ABSTRACT

Firm innovation is of vital importance to New Zealand’s economy, but we understand little about how different human resource (workforce) factors influence innovation approaches (product/services innovation, process innovation, and innovation speed). We explore three human resource (HR) factors: workforce knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs), workforce attraction, and workforce retention, using a sample of New Zealand private sector firms (n = 402). Regression analysis shows all HR factors are significant predictors of all innovation approaches. Further analysis shows workforce KSAs is dominant towards product/service innovation, workforce attraction is dominant towards process innovation, and workforce retention is dominant towards innovation speed. Moderating effects by firm size are found showing small-sized firms out innovate large-sized firms when workforce KSA are high, despite small-sized firms having, on average, weaker HR factors and innovation approaches than large-sized firms. We highlight the organisational implications across small – and large-sized firms.

Introduction

Firm innovation is an important outcome because it links to the financial performance of a firm (Li et al. Citation2010). Further, others argue societal benefits for New Zealand (e.g. Gluckman Citation2015; Yeoman and Bibby Citation2015; Ruckstuhl et al. Citation2019), such as aiding economic growth. However, despite the financial links, some have warned about the primarily profit focus of innovation (Vunibola and Scobie Citation2022). While we understand firm innovation is important, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE Citation2019) reports that New Zealand firms spend lower amounts on Research & Development (R&D) than other OECD countries (1.17% of GPD compared to the OECD average of 2.37%). Further, Fabling and Statistics New Zealand (Citation2007) suggest that globally, New Zealand firms are amongst the lowest spenders on R&D.

Hong et al. (Citation2016) noted that despite New Zealand being ranked number one across important growth fundamentals categories (e.g. ease of business set-up), New Zealand ‘is “middle of the pack” (or worse) when it comes to economic growth, productivity and process innovation’ (p. 5379). While the OECD (Citation2019) attributes New Zealand poor innovation on size (firms, markets, and cities), New Zealand does have some highly innovative firms. For example, Rocket Lab launches rockets for clients including NASA, and Buckley Systems Limited, manufacture precision equipment for semiconductor and medical applications. The present study seeks to answer questions about what factors aid New Zealand firm innovation.

This paper focuses on three innovation approaches to move beyond the typical single innovation focus of studies, such as focusing on product innovation only (e.g. Haar et al. Citation2022a). Indeed, studies have found different effects towards different innovation types (e.g. Messersmith and Guthrie Citation2010). Thus, assuming factors will link to distinct innovation approaches may be flawed. Further, this might be especially valuable if we find similarities or differences across the three approaches. Product/service innovation refers to ‘new products or services introduced to meet an external user or market need’ (Damanpour and Gopalakrishnan Citation2001, p. 47), process innovation is defined by Utterback and Abernathy (Citation1975) as ‘the system of process equipment, workforce, task specifications, material inputs, work and information flows, etc. that are employed to produce a product or service’ (p. 641), while innovation speed captures the rate or speed with which a firm realises processes or product/service additions (Prajogo and Sohal Citation2006).

One poorly explored factor in understanding New Zealand firm innovation relates to Human Resource (HR) factors. Internationally, the links between human capital and firm performance are well established (Crook et al. Citation2011), but there is only modest attention given towards firm innovation. Alpkan et al. (Citation2010) define human capital as the collection of individual employee knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) of a firm’s workforce. While some have acknowledged the importance of human capital in New Zealand (Gluckman Citation2015) there is scant empirical evidence. We use the Resource Based View (RBV, Barney Citation1991) to theoretically understand how HR factors can influence firm innovation. Further, testing HR factors towards three innovation approaches provides an additional theoretical test of RBV to determine whether effects are consistent or produces a lack of consistent effects, which might highlight potential theoretical limitations.

Beyond the established workforce KSAs (human capital), the literature also highlights that firms with strong workforce retention outperform their competitors, because the retention of a skilled and talented workforce is vital. Park and Shaw (Citation2013) state, ‘on average, organizations with low turnover rates have accumulated much human capital. When employees leave, replacement employees cannot equal the lost human capital until much time passes’ (p. 269). Despite the complimentary nature of human capital and employee retention, these factors are seldom examined together.

Next, this study adds workforce attraction, which represents the ability of a firm to bring quality human capital onboard the firm. While attraction receives attention (e.g. Hutchings et al. Citation2011) it has received much less than employee retention (e.g. Park and Shaw Citation2013), especially at the firm level. In combination, this study broadly examines the role of HR factors in New Zealand firms, and how skilled and competent firm workforces are, how well they are retained, and the ability of firms to attract workers. Seldom do firm studies explore both the quality of the existing workforce, the ability of a firm to retain them, and their ability to attract new talent. Ultimately, we have little New Zealand evidence of any of these HR factors and none with all three in combination. Finally, we capture the New Zealand context by including firm size. MBIE (Citation2021) reports that 97% of firms in New Zealand are small sized, and New Zealand firm evidence suggests firm-size does create differences in innovation (Haar et al. Citation2022b).

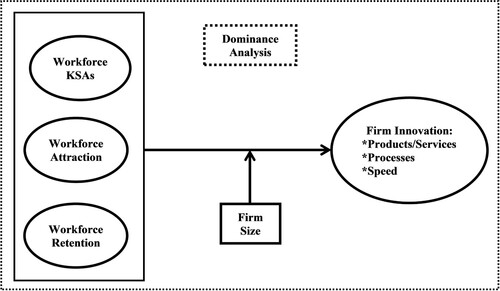

Overall, the present study contributes to the firm innovation literature by examining these three HR factors in combination: workforce KSAs, attraction of new workforce members, and the retention of existing workforce. This fills important gaps in the literature, especially considering the combination of these HR factors within the context of New Zealand firm innovation. Finally, the addition of dominance analysis to determine the strength of effects across the three HR factors towards innovation and comparing effects by firm size adds additional insights. Hence, we can determine what HR factors are most dominant towards innovation approaches and whether these differ by firm size. Ultimately, this paper answers three research questions: (1) what role do different HR factors play on the innovation of New Zealand firms? (2) does this differ by innovation type? and (3) does it differ by firm size? See for our study model.

Resource based view and HR factors

Crook et al. (Citation2011) notes that human capital represents not just the explicit ‘how-to’ of a workforces KSAs ‘but also tacit KSAs, which can often be difficult to articulate’ (p. 444). Firms with superior human capital have workforces that are more educated, skilled, and who acquire job-related knowledge continuously (Yang and Lin Citation2009). Hence, this represents the human resources available for a firm, with evidence suggesting this leads to better performance. Typically, the literature utilises the RBV of the firm (Barney Citation1991) to understand how human capital enhances firm performance (Crook et al. Citation2011). RBV theory argues that firms might have several resources available to them, which can be leveraged to achieve an advantage over competitors. To achieve a competitive advantage, these resources need to be valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Barney Citation1991). Not all firms are likely to have such resources, and the RBV helps explain why some firms outperform others.

The RBV approach is well accepted within the human capital literature, with Crook et al. (Citation2011) stating it ‘argues that the heterogeneous distribution of valuable resources among firms – such as human capital – explains performance differences’ (p. 443). For example, not all workforces are the same. Some workforces have greater industry knowledge, some workforces are more skilled and have superior abilities, and this allows them to be more creative and their firm innovative at superior levels. Human capital does include education but having a more educated workforce alone might not be enough. It is the associated KSAs that best capture human capital and how these levels can vary across firms. Superior human capital is a valuable resource that firms can leverage to create better innovation. We use the term Workforce KSAs to capture firm human capital.

Under RBV, the key to understanding how human capital benefits firm innovation and performance is via knowledge (Youndt and Snell Citation2004; Teece et al., Citation1997). It is argued that it is the ‘knowledge embedded in human capital as being among the most universal of resources that meet’ the RBV criteria (Crook et al. Citation2011, p. 444). Thus, a knowledgeable workforce might have the experience and insight to work around complex issues to create new products and services, superior production processes, and do these faster than competitors. Importantly, competitors are likely to be challenged by how their competitors have achieved such innovations approaches and struggle to copy and keep up with such innovative practices. This reflects the RBV (Barney Citation1991) because such knowledge resources are valuable, not common amongst competitors (i.e. rare), and are very hard for competitors to copy (i.e. inimitable). Finally, the challenge for competitors is that knowledge (via human capital) is non-substitutable – it is very hard for competitors to replicate the unique advantages of workforce knowledge. Hiring more skilled workers might be the start, but to create an equivalent workforce with identical KSAs is highly unlikely, especially when we consider industry knowledge amongst a workforce. This is why human capital and similarly HR factors (i.e. attraction and retention) can be valuable to a firm.

Empirically, workforce KSAs (human capital) is linked to greater firm performance including operational performance (Crook et al. Citation2011), and while this does include innovation, it is seldom explored, and not across different innovation approaches. While the human capital literature acknowledges firms can enhance their workforce’s human capital via training or acquiring new and more skilled capital (Youndt and Snell Citation2004), research often fails to take a nuanced approach. Typically, research captures human capital as a measure of a workforces KSAs but sometimes focuses only on this single factor (e.g. Hu et al. Citation2023). The present study seeks to address this issue by including a focus on acquiring new KSAs through workforce recruitment. Tumasjan et al. (Citation2020) noted the links between recruitment and firm performance are relatively scarce, but they found recruitment was correlated significantly with firm performance (r = .30, p < .01). Here, we suggest examining human capital and workforce attraction provides a more comprehensive understanding around capital existing and recently acquired.

Finally, aligned with acquiring new human capital we also include the retention of existing human capital. While workforce turnover occurs naturally in business, a firm that retains more of its workforce than competitors is advantageous. This is especially important when the retention is on more skilled workers (e.g. Takeuchi et al. Citation2007). In their meta-analysis, Park and Shaw (Citation2013) found employee turnover was significantly and negatively linked to organisational performance, with a small average corrected correlation (r = −.15). Ultimately, firms that are better able to retain their workforce are more likely to extract extra value of their human resources than competitors, who suffer the loss of institutional knowledge. Both attraction and retention of workforces align with RBV theory, because firms that can outperform competitors on attracting and retaining talent are illustrating valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable operations (Barney Citation1991). Overall, we expect all three human factors to be positively linked to firm innovation approaches. We posit the following.

Hypothesis 1: Workforce KSAs will be positively related to (a) product/service innovation, (2) process innovation, and (3) innovation speed.

Hypothesis 2: Workforce attraction will be positively related to (a) product/service innovation, (2) process innovation, and (3) innovation speed.

Hypothesis 3: Workforce retention will be positively related to (a) product/service innovation, (2) process innovation, and (3) innovation speed.

Moderating effects of firm size

There is growing empirical evidence that New Zealand firms differ by size (see Haar et al. Citation2022b). Meta-analysis has found large sized firms are more innovative (Damanpour Citation2010), and this aligns with the study by Haar et al. (Citation2022b). However, much of the literature is set outside New Zealand where size dynamics might be different. Indeed, New Zealand evidence points to mixed findings, whereby some studies support advantages for large-sized New Zealand firms (Haar and Spell Citation2007, Citation2008), but also, no differences by firm size (Haar et al. Citation2009). Under the RBV, firm-size might be useful to determining whether larger-sized firms have additional resources that enable them to leverage their HR factors better towards innovation approaches than small-sized firms. For example, under RBV, it might be that small-sized firms can have resources that are valuable and rare, but perhaps their ability to create resources that are inimitable and non-substitutable are more challenged. For example, larger competitors might buy successful small-sized firms to gain access to new knowledge that they might otherwise be unable to imitate.

In our focus on multiple HR factors towards different innovation approaches, we theoretically challenge the universal nature of potential effects by comparing small-sized firms with medium-sized and large-sized firms. We suggest that larger-sized firms might have a greater ability to attract and retain workforces due to a stronger public profile and greater financial resources (e.g. Haar and Spell Citation2008), allowing for higher wages and stronger employee development. This might enable them to achieve the inimitable and non-substitutable resources under RBV (Barney Citation1991). Overall, we hypothesise that firm size will moderate the effectiveness of HR factors influence on innovation approaches, leading to stronger benefits for large-sized firms. We posit the following.

Hypothesis 4: Firm size will moderate the effectiveness of HR factors on innovation approaches, with larger-sized firms reporting stronger benefits.

Determining strongest HR factor/s

Dominance analysis allows for the testing of the three HR factors to the three innovation approaches to determine the strength and weighting of each HR factor in relation to others. Here, three HR factors are current KSAs, retention, and attraction. Determining that one workforce factor dominates the influence on innovation approaches over another provides insights not often explored. While all HR factors can represent valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources under RBV (Barney Citation1991), there are theoretical benefits to testing for differences. For example, if workforce attraction is found to dominate, this captures those resources that are most valuable to firms in relation to others, and thus provides superior insight into resources and understand which resource might be more important (e.g. valuable, non-substitutable) than others. Theoretically, this aligns with the RBV of the firm.

The present study explores three HR factors: (1) workforce KSAs, as well as (2) the ability to attract new workforce members, and (3) the ability to retain existing workforce talent and one advantage of dominance analysis is that it identifies which are the most important dimensions (see Tonidandel and LeBreton Citation2011). This might be especially useful for organisations and firm leaders. For example, if the attraction of new workforce talent is especially beneficial to innovation approaches (i.e. most dominant), then this can enable firms to focus more on this activity. This dominance analysis approach has not been examined within the literature, although we do offer expected effects. Specifically, the links between human capital and performance (Crook et al. Citation2011) are stronger than this for employee retention (Park and Shaw Citation2013). While recruitment effects are limited and less established, Tumasjan et al. (Citation2020) did find mediums-sized effects that exceed those for retention. Hence, we expect human capital (current workforce KSAs) to be the dominant factor, followed closely by workforce recruitment, with workforce retention trailing last. Testing such strength differences remains under-examined in the firm innovation literature. We offer the following hypotheses towards the innovation approaches.

Hypothesis 5: The influence of the HR factors on (a) product/service innovation, (2) process innovation, and (3) innovation speed, will differ, with workforce KSAs being the dominant factor, followed by workforce attraction, and workforce retention last.

Method

Sample and participants

Data were collected using a Qualtrics survey panel with full ethics at the end of 2020. We focused on New Zealand private sector firms with senior managers reporting on their firms. Firms came from a wide range of industries and geographical locations. Recommendations by Bernerth et al. (Citation2021) were followed including removing fast completing respondents and using an instructed response item (e.g. ‘For this question, answer strongly agree only’) and removing those who fail the attention test. Overall, 402 firm respondents were collected with no missing data. Respondent firms were well split by size: 41.3% small-sized (50 employees or less) and 58.7% medium-large-sized (51 + employees). On average, respondent firms were on in the 16–20 years old bracket, and 19 industries were represented. The largest groups being financial and insurance services (18.9%), professional, scientific, and technical services (13.7%), retail (12.9%), and manufacturing (10.7%).

Measures

The study measures are shown in .

Table 1. Study measures and details.

Control Variables: We controlled for several firm demographic variables because these may influence innovation. Aliasghar and Haar (Citation2023) note that older firms are more likely to perform better, and thus firm age is controlled for. Firm Age (in yearly bands: 1 = up to one year, and then five-year bands e.g. 2 = 1–5 years, 3 = 6–10 years, etc. up to 12 = 51 + years). Further, Guthrie (Citation2001) argued that unionisation and industry might play key roles around firm performance and we controlled for Workforce Unionisation (as a percentage of workforce). For industry, we controlled for the three largest groupings in our sample that are most likely to links with innovation, creating dummy variables: Financial and Insurance Services (18.9%), Professional, Scientific and Technical Services (13.7%), and Manufacturing (10.7%). Finally, Hu and Zhang (Citation2021) found deteriorating business performance across Covid-19. Thus, we controlled for Covid Challenges with a single item ‘Has your business been directly affected by Covid-19 (e.g. loss of business, etc.)?’, coded 1 = Not at all, 2 = In a minor way, 3 = In a moderate way, 4 = In a major way.

Testing for common method bias

Common method bias (CMB) is a potential issue in single-source studies, and we follow recommendations (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003) to test for the potential of CMB. First, we conducted Harman’s One factor Test. An unrotated factor analysis was conducted with the first factor accounting for 36.6% of the variance, which is below the 50% threshold (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). Next, we conducted the Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001) procedure. This is a partial correlation controlling for an unrelated construct and shows CMB is unlikely if correlation strengths remain unaffected. In this study, we controlled for the manager respondent’s own Machiavellianism (4-items from Christie and Geis Citation1970, α = .92) and no change on the strength of correlations were found. Combined, these post-hoc analyses suggests that CMB if present is not playing a pervasive problem in our data.

Measurement models

We confirmed our constructs using Confirmatory Factor Analysis with AMOS (version 26) following recommendations (Hu and Bentler Citation1998): (1) the comparative fit index (CFI ≥ .90), (2) the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ .08), and (3) the standardised root mean residual (SRMR ≤ .10). Overall, the hypothesised measurement model was the best fit for the data: χ2(df) = 461.5(155), CFI = .92, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .06. Alternative models were also tested (e.g. combining various innovation measures), and these were all significantly poorer fit (all p < .001) to the data.

Analysis

Hypotheses were tested in SPSS (version 26) using hierarchical regression analysis. Step 1 had the control variables and Step 2 the HR factors (workforce KSAs, workforce attraction, workforce retention). Step 3 had the moderator firm size and Step 4 the interaction between firm size and the three HR factors (three separate interactions).

Finally, dominance analysis (details below) was conducted and the excel spreadsheet with macros by LeBreton (Citation2006) was utilised. To examine potential size differences, we re-analysed regression and dominance analyses by firm size (small versus medium-large). Johnson and LeBreton (Citation2004) describe dominance analysis as establishing the extent to which one variable (e.g. current workforce KSAs) predicts an outcome relative to other variables (e.g. workforce retention). This might be especially useful when considering multiple related factors (e.g. Lips-Wiersma et al. Citation2020). This involves re-running the regression models (excluding moderation) and entering the three independent variables (HR factors) in various combinations to determine their unique contribution to variance in the models.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are shown in .

Table 2. Correlations and descriptive statistics of study variables.

shows that amongst the key study variables, all HR factors are significantly correlated with all innovation approaches (all p < .001).

shows the results of the moderated regression analysis.

Table 3. Results of regression analyses.

shows that workforce KSAs, workforce attraction and workforce retention are all significantly related to innovation approaches of process and speed (all p < .001), while towards product/service innovation, workforce KSAs (p < .001), workforce attraction (p = .002), and workforce retention (p = .022) are significant but at differing statistical strengths. This provides support for Hypotheses 1–3. Indeed, the three HR factors (Step 2) account for large levels of variance (all p < .001) towards product/service innovation (21%), process innovation (36%), and innovation speed (37%). Step 3 shows firm size is significant towards product/service innovation and process innovation, accounting for only 1% variance, and no additional variance (p = .051) towards innovation speed. Further, Step 4 shows firm size interacts significantly and consistently with workforce KSAs towards all innovation processes (all p < .05), and workforce retention interacts significantly with firm size towards product/service innovation only (p = .021). Workforce attraction does not differ significant by firm size. Step 4 (interactions) accounts for an additional 2% variance towards product/service innovation (p = .011) and innovation speed (p < .001), and 1% additional variance towards process innovation (p = .003).

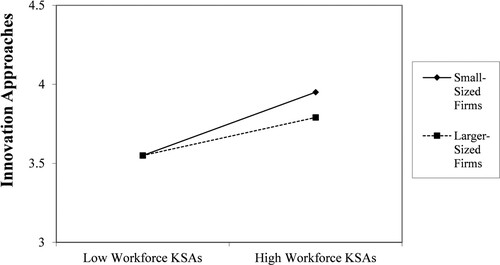

Overall, the moderated regression models are all significant and account for large amounts of variance towards product/service innovation (40%), process innovation (61%) and innovation speed (57%). We graph the interactions in only because all the workforce KSA interactions are all similar towards the innovation approaches, and similarly, the workforce retention x firm size interaction to product/service innovation is very similar.

Overall, the interactions show identical effects. At low levels of workforce KSAs, there is no difference in innovation approaches amongst small – or large-sized firms. However, when KSAs are high, small-sized firms outperform large-sized firms, reporting higher levels of product/service, process, and speed innovations. Similarly, towards product/service innovation, low levels of workforce retention see identical levels by firm size, but higher levels of workforce retention leads to higher increases in innovation for small-sized firms compared to large-sized firms. Overall, these effects are counter to our expectations and fail to support Hypothesis 4.

Finally, shows the results of dominance analysis.

Table 4. Results of dominance analyses on innovation outcomes.

shows that towards product/service innovation, workforce KSAs is the dominant workforce factor (accounting for 42.2% of all variances), and while workforce retention is the dominant factor towards process innovation (37.7%), and workforce attraction is the dominant factor towards innovation speed (38.8%). Given all three HR factors were dominant towards different innovation approaches, provides mixed support for Hypothesis 5, where it was expected workforce KSAs would be dominant.

Post-hoc analysis

Given the distinctions found by firm size, we further analysed the data to explore all study factors by firm size. shows the results of t-test analysis.

Table 5. Results of T-Tests by firm size.

Our t-test analysis showed that small-sized firms were significantly lower than larger-sized firms on workforce KSAs (p = .018), workforce attraction and retention (both p < .001). Similarly, all innovation approaches are significantly lower for small-sized firms (all p < .001).

Given the firm-size differences, we then re-analysed the dominance analysis to determine whether small-sized firms have differing importance (dominance) amongst the HR factors compared to large-sized firms. shows the results of dominance re-analysis by firm size.

Table 6. Dominance analyses on innovation outcomes by firm size.

shows that dominance analysis does differ by firm size. For large-sized firms, workforce KSAs is the dominant workforce factor towards product/service innovation (accounting for 47.2% of all variances), process innovation (40.9%), and innovation speed (36.4%). However, for small-sized firms, workforce KSAs is the dominant workforce factor only towards product/service innovation (accounting for 49.3% of all variances), while workforce attraction is dominant towards process innovation (49.9%), and innovation speed (49.3%). Interestingly, this analysis shows that as originally hypothesised, workforce KSAs are dominant for all innovation approaches for large-sized firms but only for product/service innovation for small-sized firms.

Discussion

The present study sought to enhance our understanding of how New Zealand firms innovate and the role that HR factors play in this. Despite workforce KSAs (human capital) being established as vital to firm performance including limited attention towards innovation outcomes (Crook et al. Citation2011), there is limited focus on understanding the role of other HR factors play on firm innovation. This study used three HR factors (workforce KSAs, workforce retention, and workforce attraction), and tested these towards three innovation approaches. to provide greater insight. While human capital focuses on a workforces KSAs (Alpkan et al. Citation2010), workforce retention is also known to be a key factor in firm performance (Park and Shaw Citation2013). This reflects the loss of knowledge when workforce turnover is high. Fundamentally, firms that have a highly skilled workforce that constantly turns-over faster than competitors, means these KSAs are not remaining within a firm to aid innovation.

Similarly, we added workforce attraction, because while it is noted as a key factor within the HR literature (e.g. Hutchings et al. Citation2011), and does have some employee-level research (Walker et al. Citation2009), it has received limited firm-level attention. For example, while Tumasjan et al. (Citation2020) explored recruitment efficiency at the firm level, this does not capture the alternative of workforce turnover around being able to recruit talent. Combined, these three HR factors provide a unique insight into understanding New Zealand firms.

Overall, the analysis showed consistently that all three HR factors were significantly related to all innovation approaches. Hence, New Zealand firms leverage distinct aspects around their workforces to achieve superior innovation. This includes attracting and retaining talent, especially top talent, which has largely been missing from the literature. This provides an important contribution to the innovation literature, extending the focus beyond HR practices (e.g. Haar et al. Citation2022b) and showing the key role that KSA, retention, and attraction play. Lee and Bruvold (Citation2003) highlighted that firms risk additional costs when losing talented staff, and here we find potential innovation gains to be had by firms who can attract and retain talent. This might also capture the unique or small number of key employees, called star performers, who can drive firm performance disproportionately (Aguinis et al. Citation2018; Asgari et al. Citation2021). Indeed, aligned with attraction and retention, Asgari et al. (Citation2021) highlighted ‘how stars impact peers’ and firms’ performance, as well as the influence they exert on knowledge generation and innovative outcomes’ (p. 240). Hence, retaining top talent can not only aid firm performance but also motivate and teach peers, ultimately building the human capital of the firm via training with ‘the best’. The findings towards innovation approaches also supports RBV theory (Barney Citation1991) and extends this across three innovation approaches and three HR factors. It provides support for RBV in understanding how firms with superior HR factors outperform (innovate) competitors.

One area of theoretical and research interest might be whether these HR factors can be combined together to create a new and more comprehensive construct of human capital. Thus, can human capital represent not only the existing workforces KSAs, but further the firm’s ability to attract and retain them. These factors were highly correlated (.60 < r < .41, all p < .01) and thus creating a single (new) human capital measure might be appropriate. However, we explored this option with exploratory factor analysis and found that workforce KSAs is a distinct factor compared to the other HR factors around attraction and retention. Hence, the data shows that such a global conceptualisation might not be a useful fit. This does align with the empirical results from the present study, where we found different dominance effects across innovation approaches (see below for more details). Thus, researchers are encouraged to keep human capital distinct from other HR factors like workforce attraction and retention. However, the findings here do show the value in including all these factors.

Next, we included firm size as a moderator because the New Zealand firm literature is replete with examples whereby larger-sized firms enjoy greater effects than small-sized firms (e.g. Haar and Spell Citation2007, Citation2008; Haar et al. Citation2022b). We also explored firm-size differences to see whether small – versus large-sized firms achieve similar HR factors and innovation approaches. Aligned with Damanpour (Citation2010), we did find that larger-sized New Zealand firms were more innovative (across all approaches) and clearly were able to leverage their size and resources to achieve superior levels of workforce KSAs, as well as workforce attraction and retention. Fundamentally, it appears that small-sized firms lack the resources, the reputation, and position in a market where 97% of the firms are small-sized (MBIE Citation2021) to adequately compete with larger-sized firms. However, the moderating effects did challenge these differences. Small-sized firms that lack of strength across their HR factors (KSAs, attraction, or retention) innovated no less than large-sized firms. However, small-sized firms with strong workforce KSAs achieved superior levels of innovation approaches compared to large-sized firms. Thus, small-sized firms were able to out innovate large-sized firms. This challenges past firm-size findings in New Zealand and encourages further exploration, especially across HR factors. Overall, small-sized firms, on average, don’t achieve the high levels of workforce KSAs, attraction, and retention, as big players, but those with a strong workforce KSAs are better able to leverage these resources to achieve higher innovations, which aligns with the RBV of the firm.

Finally, we used dominance analysis to determine whether some of the HR factors were more important towards innovation approaches. Dominance analysis follows the practice of providing additional insight whereby the most important dimensions are identified (Johnson and LeBreton Citation2004; Tonidandel and LeBreton Citation2011), and this can be especially useful when considering multiple related factors (e.g. Lips-Wiersma et al. Citation2020). However, it is not well utilised in firm-level studies and the findings here do support undertaking such an approach. We find that dominance analysis highlights the importance of workforce KSAs for product/service innovation, whereby workforce retention is dominant towards process innovation and workforce attraction is dominant for innovation speed. These findings are important because it suggests that across the whole sample, all three HR factors might be key for influencing different innovation approaches. However, when we further broke this down by firm size, we find that large-sized firms achieve innovation approaches best through greater workforce KSAs, while for small-sized firms, they achieve superior product/service innovations also by workforce KSAs, but enhanced innovations across processes and speeds via workforce attraction. This suggests how new skilled recruits to a small-sized firm can play a core role in building innovative processes and making innovations faster.

This suggests that small-sized New Zealand firms achieve greater process innovations and innovation speed through recruiting new ideas from new hires. This highlights the notion that human capital can be hired and as such, new workers might bring new ideas with them, that helps small-sized firms to gain insight into how existing processes can be modified and enhanced to make greater improvements faster. Perhaps small-sized firms are better able to go forth to the market and bring new ideas back into their workplace by simply hiring new workers with fresh ideas and different experiences. For example, hiring a successful competitor’s staff might not adversely affect large-sized firms due to their overall workforce size, but that single employee might provide enough insight into process development to substantially aid small-sized firms.

Implications

Firm innovation plays a critical role in firm performance (Haar et al. Citation2022a), but the present study found New Zealand firms differ markedly in the level of innovation achieved dependent on firm size (see ). For small-sized firms, those with strong workforce KSAs were better able to make innovation gains, across the spectrum, including new products/services, processes, and speed. Small-sized firms with the right skilled workforce appear to benefit more than large-sized firms in achieving innovation outcomes. Hence, focusing on developing their workforce KSAs, and this can be achieved through hiring or training, to enhance their skills and industry insights. Further, through strong workforce retention small-sized firms were able to achieve superior product/service innovation than large-sized firms, showing the value on retaining staff. This aligns with meta-analysis (Park and Shaw Citation2013) and might reflect the value in keeping skilled knowledge within a small workforce. However, dominance analysis showed for small-zied firms that workforce retention is key, thus, recognising the value of acquiring new talent, to introduce fresh thinking and new ideas, are likely important to advancing innovation processes and speed innovation.

Implications for larger-sized firms are different, whereby they need to recognise the importance and value of workforce KSAs and further build and leverage these to achieve consistent innovation gains. Interesting, across all the data, retention is less important than attraction and workforce KSAs, with both retention and attraction being less essential for large-sized firms. This might reflect that for large firms, turnover is a natural part of business and might be especially challenging to reduce. Thus, understanding the current ‘Great Resignation’ might be a less critical problem when there is a strong level of human capital, and the attraction of new talent keeps this workforce talent refreshed. Given retention is linked to performance (Park and Shaw Citation2013), these findings suggest a firm with a strong workforce KSA, and high workforce attraction, might be okay to reduce the focus on turnover. This might be considered a natural occurrence which a firm can easily counter with replenishing the workforce with new talent, which might be a more useful approach to target.

Research implications include exploring whether these HR factors hold for Māori business, which have been found to have similar levels of human capital than non-Māori New Zealand firms (see Haar et al. Citation2021). Given the cultural importance around people amongst Māori might provide an additional twist to the importance of these HR factors for Māori business. In addition, future research might explore the role of these factors – both HR factors and innovation approaches – on firm financial and associated performance indicators to further illuminate the effects of innovation amongst New Zealand firms. Further, researchers are encouraged to continue to explore firm size differences (e.g. as a moderator) to determine whether effects on innovation and/or performance differs across firm size.

Finally, policy implications are that HR factors play a key role on New Zealand firm innovation, but the benefits may vary by firm size. Small-sized firms achieve superior innovation outcomes when they have a workforce with high KSAs, encouraging policies that target small-sized firms especially around workforce training and development. This might provide the impetus for such firms to engage in greater upskilling of their workforces. Further, such policy implications may be more generalisable given that workforce KSAs are universally beneficial for large-sized firms across a range of innovation approaches. However, for small-sized firms, they might need different policies that target processes and speed, and here those that enhance workforce attraction are key. It might be that policies are needed that target key industries, perhaps those more in need of enhanced innovation processes, etc., to aid firms to better capture the unique properties of their industry to better aid attraction.

Limitations

Like most research, the present has limitations. Chiefly, the data is cross-sectional, suggesting that causality cannot be determined and while CMB might be an issue, our earlier analysis showed the current data was not problematic. While the workforce attraction and retention measures only were two-item constructs, the literature typically only use a single-item (e.g. Guthrie Citation2001), so we extended this literature, including the differentiation of top talent form other employees. Overall, combined with a robust CFA, we suggest the measures used here are not problematic. Overall, our sample included more than 400 New Zealand private sector firms across a broad range of industries, providing generalisability of these findings.

Conclusion

The present study sought to understand how New Zealand firms innovate given its importance (OECD Citation2019) and the limited attention given to New Zealand firms (see Hong et al. Citation2016). This is especially true on the HR factors tested here. This study examined the links between different HR factors towards three innovation approaches and showed that largely all HR factors were important. However, dominance analysis showed that each HR factor was important to a different innovation approach. Further, when looked at by firm size, we find greater similarity, with large-sized firms being dominated by workforce KSAs across all innovation approaches, while small-sized firms seeing workforce KSAs and workforce attraction as dominant. The findings encourage the examination of multiple HR factors by firm size. Overall, the evidence suggests larger-sized firms have much more developed HR factors and undertake more advanced innovation, but that small-sized firms can best larger competitors when their workforces are especially skilled. Overall, the findings provide strong support for New Zealand firms using HR factors to build innovation approaches and this provides new insights into understanding how firms can enhance their innovation. Ultimately, it is around the workforce and their KSAs, and a firm’s ability to attract and retain them.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (213 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguinis H, Ji YH, Joo H. 2018. Gender productivity gap among star performers in STEM and other scientific fields. Journal of Applied Psychology. 103(12):1283–1306.

- Aliasghar O, Haar J. 2023. Open innovation: are absorptive and desorptive capabilities complementary? International Business Review. 32(2):101865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101865.

- Alpkan L, Bulut C, Gunday G, Ulusoy G, Kilic K. 2010. Organizational support for intrapreneurship and its interaction with human capital to enhance innovative performance. Management Decision. 48(5):732–755.

- Asgari E, Hunt RA, Lerner DA, Townsend DM, Hayward ML, Kiefer K. 2021. Red giants or black holes? The antecedent conditions and multilevel impacts of star performers. Academy of Management Annals. 15(1):223–265.

- Barney JB. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management. 17(1):99–120.

- Bernerth JB, Aguinis H, Taylor EC. 2021. Detecting false identities: a solution to improve web-based surveys and research on leadership and health/well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 26(6):564–581.

- Christie R, Geis FL. 1970. Studies in machiavellianism. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Crook TR, Todd SY, Combs JG, Woehr DJ, Ketchen DJ. 2011. Does human capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between human capital and firm performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 96(3):443–456.

- Damanpour F. 2010. An integration of research findings of effects of firm size and market competition on product and process innovations. British Journal of Management. 21(4):996–1010.

- Damanpour F, Gopalakrishnan S. 2001. The dynamics of the adoption of product and process innovations in organizations. Journal of Management Studies. 38(1):45–65.

- Fabling, R, & Statistics New Zealand. 2007. How innovative are New Zealand firms? Quantifying & relating organisational and marketing innovation to traditional science & technology indicators. In: OECD, editor. Science, technology and innovation indicators in a changing world: responding to policy needs. Paris, France: OECD; p. 139–170.

- Gluckman SP. 2015. Science in New Zealand's future. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 45(2):126–131.

- Guthrie JP. 2001. High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: evidence from New Zealand. Academy of Management Journal. 44(1):180–190.

- Haar J, Martin WJ, Ruckstuhl K, Ruwhiu D, Daellenbach U, Ghafoor A. 2021. A study of Aotearoa New Zealand enterprises: how different are indigenous enterprises? Journal of Management & Organization. 27(4):736–750.

- Haar J, O’Kane C, Cunningham J. 2022a. Firm-level antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding climate. Journal of Business Research. 141:410–421.

- Haar J, O’Kane C, Daellenbach U. 2022b. High performance work systems and innovation in New Zealand SMEs: testing firm size and competitive environment effects. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 33(16):3324–3352.

- Haar J, Taylor A, Wilson K. 2009. Owner passion, corporate entrepreneurship, and financial performance: a study of New Zealand entrepreneurs. New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research. 7(2):19–30.

- Haar JM, Spell CS. 2007. Factors affecting employer adoption of drug testing in New Zealand. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. 45(2):200–217.

- Haar JM, Spell CS. 2008. Predicting total quality management adoption in New Zealand. Journal of Enterprise Information Management. 21(2):162–178.

- Hong S, Oxley L, McCann P, Le T. 2016. Why firm size matters: investigating the drivers of innovation and economic performance in New Zealand using the Business operations survey. Applied Economics. 48(55):5379–5395.

- Hu J, Hu L, Hu M, Dnes A. 2023. Entrepreneurial human capital, equity concentration and firm performance: evidence from companies listed on China's growth enterprise market. Managerial and Decision Economics. 44(1):187–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3673.

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. 1998. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 3(4):424–453.

- Hu S, Zhang Y. 2021. COVID-19 pandemic and firm performance: cross-country evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance. 74:365–372.

- Hutchings K, De Cieri H, Shea T. 2011. Employee attraction and retention in the Australian resources sector. Journal of Industrial Relations. 53(1):83–101.

- Johnson JW, LeBreton JM. 2004. History and use of relative importance indices in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 7:238–257.

- LeBreton JM. 2006. Dominance analysis 4.4: Excel file for estimating general dominance weights for up to 6 predictors from user-provided R-sq values. [accessed 2013 Feb 11] http://www1.psych.purdue. edu/∼jlebr eto/downloads.html.

- Lee CH, Bruvold NT. 2003. Creating value for employees: investment in employee development. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 14(6):981–1000.

- Li Y, Su Z, Liu Y. 2010. Can strategic flexibility help firms profit from product innovation? Technovation. 30(5-6):300–309.

- Lindell MK, Whitney DJ. 2001. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology. 86(1):114–121.

- Lips-Wiersma M, Haar J, Wright S. 2020. The effect of fairness, responsible leadership and worthy work on multiple dimensions of meaningful work. Journal of Business Ethics. 161(1):35–52.

- Messersmith JG, Guthrie JP. 2010. High performance work systems in emergent organizations: implications for firm performance. Human Resource Management. 49(2):241–264.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. 2019. New Zealand’s research, science & innovation strategy (Draft for consultation). [accessed 2019 Dec] https://www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/6935-new-zealands-research-science-and-innovation-strategy-draft-for-consultation.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2021). Small businesses in 2021. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/assets/small-business-factsheet-2021.pdf.

- OECD. 2019. OECD economic surveys New Zealand. Paris, France: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/new-zealand-2019-OECD-economic-survey-overview.pdf.

- Park TY, Shaw JD. 2013. Turnover rates and organizational performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 98(2):268–309.

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 88(5):879–903.

- Prajogo DI, Sohal AS. 2006. The relationship between organization strategy, total quality management (TQM), and organization performance––the mediating role of TQM. European Journal of Operational Research. 168(1):35–50.

- Ruckstuhl K, Haar J, Amoamo M, Hudson M, Waiti J, Ruwhiu D, Daellenbach U. 2019. Recognising and valuing Māori innovation in the high-tech sector: a capacity approach. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(1):72–88.

- Takeuchi R, Lepak DP, Wang H, Takeuchi K. 2007. An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 92(4):1069–1083.

- Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal. 18(7):509–533.

- Tonidandel S, LeBreton JM. 2011. Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology. 26(1):1–9.

- Tumasjan A, Kunze F, Bruch H, Welpe IM. 2020. Linking employer branding orientation and firm performance: testing a dual mediation route of recruitment efficiency and positive affective climate. Human Resource Management. 59(1):83–99.

- Utterback J, Abernathy WJ. 1975. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega. 3(6):639–656.

- Vunibola S, Scobie M. 2022. Islands of indigenous innovation: reclaiming and reconceptualising innovation within, against and beyond colonial-capitalism. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 52(sup1):4–17. https://doi-org.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/10.108003036758.2022.2056618.

- Walker HJ, Feild HS, Giles WF, Armenakis AA, Bernerth JB. 2009. Displaying employee testimonials on recruitment web sites: effects of communication media, employee race, and job seeker race on organizational attraction and information credibility. Journal of Applied Psychology. 94(5):1354–1364.

- Yang CC, Lin CYY. 2009. Does intellectual capital mediate the relationship between HRM and organizational performance? Perspective of a healthcare industry in Taiwan. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 20(9):1965–1984.

- Yeoman I, Bibby D. 2015. Science in New Zealand's future: ideas, issues and directions. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 45(2):59–64.

- Youndt MA, Snell SA. 2004. Human resource configurations, intellectual capital, and organizational performance. Journal of Managerial Issues. 16(3):337–360.