk types (psychological social and functional) in the purchase process in the situational milieu of restaurants.

Finally, the proposed impacts of enduring involvement (E_I) (H5a: β = 0.408; z = 8.720***) and situational involvement (S_I) (H5b: β = 0.308; z = 6.489***) on the consumer’s propensity to distribute information (I_P) related to the product before purchasing the CB option were also supported, as was the impact of aroused psychological risk (H5c: β = 0.277; z = 3.913***). Consumers with a high level of enduring involvement are likely to act as opinion leaders on the occasion of a dining group having a meal at a restaurant, based on the finding that the level of enduring involvement positively affects the need for consumers to disseminate information about wine to others.

shows the structural pathways of the hypotheses that were supported (solid line) and those not supported (dotted line). The results of the concepts validated in the SEM model, confirm the scales’ nomological validity and provide enrichment of their theoretical network.

5. Conclusions, implications, limitations, and future research recommendations

The current study makes a substantive contribution to the theory base by providing nuanced insights from the perspective of holistic and consumer-centric behavioural psychology. First, by creating, confirming and further developing consumer behavioural psychology insights pertaining to the focal consumer-centric constructs. Second, by developing a unique motivational process model, building further on the works of Bruwer et al (Citation2017) and Bruwer and Cohen (Citation2019), that explicates the processes that cause product involvement, risk perception and information-related responses and by which they impact one another. Third, by theoretically explaining the psychological processes in a cogent and uncomplicated way through this model. Finally, by successfully treating a theory-based motivational process model of risk perception as a multi-dimensional construct that includes involvement and information-related behavioural responses in the situational context of restaurants where consumers have exposure to a WBG ordering situation.

The research confirms the existence of relationships of a distinctive nature between the closely-related constructs of product involvement, perception of risk. and information-processing behaviour of consumers engaging with the WBG option when having meals in restaurants. Also confirmed are the situational involvement construct’s unstable nature, the stable nature of enduring involvement, and the pivotal role of psychological risk on social, functional and time risk as well, as on information processing. The enduring involvement state with wine brings about increased motivation from the situational aspects of WBG purchasing in the restaurant setting, by triggering situational involvement and the arousal of WBG risk perception of not only cognitively-evaluated risks (psychological, social and functional), but also non-cognitively-evaluated risks (financial, physical and time). The findings also confirm that WBG risk perception is a distinct multi-dimensional construct thus strengthening the knowledge base.

The results further contribute to theory by adding the time risk dimension as a non-cognitively-evaluated risk type to the already established cognitively-evaluated risk relationships that psychological risk have with social and functional risk (Dholakia Citation2001). The existence of the relationships between these cognitively-evaluated risk constructs is also reconfirmed. We further confirm that, for the wine product class, a positive relationship exists between information seeking behaviour and risk perception by consumers in restaurants. We also find that both enduring involvement and situational involvement, the latter in contrast to Dholakia (Citation2001), influence both product-related information seeking and dissemination.

Although few studies have examined the WBG consumption aspect in restaurants with meals, these span three countries: Australia (Bruwer et al. Citation2017), the USA (Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019), and South Africa (current study). A comparison of the headline metrics shows the largest WBG consumption (2.76 serves per person; 51% female weighted, and dining group size of 4.61 persons) in the USA market (Bruwer and Cohen Citation2019), with Australia slightly “behind” (2.38 serves per person, 58% female weighted, and dining group size of 3.25 persons) (Bruwer et al. Citation2017). In South Africa, by comparison, there were 1.95 WBG serves per person, a 55% female component in a dining groups size of 3.69 persons in the current study. With only these indicators available to compare the maturity stage of the WBG market in South Africa with that of the other countries, it seems safe to say that it is most likely in the intermediate stage, which gives further credence to its potential to become more prominent in future.

A number of practical implications emanate from our study’s findings for developing sound marketing strategies. Because of their involvement with wine, consumers are motivated to try various types of wine, which, all things equal, should have an encouraging effect on them to buy WBG in a restaurant setting. For restaurant managers, making the WBG option available is a strategy capable of increasing consumers’ learning about, and interest in wine. For example, in partnership with restaurants they supply their wines to, wine tasting experiences could be organised to make consumers aware and enable them to taste various WBG options.

A good understanding of consumers’ involvement with both the wine product and the WBG situation in a restaurant is central for restaurateurs in their quest to reduce risk perception and its adverse effects among consumers. Because restaurants do not have control over consumers’ enduring involvement with the wine product, their strategies should aim at ways in which they can reduce risk perception evoked by consumers’ situational involvement for each risk type pertaining to the WBG option. These actions can be focused on, but are not limited to, sommeliers’ recommended WBG selections, user-friendly wine menus, suggestions for food and wine pairing, WBG special price offers, notice boards containing WBG information, responsible alcohol intake information, etc.

Facilitating the employment of RRS-specific to reducing pivotal psychological and social risks will go some way towards yielding more revenue for restaurants via the WBG option. Because of the dynamics between the members of dining groups, restaurants should strive to establish who the group’s decision-maker for ordering wine is and focus their efforts more on this person. Knowing who the consumer is remains key to the success of restaurants and information about the market segment(s) patronising a restaurant and, can also be put to good use to match the wine ordering situation with the type of consumer dining there. Consumers with high levels of enduring involvement are likely to act as opinion leaders based on our finding that the level of enduring involvement strongly affects the need for consumers to disseminate information about wine to others. Therefore, restaurants’ digital marketing strategies could be aligned with this. Training of restaurant staff should align with the abovementioned practical implications.

Similar to other studies, ours has some limitations. The WBG motivational process could also be influenced by other consumer behavioural psychology constructs, such as opinion leadership, objective and/or subjective product knowledge, and product experience. Although the social nature of restaurant dining is inherently associated with multi-person dining groups, the influence of dining companions was not measured in our study.

Our study also springboards some future research recommendations. Other psychological constructs such as opinion leadership, objective and/or subjective product knowledge, and product experience could be included and their relationship with the involvement and WBG risk perception constructs examined. “Informal” opinion leadership that occurs within a dining group in a restaurant when wine choices are made, is likely to yield important further insights. The influence of food, e.g., type of cuisine, quantity consumed, etc. could be included in further research on the WBG context in restaurants. Further work on all the effects of situational involvement in the dining situation is also needed. The proven importance via our study of situational involvement in the restaurant dining situation, warrants further work on all of the effects of situational involvement. The impact of specifically, psychological risk, on both information seeking and information dissemination, should also be further examined. The body of theoretical knowledge our study generated, can be further enhanced in future studies that examine interaction effects of both a mediating and moderating nature, following the outcomes of first testing the primary pathways. Future research could possibly explore post Covid-19 pandemic WBG and whether single-serve helps to act as a hygiene risk-reduction factor. Similar future studies conducted in South Africa, could examine if the race socio-demographic aspect has a strong influence on consumer behaviour, and the nature of such influence(s). From an expenditure viewpoint, all possible expenditure permutations could be unravelled by measuring the expenditure on food, non-alcoholic beverages, etc. and how these relate to WBG expenditure.

Ethics approval statement

The research team was judged to be acting in a collaborative role to the retail partners and not collecting any personal identifying information, and hence the Ethics Committee of the University indicated that this study did not require ethics approval.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acuti, D., V. Mazolli, L. Grazini, and R. Rinaldi. 2020. New patterns in wine consumption: The wine by the glass trend. British Food Journal 122, no. 8: 2655–69.

- Bagozzi, R.P., and Y. Yi. 2012. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40, no. 1: 8–34.

- Bauer, R.A. 1960. Consumer behavior as risk taking. In Dynamic marketing for a changing world, ed. R.H. Hancock, 389–98. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association.

- Blais, A.-R., and E.U. Weber. 2006. A domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgment and Decision Making 1, no. 1: 33–47.

- Bloch, P.H. 1981. An exploration into the scaling of consumers’ involvement with a product class. In Advances in consumer research, 8(1), ed. KB Monroe, 61–5. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research.

- Bloch, P.H., and M.L. Richins. 1983. A theoretical model for the study of product importance perceptions. Journal of Marketing 47, no. 3: 69–81.

- Bohnet, I., F. Greig, and R. Zeckhauser. 2008. Betrayal aversion: evidence from Brazil, China, Oman, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States. American Economic Review 98, no. 1: 294–310.

- Bruwer, J., A. Palacios Arias, and J. Cohen. 2017. Restaurants and the single-serve wine by-the-glass conundrum: risk perception and reduction effects. International Journal of Hospitality Management 62: 43–52.

- Bruwer, J., J. Cohen, and K.M. Kelley. 2019. Wine involvement interaction with dining group dynamics, group composition and consumer behavioural aspects in USA restaurants. International Journal of Wine Business Research 31, no. 1: 12–28.

- Bruwer, J., and C. Rawbone-Viljoen. 2013. BYOB as a risk-reduction strategy (RRS) for wine consumers in the Australian on-premise foodservice sector: exploratory insights. International Journal of Hospitality Management 32, no. 1: 21–30.

- Bruwer, J., and J. Cohen. 2019. Restaurants and wine by-the-glass consumption: motivational process model of risk perception, involvement and information-related behaviour. International Journal of Hospitality Management 77: 270–80.

- Bruwer, J., and J. Cohen. 2022. Craft beer in the situational context of restaurants: effects of product involvement and antecedents. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 34, no. 6: 2199–226.

- Bruwer, J., M. Fong, and A.J. Saliba. 2013. Perceived risk, risk-reduction strategies (RRS) and consumption occasions: roles in the wine consumer’s purchase decision. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 25, no. 3: 369–90.

- Bűttner, O.B., A. Florack, and A.S. Göritz. 2013. Shopping orientation and mindsets: How motivation influences consumer information processing during shopping. Psychology and Marketing 30, no. 9: 779–93.

- Canziani, B.F., B. Almanza, R.E. Frash, M.J. McKeig, and C. Sullivan-Reid. 2016. Classifying restaurants to improve usability of restaurant research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28, no. 7: 1467–83.

- Carvalho, N.B., L.A. Minim, M. Nascimento, G.H. de C. Ferreira, and V.P.R. Minim. 2018. Characterization of the consumer market and motivations for the consumption of craft beer. British Food Journal 120, no. 2: 378–91.

- Celsi, R.L., and J.C. Olson. 1988. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research 15, no. 2: 210–24.

- Charters, S., and S. Pettigrew. 2006. Product involvement and the evaluation of wine quality. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 9, no. 2: 181–93.

- Choi, J.A., M. Koo, I. Choi, and S. Auh. 2008. Need for cognitive closure and information search strategy. Psychology and Marketing 25, no. 11: 1027–42.

- Dearden, J.A., X. Guo, and C.D. Meyerhoefer. 2021. Restaurant wines: bottle margins and the by-the-glass option. Journal of Wine Economics 16, no. 3: 305–20.

- Dholakia, U.M. 2001. A motivational process model of product involvement and consumer risk perception. European Journal of Marketing 35, no. 11/12: 1340–62.

- Dodd, T.H., D.A. Laverie, J.F. Wilcox, and D.F. Duhan. 2005. Differential effects of experience, subjective knowledge, and objective knowledge on sources of information used in consumer wine purchasing. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 29, no. 1: 3–19.

- Dowling, G.R., and R. Staelin. 1994. A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research 21, no. 1: 119–34.

- Durham, C.A., I. Pardoe, and Vega-H. Esteban. 2004. A methodology for evaluating how product characteristics impact choice in retail settings with many zero observations: An application to restaurant wine price. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 29, no. 1: 113–31.

- Ellis, D., and A. Caruana. 2018. Consumer wine knowledge: components and segments. International Journal of Wine Business Research 30, no. 3: 277–91.

- Euromonitor International. 2021. Wine in South Africa Passport Report. Euromonitor International, London: UK, May, 1–13.

- Euromonitor International. 2022. Consumer foodservice by location in South Africa Passport Report. Euromonitor International, London: UK, March, 1–18.

- Flynn, L.R., and R.E. Goldsmith. 1993. Application of the personal involvement inventory in marketing. Psychology and Marketing 10, no. 4: 357–66.

- Frost, D. 2015. Selling wine: Most people don’t prefer wine in a bottle, they prefer it in a glass. Restaurantowner.com. Available from: http://www.restaurantowner.com/public/ 381print.cfm, [Accessed 13 January 2023].

- George, D., and M. Mallery. 2010. SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 17.0 update,10th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Giacalone, D., M. Duerlund, J. Boegh-Petersen, W.L.P. Bredie, and M.B. Frost. 2014. Stimulus collative properies and consumers’ flavor preferences. Appetite 77, no. 2: 20–30.

- Grunert, K.G., and S.C. Grunert. 1995. Measuring subjective meaning structures by laddering method: theoretical considerations and methodological problems. International Journal of Research in Marketing 12, no. 3: 209–25.

- Guthrie, M.F., and H.-S. Kim. 2009. The relationship between consumer involvement and brand perceptions of female cosmetics consumers. Brand Management 17, no. 2: 114–33.

- Hair, J.F., C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19, no. 2: 139–51.

- Johnson, T.E., and J. Bruwer. 2004. Generic consumer risk-reduction strategies (RRS) in wine-related lifestyle segments of the Australian wine market. International Journal of Wine Marketing 16, no. 1: 5–35.

- Klerck, D., and J.C. Sweeney. 2007. The effect of knowledge types on consumer-perceived risk and adoption of genetically modified foods. Psychology and Marketing 24, no. 2: 171–93.

- Lacey, S., J. Bruwer, and E. Li. 2009. The role of perceived risk in wine purchase decisions in restaurants. International Journal of Wine Business Research 21, no. 2: 99–117.

- Laurent, G., and J.N. Kapferer. 1985. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. Journal of Marketing Research 22, no. 1: 41–53.

- Lesschaeve, I., A. Bowen, and J. Bruwer. 2012. Determining the impact of consumer characteristics to sensory preferences in commercial white wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 63, no. 4: 487–93.

- Lin, T.M., and C.H. Fang. 2006. The effects of perceived risk on the word-of-mouth communication dyad. Social Behavior and Personality 34, no. 10: 1207–16.

- Mackenzie, S.B., and P.M. Podsakoff. 2012. Common method bias in marketing: causses, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing 88, no. 4: 542–55.

- Mazzarol, T., J.C. Sweeney, and G.N. Soutar. 2007. Conceptualizing word-of-mouth activity, triggers and conditions: An exploratory study. European Journal of Marketing 41, no. 11/12: 1475–94.

- Mintel. 2019. Global food and wine drink trends 2030. Mintel Group Ltd. London: UK. Available from: https://downloads.mintel.com/private/vKd7N/files/801025/ [Accessed 13 March 2023].

- Miranda, S., and M. Duarte. 2022. How perfectionism reduces positive word-of-mouth: The mediating role of perceived social risk. Psychology and Marketing 39, no. 2: 255–70.

- Mitchell, V.-W. 1999. Consumer perceived risk: conceptualisations and models. European Journal of Marketing 33, no. 1/2: 163–95.

- Nunkoo, R., H. Ramkissoon, and D. Gursoy. 2013. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research: past, present and future. Journal of Travel Research 52, no. 6: 759–71.

- Nunnally, J.C., and I. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric theory,Third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. 1–752.

- Ogbeide, O.A., and J. Bruwer. 2013. Enduring involvement with wine: predictive model and measurement. Journal of Wine Research 24, no. 3: 210–26.

- Palazon, M., and E. Delgado-Ballester. 2013. Hedonic or utilitarian premiums: does it matter? European Journal of Marketing 47, no. 8: 1256–75.

- Park, C.-W., and R.-J. Moon. 2003. The relationship between product involvement and product knowledge: moderating roles of product type and product knowledge type. Psychology and Marketing 20, no. 11: 977–97.

- Park, D.-H., J. Lee, and I. Han. 2007. The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 11, no. 4: 125–48.

- Peterson, R.A., and M.C. Merino. 2003. Consumer information search behavior and the internet. Psychology and Marketing 20, no. 2: 99–121.

- Pew Research Center. 2015. The whys and hows of generations research. Avaiilable from: http://www.people-press.org/2015/09/03/the-whys-and-hows-of-generations-research/. [Accessed on 13 March 2023].

- Phillips, D.M., and W.K. Hallman. 2013. Consumer risk perceptions and marketing strategy: The case of genetically modified food. Psychology and Marketing 30, no. 9: 739–48.

- Richins, M.L., and P.H. Bloch. 1986. After the new wears off: The temporal context of product involvement. Journal of Consumer Research 13, no. 2: 280–5.

- Richins, M.L., P.H. Bloch, and E.F. McQuarrie. 1992. How enduring and situational involvement combine to create involvement responses. Journal of Consumer Psychology 1, no. 2: 143–53.

- Rinaldo, S.B., D.F. Duhan, B. Trela, T.H. Dodd, and N. Velikova. 2014. Evaluating tastes and aromas of wine: A peek inside the “black box”. International Journal of Wine Business Research 26, no. 3: 208–23.

- Roe, D., and J. Bruwer. 2017. Self-concept, product involvement and consumption occasions: exploring fine wine consumer behaviour. British Food Journal 119, no. 6: 1362–77.

- Saad, G. 2021. Addressing the sins of consumer psychology via the evolutionary lens. Psychology and Marketing 38, no. 2: 371–80.

- Shoham, A., and A. Ruvio. 2008. Opinion leaders and followers: A replication and extension. Psychology and Marketing 25, no. 3: 280–97.

- Sideridis, G., P. Simos, A. Papanicolaou, and J. Fletcher. 2014. Using structural equation modeling to assess functional connectivity in the brain: power and sample size considerations. Educational and Psychological Measurement 74, no. 5: 733–58.

- Sun, T., Z. Tai, and K.-C. Tsai. 2010. Perceived ease of use in prior e-commerce experiences: A hierarchical model for its motivational antecedents. Psychology and Marketing 27, no. 9: 874–86.

- Tarkiainen, A., and S. Sundqvisdt. 2009. Product involvement in organic food consumption: does ideology meet practice? Psychology and Marketing 26, no. 9: 844–63.

- Taylor, S., and P. Todd. 1995. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behaviour: A study of consumer adoption intentions. International Journal of Research in Marketing 12, no. 2: 137–55.

- Terrier, L., and A.-L. Jaquinet. 2016. Food-wine pairing suggestions as a risk reduction strategy: reducing risk and increasing wine by the glass sales in the context of a Swiss restaurant. Psychological Reports 119, no. 1: 174–80.

- Thomé, K.M., G. da M.P. Pinho, D.P. Fonseca, and A.B.P. Soares. 2016. Consumers’ luxury value perception in the Brazilian premium beer market. International Journal of Wine Business Research 28, no. 4: 369–86.

- Warrington, P., and S. Shim. 2000. An empirical investigation of the relationship between product involvement and brand commitment. Psychology and Marketing 17, no. 9: 761–82.

- Watson, L., and M.T. Spence. 2007. Causes and consequences of emotions on consumer behaviour: A review and integrative cognitive appraisal theory. European Journal of Marketing 41, no. 5/6: 487–511.

- Yoon, E., and M. Stacy. 2015. The billion-dollar opportunity in single-serve food. Harvard Business Review. Available from: https://hbr.org/2015/10/the-billion-dollar-opportunity-in-single-serve-food [Accessed 13 January 2022].

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. 1985. Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research 12, no. 3: 341–52.

Appendices

Appendix A: Measurement of the reliability of WBG perceived risk scale items

Appendix B: reliability of involvement and information processing constructs’ scale items